Introduction

Nondestructive detection techniques are widely used to measure the tritium content and its distribution. Tritium nondestructive detection techniques mainly include β particle counting [1], elastic backscattering spectrometry (EBS) [2], calorimetry [3], imaging plate analysis [4], and β decay-induced X-ray spectroscopy (BIXS) [5-11]. β particle counting and imaging plate analysis can only provide information on the surface distribution of tritium, while calorimetry can only determine the total tritium content; none of these methods can obtain tritium depth profiles. In contrast, EBS can obtain tritium depth profiles and tritium contents but requires large equipment, such as an accelerator. BIXS measures tritium depth profiles and tritium content by detecting X-rays produced by electrons resulting from tritium β decay in materials. This method has several notable advantages, including a large detection depth, nondestructive testing capabilities, and ease of operation [12]. BIXS analysis methods can be classified into analytical BIXS method [5] and Monte Carlo (MC)-based methods [9]. The analytical method proposed by Matsuyama [5] in 1998 was based on empirical formulas and did not consider the complicated transport processes of electrons and photons in materials. However, MC BIXS, introduced by An et al. [9], uses Monte Carlo simulations (i.e., the PENELOPE code [13]) to model the tritium β-decay X-ray spectra and combines the simulated and experimental spectra to obtain tritium depth profiles and contents [14, 15]. Although MC BIXS is more accurate owing to its consideration of the complex geometry and electron and photon transport in materials, it is time-consuming and requires sufficient statistical accuracy in the simulated X-ray spectra. Therefore, we developed a semianalytical BIXS method that combines MC simulations with analytical calculations [16]. This approach offers a 73 times improvement in computational efficiency compared to MC BIXS and simultaneously maintains high accuracy, for example, the difference in tritium content obtained by the semi-analytical BIXS and MC BIXS for the same tritium-containing sample was only 0.82% [16].

For thin solid tritium-containing samples with substrates, which were the type of samples often encountered in the application of BIXS [14, 15], the present BIXS methods required prior knowledge of the thickness of the sample, and the details of the BIXS analysis have been described in Refs [14, 15]. The sample thickness needed in BIXS analysis is often obtained by weighing during sample preparation or by EBS. Currently, in the practical application of BIXS for sample testing, a need has been proposed by the BIXS user; that is, without prior knowledge of the sample’s thickness, the tritium content and sample thickness can be obtained simultaneously using BIXS for a thin solid tritium-containing sample with a substrate.

In some cases, a good linear relationship between tritium content and X-ray intensities can be obtained [17, 18]; for example, Matsuyama et al. discovered that the intensities of characteristic X-rays

The backpropagation (BP) neural network developed by Rumelhart et al. [30] is a specific implementation of an ANN, particularly for training multilayer feed-forward networks. It consists of an input layer, hidden layers, and an output layer, with the neurons in each layer fully connected only to adjacent neurons. The simple structure and stability of a BP neural network render it effective for high-precision nonlinear fitting [31-35]. BP networks have been successfully applied to tasks, such as simple classification [36], neutron spectrum resolution [37], nuclide identification [38], and pulse shape discrimination [39]. Most recently, Zhao et al. [40] used a BP neural network to reconstruct tritium depth profiles in materials in a simulation study of BIXS, with the analysis depth limited to 20 μm for a sample of 1 mm thick (i.e., equivalent to a semi-infinite sample).

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the methods used in this work, including the construction of the tritium β-decay X-ray spectra for BP network training and the construction process of the BP network. Section 3 presents and discusses the results, including the detailed optimization process, test, and generalizability of the BIXS BP network. The application of the BIXS BP network to experimental X-ray spectra is discussed. Finally, Sect. 4 concludes the paper.

Methods

Semi-Analytical BIXS X-ray Spectrum

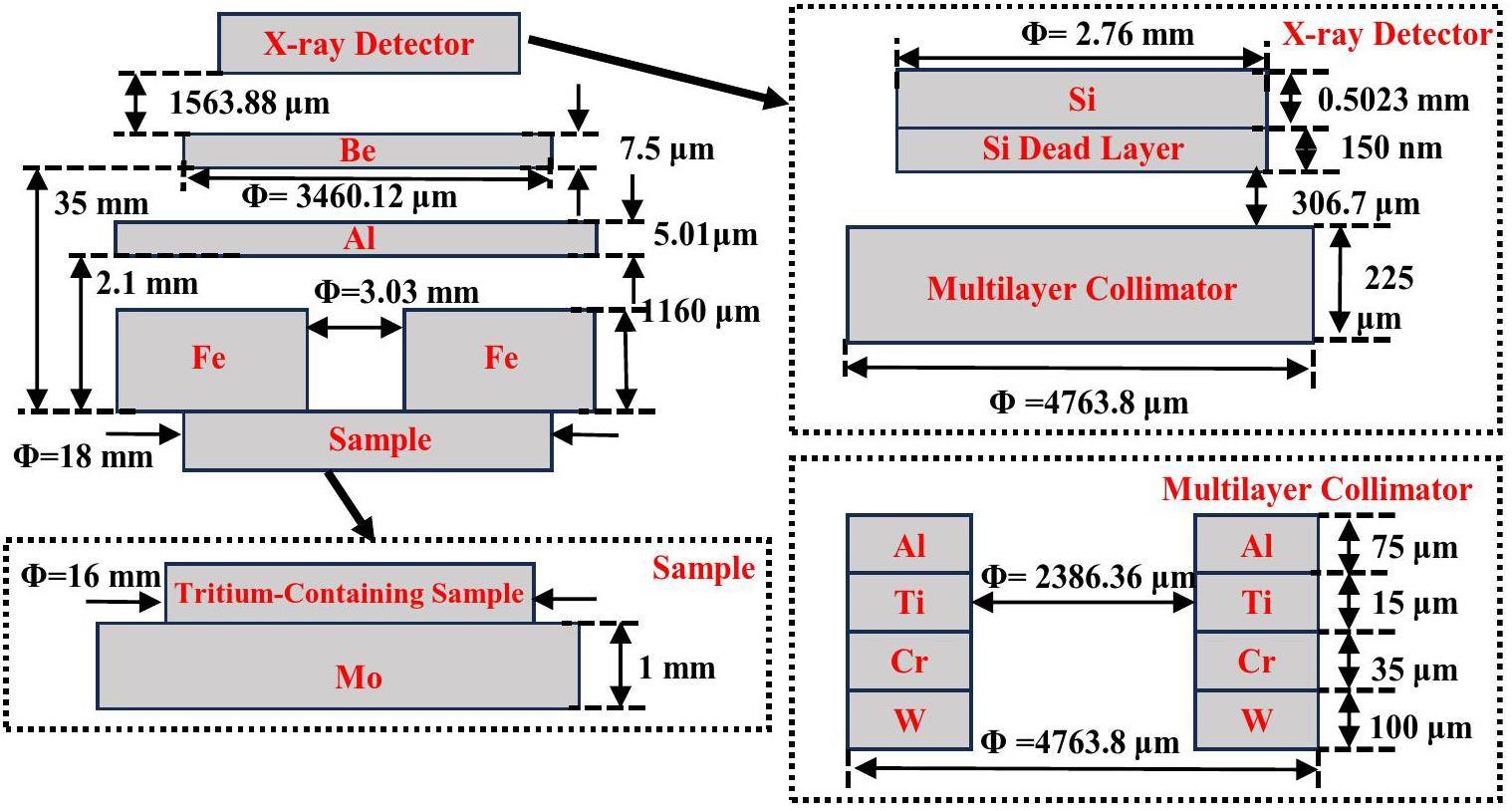

A large dataset of BIXS spectra is required to train the ANN, including the X-ray spectra induced by electrons from β decays of tritium in the sample, corresponding tritium depth profiles, and sample thicknesses. In this study, the semi-analytical model developed in Ref. [16] for calculating the X-ray spectrum of tritium-containing sample was employed to generate the dataset. The experimental setup of the BIXS, based on a silicon drift detector (SDD), is shown in Figure 1 and identical to the setup described in detail in [16]. A 5.01 μm-thick aluminum film was used as the β-ray stopping layer, and tritium-containing samples (i.e., zirconium films in this study) were supported by 1 mm-thick molybdenum substrates.

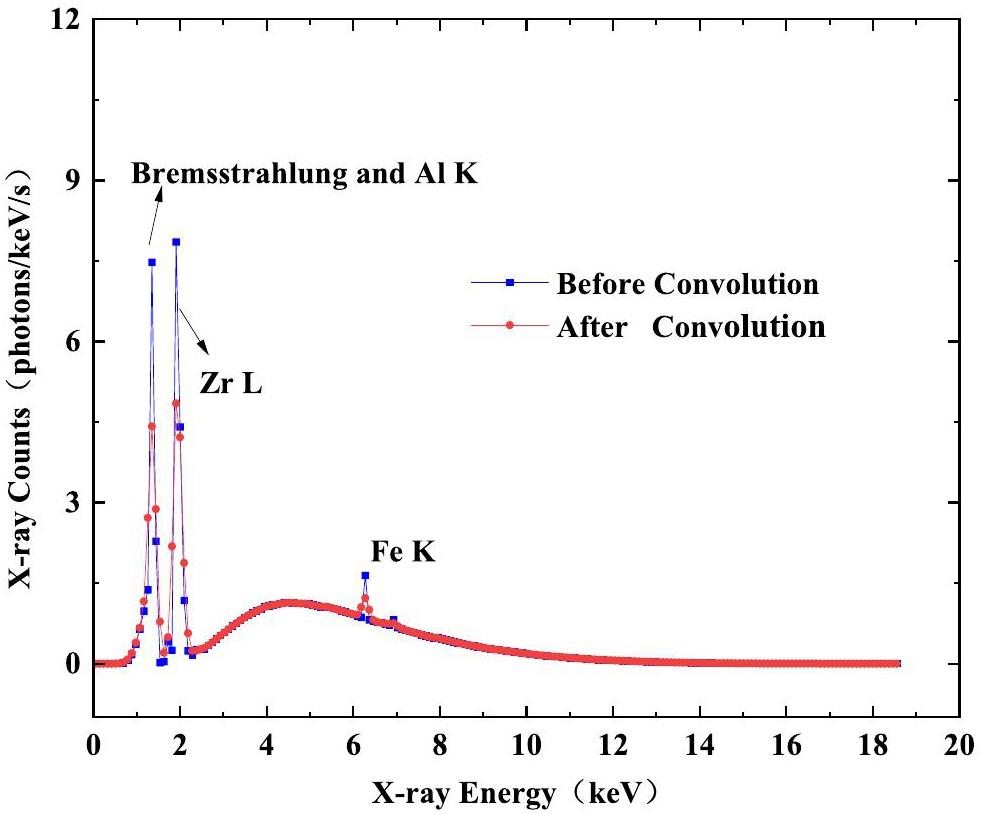

To calculate the X-ray spectrum of the tritium-containing sample using the semi-analytical model, internal bremsstrahlung (IB), external bremsstrahlung (EB), and characteristic X-rays were considered. The detailed calculation process is described in Refs. [16], and a brief description is provided here. The total X-ray fluence, which is the differential in the photon energy k per β electron from tritium decay per solid angle, can be expressed by the following formula [16]:

Construction of BP Network Dataset

A total of 420 tritium-containing zirconium samples of different thicknesses and tritium-to-zirconium ratios were used to generate a dataset of tritium β-decay X-ray spectra. The zirconium thicknesses before absorbing tritium ranged between 3 μm and 5 μm, with the assumption that tritium was uniformly distributed throughout the sample. The zirconium thickness was divided into 21 groups with an interval of 0.1 μm, whereas the tritium-to-zirconium ratio ranged from 0.1 to 2, divided into 20 groups with an interval of 0.1. The time required by the semi-analytical method to obtain a tritium β-decay X-ray spectrum for each combination of sample thickness and tritium-to-zirconium ratio was approximately 1 h [16]. Thus, the total time required to obtain 420 X-ray spectra is approximately 19 d [16]. From Ref. [16], it is noted that the semi-analytical X-ray spectra were expressed in unit of “counts per keV per β decay”. To ensure consistency between the semi-analytical and experimental spectra, the unit of the semi-analytical spectra was converted to the unit of the experimental spectra, that is, counts per keV per second, based on the number of tritium atom decays, NT, within a unit time t:

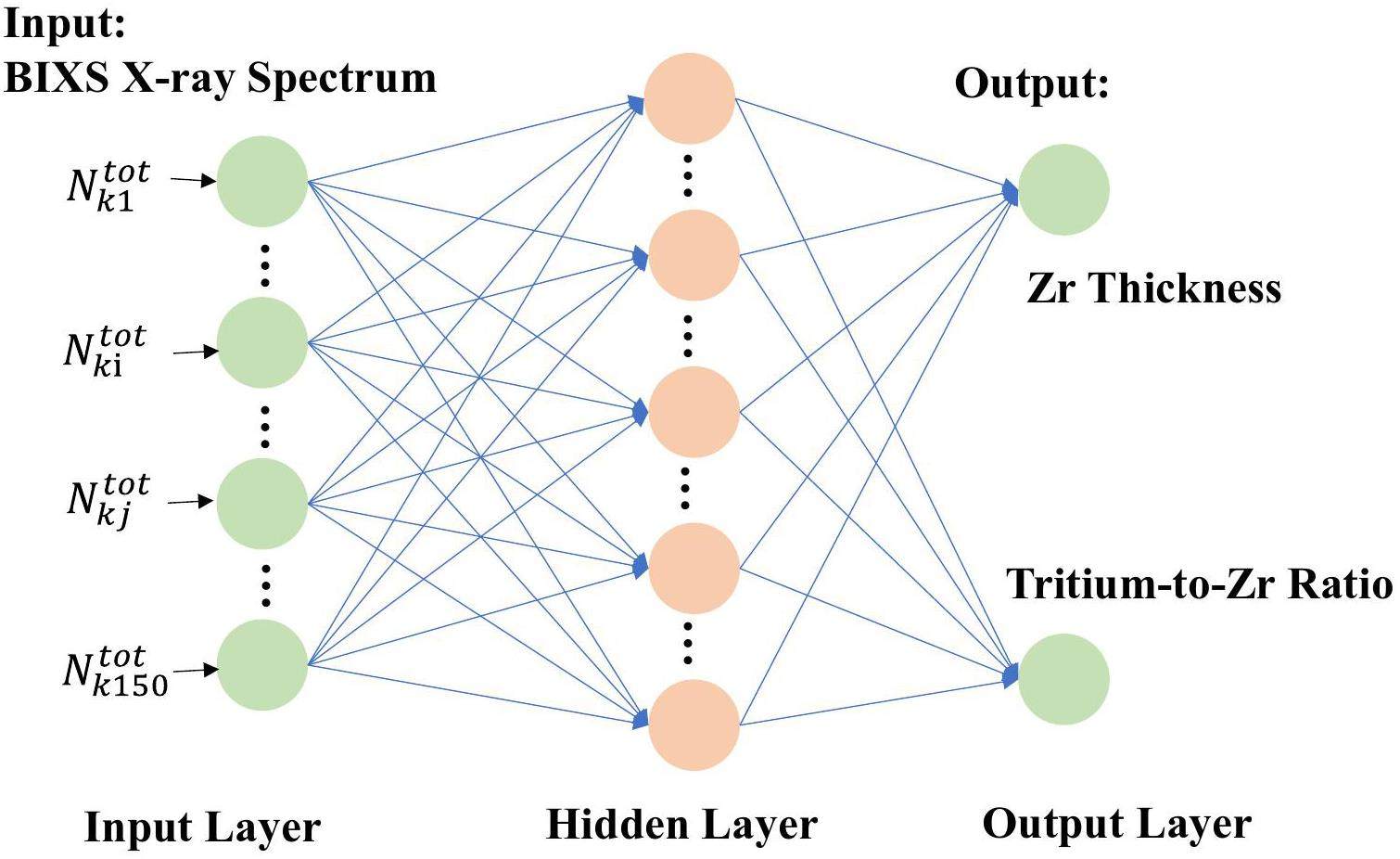

Construction of BP Network

Figure 3 illustrates the structure of a back propagation (BP) network designed to predict the zirconium thickness and tritium-to-zirconium ratio. The structure consists of three layers: input, hidden, and output layers. The number of hidden layers shown in this figure differs from that of the optimized configuration adopted for our application. Only the energy region of the X-ray spectrum between 1 keV and 15 keV was used to train the BP neural network to avoid noise in the low-energy region and poor statistics in the high-energy region of the experimental X-ray spectrum. The input layer consisted of 150 neurons, corresponding to 150 energy bins of the tritium β decay X-ray spectrum in the 1 keV–15 keV range. The output layer contains two neurons that represent the zirconium thickness and tritium-to-zirconium ratio. To enhance the accuracy and computational efficiency of the neural network model, a scaling transformation of the input and output data were performed [26], and the β-decay X-ray spectra were treated as follows:

The network was implemented and trained in Python 3.7 using the PyTorch library [48], with the error back-propagation algorithm employed for training. The mean squared error (MSE) [49] was used as the loss function, which was commonly used in regression tasks. It is calculated by summing the squared differences between the predicted and true values.

Results and discussion

Optimization of BP Network Structure

To select the optimal network structure, the numbers of hidden layers and neurons were optimized. To achieve nonlinear transformations, the ReLU activation function [51] was used for all the hidden layers. Table 1 shows the MSEs as functions of the numbers of hidden layers and neurons. From the results in Table 1, it can be observed that when the number of neurons exceeds 10, the MSEs tend to decrease as the number of hidden layers and neurons increases. When the number of hidden layers was between 2 and 10, and the number of neurons was between 30 and 150, the MSEs of the neural network for predicting the zirconium target thickness and tritium-to-zirconium ratio became small, ranging from approximately 5.99E-6 to 7.75E-5.

| Hidden Layers | Number of Neurons | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 30 | 50 | 70 | 100 | 150 | ||

| Training | 1 | 7.43×10-3 | 4.75×10-4 | 3.82×10-4 | 2.59×10-4 | 1.68×10-4 | 1.15×10-4 |

| 2 | 4.43×10-4 | 7.75×10-5 | 4.53×10-5 | 3.48×10-5 | 2.48×10-5 | 2.18×10-5 | |

| 3 | 5.57×10-3 | 3.64×10-5 | 1.79×10-5 | 1.74×10-5 | 1.36×10-5 | 1.02×10-5 | |

| 5 | 6.56×10-5 | 1.80×10-5 | 1.26×10-5 | 6.83×10-6 | 6.54×10-6 | 4.06×10-6 | |

| 7 | 9.48×10-5 | 1.44×10-5 | 9.07×10-6 | 8.35×10-6 | 8.54×10-6 | 6.40×10-6 | |

| 10 | 1.88×10-3 | 1.31×10-5 | 1.91×10-5 | 3.74×10-5 | 3.74×10-5 | 1.28×10-5 | |

| Test | 1 | 7.07×10-3 | 4.33×10-4 | 3.28×10-4 | 2.01×10-4 | 1.23×10-4 | 8.39×10-5 |

| 2 | 3.93×10-4 | 6.04×10-5 | 3.80×10-5 | 2.74×10-5 | 1.91×10-5 | 1.73×10-5 | |

| 3 | 4.66×10-3 | 3.20×10-5 | 1.46×10-5 | 1.41×10-5 | 1.16×10-5 | 1.00×10-5 | |

| 5 | 6.61×10-5 | 1.66×10-5 | 1.08×10-5 | 5.99×10-6 | 7.70×10-6 | 6.45×10-6 | |

| 7 | 8.71×10-5 | 1.29×10-5 | 9.72×10-6 | 8.77×10-6 | 7.70×10-6 | 6.45×10-6 | |

| 10 | 2.09×10-3 | 1.21×10-5 | 2.08×10-5 | 3.23×10-5 | 3.23×10-5 | 1.16×10-5 | |

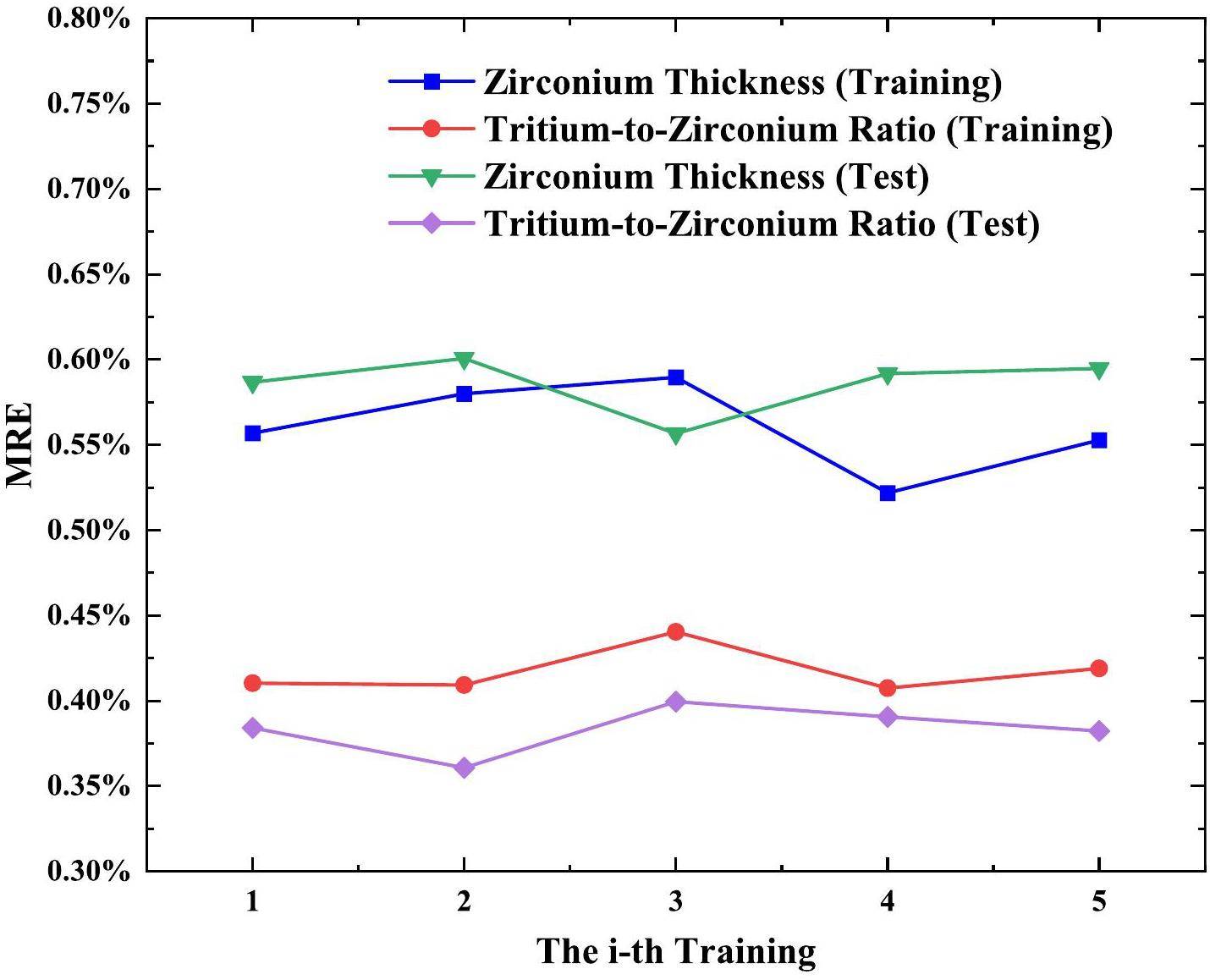

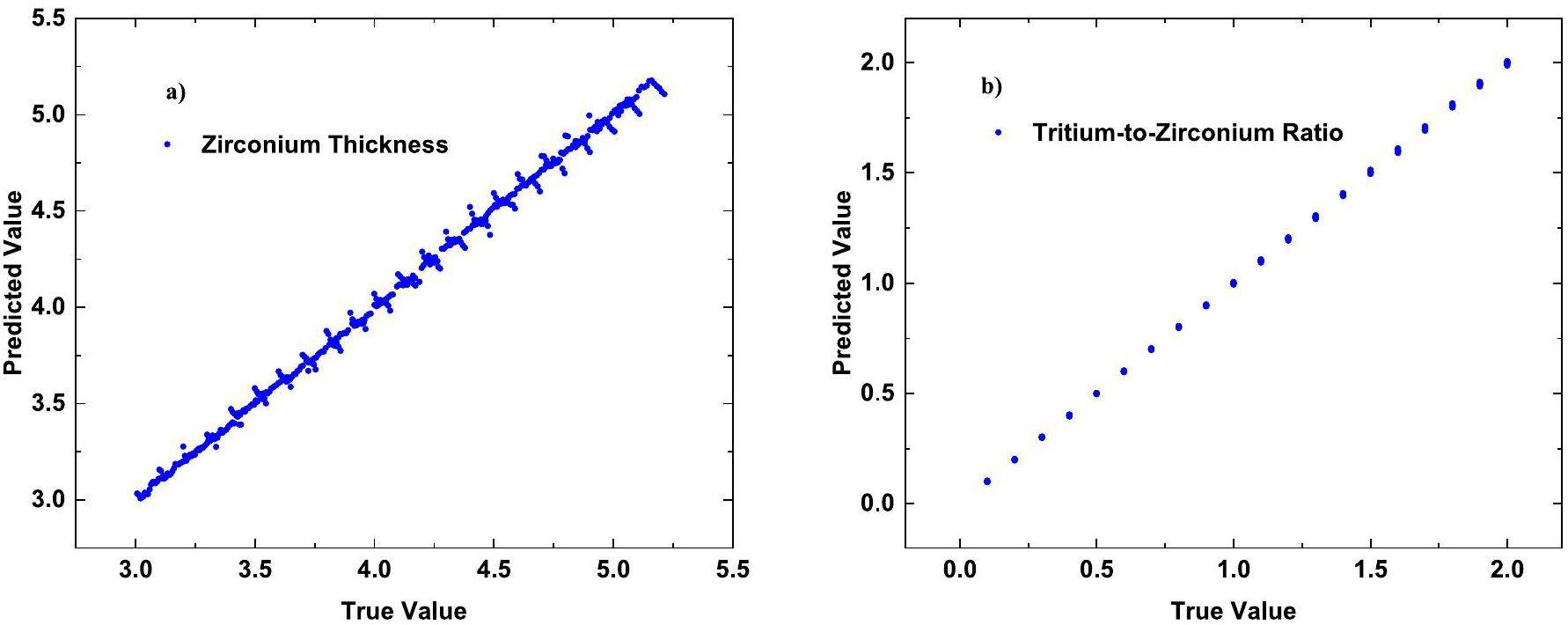

To simplify the neural-network structure while maintaining a low MSE, we selected a relatively simple five-layer neural network with three hidden layers, each containing 150 neurons. The total MSEs for the training and testing datasets were 1.02×10-5 and 1.00×10-5, respectively. The mean relative errors (MREs) [52] for the zirconium thickness and tritium-to-zirconium ratio in the training dataset of the neural network were 0.56% and 0.42%, respectively, whereas those in the test dataset, the MREs were 0.59% and 0.38%, respectively. The MRE [52] was calculated as follows:

Optimization of Activation Functions

In this study, the activation functions used in the hidden layers were optimized. To simplify the optimization process, the same activation function (i.e., ReLU [51], sigmoid [53], or tanh [54]) was applied to all the hidden layers. Table 2 shows the MSEs of the BP network for different activation functions in the hidden layers. It can be observed that the MSEs vary with the choice of activation function. We selected the activation function that resulted in the best MSE, i.e., the ReLU function. The MSEs for the training and test datasets are 1.02×10-5 and 1.00×10-5, respectively.

| Parameters | ReLU | Tanh | Sigmoid |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSE for training | 1.02×10-5 | 3.71×10-5 | 1.62×10-5 |

| MSE for test | 1.00×10-5 | 3.01×10-5 | 1.31×10-5 |

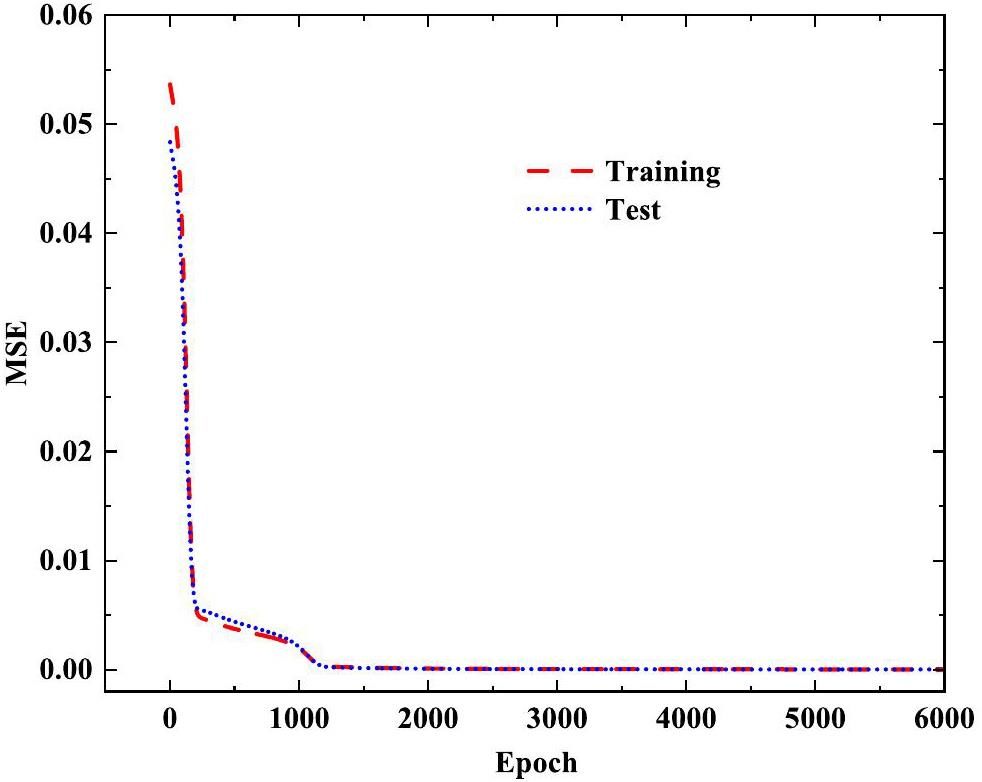

Figure 4 presents the MSEs of the BP network for both the training and test datasets as a function of the number of epochs. It can be observed that the BIXS neural network converged rapidly, with sufficient convergence achieved within 2000 iterations. Moreover, the MSEs for both datasets exhibited minimal divergence as the number of epochs increased, indicating that overfitting did not occur during training. Figure 5 presents the MREs of the training dataset and test dataset for each training period. For the tritium-to-zirconium ratio and zirconium thickness, the MRE differences obtained from each training were considerably small, indicating the good stability of the system. Figure 6 shows a comparison between the true and predicted values for the zirconium thickness and tritium-to-zirconium ratio for all 420 sets of data. Excellent predictions were obtained with the true and predicted values in close agreement. The MREs for the 420 datasets used to train and test the BP network are listed in Table 3.

| Parameters | Training | Test |

|---|---|---|

| Zirconium Thickness | 0.56% | 0.59% |

| Tritium-to-Zirconium Ratio | 0.42% | 0.38% |

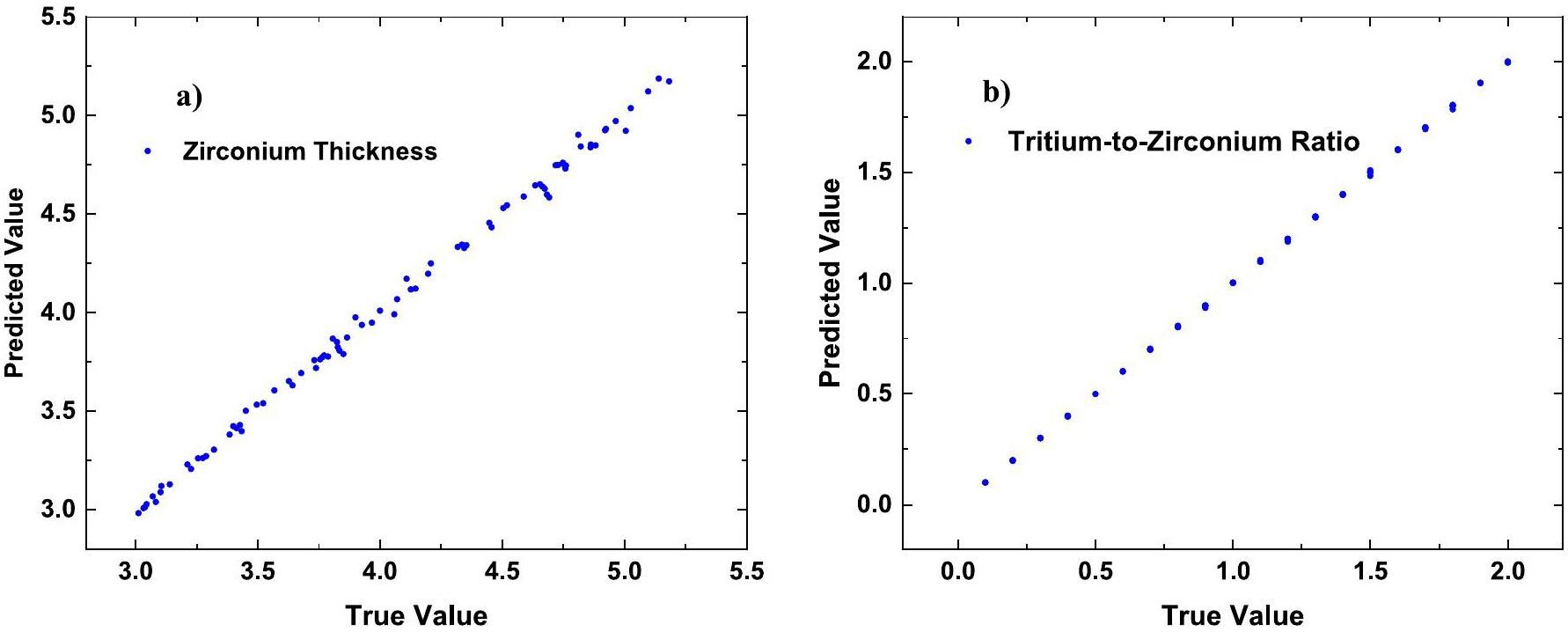

Effect of Statistical Uncertainty

The experimental BIXS X-ray spectrum may exhibit varying degrees of statistical uncertainty, which can affect the prediction accuracy. To assess the effect of statistical uncertainty, the uncertainties ranging from 0.5% to 3% were randomly with Gaussian distribution added to the 84 sets of test data of X-ray spectra, which were randomly selected from the 420 data, as described in the section “C. Construction of BP network”. Figure 7 compares the true and predicted values for the 84 sets of test data without statistical uncertainty. It can be observed that the true and predicted results are in close agreement. Table 4 lists the MREs for 84 sets of test data under different levels of uncertainty. The results demonstrate that uncertainty can affect the accuracy of neural network predictions to some extent. Generally, the greater the uncertainty, the larger the relative error in the prediction result. When the statistical uncertainty of the test set is 3%, the neural network maintains higher prediction accuracy for both zirconium thickness and the tritium-to-zirconium ratio, with average relative errors of 2.14% and 1.98%, respectively.

| Relative uncertainties (%) | Zr thickness (%) | Tritium-to-Zr ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.59 | 0.38 |

| 0.5 | 0.70 | 0.45 |

| 1 | 0.95 | 0.74 |

| 1.5 | 1.29 | 1.01 |

| 2 | 1.44 | 1.11 |

| 3 | 2.14 | 1.98 |

Generalizability of BP Network

Additional 22 sets of data, with the zirconium thicknesses outside the BP network training range from 3 μm to 5 μm, were used to preliminarily test the generalization ability of the BP neural network (i.e., the capability of extrapolation). The zirconium thicknesses and tritium-to-zirconium ratios for the 22 datasets are listed in Table 5, and the MREs of the predicted results are listed in Table 6. From Table 6, it can be observed that the BP neural network demonstrates good prediction capability, even for the dataset outside the training range. For the 22 sets of data, the MREs of the predicted zirconium thicknesses and tritium-to-zirconium ratios are 7.61% and 9.33%, respectively. For a dataset outside the training parameter range, the prediction accuracy of the neural network decreases, which is consistent with the conclusion in Ref. [27].

| Tritium-to-Zr ratio (Zirconium thickness (μm)) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.2 (1.5) | 0.5 (5.5) | 1.5 (1.5) | 1.63 (5.5) |

| 0.2 (1.7) | 0.5 (6.0) | 1.5 (1.8) | 1.63 (6.0) |

| 0.2 (2.2) | 0.5 (6.5) | 1.5 (2.0) | 1.63 (6.5) |

| 0.2 (2.4) | 0.5 (6.8) | 1.5 (2.3) | 1.63 (6.8) |

| 0.2 (2.8) | 0.5 (7.0) | 1.5 (2.5) | 1.63 (7.0) |

| 1.0 (2.5) | 1.5 (5.5) | ||

| Prediction parameters | MRE (%) |

|---|---|

| Zirconium thickness | 7.61 |

| Tritium-to-Zirconium ratio | 9.33 |

Application of BIXS BP Neural Network

Sample

Two tritium-containing samples were prepared, labeled No. 26 and No. 42, in which zirconium films were deposited onto smooth molybdenum substrates (approximately 1 mm thick) using the electron beam evaporation technique. The processes for preparing the tritium-containing samples are the same as those described in Refs.[15, 55].

The thicknesses of the zirconium films and the tritium depth profiles of samples 26 and 42 were measured using the elastic backscattering spectrometry (EBS) method. The EBS experiment was conducted using a 3 MV tandetron accelerator at Sichuan University [56]. The incident proton energy was 3 MeV with a current intensity of approximately 2 nA. The proton beams impacted the sample surface vertically, and a Si detector (ORTEC U-012-050-100) was placed at 165° with respect to the proton beam direction. The experimental details are presented in Refs.[15].

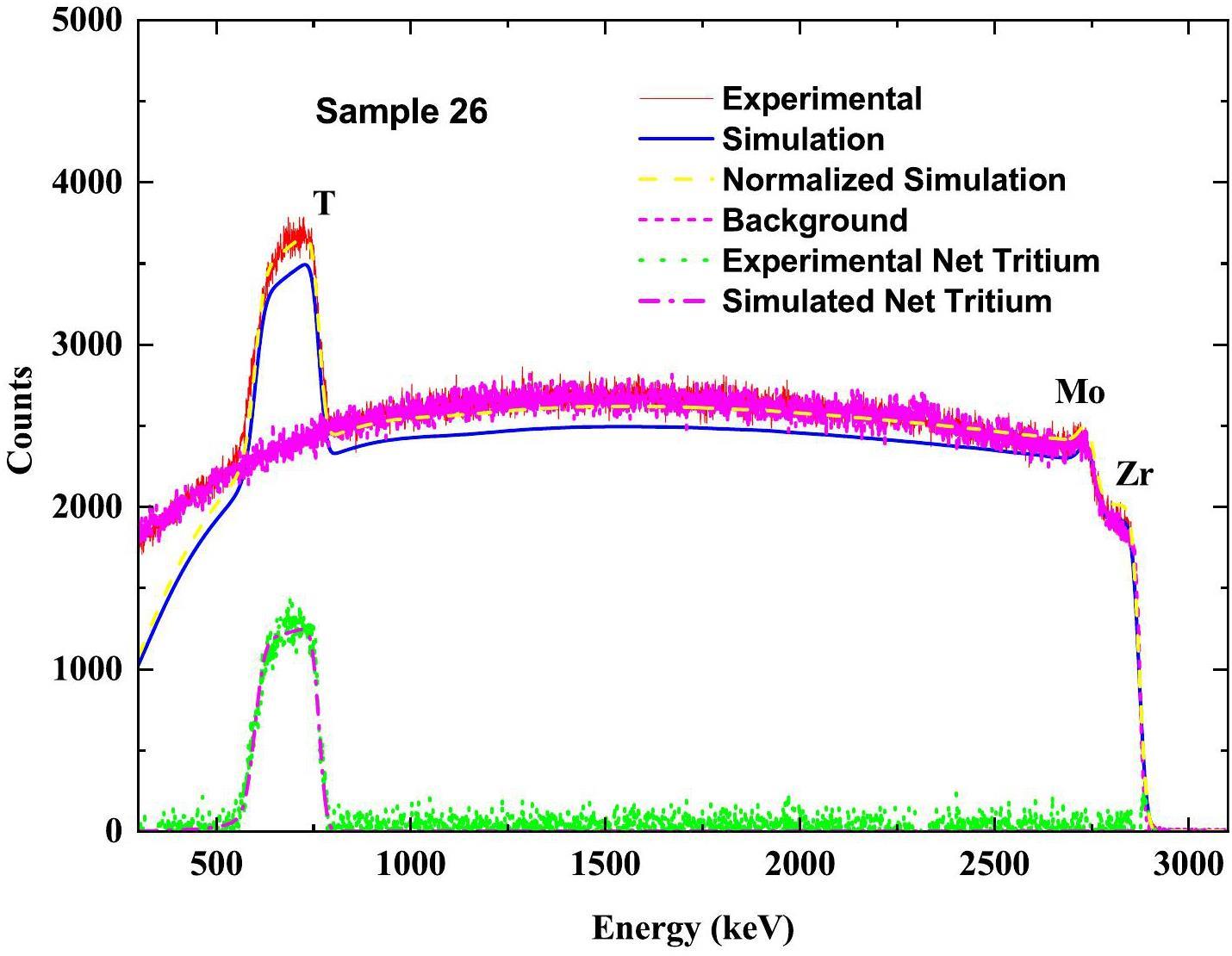

The experimental spectra of the EBS were analyzed using the SIMNRA program [57] with the same processes as in Refs.[14, 15] The parameters used in SIMNRA were consistent with those in Ref. [15]. The uncertainties for the tritium contents and zirconium thicknesses obtained using the EBS were approximately 11.7% and 5%, respectively, mainly arising from uncertainties in the proton elastic scattering cross-section data, stopping power, and statistical uncertainties [14, 15]. For example, Figure 8 shows the EBS experimental spectrum and SIMNRA simulation for sample 26, where the tritium distribution in the SIMNRA simulation was assumed to be uniform. The background spectrum was obtained by measuring a hydrogen-containing Zr film sample with a Mo substrate, whose geometric dimensions and hydrogen isotope-zirconium ratio were approximately the same as those of samples 26 and 42; the EBS experimental conditions were the same. The experimental net tritium spectrum was obtained by deducting the background spectrum from the experimental spectrum of the tritium-containing samples. The measured results are summarized in Table 7. The EBS results indicate that the tritium distributions for samples 26 and 42 were uniform.

| Samples | Parameters | EBS | BP-Network |

|---|---|---|---|

| 26 | Zirconium thickness (μm) | 1.64 | 1.60 |

| Tritium-to-Zirconium ratio | 1.87 | 1.83 | |

| 42 | Zirconium thickness (μm) | 1.72 | 1.63 |

| Tritium-to-Zirconium ratio | 1.87 | 1.89 |

Predictions of BP Network

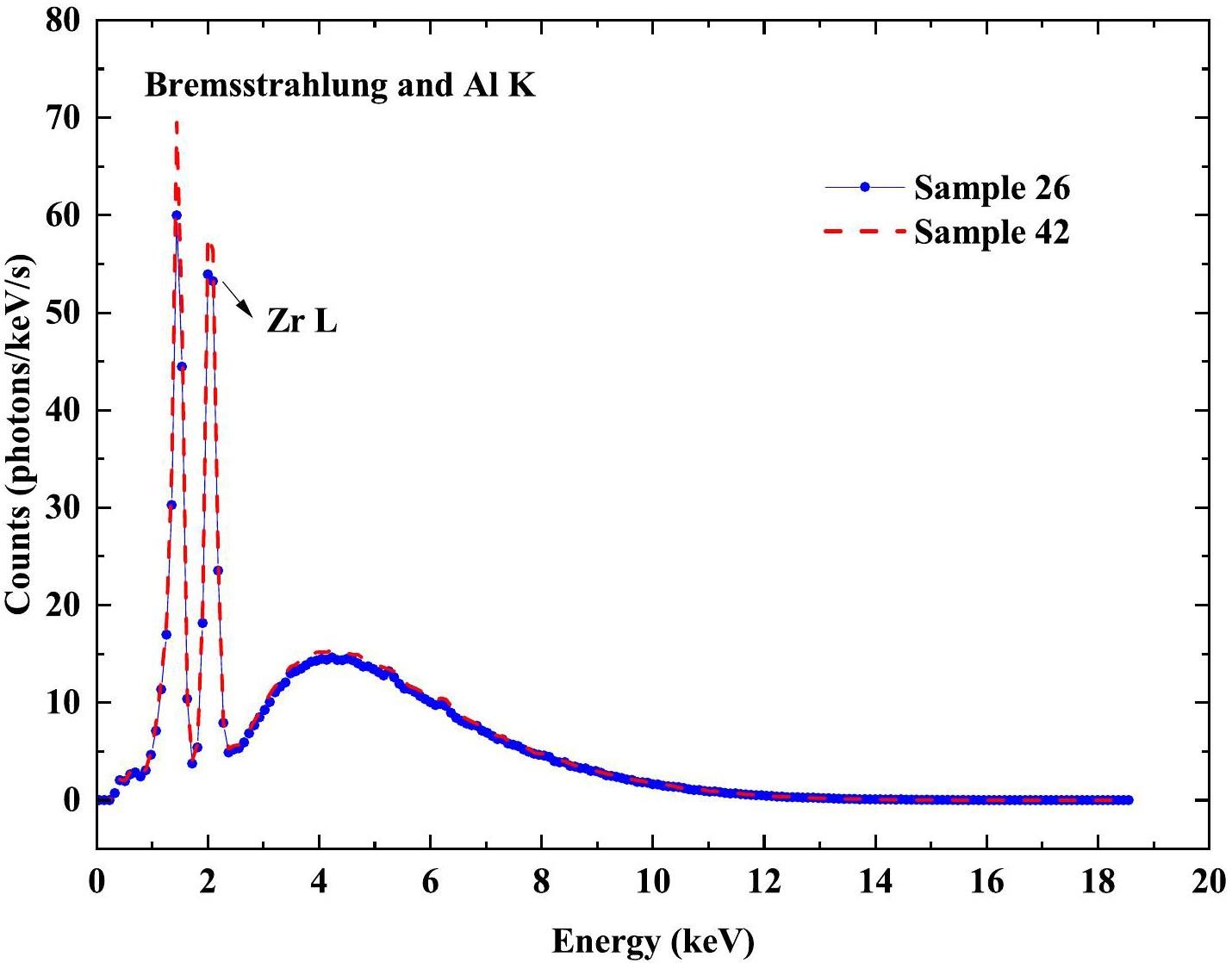

The experimental BIXS spectra of samples 26 and 42 were obtained using the same experimental setup as in Refs.[14, 15] and corrected for the signal pile-up effect by using Monte Carlo method [15], as shown in Figure 9. Corrections for the pile-up effect were less than 1%. The trained BP neural network was used to analyze the experimental BIXS spectra after correcting for the intrinsic detection efficiency of the SDD. The predicted values of the zirconium thicknesses and tritium-to-zirconium ratios are listed in Table 7. The predicted tritium-to-zirconium ratios have been converted to the tritium-to-zirconium ratios on the day of the EBS experiment.

For sample 26, the predicted zirconium thickness is 1.60 μm, which deviates by 2.43% from the EBS result, whereas for sample 42, the predicted zirconium thickness is 1.63 μm, showing a 5.23% difference compared to the EBS result. The predicted tritium-to-zirconium ratios for samples 26 and 42 are 1.83 and 1.89, with the relative deviations of 2.14% and 1.07% relative to the EBS results, respectively.

Considering that the predicted values from the BP neural network are consistent with the measured results from the EBS within experimental uncertainties, we can conclude that the BP neural network can be used to predict the thicknesses and tritium contents simultaneously with higher accuracy for thin solid tritium-containing samples with substrates and uniform tritium distribution. Previously, we employed the MC BIXS method for tritium analysis, which required prior information about the sample thickness, and its accuracy was affected by the reconstruction algorithm [9, 14, 15, 58, 59]. However, the present BIXS BP neural network approach overcomes the difficulties inherent in traditional regularization BIXS analysis methods.

Summary

In this study, an artificial neural network (ANN) algorithm was employed to predict the tritium content and thickness of thin solid tritium-containing samples with substrates and uniform tritium distributions. The semi-analytical method developed earlier for calculating the X-ray spectrum for tritium-containing samples was used to generate the dataset for training and testing the BIXS BP neural network. The neural network was optimized in several aspects, including the number of hidden layers, neurons, and activation function.

The well-trained BIXS BP neural network delivers accurate predictions for the parameters (i.e., the zirconium thickness and tritium-to-zirconium ratio) within the training range as well as demonstrates strong prediction performance outside the training range. For the thickness of zirconium, the MREs for the training dataset and test dataset are 0.56% and 0.59%, respectively. For the tritium-to-zirconium ratio, the MREs for the training dataset and test dataset are 0.42% and 0.38%, respectively. For parameters outside the training range, the MREs for the zirconium thickness and tritium-to-zirconium ratio are 7.61% and 9.33%, respectively. The trained BP neural network shows excellent predictive capability across various levels of statistical uncertainty.

The BIXS BP neural network successfully predicted the zirconium thicknesses and tritium-to-zirconium ratios from the experimental X-ray spectra obtained in BIXS experiments using two tritium-containing samples with substrates and uniform tritium distributions, which were in good agreement with the EBS results. This work demonstrates the applicability of the BP neural network in the BIXS method for analyzing thin solid samples with substrates and uniform tritium distributions without the need for prior knowledge of sample thicknesses.

In situ observation of tritium interactions with Pd and Zr by beta-ray induced X-ray spectrometry

. Fusion Eng. Des. 49, 885-891 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0920-3796(00)00326-4Tritium and helium analyses in thin films by enhanced proton backscattering

. Chin. Phys. C 38, 250-299 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1088/1674-1137/38/8/088203Tritium measurement by isothermal calorimetry

. Fusion Technol. 21, 425-429 (1992). https://doi.org/10.13182/FST92-A29782Measurement of tritium concentration in water by imaging plate

. Fusion Eng. Des. 87, 965-968 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fusengdes.2012.02.057Tritium assay in materials by the bremsstrahlung counting method

. Fusion Eng. Des. 39, 929-936 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0920-3796(98)00232-4Galet - Benchmark of a Geant4 based application for the simulation and design of beta induced X-ray spectrometry systems

. Fusion Eng. Des. 143, 91-98 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fusengdes.2019.03.086Effects of tritium 2-D distribution on tritium depth profile reconstruction in BIXS measurements

. Fusion Eng. Des. 130, 142-147 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fusengdes.2018.03.034Theoretical investigation of tritium concentration quantification method for DT fuel system using β-ray induced X-rays

. Fusion Eng. Des. 184,Reconstruction of depth distribution of tritium in materials by β-ray induced X-ray spectrometry

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 266, 3643-3646 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2008.06.020Effect of geometrical parameter’s uncertainty of BIXS experimental setup for tritium analysis

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 289, 52-55 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2012.08.005Nondestructive measurement of surface tritium by β-ray induced X-ray spectrometry (BIXS)

. J. Nucl. Mater. 290, 437-442 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3115(00)00581-XEffects of internal bremsstrahlung of tritium β-decay and surface roughness in the BIXS method

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 269, 105-110 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2010.10.024BIXS for tritium analysis with Ar gas and Al thin film as β-ray stopping layers and comparison with EBS

. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 174,Tritium analysis in zirconium film with BIXS and EBS: Generality test of Al thin film as the β-ray stopping layer in BIXS

. Fusion Eng. Des. 172,A semi-analytical model for calculating the X-ray energy spectrum of thin tritium-containing sample in BIXS analysis

. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 72, 2 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1109/TNS.2024.3523106Quantitative measurement of surface tritium by β-Ray-Induced X-Ray Spectrometry (BIXS)

. Fusion Sci. Tech. 41, 505-509 (2002). https://doi.org/10.13182/FST02-A22640New technique for non-destructive measurements of tritium in future fusion reactors

. Nucl. Fusion 47,An brief overview and introduction to artificial neural networks

. Subst. Use Misuse 37, 1093-1148 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1081/JA-120004171Predictions of nuclear charge radii based on the convolutional neural network

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 152 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01308-xA non-invasive diagnostic method of cavity detuning based on a convolutional neural network

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 94 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01069-zResearch on inversion method for complex source-term distributions based on deep neural networks

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 195 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01327-8Neutron spectrum unfolding using artificial neural network and modified least square method

. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 126, 75-84 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radphyschem.2016.05.010Artificial neural network for predicting nuclear power plant dynamic behaviors

. Nucl. Eng. Tech. 53, 3275-3285 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.net.2021.05.003Nuclear spectral analysis via artificial neural networks for waste handling

. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 42, 709-715 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1109/23.467888Processing of massive rutherford back-scattering spectrometry data by artificial neural networks

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 493, 28-34 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2021.02.010A machine learning approach to self-consistent RBS data analysis and combined uncertainty evaluation

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 551,Machine learning techniques to determine elemental concentrations from raw IBA spectra

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 546,Enhanced accuracy through machine learning-based simultaneous evaluation: a case study of RBS analysis of multinary materials

. Sci. Rep. 14, 8186 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-58265-7Learning representations by back-propagating errors

. Nature 323, 533-536 (1986). https://doi.org/10.1109/23.467888Application of a neural network model with multi-model fusion for fluorescence spectroscopy

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 10 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01528-9A machine learning approach to TCAD model calibration for MOSFET

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 12 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01340-xApproximation by superpositions of a sigmoidal function

. Math. Control Signals Syst. 2, 303-314 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02551274Determination of gamma point source efficiency based on a back-propagation neural network

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 29, 195 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-018-0410-4Multilayer feed forward networks are universal approximators

. Neural Networks 2, 359-366 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1016/0893-6080(89)90020-8A review and analysis of back propagation neural networks for classification of remotely-sensed multi-spectral imagery

. Int. J. Remote Sens. 16, 3033-3058 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1080/01431169508954607Neutron spectrometry using artificial neural networks

. Radiat. Meas. 41, 425-431 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radmeas.2005.10.003Artificial neural network algorithm for pulse shape discrimination in 2α and 2β particle surface emission rate measurements

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 41, 153 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01305-0Rapid nuclide identification algorithm based on convolutional neural network

. Ann. Nucl. Energy 133, 483-490 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anucene.2019.05.051Utilizing BP neural networks to accurately reconstruct the tritium depth profile in materials for BIXS

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 36, 15 (2025). https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.j00186.00306PENEPMA-2018, a Monte Carlo code for the simulation of x-ray emission spectra using PENELOPE

,Bremsstrahlung energy spectrum from electrons with kinetic energy 1 keV-10 GeV incident on screened nuclei and orbital electrons of neutral atoms with Z=1–100

. Atomic Data Nucl. Data Tables, 35, 345-418 (1986). https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-640X(86)90014-8A model for the energy and angular distribution of x rays emitted from an x-ray tube. Part I. Bremsstrahlung production

. Med. Phys. 47, 4763-4774 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/mp.14359Shape functions for atomic-field bremsstrahlung from electrons of kinetic energy 1–500 keV on selected neutral atoms 1<Z<92

. Atomic Data Nucl. Data Tables 28, 381-460 (1983). https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-640X(83)90001-3Emission of gamma radiation during the beta decay of nuclei

. Physica 3, 425-439 (1936). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-8914(36)80008-1On the continuous γ-radiation accompanying the β-decay

. Phys. Rev. 50, 272-278 (1936). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.50.272Bremsstrahlung of 5–25 keV electrons incident on MoSi2, TiB2 and ZrB2 thick solid conductive compounds

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 553,Weighted sum MSE minimization under per-BS power constraint for network MIMO systems

. IEEE Commun. Lett. 16, 360-363 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1109/LCOMM.2012.010512.112300Understanding AdamW through proximal methods and scale-freeness

. arXiv:2202.00089 (2022). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2202.00089Error bounds for approximations with deep ReLU networks

. Neural Networks 94, 103-114 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neunet.2017.07.002Root means square error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE): When to use them or not

. Geosci. Model Dev. Discuss. 15, 1-10 (2022). https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-15-5481-2022The influence of the sigmoid function parameters on the speed of backpropagation learning

. Int. Workshop Artif. Neural Networks, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 930, 195-201 (1995).Extended tanh-function method and its applications to nonlinear equations

. Phys. Lett. A 277, 212-218 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9601(00)00725-8Depth profiles of D and T in Metal-hydride films up to large depth

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 371, 174-177 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2015.11.030An ion beam facility based on a 3 MV tandetron accelerator in Sichuan University

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 418, 68-73 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2018.01.002SIMNRA User’s Guide, Report IPP 9/133

,Comparison of reconstruction methods of depth distribution of tritium in materials based on BIXS

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 267, 1852-1855 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2009.02.066.Tritium analysis in titanium films by the BIXS method

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 275, 20-23 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2012.01.003.Zhu An is an editorial board member for Nuclear Science and Techniques and was not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.