Introduction

The synthesis of new nuclides has always been a hot topic in the field of nuclear physics, and is essential for exploring the existence limits of nuclei, exotic nuclear structures, and nuclear forces. According to theoretical predictions, a large number of nuclides are yet to be discovered [1], especially in superheavy and neutron-rich regions. However, there is still a blank area on the neutron-deficient side with Z>82. To date, the different methods used to produce unknown nuclei include nuclear fission, projectile fragmentation, fusion evaporation, and light particle reactions [2, 3], which are applicable across different regions of the nuclear chart. Most neutron-deficient nuclei are synthesized via fusion-evaporation reactions. The study of heavy-ion fusion reactions at energies near the Coulomb barrier, involving nuclear structure effects, barrier distribution, and nucleon transfer, is beneficial for exploring the synthesis mechanism of neutron-deficient nuclei [4-7] and to provide the optimal projectile-target combinations for the experiments.

The synthesis of neutron-deficient nuclei is crucial for the investigation of proton halos, emergence of new magic numbers, β-delayed fission, proton decay mode, and shape evolution [8-13]. The Pu isotopes are in the actinide region, and some neutron-deficient Pu isotopes have not yet been discovered. Currently, 21 Pu isotopes have been experimentally synthesized. The earliest experiment can be traced back to 1946 at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) [14], where the target 238U was irradiated with neutrons and 239Pu was produced by successive β decays. Over the next 30 years, LBNL continued to accelerate light particles, such as 3,4He and 2H, bombarding the U target, and 231-241Pu were successively produced [15-21]. In addition, for the neutron-deficient region, 207,208Pb target was impinged by 24,26Mg beam in the laboratory at JINR, isotopes 228-230Pu were generated in the 4n and 5n evaporation channels [22, 23], and 227Pu was produced in the reaction 192Os(40Ar, 5n)227Pu at the Institute of Modern Physics [24]. In the neutron-rich region, 242-245Pu and 247Pu isotopes were produced by neutron capture reactions on actinides targets [25-29]. Isotope 246Pu was detected in the debris from the thermonuclear test [30]. The fusion-evaporation reaction is more suitable and promising for the synthesis of more neutron-deficient unknown Pu isotopes.

Over the past few decades, various models have been developed to describe the fusion reactions. Macroscopic models can describe the evolution of multiple degrees of freedom, including charge and mass asymmetry, elongation of a mononucleus, and surface deformations, such as the dinuclear system (DNS) model [31-36], Langevin equations [37-39], two-step model [40], fusion by diffusion (FBD) model [42, 41], empirical model [43, 44], and dynamical cluster-decay model [45, 46]. For self-consistent consideration of the dynamical effects, the time-dependent Hartree-Fock (TDHF) model [47-49], as a microscopic quantum transport theory based on the mean field, can reasonably predict the fusion cross sections. The isospin-dependent quantum molecular dynamics (IQMD) model [6, 51], as a semi-classical microscopic dynamics transport model that includes two-body collision and phase-space constraint, has been successful in investigating neck dynamics and fusion mechanisms.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, the framework of the IQMD model is introduced. In Sect. 3, the calculated results and discussions are presented. Finally, a summary is presented in Sec. 4.

The Model

Based on the conventional QMD model, the interaction potential, nucleon’s fermionic nature, and two-body collision were improved in the IQMD. In this model, the nucleon i is described by a coherent state of a Gaussian wave packet,

The phase space density distribution of nucleon i can be derived from the wave function through the Wigner transformation, expressed as

| α (MeV) | β (MeV) | γ | gsur (MeV⋅fm2) | gτ (MeV) | η | κs (fm2) | ρ0(fm-3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -356 | 303 | 7/6 | 7.0 | 12.5 | 2/3 | 32 | 0.08 | 0.165 |

The long-range Coulomb potential is also a function of the density distribution:

The kinetic energy of the system is calculated by

The wave function of the system is adopted as the direct product of the single-particle wave functions as follows:

If

To compensate for the short-range repulsion effect of the nuclear force, two nucleons satisfying the following kinematic conditions are scattered:

To establish the initial conditions of the system, the Skyrme-Hartree-Fock method was applied to provide the density distribution of protons and neutrons in both the projectile and the target nuclei. Subsequently, the Monte Carlo method was employed to sample the coordinates and momenta of nucleons. The sampling range of the momentum was from zero to the Fermi momentum.

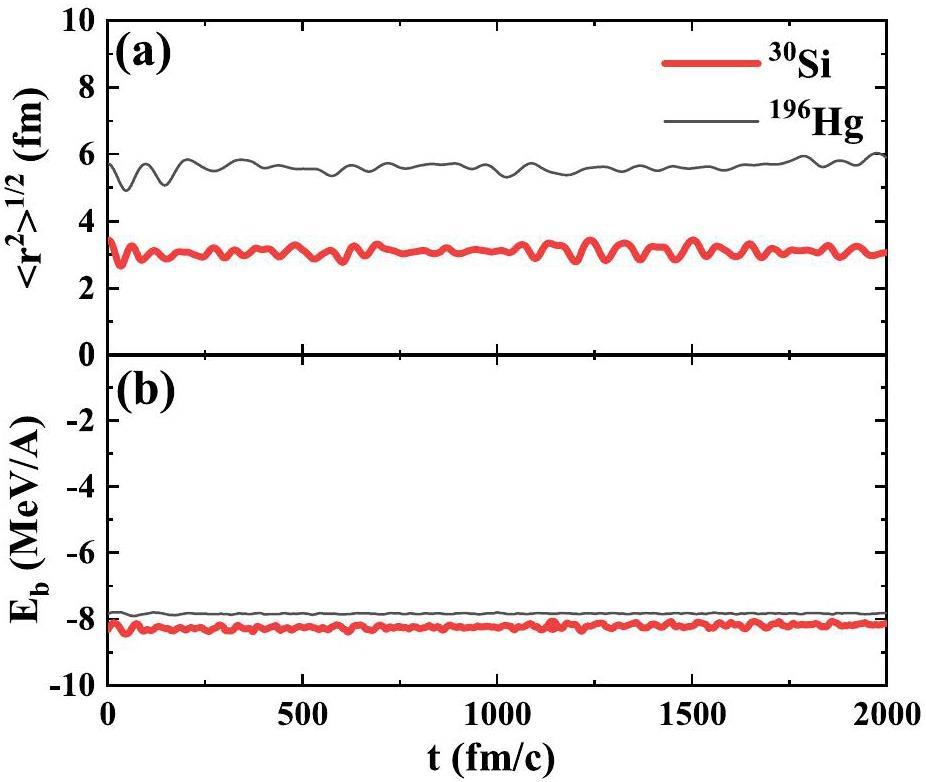

The stability of a nucleus is checked by undergoing time evolution over 2000 fm/c within its self-consistent mean field. At each time step, the root-mean-square radius and binding energy of the nucleus were compared with the experimental values.

The fusion cross section is calculated as follows:

To judge the fusion event, the event is regarded as a fusion event when the distance between two nuclei is less than 3 fm and the mass of the largest cluster formed is close to the mass of the compound nucleus. As for the determination of a cluster, if the relative distance between two nucleons is less than 3 fm, and the relative momentum is less than 0.25 GeV/c, these nucleons are considered as a cluster.

The interaction potential between the projectile and target is calculated by subtracting the energies of the target and projectile from the total energy of the system, which is expressed as

Results and discussions

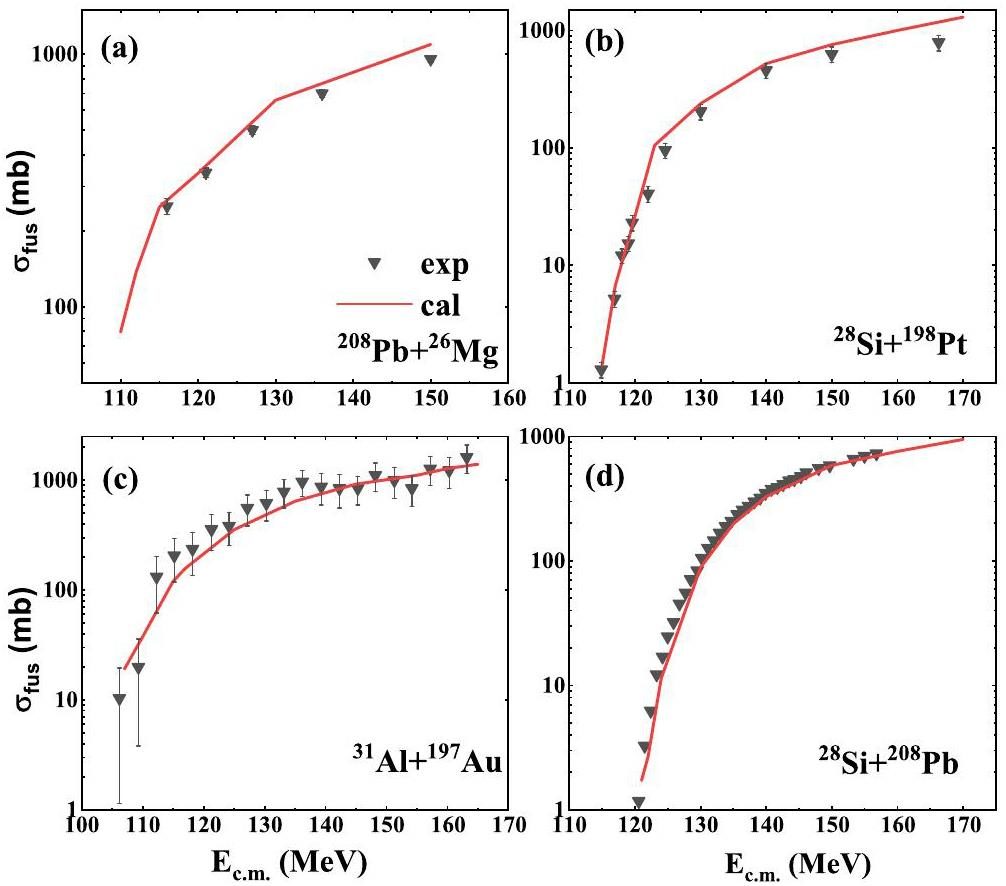

To verify the validity of the IQMD model for describing the fusion reaction, the fusion cross sections were calculated in the reactions of 208Pb+26Mg, 28Si+208Pb, 31Al+197Au, and 28Si+198Pt, as shown in Fig. 2. All compound nuclei in these reactions were approximately Z=94. The calculated results show a satisfactory agreement with the experimental data [56-59] for both the sub-barrier and above-barrier energies. Within a certain energy range, the corresponding fusion cross section increased with increasing incident energy. The fusion cross sections at low energy in 208Pb+26Mg reaction are larger than those in 28Si+208Pb, due to the stronger Coulomb repulsion in the latter reaction. Similarly, 31Al+197Au reaction has greater fusion cross sections than those in 28Si+198Pt. These results indicate that Coulomb repulsion plays a substantial role in fusion reactions.

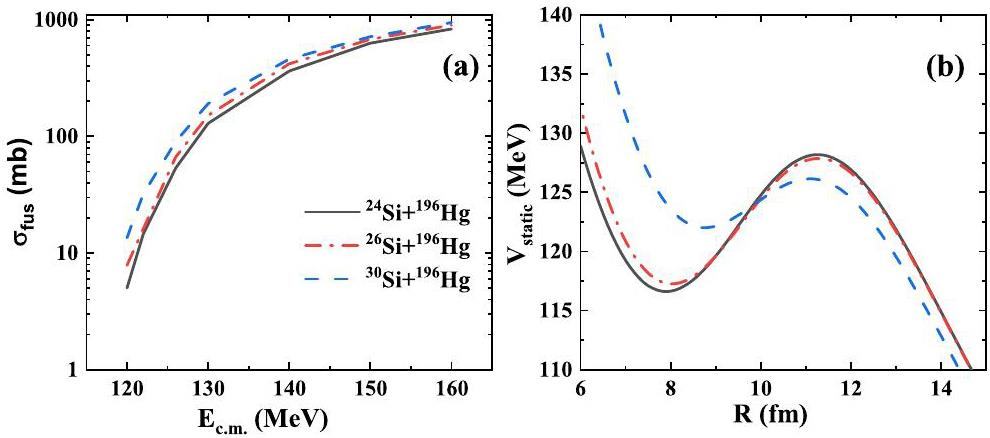

In the following work, systems of 24,26,30Si+196Hg were chosen to investigate the isospin effect on the fusion reaction. In Fig. 3, the fusion cross sections and corresponding static interaction potentials in the three reactions are illustrated. Notably, the fusion cross-section in the reaction with a more neutron-rich beam is larger. To explain this phenomenon, we can analyze it in terms of interaction potential. A sudden approximation is made to calculate the static interaction potential, which means that the densities of both the projectile and the target remain unchanged. Because the projectile and target are oblate, the directional effect on the static barriers should be considered. Hence, a random rotation for the projectile and target was made at the initial time for each event; then, we averaged the static barriers over a number of events. The isospin effect on the fusion cross section can be roughly understood by analyzing the static barrier. The static fusion barrier in the reaction with 30Si beam exhibited the lowest height and narrowest width, leading to the greatest likelihood of overcoming the barrier.

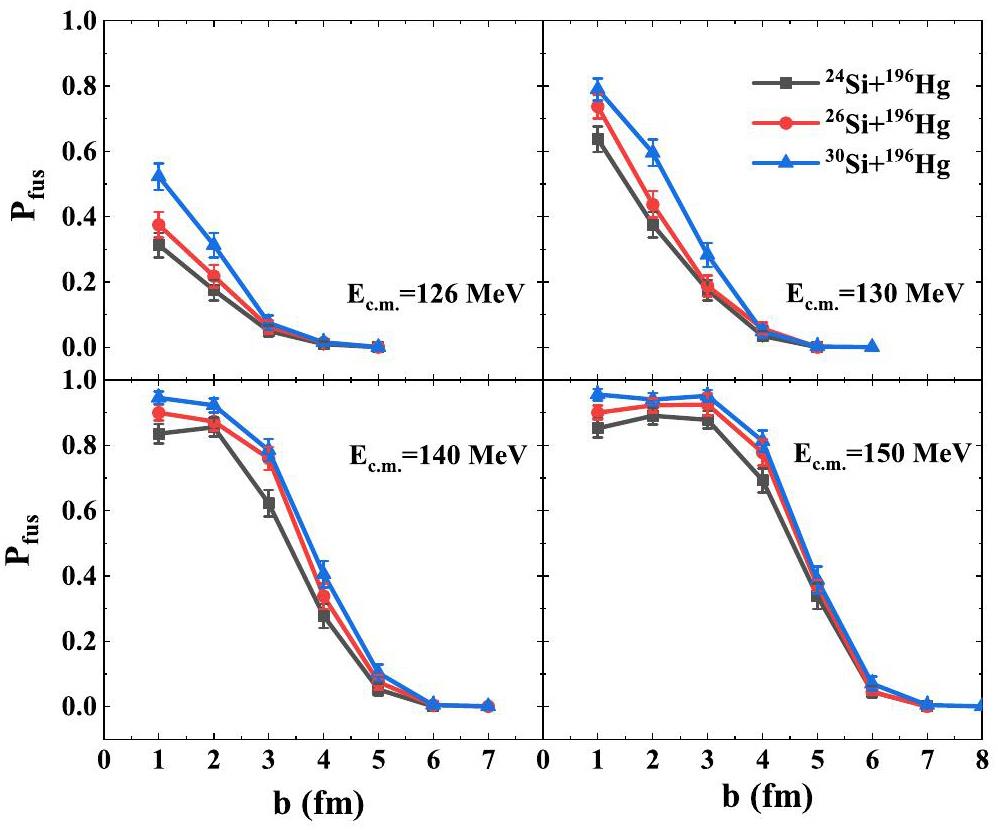

The fusion process exhibited different characteristics for the various impact parameters. In Fig. 4, the fusion probability with respect to the impact parameter in reactions 24,26,30Si+196Hg at different incident energies is presented.

It is evident that the fusion probability decreased as the impact parameters increased. This trend primarily arises from the influence of the rotational energy, which increases progressively with increasing impact parameters. Consequently, the reduction in the radial relative kinetic energy leads to a decrease in the fusion probability. In addition, the reaction mechanism transitions from the fusion reaction to the multinucleon transfer process and quasi-elastic scattering with increasing impact parameter; therefore, the competition among these mechanisms leads to a decrease in fusion probability. It can be observed that the neutron-rich system exhibits a higher fusion probability than a neutron-deficient system. This indicates that the fusion probability in neutron-rich systems is higher regardless of the impact parameters. It is worth noting that even at a sub-barrier energy of Ec.m.=126 MeV, the fusion probability is nonnegligible.

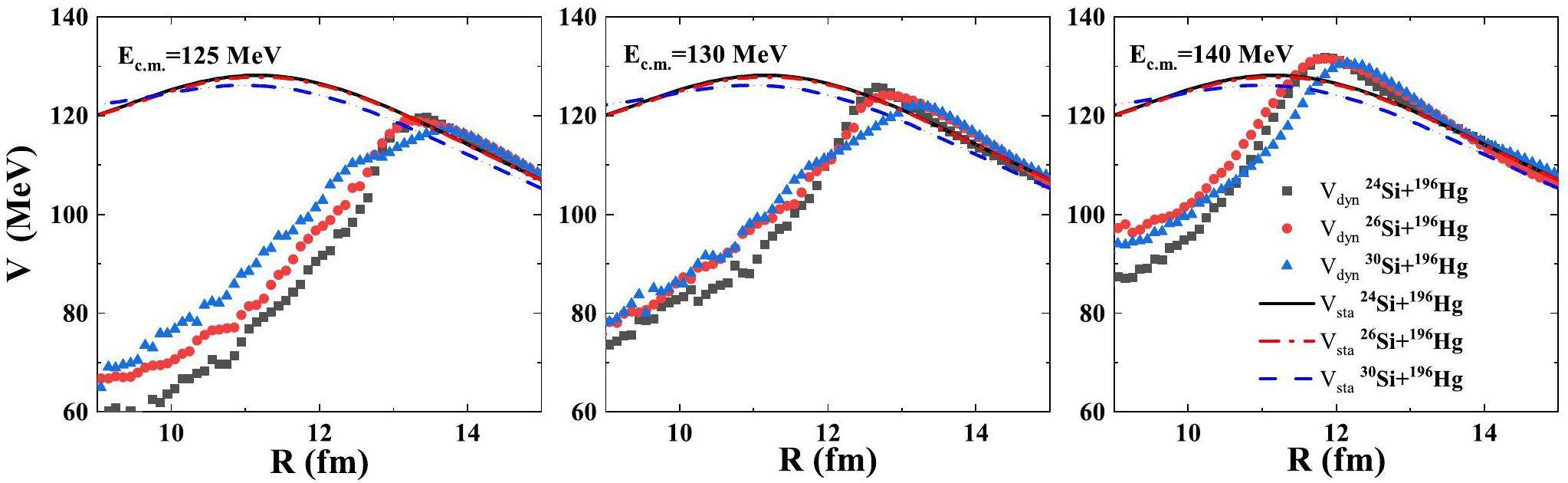

The fusion reaction is a dynamic process involving a large number of nucleon transfers; thus, the impact of the dynamical interaction potential should be considered. The dynamic interaction potential between two nuclei depends not only on the reaction system but also on the incident energy. In Fig. 5, the dynamical and static interaction potential in 24,26,30Si+196Hg reactions at different energies are shown. It can be found that the dynamical barrier decreases with decreasing incident energy. That is attributed to the fact that the interaction time between the two nuclei is longer at a lower incident energy, giving the nucleons more time to adjust their density distribution to reach the lowest potential state. This indicates that sub-barrier fusion involves a process of passing over the barrier rather than the tunnelling effect. Similar to the static barrier, the neutron-rich system exhibits a lower dynamic barrier. As the incident energy increased, the dynamic barriers first approached the static barriers and then surpassed them. The same phenomenon has been described in Ref. [62]. Compared to static barriers, dynamic barriers appear at longer distances.

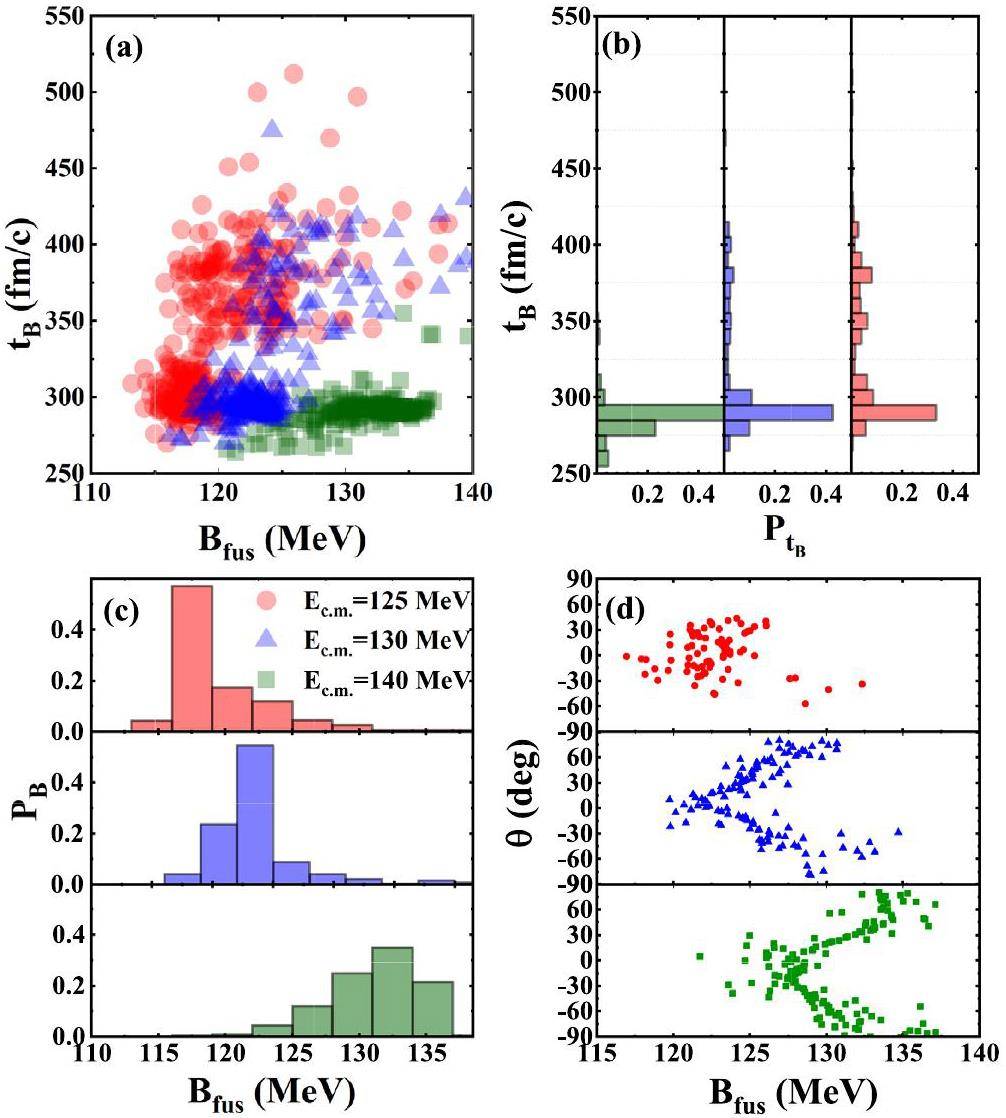

Owing to the effect of the nuclear structure quantities, such as the deformation of nuclei, the dynamic barrier and its moment are distributed within a certain range. Figure 6 (a) shows the moment when the dynamical barrier appears in 30Si+196Hg reaction at different energies. The distributions of the dynamic barrier and its moment are shown in Fig. 6 (c) and (b), respectively. It can be seen that at the sub-barrier incident energies of Ec.m.=125 and 130 MeV, most events are concentrated around t=290 fm/c. However, some events exhibit a longer duration and disperse at approximately 375 fm/c at a lower energy. The dispersion phenomenon gradually disappears as the incident energy increases.

This indicates that the fusion process takes a longer time to exchange nucleons between the projectile and target in some events. As the incident energy increased, the barrier distribution gradually shifted to a higher-barrier region. Hence, the dynamic barrier is larger at higher incident energies, as shown in Fig. 5. The effect of the barrier height on the orientation of the target is shown in Fig. 6(d). θ denotes the angle between the symmetry axis of the target and collision direction. It can be found that the fusion barrier is significantly higher when the target is in the belly orientation, which is the same as described in the Ref. [61]. At Ec.m.=125 MeV, the fusion barriers are predominantly distributed around the range from -45° to 45°. With increasing incident energy, fusion reaction events can also occur in the belly orientation because the incident energy is sufficiently high to overcome the Coulomb barrier in that orientation.

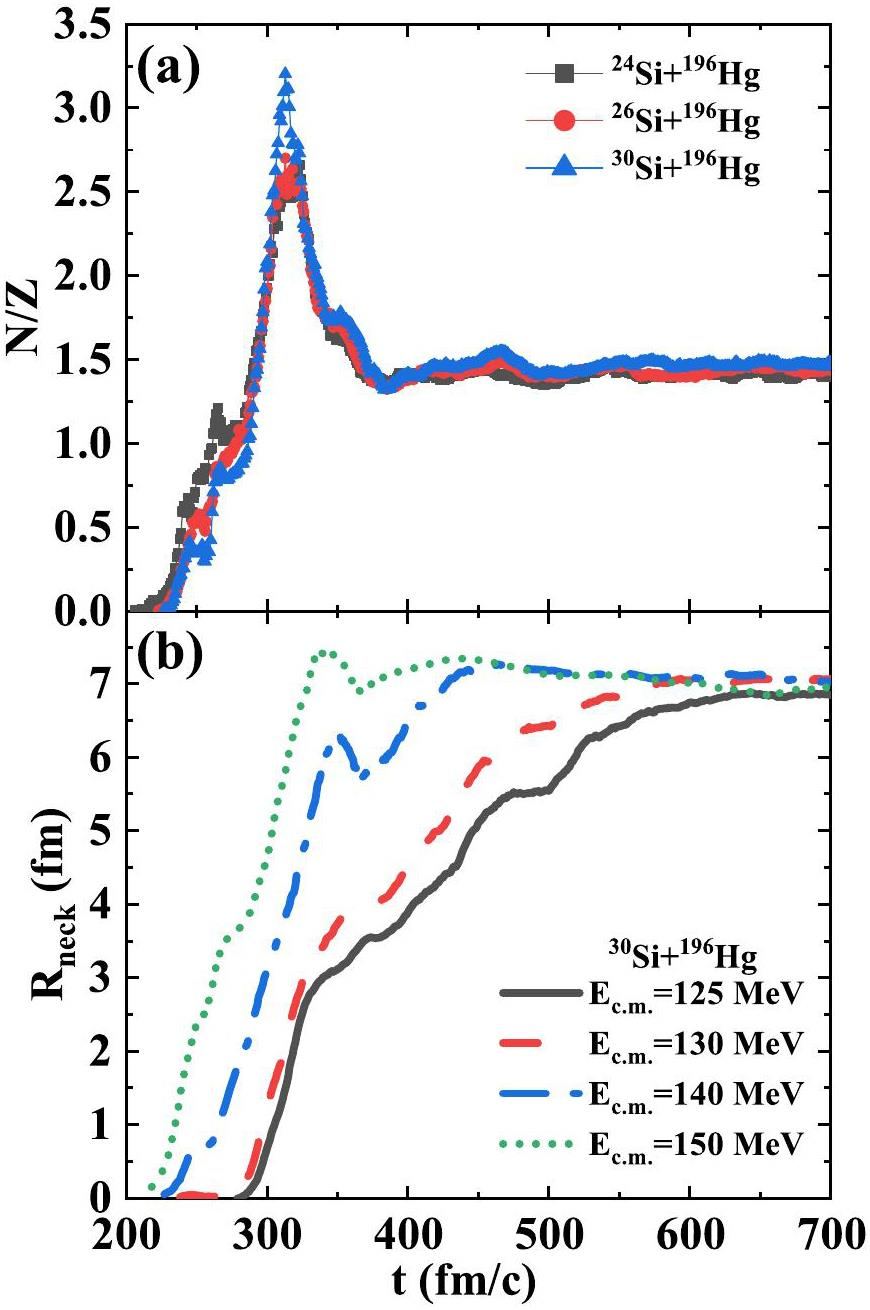

Neck formation is advantageous for nucleon transfer and fusion. In the IQMD model, the neck region is defined as a cylinder whose axis is along the line connecting the centroids of the two nuclei with a length of 4 fm, and whose lowest density at the center of mass is at least 0.02/fm3. The width of the cylinder was defined as the neck radius. In Fig. 7 (a), the time evolution of the N/Z ratio in the reactions 24,26,30Si+196Hg at Ec.m.=140 MeV is shown. It can be observed that the N/Z ratio grows rapidly to a peak at approximately t=300 fm/c, then decreases, and eventually approaches the N/Z ratio of the compound nucleus. The increase in N/Z at the early stage is because the long-range Coulomb repulsion causes protons to move away from the neck region. As the projectile and target further overlap with time, more protons are transferred into the neck region, leading to a decrease in N/Z ratio. It can be found that the peak value of N/Z ratio is the largest in the reaction 30Si+196Hg, indicating that neutrons flow to the neck more easily in neutron-rich system.

To investigate the growth of neck size, the time evolution of the neck radius at different energies is shown in Fig. 7(b)]: It can be noticed that the neck appears earlier and grows faster at a higher incident energy. In contrast, it takes longer to reach the size of the compound nucleus at a lower energy. This is because more time is required to exchange nucleons and adjust the density distribution to decrease the dynamic barrier.

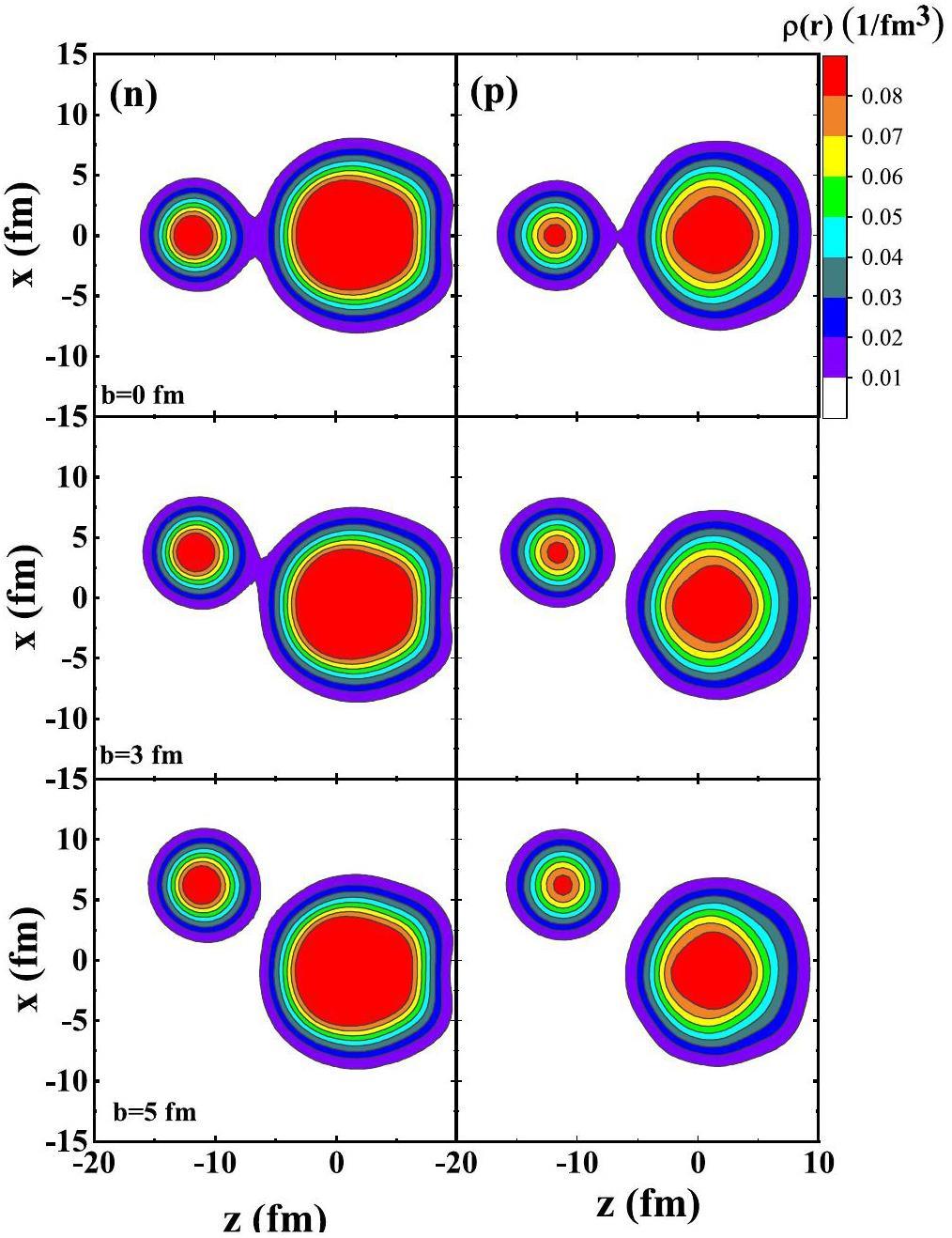

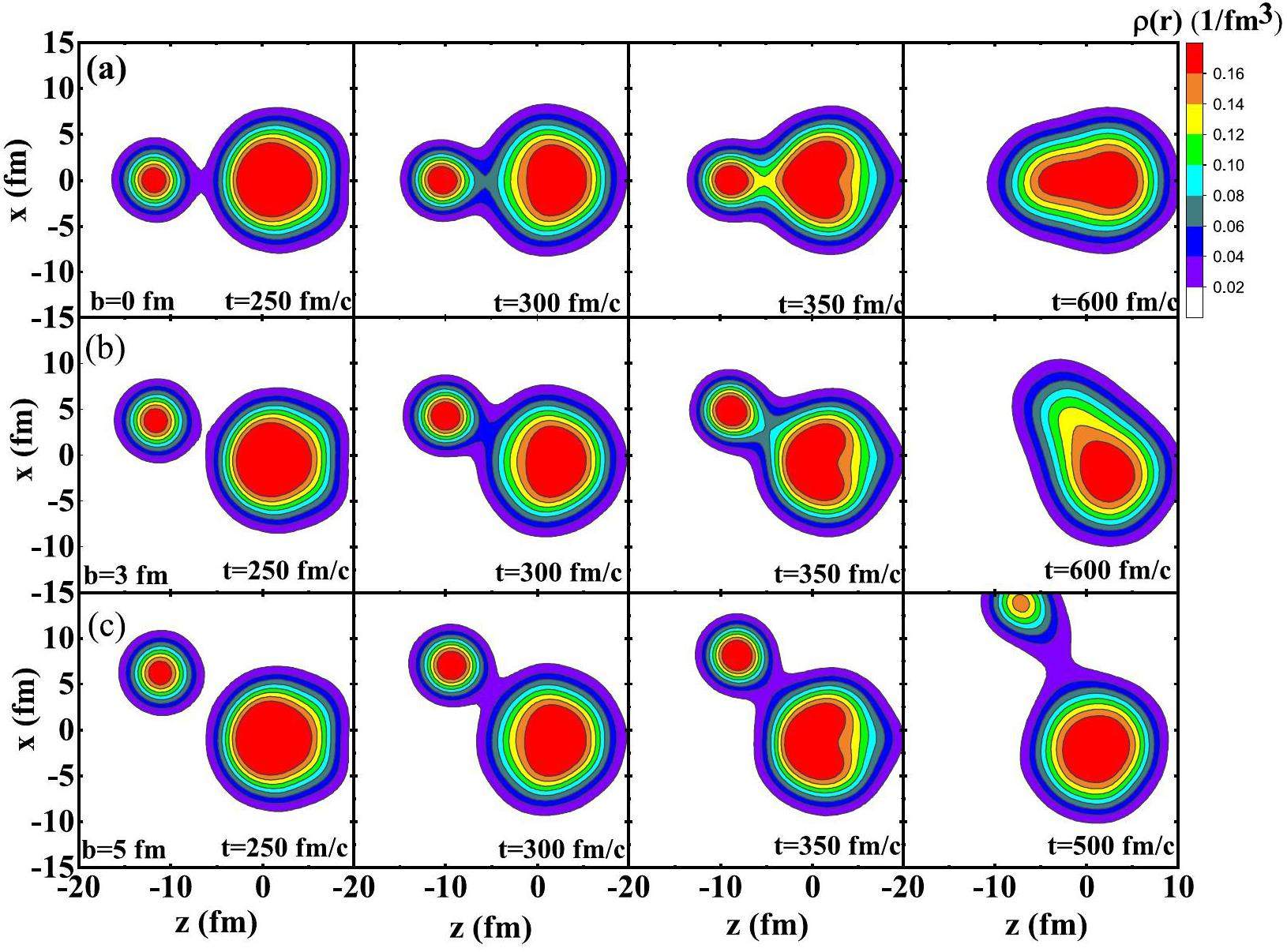

To compare proton transfer with neutron transfer for analyzing the N/Z ratio in the neck region, Fig. 8 shows the neutron and proton density distribution in 30Si+196Hg reaction at Ec.m.=140 MeV for different impact parameters. It can be seen that the neck region is larger at b=0 compared to that at higher impact parameters. As the impact parameter increased, the neck gradually disappeared, indicating that the neck grew faster at lower impact parameters. Compared to the proton density distribution, the neck region for neutrons is larger, meaning that neutrons transfer more quickly than protons during the evolution process, leading to a high N/Z ratio in the neck.

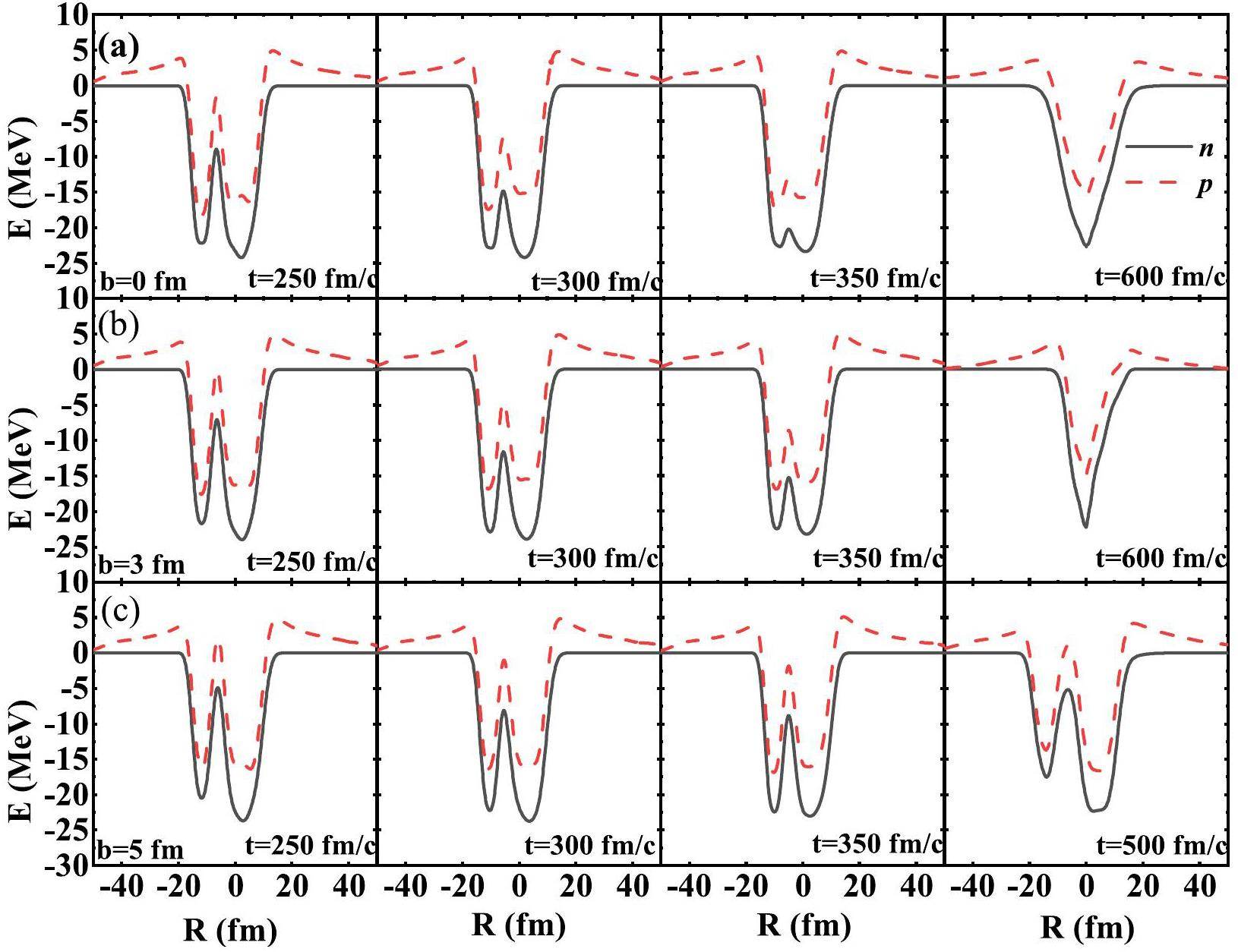

To study the motion trends of nucleon during its transfer processes, the single-particle potential in 30Si+196Hg reaction at Ec.m.=140 MeV under different impact parameters, as shown in Fig. 9. At b=0, we find that the single-particle potential barrier decreases with time and consequently disappears at t=350 fm/c, which indicates that the nucleon transfer between the projectile and target is easier at a lower impact parameter. However, at b=5 fm, the barrier exists all the time, decreases first, and gradually increases as the two nuclei separate; thus, the nucleon transfer becomes obstructed. In addition, the single-particle potential barrier was higher at larger impact parameters at the same time.

The density distribution can be used to analyze the reaction mechanism, which is affected by the single-particle potential. The time evolution of density distribution in 30Si+196Hg reaction is shown in Fig. 10. One can notice that The neck region was smaller with a larger impact parameter at the same time. In addition, the neck grows slower under larger impact parameters, and the neck area decreases and tends to disappear at b=5 fm, indicating that the harder it is for nucleons to transfer, the smaller is the neck area. Comparing the density distribution and single-particle potential, the disappearance of the single-particle potential barrier can promote the fusion event, and the increase in the single-particle potential barrier can prevent nucleon flow and separate the two fragments.

Conclusion

The fusion mechanism to synthesize neutron-deficient Pu isotopes is investigated in the reactions 24,26,30Si+196Hg by the IQMD model. The calculated fusion cross sections agreed reasonably well with the available experimental data. The fusion cross sections in the reaction with more neutron-rich beams are larger owing to the lower static and dynamical barriers. The fusion probability decreases with an increasing impact parameter and is larger in the reaction with a more neutron-rich beam.

The dynamical barrier is reduced with decreasing incident energy, which explains the fusion enhancement at the sub-barrier energy. As the incident energy increases, the dynamic barriers first approach the static barriers and then surpass them, and the dynamic barrier distribution gradually shifts to a higher barrier region. The time distribution of the appearance of dynamical barriers is wider at a lower incident energy, indicating that the fusion process takes a longer time to exchange nucleons. The fusion barrier was significantly higher when the target was oriented belly.

The neck dynamics of fusion reactions were studied. The peak value of N/Z ratio in the neck region is the highest in the reaction 30Si+196Hg, indirectly leading to a lowest dynamical barrier. The growth of the neck radius was slower at a lower incident energy. Comparing with the proton density distribution, the neck region for neutron is larger, meaning that neutrons transfer more quickly than protons, leading to a high N/Z ratio in the neck.

The single-particle fusion barrier decreases with time and finally disappears at a lower impact parameter; therefore, the nucleon transfer between the projectile and target is easier. The disappearance of single-particle potential barrier can promote the fusion events.

Nuclear mass table in deformed relativistic Hartree–Bogoliubov theory in continuum, II: Even-Z nuclei

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 158,Discovery of the thallium, lead, bismuth, and polonium isotopes

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 99, 365 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adt.2012.01.005Discovery of the astatine, radon, francium, and radium isotopes

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 99, 497-519 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adt.2012.05.003Effect of shell structure in the fusion reactions 82Se+134Ba and 82Se+138Ba

. Phys. Rev. C 65,Applications of Skyrme energy-density functional to fusion reactions for synthesis of superheavy nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 74,Fusion dynamics of symmetric systems near barrier energies

. Phys. Rev. C 80,Analysis of the fusion mechanism in the synthesis of superheavy element 119 via the 54Cr+243Am reaction

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Colloquium: Beta-delayed fission of atomic nuclei

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 1541-1559 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.85.1541Existence of proton halos near the drip line

. Phys. Rev. C 52, 3505-3508 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.52.3505β-delayed fission of 180Tl

. Phys. Rev. C 88,β-delayed fission of 192,194

At. Phys. Rev. C 87,Puzzling Two-Proton Decay of 67Kr

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120,Theoretical studies on the modes of decay of superheavy nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 94,Properties of 94(239)

. Phys. Rev. 70, 555-556 (1946). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.70.555Decay properties of Pu235, Pu237, and a new isotope Pu233

. Phys. Rev. 106, 1228-1232 (1957). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.106.1228The decay of the neutron deficient plutonium isotopes 232Pu, 233Pu and 234Pu

. Z. Phys. A 258, 337-343 (1973). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01392443New plutonium isotope: 231Pu

. Phys. Rev. C 59, 3086-3092 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.59.3086The new nuclide 230Pu

. Z. Phys. A 337, 231-232 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01294297New nuclides 228,229Pu

. Z. Phys. A 347, 225-226 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01292381α decay of the new isotope 227Pu

. Phys. Rev. C 110,The new isotope 242Pu and additional information on other plutonium isotopes

. Phys. Rev. 80, 1108-1109 (1950). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.80.1108Properties of Plutonium-243

. Phys. Rev. 83, 1267-1268 (1951). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.83.1267Plutonium-244 from Pile-Irradiated Plutonium

. Phys. Rev. 93, 1433-1433 (1954). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.93.1433The decay chain Pu245 Am245 Cm245

. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1, 254-261 (1955). https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1902(55)80030-9Identification of 246Pu, 247Pu, 246mAm, and 247Am and determination of their half-lives

. Sov. Radiochem. 25: 4. https://www.osti.gov/biblio/6638025The new isotopes Pu246 and Am246

. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1, 345-351 (1955). https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1902(55)80044-9Role of the entrance channel in the production of complex fragments in fusion-fission and quasifission reactions in the framework of the dinuclear system model

. Phys. Rev. C 84,Theoretical study on production of unknown neutron-deficient 280-283Fl and neutron-rich 290-292Fl isotopes by fusion reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 98,Possibilities for the synthesis of superheavy element Z = 121 in fusion reactions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 95 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01452-yPrediction of synthesis cross sections of new moscovium isotopes in fusion-evaporation reactions

, Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 7 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01157-0Production of heavy neutron-rich nuclei with radioactive beams in multinucleon transfer reactions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 28, 110 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-017-0266-zUnified description of fusion and multinucleon transfer processes within the dinuclear system model

. Phys. Rev. C 104,Fusion of heavy ions by means of the Langevin equation

. Phys. Rev. C 71,Time-dependent Hartree-Fock plus Langevin approach for hot fusion reactions to synthesize the Z=120 superheavy element

. Phys. Rev. C 99,Dynamical mechanism of fusion hindrance in heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Two-step model of fusion for the synthesis of superheavy elements

. Phys. Rev. C 66,Fusion by diffusion. II. Synthesis of transfermium elements in cold fusion reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 71,Cold fusion reaction of 58Fe + 208Pb analyzed by a generalized model of fusion by diffusion

. Phys. Rev. C 85,Production cross sections of superheavy elements Z=119 and 120 in hot fusion reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 89,Synthesis of superheavy nuclei: A search for new production reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 78,Conspicuous role of the neck-length parameter for future superheavy element discoveries

. Phys. Rev. C 108,Predicted cross sections for the synthesis of Z=120 fusion via 54Cr+248Cm and 50Ti+249Cf target-projectile combinations

. Phys. Rev. C 110,Time dependent Hartree-Fock fusion calculations for spherical, deformed systems

. Phys. Rev. C 74,Microscopic study of the hot-fusion reaction 48Ca+238U with the constraints from time-dependent Hartree-Fock theory

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Heavy-ion collisions and fission dynamics with the time-dependent Hartree–Fock theory and its extensions

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 103, 19-66 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2018.07.002Isospin dependence of nuclear multifragmentation in 112Sn+112Sn and 124Sn+124Sn collisions at 40 MeV/nucleon

. Phys. Rev. C 60,Fusion dynamics of symmetric systems near barrier energies

. Phys. Rev. C 80,Systematic study of 16O induced fusion with the Improved Quantum Molecular Dynamics Model

. Phys. Rev. C 90,Hartree-Fock Calculations with Skyrme’s Interaction. I. Spherical Nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 5, 626-647 (1972). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.5.626Search for possible way of producing super-heavy elements: Dynamic study on damped reactions of 244Pu+244Pu, 238U+238U and 197Au+197Au

. Mod. Phys. Lett. A 20, 2619-2627 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217732305018232Constrained molecular dynamics approach to fermionic systems

. Phys. Rev. C 64,Constrained molecular dynamics approach to fermionic systems

. Phys. Rev. C 64,VEGAS: A Monte Carlo Simulation of Intranuclear Cascades

. Phys. Rev. 166, 949-967 (1968). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.166.949Dynamics of the fusion process

. Nucl. Phys. A 388, 334-380 (1982). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(82)90420-1Competition between fusion-fission and quasi-fission in the reaction 28Si+208Pb

. Nucl. Phys. A 592, 271-289 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(95)00306-LFusion of deformed nuclei in the reactions of 76Ge+150Nd and 28Si+198Pt at the Coulomb barrier region

. Phys. Rev. C 62,Measurement of fusion excitation functions of 27,29,31Al+197Au

. Eur. Phys. J. A 10, 373-379 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1007/s100500170102Study of the dynamical potential barriers in heavy ion collisions

. Nucl. Phys. A 915, 90-105 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2013.07.003Microscopic study of deformation and orientation effects in heavy-ion reactions above the Coulomb barrier using the Boltzmann-Uehling-Uhlenbeck model

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Feng-Shou Zhang is an editorial board member for Nuclear Science and Techniques and was not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.