Introduction

As chip manufacturers strive to produce increasingly smaller and more powerful devices, extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography has become essential in the industry [1-4]. EUV light enables the creation of intricately small patterns on silicon wafers, which form the basis for integrated circuits. Currently, EUV lithography relies predominantly on laser-produced plasma (LPP) as the light source [5]. Although LPP serves as a basis for sub-5 nm node production, it has several limitations that hinder its further advancement. These include an extremely low energy conversion efficiency, with less than 1% of the laser energy being transformed into usable EUV radiation, and tin debris contamination of optical components, which imposes a cost burden owing to frequent cleaning or replacement [2].

Plans for next-generation coherent EUV sources based on free-electron laser (FEL) technologies are being developed to replace current incoherent LPP-based systems. For example, KEK has proposed an energy recovery linac free-electron laser (ERL-FEL) system [6]. Operating at a frequency of 162.5 MHz with an average current of 10 mA, this system provides EUV radiation at a wavelength of 13.5 nm with an output power greater than 10 kW. Based on the superconducting synchrotron microbunching (SSMB) concept, Tsinghua University, along with Pohang (Korea) and other institutions, is developing EUV sources [7-9]. These proposals rely on magnetic undulators. However, other approaches that do not depend on magnetic undulators are also in development.

FELs that use optical undulators have been proposed for many years [10]; however, progress has been limited. One of the main challenges is the insufficient gain length [11]. A key issue with optical undulators is that focusing is often used to increase the light intensity, which reduces the gain length. However, if loose focusing is used to increase the interaction region between the electrons and photons (thus increasing the gain length), the light intensity decreases. This dilemma can be addressed using the flying focus method [12-14]. In this approach, the light field is modulated and sequentially focused at different spatial positions over time. Essentially, at any given moment, the focus is at a small spatial region, and at the next moment, the focus shifts to another region, as if the focus flies across the space. This dynamic focusing technique allows the beam to maintain its intensity while significantly increasing its gain length [15].

The flying focus technique can achieve a focus distance of several centimeters [11] compared with the traditional focus distance of several tens of micrometers, significantly improving the gain length without sacrificing light intensity. This breakthrough can help overcome one of the major limitations of optical undulators in FELs. It has been estimated that an EUV source with an output power of up to 1 MW can be achieved using this approach [11], marking a major advancement in the development of high-power EUV sources for applications such as semiconductor lithography.

However, generating a flying focus remains a challenge. Various approaches have been proposed, including the use of Kerr lenses [16]. However, the nonlinear properties of Kerr lenses can lead to instability. Recently, axiparabolas have been used in high-intensity laser plasma applications and to generate flying foci [17-20]. In this study, the use of a specialized axiparabola, stretched off-axis paraboloid (sOAP), is investigated to produce coherent EUV light through Compton scattering. Instead of a conventional flying focus, a structured flying focus or flying focus train can be generated using a sOAP.

In the following sections, the optical properties of the sOAP and the theory of coherent Compton scattering are first described. Next, the proposed setup utilizing a tilted pulse laser, sOAP, and flying focus train is introduced. Finally, the EUV light yield of the proposed configuration is evaluated.

Stretched Off-axis Paraboloid Mirror

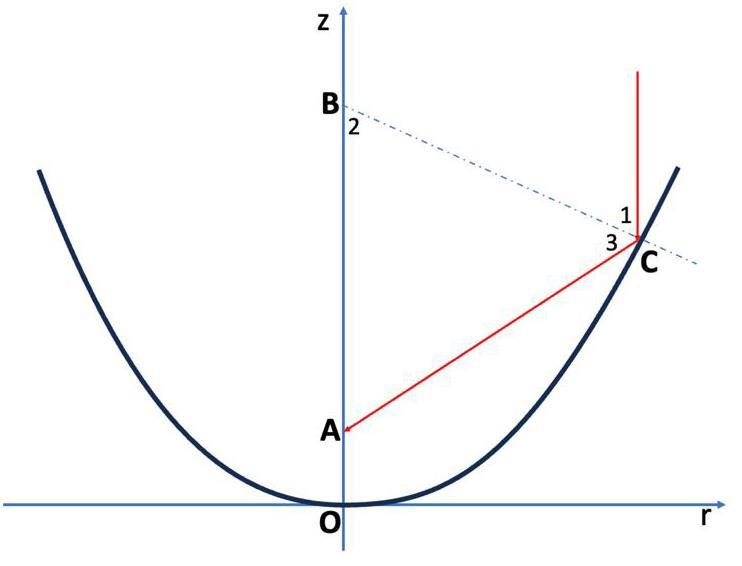

The proposed sOAP mirror, as shown in Fig. 1, satisfies the following equation in cylindrical coordinates

Without a loss of generality,

Focus Location

Rewriting Eq. 1 obtains the following:

The length AC is given by:

Focus Speed

The optical path difference is expressed as

Considering Eq. 8 and substituting Eq. 12 while retaining only the first-order terms of

According to Eq. 21, in both cases where

Beam Phase in the Focus Line

The relationship between the optical path difference

Inserting this into Eq. (20), the following is obtained:

Focus Length

As shown in Eq. 13, instead of focusing on a single point as in a normal OAP, the sOAP focuses on a line of length Lf:

Note that the requirement is

Coherent Compton Scattering

Consider a bunch of electrons with a spatial distribution

Thus, coherent Compton scattering can be achieved in two ways. The first option is to reduce the interaction area between electrons and photons, that is,

The second option involves using periodical ρe and/or

Therefore, coherent Compton scattering involves periodic electron and photon bunches, which are key to achieving high-intensity scattered radiation.

Different light sources use different strategies. For a wiggler, incoherent radiation arises as electrons pass through a magnetic structure, with an output light intensity scaling of [23]:

Coherent Compton scattering is an example of a quantum-coherence-enhanced phenomenon. As a special case of Compton scattering, coherent Compton scattering has been widely studied in various experimental and astrophysical contexts [24]. For example, astronomical observations are believed to be manifestations of coherent Compton scattering of light on well-structured charge layers surrounding celestial bodies [25, 26]. Coherent Compton scattering in van der Waals materials has also been observed experimentally [27]. Additionally, the Kapitsa–Dirac effect is often interpreted as a special case of coherent Compton scattering, in which electrons are scattered by periodical photons [28]. Coherent Compton scattering, involving low-energy electrons interacting with standing waves, has been experimentally observed [29]. Similar to other quantum coherence phenomena, coherent Compton scattering follows the characteristic scaling laws of

Coherent Compton Light Source with sOAP

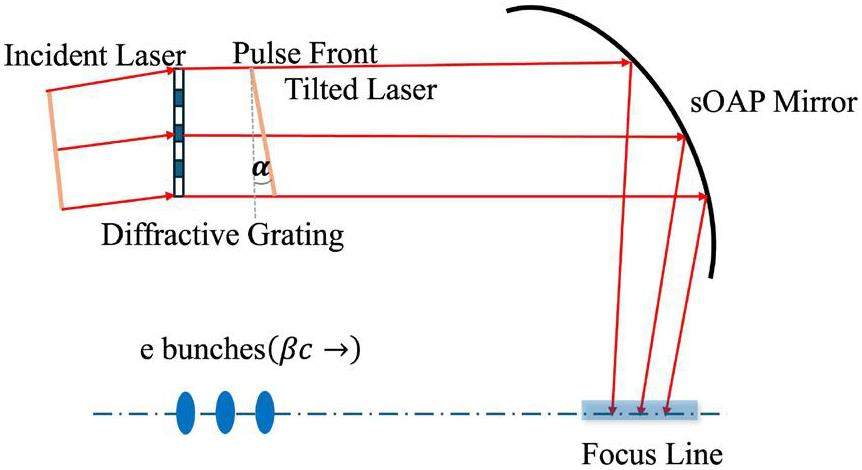

The proposed setup is shown in Fig. 3. An incident plane-wave laser pulse first passes through an optical diffractive grating element, where α represents the tilt angle between the pulse front and phase front. While the phase front remains perpendicular to the propagation direction [30-32], the laser arrival time is delayed proportionally to the radius of the parent stretched parabola, expressed as

Next, the front-tilted pulse is focused using the sOAP. Due to the time delay

Accordingly, the phase variations in Eq. 22 can be modified as follows:

To maintain coherent scattering, the electron bunch length must be significantly shorter than the incoming radiation wavelength, allowing all electrons to radiate in phase. Achieving this in the optical laser range is challenging, because typical electron pulses are larger than several millimeters. The concept of SSMB has been proposed to address this issue. However, owing to Coulomb expansion, it is difficult to achieve a small bunch that contains many electrons.

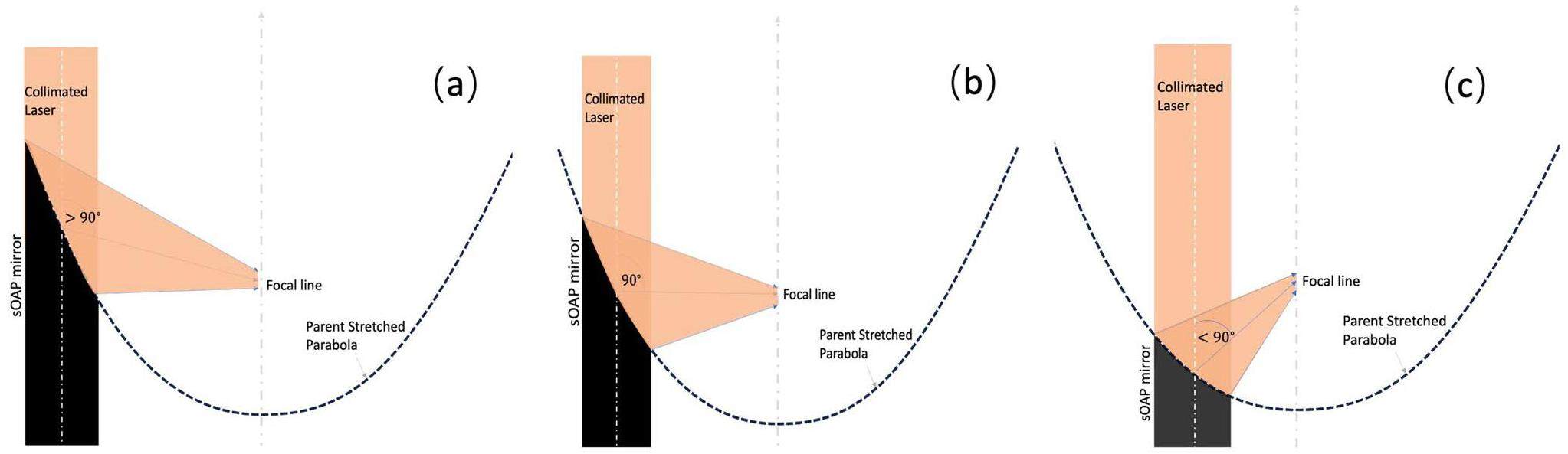

As shown in Refs. [21, 22], electron-beam scattering with a laser beam at a 90° angle always produces coherent radiation. This is because only a small slice of electrons interact with the photons at this interaction angle. Within this slice, all electrons interact coherently.

At a 90° angle, with a single focal point, the enhancement factor is [22],

At the 90° angle, where

| Electron bunches | |

|---|---|

| Number of electrons | |

| Electron energy | |

| Bunch length (LAB) | |

| Laser pulse (CO2) | |

| Wavelength | |

| Power/pulse length | W=2 J/3 ps |

| Repetition rate | f=1 kHz |

| sOAP | |

| Focus | f0=10cm |

| Deformation parameter | η=0.01 |

| Reflection angle range | 85°<θ<90θ |

| Tilt angle | α=10° |

| Scatted photons | |

| EUV energy | 92 eV, or 14 nm |

| Laser and beam spot size | 5μm |

| Central cone aperture | |

| Coherent enhancement factor | |

| Scattered photon number |

The coherence of the scattering is determined by the double form factor (Eq. 27), which is an integral highly dependent on the laser wavelength (

Summary

EUV lithography is critical for the semiconductor industry. However, the current tin-droplet-based light sources used in lithography face numerous limitations, highlighting the urgent need for next-generation technology.

In this study, the application of a sOAP was proposed to generate a coherent Compton light source. A flying focus train of photons can be created by combining a sOAP with a tilted pulse laser. When this highly periodic photon train, structured both temporally and spatially, interacts with highly periodic electron bunches, enhanced coherent EUV radiation can be generated. It is estimated that, by leveraging existing CO2 lasers in conjunction with a sOAP, it is possible to achieve a flux of 1016 photons per second at a wavelength of 14 nm. The proposed method, with its distinct advantages, holds significant promise as the foundation for next-generation EUV light sources.

Furthermore, the demand for high-quality light sources for modern fundamental scientific research and industrial applications is increasing rapidly. This includes the pursuit of extreme performance across multiple dimensions, such as a higher resolution (energy, spatial, and angular resolution), broader spectral range, and higher light intensity for applications in laser processing, optical communication, medical imaging, and fundamental research.

Taking advantage of the electrons coherently interacting with a moving photon focus spot, the coherent scattering from the sOAP setup is not limited to the EUV band. They can also be used to generate other wavelengths, including soft X-rays and X-rays, by increasing the electron energy or adjusting the laser wavelength. Furthermore, the proposed scheme is significantly more compact than devices such as FELs or synchrotron radiation facilities, potentially revolutionizing soft X-ray and X-ray applications in large-scale research infrastructures.

EUV lithography: state-of-the-art review

. J. Microelectron. Manuf. 2,High-NA EUV lithography: current status and outlook for the future

. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 61,Extreme ultraviolet lithography

. Nature Reviews Methods Primers 4, 84 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43586-024-00361-zThe development of laser-produced plasma EUV light source

. Chip 1,EUV-FEL light source for future lithography

, Paper Presented at the 14th International Particle Accelerator Conference (Venice, Italy, IPAC2023: THPM123, 2023)Experimental demonstration of the mechanism of steady-state microbunching

. Nature 590, 576-579 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03203-0Strip-line injection kicker for PAL-EUV booster synchrotron

. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 84, 189-197 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40042-023-00997-2High-power EUV free-electron laser for future lithography

. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 62,X-ray free-electron lasing in a flying-focus undulator

(2024). arXiv.2410.12975Flying focus and its application to plasma-based laser amplifiers

. Plasma Phys. Control. Fusion 61,Flying focus: Spatial and temporal control of intensity for laser-based applications

. Phys. Plasmas 26,Programmable-trajectory ultrafast flying focus pulses

. Optics Express 31, 31354-31368 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.499839Spatiotemporal control of laser intensity

. Nat. Photonics 12, 262-265 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-018-0121-8Spatiotemporal control of laser intensity through cross-phase modulation

. Optics Express 30, 9878-9891 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.451123Axiparabola: a long-focal-depth, high-resolution mirror for broadband high-intensity lasers

. Optics Letters 44, 3414-3417 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.44.003414Axiparabola: a new tool for high-intensity optics

. J. Opt. 24,Ultrabroadband flying-focus using an axiparabola-echelon pair

. Optics Express 32, 576-585 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.506112Use of spatiotemporal couplings and an axiparabola to control the velocity of peak intensity

. Optics Letters 49, 814-817 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.507713Coherent Compton x-ray sources

. Journal of X-Ray Science and Technology 4, 247-262 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-3996(05)80043-6Coherence in compton scattering at large angles1

. Laser and Particle Beams 15, 167-177 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0263034600010867Time resolved ultra small angle X ray scattering beamline (BL10U1) at SSRF

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 36 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01389-2The SLEGS beamline of SSRF

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 111 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01469-3Coherent inverse Compton scattering by bunches in fast radio bursts

. ApJ 925, 53 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ac3979Fast radio bursts as synchrotron maser emission from decelerating relativistic blast waves

. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 485, 4091-4106 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stz700Tunable free-electron X-ray radiation from van der waals materials

. Nat. Photonics 14, 686-692 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-020-0689-7Colloquium: Illuminating the Kapitza-Dirac effect with electron matter optics

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 79, 929-941 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.79.929Ultrafast Kapitza-Dirac effect

. Science 383, 1467-1470 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adn1555Breaking resolution limits in ultrafast electron diffraction and microscopy

. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 16105-16110 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0607451103Derivation of the pulse front tilt caused by angular dispersion

. Optical and Quantum Electronics 28, 1759-1763 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00698541High-gain Thompson-scattering X-ray free-electron laser by time-synchronic laterally tilted optical wave

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110,Yu-Gang Ma is the editor-in-chief for Nuclear Science and Techniques and was not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.