Introduction

Hydrostatic nuclear burning, which is the longest stage in a star’s life, is driven by a series of light-element fusion reactions. Among these, capture reactions are characterized by extremely small cross sections within the energy range of astrophysical interest (Gamow window), resulting in significant challenges for measurements [1, 2]. In addition, the cosmic-ray-induced background in ground laboratories further exacerbates these measurement challenges. Efforts to overcome these challenges have focused on enhancing beam intensity, increasing detection efficiency, and reducing background.

As the reaction yield scales with the beam intensity, increasing the beam intensity effectively improves the effect-to-background ratio in the measurements. Recently, mA-scale intensity proton beams have been achieved in several nuclear astrophysical facilities [3, 4], significantly enhancing the reaction yields but also posing challenges to the target stability [5, 6].

With a single high-purity germanium (HPGe) detector, the detection efficiency for γ rays in the MeV energy range emitted by capture reactions is low, usually on the order of a few percentages. The summing technique, which employs a scintillator detector array to achieve near 4π solid-angle coverage, significantly enhances the γ-ray detection efficiency [7, 8], advancing the measurement of capture reactions with low cross sections. Currently, several detector arrays are employed in nuclear astrophysical experiments, for instance, SuN [9] at the National Superconducting Cyclotron Laboratory (NSCL), HECTOR [10, 11] at the University of Notre Dame, the Compact Accelerator System for Performing Astrophysical Research (CASPAR), the BGO array [12] constructed in the Laboratory for Underground Nuclear Astrophysics (LUNA) at Laboratori Nazionali del Gran Sasso (LNGS), and the BGO array [13, 14] used in the Jinping Underground Nuclear Astrophysics experimental facility (JUNA) at China Jinping Underground Laboratory (CJPL).

Several methods can be used to reduce the background for γ-ray detection. Coincidence measurements such as γ–γ and charged particle–γ coincidences effectively reduce laboratory background [15-17], although they have specific limitations. For instance, the γ–γ coincidence method cannot be used to detect transitions in which a nucleus decays directly to its ground state by emitting only a single γ ray. In addition, the laboratory background can be significantly suppressed by compressing the beam into a short pulse [18]. The advantages of this method have been maximized in the study of laser-driven nuclear reactions with sub-nanosecond timescales [19, 20].

With the shielding provided by a kilometer-scale rock layer, underground laboratories can dramatically suppress the cosmic-ray-induced background, providing an ideal venue for nuclear astrophysical reaction studies. Currently, three underground nuclear astrophysics experimental facilities exist: LUNA [21] at INFN-LNGS, JUNA [22-24] at CJPL, and CASPAR [25] at SURF. Many experiments [11, 13, 26-33] focusing on the fusion reactions in hydrogen and helium burning have been performed in these underground facilities using the summing technique, providing a wealth of data for stellar evolution studies [34, 35].

Despite the significant advantages of underground experiments, many experiments [36-41] continue to be conducted in ground laboratories owing to the long measurement periods and limited beam times available in underground laboratories. Therefore, it is crucial to reduce the background of γ-ray detectors in ground laboratories. Recently, several studies have investigated the background of HPGe detectors using both active and passive shielding techniques [42-44]. Passive shielding effectively reduces the background from environmental radioactive nuclides, whereas active shielding significantly reduces the background induced by cosmic rays.

In this study, the second configuration of the Large-scale Modular BGO Detection Array (LAMBDA-II) was assembled specifically for nuclear astrophysics experiments. The laboratory background of LAMBDA-II was systematically measured under various shielding conditions. A significant reduction in the background, particularly within the energy ranges relevant to the capture reactions, was achieved using comprehensive shielding methods. Furthermore, the feasibility of using LAMBDA-II in conjunction with an mA-scale intensity beam to investigate capture reactions with low cross sections in ground laboratories was demonstrated by measuring the

LAMBDA-II design

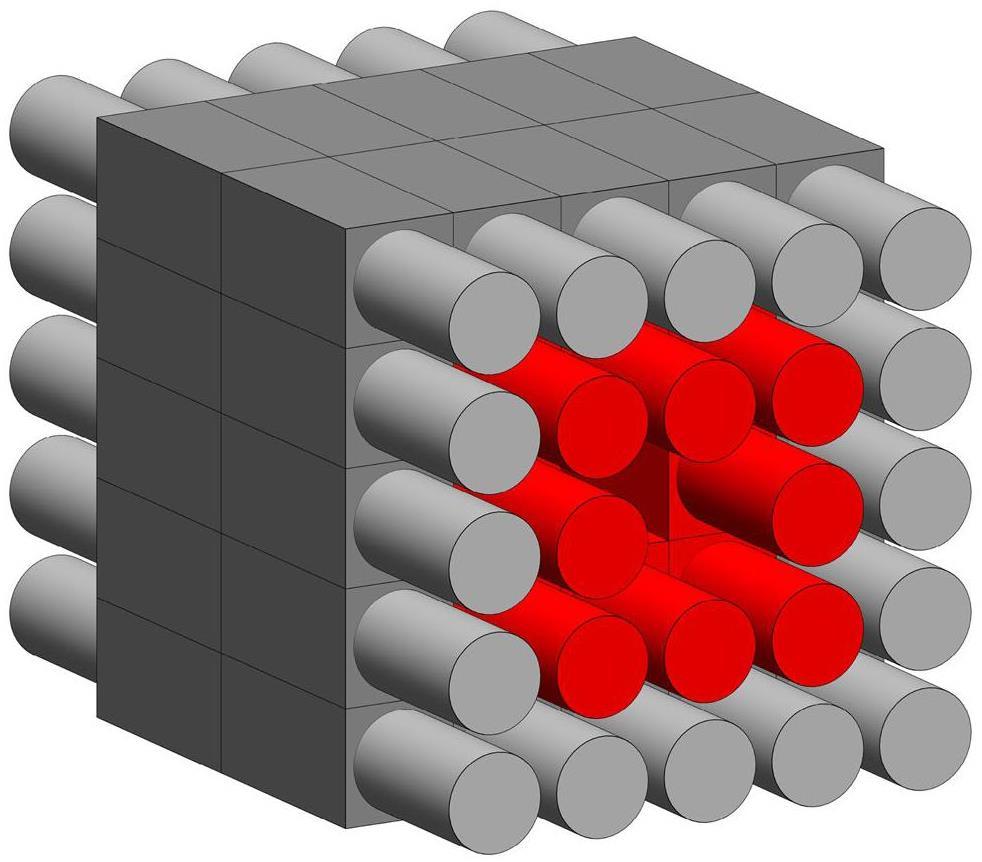

LAMBDA is a high-efficiency array primarily designed to measure the β-delayed γ decay of fission products [45]. It consists of 102 identical modules, each containing a 60 mm × 60 mm×120 mm bismuth germanate (BGO) crystal. Compared with other common scintillators, the BGO crystal, with an effective atomic number of 74.2 and a density of 7.13 g/cm3, exhibits a higher detection efficiency for γ-rays. The excellent consistency in the efficiency and energy resolution of the LAMBDA modules [45] makes them highly suitable for summing techniques.

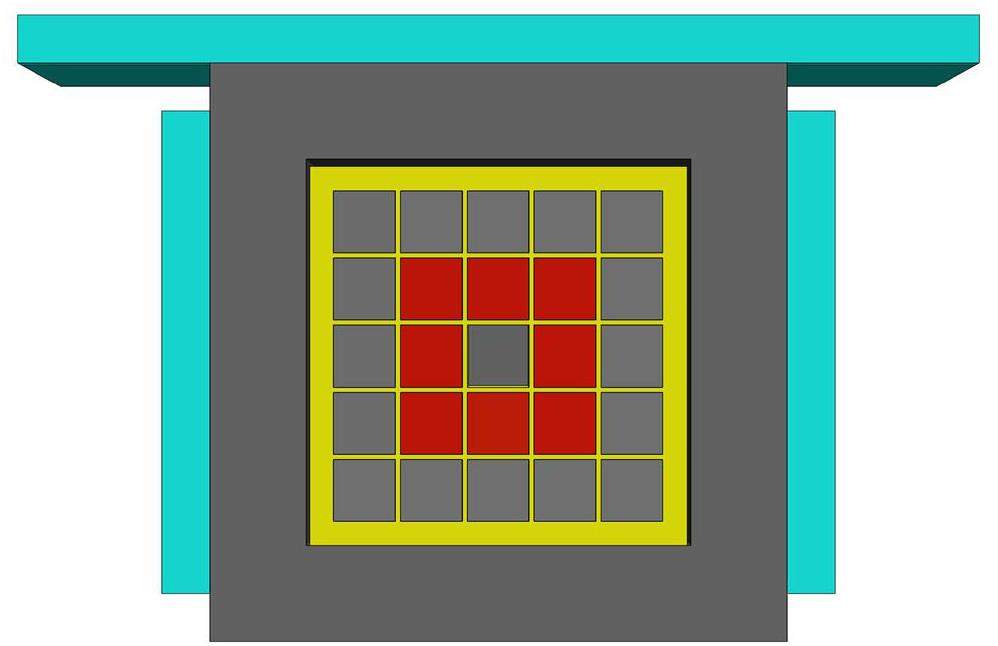

The rectangular design of the LAMBDA module allows flexible assembly into various configurations. To accommodate the nuclear astrophysical reaction measurements, 48 modules were configured in LAMBDA-II, as shown in Fig. 1. LAMBDA-II comprises two layers: an inner layer with 16 BGO modules (inner BGO modules) and an outer layer with 32 BGO modules (outer BGO modules). The center of LAMBDA-II features a 64 mm × 64 mm square hole for positioning the reaction target and vacuum pipe. LAMBDA-II operates in two modes based on the laboratory background levels. In underground laboratories with a minimal background, both the inner and outer BGO modules are used to construct the sum spectra, maximizing the γ-ray detection efficiency. Conversely, in ground laboratories with high background levels, the inner BGO modules function as primary detectors, whereas the outer BGO modules serve as anticoincidence detectors to generate veto signals for background reduction.

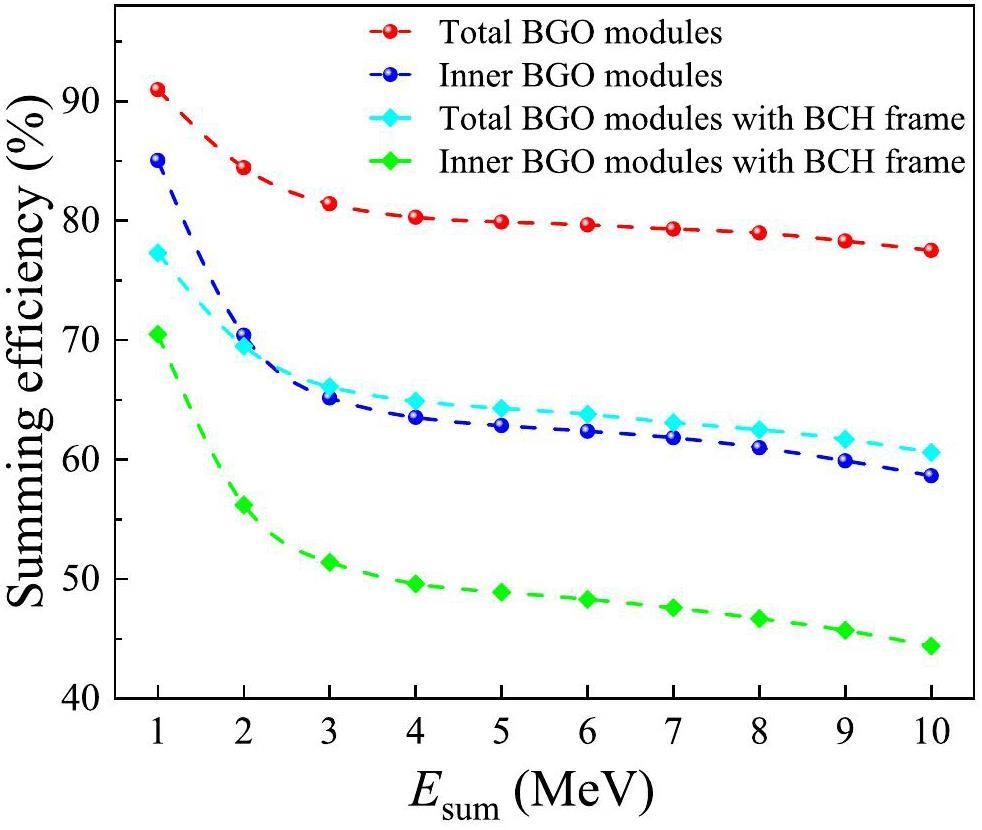

The average energy resolution of LAMBDA-II was measured as 10.0% using a 137Cs source. A simulation with GEANT4 [46] showed that the summing efficiencies of all BGO modules exceed 75% in the 1–10 MeV energy range when the source is positioned at the center of LAMBDA-II and the center hole remains empty. Compared to HECTOR and SuN, which are commonly used for measuring capture reactions in ground laboratories, the energy resolution of LAMBDA-II is slightly inferior, but its detection efficiency is higher. Taking advantage of these high efficiencies, the use of LAMBDA-II is expected to significantly enhance the precision of capture reaction measurements at the JUNA facility.

At typical γ-ray energies (6–20 MeV) relevant to capture reactions, the laboratory background mainly originates from secondary particles induced by cosmic rays, such as muons, pions, γ rays, electrons, protons, and neutrons [43]. Accordingly, a shielding system was designed for LAMBDA-II to reduce the laboratory background, as shown in Fig. 2. The LAMBDA-II modules were embedded within a grid frame made of 20% borated polyethylene (BCH), which effectively moderates and absorbs neutrons. The outer layer of the BCH frame is 2.5 cm thick, with internal partitions measuring 0.5 cm in thickness. Surrounding this frame, a 10 cm thick lead (Pb) layer provides 4π shielding to absorb γ-rays. Finally, 5 cm thick plastic scintillator detectors were positioned on the outermost layer, except at the bottom, to veto muon signals, as muons primarily originate from above the detector.

Background measurement and analysis

The background measurements of LAMBDA-II were conducted in a ground laboratory at Beijing Normal University (BNU). The signals were recorded using a data acquisition system based on Pixie-16 modules from XIA LLC [47], with a sampling frequency of 100 MHz and a resolution of 14 bits. Energy and timestamp data were recorded for both the BGO modules and plastic scintillator detectors. During the experimental data analysis, the γ-ray energy spectra of each BGO module were calibrated using the 1461 and 2614 keV peaks from 40K and 208Tl decays. After calibration, the summing spectrum (Esum) was obtained by summing the energies recorded by the inner BGO modules with a ±800 ns coincidence time window. Additionally, the sum of the energies recorded by the outer BGO modules was used as the BGO veto signal (VBGO), whereas the sum of the energies from the plastic scintillator detectors served as the plastic scintillator veto signal (Vplastic).

To investigate the effects of various shielding measures, the laboratory background of LAMBDA-II was measured under a series of incremental shielding conditions:

(1) Without any shielding.

(2) With 10 cm Pb shielding.

(3) With 10 cm Pb shielding and plastic scintillator detectors.

(4) With 10 cm Pb shielding and 25 cm BCH shielding.

(5) With 10 cm Pb shielding, plastic scintillator detectors, and 1 mm cadmium shielding.

(6) With a BCH frame, 10 cm Pb shielding, and plastic scintillator detectors.

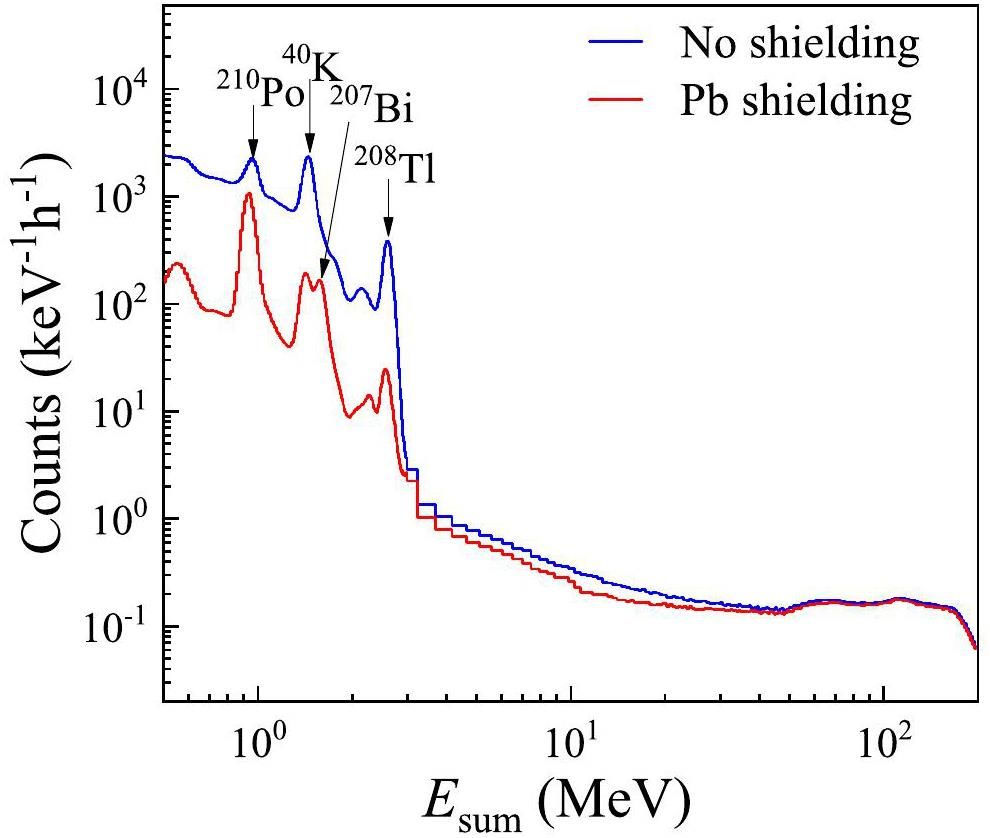

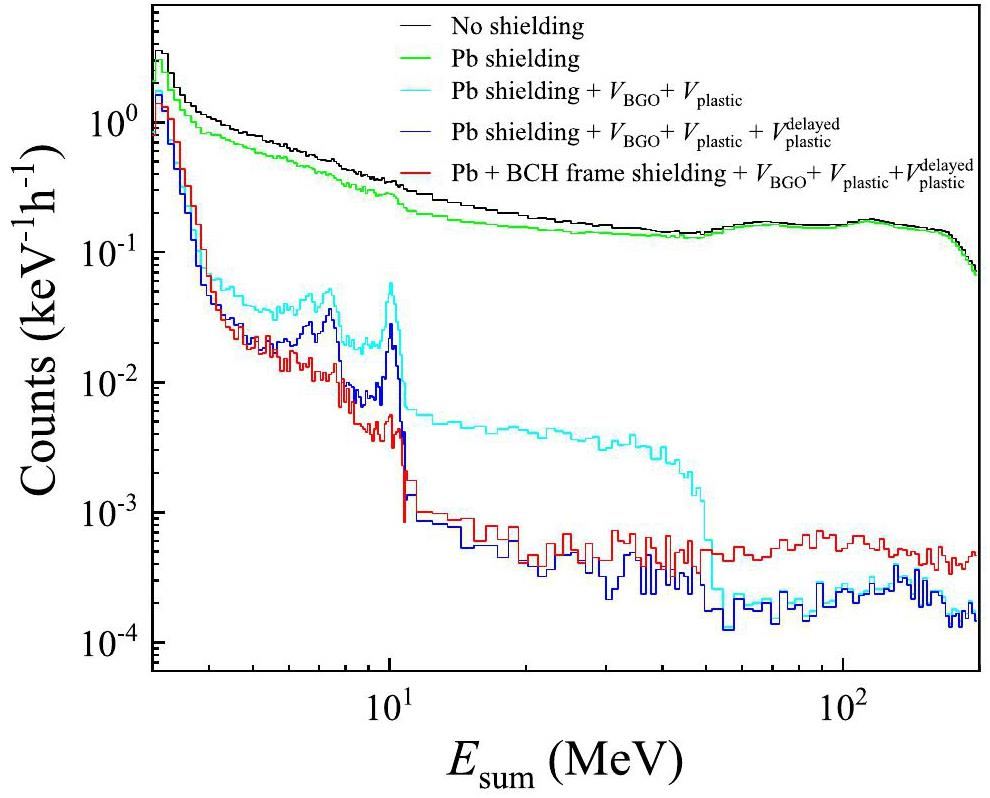

Figure 3 shows a comparison of the background measured without any shielding and with 10 cm Pb shielding. It is clear that the reduction in background varied significantly across the different energy regions. At energies below 3 MeV, the background is primarily produced by natural radioactivity. Above 3 MeV, the background is mainly caused by secondary particles induced by cosmic rays [43]. In the energy range 0.5 MeV < Esum < 3 MeV, the background was reduced by approximately one order of magnitude. This reduction is particularly evident from the representative 1461 and 2614 keV peaks from 40K and 208Tl decays, which were effectively absorbed by the 10 cm Pb layer. However, the intrinsic background, such as the 940 and 1633 keV peaks originating from the α particles emitted by 210Po decay and the 1063–570 keV cascade γ-rays from 207Bi decay, remained unaffected. For the energy range 3 MeV < Esum<50 MeV, only a minor reduction factor of approximately 0.5 was observed. The background in this energy range is believed to have a complex origin, primarily originating from various secondary particles induced by cosmic rays that are not effectively absorbed by the Pb layer. At energies above 50 MeV, no significant reduction in the background energy was observed, indicating that the main contributors were high-energy muons, which could easily pass through the Pb layer.

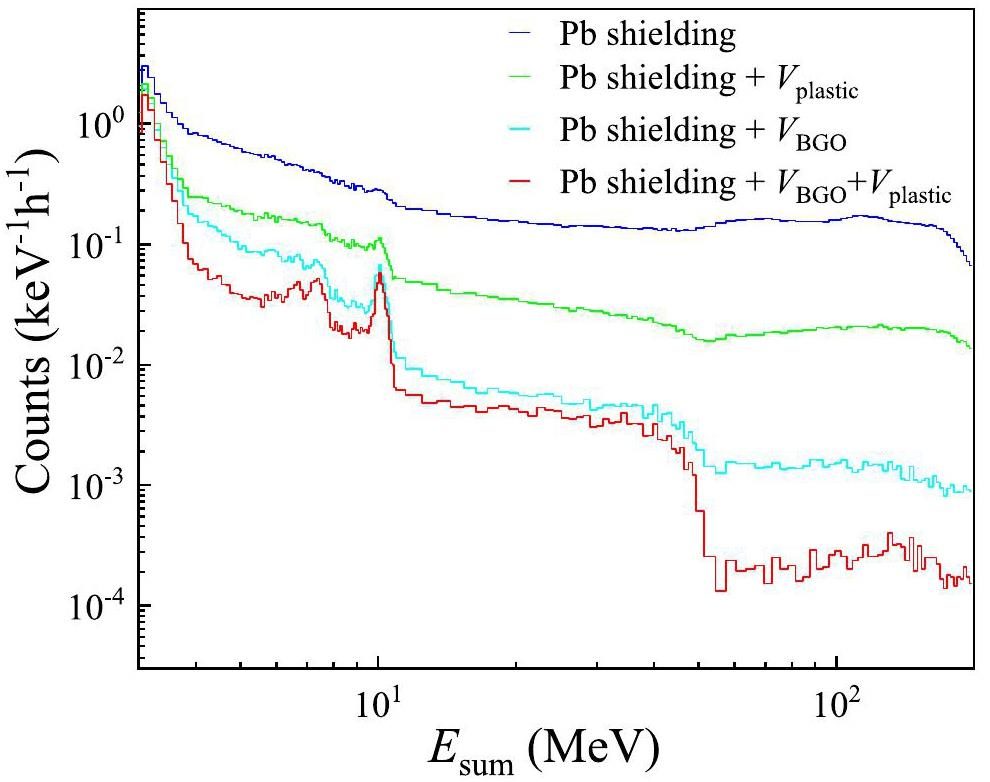

To further suppress the cosmic-ray-induced background, which cannot be effectively reduced by Pb shielding alone, an anti-coincidence technique was adopted by introducing plastic scintillator detectors. In addition, the outer BGO modules of LAMBDA-II were employed as veto detectors. An anti-coincidence time window of ±800 ns was applied. Based on the 10 cm Pb shielding, Fig. 4 compares the background obtained without any veto, with VBGO, with Vplastic, and with VBGO+Vplastic. It is evident that anticoincidence significantly reduces the background across the full energy region, with more pronounced effects at higher Esum energies. In addition, VBGO provides stronger suppression of the background than Vplastic, indicating that the outer BGO modules have a higher detection efficiency for cosmic-ray-induced particles. However, the outer BGO modules did not cover the inner BGO modules along the axial direction, limiting their ability to veto cosmic-ray-induced particles entering at low horizontal angles. Therefore, the background was further reduced when both VBGO and Vplastic were combined in an anti-coincidence manner, as shown in Fig. 4.

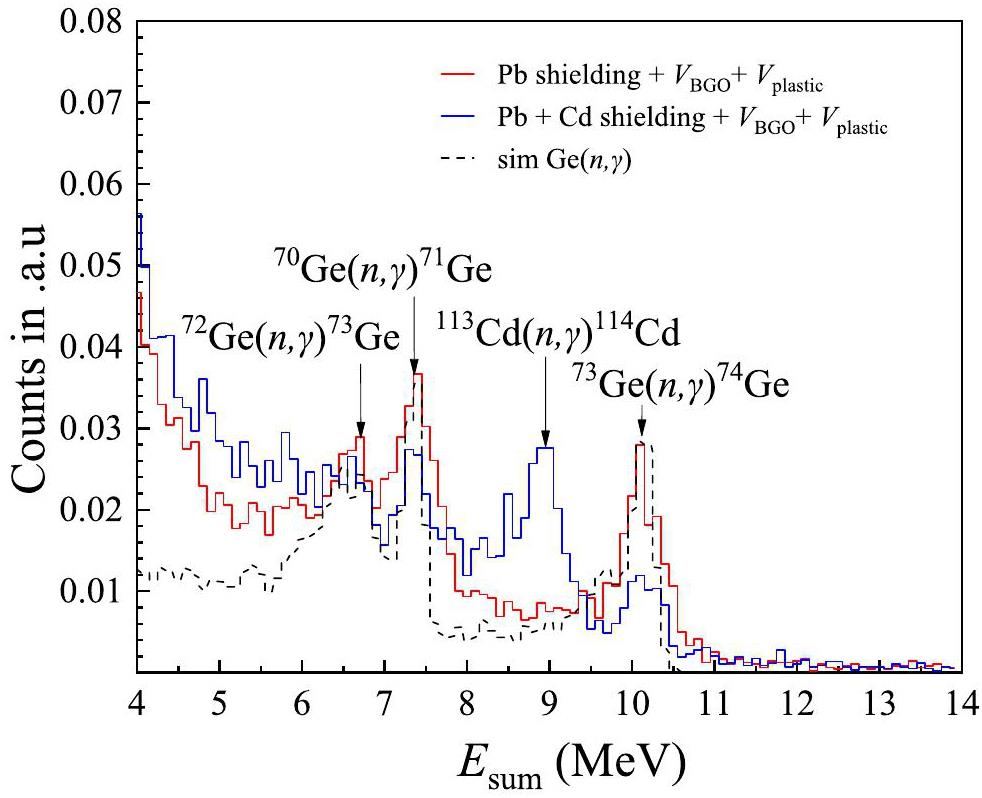

The reduction in background after anti-coincidence varied across different energy ranges. In the 50–200 MeV energy range, the background was reduced by a factor of approximately 500, indicating that the contribution from muons was dramatically suppressed. In the 6–50 MeV energy range, a lower reduction factor of approximately 25 was observed, suggesting that part of the background could not be effectively removed using the anti-coincidence method. Notably, three characteristic peaks at approximately 6.8, 7.4, and 10.2 MeV were observed. These peaks are supposed to be caused by the thermal neutron capture on germanium (Ge) isotopes, as the peak energies correspond to the Q-values of the

To confirm that the characteristic γ-ray peaks originated from neutron capture reactions on the Ge isotopes, LAMBDA-II was wrapped in a 1 mm thick Cd layer with additional 1 mm thick Cd pieces inserted into the gaps between the BGO modules. As shown in Fig. 5, the γ-ray peaks attributed to neutron capture on the Ge isotopes were significantly reduced by adding the Cd material, whereas a new characteristic γ-ray peak appeared at approximately 9.0 MeV. The energy of this new peak was consistent with the Q value of the

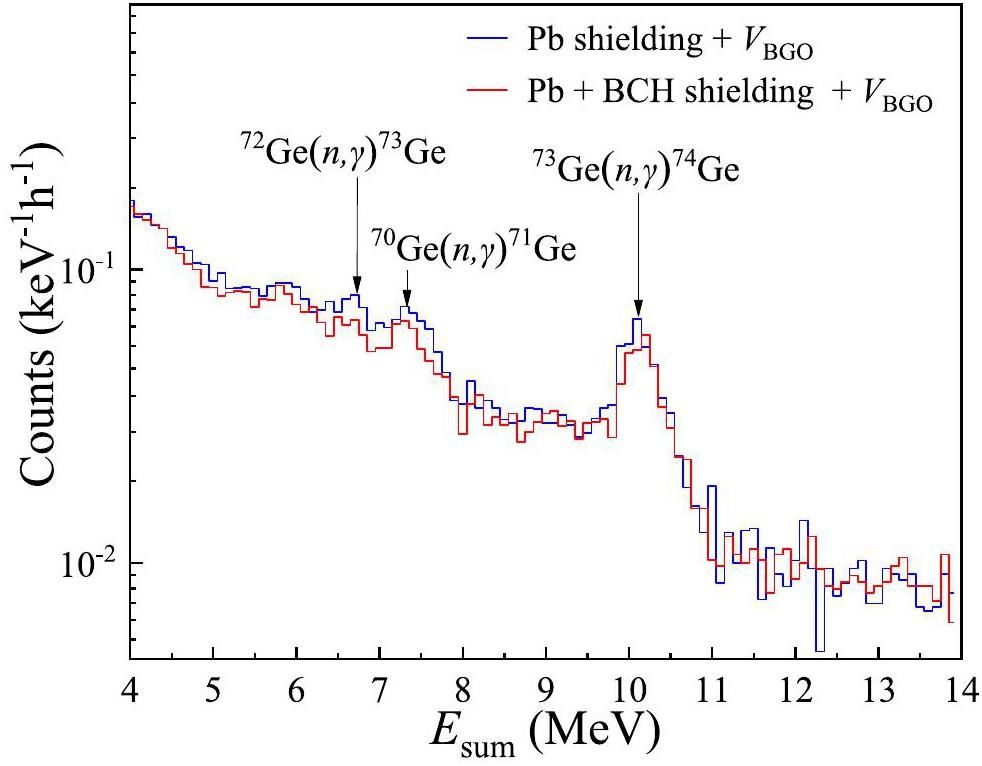

To explore the origin of the thermal neutrons captured by the Ge isotopes, an additional 25 cm thick 20% BCH layer was externally added and placed on all six sides of the Pb shielding. As the size of the BCH blocks was not sufficient to fully cover the plastic scintillator detectors, they were removed during this measurement. A previous study showed that a 22.4 cm thick 5% BCH layer can absorb approximately 98% of the neutrons emitted by Am-Be and 252Cf sources [48]. Therefore, if neutrons come from outside the Pb layer, they would be predominantly absorbed by the BCH layer, resulting in the disappearance of the three characteristic peaks associated with thermal neutron capture. However, as shown in Fig. 6, these peaks were only partially suppressed after the addition of BCH shielding. This observation indicates that a fraction of the neutrons did not originate from the external environment, but were produced within materials located inside the BCH shielding, including the Pb layer and LAMBDA-II itself.

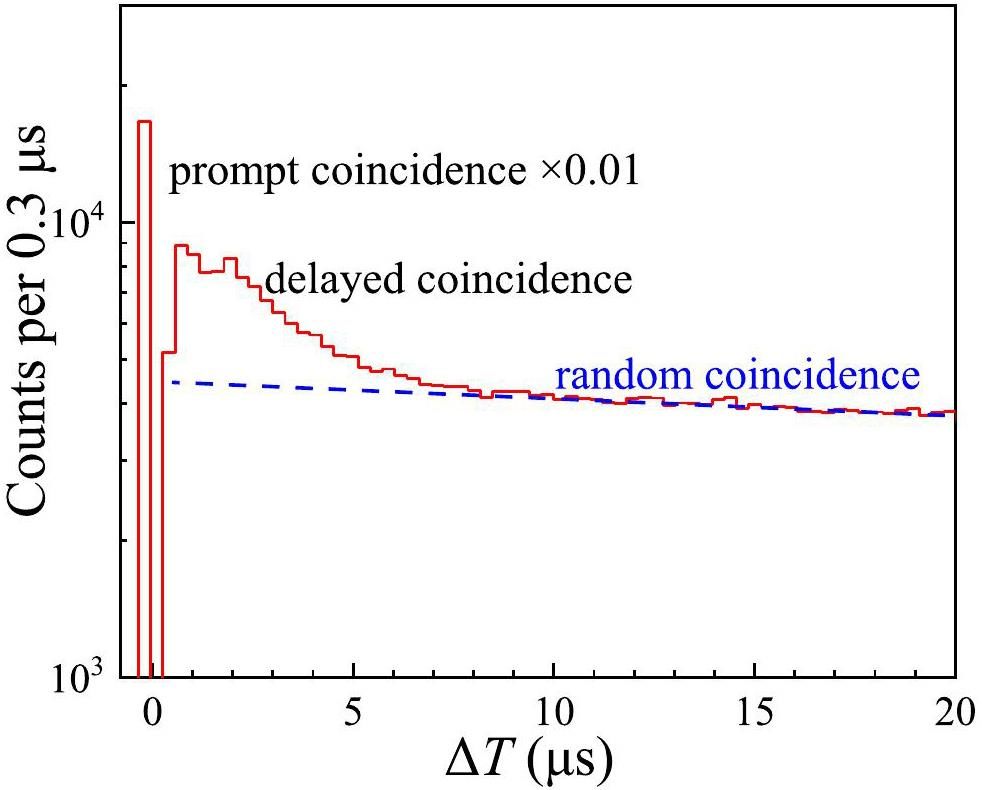

Neutron emission within the Pb shielding and BGO crystals can arise either from intrinsic radioactivity or from interactions induced by external radiation. The former can be excluded because no significant neutron capture peaks were observed in the background when measured for the BGO detector with Pb shielding in an underground laboratory [49]. For the latter, secondary cosmic rays, such as muons, can produce neutrons when interacting with Pb and BGO materials [50]. These high-energy radiations can easily penetrate the BCH shielding. If neutron capture reactions are prompt, they should be effectively vetoed by using plastic scintillator detectors. However, as shown in Fig. 4, the reduction in the neutron capture peaks in the background when VBGO was applied remained minimal. This suggests that neutron capture reactions occur as delayed events relative to the precursor particles and therefore cannot be completely excluded by the ±800 ns anti-coincidence time window.

To validate this hypothesis, a microsecond-scale correlation analysis between the signals from the inner BGO modules and the preceding adjacent signals from the plastic scintillator detectors was performed on the measured data, as shown in Fig. 4. The observed time difference (ΔT) spectra are shown in Fig. 7, which reveal three distinct time distribution structures. The front-most peak, scaled down by a factor of 0.01 for better visualization, corresponds to prompt coincidences. Events with

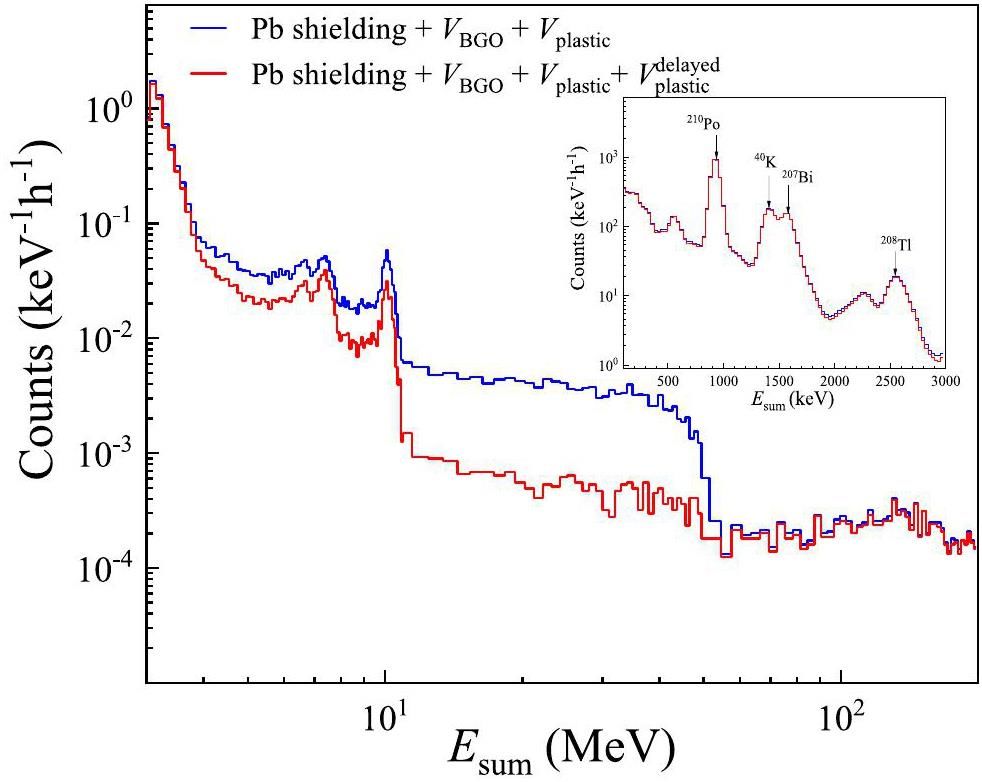

To further suppress the background produced by the delayed events, an additional delayed veto signal (

While further reducing the background,

As shown in Fig. 8, the background level in the 6–11 MeV range, which is of particular importance for capture reaction measurements, remained significantly higher than that above 11 MeV, even after applying the delayed veto. This persistent background is attributed to two factors: (1) the absence of a 25 cm thick BCH shielding outside the Pb shielding, as its dimensions are inadequate to fully cover the plastic scintillator detectors, and (2) the limitation of the width of the delayed veto time window owing to its impact on the dead time of nuclear reaction measurements. Therefore, a practical solution is required to effectively absorb neutrons and reduce the background caused by neutron capture reactions.

Adding a Cd layer can effectively absorb thermal neutrons but introduces a new γ peak at 9.0 MeV, as shown in Fig. 5. BCH is a good alternative to Cd because the 10B(n, αγ)7Li reaction produces only a 478 keV γ-ray, which has no impact on the capture reaction measurements. A grid frame composed of BCH was constructed, and the LAMBDA-II modules were embedded within it, as shown in Fig. 2. As presented in Fig. 9, the γ-ray peaks caused by neutron capture on Ge isotopes were significantly suppressed by the BCH frame, leading to a substantially lower background in the 6–11 MeV range. However, a slight increase in the background was observed in other energy regions. This increase was attributed to the larger gaps introduced between the BGO modules by the BCH frame, which reduced the veto efficiency of the outer BGO modules. In addition, the use of the BCH frame decreased the summing efficiency of LAMBDA-II, as shown in Fig. 10.

Figure 9 also compares the background obtained under different shielding measures implemented in this work, as well as that without shielding. For the 6–20 MeV energy range, the background was significantly reduced by the combined use of passive and active shielding measures. The Pb shielding mainly absorbed the γ-rays from the laboratory environment. VBGO+Vplastic effectively suppressed the prompt signals caused by the secondary cosmic rays interacting with the inner BGO modules.

The specific background levels under various shielding conditions are summarized in Table 1. The optimized background levels in the 6–11 MeV and 11–20 MeV energy ranges are 8.1×10-3 keV-1h-1 and 1.0×10-3 keV-1h-1, respectively. These background levels were approximately two orders of magnitude higher than those observed for BGO detector arrays in underground laboratories [13, 51].

| Shielding conditions | 6-11 MeV | 11-20 MeV |

|---|---|---|

| No shielding | 4.4×10-1 | 2.4×10-1 |

| Pb shielding | 3.4×10-1 | 1.8×10-1 |

| Pb shielding + VBGO+Vplastic | 3.0×10-2 | 4.8×10-3 |

| Pb shielding+ VBGO+Vplastic + |

1.7×10-2 | 8.2×10-4 |

| Pb + BCH frame shielding + VBGO+Vplastic + |

8.1×10-3 | 1.0×10-3 |

The detection efficiency of LAMBDA-II decreased with the addition of the BCH frame. This is partly due to the increased distance between the BGO modules and partly because the BCH frame absorbs some of the gamma-ray energy. Figure 10 presents a comparison of the detection efficiency of LAMBDA-II with and without the BCH frame based on Geant4 simulations. To reduce the background, the detection efficiency of LAMBDA-II used in the ground laboratory (green line in Fig. 10) is approximately 30% lower than that used in an underground laboratory (red line in Fig. 10). This decrease in detection efficiency would hinder the capture reaction measurements.

In-beam commissioning of LAMBDA-II in a ground laboratory

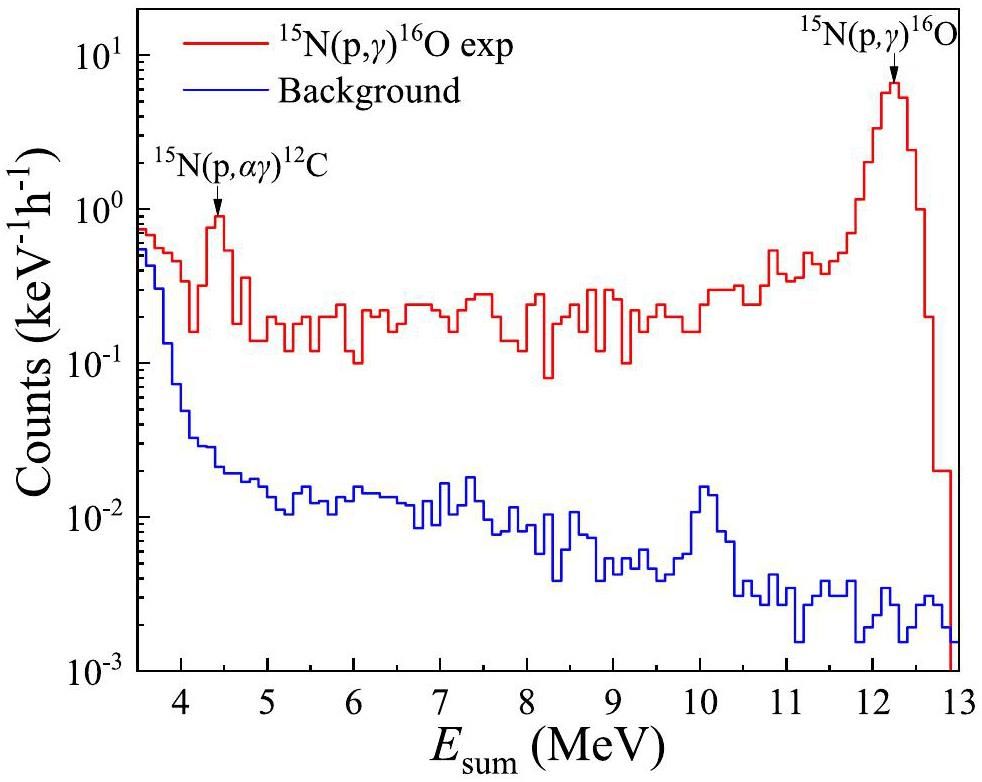

To evaluate the ability of LAMBDA-II to measure astrophysical capture reactions in ground laboratories, in-beam commissioning was performed by measuring the γ-rays emitted from the

In this experiment, LAMBDA-II and its shielding system were installed at the 350 kV accelerator located at the Institute of Nuclear Energy Safety Technology (INEST) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences [4]. The proton beam was collimated and directed onto a Ti15N target positioned at the center of LAMBDA-II. The typical beam current applied to the target was approximately 2 mA. Fig. 11 shows the Esum spectrum obtained at Ep=125 keV, where the sum peak at approximately 12.2 MeV caused by the

Under the sum peak of the

Summary

In this study, LAMBDA-II was developed to measure the capture reactions of astrophysical interest. Its two-layer structure makes it suitable for experiments conducted in both underground and ground laboratories. The high detection efficiency of LAMBDA-II is expected to significantly enhance the precision of future experiments conducted at the JUNA facility. The origin of the background of LAMBDA-II in the ground laboratories was systematically investigated through measurements under a series of incremental shielding conditions. By combining Pb and BCH frame shielding, vetoes from the plastic scintillator detectors and outer BGO modules, and delayed vetoes, the background was significantly reduced to 8.1×10-3 keV-1h-1 and 1.0×10-3 keV-1h-1 in the 6–11 and 11–20 MeV ranges, respectively. The capability of LAMBDA-II to measure astrophysical capture reactions in ground laboratories was demonstrated by measuring

Design of an intense ion source and LEBT for Jinping Underground Nuclear Astrophysics experiments

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 830, 214-218 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2016.05.099A new platform for nuclear astrophysics studies on Hefei Facility

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. B 1054,Strong and durable fluorine-implanted targets developed for deep underground nuclear astrophysical experiments

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. B 496, 9-15(2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2021.03.017Development of irradiation-resistant enriched 12C targets for astrophysical 12C(α,γ)16O reaction measurements

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. B 512, 49-53(2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2021.11.020Cross section measurements of the 89Y(p,γ)90Zr reaction at energies relevant to p-process nucleosynthesis

. Phys. Rev. C 70,Cross-section measurements of capture reactions relevant to the p process using a 4πγ-summing method

. Phys. Rev. C 76,SuN: Summing NaI(Tl) gamma-ray detector for capture reaction measurements

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 703, 16-21(2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2012.11.045High Efficiency Total Absorption Spectrometer HECTOR for capture reaction measurements

. Eur. Phys. A 55, 77(2019). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2019-12748-8Measurement of Low-Energy Resonance Strengths in the 18O(α,γ)22Ne Reaction

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128,A new setup for the underground study of capture reactions

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 489, 160-169(2002). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(02)00577-6First result from the Jinping Underground Nuclear Astrophysics experiment JUNA: precise measurement of the 92 keV 25Mg(p,γ)26Al resonance

. Sci. Bull. 67, 125-132(2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scib.2021.10.018Response functions of a 4π summing gamma detector in β-Oslo method

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 68(2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01058-2Determination of 141Pr(α, n)144Pm cross sections at energies of relevance for the astrophysical p process using the γγcoincidence method

. Phys. Rev. C 84,Measurements of fusion cross-sections in 12C+12C at low beam energies using a particle-γ coincidence technique

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 682, 12-15(2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2012.03.051γ-Particle coincidence technique for the study of nuclear reactions

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 749, 19-26(2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2014.02.014An independent measurement of the 12C(α, γ)16O cross section with the Karlsruhe 4π BaF2 detector

. Nucl. Phys. A 758, 415-418 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2005.05.0762H(p,γ)3He cross section measurement using high-energy-density plasmas

. Phys. Rev. C 101,First measurement of the 7Li(D, n) astrophysical S-factor in laser-induced full plasma

. Phys. Lett. B 843,LUNA: a laboratory for underground nuclear astrophysics

. Rep. Prog. Phys. 72,Progress of Jinping Underground laboratory for Nuclear Astrophysics (JUNA)

. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 59,Underground laboratory JUNA shedding light on stellar nucleosynthesis

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 42(2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01196-1Recent progress in nuclear astrophysics research and its astrophysical implications at the China Institute of Atomic Energy

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 217(2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01590-3Underground nuclear astrophysics studies with CASPAR

. EPJ Web Conf. 109, 09002(2016). https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/201610909002Direct Measurement of the Astrophysical 19F(p,αγ)16O Reaction in the Deepest Operational Underground Laboratory

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127,Measurement of 19F(p, γ)20 Ne reaction suggests CNO breakout in first stars

. Nature 610, 656-660(2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05230-xUnderground Measurements of Nuclear Reaction Cross-Sections Relevant to AGB Stars

. Universe 8, 4(2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/universe8010004Measurement of the 18O(α,γ)22Ne Reaction Rate at JUNA and Its Impact on Probing the Origin of SiC Grains

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130,Updated reaction rate of 25Mg(p,γ)26Al and its astrophysical implication

. Phys. Rev. C 107,First Direct Measurement of the 64.5 keV Resonance Strength in the 17O(p,γ)18F Reaction

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 133,Examining the fluorine overabundance problem by conducting Jinping deep underground experiment

. Nucl. Tech. 46,Direct measurement of the break-out 19F(p, γ)20Ne reaction in the China Jinping underground laboratory (CJPL)

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 143(2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01531-0Exploring stars in underground laboratories: challenges and solutions

. Annu. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 72, 177-204(2022). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nucl-110221-103625Solar fusion III: New data and theory for hydrogen-burning stars

(2024), arXiv:2405.06470351 [astroph.SR]. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2405.06470Direct Measurement fo the 14N(p,γ)15O S Factor

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94,Investigation of the 14N(p,γ)15O reaction and its impact on the CNO cycle

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Absolute cross section of the 12C(p,γ)13N reaction

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Nuclear astrophysics research based on HI-13 tandem accelerator

. Nucl. Tech. 46,Measurements of 27Al(γ, n) reaction using quasi-monoenergetic γ beams from 13.2 to 21.7 MeV at SLEGS

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 36, 66(2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-025-01662-yNovel thick-target inverse kinematics method for the astrophysical 12C+12C fusion reaction

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 208(2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01573-4Monte Carlo simulation of the muon-induced background of an anti-Compton gamma-ray spectrometer placed in a surface and underground laboratory

. Radioact. Environ. 8, 529-537(2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/S1569-4860(05)08042-3Cosmic-ray-induced background intercomparison with actively shielded HPGe detectors at underground locations

. Eur. Phys. J. A, 51, 33(2015). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2015-15033-0Background in γ-ray detectors and carbon beam tests in the Felsenkeller shallow-underground accelerator laboratory

. Eur. Phys. J. A, 55, 10(2019). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2019-12865-4The large-scale modular BGO detection array (LAMBDA) design and test

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 207(2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01574-3Geant4—a simulation toolkit

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 506, 250(2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(03)01368-8Experimental study and analysis of 5% boron-containing polyethylene shielded fast neutrons

. Chin. J. Radiol. Health 22, 396(2013). https://doi.org/10.13491/j.cnki.issn.1004-714x.2013.04.001Measurement of γ detector backgrounds in the energy range of 3-8 MeV at Jinping underground laboratory for nuclear astrophysics

. Sci. China-Phys. Mech. Astron. 60,Measurement of muon-induced neutron yield at the China Jinping Underground Laboratory

. Chin. Phys. C 46,Advances in radiative capture studies at LUNA with a segmented BGO detector

. J. Phys. G 50,Proton capture by 15N

. Nucl. Phys. 15, 289-315 (1960). https://doi.org/10.1016/0029-5582(60)90308-4Proton capture by 15N at stellar energies

. Nucl. Phys. A 235, 450-459(1974). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(74)90205-XDirect measurement of the 15N(p,γ)16O total cross section at novae energies

. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 36,Constraining the S factor of 15N(p,γ)16O at astrophysical energies

. Phys. Rev. C 82,Revision of the 15N(p,γ)16O reaction rate and oxygen abundance in H-burning zones

. Astron. Astrophys. 533,NACRE II: an update of the NACRE compilation of charged-particle-induced thermonuclear reaction rates for nuclei with mass number A<16

. Nucl. Phys. A 918, 61-169(2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2013.09.007The authors declare that they have no competing interests.