Introduction

As a critical rare material, beryllium is extensively utilized in alloys, electronics, and computer industries [1, 2]. Currently, the total resources of beryllium in the world are about 3.383 million tons, and proven mineral reserves account for 1.164 million tons [3]. Beryllium is listed by the European Union as one of the 14 most critical mineral resources [4]. With the increasing demand for beryllium in the world and the continuous increase of mineral resources exploitation, the mining geological environment has been increasing concern by government and investigators because of the extremely high toxicity of beryllium. Several investigators reported that Be(II) migrated easily into the environment, mainly through ore mining, weathered rocks and minerals, and coal pile leaching [5-7]. Hence, beryllium would inevitably migrate from mineral resources to water resources to produce substantial quantities of wastewater containing beryllium. It is well known that beryllium is a highly toxic metal, and humans exposed to beryllium for long periods are susceptible to beryllium lung disease and cancer [8]. Additionally, beryllium would also contaminate agricultural ecosystems and seriously disrupt the growth of crops [9, 10]. WHO displays that the maximum allowable limit for beryllium wastewater discharge would be 0.012mg·L-1 (Guidelines for Drinking-Water Quality). Therefore, the treatment of U/Be wastewater has become more and more urgent. On the other hand, there exist many metal cations (Zn(2), Mn(2), Ca(2), Fe(2), Na(1), and (6)) in U/Be wastewater, which would affect the removal of Be(II) [8]. As a result, the selective separation of Be(II) from U/Be solutions is very challenging due to the low concentration and coexistence of multiple ions.

At present, the treatment of U/Be wastewater is mainly performed by adsorption, precipitation, and biological approaches. Among them, adsorption is the optimal methodology due to its advantage in purifying solutions with low concentrations. Sun et al. [11] found that activated sludge could adsorption Be(II) from U/Be solutions and the reported adsorption capacity Qe value of the activated sludge was 14.4mg·g-1. Mahmoud et al. [12] employed chitosan to adsorb Be(II) and the Qe of chitosan was 44.96 mg·g-1. Zhao et al. [13, 14] utilized modified biochar for the treatment of U/Be wastewater and reached maximum adsorption capacity Qe (45.68mg·g-1 and 32.86 mg·g-1) under neutral conditions. In conclusion, the adsorbents currently reported for Be(II) generally have a Qe of lower than 50 mg/g. The low adsorption capacity and economics of the reported adsorbents limited their application. Therefore, the design and preparation of economical and environmentally sound adsorbents with high selectivity and adsorption capacity are crucial for the treatment of U/Be wastewater.

Previous investigations [15, 16] revealed that Be(II) exhibited a strong coordination property with hard O donor atoms. De and Krishnamoorthy [17, 18] reported that Be(II) is capable of forming stable complexes with phosphate and ammonia to produce precipitation. On the other hand, it is well known that the N, O, and S donor atoms in the carbon side chains of amino acids can be considered as active sites. Owing to the excellent complexation ability of amino acids, Sarvar et al. [19] utilized eight amino acids for gold leaching. Considering the strong coordination affinity of Be(II) with the N donor atom, this paper aims to propose the possibility of constructing a phosphate-based adsorbent functionalized by amino acid for the selective adsorption of Be(II) from U/Be solutions in an innovative way.

In this paper, a green, energy-saving, and efficient adsorption material with high selectivity is prepared for the removal of beryllium towards impurity ions from the aspect of functional group design. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time for an amino acid to be utilized as an adsorbent. Before this, phosphates were broadly utilized for the determination of beryllium [17, 18], and the results showed that phosphate has a strong binding ability to beryllium. Therefore, we speculate that phosphate can be effectively employed for the removal of beryllium from the solution. The main concept of the present investigation is to design and prepare an effective adsorbent via one kind of amino acid and calcium phosphate, which provide nitrogen and phosphorus sources for the coordination of Be(II). The crucial goal is to achieve the selective removal of beryllium from U/Be solutions. The removal and separation behaviors of Be(II) from U/Be solutions with the as-prepared absorbent material (named as CP@Glycine) were examined by using batch experiments. The adsorption thermodynamics and kinetics of Be(II) with CP@Glycine were also determined. Besides, the adsorption selectivity of Be(II) towards Fe(2), U(6), Zn(2), Mn(2), Na(1), and Ca(2) was also methodically explored. The removal mechanism was thoroughly investigated by the combination of different characterizations. At the same time, the adsorption capacity of CP@Glycine is 66 mg·g-1, which is higher than the largest known adsorbent (Qe=55 mg·g-1) [15]. In addition, DFT investigations were used in this study to explore the possible coordination interactions between Be(II) and the ligands from CP@Glycine. Based on the above studies, a novel environmentally sound beryllium separation technology would be established and the adsorption mechanism would be discovered at atomic level.

Experiment

Materials

Glycine (Gly) (C2H5NO2, purity: 99%, CAS Number: 56-40-6), ZnCl2 (purity: 98%, CAS Number: 7646-85-7), MnSO4·H2O (purity: 98%, CAS Number: 10034-96-5), FeSO4 (purity: 90%, CAS Number: 10034-96-5), CaCl2 (purity: 96%, CAS Number: 10043-52-4), NaCl (purity: 99%, CAS Number: 7647-14-5), phosphoric acid (H3PO4, purity: 85%, CAS Number: 7664-38-2), BeO (purity: 99%, CAS Number: 1304-56-9), Ca(OH)2 (purity: 99%, CAS Number: 1305-62-0), were purchased from China Shanghai McLean Biochemistry Co., Ltd.

Preparation of CP@Glycine

The CP@Glycine was prepared by the following procedure. 1 g of glycine was dissolved in 25 mL of deionized water and then 1.5 g of calcium hydroxide was added to the mixture. After stirring at 65 ℃ for 2 hours, 1.5 g of phosphoric acid was poured uniformly and the mixture was then rapidly mixed. The obtained uniform solution was heated in an oven at 105 ℃ to dry and turn into a powder. The CP@Glycine powder prepared in this way was mostly used to remove Be(II) in U/Be solutions.

The preparation process of the adsorbent does not produce any toxic and harmful gases, and can efficiently remove beryllium from beryllium-containing wastewater.

Solution Preparation

According to previous studies [20], U/Be wastewater usually contains various elements such as Be(II), Zn(2), Mn(2), Ca(2), Fe(2), Na(1), and U(6). In the present investigation, U/Be solutions with low concentrations (5mg·L-1 and 10 mg·L-1) was appropriately prepared for batch experiments, adsorption kinetics, and thermodynamic studies, whereas mixed solutions containing Be, Zn, Mn, Ca, Fe, Na, and U (10mg·L-1-50 mg·L-1) were simulated for adsorption selectivity investigations.

Batch Experimental Analysis

The accuracy of results was demonstrated by the preparation of adsorbent, initial pH, amount of adsorbent, and adsorption of a simulated solution from U/Be solution. Three sets of parallel samples were utilized in batch experiments to verify the validity of the results. Batch test of

Adsorption Kinetics and Thermodynamics Studies

0.1 g of CP@Glycine was weighed and placed in 50 mL beryllium solutions (C0=10, 60, 180, 200, 220, 250, 300, and 350mg·L-1), then divided into 8 groups with three parallel samples in each group. The above solutions were placed in a constant temperature shaking table and then oscillated at 175 rpm at three temperatures (i.e., 15 ℃, 25 ℃ and 35 ℃) until arriving at the equilibrium. The adsorption kinetics of Be(II) were investigated with pseudo-first-order (PFO), pseudo-second-order (PSO), Elovich, and intra particle diffusion models. The adsorption kinetics and thermodynamic models refer to the equation section entitled "Equations" in the Supporting Information.

Adsorption Selectivity Studies

The mixed solutions containing Be, Zn, Mn, Ca, Fe, Na, and U (10mg·L-1-50 mg·L-1) were appropriately simulated for the adsorption selectivity studies. The selective adsorption performance of Be(II) from the solutions with CP@Glycine was evaluated using the dispersion coefficient, Kd (mL·g-1). The dispersion coefficient (Kd) can be calculated as follows [21]:

Results and discussion

Characterization

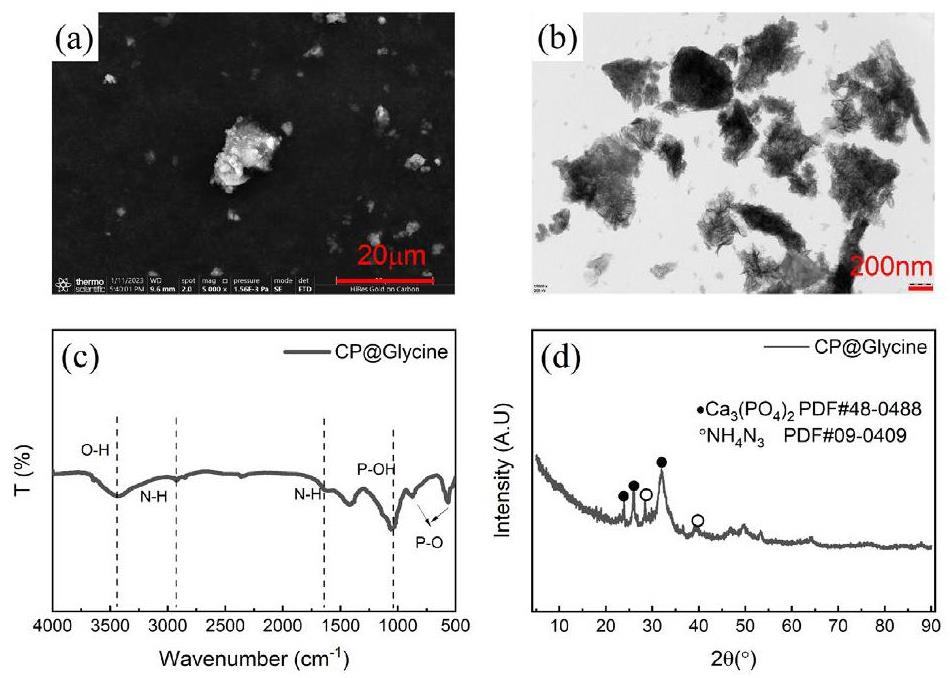

Figure 1(a) demonstrates the SEM analysis diagram of CP@Gycine, from which it can be seen that CP@Glycine shows good agglomeration and irregular shape. Figure 1(b) shows the results of the TEM analysis. The original sample showed an irregular shape, and the average particle size of about 200 nm, CP@Gycine particle size greater than compared with separate calcium phosphate [22, 23] and amino acids. This result may be related to the presence of amino acids that alter the growth of calcium phosphate.

Figure 1(c) illustrates the FT-IR analysis of CP@Glycine. The bending at 3400 cm-1 -3500 cm-1 was mainly attributed to O-H [24-26]. The vibration of the bands at 2900 cm-1 and 1650 cm-1 is essentially ascribed to the N-H bond [27, 28], whereas the vibration at 1060 cm-1 is mainly attributed to the P-OH bond [29]. At 1155 and 1343 cm-1, the characteristic band of in-plane bending of P-O-H has been presented [30]. The vibration of the bands at 890 cm-1 and 610 cm-1 is essentially attributed to the P-O bond [31].

Figure 1(d) shows the XRD analysis results of CP@Gycine, revealing multiple characteristic peaks. The presence of Ca3(PO4)2 (PDF#48-0488) leads to the characteristic peak at 2θ=24.2°, 25.6°, 32.2°, while NH4N3 (PDF#09-0499) leads to the characteristic peak at 2θ=29.3° and 38.8°. The obtained results by the SEM, TEM, FT-IR, and XRD revealed that the CP@Glycine sample was successfully prepared.

Batch Experiments

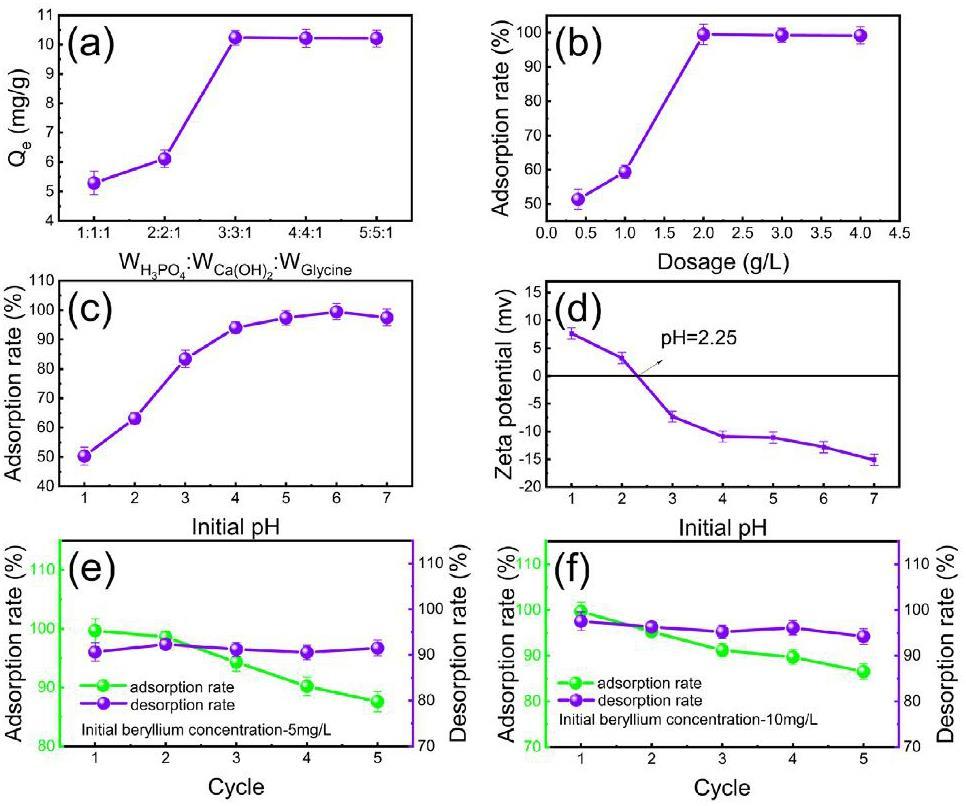

The preparation process of adsorbent significantly affects the adsorption effect. The results of the batch experiments are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Five different ratios were tested for sample preparation (

The amount of absorbent shows the economic benefits of the absorbent material. Figure 2(b) illustrates the effect of adsorbent dosage. The graph presents that the optimal adsorption rate (99%) is achievable in the case of 2mg·L-1 adsorbent. By this virtue, the adsorbent dosage in this experiment was set as 2mg·L-1.

The initial pH value of the solution influences the chemical properties and zeta potential of the adsorption process [21]. The plotted results in Fig. 2(c) reveal that the adsorption rate of Be(II) is positively correlated with increasing pH. The optimum initial pH appears at 6 and the removal efficiency of beryllium reaches 99%. This is because Be(II) mainly exists in the form of

The Be(II) desorption capacity and reusability of CP@Glycine were also studied. Figures 2(e-f) demonstrate that the removal efficiency of Be(II) decreases slightly, while the desorption rate of beryllium decreases during 5 adsorption-desorption cycles for both 5mg·L-1 beryllium solutions and then remains constant. In the first adsorption and desorption cycle, the removal efficiency of Be(II) is 99% and decreases to 90% (in cycle 3). After 5 cycles, the absorption rate of Be(II) remains 85%. The results indicate that the desorption rates of Be(II) during 5 cycles are above 90%. Therefore, CP@Glycine has good reusability in the experimental range, which proves that CP@Glycine has economic benefits and acceptable recycling performance.

Equilibrium Modeling

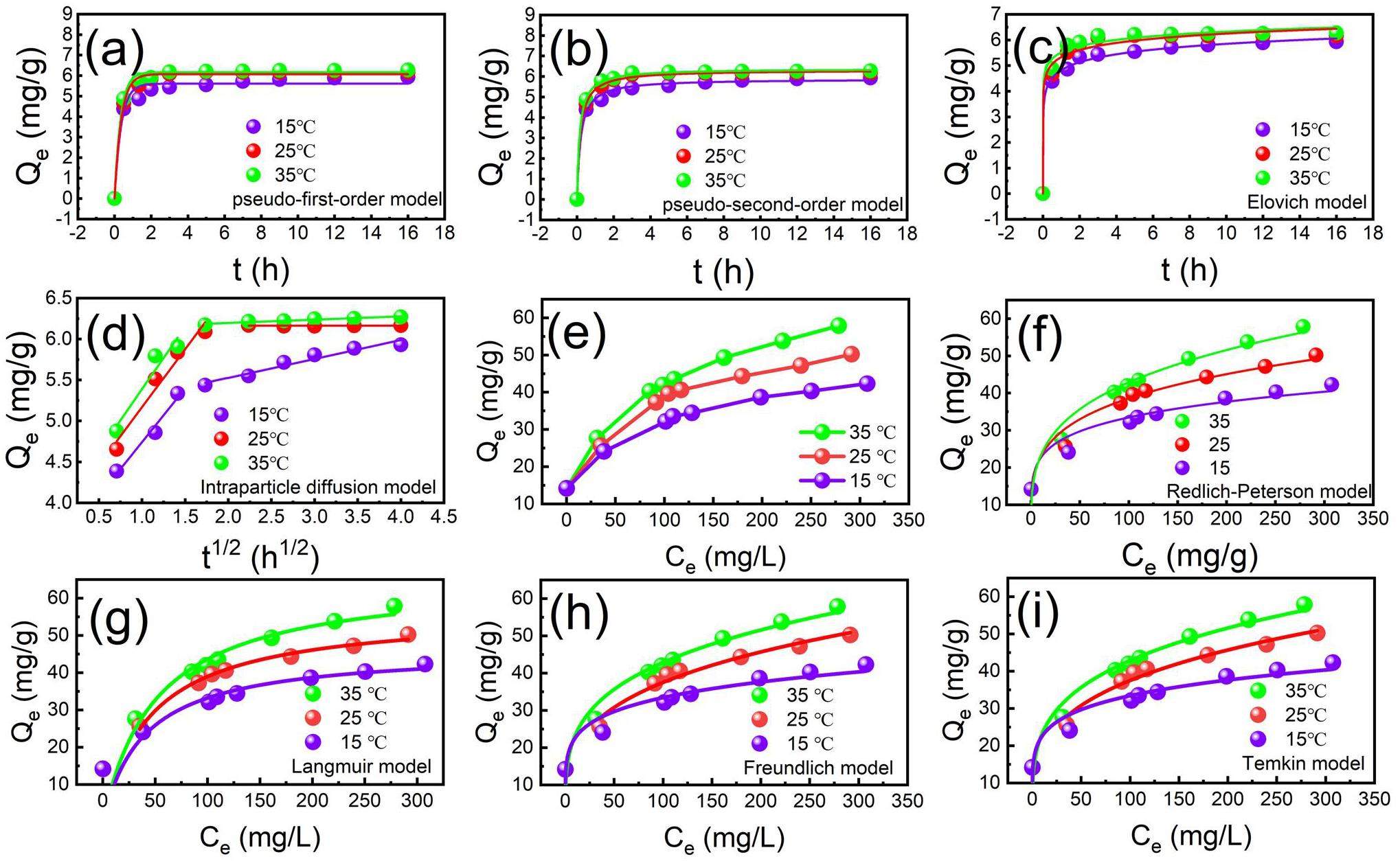

Adsorption kinetics are able to effectively react to the required retention time of the adsorbent. Four kinetic models, namely pseudo-first-order kinetics, pseudo-second-order kinetics, Elovich, and intra-particle diffusion, were used to fit the data of CP@Glycine adsorption of beryllium. Figs. 3(a-b) illustrates the fitting of the adsorption kinetics. The results showed that Be(II) is rapidly absorbed in the initial stage of adsorption. As CP@Glycine occupies many adsorption sites in the early stages, Be(II) is removed in solution [15]. As is seen, the PSO model (R2=0.999) is more suitable for fitting the Be(II) removal process by CP@Glycine compared to the PFO model (R2=0.993), intraparticle diffusion (R2=0.921–0.940), and Elovich (R2=0.987–0.996). In addition, the Chi-Square parameter (χ2) of the fitted model was lower, and the estimated Qe values were closer to the experimental data. This suggests that the removal process is regulated by chemisorption and physical adsorption at the same time [16].

Adsorption isotherms were also examined based on the Langmuir model, Freundlich model, Redlich-Peterson model, and Temkin model. Figure 3(c) illustrates that Qe and temperature exhibit a positive correlation with the initial concentration of beryllium. The fitting results of the adsorption isotherm models are demonstrated in Figs. 3(d-f), and the adsorption isotherm data are listed in Table S2. According to the relevant coefficient (R2), the Freundlich model (R2=0.961) is more suitable for fitting the Be(II) removal process with CP@Glycine for the tested temperature range than the Langmuir model (R2=0.830) at 35 ℃ [13]. At the temperature of 25 ℃, the Temkin model (R2=0.991) also seems suitable for fitting the adsorption process [32, 33]. By comparing the Chi-Square parameter (χ2) of the four equations, it can be seen that the χ2 values of Langmuir and Temkin at 25 ℃ are 0.75049 and 0.54103, respectively, which is much lower than that of Freundlich. However, the χ2 of Freundlich was lower than that of Langmuir and Temkin at 15 and 35 ℃. Therefore, the Redlich-Peterson model was introduced, which is a mixture of the Langmuir and Freundlich models [34]. Additionally, the experimental isotherm data fitted by the Redlich-Peterson model revealed that phosphoric acid adsorption on pyrolytic hydrocarbons does not follow the ideal monolayers or heterogeneous surface adsorption, but the mixed adsorption behavior of both. The maximum Qe of CP@Glycine for beryllium is obtained as 66mgg-1 at 35 ℃. Compared to other adsorbents, CP@Glycine exhibits a higher Qe for beryllium (Table S3). In addition, the cooperative effect of P-O with N-H and O-H may enhance the removal of beryllium by CP@Glycine.

Adsorption thermodynamics of Be(II) with CP@Glycine was also determined. According to Table S4, during the tested temperature range, the calculated enthalpy change (△H0) is positive (> 0), indicating that the removal progress is associated with a negative heat response [28]. Gibbs free energy (△G0) < 0, indicating that the removal progress is autogenic [21]. Entropy change (△S0) > 0 signifies that the disorder between solid and liquid is increased in the removal progress [35]. To conclude, the removal progress is an autogenous negative heat process, which is consistent with the results of Fig. 3 and Table S4.

Adsorption Selectivity

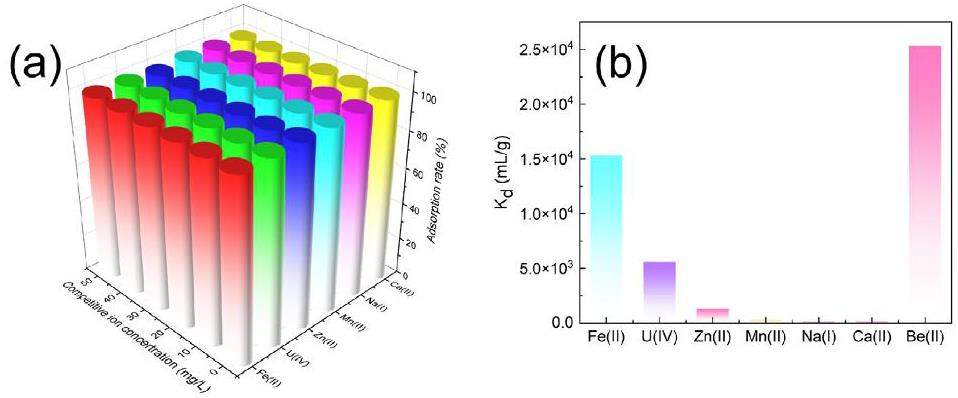

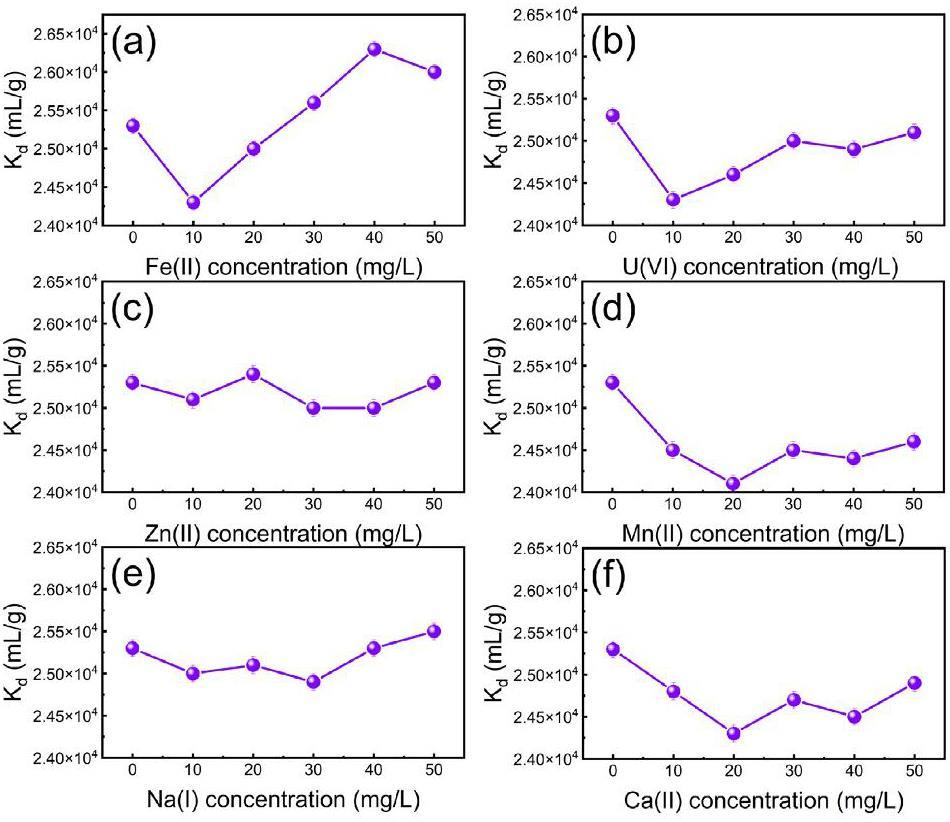

The selective adsorption experiment of beryllium by CP@Glycine was explored. In U/Be solutions, multiple coexisting ions usually compete for active sites [36]. The separation behaviors of Be(II) with CP@Glycine from the mixed solutions with Zn, Mn, Ca, Fe, Na, and U were also carefully examined. Figure 4(a) illustrates the competitive adsorption of Be(II) from binary solutions that contain Be(II) and other different metal ions. The obtained results indicate that CP@Glycine exhibits a good adsorption rate (99%) of Be(II) from mixed U/Be solutions with various ion concentrations. The defined distribution coefficient (Kd) shows the adsorption selectivity of Be(II) with CP@Glycine. Figure 4(b) demonstrates the Kd of each competitor ion at the same concentration. The Kd value of Be(II) with CP@Glycine (Kd=2.53×104 mg·L-1) is much higher than the other six elements, which confirms that CP@Glycine has excellent selectivity of Be(II) over other impurities (i.e., Zn(2) (Kd=0.133×104 mg·L-1), Mn(2) (Kd=0.023×104 mg·L-1), Ca(2) (Kd=0.014×104 mg·L-1), Fe(2) (Kd=1.53×104 mg·L-1), Na(1) (Kd=0.013×104 mg·L-1), and U(6) (Kd=0.56×104 mg·L-1)). To investigate the adsorption selectivity of Be(II) over competitive ions, the influence of different concentrations of competitive ions on Kd of Be(II) was also determined. Figure 5 illustrates the effect of various ion concentrations (i.e., Fe(2), U(6), Zn(2), Mn(2), Na(1), and Ca(2)) on the Kd value of Be(II). Figure 5(a) demonstrates that the Kd value of Be(II) grows with increasing Fe(2) concentration because increasing pH may lead to precipitation of Fe(2) and co-precipitation with Be(II) [21]. Figures 5(b-f) illustrate that within the experimental range, the concentrations of coexisting ions (i.e., Zn, Mn, Ca, Na, and U) have little influence on the Kd value of Be(II). The orders of magnitude of the Kd value of Be(II) are as high as 2.53×104 mg·L-1, indicating the strong removal selectivity of CP@Glycine for Be(II) from U/Be solutions.

Adsorption Mechanism

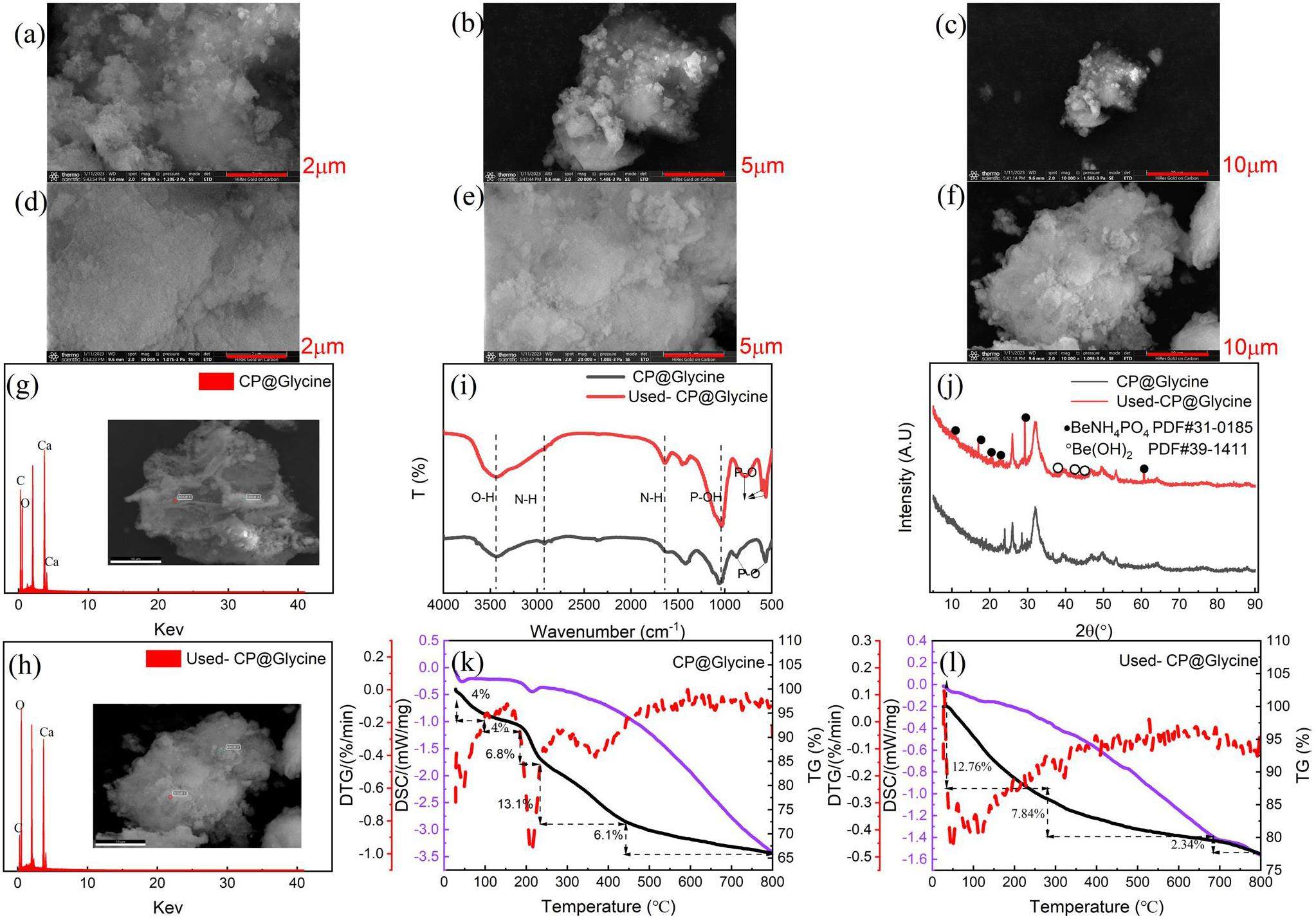

The physical and chemical properties of CP@Glycine before and after adsorption (Used-CP@Glycine) were analyzed by different characterization to discover the adsorption mechanism of Be(II) with CP@Glycine. The surface morphology of CP@Glycine and Use-CP@Glycine is presented in Figs. 6(a-f). By comparing the morphology of CP@Glycine and Use-CP@Glycine, many flocs were detected on the surface after adsorption. The energy dispersive spectrum (EDS) analysis (Fig. 6(g)) of CP@Glycine and Use-CP@Glycine was further performed. Figure 6(h) illustrates that the peaks of O element are remarkably increased, indicating that a much amount of O accumulates on Used-CP@Glycine. However, the Be element peak is not appropriately detected because Be(II) is below the EDS detection line.

The interaction between Be(II) and the adsorbent molecular groups plays a vital role in the removal process [37]. Figure 6(i) illustrates the FT-IR analysis of CP@Glycine and Use-CP@Glycine. The O-H strength of Use-CP@Glycine increased significantly. CP@Glycine has a strong vibration at 2900 cm-1 (N-H), and the vibration becomes weak after adsorption. The N-H bond shifts to 1650 cm-1, which indicates the coordination change of the N-H bond during the reaction process [31] and the formation of a new substance with Be(II). The strength of the P-OH bond enhanced after the reaction in 1060 cm-1, which reveals the increase of the -OH group radical on the CP@Glycine surface. These findings are in reasonable agreement with the EDS results. The removal band at 555 cm-1 is essentially designated as the P-O bending from the

To characterize the chemical composition of the newly formed product after adsorption, X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis (Fig. 6(j)) of CP@Glycine and Use-CP@Glycine was performed before and after adsorption. Figure 6(j) illustrates that new diffraction peaks appear in the XRD pattern of Use-CP@Glycine compared to the XRD pattern of CP@Glycine, which implies the formation of new products. According to standard diffraction card data, the diffraction peaks of the formed products correspond to BeNH4PO4 (PDF#31-0185) and Be(OH)2 (PDF#39-1411). It can then be concluded that beryllium compounds are produced during the adsorption process and the products are mostly BeNH4PO4 and Be(OH)2. This finding confirms that the separation of Be(II) is dominated by chemisorption and that both P-O bonds and N-H bonds of CP@Glycine involve the formation of BeNH4PO4 precipitates. Hence, it is thought that the central Be(II) ion formed a complex due to the presence of two distinct coordinate bonds of CP@Glycine to achieve a chelating effect.

To further confirm the composition of the surface precipitates after adsorption, thermogravimetric analysis (TG) was implemented and the corresponding results of CP@Glycine and Used-CP@Glycine are presented in Fig. 6(k-i). The plot associated with CP@Glycine exhibits multiple endothermic peaks, the first peak happens around 65 ℃ and the loss value is around 4%, which indicates the lack of water in the adsorption material [40]. The second peak occurs around 200 ℃ and the loss value was 6.8%, which was essentially related to the loss of ammonia in CP@Glycine [41]. The third endothermic peak occurs at about 400 ℃ with a loss value of 13.1%, indicating the dehydroxylation of CP@Glycine [42]. The endothermic loss peak of Used-CP@Glycine is estimated to be 12.76% at about 65 ℃-280 ℃, which indicates the loss of water and ammonia [41]. The thermogravimetric loss from 300 ℃ to 690 ℃ corresponds to the dehydroxylation process of Used-CP@Glycine with a loss of 7.84%. The third endothermic peak appears at the temperature of 700 ℃-800 ℃ and the loss rate is 2.34%, revealing the conversion process of pyrophosphate ion

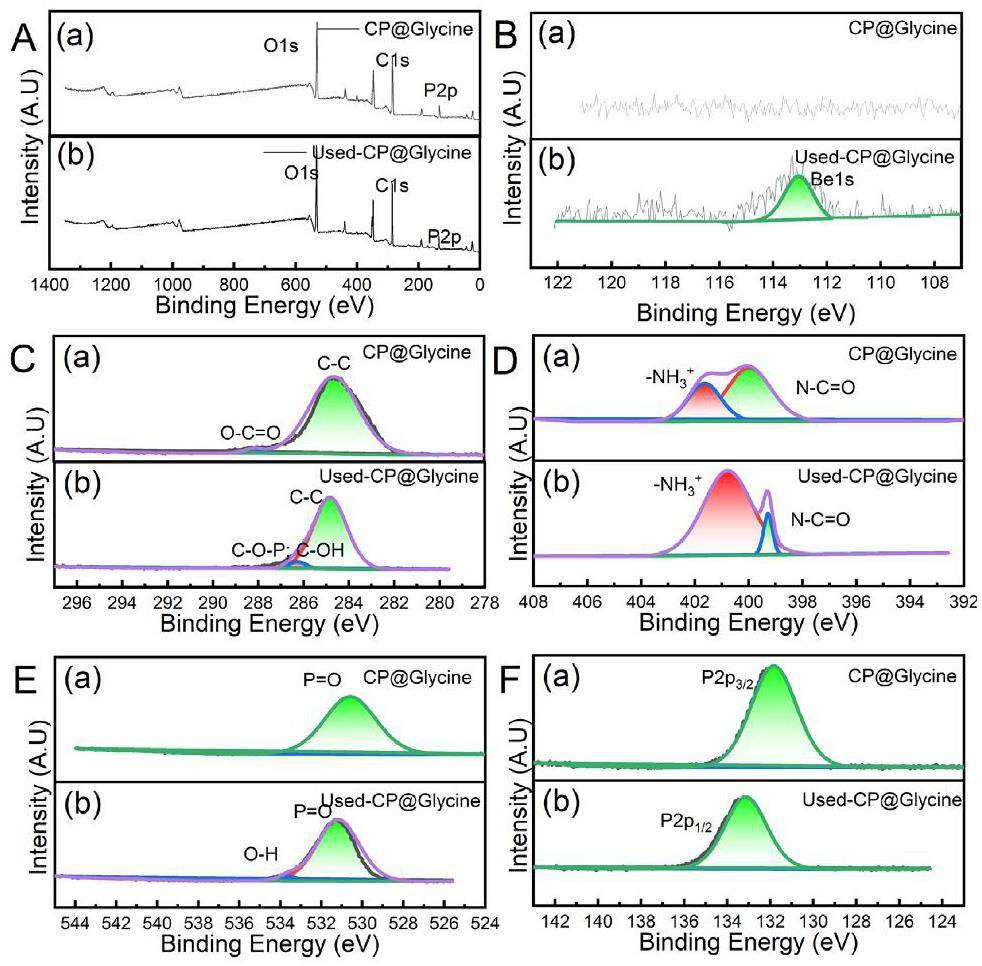

A previous study has shown that elemental valence changes occur during the adsorption process [31]. Herein, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (see Fig. 7) has been utilized to analyze the elemental valence changes of CP@Glycine and Used-CP@Glycine C 1s, O 1s, N 1s, and P 2p were further analyzed. Figure 7(A) illustrates the entire XPS spectrum of CP@Glycine and Used-CP@Glycine. According to Fig. 7(B), Be(II) is detected in Used-CP@Glycine, indicating that beryllium is adsorbed to CP@Glycine. Figure 7(C) demonstrates that the O-C=O bond is converted into a C-O-P bond and a C-OH bond during the reaction, indicating that phosphate is involved in the reaction between Be(II) and CP@Glycine [43, 44]. Compared with CP@Glycine, the area of the

Adsorption Mechanism

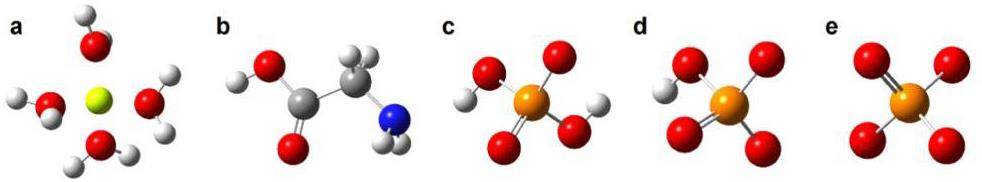

In this paper, the interaction of Be (2) with a phosphate group and glycine in CP@Glycine has been investigated utilizing the quantum chemistry calculation method. The stable existence forms of glycine,

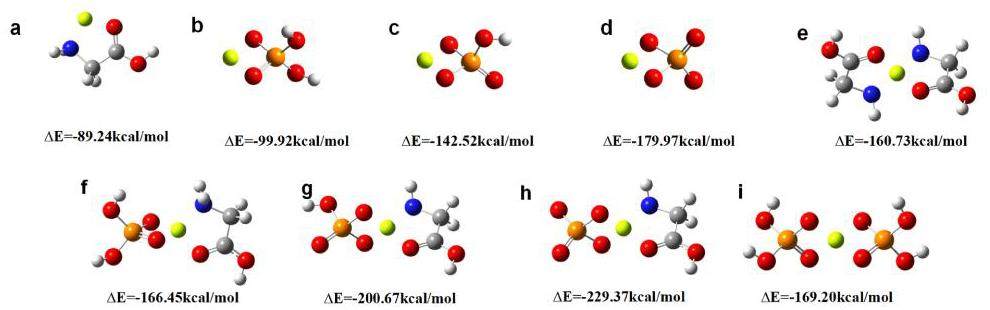

The optimized structure and binding energy of beryllium and different ligands are presented in Fig. 9.

Figure 9(a) are the optimized structures and binding energies of the possible Be(II) complexes formed with glycine. It is found that both the amino and carboxyl groups participate in the bonding with Be2+, the formed complex has the lowest binding energy -89.24 kcal·mol-1, so this binding mode is the most thermodynamically stable [47]. Figure 9(b) shows the optimized structure and binding energy of Be2+ with

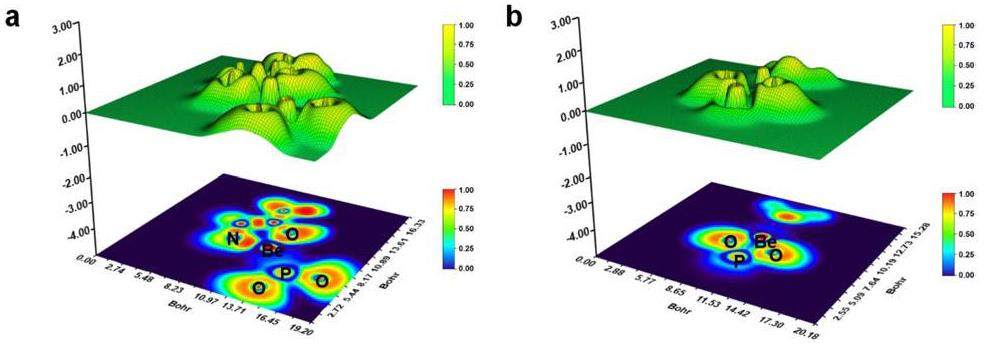

Figure 10 presents the Electron Localized Function (ELF) diagram of the electron density distribution among Be, glycine, and phosphate ligands. The cross-section of Fig. 10(a) is the plane where nitrogen/oxygen atoms and Be2+ in glycine are located, and the cross-section of Fig. 10(b) is the plane where two oxygen atoms and Be2+ directly interact with Be2+ in

According to the above characterization results, it is speculated that both the N-H bond and P-O bond of CP@Glycine form a stable metal-chelated complex with Be(II) during adsorption [18]. N, O, and P of CP@Glycine all contribute electrons to the coordination of Be2+. The hydroxyl and amino groups of CP@Glycine lead to more anions on the solid surface that produce an electrostatic attraction to positively charged beryllium ions [31]. Moreover, the O-H on the CP@Glycine combined with Be(II) to form a beryllium hydroxide precipitate [15]. In addition, amino acids have been reported to produce ammonia and phosphate due to the deamination process [47, 48]. These adducts may promote the formation of stable metal chelate complexes with Be(II). The quantum chemical calculation indicates higher stability of Gly-Be-

Conclusion

In this study, first, a chelate-like amino acid/calcium phosphate composite material was designed and synthesized for the efficient, simple, and economic separation of Be(II) from U/Be solutions. According to batch experiments, the best composition for the preparation of CP@Glycine was determined, and the ratio of

Beryllium and Copper-Beryllium Alloys

. Chembioeng. Rev. 5, 30-33 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/cben.201700016Elevated temperature compressive behavior of a beryllium-aluminum casting alloy

. Mater. Lett. 229, 89-92 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2018.06.067Surface binding energies of beryllium/tungsten alloys

. J. Nucl. Mater. 472, 76-81 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2016.02.002Challenges and opportunities of the European Critical Raw Materials Act

. Miner. Econ. 37, 661-668 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13563-023-00394-ySoil pollution of beryllium around beryllium smelting plant

. Journal of Liaoning University (Natural Science Edition) S1, 68-74 (1982).Beryllium adsorption from beryllium mining wastewater with novel porous lotus leaf biochar modified with PO43−/NH4+ multifunctional groups (MLLB)

. Biochar 6, 89 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42773-024-00385-4Elevated temperature compressive behavior of a beryllium-aluminum casting alloy

. Mater. Lett. 229, 89-92 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2018.06.067New insight in beryllium toxicity excluding exposure to U/Be dust: accumulation patterns, target organs, and elimination

. Arch. Toxicol. 93, 859-869 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00204-019-02432-7Potential targets to reduce beryllium toxicity in plants: A review

. Plant. Physiol. Bioch. 139, 691-696 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.04.022Beryllium contamination and its risk management in terrestrial and aquatic environmental settings

. Environ. Pollut. 320,Biosorption behavior and mechanism of beryllium from aqueous solution by aerobic granule

. Chem. Eng. J. 172, 783-791 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2011.06.062Biosorption of beryllium from aqueous solutions onto modified chitosan resin: Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic study

. J. Disper. Sci. Technol. 11, 1597-1605 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1080/01932691.2018.1452757Modification of activated carbon from agricultural waste lotus leaf and its adsorption mechanism of beryllium

. Korean. J. Chem. Eng. 40, 255-266 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-23415-9Adsorptive removal of beryllium by Fe-modified activated carbon prepared from lotus leaf

. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 30, 18340-18353 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-23415-9Preparation of porous calcium carbonate biochar and its beryllium adsorption performance

. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11,Adsorption of beryllium on peat and coals

. Fuel 49, 61-67 (1970). https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-2361(70)90008-6Indirect complexometric determination of beryllium

. Talanta 22, 910-911 (1975). https://doi.org/10.1016/0039-9140(75)80192-5Homogeneous precipitation of beryllium by means of trichloroacetic acid hydrolysis and determination as phosphate

. Anal. Chim. Acta. 47, 333-338 (1969). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-2670(01)95685-5Application of amino acids for gold leaching: Effective parameters and the role of amino acid structure

. J. Clean. Prod. 391,Design and syntheses of functionalized copper-based MOFs and its adsorption behavior for Pb (2)

. Chinese Chem. Lett. 33, 973-978 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2021.07.040Selective extraction of uranium from uranium–beryllium ore by acid leaching

. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Ch. 322, 597-604 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-019-06689-1Novel multifunctional of magnesium ions (Mg++) incorporated calcium phosphate nanostructures

. J. Alloy. Compd. 730, 31-35 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.09.254Efficient synthesis of amino acid polymers for protein stabilization

. Biomater. Sci-UK. 7, 3675-3682 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1039/c9bm00484jRemoval of tetracycline by NaOH-activated carbon produced from macadamia nut shells: kinetic and equilibrium studies

. Chem. Eng. J. 260, 291-299 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2014.09.017Preparation of a novel chelating resin for the removal of Ni2+ from water

. Chinese Chem. Lett. 25, 265-268 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2013.11.001Designing of hydroxyl-terminated triazine-based dendritic polymer/halloysite nanotube as an efficient nano-adsorbent for the rapid removal of Pb (2) from aqueous media

. J. Mol. Liq. 360,Enhanced performance in uranium extraction by the synergistic effect of functional groups on chitosan-based adsorbent

. Carbohyd. Polym. 300,Beryllium (2) sorption from aqueous solutions by polystyrene-based chelating polymer sorbents

. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem+. 57, 758-762 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1134/S0036023612050026Adsorptive removal of Cr (6) by Fe-modified activated carbon prepared from Trapa natans husk

. Chem. Eng. J. 162, 677-684 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2010.06.020Study on adsorption of ammonia nitrogen by iron-loaded activated carbon from low temperature wastewater

. Chemosphere 262,An eco-friendly porous hydrogel adsorbent based on dextran/phosphate/amino for efficient removal of Be (2) from aqueous solution

. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 269,Protein-mediated precipitation of calcium carbonate

. Materials 9, 944 (2016). https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9110944Adsorption of aqueous Cu (2) and Ag (1) by silica anchored Schiff base decorated polyamidoamine dendrimers: Behavior and mechanism

. Chinese Chem. Lett. 33, 2721-2725 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2021.08.126Adsorption isotherm and thermodynamic studies of As (3) removal from aqueous solutions using used cigarette filter ash

. Appl. Water Sci. 9, 172 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13201-019-1059-9Application of corn stover derived pyrolyzed hydrochars for efficient phosphorus removal from water: Influence of pyrolysis temperature

. Chem. Eng. J. Adv. 18,Rational synthesis of novel phosphorylated chitosan- carboxymethyl cellulose composite for highly effective decontamination of U(6)

. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 7, 5393-5403 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.04.103Electrosorption of uranium (6) by highly porous phosphate-functionalized graphene hydrogel

. Appl. Surf. Sci. 484, 83-96 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.04.103Synthesis of phosphorylated hyper-cross-linked polymers and their efficient uranium adsorption in water

. J. Hazard. Mater. 419,Selective, rapid extraction of uranium from aqueous solution by porous chitosan-phosphorylated chitosan-amidoxime macroporous resin composite and differential charge calculation

. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 253,Simple recycling of biowaste eggshells to various calcium phosphates for specific industries

. Sci. Rep-UK. 11, 15143 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94643-1TG/DTA and XRD study on structure and chemical transformation of the Cs–P–W oxides

. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 128, 947-956 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-016-5990-9Characterization of β-tricalcium phosphate-clay mineral composite obtained by sintering powder of apatitic calcium phosphate and montmorillonite

. Surf. Interfaces, 17,Interaction mechanism of uranium(6) with three-dimensional graphene oxide-chitosan composite: Insights from batch experiments, IR, XPS, and EXAFS spectroscopy

. Chem. Eng. J. 328, 1066-1074 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2017.07.067Adsorption performance and mechanism of Schiff base functionalized polyamidoamine dendrimer/silica for aqueous Mn (2) and Co (2)

. Chinese Chem. Lett. 31, 2742-2746 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2020.04.036Synthesis of ultralight phosphorylated carbon aerogel for efficient removal of U(6): Batch and fixed-bed column studies

. Chem. Eng. J. 370, 1376-1387 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2019.04.012Synthesis of α-aminophosphonate functionalized chitosan sorbents: Effect of methyl vs phenyl group on uranium sorption

. Chem. Eng. J. 525, 1022-1034 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2018.06.003Quickstart guide to model structures and interactions of artificial molecular muscleswith efficient computational methods

. Chem. Commun. 58, 258-261 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1039/D1CC05759FThe decomposition of N-chloro amino acids of essential branched-chain amino acids: Kinetics and mechanism

. J. Hazard. Mater. 382,The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-025-01747-8.