Introduction

In the final stage of nuclear fission, the majority of the nuclear energy is released through the enormous kinetic energy of splitting fission fragments. However, the remaining considerable part of nuclear energy is stored as the excitation energy of the primary fission fragments. Consequently, de-excitation fission fragments are realized by neutron emissions, γ radiation, and then β-decays [1]. Therefore, the energy partition between two fragments plays an indispensable role in determining the multiple post-fission observables and their correlations.

Fragment excitations are caused by dissipative motion and shape distortions. Dissipation plays a significant role in the final splitting stage [2]. The shape distortion and shell effects of the fragments are important in energy partitioning [3]. The non-equilibrium non-adiabatic fission dynamics, shell effects, dynamical pairing correlations, shapes of primary fragments, and energy dependencies can be naturally described by microscopic time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) [2, 4-15]. It has been pointed out that the energy partition occurs later than particle partition [16]. In previous fission studies of 240Pu, the light fragments acquired more excitation energies than those of heavy fragments [4]. This is consistent with the observation that the light fragments emit more neutrons than heavy fragments from the fission of actinide nuclei. With increasing excitation energy, the difference in excitation energies between light and heavy fragments is reduced [4].

Experimentally, the average number of neutrons, that is, neutron multiplicities, emitted from fission fragments shows puzzling sawtooth structures depending on the fragment masses [17, 18]. This provides a unique opportunity to understand the energy sharing between two fission fragments. Conventionally, the excitation energy sharing between fission fragments is described as at the statistical equilibrium by invoking different level densities of fragments [3, 19-22]. It has been pointed out that shape-dependent density levels can better describe the partitioning of excitation energies [3]. In this approach, the slopes of the sawtooth structures are slightly underestimated [3]. Usually, different temperatures in light and heavy fragments must be adopted to reproduce neutron multiplicities [20, 21]. Sawtooth structures are also shown in the distributions of neutron excess depending on the fragment-charge number [23, 24] and angular momentum depending on the fragment masses [25].

Recently, we proposed that quantum entanglement is crucial for the appearance of sawtooth structures in the distributions of the excitation energies of fragments and subsequently neutron multiplicities [26]. Quantum entanglement enables the exchange of particles and energy between two well-separated fission fragments. This is a counter-intuitive picture but can be understood because of the non-localization of wave functions in the fast splitting process [26]. Owing to this entanglement, the energy changes associated with the particle partition were significantly reduced. The sharing of particles between two fission fragments obtained by a double particle number projection (PNP) shows a considerable spreading width [26, 27]. The associated energy partition owing to the superposition of different particle numbers can be obtained using the PNP method [26]. The distribution of fragment yields has been studied by PNP within the framework of the time-dependent generator-coordinate-method and TD-DFT [27-29]. The PNP method has also been used to study heavy ion reactions [31, 30]. In most fission models, quantum correlations or entanglement between two fission fragments are not considered. It is timely to study the energy partition between fission fragments considering the quantum entanglement between two fission fragments, in which the entanglement is persistent even when two fragments are well separated [26].

In this work, we studied the partition of the excitation energies of isotopic fission fragments of 238U, which is relevant for the production of radioactive beams from fission products after prompt neutron evaporation. For example, medium-mass neutron-rich beams are mainly produced by the fission of 238U in new-generation rare isotope beam facilities such as FRIB [32], RIBF [33], and HIAF [34]. Three new isotopes were produced in fission reactions of 238U beam in the carbon target in the newly operated FRIB [32]. In addition, the proposal of photo-fission of 238U driven by high-power e-LINAC with a convertor target is promising for producing neutron-rich beams [35]. A deeper understanding of nuclear fission is also relevant for the synthesis of superheavy elements [36], production of long-lived fission products, and next-generation energy production.

Methods

The time-dependent Hartree-Fock+BCS (TD-BCS) approach was used to describe the dynamical fission evolution beyond the saddle point. The TD-BCS equations can be derived using the BCS or canonical basis in the time-dependent Hartree-Fock-Bogoliubov method [37]. In our previous work, TD-BCS was extended to study the fission dynamics of compound nuclei [4]. The initial configuration of the fissioning nucleus was obtained using deformation-constrained Hartree-Fock+BCS calculations. We employed constrained calculations in terms of quadrupole-octupole deformations (β2, β3). The initial deformation was adopted as (β2, β3)=(2.4, 1.4) for fission evolution. It has been pointed out that evolution results are not sensitive to initial deformation [11]. For nuclear interactions, SkM* [38] and UNEDF1 [39] forces were adopted, which have been widely used for the calculation of nuclear fission barriers. The mixing-type pairing interaction [40] is adopted with strengths Vp=475 MeV and Vn=420 MeV for SkM* force, and Vp=415 MeV and Vn=375 MeV for the UNEDF1 force. The dynamical evolution was performed with the time-dependent Hartree-Fock (TDHF) solver Sky3D [41] with our modifications of the TD-BCS. The initial configurations were obtained using the SkyAX solver [42] to interface with the Sky3D.

Based on the TD-BCS solutions, the particle numbers of the fragments and fissioning nuclei are not well defined. The particle numbers in the two fragments are in a superposition state. The double PNP on the total space and partial space were applied to determine the particle numbers of the two complementary fragments.

The double projection operator is written as

The PNP on the wave functions of each fragment leads to a two-dimensional distribution of fragments in terms of (Z, N), in which the formation probability of each fragment is the expectation value of

Results

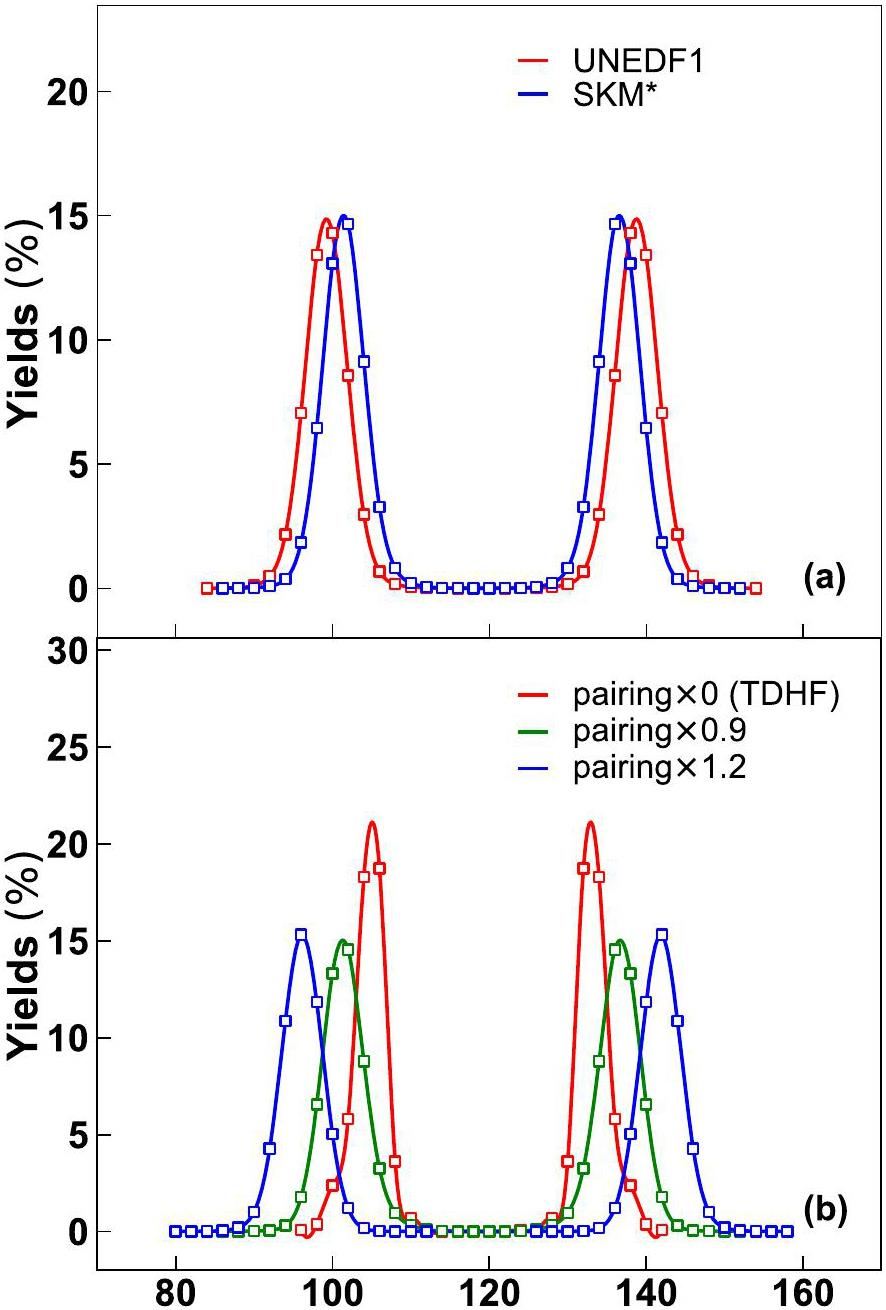

First, the distributions of the fission yields of 238U after PNP on the splitting fission event are obtained. Figure 1(a) shows the distributions of projected fission yields as a function of fragment masses calculated using SkM* and UNEDF1 forces. It can be seen that the peak is around A=136 with the SkM* force, but the peak is around A=138 with the UNEDF1 force. The peak widths were similar, and the half-widths were approximately eight particles. It is known that UNEDF1 results in slightly lower fission barriers than SkM* [39]. This could be the reason why the fission yield peak from the UNEDF1 calculations is slightly more asymmetric. Correspondingly, the total kinetic energy (TKE) was smaller with a longer scission neck. The resulting TKE of SkM* calculations is 168.9 MeV while TKE of UNEDF1 calculations is about 159.5 MeV. Note that the average experimental TKE from photofission of 238U is around 170 MeV [45].

Pairing correlations are important in describing fission probabilities [46, 47] and dynamical fission evolutions [4, 10, 48, 49]. To study the role of pairing correlations in dynamical calculations of particle partitioning between fission fragments, the distributions of fission yields after PNP are displayed with varying pairing strengths, as shown in Fig.1(b). It can be observed that the peak locations are shifted to more asymmetric fission modes with increasing pairing strengths. With TDHF calculations without pairing correlations, the peak location is approximately A=132 and close to the asymmetric S1 fission channel [50, 51]. This situation is similar to that in our previous studies on the fission of 240Pu [4]. The peak locations from calculations with pairing strengths reduced by a factor of 0.9 are close to the original results. However, the peak location is shifted to A=142 if the pairing strength increases by a factor of 1.2. It has been pointed out that a larger pairing strength results in a longer scission neck [2], which could be related to more asymmetric fission yields. Within the TDHF, the width of the PNP is smaller than that of the TD-BCS+PNP calculations. This implies that the spreading width of fission yields can be enhanced by including many-body correlation. It is known that the width of S1 channel is narrower than that of the S2 channel [50]. With increasing pairing strength, the scission neck becomes longer, and the resulting TKE becomes smaller. The TKE corresponding to pairing factors of 0.0, 0.9 and 1.2 are 174.2, 169.6 and 160.3 MeV, respectively.

The average excitation energies of fission fragments can be obtained using TD-BCS calculations without PNP. In TD-BCS, the light fragment has higher excitation energies than the heavy fragment during low-energy fission [4]. In this study, we are interested in studying the distribution of the excitation energies of all fission fragments with PNP. This is related to the intriguing sawtooth structures of the neutron multiplicities.

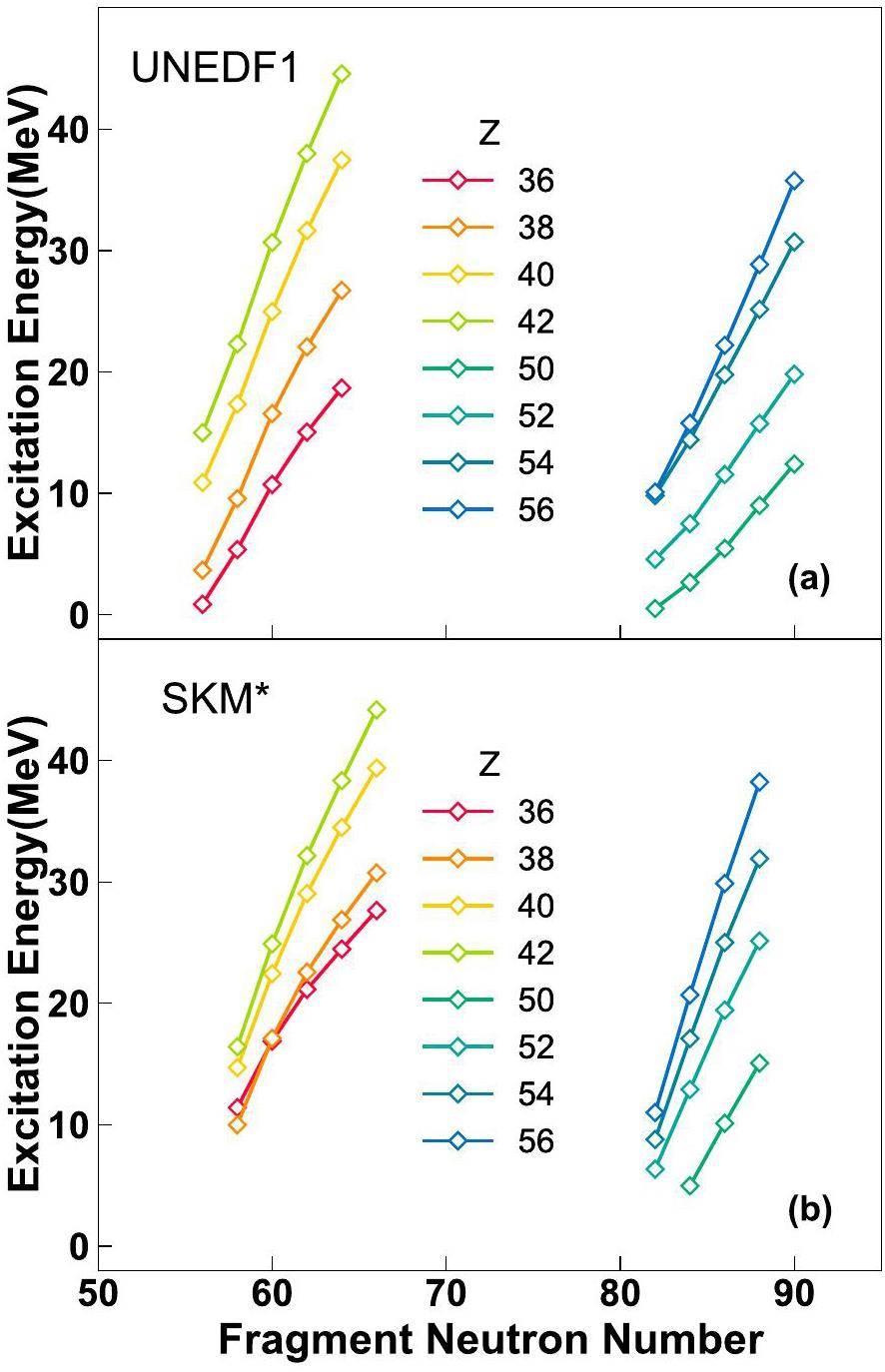

Figure 2 shows the excitation energies of different isotopic fragments. It can be observed that the UNEDF1 results are similar to the SkM* results. The results for isotopes around Z=46, that is, the symmetric fission channel with very small yields, are not shown. Usually, the average neutron multiplicities are illustrated in terms of fragment masses. In our calculations, the detailed results show that the distributions of the excitation energies of the isotopic fragments have positive slopes. This explains the origin of sawtooth structures. Generally, light fragments have higher excitation energies than those of heavy fragments. However, this was not the case for the two complementary fragments. For the same isotopic fragments, heavier fragments have higher excitation energies. It should be noted that to obtain realistic two-dimensional distributions of fission yields and excitation energies, fluctuation effects in the fission process should be considered, which can significantly alleviate the slopes of sawtooth structures [26].

As shown in Fig. 2, the excitation energies of the isotopic fragments increase as the neutron number increases, which has significant implications. Currently, rare isotope beam facilities [32, 33] mainly rely on the acceleration of fission fragments from 238U. In particular, Coulomb excitation induced fission of 238U with a high-Z target is advantageous for the production of neutron-rich beams [52]. Reliable estimation of the beam intensity is a practical issue. Beam intensity calculations are conventionally based on the code LISE++ [53], which relies on empirical fission yields. It is difficult to describe the intensities of light and heavy fragments [33]. In our calculations, heavier isotopes had higher excitation energies, resulting in more neutron evaporation. This implies that the production of neutron-rich rare isotope beams is suppressed. The partition of excitation energies would be changed at high energies when sawtooth structures are also washed out [54].

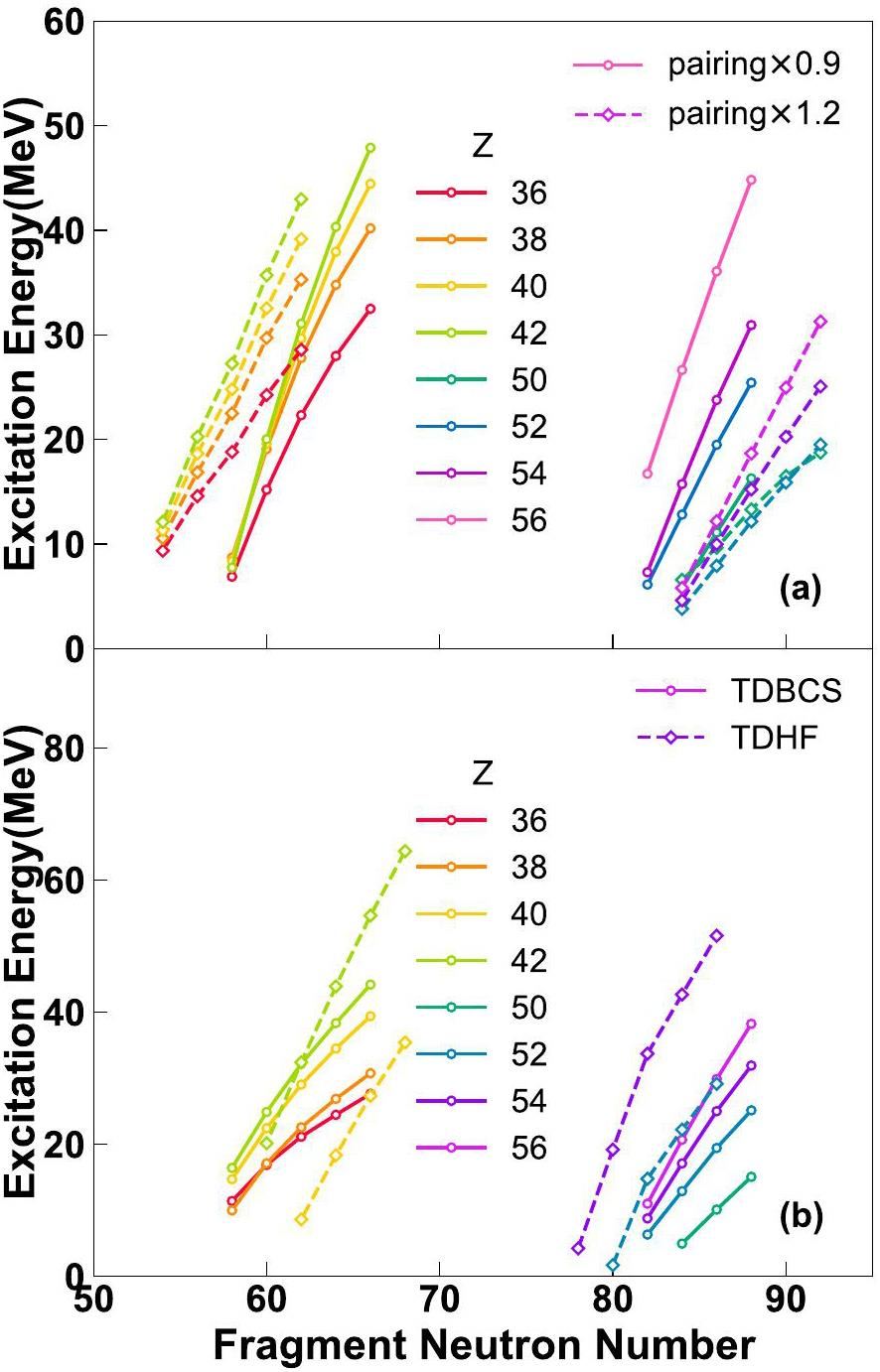

Figure 3 shows the excitation energies of the fission fragments with varying pairing strengths. With increasing pairing strength, the fission yield peaks are slightly more asymmetric, as shown in Fig. 1(b). It can be seen that the maximum excitation energies of the fragments are generally reduced with increasing pairing strength. In particular, the excitation energies of the heavy fragments, except for the Z=50 shell, decreased significantly with increasing pairings. In addition, the slopes of the excitation energies of the light fragments were reduced with increasing pairing strengths. The slopes were overestimated in our approach, which can be alleviated by fluctuation effects [26]. Figure 3(b) shows the excitation energies obtained from the TD-BCS+PNP and TDHF+PNP calculations. It can be observed that the excitation energies and their slopes from TDHF+PNP are too large, corresponding to the narrow S1 channel. Our results indicate that many-body correlations, in addition to pairing correlations, might be useful to obtain reasonable excitation energies of fragments, as well as to alleviate the associated slopes. In this respect, fluctuations can be considered an effective treatment for high-order correlations. Note that the main objective of this work is to study the energy partition between two well-separated fission fragments, while shell effects and shape distortions of fragments are important in the energy sharing mechanism before separation. Nevertheless, quantitatively reproducing the full distributions of fission yields and neutron multiplicities microscopically is beyond the scope of the present work.

Summary

The excitation energies of the isotopic fission fragments from 238U were calculated using the microscopic TD-BCS plus PNP method for a deeper understanding of nuclear fission. The energy partition was calculated for two well-separated but entangled fragments after the dynamical evolution. This is different from most fission models, which invoke an explicit statistical partition of excitation energies between fragments. The dependencies of the energy partition on different Skyrme forces and pairing strengths were studied. With increasing pairing strength, the fission yield peak shifts to a slightly more asymmetric fission channel. In TDHF calculations without pairings, the width of the fission yields is rather narrow, and its peak is close to the S1 fission channel. The excitation energies obtained for the isotopic fission fragments explain the origin of the sawtooth structures. Furthermore, pairing correlations play a significant role in the partitioning of energies between the fragments. The slope of the excitation energies of the light fragments decreases with increasing pairing strengths. For heavy fragments, the excitation energies of the heavy fragments, except for the Z=50 shell, decreased significantly with increasing pairing correlations. The excitation energies based on TDHF+PNP were too large and the associated slopes were very steep. Our results indicated that many-body correlations or fluctuations are essential for obtaining reasonable excitation energies. It should be noted that the excitation energy partition and consequently neutron evaporation have practical implications for estimating beam intensities in rare-isotope beam facilities.

Future of nuclear fission theory

. J. Phys. G Nucl. Part. Phys. 47,Energy and pairing dependence of dissipation in real-time fission dynamics

. Phys. Rev. C 104,Excitation energy partition in fission

. Phys. Lett. B 803,Fission dynamics of compound nuclei: Pairing versus fluctuations

. Phys. Rev. C 103,Microscopic calculation of nuclear dissipation

. Phys. Rev. C 13, 209 (1976). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.13.209Dynamics of induced fission

. Phys. Rev. C 17, 1098 (1978). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.17.1098Time-dependent density-functional description of nuclear dynamics

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 88,Fission dynamics within time-dependent Hartree-Fock: Deformation-induced fission

. Phys. Rev. C 92,Timescales of quantum equilibration, dissipation and fluctuation in nuclear collisions

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124,Induced fission of 240Pu within a real-time microscopic framework

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116,Fission dynamics of 240Pu from saddle to scission and beyond

. Phys. Rev. C 100,Impact of pear-shaped fission fragments on mass-asymmetric fission in actinides

. Nature 564, 382(2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0780-0Formation and dynamics of fission fragments

. Phys. Rev. C 89,Microscopic phase-space exploration modeling of 258Fm spontaneous fission

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118,Implementation of nuclear time-dependent density-functional theory and its application to the nuclear isovector electric dipole resonance

, Phys. Rev. C 102,Fission-fragment excitation energy sharing beyond scission

, Phys. Rev. C 102,Simultaneous investigation of fission fragments and neutrons in 252Cf(sf)

, Nucl. Phys. A 490, 307(1988). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(88)90508-8Multiplicity and energy of neutrons from 235U(nth, f) fission fragments

, Nucl. Phys. A 632, 540(1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(98)00008-6Final excitation energy of fission fragments

. Phys. Rev. C 83,Energy partition in 235U fission reaction induced by thermal neutron

, Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 21,Connection of four-dimensional Langevin model and Hauser-Feshbach theory to describe statistical decay of fission fragments, J

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 61(1), 84(2024). https://doi.org/10.1080/00223131.2023.2273470Modelling of the total excitation energy partition including fragment deformation and excitation energies at scission

, J. Phys. G 39Insight into excitation energy and structure effects in fission from isotopic information in fission yields

, Phys. Rev. C 99,Anomalies in the Charge Yields of Fission Fragments from the 238U(n, f) Reaction

, Phys. Rev. Lett. 118,Angular momentum generation in nuclear fission

. Nature (London) 590, 566(2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03304-wQuantum entanglement in nuclear fission

. Phys. Lett. B 861,Number of particles in fission fragments

, Phys. Rev. C 100,Microscopic calculation of fission product yields with particle-number projection

. Phys. Rev. C 103,Projection of good quantum numbers for reaction fragments

. Phys. Rev. C 100,Microscopic predictions for the production of neutron-rich nuclei in the reaction 176Yb + 176Yb

, Phys. Rev. C 101,Particle-number projection method in time-dependent Hartree-Fock theory: Properties of reaction products

. Phys. Rev. C 90,Acceleration of uranium beam to record power of 10.4 kW and observation of new isotopes at Facility for Rare Isotope Beams

. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 27,Observation of New Neutron-rich Isotopes among Fission Fragments from In-flight Fission of 345 MeV/nucleon 238U: Search for New Isotopes Conducted Concurrently with Decay Measurement Campaigns

. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 87,Status of the high-intensity heavy-ion accelerator facility in China

. AAPPS Bull 32, 35 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43673-022-00064-1Survival probabilities of compound superheavy nuclei towards element 119

. Phys. Lett. B. 858,Canonical-basis time-dependent Hartree-Fock-Bogoliubov theory and linear-response calculations

. Phys. Rev. C 82,Towards a better parametrisation of Skyrme-like effective forces: A Critical study of the SkM force

. Nucl. Phys. A 386, 79 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(82)90403-1Nuclear energy density optimization: Large deformations

. Phys. Rev. C 85,Nuclear ground-state properties from mean-field calculations

. Eur. Phys. J. A 15, 21(2002). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2001-10218-8The TDHF code Sky3D

. Comp. Phys. Comm. 185, 2195(2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2014.04.008The Axial Hartree-Fock+ BCS Code SkyAx

, Comput. Phys. Commun. 258,Particle number projection with effective forces

. Nucl. Phys. A 696, 467(2001). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(01)01219-2Symmetry restoration in mean-field approaches

. J. Phys. G 48,Fragment characteristics from fission of 238U and 234U induced by 6.5-9.0 MeV bremsstrahlung

. Nucl. Phys. A 851, 1 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2010.12.012Pairing-induced speedup of nuclear spontaneous fission

. Phys. Rev. C 90,Sensitivity impacts owing to the variations in the type of zero-range pairing forces on the fission properties using the density functional theory

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 62 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01422-4Role of pairing correlations in the fission process

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Pairing effects on the fragment mass distribution of Th, U, Pu, and Cm isotopes

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 173 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01316-xNuclear scission

. Phys. Rep. 197, 167 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-1573(90)90114-HMass yield distributions and fission modes in photofission of 238U below 20 MeV

. Phys. Rev. C 91,Neutron-rich fragments produced by in-flight fission of 238U

. Phys. Rev. C 99,LISE++: Radioactive beam production with in-flight separators

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. B 266, 4657 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2008.05.110Characterization of the scission point from fission-fragment velocities

. Phys. Rev. C 92,Jun-Chen Pei is an editorial board member for Nuclear Science and Techniques and was not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.