Introduction

The correlation between two particles at a small relative momentum, known as femtoscopy, provides a unique method for directly probing the properties of particle emissions and subsequent final-state interactions (FSI) [1]. To qualify the strength of the correlation, the two-particle correlation function

Alternatively, with the known interaction, the spatial extent and the duration of the emission source can be investigated through the interference of identical particles (e.g., pions) [10, 11]. Such intensity interferometry in HICs is commonly known as Hanbury—Brown–Twiss analysis (HBT) [12, 13]. The range of the strong interaction between the two charged pions is expected to be approximately 0.2 fm [14], and the scattering length

Femtoscopic studies show that, in both pp and Pb-Pb collisions, the source size distinctly decreases as a function of the pair’s transverse mass mT, defined as

In addition to phenomenological models traditionally used in HICs for femtoscopic studies, such as EPOS [28], UrQMD [29-34], HIJING [35], CRAB [36] and others [37-42], CECA [43] offers a novel numerical approach to investigate the emission source. However, a comprehensive description that reasonably aligns collective flow with femtoscopy remains incomplete for pp collisions, although the former is recognized as the driving force behind the latter. It should be noted that the collective flow in pp collisions can be successfully reproduced by a multiphase transport model (AMPT) implementing subnucleon geometry, as demonstrated in recent studies [44-46]. This configuration, which incorporates the constituent-quark assumption for protons, can generate a large initial spatial eccentricity, leading to a significant long-range azimuthal correlation during pp collisions. Therefore, it is crucial and natural to further explore whether such a framework is valid for revealing space-time characteristics. This work presents the first attempt to model the correlation function, emission source, and mT-scaling in high-multiplicity pp collisions at

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we provide a short introduction to the model and key parameters. This is followed by an overview of the femtoscopic methodology, which includes the source function and framework used to provide an accurate FSI of pion pairs. In Sect. 3, the impact of various physical factors, such as the parton rescattering cross section σρ, initial partonic distribution, short-lived resonances, and hadron rescattering processes, on the emission source is examined. Most importantly, the dependence of mT on the

MODEL AND METHODOLOGY

AMPT model

The AMPT hybrid dynamic model [47, 48], which includes both partonic and hadronic scattering, has been used extensively to study various key features of HICs, such as hadron production [49, 50], collectivity [51-54] and phase transitions [55]. In recent years, this model has been extended to small systems, such as pp and p–Pb collisions [45]. AMPT consists of four key components to simulate the collision process: the initial conditions generated using the Heavy Ion Jet Interaction Generator (HIJING) model [56, 57]; the partonic interactions described by Zhang’s Parton Cascade (ZPC) model [58]; the hadronization process, which occurs through either Lund string fragmentation or a coalescence model; and the hadronic rescatterings modeled by A Relativistic Transport (ART) model [59]. The model has two versions: (1) the string-melting version, in which a partonic phase is generated from excited strings in the HIJING model and a simple quark coalescence model combines partons into hadrons, and (2) the default version, which proceeds only through a pure hadron gas phase.

This work is based on the AMPT with the string-melting configuration, incorporating subnucleon geometry when sampling the initial transverse positions of parton sources before converting them into constituent quarks (denoted by “3 quarks”). This special tuning method introduced in Ref. [44] can successfully reproduce the spectra and elliptic flows of the identified hadrons in pp collisions at TeV scale. Details of the initial partonic distribution are presented in Sec. 3. To illustrate the effects of the parton rescattering process, the value of

The high-multiplicity events in the AMPT were selected based on the number of charged particles in the pseudorapidity regions -3.7<η<-1.7 and 2.8<η<5.1 corresponding to the acceptance of the ALICE V0 detector. Additionally, an average multiplicity of approximately 30 charged particles was considered in the pseudorapidity interval |η|<0.5, following the event classification scheme used in ALICE pp collisions [61]. Using the particle selection criteria from the ALICE measurements [17], charged pions were selected in the pseudorapidity range |η|<0.8 within the transverse momentum (pT) range of 0.14-4.0 GeV/c.

The correlation function and emission source

The correlation function is expressed in Eq. (1). In this study, assuming that the emission source was identical in all spatial directions, a single scalar k* was considered instead of the general three-dimensional k*. The source function

However, for simplicity, the results of this study were based on the isotropic Gaussian source shown in Equation 2. Because of the fundamental assumptions in the Lednický parameterization [5], the effective range expansion of the scattering amplitude is not valid for small systems, particularly pp collisions [69]. Therefore, the two-particle wave function is obtained using the “Correlation Analysis Tool using the Schrödinger Equation” (CATS) framework [70], which numerically solves the Schrödinger equation for a configurable interaction potential. In this study, the phase space of the charged particles (positions and momenta) is provided by the AMPT model, whereas the CATS framework is used to accurately account for the FSI of the pairs to construct the

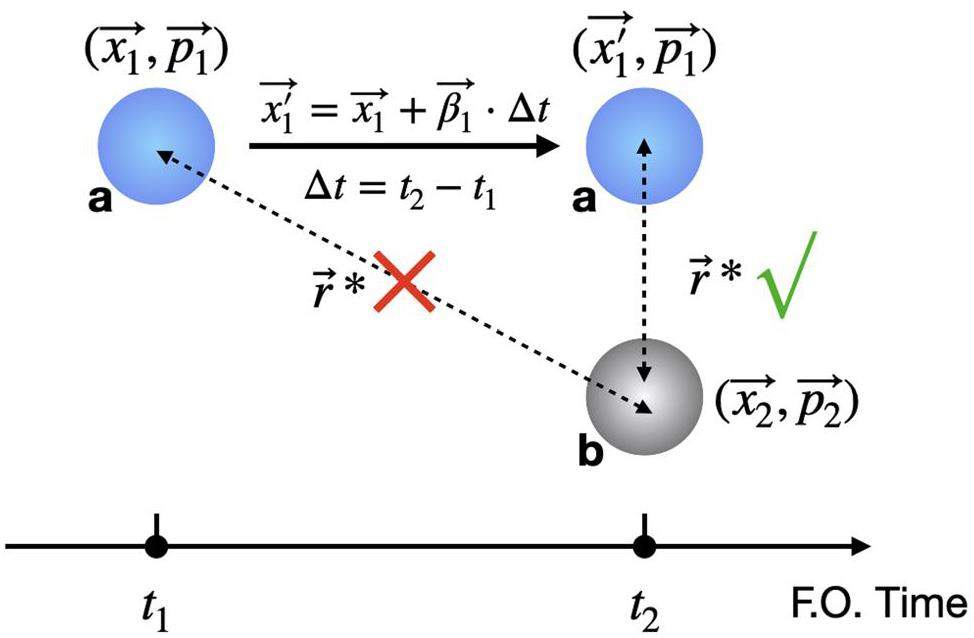

With a time step of 0.2 fm/c in the AMPT computational framework, the particle generated earlier must propagate along its momentum for the time difference between the pair to satisfy the equal emission time condition, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Consider a pair of particles labeled a and b. The particle a, represented as a blue disk, is emitted at freeze-out (F.O.) time t1 with position and momentum

results and discussion

Effect of initial partonic distribution

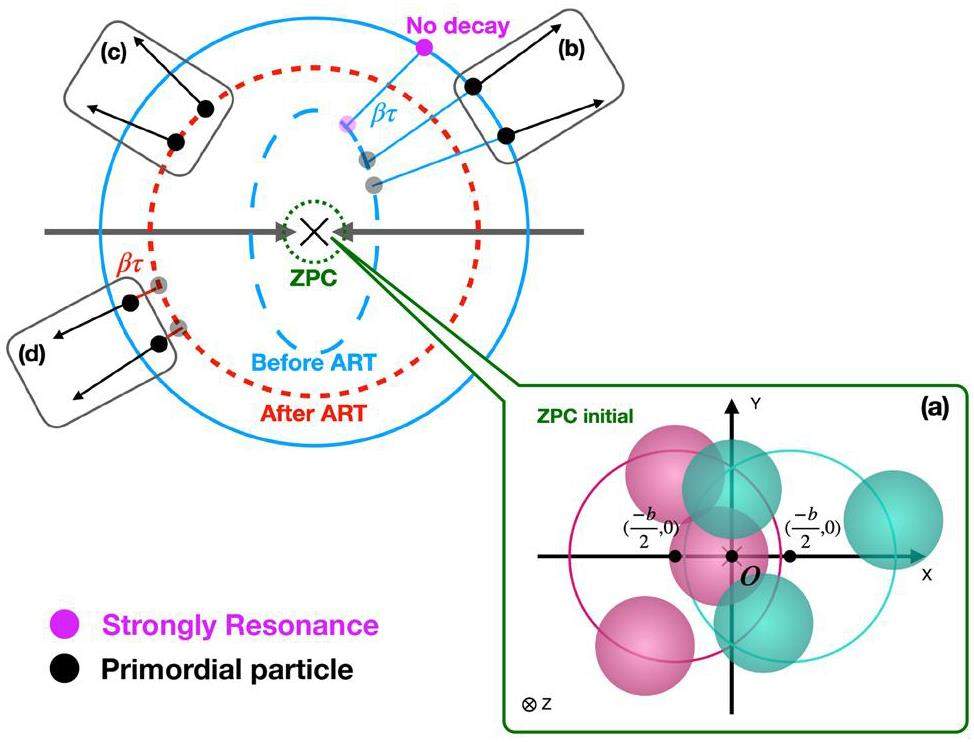

The initial partonic distribution during the ZPC stage played a crucial role in determining the source function. To investigate this effect, three initial partonic patterns were considered, as shown in panel (a) of Fig. 2. Partons can be generated from (1) the overlapping area of the quarks (colored disks) inside the protons [44], mimicking the constituent-quark scenario, and (2) three fixed black points along the impact parameter direction b, corresponding to the centers of two colliding protons and the center of the impact parameter. In the model coordinate system, these are located at

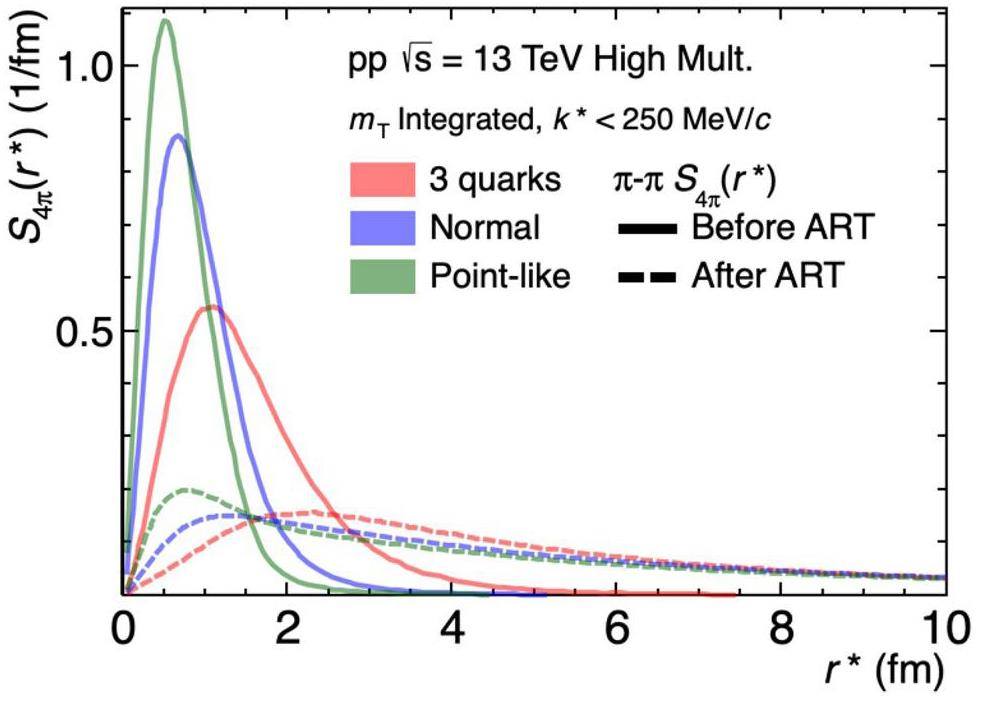

In Fig. 3, the mT integrated source functions of the

Fitting source function in different kT intervals

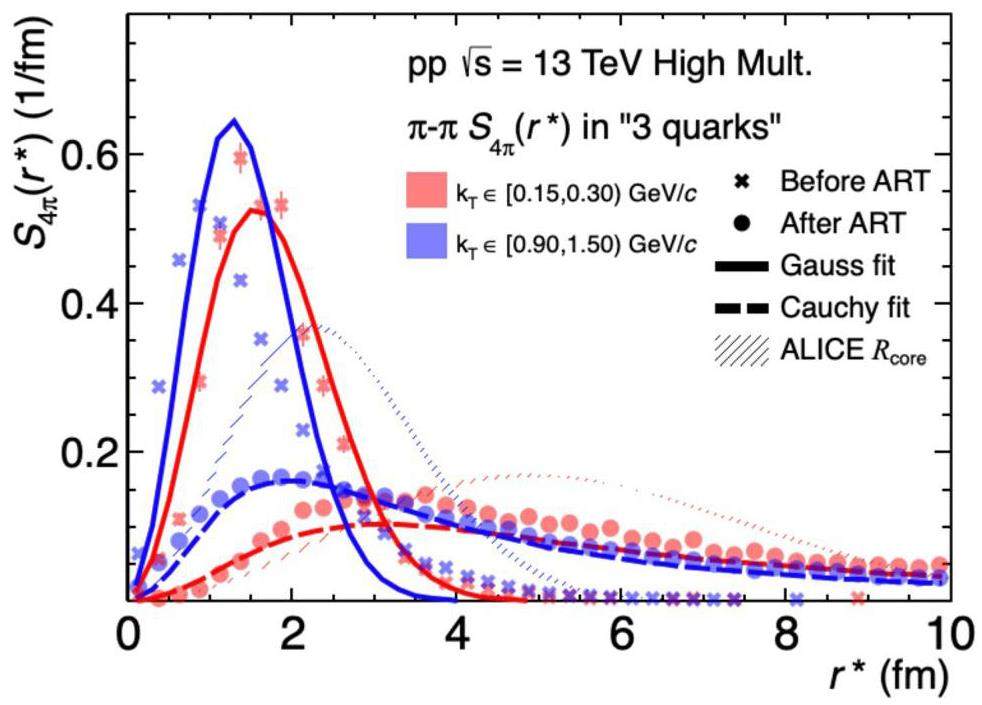

The correlation function is commonly divided into mT intervals to ensure a consistent number of pairs in the femtoscopic signal region (e.g., k* < 250 MeV/c). Here, the

Gaussian and Cauchy source functions were used to fit the source distributions before and after the ART stage at two kT intervals, represented by the solid and dashed lines, respectively. This fitting yields the radii

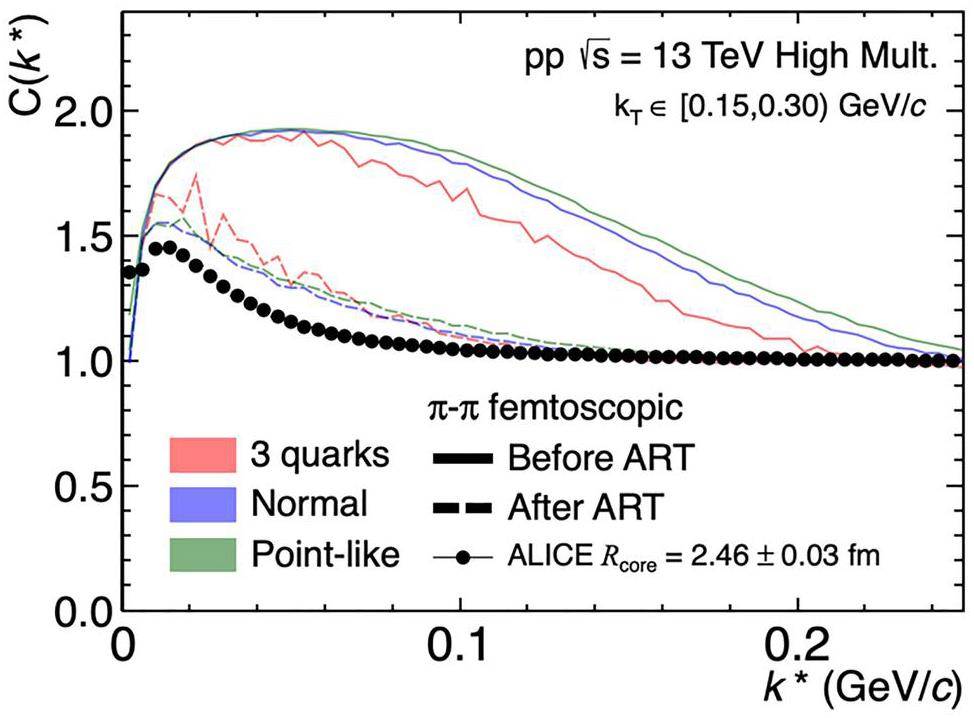

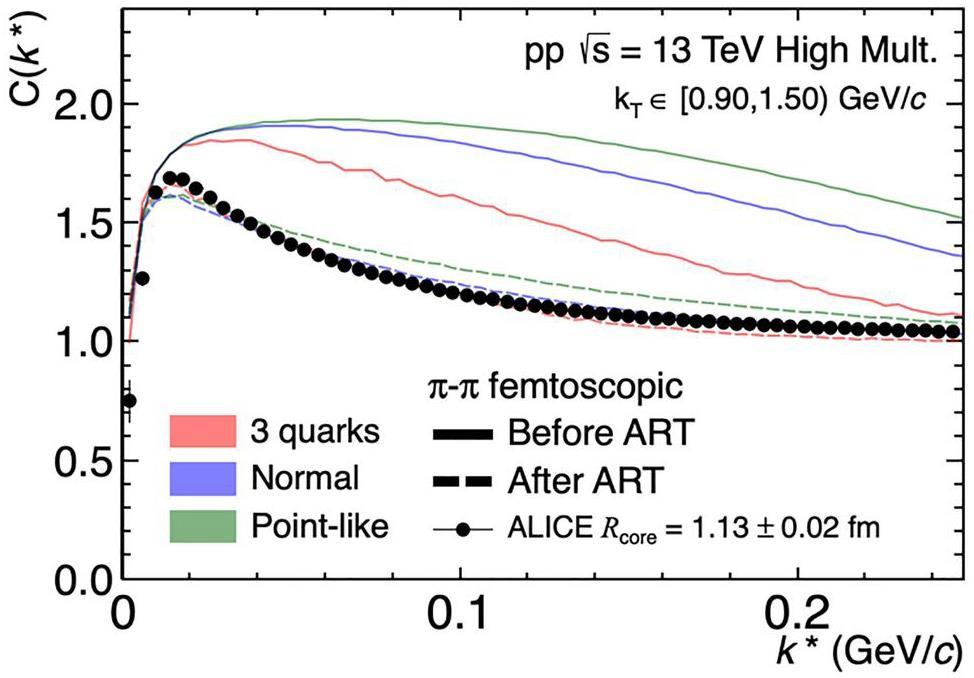

To understand the impact of the source on the final correlation function, the simulation results are presented for three different initial partonic distributions before and after the ART stage using the aforementioned source functions and the accurate two-particle wave function from CATS [70]. The results are presented in Fig. 5 and Fig. 6 correspond to two examples kT-intervals.

It can be observed that the correlation functions after the ART stage approximate the experimental data to a certain extent. By contrast, because the source distribution before the ART stage was concentrated in the small

Impact of parton scattering cross section on the source function

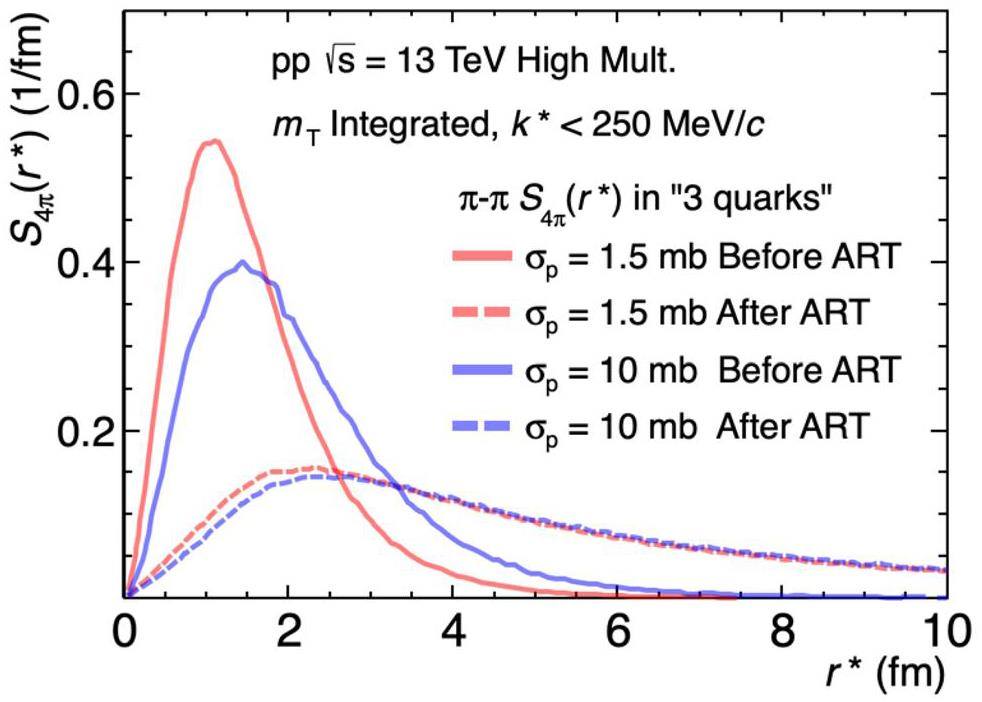

In addition to the initial position of the parton, the parton scattering cross section σρ, which reflects the probability of two partons interacting, also affects the source and final correlation functions, as previously discussed in Ref. [38]. In Fig. 7, the source function for the “3 quarks” scenario is presented for σρ = 1.5 mb and 10 mb. It was observed that σρ significantly affected the source function before the ART stage. The results were similar for the other two initial partonic distributions. As σρ increases, the probability of two-parton interactions increases, leading to a more dispersed parton and hadron distribution and, consequently, a wider source function. However, the results after the ART are almost unaffected by σρ, indicating that the hadronic process plays a decisive role. Most of the initial effects were smeared or masked by hadronic scattering and resonance decay, which are discussed in the following section.

Impact of resonance and hadronic scattering on the source function

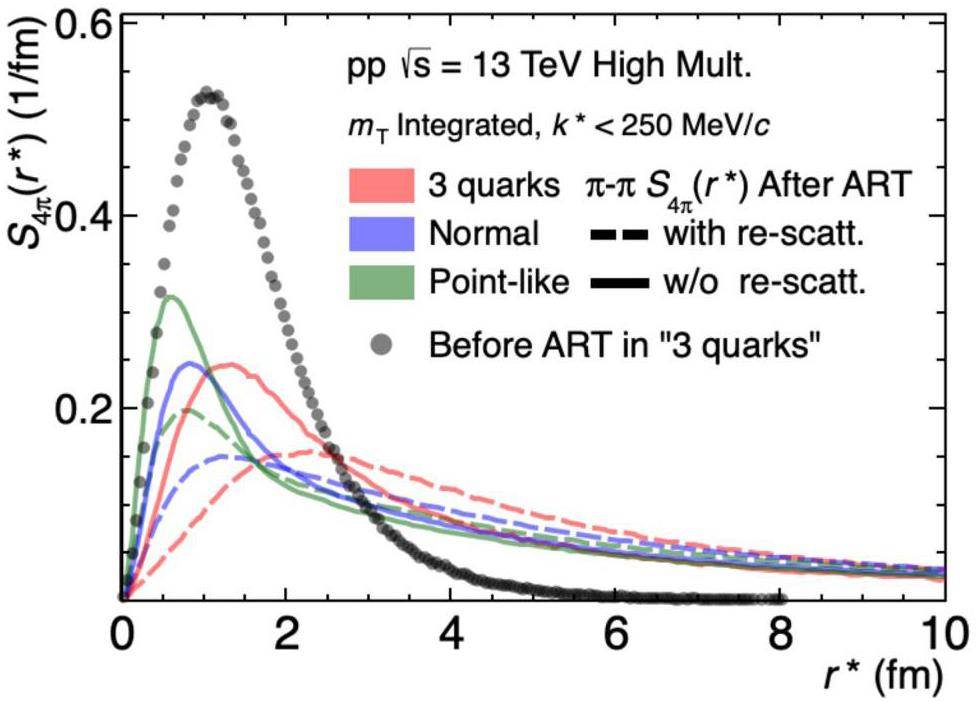

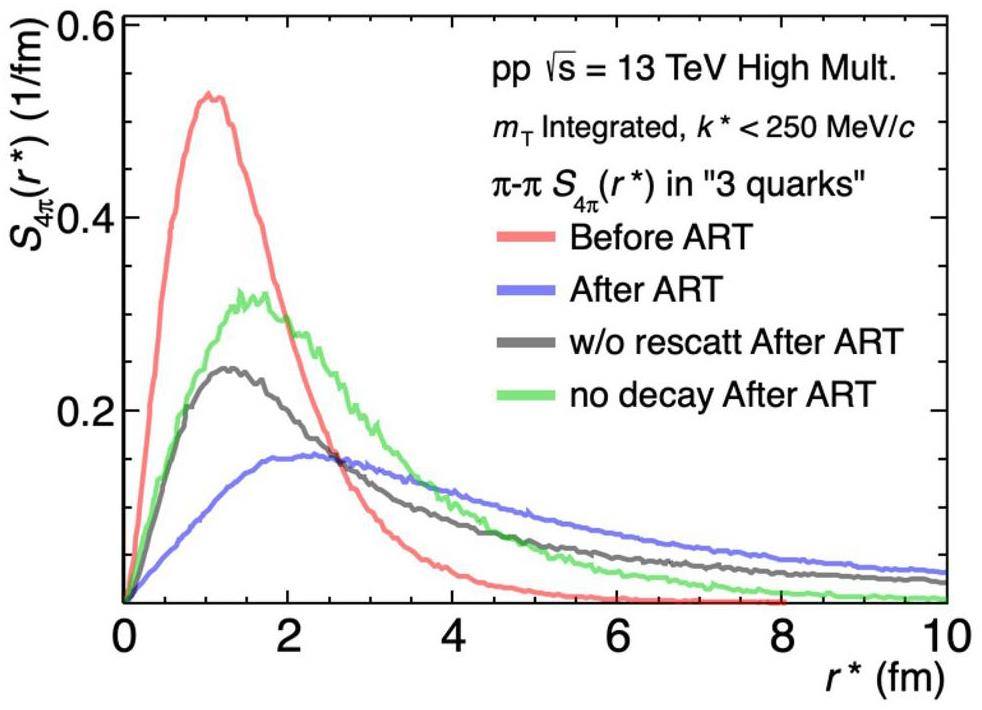

The hadronic interaction in AMPT and ART is dominated by two mechanisms: short-lived strongly decaying resonances and hadronic rescattering, including both elastic and inelastic processes. In Fig. 8 compared to the case where rescattering is turned off, the r* distribution is wider when rescattering is on for all three initial conditions. This agrees with the expectation that the generated hadrons undergo adequate hadronic scattering, causing the entire system to expand outward. The long tail persists even when rescattering is off, suggesting a contribution from resonance decay.

As mentioned in Sect. 2, the source function has two main components: primordial particles produced in collisions, which are well described by a Gaussian distribution with width

In the SHM calculation, only the decay products of short-lived resonances that contributed at least 1% were considered. As shown in Tab. 1, 28% of the charged pions are primordial, whereas 72% originate from resonance. However, in AMPT, several decay channels are not included, leading to a different fraction compared to the SHM calculation. There are ongoing efforts to incorporate production and annihilation channels into the ART stage [72], and a more thorough description of the resonances remains to be explored. Despite the differences in the resonance components and fractions, the qualitative impact of FSIs on the source is shown in Fig. 9. Four scenarios were investigated: before ART, after ART, after ART without the rescattering process, and after ART without resonance decay but with hadronic rescattering. The total ART contribution (blue) can be decomposed into the resonance (black) and hadronic rescattering (green) components. When no resonances contribute to the pions (green), the tail of the relative source function is significantly shorter than that of the gray function, which extends up to 30 fm.

| SHM Fraction(%) | “3 quarks” Fraction(%) | |

|---|---|---|

| primordial | 28.0 | 46.3 |

| strong resonances | 72.0 | 53.7 |

| Resonances | ||

| 9.0 | 6.8 | |

| 8.7 | 13.9 | |

| ω(782) | 7.7 | 6.2 |

| 2.3 | 4.3 | |

| 2.6 | 4.2 | |

| 1.9 | - | |

| 1.5 | - | |

| η | 1.5 | 19.9 |

| 1.4 | - | |

| 1.4 | - | |

| 1.4 | - | |

| 1.2 | - |

Final source function and -scaling

In principle, the standard method for subtracting the resonance contribution from the total source function and extracting Rcore follows Eq. (4) in Ref. [18], which employs Gaussian fitting of

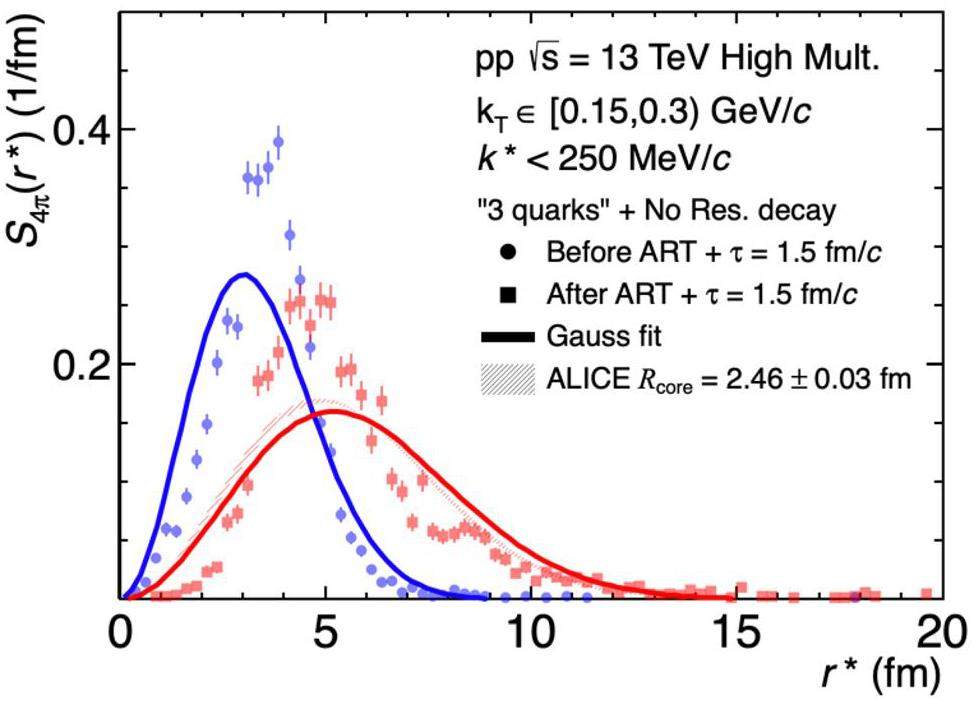

In the present study, we employed an alternative method. A schematic representation of the space-time dynamics is shown in Fig 2. Collisions with a given initial distribution (panel a) first proceed through the ZPC stage (green dashed circles). After the coalescence process, hadrons are formed (blue dashed circles), representing the stage before ART. To understand the core source function, the default resonance decays in the ART are fully turned off, and their contributions are excluded, matching the original definition of the core source and scenario described in Ref. [43]. Subsequently, the emission time parameter τ is introduced. The generated hadrons are forced to travel along their original momentum directions for τ fm/c without any hadronic interactions, resulting in an increase in the core source radii by

Figure 10 shows the r* distribution (dots) and fitting results using Gaussians (lines) in the kT interval of 0.15–0.3 GeV/c. The emission time parameter τ=1.5 fm/c was computed using the weighted abundances and lifetimes of the resonances considered in Ref. [17]. As expected, the average radius after ART (red) was larger than that before ART (blue). The fittings worked approximately despite minor inaccuracies. Notably, the results after ART were highly compatible with the ALICE results [17], indicating the validity of the model.

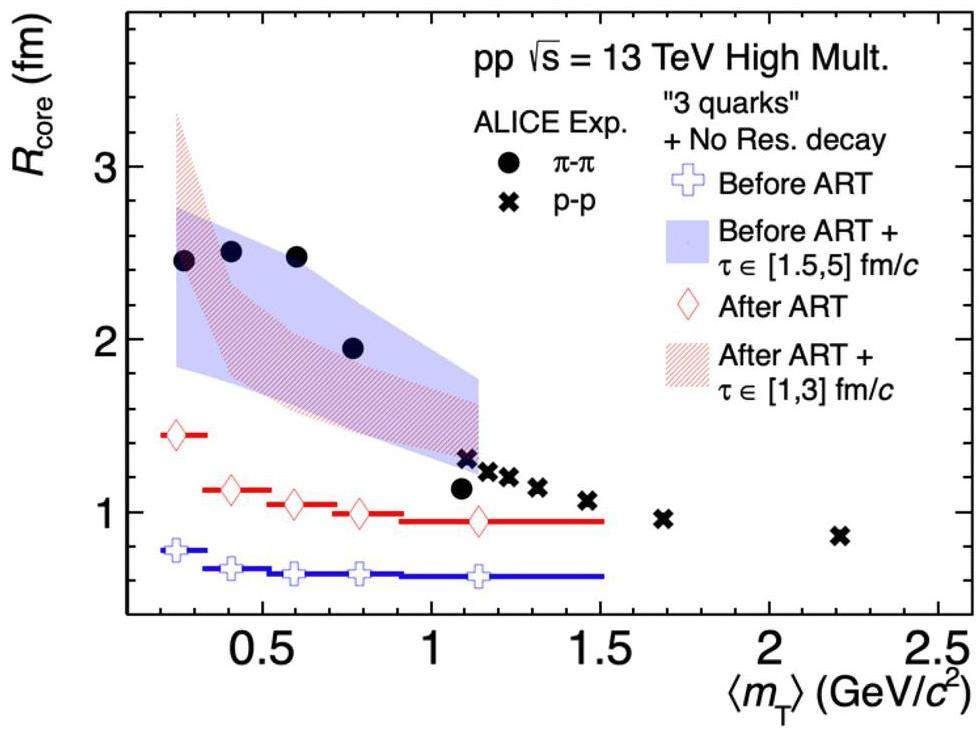

Based on the fitting results, the Rcore values in each kT interval are extracted for four different scenarios: (i) before ART without further boost, (ii) before ART with a boost of

summary

This study investigated the pion emission source in high-multiplicity pp collisions at

In future studies, the resonance decay channels in the ART should be updated. The relationship between the radial (anisotropic) flow and the source function must be quantified. Studies on other particle species (e.g., p-p and K-p pairs) and source functions in multiple dimensions would also be valuable for a better understanding of experimental measurements.

Femtoscopy in relativistic heavy ion collisions

. Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 55, 357-402 (2005). arXiv:nucl-ex/0505014, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.nucl.55.090704.151533Study of the strong interaction among hadrons with correlations at the LHC

. Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 71, 377-402 (2021). arXiv:2012.09806, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nucl-102419-034438Consistent histories and the interpretation of Aip Conf Proc

. J. Stat. Phys. 36, 219-272 (1984).Final State Interaction Effect on Pairing Correlations Between Particles with Small Relative Momenta

. Sov. J. Nucl. Phys. 35, 770 (1982). [Yad. Fiz.35,1316(1981)]Finite-size effect on two-particle production in continuous and discrete spectrum

. Phys. Part. Nuclei 40, 307-352 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1063779609030034Measurement of interaction between antiprotons

. Nature 527, 345-348 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15724One-dimensional pion, kaon, and proton femtoscopy in Pb–Pb collisions at sNN=2.76 TeV

. Phys. Rev. C 92,Measuring Ks0K± interactions using Pb–Pb collisions at sNN=2.76 TeV

. Phys. Lett. B 774, 64-77 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2017.09.009Kaon–proton strong interaction at low relative momentum via femtoscopy in Pb–Pb collisions at the LHC

. Phys. Lett. B 822,Pion interferometry of nuclear collisions. I. Theory

. Phys. Rev. C. 20, 2267 (1979).Pion interferometry and intermittency in heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. D 44, 704-716 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.44.704Two-pion Bose-Einstein correlations in pp collisions at s=900 GeV

. Phys. Rev. D 82,Two-pion Bose–Einstein correlations in central Pb–Pb collisions at sNN=2.76 TeV

. Phys. Lett. B 696, 328-337 (2011).Extended sources, final state interactions and Bose-Einstein correlations

. Zeitschrift für Physik C Aip Conf Proc 39, 81-88 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01560395ππ scattering

. Nucl. Phys. B 603, 125-179 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1016/s0550-3213(01)00147-xEffective range expansion for the pion-pion system

. Phys. Lett. B 123, 452-454 (1983). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(83)90992-9Common femtoscopic hadron-emission source in pp collisions at the LHC

. (2023). arXiv:2311.14527 https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.14527Search for a common baryon source in high-multiplicity pp collisions at the LHC

. Phys. Lett. B 811,Pion, kaon, and proton femtoscopy in Pb–Pb collisions at sNN=2.76 TeV modeled in (3+1)D hydrodynamics

. Phys. Rev. C 90,Pion-kaon femtoscopy in Pb-Pb collisions at sNN=2.76 TeV modeled in (3+1)D hydrodynamics coupled to Therminator 2 and the effect of delayed kaon emission

. Phys. Rev. C 98,Bulk observables in Pb–Pb collisions at sNN=5.02 TeV at the CERN Large Hadron Collider within the integrated hydrokinetic model

. Phys. Rev. C 100,Femtoscopy correlations of kaons in Pb–Pb collisions at LHC within hydrokinetic model

. Nucl. Phys. A. 929, 1-8 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2014.05.003THERMINATOR 2: THERMal heavy IoN generATOR 2

. Comput. Phys. Commun. 183, 746-773 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2011.11.018Investigations of anisotropic flow using multiparticle azimuthal correlations in pp, p–Pb, Xe–Xe, and Pb–Pb collisions at the LHC

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123,Emergence of long-range angular correlations in low-multiplicity proton-proton collisions

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132,ALICE Collaboration, Observation of partonic flow in proton-proton and proton-nucleus collisions

. (2024). arXiv:2411.09323 https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.09323Probing partonic collectivity in pp and p–Pb collisions with ALICE., talk given at IS2023

(2023) https://indico.cern.ch/event/1043736/contributions/5363771/EPOS LHC: Test of collective hadronization with data measured at the CERN Large Hadron Collider

. Phys. Rev. C 92,Relativistic hadron-hadron collisions in the ultra-relativistic quantum molecular dynamics model

. Journal of Physics G: Nuclear and Particle Physics 25, 1859-1896 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1088/0954-3899/25/9/308Microscopic models for ultrarelativistic heavy ion collisions

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 41, 255-369 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/s0146-6410(98)00058-1Effects of a phase transition on two-pion interferometry in heavy ion collisions at sNN=2.4−7.7 GeV

. Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy 66,Transport model analysis of the pion interferometry in Au+Au collisions at Ebeam=1.23 GeV/nucleon

. Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy 66,Azimuthal-sensitive three-dimensional HBT radius in Au-Au collisions at Ebeam=1.23 AGeV by the IQMD model

. The Eur. Phys. J. A. 58, 81 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-022-00722-wSimulation of collective flow of protons and deuterons in Au+Au collisions at Ebeam=1.23 AGeV with the isospin-dependent quantum molecular dynamics model

. Phys. Rev. C. 107,Probing granular inhomogeneity of a particle-emitting source by imaging two-pion Bose-Einstein correlations

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 19 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00853-7Testing transport theories with correlation measurements

. Nucl. Phys. A. 566, 103-114 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(94)90614-9Partonic effects on pion interferometry at the relativistic heavy-ion collider

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89,. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.89.1523013D pion source functions from the AMPT model

. Journal of Physics G: Nuclear and Particle Physics 35,Collision energy dependence of source sizes for primary and secondary pions at NICA energies

. (2024). arXiv:2401.00619 https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.00619Investigating the pion source function in heavy-ion collisions with the EPOS model

. Vol. 36, (Estimation of pion-emitting source in symmetric and asymmetric collisions using the UrQMD model

. Epj Web Conf. 204, 03017 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/201920403017Modeling of two-particle femtoscopic correlations at top RHIC energy

. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 798,Novel model for particle emission in small collision systems

. The Eur. Phys. J. C. 83, 590 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-023-11774-7Investigating high energy proton proton collisions with a multi-phase transport model approach based on PYTHIA8 initial conditions

. The Eur. Phys. J. C. 81, 755 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-021-09527-5A transport model study of multiparticle cumulants in pp collisions at 13 TeV

. Phys. Lett. B 839,Disentangling the development of collective flow in high energy proton proton collisions with a multiphase transport model

. The Eur. Phys. J. C. 84, 1029 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-024-13378-1Multiphase transport model for relativistic heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 72,Further developments of a multi-phase transport model for relativistic nuclear collisions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 113 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00944-5Study of baryon number transport dynamics and strangeness conservation effects using Ω-hadron correlations

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 120 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01464-8Explore the QCD phase transition phenomena from a multiphase transport model

. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 62, 11012 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11433-018-9272-4Investigating the elliptic anisotropy of identified particles in p-Pb collisions with a multi-phase transport model

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 32 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01387-4Charm hadron azimuthal angular correlations in Au+Au collisions at sNN=200 GeV from parton scatterings

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 30, 185 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-019-0706-zCalculation of momentum correlation functions between π, K, and p for several heavy-ion collision systems at sNN=39 GeV

. Phys. Rev. C. 109,Effects of α-clustering structure on nuclear reaction and relativistic heavy-ion collisions

. Nuclear Techniques 46, 80001 (2024). https://doi.org/10.11889/j.0253-3219.2023.hjs.46.080001Transport model study of conserved charge fluctuations and QCD phase transition in heavy-ion collisions

. Nuclear Techniques 46,HIJING: A Monte Carlo model for multiple jet production in pp, pA and AA collisions

. Phys. Rev. D 44, 3501-3516 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.44.3501Hijing 1.0: A monte carlo program for parton and particle production in high energy hadronic and nuclear collisions

. Comp. Phys. Commun. 83, 307-331 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-4655(94)90057-4Zpc 1.0.1: a parton cascade for ultrarelativistic heavy ion collisions

. Comp. Phys. Commun. 109, 193-206 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-4655(98)00010-1Formation of superdense hadronic matter in high energy heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 52, 2037-2063 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.52.2037Improved quark coalescence for a multi-phase transport model

. Phys. Rev. C. 96,Unveiling the strong interaction among hadrons at the LHC

. Nature 588, 232-238 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-3001-6Bose-Einstein correlations for systems with large halo

. Zeitschrift für Physik C: Aip Conf Proc 71, 491-497 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02907008Bose-Einstein correlations of charged hadrons in proton-proton collisions at s=13 TeV

. J. High Energy Phys. 2020, 14 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/jhep03(2020)014Two-particle Bose-Einstein correlations in pp collisions at s=0.9 and 7 TeV measured with the ATLAS detector

. The Eur. Phys. J. C. 75, 466 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-015-3644-xBose-Einstein correlations in pp, p–Pb, and Pb–Pb collisions at sNN=0.9-7 TeV

. Phys. Rev. C 97,Bose-Einstein correlations for Lévy stable source distributions

. The Eur. Phys. J. C. - Aip Conf Proc 36, 67-78 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s2004-01870-9Femtoscopy of pp collisions at s=0.9 and 7 TeV at the LHC with two-pion Bose-Einstein correlations

. Phys. Rev. D 84,Two-pion Bose-Einstein correlations in central Pb–Pb collisions at sNN=2.76 TeV

. Phys. Lett. B 696, 328-337 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2010.12.053Exploring the strong interaction of three-body systems at the LHC

. Phys. Rev. X 14,A femtoscopic correlation analysis tool using the Schrödinger equation (CATS)

. The Eur. Phys. J. C. 78, 394 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-018-5859-0Deuteron production and elliptic flow in relativistic heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 80,Yu-Gang Ma is the editor-in-chief for Nuclear Science and Techniques and was not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.