Introduction

An electromagnetic calorimeter (ECAL) is a detector used to measure the energy and momentum of high-energy electromagnetic particles (e.g., electrons and photons). In particle physics, ECALs can measure the electromagnetic showering of particles within it and determine the energy and momentum of electromagnetic particles based on energy deposition, providing important information for understanding the properties and interactions of elementary particles.

A high-performance ECAL is crucial for the precise detection of high-energy physical phenomena and has been validated in many experiments [1-4]. For instance, in the context of the LHCb experiment, during Runs 1 and 2 of the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), approximately 33% of the decay products of heavy-flavor particles are neutral particles, which decay into photons, such as π0 [5]. These photons exhibit a broad energy spectrum, ranging from a few gigaelectronvolts to several hundred gigaelectronvolts [6]. Owing to the outstanding performance of ECAL in the LHCb [7, 8], Runs 1 and 2 yielded many impactful studies involving photons, π0s, and electrons. This research explored photon polarization in the

In pursuit of new physics at the LHC, a high-luminosity LHC (HL-LHC) project was proposed to enhance the accumulation of collision data within a shorter timeframe [16-18]. Operating with an instantaneous luminosity of

The showering process of electromagnetic particles in an ECAL is influenced by factors such as particle type and incident energy, which in turn affect the distribution of the deposited energy [25]. An ECAL equipped with multiple readout channels spanning both the transverse and longitudinal directions facilitates the capture of time, energy, and other readout data in dual dimensions. This capability significantly enhances our comprehensive understanding of the physical processes within the ECAL across multiple dimensions, ultimately leading to improved accuracy in reconstructing the energy and momentum of the particles. Therefore, a longitudinally segmented ECAL has been considered a baseline design for upgrades in many experiments.

The development of event reconstruction algorithms that fully exploit the energy, position, and time information acquired from longitudinally segmented ECAL will enhance the precision of energy-momentum reconstruction, cluster splitting, and particle identification, thereby facilitating the achievement of defined physical objectives. However, this also introduces new challenges in the reconstruction, matching, and efficient utilization of longitudinal-layer information. To leverage the advantages of layered readouts in forthcoming high-energy physics experiments, such as CMS and ALICE [26-31], diverse software frameworks and reconstruction algorithms have been devised and customized to effectively utilize and store layered information.

Building on this background, this study presents a comprehensive software framework tailored for a longitudinally segmented ECAL, along with the development of a layered clustering algorithm and cluster correction workflow. The layered reconstruction framework outlined in this study merges data from all the layers to identify potential Cluster3D candidates. Subsequently, a seed is identified in each layer from the readout cells of the Cluster3D candidates. Utilizing these seeds as focal points, Cluster2Ds in all readout layers are reconstructed (the definitions of Cluster3D and Cluster2D are elaborated on in subsequent sections). Finally, the performance is compared with that of an unlayered-reconstruction algorithm that combines the information from the corresponding readout units in each layer based on the single-photon resolution, as well as the reconstruction resolution and efficiency for π0 from

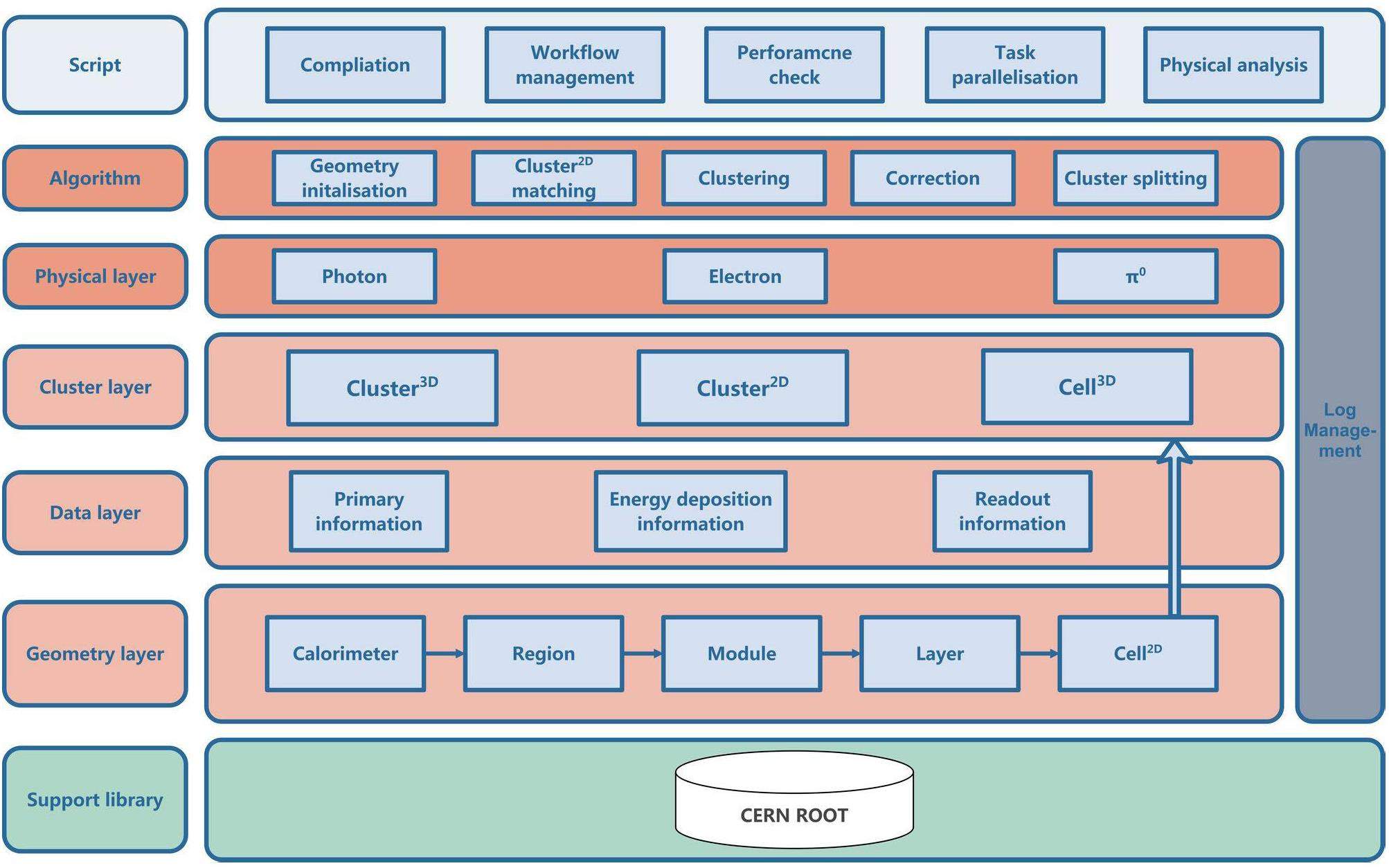

Software framework and data structures

The layered reconstruction framework is shown in Fig. 1. The modeling of the detector geometry is the cornerstone of the framework. To adapt as many longitudinally segmented ECAL structures as possible, the following data structures were constructed to describe and carry the geometrical information of the ECAL in this framework.

Calorimeter: It represents the ECAL and also stores the absolute coordinates and size of the entire ECAL in space.

Region: It is a virtual geometry containing a series of modules with identical detector structure, material, and installation angle. It was used to store the calibration and cluster correction parameters for this series of modules.

Module: It represents the minimum installation unit and stores the absolute coordinates, size and installation angle of itself.

Layer: It is the key geometric data structure in this framework and physically represents a longitudinal segment of the module. It stores all Cell2Ds located in a segmented readout layer in a module.

Cell2D: It represents the minimum readout channels in modules and contains information regarding the mounting position of the readout cell, signal, and timestamp.

Based on the aforementioned basic geometric structure, the following cluster data structures, containing two or more Cell2Ds, were constructed, which correspond to the cluster layer in the software framework. The specific construction method for the data structures is described in Sect. 3.1.

Cell3D It consists of multiple Cell2Ds in the longitudinal direction.

Cluster2D It consists of multiple Cell2Ds at the same layer.

Cluster3D It consists of a Cluster2D and multiple Cell2Ds in each layer and would be considered as a candidate for photons, electrons, or merged π0s.

Reconstruction

Based on the layered reconstruction framework, this section describes the reconstruction algorithm for Cluster3D, which is a candidate for electromagnetic particles (

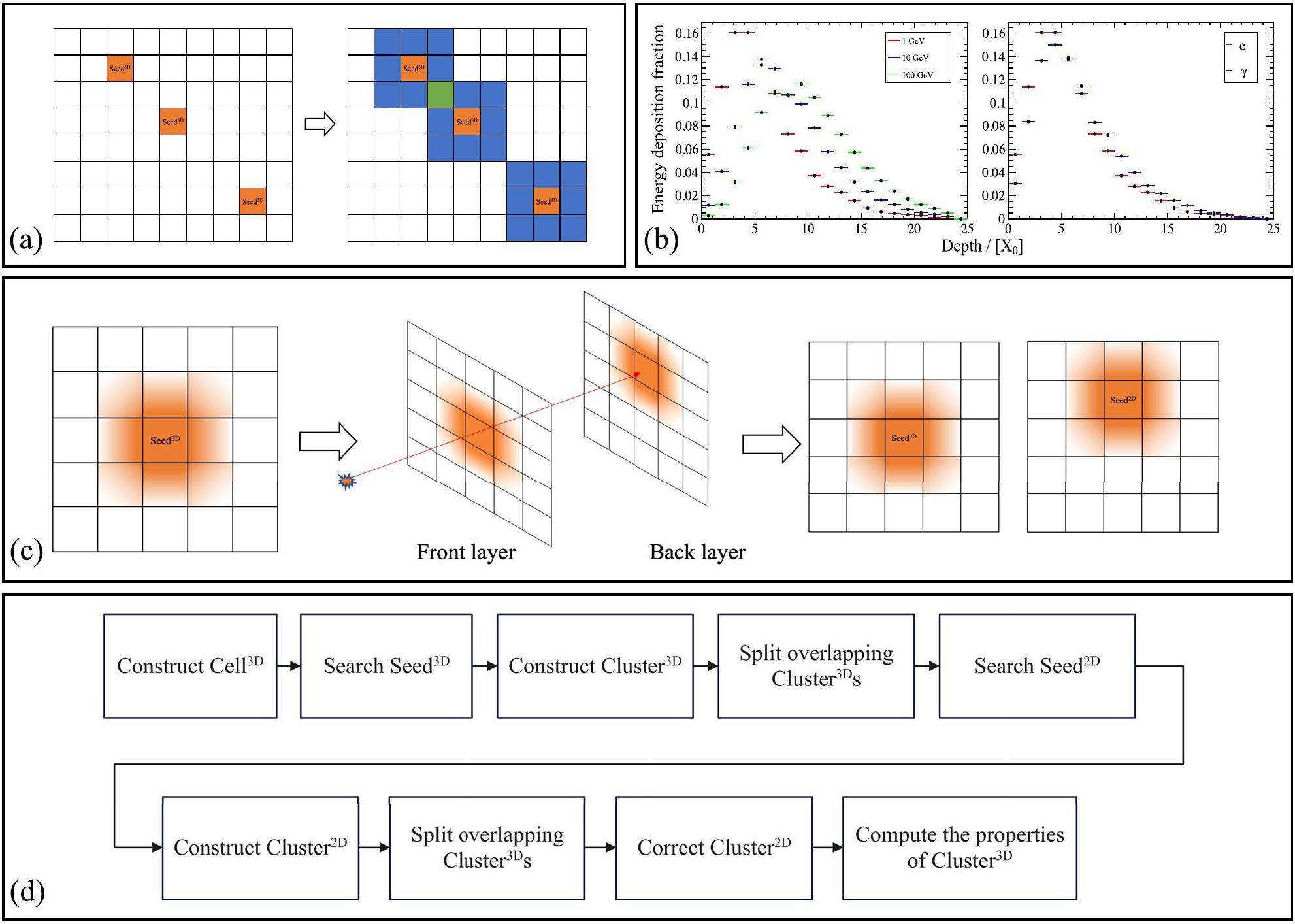

Layered clustering

The algorithm outlined in this section details the methodology used to finalize the construction of Cluster3Ds and provides particle reconstruction information at each readout layer in the form of Cluster2Ds. A flowchart of the layered clustering algorithm is shown in Fig. 2d. First, the algorithm searches for Seed3Ds on a single layer, which includes a realistic readout layer with a smaller transverse showering width, as well as a virtual single-layer calorimeter constructed by merging information from all readout layers and constructing temporary Cluster3Ds in the virtual single-layer calorimeter from Seed3Ds. This approach was motivated by two primary considerations.

The first and most important point is that constructing Cluster2D in each layer and performing layer-by-layer matching consumes a significant amount of computation time. First, performing 2-dimensional clustering in a single layer ensures efficient online triggering.

Second, in layers with narrower transverse cluster development, there is a chance of discovering more non-overlapping clusters. However, owing to the narrower transverse cluster development, the energy deposition is lower. Owing to sampling fluctuations, some particles may not have formed effective seeds in this layer. Therefore, searching for Seed3Ds in both Cell3Ds and Cell2Ds in layers with narrower cluster development will help achieve a balance between cluster separation and reconstruction efficiency.

Subsequently, based on the temporary Cluster3Ds, we construct Cluster2Ds located in different layers to obtain the final Cluster3Ds. Information from different layers was initially integrated by constructing a Cell3D. The details of each step of the layered clustering algorithm are as follows:

Constructing Cell3D

To integrate the information in each readout layer, the information from the corresponding Cell2Ds in both layers is utilized to establish a novel data structure known as Cell3D. Specifically, Cell3Ds were systematically constructed across the transverse section of the ECAL, with a radius equivalent to the module’s Molière radius. Along the longitudinal direction of the ECAL, all Cell2Ds falling within the transverse span of Cell3D are amalgamated into Cell3D, with each Cell2D being included only once. The energy of Cell3D is determined by the cumulative energy of the Cell2Ds it encompasses, and the position of Cell3D is defined as its geometric center.

Searching Seed3D and constructing temporary Cluster3D

When an electromagnetic particle strikes the ECAL, it radiates energy outward from the impact point, typically resulting in the formation of Cell2D and Cell3D with the highest local energy deposition near the impact point. Therefore, as illustrated in Fig. 2a, the initial step in clustering is to iterate through all Cell3Ds and Cell2Ds in specific layers to identify the Cell3D and Cell2D layers that exhibit the highest local energy deposition. For the local maximum Cell2D, the corresponding Cell3D is considered a Seed3D. Simultaneously, the local maximum Cell3D is considered as Seed3D. seed denotes the initial step in the clustering process.

To prevent faker Seed3Ds during the seeding process, all identified Seed3D s must satisfy a transverse momentum cut, typically defined as greater than 50 MeV in this framework. The threshold value of this cut can be lowered if required to investigate phenomena related to soft photons or electrons. All Seed3Ds passing through the cut are labeled as final Seed3Ds and stored.

As a result of transverse particle showering, the energy is not fully contained within Seed3D. Hence, it is imperative to encompass a specific range of Cell3Ds around Seed3D to guarantee optimal coverage of all energy deposits from the particles. In this study, we followed the methods described in Ref. [34], which uses a fixed-size window to incorporate Cell3Ds. The specific procedure is as follows: Centered around the Seed3Ds, the Cluster3Ds are formed by incorporating all Cell3Ds within a 3×3 window around the Seed3Ds, as illustrated in Fig. 2a. Additionally, the Cell2Ds from all layers encompassed by the Cell3Ds are also included as members of the Cluster3Ds. However, when the Seed3D s are located at the boundary of the region, special treatment is required because of the different types of Cell3Ds in different regions. Around Seed3D, within a radius of 1.5 times the size of Seed3D, Cell3Ds belonging to other regions are also included. In this study, a detailed description of the process is not provided. This process may lead to Cluster3D at the boundary containing several Cell3Ds, which may be greater or less than nine, and its shape may be irregular. This requires separate handling of Cluster3D at the boundary in the Cluster3D correction process described later.

In the subsequent steps, further layered modifications were made to the Cell2Ds included in Cluster3D. Therefore, Cluster3D obtained in this section is referred to as a temporary Cluster3D.

Searching Seed2D and reconstructing Cluster2D

Because of the incident angle of the particles and the rotation of certain modules, as the shower evolves longitudinally, the energy centroid of the shower varies across different layers. This results in Cell2D with the highest local energy in each layer, not always being encompassed within Seed3D, as shown in Fig. 2c.

To identify the Seed2D in each layer, we iterate through the Cell2Ds of each layer in the temporary Cluster3D and select the Cell2D with the highest energy as the Seed2D of that layer. Moreover, the overlap of Cluster2Ds results in an increased accumulation of energy in shared Cell2Ds, which may cause the energy of a shared Cell2D to exceed that of a Seed2D, leading to the misidentification of a shared Cell2D as a Seed2D. Therefore, before searching for Seed2D, energy splitting must be performed on all overlapping Cluster2Ds, as shown in Fig. 2d, and is discussed in detail in Sect. 3.2.3.

Subsequently, Cluster2Ds are formed with Seed2Ds as the center, and all Cell2Ds within the Molière radius of the module centered on Seed2Ds in the same layer are included in the Cluster2Ds. The raw energy, position, and timestamp of the Cluster2Ds were computed using the following equations:

Finally, a new Cluster3D containing Cluster2Ds in all layers is constructed. The raw energy of Cluster3D is computed using the following formula:

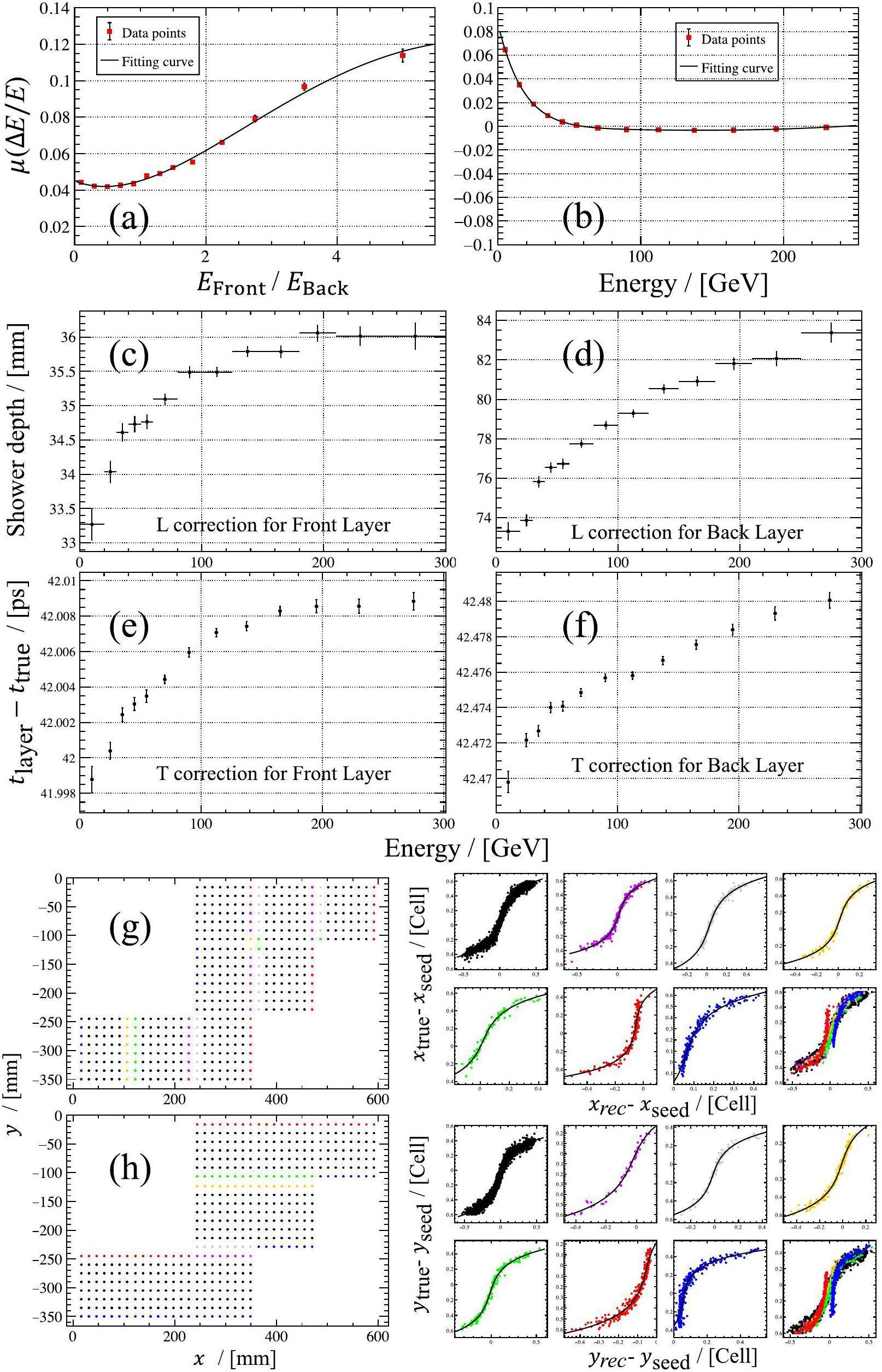

Cluster3D correction

The goal of the Cluster3D correction is to reduce the bias between the reconstructed and actual values, while also aiming for the minimal standard deviation of the reconstructed values. In the layered reconstruction framework, the position and timestamp of Cluster3D are calculated and corrected from the Cluster2D level. As described in Sect. 3.1, the raw position and timestamp of Cluster2D can be calculated using information from the Cell2Ds in Cluster2D. Subsequently, the raw position and timestamp information of Cluster2D are corrected, and the position and timestamp information of Cluster3D are calculated using the corrected Cluster2D. The energy of Cluster3D was also corrected using the energy ratios of Cluster2Ds in different layers. To provide a more detailed illustration of the specifics of layered corrections, Fig. 3 also displays some examples of the longitudinally segmented PicoCal in LHCb Upgrade slowromancap 2@, where Front and Back represent the front and back layers of the abovementioned ECAL.

Energy correction

The objective of energy correction is to correct the energy of Cluster3D to match that of the incident particles. Errors in reconstructing the energy of an incident particle typically stem from the following sources:

Intrinsic error of ECAL readout cell: It comes from the response linearity of sensitive materials, thermal noise in electronic systems, sampling errors in analog to digital converters (ADC), etc.

Calibration error of the readout cell: The shower development in the longitudinal direction is energy related, and the proportion of physical processes dominated in energy deposition changes at different stages of shower development. This leads to changes in the sampling fraction of the ECAL, which ultimately affects the calibration of the readout cell.

Leakage of energy: It is due to the incomplete deposition of particle energy in ECAL and the use of finite-sized windows during clustering.

Fitting error of calibration and correction parameters: It is typically expressed as a constant term in the energy resolution.

In the layered framework of this study, the energy correction of Cluster3Ds was divided into two steps, as shown in Fig. 3a and Fig. 3b. The initial correction of the energy of Cluster3D was performed based on the energy ratios of Cluster2Ds in different layers. As shown in Fig. 3a, in the example based on PicoCal, we first correct the bias between the reconstructed Cluster3D energy and true energy based on the energy ratio of the front layer to the back layer. Subsequently, as illustrated in Fig. 3b, further correction of the energy of Cluster3Ds is conducted based on the total energy of Cluster3Ds, which reduces the bias in the low-energy region.

Position and time correction

When a particle passes through the ECAL, it showers and deposits energy along its momentum direction. The center of gravity of the deposited energy in each layer can be considered a point in the direction of the particle momentum. In the layered reconstruction framework, the position of Cluster2D is regarded as the reconstructed position of the center of gravity. Furthermore, Cluster2Ds also provide a timestamp, which is related to the hit time of the particle, for the layers to which they belong. For the position and time correction in this study, layered correction is applied to Cluster2Ds firstly, followed by the utilization of the corrected information from Cluster2Ds to calculate the information of Cluster3Ds.

The purpose of position correction is to correct the reconstructed position of Cluster2D as accurately as possible to the center of gravity of the energy deposited by the particles in each layer.

For Cluster2D, the x/y position information was derived from the energy-weighted positions of the Cell2Ds. Based on the model described in Ref. [35], we define Δrrec as the position of Cluster2D minus the position of Seed2D, and Δrtrue as the position of the true transversal energy barycenter minus the position of Seed2D, in each layer. This study explored the relationship between Δrrec and Δrtrue. As shown in Fig. 3g and Fig. 3h, the shape of this relationship is like an S, so we also call the process of correcting the x/y coordinates “S correction”. The shape of S is affected by the location of Seed2D. When Seed2D is positioned at the boundaries of the region, the introduction of a varying cell size Cell2D and the presence of installation gaps affect the impact on the S shape. This results in a different S shape for Cluster2Ds located at the boundary of the region compared with those inside the region, as illustrated in Fig. 3g and Fig. 3h.

The z coordinate of the center of gravity of the deposition energy is typically used to evaluate the depth of the shower. Owing to the typically small granularity and thick layers of ECAL in the longitudinal direction, the direct use of the z-coordinate information of Cell2D to reconstruct the z-coordinate of the gravity center of the deposition energy in each layer introduces substantial uncertainty. Therefore, the reconstruction of the z-coordinate is typically performed based on the energies of the incident particles. As shown in Fig. 3c, and Fig. 3d, the shower depth (the difference between the z coordinate of the shower and the z coordinate of the front face of the module) is logarithmically related to the incident particle energy, because the pair production of electrons dominates the energy deposition [36]. This is the rationale behind the term "L correction" for this correction step. By leveraging this correlation, we can deduce the z-coordinates of Cluster2D based on the energy of the incoming particles.

For the Cluster2Ds, the positions obtained by the above position correction were also projected onto the front surface of ECAL and then used in subsequent steps to calculate the position information of the Cluster3Ds.

In this study, the timestamp of the Seed2Ds were used as the timestamp for Cluster2Ds in the preliminary study. The purpose of time correction is to determine the time difference between the timestamps of Cluster2D in each layer and the moment when the particle reaches a specific reference plane. This time difference is employed to correct the timestamp of Cluster2D to an accurate time on a designated reference plane. The front surface of ECAL was used as the reference plane for time correction in this study. This time difference is related to the energy of the incident particle, and the correction results are shown in Fig. 3e and Fig. 3f. Furthermore, if there is a rotation of the module, it results in a longitudinal positional difference of Cell2Ds at different transverse positions in the same layer. This results in a time difference for the particles to reach different Seed2Ds on the same layer. Hence, it is necessary to compensate for this time difference based on the longitudinal position difference of Seed2Ds as follows:

After obtaining the corrected position and time information of Cluster2Ds, the time and position information of Cluster3Ds are obtained by weighting the time or position information of Cluster2Ds as follows:

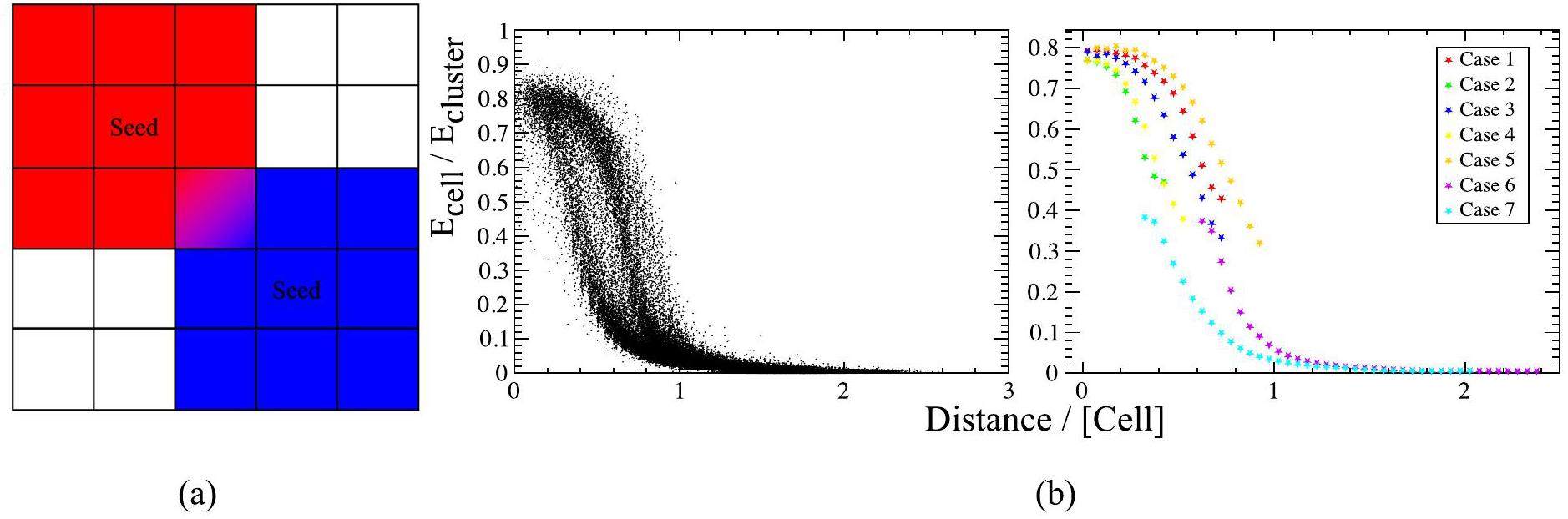

Splitting of overlapping clusters

When two Cluster3Ds overlap in an event, as shown in Fig. 4a, it is necessary to conduct energy splitting on the shared Cell2Ds to ensure accurate reconstruction of the energy and position of the Cluster3Ds. In the layered reconstruction framework, energy splitting of the overlapping Cluster3Ds is performed at the Cluster2D level. The general logic of the algorithm is as follows. First, determine if the two Cluster3Ds share any Cell2Ds. If they do, distribute the energy of the shared Cell2Ds between the respective Cluster2Ds. Upon completing the energy splitting of Cell2Ds, reevaluate the information of Cluster2Ds based on the updated energy of Cell2Ds, and remake the necessary corrections.

Currently, the energy splitting is determined by the transverse shower profile obtained from MC truth information. This study provides a layered description of the transverse shower profile at the Cell2D level. As shown in Fig. 4b, the transverse shower profile is represented by the distance of Cell2Ds from Cluster2Ds on the x-axis and the energy fraction of Cell2Ds relative to Cluster2Ds on the y-axis.

When Cell2D is shared by two Cluster2Ds, the distribution of Cell2D energy to each Cluster2D is evaluated in two steps. First, the energy fraction of the shared Cell2D corresponding to each Cluster2D is calculated based on the distance between Cell2D and Cluster2D, as depicted in Fig. 4b. Second, the estimated energy from each of the two Cluster2Ds to Cell2D is computed using the fraction established in the first step and the energy of the Cluster2Ds. At this juncture, the total estimated energy from the two Cluster2Ds to the shared Cell2D exceeds that of the shared Cell2D. The energy of the shared Cell2D is then distributed between the two Cluster2Ds, using the calculated estimated energy as the weighting factor. Subsequently, the energy and position of Cluster2D are recalculated, and the aforementioned procedures are repeated. Upon stabilizing the splitting weights of the shared Cell2D for the two Cluster2Ds, this iterative process completes and finalizes the energy splitting of the shared Cell2D.

The precision of the energy fraction contributed by Cell2D to each Cluster2D relies heavily on the accuracy of the transverse shower profile. As depicted in Fig. 4b, even when the distances between Cell2Ds and their respective Cluster2Ds are identical, the energy contribution from Cell2Ds to Cluster2Ds can vary significantly and even display multiple peaks, particularly at distances of approximately 0.5 [Cell]. Therefore, it is essential to categorize the data points in the left-hand plot in Fig. 4b to achieve narrower fraction ranges corresponding to the same distance within a single category, as well as a singular peak in the energy fraction.

The classification methods used in this study are listed in Table 1 and the classification results are shown in the right plot of Fig. 4b. First, whether this Cell2D is a Seed2D should be determined. This is because the random scattering direction of the initial electron pairs affects which Cell2D near the hit point has the opportunity to receive more energy. A Cell2D deposited with the maximum energy was constructed as a Seed2D in the reconstruction process. Additionally, because the readout unit (Cell2D) is not circular, the position of the hit point relative to the edges or corners of Seed2D affects the energy fraction of Seed2D when the distance to the hit point remains unchanged. Finally, the position of the hit point and the Cell2Ds relative to Seed2D in the positive or negative direction of the particle’s transverse momentum also affect the energy fraction, which can be described as being relatively close to or far from the beam pipe in LHCb. In practical operations, the hit position of the particles in each layer is substituted by the position of Cluster2Ds.

| Case | Cell type | Hit position relative to Seed | Cell relative to Seed |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Seed | 1: In the positive direction of pT; 2: Near the edges of the Seed | / |

| 2 | Seed | 1: In the negative direction of pT; 2: Near the edges of the Seed | / |

| 3 | Seed | 1: In the positive direction of pT; 2: Near the corner of the Seed | / |

| 4 | Seed | 1: In the negative direction of pT; 2: Near the corner of the Seed | / |

| 5 | Seed | Near the corner closest to the direction of pT of the Seed | / |

| 6 | Cell | / | In the positive direction of pT |

| 7 | Cell | / | In the negative direction of pT |

Merged π0 reconstruction

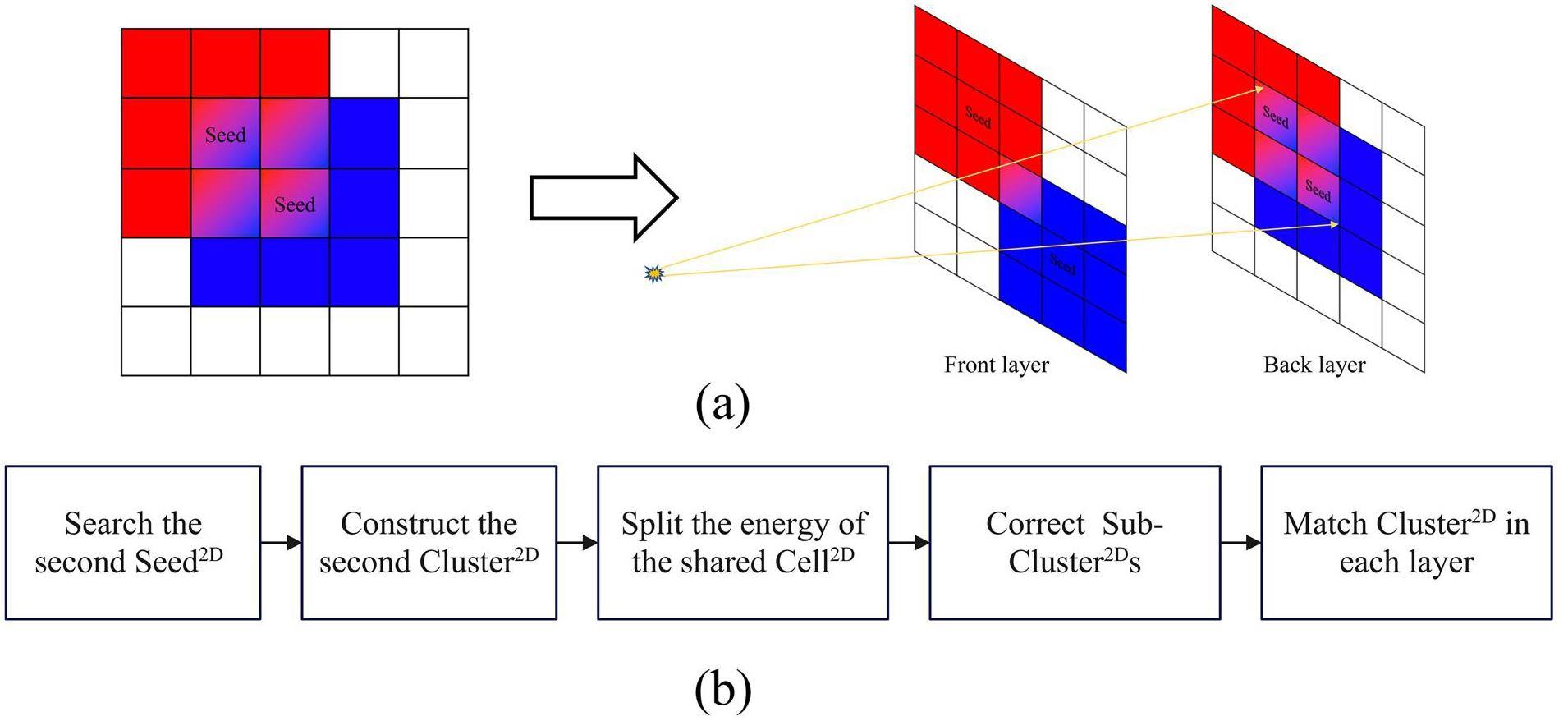

When two photons produced by π0 cannot be reconstructed individually as two Cluster3Ds because of the proximity of the hit points, π0 is referred to as merged π0. This section describes the reconstruction of the potential sub-Cluster3D pair, which is considered a candidate for the photon pair from the merged π0, from a direct reconstruction of Cluster3D. Subsequently, the sub-Cluster3D pair is used to reconstruct the merged π0. A workflow chart of the merged π0 reconstruction is presented in Fig. 5b. The following subsection focuses on the algorithms associated with the first and last steps in the workflow chart, which do not appear in single-photon reconstruction.

Searching the second Seed2D in Cluster2Ds

During the reconstruction process, a merged π0 indicates that the generated photon pair was reconstructed as one Cluster3D in ECAL. This indicates that energy deposition from π0 produces only one local maximum energy Cell3D. For the unlayered-reconstruction framework in some experiments [37, 38] where layered readout information is lacking, it is common practice to select one of the non-seeded cells in the cluster with the highest energy cell as the second seed. A new cluster is then constructed around the second seed as the center. After splitting the energy of the shared cells between the new and original clusters, the overlapping clusters are referred to as subcluster pairs of the original cluster.

As shown in Fig. 5a, a merged π0 does not necessarily result in "merged" Cluster2D in each layer. According to the cell-energy-splitting algorithm described above, the success rate of splitting increased as the number of cells shared by the two clusters decreased.

Furthermore, it is necessary to base the selection of the second Seed2D on the energy of Cell2Ds. This is because the energy of Cell2Ds are also related to the distance from the hit point of the photon. When one of the photons resulting from the decay of a π0 has a much higher energy than the other photon in non-Seed2D Cell2Ds, the Cell2D closer to the higher-energy photon may have a higher energy than the Cell2D closest to the lower-energy photon. Solely focusing on the energy of Cell2D may result in misidentifying the second Seed2D.

Hence, motivated by the aforementioned reasons, the layered reconstruction framework described in this study involves a two-step process for identifying the second Seed2D to enhance the accuracy of splitting Cluster2D and ultimately improve the efficiency of π0 reconstruction.

The first step is to search for Cell2D, except for Seed2D, which has the highest energy E’ in Cluster2D as Cell2D’. The definition of E’ is given by the following equation:

Cluster2D matching

After completing the preliminary algorithm, a sub-Cluster2D pair was obtained for each layer. The algorithm described in this section aims to match the sub-Cluster2Ds in different layers and finally obtain two sub-Cluster3Ds. The subCluster3D pair is regarded as a photon generated by the merged π0. The matching of Cluster2D on different layers directly affects the accuracy of the reconstruction of the final sub-Cluster3D. The utilization of multidimensional information from different readout layers facilitates a more accurate Cluster2D matching.

First, the energy of the sub-Cluster2Ds in each layer was used for prematching. Because the ratio of the deposition energy in each layer is related to the energy of the incident particles[25], unreasonable matches can be filtered based on the energy ratios between Cluster2Ds and the energy of Cluster3D as shown in Fig. 2b. For example, in the case of a dual-layer ECAL, the energy of the Cluster2Ds in the front layer is used to calculate the energy of the Cluster2Ds in the other layers, and if the energy of the Cluster2Ds in the other layers exceeds the calculated value by

If there is more than one Cluster2D in a certain layer that is prematched with the front layer, the final match is made based on the positional relationship. First, Cluster2D in the front layer is connected to the initial vertex (typically, the zero point). The connection line is extended and projected onto these layers, and the closest pre-matched Cluster2Ds to the projection point are matched with the front layer Cluster2D to complete the matching and obtain sub-Cluster3D.

Finally, to avoid the resolution of π0 being reconstructed in a merged model, Seed2Ds in all layers of sub-Cluster3D must be checked to determine whether they are included in the direct reconstruction Cluster3D. If so, the current process of the merged π0 reconstruction is terminated, and a new process starts by skipping the next directly reconstructed Cluster3D.

Performance

In the context of the LHCb experiment, a Phase- slowromancap 2@ upgrade (LHCb Upgrade slowromancap 2@) was proposed[39]. Scheduled for installation at the beginning of LHC Run 5 around 2036, the LHCb Upgrade slowromancap 2@ aims to enhance the experimental capabilities for exploring the frontiers of particle physics. PicoCal was designed with a longitudinally layered ECAL structure. The Shashlik calorimeter structure [41, 40] was retained in the outer region of PicoCal, whereas the Spaghetti calorimeter (SpaCal) [42, 43] was used in the central region. The GAGG crystal, which is known for its high radiation resistance, high light yield, and excellent time-response performance [44-49], was introduced as a sensitive material in the most central region with the highest radiation dose. Reduced detector occupancy can be achieved by designing and using modules with smaller Molière radii to achieve smaller readout cell sizes in the internal regions with the highest detector occupancies. The detailed layout is presented in Table 2.

| Region | Type | Absorber/Crystal | Cell size (cm2) | RM (mm) | Layers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shashlik | Lead/Polystyrene | 12×12 | 35.0 | 2 |

| 2 | Shashlik | Lead/Polystyrene | 6×6 | 35.0 | 2 |

| 3 | Shashlik | Lead/Polystyrene | 4×4 | 35.0 | 2 |

| 4-7 | SpaCal | Lead/Polystyrene | 3×3 | 29.5 | 2 |

| 8-11 | SpaCal | Tungsten/GAGG | 1.5×1.5 | 14.5 | 2 |

In this section, based on the above layout, a series of single-photon and π0 samples are used to demonstrate the performance of the layer-reconstruction algorithm in this framework. In addition, the unlayered-reconstruction algorithm [35] employed in Run 1/2 of LHCb was introduced for comparison. To ensure fairness, the unlayered-reconstruction algorithm remained consistent with the layered reconstruction algorithm in terms of cluster correction, overlapping cluster splitting, and other steps, except for the utilization of layered information.

Single-photon performance

The single-photon samples utilized in this section were generated and simulated using the "Hybrid MC" simulation framework [50], which is built upon the GEANT4 Monte Carlo package [51]. The performance of the layered reconstruction algorithm in this framework was demonstrated in terms of the energy, position, and time resolution.

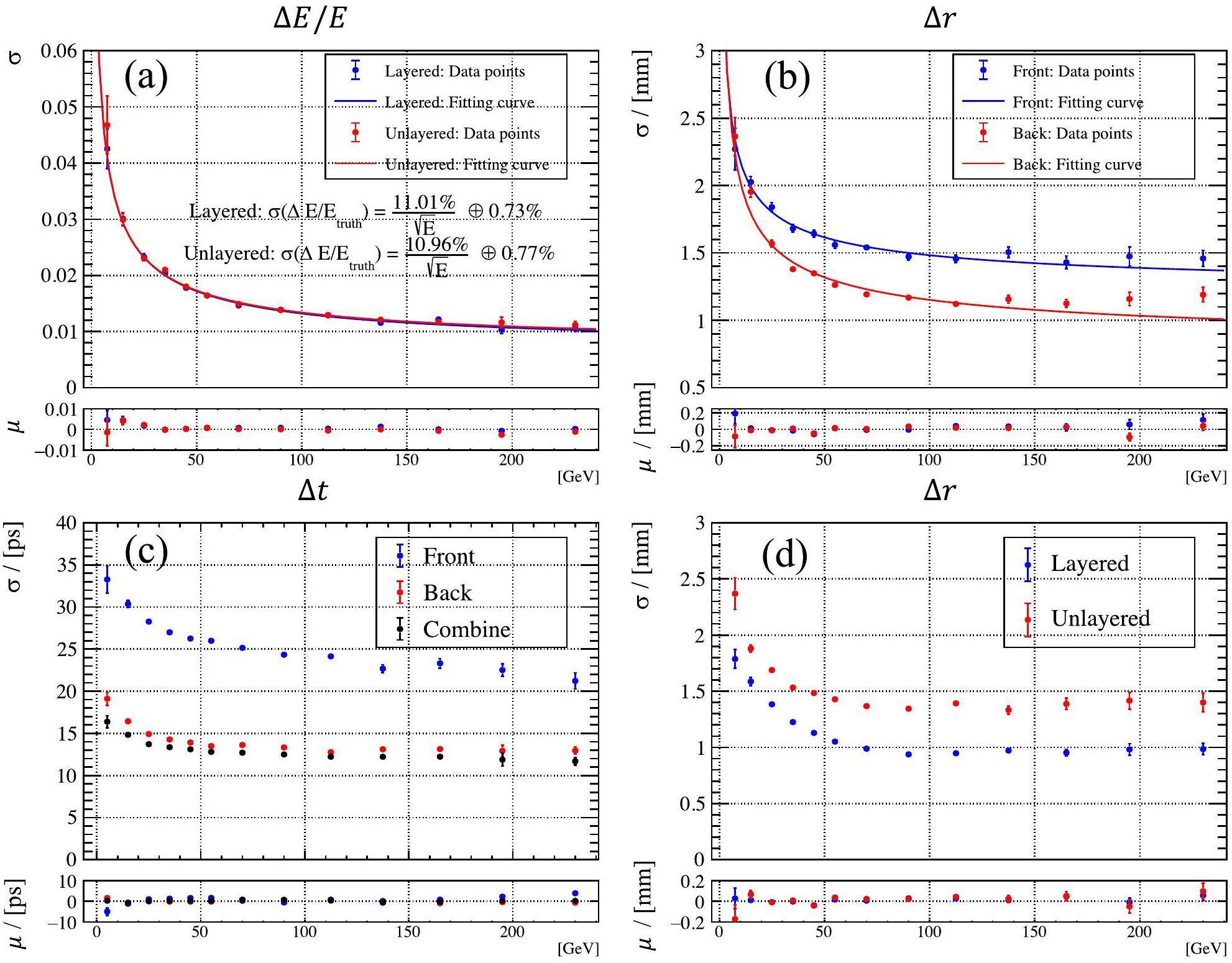

Energy resolution

The Fig. 6a illustrates the energy resolution versus the incident energy. This relationship can be described by the following equation:

Position resolution

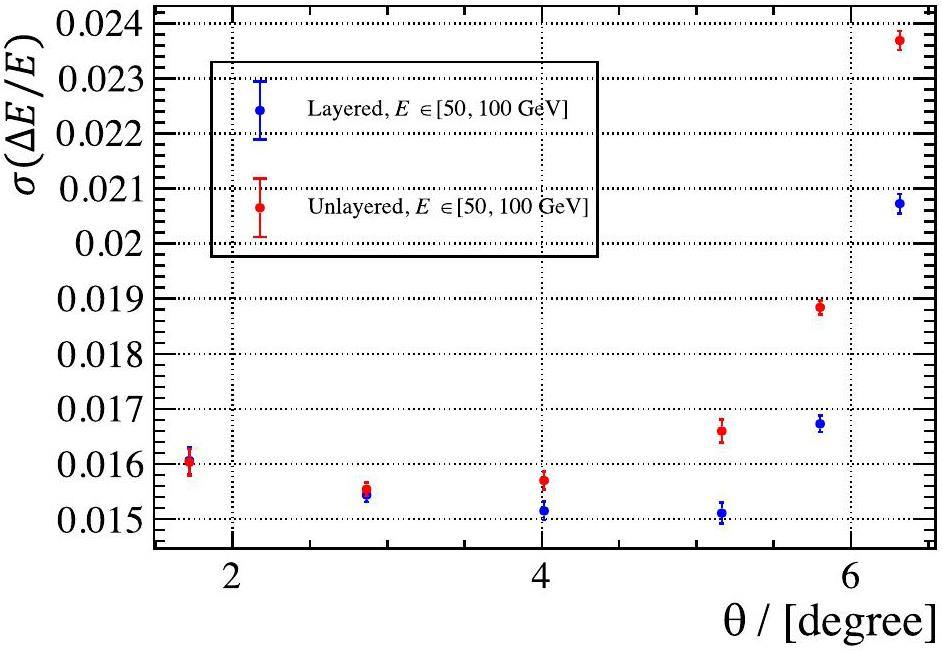

The position resolution is a critical parameter of the ECAL and is, to some extent, equivalent to the angular resolution. The positional resolutions are shown in Fig. 6b and d, respectively, where Front and Back represent the front and back layers, respectively, r represents the position. The development stages of the shower and readout layers change as the particles undergo showering and deposit energy along their momentum direction. However, the tendency of the reconstructed Cluster2D’s raw position, relative to the true position, varied between the different layers. Essentially, if we only have the energy-weighted position information of Cell2Ds located in different layers, the raw position will spread out in the transverse plane owing to different tendencies. Consequently, utilizing an unlayered-reconstruction algorithm and an overall correction parameter for reconstructing the transverse position will lead to degradation of the position resolution owing to this spreading effect. In contrast, the reconstruction in this study effectively resolved the previously mentioned issue and improved the positional resolution, as illustrated in Fig. 6d. This enhancement results in an improvement of approximately 0.5 mm in the high-energy region, representing a 33% increase compared with the unlayered-reconstruction algorithm.

Time resolution

Time is essential for event reconstruction and data analysis in high-luminosity environments. Within the layered reconstruction framework, time information can be provided in the form of Cluster3D or along the longitudinal direction using Cluster2D, as shown in Fig. 6c. The integration of layered time information provides new analytical perspectives for future physical investigations. Ongoing research also focuses on exploring the application of time information for reconstruction, correction, and analysis.

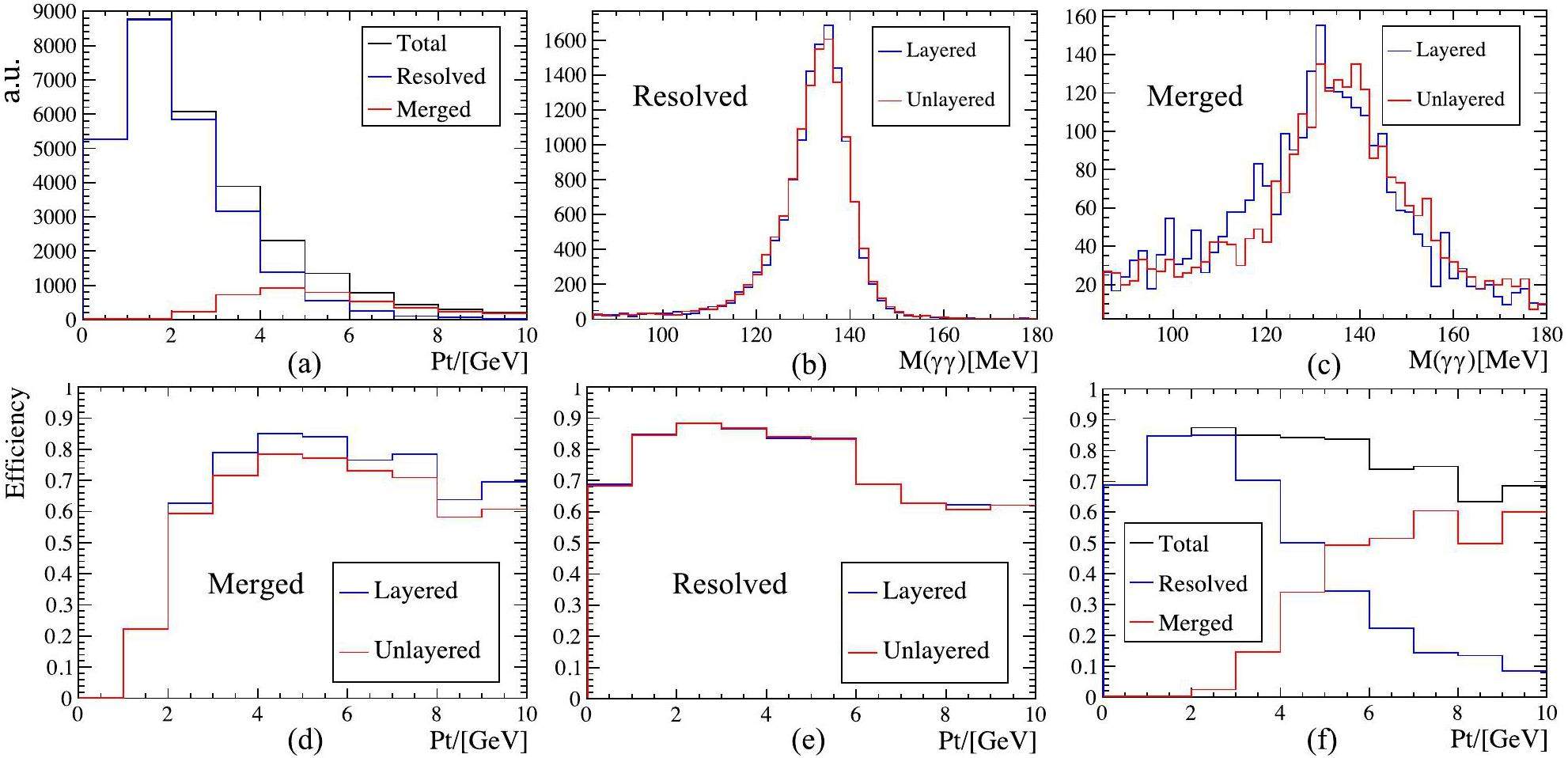

π0 reconstruction performance

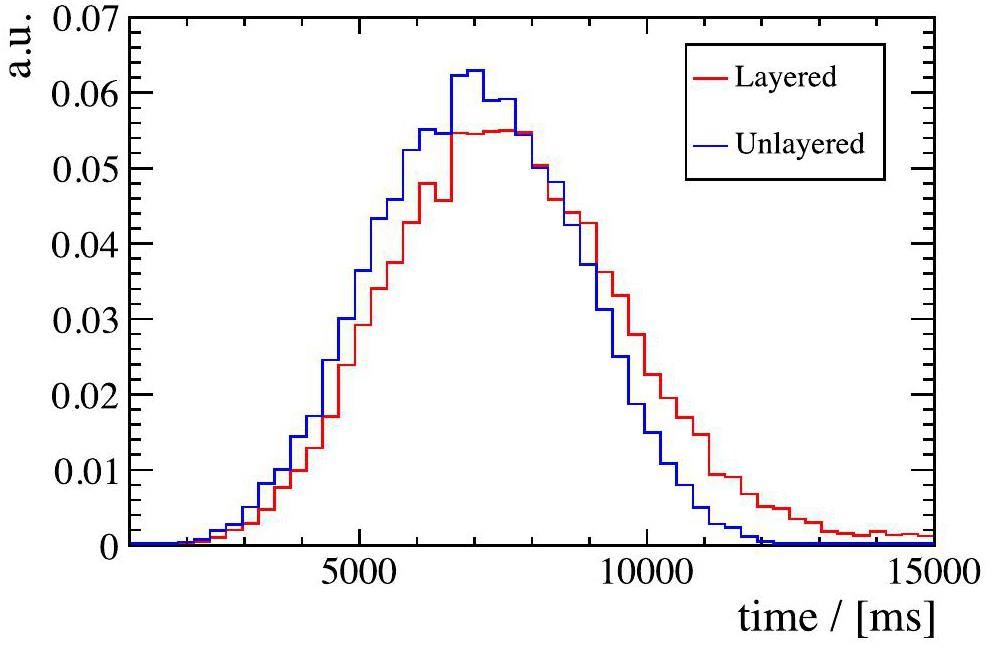

In this section, approximately 30,000 signal π0 events from

As shown in Fig. 8d, as expected, utilizing the layered reconstruction algorithm in this framework improves the ability to split overlapping Cluster3D s, leading to a 10% increase in the efficiency of reconstructing the merged π0. The improvement in the position resolution of a single-photon contributes to the improvement in the resolution of π0 mass distribution, as shown in Fig. 8b and c.

Computation

This framework allows task splitting according to events, thereby enabling the deployment of different events as separate tasks. Based on this framework, we evaluated the runtime of Cluster3D reconstruction under LHCb PicoCal at a center-of-mass energy of 14 TeV and an instantaneous luminosity of 1.5×1034 cm-2s-1. The framework was deployed on a cluster CPU with an

Scalability is a critical consideration for CPU cluster design. In this framework, an event is defined as the smallest unit of a cluster task. This approach facilitated efficient task management and resource allocation. By increasing the number of computing nodes, the number of events processed in parallel can be increased, thereby reducing the overall task runtime. The computational speed of event reconstruction can be enhanced by using more powerful CPUs in each computing node.

The time complexity of each step in the reconstruction process for each event is shown in the flowchart in Fig. 2, and are listed in Table 3. Here, n1 represents the number of Cell2Ds, n2 represents the number of Cell3Ds, n3 represents the number of Seed3Ds, and n4 represents the number of Cluster3Ds. Considering the parallelism within an event, the structure of these processes in this framework was designed for future deployment on nodes with parallel computing capabilities, such as GPUs or FPGAs. This establishes a solid foundation for the future deployment and acceleration of these algorithms in GPU clusters and FPGA platforms.

| Algorithm | Time complexity |

|---|---|

| Construct Cell3Ds | O(n1) |

| Search Seed3Ds | O(n2) |

| Construct Cluster3Ds | O(n3) |

| Split overlapping Cluster3Ds | |

| Search Seed2Ds/Construct Cluster2Ds | O(n4) |

| Correct Cluster3Ds | O(n4) |

Conclusion

As depicted in Fig. 1, this work has accomplished we developed a software framework for the longitudinally segmented ECAL event reconstruction. Moreover, a layered reconstruction algorithm was devised within this framework for Cluster3Ds and the merged π0. This framework not only furnishes the general direction, arrival time, and energy of the particle candidates in the Cluster3D format, but also provides the position, timestamp, and energy deposition in each layer in the Cluster2D format. The information from the Cluster2Ds can not only be used to filter out unreasonable Cluster3Ds during reconstruction, but also to provide new perspectives in physics analysis.

To achieve a more refined correction of the Cluster3D information, this study leveraged the advantages of a layered reconstruction framework to provide layered information and designed a layered correction method and process. In terms of energy correction, compared with solely using the Cluster3D energy for correction, this study further utilized the energy ratios of Cluster2D in each layer for correction, aiming to better compensate for the longitudinal variation in the sampling fraction of the ECAL. To correct the time and position information, we first corrected the corresponding information of the Cluster2Ds and then weighted the corrected Cluster2D information based on the resolution of the corresponding information in each layer. The weighted result was used as the corrected information for Cluster3D. Moreover, this study delves into the transverse shower profile and systematically elucidates the relationship between the distance and energy ratio between Cell2D s and Cluster2D. This information provides more precise prior knowledge for splitting overlapping Cluster3Ds.

Finally, the performance of the framework was validated using the PicoCal in LHCb Upgrade slowromancap 2@. The results show that the layered reconstruction algorithm in this framework significantly improves the position resolution of a single photon, and the energy resolution of the particles at large incident angles compared with the unlayered-reconstruction algorithm. For example, in regions 4-7 of the specified setup, the position resolution was enhanced from approximately 1.4 mm to 0.9 mm in the high-energy region. In addition, the energy resolution was improved by approximately 10% at large incident angles. Furthermore, the layered reconstruction algorithm enhances the splitting capability of overlapping clusters, leading to further improvements in the efficiency of merged π0 reconstruction. The current version of the algorithm can increase the reconstruction efficiency of the merged π0 by approximately 10% for SpaCal in the aforementioned setup.

Furthermore, this study provided a suitable software platform for future studies on layered ECAL. It incorporates comprehensive data structures and application programming interfaces (APIs), along with straightforward configuration and execution. This feature allows convenient secondary development by leveraging the framework to substitute and validate new algorithms. This also facilitates the investigation of ECAL-related physics. In future work, we will continue to explore various facets by utilizing the multidimensional information and scalability provided by the proposed software framework. This includes delving into the application of deep learning in cluster splitting and information correction, evaluating the performance of different cluster shapes, and scrutinizing the application of time information in cluster reconstruction.

Production and test of sPHENIX W/SciFiber electromagnetic calorimeter blocks in China

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 145 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01517-yDesign and prototyping of the readout electronics for the transition radiation detector in the high energy cosmic radiation detection facility

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 82 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01446-wPerformance of the electromagnetic calorimeter module in the NICA-MPD based on Geant4

. Nuclear Techniques (in Chinese) 46,Performance of the ALICE Electromagnetic Calorimeter

. JINST. 18,LHCb Particle Identification Enhancement Technical Design Report. CERN, Technical Report No. CERN-LHCC-2023-005, LHCB-TDR-024, Geneva

(2023). https://doi.org/10.17181/CERN.LAZM.F5OH. https://cds.cern.ch/record/2866493Direct photon production at LHCb

. Nucl. Phys. A 982, 251-254 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2018.10.046. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0375947418303270LHCb Detector Performance

. Inter. J. Modern Phys. A 30,Calibration and performance of the LHCb calorimeters in Run 1 and 2 at the LHC. 2020, Report Number: LHCb-DP-2020-001

. https://cds.cern.ch/record/2729028Observation of Photon Polarization in the b→sγ Transition

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112(16),First experimental study of photon polarization in radiative Bs0 decays

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118,Measurement of CP Violation in the Decay B+→K+π0

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126,Search for time-dependent CP violation in D0→π+π−π0 decays

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133,Test of Lepton Universality with B0→K*0l+l− Decays

. J. High Energ. Phys. 2017, 55 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP08(2017)055Test of lepton universality in b→sl+l− decays

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131,Search for the Bs0→μ+μ−γ decay

. JHEP 2407, 101 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP07(2024)101Expression of Interest for a Phase-II LHCb Upgrade: Opportunities in flavour physics, and beyond, in the HL-LHC era. CERN Technical Report, CERN-LHCC-2017-003, Geneva

(2017). https://cds.cern.ch/record/2244311Framework TDR for the LHCb Upgrade II: Opportunities in flavour physics, and beyond, in the HL-LHC era. CERN, Technical Report No. CERN-LHCC-2021-012, LHCB-TDR-023, Geneva

(2021). https://cds.cern.ch/record/2776420Physics case for an LHCb Upgrade II - Opportunities in flavour physics, and beyond, in the HL-LHC era. CERN, Technical Report No. LHCB-PUB-2018-009, CERN-LHCC-2018-027, LHCC-G-171, Geneva

(2016). https://doi.org/10.17181/CERN.QZRZ.R4S6. https://cds.cern.ch/record/2636441LHCb Upgrades and operation at 1034 cm-2s-1 luminosity – A first study

. (2018). https://cds.cern.ch/record/2319258Physics program and performance of the ALICE Forward Calorimeter upgrade (FoCal)

.Upgrade of the CMS Barrel Electromagnetic Calorimeter for the LHC Phase-2. CERN, report number CMS-CR-2024-133, Geneva

(2024). https://cds.cern.ch/record/2908787Technical Design Report: A High-Granularity Timing Detector for the ATLAS Phase-II Upgrade. CERN, ATLAS-TDR-031. Geneva

(2020). https://cds.cern.ch/record/2719855Properties of QCD matter: a review of selected results from ALICE experiment

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 219 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01583-2Properties of the QCD matter: review of selected results from the relativistic heavy ion collider beam energy scan (RHIC BES) program

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 214 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01591-2Performance of electron reconstruction and selection with the CMS detector in proton-proton collisions at s=8 TeV

. JINST 10,Electron and photon reconstruction and identification with the CMS experiment at the CERN LHC

. JINST 16,Performance of photon reconstruction and identification with the CMS detector in proton-proton collisions at s=8 TeV

. JINST 10,Simulation studies of π0, η and ω meson reconstruction performance in pp collisions at s=14 TeV in Forward Calorimeter(FoCal)

. Indian Inst. Tech. Indore, 2023. https://cds.cern.ch/record/2860262CLUE: a fast parallel clustering algorithm for high granularity calorimeters in high-energy physics

. Front. Big Data. 3,The iterative clustering framework for the CMS HGCAL reconstruction

. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2438,LHCb ECAL upgrade II

. PoS PANIC2021, 100 (2022). https://doi.org/10.22323/1.380.0100. https://cds.cern.ch/record/2836693.LHCb Upgrade II Scoping Document. CERN. CERN-LHCC-2024-010, LHCB-TDR-026. Geneva

. 2024. https://cds.cern.ch/record/2903094A clustering algorithm for the LHCb electromagnetic calorimeter using a cellular automaton. CERN. LHCb-2001-123. Geneva

(2001). https://cds.cern.ch/record/681262Photon and neutral pion reconstruction. CERN-LHCb-2003-091

(2003).B0→π+π−π0 reconstruction with the re-optimized LHCb detector. CERN, Technical Report No. LHCb-2003-077, Geneva

(2003). https://cds.cern.ch/record/691636Particle identification with LHCb calorimeters

. CERN (2003). https://cds.cern.ch/record/691743The LHCb Detector at the LHC

. Journal of Instrumentation 3,Design and construction of electromagnetic calorimeter for LHCb experiment. CERN Technical Report, LHCb-2000-043, Geneva

(2000). https://cds.cern.ch/record/691508LHCb calorimeters: Technical Design Report. CERN, Technical Design Report. LHCb, Geneva

(2000). https://cds.cern.ch/record/494264The high resolution spaghetti hadron calorimeter: proposal. CERN Technical Report, NIKHEF-H-87-7, Geneva

(1987). https://cds.cern.ch/record/181281Performance of a spaghetti calorimeter prototype with tungsten absorber and garnet crystal fibres

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 1045,Irradiation studies of a multi-doped Gd3Al2Ga3O12 scintillator

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 916, 226-229 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2018.11.101Composition Engineering in Cerium-Doped (Lu, Gd)3(Ga,Al)5O12 Single-Crystal Scintillators

. Cryst. Growth Des. 11, 4484-4490 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1021/cg200694a.Defect engineering in Ce-doped aluminum garnet single crystal scintillators

. Cryst. Growth Des. 14, 4827-4833 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1021/cg501005s. https://doi.org/10.1021/cg501005sEffect of Mg2+ ions co-doping on timing performance and radiation tolerance of Cerium doped Gd3Al2Ga3O12 crystals

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. Sect. A 816, 176-183 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2016.02.004Scintillation properties and timing performance of state-of-the-art Gd3Al2Ga3O12 single crystals

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. Sect. A. 1000,Radiation tolerance of LuAG:Ce and YAG:Ce crystals under high levels of gamma- and proton-irradiation

. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 63, 586-590 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1109/TNS.2015.2493347Hybrid-MC

. (2024). https://gitlab.cern.ch/spacal-rd/spacal-simulationGeant4—a simulation toolkit

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. Sect. A 506(3), 250-303 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(03)01368-8The LHCb simulation application, Gauss: design, evolution and experience

. J. Phys. 331,The authors declare that they have no competing interests.