Introduction

Heavy ion reactions (HIR) provide a femtoscopic laboratory for investigating the properties of the nuclear equation of state (nEoS), particularly the nuclear symmetry energy

The nuclear (fast)fission process is a large-amplitude collective motion mode happening in the HIRs. The low-density neutron rich neck region formed in the rupture of two fission fragments provides a good condition for studying

The emissions of light particles in coincidence with fission fragments is a natural idea for exploring the symmetry energy effect and (fast)fission properties in HIRs [40, 41]. Among the probes using the light charged particles (LCPs), the yield ratio of t/3He, written as R(t/3He), has been particularly identified to probe the enriched feature of isospin dynamics in HIRs. Transport model calculations demonstrate that the R(t/3He) at intermediate-energy HIRs depends on the stiffness of

Despite of the enormous progress of the studies on the triton (t) and 3He emission, some questions remain unclear and require further studies. For example, when considering the spectra of 3He, there is an anomalous phenomenon that the yield of high energy 3He is relatively larger, compared to that of triton [73-77] or 4He [73, 75-78]. This phenomenon has been called “3He-puzzle” [73, 74, 77]. While the energy spectra are suffering “3He-puzzle”, the yield ratio of triton and 3He is sensitive to the neutron-to-proton ratio (N/Z) of the emitting system [53, 70, 79, 80]. The excitation function of R(t/3He) measured by the FOPI collaboration [81] can not be reproduced with a single model [62]. More interestingly, the results of the INDRA experiment suggest that the triton and 3He isobars seem to dominate the neutron enrichment of the neck zone [54]. However, the existence of “3He-puzzle” in the coincidence events of LCPs and fission fragments is still an uncertain issue.

Due to the enriched but not-well-understood information carried by triton and 3He coupling to both the isospin transport and the neck emission during fission process in HIRs, we are motivated to explore the emission of these two isobars in coincidence with fission fragments by inspecting the energy spectra and the yield ratio R(t/3He) over wide angular range, and to bridge the ratio R(t/3He) and the feature of fission process, as well as to infer the slope parameter of

Experimental setup

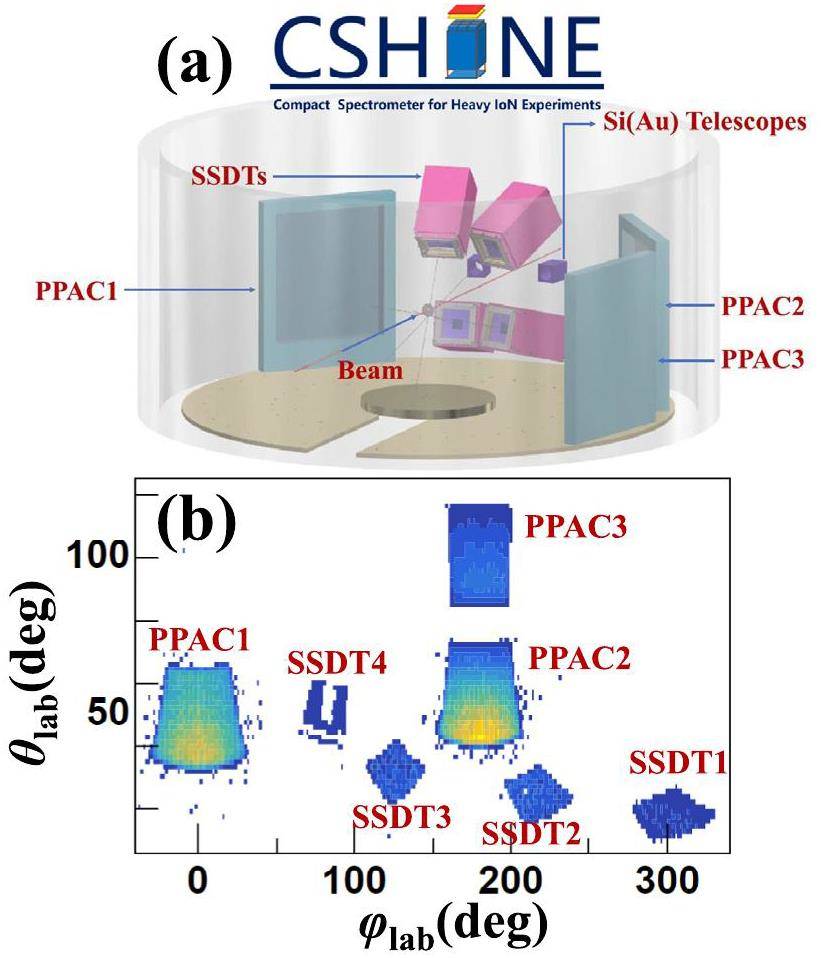

The experiment was conducted at the Compact Spectrometer for Heavy IoN Experiment (CSHINE) [82, 83], built at the final focal plane of the Radioactive Ion Beam Line at Lanzhou (RIBLL-I) [84]. The 86Kr beam of 25 MeV/u was extracted from the cyclotron of the Heavy Ion Research Facility at Lanzhou (HIRFL) [85], bombarding a natural lead target installed in the scattering chamber with the radius

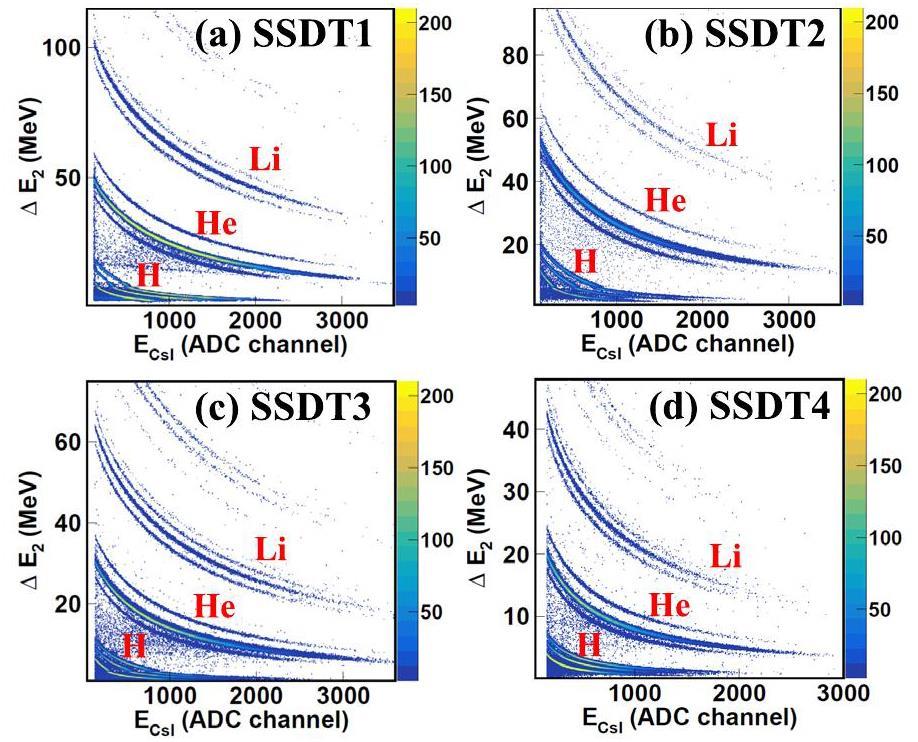

The LCPs from the reactions were measured by 4 SSDTs, covering the angular range from 10° to 60° in laboratory. Each SSDT consists of three layers, namely, one single-sided silicon-strip detector (SSSSD) for ΔE1 and one double-sided silicon strip detector (DSSSD) for ΔE2, backed by a 3× 3 CsI(Tl) crystal hodoscope with the length of 50 mm for the energy deposit E. The granularity of the SSDT is 4 mm× 4 mm, giving about 1° angular resolution. The energy resolution of the SSDT is better than 2%, and the isotopes up to Z=6 can be identified [36]. Multi hits and signal sharing are carefully treated in the track recognition, and the track recognition efficiency is about 90% [86]. Figure 2 shows the particle identification of light particles for this analysis. Panel (a) to (d) presents the scattering plot of ΔE2 - ECsI of the four SSDTs. The results show that

In order to explore the isospin properties of fission process, the fission fragments (FFs) were detected by 3 PPACs, each of which had a sensitive area of 240 mm × 280 mm [87, 88]. The perpendicular distance of the PPACs to the target is about 428 mm. The coverage of the PPACs ensures a high efficiency to measure the FFs in coincidence with the LCPs. And the trigger system is established to selected the fission events [89]. The working voltage of the PPACs can suppress the light charged particles significantly, although the specific values of mass and charge for FFs were not accurately determined. According to the previous source test results [82], the detection efficiency is almost 100% for FFs and negligibly low for light particles with the detector condition (HV=460 V) as adopted in the experiment. So, the PPACs can only be fired by heavy fragments, rather than LCPs or IMFs.

Referring to the energy loss calculations only, the projectile-like fragments (PLF) and target-like fragments (TLF) may fire the PPACs as well. However, the geometric coverage of the PPACs in the experiment suppresses the PLF and TLF. Otherwise because PLFs and TLFs are well separated in velocity (

Theoretical Model

A hybrid model by the improved quantum molecular dynamics model (ImQMD05) coupled with statistical decay afterburner (GEMINI) was used for theoretical simulation in this work. The ImQMD05 [90] was used to simulate the nucleon transport process in HIRs. And the GEMINI [91, 92] was appended to obtain the final state productions of the reactions. The ImQMD05 model is an improved version from the original quantum molecular dynamics code [93, 94], and is widely used to understand the dynamics of nuclear reactions induced by heavy ions or light nuclei at both low and intermediate energies [40, 41, 95-97]. The mean field part of the ImQMD05 model used here includes the symmetry potential energy part. And the local nuclear potential energy density functional in the ImQMD05 model is written as

| β (MeV) | ρ0 (fm-3) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -254 | 185 | 5/3 | 21.0 | -0.82 | 5.51 | 36.0 | 0.160 |

Results and Discussions

Characterizing the fission events

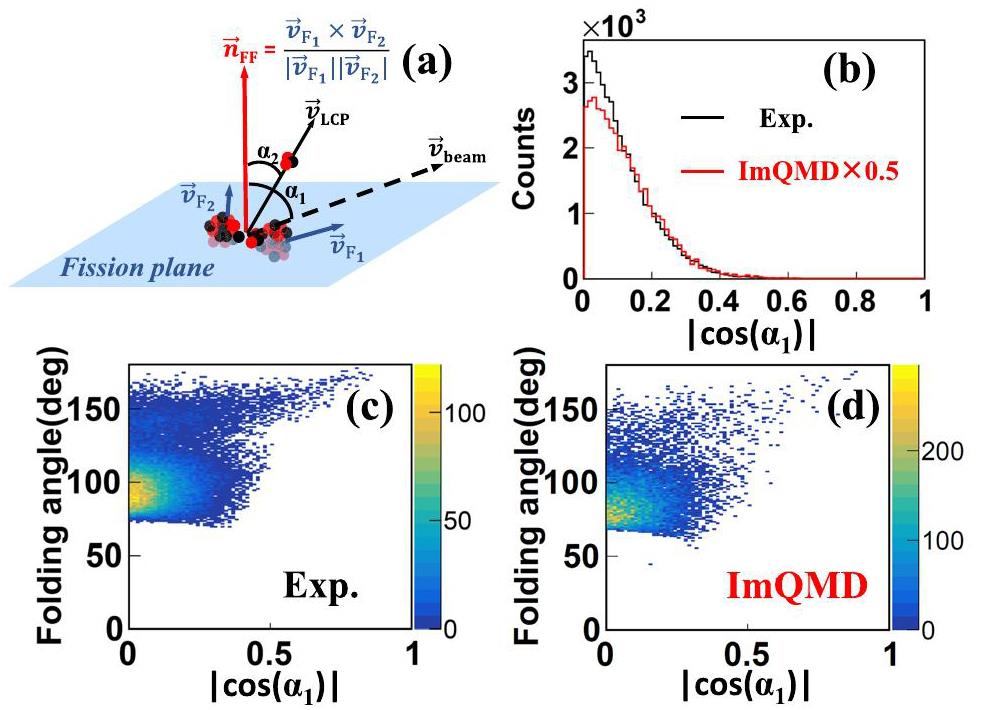

We start with the analysis of the orientation of the fission plane with respect to the beam direction. The fission plane is reconstructed by the velocity of two FFs, using

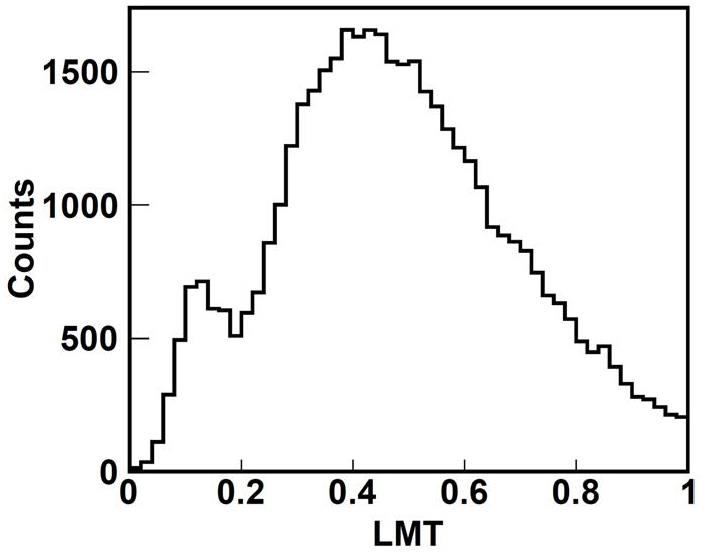

The characteristics of this rotating fissioning system was obtained using the experiment data and theoretic simulations. First, to estimate its charge and mass, the linear momentum transfer (LMT) should be estimated experimentally. Assuming a symmetric fission processes, the velocity of the fissioning system (FS) can be simply calculated by

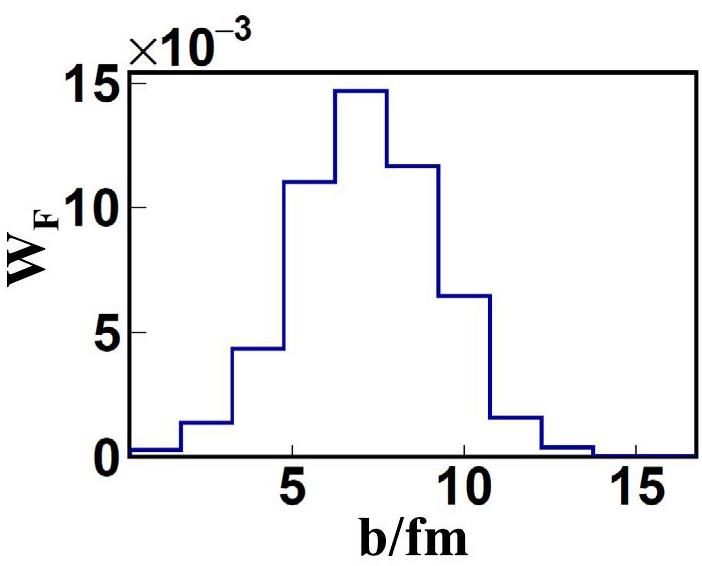

Second, to estimate the angular momentum of the rotating fission system, one needs the most probable impact parameter, which can determined by the event weigh obtained from transport model simulations filtered by experimental conditions. Defining the fission event weight by

Figure 5 shows the distribution of

The distance between the transferred part of the projectile and the mass center of the fissioning system is defined as

The angular momentum is written as

Third, to estimate the excitation energy of the rotating fission system, the moment of inertia I of a spherical nucleus with the mass

Analysis of the energy spectra of t and 3He

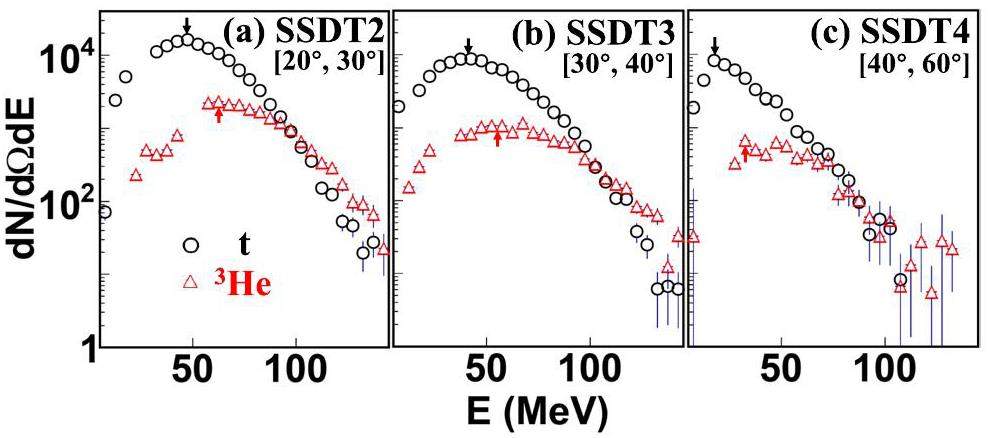

We now present the analysis of the emission of triton and 3He in the (fast)fission events. The energy spectra of LCPs in coincidence with FFs contain thermal and dynamical information of the particles emitted from the fission events. Fig. 6 presents the energy spectra of triton (open circles) and 3He (open triangles) emitted from fission events in different angular ranges corresponding to SSDTs 2 to 4. To reduce the contamination of quasi-projectiles, the data of SSDT1 covering 10-20° in the laboratory is not counted here. It is shown that the spectrum of 3He is generally harder than that of triton, leading to a larger average kinetic energy of the former. The difference between triton and 3He is more pronounced at forward angles than at large angles. This observation of “3He-puzzle” is in accordance with the previous inclusive measurements at high beam energies [73, 75-77, 81, 101-104].

The “3He-puzzle” has been interpreted by two possible scenarios: sequential decay [74] and coalescence model [78]. In the sequential decay scenario, the difference between 3He and triton is influenced by the Coulomb barrier, for which 3He is emitted at an earlier stage with high temperature to overcome the Coulomb barrier higher than that of triton [74]. In coalescence scenario, which was applied to interpret the difference between 3He and α particles [78], the former is dominantly produced by the coalescence of preequilibrium nucleons, delivering larger mean kinetic energy. These two explanations are qualitatively in agreement, supporting that 3He is predominantly emitted at earlier stage. Our experimental results show that the “3He-puzzle” exists in the events tagged by fission. It suggests that the puzzle exists in both inclusive and fission events.

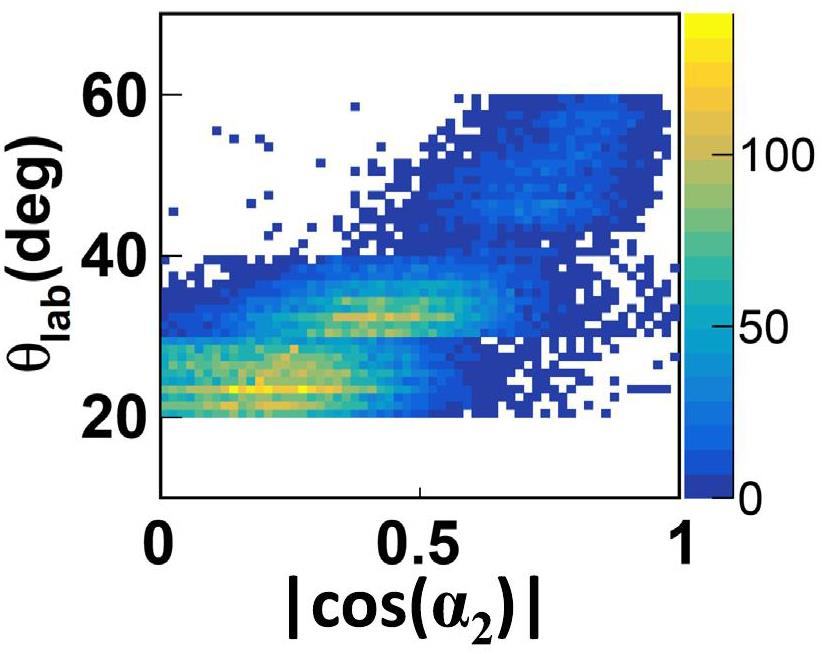

Out-of-plane emission and the effect of

Benefiting from the wide angular coverage of the SSDTs and PPACs in laboratory reference frame, the angular behavior of the particle emission can be analyzed. To compare the yields of particles with different energy spectrum behaviors and avoid the influence of the possible experimental distortion caused by the energy threshold in each SSDTs, a data adaptive energy spectrum peak cut scenario is applying. We focus on the descending part on the high energy side of the energy peak. The energy peak positions (Ep) are listed in Table 2. Meanwhile, using the energy condition

| SSDT2 | SSDT3 | SSDT4 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ep of triton (MeV) | 45 | 40 | 19 |

| Ep of 3He (MeV) | 62 | 58 | 38 |

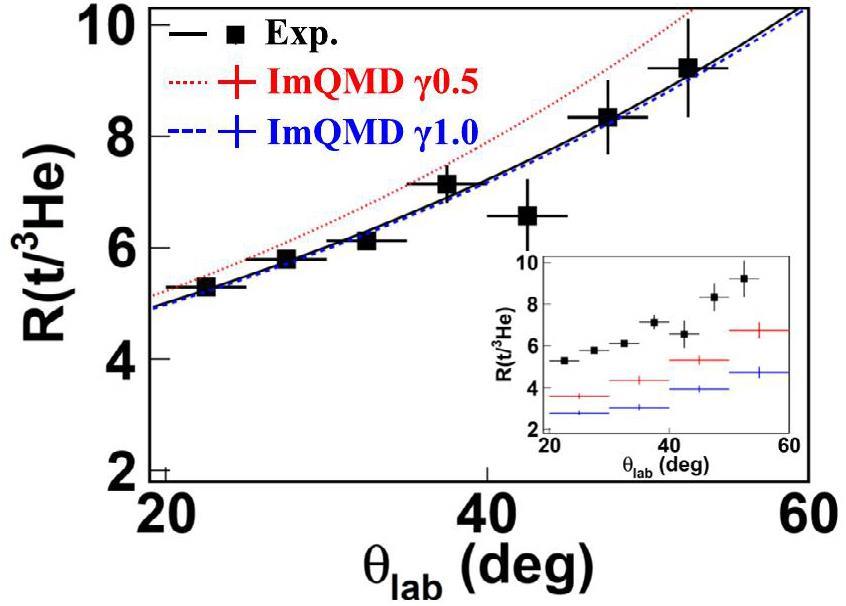

The angular distribution of R(t/3He) as a function of the polar angle in laboratory θlab is generated with events of one LCP in coincidence with two FFs, as shown in Fig. 7. The same energy threshold, geometry and folding angle cuts are applied to both experimental and simulation results. It is shown that for the wide angular range, the distribution exhibits a rising trend. This feature is consistent with the moving source picture, where the neutron richness of particle emission increases from the projectile-like source to the medium velocity source corresponding to the neck, as predicted by various transport model simulations [40, 41, 46, 48, 49, 51, 105-109], and experimentally observed in a specific angular window [42, 45, 50, 54, 79, 110-112] or a parallel velocity window [45, 79, 80, 113-118].

In order to see the symmetry energy effect, a soft (γ = 0.5) and a stiff (γ = 1.0) symmetry energy are adopted in the ImQMD05 simulations. These two γ values correspond to slope parameter of

| p0 | p1 | |

|---|---|---|

| Experiment | 1.25±0.06 | 0.018±0.002 |

| γ=0.5 | 0.75±0.08 | 0.021±0.002 |

| γ=1.0 | 0.54±0.09 | 0.018±0.002 |

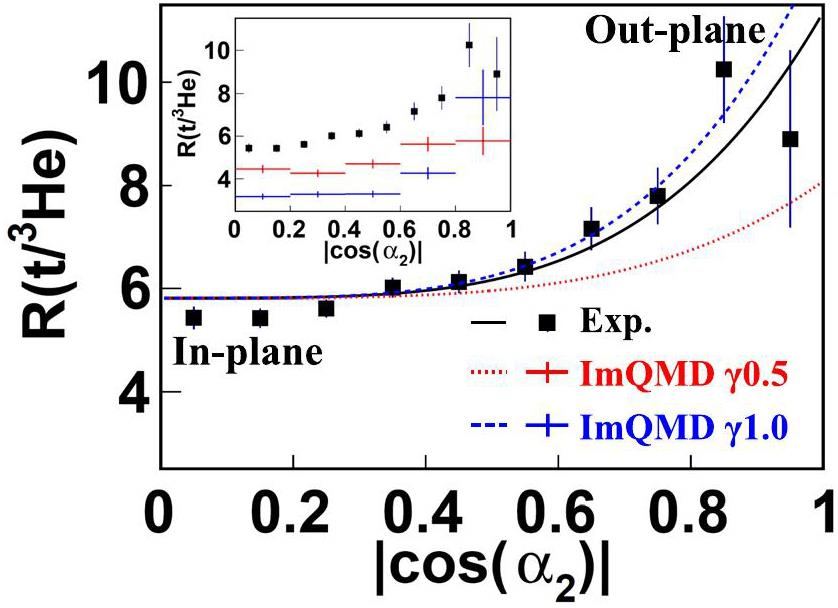

It is then motivated to go a further step to find a novel probe, of which the fission event topology is better controlled and the sensitivity on

Similarly, to describe the increasing trend of the angular distribution of

| p0 | p1 | |

|---|---|---|

| Experiment | 5.8±0.2 | 5.5±1.6 |

| γ=0.5 | 4.5±0.1 | 2.3±1.1 |

| γ=1.0 | 3.0±0.1 | 6.8±1.8 |

Figure 9 shows in addition the relationship between

Currently we do not attempt to make a fine tuning and constraint of γ parameter in the simulations, since the absolute value of R(t/3He) is not yet well reproduced, as indicated by Fig. 7 and 8. Further studies are required in transport model in order to elucidate the origin and the formation mechanism of light clusters including triton and 3He. Recently, the yield of light clusters is better reproduced by introducing Mott effect in transport model [120]. Meanwhile, the cooling process of the rotating fissioning system with similar E* and J is of high interest. We are going to make further calculations on particle emission from a rotating system with inclusion of deuteron, triton and 3He apart of neutron, proton and α particles, as done in [121]. The emission of other particles than A=3 isobars may bring significant effect to the featured distribution of the latter in the cooling process of the fissioning system.

Summary

The energy spectra and angular distributions of triton and 3He ranging from 20° to 60° in the laboratory in coincidence with fission fragments are analyzed in 25 MeV/u 86Kr +natPb reactions. It is shown that the energy spectra of 3He are generally harder than triton even in the fission events, and the effect is more pronounced at small angles. Applying a data driven energy spectrum peak cut scenario, the rising trend of angular distribution of R(t/3He) is observed in the coincident events of one LCP and two FFs, which is consistent with previous inclusive observations. The yield ratio R(t/3He) exhibits an enhancement as a function of

Progress in constraining nuclear symmetry energy using neutron star observables since GW170817

. Universe 7(6), 182 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/universe7060182Constraining neutron-star matter with microscopic and macroscopic collisions

. Nature 606, 276-280 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04750-wIsospin asymmetry in nuclei and neutron stars

. Phys. Rept. 411, 325-375 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2005.02.004Equations of state for supernovae and compact stars

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 89,Topical issue on nuclear symmetry energy

. Eur. Phys. J. A 50, 9 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2014-14009-xRecent progress and new challenges in isospin physics with heavy-ion reactions

. Phys. Rept. 464, 113-281 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2008.04.005GW170817: Observation of gravitational waves from a binary neutron star inspiral

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119,GW170817: Measurements of neutron star radii and equation of state

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121,Tidal deformabilities and radii of neutron stars from the observation of GW170817

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121,Neutron skin and its effects in heavy-ion collisions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 211 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01584-1Isotopic dependence of the yield ratios of light fragments from different projectiles and their unified neutron skin thicknesses

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 65 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01425-1Bayesian inference of the crust-core transition density via the neutron-star radius and neutron-skin thickness data

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 91 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01239-7Neutron skin thickness and its effects in nuclear reactions

. Nucl. Tech. (in Chinese) 46,New quantification of symmetry energy from neutron skin thicknesses of 48Ca and 208Pb

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 182 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01551-wConstraining nuclear symmetry energy with the charge radii of mirror-pair nuclei

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 119 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01269-1Application of machine learning to the study of QCD transition in heavy ion collisions

. Nucl. Tech. (in Chinese) 46,A perspective on describing nucleonic flow and pionic observables within the ultra-relativistic quantum molecular dynamics model

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 36, 45 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01607-xProperties of collective flow and pion production in intermediate-energy heavy-ion collisions with a relativistic quantum molecular dynamics model

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 15 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01380-xEquation of state of asymmetric nuclear matter and collisions of neutron rich nuclei

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 1644 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.78.1644Probing the density dependence of the symmetry potential with peripheral heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 71,Light clusters production as a probe to the nuclear symmetry energy

. Phys. Rev. C 68,Probing the high density behavior of nuclear symmetry energy with high-energy heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88,Circumstantial evidence for a soft nuclear symmetry energy at suprasaturation densities

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102,Probing the symmetry energy with the spectral pion ratio

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126,Probing the density dependence of the symmetry potential at low and high densities

. Phys. Rev. C 72,Isospin effects on sub-threshold kaon production at intermediate energies

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97,Probing the high-density nuclear symmetry energy with the Ξ−/Ξ0 − ratio in heavy-ion collisions at sNN≈3 GeV

, Phys. Rev. C 106,Transport approaches for the description of intermediate-energy heavy-ion collisions

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 106, 312-359 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2019.02.009Application of microscopic transport model in the study of nuclear equation of state from heavy ion collisions at intermediate energies

. Front. Phys. (Beijing) 15, 44302 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11467-020-0964-6Comparison of heavy-ion transport simulations: Collision integral in a box

. Phys. Rev. C 97,Comparison of heavy-ion transport simulations: Collision integral with pions and Δresonances in a box

, Phys. Rev. C 100,Comparison of heavy-ion transport simulations: Mean-field dynamics in box

. Phys. Rev. C 104,Long-time drift of the isospin degree of freedom in heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 95,Dynamic isovector reorientation of deuteron as a probe to nuclear symmetry energy

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115,The emission order of hydrogen isotopes via correlation functions in 30 MeV/u Ar+Au reactions

. Phys. Lett. B 825,Observing the ping-pong modality of the isospin degree of freedom in cluster emission from heavy-ion reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Correlation function studies at intermediate energies at CSHINE

, NUOVO CIMENTO C-COLLOQUIA AND COMMUNICATIONS IN PHYSICS 48(1), JAN-FEB (2025). https://doi.org/10.1393/ncc/i2025-25037-xNeck emissions and the isospin degree of freedom

. Nucl. Phys. A 685, 296-311 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(01)00548-6Neck dynamics

. Eur. Phys. J. A 30, 65-70 (2006).. https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2006-10106-9Symmetry energy effect on emissions of light particles in coincidence with fast fission

. Phys. Lett. B 811,Transport model studies on the fast fission of the target-like fragments in heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 797,Intermediate-mass fragment decay of the neck zone formed in peripheral 209Bi + 136Xe collisions at Elab/A=28 MeV

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 2920-2923 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.75.2920Isospin dependence of intermediate mass fragment production in heavy-ion collisions at E/A=55 MeV

. Phys. Rev. C 54, 1710-1719 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.54.1710Fragment emission from the mass-symmetric reactions 58Fe,58Ni+58Fe,58Ni at Ebeam=30MeV/nucleon

. Phys. Rev. C 57, 1803-1811 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.57.1803Comparison of mid-velocity fragment formation with projectile-like decay

. Phys. Rev. C 71,Clustered and neutron-rich low density ’neck’ region produced in heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 55, 2109-2111 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.55.2109Dependence of projectile fragmentation on target N/Z

. Phys. Rev. C 59, 2567-2573 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.59.2567Correlation between the fragmentation modes and light charged particles emission in heavy ion collisions

. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 58,Effects of isospin dynamics on neck fragmentation in isotopic nuclear reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 94,Detailed characterization of neutron-proton equilibration in dynamically deformed nuclear systems

. Phys. Rev. C 95,Reexamining the isospin-relaxation time in intermediate-energy heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 98,Light charged clusters emitted in 32 MeV/nucleon 136,124Xe+124,112Sn reactions: Chemical equilibrium and production of 3He and 6He

. Phys. Rev. C 97,Neutron-proton equilibration in 35 MeV/ u collisions of 64,70 Zn + 64,70 Zn and 64 Zn, 64 Ni + 64 Zn, 64 Ni quantified using triplicate probes

. Phys. Rev. C 98,Experimental study of isospin transport with 40,48Ca+40,48Ca reactions at 35 MeV/nucleon

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Experimental effects on dynamics and thermodynamics in nuclear reactions on the symmetry energy as seen by the CHIMERA 4π detector

. Eur. Phys. J. A 50, 32 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2014-14032-yIsospin effects in nuclear fragmentation

. Nucl. Phys. A 703, 603-632 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(01)01671-2Neck fragmentation reaction mechanism

. Nucl. Phys. A 730, 329-354 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.10.022Isospin transport at Fermi energies

. Phys. Rev. C 72,Theoretical predictions of experimental observables sensitive to the symmetry energy

Eur. Phys. J. A 50, 30 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2014-14030-1Collision dynamics at medium and relativistic energies

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 113,Light cluster production in intermediate-energy heavy ion collisions induced by neutron rich nuclei

, Nucl. Phys. A 729, 809-834 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.09.0103H/3He ratio as a probe of the nuclear symmetry energy at sub-saturation densities

, Eur. Phys. J. A 51, 37 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2015-15037-8Stopping and isospin equilibration in heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 595, 209-215 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2004.05.080Triton-He-3 relative and differential flows as probes of the nuclear symmetry energy at supra-saturation densities

. Phys. Rev. C 80,Phase transition in an isospin dependent lattice gas model

. Phys. Lett. B 447, 221-226 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0370-2693(99)00003-9Temperature and free-nucleon densities of nuclear matter exploding into light clusters in heavy-ion collisions

. Nuovo Cim. A 89, 1-28 (1985). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02773614Isospin fractionation in nuclear multifragmentation

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 716-719 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.716Neutron and proton transverse emission ratio measurements and the density dependence of the asymmetry term of the nuclear equation of state

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97,Production of pions and light fragments at large angles in high-energy nuclear collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 24, 971-1009 (1981). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.24.971Isospin dependence of isobaric ratio Y(3H) / Y(3He) and its possible statistical interpretation

. Phys. Lett. B 497, 1-7 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0370-2693(00)01318-6Isospin tracing: A Probe of nonequilibrium in central heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 1120-1123 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.1120Yields of triton and 3He produced by nuclei in reactions of stopped pion absorption

. Bull. Russ. Acad. Sci. Phys. 78, 1112-1116 (2014). https://doi.org/10.3103/S1062873814110100Evidence for collective expansion in light-particle emission following Au+Au collisions at 100, 150 and 250 A.MeV

. Nucl. Phys. A 586, 755-776 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(95)00042-YA possible scenario for the time dependence of the multifragmentation process in Xe+Sn collisions: an explanation of the 3He puzzle. No. DAPNIA-SPHN-97-024. SCAN-9709121

, (1997).Isospin observables from fragment energy spectra

. Phys. Rev. C 86,Radial flow in Au + Au collisions at E = 0.25-A/GeV - 1.15-A/GeV

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 2662-2665 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.75.2662Critical phenomena in nuclear fragmentation

. Rivista del Nuovo Cimento 23, 1-101, (2000). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03548882What is the physics behind the 3He - 4He anomaly?

Eur. Phys. J. A 7, 101-106 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1007/s100500050016Intermediate mass fragments and isospin dependence in 124Sn, 124Xe + 124Sn, 112Sn reactions at 28-MeV/nucleon

. Phys. Rev. C 68,Isospin transport phenomena for the systems 80Kr+40,48Ca at 35 MeV/nucleon

. Phys. Rev. C 103,Systematics of central heavy ion collisions in the 1A GeV regime

. Nucl. Phys. A 848, 366-427 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2010.09.008A Compact Spectrometer for Heavy Ion Experiments in the Fermi energy regime

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 1011,CSHINE for studies of HBT correlation in Heavy Ion Reactions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 4 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-020-00842-2RIBLL, the radioactive ion beam line in Lanzhou

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 503, 496-503 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(03)01005-2The heavy ion cooler-storage-ring project (HIRFL-CSR) at Lanzhou

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 488, 11-25 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(02)00475-8Track recognition for the ΔE-E telescopes with silicon strip detectors

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 1029,Reconstruction of fission events in heavy ion reactions with the compact spectrometer for heavy ion experiment

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 40 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01024-yDevelopment of Parallel Plate Avalanche Counter for heavy ion collision in radioactive ion beam

. Nucl. Eng. Tech. 52, 575-580 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.net.2019.08.020An FPGA-based trigger system for CSHINE

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 162 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01149-0Progress of quantum molecular dynamics model and its applications in heavy ion collisions

. Front. Phys. (Beijing) 15, 54301 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11467-020-0961-9Systematics of complex fragment emission in niobium-induced reactions

. Nucl. Phys. A 483, 371-405 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(88)90542-8Emission of unstable clusters from hot Yb compound nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 63,QMD versus BUU/VUU: Same results from different theories

, Phys. Lett. B 224, 34-39 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(89)91045-9’Quantum’ molecular dynamics: A dynamical microscopic n body approach to investigate fragment formation and the nuclear equation of state in heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rept. 202, 233-360 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-1573(91)90094-3Production of high-energy neutron beam from deuteron breakup

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 92 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01075-1Orientation dichroism effect of proton scattering on deformed nuclei

. Chin. Phys. C 44,New probe to study the symmetry energy at low nuclear density with the deuteron breakup reaction

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Density slope of the nuclear symmetry energy from the neutron skin thickness of heavy nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 82,Effect of isospin dependent cluster recognition on the observables in heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 85,Measurement of fission time scale and excitation energy at scission for 25 MeV/u 40Ar+209Bi fission reaction

. Chinese Physics C 23, 946-953 (1999).Final state interactions in the production of hydrogen and helium isotopes by relativistic heavy ions on uranium

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 37, 667-670 (1976). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.37.667Central collisions of Au on Au at 150, 250 and 400 MeV/nucleon

. Nucl. Phys. A 612, 493-556 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(96)00388-0Examining the cooling of hot nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 57, R462-R465 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.57.R462Break-up stage restoration in multifragmentation reactions

. Eur. Phys. J. A 32, 175-182 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2006-10381-4Simulations of collisions between nuclei at intermediate energy using the Boltzmann-Uehling-Uhlenbeck equation with neutron skin producing potentials

. Phys. Rev. C 50, R1272-R1275 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.50.R1272Isospin dynamics in fragmentation reactions at Fermi energies

. Phys. Lett. B 625, 33 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2005.08.044Reaction dynamics with exotic beams

. Phys. Rept. 410, 335-466 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2004.12.004Influence of transport variables on isospin transport ratios

. Phys. Rev. C 84,From multifragmentation to neck fragmentation: Mass, isospin, and velocity correlations

. Phys. Rev. C 85,Neutron-proton asymmetry of the midvelocity material in an intermediate-energy heavy ion collision

. Phys. Rev. C 62,Distinctive features of Coulomb-related emissions in peripheral heavy ion collisions at Fermi energies

. Phys. Rev. C 76,New “3D calorimetry” of hot nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 98,Onset of midvelocity emissions in symmetric heavy ion reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 61,Intermediate mass fragment emission pattern in peripheral heavy-ion collisions at Fermi energies

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88,Neutron to proton ratios of quasiprojectile and midrapidity emission in the 64Zn + 64Zn reaction at 45-MeV/nucleon

. Phys. Rev. C 74,Centrality dependence of isospin effect signatures in 124Sn + 64Ni and 112Sn + 58Ni reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 77,Transverse collective flow and midrapidity emission of isotopically identified light charged particles

. Phys. Rev. C 83,Isospin compositions of correlated sources in the Fermi energy domain

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Probing high-momentum component in nucleon momentum distribution by neutron-proton bremsstrahlung γ-rays in heavy ion reactions

. Phys. Lett. B 850,Kinetic approach of light-nuclei production in intermediate-energy heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Light particle emission from the fissioning nuclei Ba-126, Pt-188 and 110-266, 110-272, 110-278: Theoretical predictions and experimental results

. Nucl. Phys. A 679, 25-53 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(00)00327-4Chun-Wang Ma and Hong-Wei Wang are editorial board members for Nuclear Science and Techniques and were not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.