Introduction

The 65Cu(γ, n)64Cu reaction has important medical and scientific applications [1, 2]. 64Cu is a short-life β+ emitter (

In the last century, laboratories worldwide have conducted experimental studies on the photoneutron reaction of 65Cu using bremsstrahlung (BR) sources [11, 12] and positron annihilation in flight (PAIF) sources [13] using the activation method. Varlamov et al. [14] evaluated the existing 65Cu(γ,n) experimental data, which showed considerable differences. The evaluated and experimental cross sections show that BR and PAIF are close within the low incident γ energy range but differ significantly in the high γ energy range, reflecting systematic errors in the experiment caused by the misclassification of neutron channels [8]. The quasimonochromatic γ-ray source generated by laser Compton scattering provides an opportunity to measure the (γ, n) reaction, which helps distinguish the differences in the existing data.

In this study, the cross sections of the natCu(γ, n) reaction were measured within the giant dipole resonance (GDR) energy region using the SLEGS beamline [15] at the SSRF [16-18]. The 65Cu(γ, n) cross sections were determined via the substitute method via the previously measured 63Cu(γ, n) reaction. Furthermore, neutron capture cross sections for 64Cu were also extracted. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the experimental procedure for the natCu(γ, n) cross sections. Section 3 presents the methods for processing the experimental data of the photoneutron cross section and the results of the quasi-monochromatic and monochromatic cross sections of 65Cu(γ, n) obtained by the subtraction method. Section 4 discusses the discrepancies between the measured data and existing experimental data, as well as the extraction of the radiative neutron capture cross section of 64Cu. Finally, a brief conclusion is given in Sect. 5.

Experiment

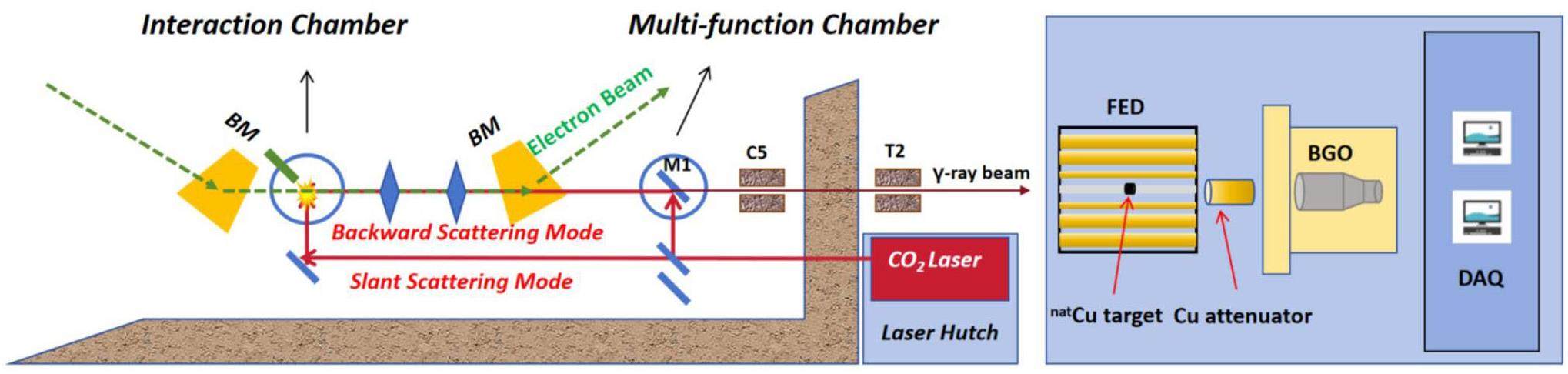

This experiment was performed at the SLEGS beamline station [19] in the SSRF. The beamline uses inverse Compton scattering technology: 3.5 GeV electrons in the SSRF storage ring collide with photons from a 10.64 μm-wavelength, 100 W CO2 laser, generating quasimonochromatic gamma rays with tunable energies from 0.66 to 21.7 MeV. The energy of the γ beam was adjusted in slant-scattering mode with a minimum step of 10 keV. For measurements of the (γ, n) reactions at SLEGS, see Refs. [20-23] for details. A schematic illustration of SLEGS and the corresponding experimental setup are presented in Fig. 1.

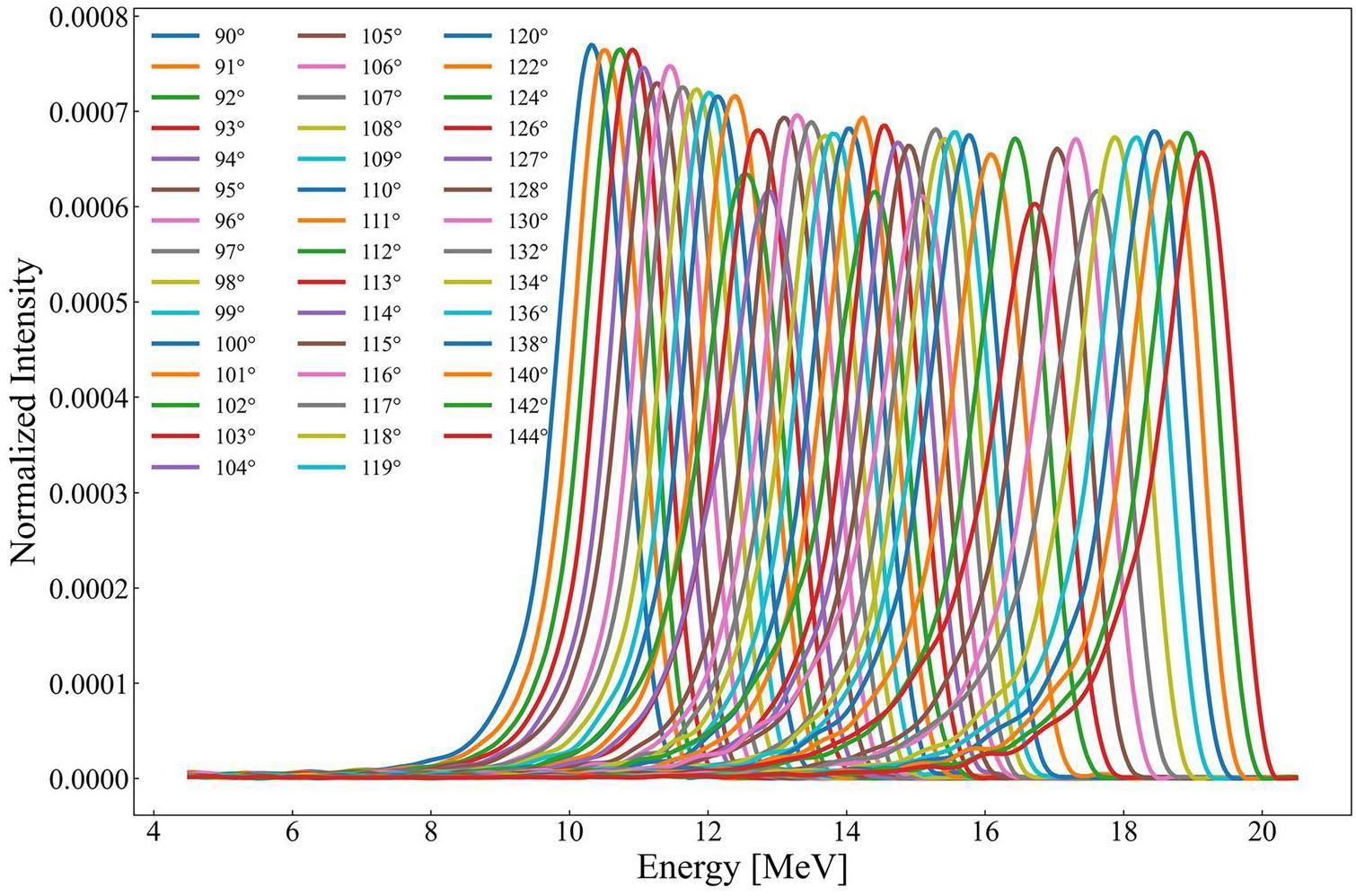

The cross sections for the natCu(γ, n) reaction were measured at 44 energy points ranging from 10.9 MeV (θ = 90°) to 17.8 MeV (θ = 130°). For each angle, the measurement time and neutron statistics were as follows: 2 h with neutron statistics exceeding 1.0 × 104 for θ ≤ 98°, 1 h with neutron statistics exceeding 4.3 × 104 for 99° ≤ θ ≤ 150°, and 0.5 h with neutron statistics exceeding 4.8×104 for θ ≤ 106°. After passing through the collimation system, the laser Compton scattering (LCS) γ beam irradiated the experimental target positioned at the center of the 3He flat efficiency detector (FED) array [24]. The in-beam gamma flux was monitored using a large-volume BGO detector downstream of the FED. The incident γ spectrum was reconstructed using the direct unfolding method combined with a Geant4-simulated detector-response matrix (Fig. 2, see Refs. [25-27] for details).

Targets

The natCu target (3.15 g) was placed in polyethylene target holders and irradiated by LCS γ beams. The alignments of the target and FED with the LCS γ-ray beam were adjusted using a MiniPIX X-ray pixel detector for collimation. The detailed specifications are provided in Table 1.

| Target | Weight (g) | Diameter (mm) | Total thickness (mm) | Measured density (g/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| natCu | 3.15 | 10.00 | 4.48 | 8.69 |

The target holder has a 10-mm in diameter window. Considering that the size of the LCS γ-ray beams was approximately 4 mm in diameter at the target position, a 10 mm diameter window was sufficient for the target to be measured, avoiding the influence of neutrons from polythene.

Measurements

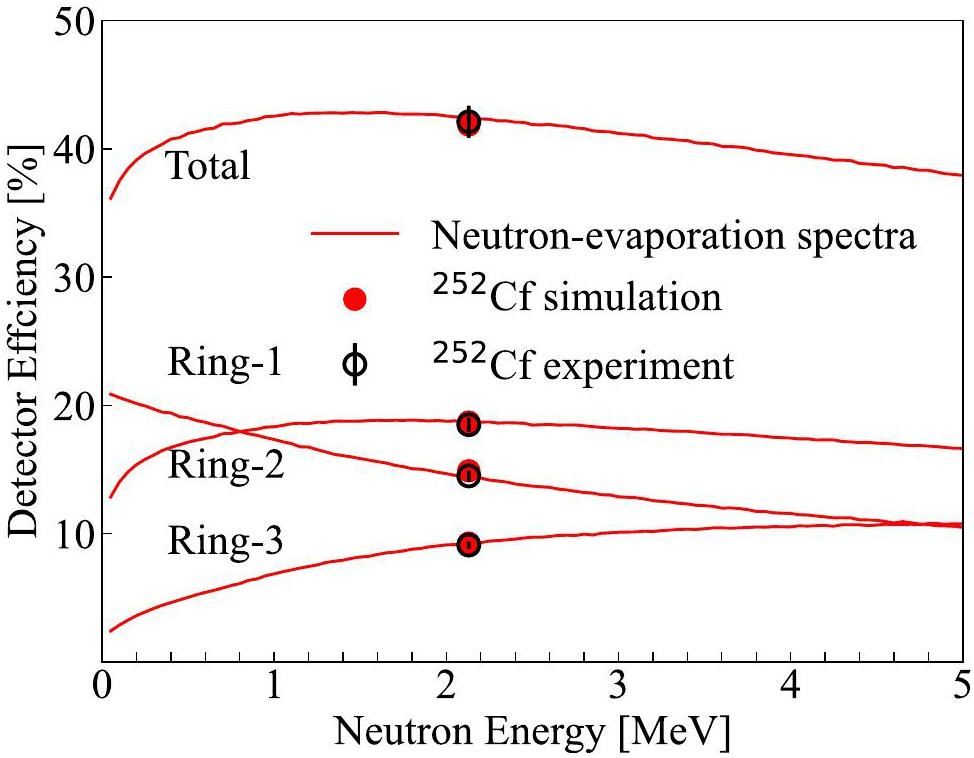

The SLEGS facility features a new FED with 26 proportional counters arranged in three concentric radii within a polyethylene moderator shielded by a 2 mm Cd sheet [23]. The counters, with an effective length of 500 mm and filled with 3He gas at a pressure of 2 atm, were read out through the Mesytec MDPP-16 digitizers and MVME DAQ. Figure 3 shows the efficiency curves of each ring and the total efficiency curve simulated by GEANT4 using a real detector configuration. For the neutron evaporation spectrum, the total detector efficiency increases from 35.64% at 50 keV to 42.32% at 1.65 MeV, and then decreases slowly to 39.05% at 4 MeV [28]. The efficiency calibrated using the 252Cf source is 42.10 ± 1.25%, corresponding to an average neutron energy of 2.13 MeV. In our experiment, we used the ring-ratio technique to obtain the average energy of neutrons produced by the (γ, n) reaction and then estimated the detector efficiency using its calibration curve [29, 30].

Data Analysis and Substitution Measurement Method

Data Analysis method

In the monochromatic approximation, the photoneutron cross section can be expressed by the integral equation [31]:

To solve this unfolding problem, the integral in Eq. (1) is approximated as the summation of each

Substitution Measurement method

In this experiment, the natural Cu target (natCu) has an isotopic abundance of 69.15% for 63Cu and 30.85% for 65Cu. The one-neutron (Sn) and two-neutrons (S2n) separation energies for 63Cu are 10.86 and 19.74 MeV, respectively. And for 65Cu, Sn and S2n become 9.91 MeV and 17.83 MeV, respectively [42-44]. Within the energy range where the one-neutron separation energy thresholds of 63Cu and 65Cu overlap, the FED detector measures neutrons from both the 63Cu(γ, n) and 65Cu(γ, n) reactions as

According to Eq. (7), statistical uncertainty is mainly caused by Nn. Methodological uncertainty arises from the extraction algorithm Nn and deconvolution method incorporating the simulated BGO response matrix. Systematic uncertainty, which is the main source of the total error, includes the γ-flux uncertainty from the copper attenuator, the uncertainty of the target thickness, and the uncertainty of the FED efficiency. Table 2 summarizes the systematic and methodological uncertainties.

| Error Source | Type | Uncertainty |

|---|---|---|

| FED efficiency | Systematic | 3.02% |

| External copper | Systematic | 0.50% |

| Target thickness | Systematic | <0.10% |

| Nn extraction algorithm | Data processing | 2.00% |

| Unfolding method | Data processing | 1.00% |

Results and discussion

65Cu photoneutron reaction cross section

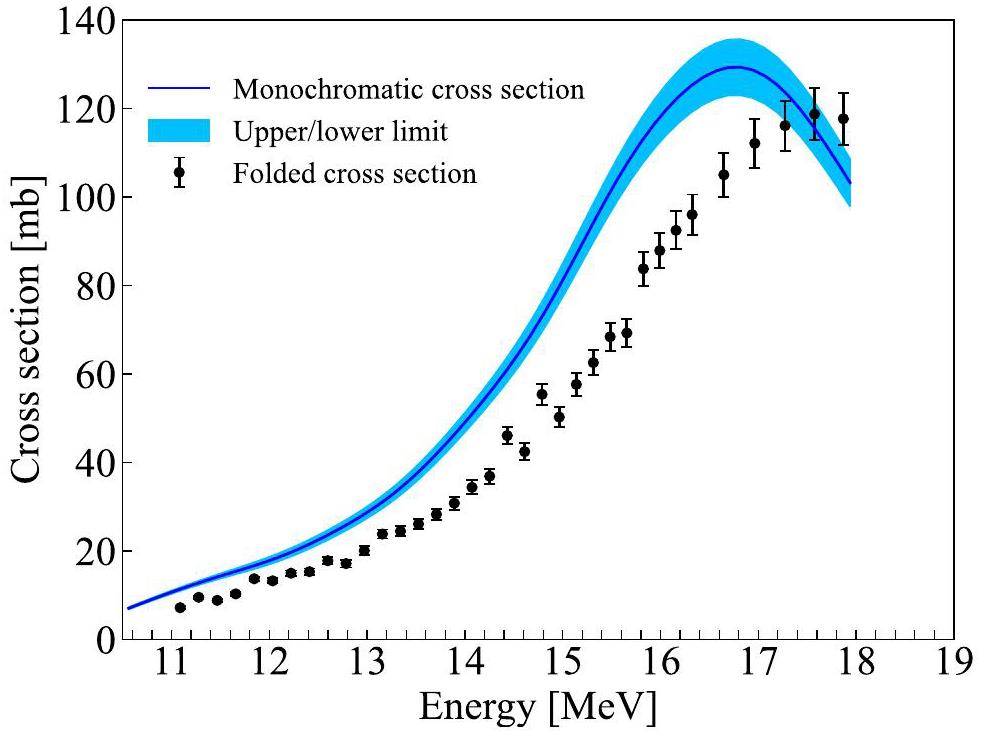

The

| Cross sections (mb) | Statistical uncertainty (mb) | Systematical uncertainty (mb) | Methodological uncertainty (mb) | Total uncertainty (mb) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11.09 | 11.38 | 0.26 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.42 |

| 11.28 | 12.80 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.49 |

| 11.47 | 14.13 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.58 |

| 11.66 | 15.39 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.30 | 0.67 |

| 11.85 | 16.67 | 0.19 | 0.23 | 0.40 | 0.76 |

| 12.03 | 18.07 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.45 | 0.85 |

| 12.22 | 19.69 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.51 | 0.94 |

| 12.41 | 21.54 | 0.19 | 0.33 | 0.59 | 1.03 |

| 12.60 | 23.61 | 0.28 | 0.38 | 0.66 | 1.12 |

| 12.78 | 25.84 | 0.31 | 0.40 | 0.71 | 1.20 |

| 12.97 | 28.29 | 0.31 | 0.46 | 0.79 | 1.29 |

| 13.16 | 31.04 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 0.82 | 1.41 |

| 13.34 | 34.21 | 0.32 | 0.54 | 0.89 | 1.54 |

| 13.53 | 37.85 | 0.33 | 0.57 | 0.95 | 1.70 |

| 13.71 | 41.91 | 0.29 | 0.65 | 1.06 | 1.88 |

| 13.89 | 46.31 | 0.42 | 0.71 | 1.18 | 2.07 |

| 14.07 | 50.93 | 0.43 | 0.78 | 1.30 | 2.27 |

| 14.25 | 55.79 | 0.54 | 0.85 | 1.37 | 2.48 |

| 14.43 | 60.93 | 0.56 | 0.98 | 1.61 | 2.70 |

| 14.61 | 66.59 | 0.45 | 1.01 | 1.62 | 2.95 |

| 14.79 | 72.81 | 0.52 | 1.19 | 1.94 | 3.25 |

| 14.96 | 79.64 | 0.47 | 1.16 | 1.93 | 3.58 |

| 15.14 | 86.86 | 0.51 | 1.34 | 2.21 | 3.95 |

| 15.31 | 94.16 | 0.50 | 1.45 | 2.43 | 4.34 |

| 15.48 | 101.13 | 0.53 | 1.59 | 2.64 | 4.71 |

| 15.66 | 107.55 | 0.51 | 1.65 | 2.75 | 5.07 |

| 15.82 | 113.23 | 0.63 | 1.93 | 3.20 | 5.40 |

| 15.99 | 118.06 | 0.66 | 2.06 | 3.40 | 5.70 |

| 16.16 | 122.15 | 0.68 | 2.20 | 3.62 | 5.97 |

| 16.32 | 125.43 | 0.70 | 2.33 | 3.84 | 6.20 |

| 16.65 | 129.18 | 0.60 | 2.57 | 4.26 | 6.51 |

| 16.96 | 128.71 | 0.60 | 2.78 | 4.77 | 6.58 |

| 17.27 | 123.81 | 0.68 | 2.84 | 4.85 | 6.39 |

| 17.58 | 115.61 | 0.82 | 2.97 | 4.97 | 6.01 |

| 17.87 | 105.68 | 0.81 | 2.98 | 5.03 | 5.52 |

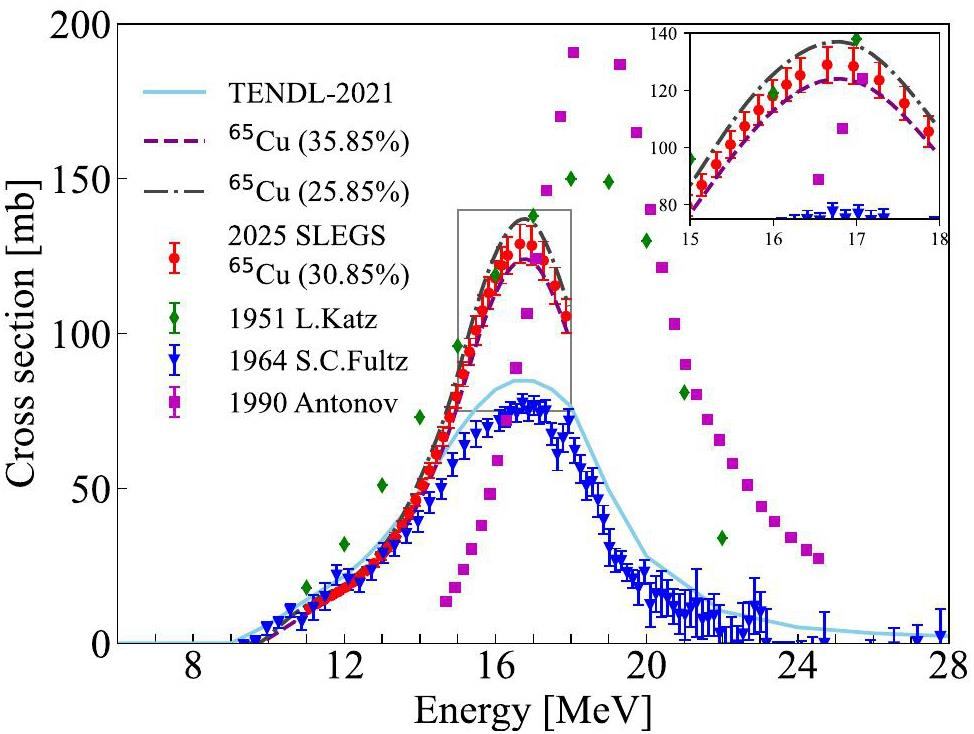

Isotopic abundance variations influence cross sections and cause discrepancies in the results. The photoneutron cross sections changed regularly with alterations in 65Cu abundance. Based on data from the 2025 SLEGS experiment, comparing the cross section of 65Cu at 35.85%, natural abundance (30.85%), and 25.85%, the photoneutron cross sections decreased as the abundance of 65Cu increased (e.g., from 25.85% to 35.85%) and increased as the abundance decreased (see the inset in Fig. 5). This occurs across all energy ranges and is most noticeable near the threshold and peak positions in the cross section distribution. It is suggested that the isotopic abundances in the target material should be determined prior to analysis of the substitution data. The sensitive change in isotopic abundance also suggests that it is capable of adopting an enhanced isotopic target to determine the cross section (γ, n) in addition to the pure isotopic target.

As discussed in Ref. [45], the ratios of the integral cross sections provide a clear indication of the systematic differences among the various data compilations. The integral cross sections in Sn and Smax regions are as follows:

| Ratio relation | σint ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sn~15 MeV | 15 MeV ~S2n | Sn~S2n | |

| 1.04 | 0.68 | 0.80 | |

| 0.92 | 0.61 | 0.69 | |

| 1.49 | 1.04 | 1.21 | |

| 0.23 | 0.77 | 0.68 | |

64Cu radiative neutron capture cross section

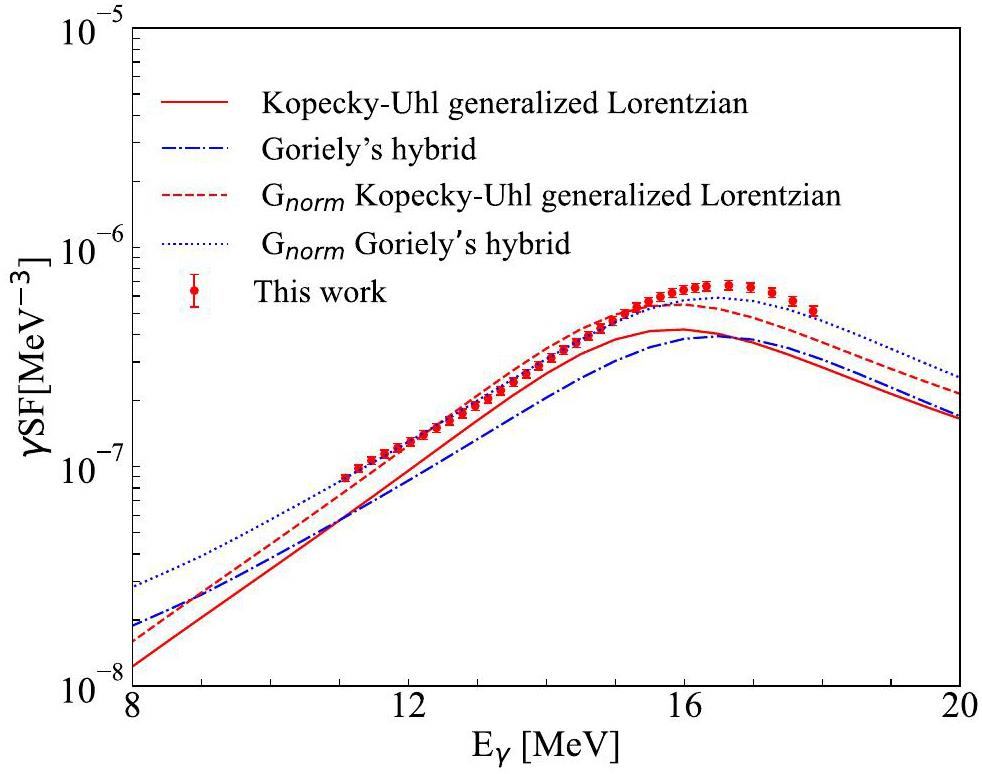

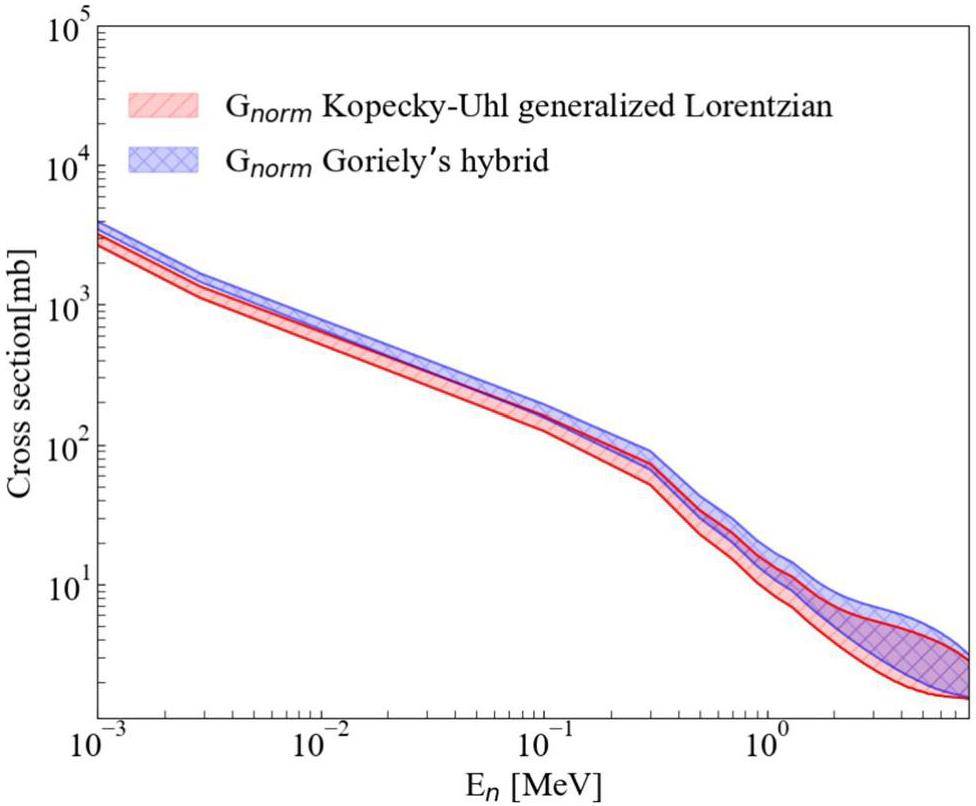

The gamma strength function (γSF) [47] is used to describe the average probabilities of gamma decay and absorption in nuclear reactions, and is an important parameter for characterizing the nuclear reaction process. When research involves reactions with gamma rays, such as reactions (n, γ) and (γ, n), the precision of γSF is particularly crucial. According to the principle of detailed balance [48] and generalized Brink assumption [49-51], it is believed that the upward

Summary

The reaction cross sections of natCu(γ, n) were measured in the incident energy range of 11.09 to 17.87 MeV using the 3He FED detector array developed by SLEGS. Based on the measured photoneutron cross section data and the previously measured results for 63Cu(γ, n) at SLEGS, the reaction cross sections of 65Cu(γ, n)64Cu were obtained using the cross section substitution method. Compared with existing experimental data, the reliability of this method was demonstrated, providing a new approach for photoneutron cross section measurements. Given the extensive application of 64Cu in medical fields such as nuclear medicine imaging and tumor therapy, clarifying the existing discrepancies in the reaction cross-sections of the 65Cu(γ, n)64Cu reaction is likely to play an important role in these fields. The sensitivity of the isotopic abundance change in the natural copper target shows that the enhanced purity of the specific isotope could be used to measure its (γ, n) cross section via the substitution measured in this work. The experimentally constrained γSF of 65Cu was extracted from the 65Cu(γ, n)64Cu cross section distribution. In addition, the cross section curve of its inverse reaction, 64Cu(n, γ), was calculated, which provides a new approach to the extraction of cross sections (n, γ) from some unstable nuclides.

Production of medical radioisotope 64Cu by photoneutron reaction using ELI-NP γ-ray beam

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 27, 96 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-016-0094-6.A data-based photonuclear simulation algorithm for determining specific activity of medical radioisotopes

, Nucl. Sci. Tech. 27, 113 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-016-0111-9.Clinical applications of radiolabeled peptides for PET

. Semin. Nucl. Med. 47, 493 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2017.05.007.An overview of PET radiochemistry, part 2: Radiometals

. J. Nucl. Med. 59, 1500 (2018). https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.117.190801.Recent advances in 64Cu/67Cu-based radiopharmaceuticals

. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 9154 (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24119154.Radioisotope production for medical applications at ELI-NP

. Rom. Rep. Phys. 68, 847 (2016).The emerging role of copper-64 radiopharmaceuticals as cancer theranostics

. Drug Discov. Today 23, 1489 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2018.04.002.Diagnostic accuracy of 64copper prostate-specific membrane antigen positron emission tomography/computed tomography for primary lymph node staging of intermediate-to high-risk prostate cancer: our preliminary experience

. Urology. 106, 139 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2017.04.019.64Cu-PSMA-617 PET/CT imaging of prostate adenocarcinoma: first in-human studies

. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 31, 277 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1089/cbr.2015.1964.Radiopharmaceuticals labelled with copper radionuclides: clinical results in human beings

. Curr. Radiopharm. 11, 22 (2018). https://doi.org/10.2174/1874471011666171211161851.Gamma-neutron cross sections

. Phys. Rev. 80, 1062 (1950). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.80.1062.Studies of photonuclear reactions with emission of α particles in the region of the giant dipole resonance

. Sov. J. Nucl. Phys. 51, 193 (1990).Photoneutron cross sections for natural Cu, Cu63, and Cu65

. Phys. Rev. 133,The SLEGS beamline of SSRF

, Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 111 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01469-3Overview of SSRF phase-II beamlines

, Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 137 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01487-1Commissioning and First Results of the SSRF Phase-II Beamline Project

, J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2380,Commissioning of laser electron gamma beamline SLEGS at SSRF

, Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 87 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01076-0Simulation and test of the SLEGS TOF spectrometer at SSRF

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34(3), 47 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01194-3Interaction chamber for laser Compton slant-scattering in SLEGS beamline at Shanghai Light Source

, Nucl. Instrum. Methods phys. Res. A 1033,Gamma spot monitor at SLEGS beamline

, Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 1068,Effective extraction of photoneutron cross-section distribution using gamma activation and reaction yield ratio method

, Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 170 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01330-zMeasurement of 59Co(γ, n)58Co using a new flat-efffciency neutron detector at SLEGS

, Phys. Rev. C 111,The day-one experiment at SLEGS: systematic measurement of the (γ, 1n) cross sections on 197Au and 159Tb for resolving existing data discrepancies

, Science Bulletin (2025). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scib.2025.05.037Energy profile of laser Compton slant-scattering γ-ray beams determined by direct unfolding of total-energy responses of a BGO detector

, Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 1063,Implementation of the n-body Monte-Carlo event generator into the Geant4 toolkit for photonuclear studies

, Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 849, 49 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2017.01.010Geant4—a simulation toolkit

, Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 506, 250 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(03)01368-8Design and simulation of 4π flat-efficiency 3He neutron detector array

, Nucl. Tech. (in Chinese) 43, 9 (2020). https://doi.org/10.11889/j.0253-3219.2020.hjs.43.110501Photoneutron cross sections for 90Zr, 91Zr, 92Zr, 94Zr, and 89Y

, Phys. Rev. 162, 1098 (1967). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.162.1098Photoneutron cross sections for Au revisited: measurements with laser Compton scattering γ-rays and data reduction by a least-squares method

, J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 48, 834 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1080/18811248.2011.9711766Photoneutron cross sections for 13C

. Phys. Rev. C 19, 1684 (1979). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.19.1684New measurement of thick target yield for narrow resonance at Ex=9.17 MeV in the 13C(p,γ)14N reaction

. Chin. Phys. B 28,Study on γ-ray source from the resonant reaction 19F(p,αγ)16O at Ep=340 keV

. Chin. Phys. B 29,The unfolding of continuum γ-ray spectra

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 374, 3 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-9002(96)00197-0Direct neutron-multiplicity sorting with a flat-efficiency detector

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 871, 135 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2017.08.001Photoneutron cross-section measurements in the 209Bi(γ,xn) reaction with a new method of direct neutron-multiplicity sorting

. Phys. Rev. C 96,Updated neutron-multiplicity sorting method for producing photoneutron average energies and resolving multiple firing events

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 1019,Verification of detailed balance for γ absorption and emission in Dy isotopes

, Phys. Rev. C 98,Response functions of a 4 π summing gamma detector in β-Olso method

, Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 68 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01058-2Measurements of 27Al(γ, n) reaction using quasi-monoenergetic γ beams from 13.2 to 21.7 MeV at SLEGS

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 36, 66 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-025-01662-yThe AME 2020 atomic mass evaluation (I). Evaluation of input data, and adjustment procedures

, Chin. Phys. C 45,The AME 2020 atomic mass evaluation (II). Tables, graphs and references

, Chin. Phys. C 45New measurement of 63Cu(γ,n)62Cu cross-section using quasi-monoenergetic γ-ray beam

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 36, 34 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01631-xReliability of (γ, 1n),(γ, 2n), and (γ, 3n) cross-section data on 159Tb

, Phys. Rev. C 95,TENDL-2021

, https://tendl.web.psi.ch/tendl_2021/gamma_html/gamma.html, (2021).Test of gamma-ray strength functions in nuclear reaction model calculations

. Phys. Rev. C 41.5, 1941 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.41.1941Photoneutron cross sections for Ni isotopes: Toward understanding (n,γ) cross sections relevant to weak s-process nucleosynthesis

. Phys. Rev. C 98,Photoneutron cross sections for samarium isotopes: Toward a unified understanding of (γ,n) and (n,γ) reactions in the rare earth region

. Phys. Rev. C 90,TEFAL-2.0, Making ENDF-6 nuclear data libraries with TALYS

, https://nds.iaea.org/talys/tutorials/tefal.pdf (2023)RIPL-reference input parameter library for calculation of nuclear reactions and nuclear data evaluations

. Nucl. Data Sheets. 110, 3107 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nds.2009.10.004Simple empirical E1 and M1 strength functions for practical applications

. Phys. Rev. C 99,Spin scissors mode and the fine structure of M1 states in nuclei

. Nucl. Phys. A 872, 1 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2011.09.016Chun-Wang Ma and Hong-Wei Wang are editorial board members for Nuclear Science and Techniques and was not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.