Introduction

The dwindling reserves of fossil fuels and the desire to become less dependent on energy have recently propelled the need for safe and clean nuclear power to reach the forefront of power generation. Although current nuclear power plants perform well even beyond their expected lifetime, there is a desire for newer, safer, and more efficient designs [1, 2]. These factors have driven the development of novel nuclear power generation systems to meet the growing energy demand and protect the environment. However, accurate modeling simulations are required to analyze new core designs for reactors because of the significant capital costs associated with the construction of experimental reactors [3, 4]. One of the limiting factors of these simulations is the accuracy of the nuclear data inputs [5]. An important part of assessing data credibility is the benchmark experiment [5, 6].

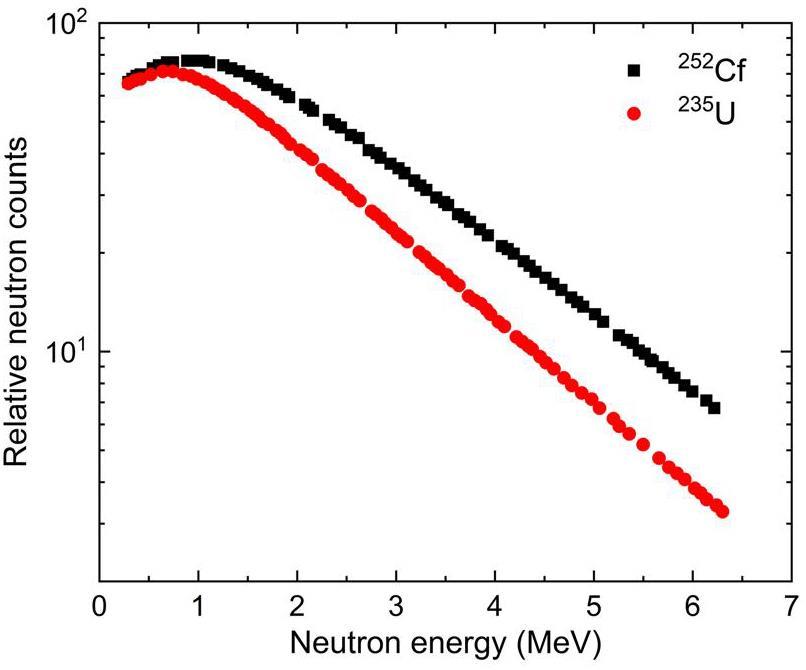

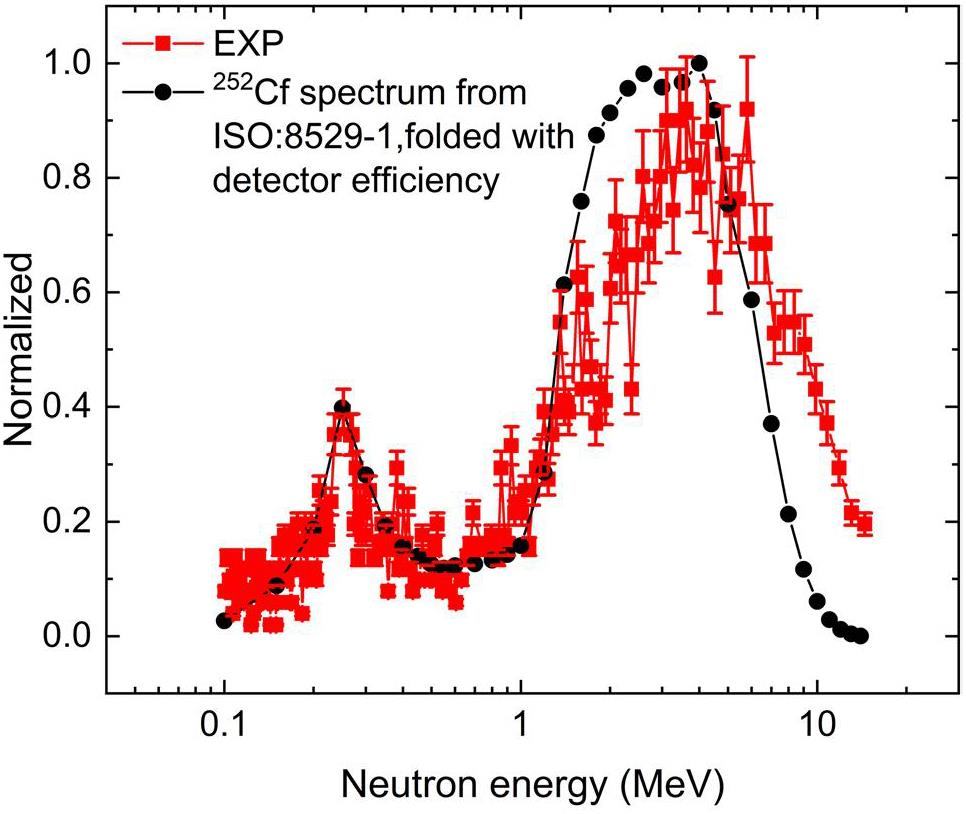

Benchmark experiments provide a means of validating and improving nuclear data by comparing experimental results with theoretical predictions. Given their importance, China has been conducting neutron integral experiments since the 1960s [7]. Because of the half-life and production costs of the isotope neutron source, the D-T neutron generator has been primarily used for benchmark experiments, for examples those conducted by the China Academy of Engineering Physics (CAEP) [8-11] and the China Institute of Atomic Energy (CIAE) [12, 13]. In particular, the CIAE has developed an integral experimental platform to evaluate nuclear data in the fusion energy range [12-18]. However, fission reactors have been the primary source of nuclear energy for a long time. The accuracy of the neutron-evaluated data in the fission energy region is of great significance and application value for developing new reactors and designing miniaturized modular systems. Hence, it is essential to verify nuclear data within the fission energy range. It is well known that the 235UO2 spectrum is a typical fission neutron spectrum. However, 235UO2 requires neutron bombardment to initiate a fission reaction, which makes it unsuitable for this experiment. 252Cf is a spontaneous fission source and its neutron energy spectrum is similar to that of 235UO2, as illustrated in Fig. 1 [19]. Therefore, the 252Cf source is generally used as a substitute for 235UO2 in experiments that simulate the neutron spectrum generated by a fission reactor [19, 20]. Currently, experiments for measuring the leakage neutron spectrum based on a 252Cf source primarily use the recoil proton method, which has a low resolution [21-24]. Additionally, there is a lack of benchmark results for the latest databases, such as the CENDL-3.2 library, because the experiment was conducted relatively early. Consequently, it is essential to conduct benchmark experiments using a 252Cf source.

This study constructed the first leakage neutron spectrum measurement system for benchmark experiments based on the 252Cf source using the time-of-flight (TOF) method in China. The proposed system utilizes γ tagging for coincidence detection. A spherical sample was used for the experiments, with the source positioned at the center of the sphere. The EJ309 liquid organic scintillator and Cs2LiYCl6:Ce (CLYC) detectors were used in conjunction to measure the neutron TOF spectrum, especially in the low energy region. To assess the measurement capability of the system, the measured TOF spectrum without a sample was compared with the spectrum simulated using the Monte Carlo method and the 252Cf standard spectrum in ISO:8529-1 [26]. Subsequently, experiments were conducted using a standard sample (a polyethylene sphere) to verify the reliability of the experimental system. The measured leakage neutron spectra were compared with the results simulated with the ENDF/B-VIII.0, CENDL-3.2, JEFF-3.3, and JENDL-5 libraries in terms of the spectrum shape and ratios of calculation to experiment (C/E) for the neutron flux [26-29]. This study provides a new domestic platform for benchmark experiments and is of great significance for checking and supplementing nuclear databases.

Experiment method

Experiment setup

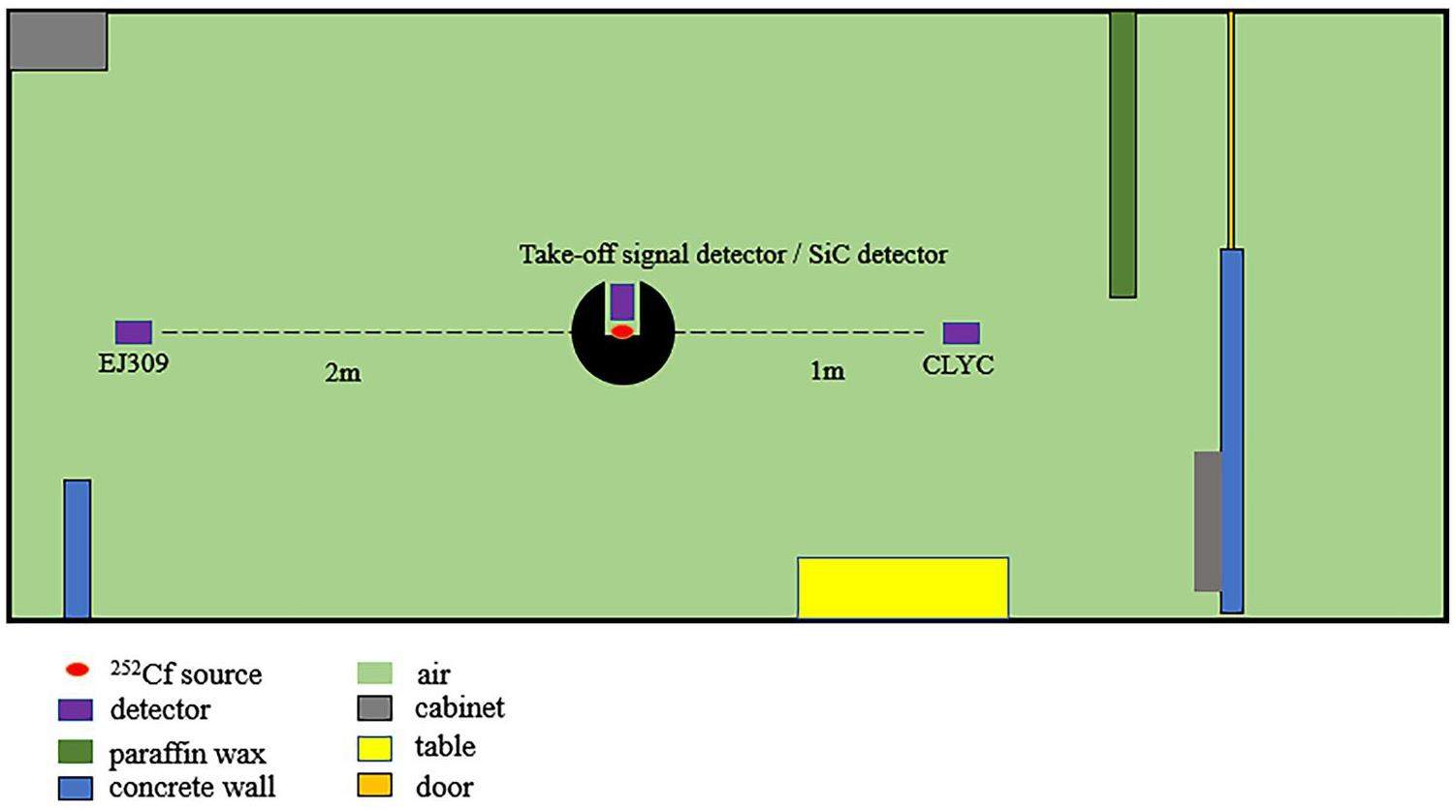

The neutron emission rate of the 252Cf source was greater than 105 n/s in the entire experiment period. The Silicon Carbide (SiC) detector for measuring fission fragments to obtain source neutron information and the take-off signal detector were positioned close to the source. The layout of the experimental platform is illustrated in Fig. 2. The experiments were performed using a spherical sample with the source located at the center of the sphere. This placement method is closer to practical application conditions, and it ensures that the nuclear reaction is carried out evenly in all directions and reduces the influence of the boundary effect. Thus, relevant information regarding the interaction between the neutrons emitted by the source at an angle of

All wave signals were acquired using a CAEN DT5730SB digitizer (14-bit, 500MS/s, 5.12MS/ch) because of its faster signal processing capability and the provided digital pulse processing-pulse shape discrimination (DPP-PSD) software for online pulse shape discrimination (PSD) analysis. When the online analysis is insufficient, the digitized signals can be stored for offline processing [33].

Take-off signal tagging

The measurement principle of the TOF method is expressed in Eq. (1).

Coincidence model

The coincidence mode allows for the setting of a variable length time window. When a pulse is detected in one channel, the window is initiated; if a pulse is detected in the other channel during this period, a coincidence event is logged. The possible types of coincidences that may have occurred during the experimental process are listed in Table 1. Detector 1 was used to measure the take-off signal, whereas detector 2 measured the flight termination signal.

| Particle in detector 1 | Particle in detector 2 | Correlation mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| γ | γ | Correlated γ from the same fission event |

| γ | γ | Single γ scattered between detectors |

| γ | n | Prompt gamma detected in detector 1, prompt neutron detected in detector 2 |

| γ | n | Prompt gamma detected in detector 1, scatter neutron detected in detector 2 |

| other | other | Accidentally coincident events |

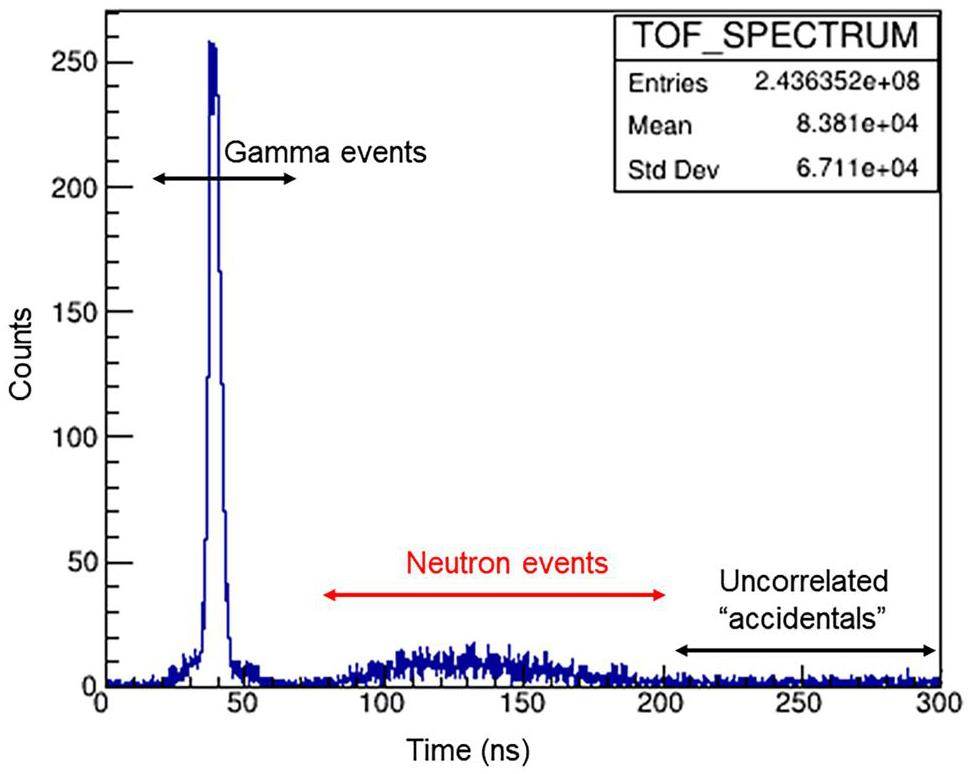

In addition to the γ-n events, the γ-γ coincidence and accidental coincident events still existed in this measurement. Because γ-rays travel at the speed of light, the flight time difference between two coincident γ-rays can reach 6 ns. Regardless of the detector at which they arrive, γ-rays arrive first, following the corresponding fission event. As shown in Fig. 3, all γ–γ coincidence events still fall within the gamma peak region. This initial peak in the TOF spectrum represents double γ-ray events: either a single photon scattered between the detectors or two correlated prompt photons. Therefore, the neutron peak is not affected by the γ–γ coincidence events. Accidentally coincident events can be corrected by taking the average count of the bins that represent the arriving coincidences.

Neutron detection Efficiency determination

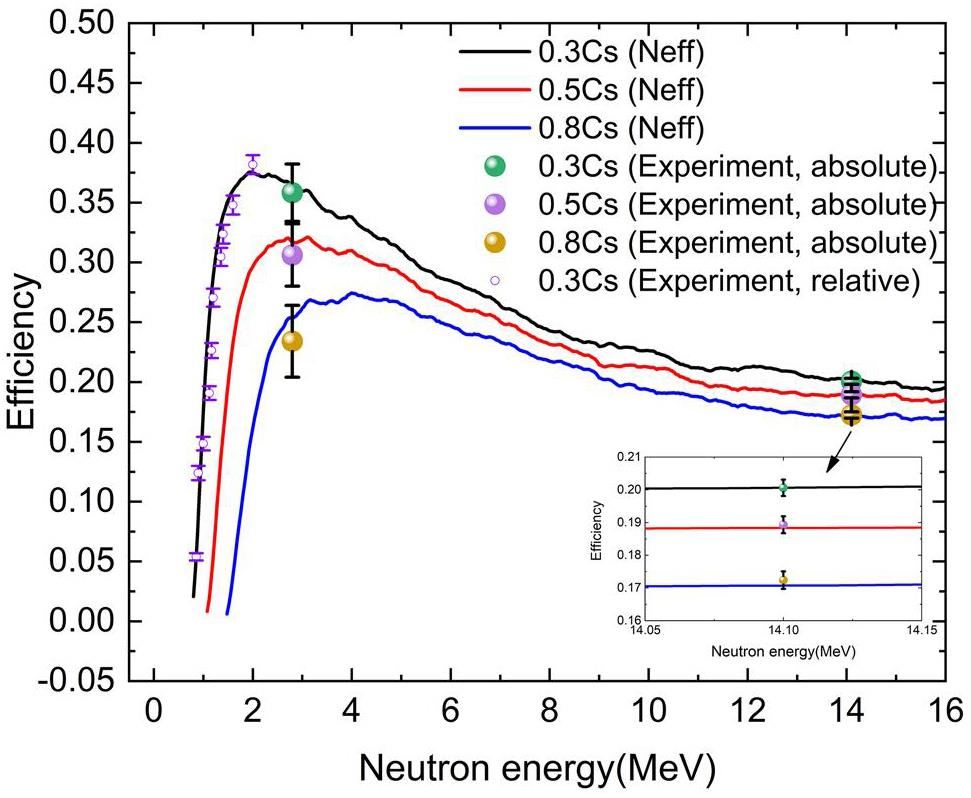

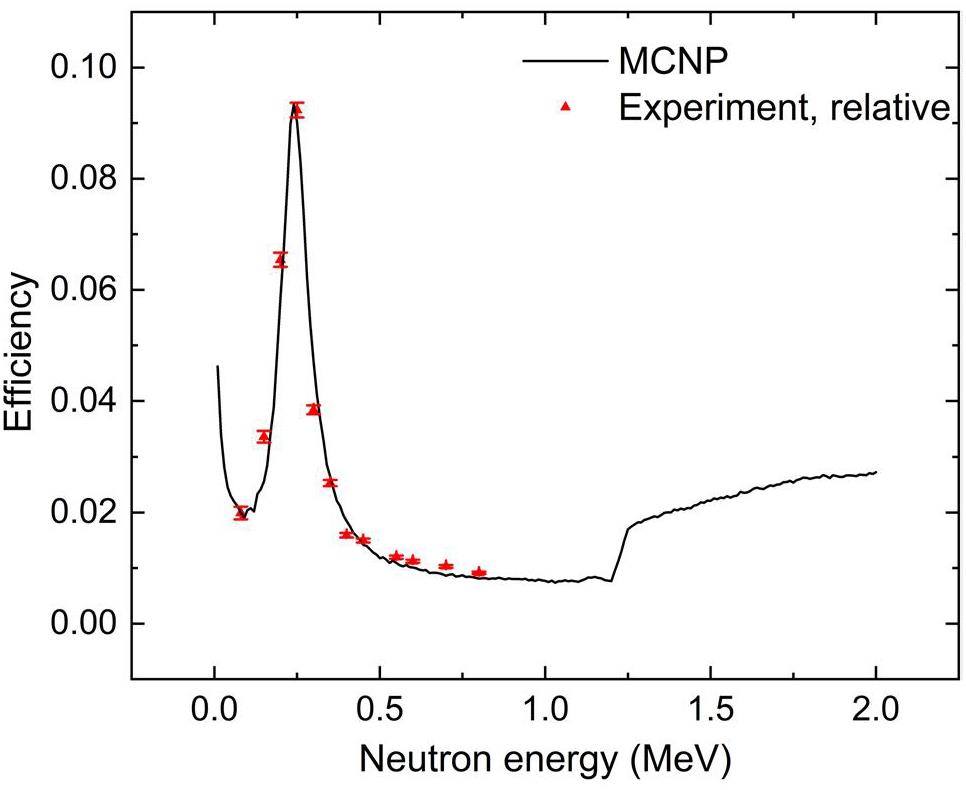

The neutron detector efficiency is a vital parameter that directly affects the accuracy of the simulated TOF spectra. Therefore, for the EJ309 neutron detector, the neutron detection efficiency was accurately obtained using the Monte Carlo code NEFF under different detection thresholds [34]. The reliability of the calculated efficiency curves was experimentally calibrated. The absolute efficiencies of the EJ309 detector were determined by the D-D and D-T neutron generators in CIAE using the TOF method, and the relative detection efficiencies were measured by the 252Cf source. The experimental detection efficiencies are in good agreement with the calculated results of the NEFF code in the range of uncertainty, as shown in Fig. 4.

The detection efficiency curve of the CLYC detector was simulated using the MCNP-4C code. This method has been previously confirmed as feasible, for example, in [35]. The relative detection efficiencies were measured by the 252Cf source using the TOF method. As shown in Fig. 5, the calculated results are consistent with the experimental results within the uncertainty range.

Data processing

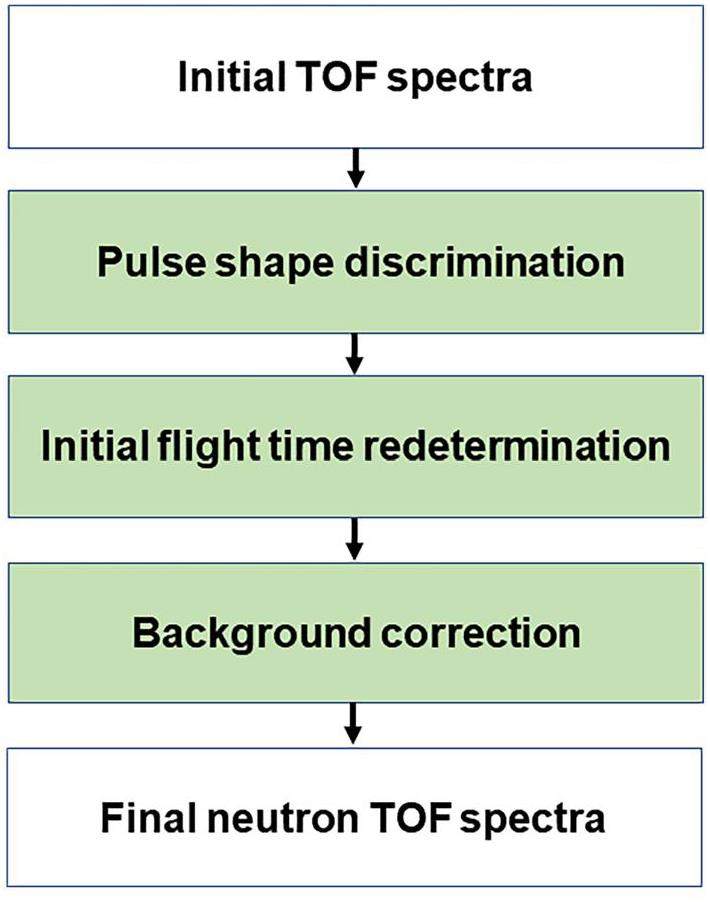

After the neutron TOF spectrum was measured, it was processed according to the process flow shown in Fig. 6 to obtain pure and reliable neutron events. Subsequently, the experimental uncertainty was determined based on the measurement process. The pulse shape discrimination and background correction are described in this section.

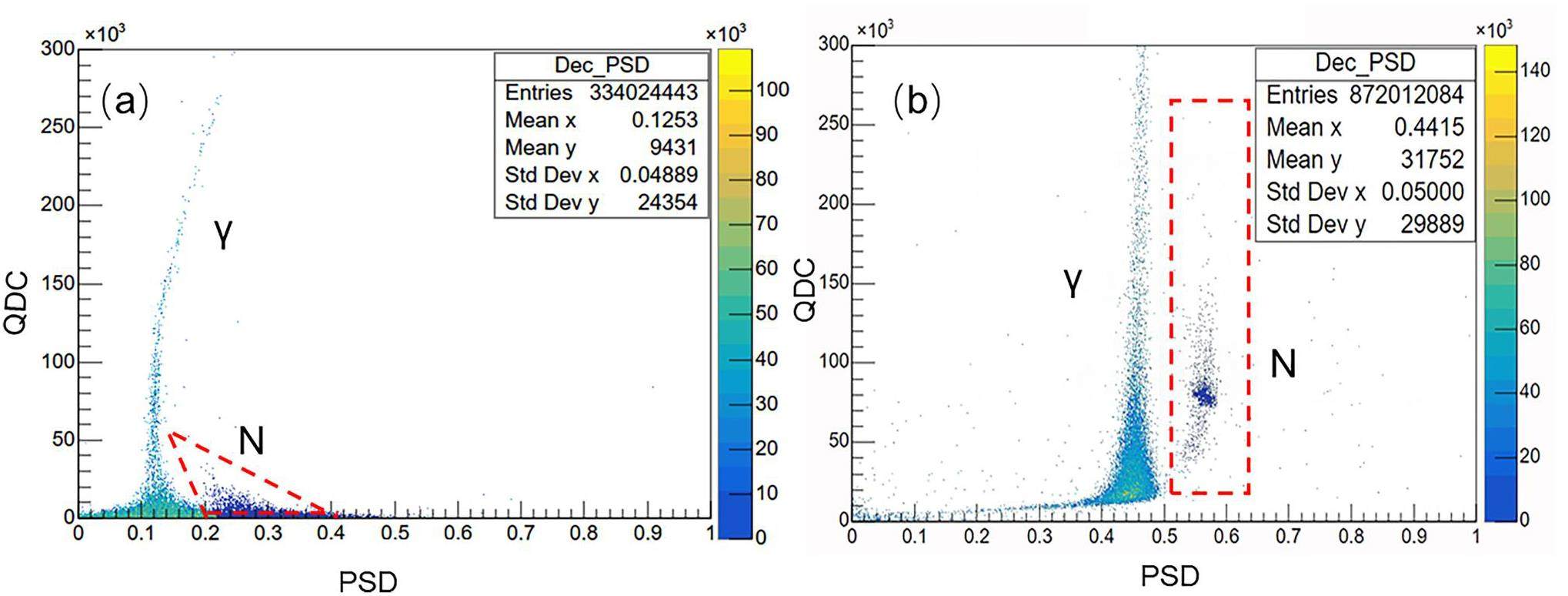

Pulse shape discrimination

To distinguish between the neutrons and γ-ray pulses, a pulse shape discrimination (PSD) technique was performed using the charge integration method [37, 38]. In this experiment, when the TOF spectrum based on 252Cf was measured, the PSD information was obtained by analyzing the data through the waveform acquisition method. The neutron TOF spectra were derived by selecting neutron events, as shown in Fig. 7.

Background correction

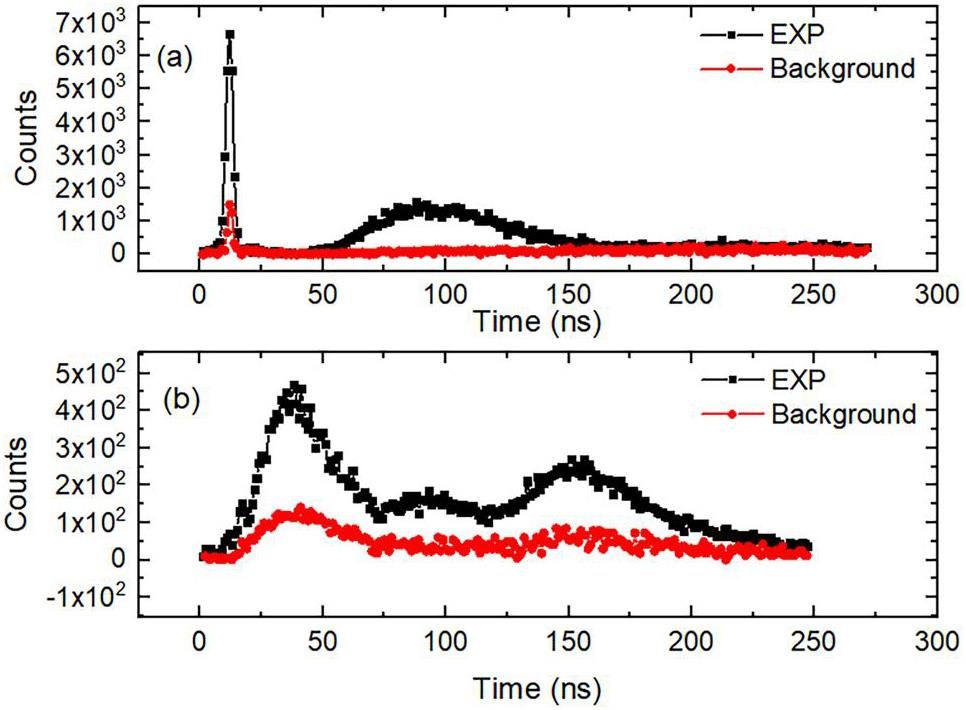

Background correction is crucial for processing the data of the TOF spectrum. This study had three background components: time-independent background, time-dependent neutron background, and time-dependent γ background. The easiest determination was that of the time-independent background, which arose from random events that did not correlate with the fission process occurring in the measurement window. This is shown in Fig. 3, where the count rate flattens at a long TOF spectrum. This background component was eliminated by subtracting the count rate from each channel in the average 210–300 ns region.

The second background component, the time-dependent γ background, originated primarily from the γ decay of fission fragments [38]. This background is not present in the EJ309 and CLYC detectors because PSD can remove the background from γ-rays.

The third background component is the time-dependent neutron background. This affected both the EJ309 and CLYC detectors and primarily originated from prompt fission neutrons scattering off the surrounding structures and scattering back to the neutron detectors. To determine the impact of neutron scattering, the background TOF spectrum was experimentally measured using shadow cones, as shown in Fig. 8. The effect/background ratio measured by the EJ309 detector was greater than 7, and the CLYC detector demonstrated a ratio exceeding 4. Once all these background components were corrected from the experimental signal, a pure TOF spectrum was obtained.

Uncertainties analysis

The uncertainties of the present experiment mainly come from the statistical and systematic uncertainty, as presented in Table 2. Statistical uncertainty includes the uncertainties of neutron counting and 252Cf source neutron counting (used for data normalization). The systematic uncertainty is caused by angle ambiguity and relative error of the detector efficiency.

| Uncertainty components | TOF spectra without sample | TOF spectra with polyethylene standard sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50-161 ns (0.8—8 MeV) | 80—162 ns (0.1–0.8 MeV) | 50—161 ns (0.8–8 MeV) | 80—162 ns (0.1–0.8 MeV) | ||

| Statistical | neutron counting | 2.51% | 8.16% | 2.40% | 7.76% |

| 252Cf source neutron counting | 1.31% | 1.31% | 1.22% | 1.22% | |

| Systematic | angle ambiguity | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| neutron detector efficiency | 2.88% | 3.15% | 2.88% | 3.15% | |

| Total | 4.04% | 8.85% | 3.94% | 8.46% | |

It can be observed that the neutron counting uncertainty is the most significant contributor to the overall uncertainty. For more than 80% of the data points, the statistical uncertainties in the neutron counts measured by the EJ309 detector in the range of 0.8–8.0 MeV were below 3%. Meanwhile, the uncertainties in neutron counts measured by the CLYC detector in the range of 0.15–0.8 MeV were approximately 8%. During the experiment, source neutron counts were obtained by monitoring the information of the fission fragment 252Cf. Therefore, the uncertainty of the 252Cf source neutron counting arose from fission fragment counting, which was 1.31% and 1.22%, respectively, in the two experiments. The angular uncertainty induced by deviations in the positioning of the samples and detectors was relatively small at approximately 0.1%. The uncertainty in the detection efficiency stemmed from discrepancies between the experimental and simulated results.

Results

Capability of the neutron spectrum measurement system

To verify the capability of the constructed TOF spectrum measurement system, measurements were first performed without samples.

Time-of-flight spectrum of the EJ309 detector without sample

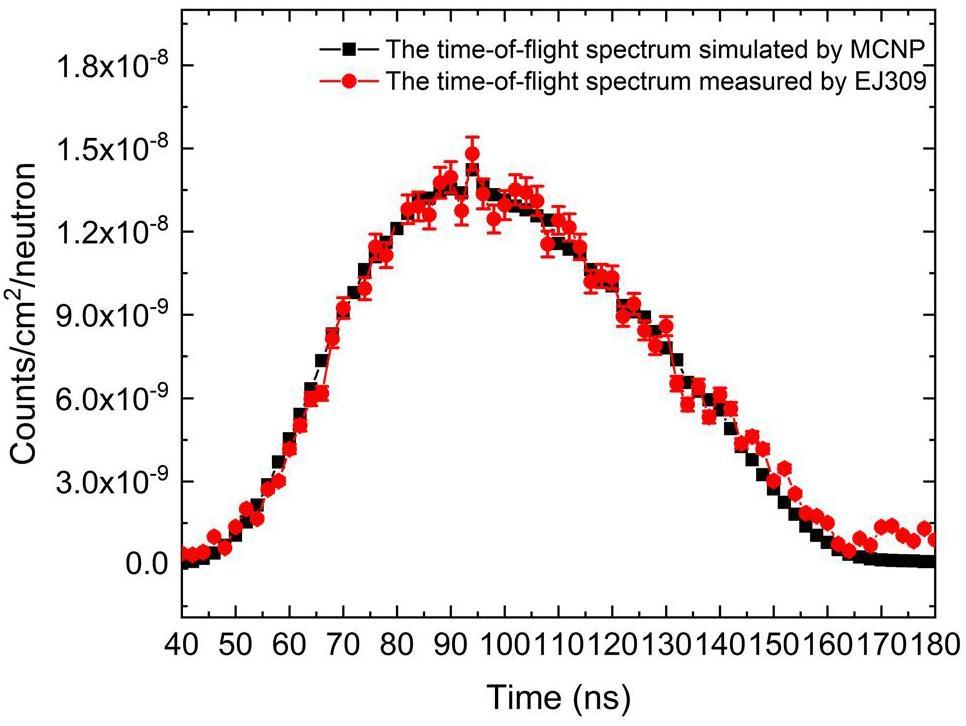

After the data were processed as shown in Fig. 6, the final TOF spectrum was obtained, as shown in Fig. 9. The TOF spectrum simulated by MCNP-4C was compared with the experimental spectrum. The TOF spectrum simulated showed good agreement with the measured spectrum in the 50–162 ns (0.8–8 MeV) range.

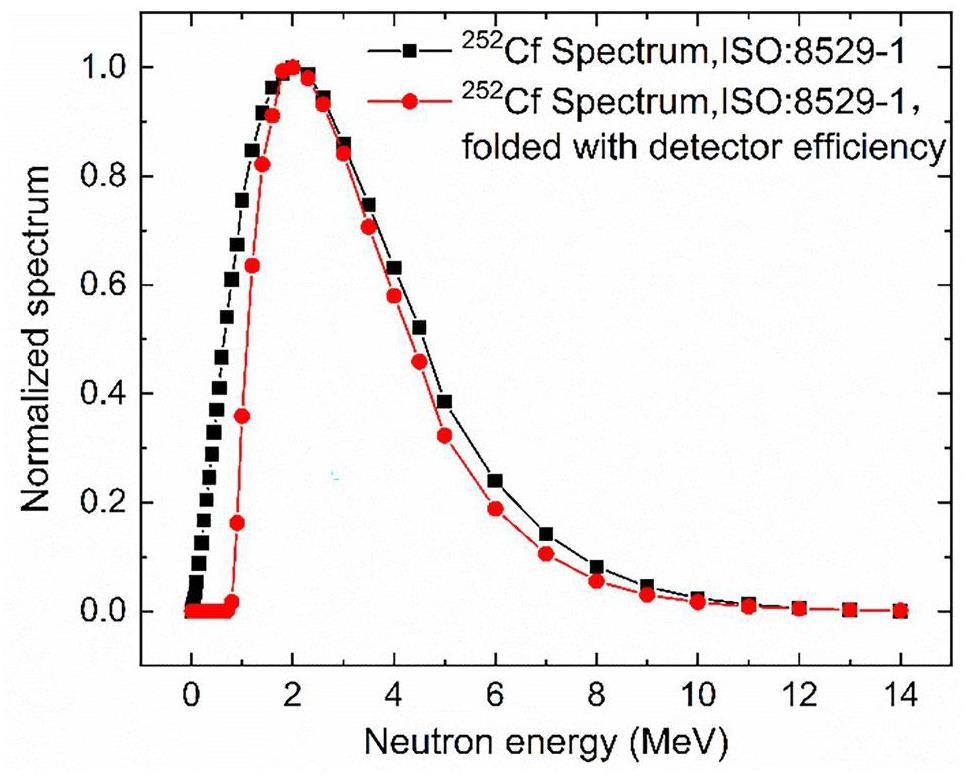

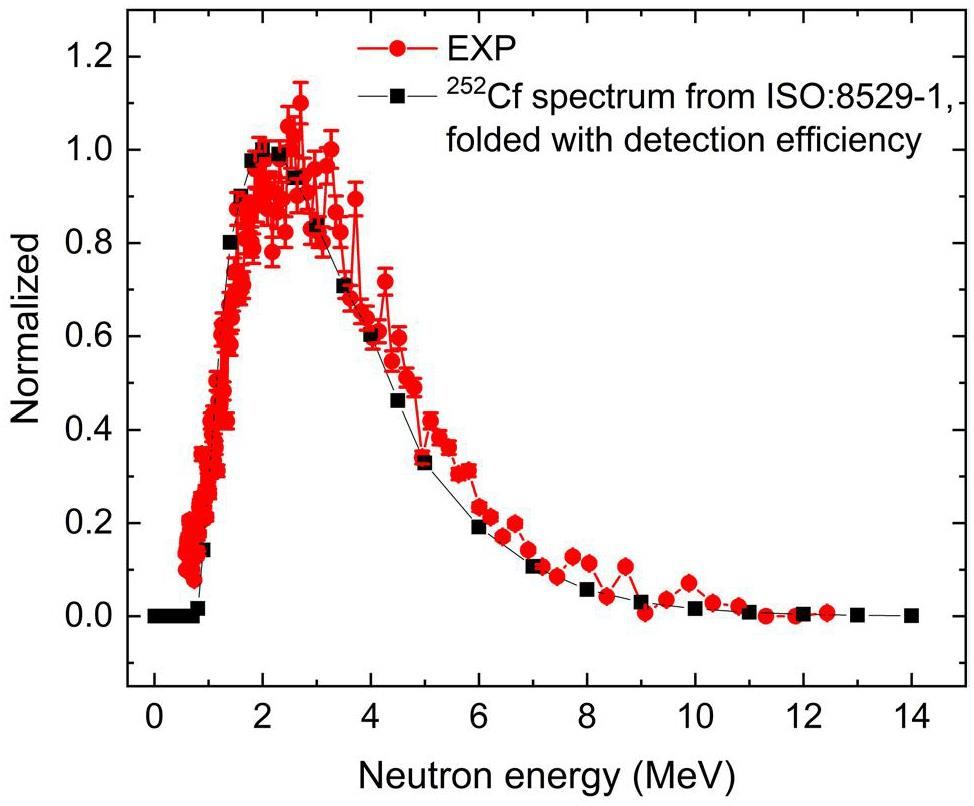

To assess the measurement accuracy of the TOF spectrum platform, the data were converted from the time domain to the energy domain using Eq. (1) and compared with the 252Cf standard spectrum from ISO:8529-1. Owing to the deviation between the Maxwellian standard spectrum at a nuclear temperature of 1.42 MeV and the 252Cf experimental spectrum, the standard spectrum was folded using the detection efficiency curve[39]. Figure 10 shows the effect of detector efficiency on the 252Cf standard spectrum. Then, the experimental spectrum was compared with the folded standard spectrum, as shown in Fig. 11. The experimental spectra were consistent with the standard spectrum in the uncertainty range. Although good consistency was observed across most of the measured data, the high-energy bins of the spectrum were somewhat higher than expected, and the peak value moved towards the high-energy region. This conclusion is similar to that of Becchetti, Blainand, and Alexander [20, 40, 41]. Two reasons may explain this. First, this could be a systematic error stemming from the assumption that prompt neutrons and γ-rays are simultaneously produced at the same moment in the measurement system. Typically, prompt fission γ-rays are emitted within a nanosecond after the fission event. However, some fission fragments exist in metastable states that decay over longer periods [42]. For short flight times, even minor delays in the gamma emission times would lead to an overestimation of the neutron energy, resulting in an overpopulation of the high-energy bins [41]. Second, the 250Cf in the Cf source also has a certain probability of spontaneous fission, as presented in Table 3. When the 252Cf source was produced, the atomic number ratio of 252Cf to 250Cf was approximately 5:1, the decay constant ratio was approximately 5:1, and the spontaneous fission branching ratio was approximately 40:1. Therefore, at the initial stage, the contribution of 250Cf to the neutron emissivity was approximately 0.1%, which had a small effect on the energy spectrum of 252Cf. However, the contribution to the neutron emissivity of 250Cf gradually increased with time. This also affected the energy spectrum of 252Cf.

| Isotope | Half life (a) | Decay constant (s-1) | Spontaneous fission probability (%) | Average neutron number of each fission |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 252Cf | 2.645 | 8.304×10-9 | 3.092 | 3.767 |

| 251Cf | 898 | 2.445×10-11 | 0 | – |

| 250Cf | 13.08 | 1.679×10-9 | 0.077 | 3.52 |

| 248Cm | 3.48×105 | 6.311×10-14 | 8.39 | 3.16 |

Time-of-flight spectrum of CLYC detector without sample

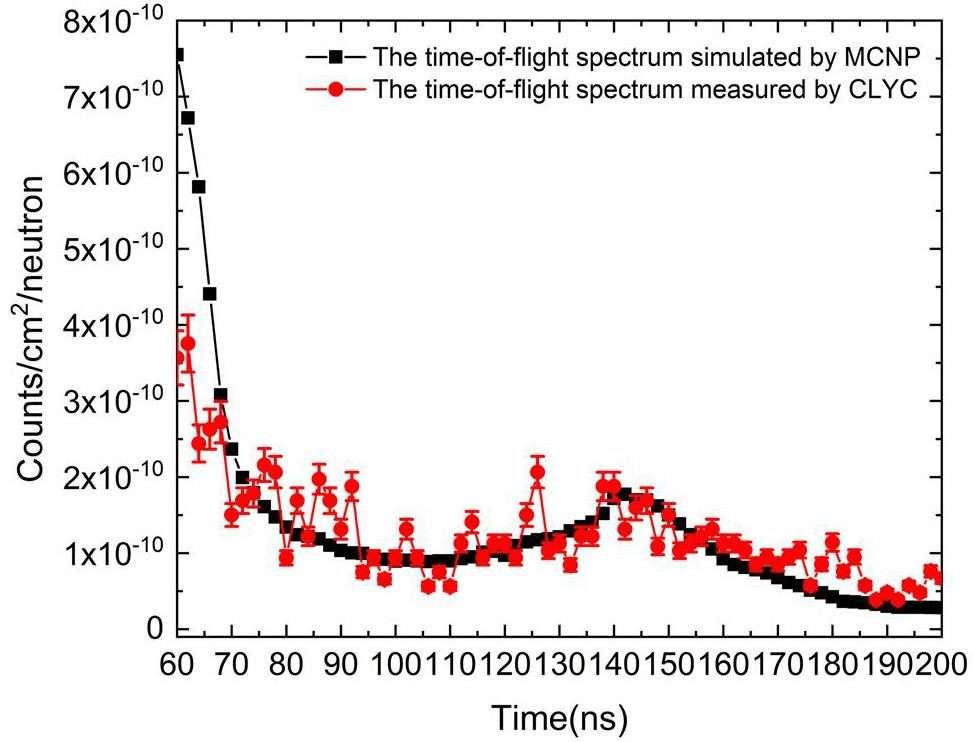

After the data was processed as shown in Fig. 6, the final TOF spectrum was obtained, as shown in Fig. 12. The TOF spectrum simulated by MCNP-4C showed the same trend as the measured spectrum in the 80–187 ns (0.15–0.8 MeV) range.

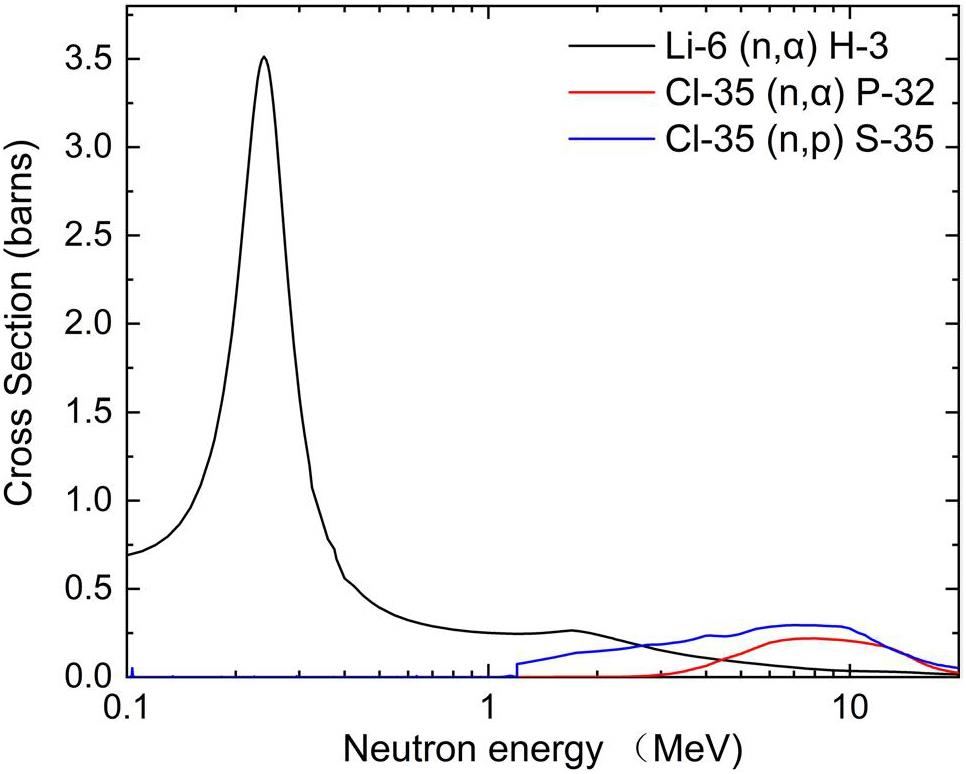

Similarly, the TOF spectrum was converted from the time domain to the energy domain to yield the final PFNS. In Fig. 13, the 252Cf standard spectrum from ISO:8529-1 is folded with the efficiency curve of the CLYC detector. The final comparison results showed that the shape of the experimental spectrum matched the peak of the ISO:8529-1 spectrum in the low-energy regions. However, the TOF spectrum in the 1.2–5 MeV range appeared slightly lower than expected. In contrast, those in the range over 5.0 MeV were higher than the standard spectrum, with the peak value moving towards the high-energy region. This is related to the CLYC detector that detects neutrons using nuclear reactions. The neutron recorded by the CLYC detector is mainly caused by the following reactions [37]: (1) 6Li(n, t)α (Q-value = 4.783 MeV) thermal neutron reaction;(2) 6Li(n, t)α fast neutron reaction; (3) 35Cl(n, p)35S (Q = 0.615 MeV) fast neutron reaction and (4) 35Cl(n, α)32P (Q = 0.937 MeV)fast neutron reaction. The reaction cross-sections are shown in Fig 14. It can be seen that the 6Li(n, t)α reaction is mainly effective when measuring neutrons in the 0.1–1 MeV range, whereas 35Cl(n, p)35S and 35Cl(n, α)35P are significant for neutron energies higher than 1.2 MeV. Moreover, a quenching factor exists in the 35Cl fast neutron reactions [37]. For example, 2.5 MeV neutrons are detected by the 35Cl(n, p)35S reaction (2.5 MeV neutrons have a cross section of 0.19 b), as a single energy peak at 2.5 MeV and the Q-value of the reaction, multiplied by a proton quenching factor equal to 0.9, is 2.8 MeV. As a result, the shift in the peak position at energies greater than 1.4 MeV leads to poor agreement between the experimental and standard spectra in the high-energy region. However, this also proves that CLYC (95%6Li) is more suitable for measuring TOF spectra in the low-energy region.

Verification of the benchmark experiment reliability with the standard sample

The elastic scattering of neutrons and hydrogen (n–p scattering) was considered as the standard cross section. Therefore, a benchmark experiment using polyethylene (

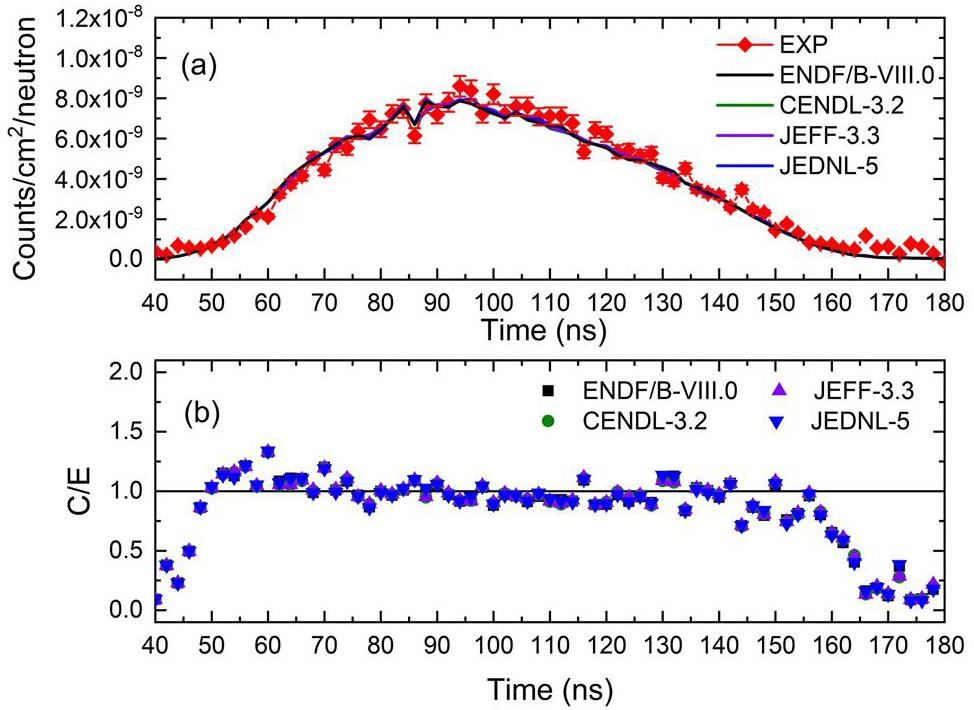

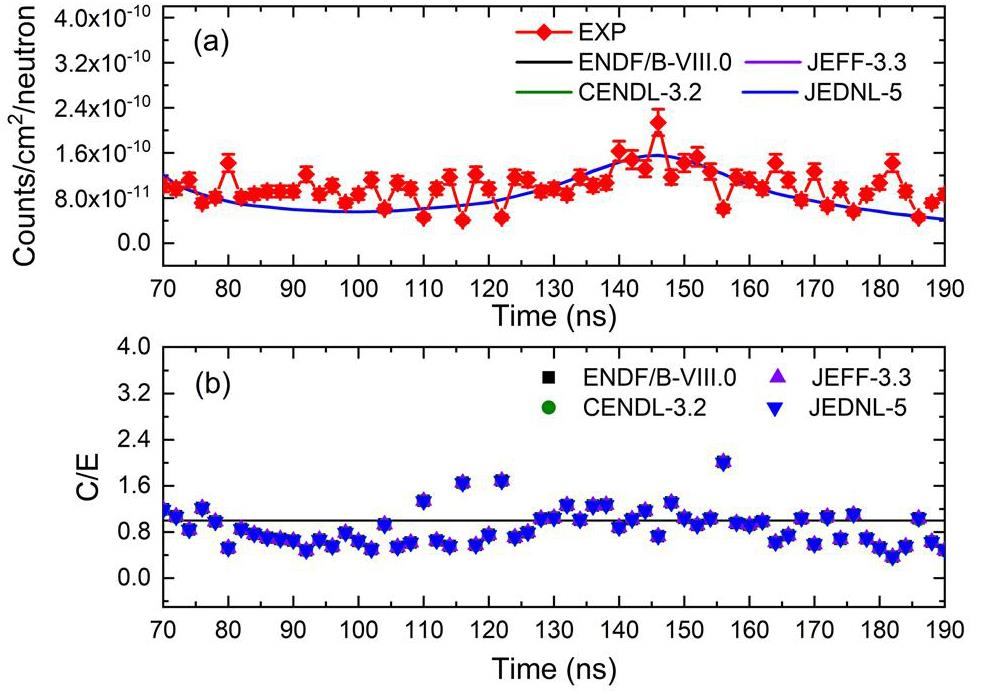

The measured spectra were compared with the spectra simulated using the MCNP-4C code with ENDF/B-VIII.0, CENDL-3.2, JEFF-3.3, and JENDL-5 libraries, as shown in Figs. 15 and 16. The ratios of the calculation to experiment (C/E) obtained by integrating the neutron peaks are listed in Table 4. The measured neutron leakage spectra were consistent with the simulated results obtained using MCNP-4C. In the 0.8–8 MeV (t = 50–162 ns) range, the calculated results were underestimated by approximately 5%, and the uncertainty was less than 3.94%. In the 0.15–0.8 MeV range (t = 80–187 ns), the calculated results were underestimated by approximately 13%, and the uncertainty was less than 8.46%. Therefore, the experimental results agree well with the simulated results in the range of 0.15–8.0 MeV. This indicates that the experimental system and data processing method used in this study are reliable, which ensures the reliability of conducting other sample data measurements.

| Neutron energy (MeV) | C/E value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENDF/B-VIII.0 | CENDL-3.2 | JEDNL-5.0 | JEFF-3.3 | |

| 0.8-8.0 | 0.959±0.038 | 0.956±0.038 | 0.960±0.038 | 0.959±0.038 |

| 0.15-0.8 | 0.880±0.074 | 0.879±0.074 | 0.878±0.074 | 0.880±0.074 |

Summary

In this study, the first neutron leakage spectrum measurement system for benchmark experiments in China based on the 252Cf source with spherical samples using the TOF method was constructed. By utilizing the EJ309 and CLYC detectors, the platform reduced the energy limit of benchmarking based on 252Cf sources. The experimental spectrum without the sample showed excellent consistency compared with the TOF spectrum simulated by the Monte Carlo method and the standard spectrum of ISO:8529-1, proving that the system was able to measure the neutron spectrum in the range of 0.15–8.0 MeV. Subsequently, the neutron leakage TOF spectra of the polyethylene standard sample were measured and the simulated spectra were obtained by MCNP-4C using the evaluated nuclear data from the ENDF/B-VIII.0, CENDL-3.2, JEFF-3.3, and JENDL-5 libraries. The essential characteristic properties of the neutron leakage spectra were well reproduced by these simulations, with deviations of less than 3.94% in the 0.8–8 MeV region and approximately 8.46% in the 0.15–0.8 MeV region. This demonstrates the ability of the leakage neutron spectrum system based on the 252Cf source using spherical samples to perform benchmark tests and proves the feasibility of the entire set of benchmark experimental methods. This study provides a research foundation for evaluating key nuclear data based on the fission spectrum.

Recent progress in nuclear data measurement for ADS at IMP

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 28, 184 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-017-0335-3Performance of the CENDL-3.2 and other major neutron data libraries for criticality calculations

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 8 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-00994-3Evaluating the JEFF 3.1, ENDF/B-VII.0, JENDL 3.3, and JENDL 4.0 nuclear data libraries for a small 100 MWe molten salt reactor with plutonium fuel

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 165 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01141-8Neutronics intergral experiments

. Trends Nucl. Phys. 54, 12 (1995).Measurement of Tritium Production in 6LiD irradiated with neutrons from a critical system

. China Nuclear Science and Technology Report, 51(1998). (In Chinese).The measurement of tritium produced in a 6LiD sphere irradiated by neutrons from D-D and 252Cf

. China Nuclear Science and Technology Report, 486 (1997) (In Chinese).Reaction rates in blanket assemblies of a fusion-fission hybrid reactor

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 23, 242 (2012). https://doi.org/10.13538/j.1001-8042/nst.23.242-246Neutronics experiment of vanadium shell benchmark with14 MeV neutron source

. Atomic Energy Sci. Technol. 157 (2002).Benchmark experiments with slab sample using time-of-flight technique at CIAE

. Ann. Nucl. Energy 136,Benchmark experiment for bismuth by slab samples with DT neutron source

. Fusion Eng. Des. 167,Benchmark experiment on slab 238U with DT neutrons for validation of evaluated nuclear data

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 29 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01386-5Measurement and simulation of the leakage neutron spectra from Fe spheres bombarded with 14 MeV neutrons

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 182 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01329-6Benchmarking of JEFF-3.2, FENDL-3.0 and TENDL-2014 evaluated data for tungsten with 14.8 MeV neutrons

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 27, 28 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-017-0192-0Measurement and analysis of leakage neutron spectra from lead slab samples with D–T neutrons

. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 203,Measurement of leakage neutron spectra for aluminium with DT fusion neutrons and validation of evaluated nuclear data

. Fusion Eng. Des. 171,Fission-neutron spectra measurements of 235U, 239Pu and 252Cf

. J. Nucl. Energy 4, 26 (1972). https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3107(72)90025-1Measurement of prompt fission neutron spectrum for spontaneous fission of 252Cf using γ multiplicity tagging

. Phys. Rev. C 95,Neutron and gamma spectra measurements and calculations in benchmark spherical iron assemblies with 252Cf neutron source in the centre

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A. 476, 358-364 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(01)01470-XApplication of 252Cf neutron source for precise nuclear data experiments

. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 187, 151 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apradiso.2019.06.012Measuring neutron leakage spectra using spherical benchmarks with 252Cf source in its centers

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A. 53, 914 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2018.10.164ENDF/B-VIII. 0: the 8th major release of the nuclear reaction data library with CIELO-project cross sections, new standards and thermal scattering data

. Nucl. Data. Sheets. 148, 1-142 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nds.2018.02.001CENDL-3.2: The new version of Chinese general purpose evaluated nuclear data library

. EPJ Web of Conf. 239, 09001(2020). https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/202023909001Benchmarking and validation activities within JEFF project

. EPJ Web of Conf. 146, 06004 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/201714606004Japanese evaluated nuclear data library version 5: JENDL-5

. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 60, 1 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1080/00223131.2022.2141903Characterization of the new scintillator Cs2LiYCl6: Ce3+

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 29, 11 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-017-0342-4The CLYC-6 and CLYC-7 response to γ-rays, fast and thermal neutrons

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 132, 810 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2015.11.119Digital coincidence acquisition applied to portable beta liquid scintillation counting device

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 24, 3 (2013). https://doi.org/10.13538/j.1001-8042/nst.2013.03.012A method to measure prompt fission neutron spectrum using gamma multiplicity tagging

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 95, 805 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2015.08.060NRESP4 and NEFF4-Monte Carlo codes for the calculation of neutron response functions and detection efficiencies for NE213 scintillation detectors

. (1982)Measurement and Calculation of Leakage Neutron and γ Spectra from Bi Slab Sample

. Atomic Energy Sci. Technol. 584, 55 (2021) (In Chinese). https://doi.org/10.7538/yzk.2020.youxian.0438Pulse shape discrimination with fast digitizers

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 33, 748 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2014.02.032Investigation of CLYC-6 for thermal neutron detection and CLYC-7 for fast neutron spectrometry

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 1029, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2022.166460252Cf fission-neutron spectrum using a simplified time-of-flight setup: An advanced teaching laboratory experiment

. Am. J. Phys. 112, 81 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1119/1.4769032Prompt and delayed gamma-rays from fission

. Phys. Chem. Fission, Salzburg, Austria, 1965.The authors declare that they have no competing interests.