Introduction

Mapping the phase diagram of quantum chromodynamics (QCD)is a primary objective in nuclear physics, which involves chiral and deconfinement phase transitions related to the transformation of quark-gluon plasma to hadronic matter [1]. The calculations from lattice QCD and hadron resonance gas (HRG) model indicate that a smooth crossover tranformation occurs at high temperatures and small chemical potentials [2-8]. Furthermore, studies on effective quark models [9-23], the Dyson-Schwinger equation approach [24-29], the functional renormalization group theory [30-32] and machine learning [33] suggest that a first-order chiral phase transition occurs at large chemical potentials.

The fluctuations and correlations of conserved charges (baryon number B, electric charge Q, and strangeness S) are sensitive observables for studying the phase transitions of strongly interacting matter [34, 35]. The net proton (proxy for net baryon) cumulants measured in the beam energy scan (BES) program at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) [36-42] has inspired extensive studies on QCD phase transition, particularly the QCD critical endpoint (CEP). More impressively, the distributions of the net proton number at the center-of-mass energy

The experimental results at 3 GeV and below necessitate studies on the effect of hadronic interactions on the fluctuations of conserved charges at lower energies [43-46]. The nuclear liquid-gas phase transition (LGPT) may be involved at lower collision energies [47-63].

A van der Waals model was used to study the high-order distributions of the net baryon number in both pure and mixed phases of the LGPT[64-66]. The second-order susceptibility of the net baryon number for positive- and negative-parity nucleons was examined near the chiral and nuclear liquid-gas phase transitions using a double-parity model, in which both the chiral phase transition and nuclear LGPT are effectively included [45]. The net baryon kurtosis and skewness were considered in the nonlinear Walecka model to analyze the experimental signals at lower collision energies [55, 56]. The hyperskewness and hyperkurtosis of the net baryon number were recently calculated to explore the relationship between nuclear LGPT and experimental observables [67].

Because the interactions among hadrons dominate the density fluctuations in lower-energy regimes (below 3 GeV), the BES program at collision energies lower than 7.7 GeV is expected to provide detailed information on the phase structure of strongly interacting matter. Additionally, relevant experiments have been planned at the High Intensity Heavy-ion Accelerator Facility (HIAF). Meanwhile, the HADES collaboration at the GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung planned to measure the higher-order net proton and net charge fluctuations in the central Au + Au reactions at collision energies ranging from 0.2 A GeV to 1.0 A GeV to probe the LGPT region [68]. These experiments are significant for investigating nuclear liquid-gas and chiral phase transitions through density fluctuations.

In addition to the fluctuations in conserved charges, the correlations between different conserved charges provide important information for exploring phase transitions. The correlations of conserved charges or off-diagonal susceptibilities have been calculated to study the chiral and deconfinement phase transitions at high temperatures in lattice QCD and some effective quark models (e.g., [69-75]). However, correlations between the net baryon number and electric charge in nuclear matter and their relationship with nuclear LGPT, which are useful for diagnosing the phase diagram of strongly interacting matter at low temperatures, have not yet been explored. In this study, we explored the correlations between the net baryon number and electric charge up to the sixth order in nuclear matter using the nonlinear Walecka model. The characteristic behaviors of correlations evoked by the nucleon-nucleon interaction, both near and far away from the nuclear LGPT, were obtained. These results are expected to aid future analyses of chiral phase transitions, nuclear LGPT, and related experimental signals.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we introduce formulas to describe the correlations between conserved charges and the nonlinear Walecka model. In Sect. 3, we illustrate the numerical results for the correlation between the net baryon number and electric charge. Finally, a summary is presented in Sect. 4.

Theoretical descriptions

The fluctuations and correlations of conserved charges are related to the equation of state of a thermodynamic system. In the grand canonical ensemble of strongly interacting matter, the pressure is the logarithm of the partition function [76]:

The Lagrangian density for the nucleon–meson system in the nonlinear Walecka model [54, 78] is

The thermodynamic potential can be derived in the mean-field approximation as

Minimizing the thermodynamical potential

| b | c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10.329 | 5.423 | 0.95 | 0.00692 | -0.0048 |

Results and discussion

In this section, we present the numerical results for the correlation between the net baryon number and electric charge in the nonlinear Walecka model. To simulate the physical conditions in the BES program at RHIC STAR, the isospin asymmetric nuclear matter was considered in the calculation with the constraint ρQ/ρB=0.4. In the present Walecka model, strange baryons were not included; thus, the strangeness condition ρS=0 was automatically satisfied. ρQ/ρB = 0.4 might deviate slightly owing to isospin dynamics. The influence of different isospin asymmetries on the fluctuations and correlations of conserved charges will be explored in detail in a separate study.

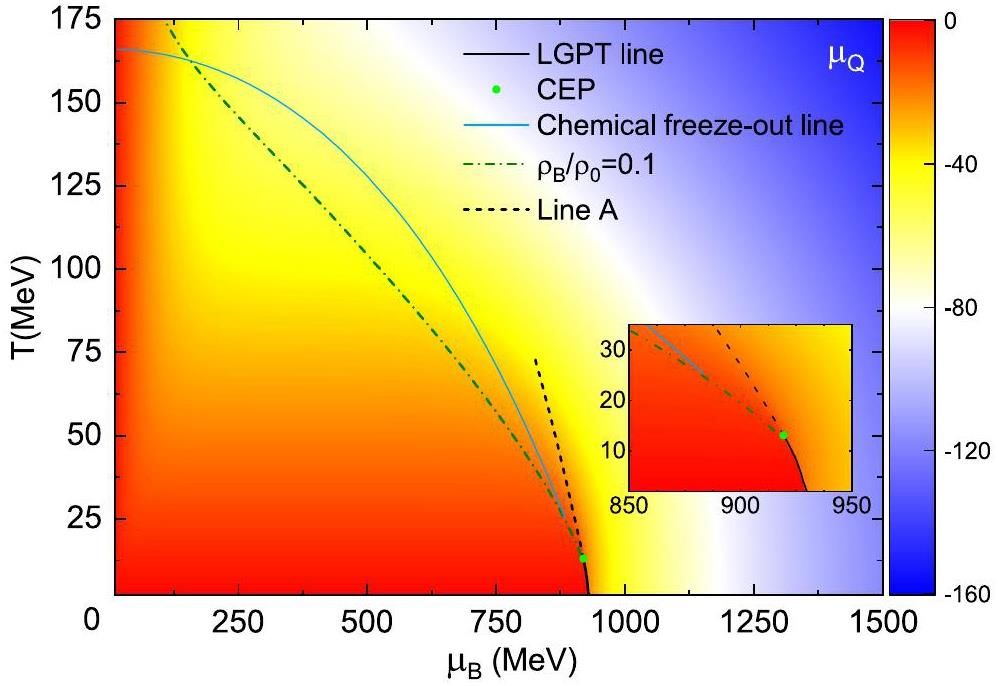

The correlations between the baryon number and electric charge are related to the baryon (μB) and isospin μQ (

Additionally, “Line A” can be defined by the maximum point of

For convenience, in the subsequent discussion of the experimental observables, we include a plot of the chemical freeze-out line fitted to the experimental data at high energies in Fig. 1 [79], which can be described by

It should be noted that the trajectories of the present relativistic heavy-ion collisions do not pass through TC of nuclear LGPT. It is still not known how far the realistic chemical freeze-out line is from the critical region at the present time. However, similar to the chiral phase transition of quarks, the existence of nuclear LGPT affects the fluctuation and correlation of the net baryon and electric charge numbers in the region not adjacent to the critical endpoint in intermediate-energy heavy-ion collision experiments. The numerical results for the parameterized chemical freeze-out line in this study can be used as a reference. The realistic chemical freeze-out conditions at intermediate and low energies will be extracted in future heavy-ion collision experiments. The contribution from LGPT needs to be considered when analyzing the experimental data.

Figure 1 shows that the value of

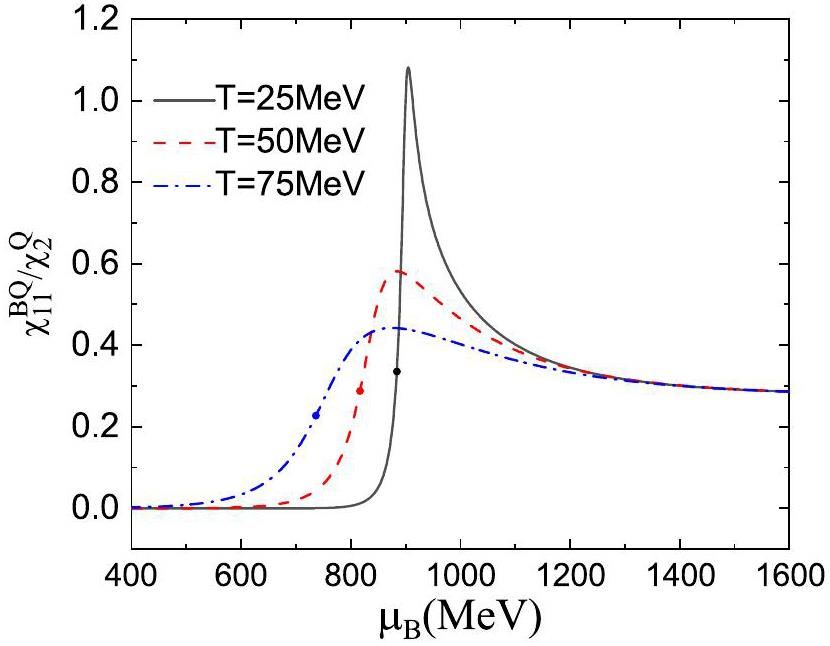

Figure 2 shows the second-order correlation between the baryon number and electric charge,

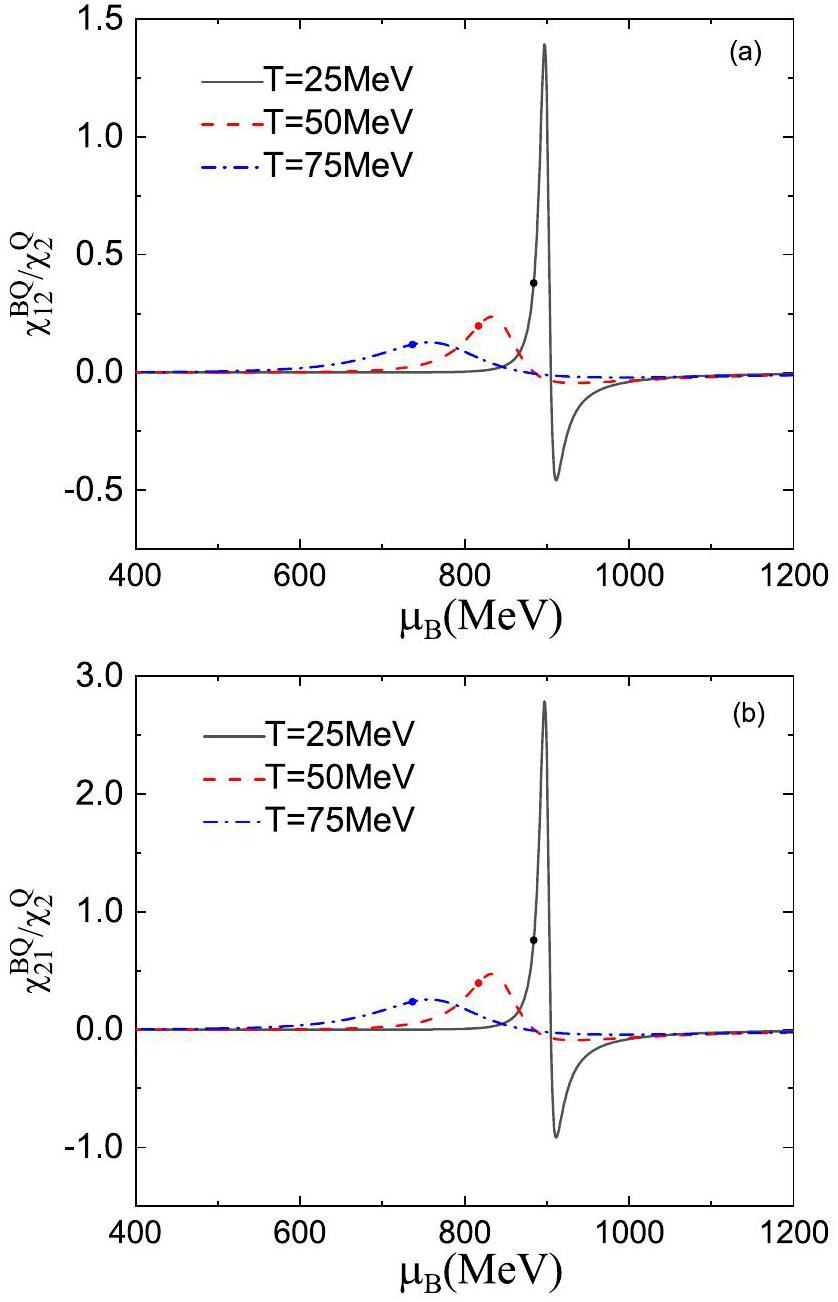

Figure 3 shows the third-order correlations

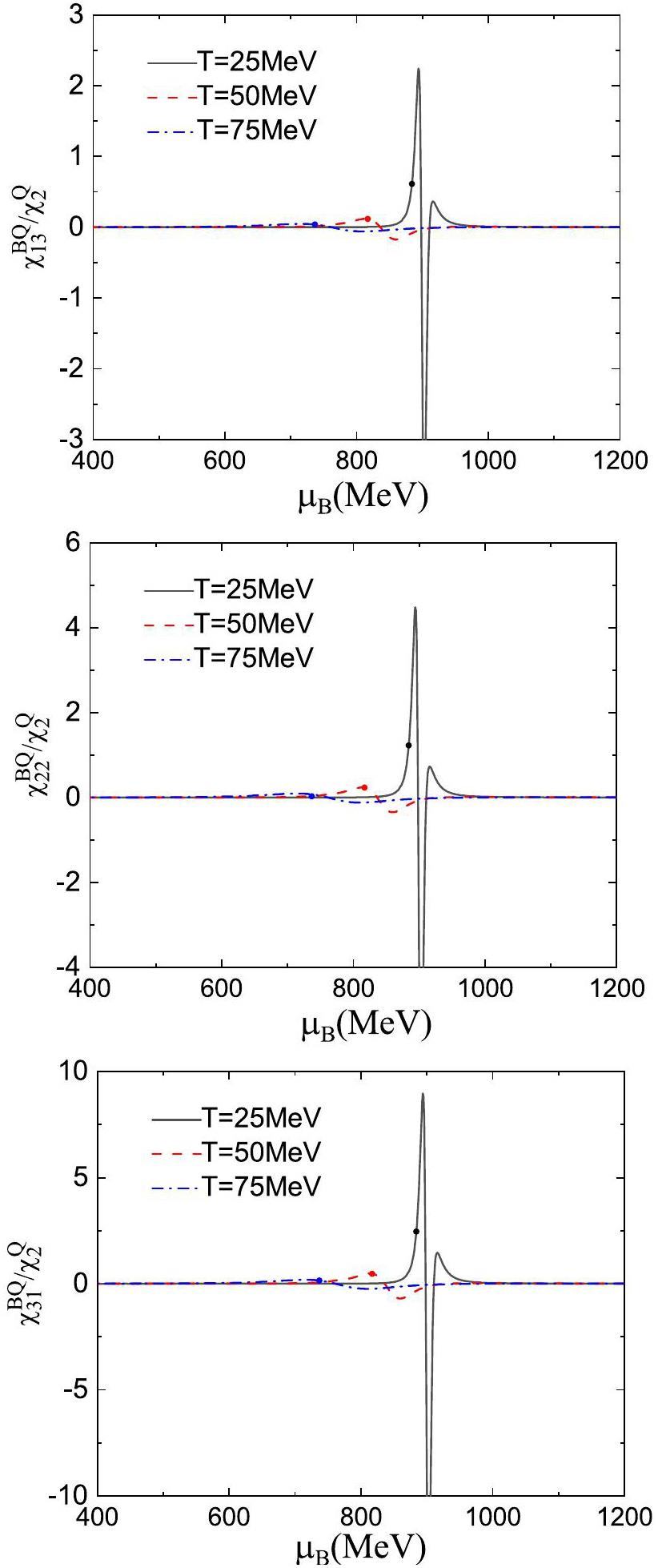

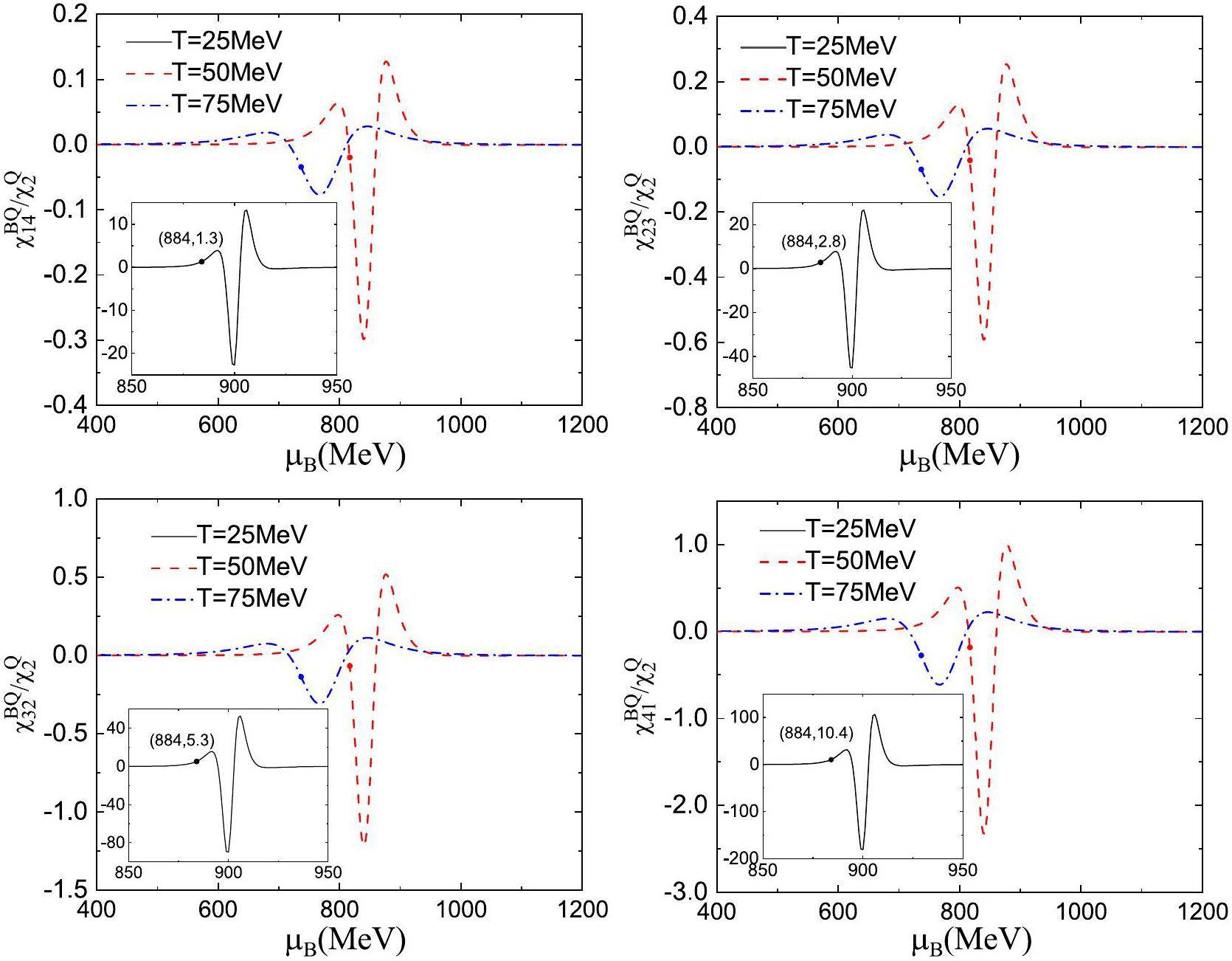

In Fig. 4, we plot the fourth-order correlations between the baryon number and electric charge:

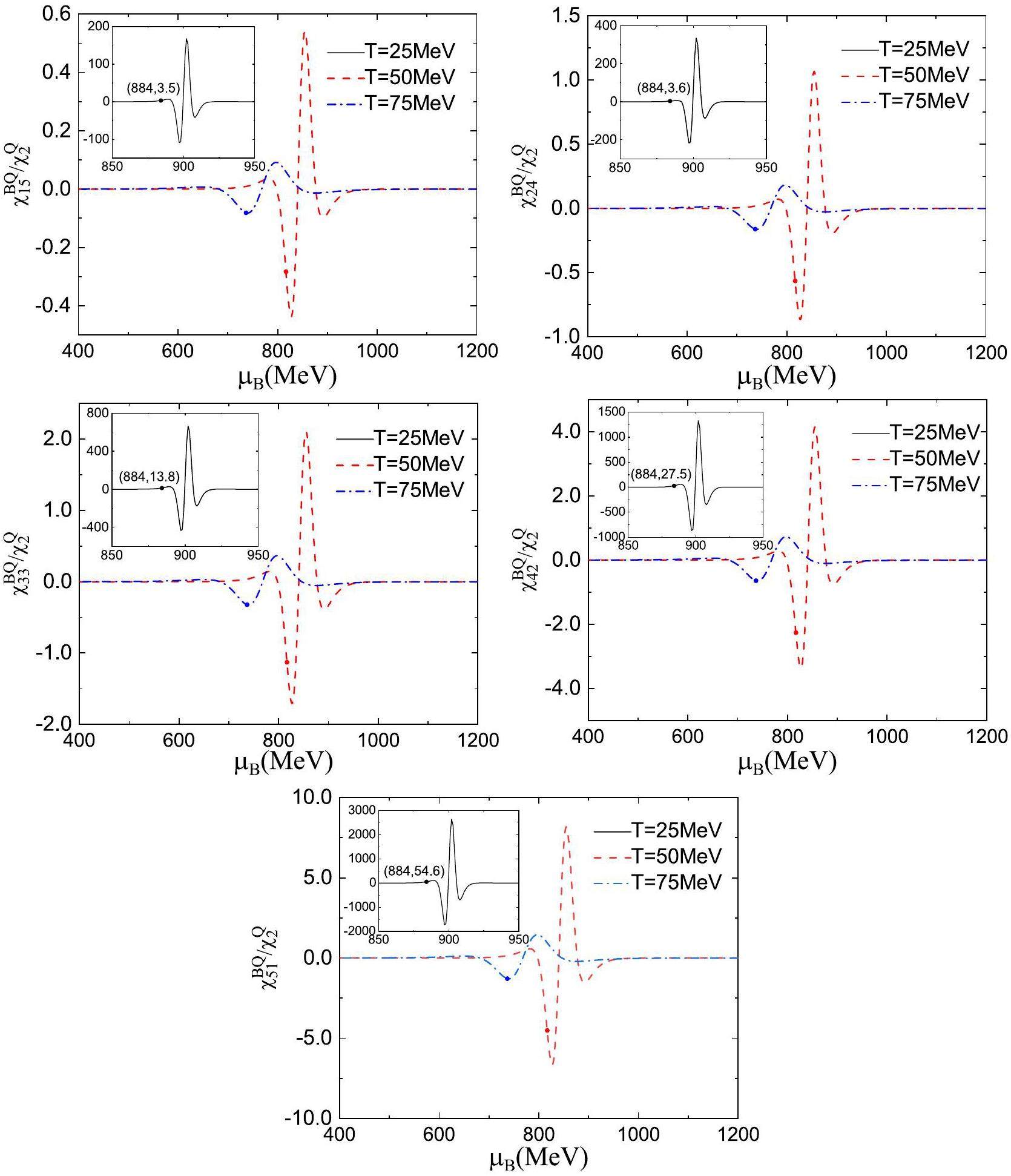

Figure 5 presents the fifth-order correlations between the baryon number and electric charge,

Figure 6 shows the sixth order correlations of the baryon number and electric charge, that is,

For a given order of correlations, the numerical results shown in Fig. 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 indicates that the signals become stronger when taking the higher-order partial derivatives of the baryon chemical potential. Additionally, we examined the pure baryon number fluctuation and found that its highest sensitivity was of the same order as the LGPT critical endpoint, possibly because the baryon number fluctuation includes both proton and neutron contributions. However, the electric charge fluctuation involves the isospin density

In addition, a comparison of the results shown in Fig. 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 shows that the rescaled higher-order correlations fluctuate more strongly near the phase transition region, whereas the lower-order correlations at high temperatures are larger than most of the higher-order correlations away from the phase transition region. A similar phenomenon occurs in the correlations of conserved charges in quark matter [74]. According to the fluctuations of net baryon number [55, 67] and the correlations between net baryon number and electric charge in this study, the fluctuations and correlations of conserved charges have similar organizational structures for nuclear and quark matter. This is primarily attributed to the fact that the two phase transitions belong to the same universal class, and both describe the interaction of matter with temperature- and chemical-potential-dependent fermion masses.

Because the QCD phase transition and nuclear LGPT possibly occur sequentially from high to low temperatures (even if LGPT is not triggered), the energy-dependent behaviors of the fluctuations and correlations can be referenced to determine the phase transition signals of the strongly interacting matter. Although the latest reported BES II high-precision data at 7.7-3.9 GeV do not display a drastic change in the net baryon number kurtosis, stronger fluctuation signals may appear in heavy-ion experiments with collision energies lower than 7.7 GeV. Furthermore, in the hadronic interaction dominant evolution with collision energies lower than the threshold of the generation of QGP, the nuclear interaction and phase structure of LGPT will dominate over the behavior of fluctuations and correlations of conserved charges. The nature of the changes in fluctuations and correlations with decreasing collision energy during experiments requires investigation.

Summary

Fluctuations and correlations between conserved charges are sensitive probes for investigating the phase structure of strongly interacting matter. In this study, we used the non-linear Walecka model to calculate the correlations between the net baryon number and electric charge up to the sixth order, which originated from hadronic interactions in nuclear matter and explored their relationship with the nuclear liquid-gas phase transition.

The calculation indicated that the correlations between the net baryon number and electric charge gradually became stronger from the high-temperature region to the critical region of the nuclear LGPT. In particular, the correlations were significant at the location where the σ field or nucleon mass changed rapidly near the critical region. Similar behavior was observed for the chiral crossover phase transition of quark matter, primarily because of the similar dynamic mass evolution and same universal class of the chiral phase transition of quark matter and the liquid-gas phase transition of nuclear matter.

Compared to the lower-order correlations, the higher-order correlations fluctuated more strongly near the phase transition region, whereas the rescaled lower-order correlations were relatively stronger than most of the higher-order correlations away from the phase transition region at high temperatures. At the chemical freeze-out for each temperature, the calculation indicated that

Properties of QCD matter: a review of selected results from ALICE experiment

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 219 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01583-2The order of the quantum chromodynamics transition predicted by the standard model of particle physics

. Nature 443, 675-678 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05120Chiral crossover in QCD at zero and non-zero chemical potentials

. Phys. Lett. B 795, 15 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2019.05.013Freeze-Out Parameters: Lattice Meets Experiment

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111,Equation of state in (2+1)-flavor QCD

. Phys. Rev. D 90,Skewness and kurtosis of net baryon-number distributions at small values of the baryon chemical potential

. Phys. Rev. D 96,Full result for the QCD equation of state with flavors

. Phys. Lett. B 730, 99 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2014.01.007QCD Crossover at Finite Chemical Potential from Lattice Simulations

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125,Chiral effective model with the Polyakov loop

. Phys. Lett. B 591, 277 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2004.04.027Phases of QCD: Lattice thermodynamics and a field theoretical model

. Phys. Rev. D 73,Phase diagram and critical properties within an effective model of QCD: the Nambu-Jona-Lasinio model coupled to the Polyakov loop

. Symmetry 2, 1338-1374 (2010). https://doi.org/10.3390/sym20313382+1 flavor Polyakov-Nambu-Jona-Lasinio model at finite temperature and nonzero chemical potential

. Phys. Rev. D 77,Theta vacuum and entanglement interaction in the three-flavor Polyakov-loop extended Nambu-Jona-Lasinio model

. Phys. Rev. D 85,Deconfinement, chiral symmetry restoration and thermodynamics of (2+1)-flavor hot QCD matter in an external magnetic field

. Phys. Rev. D 89,Phase diagram of holographic thermal dense QCD matter with rotation

. J. High Energy Phys. 04, 115 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP04(2023)115Baryon number fluctuations and the phase structure in the PNJL model

. Eur. Phys. J. C 78, 138 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-018-5636-0Thermodynamics of (2+1)-flavor QCD: Confronting models with lattice studies

. Phys. Rev. D 81,Quark number fluctuations in the Polyakov loop-extended quark-meson model at finite baryon density

. Phys. Rev. C 83,Three-dimensional QCD phase diagram with a pion condensate in the NJL model

. Phys. Rev. D 104,Quarkyonic phase from quenched dynamical holographic QCD model

. J. High Energy Phys. 2020, 73 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP03(2020)073Presence of a critical endpoint in the QCD phase diagram from the net-baryon number fluctuations

. Phys. Rev. D 98,Properties of the phase diagram from the Nambu-Jona-Lasino model with a scalar-vector interaction

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 166 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01559-2Inhomogeneous chiral condensation under rotation in the holographic QCD

. Phys.Rev. D 106,QCD phase transitions using the QCD Dyson-Schwinger equation approach

. Nucl. Tech. (in Chinese) 46Phase Diagram and Critical End Point for Strongly Interacting Quarks

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106,Phase diagram and thermal properties of strong-interaction matter

. Phys. Rev. D 93,QCD phase structure from functional methods

. Phys. Rev. D 102,Phase structure of three and four flavor QCD

. Phys. Rev. D 90,Locate QCD critical end point in a continuum model study

. J. High Energy Phys. 1407, 014 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP07(2014)014QCD phase structure at finite temperature and density

. Phys. Rev. D 101,Fluctuation-induced modifications of the phase structure in (2+1)-flavor QCD

. Phys. Rev. D 96,Hyper-order baryon number fluctuations at finite temperature and density

. Phys. Rev. D 104,Phase Transition Study Meets Machine Learning

. Chin. Phys. Lett. 40,Non-Gaussian Fluctuations near the QCD Critical Point

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102,Sign of Kurtosis near the QCD Critical Point

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107,Higher Moments of Net Proton Multiplicity Distributions at RHIC

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105,Energy Dependence of Moments of Net-Proton Multiplicity Distributions at RHIC

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112,X.H. Properties of QCD matter: review of selected results from the relativistic heavy ion collider beam energy scan (RHIC BES) program

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 214 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01591-2Search for the QCD critical point with fluctuations of conserved quantities in relativistic heavy-ion collisions at RHIC: an overview

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 28, 112 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-017-0257-0Measurement of Sequential γ Suppression in Au+Au Collisions at sNN=200GeV with the STAR Experiment

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130,Experimental study of the QCD phase diagram in relativistic heavy-ion collisions

. Nucl. Tech. (in Chinese), 46,Transport model study of conserved charge fluctuations and QCD phase transition in heavy-ion collisions

. Nucl. Tech. (In Chinese) 46Reconstruction of baryon number distributions

. Chin. Phys. C 47,Chemical freeze-out parameters via a functional renormalization group approach

. Phys. Rev. D 109,Fluctuations near the liquid-gas and chiral phase transitions in hadronic matter

. Phys. Rev. D 107,Density fluctuations in intermediate-energy heavy-ion collisions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 52 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-02201040-yNuclear spinodal fragmentation

. Phys. Rep. 389, 263 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2003.09.006Probing the Nuclear Liquid-Gas Phase Transition

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 1040 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.75.1040Evidence for Spinodal Decomposition in Nuclear Multifragmentation

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 3252 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.3252Multifragmentation of spectators in relativistic heavy-ion reactions

. Nucl. Phys. A 584, 737-756 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(94)00621-SThermodynamical features of multifragmentation in peripheral Au + Au collisions at 35AMeV

. Nucl. Phys. A 650, 329-357 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1016/S03759474(99)00097-4Multifragmentation and the phase transition: A systematic study of the multifragmentation of 1AGeV Au, La, and Kr

. Phys. Rev. C 65,Liquid to Vapor Phase Transition in Excited Nuclei

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88,Speed of sound and liquid-gas phase transition in nuclear matter

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Baryon number fluctuations induced by hadronic interactions at low temperature and large chemical potential

. Phys. Rev. D 101,The baryon number fluctuation κσ2 as a probe of nuclear matter phase transition at high baryon density

. arXiv:2307.12600v1. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2307.12600Application of Information Theory in Nuclear Liquid Gas Phase Transition

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 3617 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.3617Impact of fragment formation on shear viscosity in the nuclear liquid-gas phase transition region

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Noncongruence of the nuclear liquid-gas and deconfinement phase transitions

. Phys. Rev. C 88,Higher-order baryon number susceptibilities: Interplay between the chiral and the nuclear liquid-gas transitions

. Phys. Rev. C 96,Shear viscosity of neutron-rich nucleonic matter near its liquid-gas phase transition

. Phys. Lett. B 727, 244 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2013.10.051Traces of the nuclear liquid-gas phase transition in the analytic properties of hot QCD

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Nuclear liquid-gas phase transition with machine learning

. Phys. Rev. Res. 2,Chemical freeze-out conditions and fluctuations of conserved charges in heavy-ion collisions within a quantum van der Waals model

. Phys. Rev. C 100,van der Waals Interactions in Hadron Resonance Gas: From Nuclear Matter to Lattice QCD

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118,Higher order conserved charge fluctuations inside the mixed phase

. Phys. Rev. C 103,Fifth- and sixth-order net baryon number fluctuations in nuclear matter at low temperature

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Dynamics of critical fluctuations: Theory - phenomenology - heavy-ion collisions

. Nucl. Phys. A 1003,Fluctuations and correlations in high temperature QCD

. Phys. Rev. D 92,Correlations of conserved charges and QCD phase structure

. Chin. Phys. C 45,Diagonal and off-diagonal quark number susceptibilities at high temperatures

. Phys. Rev. D 92,Higher order fluctuations and correlations of conserved charges from lattice QCD

. J. High Energy Phys. 10, 205 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP10(2018)205Off-diagonal correlators of conserved charges from lattice QCD and how to relate them to experiment

. Phys. Rev. D 101,Fluctuations and correlations of conserved charges near the QCD critical point

. Phys. Rev. D 82,Correlation between conserved charges in Polyakov–Nambu–Jona-Lasinio model with multiquark interactions

. Phys. Rev. D 83,Thermodynamics of strong-interaction matter from lattice QCD

. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 24,Hadron resonance gas and mean-field nuclear matter for baryon number fluctuations

. Phys. Rev. C 91,Comparison of chemical freeze-out criteria in heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 73,The authors declare that they have no competing interests.