Introduction

Since the identification of the first Λ hyperfragment in an emulsion exposed to cosmic rays in 1952 [1], Λ hypernuclei have been intensively studied, both experimentally [2-9] and theoretically [10-16]. Recent studies have mainly focused on hyperon-nucleon (YN) interactions [16-25], hypernuclear structure [15, 24, 26-31], and hypernuclear decay [7, 32-38] and so on. understanding the internal structure and YN interactions is a challenging goal in nuclear physics.

A single-Λ hypernucleus, which consists of a normal core nucleus and a Λ hyperon, provides a unique environment for investigating ΛN interactions. The degree of freedom of strangeness liberates the Λ hyperon from the constraints of the nuclear Pauli exclusion principle, allowing it to penetrate deeply into the nucleus and alter the core structure as an impurity. Therefore, the presence of impurity effects in the Λ hypernuclear system is crucial for illuminating nuclear features that might remain obscure in normal nuclei, including both the structure and interactions.

With the emergence of new and improved experimental facilities, the measurement of Λ hypernuclear binding energies spans a broad mass range from light to heavy with high resolution. These advancements not only enhance our understanding of Λ hypernuclear properties compared to previous studies but also pose challenges to the development and refinement of theoretical approaches in hypernuclear structures. To comprehensively describe these crucial nuclear properties, various types of ΛN interactions have been introduced and discussed. These include the Skyrme types [39-47], relativistic types [48-54], Nijmegen soft-core (NSC) types [55-57], Nijmegen extended-soft-core (ESC) types [13, 18, 21, 58-60] and chiral effective field theory (

Over the past decades, two types of ΛN interactions have been proposed and adopted in the Skyrme-Hartree-Fock (SHF) model. The first type, derived from Brueckner-Hartree-Fock (BHF) calculations of hypernuclear matter, has a more microscopic basis. The second type is phenomenological Skyrme-type interactions, which are determined by fitting the experimental binding energies of Λ hypernuclei. Microscopic interactions originate from deeper physical principles (e.g., explicit momentum/density dependence). However, owing to the limited experimental data on Λ hypernuclei at present, microscopic interactions do not describe Λ hypernuclei very well. In contrast, phenomenological Skyrme-type interactions, which are determined by fitting the experimental binding energies of Λ hypernuclei, can better predict the ground-state properties of the hypernuclei.

Although Skyrme interactions provide a good description of hypernuclei, there are still some details that require improvement. For the Skyrme interaction, the parameter sets are RAY12 [39, 40], YBZ1 [42], SKSH2 [43], HPΛ2 [45], and SLL4 [47]. Different interactions were obtained by fitting different ground-state or excited-state energies of Λ hypernuclei. Moreover, different three-body interactions were considered in different Skyrme interactions. The Skyrme interaction with three-body interaction derived from the G-matrix can provide a good description of Λ hypernuclei ranging from light mass to heavy mass, such as SLL4 and HPΛ2. However, the Skyrme interaction with three-body interaction derived from the ΛNN contact force, like RAY12, YBZ1, and SKSH2, cannot provide a global description. A noticeable feature in the calculated results with the ΛNN contact force is that the parameters fitted to the binding energies of light-mass Λ hypernuclei, such as RAY12, YBZ1, and SKSH2, clearly fail to predict the experimental results for heavy-mass hypernuclei. Moreover, the calculated binding energies of heavy-mass Λ hypernuclei are smaller than the experimental values [77]. This underbinding shows that the ΛN potential depth is not sufficiently deep in heavy-mass Λ hypernuclei. This phenomenon is found not only in Skyrme interactions but also in other types of hyperon-nucleon interactions. For microscopic interactions, the calculated binding energies with the NSC89 interaction were smaller than the experimental results for heavy Λ hypernuclei [26]. The NSC97f interaction gives good results for heavy Λ hypernuclei, but its prediction for light Λ hypernuclei is approximately 2 MeV higher [26]. For the optical potential, the experimental binding energies of heavy Λ hypernuclei are larger than those calculated with the interaction obtained by fitting the 1s and 1p states of

In previous Skyrme-type interactions, only the simplest form of the contact ΛNN three-body interaction was considered [79]. However, an important feature of the ΛNN interaction is its proportionality to the isospin factor

In the optical potential methodology [14, 81], the effects of neutron excess, considered using a more phenomenological approach, are discussed to address the underbinding issue in heavy-mass Λ hypernuclei. Deformation is a fundamental property of hypernuclei and has a significant impact on the BΛ and other properties, especially for Λ states above the 1s state; therefore, it cannot be ignored. Furthermore, the pairing force is crucial in the calculation of nuclear properties [82]. In this study, the impact of neutron excess on deformed Λ hypernuclei is discussed in the framework of the SHF method with pairing force, which deals with the Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer (BCS) approximation.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: In Sect. 2, the theoretical method and interaction are briefly described. In Sect. 3, we discuss the binding energies of Λ hypernuclei and present the Λ single-particle potential along with the changes in the density distributions due to neutron excess. Finally, a summary is given in Sect. 4.

Theoretical descriptions

In the SHF approach, the total energy of a hypernucleus is given by [40, 83-87]

Through the variation in the total energy, Eq. (1), one derives the SHF Schödinger equation for both nucleons and hyperons:

For the Skyrme-type interactions,

Then one obtains the corresponding SHF mean fields:

When excess neutrons occupy shell-model orbits that are higher than those occupied by protons, ρN is separated as:

In the present calculations, the deformed SHF Schrödinger equation was solved in cylindrical coordinates (r,z), under the assumption of axial symmetry of the mean fields. When compared with experimental deformations derived from the quadrupole moment Qp, we employ the definition

Results and discussion

In order to study the influence of neutron excess on Skyrme-type interaction RAY12, YBZ1 and SKSH2, we calculated the binding energies of Λ hypernuclei:

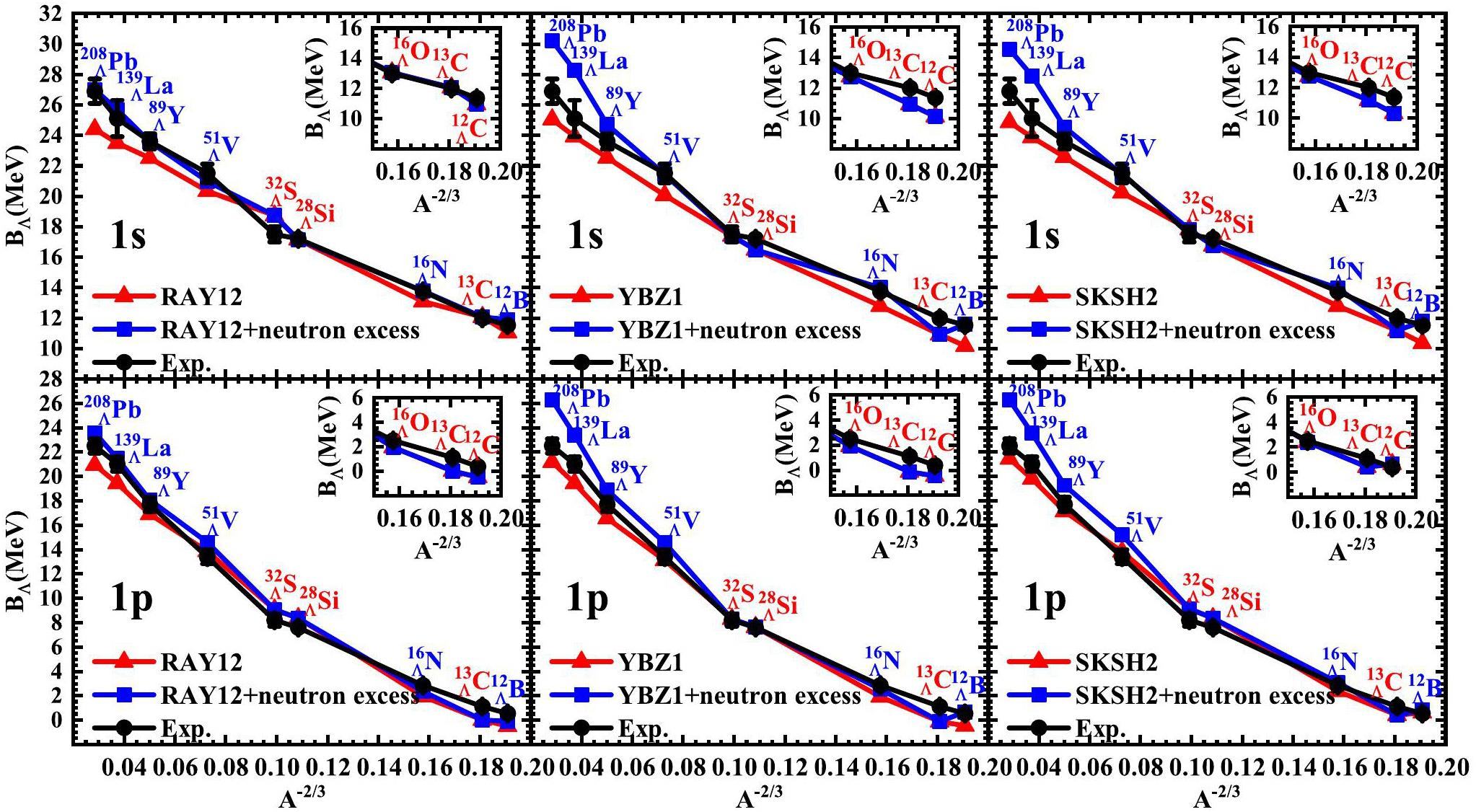

Figure 1 shows the binding energies for the 1s and 1p states calculated with and without neutron excess compared to the experimental data. The red triangles show the results without neutron excess, blue squares show the results with neutron excess, and black circles show the experimental results from Ref. [99]. To better present the results of

It is clearly seen that the binding energies calculated using the Skyrme-type interactions RAY12, YBZ1 and SKSH2 failed to predict the experimental results in the heavy-mass hypernuclei. Moreover, the calculated binding energies in the heavy-mass Λ hypernuclei were smaller than the experimental values. This underbinding shows that the ΛN potential depth is not sufficiently deep in heavy-mass Λ hypernuclei. The reason for this phenomenon is that the parameter are fitted to the binding energies of the light-mass Λ hypernuclei. Therefore, the calculated results from the interaction exhibited poor agreement with the experimental values in the heavy-mass region. It is evident that the behavior of light-mass hypernuclei with symmetric nuclear matter core nuclei differs from that of heavy-mass hypernuclei with asymmetric nuclear matter core nuclei. Therefore, the influence of the isospin of the core nuclei on the binding energy calculations is significant. The ΛNN three-body is related to the isospin factor

In Fig. 1, it is clear that the neutron excess slightly changes the binding energies of light-mass Λ hypernuclei with excess neutrons because excess neutrons are small in the light mass. Most importantly, neutron excess significantly increases the binding energies of heavy-mass Λ hypernuclei, because hypernuclei with heavy mass often have more excess neutrons. For the Skyrme-type interactions RAY12, YBZ1, and SKSH2, the interactions with neutron excess lead to better agreement with the experimental results of

To check the overall description using RAY12 for all 11 hypernuclei, we calculate and list in Table 1 the average deviation

| Hypernucleus | Exp. | RAY12 | SLL4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a0 | -237.40 | -237.40 | -322.00 | |

| a1 | - | - | 15.75 | |

| a2 | -6.85 | -6.85 | 19.63 | |

| a3 | - | - | 715.00 | |

| 250.00 | 250.00 | - | ||

| α | - | - | 1.00 | |

| 11.52±0.02 | 11.04 | 11.90 | 10.98 | |

| 11.36±0.2 | 10.96 | 10.96 | 10.94 | |

| 12.0±0.2 | 12.07 | 12.07 | 11.83 | |

| 13.76±0.16 | 13.09 | 13.77 | 13.63 | |

| 13.0±0.2 | 13.05 | 13.05 | 13.61 | |

| 17.2±0.2 | 17.16 | 17.16 | 17.68 | |

| 17.5±0.5 | 18.72 | 18.72 | 18.74 | |

| 21.5±0.6 | 20.33 | 20.99 | 21.39 | |

| 23.6±0.5 | 22.50 | 23.56 | 23.89 | |

| 25.1±1.2 | 23.49 | 25.69 | 25.19 | |

| 26.9±0.8 | 24.41 | 27.00 | 26.24 | |

| 0.54±0.04 | -0.48 | -0.09 | 0.07 | |

| 0.36±0.2 | -0.51 | -0.51 | 0.79 | |

| 1.1±0.2 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.49 | |

| 2.84±0.18 | 1.95 | 2.34 | 2.61 | |

| 2.5±0.2 | 1.93 | 1.93 | 2.61 | |

| 7.6± 0.2 | 8.36 | 8.36 | 8.73 | |

| 8.2± 0.5 | 9.08 | 9.08 | 9.48 | |

| 13.4± 0.6 | 13.85 | 14.59 | 14.44 | |

| 17.7± 0.6 | 16.89 | 18.07 | 17.93 | |

| 21± 0.6 | 19.45 | 21.48 | 20.78 | |

| 22.5±0.6 | 20.95 | 23.59 | 22.47 | |

| 63.09 | 31.86 | 42.83 | ||

| Δ | 1.06 | 0.66 | 0.61 |

Table 2 lists the quadrupole deformation parameters β and the binding energies of the Λ 1s and 1p states for various hypernuclei, comparing deformed results with their spherical counterparts (values in brackets). The data reveals that deformation has a significant impact on the binding energy, particularly for hypernuclei in the 1pΛ state. For instance, for

| Hypernucleus | β | binding energy |

|---|---|---|

| -0.09 | 11.90 (11.95) | |

| -0.09 | 10.96 (10.97) | |

| 0.00 | 12.07 (12.07) | |

| 0.00 | 13.77 (13.77) | |

| 0.00 | 13.05 (13.05) | |

| -0.22 | 17.16 (17.21) | |

| 0.00 | 18.72 (18.72) | |

| 0.14 | 20.99 (20.95) | |

| -0.02 | 23.56 (23.56) | |

| 0.06 | 25.69 (25.90) | |

| 0.00 | 27.00 (27.00) | |

| -0.21 | -0.09 (-1.28) | |

| -0.207 | -0.51 (-1.71) | |

| -0.15 | 0.00 (-0.42) | |

| 0.07 | 2.34 (1.73) | |

| 0.09 | 1.93 (1.06) | |

| -0.26 | 8.36 (7.30) | |

| 0.12 | 9.08 (8.62) | |

| 0.17 | 14.59 (13.69) | |

| -0.04 | 18.07 (17.95) | |

| 0.06 | 21.48 (21.36) | |

| 0.00 | 23.59 (23.59) |

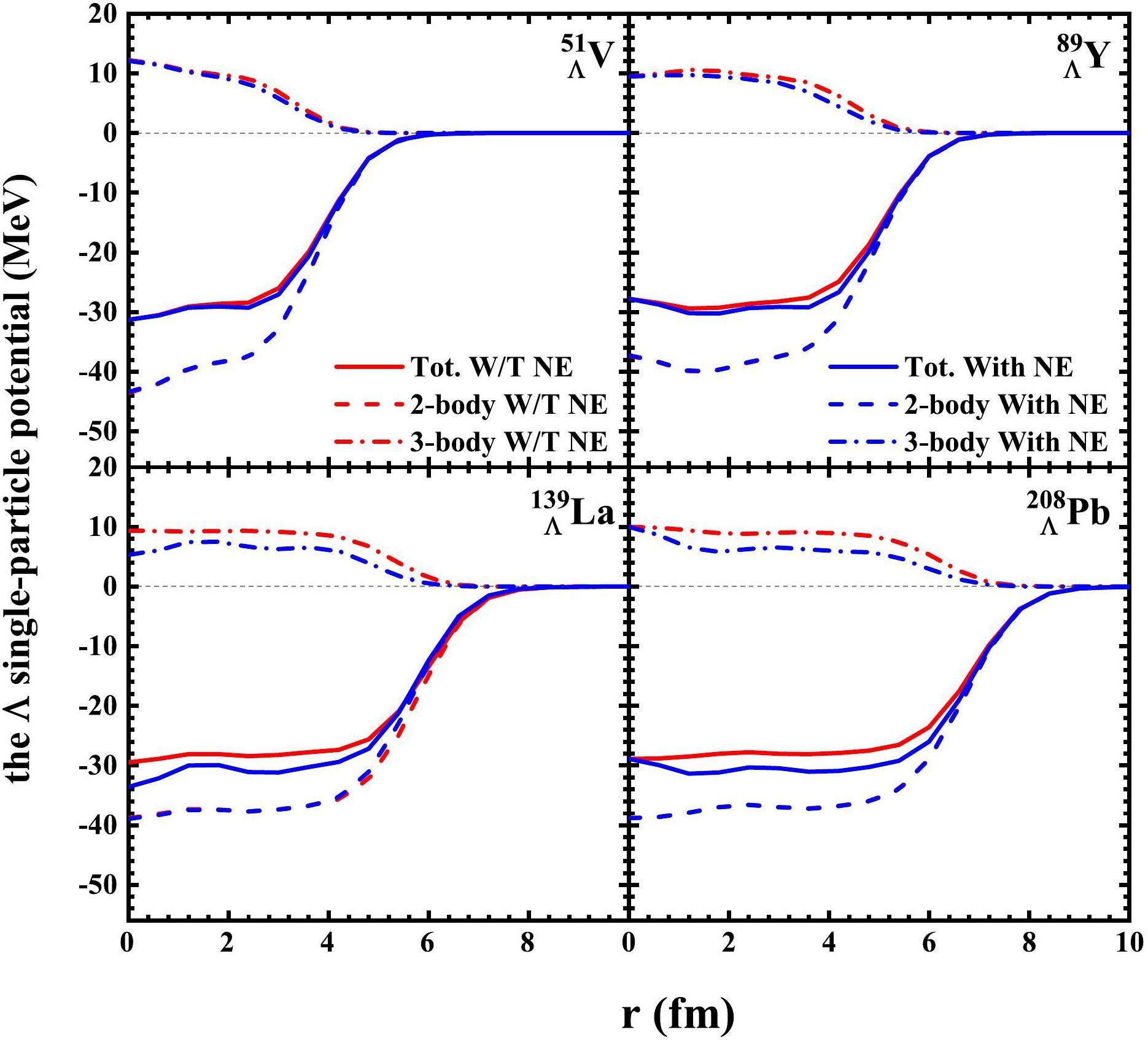

Figure 2 shows the Λ single-particle potential as a function of the radial distance

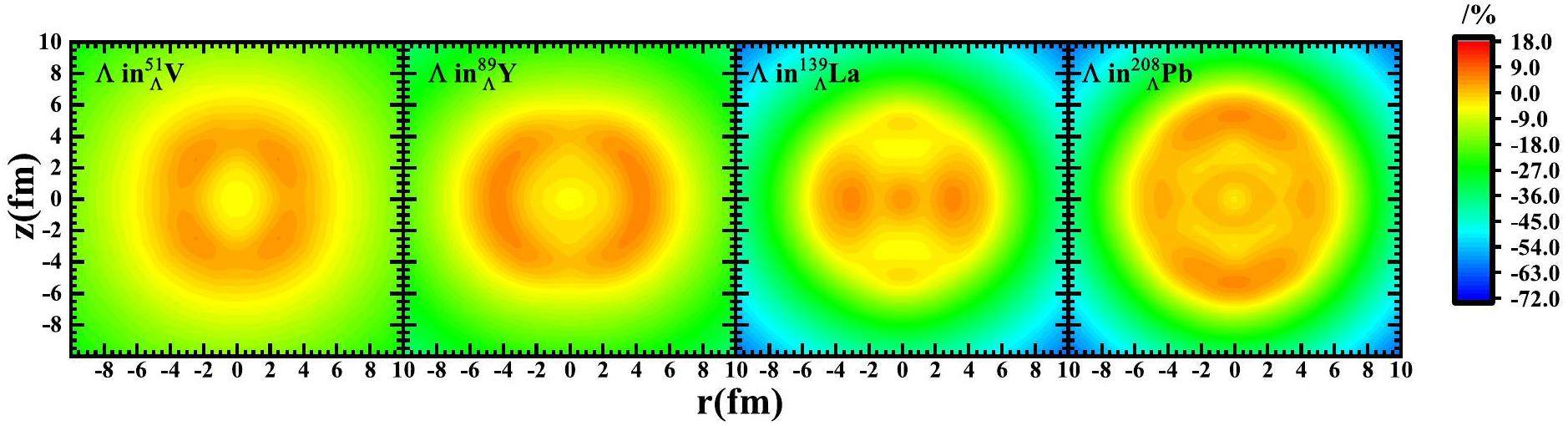

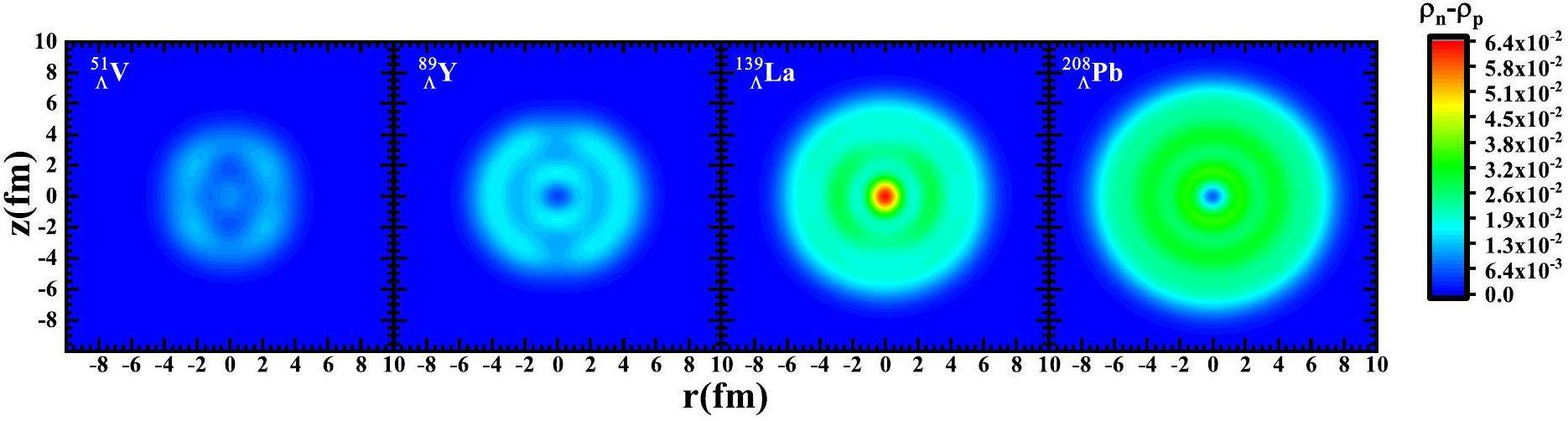

Figure 3 shows the rate of change in the hyperon density in the r-z plane due to neutron excess for four hypernuclei

Summary

The effects of neutron excess on the Λ hypernuclei were studied by using the deformed SHF model in this work. Suppressing the ΛNN interaction between ‘core’ nucleons and ‘excess’ neutrons addresses underbinding in heavy-mass Λ hypernuclei. The microscopic mechanism can be explained as follows: the neutron excess decreases the repulsive ΛNN interaction, which can prevent this issue and be directly observed from the depth variation of the hyperon potential.

In addition, to quantitatively assess the impact of neutron excess, the binding energies of 1s and 1p Λ states for

By incorporating the isospin for the two nucleons into the three-body ΛNN interaction, a better prediction of the hypernuclear structure can be achieved. In the future, corrections for neutron excess will be introduced into the calculations of multi-Λ hypernuclei and Ξ hypernuclei (S=2).

Delayed disintegration of a heavy nuclear fragment: I

. Lond. Edinburgh Dublin Philos. Magazine J. Sci. 44, 348-350 (1953). https://doi.org/10.1080/14786440308520318γ-ray spectroscopy in Λ hypernuclei

. Nucl. Phys. A 754, 58-69 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2005.01.034Spectroscopy of Λ hypernuclei

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 57, 564-653 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2005.07.001Prospects for hypernuclear physics at Mainz: From KAOS@ MAMI to PANDA@ FAIR

. Nucl. Phys. A 914, 519-529 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2013.02.008Observation of antimatter nuclei at RHIC-STAR

. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 420,Experimental review of hypernuclear physics: recent achievements and future perspectives

. Rep. Prog. Phys. 78,Measurements of HΛ3 and HΛ4 lifetimes and yields in Au+Au collisions in the high baryon density region

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128,Observation of directed flow of hypernuclei HΛ3 and HΛ4 in sNN=3 GeV Au+Au collisions at RHIC

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130,Observation of the antimatter hypernucleus Λ¯4H¯

. Nature 632, 1026-1031 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07823-0A meson exchange model for the hyperon-nucleon interaction

. Nucl. Phys. A 500, 485-528 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(89)90223-6Multiply strange nuclear systems

. Ann. Phys. 235, 35-76 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1006/aphy.1994.1090Double-Λ hypernuclei in the Skyrme-Hartree-Fock approach and nuclear core polarization

. Phys. Rev. C 58, 3351 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.58.3351Status of understanding the YN/YY-interactions: Meson-exchange viewpoint

. Nucl. Phys. A 835, 160-167 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2010.01.189Constraints from Λ hypernuclei on the ΛNN content of the Λ-nucleus potential

. Phys. Lett. B 837,Structure of neutron-rich He Λ hypernuclei using the cluster orbital shell model

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Light Λ hypernuclei studied with chiral hyperon-nucleon and hyperon-nucleon-nucleon forces

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134,Modern theory of nuclear forces

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 1773-1825 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.81.1773Baryon-baryon interactions—Nijmegen extended-soft-core models

. Prog. Theor. Phys. Suppl. 185, 14-71 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1143/PTPS.185.14Leading order relativistic chiral nucleon-nucleon interaction

. Chin. Phys. C 42,Leading order relativistic hyperon-nucleon interactions in chiral effective field theory

. Chin. Phys. C 42,Extended-soft-core baryon-baryon model ESC16. III. S=-2 hyperon-hyperon/nucleon interactions

. Phys. Rev. C 102,Test of the hyperon-nucleon interaction within leading order covariant chiral effective field theory

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Hypernuclei as a laboratory to test hyperon–nucleon interactions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 97 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01248-6Hyperon-nucleon interaction constrained by light hypernuclei

. Phys. Lett. B 846,Hyperon–nucleon interaction in chiral effective field theory at next-to-next-to-leading order

. Eur. Phys. J. A 59, 63 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-023-00960-6Hypernuclear structure with the new Nijmegen potentials

. Phys. Rev. C 64,Hypernuclear structure from γ-ray spectroscopy

. Nucl. Phys. A 754, 48-57 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2004.12.068Structure of light hypernuclei

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 63, 339-395 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2009.05.001Structure of single-Λ hypernuclei with chiral hyperon–nucleon potentials

. Eur. Phys. J. A 56, 55 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-020-00055-6Low-lying level structure of Λ hypernuclei and spin dependence of the Λ N interaction with antisymmetrized molecular dynamics

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Deformation and hyperon halo in hypernuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Mesonic and non-mesonic Λ-decay in nuclei

. Nucl. Phys. A 443, 704-725 (1985). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(85)90220-9Nonmesonic decays of Λ4H, Λ4He and Λ5He hypernuclei by the π and ρ exchange model

. Prog. Theor. Phys. 73, 841-844 (1985). https://doi.org/10.1143/PTP.73.841Hypernuclear weak decay of Λ12C and Λ11B

. Phys. Rev. C 52, 2936 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.52.2936Weak decay of Λ-hypernuclei

. Phys. Rep. 369, 1-109 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0370-1573(02)00199-0Formation and dynamics of exotic hypernuclei in heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 102,Evaluation of hypernuclei in relativistic ion collisions

. Eur. Phys. J. A 56, 1-15 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-020-00217-6Extracting the hyperon-nucleon interaction via collective flows in heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 851,Self-consistent calculations of hypernuclear properties with the Skyrme interaction

. Ann. Phys. 102, 226-251 (1976). https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-4916(76)90262-1Skyrme parametrization of an effective Λ-nucleon interaction

. Nucl. Phys. A 367, 381-397 (1981). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(81)90655-2Λ-nucleus single-particle potentials

. Phys. Rev. C 38, 2700 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.38.2700On the Λ-hypernuclear single particle energies

. Prog. Theor. Phys. 80, 757-761 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1143/PTP.80.757Skyrme-Hartree-Fock calculation of Λ-hypernuclear states from (π+, K+) reactions

. Z. Phys. A 334, 349-354 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01284562G-matrix approach to Hyperon-Nucleus systems

. Prog. Theor. Phys. Suppl. 185, 72-105 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1143/PTPS.185.72A study of Λ hypernuclei within the Skyrme–Hartree–Fock model

. Nucl. Phys. A 886, 71-91 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2012.05.005Skyrme force for light and heavy hypernuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 90,Skyrme forces for lambda and cascade hypernuclei

. In AIP Conference Proceedings 2130,Relativistic mean field theory for lambda hypernuclei and neutron stars

. Prog. Theor. Phys. 92, 803-813 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1143/ptp/92.4.803Relativistic description of Λ, ∑, and Ξ hypernuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 49, 2472 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.49.2472Hypernuclei with meson-exchange hyperon-nucleon interactions

. Nucl. Phys. A 608, 305-315 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(96)00169-8Description of single-Λ hypernuclei with a relativistic point-coupling model

. Phys. Rev. C 85,Single-Λ hypernuclei in the relativistic mean-field theory with parameter set FSU

. J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 39,A new determination of the lambda-nucleon coupling constants in relativistic mean field theory

. Commun. Theor. Phys. 60, 479 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1088/0253-6102/60/4/16New effective interactions for hypernuclei in a density-dependent relativistic mean field model

. Phys. Rev. C 104,Soft-core baryon-baryon one-boson-exchange models. II. Hyperon-nucleon potential

. Phys. Rev. C 40, 2226 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.40.2226Soft-core hyperon-nucleon potentials

. Phys. Rev. C 59, 21 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.59.21Soft-core baryon-baryon potentials for the complete baryon octet

. Phys. Rev. C 59, 3009 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.59.3009Hypernuclear properties derived from the new interaction model ESC08

. Nucl. Phys. A 835, 350-353 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2010.01.216Baryon–Baryon Interactions S= 0,-1,-2,-3,-4: Nijmegen Extended-Soft-Core ESC08-models

. Few-Body Syst. 54, 801-806 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00601-013-0621-5Extended-soft-core baryon-baryon model ESC16. II. Hyperon-nucleon interactions

. Phys. Rev. C 99,Hyperon–nucleon interactions—a chiral effective field theory approach

. Nucl. Phys. A 779, 244-266 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2006.09.006Hyperon–nucleon interaction at next-to-leading order in chiral effective field theory

. Nucl. Phys. A 915, 24-58 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2013.06.008Hyperon–nucleon interaction within chiral effective field theory revisited

. Eur. Phys. J. A 56, 91 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-020-00100-4Deformation of hypernuclei studied with antisymmetrized molecular dynamics

. Phys. Rev. C 83,Impurity effects of the Λ particle on the 2α cluster states of 9Be and 10Be

. Phys. Rev. C 92,Competing effects of nuclear deformation and density dependence of the ΛN interaction in BΛ values of hypernuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 94,Effects of a hyperonic many-body force on B Λ values of hypernuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 95,Ab initio approach to s-shell hypernuclei Λ3H, Λ4H, Λ4He and Λ5He with a ΛN-∑N interaction

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89,Jacobi no-core shell model for p-shell hypernuclei

. Eur. Phys. J. A 56, 1-20 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-020-00314-6Clusterization and deformation of multi-Λ hypernuclei within a relativistic mean-field model

. Phys. Rev. C 99,Structure of Λ9Be and ΛΛ 10Be using the beyond-mean-field Skyrme-Hartree-Fock approach

. Phys. Rev. C 97,Generator coordinate method for hypernuclear spectroscopy with a covariant density functional

. Phys. Rev. C 93,Disappearance of nuclear deformation in hypernuclei: A perspective from a beyond-mean-field study

. Phys. Rev. C 97,Deformation and spin-orbit splitting of Λ hypernuclei in the Skyrme-Hartree-Fock approach

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Structure of low-lying states of 12C and Λ13C in a beyond-mean-field approach

. Phys. Rev. C 109,ΛΛ pairing effects in spherical and deformed multi-Λ hyperisotopes

, Phys. Rev. C 105,Effects of Λ hyperons on the deformations of even–even nuclei

, Chin. Phys. C 46,Lambda binding energies in the Skyrm Hartree-Fock approach with various ΛN interactions

, Eur. Phys. J. A 58, 21 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-022-00672-3The effective nuclear potential

. Nucl. Phys. 9, 615-634 (1958). https://doi.org/10.1016/0029-5582(58)90345-6A shell-model analysis of Λ binding energies for the p-shell hypernuclei. I. Basic formulas and matrix elements for ΛN and ΛNN forces

, Ann. Phys. 63, 53-126 (1971). https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-4916(71)90297-1Λ hypernuclear potentials beyond linear density dependence

. Nucl. Phys. A 1039,Self-consistent calculation of charge radii of Pb isotopes

. Nucl. Phys. A 551, 434-450 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(93)90456-8Hartree-Fock calculations with Skyrme’s interaction. II. Axially deformed nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 7, 296-316 (1973). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.7.296Hypernuclei in the Skyrme-Hartree-Fock formalism with a microscopic hyperon-nucleon force

. Phys. Rev. C 62,Hypernuclei in the deformed Skyrme-Hartree-Fock approach

. Phys. Rev. C 76,Λ hyperons and the neutron drip line

. Phys. Rev. C 78,Hyperons as a probe of nuclear deformation

. Prog. Theor. Phys. 123, 569-580 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1143/PTP.123.569A Skyrme parametrization from subnuclear to neutron star densities Part II. Nuclei far from stabilities

. Nucl. Phys. A 635, 231-256 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(98)00180-8Shell structure of superheavy nuclei in self-consistent mean-field models

. Phys. Rev. C 60,Electromagnetic moments and electric dipole transitions in carbon isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 68,Consequences of the center-of-mass correction in nuclear mean-field models

. Eur. Phys. J. A 7, 467-478 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1007/s100500050419Shape of Λ hypernuclei in the (β,γ) deformation plane

. Phys. Rev. C 83,Hyperon halo structure of C and B isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 103,Skyrme-Hartree-Fock treatment of Λ and ΛΛ hypernuclei with G-matrix motivated interactions

. Phys. Rev. C 55, 2330-2339 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.55.2330Transition probability from the ground to the first-excited 2+ state of even-even nuclides

. Atom. Data Nucl. Data Tables 78, 1-128 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1006/adnd.2001.0858Deformation of Λ hypernuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 78,Table of nuclear electric quadrupole moments

. Atom. Data Nucl. Data Tables 111, 1-28 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adt.2015.12.002Strangeness in nuclear physics

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 88,The authors declare that they have no competing interests.