Introduction

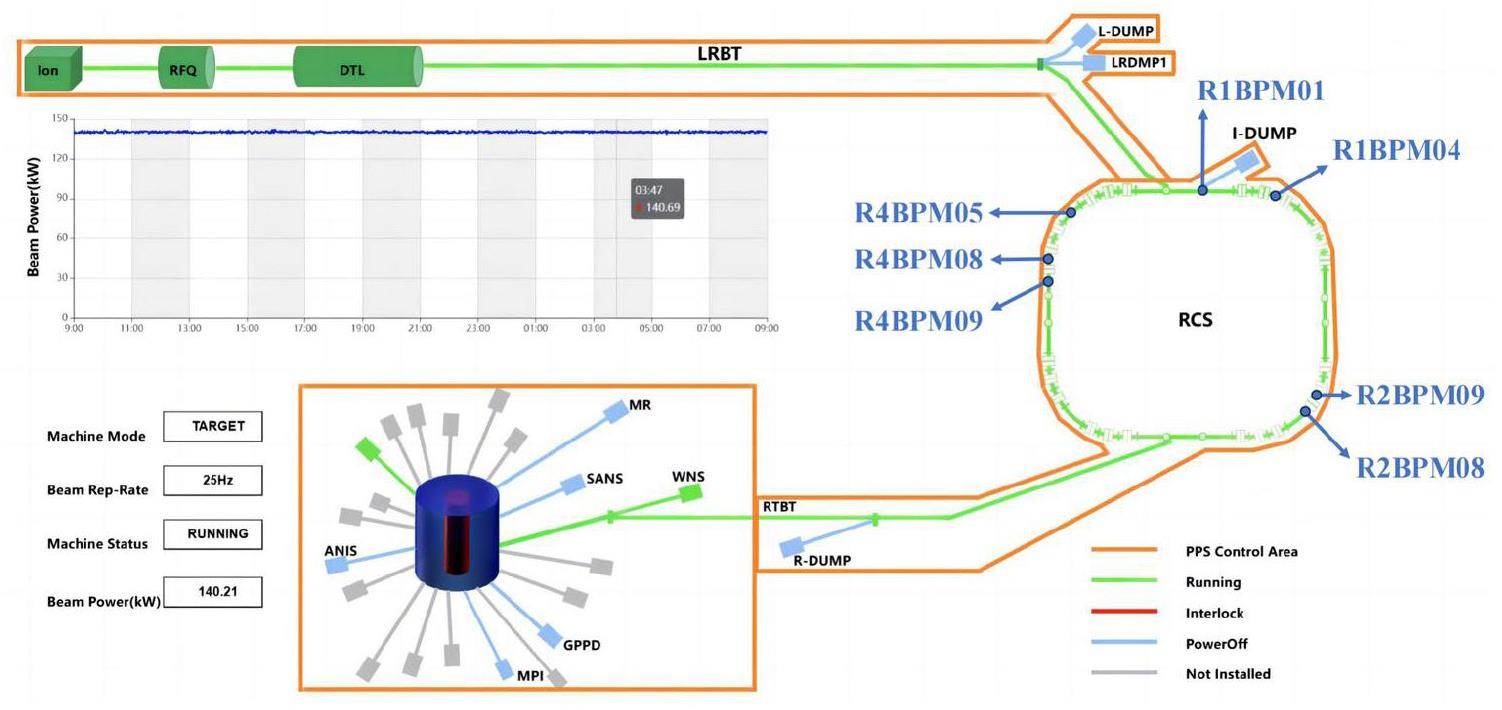

The China Spallation Neutron Source (CSNS) is a multidisciplinary neutron-scattering science facility based on high-energy proton accelerators. To further satisfy the urgent demands for neutron scattering in disciplines such as physics, life sciences, and materials science [1], the CSNS Phase II construction project is underway. As originally designed, the system aims to upgrade the beam to a high-performance level, targeting a beam extraction power of 500 kW [2-5].

At the beginning of this process, the RCS achieved a beam extraction power of 140 kW, increased from 100 kW, and a proton beam intensity of 87.5μA for target experiments. However, at this stage, it has been observed that the increased beam power makes the on-orbit beam more sensitive to disturbances in various parts of the accelerator, as well as in the magnet power supply system [5-7]. For resonant magnet power supplies that directly affect the parameters of the beam’s horizontal orbit, higher current accuracy and stability are required.

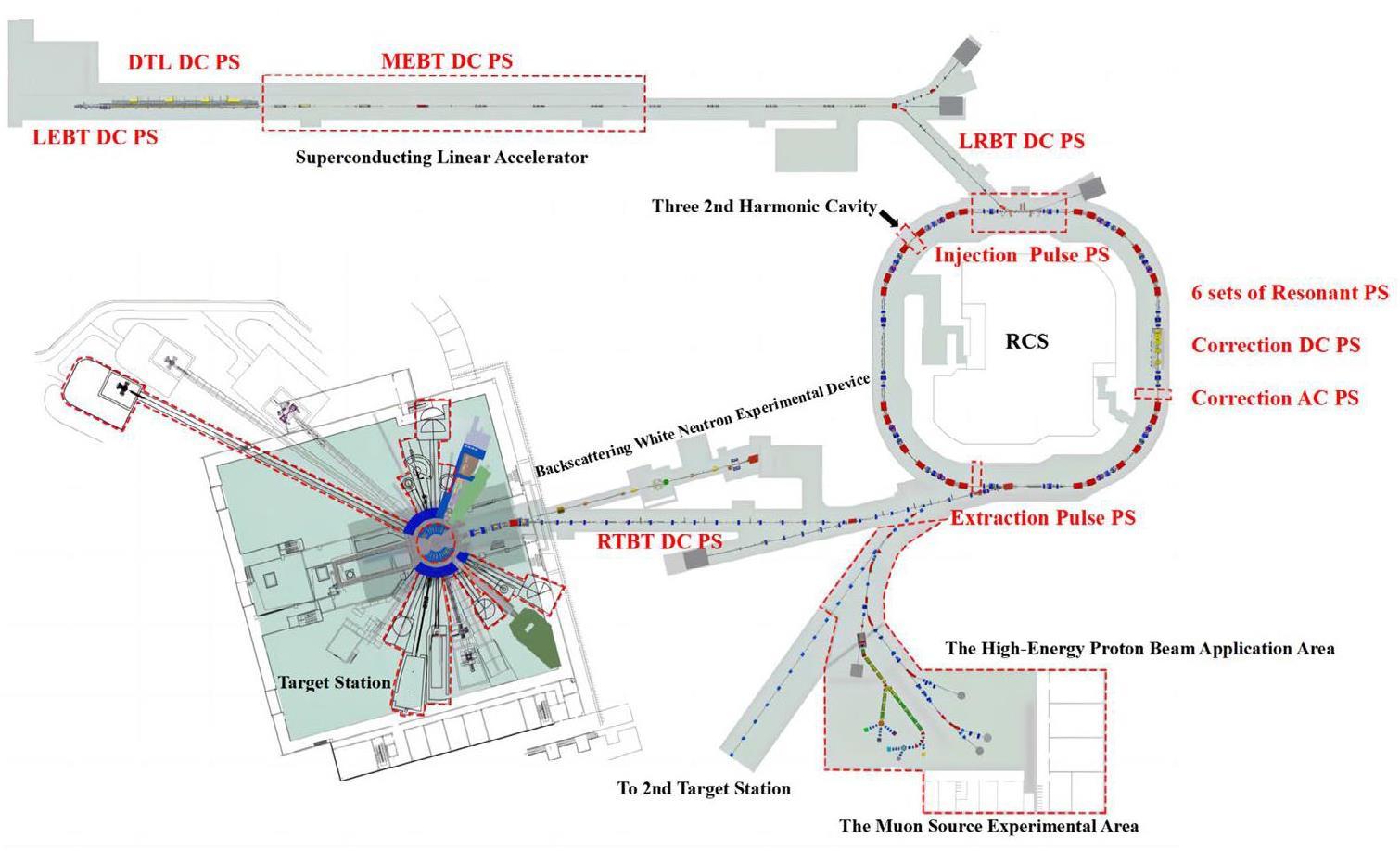

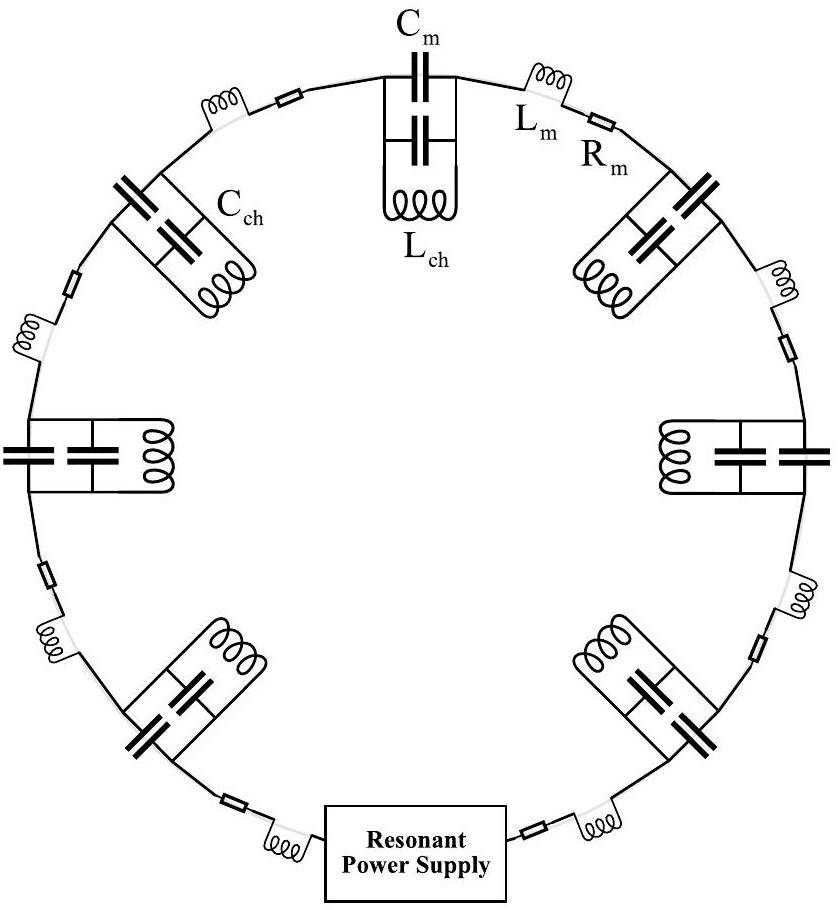

As shown in Fig. 1, the CSNS accelerator system comprises an 80 MeV linear accelerator (LINAC) and a 1.6 GeV rapid-cycling synchrotron accelerator (RCS). To achieve high beam power, the RCS must operate at a high repetition frequency (25 Hz) [8, 9]. This results in significant reactive and active power throughput for the magnets. To prevent serious disturbances to the power grid and grounding systems caused by reactive power throughput, a power supply system was designed using white-circuit resonance magnet power supplies [10]. A schematic of this process is shown in Fig. 2. In the RCS, six independent resonance networks are established for the dipole and quadrupole magnets, each with a separate power supply. These networks are controlled by a tracking control system to satisfy the synchronization precision requirements of the dipole and quadrupole magnet fields.

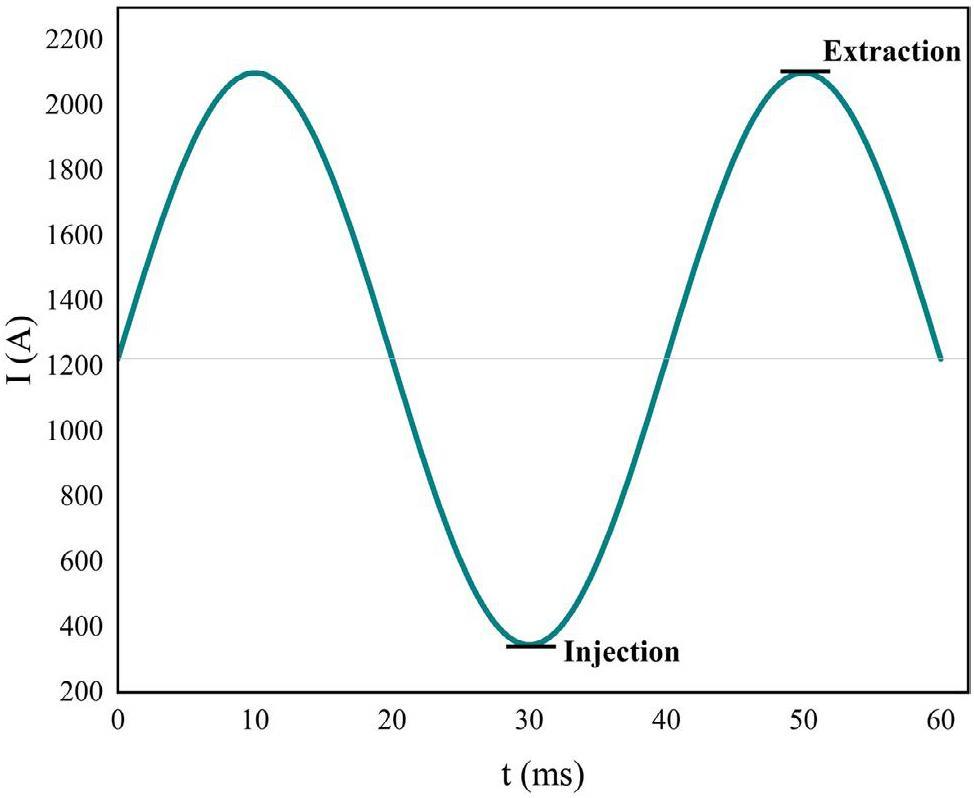

The resonant magnet power supplies consist of one Bend Magnet Power Supply (BPS) and five Quadrupole Magnet Power Supplies (QPS). They provide the excitation and drive for 24 dipole magnets and 64 quadrupole magnets, respectively [11]. the ideal operation of the RCS, the dipole and quadrupole magnets are excited using 25 Hz sinusoidal current waveforms with a DC bias. However, dipole magnets capable of handling an excitation current peak of approximately 2300 A (the maximum design value) without entering the saturation zone would require a design significantly larger in both volume and dimensions than the models currently utilized in the RCS [12-16]. Such an increase in size would necessitate expanding the spatial requirements of the RCS ring tunnel, leading to a significant surge in construction expenses. In light of these considerations, the CSNS project was designed from its inception to employ compact-sized dipole magnets. This approach is complemented by an innovative strategy involving multiple harmonic currents with 25 Hz as the fundamental frequency to synthesize and inject the dipole magnets, ensuring an optimal balance between performance and cost-efficiency [17] (Fig. 2).

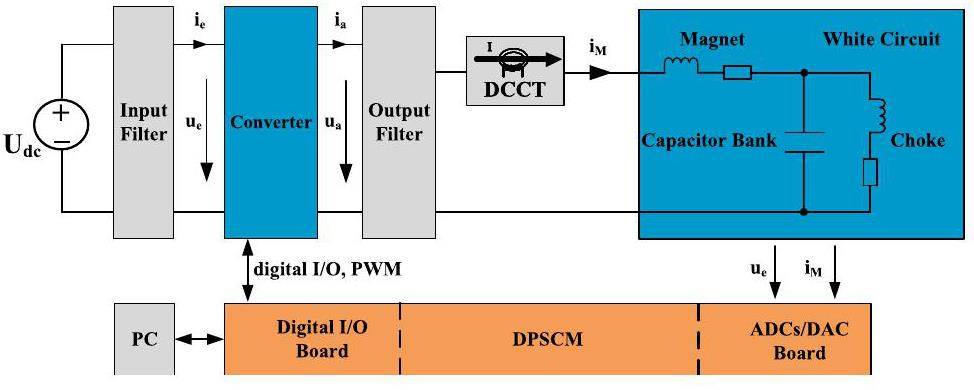

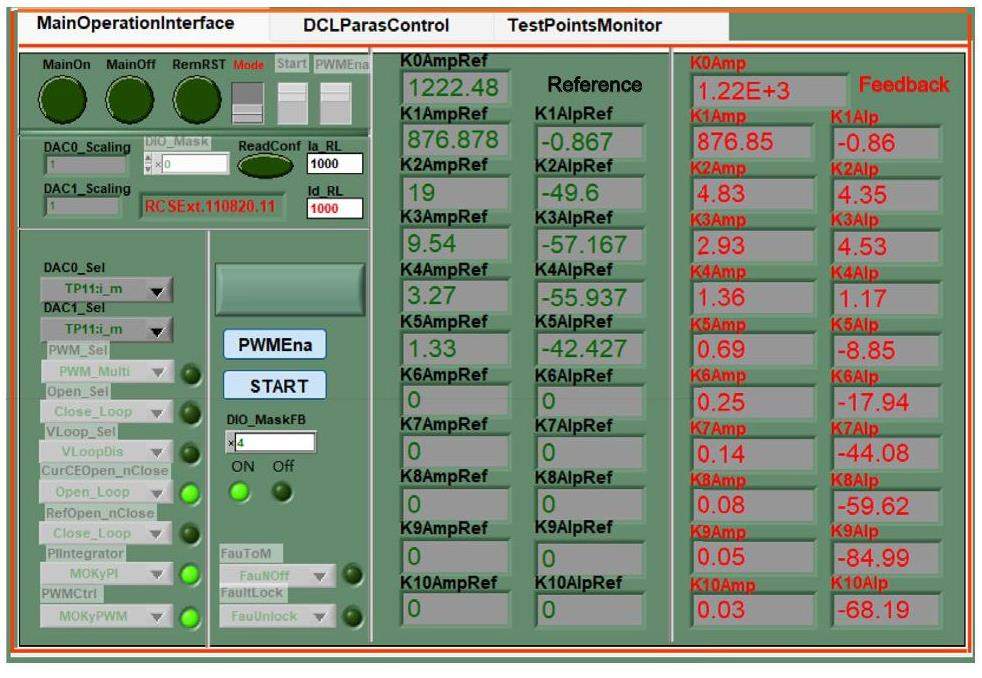

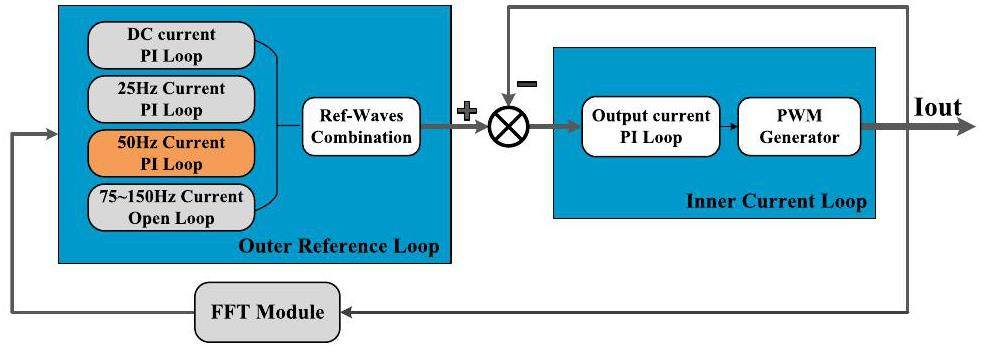

The Digital Power Supply Controller Module (DPSCM) used in the resonant power supplies is the main component for realizing the aforementioned strategy. It employs an Altera field-programmable gate array (FPGA) as its logic control core for output current, while the NIOS II soft core handles the communication components [18-20]. The actual control process of the power supply is illustrated in Fig. 3. The output current and voltage are sensed and digitally processed through an ADC/DAC board [21, 22]. The DPSCM utilizes a dual-closed-loop PI control algorithm to regulate the quasi-sinusoidal output current by adjusting the amplitude and phase. Finally, the corresponding PWM waveforms are generated through a Digital I/O Board to achieve the desired reference current output of the power supply [23].

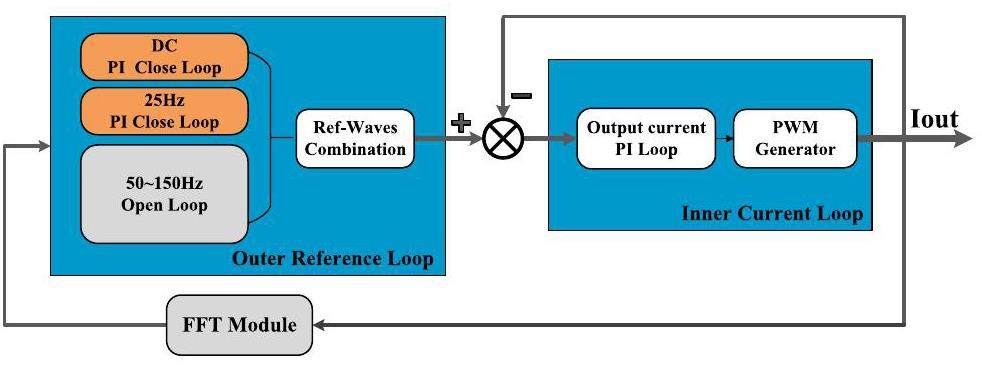

The power supply system previously proposed a control scheme based on double-loop proportional-integral (PI) control, composed of a multi-harmonic reference loop and a rear synthetic current loop. This strategy is designed to precisely control the output of a 25 Hz fundamental wave and its harmonic multiples. This precision is achieved through a multi-harmonic reference loop comprising six parallel regulation loops, each dedicated to adjusting specific frequency harmonics. The outcomes of these adjustments are then consolidated by the Ref-Waves Combination module, which merges all the calculated results. These merged results serve as the reference input for the subsequent stage of a conventional PI control loop (inner loop).

As shown in Fig. 4 and Fig. 5, the actual implementation limits the PI control to only DC and 25 Hz, leaving higher-order harmonics under open-loop control. For the 100 kW extraction power of the RCS, this simple control strategy is sufficient to satisfy the original design requirements cost -effectively. However, in the upgrade process using this control scheme, the control effectiveness and accuracy of the higher-order harmonic currents are not ideal [24].

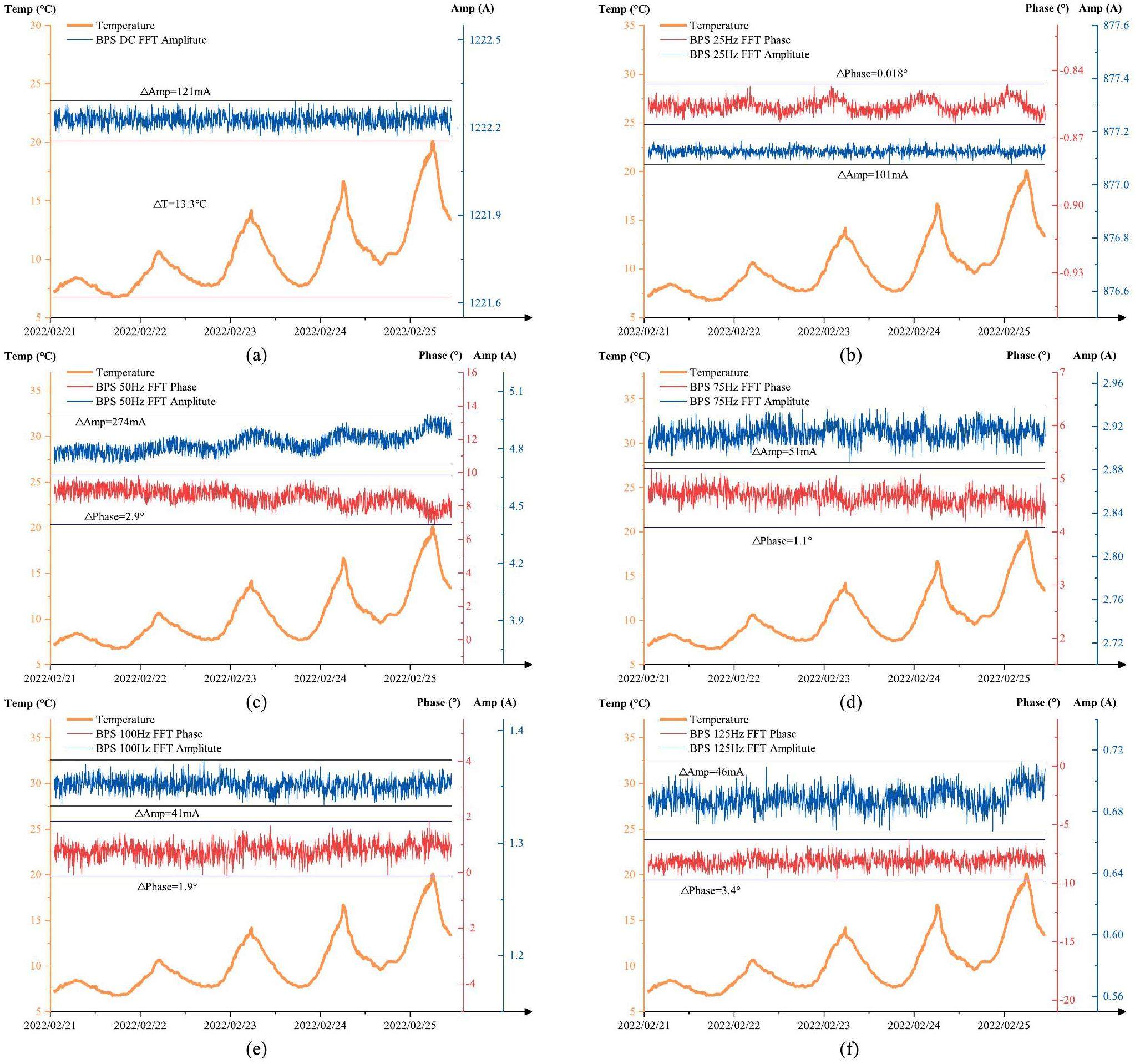

Two main factors influence the output current. Firstly, magnet saturation leads to changes in the load characteristics, causing distortion in the output current waveform [17, 25]. This distortion includes various harmonic disturbances (referred to in this paper as background current). These disturbances significantly interfere with the harmonic component output of the open-loop control. Secondly, the resonant units paired with the dipole magnets, including the resonant inductors and capacitors, are placed outdoors. The substantial temperature variations of about 10 ℃ throughout the day result in temperature drift of the current [26]. These factors notably impact performance, resulting in errors in the harmonic output current. They can even lead to beam orbit displacement and an increase in the beam loss rate.

This study conducted an error analysis and simulation to calculate the deviation of the horizontal orbit quantitatively, thereby confirming the influence of the beam current on the RCS, as detailed in Sect. 2. To minimize error interference, Section 3 describes the optimization of the control algorithm used in the DPSCM controller. Section 4 presents the verification of the numerical calculation results and the performance of the BPS using the new control scheme under real RCS operation.

Effect of current error under magnets saturation

Magnet field error contributed by current error

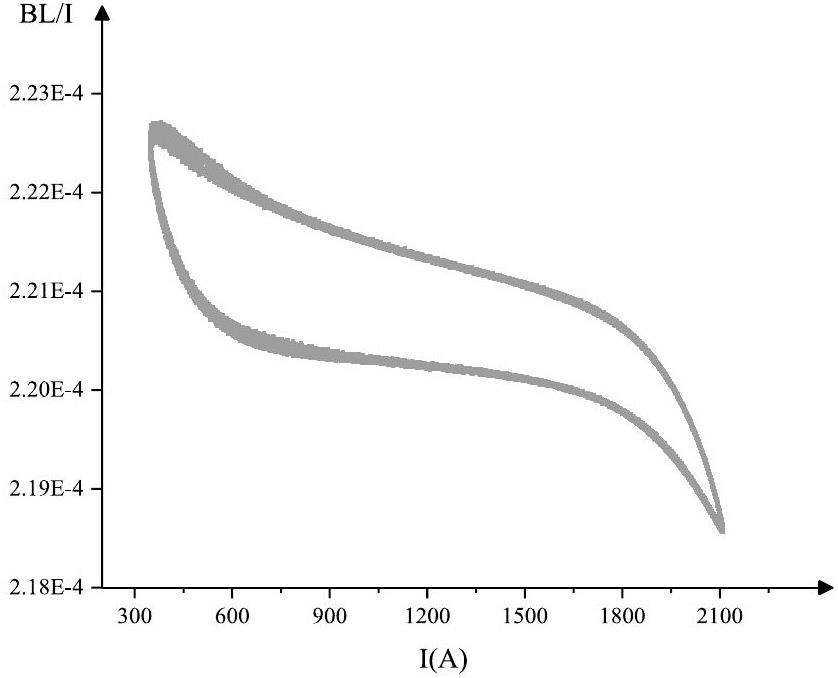

The relationship between the magnetic field and the excitation current can be clearly expressed using the transfer function, which is the ratio of the integral magnetic field strength to the excitation current (

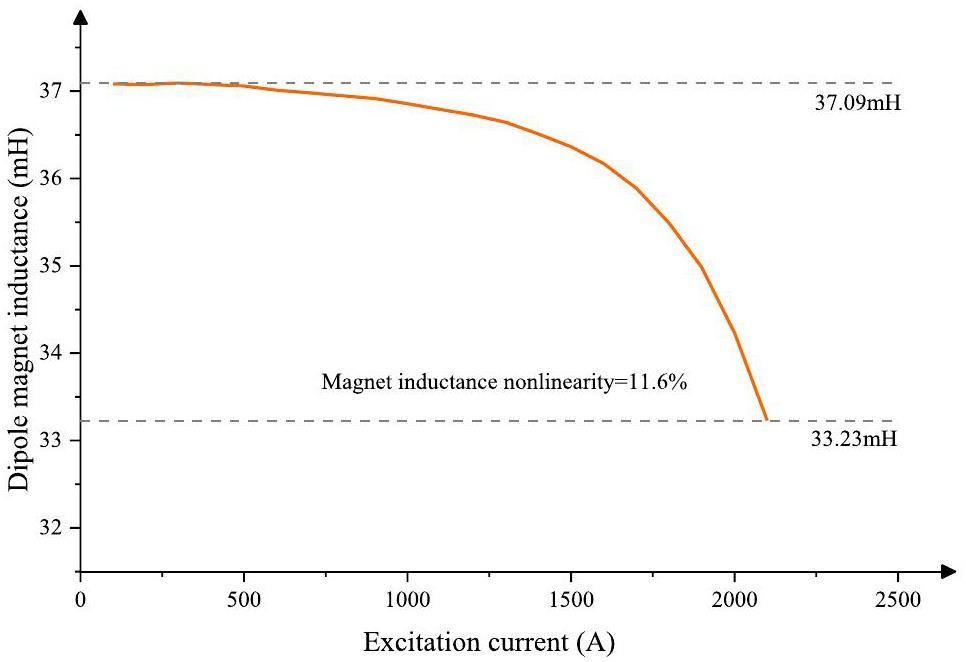

Considering that the peak work excitation current of the dipole magnet in RCS can reach approximately 2100 A, as shown in Fig. 7,

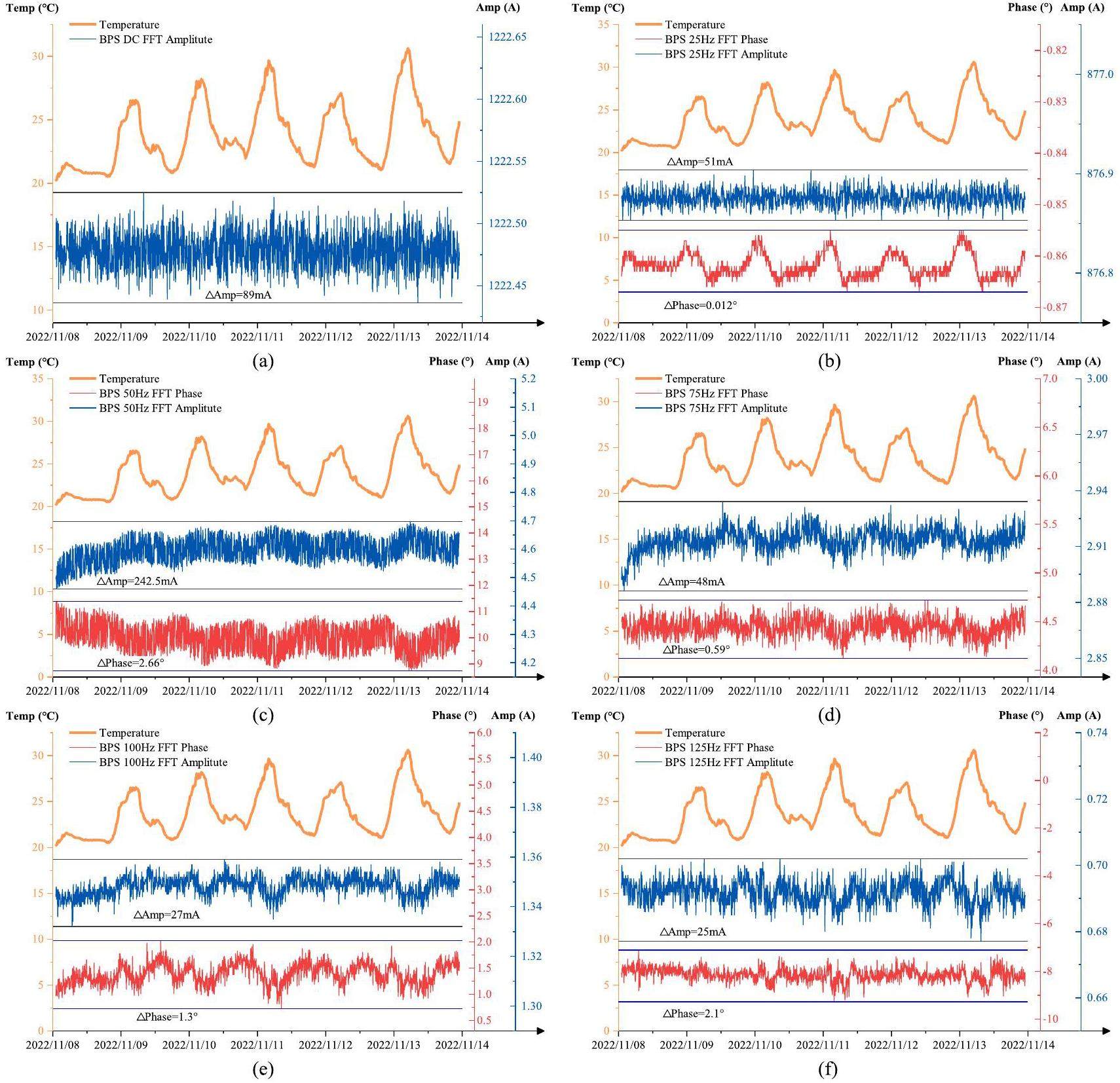

First, the current error sources must be determined. As shown in Fig. 8, this paper leverages old control strategies and actual feedback data to identify the 50 Hz current as the main source of disturbances. This observation considers the fact that both DC and 25 Hz currents are regulated through closed-loop control, the trend of the 50 Hz error variation is consistent with the trend of the outdoor temperature, and the amplitudes of harmonics at 75 Hz and higher frequencies are relatively small. Therefore, it is assumed that the 50 Hz error is the sole source, excluding the computational errors caused by harmonic superposition.

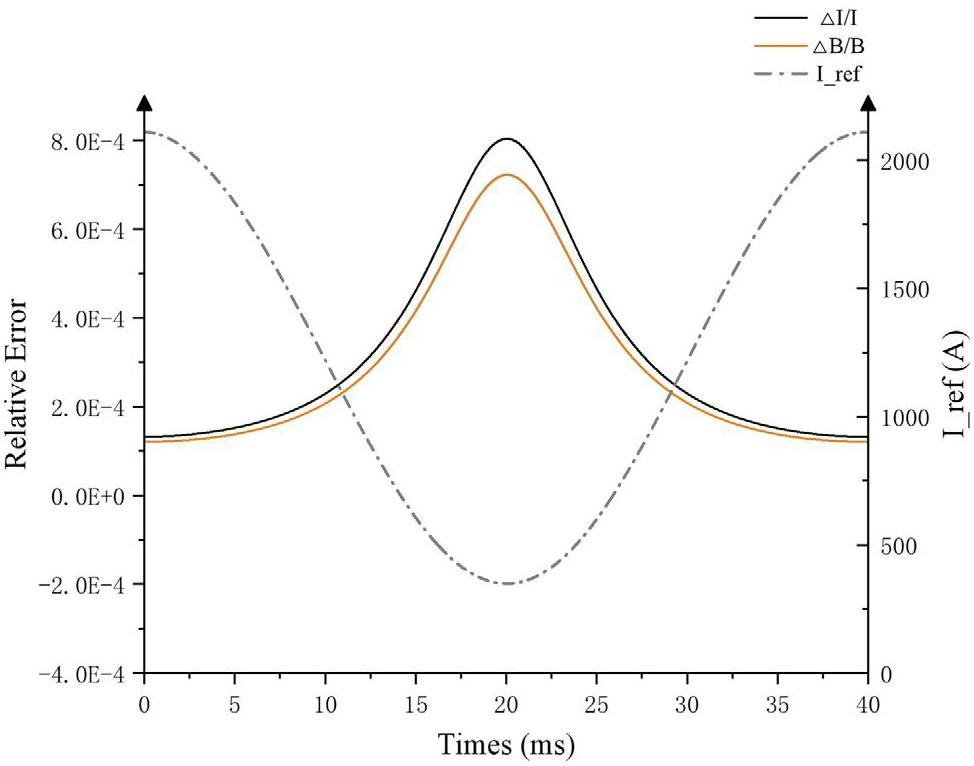

Under the parameter conditions of a 140 kW beam output power, the reference output current from Fig. 7 and the real current error from the original data, which was found to be abnormal, as shown in Fig. 8(c), were used to calculate the relative errors of the current and magnetic field for the RCS dipole magnets (for convenience of calculation and comparison, the error was approximately equal to 280 mA). Using the fitted equation obtained from the actual offline B-I magnetic field measurement data, Fig. 9 presents the relative error curves [33, 34]. The calculations show that the 280 mA error introduced by the 50 Hz harmonic current has a maximum relative current error of

Calculation on orbital deviation by current error

In the RCS, dipole magnets are used to deflect the proton beam and complete its closed orbit. Magnetic field errors in the dipole magnets manifest as errors in the beam deflection angle. A thin-lens model with an integral field strength of

Assuming that there is a disturbance

To quantify the impact of the 280 mA current error on the beam trajectory, this study employed MadX simulation software, developed by CERN for charged particle optics design and research on alternating gradient accelerators and beamlines [36].

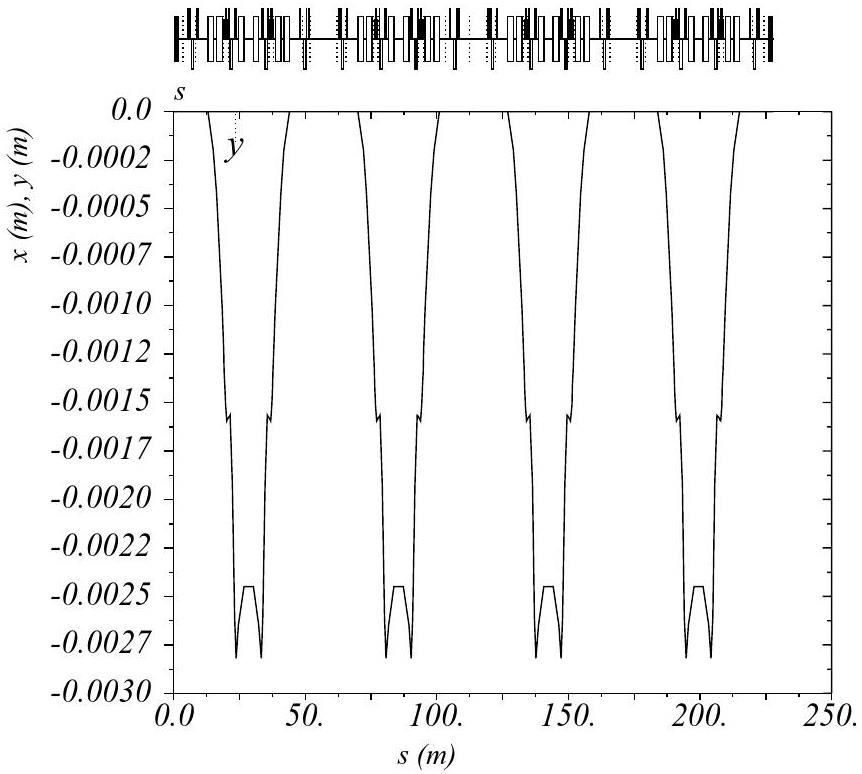

Based on the lattice structural parameters of the RCS, the maximum relative current error data in Fig. 9 was used to introduce an equivalent error source for all the dipole magnets in the ring [37]. Assuming the 50 Hz current error is the sole contributor to magnetic field uniformity fluctuations, the simulated beam trajectory results, shown in Fig. 10, indicate that the maximum horizontal offset of the beam in the four arc sections of the ring due to the 280 mA current error is 2.81 mm.

This simulation quantitatively verifies the orbit deviation effect caused by the resonant power supply in the RCS. It demonstrates that the performance of the BPS significantly influences the horizontal orbit stability.

High-order Harmonic Current Control

Load characteristics of resonant power supply

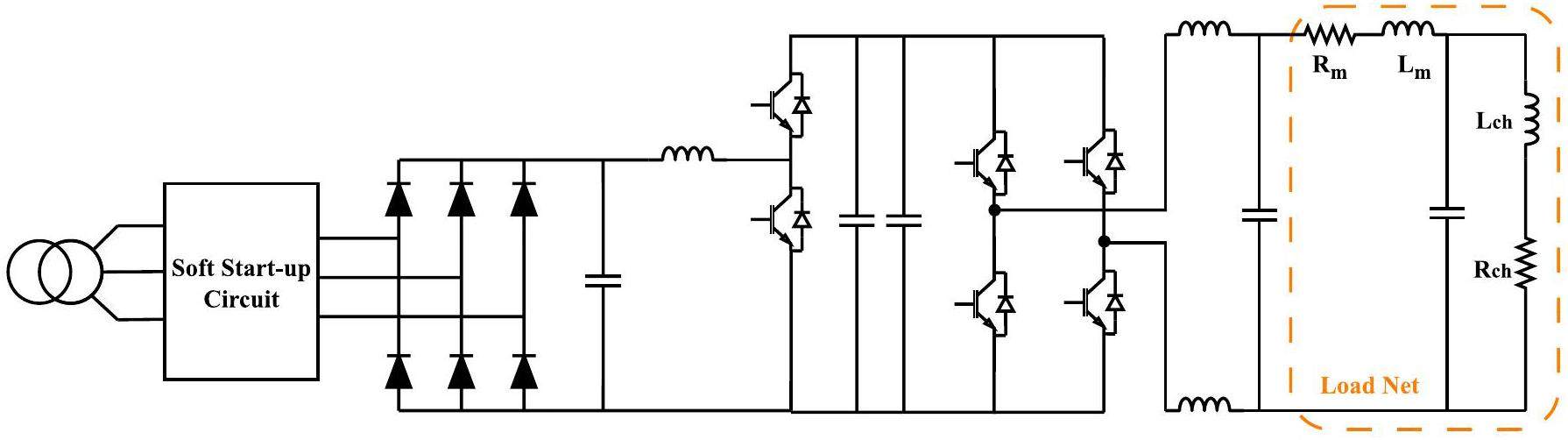

The BPS topology includes a three-phase rectifier bridge, BOOST circuit, inverter circuit, and output filtering circuit, as shown in Fig. 11. It consists of 10 power units connected in series with the load. The load of the BPS comprises 24 dipole magnet loads distributed throughout the RCS ring and 12 matching resonant units connected in series, forming the white-circuit structure.

The series-connected white circuit structure is shown in Fig. 2. Lm represents the inductance of the magnet; Lch is the inductance of the resonant choke; Cm and Cch are the resonant capacitors; and Rm and Rch are the equivalent resistances of the magnet and choke, respectively. The main components include a magnet, resonant capacitor, and resonant choke, which together form resonant units [37]. The number of resonant units varies with the power supply. The corresponding component parameters of each unit were essentially identical, ensuring that their resonant frequencies were consistently 25 Hz, as shown in Eq. 3. In fact, a load consisting of a matched resonant network exhibits nonlinear dynamic inductive characteristics under temperature variations and magnetic saturations [10, 38].

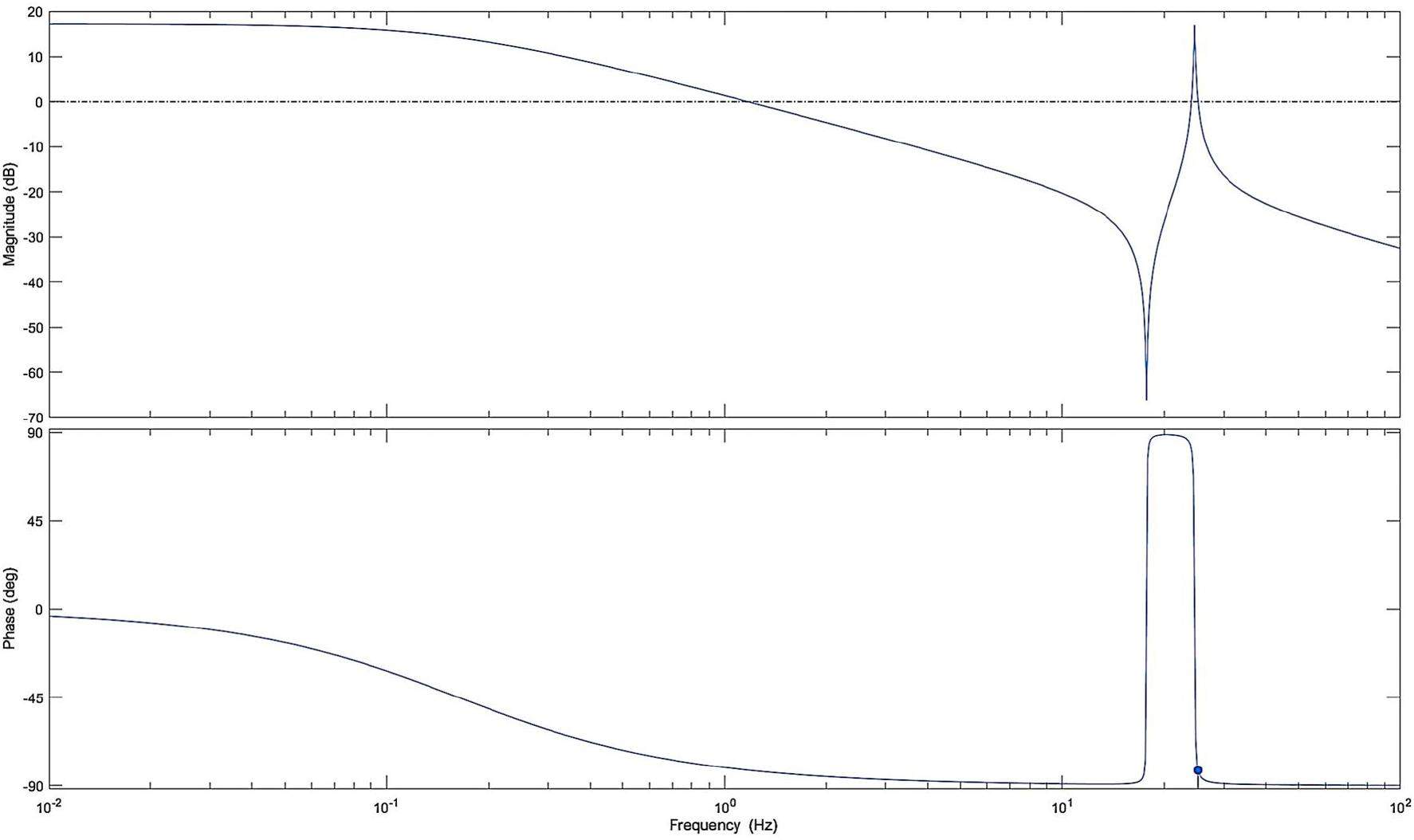

A frequency-response analysis was conducted on the actual resonant load of QPS03 (with characteristics similar to those of other loads), as shown in Fig. 12. This analysis demonstrates a strong ability to suppress higher-order harmonics of the response current, which significantly influences the design of subsequent harmonic wave compensation controls. However, it is important to note that while this load effectively suppresses frequencies outside the resonance point, the harmonic disturbances caused by current distortion in the actual load output are already attenuated, and the remaining interference is considerable.

Control characteristics with magnets saturation situation

Ideally, in the absence of magnet saturation, the magnetic field gradient should follow the variations of a 25 Hz sinusoidal current gradient. However, in practice, magnet saturation causes the load inductance to vary nonlinearly, as shown in Fig. 13. This nonlinearity leads to changes in the resonant circuit’s load characteristics and distortion of the output current waveform. To ensure the magnetic field gradient meets the required specifications and eliminate the higher-frequency components of the magnetic field, the power supply system must adopt appropriately modified current reference curves based on the actual nonlinear B-I relationship, as shown in Fig. 6. This process involves superimposing additional anti harmonic components on the resonant power supplies’ output and correcting the reference current [39, 40]. The modified current reference should include a 50 Hz component with an amplitude of 4.59 A and a phase shift of 10.3°, along with higher-order harmonics determined through offline magnetic field measurements and FFT (Fast Fourier Transform) calculations. For resonant power supplies, precise control of the frequency, amplitude, and phase of the output current is critical to achieving optimal tracking of the magnetic current across multiple resonant networks.

Design of the high-order harmonic current control

This design emphasizes the accuracy and stability of the output current in RCS resonant magnet power supplies. More precise control of the 50 Hz harmonic current’s amplitude and phase is essential. Based on given the control issues and characteristics described above, further optimization of algorithms and code structure is necessary to achieve precise control of the 50 Hz harmonic current while operating within the constraints of limited chip resources. As shown in Fig. 14, an optimized control scheme based on the DPSCM controller is proposed. This scheme incorporates PI control for the amplitude and phase of the 50 Hz harmonic into the multi-harmonic reference loop. The resulting output is then used as the reference input for rear synthetic current-loop control after the Ref-Waves combination. This configuration establishes a sophisticated dual closed-loop control system.

Considering the nonlinearity of the load inductance, disturbances from the power grid, and the characteristics of the resonant circuit, background distortion currents are generated at multiple frequencies. Under actual operating conditions, an approximately 6.7 A 50 Hz harmonic current (referred to as the background current) with a phase shift, as well as higher-order harmonic components (not detailed in this paper), are observed. The background current needs to be controlled to a 50 Hz reference value of 4.59 A. Although the fluctuation of the load current is corrected through the closed-loop feedback of the regulation circuit, closed-loop control inherently introduces a response delay, resulting in a lagging reaction. PI closed-loop control alone cannot achieve the desired reference value for the 50 Hz harmonic current, which prevents the attainment of the expected magnetic field strength. To address this limitation, this study incorporates extra harmonic compensation through an open-loop adjustment to counteract the influence of the background current.

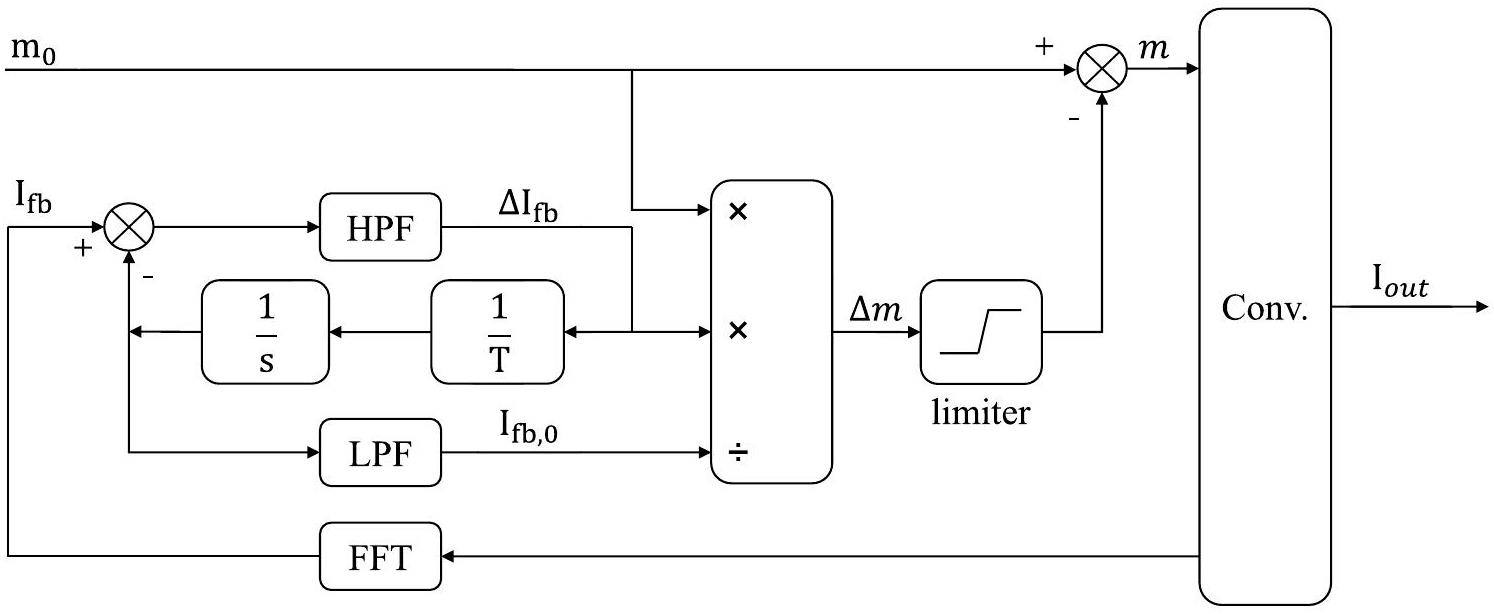

The design principle for the current feedforward involves adjusting the modulation coefficient (duty cycle) m to compensate for the effect of the background current on the output. Assuming Ifb and Iout are the current feedback and output, respectively, and

To meet the requirements for high-precision output current and ensure future scalability and flexibility, FFT is employed to determine the amplitude and phase of each harmonic component up to the fifth-order harmonic. This method can provide current feedforward for each harmonic component.

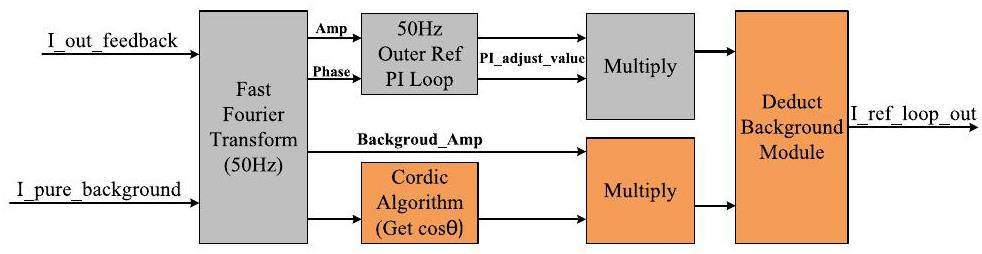

The overall control scheme includes a 50 Hz harmonic current compensation section and a PI closed-loop section for the 50 Hz harmonic current within the multi-harmonic reference loop. As illustrated in Fig. 16, this approach generates antiphase harmonic currents and subtracts background currents.

To implement harmonic compensation, the amplitude and phase information of the harmonic background current induced by the magnet are pre-obtained using the controller’s ADC board and FFT algorithm module. The open-loop response is then calculated. The Cordic algorithm is incorporated to accelerate the iterative computation of trigonometric functions with harmonic compensation phase parameters. A new "Deduct Background" submodule was developed to execute wave superposition processing with phase reversal. This module provides the reference input for the rear synthetic current loop.

In the controller, a time-multiplexing and pipeline scheme is employed for floating-point multiplication, addition modules, and the Cordic algorithm, among other IP cores, to minimize resource utilization, such as the controller’s BRAM and CLB.

Experimental verification

Current error measurement and comparison

In this study, online experiments were conducted in the RCS to visually compare the improvements achieved by the new control scheme in the performance of the resonant power supplies and the horizontal orbit deviation of the proton beam. Data were extracted from the original accelerator operation database, known as the CS-Studio archive.

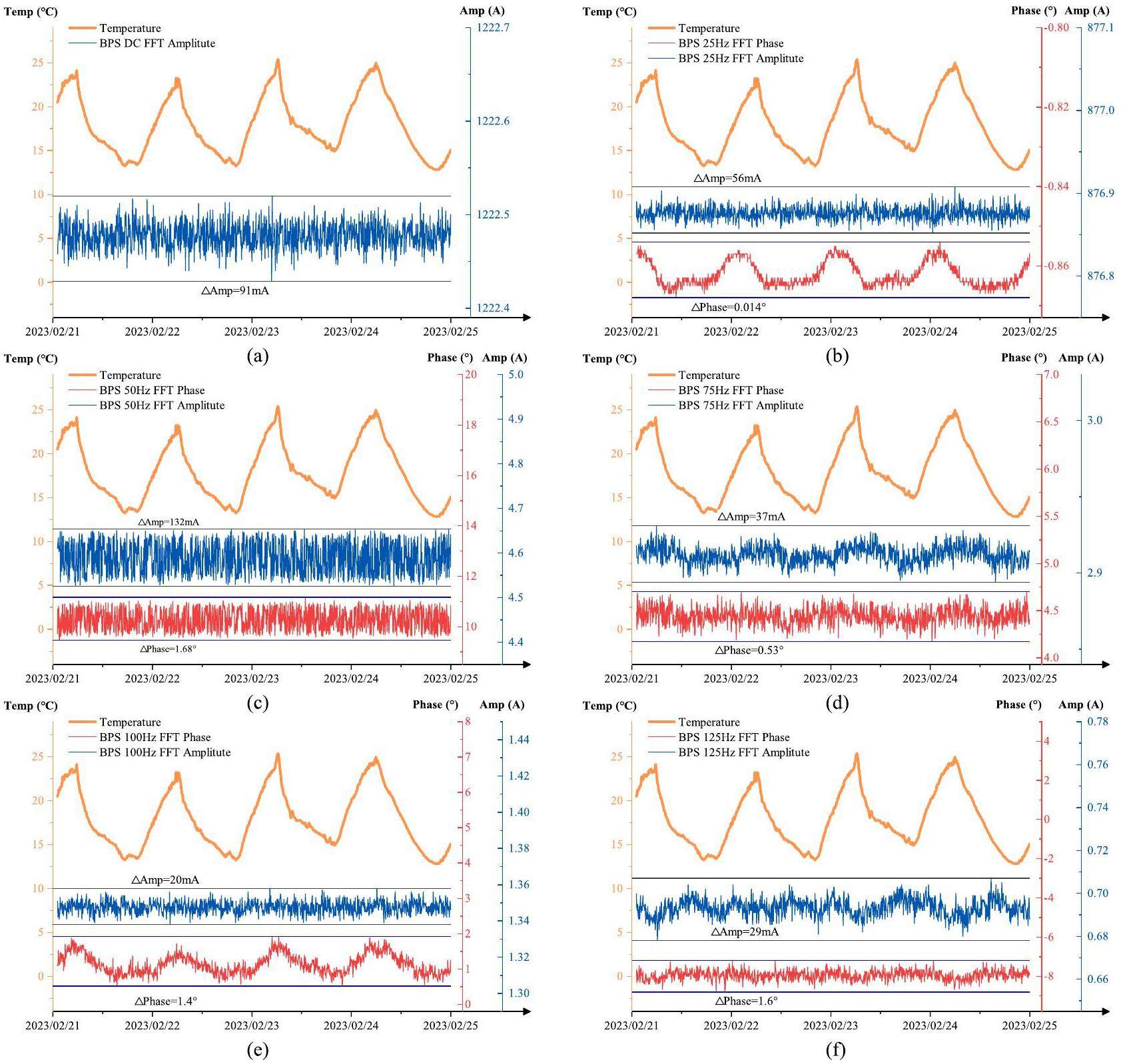

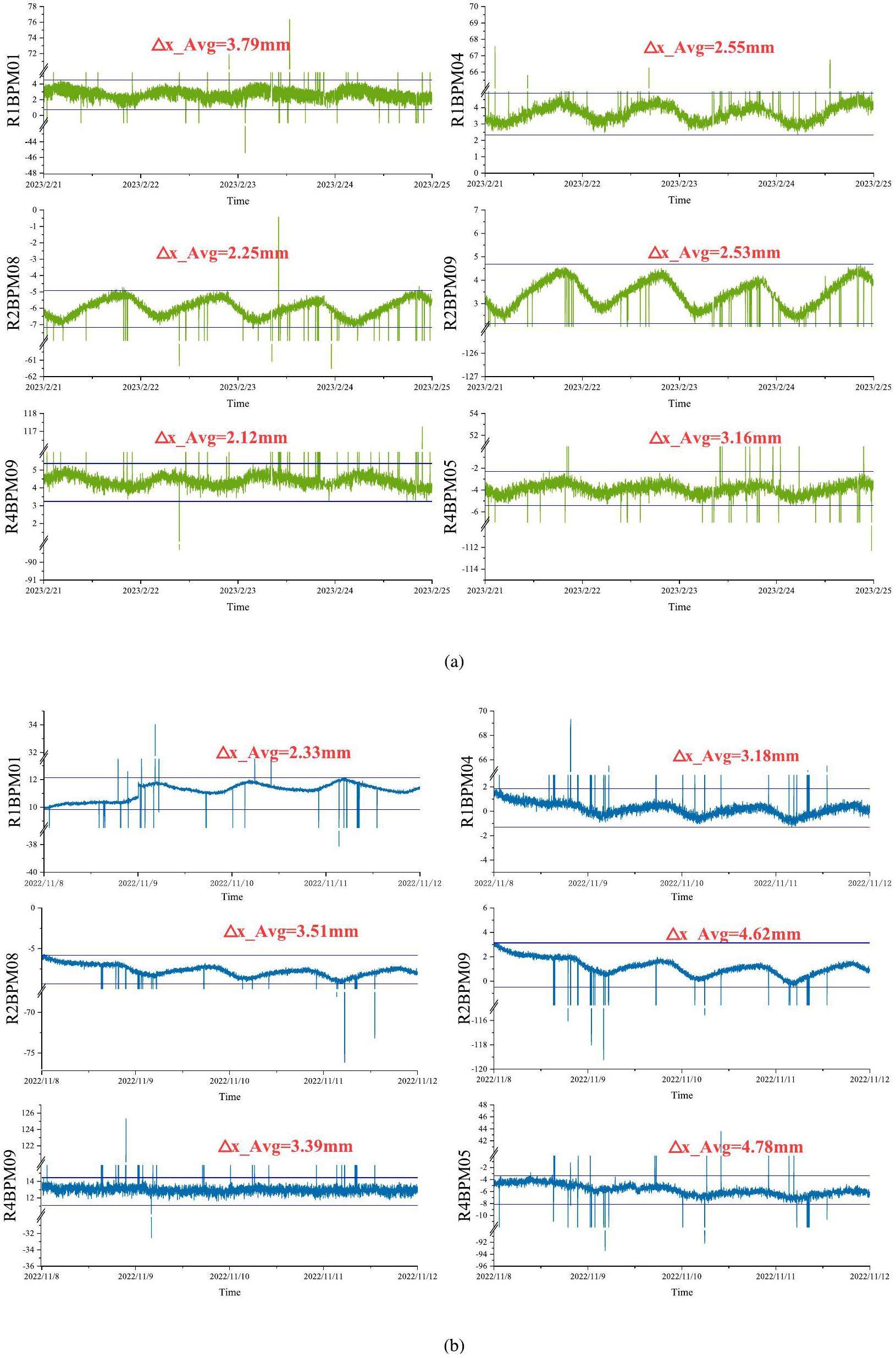

The relationship between the actual 50 Hz harmonic current output and outdoor temperature variations(the temperature sensor is far from the resonant units) was taken as a comparison in this experiment. To demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed control scheme, two sets of data showing significant temperature fluctuations in 2022 and 2023 are presented. These datasets correspond to a beam power of 140 kW and employ various control strategies.

As shown in Fig. 17 and 18, the actual output current is significantly affected by the outdoor temperature. After implementing the proposed new control scheme, the experimental results show a significant reduction in both the amplitude and phase errors of the 50 Hz harmonic current, while effectively suppressing the current temperature drift. Within a temperature variation range of 13 ℃, the error of the 50 Hz harmonic current amplitude is reduced to 132 mA, and the phase error is reduced to 1.68.

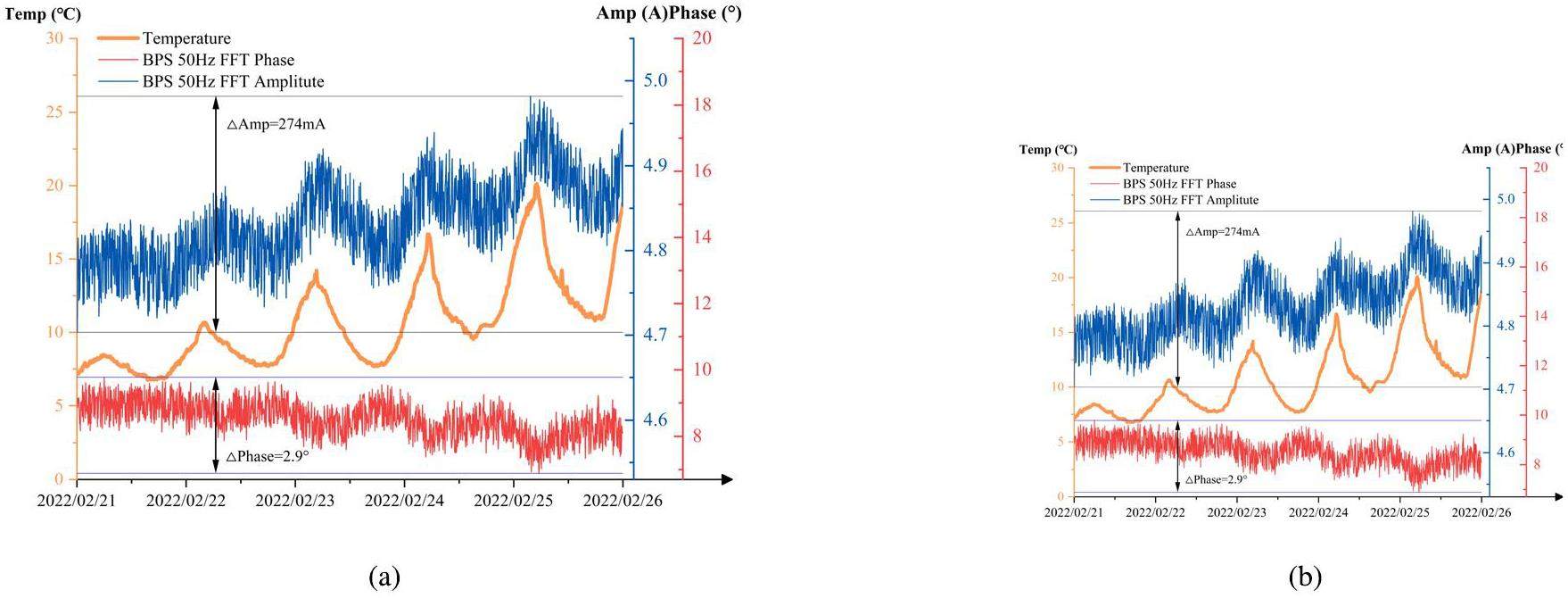

Improvement in horizontal orbital shifts of the beam

To show the main contribution of 50 Hz output current error to the beam trajectory horizontal displacement, another set of past representative operational data of 100 kW is listed, which has a large temperature difference, as shown in Fig. 19. The data were detected by a Beam Position Measurement (R4BPM05), which reflects the negative displacement in the horizontal direction caused by temperature variations. Under open-loop control with the main disturbing contribution, a 274 mA error in the 50 Hz harmonic current, the beam trajectory experienced a horizontal displacement change of approximately 4.78 mm. To ensure the generalizability of the experimental results, it was necessary to consider the injection, extraction, and high-frequency acceleration stages in the four arc segments. As shown in Fig. 20, the average horizontal trajectory displacement data from six representative Beam Position Measurements (BPMs) scattered throughout the RCS were collected during the first millisecond of each acceleration cycle for one minute. Also to ensure the consistency of the experiments as much as possible, the experimental data presented in the follow all come from after the RCS reached 140 kW, and the temperature difference, both before and after implementing the new control, exceeds 10 ℃. With the implementation of the new control scheme, the disturbance in the beam trajectory displacement is significantly reduced, as shown in Fig. 21(a). The data from these BPMs are summarized in Table. 1. Except for R1BPM01, which was located in the initial straight section and experienced anomalous data owing to other factors during the experiment, the results from the other BPMs indicated that the new control scheme designed in this study effectively suppressed the temperature drift in the horizontal trajectory of the RCS.

| 50Hz Current Control | R1BPM01 (mm) | R1BPM04 (mm) | R2BPM08 (mm) | R2BPM09 (mm) | R4BPM05 (mm) | R4BPM09 (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open loop | 2.33 | 3.18 | 3.51 | 4.62 | 4.78 | 3.39 |

| Close loop | 3.79 | 2.55 | 2.25 | 2.53 | 3.16 | 2.12 |

| Performance Improvement | Located in straight section | 19.80% | 35.80% | 45.20% | 33.80% | 37.40% |

Verification of the simulation model

In this subsection’s experiment, the new control scheme reduces the influence of relevant interference factors to a low level, which is a prerequisite for verifying the simulation results.

By manually superimposing an amplitude of 280 mA onto the 50 Hz reference value in the BPS, the quantitative impact of changes in the 50 Hz current on the beam’s horizontal orbital deviation can be intuitively observed. In the second section, it was assumed that the 50 Hz component was the sole contributor to orbital disturbance, and the simulation process adhered to this assumption. To verify the accuracy of the model in this experiment, the assumption was temporarily maintained. During the experiment, other frequency parameters of the reference waveform remained unchanged, with adjustments made only to the 50 Hz reference. Under operating conditions of 140 kW, the average horizontal trajectory displacement was calculated. Using experimental data from the RCS, where the 50 Hz current served as the independent variable and the horizontal orbit as the dependent variable, a linear fit was performed. This equation was then used to calculate orbit variations resulting from current errors and compared with the simulation results.

Measurements were taken at the 50 Hz reference harmonic current setpoint of 4.59 A, along with two additional experimental current points of 4.31 A and 4.87 A (4.59 A ± 280 mA). The results are presented in Table. 2, where x represents the 50 Hz harmonic current, and y represents the horizontal trajectory displacement in the RCS. A current error (

| BPM Name | Fit Expression (Current-Horizontal Deviation) | R2 | Calculation Results with 0.28A (mm) | Simulation results from MadX (mm) | Relative Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1BPM04 | y=-6.6823x+33.227 | 0.99 | -1.87 | -1.24 | 33.6 |

| R2BPM08 | y=-6.2035x+23.934 | 0.97 | -1.74 | -1.58 | 9.2 |

| R2BPM09 | y=-4.7699x+24.648 | 0.98 | -1.34 | -1.24 | 7.5 |

| R4BPM05 | y=-7.0944x+27.606 | 0.99 | -1.99 | -1.58 | 20.6 |

| R4BPM09 | y=-4.6625x+35.663 | 0.98 | -1.31 | -1.24 | 5.3 |

Based on the “Relative Error” column in the table, which represents the relative error between the simulated horizontal trajectory displacement results from the CSNS Lattice model and the actual horizontal trajectory displacement in the RCS, some differences were observed. These differences are attributed to performance variations in the BPMs and other internal factors within the accelerator. However, the remaining results indicate that the model aligns well with experimental expectations, confirming that the 50 Hz harmonic is the primary contributor to interference. This model provides a reliable reference for follow-up studies.

Conclusion

The new scheme proposed in this study overcomes the dynamic inductive characteristics and temperature drift of the load, effectively addressing the error issue. By reducing the output error of the 50 Hz harmonic current by 50%, the performance of the resonant power supplies is significantly enhanced. This improvement results in a more stable horizontal beam orbit in the RCS, reducing the deviation by at least 19.8%.

Furthermore, the proposed control scheme can be extended to higher-order harmonics, enabling precise control up to the fifth order while optimizing resource usage. The accuracy of the simulation model was successfully verified. This study establishes a versatile power-supply control methodology for future RCS upgrades.

Status of CSNS Project

.China Spallation Neutron Source: Design, R&D, and outlook

, Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 600 10-13(2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2008.11.017.China Spallation Neutron Source - an overview of application prospects

, Chinese Phys. C 33 1033(2009). https://doi.org/10.1088/1674-1137/33/11/021.Commissioning experiences with the spoke-based CW superconducting proton linac

, Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32 105(2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00950-7.Design and commissioning of a wideband RF system for CSNS-II rapid-cycling synchrotron

, Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35 5(2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01377-6.Analysis and simulation of the tune ripple effect on beam spill ripple in RF-KO slow extraction

, Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33 60(2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01038-6.Lifetime estimation of IGBT module using square-wave loss discretization and power cycling test

, Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33 133(2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01118-7.The Status of the CSNS/RCS Power Supply System

.Magnet Power Supply System for the Rapid Cycle Synchrotron of Chinese Spallation Neutron Source

, Atom. Energy Sci. Technol. 40, 362(2006). https://doi.org/10.7538/yzk.2006.40.03.0362.Model of 3-Mesh White Circuit

, Atom. Energy Sci. Technol. 40 475(2006). https://doi.org/10.7538/yzk.2006.40.04.0475.Introduction to the overall physics design of CSNS accelerators

, Chinese Phys. C. 33, 1-3(2009). https://doi.org/10.1088/1674-1137/33/S2/001.Application of Transient Electromagnetic Simulation to the DC-Biased AC Dipole Magnet for CSNS/RCS

, IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 26 1-4(2016). https://doi.org/10.1109/TASC.2016.2545111.Key technology of the development of the CSNS/RCS AC dipole magnet, High Power Laser Part

. Beams 29Principle of Harmonic Shim and Application for Conventional Accelerator Magnets

, At. Energy Sci. Technol. 47 277-286(2013). https://doi.org/10.7538/yzk.2013.47.02.0277.Design of RCS magnets for J-PARC 3-GeV synchrotron

, IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 14 409-412(2004). https://doi.org/10.1109/TASC.2004.829683.Pulsed Bending Magnet of the J-PARC MR

,Study of wave form compensation at CSNS/RCS magnets

, Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A. 897, 81-84(2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2018.04.035.Design of Digital Power Supply Control Module

, Atom. Energy Sci. Technol. 43, 1043-1048 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/S1874-8651(10)60073-7.Design of User IP Component in SOPC Builder

, Nucl. Electron. Detect. Technol. 29 172-176(2009). https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.0258-0934.2009.01.042.Design of Digital Power Supply Control System Based on NiosII

, Comput. Meas. CONTROL 17 881-883,886(2009).Network measuring system for high precision stabilized current supply

, 40 249-251(2006).Research on protection system of resonant network in CSNS magnet power supplies

. Radiat Detect Technol Methods. 4, 277-283.(2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41605-020-00181-1.Design of Digital Logic Control for Accelerator Magnet Power Supply

, Nucl. Electron. Detect. Technol. 28 567-570(2008). https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.0258-0934.2008.03.029.Study on the effects of chromaticity and magnetic field tracking errors at CSNS/RCS

, Chinese Phys. C. 38,Eddy current effects in a high field dipole

, Nucl. Sci. Tech. 28 173(2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-017-0325-5.Design of control algorithm for accelerator magnet power supply with large time constant load

, Radiat. Detect. Technol. Methods 4 383-391(2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41605-020-00195-9.Research and Development of the AC Magnets for CSNS/RCS

, IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 22,Magnetic Measurements and Commissioning of the Fast Ramped 90° Bending Magnet in the PROSCAN Gantry 2 Project at PSI

, IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 20 794-797(2010). https://doi.org/10.1109/TASC.2010.2040916.Effects of magnetic field tracking errors on beam dynamics at J-PARC RCS

.Dynamic processes in laminated magnets: simulation and comparison with experimental results

, IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 12 98-101(2002). https://doi.org/10.1109/TASC.2002.1018360.Eddy current effect of magnets for J-PARC 3-GeV synchrotron

, IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 14 421-424(2004). https://doi.org/10.1109/TASC.2004.829686.A harmonic coil measurement system based on a dynamic signal acquisition device

, Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A. 624, 549-553(2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2010.10.009.AC magnetic field measurement of CSNS/RCS quadrupole prototype

, Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A. 654, 72-75(2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2011.07.010.MAD - Methodical Accelerator Design

, http://mad.web.cern.ch/mad/; 2023 [accessedAn overview of design for CSNS/RCS and beam transport

, Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 54, 239-244(2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11433-011-4564-x.Analytic Modeling Optimal Control of Pulsed Power Supply for Accelerator Magnet

. IEEE Trans Ind Electron. 67, 5657-5665(2020). https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2019.2934025.A digital control scheme of power supply system for RCS/CSNS

, High Energy Phys. Nucl. Phys. 31 1062-1066(2007).The compensation of quadrupole errors and space charge effects by using trim quadrupoles

, Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 54 214-217(2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11433-011-4566-8.The authors declare that they have no competing interests.