Introduction

The shell structure of nuclei is a fundamental framework in nuclear physics. However, for neutron-rich nuclei far from the stability valley, the traditional magic numbers N = 8, 20, 28, and 40 vanish [1-10] and new magic numbers such as N = 14, 16, 32, and 34 emerged [11-14]. The evolution of shell structures in exotic nuclei has significantly deepened our understanding of nuclear quantum many-body systems and their underlying nuclear forces. Light neutron-rich nuclei are particularly intriguing, as the development of radioactive beam facilities has facilitated unprecedented exploration of isotopic chains extending to the dripline region [15].

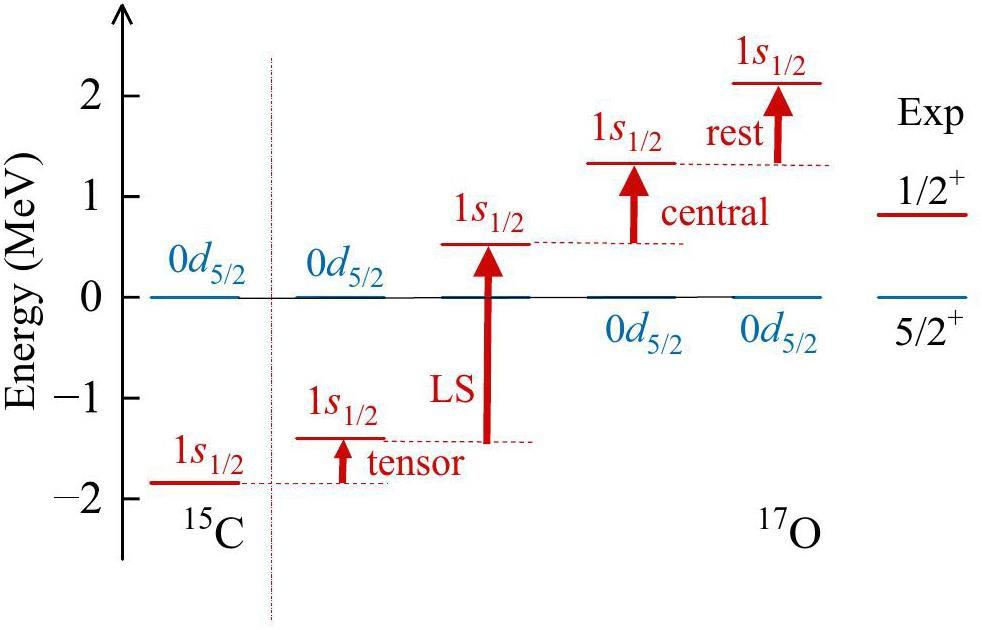

The neutron-rich oxygen isotopes 22O and 24O are doubly magic nuclei with a high excitation energy of the first 2+ excited state, providing clear evidence for the emergence of the N=14 and 16 subshell closures [14, 16-18]. However, a comparison of the systematic behavior of the 2+ energy levels in the oxygen and carbon isotopic chains suggests that the N=14 shell gap disappears in the carbon isotopes [19, 20]. In 15C, the ground state and first excited state are 1/2+ and 5/2+, respectively, indicating an inversion of the neutron ν1s1/2 and ν0d5/2 orbits in 15C compared to 17O [21, 22]. A similar inversion is anticipated when neutrons are added to 20C [19, 20]. As the transition region between oxygen and carbon isotopes, nitrogen isotopes also signal erosion of the N=14 shell gap [23-26]. Moreover, the evolution of the N=16 shell gap in neutron-rich boron, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen isotopic chains remains an intriguing question. Further experimental and theoretical studies are required to fully understand the origin and evolution of N=14 and N=16 shell gaps.

Neutron-rich boron, carbon, and nitrogen isotopes exhibit many exotic phenomena. For instance, two-neutron halo structures were observed in 17B [27], 19B [28], and 22C [29], while one-neutron halo structures were found in 15C [30] and 19C [31]. In addition, the observation of the most neutron-rich unbound nuclei, 20B and 21B, was recently reported in Ref. [32]. Furthermore, a thick neutron skin has been detected in 17-22N [26]. These light neutron-rich systems, which straddle the neutron dripline, have accumulated a wealth of experimental data, thereby providing an ideal testing ground for theoretical models [33]. These studies have inspired extensive theoretical studies, including the shell model (SM) [21, 34-36], Gamow shell model (GSM) [37-39], antisymmetrized molecular dynamics (AMD) [40, 41], and ab initio no-core shell model (NCSM) calculations [42-44]. However, traditional SM calculations, which employ phenomenological interactions, have limited predictive power as the nuclei approach the dripline. In contrast, ab initio calculations based on high-resolution interactions derived from the chiral effective field theory (χEFT) of quantum chromodynamics have made great progress over the past decades [45-52], offering a more robust framework for understanding and predicting the properties of neutron-rich nuclei.

Systematic calculations of neutron-rich boron, carbon, and nitrogen isotopes enable us to gain a more comprehensive understanding of their exotic structures and shell evolution while simultaneously testing our ab initio methods and nuclear forces. Therefore, in this study, we performed systematic calculations of neutron-rich boron, carbon, and nitrogen isotopes using the ab initio valence-space in-medium similarity renormalization group (VS-IMSRG) [53-58] based on nucleon-nucleon (NN) and three-nucleon (3N) interactions derived from χEFT.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: First, we provide a brief introduction to the VS-IMSRG framework. Next, we present systematic calculations of the spectra of neutron-rich boron, carbon, and nitrogen isotopes. Subsequently, we discuss the shell evolution of the N=14 and N=16 shell gaps in these isotopes utilizing the calculated effective single-particle energies (ESPE). Finally, we conclude with a summary of this work.

Method

The intrinsic Hamiltonian of an A-nucleon system can be written as

In practical calculations, Hamiltonian (1) is rewritten as normal-order operators with respect to the Hartree-Fock reference state,

Next, using the continuous unitary transformation

Results

Energy Spectra

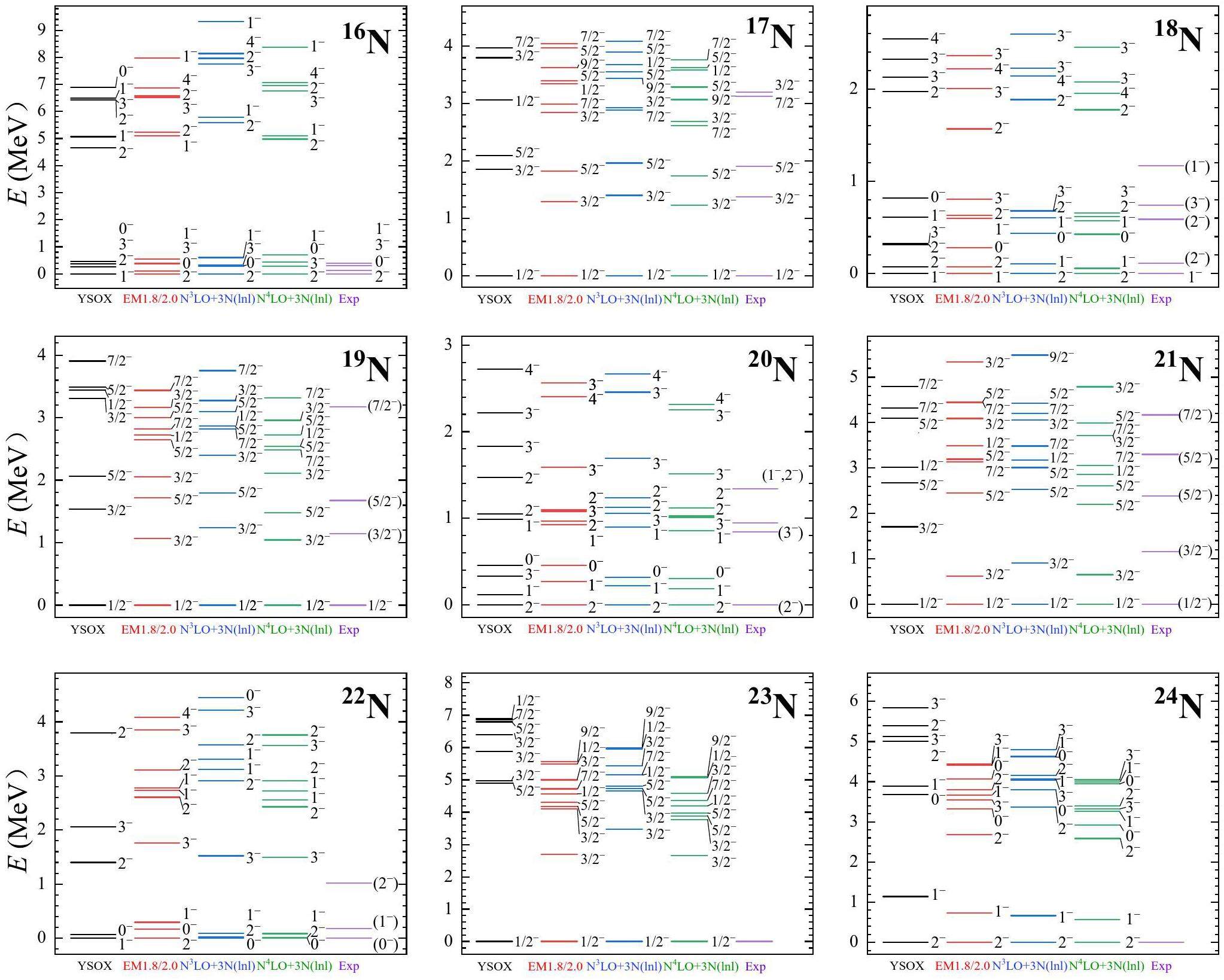

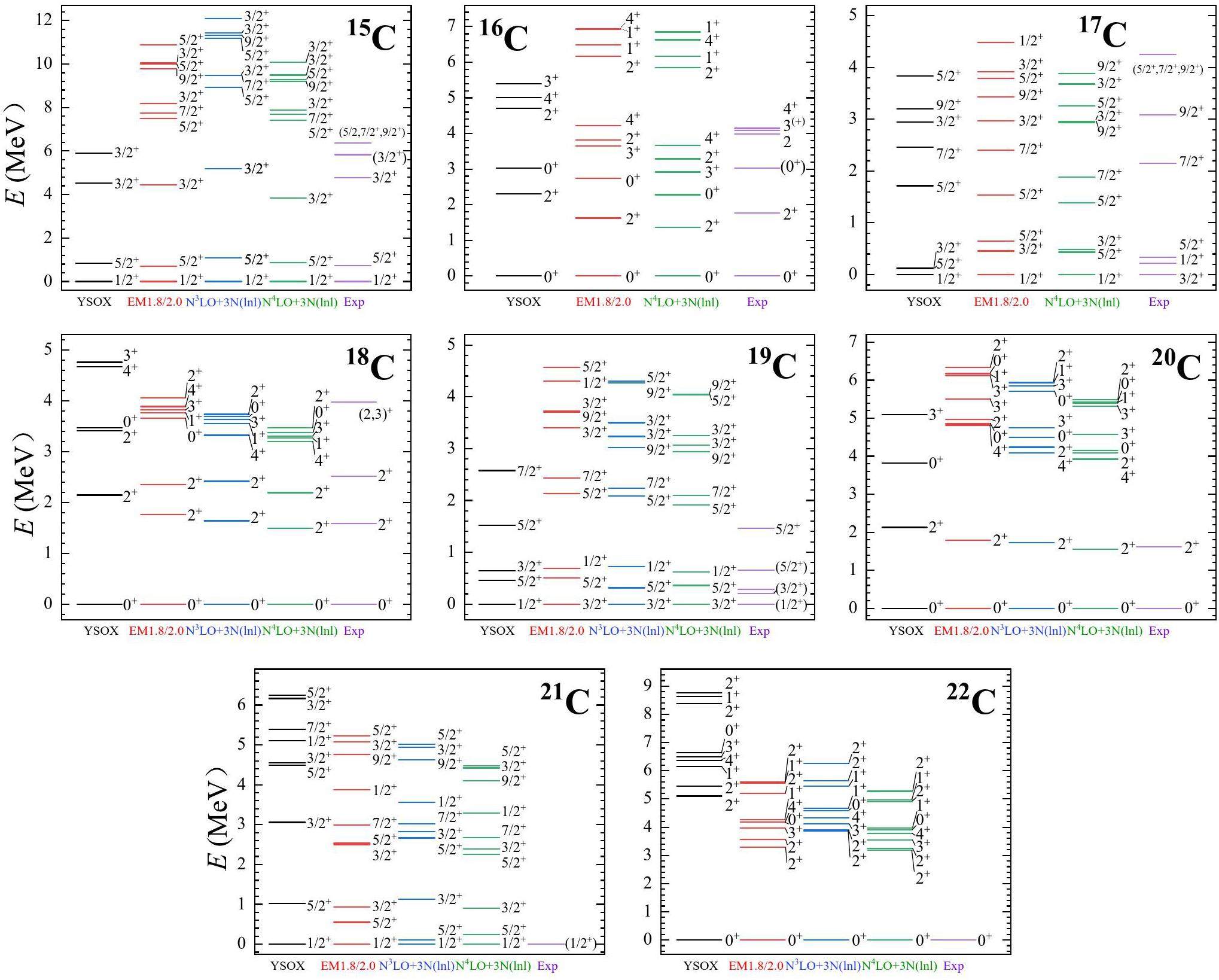

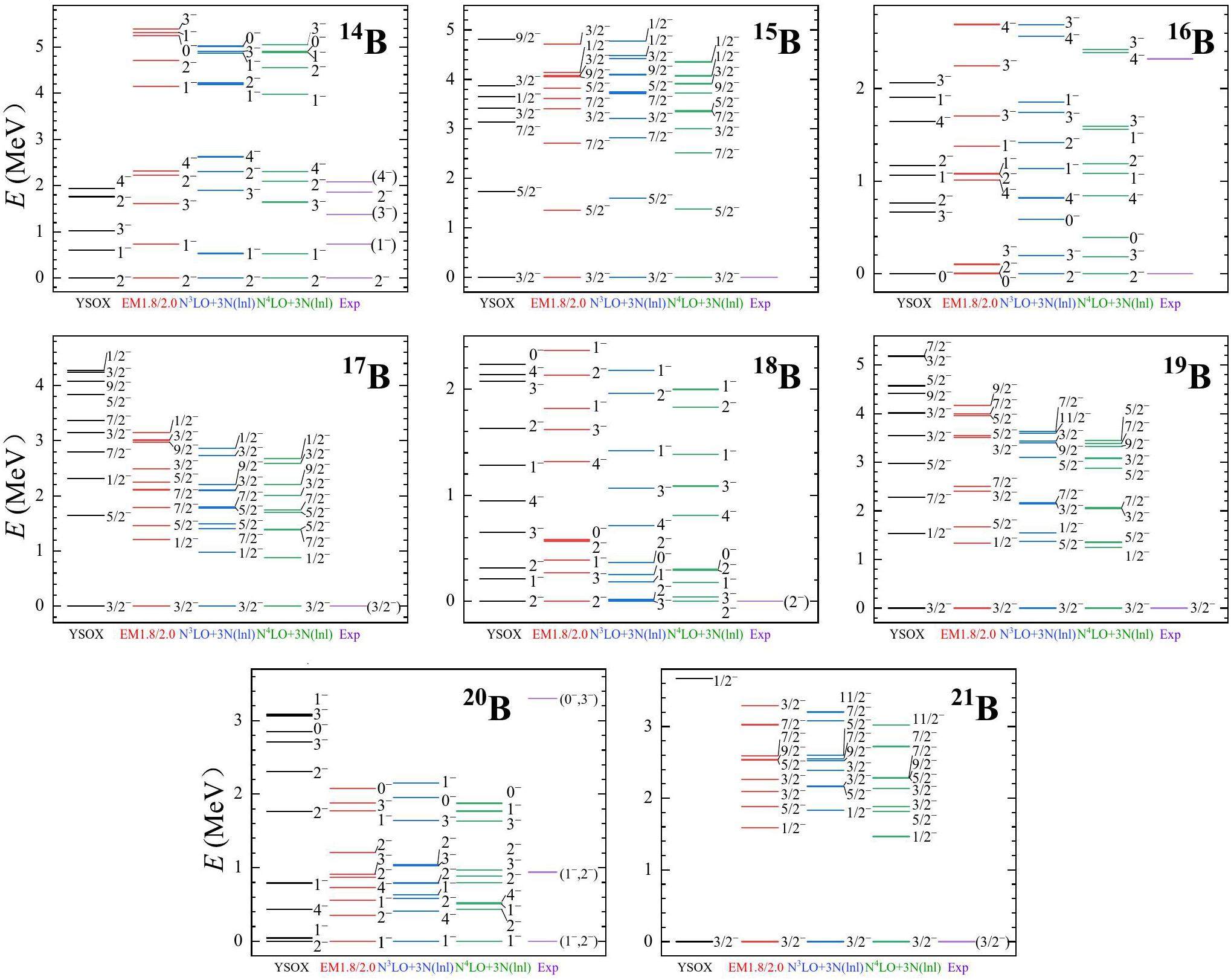

Nuclear spectra provide invaluable insights into nuclear structure. In this study, the spectra of neutron-rich boron, carbon, and nitrogen isotopes were systematically calculated using ab initio VS-IMSRG with three sets of χEFT NN + 3N interactions, that is, EM1.8/2.0 [59, 60], N3LO+3N(lnl) [9, 61], and N4LO+3N(lnl) [62]. For comparison, we also performed phenomenological SM calculations using the YSOX interaction within the full psd valence space, which accurately reproduced the properties of boron, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen isotopes [34]. The results were compared with the available experimental data, as illustrated in Fig. 1, 2 and 3.

Nitrogen isotopes have abundant experimental data, which provide a valuable test ground for our ab initio calculations. In addition, nitrogen nuclei lie between oxygen and carbon isotopes, offering essential insights into the shell evolution. For 16N, the ordering of the first four states is experimentally determined as 2-, 0-, 3-, and 1- [66]. Our VS-IMSRG calculations with the EM1.8/2.0 and N3LO+3N(lnl) interactions showed good agreement with the experimental results, whereas the SM calculations using the YSOX interaction failed to reproduce the spectra of 16N. For 17N, the VS-IMSRG calculations with the three NN + 3N interactions as well as the SM calculations using the YSOX interaction reproduced the lowest three states well. In the case of 18N, the ground state was correctly reproduced by the VS-IMSRG calculations with the EM1.8/2.0 interaction and the SM calculations using the YSOX interaction. However, the VS-IMSRG calculations with N3LO+3N(lnl) and N4LO+3N(lnl) interactions give 2- as the ground state. For 19,21N, all calculations correctly gave the ground state as 1/2- and predicted the first excited state as 3/2-, with the excited states yet to be experimentally confirmed. For 20N, the ground state is 2- given by all calculations. In the case of 22N, the VS-IMSRG calculations with the N3LO+3N(lnl) and N4LO+3N(lnl) interactions predicted a 0- ground state, whereas the VS-IMSRG calculations with the EM1.8/2.0 interaction and the SM calculations using the YSOX interaction predicted the ground state to be 2- and 1-, respectively. The size of the N=16 shell gap in 23N remains unclear [67]. All calculations predicted the ground state of 23N to be 1/2-. However, the SM calculations with the YSOX interaction yielded higher excitation spectra than the VS-IMSRG results, indicating an overly large N=16 shell gap in the SM calculations using the YSOX interaction. This behavior was also observed in 21B, 22C, and 24O, as discussed above. For 24N, all the calculations give the ground state as 2- and predict the first excited state as 1-.

Neutron-rich carbon isotopes have attracted considerable experimental and theoretical attention. The ground state and first excited state of 15C are 1/2+ and 5/2+, respectively, indicating an inversion of the neutron ν1s1/2 and ν0d5/2 orbits in carbon isotopes [21, 22]. Our VS-IMSRG calculations, along with the SM calculations, accurately reproduced the spectra of 15C. The VS-IMSRG calculations with the N3LO+3N(lnl) interaction for 16,17C did not converge; therefore, we only present the results for 16,17C using the EM1.8/2.0 and N4LO+3N(lnl) interactions in Fig. 2. For 16,18,20C, the first 2+ excited states obtained from our VS-IMSRG calculations are in good agreement with the experimental data, whereas SM calculations using the YSOX interaction generally provide higher energies for the first 2+ excited states of these nuclei. In particular, for 22C, the energy of the first 2+ excited state calculated by SM using the YSOX interaction is significantly higher than that predicted by VS-IMSRG. Notably, the first 2+ excited state of 24O, calculated by SM with YSOX interaction, is 5.41 MeV, which is higher than the experimental value of 4.76 MeV. In contrast, our VS-IMSRG calculations with the EM1.8/2.0, N3LO+3N(lnl), and N4LO+3N(lnl) interactions give the first 2+ excited state of 24O to be 4.87, 5.26, and 4.39 MeV, respectively, which are in better agreement with the experimental value. Moreover, the first 2+ excited state of 22C calculated by VS-IMSRG is significantly higher than that of the neighboring carbon isotopes, implying the presence of the N=16 shell gap in 22C. However, the calculated first 2+ excited state of 22C is lower than that of 24O, suggesting a reduction in the N=16 shell gap in 22C compared to 24O. In addition, the low energy of the first 2+ excited state in 20C indicates the disappearance of the N=14 shell gap in 20C [19]. For 17C and 19C, our VS-IMSRG calculations failed to reproduce the experimental spectra because of the absence of continuum coupling in the current method, as discussed in Ref. [37, 68].

In the case of neutron-rich boron isotopes, experimental data are limited. For 14B, the ordering of the first five states is experimentally assigned as 2-, 1-, 3-, 2-, and 4- [66]. Our ab initio VS-IMSRG calculations with the three NN + 3N interactions as well as the SM calculations using the YSOX interaction are all in good agreement with the experimental results. The spin and parity of the ground state for isotopes heavier than 14B have not yet been confirmed experimentally. For 15,17,19,21B, our VS-IMSRG calculations with the three NN + 3N interactions predict that the ground states of these isotopes are all 3/2-, which is consistent with SM calculations using the YSOX interaction. For 16B, the VS-IMSRG calculations with the N3LO+3N(lnl) and N4LO+3N(lnl) interactions predict the ground state to be 2-, whereas the VS-IMSRG calculations with the EM1.8/2.0 interaction predict a ground state of 0- with a 2- excited state that is nearly degenerate. In addition, the ground state of 16B obtained from the SM calculations using the YSOX interaction is also 0-. For the unbound nucleus 18B, SM calculations using YSOX and WBP [69] interactions predicted the ground state to be 2-. Our VS-IMSRG calculations with the EM1.8/2.0 and N4LO+3N(lnl) interactions also predicted the ground state of 18B to be 2-, but the VS-IMSRG calculations with the N3LO+3N(lnl) interaction gave the ground state of 18B to be 3-. Both 20B and 21B are unbound nuclei that exist as resonances and decay via one or two neutron emissions [32]. For 20B, our VS-IMSRG calculations with the three NN + 3N interactions predict the ground state to be 1-, whereas SM calculations using the YSOX interaction yield the ground state 2-. For 21B, our VS-IMSRG calculations with the three NN + 3N interactions predicted a significantly lower energy for the first excited state 1/2- compared to the SM calculations using the YSOX interaction, a situation similar to that observed for 22C and 24O above. The 1/2- state of 21B calculated with VS-IMSRG has larger neutron excitation components than those in the SM calculations. However, the subsequent analysis of the ESPE calculated by VS-IMSRG suggests that the N=16 subshell still exists in 21B.

Overall, our ab initio VS-IMSRG calculations based on the three χEFT NN + 3N interactions, particularly the EM1.8/2.0 interaction, were in good agreement with the available experimental data. These results provide critical assistance for future research.

Shell evolution

In neutron-rich boron, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen isotopes, the evolution of N = 14 and N = 16 shell gaps has attracted significant experimental and theoretical attention. The ESPE provides a good reflection of the size of shell gaps, which defined as [70, 71]

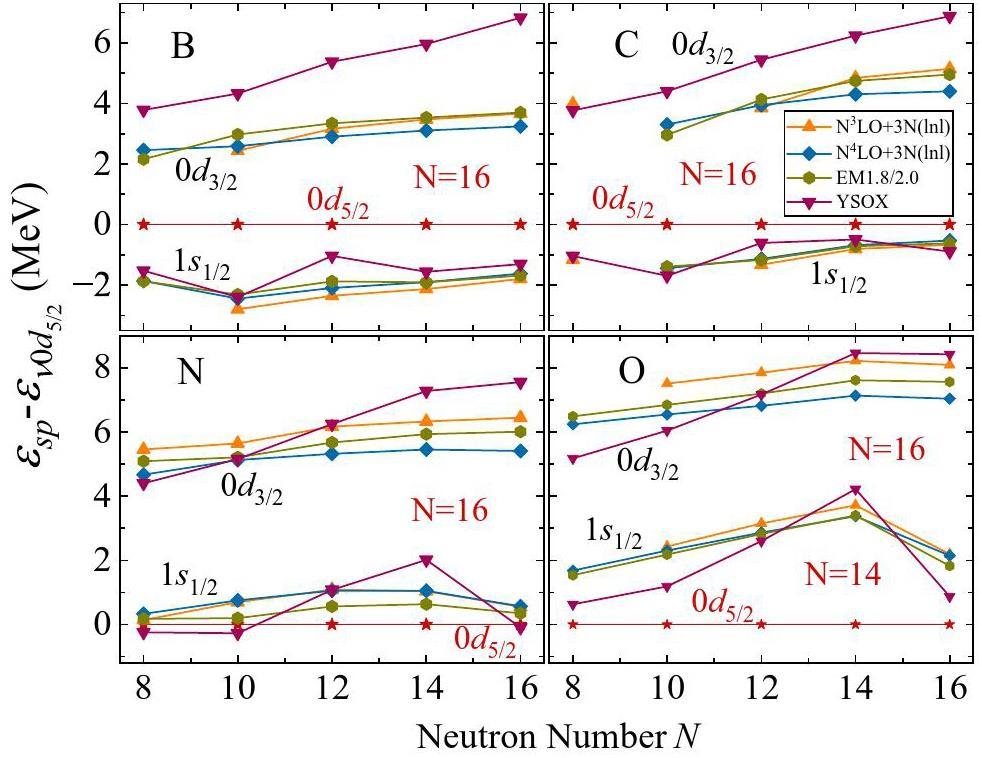

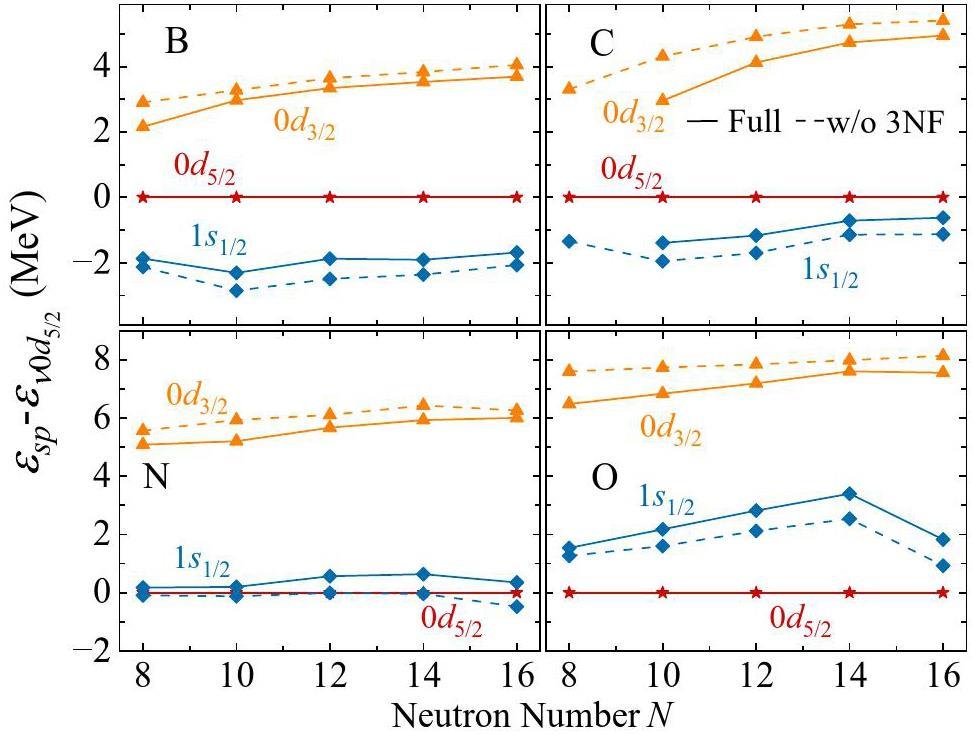

To study the evolution of the N=14 and N=16 shell gaps, we calculated the ESPE of the ν1s1/2, ν0d5/2, and ν0d3/2 orbits in these nuclei employing the VS-IMSRG method, based on the EM1.8/2.0, N3LO+3N(lnl), and N4LO+3N(lnl) interactions, compared with the SM calculations using the YSOX interaction. As shown in Fig. 4, for the VS-IMSRG calculations, when protons are removed from the oxygen isotopes, the ESPE of the ν1s1/2 orbital is gradually lowered relative to the ν0d5/2 orbital, and a reversal occurs in the boron and carbon isotopes. This indicates that the N=14 neutron subshell is present in the oxygen isotopes but disappears in the boron, carbon, and nitrogen isotopic chains. The SM calculations using the YSOX interaction show the same trend as the VS-IMSRG results, whereas the N=14 shell gaps in 21N and 22O calculated by SM are significantly larger than those obtained from VS-IMSRG. Notably, the N=16 sub-shell is present in the boron, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen isotopic chains and gradually decreases from 24O to 21B. Moreover, the N=16 shell gap calculated by SM using the YSOX interaction was significantly larger than that calculated by VS-IMSRG. Additionally, the N=16 shell gap calculated by VS-IMSRG using the N3LO+3N(lnl) interaction is generally larger than that calculated using the EM1.8/2.0 and N4LO+3N(lnl) interactions. Correspondingly, the energy spectra exhibited higher excitation energies, particularly in 24O, as discussed above.

To further understand the contribution of the 3N force to the shell evolution, Fig. 5 shows the VS-IMSRG calculations using the full NN + 3N EM1.8/2.0 interaction (solid lines) compared with the VS-IMSRG calculations without the 3N force (dashed lines). As shown in Fig. 5, the 3N force enhances the N=14 shell gap in the oxygen isotopes while reducing the N=16 shell gap in the boron, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen isotopes. A similar trend was observed for the results using N3LO+3N(lnl) and N4LO+3N(lnl) interactions.

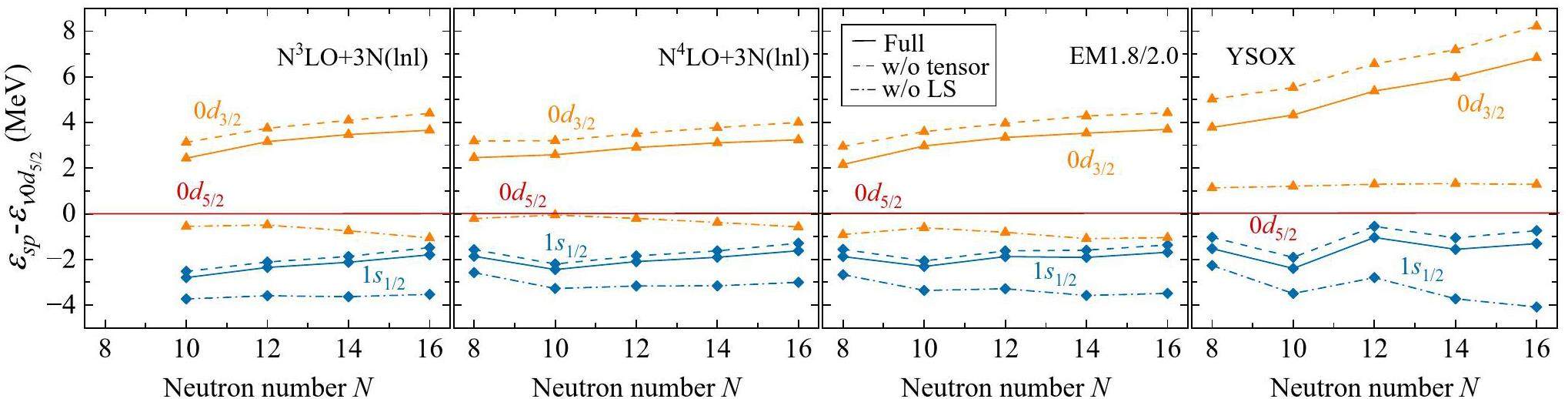

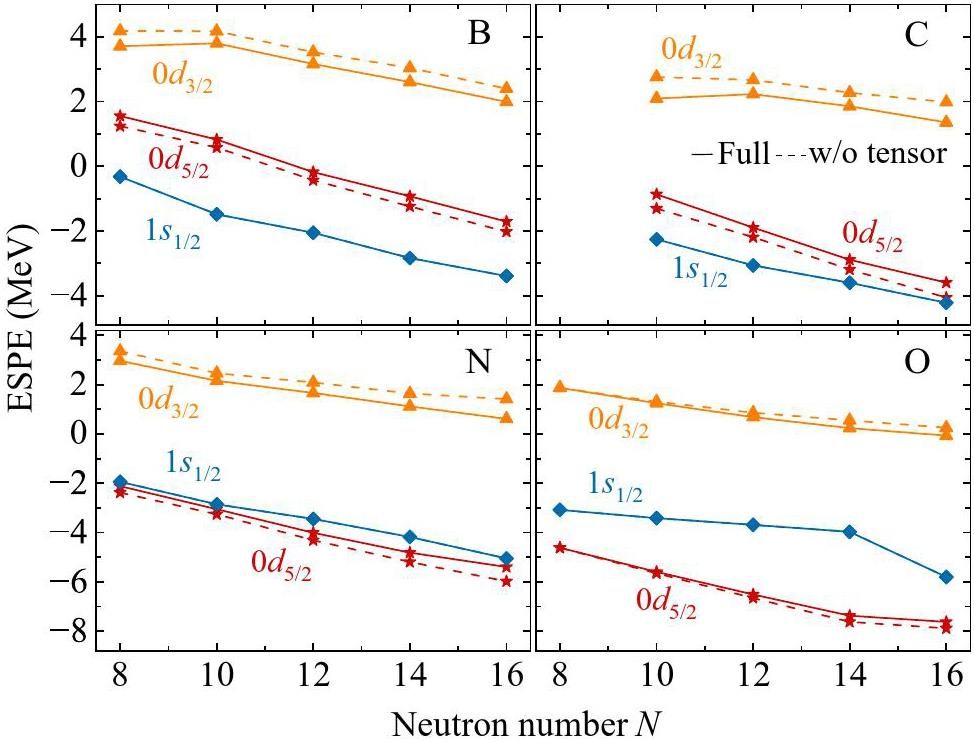

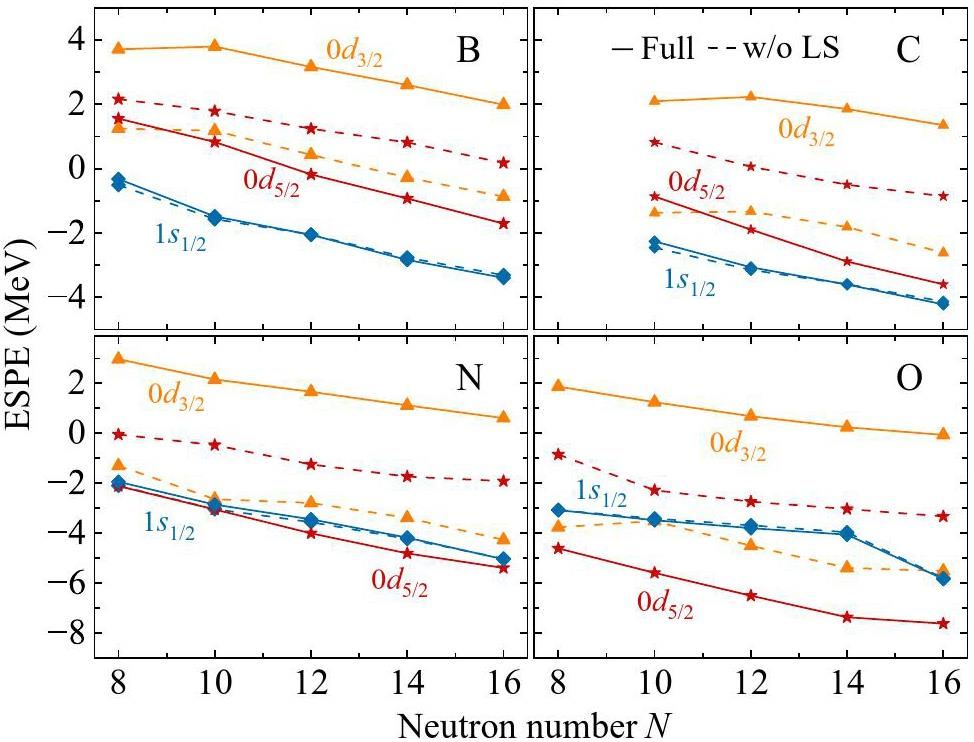

To analyze the roles of different components of the interaction in shell evolution, we employed the spin-tensor decomposition method [72-74] to decompose the effective interaction derived from VS-IMSRG into central, tensor, and spin-orbit (LS) parts. First, we conducted systematic calculations for boron isotopes and compared the contributions of different components of the interaction derived from VS-IMSRG across three sets of χEFT NN + 3N interactions: N3LO+3N(lnl), N4LO+3N(lnl), and EM1.8/2.0. We also compared the results with the SM calculations using the YSOX interaction. As shown in Fig. 6, the solid lines represent the results with the full interaction, the dashed lines represent the results without the contribution of the tensor force, and the dot-dashed lines represent the results without the contribution of the two-body LS part. In our VS-IMSRG calculations, we can see that the tensor force slightly lowers the ESPE of the ν0d3/2 orbital relative to the ν0d5/2 orbital, whereas the two-body LS component increases the ESPE of both the ν0d3/2 and ν1s1/2 orbits relative to the ν0d5/2 orbital. Moreover, the contributions of the tensor force and the two-body LS part were similar across the three sets of NN + 3N forces. Additionally, SM calculations using the YSOX interaction demonstrated the same trend as the VS-IMSRG results, although the strength of the tensor force and the two-body LS force showed minor differences. Next, we present the contributions of the different components of the interactions in various isotopes. For clarity, we only show the results calculated by VS-IMSRG using the EM1.8/2.0 interaction. In Fig. 7, the solid and dashed lines represent the ESPE with and without the contribution of the tensor force, respectively. It can be seen that the tensor force only slightly reduces the N=16 shell gap for all the isotopes. Fig. 8 compares the results obtained with and without the two-body LS part. The two-body LS part significantly lowers the ESPE of the ν0d5/2 orbital and causes inversion of the ν1s1/2 and ν0d5/2 orbits in oxygen isotopes compared to boron and carbon isotopes. This inversion is the origin of the N=14 shell gap in the oxygen isotopes. In addition, the two-body LS part significantly increases the ESPE of the ν0d3/2 orbital, leading to the appearance of the N=16 sub-shell.

In Ref. [4], the inversion between the neutron ν1s1/2 and ν0d5/2 orbits in 15C and 17O is depicted by analyzing the monopole matrix elements of the YSOX interaction, assuming that, from 15C to 17O, the proton

Conclusion

Utilizing three sets of chiral NN + 3N interactions, EM1.8/2.0, N3LO+3N(lnl), and N4LO+3N(lnl), we present ab initio VS-IMSRG calculations for neutron-rich boron, carbon, and nitrogen isotopes. We systematically calculated and predicted the low-lying spectra of these nuclei. For comparison, we also performed SM calculations using the YSOX interaction. Based on the calculated spectra and effective single-particle energies, we studied the evolution of N=14 and N=16 shell gaps. Our results suggest that the N=14 neutron subshell is present in the oxygen isotopes but collapses in the boron, carbon, and nitrogen isotopic chains. Furthermore, the N=16 sub-shell is predicted to be present in boron, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen isotopes, but its size gradually decreases from 24O to 21B. Additionally, we investigated the roles of the different components of the interaction in shell evolution by employing the spin-tensor decomposition method. We find that the two-body spin-orbit force plays a significant role in the formation of the N=14 and N=16 shell gaps. In general, our ab initio VS-IMSRG calculations agree well with the available experimental data, and theoretical predictions for these nuclei will be helpful for future experiments.

Mass systematics for a=29–44 nuclei: The deformed A~32 region

. Phys. Rev. C 41, 1147-1166 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.41.1147The shell model as a unified view of nuclear structure

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 427-488 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.77.427Nuclear magic numbers: New features far from stability

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 61, 602-673 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2008.05.001Evolution of shell structure in exotic nuclei

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 92,Low-lying neutron intruder state in 13B and the fading of the N=8 shell closure

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102,Precision mass measurements of 58-63Cr: Nuclear collectivity towards the N=40 island of inversion

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120,Prolate-spherical shape coexistence at N=28 in 44S

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105,Quadrupole collectivity in neutron-rich fe and cr isotopes

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110,Ab initio calculations for well deformed nuclei: 40Mg and 42Si

. Phys. Lett. B 848,Ab initio calculations for configuration-coexisting states in 45S: An extension from 43S

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Masses of exotic calcium isotopes pin down nuclear forces

. Nature 498, 346 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12226Evidence for a new nuclear ’magic number’ from the level structure of 54ca

. Nature 502, 207 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12522Unbound excited states of the N=16 closed shell nucleus 24O

. Phys. Rev. C 92,N=14 shell closure in 22O viewed through a neutron sensitive probe

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96,Experimental study of intruder components in light neutron-rich nuclei via single-nucleon transfer reaction

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 31, 20 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-020-0731-yN=14 and 16 shell gaps in neutron-rich oxygen isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 69,One-neutron removal measurement reveals 24O as a new doubly magic nucleus

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102,N=16 spherical shell closure in 24O

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109,Disappearance of the N=14 shell gap in the carbon isotopic chain

. Phys. Rev. C 78,Disappearance of the N=14 shell

. Phys. Rev. C 80,Shell evolution in neutron-rich carbon isotopes: Unexpected enhanced role of neutron-neutron correlation

. Nucl. Phys. A 883, 25-34 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2012.04.003Cross-shell states in 15c: A test for p-sd interactions

. Phys. Lett. B 845,In-beamγ-ray spectroscopy of the neutron-rich nitrogen isotopes 19-22N

. Phys. Rev. C 77,Nuclear structure study of 19,21N nuclei by γspectroscopy

. Phys. Rev. C 82,Structure of 22N and the N=14 subshell

. Phys. Rev. C 83,Neutron skin and signature of the n = 14 shell gap found from measured proton radii of 17-22N

. Phys. Lett. B 790, 251-256 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2019.01.024Quasifree neutron knockout reaction reveals a small s-orbital component in the borromean nucleus 17B

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126,Halo structure of the neutron-dripline nucleus 19B

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124,Observation of a large reaction cross section in the drip-line nucleus 22C

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104,One-neutron halo structure in 15C

. Phys. Rev. C 69,Proton distribution radii of 12-19C illuminate features of neutron halos

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117,First observation of 20B and 21B

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121,Unbound 28o, the heaviest oxygen isotope observed: a cutting-edge probe for testing nuclear models

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 21 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01373-wShell-model study of boron, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen isotopes with a monopole-based universal interaction

. Phys. Rev. C 85,Gamow-teller transitions and magnetic properties of nuclei and shell evolution

. Phys. Rev. C 67,Exotic magnetic properties in 17C

. Phys. Rev. C 78,Excitation spectra of the heaviest carbon isotopes investigated within the cd-bonn gamow shell model

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Continuum effect in resonance spectra of neutron-rich oxygen isotopes

. Chinese Phys. C 42,Spectroscopic factors of resonance states with the gamow shell model

. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 67,Systematic analysis of neutron-rich carbon isotopes

. Nucl. Phys. A 719, C312-C315 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(03)00939-4Proton radii of be, b, and c isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 91,Ab initio no-core shell model study of neutron-rich 18,19,20c isotopes

. Nucl. Phys. A 1029,Ab initio no-core shell model study of 10-14B isotopes with realistic NN interactions

. Phys. Rev. C 102,Ab initio no-core shell model study of neutron-rich nitrogen isotopes

. Prog. Theor. Exp. Phys. 2019,Ab initio no core shell model

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys 69, 131-181 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2012.10.003Quantum monte carlo methods for nuclear physics

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 1067-1118 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.87.1067Coupled-cluster computations of atomic nuclei

. Rep. Prog. Phys 77,Ab initio gamow in-medium similarity renormalization group with resonance and continuum

. Phys. Rev. C 99,Deformed in-medium similarity renormalization group

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Ab initio predictions link the neutron skin of 208pb to nuclear forces

. Nat. Phys. 18, 1196 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-022-01715-8Recent progress in gamow shell model calculations of drip line nuclei

. Physics 3, 977-997 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/physics3040062Natural orbital description of the halo nucleus 6he

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 28, 179 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-017-0332-6In-medium similarity renormalization group for open-shell nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 85,The in-medium similarity renormalization group: A novel ab initio method for nuclei

. Phys. Rep. 621, 165-222 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2015.12.007Nucleus-dependent valence-space approach to nuclear structure

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118,Investigation of isospin-symmetry breaking in mirror energy difference and nuclear mass with ab initio calculations

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Ab initio calculations of anomalous seniority breaking in the πg9/2 shell for the N=50 isotones

. Phys. Lett. B 858,Ab initio valence-space in-medium similarity renormalization group calculations for neutron-rich p, cl, and k isotopes*

. Chinese Phys. C 48,Improved nuclear matter calculations from chiral low-momentum interactions

. Phys. Rev. C 83,Exploring sd-shell nuclei from two- and three-nucleon interactions with realistic saturation properties

. Phys. Rev. C 93,Novel chiral hamiltonian and observables in light and medium-mass nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Discrepancy between experimental and theoretical β-decay rates resolved from first principles

. Nat. Phys. 15, 428-431 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-019-0450-7Medium-mass nuclei with normal-ordered chiral NN+3N interactions

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109,Magnus expansion and in-medium similarity renormalization group

. Phys. Rev. C 92,Thick-restart block lanczos method for large-scale shell-model calculations

. Comput. Phys. Commun. 244, 372-384 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2019.06.011Neutron-unbound excited states of 23N

. Phys. Rev. C 95,Structure and 2p decay mechanism of 18mg

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 107 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01479-1First evidence for a virtual 18b ground state

. Phys. Lett. B 683, 129-133 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2009.12.016Magic numbers in exotic nuclei and spin-isospin properties of the NN interaction

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87,Contribution of chiral three-body forces to the monopole component of the effective shell-model hamiltonian

. Phys. Rev. C 100,Matrix elements of the nucleon-nucleon potential for use in nuclear-structure calculations

. Nucl. Phys. A 121, 241-278 (1968). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(68)90419-3Spin-tensor decomposition of nuclear effective interactions

. Phys. Lett. B 47, 110-114 (1973). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(73)90582-0Single-particle energies in neutron-rich nuclei by shell model sum rule

. Phys. Rev. C 74,The authors declare that they have no competing interests.