Introduction

X-ray free-electron lasers (XFELs) produce ultra-intense and ultra-short coherent X-ray pulses [1-3]. Femtosecond XFEL pulses can be used to record diffraction patterns before a sample is destroyed, known as ‘diffraction before destruction’ [4, 5]. This method overcomes the limitations of X-ray radiation damage in biological samples [6]. By recording thousands of diffraction patterns of identical noncrystalline single particles or macromolecules, a three-dimensional (3D) structure can be reconstructed at atomic or near-atomic resolution; this is known as single-particle imaging (SPI). In recent years, SPI has developed rapidly as an initial motivation for XFELs. For SPI experiments, freezing or crystallization is unnecessary. It mainly includes the following steps. First, identical samples are transferred to the XFEL beam, and a series of 2D diffraction patterns are obtained from randomly oriented isolated particles. Thousands of 2D diffraction patterns are then oriented and assembled into 3D diffraction patterns. Finally, high-resolution 3D structures of the samples are obtained via phase recovery [7]. SPI experiments with XFELs have been demonstrated on various samples. The sizes of the particles of interest have transitioned from larger viruses to smaller proteins, such as the 450-nm Mimivirus [8], 220-nm Melbourne virus [9], 100-nm carboxysomes [10], 70-nm rice-dwarf virus [11], and 70-nm PR772 bacteriophages [12]. Recently, single-shot diffraction patterns of noncrystalline protein complexes with a diameter of only 14 nm were recorded [13].

Although SPI has been demonstrated in several experiments, and resolutions better than 10 nm have been achieved [14], a number of limitations to achieving atomic resolution still remain. Currently, the main limitation is the collection of a substantial number of high-quality diffraction patterns within a short time [15, 16], which is closely related to sample-delivery systems. Because any target material is destroyed or damaged by an ultra-intense X-ray pulse [17, 18], new particles must be updated for every pulse in real time. Various types of sample-delivery systems have been applied to single-shot imaging, including fixed targets [19, 20], liquid-jet injectors [21], and aerosol injectors [10]. Among these, aerosol injectors are widely used owing to their low background scattering [22]. The main component of an aerosol injector is an aerodynamic lens (ADL), which focuses and accelerates individual particles into the X-ray interaction region. Currently, the most widely used aerosol injector is the ‘Uppsala injector,’ which is equipped with an ADL (AFL100) designed to focus particles ranging from 0.1 to 3 μm [10]. In this process, atomization techniques are used to transfer the sample particles from the solution into the gas phase. A gas dynamic virtual nozzle (GDVN) is a commonly used atomization device that employs helium or nitrogen as the carrier gas. Commercial electrospray is also used to atomize smaller particles to reduce contamination from nonvolatile components, employing nitrogen (approximately 90% in volume fraction) as the carrier gas [22]. Recently, helium electrospray ionization was proposed to reduce the background signal from heavy gas molecules [23]. Helium was introduced to reduce nitrogen and carbon-dioxide consumption in the original ESI. The Uppsala injector was successfully applied in several experiments [8, 10, 13, 24]. Using the current aerosol injector, a hit rate (the fraction of X-ray pulses that hit at least one particle) of up to 79% can be achieved when the X-ray focus is approximately a few micrometers [10]. However, when attempting to obtain diffraction signals from samples with high scattering angles or smaller sizes (such as proteins), the required X-ray focal-spot size is of the order of 100 nm. In such cases, the hit rate is typically below 0.05%. Recent computational studies have estimated that protein reconstruction at a resolution of 0.3 nm requires approximately 105–106 diffraction patterns [25]. A low hit rate results in long measurement times and excessive sample consumption. Additionally, background-scattering signals from gas molecules emitted by ADL may overpower the sample signal, particularly at high diffraction angles, thereby limiting the achievable resolution for biological samples.

The emergence of superconducting MHz repetition-rate hard-XFEL facilities, such as European-XFEL, SHINE, and LCLS-II, provides new opportunities to record sufficient diffraction patterns with limited experimental beamtime [26-29]. The repetition rate of the X-ray pulses in the new facilities is approximately 10,000 times that of conventional XFEL facilities [30-33]. With the aid of improved aerosol injectors, thousands of high-quality diffraction patterns may be collected per second [34]. Therefore, improving and developing efficient aerosol injectors are crucial for SPI experiments. To increase the hit rate and collect more diffraction patterns with high-repetition XFELs, the particle-beam diameter must be further reduced to increase the sample density. Furthermore, the carrier gas must be reduced or the focal position of the particle beam must be extended to minimize the background-scattering noise and improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

The concept of ADL was first proposed by Liu et al. in 1995 [35], and was primarily used in mass spectrometry [36]. Typically, the ADL comprises a relaxation chamber, a multistage lens stack, and an accelerating nozzle [37, 38]. After decelerating and returning to the horizontal laminar flow inside the relaxation chamber, the aerosol passes through a series of coaxial circular orifices (i.e., lenses). Within the lens stack, particles tend to accumulate near the central axis owing to the combined effects of the drag force and inertia. Subsequently, an accelerating nozzle is employed to regulate the operating pressure within the ADL. Simultaneously, it further focuses the particle beam and delivers the particles into the vacuum. In the ADL, particle focusing is influenced by various interrelated parameters, including the Stokes number (St), Reynolds number (Re), Mach number(Ma), tube-constriction ratio (β), initial radial position of the particles (r), and ratio of lens thickness to orifice diameter (Lf/df) [35, 39, 40]. Among them, St is the key factor affecting the focusing performance. Ideally, the trajectory of the particles after passing through a lens coincides with the lens axis. The corresponding Stokes number is known as the optimum Stokes number (Sto). However, as St is affected by the various parameters mentioned above, no clear functional relationship exists between St and its influencing parameters [35]. Therefore, Sto does not have a fixed value under different conditions, which makes the design of ADLs challenging. The following studies demonstrate the design process of ADLs. Wang et al. emphasized that Sto is a function of Re and Ma [39]. They developed an aerodynamic lens calculator (ALC) to facilitate the design of ADLs. The ALC is an efficient tool that has been used in the fields of mass spectrometry, sample delivery, and aerosol printing [41, 42]; however, it cannot meet the high requirements of SPI [43]. Lee et al. established a universal correlation between Sto and a combination of parameters [44]. Given the initial dimensional parameters of the ADL, the diameter of each lens was optimized through multiple iterations of numerical simulation. A research group in Hamburg employed numerical simulations to design an ADL for focusing 50 nm gold particles [43]. The optimization procedure was performed iteratively from the exit to the entrance of the ADL, with different combinations of geometric values (i.e., lens-aperture radius and inner-tube radius) tested to ensure that the particle beam fulfilled the set conditions. Moreover, this group published related work on optimizing ADL injectors and employed injectors in various successful SPI experiments [13, 45-47].

In this study, we established a functional relationship between Sto and its influencing parameters through theoretical analyses and numerical simulations. Based on this relationship, we propose an efficient and simple method for designing the ADL. We then design an ADL for focusing particles ranging from 30 to 500 nm based on the requirements of SPI with this improved method. Both the simulated and experimental results showed that the newly designed ADL effectively focuses particles into a narrow beam at a low nitrogen flow rate. The new ADL performs better on particles smaller than 100 nm than the current aerosol injector. This study optimizes the performance of aerosol injectors, which will contribute to achieving the high-resolution imaging of single particles using XFELs in the future.

Methods

Theoretical analysis

In the ADL, particles are focused through the contraction and expansion of the flow field, causing them to deviate from gas streamlines owing to their inertia. The focusing effect is determined primarily by the Stokes number (St), which characterizes the degree of deviation. St is a dimensionless number in fluid mechanics defined as the ratio of the stopping distance of the particles to the characteristic size of an obstacle:

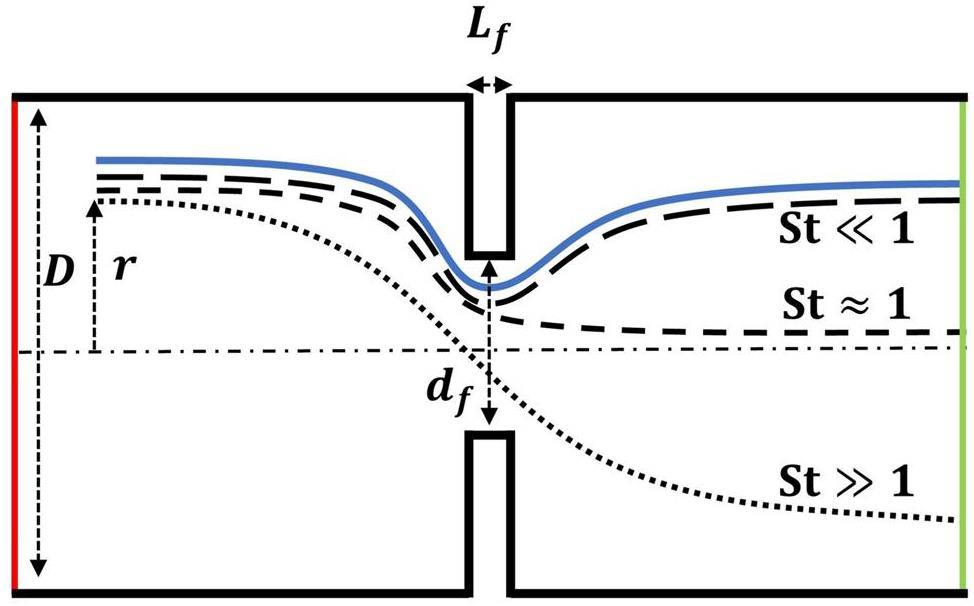

Figure 1 shows the focusing principle of a single lens in the ADL. The single lens comprises a tube with a diameter D and an orifice plate with a diameter df. The aerosol enters the lens from the left side in the laminar-flow state. After passing through the lens, the particles at a specific initial radial position (r) deviate from the gas streamline owing to inertial effects. When

The particle diameter in SPI typically ranges from a few nanometers to a few micrometers, whereas the mean free path of gas molecules ranges from tens of micrometers to hundreds of micrometers in an ADL. According to the definition of the Knudsen number of particles (Knp, which is the ratio of the mean free path to the particle radius), Knp is considerably greater than one. Therefore, the Stokes number is defined using the Epstein flow model in the free molecular-flow regime [48]:

Sto is affected by different geometric parameters and operating conditions [35, 39, 40], including the tube-constriction ratio (β, defined as df/D), ratio of the lens thickness to the lens orifice diameter (Lf/df), Reynolds number (Re), Mach number (Ma), gas-mass flowrate, and initial radial position of the particles (r). To simplify the design method of the ADL, we first conduct a mathematical analysis of the main parameters that affect Sto based on previous research and make reasonable assumptions. Subsequently, we establish a functional relationship between Sto and its influencing parameters through numerical simulations.

For a specific carrier gas, the relationship between Sto and its influencing parameters can be expressed as:

Equation 5 is then substituted into the definition of the Reynolds number, and Re based on the orifice diameter is

Equation 5 is substituted into the definition of the Mach number, and Ma based on the orifice diameter is

Based on Eq. 10, P1 is mainly determined by

Numerical simulation

Owing to the large number of influencing parameters, an effective ADL design is difficult to achieve based solely on experimental experience. The design process of an ADL typically requires both iterative optimization and experimental measurements. Numerical simulations allow for the design and rapid iteration of the ADL on computers. Various internal-flow parameters of the ADL can be easily obtained through simulations. The computational fluid dynamics software FLUENT is adopted to calculate the flow field and predict the motion of the particles. The volume fraction of the particles is much smaller than that of the fluid in the ADL. We assume that the particles do not affect the flow field and that no interaction force exists between the particles. In addition, the particles are assumed to be spherical; thus, the lift force is neglected. We first calculate the flow field by solving the steady-state Navier–Stokes equations. The particles are then introduced into the flow field to obtain the trajectories and velocities using the Lagrangian method.

The geometry of the ADL is axisymmetric; thus, a 2D axisymmetric model is used. The Navier–Stokes equations are solved using the finite-volume method. The SIMPLEC algorithm is selected as the pressure–velocity coupling method. The flow properties are typically characterized by three dimensionless numbers: the Reynolds, Mach, and Knudsen (Kn) numbers. Because Re is generally less than 100 in the ADL, the viscous model is set as laminar. The flow inside the ADL is limited to a subsonic condition. Because Ma > 0.3 at the accelerating nozzle, the flow is assumed to be compressible. The mean free path of the gas in an ADL is several tens of micrometers, whereas the diameter of the lens is approximately 1 mm; hence, Kn < 0.1. The flow is assumed to be in the continuum- or slip-flow region. In the vacuum chamber, the gas is in the free molecular-flow region, and the particles are hardly affected by the gas. We assume that the simulation can still predict the particle motion after they leave the ADL.

A quadrilateral mesh is used for the simulations. The cell size near the orifices ranges from 4 to 10 μm, and is 100 μm in the spacers. The numbers of mesh cells for a single lens and the ADL are approximately 70,000 and 370,000, respectively, with a growth rate of 1.1 and an average element quality greater than 0.95. The boundary conditions are defined in Sect. 3. For all simulations, when the continuity residual is less than 1 × 10-10 and the relative error of the inlet and outlet mass flowrate is less than 0.01%, the calculation is considered convergent.

A discrete phase model is used to introduce particles into the calculated flow field, and user-defined functions are used to describe the forces applied to the particles. In the ADL, particles are mainly subjected to drag and Brownian forces, as follows:

Because the mean free path is much larger than the particle radius (i.e.,

The focusing effect of the ADL is determined by a combination of aerodynamic focusing and diffusion broadening caused by Brownian motion [39]. When studying the parameters that influence Sto in a single lens, only the drag force is considered. When evaluating the performance of the ADL, both the drag and Brownian forces are considered to approach a more realistic state. The particle trajectories are calculated from the injection location until they reach the exit or wall.

Optimization of the design method

For a single lens, when the mass flowrate and downstream pressure are given, the optimal upstream gas pressure (Pfocusing) and df required to focus the particles can be calculated using Eq. 17. The pressure decrease of a gas passing through a single lens can be calculated using Eq. 10. By repeating this process, all the diameters and pressures of the multistage lens stack can be obtained sequentially.

Based on the above analysis, the design process of ADL becomes simple and efficient when a functional relationship (or two) of Sto is given. The optimized method is as follows.

First, the particle diameter of each lens is set based on the particle-size range. When large particles pass through the front lens and are focused near the axis, they are less likely to diverge when passing through the rear lens. Therefore, the front lenses are used to focus the large particles, whereas the rear lenses are used to focus the small particles.

Second, the initial parameters are set and the diameter and pressure decrease of each lens are calculated using Eq. 17 and Eq. 10. The initial parameters are the pressure before the accelerating nozzle, tube diameter (D), and gas mass flowrate. The relationship between Sto and df for specific

Third, the accelerating nozzle is designed based on the pressure before it. Because of the significant pressure decrease before and after passing through the acceleration nozzle, the gas exceeds the sonic speed [54, 55]. The nozzle diameter (dn) is calculated as follows [56]:

Finally, the spacer lengths (L) are calculated by using the overall simulations of the ADL. After passing through the lens, the flow forms a recirculation zone. Subsequently, the flow returns to the horizontal laminar-flow state after a particular distance (redevelopment length). Before entering the next lens, the flow starts to curve toward the centerline, resulting in the approach length. To provide sufficient space for periodic contraction and expansion, spacers are used to separate lenses that have lengths greater than the sum of the redevelopment and approach lengths. By presetting a sufficiently long length for each spacer, the redevelopment and approach lengths can be calculated through an overall simulation of the ADL. The spacer lengths for the final ADL can be determined based on the simulation results. Note that small changes in L have little effect on the pressure inside the ADL, because the flow resistance is mainly determined by the lens orifice. In addition to the simulation method, L can be estimated using empirical formulas [39].

Experimental setup

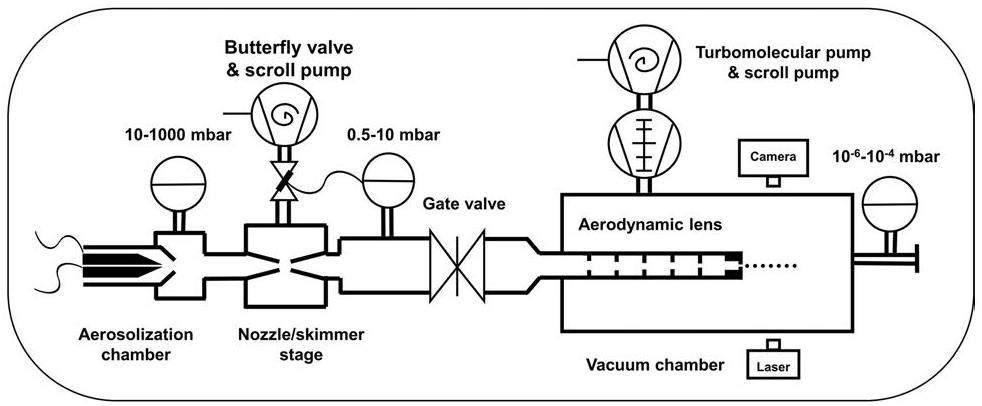

An aerosol sample-delivery system was established to validate the simulation and test the new ADL, as shown in Fig. 2. It consists of an atomization device, a nozzle/skimmer stage, an aerodynamic lens, and other auxiliary devices. Briefly, a solution containing the particles of interest was atomized using the GDVN [21] in the aerosolization chamber. The particles were then introduced into the ADL through a nozzle/skimmer stage placed 1–2 mm apart. The excess carrier gas was extracted to control the pressure in the relaxation chamber. The particles were focused by the ADL and a particle beam was generated in the downstream vacuum chamber (10-6–10-3 mbar). The particle beam was illuminated by a continuous laser (650 nm, 50 mW), and the scattered light was collected using an ultra-long working-distance objective lens (ULWZ-200M, OptoSigma, France; N.A. 0.014–0.08) and a complementary metal-oxide semiconductor camera (CS165MU1/M, Thorlabs, USA). The particle-beam diameter (full width at half maximum) in the experiment was determined by measuring the projection of the beam along the laser-propagation axis. Downstream of the accelerating nozzle, the point with the smallest beam width was defined as the focal point.

Results and discussion

Simulation results of the single lens

Single-lens simulations with different orifice diameters are performed to verify the theoretical analysis described in Sect. 2. As shown in Fig. 1, the red and green lines represent the inlet and outlet of the computational domain of the single lens, respectively. The solid black line on the exterior represents a wall. Mass-flow conservation is used as the inlet condition, and pressure is used as the outlet condition, according to the specific conditions shown in Fig. 3 and Fig. 4. A polystyrene (PS) sphere with a density of 1050 kg/m3 is injected from an initial position and experienced only a drag force. To avoid the impact of a non-fully developed flow at the entrance, the initial injection position is located 10 mm downstream of the lens inlet and

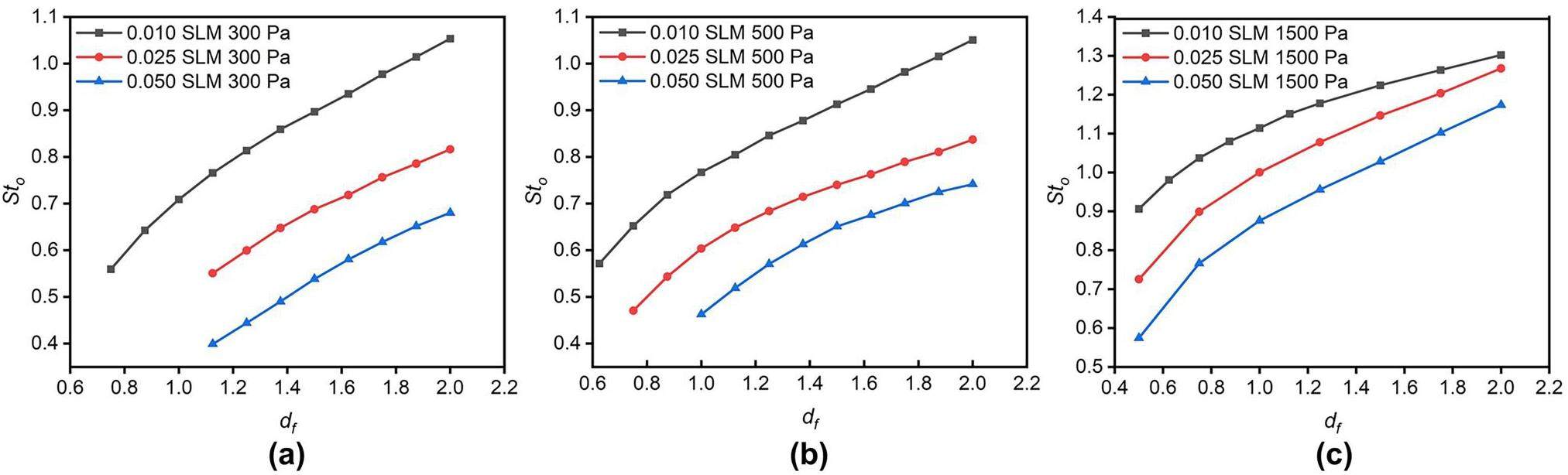

Figure 3 shows the relationship between Sto and df under the same downstream pressure but different mass flowrates using single-lens simulations. Sto increases with increasing df under the same downstream pressure and mass flowrate. This is attributed to the fact that the velocities of the gas and particles decrease near the lens orifice with an increase in df. Thus, the particles cannot easily deviate from the streamlines. Thus, the lens is suitable for focusing larger particles corresponding to a larger Sto. In addition, under the same df and downstream pressure, as the mass flowrate increases, Sto decreases. This is attributed to the fact that when the flow rate increases, the radial velocity of the gas at the orifice also increases, causing the particles to deviate from the gas streamlines more easily. Thus, the lens is more suitable for focusing smaller particles corresponding to a smaller Sto. In addition to the differences in Sto values, helium and nitrogen exhibit similar patterns.

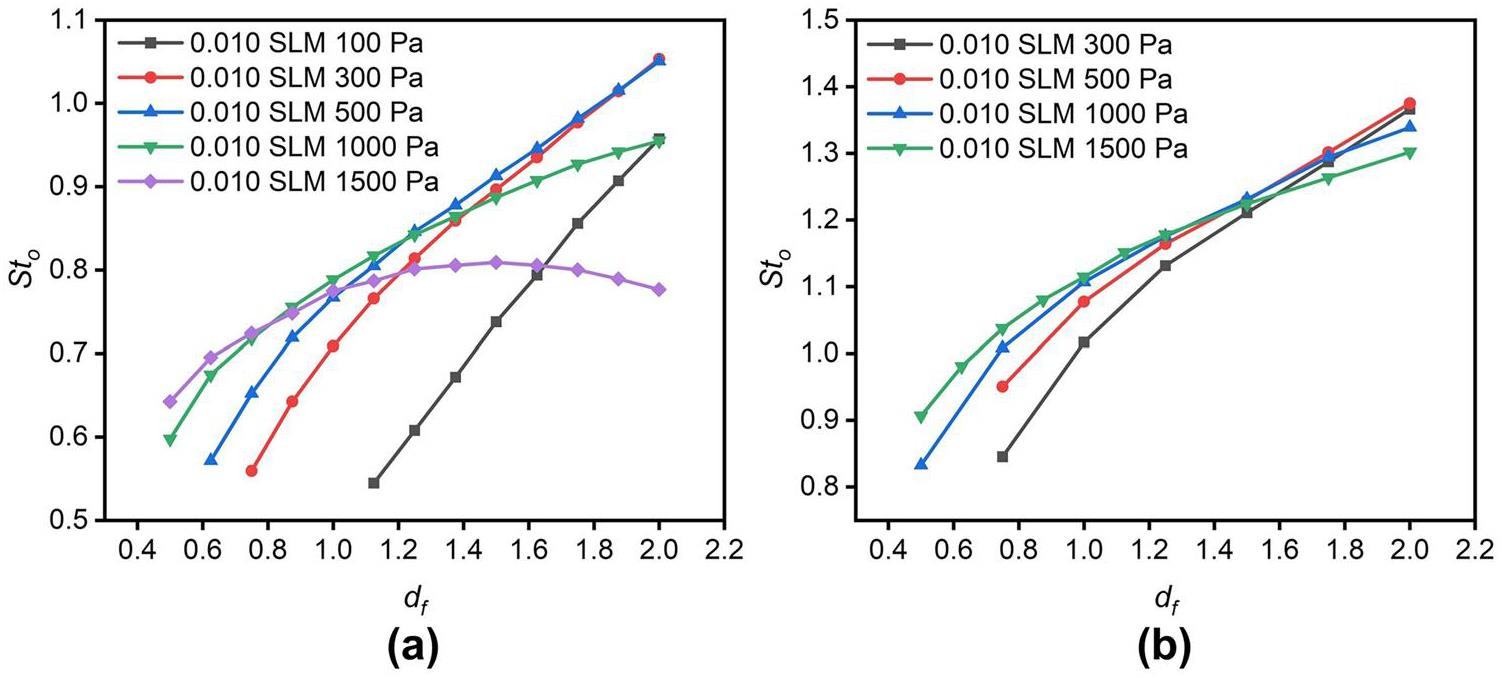

Figure 4 shows the relationship between Sto and df with the same mass flowrate but different downstream pressures based on single-lens simulations. Under the same mass flow rate, the derivative of Sto with respect to df decreases as the downstream pressure increases (i.e., the growth rate of Sto decreases). When the downstream pressure is sufficiently high, Sto decreases with increasing df, as shown by the curve corresponding to 1500 Pa in Fig. 4a. If the two curves intersect, lenses with different downstream pressures have the same Sto value at the intersection point. Eq. 17 indicates that for lenses with the same geometry and flow rate, different particles can be focused by adjusting the pressure. This explains that particles of different sizes can be focused by adjusting the pressure and flow rate while maintaining a fixed geometry for the Uppsala injector [57].

As depicted in Fig. 3 and Fig. 4, Sto typically deviates significantly from 1 due to the influence of various parameters. Each point in the figures represents a simulation conducted under specific conditions. Multiple simulations under the same

Design results of the aerodynamic lens

In the SPI experiments, the size of the particles of interest transitioned from larger viruses to smaller proteins. To achieve the high-resolution imaging of small particles, the particle-beam width must be further reduced and the background scattering noise must be minimized [13]. Based on the requirements of SPI, we designed a new ADL to focus 30–500 nm particles. The optimized design method was used in this process, and Eq. 23 was employed as the functional relationship for Sto. PS spheres with a mass density of 1050 kg/m3 were used in the design, as it is comparable to the density of biological materials. Nitrogen was used as the carrier gas to ensure compatibility with both GDVN and commercial electrospray (TSI-3482). The designed mass flowrate of the carrier gas was 0.01 SLM to minimize background scattering. The designed pressure before the accelerating nozzle was 300 Pa and the tube diameter was 10 mm. Table 1 lists the designed particle diameter and optimal Stokes number of each lens, as well as the pressure before and after each lens. The pressure before the first lens was 483 Pa (i.e., the inlet pressure of the ADL).

| Lens number | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dp (nm) | 500 | 200 | 100 | 50 | 30 |

| 483 | 477 | 463 | 436 | 383 | |

| 477 | 463 | 436 | 383 | 300 | |

| Sto | 0.92 | 0.80 | 0.72 | 0.64 | 0.61 |

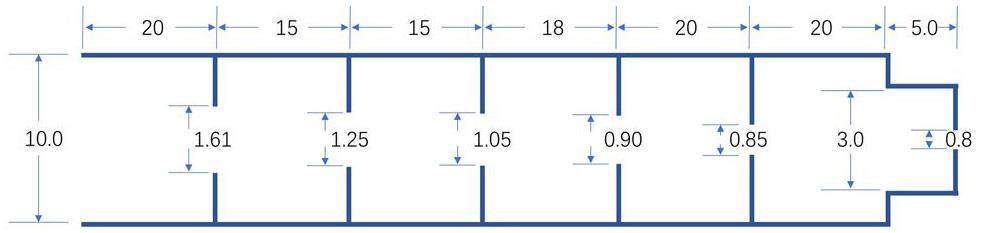

With the inlet pressure and diameter of each orifice already obtained, the redevelopment and approach lengths can be calculated through an overall simulation of ADL, where a sufficiently long length is preset for each spacer. The final spacer lengths for the ADL were then determined based on the simulation results. As shown in Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Material, each L value was preset to 25 mm. For the spacer between the third and fourth lenses, the redevelopment length was 9 mm, and the approach length was 3.8 mm. Therefore, L (18 mm, red line) was determined to be greater than the total length (12.8 mm). Figure 5 shows the final geometric parameters of the ADL. D was approximately six times the diameter of the largest lens orifice.

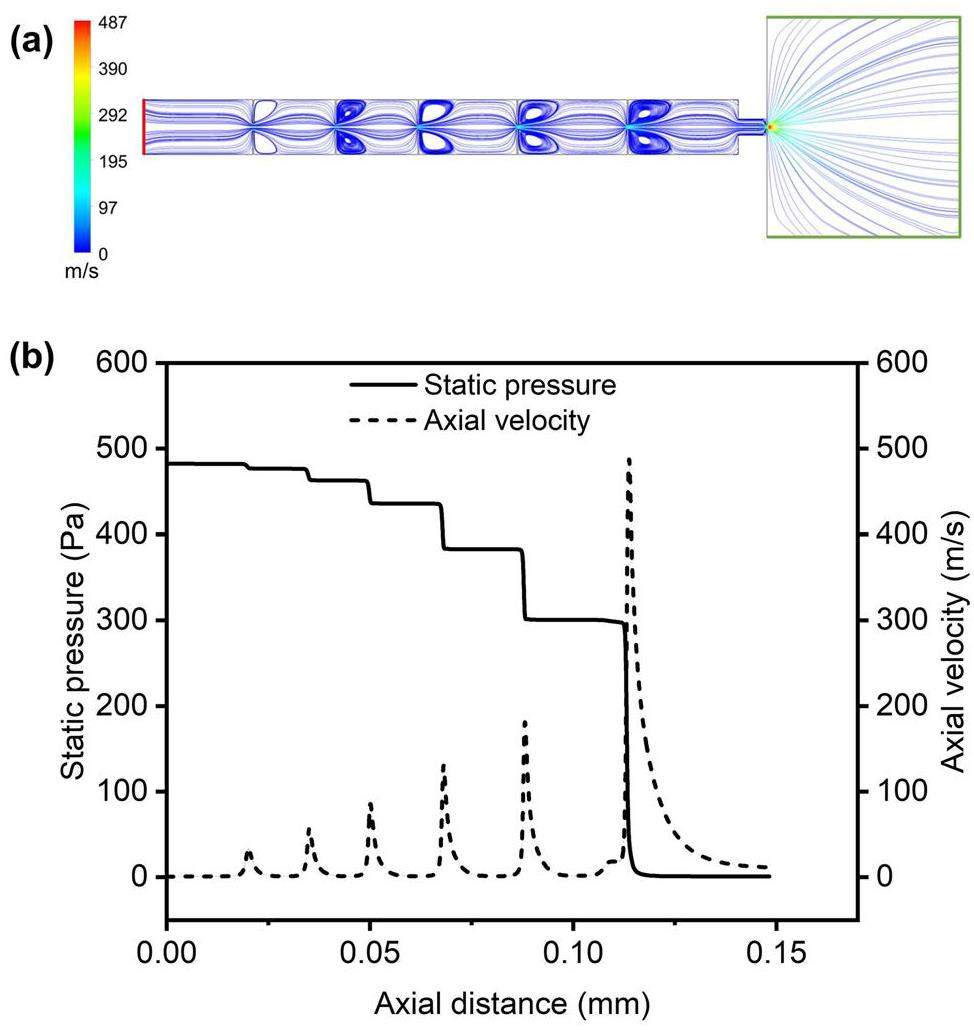

Simulations of the new ADL were performed to predict the behavior of particles. As shown in Fig. 6a, the inlet is defined as the starting plane of the ADL, and the outlet is defined as the boundary of a rectangular area (45 mm × 45 mm) added downstream of the ADL exit. A mass-flow conservation of 2.08 × 10-7 kg/s (0.01 SLM) is used as the inlet condition, and a pressure of 1 Pa is used as the outlet condition. As shown in Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Material, after 16,000 iterations, the continuity residual is 6 × 10-11. The absolute error of the inlet and outlet mass-flow rates is 1 × 10-13 kg/s (i.e., the relative error is 0.005%). The static pressure at the monitoring point upstream of the accelerator nozzle remains almost constant. Therefore, the simulation of the new ADL is considered to be convergent.

Figure 6a shows the simulated flow streamlines in the ADL. The gas contracts rapidly before the lens and expands slowly beyond the lens. The distance between the lenses enables the full development of the flow field, exhibiting a laminar-flow state. Figure 6b shows the simulated static pressure and velocity profiles along the axis. The pressure decreases after the gas passes through the lens. After passing through the five lenses, the pressure decreases by approximately 183 Pa, which is consistent with the designed pressure decrease in Table 1. As the lens diameter decreases, the gas velocity increases. Owing to the significant pressure decrease, supersonic expansion occurs downstream of the acceleration nozzle.

The trajectories of the particles were obtained by injecting 1000 particles with the same diameter at a cross section located 10 mm downstream of the inlet. They are uniformly distributed in this cross section. The initial particle velocity is zero. The particle time-step is limited to a fifth of the particle-relaxation time. The particle beam width (D90) in the simulation is defined as the beam diameter containing 90% of the total particles. They are subjected to both drag and Brownian forces.

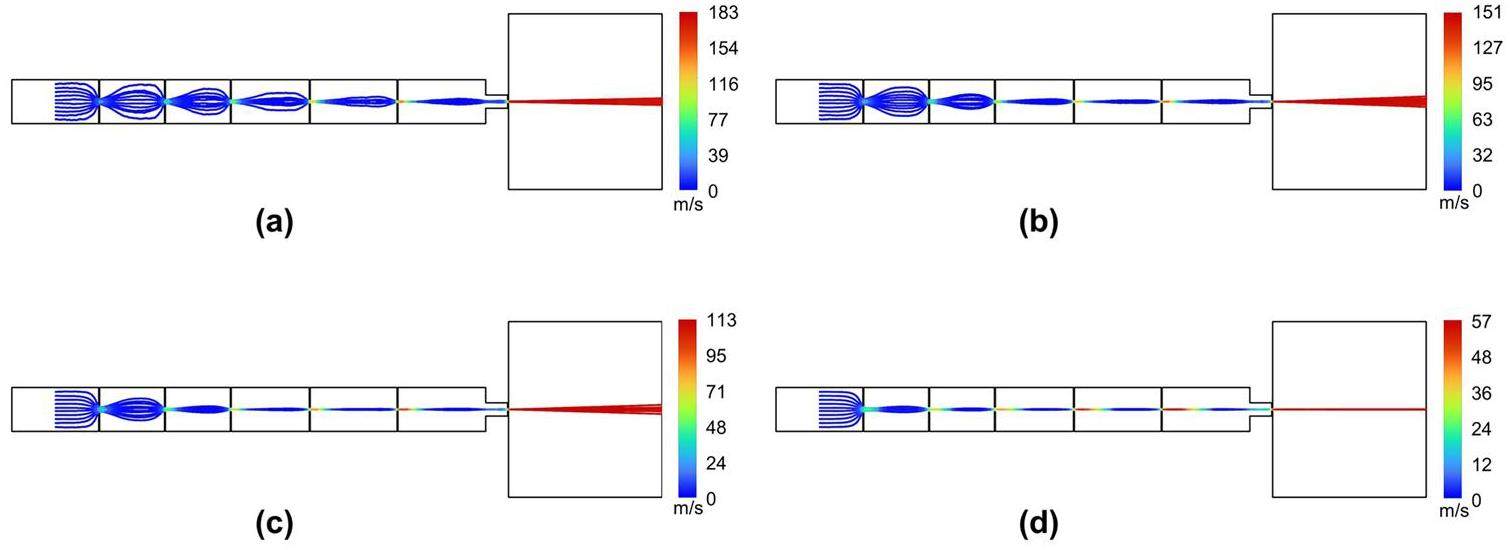

Figure 7 shows the simulated trajectories of PS spheres passing through the ADL. For clarity, only the trajectories of 10 particles are displayed. Owing to the periodic asymmetrical contraction and expansion of the flow field, the particles gradually gathered towards the axis. Larger particles are focused by the front lens, whereas smaller particles are focused by the back lens. The maximum value of the color scale represents the maximum velocity that the particles can reach. As the particle diameter increases, the maximum velocity decreases. This can be explained by the fact that drag forces are less capable of accelerating larger particles with greater inertia under the same flow field.

Furthermore, the particle-transmission rate is an important parameter for evaluating the performance of aerosol injectors. Based on the 1000 particles injected into the new ADL shown in Fig. 7, 30-nm PS spheres had a transmission rate of 90% through the ADL, whereas the transmission rate of the PS spheres larger than 100 nm was close to 100%. The main cause of particle loss is Brownian diffusion, which results in the loss of small particles on the wall. However, studies have shown that for an entire aerosol injector, the main particle loss occurs at the nozzle/skimmer stage rather than at the ADL [58]. Efforts should be made to improve the particle-transmission rate in the nozzle/skimmer stage.

The actual Stokes numbers obtained from the overall ADL simulation are listed in Table 2, where the number following St denotes the particle diameter. The Stokes numbers marked with asterisks correspond to the Sto value derived from the relationship in Table 1. These data are in good agreement, indicating that the design process is effective. Sto decreases with decreasing particle size, which is consistent with the analysis shown in Fig. 3. As the lens number increases, the Stokes numbers of all the particles increases. The Stokes numbers with asterisks form a dividing line that separates Table 2 into two regions. In the region below the dividing line, St is less than Sto when the particles pass through the lenses, indicating that the particles either follow the streamline or experience slight focusing. By contrast, in the region above the dividing line, St is greater than Sto when the particles pass through the lenses. These particles have already been focused by previous lenses and are close to the axis where the radial flow velocity is low; therefore, they are not significantly defocused. These analyses align with the particle trajectories shown in Fig. 7.

| Lens number | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| St-500 nm | 0.93* | 2.01 | 3.60 | 6.40 | 9.97 |

| St-200 nm | 0.37 | 0.80* | 1.44 | 2.56 | 3.99 |

| St-100 nm | 0.19 | 0.40 | 0.72* | 1.28 | 1.99 |

| St-50 nm | 0.09 | 0.20 | 0.36 | 0.64* | 1.00 |

| St-30 nm | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.38 | 0.60* |

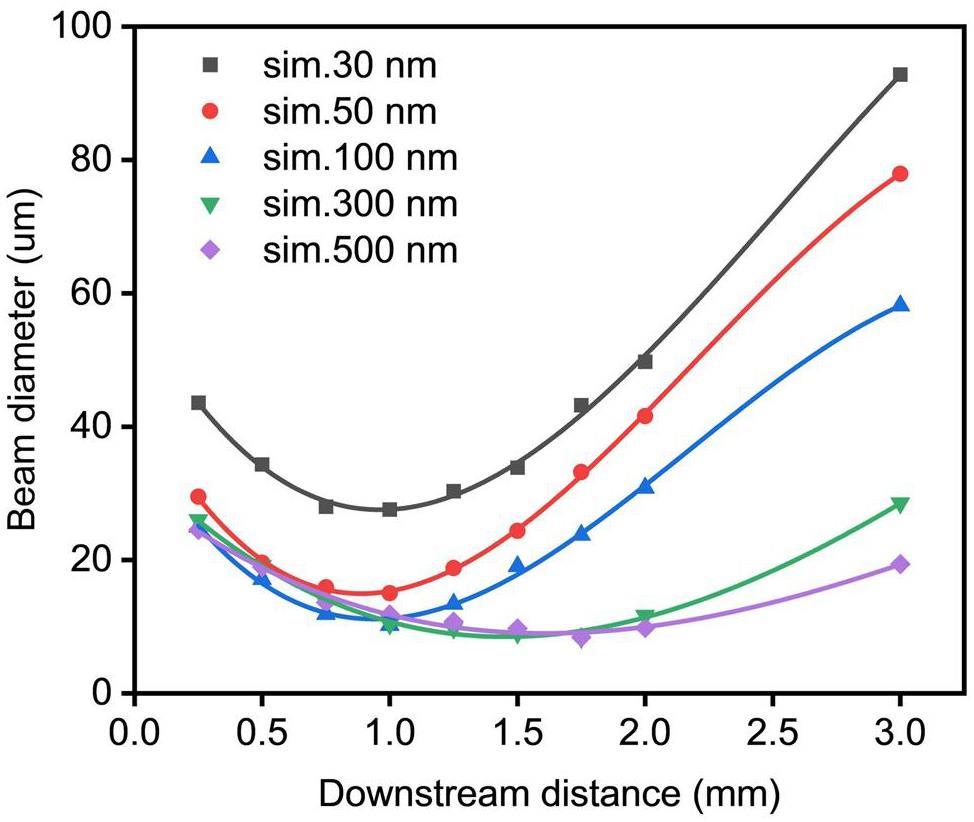

Figure 8 shows the simulated evolution of the beam width with the downstream distance from the ADL exit. The minimum beam width of the particles decreases with increasing particle diameter. Because of the influence of Brownian motion, the ADL has poor focusing effects on smaller particles. For example, the minimum beam width is 28.0 μm for 30-nm particles, and 8.4 μm for 500-nm particles. In addition, as the particle size increases, the focal point gradually moves away from the nozzle exit with a small divergence angle. The particle-beam focus position ranges from 0.8 to 2 mm in the simulation.

Experimental results

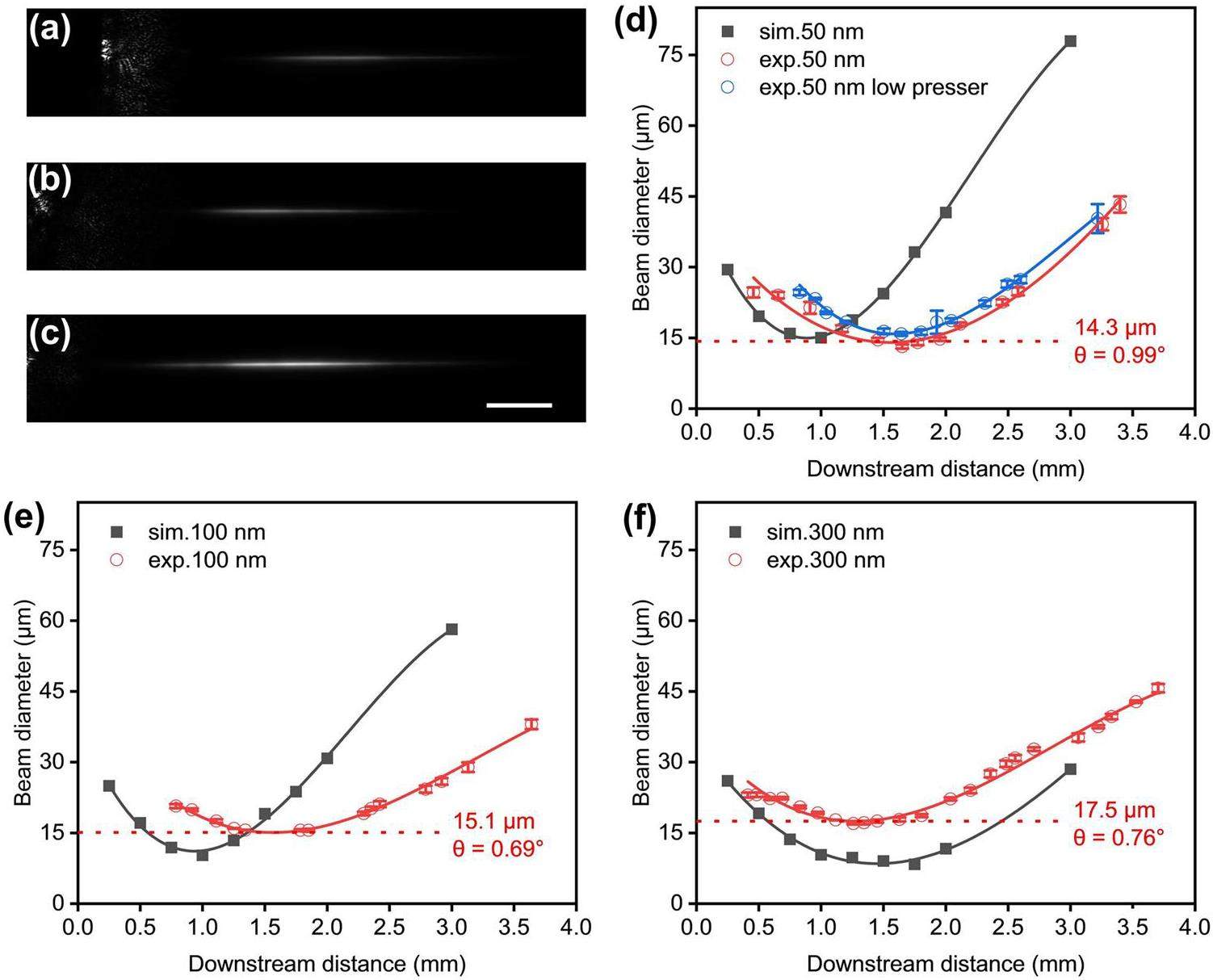

The new ADL was commissioned using the PS spheres. During the commissioning, the inlet pressure of the ADL was set to 483 Pa. Figure 9a–c show that PS spheres formed long and straight beams in a vacuum after passing through the ADL. The particle beams were illuminated by a laser. The beams became dim at both ends owing to a decrease in laser-spot intensity. The irregular bright spots on the left side were a part of the ADL accelerator nozzle. Figure 9d–f show the comparison between the experimental-beam width measured at 483 Pa (red circles) and the corresponding simulated-beam width (black dots). The experimental-beam width curves were fitted with standard errors using repeated measurements. Based on the experimental data, the beam width initially decreased and then increased, forming a focus approximately 1.5–2 mm from the ADL exit. For all tests, the particle-beam width at the focus was less than 20 μm. Among them, the 50-nm particles had the smallest beam width (14.3 μm) and the largest divergence angle (0.99°). Compared with the Uppsala injector, which can focus 70-nm PS spheres to 18 μm with a divergence angle of 1.9° and gas-flow rate of approximately 0.03 SLM [57], the new ADL generated a smaller beam width on smaller particles with a lower flow rate (0.01 SLM). A smaller beam width can increase the sample density, which helps improve the hit rate. For particles larger than 100 nm, we could not directly compare our ADL with the Uppsala injector owing to the different flow rates and particle sizes [57], although our ADL generally demonstrated a comparable performance.

Moreover, we tested a beam width of 50-nm particles at a lower inlet pressure of 367 Pa (blue circles in Fig. 9d). The beam width at the focus was 15.9 μm, which was 11% larger than the beam width under the designed pressure (483 Pa). However, according to the simulation estimates, using a lower inlet pressure resulted in an approximately 30% reduction in the flow rate compared to the designed pressure. Adjusting the inlet pressure may further reduce the flow rate without significantly increasing the beam width or expanding the particle-diameter range that can be focused by the ADL.

For the larger divergence angles for small particles, the experiments and simulations are consistent; however, some deviations are observed for the smallest beam width. As shown in Fig. 9d–f, the experimental and simulated results for small particles are in good agreement; however, the simulation underestimates the beam width for large particles. For example, the minimum beam width measured in the experiment for 300 nm particles was twice that of the simulation prediction. Several possible reasons exist for the deviations between the simulation and experiment. Our design may amplify the simulation error of large particles. In our design, when large particles pass through the front lens, they are focused near the axis. Even if the actual value of St is large at the rear lens, the particles will not be significantly defocused when passing through the lens. For example, although the Stokes number of the 500-nm PS particles in the fifth lens is large (see Table 2), the particles are not significantly defocused (see Fig. 7d). However, simulation errors are inevitable. If the true radial position of the particle is farther from the axis than numerically predicted, this deviation is amplified by the multiple lenses behind it. In contrast, small particles are slightly focused by the front lens owing to their small St value (e.g., 30-nm particles in Fig. 7a). They are then effectively focused by the rear lens, and the deviation is not amplified. Consequently, the simulation underestimates the beam width of large particles rather than that of small particles, which agrees with the observed phenomenon. However, we considered not only the drag force, but also the Brownian force in the overall simulation of the ADL. However, using the Brownian-motion model under low-pressure conditions (a few hundred Pascals) may result in an increased error. The combination of these two factors can lead to deviations between the simulations and experiments. In addition, the electrostatic forces between the particles can lead to mismatches between the current numerical and experimental results. The charging of PS particles in an aerosol beam atomized by a GDVN was observed [59]. If the particles are very close to each other, the repulsion between particles with the same charge may widen the particle beam.

Conclusion

A functional relationship between the most important parameter (Sto) and the three variables (df, P2,

Using the optimized design method, a new ADL was designed to focus 30—500-nm PS spheres to meet the requirements of SPI. The particle-beam width at the focus was approximately 15 μm for all tested particles (50, 100, and 300 nm). The flow rate was only 0.01 SLM, which helped to reduce gas background scattering, especially for weakly scattering bio-samples. In addition, compared with the current injector used in SPI [23, 57], the new ADL can focus 50-nm particles into a narrower beam with a lower flow rate. Simultaneously, the new ADL could focus on a relatively wide range of particles without requiring adjustments to the inlet pressure. The experimental results demonstrated the effectiveness of the proposed design method. Further experiments and optimization will unlock the potential of the optimized design method and provide important support for high-resolution 3D imaging and structural dynamics studies of nanoparticles with XFELs in future.

To further improve the ADL performance, some optimizations must be considered. First, Brownian motion contributes significantly to the diffusion of nanoparticles, resulting in particle loss and the broadening of the ADL. Decreasing the temperature [60] of the carrier gas or increasing the pressure within the ADL will reduce the particle-diffusion coefficient, which can suppress Brownian diffusion and help obtain a tight particle beam. In addition, when increasing the pressure in the ADL, the size of the lens orifices and nozzles must be reduced to maintain a low gas flow. The high pressure and small orifices increase the flow velocity in the ADL, thereby reducing the time required for particles to pass through it, which helps reduce Brownian broadening. Moreover, in addition to the drag force, other forces, such as the Saffman lift and photophoretic forces, can be applied to drive the particles towards the axis, thereby enhancing the focusing effect. Finally, using helium with a smaller molecular weight than that of the carrier gas instead of nitrogen will further reduce background scattering.

Review of fully coherent free-electron lasers

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 29, 160 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-018-0490-1Features and futures of X-ray free-electron lasers

. Innovation. 2,Megahertz single-particle imaging at the European XFEL

. Commun. Phys. 3, 97 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-020-0362-yPotential for biomolecular imaging with femtosecond X-ray pulses

. Nature 406, 752-757 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/35021099Femtosecond diffractive imaging with a soft-X-ray free-electron laser

. Nat. Phys. 2, 839-843 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys461Megahertz data collection from protein microcrystals at an X-ray free-electron laser

. Nat. Commun. 9, 3487 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05953-4Evaluation of the performance of classification algorithms for XFEL single-particle imaging data

. Iucrj. 6, 331-340 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1107/S2052252519001854Single mimivirus particles intercepted and imaged with an X-ray laser

. Nature. 470, 78-81 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09748Considerations for three-dimensional image reconstruction from experimental data in coherent diffractive imaging

. IUCrJ. 5, 531-541 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1107/S2052252518010047High-throughput imaging of heterogeneous cell organelles with an X-ray laser

. Nat. Photonics. 8, 943-949 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2014.270Correlations in scattered X-ray laser pulses reveal nanoscale structural features of viruses

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119,Single-particle imaging without symmetry constraints at an X-ray free-electron laser

. IUCrJ. 5, 727-736 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1107/S205225251801120xObservation of a single protein by ultrafast X-ray diffraction

. Light-Sci. Appl. 13, 15 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-023-01352-73D diffractive imaging of nanoparticle ensembles using an x-ray laser

. Optica. 8, 15-23 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1364/Optica.410851Perspectives on single particle imaging with x rays at the advent of high repetition rate x-ray free electron laser sources

. Struct. Dyn.-US. 7,Coherent diffraction imaging of cells at advanced X-ray light sources

. Trac-Trends Anal. Chem. 171,Coulomb explosion imaging of small polyatomic molecules with ultrashort x-ray pulses

. Phys. Rev. Res. 4,Numerical analysis of X-ray free-electron laser interaction with metal ruthenium using the two-temperature model

. Nuclear Techniques (in Chinese) 47,First commissioning results of the coherent scattering and imaging endstation at the Shanghai soft X-ray free-electron laser facility

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 114 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01103-0Fixed target single-shot imaging of nanostructures using thin solid membranes at SACLA

. J. Phys. B-At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 49,Gas dynamic virtual nozzle for generation of microscopic droplet streams

. J. Phys. D-Appl. Phys. 41,Electrospray sample injection for single-particle imaging with x-ray lasers

. Sci. Adv. 5,Helium-electrospray improves sample delivery in X-ray single-particle imaging experiments

. Sci Rep. 14, 4401 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-54605-9Imaging single cells in a beam of live cyanobacteria with an X-ray laser

. Nat. Commun. 6, 5704 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6704Single-particle imaging by x-ray free-electron lasers-How many snapshots are needed?

Struct. Dyn.-US. 7,The European X-ray Free-Electron Laser: toward an ultra-bright, high repetition-rate x-ray source

. High Power Laser Sci. Eng. 3,The MING proposal at SHINE: megahertz cavity enhanced X-ray generation

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 6 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01151-6Overview of CW electron guns and LCLS-II RF gun performance

. Front. Physics 11,Design optimization of 3.9 GHz fundamental power coupler for the SHINE project

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 132 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00959-yDesign optimization and cold RF test of a 2.6-cell cryogenic RF gun

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 97 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00925-8FLASH–the first soft x-ray free electron laser (FEL) user facility

. J. Phys. B-At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 43,The linac coherent light source

. J. Synchrot. Radiat. 22, 472-476 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1107/S1600577515005196Design of a 162.5 MHz continuous-wave normal-conducting radiofrequency electron gun

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 31, 110 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-020-00817-3AGIPD, a high dynamic range fast detector for the European XFEL

. J. Instrum. 10,Generating particle beams of controlled dimensions and divergence: I. Theory of particle motion in aerodynamic lenses and nozzle expansions

. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 22, 293-313 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1080/02786829408959748A new time-of-flight aerosol mass spectrometer (TOF-AMS)–instrument description and first field deployment

. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 39, 637-658 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1080/02786820500182040Generating particle beams of controlled dimensions and divergence: II. Experimental evaluation of particle motion in aerodynamic Lenses and Nozzle Expansions

. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 22, 314-324 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1080/02786829408959749An experimental study of nanoparticle focusing with aerodynamic lenses

. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 258, 30-36 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijms.2006.06.008A design tool for aerodynamic lens systems

. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 40, 320-334 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1080/02786820600615063A numerical characterization of particle beam collimation by an aerodynamic lens-nozzle system: Part I. An individual lens or nozzle

. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 36, 617-631 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1080/02786820252883856Development and characterization of an aerosol time-of-flight mass spectrometer with increased detection efficiency

. Anal. Chem. 76, 712-719 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1021/ac034797zMicropattern deposition of colloidal semiconductor nanocrystals by aerodynamic focusing

. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 44, 55-60 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1080/02786820903376876Optimizing the geometry of aerodynamic lens injectors for single-particle coherent diffractive imaging of gold nanoparticles

. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 54, 1730-1737 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1107/S1600576721009973Development and experimental evaluation of aerodynamic lens as an aerosol inlet of single particle mass spectrometry

. J. Aerosol. Sci. 39, 287-304 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaerosci.2007.10.011New aerodynamic lens injector for single particle diffractive imaging

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A 1058,Microscopic force for aerosol transport

. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.10652CMInject: Python framework for the numerical simulation of nanoparticle injection pipelines

. Comput. Phys. Commun. 270,On the resistance experienced by spheres in their motion through gases

. Phys. Rev. 23, 710-733 (1924). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.23.710Aerodynamic focusing of nanoparticles: I. Guidelines for designing aerodynamic lenses for nanoparticles

. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 39, 611-623 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1080/02786820500181901Slip correction measurements for solid spherical-particles by modulated dynamic light-scattering

. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 22, 202-218 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1080/02786829408959741Definitive equations for the fluid resistance of spheres

. Proc. Phys. Soc. 57, 259 (1945). https://doi.org/10.1088/0959-5309/57/4/301Dispersion and deposition of spherical-particles from point sources in a Turbulent Channel Flow

. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 16, 209-226 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1080/02786829208959550Aerodynamic focusing of nanoparticles: II. Numerical simulation of particle motion through aerodynamic lenses

. Aerosol. Sci. Tech. 39, 624-636 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1080/02786820500181950A numerical characterization of particle beam collimation by an aerodynamic lens-nozzle system: Part I. An individual lens or nozzle

. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 36, 617-631 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1080/02786820252883856Numerical characterization of particle beam collimation: Part II integrated aerodynamic-lens–nozzle system

. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 38, 619-638 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1080/02786820490479833Critical flowmetering: The characteristics of cylindrical nozzles with sharp upstream edges

. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow. 1, 123-132 (1979). https://doi.org/10.1016/0142-727X(79)90028-6Rayleigh-scattering microscopy for tracking and sizing nanoparticles in focused aerosol beams

. IUCrJ. 5, 673-680 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1107/S2052252518010837Optimizing aerodynamic lenses for single-particle imaging

. J. Aerosol. Sci. 124, 17-29 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaerosci.2018.06.010Charge-state distribution of aerosolized nanoparticles

. J. Phys. Chem. C. 125, 25794-25798 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.1c06912Controlled beams of shock-frozen, isolated, biological and artificial nanoparticles

. Struct. Dyn.-US. 7,The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-025-01702-7.