Introduction

The synthesis of superheavy nuclei (SHN) is an important research topic in modern nuclear physics. With the use of

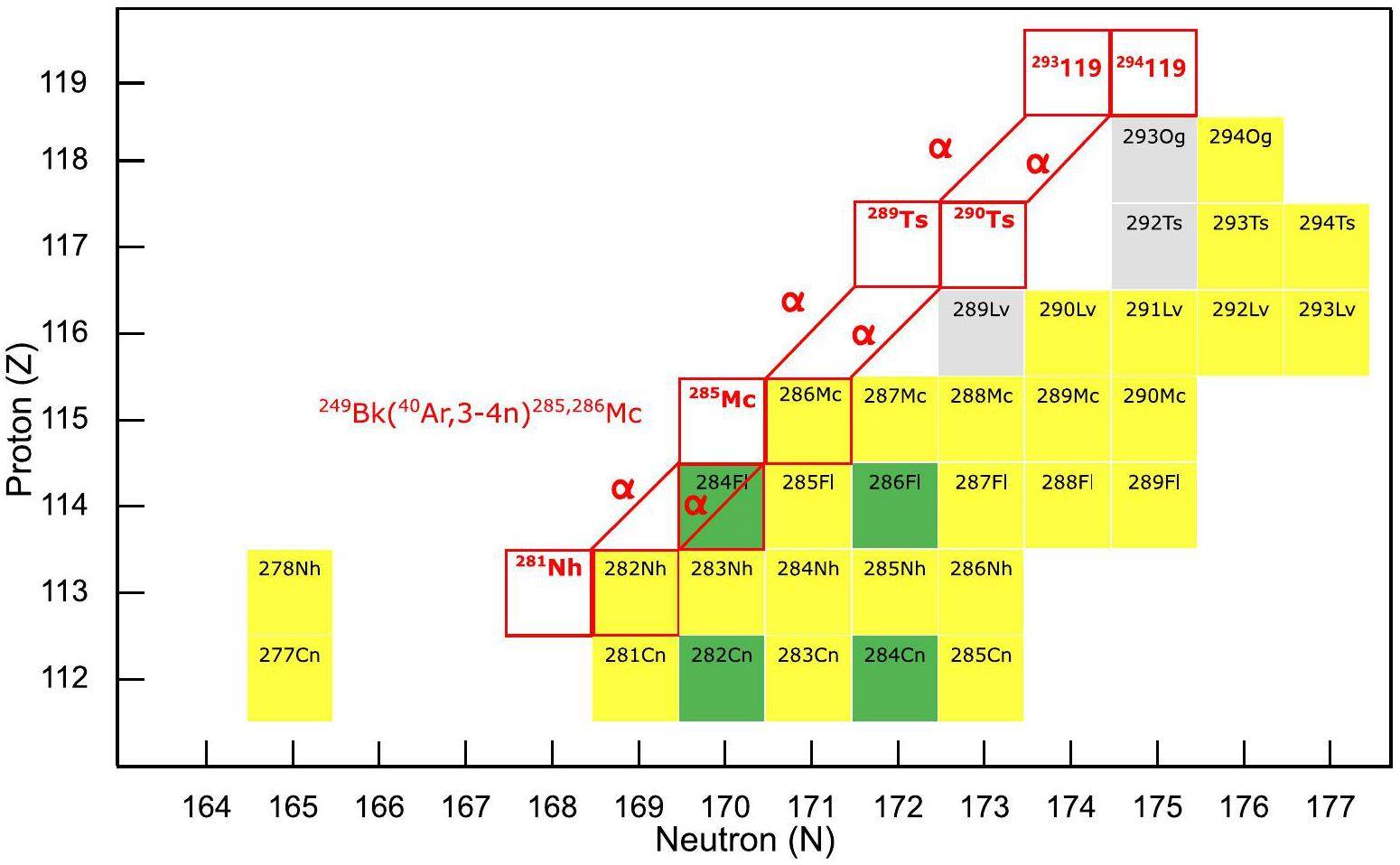

The synthesis of the new element with

In heavy-ion fusion reactions, the entire process of compound nucleus formation and decay is typically divided into three stages: the capture process, in which the colliding system overcomes the Coulomb barrier, the formation of the compound nucleus by surpassing the inner fusion barrier, and the de-excitation of the excited compound nucleus to counter fission. The evaporation residue cross-section is expressed as a sum over partial waves with angular momentum

Our aim is to theoretically analyze the three stages of fusion reactions to understand the factors influencing the evaporation residue cross-sections at each stage and explore the possibility of synthesizing key new isotopes using

Theoretical descriptions

The most widely used method for calculating the capture cross-section is the coupled-channel approach. The computer code CCFULL, which is based on the coupled-channel formalism, is used to perform these calculations (for a detailed description, see Ref. [54]). This involves numerically solving the following set of coupled-channel equations:

However, for SHN, an empirical coupled-channel (ECC) method is typically used to calculate their capture cross-sections [55]. In this method, the transmission probability

In the DNS model framework,

Results and discussion

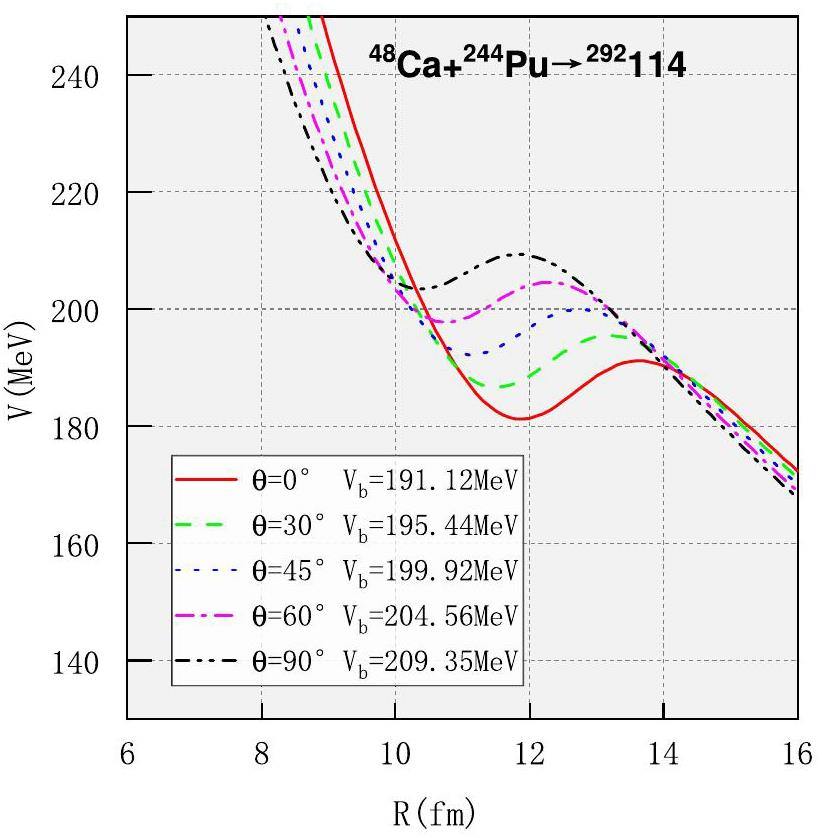

In Fig. 2, we show the dependence of the barrier height on the collision orientation with static deformation in the

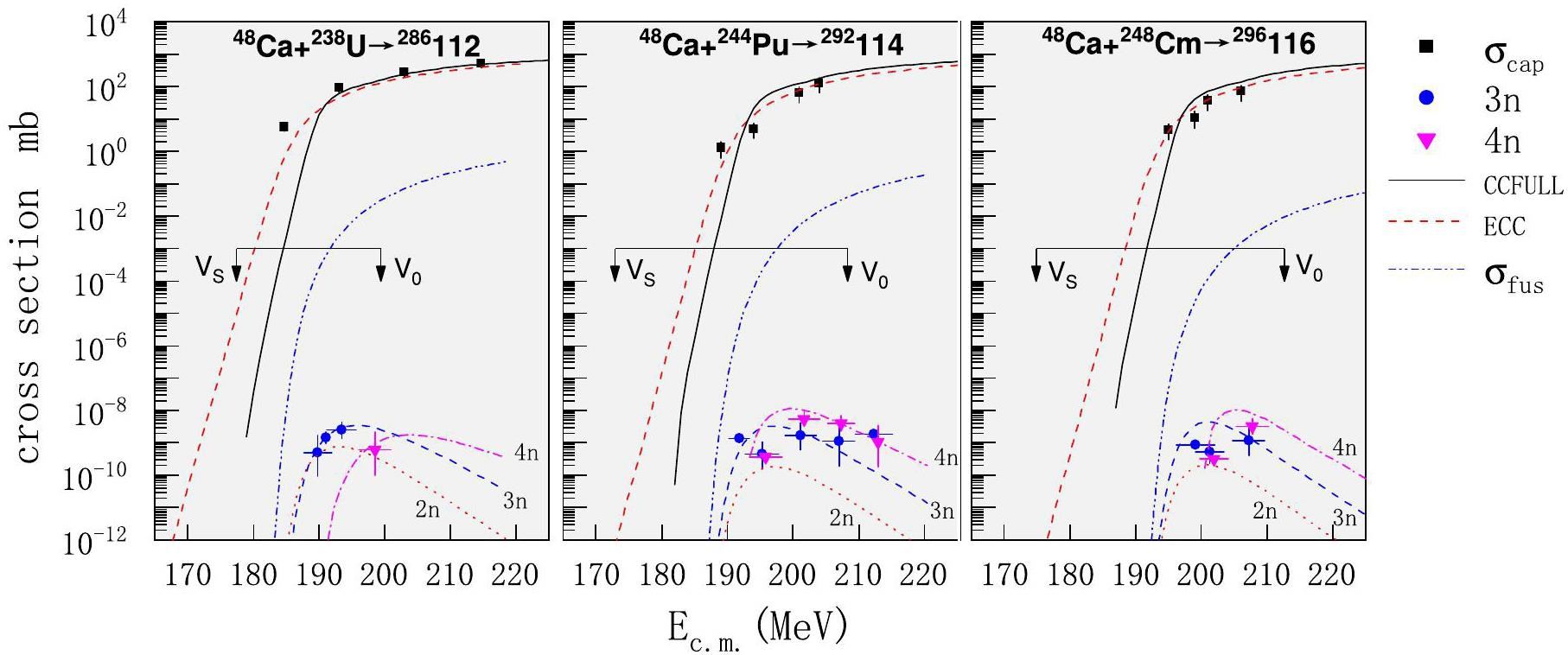

In Fig. 3, we present the capture and evaporation residue cross-sections for three reactions involved in the synthesis of SHN. The position

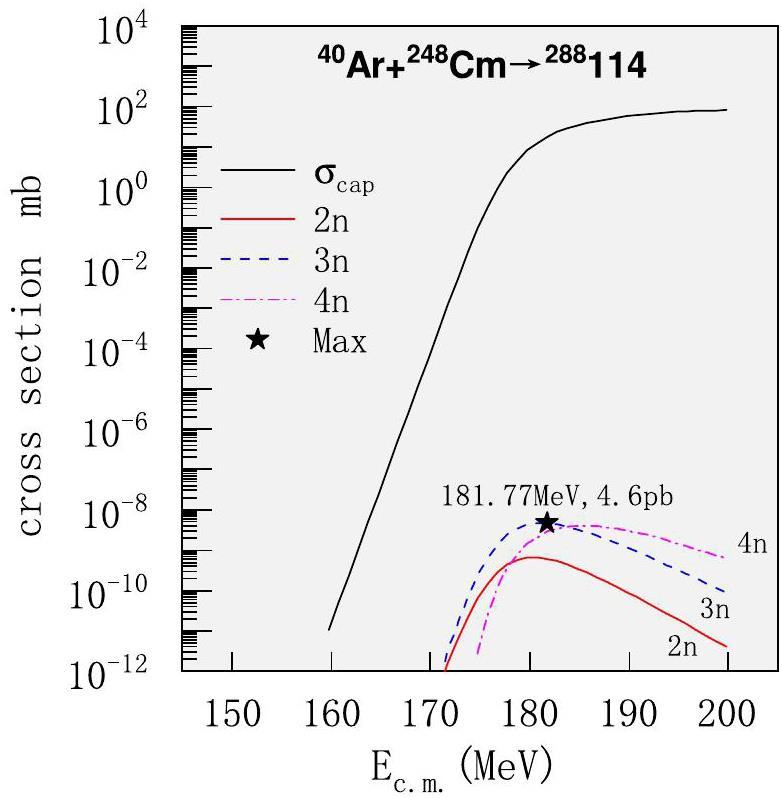

Based on the theoretical description of SHN synthesis, we conducted research on the synthesis of key superheavy isotopes. Figure 4 shows the capture and evaporation residue cross-sections for the

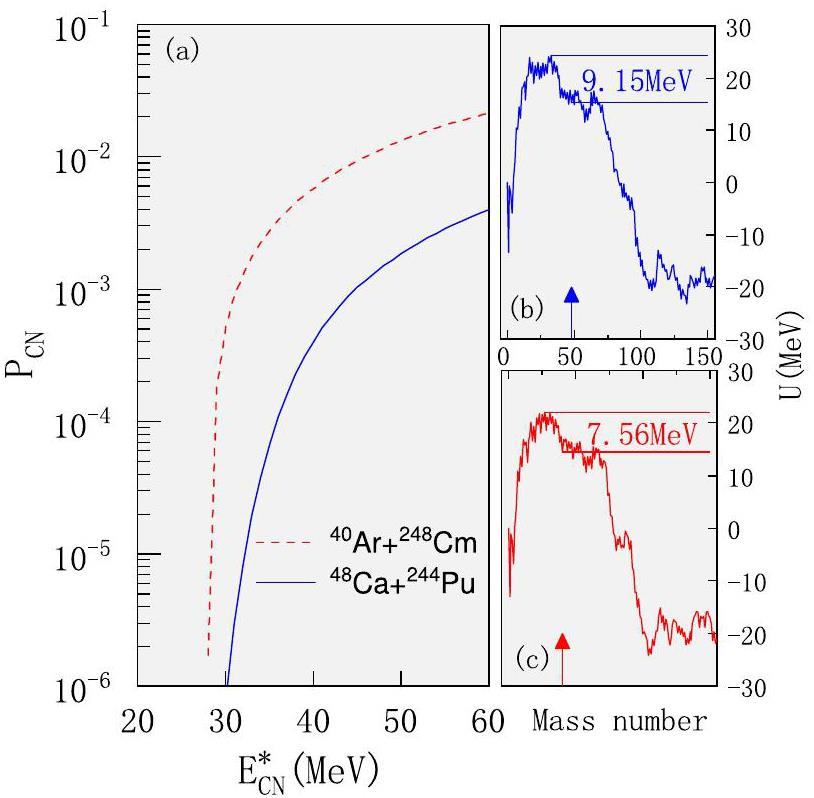

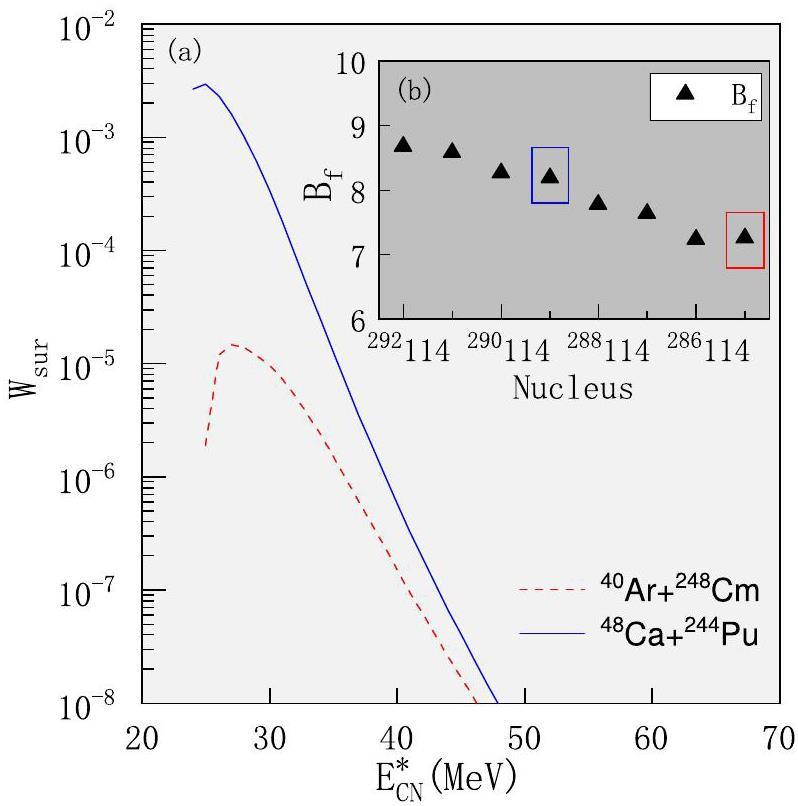

To gain deeper insight into the physical mechanisms behind the synthesis of SHN using

We also analyzed

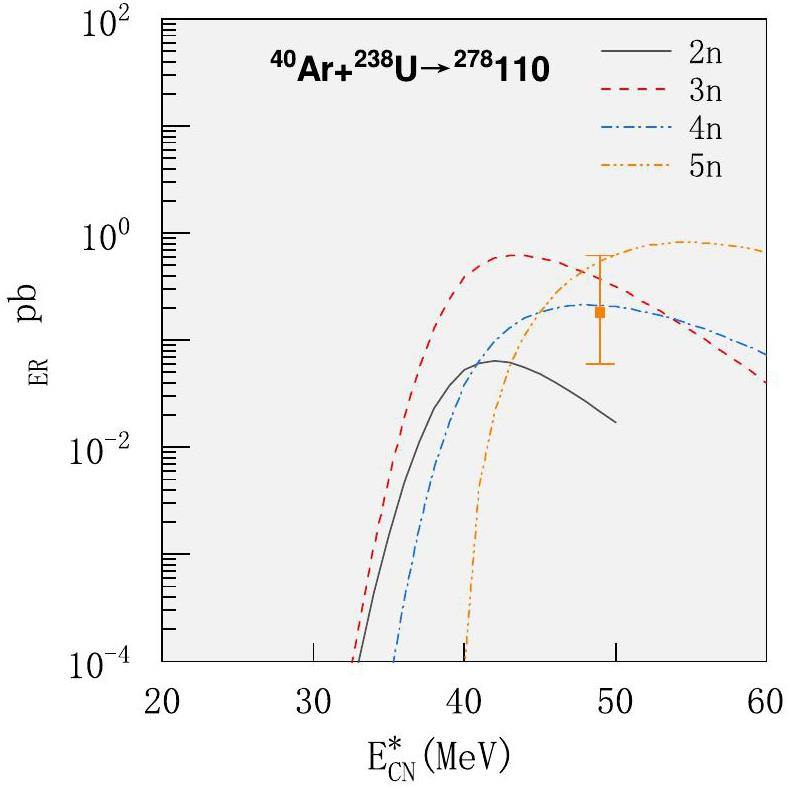

The Ds isotopes in the reaction

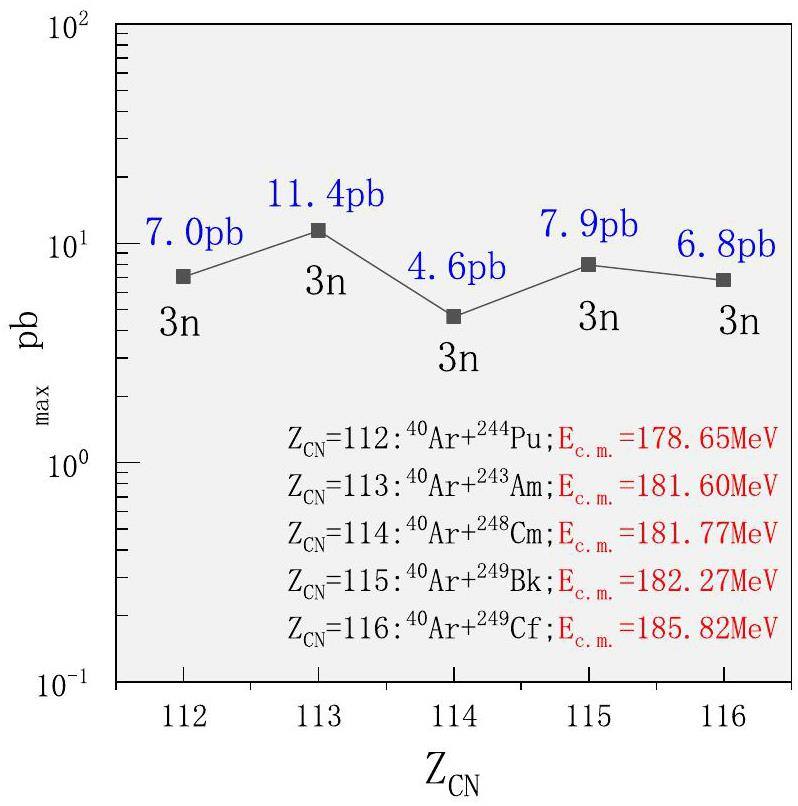

In Fig. 8, we present the maximum evaporation residue cross-sections for synthesizing SHN with

Summary

For the capture process, the ECC method effectively describes the experimental capture cross-sections in the fusion reactions for synthesizing SHN, including the sub-barrier energy region. The dynamics of the fusion process remain unclear, and certain critical parameters of the survival process, such as the fission barrier height, are uncertain. This necessitates extensive experimental and theoretical research. In this study, we conducted a systematic investigation of the synthesis of SHN Z=112 to Z=116 using 40Ar as the projectile, employing available experimental data and relatively accurate theoretical methods. This study indicated that 40Ar can be used as a projectile to synthesize Z=114 isotopes, enabling us to investigate the stability of nuclei predicted to possess the proton magic number Z=114. Additionally, 40Ar can be used as a projectile to synthesize the key nucleus 286115, which lies on the α-decay chain of the new element Z=119, aiding in the identification of the new element. We hope that this paper provides valuable insights for future experiments using 40Ar as a projectile to synthesize crucial superheavy nuclei.

Heaviest nuclei from 48Ca-induced reactions

. J. Phys. G Nucl. Part. Phys. 34,Super-heavy element research

. Rep. Prog. Phys. 78,Synthesis of a new element with atomic number Z=117

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104,Review of even element super-heavy nuclei and search for element 120

. Eur. Phys. J. A 52, 1-34 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2007-10373-xChemical characterization of element 112

. Nature 447, 72-75 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05761Independent verification of element 114 production in the 48Ca+242Pu reaction

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103,Production and decay of element 114: High cross sections and the new nucleus 277Hs

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104,Nuclear ground-state masses and deformations: FRDM(2012)

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 109–110, 1-204 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adt.2015.10.002Description of structure and properties of superheavy nuclei

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 58, 292-349 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2006.05.001Properties and synthesis of the superheavy nucleus 114298Fl

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Possibility of reaching the predicted center of the island of stability via the radioactive beam-induced fusion reactions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 161 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01542-x.Spectroscopy along flerovium decay chains: Discovery of 280Ds and an excited state in 282Cn

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126,Synthesis of superheavy nuclei in the 48Ca+244Pu reaction: 288114

. Phys. Rev. C 62,Measurements of cross sections for the fusion-evaporation reactions 244Pu(48Ca,xn)292-x114 and 245Cm(48Ca,xn)293-x116

. Phys. Rev. C 69,New superheavy element isotopes: 242Pu(48Ca,5n)285114

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105,Experiments on the synthesis of superheavy nuclei 284Fl and 285Fl in the 239,240Pu+48Ca reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 92,Measurements of cross sections and decay properties of the isotopes of elements 112, 114, and 116 produced in the fusion reactions 233,238U, 242Pu, and 248Cm+48Ca

. Phys. Rev. C 70,Investigation of 48Ca-induced reactions with 242Pu and 238U targets at the JINR Superheavy Element Factory

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Predictions of synthesizing elements with Z=119 and 120 in fusion reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Predictions of identification and production of new superheavy nuclei with Z=119 and 120

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Predictions for the synthesis of superheavy elements Z=119 and 120

. Phys. Rev. C 98,Optimal colliding energy for the synthesis of a superheavy element with Z=119

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Examination of promising reactions with 241Am and 244Cm targets for the synthesis of new superheavy elements within the dinuclear system model with a dynamical potential energy surface

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Possibilities for the synthesis of superheavy element Z=121 in fusion reactions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 95 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01452-y.Systematic study of the synthesis of heavy and superheavy nuclei in 48Ca-induced fusion-evaporation reactions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 124 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01483-5.Possibility of reaching the predicted center of the “island of stability” via the radioactive beam-induced fusion reactions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 161 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01542-x.Opportunities for production and property research of neutron-rich nuclei around N=126 at HIAF

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 97 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01454-w.Prediction of synthesis cross sections of new moscovium isotopes in fusion-evaporation reactions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 7 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01157-0.Progress in transport models of heavy-ion collisions for the synthesis of superheavy nuclei

. Nuclear Techniques 46, 137-145 (2023). https://doi.org/10.11889/j.0253-3219.2023.hjs.46.080014.Exploring α-decay chains and cluster radioactivities of superheavy 293-295 119 isotopes

. Eur. Phys. J. A 60, 74 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-024-01301-xAnalysis of the fusion mechanism in the synthesis of superheavy element 119 via the 54Cr+ 243Am reaction

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Systematics on production of superheavy nuclei Z= 119-122 in fusion-evaporation reactions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 103 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00946-3Stability and α decay of translead isomers and the related preformation probability of α particles

. Phys. Rev. C 108,A systematic study of alpha decay half-lives of isotones in superheavy region

. Indian J. Phys. 98, 2121-2132 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12648-023-02996-2Random forest-based prediction of decay modes and half-lives of superheavy nuclei

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 204 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01354-5.New α-Emitting Isotope 214U and Abnormal Enhancement of α-Particle Clustering in Lightest Uranium Isotopes

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126,Alpha-clustering effects in heavy nuclei

. Front. Phys. 13,Colloquium: Superheavy elements: Oganesson and beyond

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 91,Treatment of competition between complete fusion and quasifission in collisions of heavy nuclei

. Nucl. Phys. A 627, 361-378 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(97)00605-2Fusion cross sections for superheavy nuclei in the dinuclear system concept

. Nucl. Phys. A 633, 409-420 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(98)00124-9Effect of the entrance channel on the synthesis of superheavy elements

. Eur. Phys. J. A 8, 205-216 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10050-000-4509-7Measuring barriers to fusion

. Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 48, 401-461 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.nucl.48.1.401Nuclear dynamics in multinucleon transfer reactions near Coulomb barrier energies

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 29, 185 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-018-0521-y.Production of heavy neutron-rich nuclei with radioactive beams in multinucleon transfer reactions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 28, 110 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-017-0266-z.Nuclear dynamics and particle production near threshold energies in heavy-ion collisions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 29, 40 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-018-0379-z.Multinucleon transfer dynamics in nearly symmetric nuclear reactions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 31, 59 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-020-00770-1.Dynamical aspects of nucleus-nucleus collisions

. Nucl. Phys. A 391, 471-504 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(82)90621-2.Fusion by diffusion. II. Synthesis of transfermium elements in cold fusion reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 71,Low-energy collisions of heavy nuclei: dynamics of sticking, mass transfer and fusion

. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 34, 1 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1088/0954-3899/34/1/001.Model of competition between fusion and quasifission in reactions with heavy nuclei

. Nucl. Phys. A 618, 176-198 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(97)88172-9.Formation Mechanism of Super Heavy Nuclei in Heavy Ion Collisions

. Nuclear Physics Review 23, 396-398 (2006). https://doi.org/10.11804/NuclPhysRev.23.04.396.Fusion probability in heavy-ion collisions by a dinuclear-system model

. Europhys. Lett. 64, 750 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1209/epl/i2003-00622-0.Assessing theoretical uncertainties in fission barriers of superheavy nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 95,A program for coupled-channel calculations with all order couplings for heavy-ion fusion reactions

, Computer Physics Communications 123, 143-152 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-4655(99)00243-X.Production cross sections of superheavy nuclei based on dinuclear system model

. Nucl. Phys. A 771, 50-67 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2006.03.002.Nuclear Constitution and the Interpretation of Fission Phenomena

. Phys. Rev. 89, 1102-1145 (1953). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.89.1102.Synthesis of superheavy nuclei: Nucleon collectivization as a mechanism for compound nucleus formation

. Phys. Rev. C 64,Influence of nuclear basic data on the calculation of production cross sections of superheavy nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 92,Interaction Barrier in Charged-Particle Nuclear Reactions

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 31, 766-769 (1973). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.31.766.Experimental investigation of cross sections for the production of heavy and superheavy nuclei

. Eur. Phys. J. A 58, 178 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-022-00806-7.Investigation of 48Ca-induced reactions with 242Pu and 238U targets at the JINR Superheavy Element Factory

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Decay Measurement of 283Cn Produced in the 238U(48Ca, 3n) Reaction Using GARIS-II

. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 86,Synthesis and decay properties of isotopes of element 110: 273Ds and 275Ds

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Nuclidic mass formula on a spherical basis with an improved even-odd term

. Prog. Theoret. Phys. 113, 305-325 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1143/PTP.113.305.The authors declare that they have no competing interests.