Introduction

Electron-ion collisions present an unparalleled opportunity for investigating the internal structures of nucleons and nuclei [1], particularly the distribution of gluons across different momentum scales. Upcoming facilities, including the Electron-Ion Collider (EIC) [2] in the United States and the Electron-Ion Collider in China (EicC) [3], are specifically designed to probe these structures over a broad range of photon virtuality (Q2) and Bjorken-x, thereby enabling the study of phenomena such as nuclear shadowing and gluon saturation. The deployment of high-energy electron beams in interactions with protons and heavy ions facilitate precise measurements of the spatial and momentum distributions of gluons within the target [4], which is crucial for advancing our understanding of quantum chromodynamics (QCD) in dense nuclear environments.

Exclusive photoproduction is a key process for probing the gluon distribution within nuclei. In this process, a virtual photon emitted by an electron coherently interacts with the target, producing a vector meson while leaving the target intact. This interaction serves as a direct probe of the gluon density, as the cross-section is sensitive to the gluon distribution within the target. Specifically, in coherent photoproduction, the virtual photon fluctuates into a quark-antiquark pair, which subsequently scatters elastically from the target through the exchange of a color-neutral object, typically a Pomeron, at high energies [5]. Such studies are essential in understanding phenomena such as gluon shadowing, where gluon densities in nuclei are suppressed compared with those in free protons, and in providing compelling evidence for gluon saturation and the formation of color glass condensates [6-9].

To gain insights into the spatial distribution and fluctuations of gluons, measurements of the differential cross section

The accurate determination of the t distribution also necessitates a comprehensive understanding of the transverse momentum distribution of the photons involved in photoproduction. As this transverse momentum distribution cannot be directly measured, it is typically approximated using the Equivalent Photon Approximation (EPA) [15], which inherently involves integration over the impact parameter. However, recent theoretical and experimental studies on photon-photon collisions in heavy ion collisions have demonstrated that the photon transverse momentum distribution is highly dependent on the collision impact parameter [16-21]. This dependence necessitates a detailed investigation of the parameter dependence of exclusive photoproduction processes. In both electron-ion collisions and ultra-peripheral heavy-ion collisions (UPCs), conventional methods, such as using charged-particle multiplicity to determine the impact parameter, are not feasible. Recent measurements by the STAR [18], ALICE [22, 23], and CMS [9, 19] experiments have successfully utilized neutron emission from the Coulomb excitation of nuclei to effectively control the “collision centrality” in UPCs. This progress motivates the adoption of a similar technique for regulating the impact parameter in electron-ion collisions specifically by tagging neutrons from Coulomb excitation to determine the interaction centrality, that is, the impact parameter.

Determining the probability of Coulomb dissociation (CD) as a function of the impact parameter in UPCs necessitates the calculation of the photon flux in spatial coordinates. In UPCs, the spatial distribution of the photon flux is typically computed using EPA, which assumes a straight-line trajectory for the ions involved. This assumption is valid when the motion of colliding ions is not significantly influenced by the electromagnetic field over the collision duration. However, in electron-ion collisions at an EIC, the photon flux induced by the electron cannot be described by the conventional EPA, as the straight-line approximation breaks down owing to the substantial deflection of the electron under the electromagnetic field of the heavy ion. Consequently, a precise derivation of the spatial distribution of the photon flux induced by the electron is essential to accurately calculate the CD probability as a function of the impact parameter in electron-ion collisions.

This study aims to address these challenges by extending the conventional EPA framework to incorporate the unique dynamics of electron-induced photon flux in electron-ion collisions. By developing a spatially dependent photon flux distribution, we aim to establish a more precise relationship between the transverse momentum distribution of photons and the impact parameters of the collisions. Within this refined framework, we propose to study the impact parameter manipulation in exclusive photoproduction processes in electron-ion collisions by tagging neutrons from Coulomb excitation. By achieving impact parameter control via neutron tagging, this study introduces a new methodology for probing the spatial and momentum structures of gluons in nuclei, thereby contributing to the experimental design and data analysis strategies for future electron-ion collision experiments.

Methodology

Kinematics of Electron-Proton/Nucleus Scattering

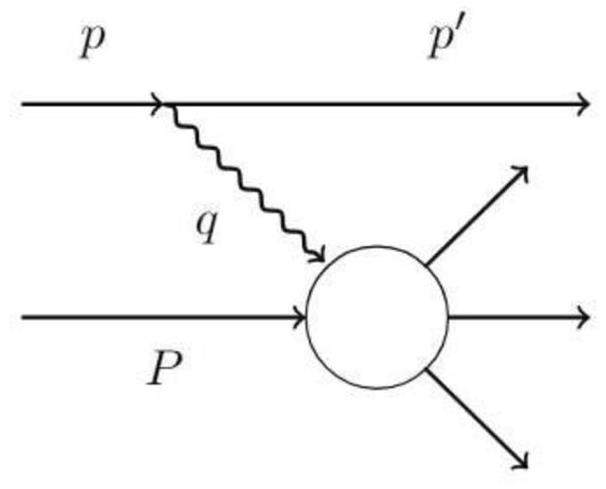

To derive the photon flux, we begin by analyzing the kinematics of lowest-order of electron-proton (e + p) scattering, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Although our primary interest lies in electron-nucleus (e + A) collisions, the photon flux generated by the electron is essentially the same in both e + p and e + A interactions. Therefore, to ensure both simplicity and generality in the derivation, we perform the analysis within the context of e + p-scattering.

Let the z-axis be the direction of motion of the incident electron. The four vector of the incident electron p and that of the scattering electron

Photon Flux Derivation

Considering the lowest order of QED, the cross-section for the process shown in Fig. 1 is given by [24]

For photoproduction in relativistic heavy-ion collisions, the photon flux is typically estimated using the conventional EPA, which was independently derived by Williams [25] and Weizsäcker [26] in the 1930s. In their derivation, they assumed that the charged particles moved along straight-line trajectories and obtained the spatial distribution of the electromagnetic field by solving the vector potential wave equation. The spatial distribution of the equivalent photon number was subsequently derived based on the relationship between the energy flux density and equivalent photon number. This approach provides an effective way to describe the photon flux distribution, which can be expressed as

Coulomb Dissociation in Electron-Ion Collisions

Analogous to the Coulomb excitation process in relativistic heavy-ion collisions, Coulomb excitation in electron-ion collisions can be factorized into two distinct components: the emission of virtual photons by electrons and the corresponding photon absorption cross-section of the nucleus. The virtual photons emitted by electrons can be estimated using the framework described in the previous subsection.

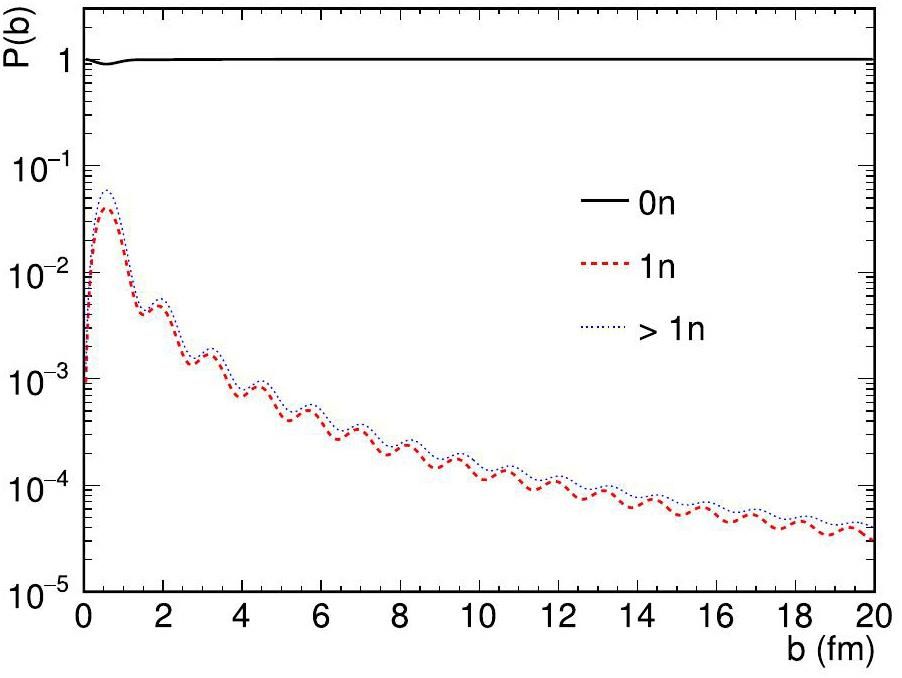

The lowest-order probability that a nucleus is excited to a state that subsequently emits at least one neutron (denoted as Xn) can be expressed as [27]

Notably, under specific conditions, such as very small impact parameters and extremely high beam energies, the value of mXn could exceed 1, implying that the excitation probability would lose its probabilistic interpretation. Although such conditions are improbable in current or near-future facilities, it is beneficial to address this scenario for the sake of completeness. To maintain a valid probabilistic interpretation,

Finally, the total probability of emission of i neutrons is given by

Vector Meson Photoproduction in Electron-Ion Collisions

The vector meson photoproduction in electron-ion collisions can be estimated in a manner similar to Coulomb excitation calculations. The primary difference lies in replacing the photon absorption cross section of the nucleus with the

Considering the impact of the photon’s virtuality on the photon-nucleon scattering cross-section, the equivalent vector meson flux is introduced as

The amplitude distribution for the vector meson photoproduction process is given by

Finally, the photoproduction cross section in conjunction with the Coulomb excitation of the nucleus can be estimated as follows:

RESULTS

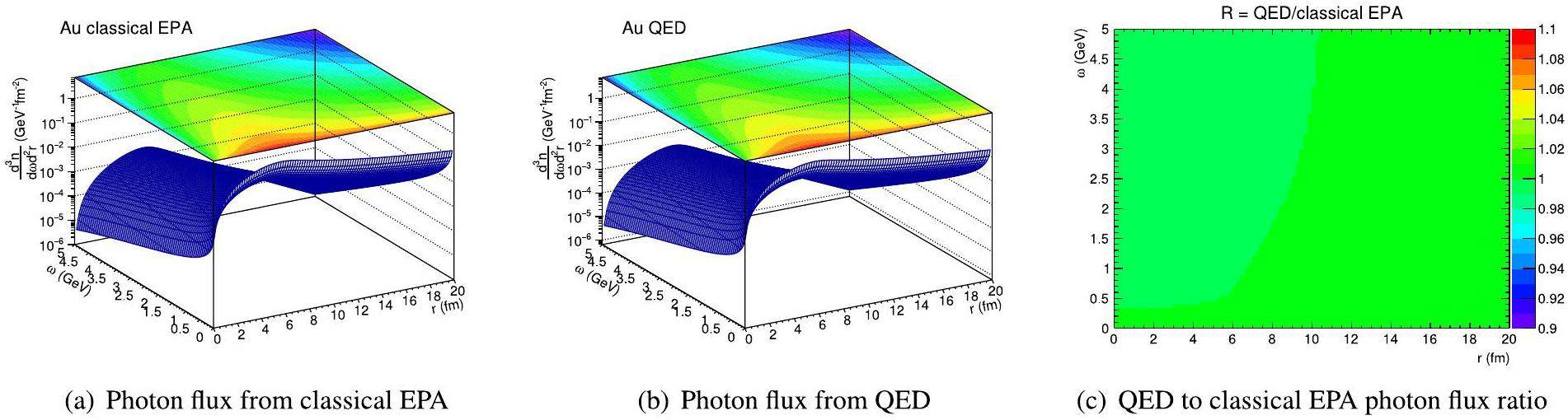

In ultraperipheral heavy-ion collisions, the photon flux is typically calculated using the classical EPA approach, as given by Eq. 27. This model assumes that the charged particles involved move along straight-line trajectories. However, concerns have been raised regarding the validity of this assumption, particularly at the energies probed at RHIC and LHC. To examine the applicability of the classical EPA model, we compared it with the QED approach, which does not rely on the straight-line trajectory assumption. Figure 2 presents the photon flux distribution induced by a Au nucleus with an energy of 100 GeV per nucleon, calculated using both the classical EPA and QED models, along with the ratio of the QED results to the classical EPA results. The figure indicates that both models predict a maximum photon flux at the radius of the Au nucleus, and a subsequent decrease as the photon energy ω increases. Furthermore, the ratio between the QED and classical EPA results remains close to unity, indicating that the classical EPA model provides an accurate approximation of the photon flux for UPCs and is effectively equivalent to the QED-derived expression under these assumptions.

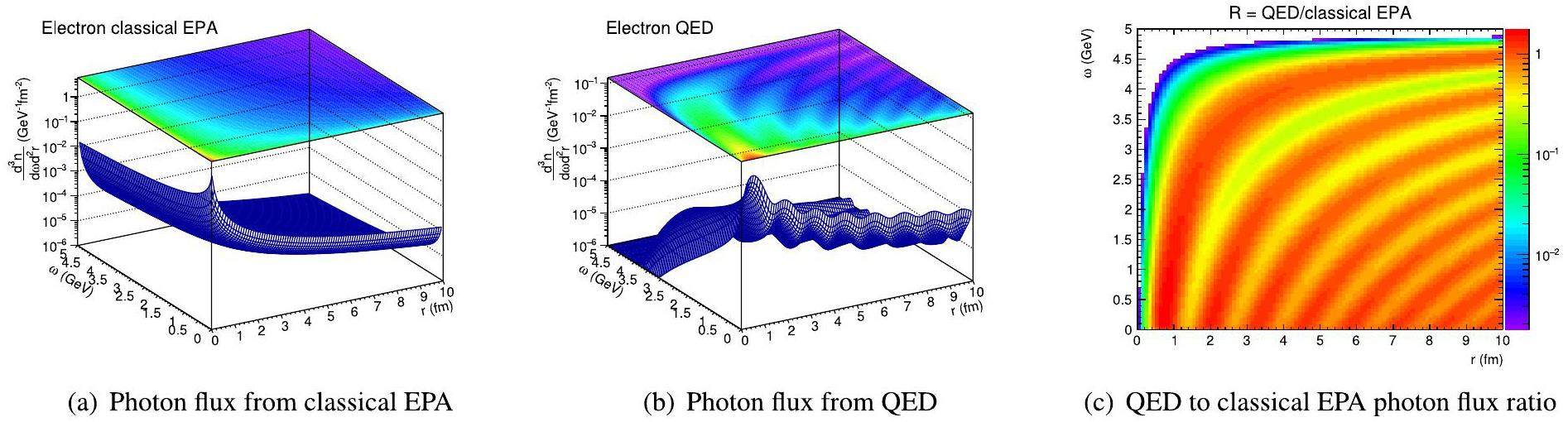

However, the use of Eq. 27 becomes problematic in the context of electron-ion collisions. This is primarily because the energy of an electron is significantly lower than that of a heavy ion, which renders the straight-line approximation invalid. Furthermore, direct application of Eq. 27 does not constrain the photon energy from exceeding the energy of the charged particle, which is physically incorrect. To illustrate this limitation, we compare the photon flux distributions calculated using the classical EPA and QED models for an electron with an energy of 5 GeV. Figure 3 presents the 2D photon flux distribution and the ratio of the QED to classical EPA results. The comparison clearly demonstrates a substantial difference between the two models, with the QED-derived flux showing distinct fluctuations and tending towards zero as the photon energy approaches the electron energy. This behavior underscores the inadequacy of the classical EPA model in describing the photon flux for electron-ion collisions.

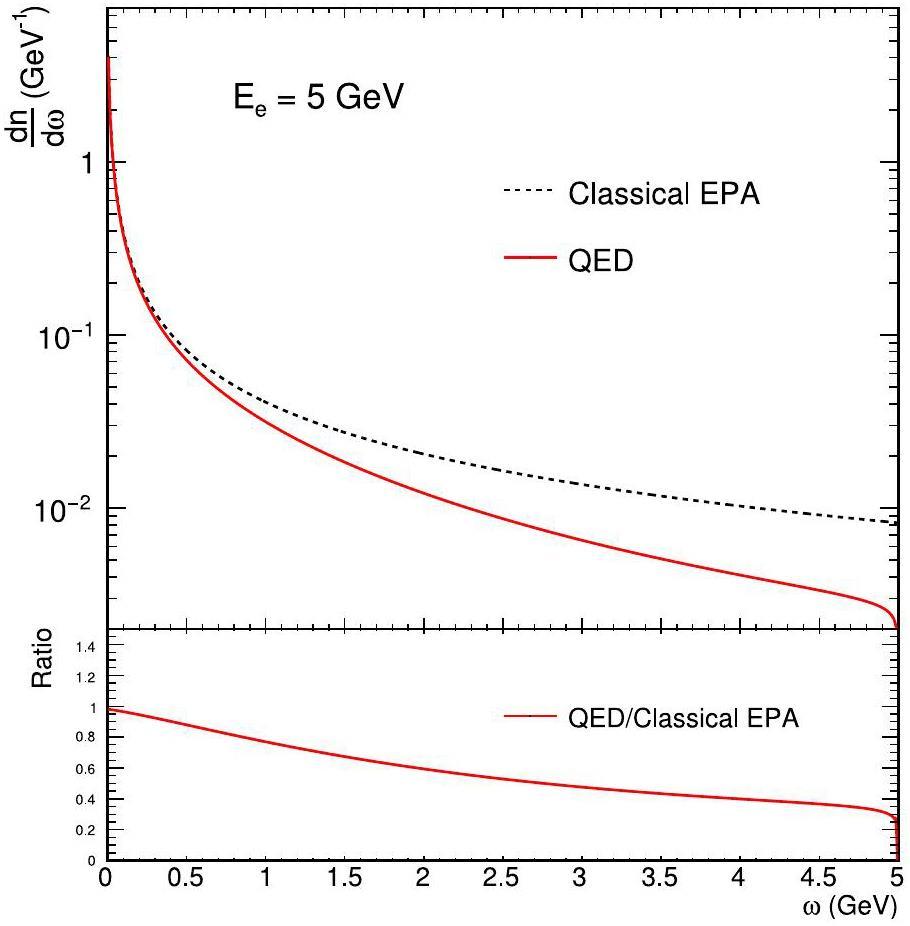

Figure 4 provides a further comparison of the photon energy distributions obtained using the classical EPA and QED models. The photon flux calculated using the QED model closely follows the classical EPA prediction at low photon energies but rapidly approaches zero as the photon energy approaches the total energy of the electron. In contrast, the photon flux calculated using the classical EPA model decreases smoothly without reaching zero. This discrepancy further underscores the limitations of the classical EPA model for electron-ion collisions and demonstrates that the photon flux distribution derived from the QED model is more suitable for accurately describing these processes. Consequently, the QED approach offers a more reliable framework for calculating the impact parameter dependence of photoproduction processes in electron-ion collisions.

The lowest-order QED-derived photon flux enables accurate evaluation of the Coulomb excitation of a nucleus during electron-ion collisions. As an illustrative example, we consider e + Au collisions at the EIC energies, specifically at 18 × 100 GeV per nucleon. The corresponding

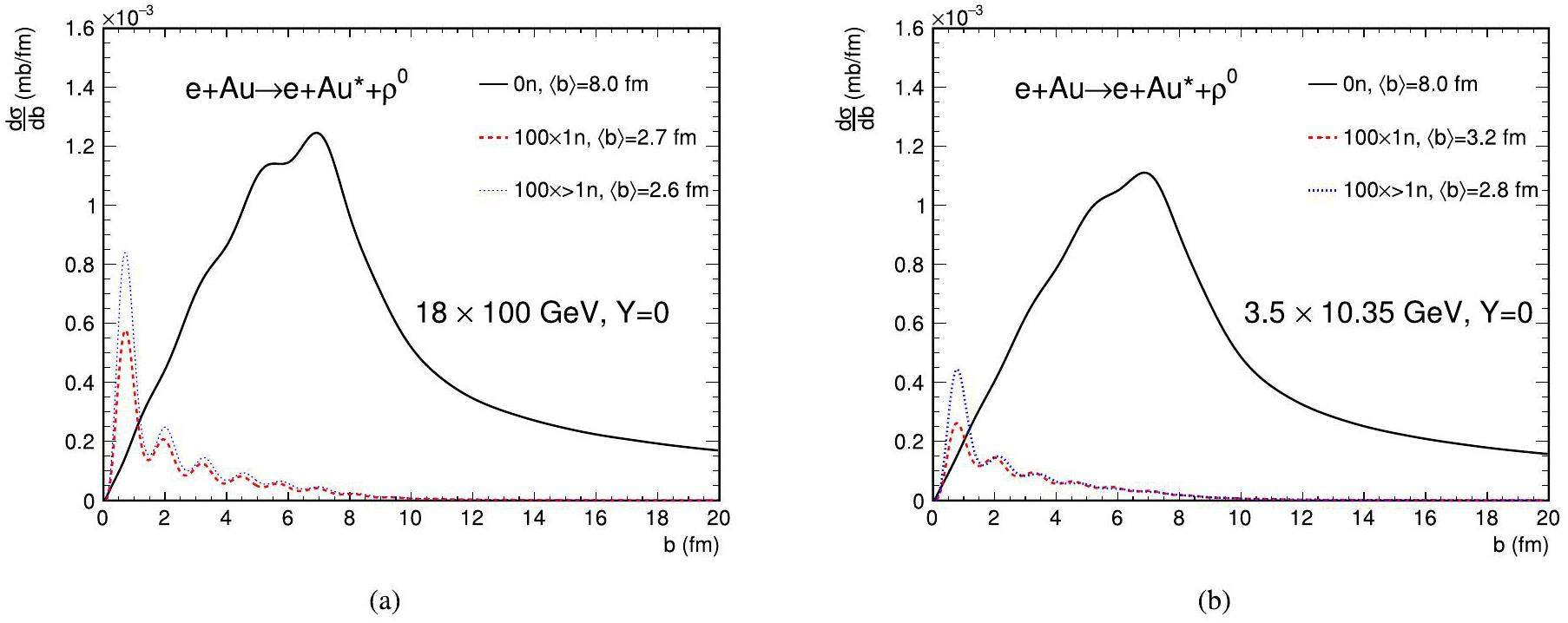

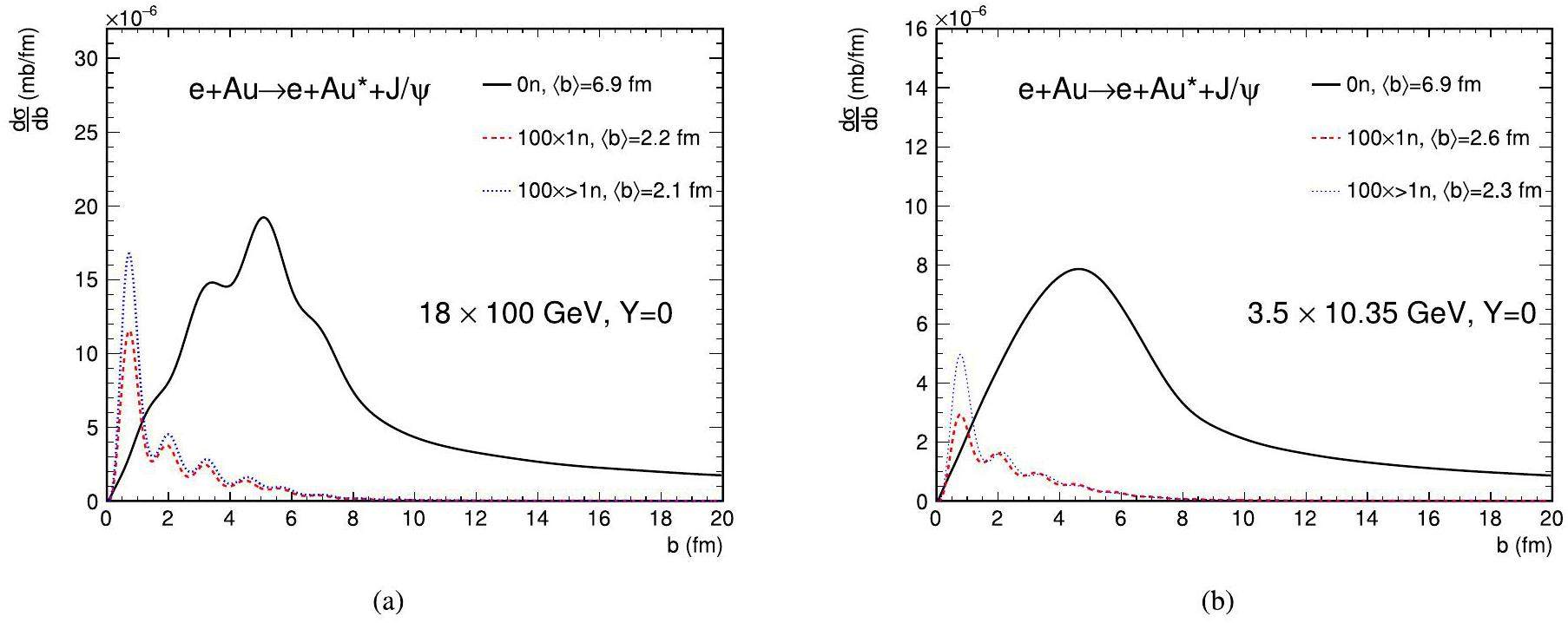

Furthermore, the different photoproduction processes, even those with the same neutron tagging, exhibit variations in impact parameter distributions. This is because the photon energies involved in different processes vary, thereby impacting the spatial distribution of photons relative to electrons. Unlike hadronic heavy-ion collisions, where centrality is defined by a fixed impact parameter range, the impact parameter determination in electron-ion collisions via neutron tagging depends on the specific photoproduction process under consideration. Therefore, this must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. To illustrate this, we present calculations for coherent ρ0 and J/ψ photoproduction accompanied by different neutron tagging at the EIC and EicC energies.

Figure 6 presents the

Figure 7 illustrates the

summary

We investigated the feasibility of employing neutron tagging, resulting from the Coulomb excitation of nuclei, as a precise method to ascertain the impact parameters of exclusive photoproduction events in electron-ion collisions. By developing an equivalent photon approximation for electrons, this study integrated a photon flux distribution in coordinate space, thereby validating the relationship between the distribution of the photon’s transverse momentum and the impact parameters of the collisions. The differential cross-section for the Coulomb excitation of nuclei was calculated by leveraging the spatial data of the photon flux. Our calculations indicate that the presence or absence of neutron excitation in the photoproduction process can markedly shift the distributions of impact parameters, thereby offering a reliable technique for controlling the impact parameter in electron-ion collision experiments. This study provides essential methodologies and insights for examining the dependence of exclusive photoproduction processes on impact parameters, yielding novel perspectives for the design of experiments and data analysis.

Lambda polarization at the Electron-ion collider in China

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 155 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01317-wElectron Ion Collider: The Next QCD Frontier: Understanding the glue that binds us all

. Eur. Phys. J. A 52, 268 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2016-16268-9Electron-ion collider in China

. Front. Phys. 16, 64701 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11467-021-1062-0The Color glass condensate and high-energy scattering in QCD

. in Quark-gluon plasma 4, 249 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812795533_0005On the dipole picture in the nonforward direction

. Acta Phys. Polon. B 34, 3051 (2003). arXiv:hep-ph/0301192.Probes of the small x gluon via exclusive J/ψ and Υ production at HERA and the LHC

. JHEP 11, 085 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP11(2013)085Exclusive photoproduction of a heavy vector meson in QCD

. Eur. Phys. J. C 34, 297 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s2004-01712-x [Erratum: Eur. Phys. J. C 75, 75 (2015)]Exclusive charmonium production at the electron-ion collider in China

. Eur. Phys. J. C 84, 684 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-024-13033-9Probing Small Bjorken-x Nuclear Gluonic Structure via Coherent J/ψ Photoproduction in Ultraperipheral Pb-Pb Collisions at sNN=5.02 TeV

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131,Exclusive diffractive processes in electron-ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 87,Imaging the nucleus with high-energy photons

. Nat. Rev. Phys. 1, 662 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42254-019-0107-6Coherent diffractive photoproduction of ρ0 mesons on gold nuclei at 200 GeV/nucleon-pair at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider

. Phys. Rev. C 96,First measurement of the |t|-dependence of coherent J/ψ photonuclear production

. Phys. Lett. B 817,Tomography of ultrarelativistic nuclei with polarized photon-gluon collisions

. Sci. Adv. 9, 1 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abq3903On the Theory of the impact between atoms and electrically charged particles

. Z. Phys. 29, 315 (1924). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03184853Initial transverse-momentum broadening of Breit-Wheeler process in relativistic heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 800,Centrality dependence of dilepton production via γγ processes from Wigner distributions of photons in nuclei

. Phys. Lett. B 814,Measurement of e+e− Momentum and Angular Distributions from Linearly Polarized Photon Collisions

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127,Observation of Forward Neutron Multiplicity Dependence of Dimuon Acoplanarity in Ultraperipheral Pb-Pb Collisions at sNN=5.02 TeV

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127,Properties of the QCD Matter – An Experimental Review of Selected Results from RHIC BES Program

. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2407.02935Electromagnetic fields in ultra-peripheral relativistic heavy-ion collisions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 20 (2024) https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01374-9Measurement of the impact-parameter dependent azimuthal anisotropy in coherent ρ0 photoproduction in Pb-Pb collisions at sNN=5.02 TeV

. Phys. Lett. B 858,Energy dependence of coherent photonuclear production of J/ψ mesons in ultra-peripheral Pb-Pb collisions at sNN=5.02 TeV

. JHEP 10, 119 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP10(2023)119The Two photon particle production mechanism

. Physical problems. Applications. Equivalent photon approximation. Phys. Rept. 15, 181 (1975). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-1573(75)90009-5Sowie eine im Erscheinen begrifene Fortsetzung dieser Arbeit

. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series A 139, 163 (1933).Radiation emitted in collisions of very fast electrons

. Z. Phys. 88, 612 (1934). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01333110Heavy ion partial beam lifetimes due to Coulomb induced processes

. Phys. Rev. E 54, 4233 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.54.4233Photoneutron cross sections of 208Pb and 197Au

. Nucl. Phys. A 159, 561 (1970). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(70)90727-XMeasurements of the Total Photonuclear Cross-sections From 30-MeV to 140-MeV for SN, Ce, Ta, Pb and U Nuclei

. Nucl. Phys. A 367, 237 (1981). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(81)90516-9Total photonuclear absorption cross-section for Pb and for heavy nuclei in the delta resonance region

. Nucl. Phys. A 431, 573 (1984). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(84)90269-0Total Hadronic Photoabsorption Cross-Sections on Hydrogen and Complex Nuclei from 4-GeV to 18-GeV

. Phys. Rev. D 7, 1362 (1973). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.7.1362The total photon deuteron hadronic cross-section in the energy range 0.265-4.215 GeV

. Nucl. Phys. B 41, 445 (1972). https://doi.org/10.1016/0550-3213(72)90403-8Mutual heavy ion dissociation in peripheral collisions at ultrarelativistic energies

. Phys. Rev. C 64,Particle emission following Coulomb excitation in ultrarelativistic heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 60,A generator of forward neutrons for ultra-peripheral collisions: nOOn

. Comput. Phys. Commun. 253,Glauber modeling in high energy nuclear collisions

. Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 57, 205 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.nucl.57.090506.123020The Hadronic Properties of the Photon in High-Energy Interactions

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 50, 261 (1978). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.50.261. Note: Erratum: Rev. Mod. Phys. 51, 407 (1979)Elastic electroproduction of rho mesons at HERA

. Eur. Phys. J. C 13, 371 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1007/s100520050703Diffractive Electroproduction of ρ and ϕ Mesons at HERA

. JHEP 05, 032 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP05(2010)032Determination of electron-nucleus collision geometry with forward neutrons

. Eur. Phys. J. A 50, 189 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2014-14189-3The authors declare that they have no competing interests.