| Specifications Table | |

|---|---|

| Subject | Nuclear physics |

| Specific subject area | Experimental data |

| Data format | Raw/Analyzed |

| Type of data | Tables and Figures |

| Data acquisition | Measurements using a flat-efficiency detector (FED) array |

| Parameters for data collection | Photoneutron cross-section data |

| Description of data collection | Data were collected by saving list-mode detector array during acquisitions. |

| Data collection | Data were collected from 2020 using the SLEGS gamma beam and FED array. |

| Data source location | Institution: Shanghai Advanced Research Institute, CAS |

| Country: China | |

| Data accessibility | Repository name: Science Data Bank |

| Data identification number: https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.19543 | |

| https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.19552 | |

| https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.19582 | |

| Related research article | Z.R. Hao, Nuclear Techniques (In Chinese), 43, 9(2020). doi:10.11889/j.0253-3219.2020.hjs.43.110501. |

| Z.R. Hao, et al., NIMA:1013 (2021) 165638. doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2021.165638 | |

| H.H. Xu, et al., NIMA1033, 166742 (2022). doi:10.1016/j.nima.2022.166742. | |

| H.W. Wang, et al., Nucl. Sci. Tech., 33, 87 (2022). doi:10.1007/s41365-022-01076-0. | |

| Z.R. Hao, et al., Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35(3), 65 (2024) doi: 10.1007/s41365-024-01425-1. | |

| Z.R. Hao, NIMA1068, 169748 (2024). doi:10.1016/j.nima.2024.169748. | |

| Z.R. Hao, et al., NIMA1013, 165638 (2021). doi:10.1016/j.nima.2021.165638. | |

| L.X. Liu, et al., Nucl. Sci. Tech., 35, 111(2024). doi:10.1007/s41365-024-01469-3 | |

| L.X. Liu, et al., NIMA1063, 169314 (2024). doi:10.1016/j.nima.2024.169314. | |

| Z.C. Li et al., NIMB559(2025) 165595, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2024.1655 | |

| Z.R. Hao, et al., Science Bulletin (Accepted). | |

Introduction

Photonuclear reaction data play a pivotal role across numerous fields, serving as a cornerstone for advancing nuclear science and enabling diverse practical applications. These include nuclear analysis, detection and diagnosis, gamma activation analysis, nuclear safeguard and verification technologies, nuclear waste transmutation, absorbed dose calculations for human radiotherapy, and medical isotope production [1, 2]. For instance, the accurate measurement of photonuclear data is essential for ensuring the safety, efficiency, and reliability of nuclear reactors—a critical component of China’s sustainable development strategy. Within reactors, high-energy gamma rays can induce photonuclear reactions with structural materials, generating significant quantities of photoneutrons. These photoneutrons can perturb neutron equilibrium and migration dynamics. Consequently, precise photonuclear data are indispensable for both reactor operation and critical safety assessments.

However, acquiring precise photonuclear data poses significant challenges. Currently, most available photonuclear data are obtained from experimental gamma sources, such as bremsstrahlung or in-flight positron annihilation [3] (e.g., Saclay and LLNL Laboratories), or from theoretical databases, including TENDL [4], ENDF [5], JENDL [6], and CENDL [7]. A key limitation is that accelerator-based gamma sources typically produce quasi-monochromatic gamma rays rather than truly monochromatic ones. Consequently, monochromatic cross sections must be derived from quasi-monochromatic cross-section measurements. Unfortunately, the unfolding algorithms employed for this extraction do not yield unique solutions, resulting in significant discrepancies among global datasets. In China, the lack of such gamma sources has hindered the acquisition of independent experimental data related to photonuclear reaction cross-sections, constraining the evaluation and practical application of these data.

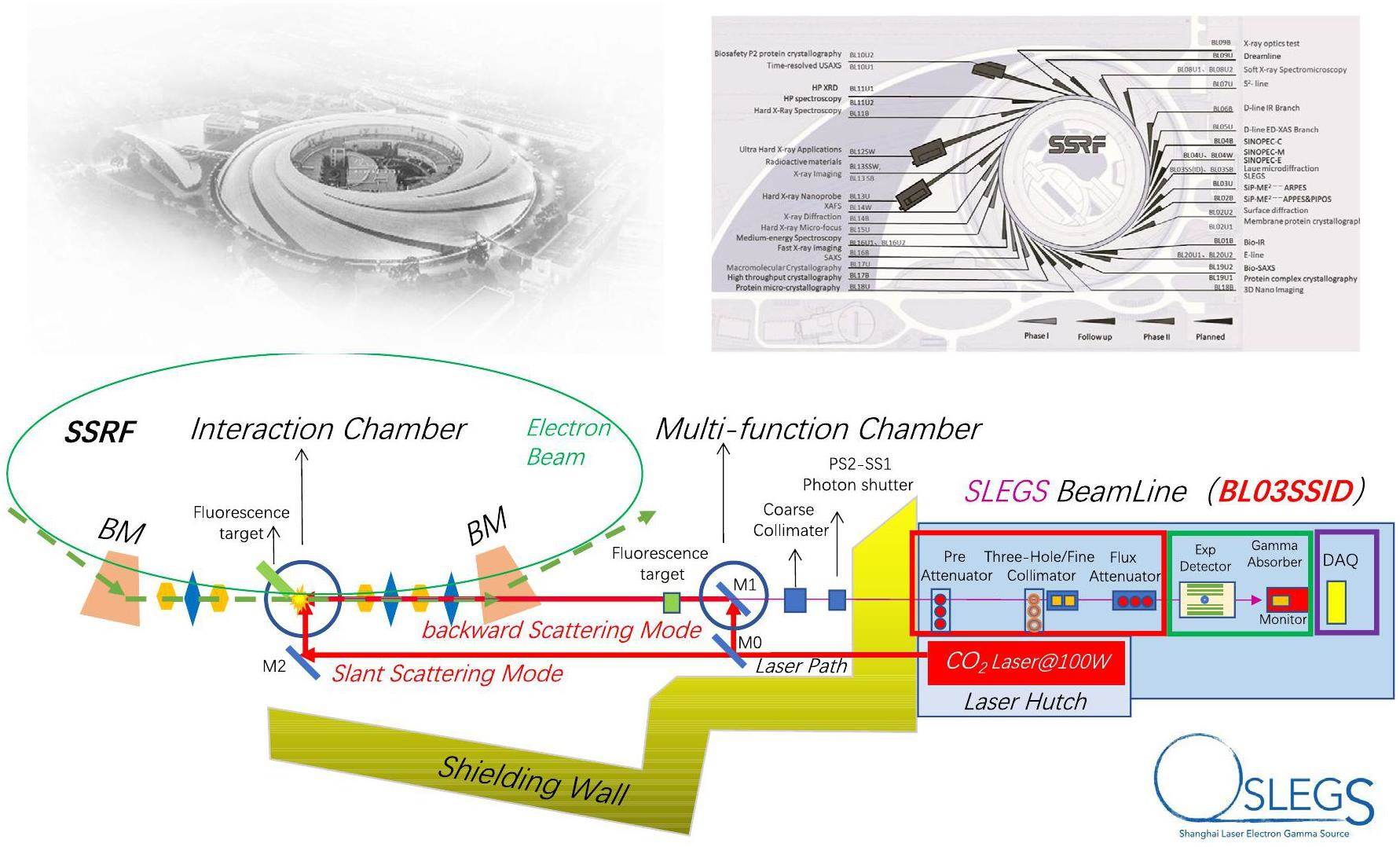

The Shanghai Laser Electron Gamma Source (SLEGS) [8-11], a facility based on laser Compton scattering (LCS), serves as a novel γ-ray source delivering mega-electronvolt-range γ-ray beams for research in photonuclear science and technology [12, 13]. It is one of the 16 beamlines at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF Phase II) [14]. Figure 1 presents a schematic of the SLEGS beamline. The SLEGS (https://CSTR.cn/31124.02.SSRF.BL03SSID) γ-ray is generated through the interaction between the electron beam from SSRF (https://CSTR.cn/31124.02.SSRF) storage ring and the photons from a continuous wave (CW) COHERENT DIAMOND Cx-10 (10.64 μm) CO2 laser [15] in the SLEGS laser hutch. This laser offers a power range of 0.1–137 W, a frequency range of 1–100 kHz, and adjustable pulse widths from 1 to 1000 μs.

The SLEGS produces quasi-monochromatic, energy-tunable γ-ray beams within the 0.66–21.7 MeV range by adjusting the interaction angle between the laser and electron beams. The corresponding inverse Compton scattering maximum energy ranges from 0.66 to 21.1 MeV for angles between 20 and 160, reaching 21.7 MeV at 180. The system achieves a photon flux of 2.1×104–1.2×107 photons/s, with an energy spread of 5%–15% depending on the collimator aperture. The tunable energy output of the SLEGS enables its coordinated operation with other beamlines.

The interaction angle can be adjusted in approximately 10 min, considerably minimizing beam operation time. The generated γ-rays are collimated using a Φ 1–30 mm coarse collimator (C); Φ 1–30 mm fine collimator (F); and three-hole collimator (T) with apertures of 1, 2, and 3 mm. The construction of the SLEGS was completed in December 2021, and the facility has been open to users since January 2023.

Experimental Design and Data Generation

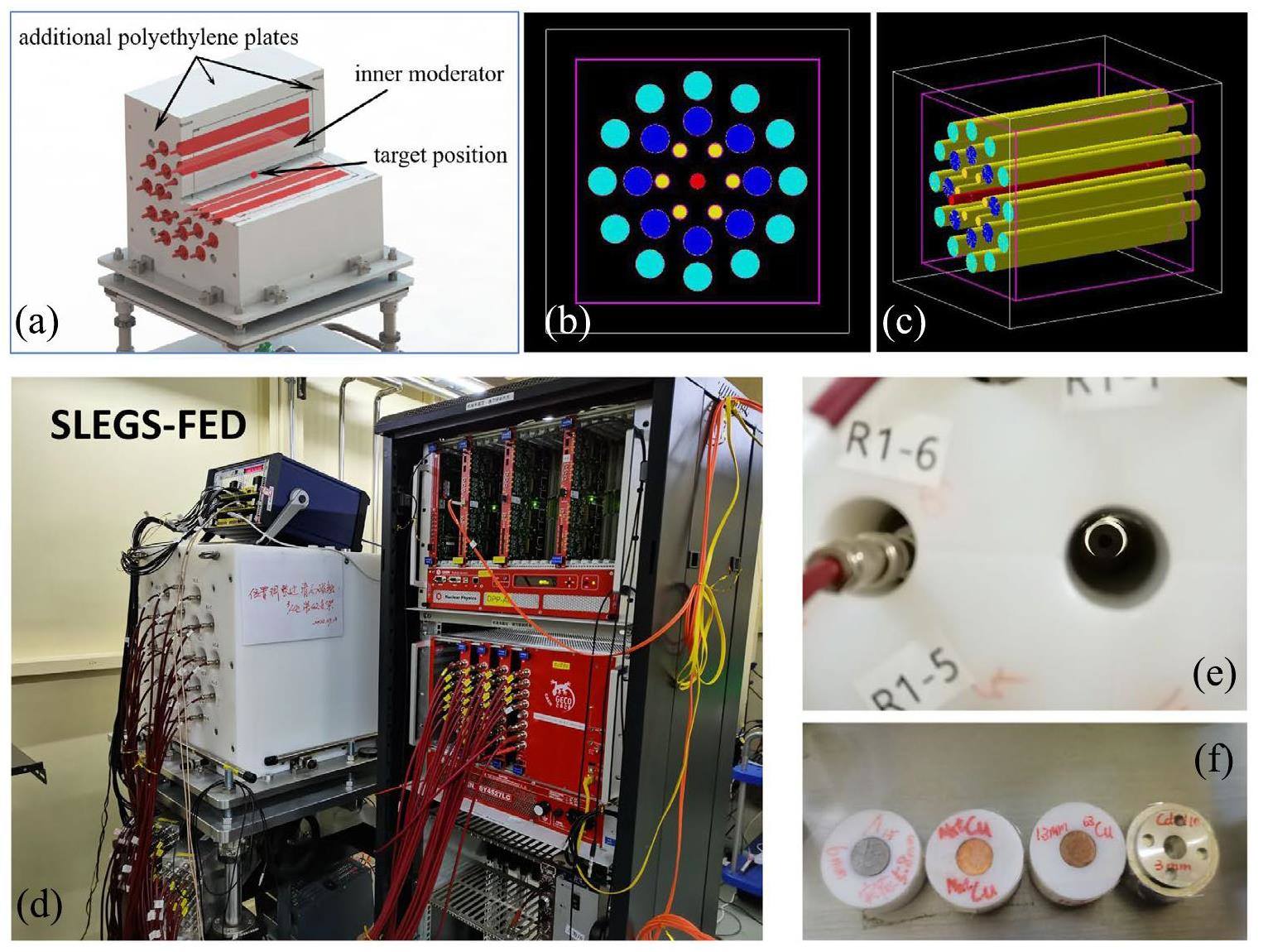

Photonuclear data primarily comprise photoneutron data, which are generated from the main excitation mode of the giant dipole resonance associated with the collective motion of atomic nuclei and form the most prominent region of the excitation function curve. At the SLEGS, photoneutron data are predominantly measured using a flat-efficiency detector (FED) array. Collimated γ-rays irradiate the reaction target—typically Φ (6–10) mm × (0.1–100) mm)—which is precisely positioned at the geometric center of the FED. The photon-induced neutrons are then moderated by polyethylene and subsequently captured by the 3He proportional counters. Meanwhile, residual γ-rays are attenuated by an external copper attenuator and detected using either a LaBr3 detector (Φ 3 inch × 4 inch) [16] or bismuth germanate (BGO) detector (Φ 3 inch × 200 mm) [17].

The FED array, specifically designed for photoneutron measurements, is illustrated in Fig. 2). It consists of 26 3He proportional counters embedded in a high-density polyethylene block measuring 500 mm in length, 450 mm in width, and 450 mm in height. This polyethylene block is enclosed from all six sides by 2-mm-thick cadmium layers to absorb thermal neutrons from the environment. A 50-mm-thick outer layer of polyethylene further encapsulates the entire assembly. A beam channel with a diameter of 26 mm is located at the center of the moderator. The experimental target is placed at the center of this channel. Geant4 simulation studies have revealed that small variations in the target position have minimal effect on neutron measurements. The 3He proportional counters are arranged in three concentric rings at radial distances of 65, 110, and 175 mm from the center. The inner ring (Ring-1 or R1) comprises six counters, each measuring 25.4 mm in diameter and 500 mm in length. The middle ring (Ring-2 or R2) contains eight counters, each with a diameter of 50.8 mm and a length of 500 mm. The outer ring (Ring-3 or R3) includes twelve counters identical in dimensions to those in the middle ring. All 26 counters are filled with 3He gas at a pressure of 2 atm.

The 3He proportional counters operate at a voltage of 950 V for R1 and 1050 V for R2 and R3. The high voltage is provided by CAEN’s A1589 module [18] housed in the SY4527LC [19] high-voltage power crate.The system employs a total of three preamplifier modules, each integrating 16 channels. To account for the long decay time characteristic of 3He proportional counters, the system applies waveform truncation, causing the output signal to decay rapidly after peaking. This approach minimizes system dead time.

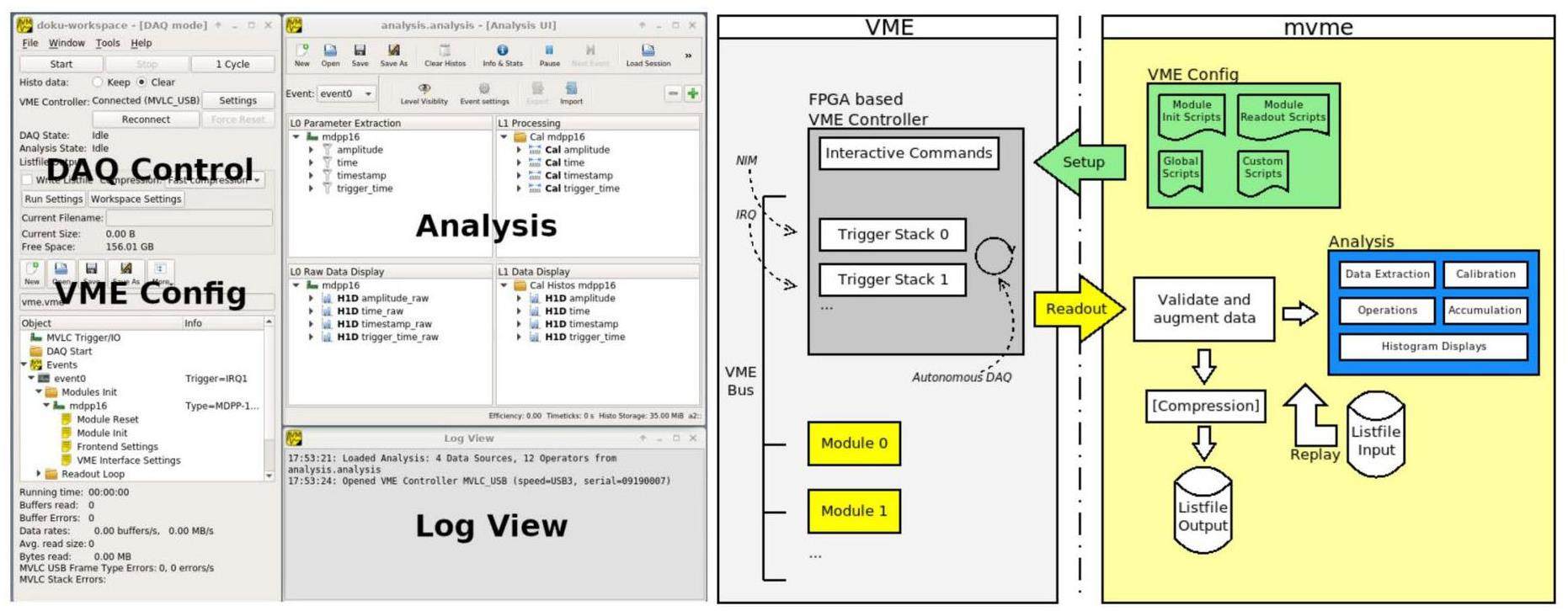

Digital signal processing was performed using Mesytec’s MDPP-16 [20] and MVME [21] DAQ systems. The MDPP-16 system is a standard DAQ module with embedded firmware, a standard charge-integrating preamplifier, a peak-sensing analog-to-digital converter (PADC), and other digital processing equipment. It directly converts collected waveform data into digital outputs such as amplitude or area. Within the MDPP-16 system, signals from the charge-sensitive preamplifier are first subjected to gain modification and low-noise amplification before being digitized by an 80-MHz ADC. The resulting digital signal is then processed by FPGA firmware for signal reconstruction. During signal reconstruction, built-in trapezoidal and fast-time filtering algorithms are employed to extract energy and timing information. The MVME DAQ system captures data in a compressed binary format, which must be decompressed and converted into the CERN ROOT [22] format using a dedicated code before analysis. The MVME data are archived in *.zip files, which include the raw binary data in the *.mvlclst format, an MVME analysis file (analysis.analysis), a log file (messages.log), and a notes file (mvme_run_notes.txt). Although the raw binary data in the *.mvlclst format can be directly decoded by MVME, this system is not suitable for detailed analysis. To enable comprehensive processing, we developed a decoding program that converts the binary files into the CERN ROOT format according to the MDPP-16 manual [20]. The resulting CERN ROOT file contains a single TTree named Tree;1, with branches for the following: ADC (signal pulse height), Ch (MDPP-16 channel number), Flag (pile-up, overflow, or underflow indicator), Mod (MDPP-16 identifier, with two MDPP-16 modules overall), time-to-digital converter (TDC; signal timestamp), CFD (TDC time difference), dt (time interval between consecutive events), and EvN (debug variable; 0 indicates normal operation). Among these, the ADC is used in neutron Q-spectra analysis. Ch and Mod are used to identify the signal source. The TDC is applied in period and coincidence analysis during DNM sorting for (γ, xn; x=2, 3, ...) reaction measurements.

All measurements were performed using MVME, a ready-to-run, platform-independent, open-source DAQ software package that supports hardware configuration, run control, and online monitoring. A screenshot of the MVME interface and an operational block diagram are presented in Fig. 3. Most hardware settings, programmed into matching VME registers, are pre-configured, enabling a short learning curve. To achieve high data rates, the MVME software leverages the list sequencer mode of the MVLC controller. Online data monitoring and visualization are supported through a three-level analysis framework that enables calibration, basic calculations (e.g., sum and ratio determination), and one- and two-dimensional histogramming. A built-in scripting language allows users to create plug-in processes for complex data manipulation. Data rates of up to 50 MB/s can be achieved. For the MDPP-16 system, this enables recording rates of 1 MHz during amplitude and time information collection when five channels respond simultaneously during a single event.

The FED DAQ system comprises four primary components. The first component is the DAQ control interface. It allows users to start or stop data acquisition, configure the MVLC connection mode with DAQ electronics, enable or disable data recording, set the acquisition time, assign a name for the recorded data file, and specify whether the file is segmented by time or size. The second component is the VME electronic parameter configuration interface. It configures the two MDPP-16 waveform digital samplers by setting hardware-matched addresses and firmware modes. This interface also helps set signal filtering parameters, including integration time, differentiation time, amplification time, rise time, and attenuation time. The third component is the data analysis interface. It enables users to select the data source, perform logical operations, and generate one- or two-dimensional histograms. The fourth component is the log interface. It displays operational details during data acquisition, including the start and stop times and the configured electronic parameters. If an error occurs during data acquisition, it is highlighted in red text, enabling users to identify the underlying cause using the displayed information.

The BGO or LaBr3 detector, used for γ-ray detection, is powered by the A1589 module. Signals from these detectors are processed by the DT5730B digitizer module, with data acquisition managed by the CoMPASS system, typically configured to operate in Pulse Height Analysis (PHA) mode. Acquired data is saved directly in CERN ROOT format. The resulting ROOT file contains a single TTree named Data_R. For preliminary processing, three key branches are commonly utilized: The Channel branch identifies the DT5730B acquisition channel; The Timestamp branch records event arrival times in picoseconds; The Energy branch represents the pulse amplitude of detected signals.

Uncertainty analysis of the FED array

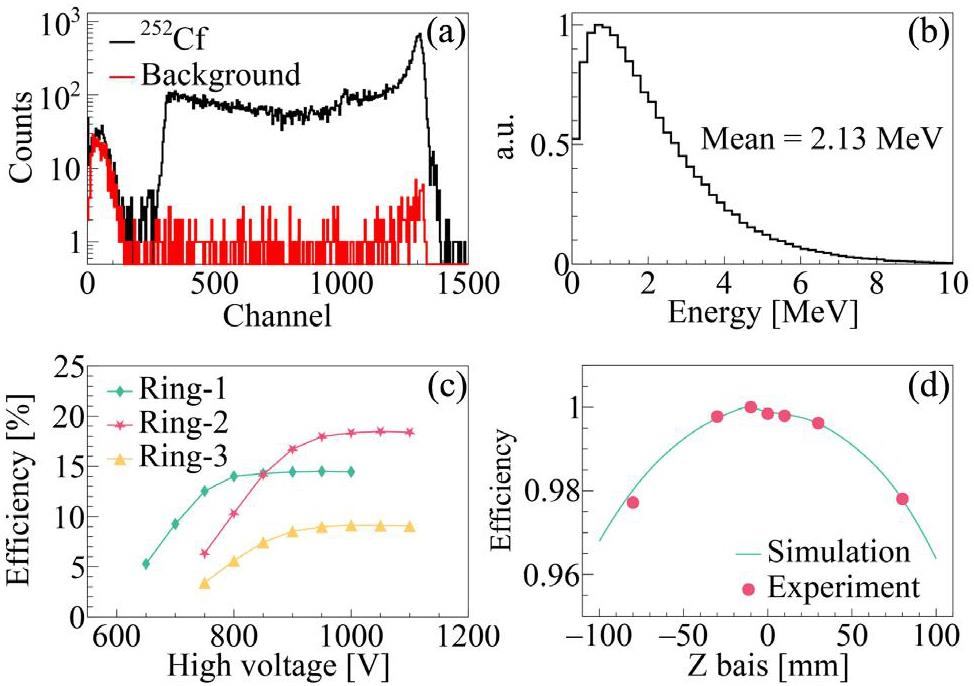

In photoneutron cross-section measurements, the primary sources of uncertainty include the fidelity of the energy spectrum of the incident γ-ray, uncertainty in neutron counts, and the thickness and density of the target. Among these, the uncertainty in neutron counts arises from statistical variations, the neutron-count extraction algorithm, and systematic uncertainty in the FED efficiency. This systematic uncertainty is influenced by voltage setting, target position, acquisition system configuration, and detector systematic fluctuations. Previously, a detailed study was performed on FED’s systematic uncertainty using a 252Cf source with a neutron emission rate of 361.3 ± 10.8 counts/s. The FED was aligned in the experimental hutch to maintain the same environmental background as in the simulation experiment. Figure 4(a) presents a typical pulse height spectrum recorded by one of the 3He proportional counters in the FED. Figure 4(b) displays the simulated neutron energy distribution of a 252Cf standard neutron source.

The 3He proportional counters need to be operated in the proportional region, where the detector efficiency exhibited only a weak dependence on applied high voltages. The efficiency of each detector in each ring was measured for multiple high-voltage settings, with each setting applied for 1 h. The optimal operating voltages were determined to be 950 V for R1 and 1050 V for R2 and R3. The total detector efficiencies were 41.92 ± 1.25%, 42.10 ± 1.25%, and 41.91 ± 1.25% (statistical error only) for high-voltage deviations of -50 V, 0 V, and 50 V, respectively. These results indicated that the detector efficiency varied only slightly with a 50-V shift in applied high voltages. Assuming a linear dependence of the detector efficiency on applied high voltages, the detector systematic uncertainty introduced by high-voltage variations was estimated to be 0.02% given that the CAEN A1589 module limited voltage deviation to less than 1 V.

The uncertainty associated with target position variations was evaluated by displacing the 252Cf source along the central tunnel of the FED moderator. The dependence of the detector efficiency on source position is presented in Fig. 4(d). The observed asymmetry in the efficiency distribution was attributed to the asymmetrical construction of the detector. The efficiency remains stable when the source is displaced slightly around the central position. A displacement of 1 cm contributed 0.10% to the systematic uncertainty originating from target position variations.

In addition to the uncertainties discussed above, measurement deviations may also result from different parameter configurations in the DAQ system. Fine-tuned parameters and corresponding detector efficiencies are presented in Table 1. These parameters have been shown to be effective for signal amplification and display minimal correlation with detector efficiency. Based on extended continuous measurements, the detector system was confirmed to be stable, with an observed efficiency fluctuation of 0.26%. Table 1 summarizes the upper limits of the uncertainties associated with the detector system. The uncertainty associated with a maximum high-voltage deviation of 1 V was 0.02% and that associated with a maximum deviation of 1 cm between the target position and geometric center was 0.10%. The total systematic uncertainty of the FED was 3.02%, which was obtained by quadratically summing the uncertainties listed in Table 1 with the 252Cf activity uncertainty being 3.0%.

| Uncertainty factors | Value |

|---|---|

| High voltage | 0.02% |

| Preset DAQ parameters | 0.17% |

| Target position variation | 0.10% |

| Efficiency fluctuation | 0.26% |

| 252Cf activity uncertainty | 3.0% |

| Total uncertainty | 3.02% |

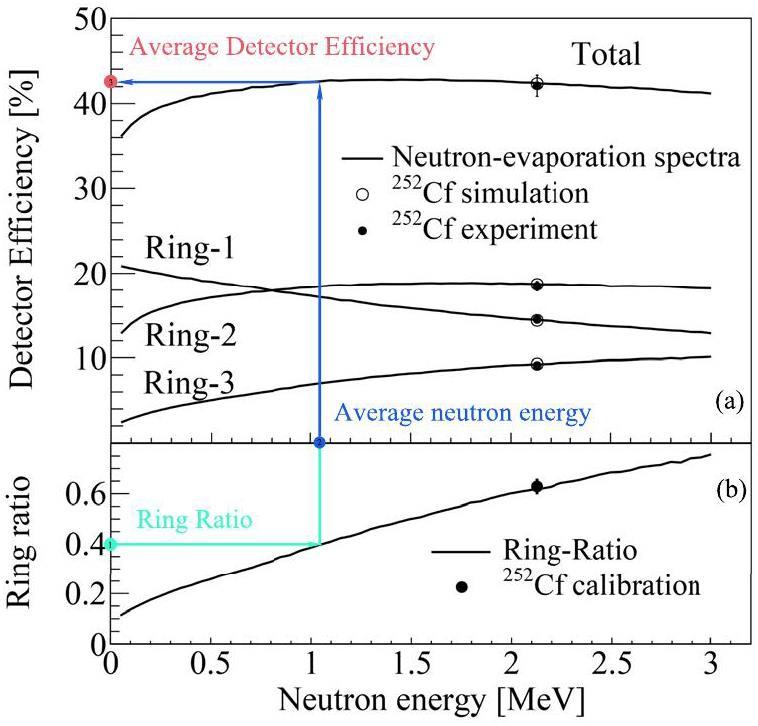

Figure 5 presents the simulated efficiency curve based on the detector geometry described in Fig. 2. As depicted, the total detector efficiency increases from 35.64% at 50 keV to 42.32% at 1.65 MeV, following which it gradually decreases to 40.69% at 3 MeV for neutrons whose energy follows the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution. The efficiency calibrated using the 252Cf source—42.10 ± 1.25%—is marked on the curve at 2.13 MeV, which is the average energy of the 252Cf neutron spectrum. In the experiment, the average neutron energy was estimated using the RR technique [23-26]. The RR is defined as the ratio of counts in the outer ring to those in the inner ring, as illustrated in Fig. 5(b). Although the RR method yields only an approximate average energy, which may differ from the actual value, the flat-efficiency profile ensures that the resulting uncertainty in the detector efficiency remains minimal.

Photoneutron Cross-Section Data Analysis

The photoneutron cross-section is defined as follows:

Data preprocessing

Nn and the Nγ denote measurement parameters obtained from the FED and BGO (or LaBr3) detector. In the data analysis program, the energy spectrum of the γ-rays incident on the target is reconstructed. This process yields Nγ and the normalized energy distribution, which are essential for determining monochromatic cross-sections. Furthermore, Nn can be obtained by analyzing the time distribution of detector signals as the laser operates in the pulsed mode and the DAQ system records a timestamp for each detector signal. This section outlines the method used to extract Nn and Nγ.

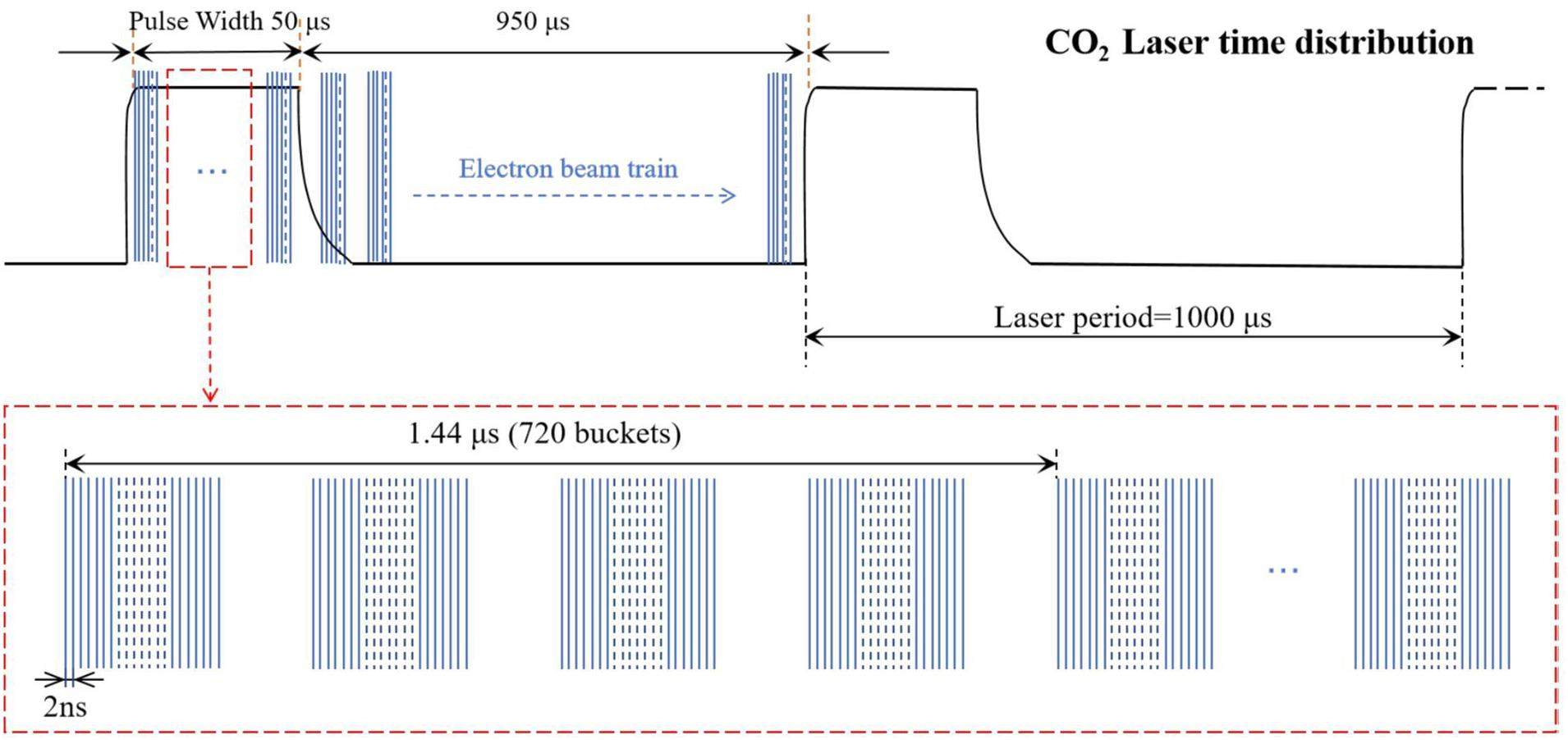

The SSRF operated in the top-up mode. Its storage ring had a circumference of 432 m, and electrons completed one revolution in 1.44 μs. The electron beam was divided into 720 buckets, of which approximately 500 were filled with electron bunches. These bunches were organized into four groups, with a 2-ns interval between adjacent bunches within each group. The CO2 laser operated in the pulsed mode with a dedicated trigger, typically delivering 5 W of power at a period of 1000 μs and pulse width of 50 μs. Figure 6 illustrates the time distribution of the laser and electron beams.

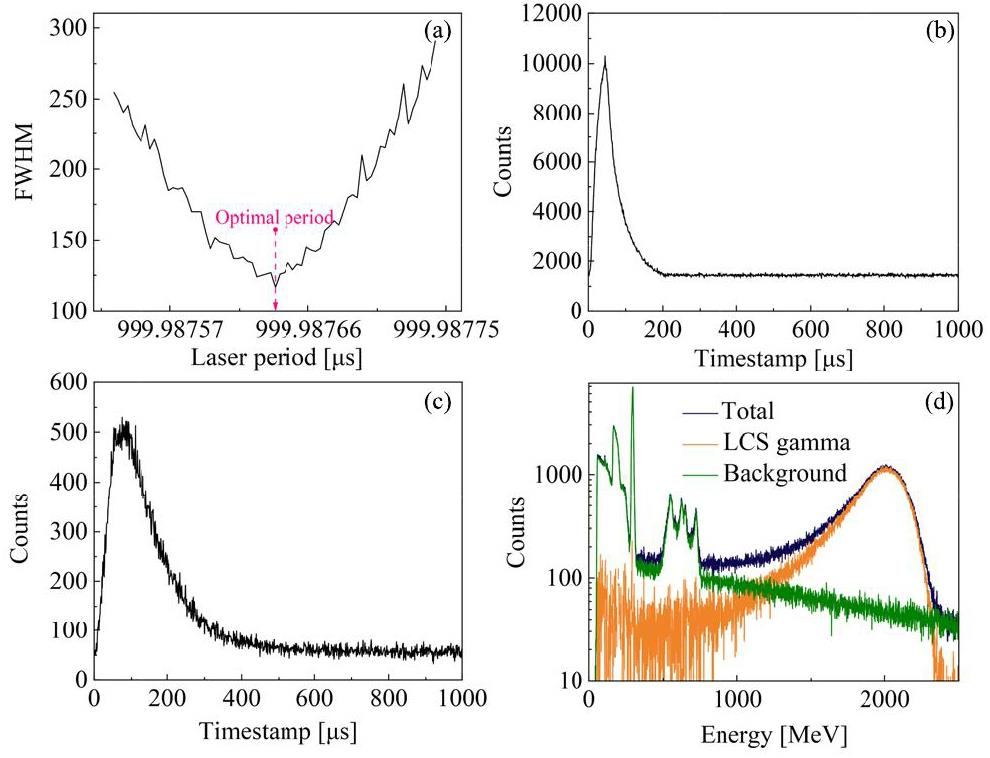

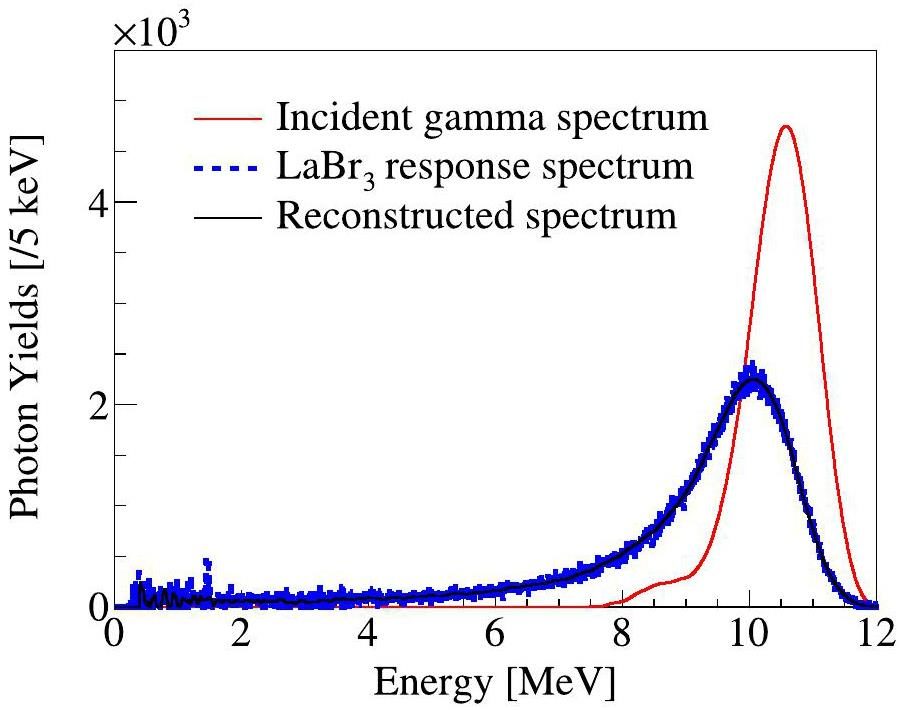

The laser period was set to 1000 μs, although minor deviations were observed. While the deviations did not impact the analysis results, accurately determining the laser period corresponding to each data file was necessary to obtain the correct time distribution of the detector signals in a single laser period. This was accomplished by setting a range of period values and selecting the one that produced the narrowest full width at half maximum (FWHM) in the time distribution spectrum, as depicted in Fig. 7(a). The background was then subtracted using the time distribution corresponding to this optimal period. Nn was directly extracted from the neutron time distribution spectrum (Fig. 7(c)). Further, the γ-ray time distribution spectrum (Fig. 7(b)) was used to extract the LCS γ-ray source spectrum from the electron bremsstrahlung background, which was the LCS detector response spectrum (orange line in Fig. 7(d)). Subsequently, the energy spectrum of the γ-rays incident on the detector was computed using the direct unfolding method [27]. Figure 8 presents the energy spectrum obtained via the direct unfolding method (red solid line), detector response spectrum (blue dashed line), and reconstructed spectrum (black solid line). The energy spectrum of γ-rays incident on the target was then calculated based on the thickness and attenuation coefficients of the attenuator (Cu) and target. Integrating the energy spectrum of γ-rays incident on the target yielded Nγ.

In the Nn extraction algorithm, each ring is analyzed independently as the RR technique requires neutron counts from R3 and R1. As indicated by the colored arrows in Fig. 5, the R3-to-R1 count ratio is first obtained (cyan dot). The average neutron energy is then obtained from the RR curve (blue dot). Finally, the average neutron efficiency ϵn is determined from the efficiency curve (red dot). The right-hand side of Eq. 1 is referred to as the monochromatic approximation cross-section (also called the folded cross-section) as the incident γ-rays are quasi-monochromatic.

Monochromatic photoneutron cross-sections

The monochromatic approximation cross-section is a weighted average of cross-sections, with weights defined by the normalized energy spectrum of the incident γ-rays. This section outlines the algorithm used to extract monochromatic cross-sections. The monochromatic approximation cross-section can be expressed as follows:

(1) First, initialize σ with a value, e.g., [1,1,1,...,1]T, and denote it as σ0. Subsequently, substitute it into Eq. 3 to obtain

(2) Then, update σ0 based on the difference between σexp and

(3) Each subsequent iteration follows the same procedure:

Technical Validation

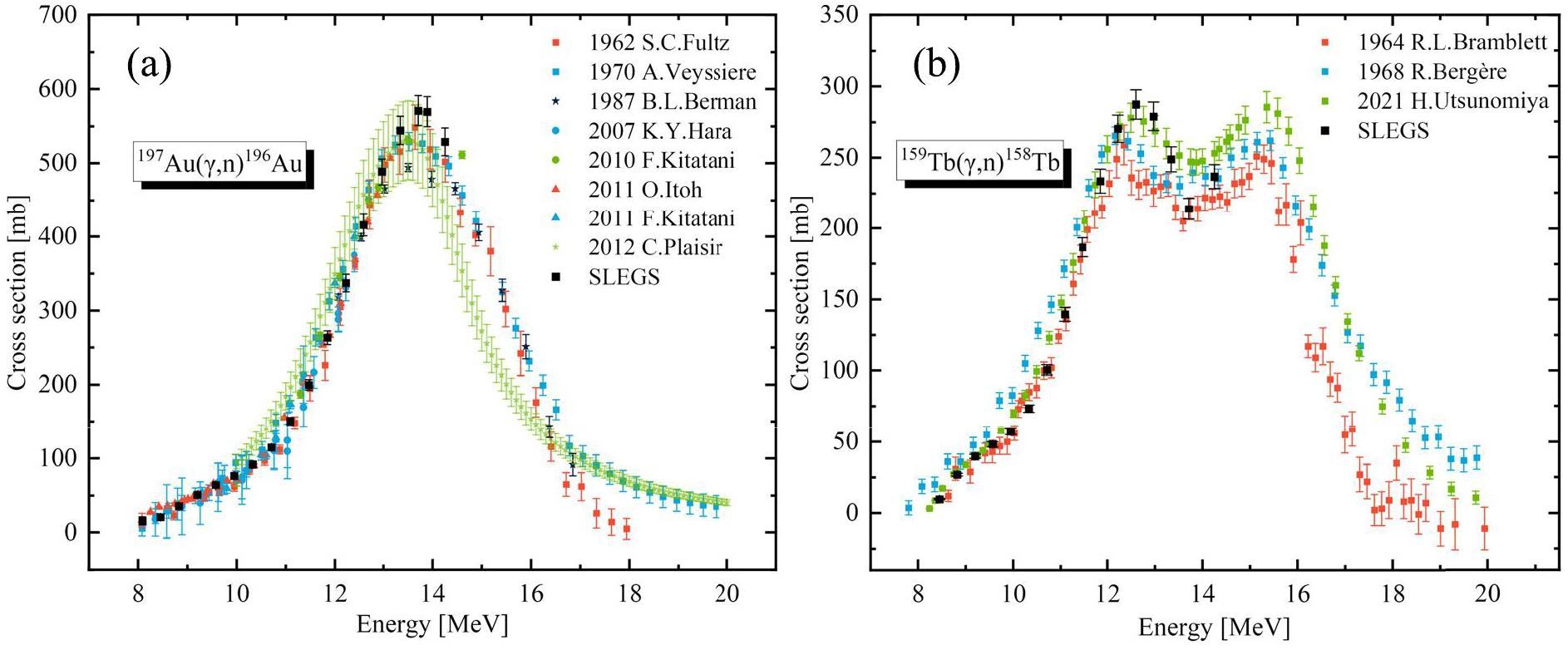

Figure 9 shows the monochromatic cross-sections of 197Au and 159Tb obtained from the SLEGS experiment and those obtained from other experiments. The SLEGS data have been published previously [28], they are included here solely to validate the data processing methodology detailed in this paper.

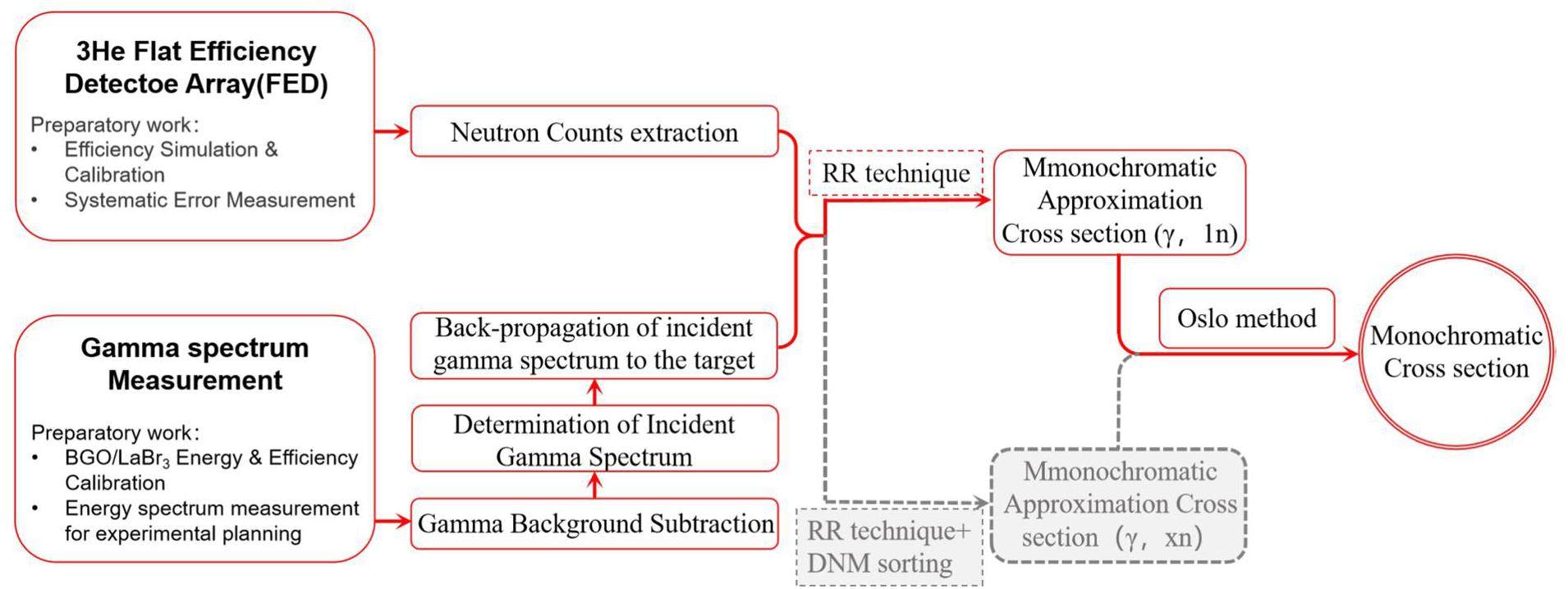

The overall process of photonuclear neutron cross-section measurement and data analysis is illustrated in Fig. 10. Note that the methodology for measuring the (γ, 2n) cross-section is still under development (indicated in gray). A series of photoneutron experiments at the SLEGS has been performed, and the measurement data are currently being analyzed. The results will be progressively released for public access and validation, particularly to support photonuclear data compilation and evaluation in the Chinese nuclear database (CENDL/PD).

Figures & Tables

The primary parameters used for photoneutron cross-section measurements at the SLEGS are listed in Table 2. Two types of photoneutron spectrometers are used at the SLEGS: the FED and neutron TOF spectrometer. The methodology of the spectrometer is still under development. The SLEGS has also developed nuclear resonance fluorescence and light charged particle spectrometers. The corresponding datasets have unique characteristics and will be presented in future studies.

| Parameter | Value or Mode |

|---|---|

| Electron energy (GeV) | 3.5 |

| Beam current (mA) | 180–220 |

| SSRF operation mode | Top-up or Decay |

| CO2 laser power (W) | 5-20-100 (Adjustable) |

| Duty cycle (μ) | 50/1000 (Adjustable) |

| Coarse collimator diameter (mm) | 0–5, 8, 10, 20, 30 (Adjustable) |

| Fine collimator diameter (mm) | 0–30 (Adjustable) |

| Three-hole collimator diameter (mm) | 1, 2, 3 |

| Internal copper attenuator (mm) | 0–640 (Adjustable) |

| External copper attenuator (mm) | 0–1000 (Adjustable) |

| X-ray spot monitor | MiniPIX |

| γ-ray spot monitor | Gamma Spot Monitor (GSM) |

| Gamma beam flux monitor | LaBr3 or BGO |

| Gamma beam flux DAQ system | CAEN CoMPASS |

| Photoneutron detector array | FED |

| FED array neutron data DAQ system | Mesytec MVME |

Usage Notes

1. Photoneutron reactions are one of several reaction channels in photonuclear processes. The SLEGS can help measure (γ, 1n) cross-sections. However, the methodology for (γ, 2n) cross-section measurements is still under development. Owing to energy limitations at the SLEGS, reactions beyond (γ, 2n) are not allowed.

2. The quasi-monochromatic cross-section is a weighted average, with weights determined based on the normalized incident gamma spectra. Consequently, fine structures in some cross-sections may be smoothed out.

3. The (γ, 1n) photoneutron cross-section unfolding program can extract monoenergetic cross-sections at the measured energy points and provide values within the measured energy range. Additionally, it can predict cross-sections slightly beyond the measured energy range.

4. The raw data for 197Au(γ,1n) and 159Tb(γ,1n) have been uploaded to the Science Data Bank [29, 30]. This dataset is the experimental raw data generated by MVME/DT5730B and corresponding attenuation thicknesses, from which neutron counts and gamma counts (gamma spectra) can be extracted. The monochromatic cross section data are available in Ref. [31].

5. The neutron time-of-flight (TOF) spectrometer at the SLEGS is currently under research. It is designed to measure neutron energies and provide information on the energy levels of reaction products as well as to measure the angular distribution of photoneutrons.

Photonuclear production of medical radiometals: a review of experimental studies

. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 328, 493-505 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-021-07683-2Progress of photonuclear cross sections for medical radioisotope production at the SLEGS energy domain

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 187 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01339-4Atlas of photoneutron cross sections obtained with monoenergetic photons

. Atom. Data Nucl. Data Tables 38, 199-338 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-640X(88)90033-2TENDL: Complete nuclear data library for innovative nuclear science and technology

. Nucl. Data Sheets 155, 1-55 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nds.2019.01.002ENDF/B-VIII.0:The 8th major release of the nuclear reaction data library with CIELO-project cross sections, new standards and thermal scattering data

. Nucl. Data Sheets 148, 1-142 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nds.2018.02.001Japanese evaluated nuclear data library version 5: JENDL-5

. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 60, 1-60 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1080/00223131.2022.2141903CENDL-3.2:The new version of Chinese general purpose evaluated nuclear data library

. EPJ Web of Conferences 239, 09001 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/202023909001Collimator system of SLEGS beamline at Shanghai Light Source

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. Sect. A 1013,Interaction chamber for laser Compton slant-scattering in SLEGS beamline at Shanghai Light Source

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. Sect. A 1033,The SLEGS beamline of SSRF

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 111 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01469-3Gamma spot monitor at SLEGS beamline

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A 1068,Development and prospect of Shanghai Laser Compton Scattering Gamma Source

. Nuclear Physics Review (In Chinese) 37, 53-63 (2020). https://doi.org/10.11804/NuclPhysRev.37.2019043Commissioning of laser electron gamma beamline SLEGS at SSRF

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 87 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01076-0Overview of SSRF phase-II beamlines

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 137 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01487-1DIAMOND C/Cx Series, low power CO2 Lasers

, https://www.coherent.com/lasers/co2/diamond-c-cx-seriesShanghai SICCAS high technology corporation

, http://www.siccas.com/bgo.aspx?pId=42CAEN A1589, 8 Channel ± 2.5 kV/500 μA 4 Quadrant Bipolar Board

, https://www.caen.it/products/a1589/CAEN SY4527LC, Universal Multichannel Power Supply System (Low Cost)

, https://www.caen.it/products/sy4527lc/Mesytec MDPP-16, fast high resolution time and amplitude digitizer

, https://www.mesytec.com/products/nuclear-physics/MDPP-16.htmlMesytec MVME - Mesytec VME Data Acquisition

, https://www.mesytec.com/downloads/mvme.htmlROOT: analyzing petabytes of data, scientifically

. https://root.cern.ch/Photoneutron Cross Sections for 90Zr, 91Zr, 92Zr, 94Zr, and 89Y

. Physical Review 162, 1098 (1967). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.162.1098Measurements of the giant dipole resonance with monoenergetic photons

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 47, 713-761 (1975). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.47.713Photoneutron cross sections for Au revisited: Measurements with laser Compton scattering γ-rays and data reduction by a least-squares method

. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 48, 834-840 (2011). https://doi.org/10.3327/jnst.48.834Photoneutron cross-section measurements in the 209Bi (γ, xn) reaction with a new method of direct neutron-multiplicity sorting

. Phys. Rev. C 96,Energy profile of laser Compton slant-scattering γ-ray beams determined by direct unfolding of total-energy responses of a BGO detector

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A 1063,The day-one experiment at SLEGS: systematic measurement of the (γ,1n) cross sections on 197Au and 159Tb for resolving existing data discrepancies

. Science Bulletin. Accepted.197Au(γ,n) cross section RAW data

[DS/OL]. V1. Science Data Bank, 2025[159Tb(γ,n) photoneutron cross section RAW data

[DS/OL]. V1. Science Data Bank, 2025[197Au(γ,n) and 159Tb(γ,n) cross section

[DS/OL]. V1. Science Data Bank, 2025[Hong-Wei Wang is an editorial board member for Nuclear Science and Techniques and was not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.