Introduction

Clustering is a universal phenomenon observed in various systems, ranging from clusters of galaxies to clusters of nuclei [1-3]. In nuclear physics, clustering is one of the most important features in light nuclei [4-9]. Since the development of the α cluster model, light nuclei have been studied from the perspective of cluster features for more than half a century [10-14]. Various nuclear theories have been proposed to investigate nuclear clustering [15-19]. The three traditional nuclear cluster models are the Resonance Group Method (RGM) [20-22], Generator Coordinate Method (GCM) [23-26], and Orthogonality Condition Model (OCM) [27]. Some developed models, such as the Antisymmetrized Molecular Dynamics (AMD) model [28-30] and the Tohsaki-Horiuchi-Schuck-Röpke (THSR) model [31], have also been introduced in recent years.

The Generator Coordinate Method (GCM) was first introduced by Hill and Wheeler [23] in 1953 in the context of nuclear fission. Subsequently, Griffin and Wheeler extended this method o a general many-body tool [24]. The principle of the GCM is to express nuclear state wave functions as superpositions of non-orthogonal basis functions such as Slater determinants [32]. Because of the flexibility in selecting the basis functions or generator coordinates, GCM offers a general method for addressing many-body problems in nuclear cluster physics and other fields [33-37].

The GCM requires the superposition of different types of basis wave functions, thereby demonstrating their flexibility. However, selecting basis states is a crucial issue in some cases. The choice of collective coordinates often relies on empirical and phenomenological methods, which increase the complexity and computational time for many-body cluster systems. This issue is especially pronounced when applying the GCM to the structure of halo nuclei such as 6He, a well-known Borromean nucleus. It comprises a loosely bound and spatially extended three-body system, typically including the α core surrounded by two weakly bound neutrons α +n+n [38-40]. Using more efficient basis states in the GCM to describe such three-body gas-like systems accurately is an important issue [41].

In recent years, there have been many theoretical studies [42-44] exploring how to select effective basis states for the GCM. For example, Suzuki and Varga introduced stochastic sampling in the few-body model [45]; Suhara and Kanada-En’yo have proposed the β-γ constrained selection of Slater determinants in nuclear cluster model [46]; Additionally, Fukuoka et al. developed the imaginary-time evolution method in the mean-field model [47]; And Takatoshi et al. refined the Bloch-Brink α cluster model with the stochastic sampling method [48]. Owing to the powerful data processing capabilities of machine learning algorithms (ML), they have been widely employed in addressing different nuclear physics issues, including nuclear mass systematics [49-51], radii prediction [52], decay descriptions [53], many-body problems [54, 55], and nuclear structure [56]. It has attempted to identify hidden laws from a large amount of historical data and use them for prediction or classification.

In this study, by choosing the di-neutron halo nucleus of 6He (α + n + n) and the proton-neutron halo of 6Li (α + n + p) systems [57], we studied the effective basis problems in GCM, using global optimization and local gradient descent methods. First, the empirical law of the effective basis wave function distribution was summarized by comparing various random distributions. Subsequently, the Adam method [58] was used to provide a better standard of basis wave functions.

This paper is organized in the following way. Section 2 briefly reviews the framework of the wave function and the Generator Coordinate Method. In Sect. 3, the numerical results of optimization and discussions are provided. Finally, a summary is provided in Sect. 4.

Theoretical framework

The general ansatz of the Generator Coordinate Method [24] can be expressed,

In nuclear cluster physics, the Brink wave function [59] is typically used as the basis wave function for GCM calculations. Taking 6He as an example, the Brink wave function with an α + n+ n cluster configuration can be written as

Within the GCM framework, the final wave function of 6He can be obtained by superposing various configurations of α +n+n.

The Hamiltonian for 6He and 6Li three-body systems can be written as:

For the spin-orbit interaction, the G3RS potential [64, 65] is adopted,

Results and discussion

In this section, we take the di-neutron halo nucleus 6He and proton-neutron halo nucleus 6Li as examples, each conceptualized as three-cluster structures α + n+ n and α + n+ p, respectively. First, we summarize empirical laws using random distribution methods from a global perspective. Subsequently, at the local level, the Adam algorithm from machine learning is introduced to optimize the generation coordinates using the gradient descent theory.

Searching for specific distributions leading to effective basis wave functions

In the GCM, the mesh points for the generator coordinates were not predetermined. Although it is theoretically feasible to obtain exact solutions by enumerating a large number of wave functions with different configurations, this approach is computationally impractical. Instead, we hypothesize that the effective basis wave functions may follow specific distributions. To test this hypothesis, we generated coordinate sets {R} using various random distributions and applied them to calculate the ground state energy of the di-neutron halo nucleus 6He. By analyzing the relationship between the number of superimposed basis wave functions and the resulting ground state energies, we aim to derive global empirical rules that can enhance the efficiency of the GCM.

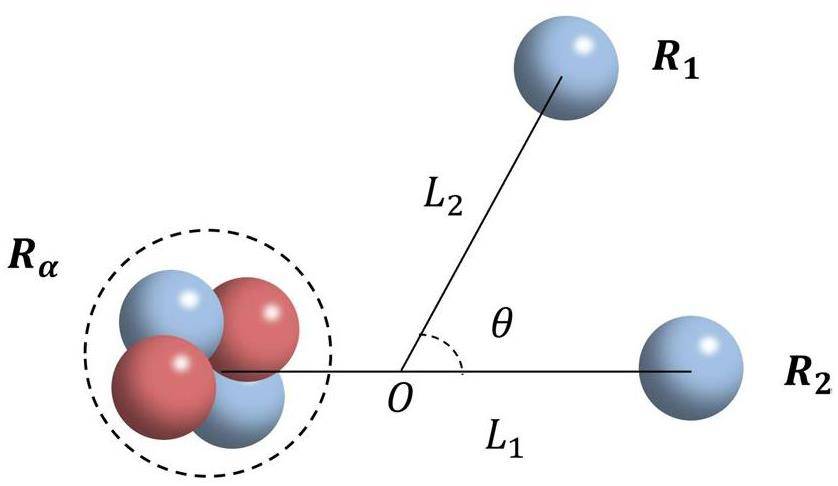

As a benchmark test, we first calculated the ground state of the di-neutron halo 6He nucleus using traditional mesh points for the Brink wave functions. As shown in Fig. 1, different sets of coordinates can be generated by adjusting the relative distances L1, L2, and angle θ relative to the x-axis. Where L1 is the distance between the α particle and neutron, and L2 is the distance between the other neutron and the center-of-mass of the α particle and neutron. Subsequently, various configurations with different sets (L1, L2, θ) were superposed. The mesh points for L1 were established at intervals of 0.35 fm, resulting in 14 points, whereas for L2, the intervals were set at 0.5 fm, accumulating 18 points. The values for angle

| Distribution model | Probability density function | Parameters | E (MeV) | Superposed basis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spherical shell | - | - | -28.212 | 704 |

| Traditional approach | - | - | -27.884 | 469 |

| Gamma distribution | -28.257 | 939 | ||

| Rayleigh distribution | σ=3.0 | -28.239 | 916 | |

| Exponential distribution | λ=0.5 | -28.229 | 764 | |

| Normal distribution | -28.245 | 957 | ||

| Logistic distribution | -28.260 | 946 |

Another common method for selecting mesh points is to distribute them within a spherical shell structure. The spherical structure of the latter is depicted as a three-dimensional, multi-layered spherical shell. The initial radius of the spherical shell was set at 1 fm, with spacing between adjacent layers at 1 fm, producing a total of five layers from the inside out. The Marsaglia algorithm [66] was employed to ensure a uniform distribution of points on each spherical shell. For each layer, 200 random three-dimensional coordinate values were generated. Following a procedure similar to the earlier one, the coordinates of the 1000 points generated are designated as

In addition to the above common methods, we also introduce other random distribution functions for generating mesh points, such as Gamma distribution, Uniform distribution, Chi-square distribution, Logistic distribution, and Normal distribution. Considering the halo feature of 6He, which is characterized by a diffuse density distribution around the nucleus, specific parameters for various random distribution functions have been selectively determined to assess their impact on the tail region. Although no quantitative relationships for parameter values under different distributions have been specified, we fortuitously discovered that the results remained relatively stable within a reasonable range of parameter values after experimenting with various settings. The probability density functions and specific parameter values for random distributions are listed in Table 1. Furthermore, GCM calculations are performed within the center-of-mass coordinate system; consequently, the results depend solely on the relative distances between the clusters. Thus, in the Normal and Logistic distributions, the results are influenced only by the standard deviation σ, independent of the mean μ. For computational convenience, μ is set to zero in these cases. Each random distribution is utilized to generate 1000 basis wave functions for the GCM calculations.

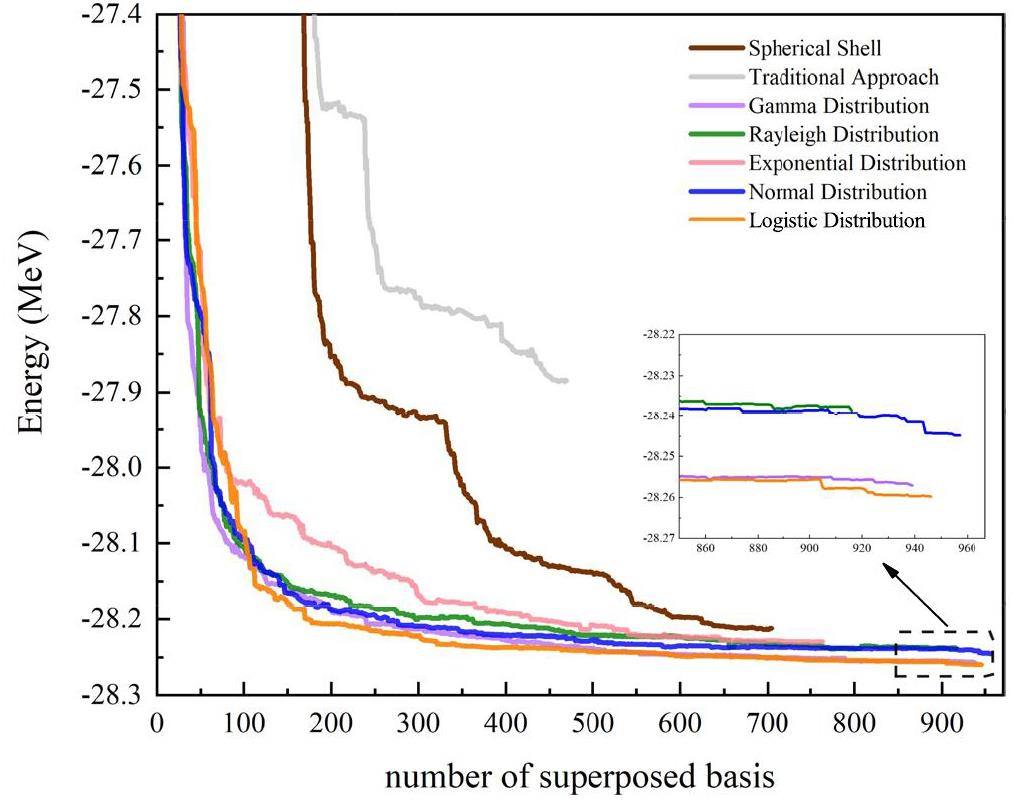

Figure 2 shows the energy convergence of the ground state using the various methods presented here to generate the basis wave functions. As one can see, the convergence rate of the energy variation curves corresponding to random distributions is significantly faster than that derived from manually configured structures. Table 1 provided qualitative insights. The ground state energies obtained using the traditional and spherical shell methods are -27.884 MeV and -28.212 MeV, respectively, both of which are obviously higher than those from all random distributions.

From Fig. 2 and Table 1, it is interesting to see that the Logistic distributions outperform other random distributions, with the 0+ state energies calculated at -28.260 MeV. Note that the Gamma distribution is also effective, although it is determined by two parameters (α,β), which provide a wider range of adjustments. Single-parameter Normal and Logistic distributions offer significant advantages for practical calculations. This superiority is attributed to the assumption of independence in the Normal distribution, which mirrors the relative spatial near independence of the clusters in the nuclei. Furthermore, the thicker asymptotic tails of the probability density function in the Normal distribution closely corresponded to the halo characteristics of 6He. Similarly, although the Logistic distribution resembles the Normal distribution, it features notably heavier tails. This characteristic better captures the extended features of the 6He halo nucleus structure, thereby encompassing a broader distribution of the effective basis states.

To substantiate this conclusion further, we compared the ground state energy by maintaining approximate equality between the standard deviations of the Logistic and Normal distributions according to the theoretical formula

| Distribution | Parameters | E(MeV) |

|---|---|---|

| Logistic distribution | γ=1.2 | -28.260 |

| γ=1.3 | -28.268 | |

| γ=1.4 | -28.262 | |

| γ=1.5 | -28.266 | |

| Normal distribution | σ=1.8 | -28.224 |

| σ=2.0 | -28.222 | |

| σ=2.3 | -28.245 | |

| σ=2.5 | -28.231 |

It is worth mentioning that the ground state (1+) of 6Li converges rapidly, requiring only a minimal number of basis wave functions. Calculations using various parameters for the Logistic and Normal distributions also quickly converged to approximately -30.02 MeV, indicating that there is no need for further optimization of the basis wave functions. Therefore, further discussion of the 6Li ground state is omitted in this work.

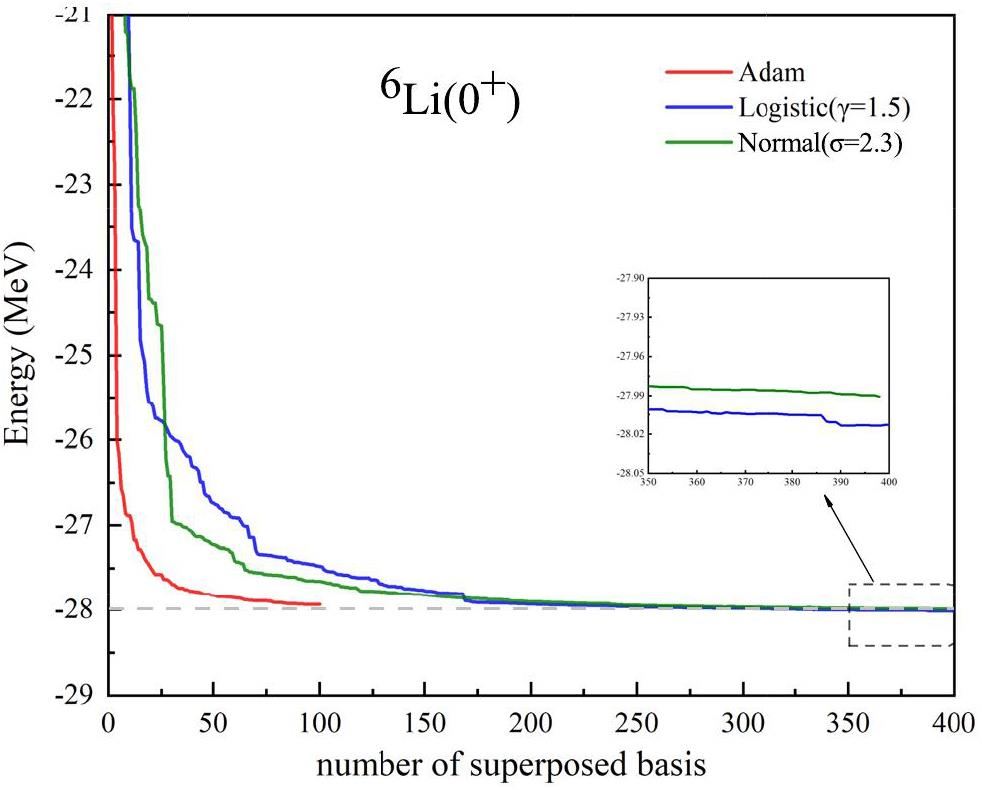

To confirm the aforementioned conclusions and ascertain the universality of the Logistic distribution in halo nuclear structures, we studied the excited states (0+) of 6Li and generated three sets of Logistic and Normal distributions under conditions of similar standard deviations for comparative analysis. Parameters for the Logistic distribution were set at γ = 1.0, 1.3, and 1.5, whereas those for the Normal distribution were set at σ = 1.8, 2.0, and 2.3. Considering the proton-neutron halo structure of 6Li, whose excited state energy converges more readily than the ground state energy of 6He, we generated 400 basis wave functions for each parameter set to perform the GCM calculations. The results are shown in Fig. 4 and Table 3. It is gratifying to observe that compared with the Normal distribution, the Logistic distribution still performs well in each group. According to the excitation energy of the 0+ state in Table 3, it can be observed that the Logistic distribution parameters γ are set at 1.0, 1.3, and 1.5, yielding convergence values of energy at -27.945 MeV, -27.999 MeV, and -28.013 MeV, respectively. These values slightly surpass those derived from the Normal distribution parameter σ set at 1.8, 2.0, and 2.3, which resulted in energy convergences of -27.933 MeV, -27.969 MeV, and -27.991 MeV. As shown in Fig. 4, the energy gradually converges as the number of basis wave functions increases, with the Logistic distribution exhibiting a slightly faster rate of convergence than the Normal distribution. These results indicate that the thick-tail characteristic of the Logistic distribution is not only suitable for calculating the ground state (0+) energy of 6He with a di-neutron halo, but also applicable to the excited state (0+) of 6Li with a proton-neutron halo. Furthermore, the Logistic distribution encompasses a broader range of effective basis wave functions, thereby providing crucial empirical insights for the subsequent selection of effective basis wave functions. It is important to analyze the underlying mechanisms behind this distribution.

| Distribution | Parameters | E (MeV) |

|---|---|---|

| Logistic distribution | γ=1.0 | -27.945 |

| γ=1.3 | -27.999 | |

| γ=1.5 | -28.013 | |

| Normal distribution | σ=1.8 | -27.933 |

| σ=2.0 | -27.969 | |

| σ=2.3 | -27.991 |

Adam optimization based on gradient descent principle

In GCM calculations, determining an appropriate distribution of optimized basis wave functions is of paramount importance for practical computations. However, studying the optimal basis wave functions mathematically at a local level is indispensable.

As shown in Eq. (3), the eigen energy E can be considered as a multivariable function with a set of {R} as its independent variables. Thus, solving for the energy using the variational principle is analogous to finding the minimum of a multivariable function

We used the Adam algorithm for gradient descent [58]. The Adam algorithm was chosen for its efficiency in optimizing the basis wave functions, particularly for handling complex and flat energy surfaces. By adapting learning rates and leveraging historical gradients, Adam outperformed traditional methods, reducing computational costs and improving the convergence speed. This makes it well-suited for challenging calculations, such as those involving halo nuclei.

Given the gradual slowing of energy convergence with increasing number of basis wave functions, distinct treatments were applied to the initial and terminal functions. In the early superposition phase, owing to the rapid decrease in energy, the Adam algorithm’s learning rate α was set at 0.3 with a maximum iteration count of 12 and an allowance for four oscillations to prevent missing minimal value points. When the fifth wave function was reached, as the rate of energy decline slowed, the learning rate was adjusted to 0.7 with the maximum iterations increasing to 40, and oscillations allowed up to eight to minimize time consumption.

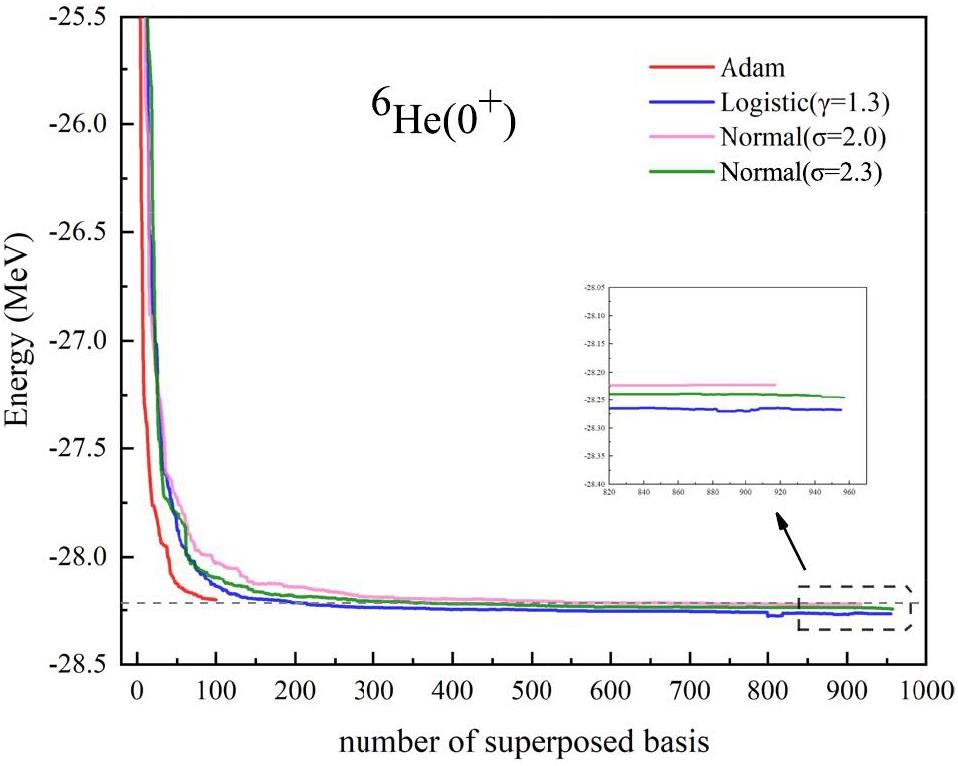

Although Sect. 3.1 shows the Logistic distribution outperforming Normal distributions and other models, we used the Normal distribution with σ = 2.3 to generate 100 initial coordinates {R} for a clearer comparative analysis. The optimization results for the ground state (0+) of 6He, as shown in Fig. 3. Compared to -28.064 MeV with unoptimized basis wave functions, the energy significantly decreases to -28.203 MeV after Adam optimization. Even compared to the well-performing Normal distribution, the superposition of 100 optimized basis wave functions through the Adam method equates to the effects of adding 200 or even 500 basis wave functions in the Normal distribution. This outcome not only confirms the feasibility and effectiveness of gradient descent optimization using the Adam method but also demonstrates that a small number of basis wave functions can achieve the effects of superposing multiple wave functions, and that Adam optimization includes a large number of effective basis wave functions.

To further validate this conclusion, the Adam algorithm was applied to the calculation of the excited state (0+) energy of 6Li, and the results are depicted in Fig. 4. Compared to -27.656 MeV with non-optimized basis wave functions, the energy decreased significantly to -27.937 MeV after Adam optimization. Compared with other parameter settings in the Normal distribution, the superposition effect of 100 optimized basis wave functions is equivalent to adding 200-300 ones in the Normal distribution. This suggests that there is still room for improvement in determining better distributions for the mesh points in the GCM. It is worth noting that owing to the differing nuclear structures of various nuclei, the optimized basis functions derived by the Adam algorithm for one nucleus in principle cannot be directly applied to another.

Summary and outlook

To conclude, we investigated the effective basis wave function distributions for the di-neutron halo nucleus 6He and proton-neutron halo nucleus 6Li using the Generator Coordinate Method. From a global perspective, our comparative analysis of various random distributions against manually configured models revealed that the Normal distribution performed significantly better than the other distributions, except for the Logistic distribution. This superior performance is attributed to the independence assumption of the Normal distribution, which mirrors the relative spatial independence of the nuclei, and the heavy tail of its probability density function, which resembles the diffuse characteristics typical of halo nuclei. Interestingly, the Logistic distribution, with its probability density curve similar to that of the Normal distribution but with a more pronounced tail, not only retained the advantages of the Normal distribution but also more accurately represented halo nuclear structures. In both the ground state (0+) of 6He and the excited state (0+) of 6Li, the Logistic distribution yielded better results than the Normal distribution, suggesting that it encompasses a broader range of effective basis wave functions and reduces the number of necessary wave function overlays for halo structures.

Furthermore, from a local viewpoint, we analogized the optimization of basis wave functions to solve a multivariate extremum problem and employed the Adam algorithm to optimize 100 basis wave functions, achieving considerable outcomes. The results for both the ground state (0+) of 6He and the excited state (0+) of 6Li indicated that a few optimized basis wave functions could achieve the effects of multiple wave functions overlays, thus validating the feasibility and universality of the gradient descent method. This not only provides a benchmark for selecting effective basis wave functions but also makes a solid foundation for future applications of machine learning methods to comprehensively predict the coordinates of effective basis wave functions. Although the Adam algorithm currently requires extensive runtime due to computational constraints, future research will focus on optimizing it to enhance computational efficiency.

Microscopic clustering in light nuclei

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90,α-clustering effect on flows of direct photons in heavy-ion collisions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 66 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00897-9Physics of exotic nuclei

. Nat. Rev. Phys. 1-17 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42254-024-00782-5Giant dipole resonance as a fingerprint of α clustering configurations in 12C and 16O

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113,Alpha-clustering effects on 16O (γ, np) 14N in the quasi-deuteron region

. Euro. Phys. J. A 53, 119 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2017-12300-0Effects of α-clustering structure on nuclear reaction and relativistic heavy-ion collisions

. Nucl. Tech 46,Nuclear clustering in light neutron-rich nuclei

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 29, 184 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-018-0522-xNeutron clusters in nuclear systems

. Front. Phys 11,Microscopic calculations of 6He and 6Li with real-time evolution method

. Euro. Phys. J. A 58, 25 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-021-00648-9System dependence of away-side broadening and α-clustering light nuclei structure effect in dihadron azimuthal correlations

. Phys. Lett. B 831,Spectroscopic calculations of cluster nuclei above double shell closures with a new local potential

. Phys. Rev. C 87,Influence of α-clustering nuclear structure on the rotating collision system

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 29, 186 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-018-0523-9The reduced-width amplitude in nuclear cluster physics

. (2024). arXiv:2412.20928 https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.20928Breathing-like excited state of the hoyle state in 12C

. Phys. Rev. C 94,Global analysis of nuclear cluster structure from the elastic and inclusive electron scattering

. Phys. Rev. C 103,Nonlocalized clustering: A new concept in nuclear cluster structure physics

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110,Nonlocalized clustering and evolution of cluster structure in nuclei

. Frontiers of Physics 15, 1-64 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11467-019-0917-0Clustering and other exotic phenomena in nuclei

. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top 156, 69-92 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjst/e2008-00609-yOn the mathematical description of light nuclei by the method of resonating group structure

. Phys. Rev. 52, 1107-1122 (1937). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.52.1107Neutron-proton halo structure of the 3.563-mev 0+ state in 6Li

. Phys. Rev. C 51, 2488-2493 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.51.2488Di-trinucleon resonance states of a=6 systems in a microscopic cluster model

. Phys. Rev. C 74,Nuclear constitution and the interpretation of fission phenomena

. Phys. Rev. 89, 1102-1145 (1953). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.89.1102Collective motions in nuclei by the method of generator coordinates

. Phys. Rev. 108, 311-327 (1957). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.108.311Generator coordinate method with a conjugate momentum: Application to particle number projection

. Phys. Rev. C 103,Union of rotational and vibrational modes in generator-coordinate-type calculations, with application to neutrinoless double-β decay

. Phys. Rev. C 100,Interaction between Clusters and Pauli Principle

. Prog. Theor. Phys 41, 705-722 (1969). https://doi.org/10.1143/PTP.41.705Structure of light exotic nuclei studied with amd model

. Nucl. Phys. A 616, 394-405 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(97)00108-5Antisymmetrized Molecular Dynamics: a new insight into the structure of nuclei

. C. R. Phys. 4, 497-520 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/S1631-0705(03)00062-8Clustering in Yrast States of 20Ne Studied with Antisymmetrized Molecular Dynamics

. Prog. Theor. Phys. 93, 115-136 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1143/ptp/93.1.115Alpha cluster condensation in 12C and 16O

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87,Variational calculation of many-body wave functions and energies from density functional theory

. J. Chem. Phys. 119, 1285-1288 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1593014Interacting fermions and bosons with definite total momentum

. Phys. Rev. B 71,The 5 α condensate state in 20Ne

. Nat. Commun. 14, 8206 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-43816-9Mean field and beyond description of nuclear structure with the gogny force: a review

. J. Phys. G. Nucl. Part. Phys. 46,Nonlocalized clustering in 18O

. Eur. Phys. J. A 59, 49 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-023-00961-5”di-neutron” configuration of 6He

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 4996-4999 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.82.4996Three-body continuum structure and response functions of halo nuclei (i): 6He

. Nucl. Phys. A 632, 383-416 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(98)00002-5Bound state properties of borromean halo nuclei: 6He and 11Li

. Phys. Rep. 231, 151-199 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-1573(93)90141-YOptimization of the generator coordinate method with machine-learning techniques for nuclear spectra and neutrinoless double-β decay: Ridge regression for nuclei with axial deformation

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Application of an efficient generator-coordinate subspace-selection algorithm to neutrinoless double-β decay

. Phys. Rev. C 104,Optimization of the number of intrinsic states included in the discrete generator coordinate method

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Microscopic multicluster description of neutron-halo nuclei with a stochastic variational method

. Nucl. Phys. A 571, 447-466 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(94)90221-6Study of Light Exotic Nuclei with a Stochastic Variational Method: Application to Lithium Isotopes

. Prog. Theor. Phys. Suppl. 146, 413-421 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1143/PTPS.146.413Quadrupole Deformationβand γ Constraint in a Framework of Antisymmetrized Molecular Dynamics

. Prog. Theor. Phys. 123, 303-325 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1143/PTP.123.303Deformation and cluster structures in 12C studied with configuration mixing using skyrme interactions

. Phys. Rev. C 88,Optimization of basis functions for multiconfiguration mixing using the replica exchange monte carlo method and its application to 12C

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Improved naive bayesian probability classifier in predictions of nuclear mass

. Phys. Rev. C 104,Nuclear mass based on the multi-task learning neural network method

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 48 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01031-zMachine learning the nuclear mass

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 109 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00956-1Predictions of nuclear charge radii based on the convolutional neural network

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 152 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01308-xTheoretical predictions on α-decay properties of some unknown neutron-deficient actinide nuclei using machine learning

. Chin. Phys. C 46,Solving the quantum many-body problem with artificial neural networks

. Science 355, 602-606 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aag2302Optimization of the generator coordinate method with machine-learning techniques for nuclear spectra and neutrinoless double-β decay: Ridge regression for nuclei with axial deformation

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Machine learning the deuteron

. Phys. Lett. B 809,Experimental study of the halo nucleus 6He using the 6Li (γ,π+)6He reaction

. Phys. Rev. C 75,Adam: A method for stochastic optimization

. arXiv preprint. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1412.6980Systematic investigation of the hoyle-analog states in light nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 98,New description of light nuclei by extending the amd approach

. Phys. Rev. C 68,Effect of channel coupling on the elastic scattering of lithium isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 97,Equilibrium deformation calculations of the ground state energies of 1p shell nuclei

. Nucl. Phys. 74, 33-58 (1965). https://doi.org/10.1016/0029-5582(65)90244-0Effect of channel coupling on the elastic scattering of lithium isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 97,Potential Models of Nuclear Forces at Small Distances

. Prog. Theor. Phys. 39, 91-107 (1968). https://doi.org/10.1143/PTP.39.91Effective Interaction with Three-Body Effects

. Prog. Theor. Phys. 62, 1018-1034 (1979). https://doi.org/10.1143/PTP.62.1018A convenient method for generating normal variables

. SIAM review 6, 260-264 (1964). https://doi.org/10.1137/1006063Yu-Gang Ma is the editor-in-chief for Nuclear Science and Techniques and was not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.