Introduction

The existence of multi-quasiparticle configurations is consistently predicted in the low-energy-level structures of the nuclei near the N=50 closed shell. For N=47 even-odd nuclei, three-quasiparticle excitations are expected to dominate the level schemes, and the simplest excitations available will come from the three-neutron-hole

By contrast, in the N=47 isotones heavier than 85Sr, the

The excited states in 91Ru were investigated by Arnell et al. [9] via (α, xn) reactions. Subsequently, the level scheme was extended to Jπ=41/2- at an excitation energy of 8 MeV by Heese et al. [10] using the reaction 58Ni(36Ar, 2p1n)91Ru at a beam energy of 149 MeV.

Fusion-evaporation reactions are crucial for populating excited states in nuclei and synthesizing superheavy nuclei [11-13]. This reaction mechanism results in a large excitation energy and angular momentum in the nucleus. However, this reaction populates a considerable number of exit channels, complicating the selection of a specific channel for this study. As a typical solution, data analysis often involves using auxiliary measurements to detect charged particles and neutrons simultaneously [14]. In this paper, we report the results of a low-energy fusion-evaporation reaction designed to populate low- to medium-spin states in nuclei in the A~90 mass region. The experiment and data analysis will be briefly described in the next section, followed by the details of the semiempirical shell model calculation we performed to interpret our data together with the level systematics along the N=47 even-odd isotonic chain.

Experimental details and methods

The experiment was performed using the fusion-evaporation reactions 36Ar + 58Ni at a bombarding energy of E(36Ar) = 111 MeV. The beam was delivered using the GANIL CIME cyclotron and focused on a 99.83% isotopically enriched 6.0 mg/cm2 thick 58Ni target. The low-spin states in 91Ru were populated in the 2p1n exit channel of the 36Ar + 58Ni fusion-evaporation reactions. Charged-particle emission following the decay of the 94Pd compound nucleus was detected using a DIAMANT detector system consisting of 80 CsI scintillators [15, 16]. The Neutron Wall [17], comprising 50 liquid scintillator detectors covering a solid angle of

In the offline analysis, the reaction channel leading to 91Ru was selected by sorting events containing two protons fired in the DIAMANT CsI detectors together with one detected neutron. By using this filter, approximately 2.6×107 γ–γ coincidence events were selected. The event data were mainly from the 2p1n reaction channel, with some contamination from other channels, such as 3p and 3p1n which were the main reaction channels in this experiment. The efficiency and energy calibrations of the Ge clover detectors were performed using a standard radioactive γ-ray source 152Eu. After the gain matching of all the Ge clover detectors, the coincidence data were sorted into symmetric and asymmetric (angle-dependent) matrices for subsequent analysis.

The spin and parity of the levels were deduced from information on both the directional correlations of the γ rays from the oriented states (DCO ratios) [20] and γ-ray polarization asymmetries [21]. In the γ-ray decay process, the emitted photon has an integer intrinsic spin L, which is called the multipolarity of γ radiation (for example,

The linear polarization of γ-ray transitions, which indicates their electromagnetic nature, is extracted from the scattering asymmetry between the planes perpendicular and parallel to the reaction plane. The measurement was facilitated using an EXOGAM clover detector with four crystals in one cryostat, wherein each crystal can operate as a scatterer and the adjacent crystals as absorbers. This asymmetry is represented as:

The polarization asymmetry A is negative for stretched purely magnetic transitions and positive for stretched purely electric transitions. Note that for mixed M1+E2 transitions, the

Results

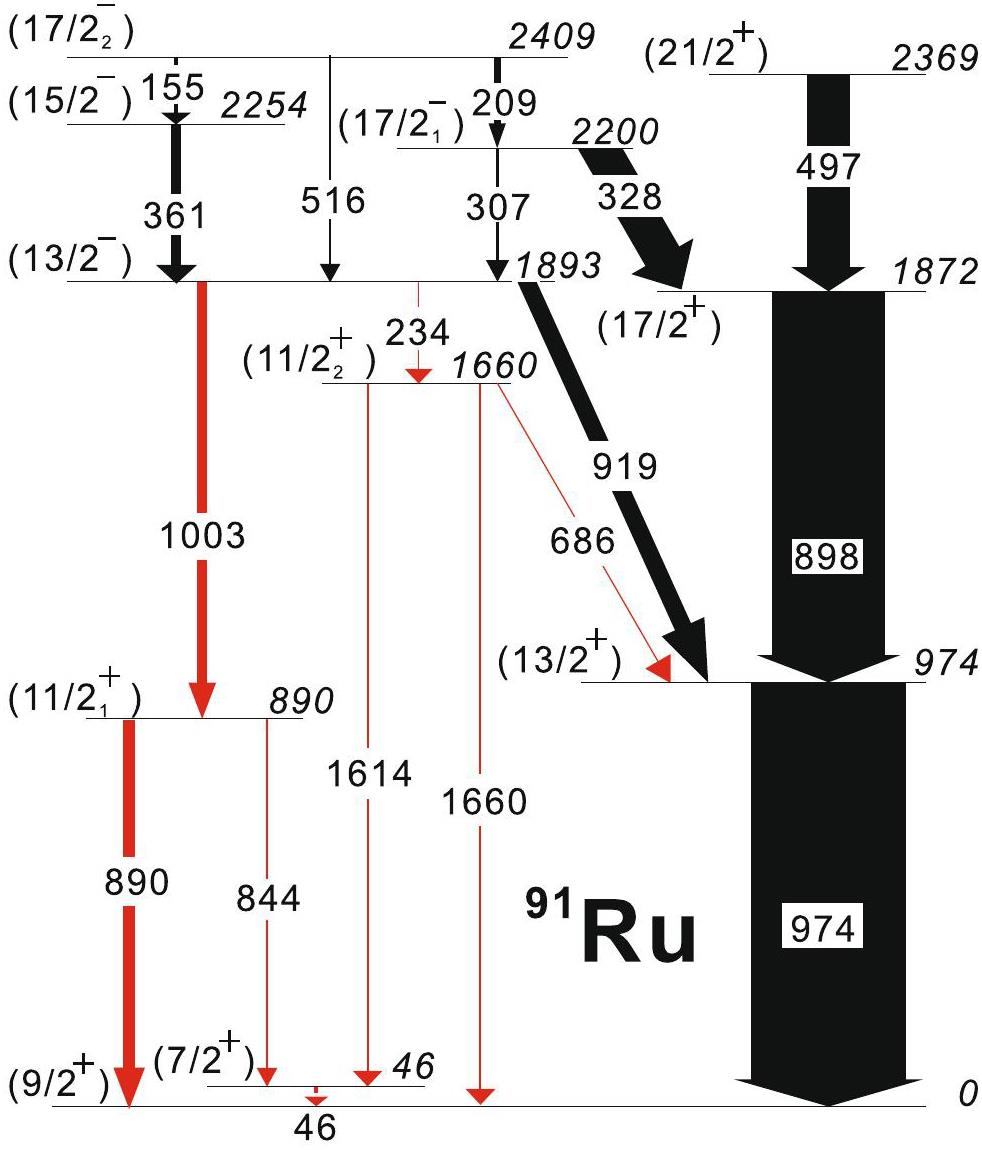

The partial-level scheme for 91Ru shown in Fig. 1 was established based on an analysis of γ-ray coincidence relationships. Spin parity assignments were derived from an analysis of the normalized DCO ratios and Compton asymmetries.

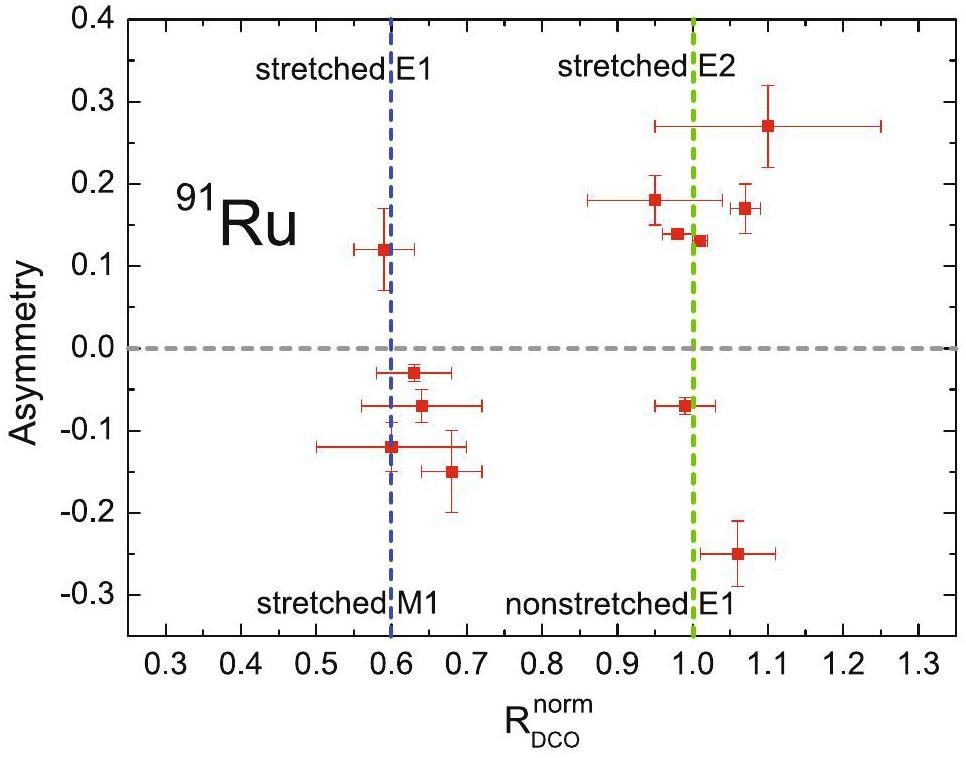

Note that stretched quadrupole transitions cannot be distinguished from ΔI=0 dipole transitions or certain mixed ΔI=1 transitions based only on DCO ratios. In these cases, simultaneously measuring the linear polarizations of the transitions can provide supporting arguments for spin assignments. Figure 2 illustrates a two-dimensional plot of the asymmetries as a function of the normalized DCO ratios. As shown in the plot, the polarization and multipolarity measurements together provided reasonable spin parity assignments for the levels.

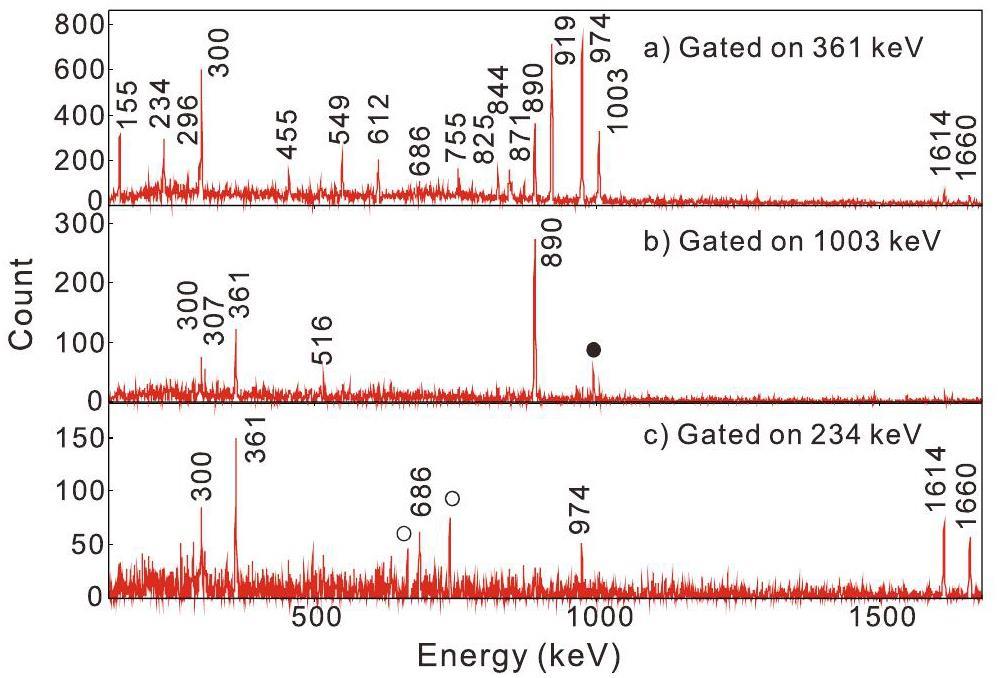

New transitions were assigned to 91Ru based on coincidences with γ rays already known in this nucleus. Typical prompt γ-γ coincidence spectra for 91Ru are shown in Fig. 3. The γ-ray transitions of 91Ru are listed in Table 1. Their relative intensities were obtained from the total projection of the Eγ-Eγ matrix. If the peak-to-background ratio in the total projection was too low or if there was contamination in the peak from other γ-ray transitions, the relevant transition energies were selected in the coincidence matrix, and the obtained projected spectra were used to fit the relative intensities. The transition energies were also measured from the total projection of the matrix. The energy uncertainties presented in the table are the sums of the statistical and calibration errors.

| Eγ (keV) | Iγ (%) | Gate (keV) | a | Asymmetry | Ei → |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45.8(5) | 7/2+ → 9/2+ | ||||||

| 155.4(3) | 3.0(2) | 0.65(7) | 974 | 1 | 0.65(7) | ||

| 209.4(2) | 4.5(2) | 17/22 → 17/21 | |||||

| 233.6(2) | 2.7(2) | 0.9(2) | 361 | 0.6 | 0.54(2) | 13/2- → |

|

| 306.8(2) | 1.9(2) | 1.04(10) | 974 | 1 | 1.04(10) | ||

| 328.0(2) | 25.1(1) | 1.06(5) | 898 | 1 | 1.06(5) | -0.25(4) | |

| 360.6(2) | 5.9(2) | 0.68(4) | 974 | 1 | 0.68(4) | -0.15(5) | 15/2- → 13/2- |

| 497.2(2) | 38.3(1) | 1.07(2) | 974 | 1 | 1.07(2) | 0.17(3) | 21/2+ → 17/2+ |

| 516.4(3) | 1.1(1) | 1.1(1) | 974 | 1 | 1.1(1) | 0.27(5) | |

| 685.8(4) | 0.8(1) | 0.6(1) | 974 | 1 | 0.6(1) | -0.12(3) | |

| 844.0(4) | 0.4(1) | ||||||

| 889.8(2) | 7.6(1) | 1.05(5) | 361 | 0.6 | 0.63(5) | -0.03(1) | |

| 898.5(1) | 73(1) | 1.01(1) | 974 | 1 | 1.01(1) | 0.131(6) | 17/2+ → 13/2+ |

| 919.8(2) | 11.3(1) | 0.99(4) | 974 | 1 | 0.99(4) | -0.07(1) | 13/2- → 13/2+ |

| 973.5(1) | 100 | 0.98(2) | 497 | 1 | 0.98(2) | 0.139(4) | 13/2+ → 9/2+ |

| 1003.6(3) | 6.7(3) | 0.98(4) | 361 | 0.6 | 0.59(4) | 0.12(5) | 13/2- → |

| 1613.9(3) | 1.3(1) | 1.58(9) | 234 | 0.6 | 0.95(9) | 0.18(3) | |

| 1659.7(4) | 1.3(1) | 1.07(8) | 234 | 0.6 | 0.64(8) | -0.07(2) |

Below the previously known 13/2- level at 1893 keV, a transition sequence consisting of 1003 keV and 890 keV γ rays fed into the ground state is observed. The ordering of the two new transitions is fixed by a newly observed 844 keV transition that crosses the transition sequence, as shown in Fig. 1. The normalized DCO ratio and asymmetry measured for the 890 keV transition are 0.63(5) and -0.03(1), respectively, indicating a stretched M1 multipolarity, which leads to the spin parity assignment of 11/2+ for the new state at 890 keV (denoted

The newly observed γ-rays of 234 keV, 1660 keV, and 1614 keV were assigned to transitions between the 13/2- level and the 9/2+ ground state. These new transitions are shown in Fig. 3. Based on the obtained normalized DCO ratios and Compton asymmetries, we assigned M1 and E2 multipolarities to 1660 keV and 1614 keV γ rays, respectively. The DCO ratio analysis shows that the 234 keV transition has dipole multipolarity (see Table 1). These assignments imply the existence of a 7/2+ state at 46 keV excitation energy and a second 11/2+ level at 1660 keV excitation energy (as shown in Fig. 1, marked

Calculation and discussion

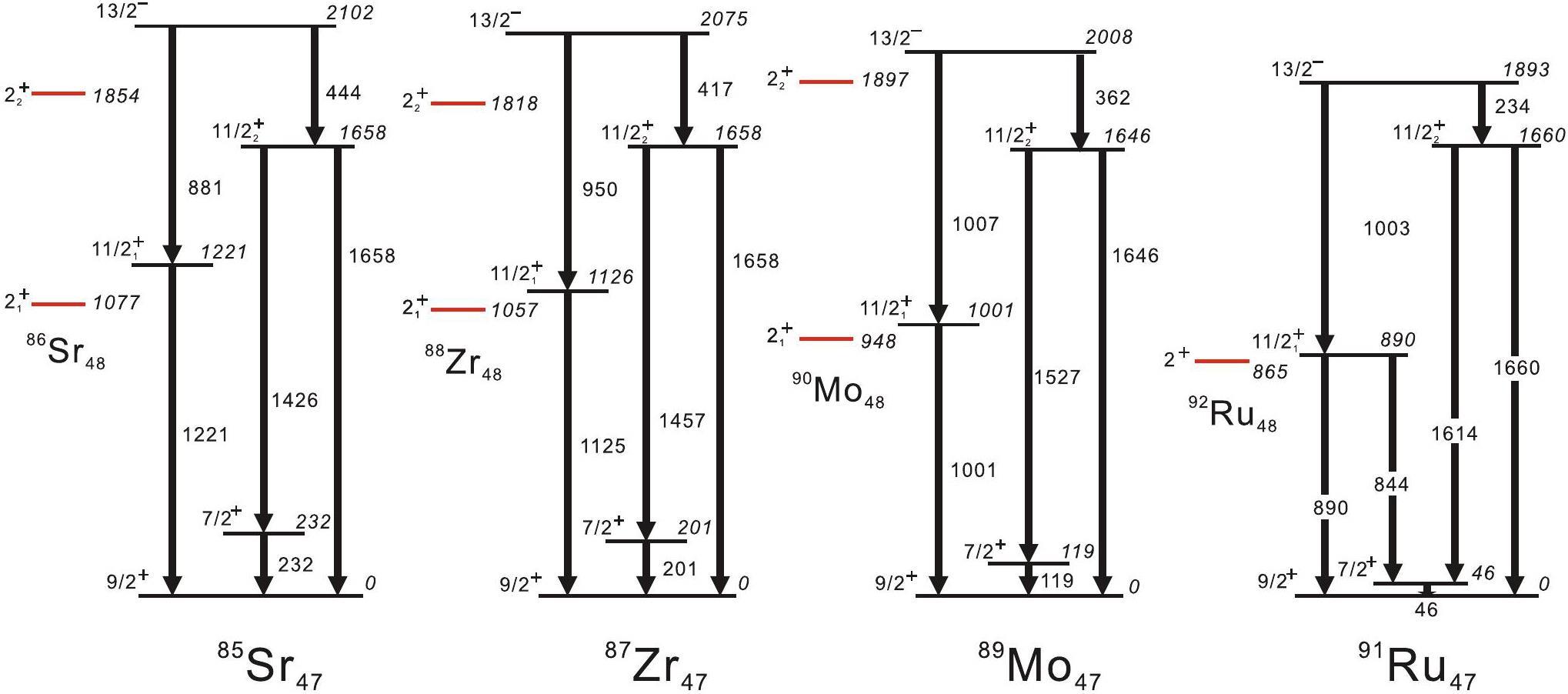

The low-energy level schemes of the N=47 nuclei with

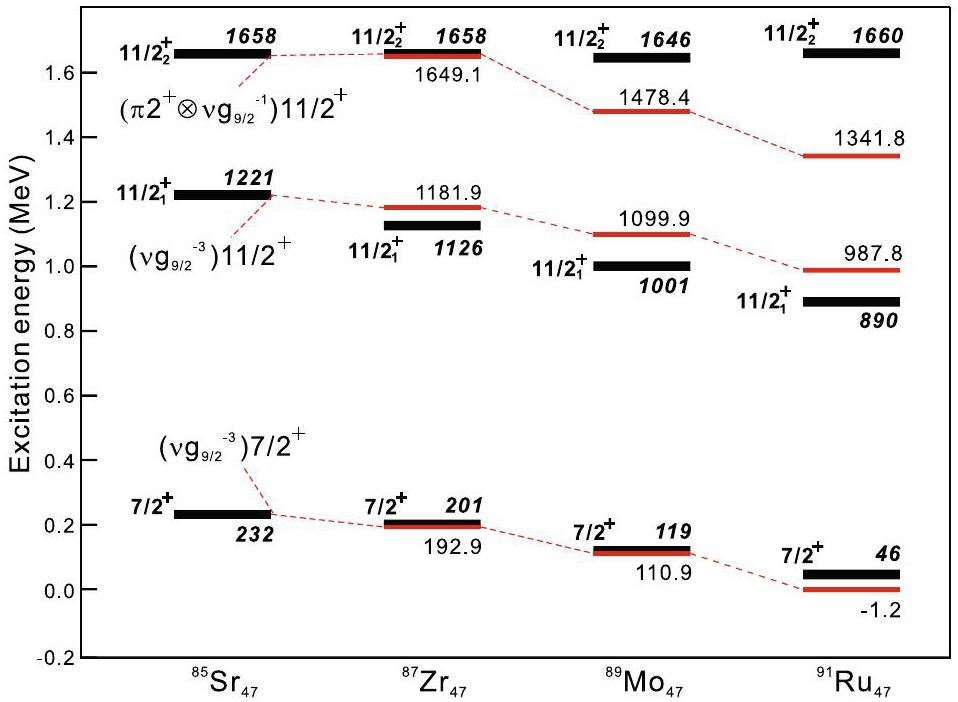

Figure 4 compares the positive-parity structures and 13/2- states in the N=47 even-odd isotones from 85Sr to 91Ru. The

Figure 4 shows that the

To confirm the validity of the above interpretation of the low-energy structure of N=47 isotones, we performed a semiempirical shell model calculation, which is discussed in the next two subsections.

Semiempirical shell model calculations

The semiempirical shell model allows calculation of the excitation energy of the complex multi-particle-hole (p-h) configuration from the excitation energies of known configurations in neighboring nuclei. This method is parameter independent and was proposed by Garvey and Kelson [32, 33] for ground-state masses, based on prescriptions by Talmi and de-Shalit [34, 35]. This technique was later extended to calculate the excited states in the A ~ 150 and 200 mass regions by Blomqvist et al. [36], providing the framework that we use here. Usually, a specific level in a nucleus is not associated with a single configuration of quasiparticles but rather corresponds to a complex mixture of many configurations of the same spin and parity. However, in favorable cases, a level can have a simple structure, and its wave function is strongly dominated by a single configuration. In general, this requires the level to be well-separated from those of the same spin and parity, which can be fulfilled for particular yrast or near-yrast levels. In such cases, the multiparticle–hole configuration can be broken into simpler configurations with fewer particles by fractional parentage decomposition, where these simpler configurations correspond to specific levels in the neighboring nuclei. This implies a linear connection between the excitation energies of the levels and nuclear ground-state masses occurring in this reduction.

The nucleus 91Ru has six proton particles and three neutron holes outside the 88Sr core. For some of its states, specifically the 9/2+ ground state and the 7/2+ and

Results

The calculated results for the 7/2+, 11/2

The energy of the 7/2+ state of 91Ru from the (

As argued above, the

A comparison between the semiempirical shell model calculation and the experimental observations is shown in Fig. 5. The figure shows that the estimate based on the three-neutron-hole

Note that the

The final remark concerns the

summary

The excited states in 91Ru were populated via the fusion-evaporation reaction 58Ni(36Ar, 2p1nγ)91Ru at a beam energy of 111 MeV. Spins and parities were assigned by measuring the DCO ratios and the linear polarization of γ rays. Three low-energy states with spins 7/2+,

High-spin states of 85Sr

. Nucl. Phys. A 280, 72 (1977). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(77)90294-9Yrast transition strengths in 85Rb and 85Sr

. Z. Phys. A 313, 297 (1983). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01439482High spin band structure of 3885Sr47

. Phys. Rev. C 90,High spin states in 88,87,86Zr

. Nucl. Phys. A 302, 159 (1978). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(78)90292-0Spectroscopy of weakly deformed bands in 87Zr: First observation of the shears mechanism in a Zr isotope

. Phys. Rev. C 98,Identification and structure of high spin particle-hole states in 89Mo

. Z. Phys. A 344, 395 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01283194Level structure of 89Mo

. Phys. Rev. C 48, 1623 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.48.1623Electromagnetic decay strengths in the isobars 89Nb, 89Mo and 89Tc

. Z. Phys. A 352, 365 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01299754First information about the level structure of 91Ru

. Phys. Scr. 47, 355 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-8949/47/3/005High spin states and shell model description of the neutron deficient nuclei 90Ru and 91Ru

. Phys. Rev. C 49, 1896 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.49.1896Systematic study of the synthesis of heavy and superheavy nuclei in 48Ca-induced fusion-evaporation reactions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 124 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01483-5Prediction of synthesis cross sections of new moscovium isotopes in fusion-evaporation reactions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 7 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01157-0Predictions of the decay properties of the superheavy nuclei 293,294119 and 294,295120

. Nucl Tech. (in Chinese) 46,CsI-Bowl: an ancillary detector for exit channel selection in γ-ray spectroscopy experiments

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 133 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01289-xImprovements in the in-beam γ-ray spectroscopy provided by an ancillary detector coupled to a Ge γ-spectrometer: the DIAMANT-EUROGAM II example

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 385, 501 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(96)01038-8The VXI electronics of the DIAMANT particle detector array

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 516, 502 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2003.08.158The EUROBALL neutron wall design and performance tests of neutron detectors

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 421, 531 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(98)01208-XThe EXOGAM Array: A radioactive beam gamma-ray spectrometer

. Acta Physica Hungarica, New Series, Heavy Ion Physics 11, 159 (2000).Evidence for a spin-aligned neutron-proton paired phase from the level structure of 92Pd

. Nature 469, 68 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09644LetterA sectored Ge-Compton polarimeter for parity assignments in photon scattering experiments

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 337, 416 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-9002(94)91111-8High-spin spectroscopy of the 142Eu, 143Eu and 144Eu nuclei

. Nucl. Phys. A 605, 191 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(96)00157-1High-spin structure of 104Pd

. Phys. Rev. C 85,A study of the 84Kr(α, 2nγ)86Sr reaction

. Nucl. Phys. A 398, 512 (1983). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(83)90299-3High-spin states in 89Nb, 88Zr and 88Nb with a shell-model description of the N = 48 and N = 47 nuclei

. Z. Phys. A 321, 485 (1985). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01411984A study of high spin states in the transitional nucleus 90Mo

. Z. Phys. A 343, 165 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01291821The level structure of 92Ru up to high spin values

. Z. Phys. A 346, 111 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01294626Energy levels and configuration interaction in Zr90 and related nuclei

. Nucl. Phys. 19, 225 (1960). https://doi.org/10.1016/0029-5582(60)90234-0Systematics of first 2+ state g factors around mass 80

. Phys. Rev. C 68,Nuclear structure investigations of 84Sr and 86Sr using γ-ray spectroscopic methods

. Nucl. Phys. A 965, 13 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2017.05.077Influence of neutron-core excitations on high-spin states in 88Sr

. Phys. Rev. C 62,New nuclidic mass relationship

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 16, 197 (1966). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.16.197Nuclear mass relations

. Annu. Rev. Nucl. Sci. 19, 433 (1969). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ns.19.120169.002245Effective interactions and coupling schemes in nuclei

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 34, 704 (1962). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.34.704Atomic masses above 146Gd derived from a shell model analysis of high spin states

. Z. Phys. A 312, 27 (1983). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01411658Gamma-ray spectroscopy on 87Sr and the energy-B(E2) rule

. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Phys. 7, 85 (1981). https://doi.org/10.1088/0305-4616/7/1/013Experimental investigation of shell-model excitations of 89Zr up to high spin

. Phys. Rev. C 86,High-spin state spectroscopy of 88,90Zr

. Phys. Rev. C 31, 1184 (1985). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.31.1184Experimental study of nuclear structure of 91Mo at high spin

. Phys. Rev. C 69,Spectroscopy of high spin states in 92Mo and 90Mo

. Phys. Rev. C 45, 2161 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.45.2161The 2.6 μs (21/2)+ Isomer in 93Ru

. Z. Phys. A 310, 137 (1983). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01433624Search for the low-lying (π1g9/2)462+ state in 94Ru

. Phys. Rev. C 75,The authors declare that they have no competing interests.