Introduction

The Back-n White Neutron Facility at the China Spallation Neutron Source (CSNS) in Dongguan, China, is a state-of-the-art platform for advanced neutron research[1]. As the first pulsed neutron source in the country, backscattering techniques are employed to generate a broad spectrum of white neutrons. These neutrons, which are produced by bombarding a tungsten target with high-energy protons, cover a wide energy range and are particularly useful for nuclear physics, data measurement, and engineering applications. Equipped with sophisticated detectors and instrumentation, this facility enables precise experiments that provide valuable insights into nuclear reactions. First, these data provide a foundational resource for the development and refinement of nuclear models, which are essential for advancing our understanding of nuclear reactions and processes. By offering precise measurements, the data contribute to improved accuracy in nuclear reaction cross-sections, which are critical inputs for nuclear reactor design, radiation safety assessments, and the development of new nuclear materials. Moreover, the data have broad utility beyond the immediate research applications of Back-n. They can be leveraged by the wider scientific community to explore novel nuclear phenomena, thereby opening opportunities for new collaborations and interdisciplinary studies. For instance, these data may aid in astrophysical research, where accurate neutron capture rates are crucial for modeling stellar nucleosynthesis. In addition to their scientific value, these data also have potential applications in medical physics, particularly in the design of radiation therapies and diagnostic tools. By facilitating a deeper understanding of neutron interactions with various isotopes, the data can help optimize these technologies for better patient outcomes. Overall, the nuclear data from Back-n serves as a versatile tool that not only supports current research initiatives but also paves the way for future innovations and collaborations across multiple fields.

| Specifications Table | |

|---|---|

| Subject | Nuclear physics and nuclear data |

| Specific subject area | Data acquisition |

| Data format | Raw/Analyzed |

| Type of data | Detector Waveform Data |

| How data were acquired | Measurements were performed using different detector system |

| Parameters for data collection | The raw waveform signal of the detector pulses |

| Description of data collection | Data were collected by saving list-mode detector data during acquisitions. |

| Data collection | The data were collected from Back-n detectors using the general-purpose readout electronics. |

| Data source location | Institution: Institute of High Energy Physic |

| Country: China | |

| Data accessibility | Repository name: Science Data Bank |

| Data identification number: https://cstr.cn/31253.11.sciencedb.j00186.00600 | |

| Direct URL to data: https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.j00186.00600 | |

| Related research article | Ruirui F, et al., 2023. RDTM, 7(2): 171-191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41605-022-00379-5 |

| Chen Y, et al., 2023. Physics Letters B, 839: 137832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2023.137832 | |

| Wang Q, et al., 2018. Review of Scientific Instruments, 89(1): 013511. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5006346 | |

As the first high-performance white neutron source in China, Back-n provides an unprecedented platform for neutron-induced nuclear data measurements [2]. Its broad neutron spectrum allows precise measurements of neutron-induced reactions, which are essential for developing and validating nuclear models. These measurements refine the nuclear reaction cross-sections, which are vital for reactor design, radiation shielding, and safety assessments. The facility also facilitates the study of neutron interactions with various isotopes, enhancing our understanding of nuclear processes and aiding the development of new materials for nuclear energy. Additionally, its high-quality nuclear data benefit fields such as astrophysics, where accurate neutron capture rates are crucial for modeling stellar nucleosynthesis. Overall, the Back-n facility is a key resource for advancing nuclear data research, supporting efforts to harness nuclear technology safely and efficiently across academic and industrial sectors.

The Back-n facility boasts a comprehensive and advanced detector system, including a Light Particle Detector Array (LPDA), multi-layer Fission Ionization Chamber Detector (FIXM), and gamma-ray detectors such as C6D6. Recently, the facility has incorporated the world’s leading Multi-purpose Time Projection Chamber (MTPC) and Gamma Total Absorption Facility (GTAF) into its operations. These additions are expected to yield a wealth of high-precision nuclear data measurements [3].

Most detector systems rely on a high-precision waveform sampling electronic system, known as a general-purpose electronic system. The data collected by these systems are acquired through a Data Acquisition (DAQ) process and stored in the disk array system of the CSNS Computing Center’s cluster. Users utilize ROOT software to convert this binary data into graphical formats, such as TTrees and one-dimensional or two-dimensional histograms. After performing the necessary R-matrix fits, the data provide critical nuclear-related information, which is then published as the measured nuclear data.

This paper describes a typical data analysis process based on the Back-n facility, illustrating the methodologies and instrumentation used in data measurement and propagation in Back-n experiments.

Experimental setup and Measuring principle

In white neutron experiments, the measurement of the flight time is of utmost importance. The experiment utilizes neutrons or secondary particles produced by neutrons interacting with the target as the timing reference and obtains the reaction cross sections of neutrons of different energies. For Back-n, multiple experiments with different reaction types were conducted [4].

In this study, the total cross-section measurement experiment was taken as an example to illustrate the experimental principle and method. The neutron-induced total cross-section refers to the probability of a nuclear reaction occurring when a neutron strikes the sample. Transmission measurement is the primary method for measuring the neutron-induced total cross-section, and the transmission rate T was obtained from the neutron counts, N and N0, measured in the sample-in and sample-out using Eq. 1.

The neutron detector used was a FIXM (multi-layer fission chamber) [5]. It employs multiple layers of fissile materials as target plates to detect the fission fragment signals in the gas ionization chamber. The signals were amplified by the MSI-8 preamplifier from the Mesytec company and then sent to general-purpose electronics for waveform acquisition.

General-purpose readout electronics

For the Back-n facility, the neutron nuclear data are measured by general-purpose readout electronics together with the neutron energy. In the implementation, the neutron nuclear data can be deduced by acquiring the detector signal precisely, while the neutron energy can be obtained by measuring the time of flight (TOF) of neutrons. The TOF is defined as the time difference between the start and stop signals, where the start signal is designated as T0, which represents the exact time of the proton beam bombarding the tungsten target of the CSNS. Thus, there are two critical measurements for the readout electronics: the TOF and waveform.

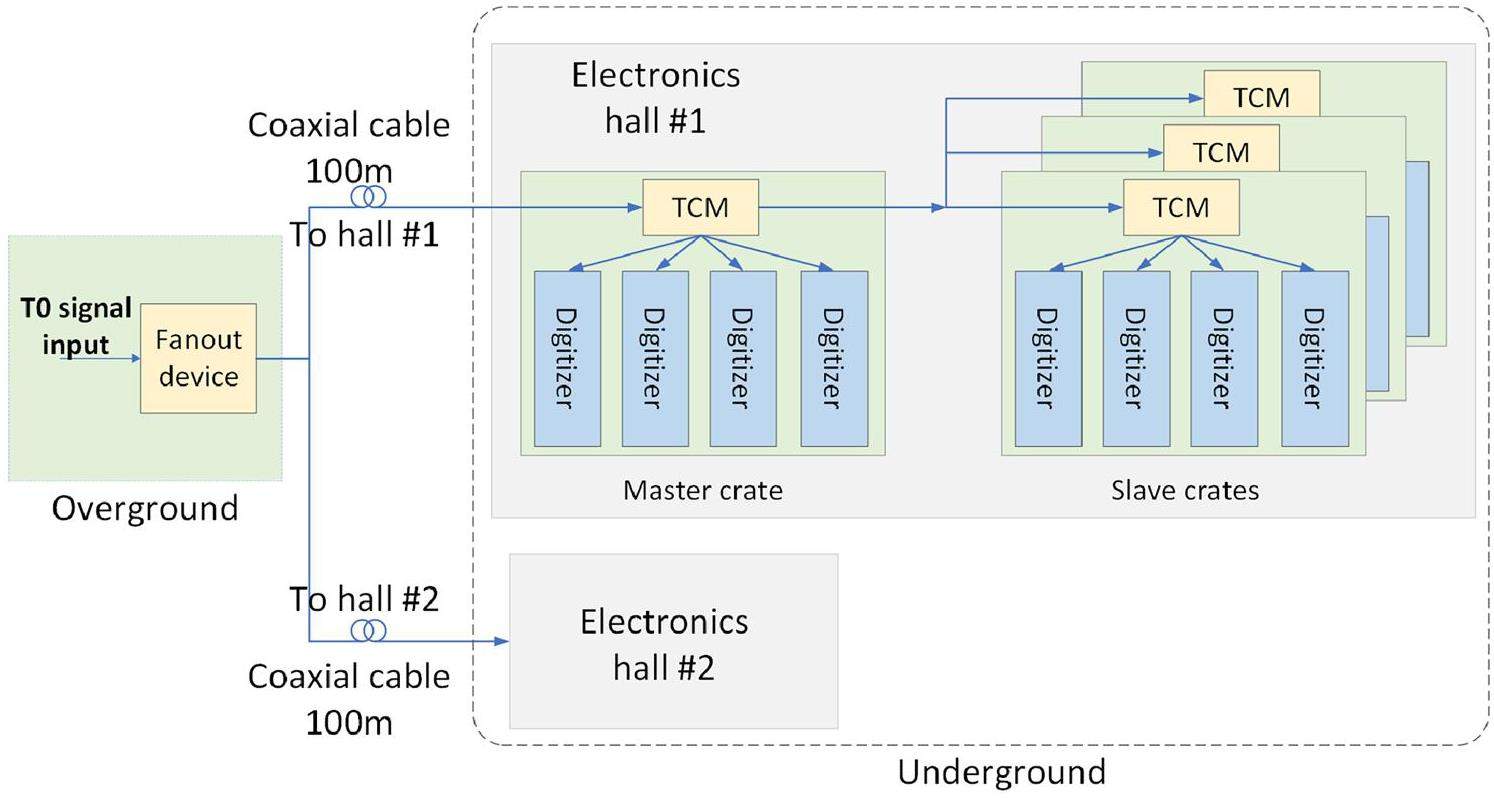

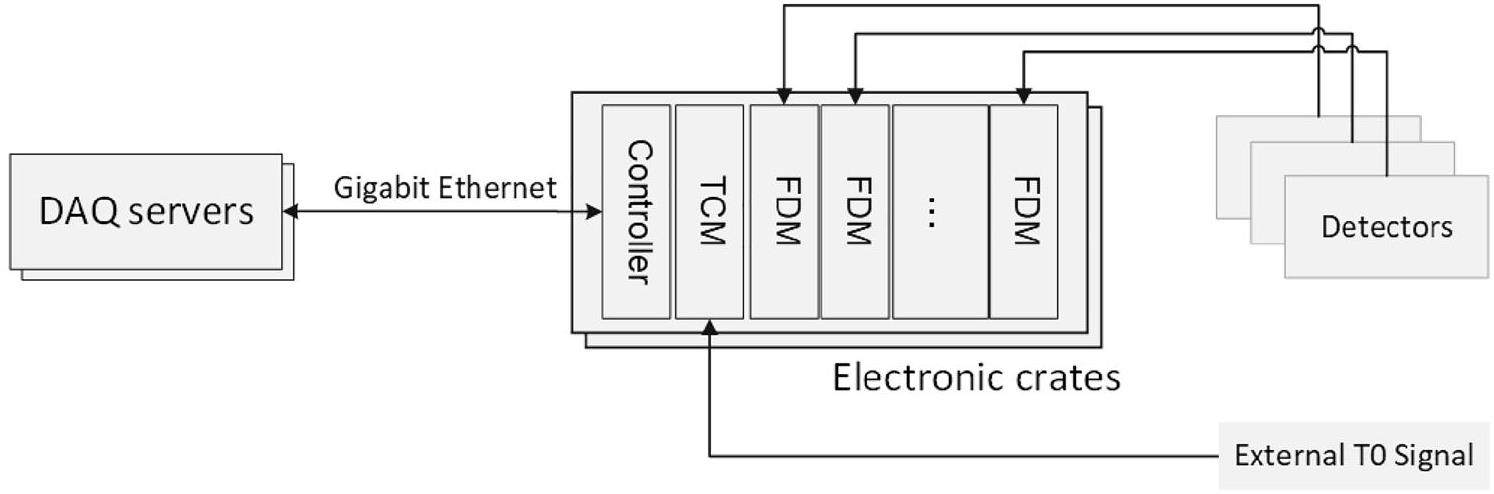

To precisely measure the neutron TOF, the T0 signal, designated as the start time, must be distributed synchronously to each measurement point. Figure 1 shows the structure of the T0 signal fanning out for Back-n. There is a fanning out device on the ground that receives the FCT signal from the beam monitor system and then fans out to the readout electronics placed in the two underground experiment halls through two long distance coaxial cables with lengths of approximately 100 m. There are several electronic crates in both halls, and within each of the crates, there are several high-speed digitizers and a timing module named TCM (trigger and clock module). The T0 signal is first distributed to the TCM module installed in the master crate and then fanned out to the TCM modules installed in the slave crates. The distribution path between the master and each slave crate was set to the same length, which eliminated the T0 propagation skew.

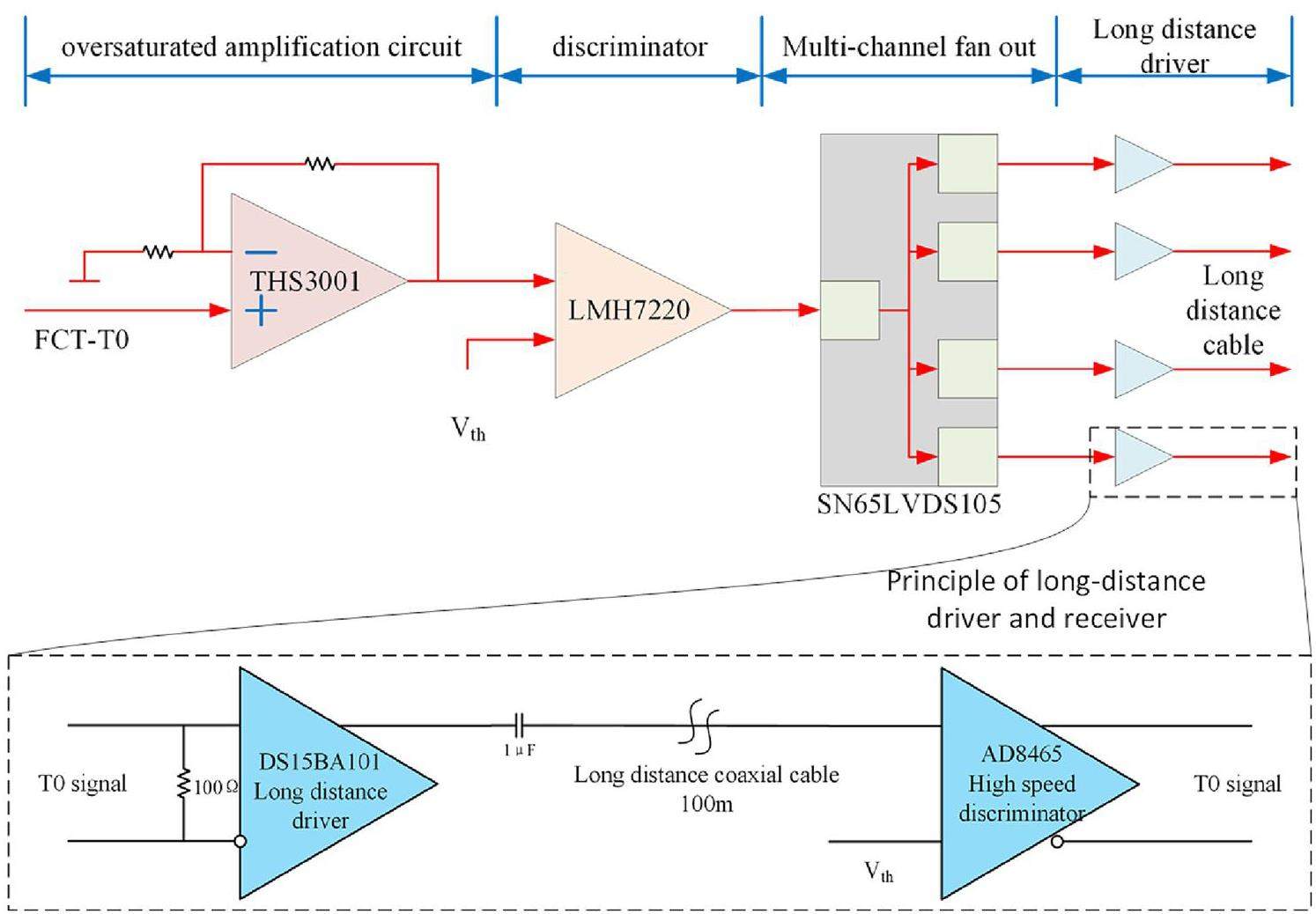

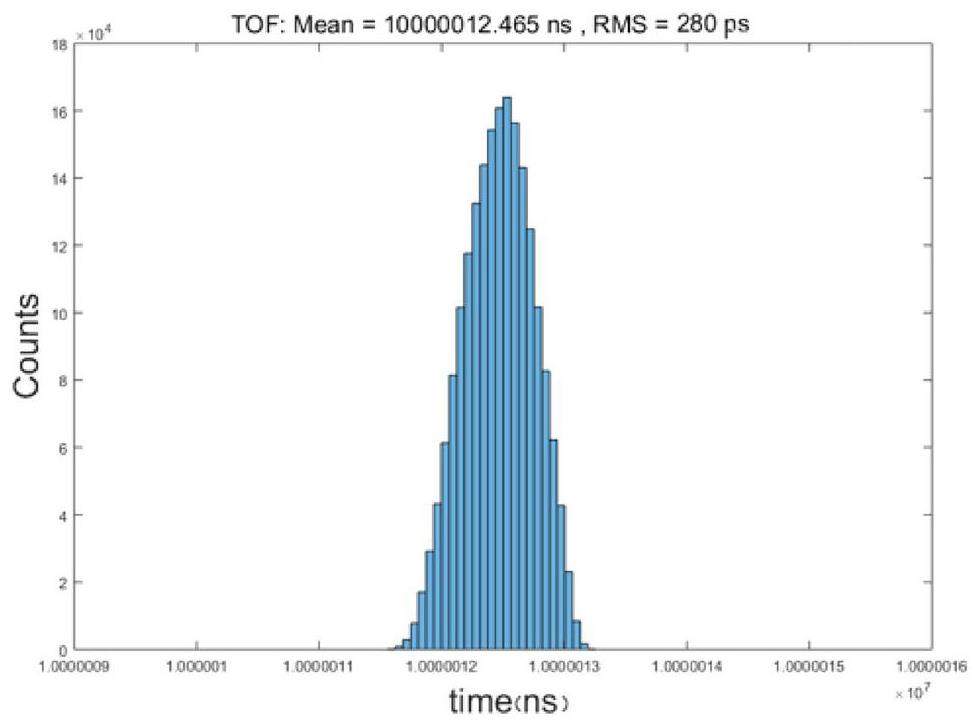

T0 jitter is the primary factor degrading the precision of the TOF measurement. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the fan-out device on the ground uses an oversaturated circuit to amplify the FCT T0 signal to obtain a new T0 signal with a very fast leading edge which is better for increasing the timing accuracy. Besides, long distance cable can worsen the jitter of transmitted signal because of the limited bandwidth. The longer the distance, the worse the deterioration. To reduce the influence of long-distance transmission, the fanning out device uses a long-distance driver to pre-emphasize the high frequency part of the T0 signal to improve the signal quality after being transmitted over 100 m long distance in order to make the received T0 signal has good enough leading edge, so as to ensure the accuracy of timing. Finally, a FPGA (field programmable gate array) based time digital convertor [6] is used to measure the TOF, which can achieve good performance of 280 ps (RMS) as shown in Fig. 3.

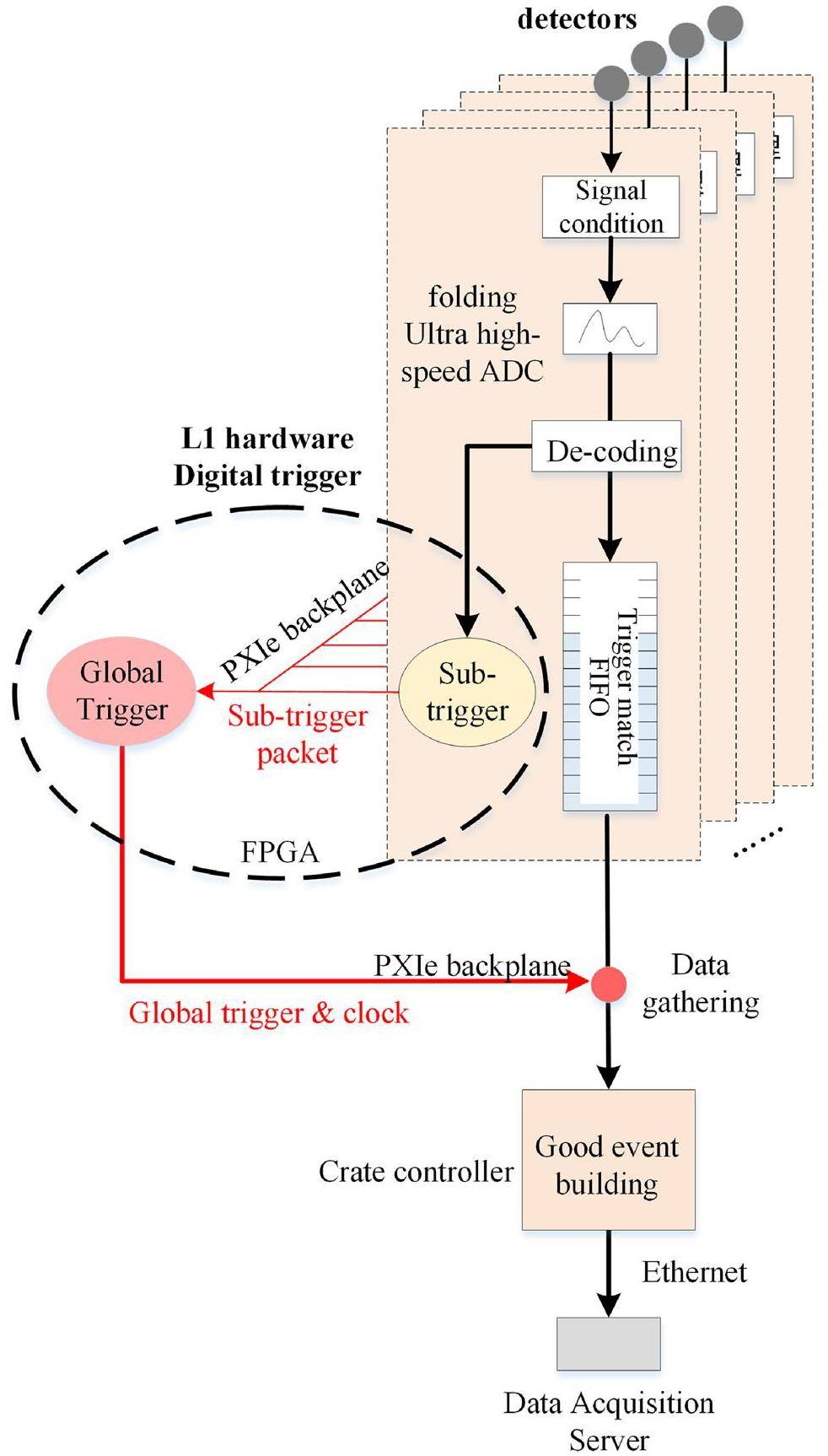

To measure the waveform of detector signals precisely, Back-n proposed an innovative full hardware digital trigger method based on high speed waveform digitization. Figure 4 shows the principle of a digital trigger [7]. On the top side, the signal from the neutron detector is fed into the signal condition module to generate signals that are compatible with the ultra high-speed digitizer [8, 9]. With the help of the folding structure of the analog digital converter, a fully digitized waveform of the detector signal was obtained with very good magnitude and time resolution. The sampling rate can reach up to 1 GSa/s, while the resolution can be 12 bits. The L1 hardware digital algorithm is executed on the FPGA. On each digitizer local FPGA, the digitizing data stream is divided into two branches in parallel: one is fed into the trigger match FIFO waiting for the global trigger, and the other is fed into the sub-trigger processing module simultaneously. In the L1 hardware trigger structure, one master global trigger module exists, which receives all sub-trigger packet from all local trigger modules on each digitizer to generate the global trigger signal based on specific algorithm to indicate the valid good event occurs. This global trigger signal should be fanned out to each trigger match FIFO(First In First Out) so that digitizer can readout the correct data corresponding to this good event. After being built, good event data is finally transmitted to the DAQ server through Ethernet.

The general-purpose readout electronics hardware comprises three types of modular components: FDM, TCM and Signal Conditioning Modules (SCMs). These modules can be flexibly configured according to the experimental requirements and integrated into a PXIe chassis, as shown in Fig. 5.

Data Acquisition and Records

Overview

Several detector systems, each designed for specific functions, were established at the Back-n facility. Typically, only one detector system is in operation at a time. Additionally, the experimental halls ES1 and ES2 at Back-n are not typically used simultaneously. Therefore, The Data Acquisition (DAQ) system is designed to support a single active detector system at a time. All detector systems are build on the same electronics platform.

An overview of the electronics and DAQ system is shown in Fig 6. The controller located in the NI PXIe crate is a computer with an x86 architecture running the Linux OS. It reads data from several FDMs (Field Digitizer Modules) and a TCM (Trigger and Clock Module) through the PXIe backplane. Data were transferred to the DAQ server through the Gigabit Ethernet.

The pulsed neutron source beam strikes the target at a frequency of 25 Hz, generating neutron bunches that are inputted to the detector at the same frequency, producing corresponding T0 signals. The T0 signal is fed into the electronic module, which uses this signal to tag the data with a T0_ID label (an 8-bits integer). Multiple readout processes are running on PXIe controller. Each process reads data from a single electronic module. It establishes a TCP/IP connection with DAQ data flow, transferring data fragments to DAQ servers.

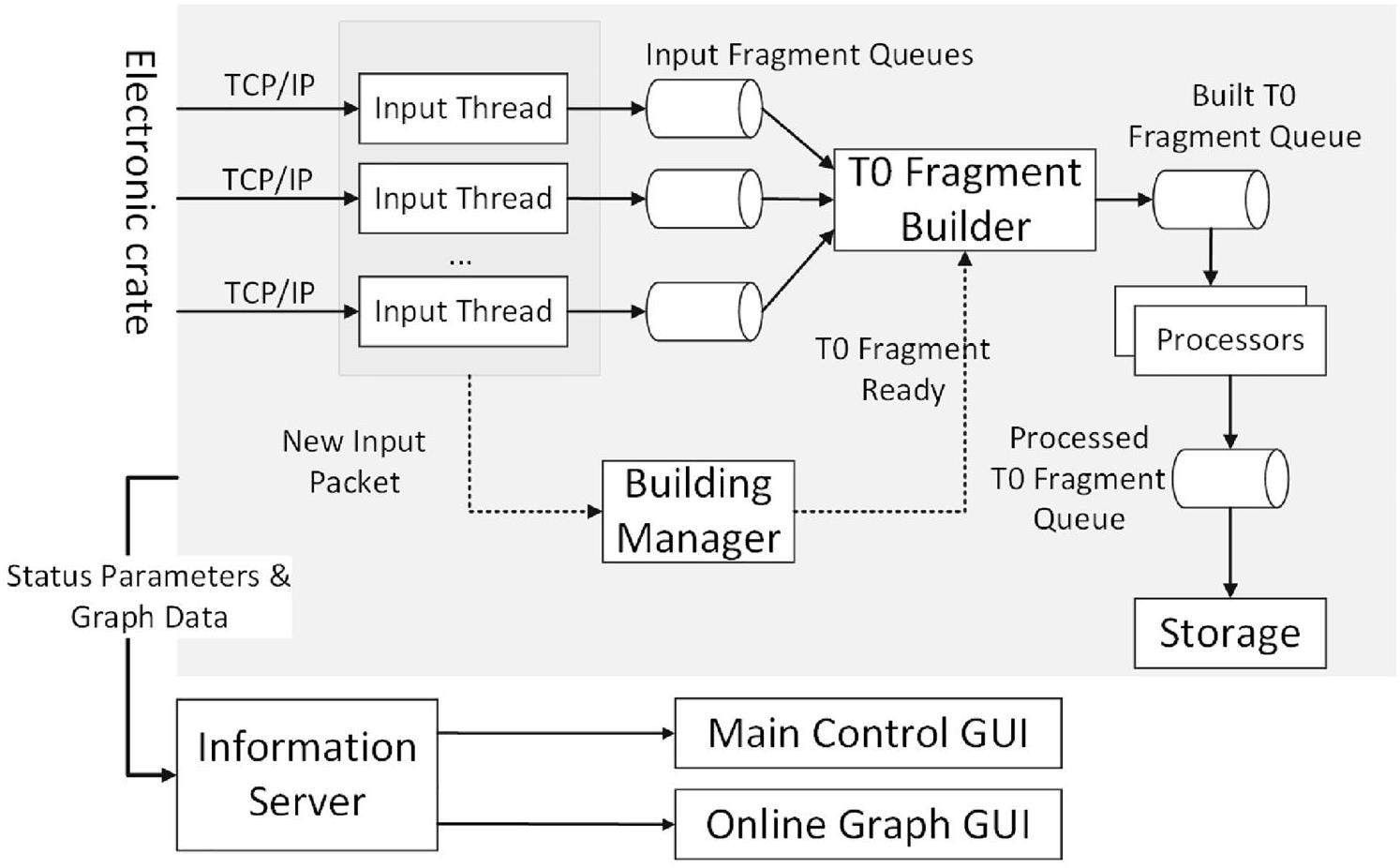

The design of the software data flow running on the DAQ server is shown in Fig. 7. When an input thread receives a data fragment, it immediately places the fragment in the corresponding input queue and notifies the building manager. Once the building manager determines that all the data fragments associated with a specific T0_ID are ready, it triggers the T0 fragment builder to initiate a T0-fragment-build task. The T0 fragment builder aggregates all the data fragments with the same T0_ID to create a complete T0 fragment. These T0 fragments were then assigned to processors for analysis. Finally, all T0 fragments were collected using the data storage thread and written to the disk.

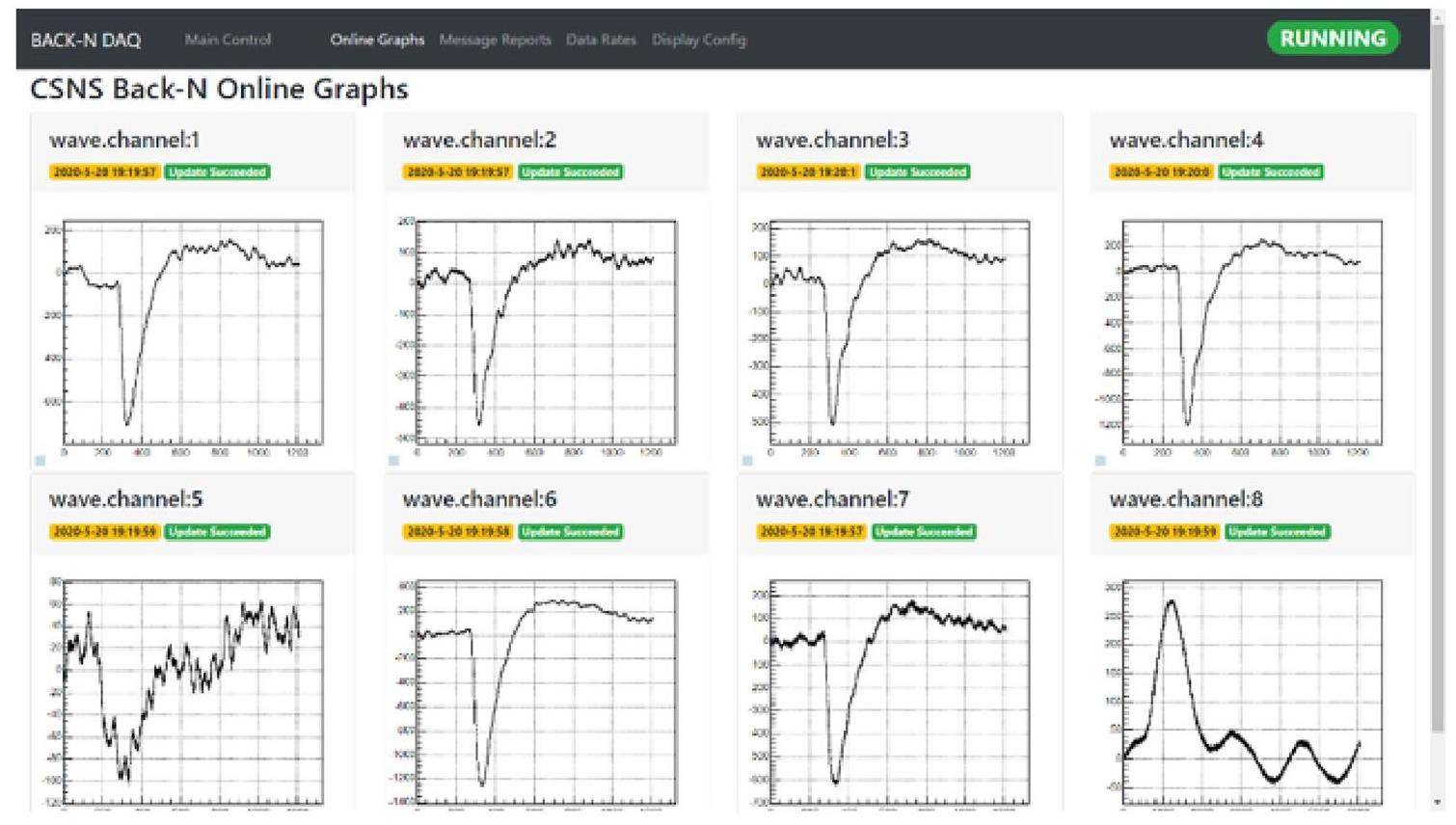

Two 4U DAQ servers, each equipped with 56 CPU cores, were deployed under the Back-n beamline. The computational capacity of a single server is sufficient to satisfy the DAQ and online processing requirements, whereas the second server serves as a hot backup for redundancy and reliability. The Back-n DAQ system's online processing, performance (Fig. 8), control (Fig. 9) and monitoring (Fig. 10) are presented below.

Online Processing

The waveform data produced by each neutron bunch were assembled as T0 fragments using DAQ software. T0 fragments were rapidly analyzed online for quality monitoring.

The online processing software is designed with a modular architecture, allowing the dynamic loading of data processing algorithms. This flexibility enables different detectors to customize their data processing pipelines according to their specific requirements. The fundamental unit of online data processing is the T0 fragment, which contains all signal data corresponding to a single neutron bunch. The processing framework retrieves T0 data packets from the assembly queue and processes them in a data-driven manner, ensuring an efficient and timely analysis. This supports the publication and real-time display of ROOT-format histograms, historical trends, and waveform data. Additionally, some common online data processing algorithms, including waveform peak finding, time-of-flight spectra analysis, charge spectra analysis, and waveform sampling, were provided as universal functions for all back-n experiments.

The entire online data flow was executed on a single server. Data are processed in the pipeline from readout to storage. Fast analysis of the T0 fragments was performed using multiple threads.

Run Control and Monitoring

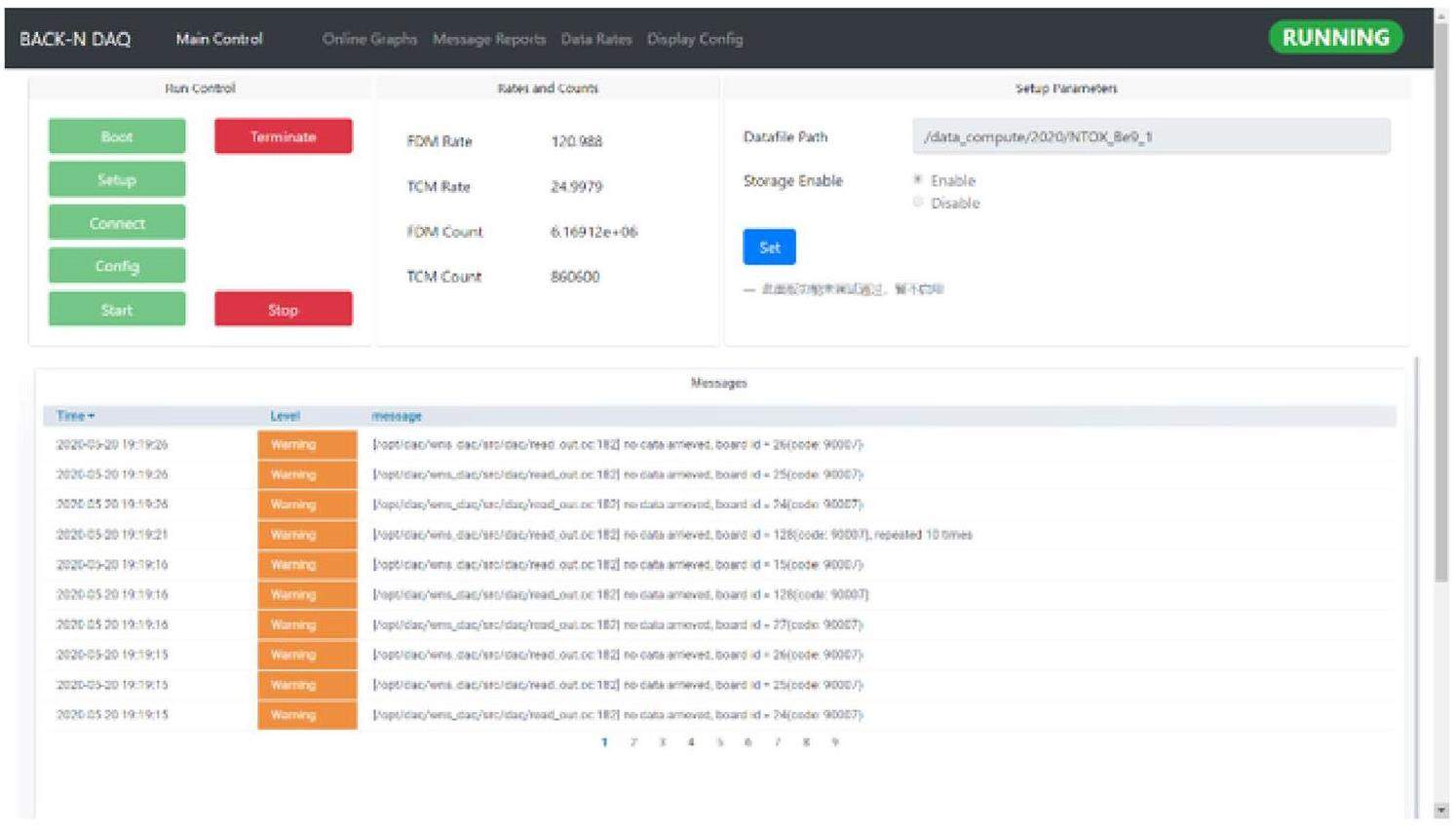

The user interface of the DAQ software is web-based and consists of two main components: the run control module and online computation results display module.

As shown in Fig. 9, the run control module provides essential functionalities, including start/stop control, modification of operational parameters, real-time display of various count rates, and error message notifications. As shown in Fig. 10, the online computation results display module retrieves and visualizes the online computation results (in ROOT format) from the information sharing service. It leverages the JSROOT [10] library to enable the dynamic rendering of ROOT graphics directly within the web interface.

DAQ Performance

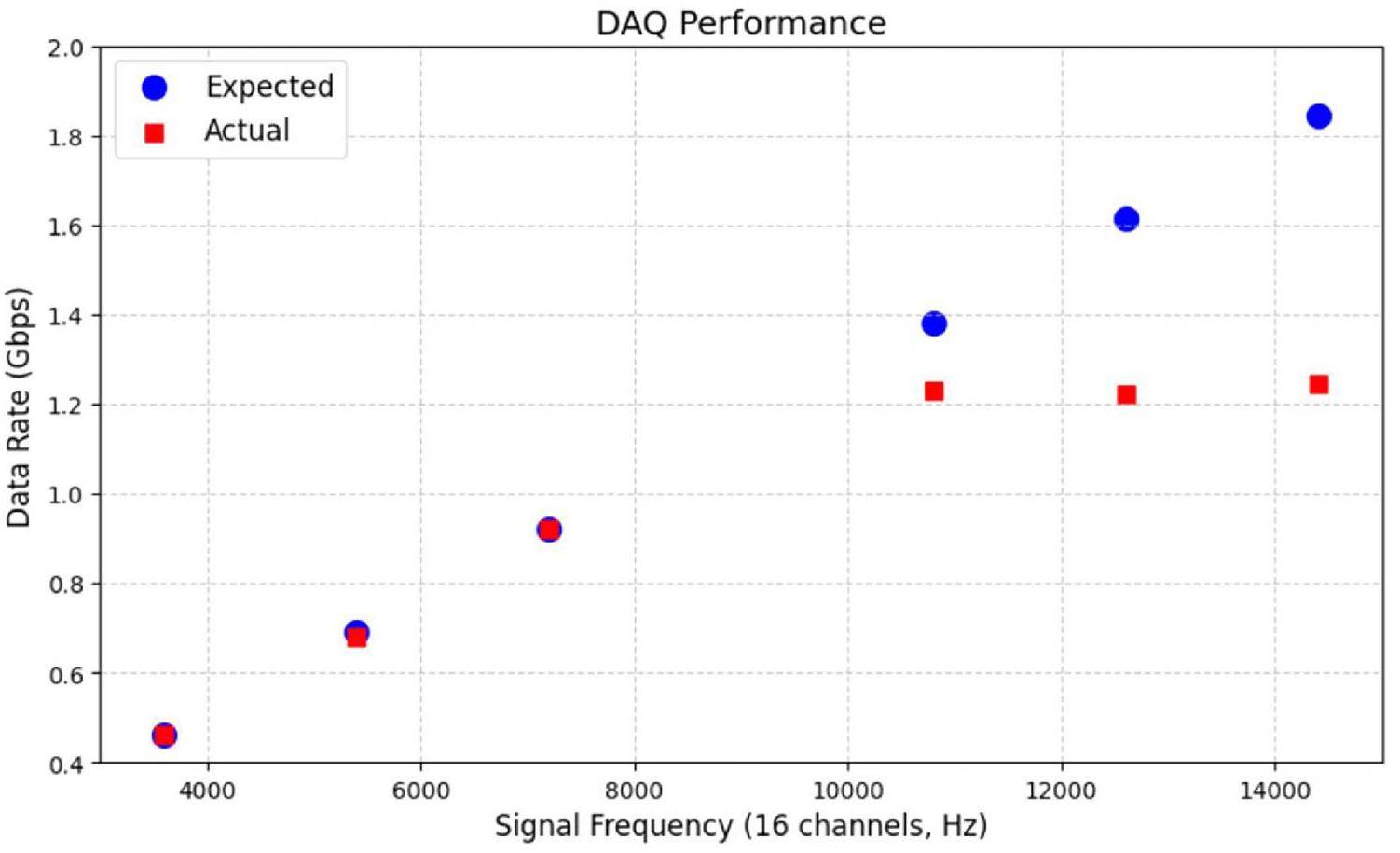

The performance test involved two electronic chassises, each equipped with a controller connected via Gigabit Ethernet, while the data acquisition (DAQ) server featured a 10-Gigabit uplink. To evaluate the transmission performance of the DAQ system and the associated electronics, a signal generator was used to simulate the detector signals and feed them into the electronic components. The test setup maintained a fixed 8,000 sampling points per channel, across a total of 16 channels. During the experiment, the frequency of the signal generator was varied to change the data rate, while keeping the number of sampling points constant. The expected data rate was calculated as the product of the number of sampling points and anticipated signal rate.

The results, illustrated in Fig. 8, indicate that the system’s data acquisition rate increases linearly with the signal rate, reaching a maximum around 10 kHz. The DAQ performance is approximately 1.2 Gbps.

The information sharing service operates as an independent process, storing online computation results in memory. Based on the summarized requirements of back-n experiments, the online computation results can be categorized into three types: histograms, historical curves, and sampled waveforms. To facilitate efficient data access and sharing, the information sharing module provides an interface with the following functionalities:

1. Serialize the ROOT-type computation results (histograms, historical curves, and two-dimensional scatter plots) and store them in the information service.

2. Retrieve result data from the information service, deserialize it, and reconstruct it into the corresponding ROOT type.

Recommended repositories to store and find data

National High Energy Physics Science Data Center

The storage, computing, and sharing of white neutron beam data were supported by the National High Energy Physics Science Data Center (NHEPDC), one of China’s 20 national scientific data centers. Compared to the Beijing Data Center and Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area Branch, NHEPDC focuses on the integration and sharing of data resources, software tools, and data analysis techniques in the fields of high-energy physics, neutron science, photon science, astrophysics, and interdisciplinary research. Currently, NHEPDC manages a total data volume of 37.55 PB and serves more than 4000 users from hundreds of institutions worldwide, with annual data access volumes reaching several hundred PB. Furthermore, through long-term cooperation with the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), NHEPDC has established itself as a core node within the international high-energy physics data grid.

Storage system

For the storage of white neutron beam data, the NHEPDC provides long-term preservation, offers file system access interfaces for offline data analysis tasks, and facilitates cross-domain data sharing services for remote users. The data are stored within a three-tier hierarchical storage system, comprising experimental station disk storage, central disk storage, and central tape storage. The data from the back-n experiments are first saved to the experimental station storage, and then the data transmission system moves the data to the central disk and tape storage. The central disk and tape storage facilities were provided by the NHEPDC, Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area Branch. Central disk storage primarily employs the Lustre distributed file system, which enables linear scalability for read/write throughput. Raw data are retained for 1–2 years according to the data policy, allowing users to conduct large-scale data analysis and remote access during this period. The data were archived in tape libraries for long-term preservation. The hierarchical storage management system EOSCTA [11] enables transparent data transfer and access across multiple media, including disks and tapes. Data are archived daily and transferred from the central disk storage to the EOS-distributed file system. CTA management software then archives the data for tape storage. When a user initiates an access request through a data management system, the backend uses metadata to locate the physical storage position of the data. If the data reside in the central disk storage, they can be accessed directly. If the data are stored in the central tape storage, the CTA management software initiates a process to restore the data to the EOS system and transfer it to the corresponding location within the central disk storage for user access and manipulation.

Data management system

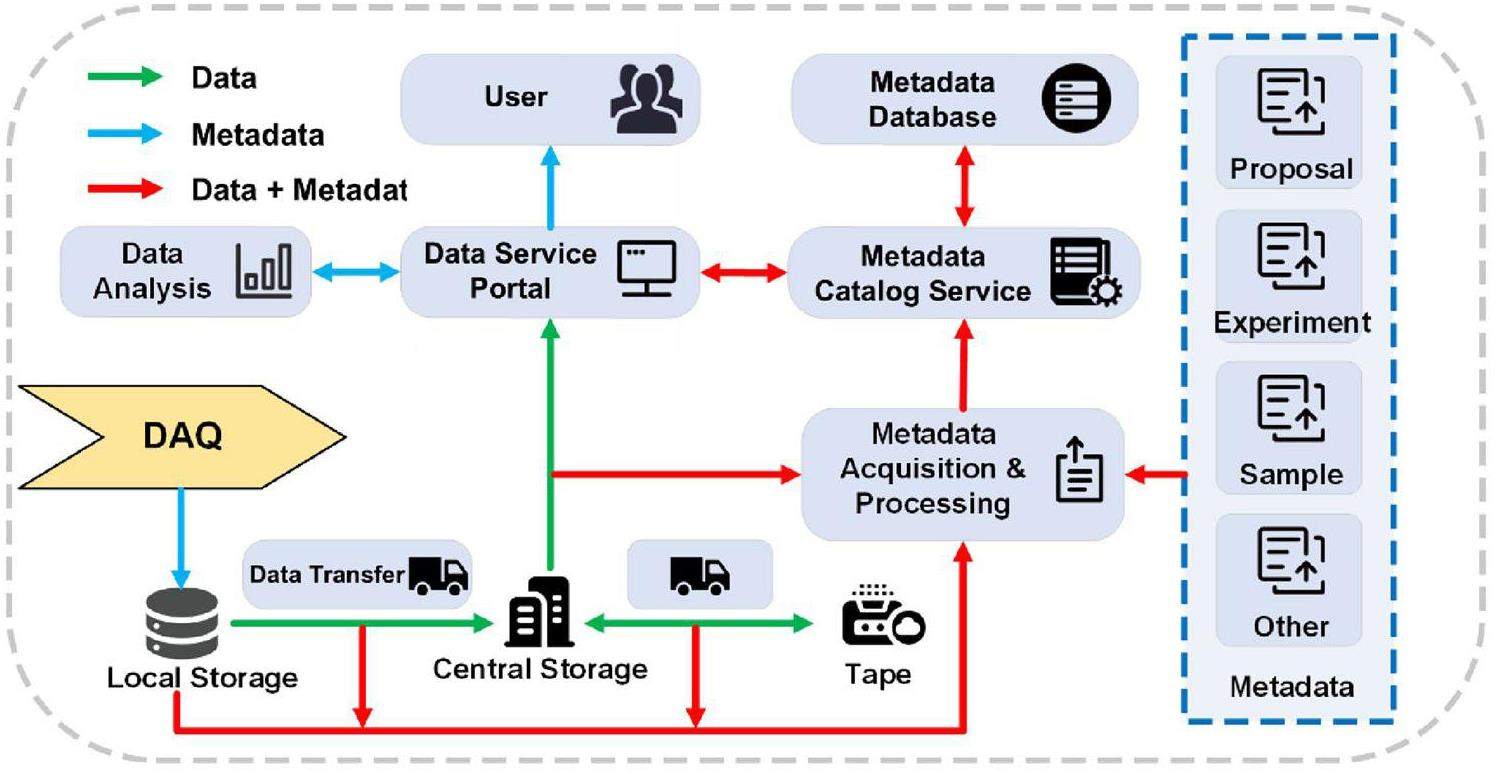

For the management and services related to the access and sharing of white neutron beam data, the NHEPDC provides full-lifecycle data management services, encompassing data transmission, storage, analysis and sharing, to ensure the efficient organization and management of scientific data as shown in Fig. 11. White neutron beam data involve numerous metadata, which are primarily categorized into scientific metadata and management metadata. Scientific metadata include various parameters related to high-energy physics, such as beam power, in white neutron beam experiments. Management metadata consist of information generated during the processes of data transmission, storage, analysis, and sharing, such as data storage paths and file permissions. Data management is implemented using the DOMAS framework [12], which primarily provides metadata catalog services, metadata acquisition and processing systems, data transmission system, and data service system.

Metadata catalog service

The metadata catalog service leverages MongoDB as its database, offering robust capabilities for storing complex metadata and providing application programming interfaces (APIs) for efficient access. This service facilitates seamless utilization of relevant metadata by related systems, such as the proposal system, experiment system, and sample system. In addition, it includes a visualization tool that automatically generates metadata access interfaces based on metadata model designs to enhance accessibility and usability.

Metadata acquisition and processing system

The metadata acquisition and processing system supports the acquisition of administrative and scientific metadata from various subsystems involved in the entire lifecycle of experimental processes, including experimental application, experiment conduction, DAQ, data storage, data transfer, data analysis, data sharing and data publication. This multi-source architecture system utilizes diverse acquisition plugins to extract metadata from different interfaces. In addition, the extracted metadata were associated, integrated, and stored in the metadata database using the APIs provided by the metadata catalogue.

Data transmission system

The data transmission system automates the near-real-time, efficient, and reliable migration of data produced from back-n experiments across different storage systems by leveraging the APIs of various storage systems as described in Sect. 5.2. It integrates multiple protocols including rsync, scp, xrdcp, and eoscp to ensure flexibility and compatibility. To maintain the integrity and accuracy of the data files, the system employed checksum validation. In the event of transmission failure, automatic retransmission is initiated. Furthermore, the system offers comprehensive transfer logs and monitoring capabilities, enabling the effective tracking and management of the entire transfer process.

Data service system

The data service system provides a web-based interface designed to enhance the user experience by enabling seamless access, visualization, downloading, analysis, and sharing of data. It supports the viewing of organized data files along with their associated metadata, providing users with a detailed overview of data structures and contextual information. To safeguard data privacy while promoting collaboration, the system implements dataset-level access control. Principal Investigators (PIs) can securely authorize other researchers to access specific datasets via email, ensuring streamlined and secure sharing processes. Additionally, the system supports online previews of data files in HDF5 and Nexus formats, allowing users to examine file contents efficiently without requiring downloads or specialized software.The system leverages high-performance computing (HPC) resources from the NHEPDC, Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area Branch. These HPC systems provide over 4500 TFLOPS of double-precision floating-point performance and are equipped with specialized neutron simulation and analysis tools, such as FLUKA and MCSTAS. Virtualization technologies are being implemented to further enhance flexibility and resource utilization. This allows users to create virtual machines tailored to complex computational requirements, significantly improving the efficiency and adaptability of data analysis workflows.

Workflow of data-driven processing

A brief overview of the fundamental process for managing the data generated by experiments within a data management system is provided below.

1. Upon the generation of data files by the experimental terminal, a Kafka message containing metadata such as the proposal ID, sample ID, experimental details, and file information is sent.

2. The data-driven processing system consumes the Kafka message based on its offset from (1), leveraging the API of the metadata catalog service to extract metadata from various systems. The management metadata and scientific metadata are then reorganized by assigning data file ownership to the Principal Investigator (PI) of the proposal. Subsequently, the metadata are aligned using the proposal ID and written into the metadata database. Additionally, a file transfer task for moving files from the experimental station storage to the central disk storage was logged in the transfer task database.

(a) Proposal metadata, including proposal name, abstract, PI name, and email, were retrieved from the user system using the proposed ID.

(b) Sample metadata, such as sample name and quality, were extracted from the sample management system using sample ID.

(c) Other systems

3. The data transfer system polls the transfer task database and initiates transfer by upon detecting a new task. After a successful transfer, it sends a Kafka message containing the transfer metadata.

4. The data-driven processing system consumes this Kafka message based on its offset from (3) and uses the metadata catalog service’s API to write the transferred metadata into the metadata database and update the directory location of the data files. A new transfer task for moving files from the central disk storage to the central tape storage was then logged in the transfer task database.

5. The data-driven processing system processes subsequent Kafka messages from (4) similarly, as outlined in Step 4, continuing the workflow for the later stages.

With the support of the NHEPDC, storage and computing systems for white neutron beam data have been officially deployed and are operating efficiently. The data management system is currently in trial operation. Moving forward, we aim to expand the utilization of this data by developing an experimental nuclear reaction database.

Verification and Dissemination of Nuclear Data

To screen out data related to neutron reactions from the raw experimental data, detailed data processing and analysis are necessary.

Experimental data processing and analysis

Data preprocessing

Data format conversion: Convert binary files into root format files based on the storage format of the DAQ system. The Back-n collaboration provided the reference code for this study. The root file stores all the signal information of each event (one proton targeting is an event), including RunNumber, EventNumber, ChanelID, MovieLength, T, and ADCValue.

Abnormal Data Filtering: Determine whether there are abnormal data through statistical methods or domain knowledge, and handle them appropriately.

Data normalization: Data normalization or standardization is performed using the proton beam intensity to eliminate the effects of different scales and magnitudes.

Signal Processing

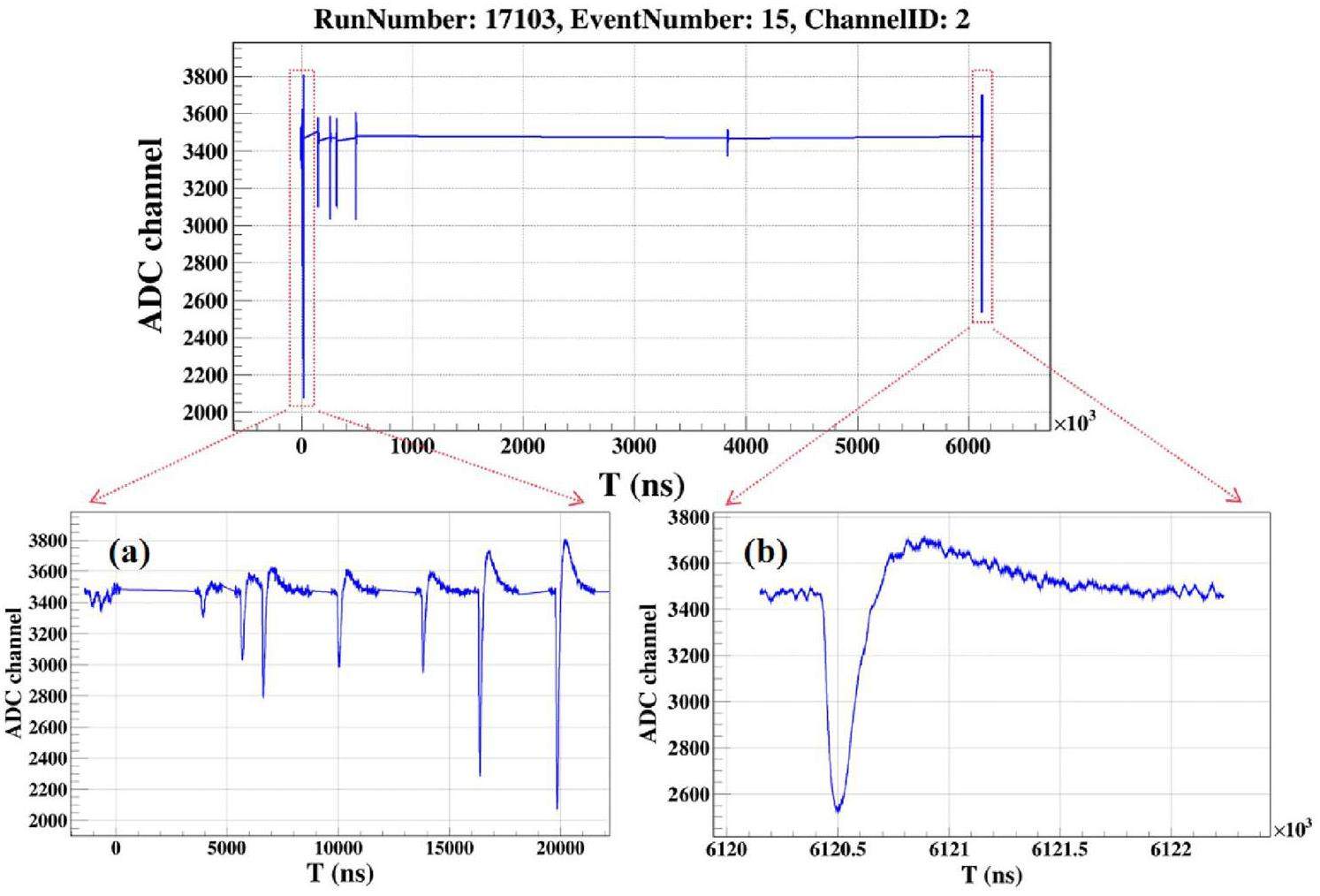

The proton beam hitting the target triggered the T0 signal, after which the system opened a signal acquisition window of approximately 10 ms. Extract all the signals of events within a time window in chronological order from the root file. A complete waveform diagram of an event was obtained, as shown in Fig. 12.

The signals were smoothed using the ROOT program to reduce the effect of noise effectively. Then, peak search and baseline calculation were performed on the signals, and the amplitude and corresponding fission time information of each signal were extracted.

Determination of neutron energy by TOF method

Neutron flight time determination

Neutron production by a 1.6 GeV proton beam hitting the tungsten target is accompanied by the generation of high-intensity γ-rays, called γ-flash. γ-flash and fission signals detected by FIXM are shown in Fig. 12 (a). After traveling at the speed of light for a distance, γ-flash reaches the detector earlier than neutrons with a rest mass. The moment of neutron production is difficult to determine; therefore, the time difference between the detected γ-flash and the neutron signal can be used to determine the neutron’s time-of-flight. The time-of-flight can be calculated using Eq. 4.

Neutron flight distance calibration

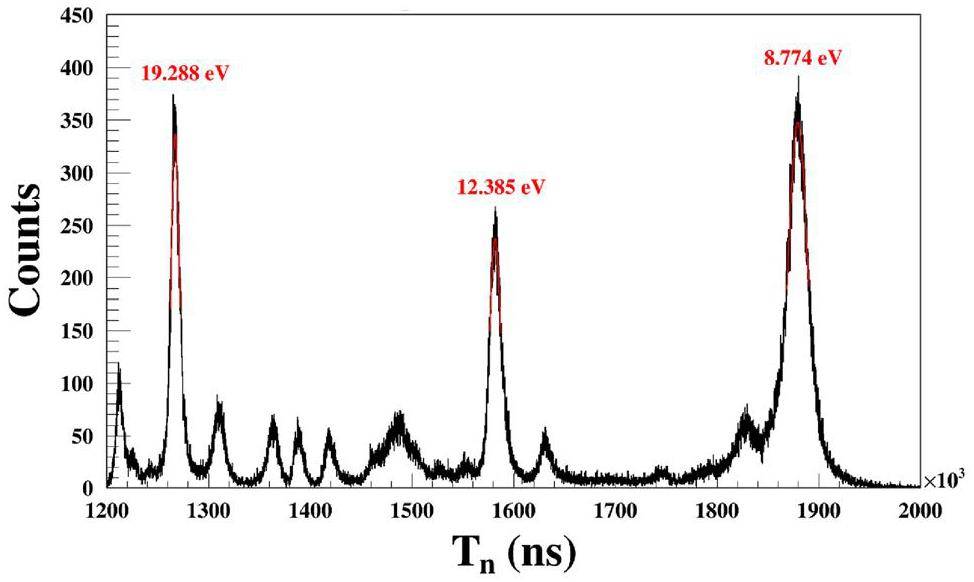

The cathode of the FIXM consists of target cells coated with fissionable nuclides (235U, 238U), and the energies and neutron flight times corresponding to the 235U resonance peaks can be used to calibrate the neutron flight distance. Figure 13 shows the fission time distribution of the signals obtained from the 235U fission cell, and the three low-energy resonance peaks (8.77 eV, 12.38 eV, 19.28 eV) are clearly visible. The resonance peaks were fitted using a Gaussian function to obtain fission time. According to the relationship between the energy of the resonance peaks and the corresponding fission time in the TOF method, the neutron flight distance can be obtained by fitting Eq. 5.

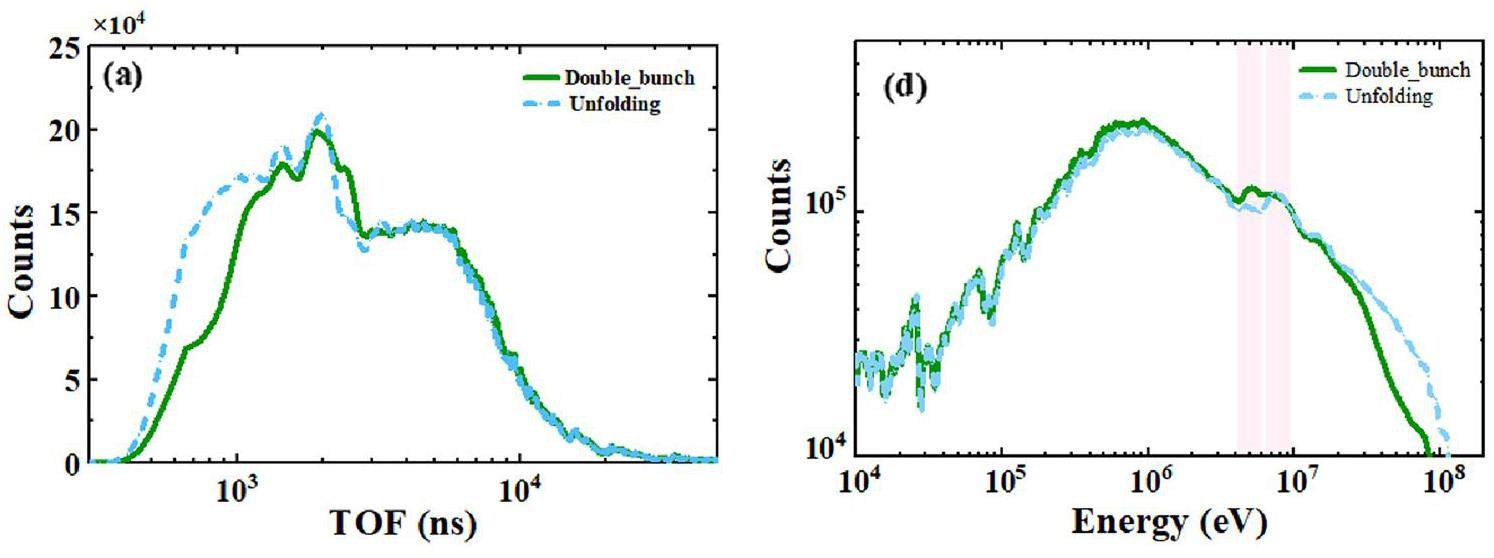

Double-bunch unfolding

To increase the neutron intensity, the experiment used the double-bunch mode with a time interval of approximately 410 ns between the two bunches. However, this mode leads to superposition of the TOF spectrum, introducing a bias to the counting of high-energy neutrons. At neutron energies up to 10 keV, the time resolution impact caused by the double-bunch was approximately 1%. As the neutron energy increases, the time resolution gradually worsens. For this problem, the Back-n collaboration has developed a Demo Unfolding code, which is based on the Bayesian iterative method [13]. The TOF spectrum corresponding to the single-bunch mode can be obtained by linking the measured values with the true values through the response matrix and using Bayes’ theorem and iterative algorithms to estimate the true values. The unfolding error is determined by the factors of neutron energy and statistics, therefore, there are differences in the experiments. Among these, measurement of the neutron energy spectrum is the most important. The neutron energy spectra of Back-n were measured several times, and neutron energy spectra at different end stations and collimation aperture diameters were obtained. Related errors were also analyzed. The neutron energy spectrum data can serve as a reference for most nuclear data measurement experiments [14-16]. Reference [4] presents the neutron spectrum errors brought by unfolding.

Figure 14 shows the changes in the TOF and energy spectra before and after the unfolding process, and the double peaks in the high energy region were restored to a single peak after unfolding.

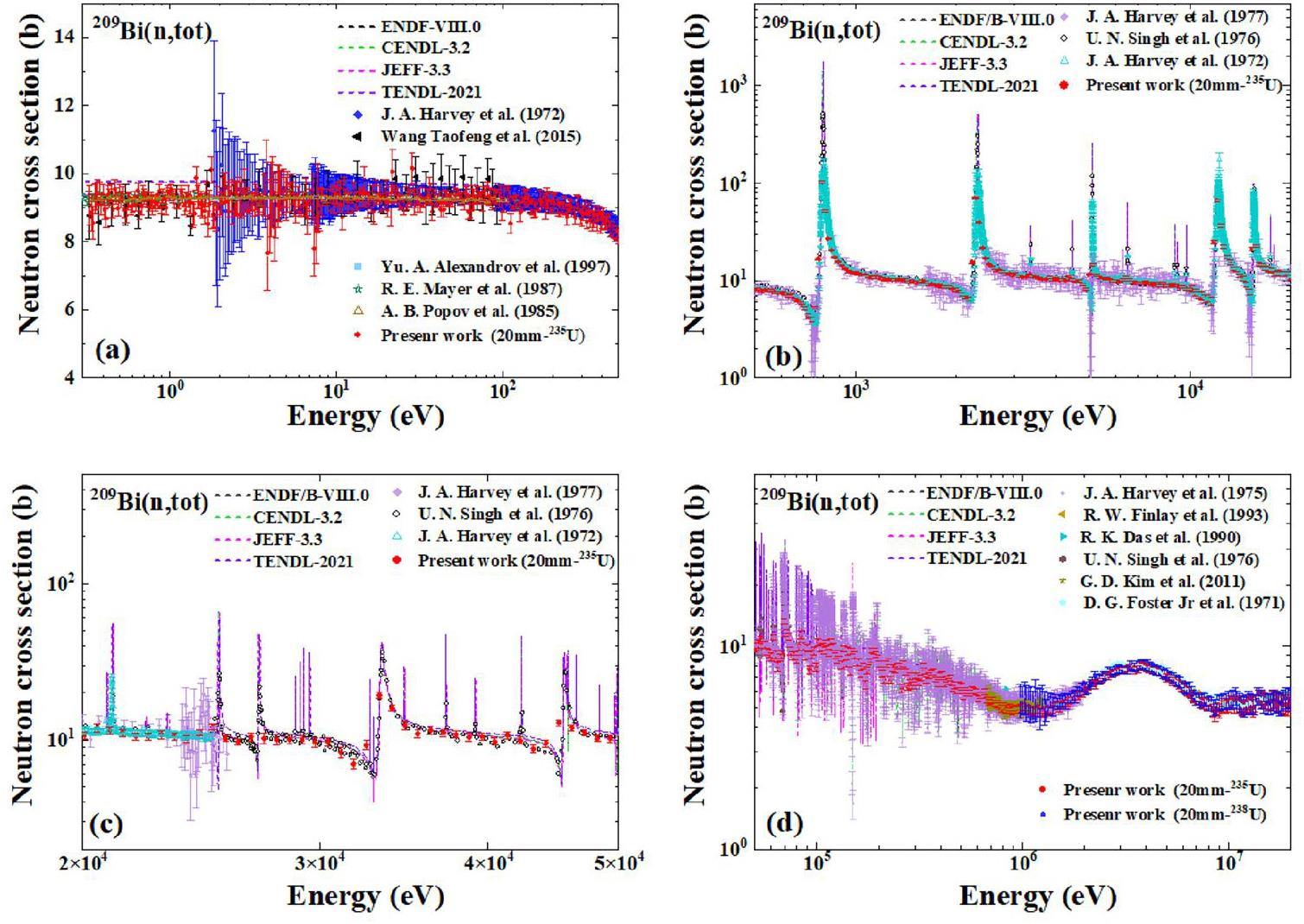

The sources of the experimental background for different nuclear reaction measurements are different and need to be analyzed according to the specific experimental conditions and reaction type. The experimental background can be deducted by setting a threshold for the measurement of neutron-induced total cross-sections using FIXM. After deducting the background, the neutron counts obtained for sample-in and sample-out were ratios used to obtain the neutron transmission. The neutron-induced total cross-sections were obtained according to Eq. 2. Further analysis needs to consider data corrections, such as dead time correction and multiple scattering correction. Uncertainty analysis is required, such as the error of counting statistics and the error of the neutron energy scale. Finally, based on the analysis results, a detailed explanation and discussion of the experimental objectives are provided. Figure 15 shows the results of neutron-induced cross-section measurements of 209Bi from 0.3 eV to 20 MeV on Back-n at the CSNS [17].

The statistical uncertainties associated with neutron counts are a primary source of error. These uncertainties are particularly significant in regions with low neutron fluxes such as the resonance region (1 eV to 1 keV). The use of thicker samples (e.g., 20 mm) helps reduce these uncertainties by increasing the number of detected events, thereby improving the statistical quality of the data. At 98% of these energy bins, the uncertainties were less than 10%, with 80% of them being below 5%. Furthermore, 12% of the energy bins had uncertainties less than 2%. It can be observed that the measured data are in good agreement with the evaluation data and other experimental data. It is worth noting that the total section measurement is one of the experiments with relatively small errors in the nuclear data measurement. In some other measurements, such as capture cross-section measurement and neutron-induced charged particle emission cross-section measurement, interference from the background and substrate is also an important source of error. These experiments often use standard cross-section targets or empty target experimental results as references for measurements to subtract the background.

This is a simplified overview of the analytical process. Measurements of different nuclear reactions are unique; therefore, the data processing steps vary.

Back-n white neutron facility at CSNS and first-year nuclear data measurements

. EPJ Web of Conferences 239, 06002 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/202023906002Initial years’ neutron-induced cross-section measurements at the CSNS Back-n white neutron source

. Chinese Phys. C 45,Detector development at the Back-n white neutron source

. Radiat. Detect. Technol. Meth. 7, 171-191 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41605-022-00379-5Back-n white neutron source at CSNS and its applications

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 11 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00846-6A multi-cell fission chamber for fission cross-section measurements at the Back-n white neutron beam of CSNS

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. Sect. A 940, 486-491 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2019.06.014Electronics of time-of-flight measurement for Back-n at CSNS

. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 66, 1195-1199 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1109/TNS.2019.2900480Real-time digital trigger system for GTAF-II at CSNS Back-n white neutron source

. J. Instrum. 16,General-purpose readout electronics for white neutron source at China Spallation Neutron Source

. Rev. Scient. Instrum. 89,Prototype of readout electronics for GAEA gamma spectrometer of Back-n facility at CSNS

. J. Instrum. 17,ROOT JavaScript

. 2025. URL: https://root.cern.ch/js/ (Accessed:DOMAS: a data management software framework for advanced light sources

. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 31, 312-321 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1107/S1600577524000043Double-bunch unfolding methods for the Back-n white neutron source at CSNS

. J. Instrum. 15,Neutron energy spectrum measurement of the Back-n white neutron source at CSNS

. Eur. Phys. J. A 55, 115 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2019-12808-1Measurement of the neutron energy spectrum of Back-n ES#1 at CSNS

. EPJ Web of Conferences 239, 17018 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/202023917018Measurement of the neutron flux of CSNS Back-n ES#1 under small collimators from 0.5 eV to 300 MeV

. Eur. Phys. J. A 60, 63 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-024-01272-zMeasurement and analysis of the neutron-induced total cross-sections of 209Bi from 0.3 eV to 20 MeV on the Back-n at CSNS

. Chinese Phys. C 47,The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.