Introduction

Beamline BL17B at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) [1], which is affiliated with the National Facility for Protein Science in Shanghai (NFPS) (https://www.ncpss.org.cn/index.action), was originally conceived to conduct high-throughput protein crystallography [2-4] investigations. Beamline BL17B supports techniques such as single-crystal diffraction [5-6], powder diffraction [7], and grazing-incidence wide-angle X-ray scattering (GIWAXS) [8-10] to enable the characterization of long-range ordered atomic structures. Beyond its applications in structural biology [11-13], this beamline supports scientific research across diverse domains, including the environment [14-15], energy [16-17], and materials [18-20]. In these fields, investigators frequently require an understanding of the structural order at a scale of a few angstroms, namely, the short-range order. Although traditional crystallographic techniques reveal long-range ordered crystal structures, they may not adequately capture the local amorphous nature of such short-range ordered features. For instance, research on transition metal-containing biological systems necessitates local structural insights into metal sites related to functional diversity [21-22]. In biomedical and ecological environmental research, understanding the local coordination of exogenous metals within biomacromolecules and their transformation processes are essential in the revelation of their interaction mechanisms [14, 23, 24]. Similarly, studying the catalytic processes and mechanisms of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), covalent-organic frameworks (COFs), and their derivatives in materials research requires knowledge of the active sites along with the local atomic coordination and chemical state [25, 26]. Research on perovskite solar cells also benefits from short-range ordered structural characterization to assess the impacts of nanoscale phase impurities on the film quality [27].

X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) [28, 29] techniques can be used to probe local atomic and electronic environments within ranges of approximately 0.5 to 5 Å surrounding the element-specific absorbing centers in short-range ordered structures. Moreover, XANES, the near-edge region of XAFS, reveals details regarding oxidation states, electron orbital occupation, and coordination symmetries. In EXAFS, the extended XAFS oscillations provide information on the atomic distances, coordination numbers, and species of neighboring atoms. The XAFS technique effectively compensates for the limitations of crystallography in characterizing short-range order structures and offers the advantage of being adaptable to various sample forms. That is, XAFS is not limited to crystal structures alone. Beamline BL17B possesses the optical foundation and spatial conditions required to develop an XAFS experimental technique. Thus, we constructed a novel XAFS platform at BL17B to extend our structural characterization capabilities from long-to short-range orders. This study provides a valuable reference for similar upgrade projects in synchrotron facilities.

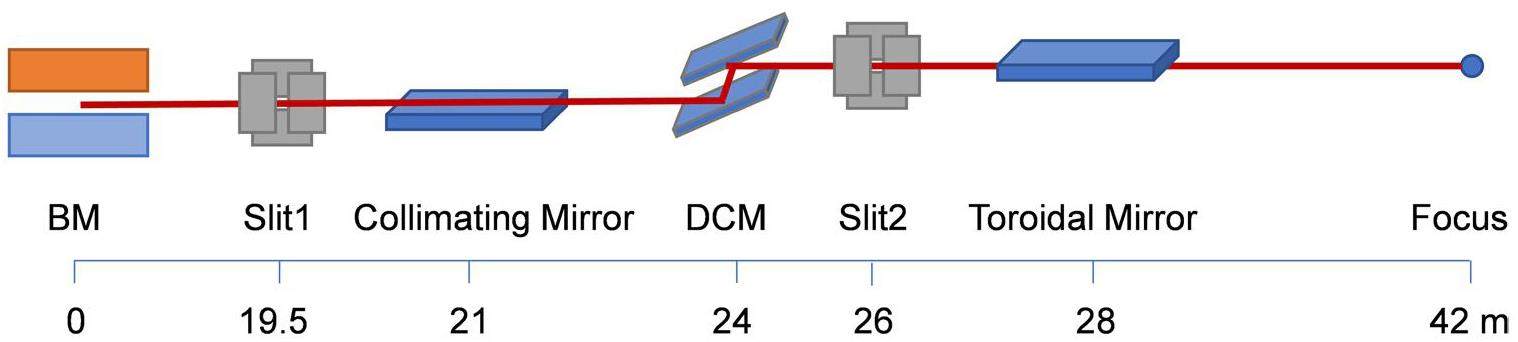

Basis for upgrade

The existing optical configuration of BL17B is primarily designed to accommodate the requirements of single-crystal diffraction experiments. A schematic of the main optical components of BL17B is shown in Fig. 1. The SSRF was operated at an electron energy of 3.5 GeV with a current of 220 mA in top-up mode. The X-ray photon source was a bending magnet with a magnetic field of 1.27 T, and it generated a white beam with a critical energy of 10.3 keV. The beam was confined through a 1.5 mrad × 0.1 mrad (H×V)-wide white-beam slit, namely, Slit1, which selected the central cone to alleviate the radiation and thermal loads on downstream optics. The beam was subsequently collimated vertically into a quasi-parallel beam to improve the energy resolution. The collimating mirror is set at a grazing incidence angle of 2.8 mrad and features 2 reflection stripes, namely, a Si coating used below 8 keV and a Rh coating used at 8-23 keV. This system suppressed the harmonic contamination relative to the fundamental to be below 10-3. A fixed-exit Si(111) double-crystal monochromator (DCM) then converted the white beam into a monochromatic beam with an energy resolution of 2×10-4 within the 5–23 keV range. Slit2 further refined the beam to decrease its size. Finally, the monochromatic X-rays were focused using a Rh-coated toroidal mirror at a grazing incidence angle of 2.8 mrad. The focal point, which was 42 m from the source, served as the diffractometer sample position with a beam size of 150 µm × 180 µm (H×V) and divergence of 1.5 mrad × 0.2 mrad (H×V) to provide a flux of 2 × 1011 photons/s at 12 keV.

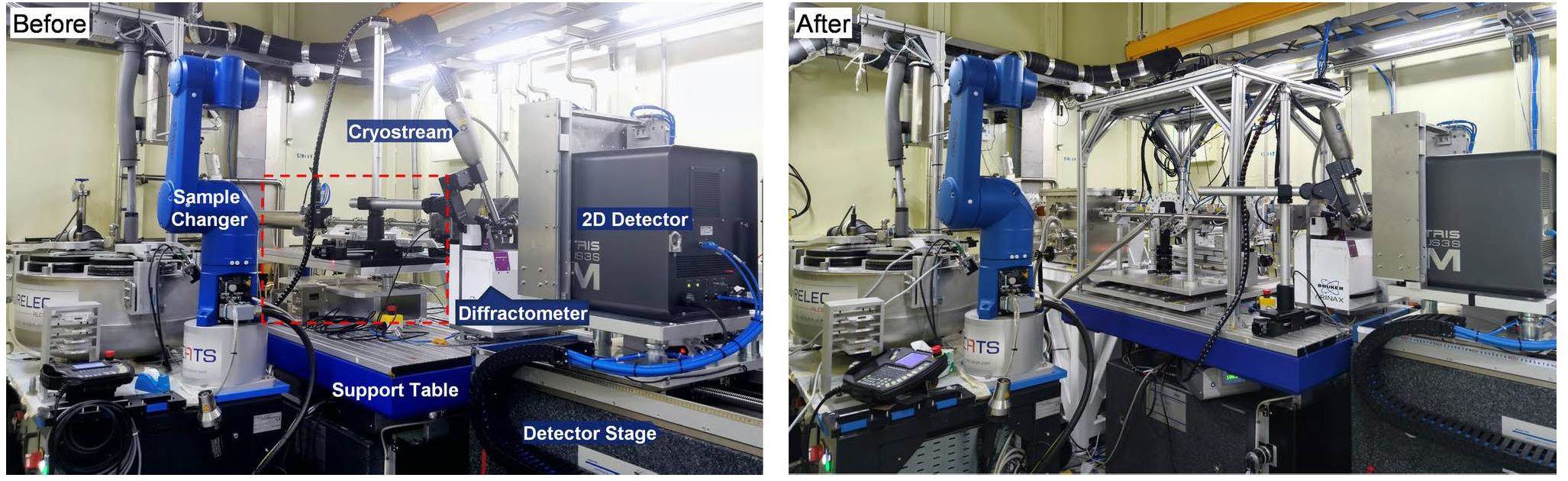

Considering the feasibility of incorporating XAFS experiments at BL17B, the current monochromatic beam energy range, energy resolution, and flux meet the requirements for the XAFS experiment. However, further suppression of harmonic content is required. For XAFS, the acceptable level of harmonic contamination relative to the fundamental signal is generally below 10-4 [30], as harmonics can lead to amplitude attenuation in the XAFS spectra owing to the effect of undesirable photons [31, 32]. Currently, only energies greater than 10 keV satisfy this criterion. By introducing dedicated harmonic rejection mirrors, the 5–10 keV region can also be rendered compatible. In terms of experimental space, an approximately 2 m segment that is primarily occupied by vacuum pipes exists between the Be window exit and diffractometer in the experimental hutch (highlighted in the red box in the left panel of Fig. 2). This space can accommodate an XAFS station with the XAFS sample positioned approximately 1 m upstream of the diffraction sample. Adjusting the grazing incidence angle and height of the toroidal mirror focuses the XAFS sample position. By mounting both the XAFS setup and a vacuum tube for the diffraction experiment on a platform that can move perpendicularly to the optical path, rapidly switching between XAFS and diffraction modes becomes convenient. The image on the right in Fig. 2 shows the experimental hutch after incorporating the XAFS station according to the proposed scheme.

XAFS experimental station

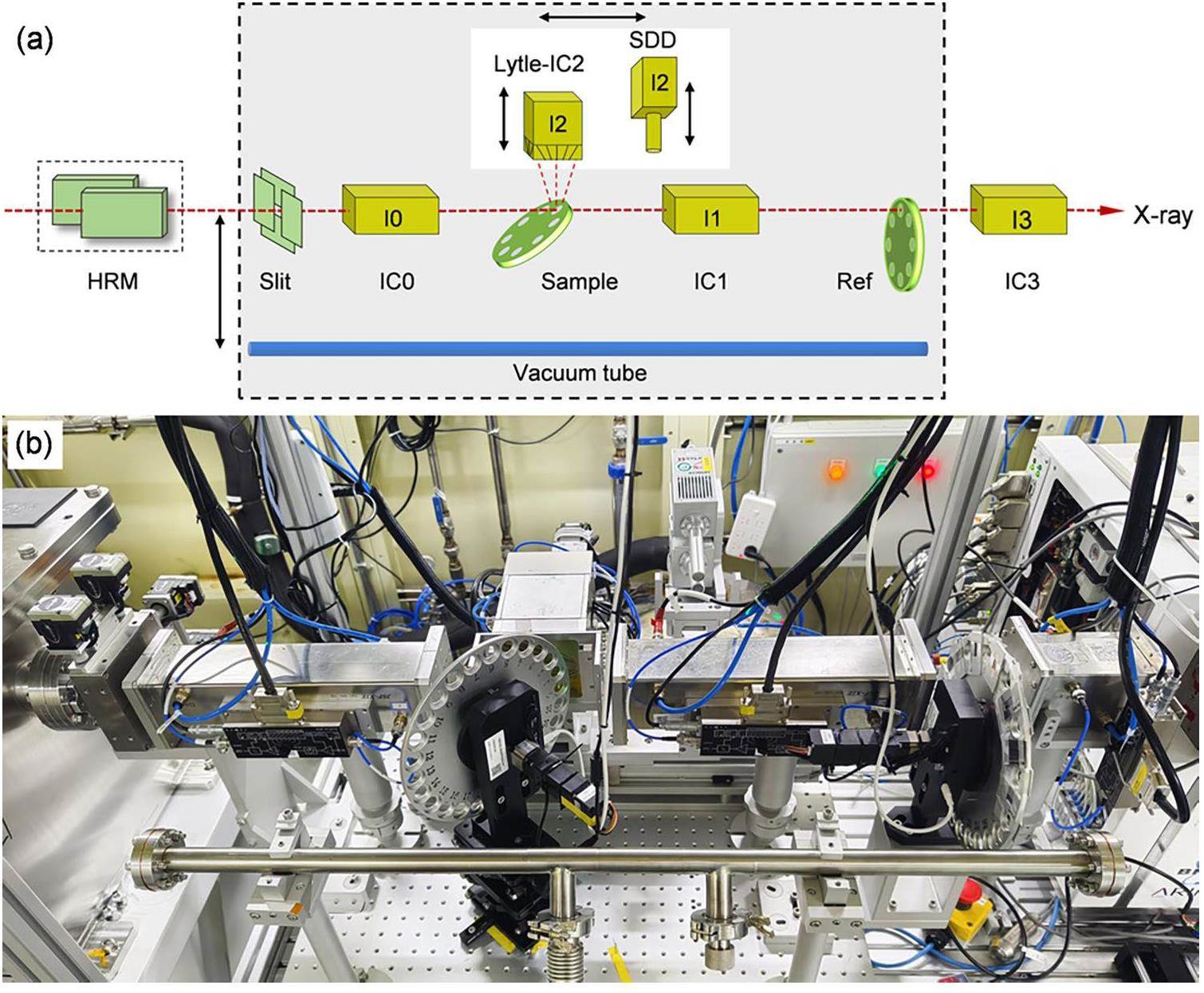

We added an XAFS experimental station in the beam path upstream of the diffraction experiment station. As depicted in Fig. 3, the XAFS experimental station consisted of two main parts: (1) a standalone harmonic rejection mirror (HRM) installed on the floor and (2) an XAFS testing platform installed on the existing support stage equipped with a slit, XAFS sample holder, detector, and vacuum tube. A slit was used to shape the incident beam and restrict the scattered photons around the central cone. When the vacuum tube was moved in, it switched to the diffraction mode, and the I3 ionization chamber remained in the beam path to monitor the incident beam intensity.

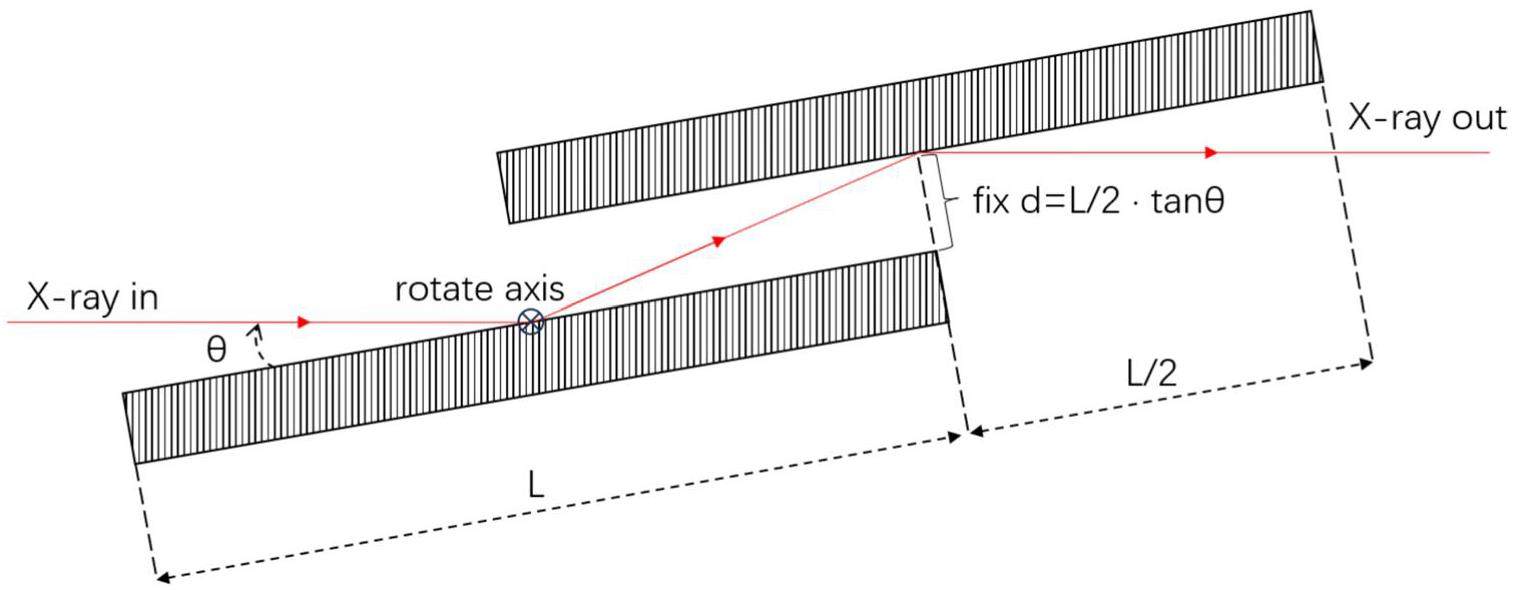

Harmonic rejection mirror (HRM)

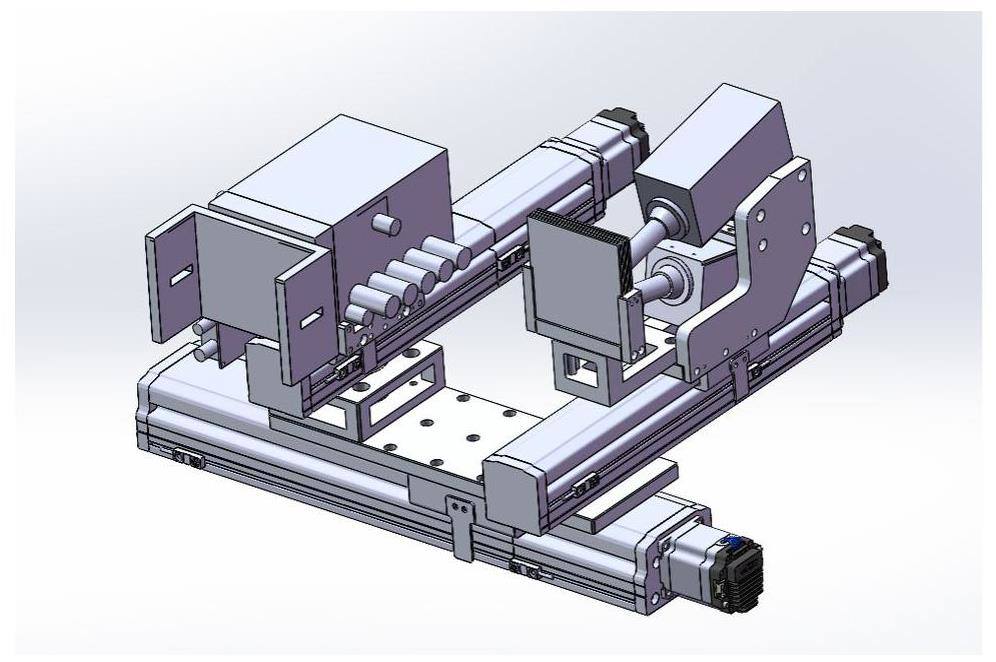

The reflectivity of materials for grazing incidence X-rays is nearly 100% below the critical energy but drops sharply above the critical energy [33]. Therefore, a grazing incidence plane mirror can be considered a low-pass filter for X-rays used to suppress higher-order harmonics. Based on this principle, the HRM employs a pair of pre-aligned and parallel-plane mirror designs, as shown in Fig. 4. The plane mirror had 200 mm long Ni and Rh stripes on the Si substrate, and the grazing angle was fixed at 5.8 mrad. The mirrors were placed in parallel with a 100 mm offset and were separated vertically by 0.58 mm. This design further suppressed harmonics at energies above 5 keV to ensure that the XAFS amplitude attenuation caused by harmonics was less than 1%. The HRM was positioned 40.2 m downstream of the source and could fully receive the main beam. These settings reflected the fundamental flux with efficiencies of 88% and 65% for the Ni and Rh coatings, respectively. The HRM design ensured the suppression of high-order harmonics without excessively affecting the beam size and light flux downstream. The Ni coating worked from 5–8 keV, whereas the Rh coating worked from 5.5–11 keV. In the overlapping zone (5.5–8 keV), both coatings were viable, providing ample redundancy. However, the Ni coating offered higher reflectivity, making it the preferred choice. At energies greater than 10 keV, the mirrors were moved out of the beam path. The beam height change between using and not using the mirrors was 1.16 mm, which could be accommodated by lifting the downstream support stage. The HRM box served as a support base and provided vacuum protection for the mirrors to enable the control of the incident angle and coating switching.

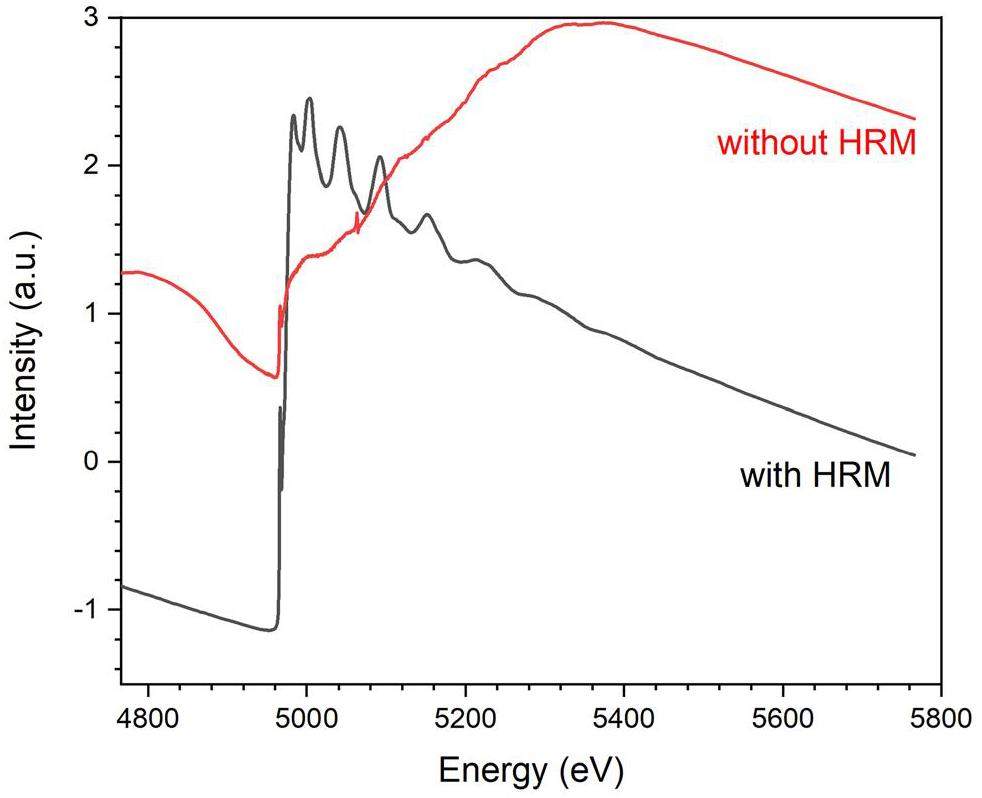

The effectiveness of the HRM in the XAFS experiments was validated through K-edge XAFS testing on a Ti foil, as shown in Fig. 5. The total absorption length of the Ti foil at 5 keV was 3.8. Given that the harmonic content was higher in lower-energy regions, an increased sample thickness exacerbated the amplitude attenuation effect. The spectral shape was severely distorted in the absence of HRM but returned to its normal state upon the inclusion of HRM. These results clearly demonstrate the effectiveness of HRM in suppressing harmonics and the necessity of acquiring reliable XAFS data.

Testing platform

As shown in Fig. 3, three ionization chambers were arranged along the X-ray path, with the sample wheel and reference sample wheel positioned between them. The I0 ionization chamber monitors the incident beam intensity, I1 records the beam intensity transmitted through the sample, and I3 records the beam intensity transmitted through the reference sample. Because synchrotron X-rays are linearly polarized in the horizontal plane of the synchrotron[34], the scattering interference is weakest in the direction perpendicular to the beam path within the horizontal polarization plane. Therefore, fluorescence detector I2 was placed along the perpendicular direction to collect the fluorescence of the sample. By simultaneously collecting the I0, I1, I2, and I3 signals, we obtained the following: a) the transmission-mode XAFS of the sample using Eq. (1), (b) the fluorescence-mode XAFS of the sample using Eq. (2), and (c) the transmission-mode XAFS of the reference sample using Eq. (3):

There are two types of fluorescence detectors: a Lytle ionization chamber and an SDD. The Lytle detector has the advantage of handling higher-count-rate signals, and it is simple to operate with low maintenance costs. The SDD detector distinguishes XRF signals from different elements, which is particularly useful for studying multi-element materials. The fluorescence detectors are mounted on a two-level electric stage for rapid switching, as shown in Fig. 6. Both detectors have an upper stage to adjust the distance between the detector and sample along the perpendicular direction. The detectors and their upper stages shared a common lower stage for movement parallel to the beam path. The motor positions for different detectors under operation or standby states were predefined, which allowed for one-click rapid switching between the fluorescence detectors.

Experiment mode

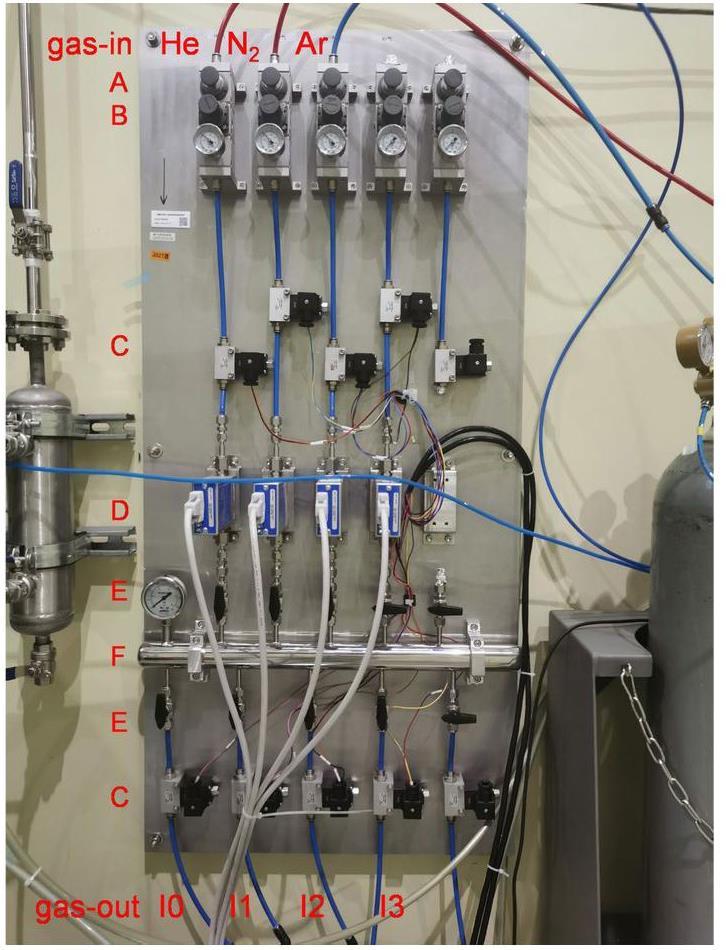

(i) Transmission mode. I0, I1, and I3 are fixed-length ISIC series standard gas ionization chambers from the Tianjin Jingshenfang company with effective lengths of 30 cm for I0 and I1 and 10 cm for I3. The He/N2/Ar gas mixture ratios of each ionization chamber were predefined for every absorption edge to maintain absorption ratios of approximately 20% for I0, 80% for I1, and 100% for I3 and were executed through an automatic gas delivery system (as shown in Fig. 7). This ratio allows the transmission data of the sample to approach the optimal signal-to-noise ratio while preserving a sufficient number of transmitted photons for the reference sample to achieve good data quality. The transmission mode is applicable for samples with higher concentrations and generally requires an effective absorption concentration µA/µT greater than 10–20 µ%.

(ii) Lytle fluorescence mode. A Lytle ionization chamber [35] with 100% Ar working gas was employed. The Lytle chamber has no energy discrimination capability and cannot distinguish target fluorescence signals from other fluorescent and scattered photon backgrounds through energy identification. However, the Lytle detector employs a combination of a Z-1 filter and Soller slit [36-38] that effectively suppress background noise while preserving the target fluorescence to thereby enhance the signal-to-noise ratio. Because the fluorescent and scattered photons have different energies, the Z-1 filter can remove most of the scattered photons while preserving most of the fluorescence. The Soller slit, focused on the sample, blocks secondary photons produced by the filter while allowing the majority of the fluorescence of the sample to pass through. The Lytle detector offers a wide acceptance angle for fluorescence signals, reaching up to 10% × 4π, and has no saturation current limit, thus enabling the detection of high-intensity signals. Fluorescence-mode data are susceptible to self-absorption effects that can lead to XAFS amplitude attenuation. To mitigate the impact of self-absorption, this experiment mode is generally employed for either low-concentration thick samples, in which the effective absorption concentration is recommended below 10 µ% and the total absorption thickness µTd exceeds 3, or high-concentration thin samples, in which the edge-jump ΔµAd is less than 0.1.

(iii) SDD fluorescence mode. Fluorescence signals were collected using a 3-element Vortex-90EX [39] silicon drift detector (SDD) and processed using an Xspress 3 Mini (X3M) electronics readout system. This detector boasts energy discrimination capability and enables the selective extraction of the target fluorescence signal, which thereby enhances the signal-to-noise ratio. However, each probe has a saturation count rate of approximately 2 Mcps, which imposes an upper limit on the signal-to-noise ratio. To increase the proportion of the target fluorescence signals within the saturation count range, filters must be incorporated in front of the SDD to attenuate a significant number of scattered photons. This experimental mode primarily serves as a complement to the Lytle fluorescence mode and is typically applied when sample concentrations are lower than the detection limit of the Lytle method or when there is substantial background fluorescence interference. In such cases, the target signal is submerged in the background noise, which renders the Lytle detector ineffective, whereas the energy discrimination capability of the SDD is advantageous.

Sample loading condition

The reference sample wheel was equipped with a complete set of reference metal foils [40] from the Exafs Materials Company, allowing remote switching of the desired samples. There was ample space at the sample position to accommodate remote sample loading with the sample wheel as well as manual sample loading with an in situ sample holder or other sample holder. The sample wheel assumed that all samples are centered at each hole. That is, as long as one hole was aligned, the other holes were also aligned. Thus, the sample wheel was suitable for uniformly prepared large samples and thereby facilitated rapid sample exchange. The sample wheel had 26 holes, each with a diameter of 15 mm and spacing of 25 mm. The samples were attached to the center of the holes for loading. Because Hole #0 was used as a blank, the maximum sample capacity was 25. The wheel was attached to the base using magnets, enabling rapid wheel replacement. The position reset function of the sample wheel eliminated position errors caused by stress during wheel replacement. In particular, when a fixed pointer on the wheel passed the photoelectric sensor at the base, the current position was defined as zero. The sample wheel was generally placed at an angle of 45 °relative to the beam path to accommodate the simultaneous collection of transmission and fluorescence data.

XAFS control system

The software control system for the XAFS experiments was developed using LabVIEW, which is a system design platform, and a development environment created by National Instruments (NI), which is also known as the Laboratory Virtual Instrument Engineering Workbench. The advantages of LabVIEW are its user-friendly graphical user interface and easy-to-control modules, which are adaptable to various types of hardware. The SDD electronics readout system, along with the motion control systems of existing beamline equipment, including monochromators, focusing mirrors, and support stands, were developed based on distributed experimental physics and industrial control systems (EPICS). The communication mode of LabVIEW facilitates seamless data sharing with the EPICS system. Newly incorporated devices, such as the HRM, fluorescence detector stage, automatic gas delivery system, sample wheel, ADC, and remote gain controller communicate via Ethernet and connect to the local network through switches, interacting with the XAFS software computer.

Experiment preparation

The XAFS software is distinguished by its highly integrated architecture. This software comprehensively manages the various equipment configurations that are involved in the XAFS experiments, which thereby enhances efficiency and convenience throughout the experimental process. At the start and end of each XAFS experimental run, the software enabled effortless switching between diffraction and XAFS modes. This software can a) control the focusing mirror to adjust the focus position, b) sequentially control the HRM coating and height of the support stage for an unobstructed optical path, c) move the testing platform to switch between the vacuum tube and XAFS devices, and d) manage the automatic gas filling system, thus filling the I3 ionization chamber with 100% N2 during the diffraction mode to minimize light attenuation.

Before the formal XAFS data acquisition for each element to be measured, this software has designed the following preparation workflow: 1) mount the sample using a sample wheel or other sample holder and replace filters for fluorescence detectors; 2) change the gas for ionization chambers through the gas delivery system; 3) optimize the optical configuration, which involves adjusting the HRM working coating, controlling the support stage to compensate for beam height change after HRM, and optimizing the parallelism of the monochromator for maximum photon flux; 4) replace the reference sample via the reference sample wheel and collect its XANES data to calibrate the monochromator energy; and 5) select the appropriate fluorescence detector by controlling the two-level electric stage. Except for the first step, which requires on-site manual operation, all other steps integrate the basic subtasks into a one-touch control to accomplish the desired task. This highly integrated control system significantly reduces the need for onsite fine-tuning equipment, thus enabling remote experimentation.

Data acquisition

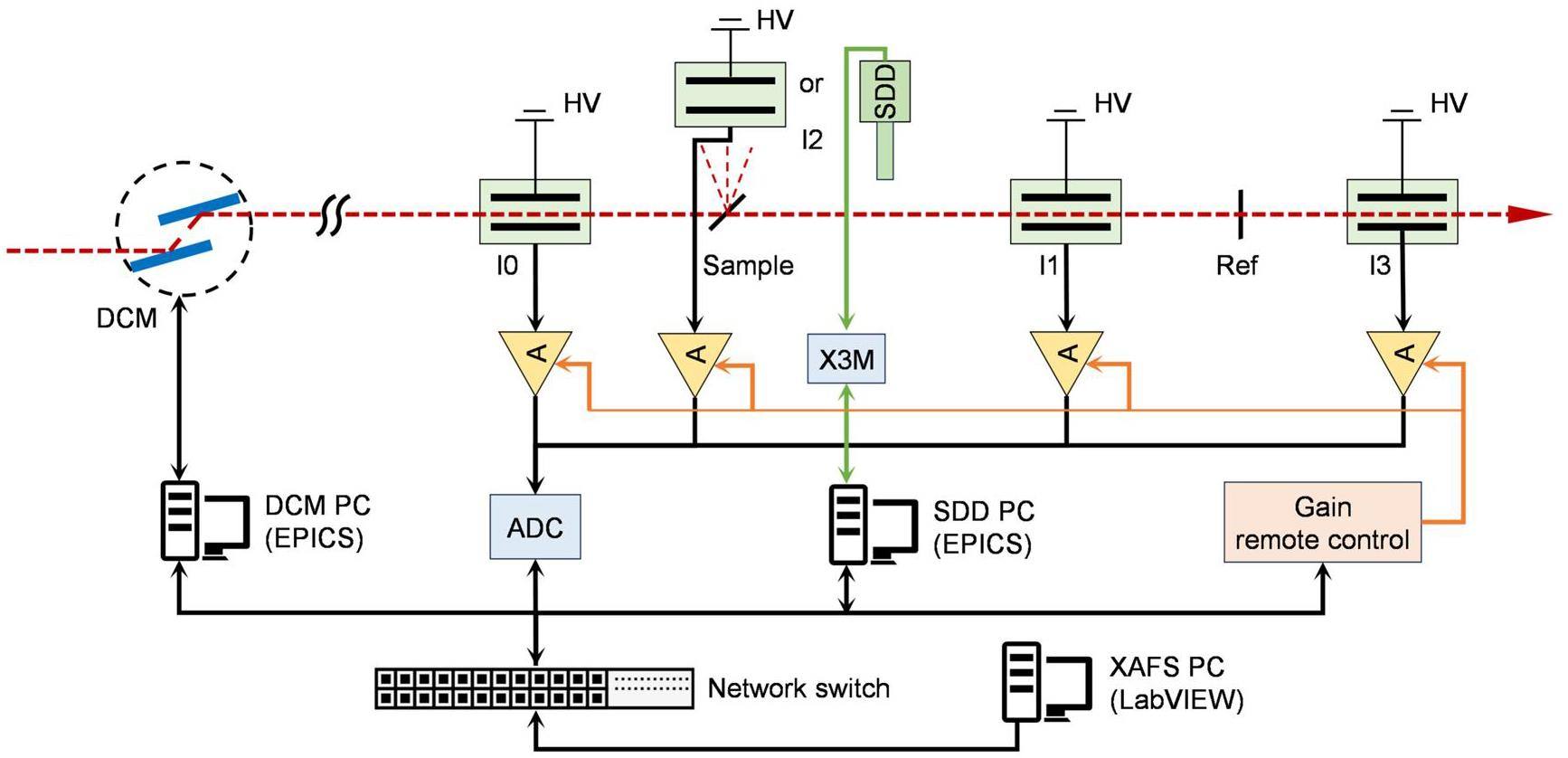

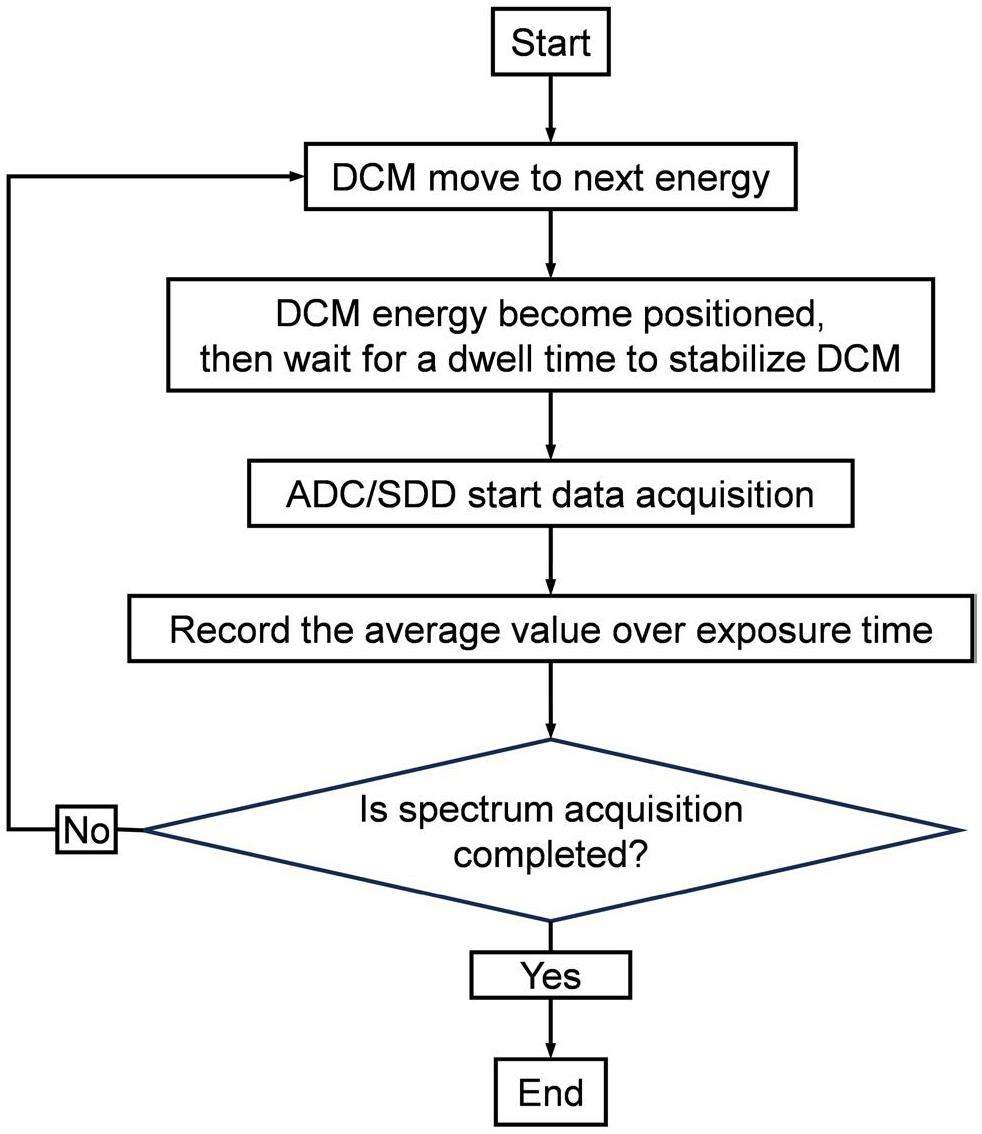

The hardware architecture involved in XAFS data collection is shown in Fig. 8. The monochromatized beam passed through the ionization chambers and samples, with attenuated photons and excited fluorescence detected and fed into the data acquisition system. The initial signal currents from the I0, I1, and I3 ionization chambers as well as the I2 Lytle detector were in the fA–uA range. Being cautious regarding the output voltage stability of the high-voltage supply for ionization chambers is crucial, as this could impact the background noise. We utilized the HV-3000 model from the Tianjin Jingshenfang Company with an output voltage ripple coefficient of less than 0.001%. Direct long-range transmission and the reading of initial signals are susceptible to transmission losses and electromagnetic interference, which introduce significant noise. To improve the signal-to-noise ratio of the subsequent electronics, current signals from each ionization chamber were connected to a current-to-voltage amplifier (Femto DLPCA-200), and the amplified voltage signals were then fed to a 4-channel ADC acquisition card (Geekootech FS3326S) and converted to digital signals. The ADC card has a 16-bit resolution and maximum sampling rate of 2 MS/s per channel. However, a 0.5 MS/s rate is used to avoid buffer overflow issues. A 4-channel remote gain controller was developed for the amplifier DLPCA-200 to enable the remote control of the gain for the four ion chambers. The initial current signal from the I2 SDD fluorescence detector was converted into a digital signal by a readout system (Quantum Detectors Xspress 3 Mini) and read using an acquisition program.

The XAFS data acquisition system employed a conventional step-by-step scan mode, as shown in Fig. 9. Here, the monochromator was driven to a specific energy and allowed to stabilize for a moment. Subsequently, the real-time energy readback was recorded. In this step, we did not repeatedly drive the monochromator to fine-tune its readback to the exact energy specification, as this could introduce worse energy errors owing to backlash. The strategy of driving the monochromator alone and recording the energy readback value effectively improves the accuracy of energy measurements while conserving time. The ADC and SDD commenced data acquisition and transmitted the data to the XAFS computer. The acquisition software calculated and recorded the average count rate within the integration time, thereby completing the collection of that data point. This process was repeated for the next energy point (cycling) until the spectrum was fully acquired. Collecting a full XAFS spectrum typically required approximately 20 min (integration time of 1 s). Moreover, to prevent signal saturation, which can lead to data distortion, we introduced an innovative auto-gain control function prior to formal data collection. This function performed a preliminary scan of the entire spectrum, identified the maximum current value for each detector, and automatically adjusted the gain of the corresponding amplifier to ensure that the amplified voltage was as large as possible without saturation. This function can provide a linear response and an optimal signal-to-noise ratio across various signal intensities, which guarantees the accuracy and reliability of the data.

The highly integrated XAFS control system enables simple data acquisition and automated measurements based on the sample wheel. A sample evaluation feature was incorporated to enhance the efficiency of the automatic measurement. By collecting data before and after the absorption edge in both the blank (Hole #0) and sample-mounted states, parameters including the total absorption thickness, effective absorption concentration, transmission edge jump, and fluorescence edge jump-to-background ratio can be calculated. These parameters assist users in rapidly assessing whether data are worth collecting and optimizing sample preparation. The selected samples were subjected to automated sample exchange and data acquisition. Notably, automatic measurement is applicable only to samples with the same absorption edge using the Lytle detector because manual filter replacement is required for different elements. Moreover, samples that require SDD detection often involve more complex situations, which makes them more suitable for individual treatment.

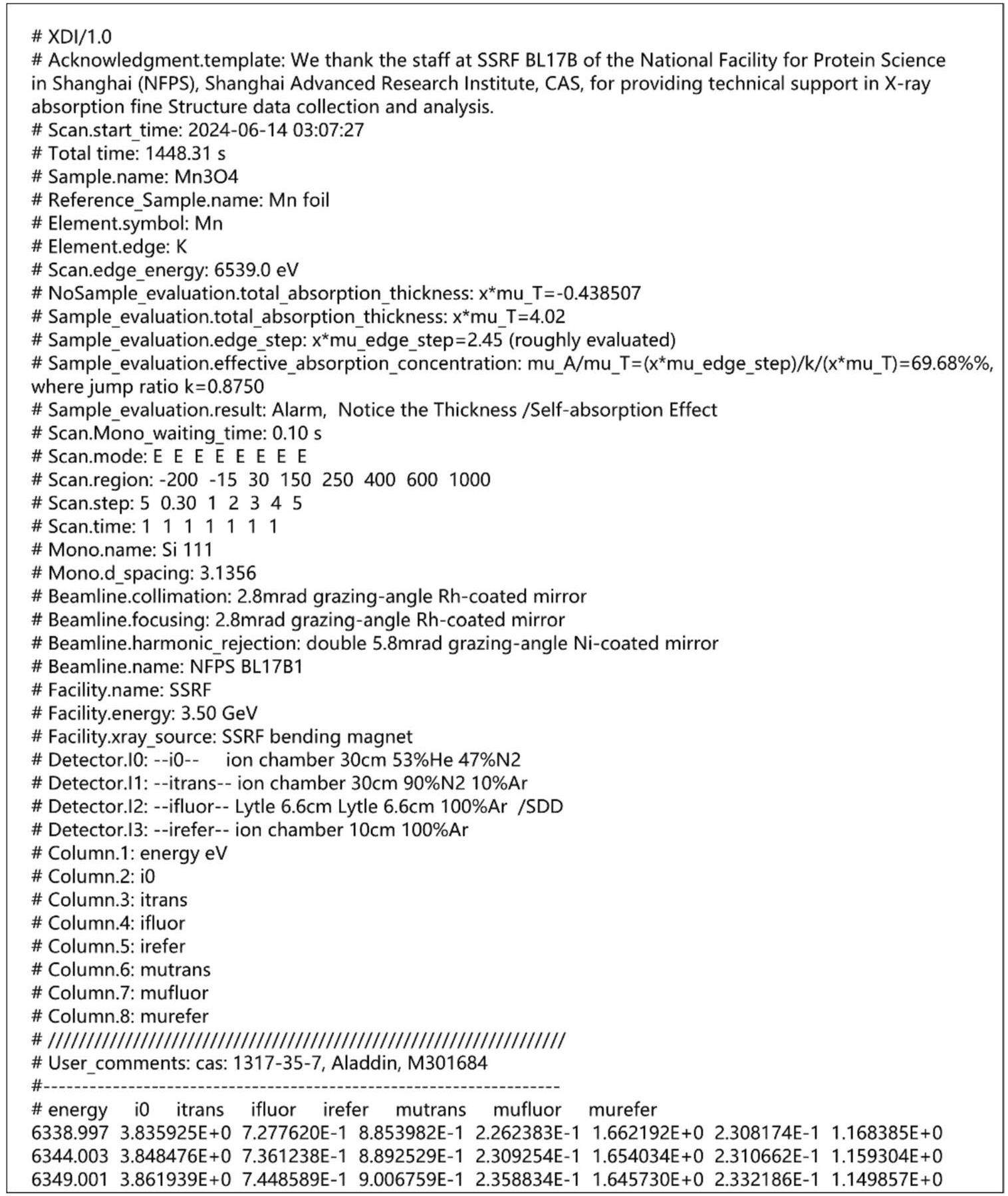

Data format

The data adopted the XAFS Data Interchange (XDI) standard[41] format specified by the International X-ray Absorption Society (IXAS). The XDI format aims to share XAFS data across continents, decades, and analysis toolkits, and it is the only accepted data format for the X-ray Absorption Data Library (XASLIB, https://www.xaslib.xrayabsorption.org). As depicted in Fig. 10, our data consist of two parts: a metadata header and data table, separated by “#----”. Our header includes details, such as the data source, absorbing element, sample evaluation, experimental setup, and user comments, which provide a comprehensive record of the experiment. The data columns correspond to the energy; raw data of I0, I1, I2, and I3; and converted absorption data of the transmission, fluorescence, and reference.

XAFS platform performance

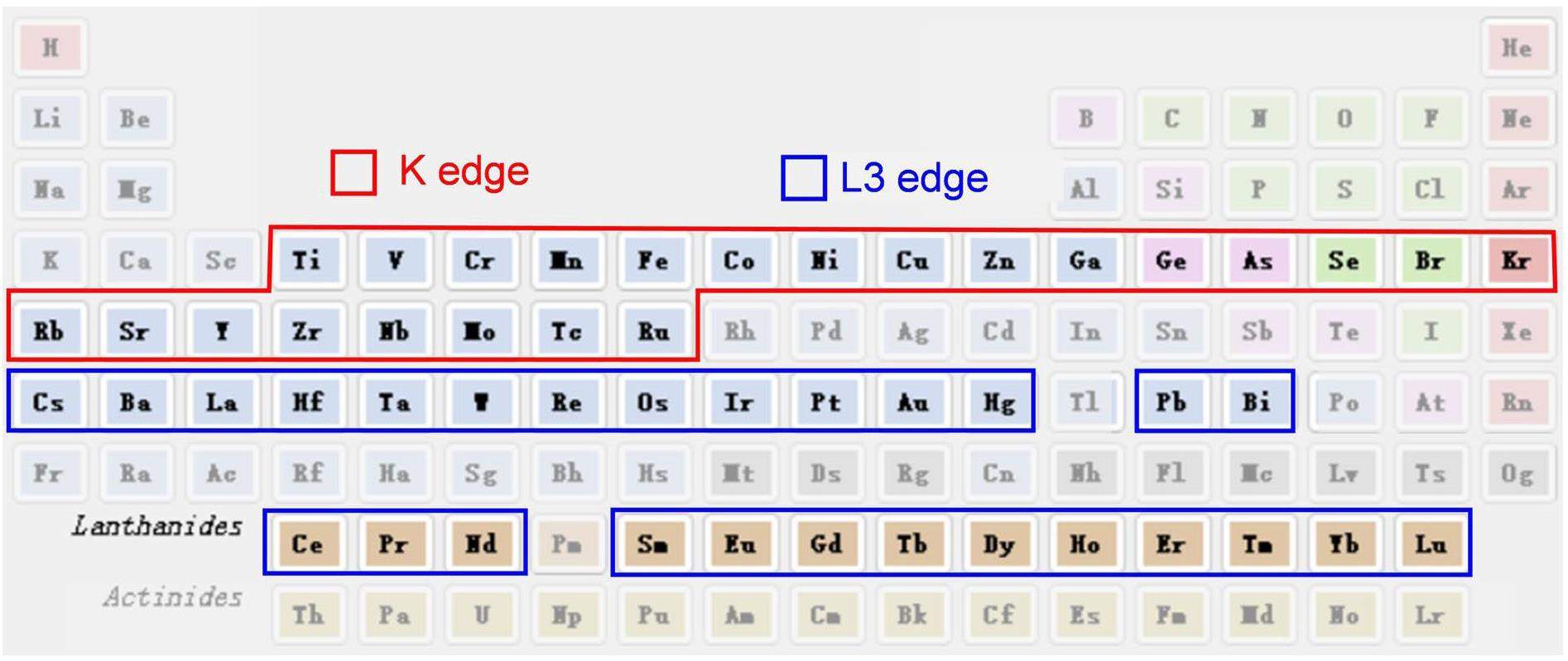

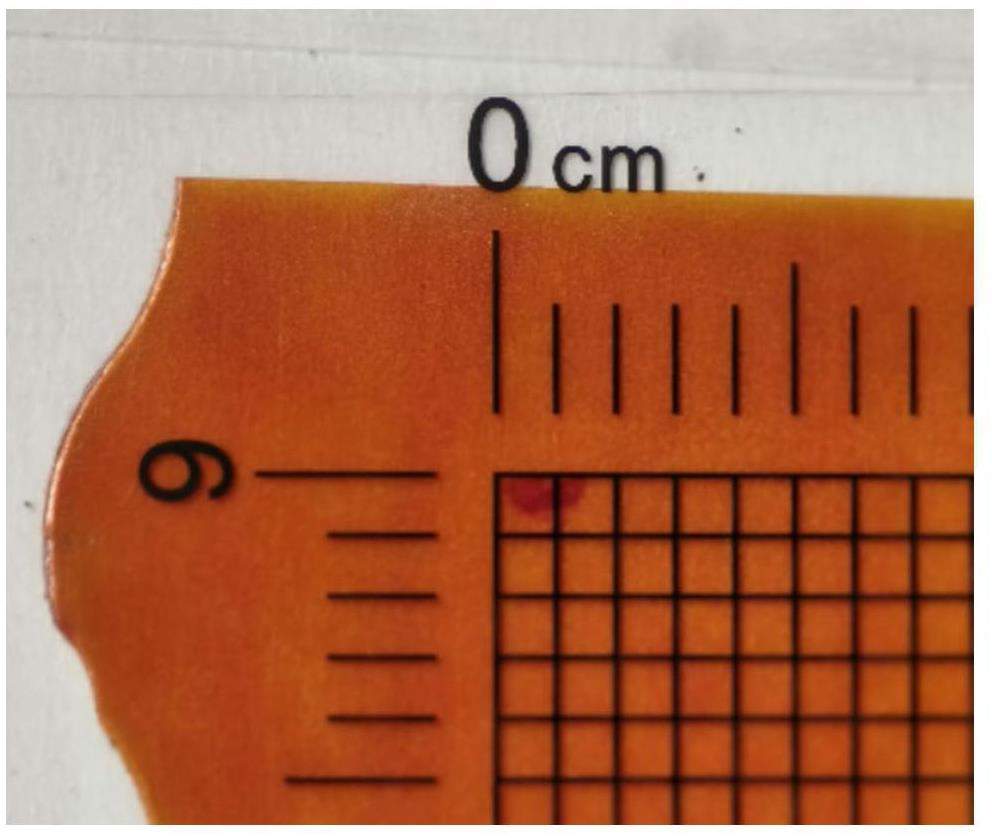

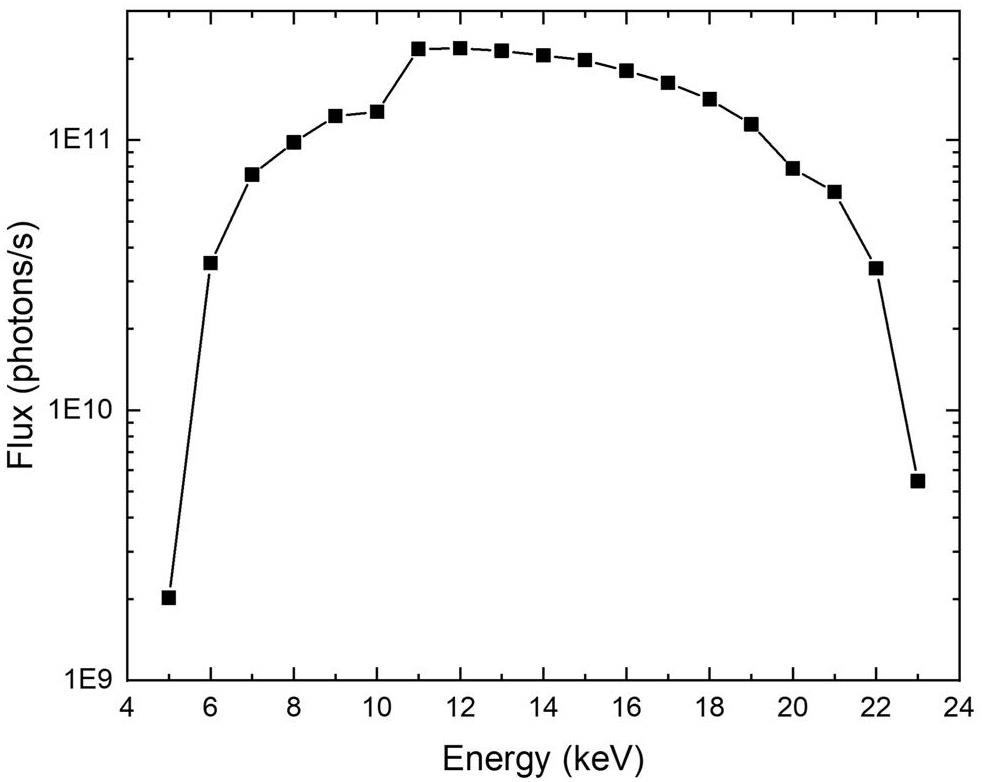

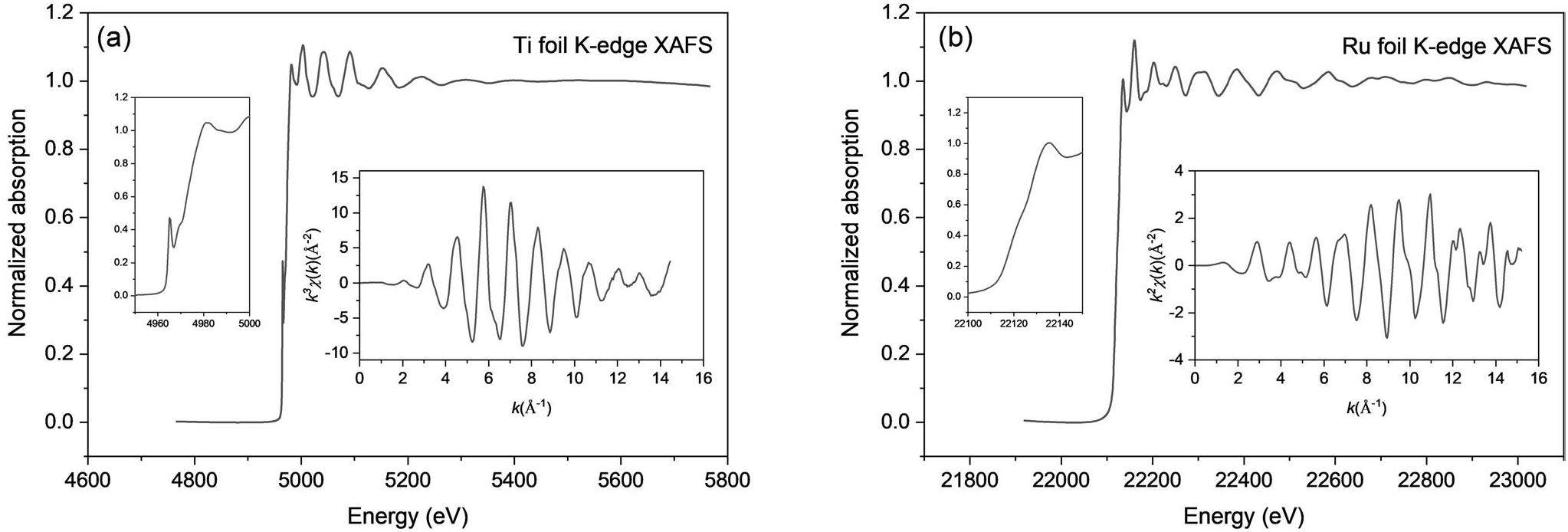

To evaluate the performance of the XAFS experimental platform, we inspected various aspects of its capabilities. The common parameters are summarized in Table 1. The BL17B XAFS platform has an energy range of 5–23 keV, which permits XAFS data collection for elements spanning Ti to the K-edge of Ru and Cs to the L3-edge of Bi, as shown in Fig. 11. Notably, Tl, Pm, and actinide elements are not permitted for testing at this platform. This decision was based on concerns regarding chemical toxicity and experimental safety, despite the L-edge energies being within the accessible range of the monochromator. To measure the XAFS sample spot size, we used X-ray-sensitive exposure paper to record the central beam spot at the sample position. As depicted in Fig. 12, the spot size is approximately 1.5 mm × 0.6 mm (H × V). By recording the current values of the 100% N2-filled I0 ionization chamber under various incident beam energies, the corresponding beam flux was calculated using Hephaestus software [42]. As shown in Fig. 13, the flux in the central energy range (7–21 keV) is on the order of 1011 photons/s, which is our recommended working energy range. For 5–7 keV, the flux decreases quickly, owing to absorption by substances along the optical path. At 21–23 keV, the flux declines quickly with the reflectivity of the Rh-coated collimating and focusing mirrors. Nevertheless, the minimum flux within the XAFS energy range was greater than 109 photons/s, which allowed high-quality data collection for high-concentration samples. As shown in Fig. 14, high-quality K-edge XAFS data were obtained at the experimental energy limits of Ti and Ru foils. The pre-edge peak of the Ti foil, which was approximately 2 eV wide, was clearly observed. The amplitude and signal-to-noise ratio of the EXAFS typically decrease rapidly with an increasing k value at a rate of k-2. However, both EXAFS spectra in Fig. 14 remain smooth up to 15 Å-1 without significant noise, demonstrating the capability of the platform to acquire high-quality data within its working energy range.

| Facility | SSRF |

|---|---|

| Light source | Bend Magnet |

| Electron energy (GeV) | 3.5 |

| Magnetic field intensity (T) | 1.27 |

| Beam intensity (mA) | 200 |

| Beamline acceptance angle (mrad2) | 1.5 × 0.1 |

| Energy range (keV) | 5-23, 7-21(recommended) |

| Energy resolution (ΔE/E) | 2 × 10-4 at 12 keV |

| Flux at sample (photons/s) | 2.2 × 1011 at 12 keV |

| Focused spot size (mm2) | 1.5 × 0.6 (H×V) |

| Harmonic rejection effect | XAFS amplitude attenuation < 1% |

We further assessed the detection limits achievable under different experimental modes to provide guidance for selecting the optimal experimental mode for various sample conditions. We prepared copper (II) phthalocyanine (CuPc, C32H16CuN8) samples diluted with LiF at varying Cu concentrations, collected their Cu K-edge XAFS spectra, and determined the detection limits based on the signal-to-noise ratios of the EXAFS and XANES data. As shown in Table 2, the mass fractions of the samples range from 3.4 wt% to 0.01 wt%, and their corresponding Cu absorption concentration (µA/µT) decreased from 60 to 0.3 µ%. To ensure the accuracy of the concentration, low-concentration samples were further diluted with high-concentration samples. Each sample was meticulously ground to ensure uniform mixing and then compressed into tablets with a diameter of 10 mm. Uniform tablet thickness helps avoid the pinhole effect [43], which can also lead to data distortion. The quantity of each sample is controlled to have a total absorption thickness (µTd) of 2–4, which maximizes the signal-to-noise ratio according to the Nordfors criterion [44]. The actual measured total absorption thickness and jump edge in Table 2 aligned with the intended concentration, demonstrating the reliability of the sample preparation.

| Sample | Mass fraction wA/wT | Absorption concentration µA/µT | Total absorption thickness µT d | Jump edge ΔµAd |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.4% | 60% | 2.5 | 1.3 |

| 2 | 0.7% | 20% | 3.2 | 0.6 |

| 3 | 0.3% | 10% | 3.2 | 0.3 |

| 4 | 0.15% | 5% | 3.4 | 0.15 |

| 5 | 0.07% | 2.5% | 2.8 | 0.06 |

| 6 | 0.04% | 1.5% | 2.7 | 0.035 |

| 7 | 0.014% | 0.5% | 3.8 | 0.016 |

| 8 | 0.01% | 0.3% | 3.1 | 0.009 |

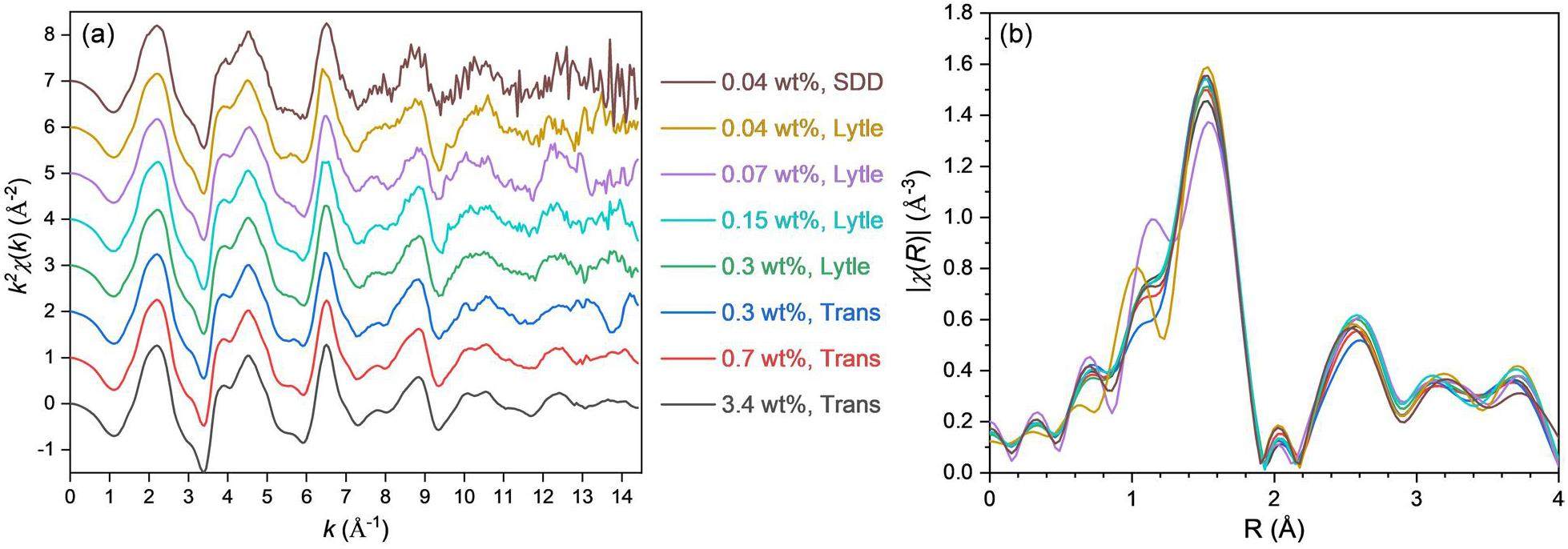

Normalized Cu K-edge EXAFS data for the diluted CuPc samples are shown in Fig. 15(a). The higher-concentration data exhibit better signal-to-noise ratios. In transmission mode, the 3.4 wt% sample remained smooth up to 14 Å-1. When it drops to 0.3 wt%, the data signal-to-noise ratio decreases, but the data are reliable up to 12.5 Å-1. Compared with the Lytle fluorescence data, the transmission data of this sample exhibited less noise but significant distortion beyond 12.5 Å. Hence, 0.3 wt% (10 µ%) is the EXAFS detection limit for the transmission mode. Therefore, using the transmission mode is recommended for samples with a concentration above 10% to achieve the optimal signal-to-noise ratio and keep the jump height greater than 0.2 to minimize data distortion. In the Lytle fluorescence mode, noise becomes more noticeable when the Cu mass fraction drops to 0.04 wt% (1.5 µ%). However, the data remain consistent with the real signal trend until 12.5 Å-1, which is acceptable. In the SDD fluorescence mode, the EXAFS data of the 0.04 wt% sample show increased noise compared with the corresponding Lytle mode data, yet it aligns better with the actual signal. This is because the SDD selectively collects characteristic fluorescent signals; however, the total intensity is not as high as that of the Lytle detector. Therefore, 0.04 wt% (1.5 µ%) was proposed as the EXAFS detection limit for the fluorescence mode.

Figure 15(b) shows the Fourier transforms of the k2-weighted Cu K-edge EXAFS spectra of CuPc samples with different Cu concentrations. The Fourier transform k-range is 3–12 Å⁻¹. All the data exhibit similar peak shapes within the range of 1.3–4 Å, especially at the first shell at 1.53 Å, owing to the nearest neighboring nitrogen atoms. The peak heights show a fluctuation of approximately 10%, which is reasonable because of the experimental error. These results indicate that the low-concentration data reflect real information and possess good reliability. Moreover, for samples collected under the Lytle mode (0.07 and 0.04 wt%), pseudo-peaks appear near 1.1 Å, which are caused by noise. These results suggest that data from low-concentration samples near the detection limit should be handled with caution. Fitting analyses were conducted on the first shell to quantitatively assess the reliability of the low-concentration data. The R fitting range is 1.3-2 Å⁻¹ for (0.07 wt%, Lytle) and (0.04 wt%, Lytle), and 1–2 Å⁻¹ for others. Table 3 shows the fitting results, indicating that the Cu-N interatomic distance d in the first shell for all samples is approximately 1.94 Å, with the coordination number N ranging from 3.8 to 4.1. Exceptions include (0.04 wt%, Lytle), which has a d value of 1.95 Å, and (0.07 wt%, Lytle), which has a slightly lower N value of 3.5. These results further validate/s the conclusion that low-concentration data can also be reliable; however, when handling low-concentration samples near the detection limit, being vigilant about false peaks and their potential impacts is essential.

| Sample | Shell | N | d (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.4 wt%, Trans | Cu-N | 3.9±0.3 | 1.94±0.01 |

| 0.7 wt%, Trans | Cu-N | 3.8±0.3 | 1.94±0.01 |

| 0.3 wt%, Trans | Cu-N | 3.9±0.4 | 1.94±0.01 |

| 0.3 wt%, Lytle | Cu-N | 4.0±0.5 | 1.94±0.01 |

| 0.15 wt%, Lytle | Cu-N | 4.1±0.8 | 1.94±0.01 |

| 0.07 wt%, Lytle | Cu-N | 3.5±0.8 | 1.94±0.02 |

| 0.04 wt%, Lytle | Cu-N | 3.9±0.9 | 1.95±0.02 |

| 0.04 wt%, SDD | Cu-N | 4.0±2.5 | 1.94±0.05 |

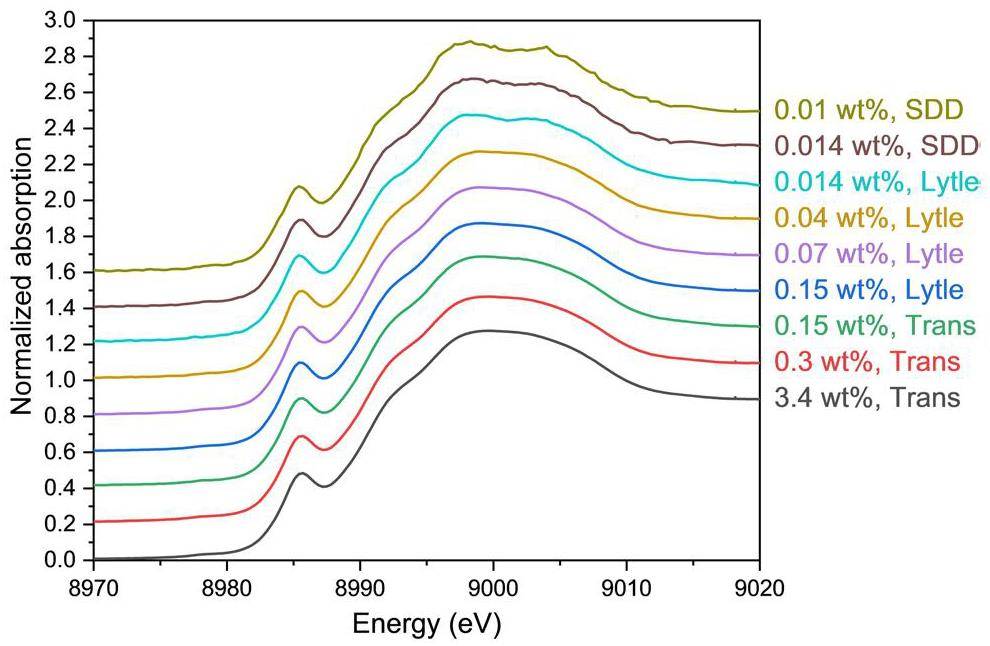

The normalized Cu K-edge XANES data for the diluted CuPc samples are shown in Fig. 16. The detection limit for XANES was as low as 0.01 wt% (0.3 µ%), which was approximately one-fifth of that for EXAFS. For samples with concentrations exceeding this threshold, the noise in the XANES data was insignificant; however, potential issues with data distortion must not be overlooked. Such risks can be effectively mitigated by employing appropriate experimental modes. In transmission mode, the jump edge of the 0.15 wt% (5 µ%) sample is only 0.15. Moreover, lower concentrations, along with fewer jump edges, can introduce distortion. Hence 0.15 wt% (5%) can be regarded as the XANES detection limit for the transmission mode, with a recommended jump edge above 0.2. In the Lytle fluorescence mode, the self-absorption effect must be considered. The XANES data of the 0.15 wt% (5 µ%) sample align with that of the 3.4 wt% sample, indicating no significant self-absorption effect below this concentration. The Lytle mode is capable of detecting concentrations as low as 0.014 wt% (0.5 µ%), with XANES signals remaining consistent with actual signatures. The SDD fluorescence mode further enhanced the sensitivity, allowing detection down to 0.01 wt% (0.3 µ%).

In summary, the above experiments demonstrate that for EXAFS, the detection limit for the transmission mode is 0.3 wt% (10 µ%). Samples with concentrations above this value are recommended to be tested in the transmission mode and to maintain a jump height of 0.2 or higher. For concentrations below that, the fluorescence mode is more suitable with a detection limit as low as 0.04 wt% (1.5 µ%). In the case of XANES, the corresponding detection limits decrease further to 0.15 wt% (5 µ%) and 0.014 wt% (0.5 µ%). Notably, the detection limit mentioned here was derived under specific ideal conditions: the samples were primarily composed of light elements without significant amounts of heavy atoms, which can generally introduce additional noise and increase the actual detection threshold. Although the detection limits may not be directly applicable to all complex samples, they still offer a valuable reference benchmark for assessing the feasibility of XAFS experiments. Again, these ultralow detection limits reaffirm the outstanding capability of the XAFS platform to acquire high-quality experimental data and render it particularly valuable for characterizing complex systems such as biological, environmental, and material samples that contain minute active components.

Conclusion

This work presents the successful development of an advanced XAFS platform at NFPS BL17B at SSRF, which alternates with existing diffraction experimental techniques and extends the structural characterization capabilities of BL17B’s from long-range to short-range orders. The key innovations of this new platform are as follows. First, harmonic suppression mirrors were employed to effectively reduce higher-order harmonics in the beam to meet the stringent purity requirements of XAFS experiments. Second, the platform features a multifunctional testing station constructed with three transmission ionization chambers and two switchable fluorescence detectors to enable the simultaneous collection of transmission and fluorescence data as well as the synchronous comparison of target and reference samples, thereby enhancing data integrity and transferability. Furthermore, the platform is equipped with an automated high-capacity sample wheel that facilitates the remote control of sample loading and includes automatic sample assessment and sampling functions that significantly boost experimental efficiency. Automatic gain control ensures linearity and a high signal-to-noise ratio across various signal intensities to guarantee the accuracy and reliability of the data. The platform excelled within the energy range of 5-23 keV, covering the K-edges of elements from Ti to Ru and the L3-edges of elements from Cs to Bi. In an experiment conducted to study the Cu K-edge XAFS of low-concentration CuPc/LiF samples, we achieved an EXAFS detection limit as low as 0.04 wt% and an even lower XANES detection limit of 0.01 wt%. These results unequivocally demonstrate the exceptional performance of this platform in acquiring high-quality XAFS data, suggesting its valuable application in characterizing complex systems, including biological, environmental, and material samples that contain minute active components.

Shanghai synchrotron radiation facility

. Chin. Sci. Bull. 54, 4171–4181 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11434-009-0689-yThe protein complex crystallography beamline (BL19U1) at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 30, 170 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-019-0683-2Upgrade of crystallography beamline BL19U1 at the Shanghai synchrotron radiation facility

. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 57, 630–637 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1107/S1600576724002188Upgrade of macromolecular crystallography beamline BL17U1 at SSRF

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 29, 68 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-018-0398-9Crystal structure determination of a chimeric FabF by XRD

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 28, 123 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-017-0281-0How to GIWAXS: grazing incidence wide angle X-ray scattering applied to metal halide perovskite thin films

. Adv. Energy Mater. 13,GIWAXS experimental methods at the NFPS-BL17B beamline at Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility

. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 31, 968–978 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1107/S1600577524004764XAFS and SRGI-XRD studies of the local structure of tellurium corrosion of Ni–18%Cr alloy

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 30, 153 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-019-0673-4Molecular basis for METTL9-mediated N1-histidine methylation

. Cell Discov. 9, 38 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41421-023-00548-wCharacterization of a promiscuous DNA sulfur binding domain and application in site-directed RNA base editing

. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, 10782–10794 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkad743Humoral immune response to circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants elicited by inactivated and RBD-subunit vaccines

. Cell Res. 31, 732–741 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41422-021-00514-9Mobilization and transformation of arsenic from ternary complex OM-Fe(III)-As(V) in the presence of As(V)-reducing bacteria

. J. Hazard. Mater. 381,Proton and copper binding to humic acids analyzed by XAFS spectroscopy and isothermal titration calorimetry

. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 4099–4107 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b06281Fabrication of red-emitting perovskite LEDs by stabilizing their octahedral structure

. Nature 631, 73–79 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07531-9Aqueous synthesis of perovskite precursors for highly efficient perovskite solar cells

. Science 383, 524–531 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adj7081Cascade synthesis of benzotriazulene with three embedded azulene units and large stokes shifts

. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62,Single-crystal X-ray diffraction structures of covalent organic frameworks

. Science 361, 48–52 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aat7679Synchrotron radiation-based materials characterization techniques shed light on molten salt reactor alloys

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 31, 6 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-019-0719-7A biological perspective towards a standard for information exchange and reporting in XAS

. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 25, 944–952 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1107/s1600577518008779Arsenic trioxide controls the fate of the PML-RARα oncoprotein by directly binding PML

. Science 328, 240–243 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1183424Methods and mechanisms of the interactions between biomacromolecules and heavy metals

. Chin. Sci. Bull. 67, 4192–4205 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1360/tb-2022-0636Boosting hydrogen peroxide production via establishment and reconstruction of single-metal sites in covalent organic frameworks

. SusMat 3, 379–389 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1002/sus2.125Manipulating the spin state of co sites in metal-organic frameworks for boosting CO2 photoreduction

. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 3241–3249 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.3c11446Anion–π interactions suppress phase impurities in FAPbI3 solar cells

. Nature 623, 531–537 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06637-wStatus of the X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) beamline at the Australian synchrotron. x-ray absorption fine structure - XAFS13

:Two-mirror device for harmonic rejection

. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 60, 2027–2029 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1140867Measurement of soft X-ray absorption spectra with a fluorescent ion chamber detector

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 226, 542–548 (1984). https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-9002(84)90077-9Soller slit design and characteristics

. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 19, 185–190 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1107/S0909049511052319X-ray filter assembly for fluorescence measurements of X-ray absorption fine structure

. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 50, 1579–1582 (1979). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1135763Soller slits automatic focusing method for multi-element fluorescence detector

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 27, 115 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-016-0105-7Vortex: a new high performance silicon multicathode detector for XRD and XRF applications

.XAFS Data Interchange: a single spectrum XAFS data file format

. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 712,ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy usingIFEFFIT

. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 12, 537–541 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1107/s0909049505012719Size effect of powdered sample on EXAFS amplitude

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. 212, 475–478 (1983). https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-5087(83)90730-5The statistical error in x-ray absorption measurements

. Arkiv Fysik 18, 37-47 (1960).The authors declare that they have no competing interests.