Introduction

The evaluated nuclear data serve as foundational information for nuclear device design. Its precision is crucial for ensuring the effectiveness and safety of nuclear devices, while reducing computational redundancy and improving economic efficiency [1]. Macroscopic examination of nuclear data is an essential approach to ensuring the quality of the evaluated data and serves as an effective method for evaluating and refining nuclear data. Shielding integral experimental data form the basis for research on macroscopic examinations [2].

Beryllium (9Be) plays a critical role in the nuclear industry. In both nuclear power reactors and fusion reactors, 9Be is widely utilized as a neutron reflector [3]. Moreover, 9Be is integral to space reactors [4], where it functions as a neutron reflector, neutron breeding material, and key component for the passive start-up of space reactors. Additionally, some neutron source devices, such as spallation neutron sources, frequently use 9Be as a material for neutron reflection and multiplication to enhance the neutron source performance [5]. Consequently, neutron reaction data for 9Be are highly significant in nuclear device design, directly influencing the neutron transport process, particularly in areas such as the angular distribution of elastic scattering, neutron multiplication factors, and double-differential energy spectrum of the 9Be(n, 2n)8Be reaction [6].

To test the reliability of 9Be evaluated data, a series of shielding integral experiments have been conducted worldwide. The main parameters measured were the neutron multiplication rate and the neutron leakage spectrum. Among them, the neutron multiplication rate measurement experiments mainly include the following:

1. The neutron multiplication rates of D-T neutrons and 252Cf spontaneous fission neutrons after interaction with beryllium spheres were conducted by Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) in the United States in 1993, using the manganese bath method. The thicknesses of the spheres were 4.6 cm, 12.1 cm, 15.6 cm, and 19.9 cm [7].

2. Neutron multiplication rates after the interaction of D-T neutrons with different thicknesses of beryllium spheres were measured using the total absorption method in the former Soviet Union in 1987, with thicknesses of 1.5 cm, 5 cm, and 8 cm [8].

3. Neutron multiplication rates after the interaction of D-T neutrons with beryllium spheres were measured by a total absorption method in China Academy of Engineering Physics (CAEP) in 1991, with sample thicknesses of 4.55 cm, 8.4 cm, 10.45 cm, and 14.85 cm [9].

Measurements of the neutron leakage spectrum were primarily performed using spherical and slab samples. Experiments involving spherical samples included the following:

1. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) in the United States performed a series of experiments in 1994 using 9Be spherical samples with thicknesses of 4.58 cm, 14.3 cm, and 20 cm. The leakage spectra of D-T neutrons interacting with the 9Be spheres were measured using the time-of-flight (TOF) method [10].

2. In 1995, the Chinese Academy of Engineering Physics (CAEP) measured the leakage neutron energy spectrum for D-T neutrons interacting with a 9Be sphere using the reaction proton method. The thickness of the sphere was 8.4 cm [11].

3. The Karlsruhe Neutron Transmission Experiment (KANT) was conducted by the Institute of Neutron Physics and Power Engineering (IPPE) in Germany in 1995 using 9Be spheres of varying thicknesses (5 cm, 10 cm, and 17 cm). These experiments utilized the TOF method with a pulsed D-T neutron source and employed a combination of an NE-213 detector, a recoil proton counter, and a Bonner sphere to obtain neutron spectra over a wide energy range (from thermal energy to 14 MeV) [12]. The results were incorporated into the NEA/SINBAD database in 2006 [13] and have been instrumental in improving 9Be data in various evaluated nuclear data libraries [14, 15].

Currently, two principal shielding integral experiments using slab 9Be samples have been conducted. The first, carried out by Osaka University in Japan in 1987, measured leakage neutron spectra at angles of 0°, 12.2°, 24.9°, 41.8°, and 66.8°, using samples with diameters of 31.5 cm and thicknesses of 5.08 cm and 15.24 cm [16]. The second was conducted by the China Institute of Atomic Energy (CIAE) in 2016, which measured leakage neutron spectra at angles of 61° and 121°, using samples with surface areas of 10 cm × 10 cm and thicknesses of 5 cm and 11 cm [17].

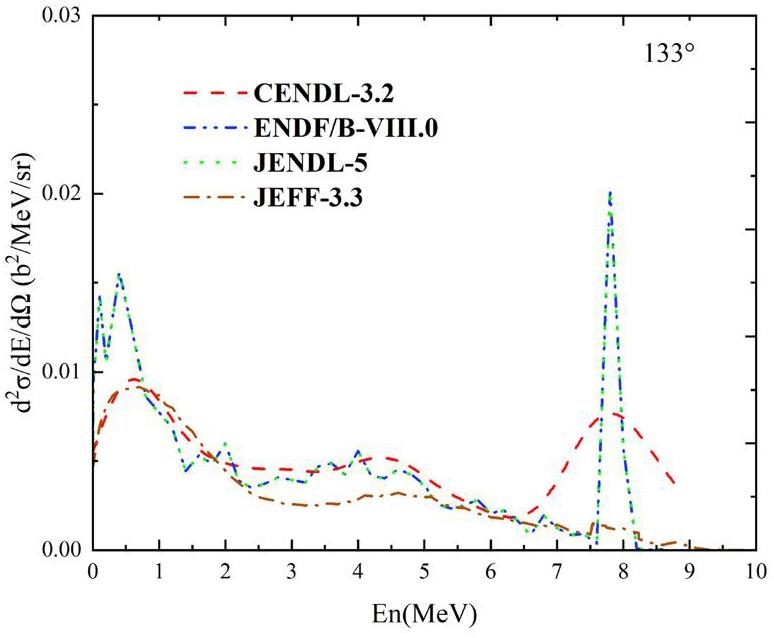

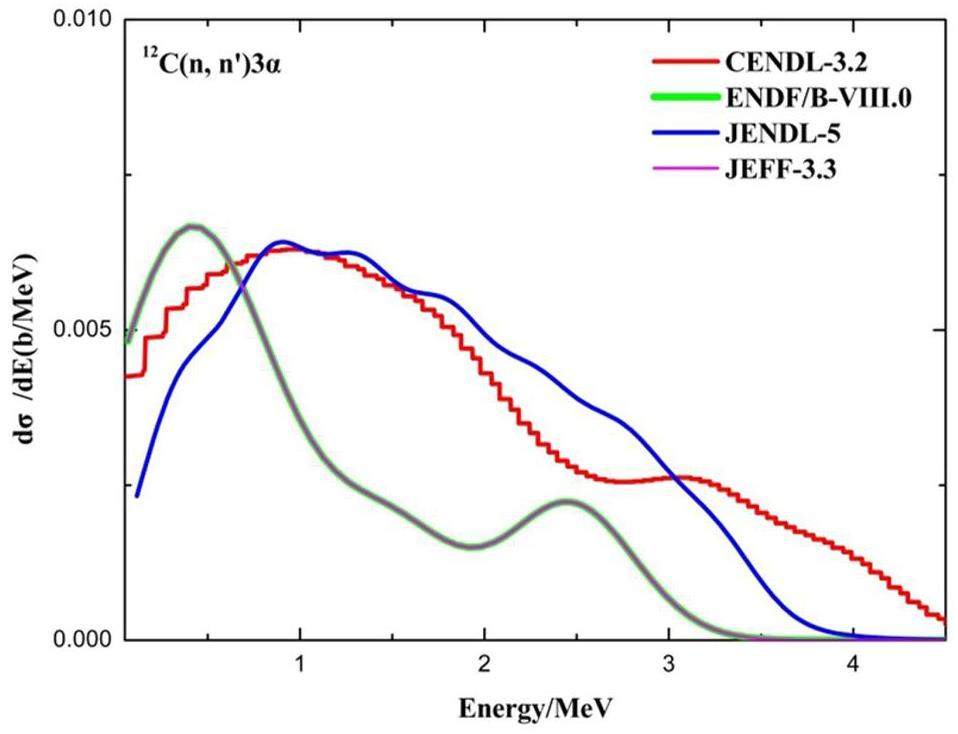

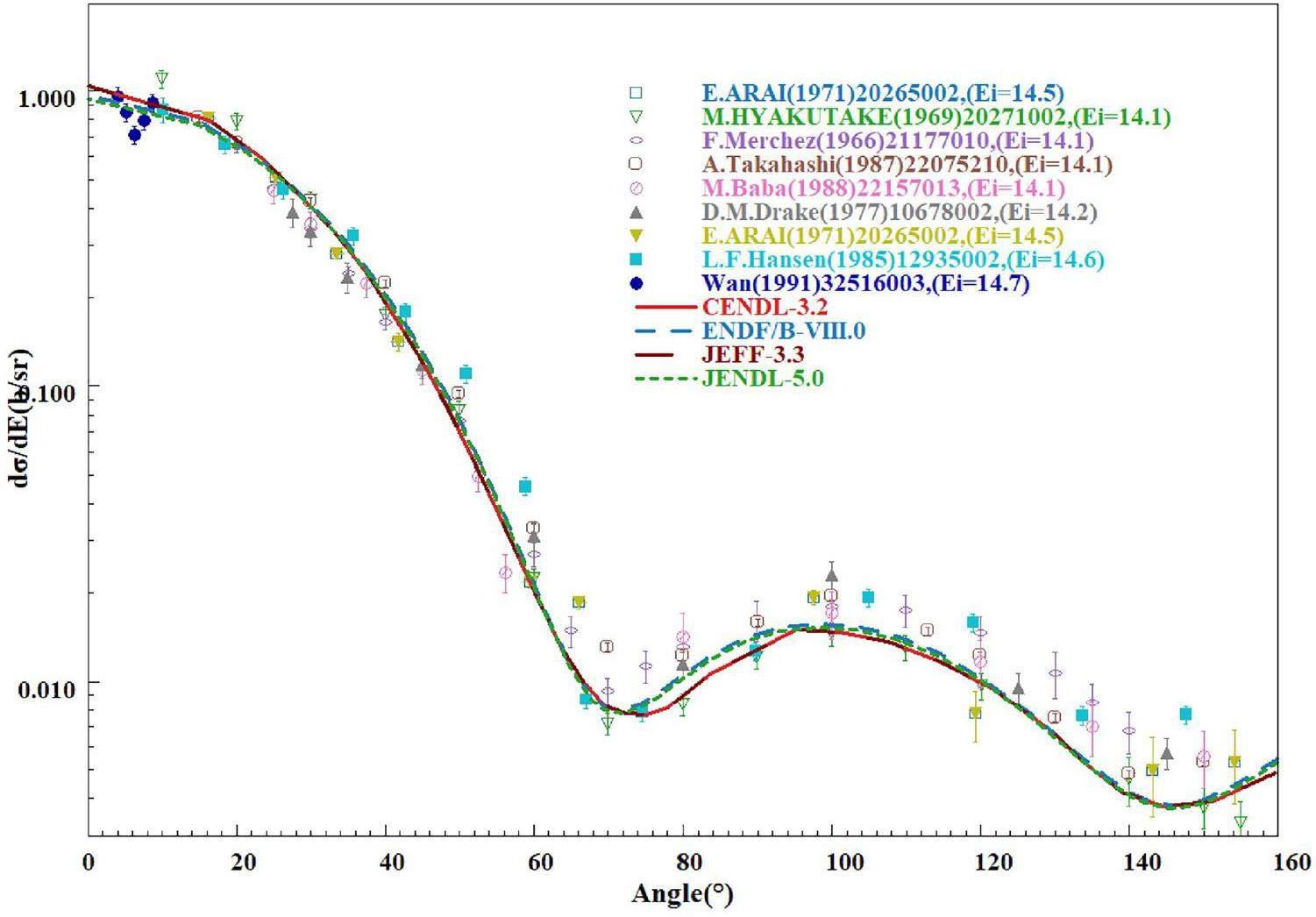

The 9Be(n, 2n)8Be reaction is particularly notable because of its six distinct reaction modes [18]. While most existing integral experiments worldwide utilize spherical samples to evaluate neutron multiplication rates, few experiments have focused on assessing double differential cross-section data. Importantly, only two measurements using slab samples were primarily limited to angles within 90, with only one measurement extending beyond this range. As a result, significant discrepancies remain in the double differential cross-section data, particularly at larger angles, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

To satisfy the requirements for precise calculations in nuclear device design, it is crucial to improve the double differential spectrum of the 9Be(n, 2n)8Be reaction. Measuring the neutron leakage spectra at various angles after neutron traversing slab materials is an effective approach for validating the double differential cross-section [19].

In this study, a shielding integral experiment was conducted using 9Be samples with a diameter of 30 cm and thicknesses of 4.4 cm, 8.8 cm, and 13.2 cm. A pulsed D-T neutron source [20, 21] developed by the China Institute of Atomic Energy was utilized, and neutron time-of-flight spectra were measured at six angles: 47°, 58°, 73°, 107°, 122°, and 133°. Simulations were performed using the MCNP-4C program [22], and nuclear data from CENDL-3.2 [23], ENDF/B-VIII.0 [24], JENDL-5 [25], and JEFF-3.3 [26] libraries. A comparison of the simulated and experimental results was performed to evaluate the quality of 9Be nuclear data, with particular emphasis on the CENDL-3.2 library.

Introduction of experimental device

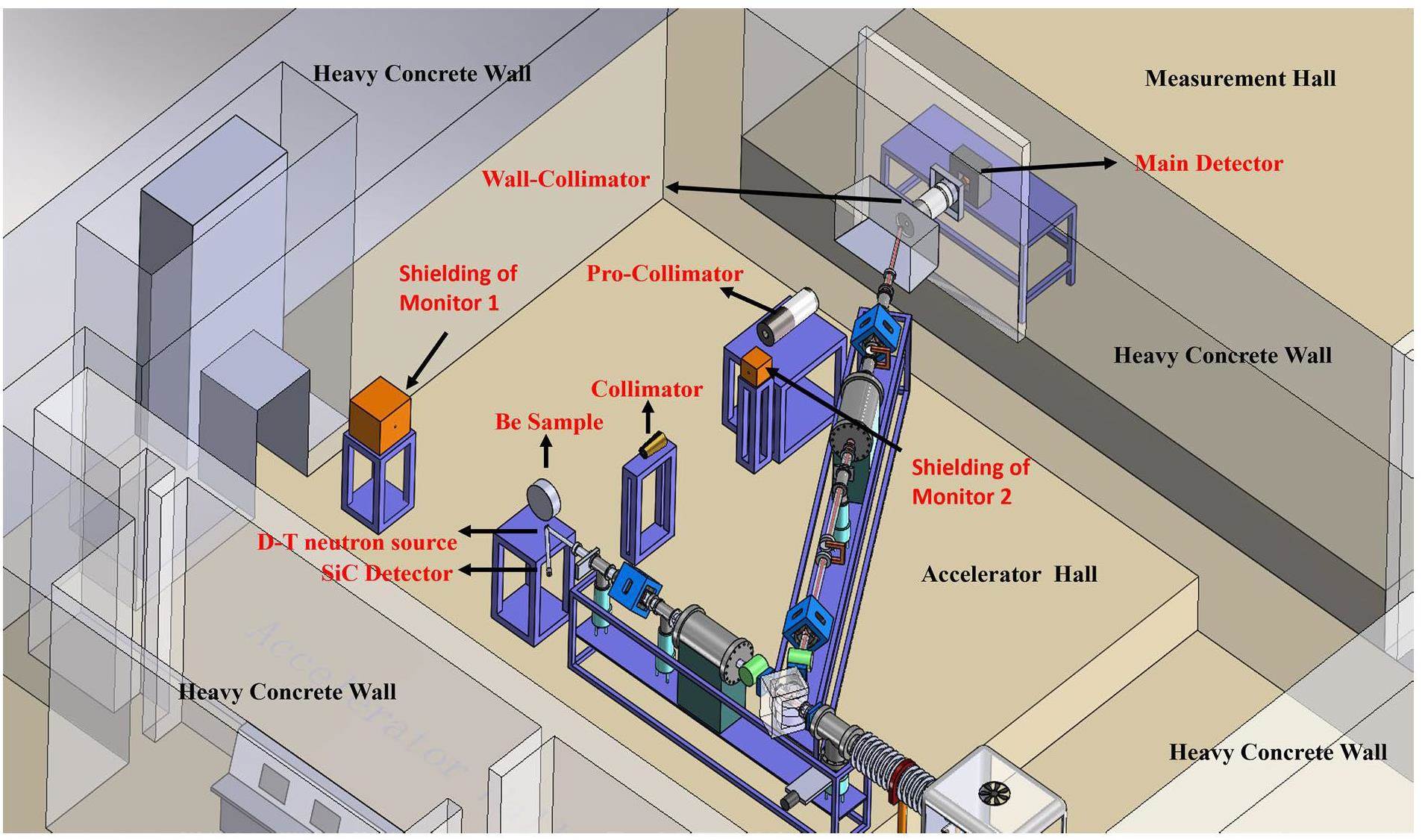

The layout of the shielding integral experiment is illustrated in Fig. 2. The experiment was performed using a nanosecond pulsed neutron generator established by the CIAE. A series of shielding integral experiments with important nuclides have been completed using this facility, including C [27], Fe [28-30], and 238U [31-33].

The neutron source

The D-T fusion neutron source was used in this experiment. Deuterium ions were accelerated using a high-pressure multiplier to achieve an energy of 300 keV, with the accelerator operating at a pulse frequency of 1.5 MHz and a beam current of 20 μA. The beam spot size was approximately 5–10 mm. These ions were then bombarded on a T-Ti target. The T-Ti target had a T/Ti ratio of approximately 1.6, with a reactive layer thickness of 1300 μg/cm2. Neutrons with energies centered around 14.5 MeV were generated through the T(d, n)4He reaction. The neutron yield was approximately

The measurement platform

The integral experiment platform, illustrated in Fig. 2, is composed of a neutron source, sample stage with precise positioning capabilities, sophisticated collimation system, suite of detectors, and digital data acquisition setup. To enhance the accuracy of neutron leakage measurements and effectively suppress background noise from environmental scattering, the main detector was strategically located in an adjacent hall. This strategic placement, combined with a multi-layer collimation system, ensures that the majority of the neutrons reaching the detector originate from the sample, thereby maximizing the local effect-to-background ratio.

The 9Be Sample

In the shielding integral experiment, the higher the purity of the sample, the better the test results obtained. The purity of the 9Be sample used in this experiment was 99.24%. Two disc-shaped samples with a diameter of 30 cm and thicknesses of 4.4 cm and 8.8 cm were customized and processed by the Northwest Rare Metal Materials Research Institute. A thickness of 13.2 cm was achieved by combining the two samples. Table 1 lists the specific sizes and parameters of the 9Be samples.

| Number | Dimension (cm) | Weight (g) | Density (g/cm3) | Composition (mass %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Φ30×4.42 | 5790 | 1.853 | Be (99.24), Fe (0.089), Al (0.0037),Si (0.0073) |

| 2 | Φ30×8.82 | 11560 | 1.854 | Mg (<0.005), Ni (0.016),Cr (0.0069), Mn (0.009) |

| 3 | Φ30×13.24 | 17350 | 1.854 | Cu (0.004), C (0.018), O (0.60) |

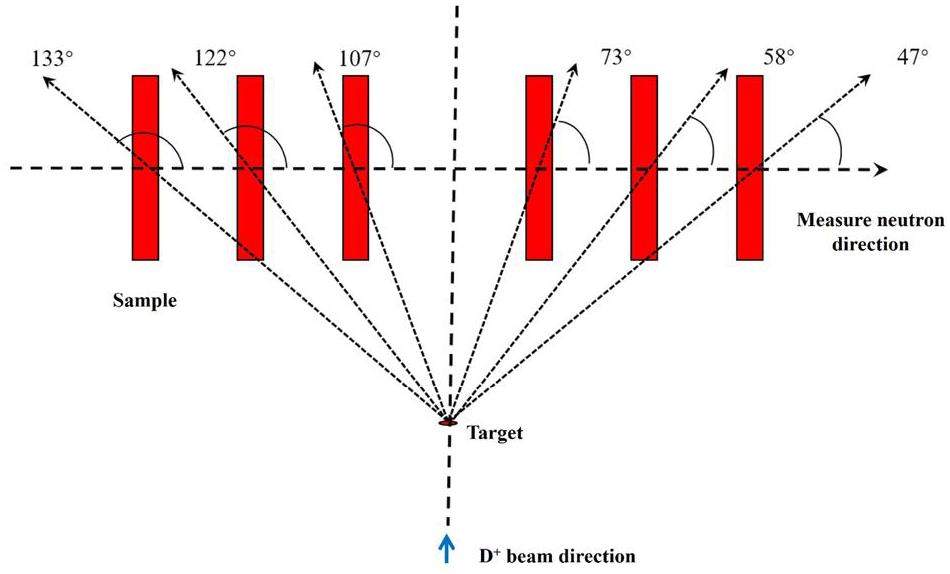

In the experiment, the positions of the neutron source and detector remained stationary, and angle variation was accomplished by moving the sample position, as depicted in Fig. 3. Keeping the direction of the outgoing neutron (from the sample center to the detector) fixed, modifying the position of the sample center on the quasi-line alters the direction of the incoming neutron (from the neutron source to the sample), thereby achieving a change in the angle between the incoming and outgoing neutrons. The leakage neutron spectra of 9Be samples were measured at six angles: 47°, 58°, 73°, 107°, 122°, and 133°. The three pairs of symmetric angles (47° and 133°, 58° and 122°, 73° and 107°) have identical angles between the incident neutron and D beam.

The collimation and shielding system

As shown in Fig. 2, the structure of the entire experimental hall is complex, resulting in a high scattering neutron background. The adoption of the collimator system effectively reduces the scattering background entering the detector. A collimator system consisting of a pre-collimator and a wall collimator was used in this experiment.

In the pre-collimator system, source neutrons may directly enter the collimator hole, scatter with the inner wall material, and be detected by the detector, thereby contributing to the background. To minimize this background, a set of copper shadow cones was employed in the pre-collimator system to block the direct entry of source neutrons into the collimator.

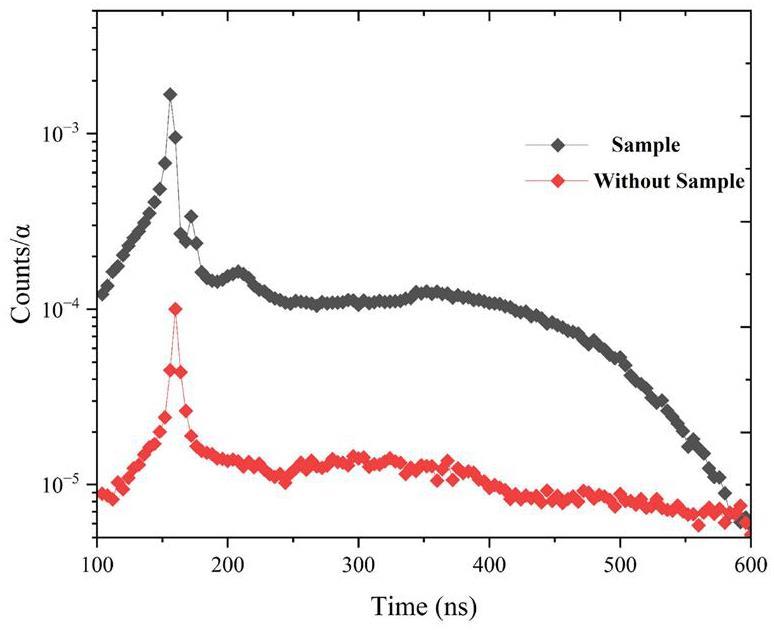

Figure 4 illustrates the effect spectrum and background spectrum of the 9Be sample with a thickness of 4.4 cm at 47°. As shown, for most experimental points, the effect-to-background ratio is greater than 10, demonstrating that the entire collimator system effectively suppresses the scattering neutron background.

The detector and data acquisition system

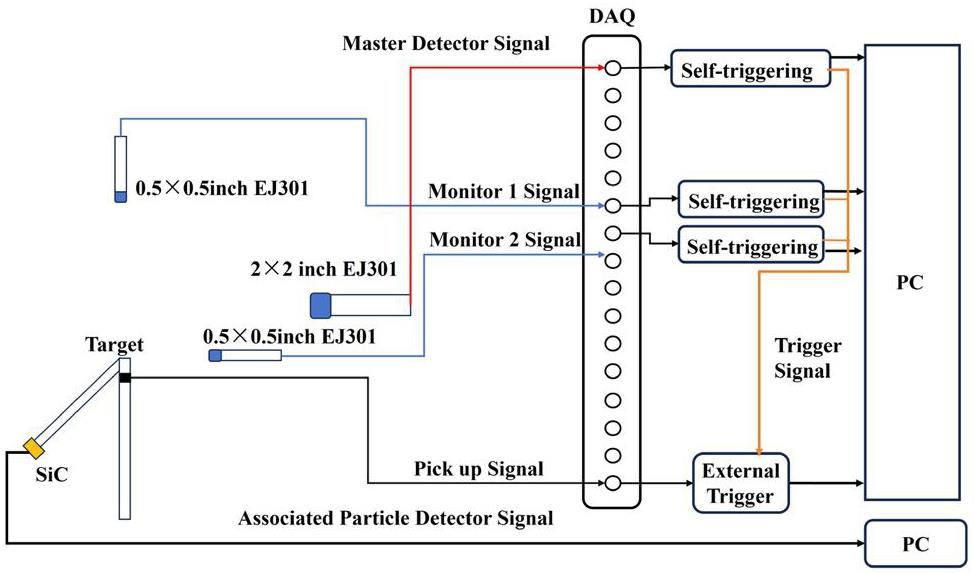

The spectrum of leaking neutrons was measured by TOF method in this experiment, corresponding to neutrons with energies above 0.8 MeV hitting the detector. A schematic of the detector and data acquisition system is shown in Fig. 5. Four detectors were used in the experiment: a 2 inch×2 inch EJ-301 liquid scintillation detector was used as the main detector to measure the TOF spectrum of the leaking neutron at different angles after the interaction of the neutron with the 9Be sample; two 0.5 inch×0.5 inch EJ-301 liquid scintillation detectors were used as monitors to directly measure the TOF spectrum of source neutrons and obtain the pulse time distribution; and a Si-C detector acted as an adjoint particle detector to measure the neutron yield of the source [34, 35]. In addition, there is a copper ring in the pipeline in front of the target. When the D ion beam generated by the ion source accelerated through the accelerator and passed through the copper ring, an induced charge was generated on the copper ring to form a pick-up signal, which was sent to the acquisition card after a fast preamplifier as the time signal of neutron generation.

A digital acquisition system was employed for data acquisition. Regarding hardware, a Pixie-16 acquisition card manufactured by XIA Corporation of the United States was utilized, and in terms of software, general acquisition software developed by the Experimental Nuclear Physics Group of Peking University was adopted [36]. The logic of the entire data acquisition process is shown in Fig. 5. Both the main detector signal and the two monitor signals were self-triggered. After the signal of any detector is triggered, a trigger signal is sent to the channel where the pick-up signal is located, and the channel collects and records the pick-up signal within 700 ns after receiving the trigger signal.

For every neutron produced by the T(d, n)4He reaction, an alpha particle is also produced in the opposite direction of the center of mass system. Therefore, the number of neutrons produced by the fusion reaction, known as neutron yield, can be deduced by measuring the number of alpha particles produced. The advantage of this method is that the detection efficiency of the semiconductor detector used in the measurement is basically 100%, the measurement accuracy is high, and absolute measurement can be achieved. Because the noise of the detector is restricted to the low-energy region and the counting rate ratio of alpha particles to noise exceeds 500, while the amplitude ratio is approximately 3, the plateau effect from scattered neutrons is negligible. The processed counting rates, representing the net peak counts after plateau subtraction, ensure accurate neutron yield estimation.Therefore, the Si-C detector was used to measure the alpha particles produced by the D-T fusion reaction.

The alpha particles produced by T(d, n)4He were measured using a Si-C detector at 135°, and the normalization coefficient was calculated. The neutron flux obtained in the unit solid angle in direction θ can be expressed by the following formula:

Introduction of MC simulation

In this study, the leakage neutron spectrum of the 9Be sample was obtained via simulation calculations using the MCNP-4C program [37]. In the simulation process, the energy distribution, angular flux distribution, pulse time distribution, and detector efficiency curve were considered in detail.

Calculation of source neutron energy and angular flux distribution

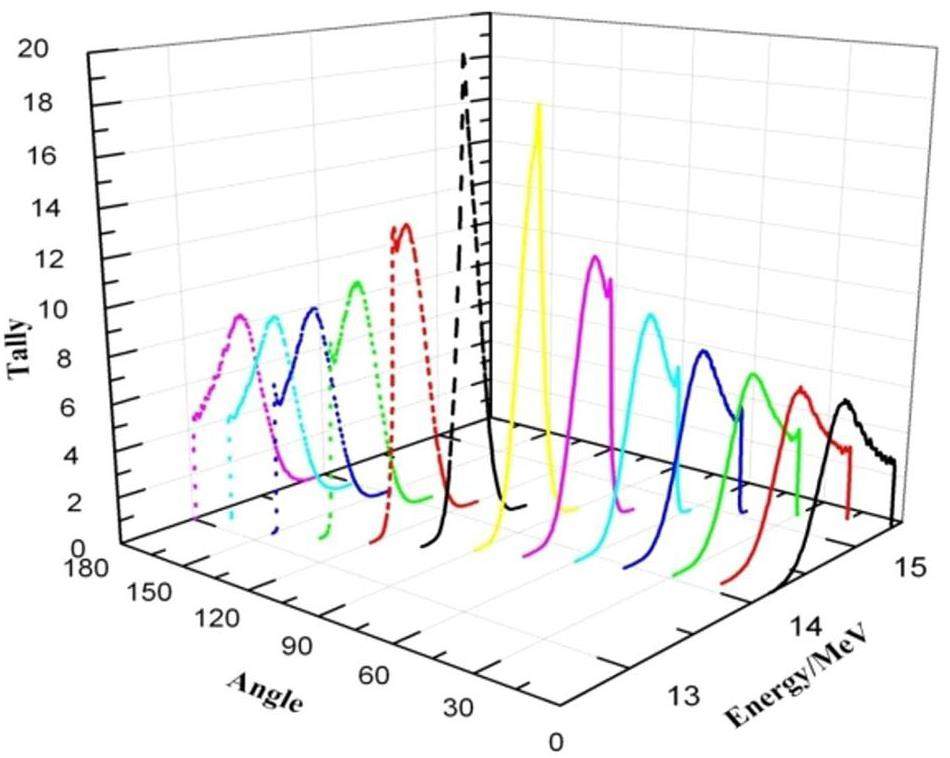

An accurate description of the energy spectrum and angular distribution of neutron sources is necessary for obtaining reliable simulation results. Owing to the complex environment of the experimental hall, it is difficult to eliminate the influence of the scattering neutron background on the experimental measurement results, which makes it challenging to measure the energy spectrum and angular flux distribution of the D-T neutron source through experiments. Therefore, a Monte Carlo simulation method was adopted in this study to obtain the energy spectrum and angular flux distribution of the D-T neutron source. The simulation was performed using the TARGET program [38] developed by the PTB Laboratory in Germany, considering the target structure parameters, material data, and incident beam parameters of the D-T neutron source. The calculated results are shown in Fig. 6. The neutron energy generated by the T(d, n)4He reaction gradually decreased with an increase in the angle, and the flux gradually decreased as the angle increased.

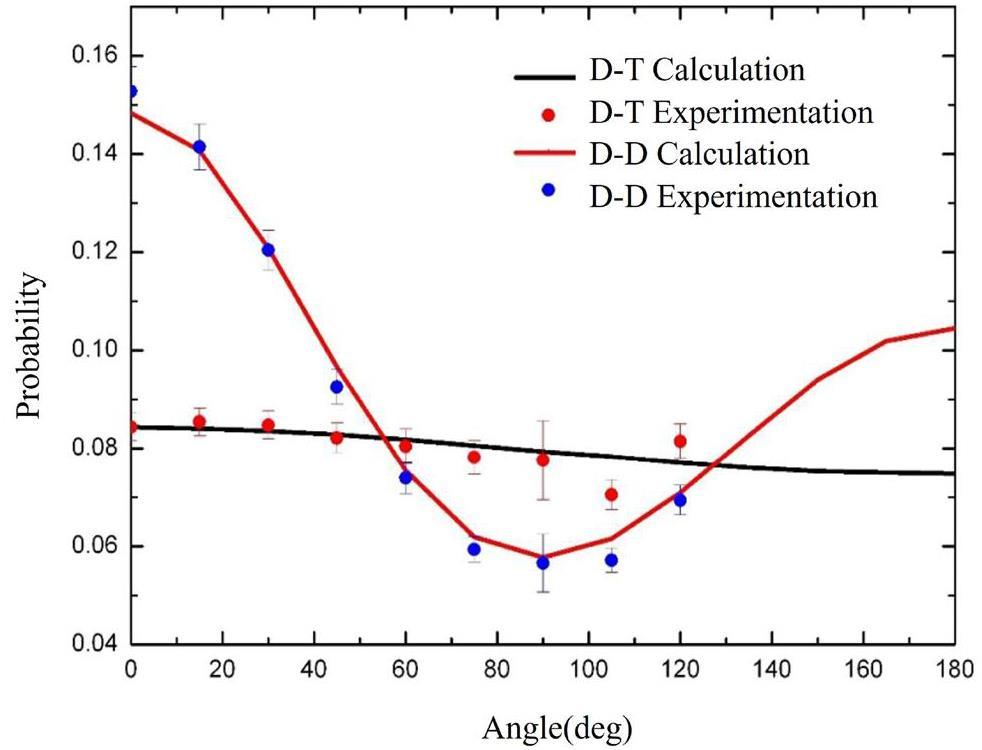

To verify the reliability of the simulation results, the angular flux of the neutron source is measured at several specific angles. A comparison between the measurement and simulation results is shown in Fig. 7, and the results indicates that the measurement results are in good agreement with the simulation results.

In the D-T neutron source, deuterium deposition on the target inevitably leads to D-D reactions. The counting rates of the accompanying particles from both reactions were measured using a SiC detector. In the simulations, we also included the neutron energy spectrum generated by the D-D reaction in the source term. However, its impact remains minimal, contributing only to 1.2% increase in the total flux detected by the main detector. This is primarily because the target is regularly replaced as the alpha counting rate from the D-T reaction decreases, thereby limiting the influence of the D-D reactions.

Calculation of source neutron pulse time distribution

The pulse time distribution of the source neutron was obtained by the Maximum Likelihood Expectation-Maximization (MLEM) solution spectrum using the source neutron time-of-flight spectrum measured by two monitors. The specific process is described in detail in Ref. [39].

Calculation of detector efficiency curve

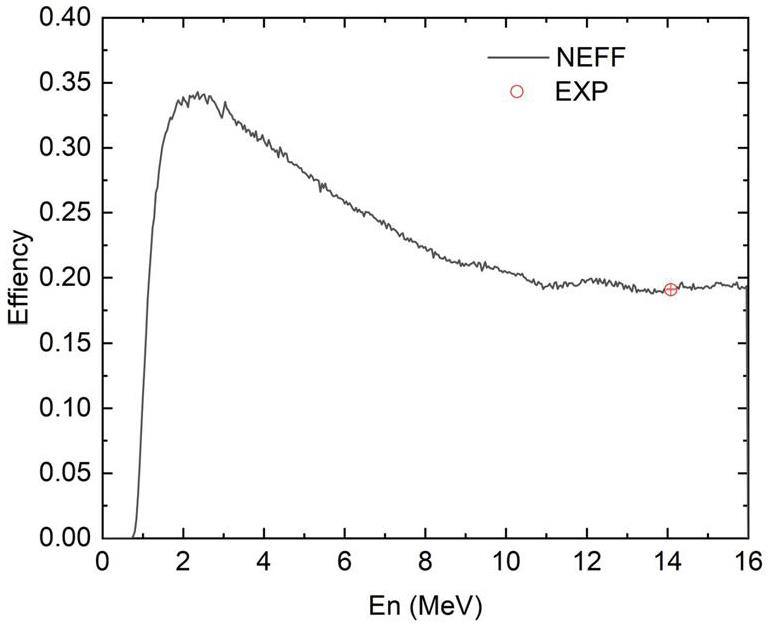

The efficiency curve of the liquid detector was obtained using the NEFF program [40], which was developed by the German PTB laboratory. The geometric parameters of the detector crystal, the standard light response curve, and the energy threshold were considered in the calculations. Additionally, the absolute efficiency value of the detector was calibrated using 14.1 MeV neutrons generated by the D-T reaction. The calibration results were in good agreement with the theoretical calculation results, as shown in Fig. 8.

Simulation of 9Be leakage neutron spectrum

In the input card of MCNP-4C, the obtained neutron energy spectrum distribution, angular flux distribution, pulse time distribution, and liquid scintillator detector efficiency curve were described in detail to ensure accurate simulation results. In addition, the simulation model was simplified, and materials with little influence on the leakage neutron spectrum, such as the floor and walls of the hall, were discarded. Structures with a significant influence were retained, including the target structure, sample, shadow cone, pre-collimator, and wall collimator.

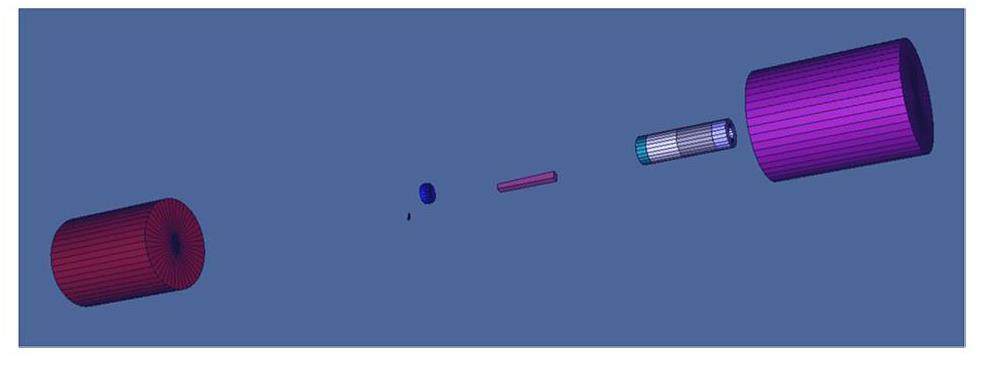

As shown in Fig. 9, the entire neutron transport model was simplified into a cylinder with a diameter of 1.5 m, and the target structure, collimator, and sample were modeled based on their actual structure and size. This model was used to simulate the leakage neutron TOF spectra at various angles. To simulate the background, the material of the sample was changed to air. The evaluated nuclear data of 9Be from the CENDL-3.2, ENDF/B-VIII.0, JENDL-5, and JEFF-3.3 libraries were adopted in the simulation, whereas the nuclear data of all other structural materials were obtained from ENDF/B-VIII.0 library.

Systematic inspection based on standard sample method

The comparison between the experimental results of the standard samples and the simulation results is an important reference mark to ensure the reliability of the experimental system. Neutron leakage spectra from polyethylene samples with dimensions of 30 cm × 30 cm × 6 cm were measured at 47°, 61°, and 79°, and the reliability of the experimental system was tested.

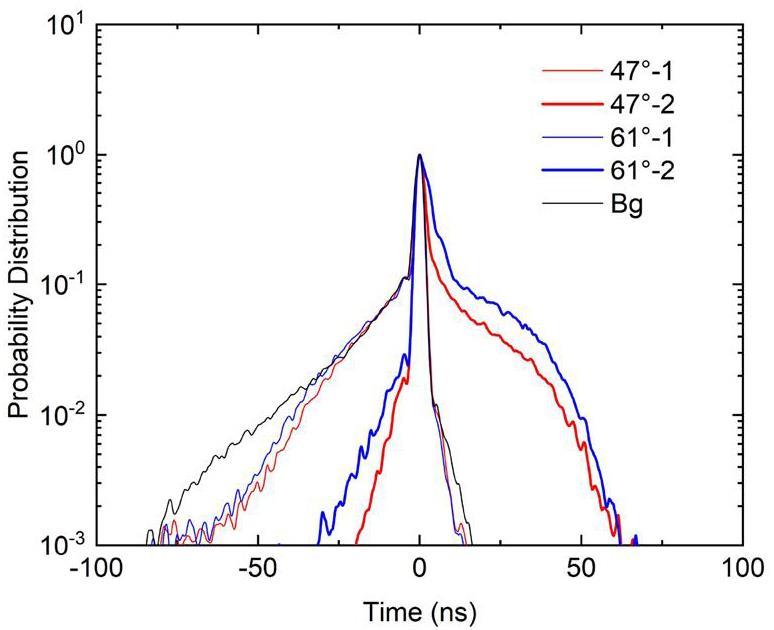

To verify the accuracy of the pulse time distribution obtained based on the MLEM algorithm, two rounds of data measurements were carried out at 47 and 61 for the measurement of the polyethylene sample. The pulse time distributions obtained using the MLEM algorithm are shown in Fig. 10. In the figure, the pulse time distributions of 47°-1 and 61°-1 exhibit an obvious left-leaning phenomenon (the left side is higher than the right side), whereas the pulse time distributions of 47°-2 and 61°-2 exhibit an obvious right-leaning phenomenon (the right side is higher than the left side). This left-leaning or right-leaning phenomenon was caused by the influence of the phase of the 6 MHz focusing signal in the accelerator, which affected the pulse time distributions.

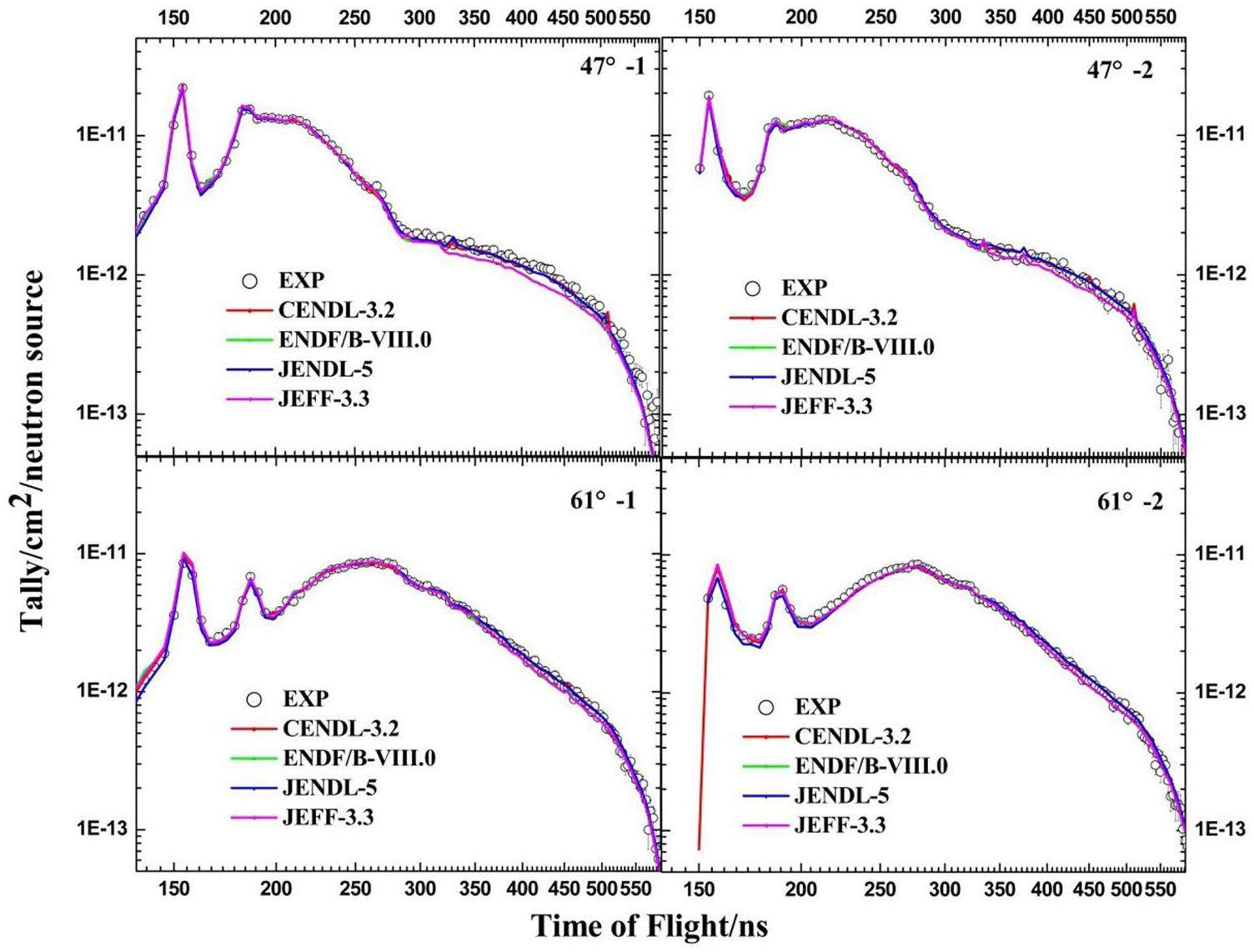

Based on the above pulse time distribution, the evaluation data of C and H in the CENDL-3.2, ENDF/B-VIII.0, JENDL-5, and JEFF-3.3 databases were used for the simulation. A comparison between the simulation and experimental results is shown in Fig. 11. It can be observed that under different pulse time distribution conditions, the simulation results are in good agreement with the experimental results, which indicates that the pulse time distribution based on the MLEM algorithm is reliable.

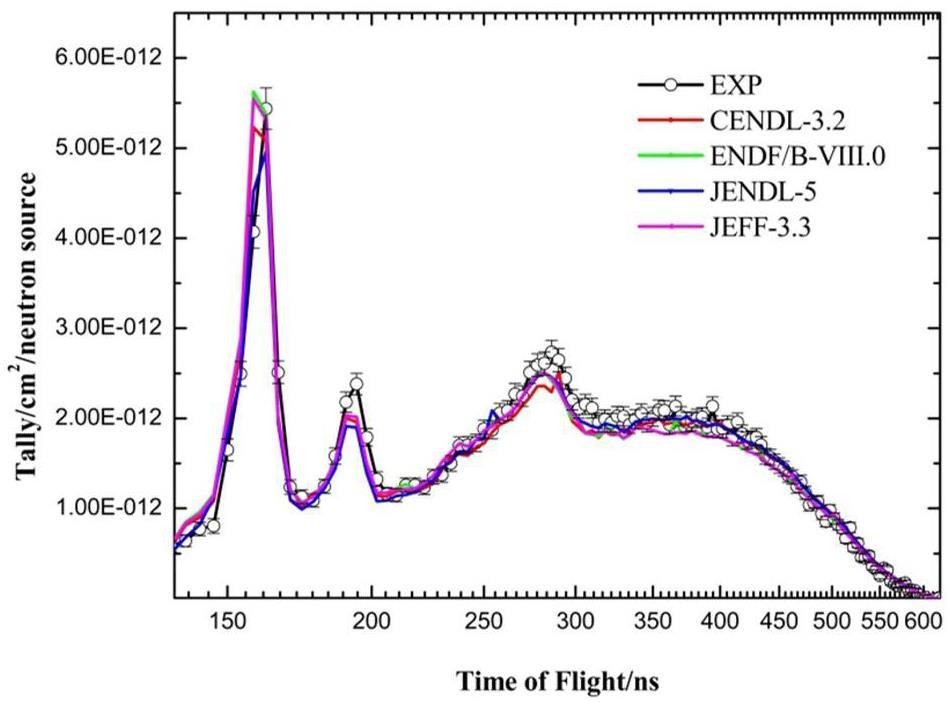

In addition, to verify the accuracy of the detection efficiency curve in the low energy region (near the threshold of 0.8 MeV), the neutron leakage spectrum from the polyethylene sample was measured at 79. At this angle, because the incident neutron loses significant energy after n-p scattering, the energy of the outgoing neutron is mainly concentrated in the low energy region. The comparison between the experimental result and the simulated result of the TOF spectrum leaked from the polyethylene sample at 79° is shown in Fig. 12. The experimental results and the simulated results are in good agreement in the low energy region, which indicates that the efficiency curve of the detector in the low energy region is accurate.

The n-p scattering neutron peak areas of the TOF spectra in Fig. 11 and Fig. 12 were integrated to obtain the experimental and simulated values from different libraries. The C/E values of the different libraries were obtained after comparing the simulated and experimental values, as shown in Table 2. It can be seen that most of the C/E values of each library are consistent within 3%, which proves that the experimental data measured by the shielding integral system are very reliable.

| Angle | Pulse Time Distribution | CENDL-3.2 | ENDF/B-VIII.0 | JENDL-5 | JEFF-3.3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 47°-1 | Left-leaning | 0.988 ± 0.036 | 0.992 ± 0.036 | 0.990 ± 0.036 | 0.998 ± 0.036 |

| 47°-2 | Right-leaning | 1.005 ± 0.036 | 1.013 ± 0.037 | 1.003 ± 0.036 | 1.012 ± 0.037 |

| 61°-1 | Left-leaning | 0.986 ± 0.036 | 0.986 ± 0.036 | 1.002 ± 0.036 | 0.988 ± 0.036 |

| 61°-2 | Right-leaning | 0.969 ± 0.035 | 0.971 ± 0.035 | 0.977 ± 0.035 | 0.970 ± 0.035 |

| 79° | — | 0.996 ± 0.036 | 0.948 ± 0.035 | 1.006 ± 0.037 | 0.947 ± 0.035 |

The C/E values in Table 2 from the ENDF/B-VIII.0 and JEFF-3.3 libraries have an underestimation of approximately 5% at 79. This is mainly because of the 12C(n, n’)3α emitted neutron spectra given by ENDF/B-VIII.0 and JEFF-3.3 libraries were significantly lower than those given by the CENDL-3.2 and JENDL-5 libraries, as shown in Fig. 13.

Comparison and analysis of calculated neutron TOF spectra and experimental ones leaked from 9Be sample

The TOF spectra comparison between simulation results and experimental results

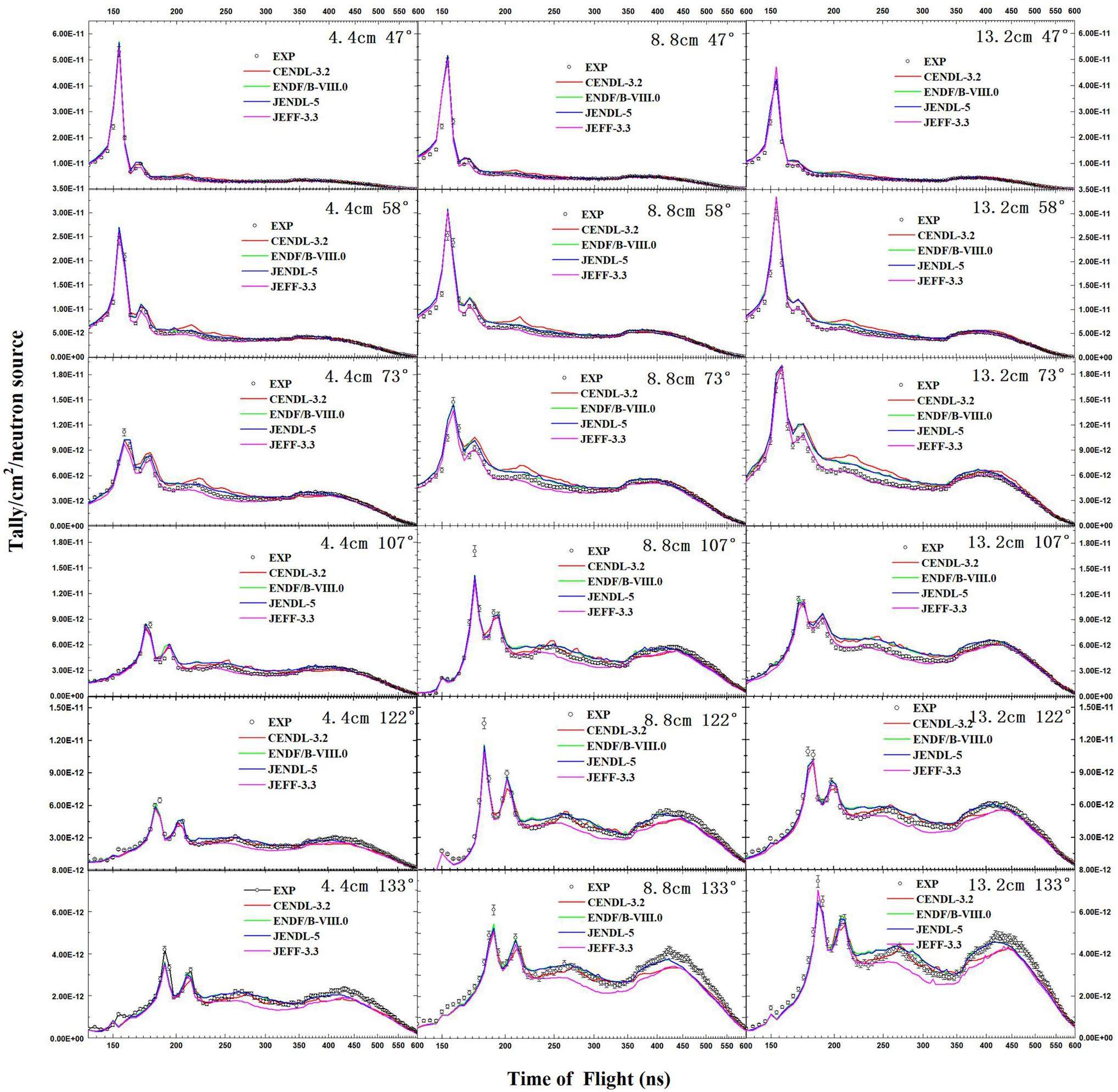

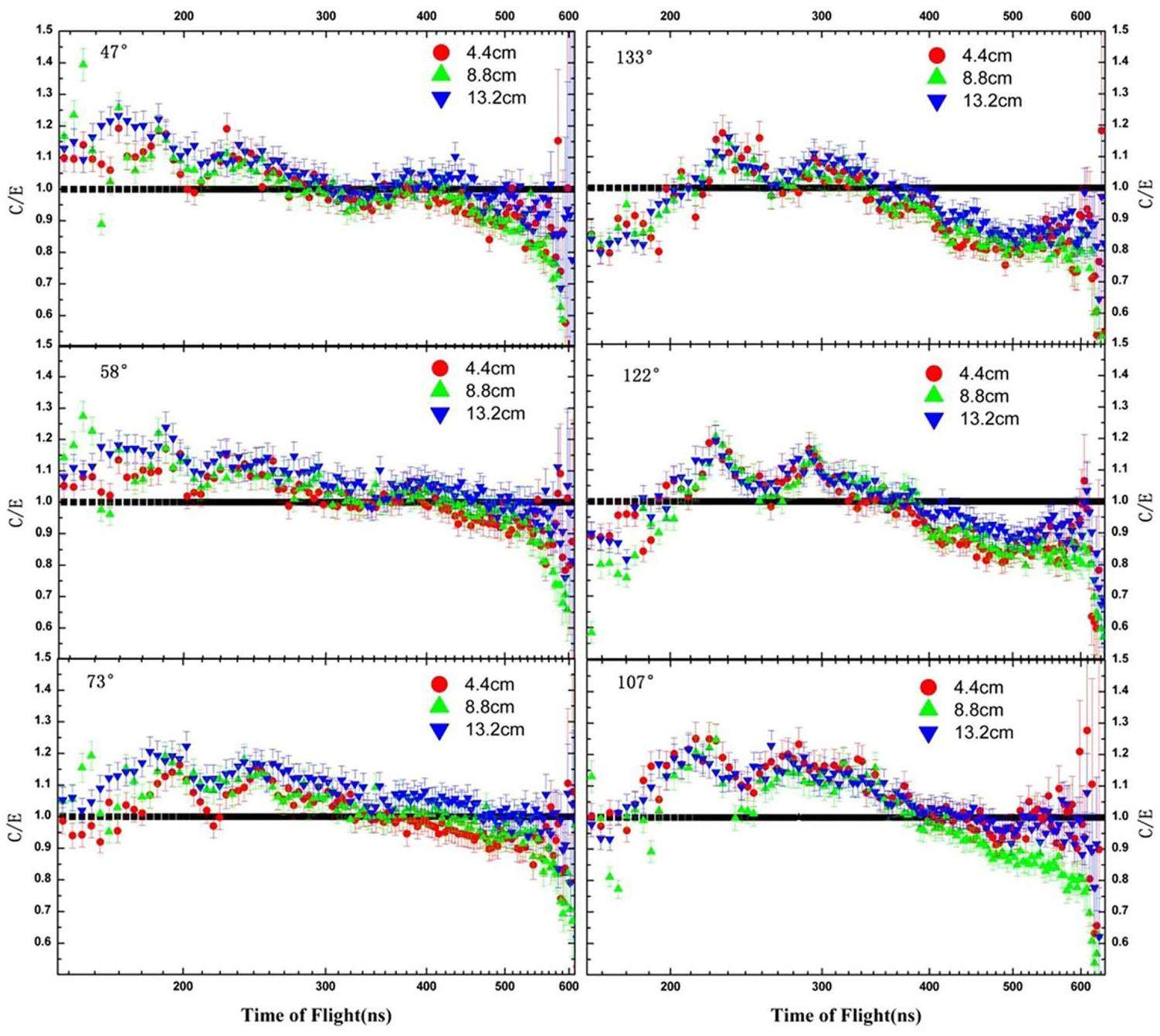

The experimental measurement results of the leakage neutron TOF spectrum after data processing were compared with the simulation results from the different libraries, as shown in Fig. 14.

From the comparison of leakage neutron spectra, it is clear that:

1. The simulation results of the CENDL-3.2 library were higher than the experimental results between 200 ns–300 ns at small angles (47°, 58°, and 72°).

2. The simulation results of the JEFF-3.3 library were significantly lower than the experimental results at all angles of approximately 250 ns, especially in the direction of large angles (greater than 90°).

3. At large angles, especially 122° and 133°, the simulation results of each library were lower than the experimental results between 400 ns–600 ns.

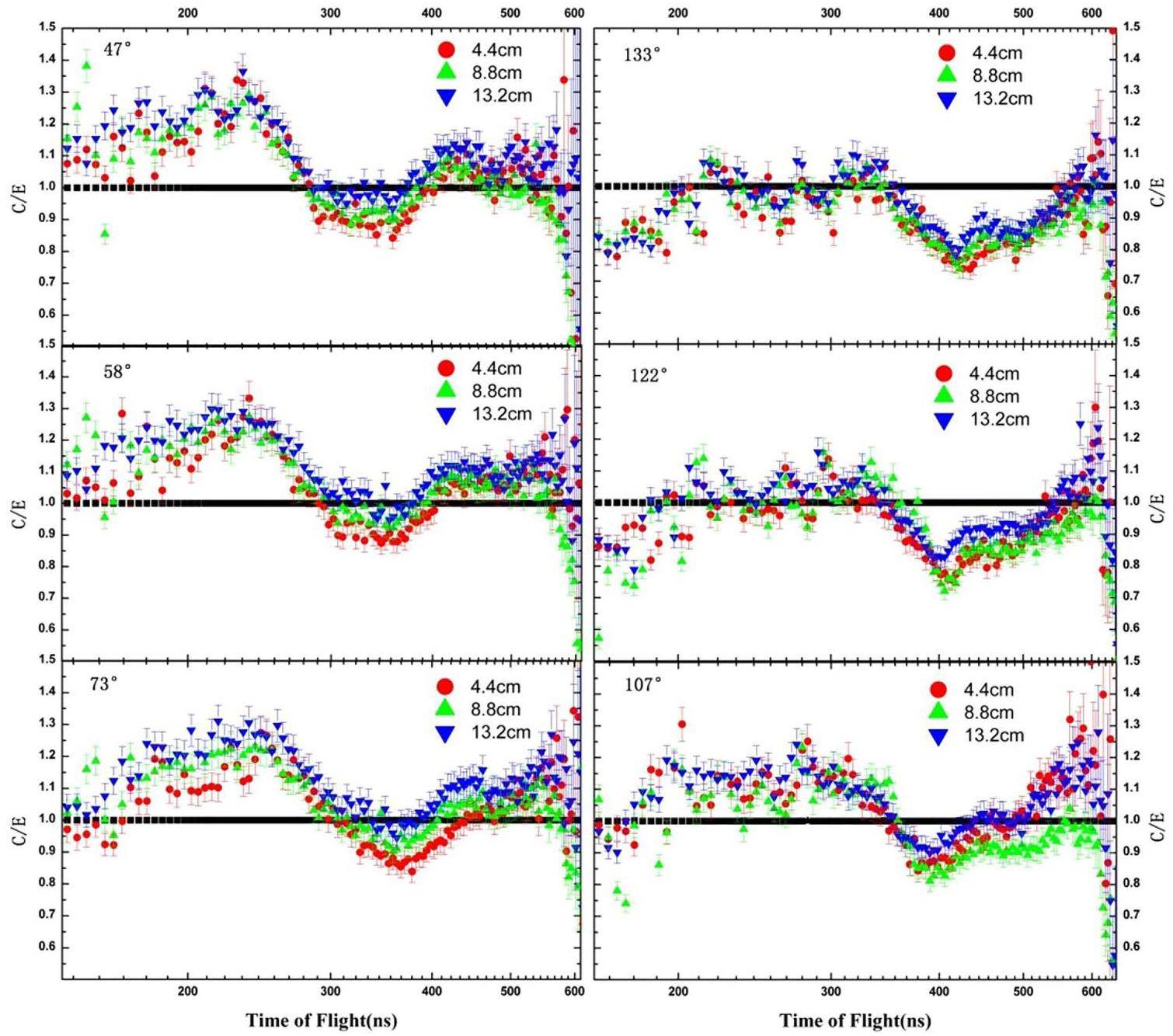

Change of C/E value with flight time

By dividing the simulation results of the CENDL-3.2 library by the experimental results, the change in the C/E value with the flight time was obtained, as shown in Fig. 15. As can be seen from the figure, the simulation results of the CENDL-3.2 library in the range of 180–280 ns are higher than the experimental results, but lower than the experimental results in the range of 280–400 ns. At large angles, the simulation results were significantly lower than the experimental results in the range of 350–550 ns.

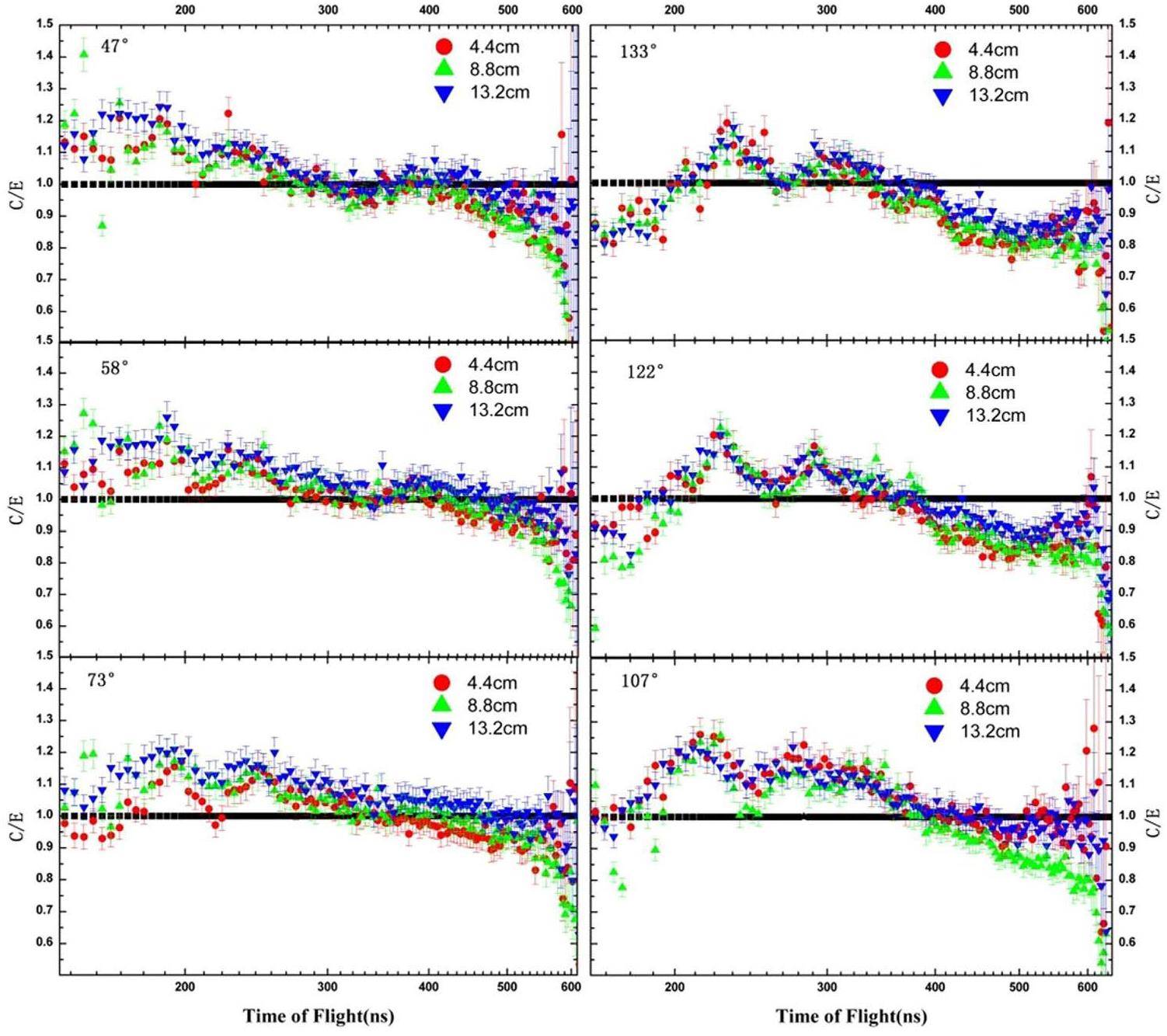

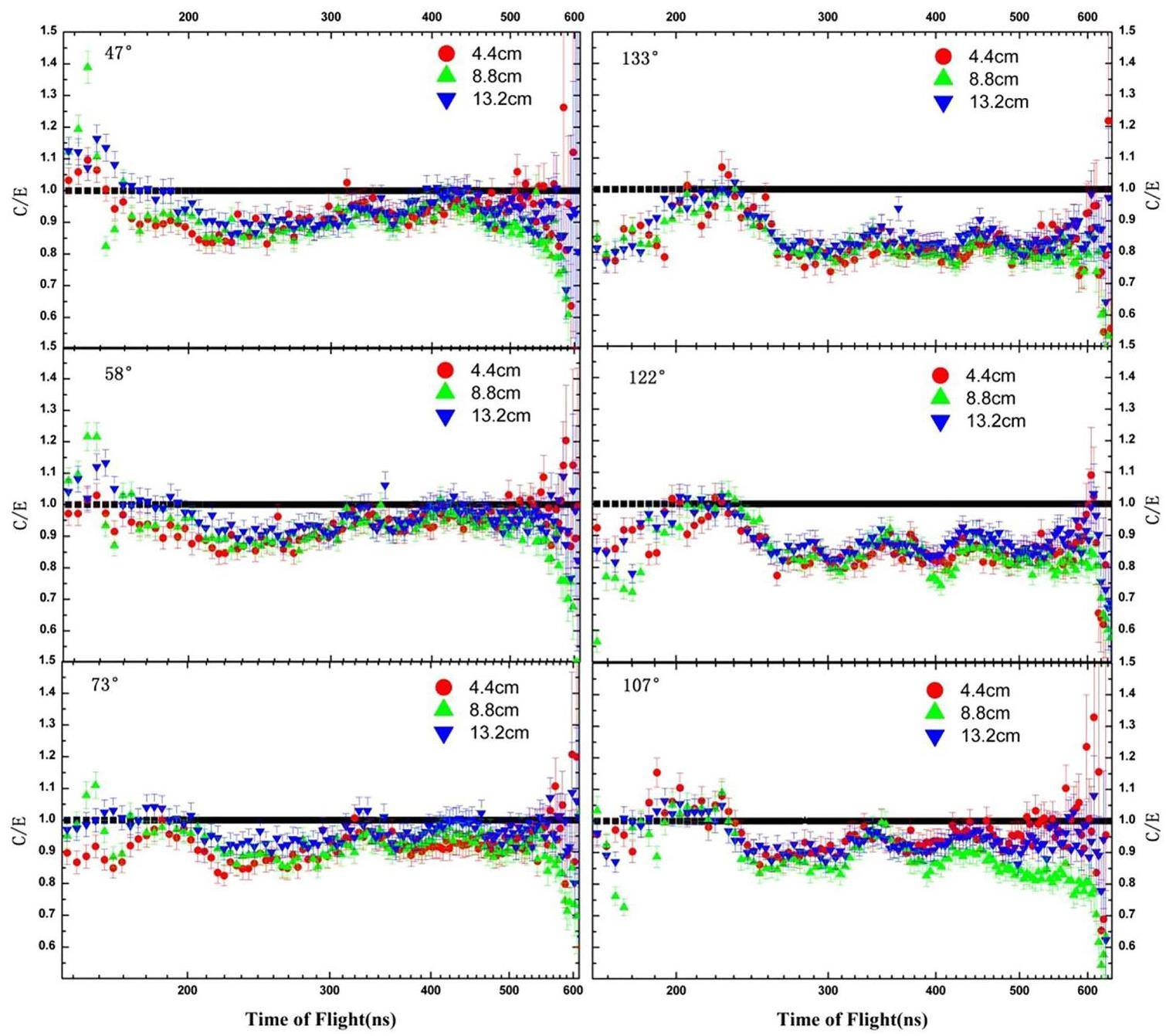

By dividing the simulation results of ENDF/B-VIII.0 library based on the experimental results, the results obtained are shown in Fig. 16. As can be seen, the C/E value of the ENDF/B-VIII.0 library decreases with an increase in flight time (energy decrease), and is higher in the high-energy region, while it is slightly lower in the low-energy region. This phenomenon becomes more obvious with an increase in angle and improves with an increase in the sample thickness.

The results obtained by dividing the simulation results of the JENDL-5 library by the experimental results are shown in Fig. 17. The trend of C/E values in the JENDL-5 library was generally the same as that in ENDF/B-VIII.0 library, where the simulation results were higher in the high-energy region and lower in the low-energy region.

By dividing the simulation results of the JEFF-3.3 library by the experimental results, the results obtained are shown in Fig. 18. It can be seen that the simulation results of the JEFF-3.3 library are generally lower than the experimental results.

Comparison and analysis of C/E values in different energy regions

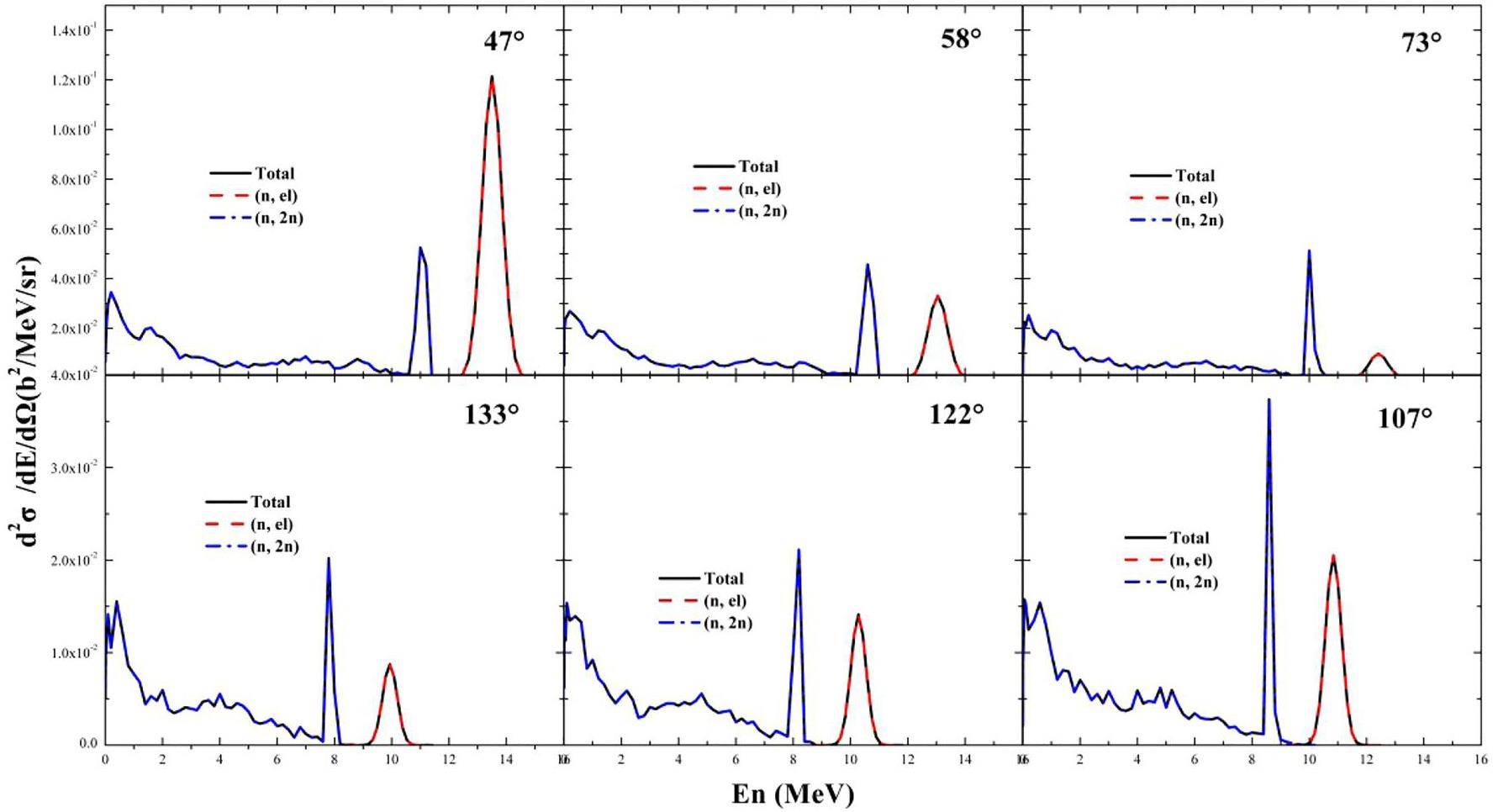

The NDPlot program was used to obtain the outgoing neutron spectra of 14.5 MeV neutrons in the CENDL-3.2 library at different angles after interaction with 9Be samples, and the results are shown in Fig. 19. The choice of 14.5 MeV neutrons corresponds to the average energy of neutrons at forward angles in the D-T reaction, making it representative for cross-sectional analysis. It can be observed that the outgoing neutron has only two reaction channels: elastic scattering and the (n, 2n) reaction. Owing to the relatively light mass of Be, the elastic scattering neutron energy generated by the interaction between neutrons and Be decreased significantly with an increase in the exit angle.

Therefore, the secondary neutrons at each angle are first divided into elastic scattering and (n, 2n) reaction energy regions according to the outgoing neutron energy. Considering the actual pulse width of the pulsed neutron beam, the elastic scattering peak is about ±10 ns (approximately 1/10th of the bottom width of the pulse time distribution). Additionally, according to the shape of the neutron energy spectrum derived from the (n, 2n) reaction in Fig. 19, the (n, 2n) emitted neutron spectrum is further subdivided into two energy regions, namely:

1. (n, 2n) reaction high-energy region, corresponding to the tail of the elastic scattering peak to the 2.8 MeV energy region;

2. (n, 2n) reaction low-energy region, corresponding to 2.8 MeV to the detector measurement threshold of 0.8 MeV energy region.

The integral comparison of the experimental and simulated results across different energy ranges yields the C/E values listed in Table 3.

| Angle | Thickness (cm) | Reaction channel | CENDL−3.2 | ENDF/B-VIII.0 | JENDL-5 | JEFF−3.3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 47◦ | 4.4 | (n,el) | 1.080 ± 0.039 | 1.107 ± 0.040 | 1.096 ± 0.040 | 1.046 ± 0.038 |

| (n,2n) | 1.063 ± 0.038 | 1.031 ± 0.037 | 1.025 ± 0.037 | 0.931 ± 0.034 | ||

| (n,2n)-High | 1.117 ± 0.040 | 1.085 ± 0.039 | 1.076 ± 0.039 | 0.915 ± 0.033 | ||

| (n,2n)-Low | 0.997 ± 0.036 | 0.966 ± 0.035 | 0.964 ± 0.035 | 0.951 ± 0.034 | ||

| Total | 1.068 ± 0.039 | 1.053 ± 0.038 | 1.046 ± 0.038 | 0.964 ± 0.035 | ||

| 8.8 | (n,el) | 1.097 ± 0.040 | 1.108 ± 0.040 | 1.107 ± 0.040 | 1.064 ± 0.039 | |

| (n,2n) | 1.063 ± 0.038 | 1.016 ± 0.037 | 1.017 ± 0.037 | 0.915 ± 0.033 | ||

| (n,2n)-High | 1.119 ± 0.040 | 1.069 ± 0.039 | 1.068 ± 0.039 | 0.909 ± 0.033 | ||

| (n,2n)-Low | 0.999 ± 0.036 | 0.957 ± 0.035 | 0.960 ± 0.035 | 0.922 ± 0.033 | ||

| Total | 1.071 ± 0.039 | 1.038 ± 0.037 | 1.038 ± 0.037 | 0.951 ± 0.034 | ||

| 13.2 | (n,el) | 1.135 ± 0.041 | 1.143 ± 0.041 | 1.144 ± 0.041 | 1.148 ± 0.042 | |

| (n,2n) | 1.121 ± 0.040 | 1.064 ± 0.038 | 1.064 ± 0.038 | 0.960 ± 0.035 | ||

| (n,2n)-High | 1.177 ± 0.043 | 1.118 ± 0.040 | 1.113 ± 0.040 | 0.949 ± 0.034 | ||

| (n,2n)-Low | 1.058 ± 0.038 | 1.004 ± 0.036 | 1.010 ± 0.037 | 0.973 ± 0.035 | ||

| Total | 1.124 ± 0.041 | 1.082 ± 0.039 | 1.083 ± 0.039 | 1.003 ± 0.036 | ||

| 58◦ | 4.4 | (n,el) | 1.063 ± 0.039 | 1.069 ± 0.039 | 1.056 ± 0.038 | 0.986 ± 0.036 |

| (n,2n) | 1.068 ± 0.039 | 1.034 ± 0.037 | 1.036 ± 0.037 | 0.940 ± 0.034 | ||

| (n,2n)-High | 1.119 ± 0.040 | 1.075 ± 0.039 | 1.079 ± 0.039 | 0.919 ± 0.033 | ||

| (n,2n)-Low | 1.012 ± 0.037 | 0.989 ± 0.036 | 0.988 ± 0.035 | 0.964 ± 0.035 | ||

| Total | 1.067 ± 0.039 | 1.040 ± 0.038 | 1.040 ± 0.038 | 0.948 ± 0.034 | ||

| 8.8 | (n,el) | 1.094 ± 0.040 | 1.105 ± 0.040 | 1.091 ± 0.040 | 1.035 ± 0.038 | |

| (n,2n) | 1.082 ± 0.039 | 1.039 ± 0.037 | 1.040 ± 0.038 | 0.934 ± 0.034 | ||

| (n,2n)-High | 1.140 ± 0.041 | 1.091 ± 0.039 | 1.088 ± 0.039 | 0.927 ± 0.033 | ||

| (n,2n)-Low | 1.021 ± 0.037 | 0.985 ± 0.036 | 0.990 ± 0.036 | 0.942 ± 0.034 | ||

| Total | 1.084 ± 0.039 | 1.050 ± 0.038 | 1.048 ± 0.038 | 0.951 ± 0.034 | ||

| 13.2 | (n,el) | 1.135 ± 0.041 | 1.141 ± 0.041 | 1.138 ± 0.041 | 1.082 ± 0.039 | |

| (n,2n) | 1.137 ± 0.041 | 1.089 ± 0.039 | 1.088 ± 0.039 | 0.971 ± 0.035 | ||

| (n,2n)-High | 1.198 ± 0.043 | 1.144 ± 0.041 | 1.138 ± 0.041 | 0.967 ± 0.035 | ||

| (n,2n)-Low | 1.075 ± 0.039 | 1.033 ± 0.037 | 1.037 ± 0.037 | 0.976 ± 0.035 | ||

| Total | 1.137 ± 0.041 | 1.098 ± 0.040 | 1.097 ± 0.040 | 0.991 ± 0.036 | ||

| 73◦ | 4.4 | (n,el) | 0.968 ± 0.035 | 0.989 ± 0.036 | 0.985 ± 0.036 | 0.890 ± 0.033 |

| (n,2n) | 1.057 ± 0.038 | 1.032 ± 0.037 | 1.034 ± 0.037 | 0.937 ± 0.034 | ||

| (n,2n)-High | 1.123 ± 0.041 | 1.085 ± 0.039 | 1.085 ± 0.039 | 0.928 ± 0.034 | ||

| (n,2n)-Low | 0.985 ± 0.036 | 0.977 ± 0.035 | 0.979 ± 0.035 | 0.946 ± 0.034 | ||

| Total | 1.047 ± 0.038 | 1.028 ± 0.037 | 1.028 ± 0.037 | 0.932 ± 0.034 | ||

| 8.8 | (n,el) | 1.065 ± 0.039 | 1.056 ± 0.038 | 1.052 ± 0.038 | 0.967 ± 0.035 | |

| (n,2n) | 1.072 ± 0.039 | 1.039 ± 0.038 | 1.044 ± 0.038 | 0.933 ± 0.034 | ||

| (n,2n)-High | 1.139 ± 0.041 | 1.096 ± 0.040 | 1.101 ± 0.040 | 0.935 ± 0.034 | ||

| (n,2n)-Low | 1.006 ± 0.036 | 0.982 ± 0.035 | 0.987 ± 0.036 | 0.930 ± 0.034 | ||

| Total | 1.072 ± 0.039 | 1.041 ± 0.038 | 1.044 ± 0.038 | 0.936 ± 0.034 | ||

| 13.2 | (n,el) | 1.093 ± 0.040 | 1.091 ± 0.040 | 1.091 ± 0.040 | 1.031 ± 0.037 | |

| (n,2n) | 1.137 ± 0.041 | 1.095 ± 0.040 | 1.099 ± 0.040 | 0.984 ± 0.036 | ||

| (n,2n)-High | 1.201 ± 0.043 | 1.151 ± 0.042 | 1.154 ± 0.042 | 0.981 ± 0.035 | ||

| (n,2n)-Low | 1.074 ± 0.039 | 1.040 ± 0.038 | 1.045 ± 0.038 | 0.987 ± 0.036 | ||

| Total | 1.131 ± 0.041 | 1.095 ± 0.040 | 1.098 ± 0.040 | 0.989 ± 0.036 | ||

| 107◦ | 4.4 | (n,el) | 0.970 ± 0.036 | 1.007 ± 0.037 | 1.000 ± 0.037 | 0.938 ± 0.034 |

| (n,2n) | 1.048 ± 0.038 | 1.084 ± 0.039 | 1.084 ± 0.039 | 0.967 ± 0.035 | ||

| (n,2n)-High | 1.133 ± 0.041 | 1.173 ± 0.042 | 1.169 ± 0.042 | 0.978 ± 0.035 | ||

| (n,2n)-Low | 0.972 ± 0.035 | 1.006 ± 0.036 | 1.009 ± 0.036 | 0.958 ± 0.035 | ||

| Total | 1.040 ± 0.038 | 1.077 ± 0.039 | 1.076 ± 0.039 | 0.964 ± 0.035 | ||

| 8.8 | (n,el) | 0.885 ± 0.032 | 0.913 ± 0.033 | 0.907 ± 0.033 | 0.862 ± 0.031 | |

| (n,2n) | 1.003 ± 0.036 | 1.024 ± 0.037 | 1.024 ± 0.037 | 0.910 ± 0.033 | ||

| (n,2n)-High | 1.092 ± 0.039 | 1.111 ± 0.040 | 1.110 ± 0.040 | 0.936 ± 0.034 | ||

| (n,2n)-Low | 0.934 ± 0.034 | 0.957 ± 0.035 | 0.958 ± 0.035 | 0.890 ± 0.032 | ||

| Total | 0.991 ± 0.036 | 1.013 ± 0.037 | 1.013 ± 0.037 | 0.905 ± 0.033 | ||

| 13.2 | (n,el) | 1.007 ± 0.037 | 1.020 ± 0.037 | 1.006 ± 0.037 | 0.968 ± 0.035 | |

| (n,2n) | 1.071 ± 0.039 | 1.082 ± 0.039 | 1.085 ± 0.039 | 0.961 ± 0.035 | ||

| (n,2n)-High | 1.150 ± 0.042 | 1.161 ± 0.042 | 1.163 ± 0.042 | 0.976 ± 0.035 | ||

| (n,2n)-Low | 1.009 ± 0.036 | 1.019 ± 0.037 | 1.024 ± 0.037 | 0.948 ± 0.034 | ||

| Total | 1.065 ± 0.038 | 1.076 ± 0.039 | 1.078 ± 0.039 | 0.961 ± 0.035 | ||

| 122◦ | 4.4 | (n,el) | 0.891 ± 0.033 | 0.939 ± 0.035 | 0.919 ± 0.034 | 0.888 ± 0.033 |

| (n,2n) | 0.941 ± 0.034 | 0.983 ± 0.036 | 0.981 ± 0.035 | 0.875 ± 0.032 | ||

| (n,2n)-High | 1.021 ± 0.036 | 1.083 ± 0.039 | 1.080 ± 0.039 | 0.894 ± 0.032 | ||

| (n,2n)-Low | 0.877 ± 0.032 | 0.904 ± 0.033 | 0.902 ± 0.033 | 0.860 ± 0.031 | ||

| Total | 0.936 ± 0.034 | 0.979 ± 0.035 | 0.976 ± 0.035 | 0.876 ± 0.032 | ||

| 8.8 | (n,el) | 0.865 ± 0.032 | 0.885 ± 0.032 | 0.869 ± 0.032 | 0.836 ± 0.031 | |

| (n,2n) | 0.952 ± 0.034 | 0.989 ± 0.036 | 0.986 ± 0.036 | 0.878 ± 0.032 | ||

| (n,2n)-High | 1.024 ± 0.037 | 1.075 ± 0.039 | 1.066 ± 0.039 | 0.903 ± 0.033 | ||

| (n,2n)-Low | 0.900 ± 0.033 | 0.927 ± 0.034 | 0.929 ± 0.034 | 0.860 ± 0.031 | ||

| Total | 0.945 ± 0.034 | 0.980 ± 0.035 | 0.976 ± 0.035 | 0.875 ± 0.032 | ||

| 13.2 | (n,el) | 0.931 ± 0.034 | 0.950 ± 0.035 | 0.935 ± 0.034 | 0.909 ± 0.033 | |

| (n,2n) | 0.987 ± 0.036 | 1.019 ± 0.037 | 1.020 ± 0.037 | 0.905 ± 0.033 | ||

| (n,2n)-High | 1.057 ± 0.038 | 1.096 ± 0.040 | 1.095 ± 0.040 | 0.924 ± 0.033 | ||

| (n,2n)-Low | 0.936 ± 0.034 | 0.962 ± 0.035 | 0.964 ± 0.035 | 0.891 ± 0.032 | ||

| Total | 0.982 ± 0.035 | 1.013 ± 0.037 | 1.013 ± 0.037 | 0.905 ± 0.033 |

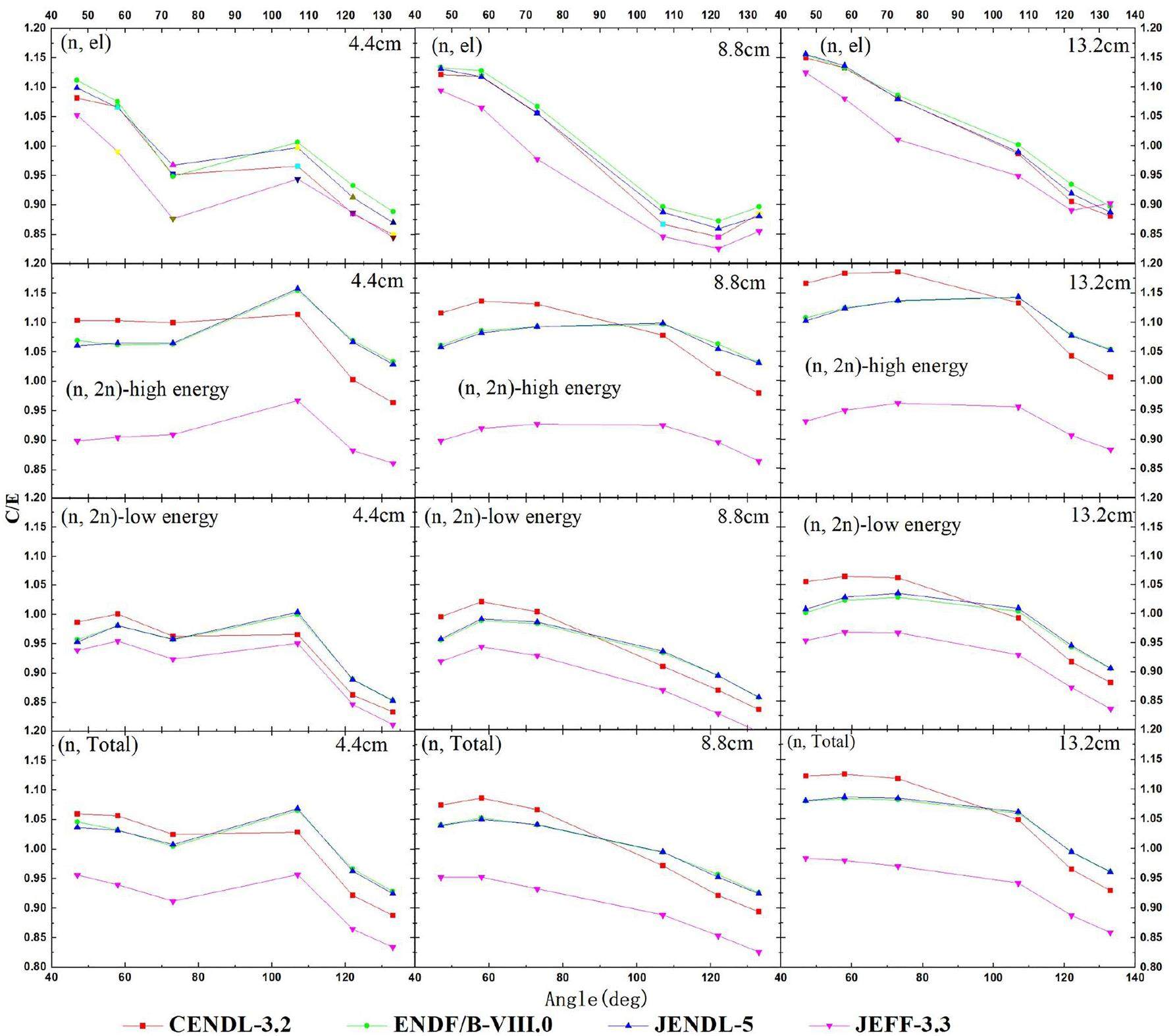

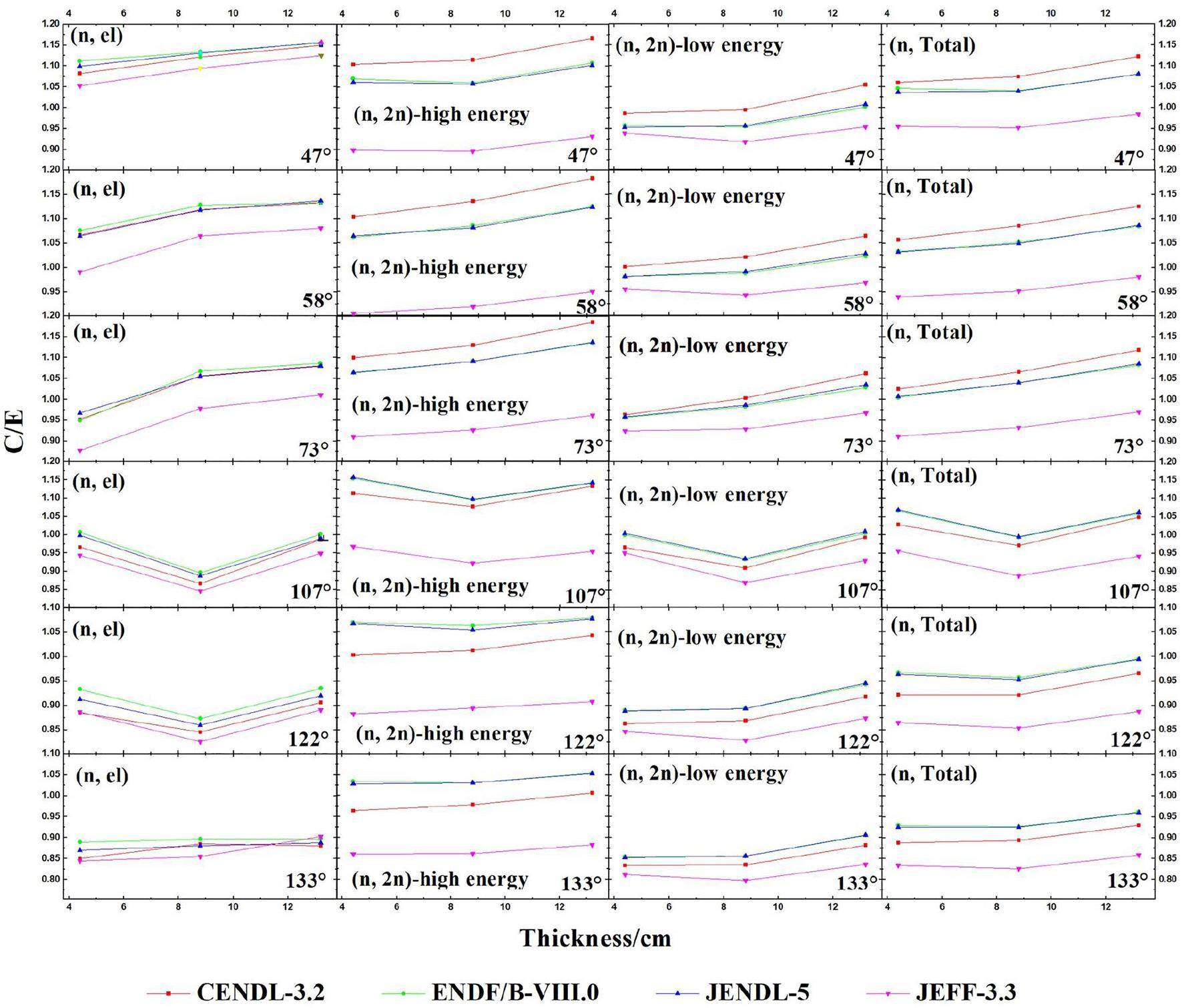

Trends of C/E Values Across Different Energy Ranges with Angle and Thickness Variation

The trends of the C/E values for different energy ranges in various databases as a function of the angle and thickness are shown in Figs. 20 and 21. From these figures, we can observe the following.

1. The C/E values from the JEFF-3.3 database were significantly lower than those from the other three databases, and were generally less than 1. This was particularly evident in the (n, 2n) energy range at larger angles, where the C/E values were consistently below 0.9.

2. In the elastic scattering energy range, all four databases show a marked decrease in the C/E values as the angle increases. At angles of 47 and 58, the C/E values were approximately 1.1, while at 122 and 133, they decreased to approximately 0.85. The C/E values from ENDF/B-VIII.0 database were slightly higher than those from the other three databases. At smaller angles of 47, 58, and 73, the C/E values for all databases exhibited a gradual increase with increasing thickness, whereas at larger angles (107, 122, and 133), the C/E values remained relatively constant with respect to thickness.

3. For the CENDL-3.2, ENDF/B-VIII.0, and JENDL-5 databases, the C/E values in the high-energy region of the (n, 2n) outgoing neutron spectrum were greater than 1 at small angles and increased with the thickness. At larger angles, the C/E values approached 1 with minimal changes as the thickness increased. In the low-energy region of the (n, 2n) outgoing neutron spectrum, the C/E values were close to 1 at small angles but less than 1 at larger angles, with a slight increase observed as the thickness increased. Among these databases, the CENDL-3.2 database shows the most pronounced variation in C/E values with angle, with the highest values at small angles and the lowest at large angles.

Result Analysis

To analyze the large deviations in the C/E values described above, the NDplot program was used to extract and compare relevant 9Be data from the CENDL-3.2, ENDF/B-VIII.0, JENDL-5, and JEFF-3.3 databases.

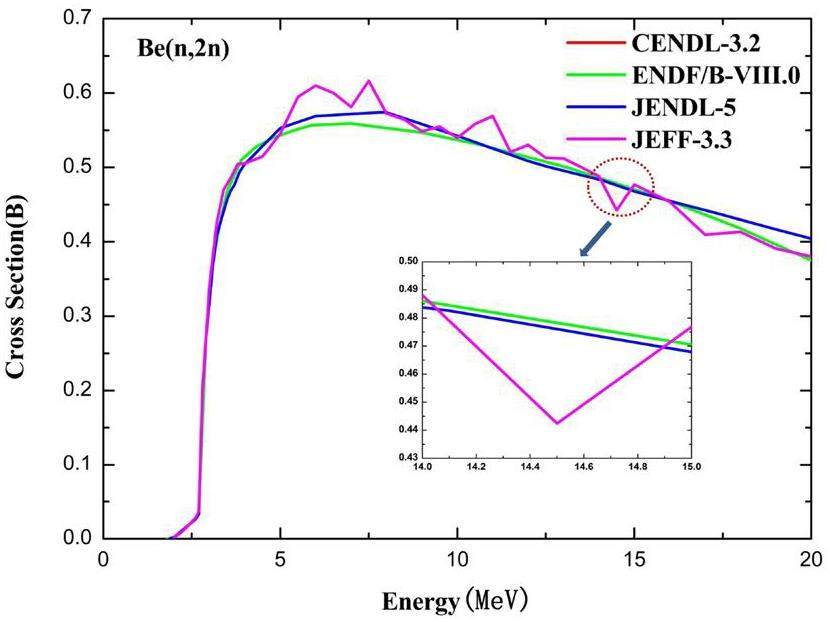

1. The (n, 2n) reaction cross-section curves from all four databases were extracted and compared, as shown in Fig. 22. In the JEFF-3.3 database, the (n, 2n) reaction cross-section was derived by summing the cross-sections of the 16 reaction channels (MT = 875 to 890). It is apparent that the (n, 2n) cross-section in JEFF-3.3 is significantly lower than those of the other databases around 14.5 MeV. At this energy point, the cross-section values extracted from the CENDL-3.2, ENDF/B-VIII.0, JENDL-5, and JEFF-3.3 databases are 0.4783 b, 0.4783 b, 0.4760 b, and 0.4424 b, respectively. The cross-section value for JEFF-3.3 is more than 7% lower than those of the other three databases, which is likely the main reason for the significant deviation between the simulation results and experimental data for JEFF-3.3.

2. The elastic scattering angle distributions for neutrons interacting with 9Be at 14.5 MeV were also extracted and compared for the four databases, as shown in Fig. 23. Overall, the evaluated databases tend to overestimate the differential cross-sections at smaller angles (47°, 58°, and 73°), and underestimate them as the angle increases. At smaller angles, the differential cross-section deviations for all four databases are relatively small and consistently higher than the experimental data. At 107, the ENDF/B-VIII.0 and JENDL-5 databases predict larger differential cross-sections compared to CENDL-3.2 and JEFF-3.3. At 122° and 133°, the values from all four databases are closely aligned. However, at larger angles, particularly at 133°, all databases significantly underestimate the differential cross-section, as shown by comparisons with experimental data from the EXFOR database.

Conclusion

This study presents a comprehensive analysis of neutron interactions with beryllium (9Be) through a shielding integral experiment, utilizing neutron time-of-flight spectra measured at various sample thicknesses and angles. The experimental data were compared with simulated results obtained from four widely used nuclear data libraries: CENDL-3.2, ENDF/B-VIII.0, JENDL-5, and JEFF-3.3. The results provide valuable insights into the performance of these libraries, shedding light on their applicability for neutron transport simulations involving beryllium.

The experimental setup, designed to capture high-quality neutron spectra, covers a range of neutron energies and angles. Neutron leakage spectra were measured for beryllium samples with thicknesses of 4.4 cm, 8.8 cm, and 13.2 cm at six different angles (47°, 58°, 73°, 107, 122°, and 133°), producing 18 sets of data. These measurements allowed for a thorough comparison with the simulated results from each library, thereby providing a detailed evaluation of their predictive accuracy.

The analysis revealed that in the elastic scattering energy region, the simulations from CENDL-3.2, ENDF/B-VIII.0, and JENDL-5 generally exhibited good agreement with the experimental data at small angles, although they slightly overestimated the results at small angles. At larger angles, the simulations deviated from the experimental data. In contrast, JEFF-3.3 consistently underestimated the experimental results across all angles, with the largest discrepancies occurring at larger angles. In the (n, 2n) reaction energy region, CENDL-3.2 showed notable deviations in spectral shape, whereas ENDF/B-VIII.0 and JENDL-5 provided good agreement at small angles but underestimated the results at larger angles. JEFF-3.3 demonstrated significant underestimation at all angles, with the largest discrepancies occurring in the high-energy part of the (n, 2n) reaction region.

Further analysis of the nuclear data libraries revealed that ENDF/B-VIII.0 and JENDL-5 libraries performed relatively well at small angles, and none of the libraries were fully consistent in simulating the neutron spectra at large angles, especially in the (n, 2n) reaction region. CENDL-3.2 showed a pronounced variation with angle and thickness, while JEFF-3.3 demonstrated consistent underestimation across all angular ranges.

These discrepancies highlight the need for further refinement of the nuclear data for beryllium, particularly in the (n, 2n) reaction region, where the differences were most significant. This study also emphasizes the importance of continuous experimental validation for improving the accuracy of nuclear data libraries. These findings highlight the need for more detailed and precise nuclear models to ensure reliable neutron transport simulations, which are critical for nuclear reactor design and radiation shielding applications.

In conclusion, the results of this study underscore the need to improve the consistency and accuracy of nuclear data for beryllium, particularly in high-energy neutron interactions, to enhance the precision of both experimental measurements and computational simulations in nuclear applications.

Current status and development of nuclear data research in China

. At. Energy Sci. Tech. 53, 1742-1746 (2019). https://doi.org/10.7538/yzk.2019.53.10.1742 (in Chinese)Dynamic in nuclear physics: integral experiment research on fusion neutronics

. 12, 29-33 (1995). https://doi.org/10.11804/NuclPhysRev.12.01.029 (in Chinese)Preliminary design and analysis of CFETR water-cooled ceramic breeding blanket neutronics test module

. Nucl. Fusion Plasma Phys. 37, 88-93 (2017). (in Chinese)Reactivity control schemes for fast spectrum space nuclear reactors

. Nucl. Eng. Des. 241 (2011) 1516-1528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nucengdes.2011.02.017Conceptual design of target station and neutron scattering spectrometer for spallation neutron source

. Nucl. Tech. (in Chinese) 28, 593-597 (2001).Energy-angle double-differential spectrum analysis of the 9Be(n,2n) reaction

. At. Energy Sci. Tech. 29, 360-365 (1995). (in Chinese) https://doi.org/10.7538/yzk.1995.29.04.0360Multiplication of 14 MeV neutrons in bulk beryllium

. Fusion Technol. 23, 51 (1993). https://doi.org/10.13182/FST93-A30119Measurement of neutron leakage from spherical shells of 238U, 232Th, Be, Pb with a central 14 MeV source

. At. Energy 63(1) (1987). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01125156Measurement of neutron multiplication in beryllium

. Fusion Technol. 19, 1919 (1991).Lawrence Livermore pulsed sphere benchmark analysis of MCNP ENDF/B-VI. Report LA-12885

(1994). https://doi.org/10.2172/10108696Measurement of neutron leakage energy spectrum in beryllium, lead, and iron

.Measurement of 14 MeV neutron multiplication in spherical beryllium shells

. Fusion Eng. Des. 28, 737 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1016/0920-3796(95)90105-1NEA/SINBAD fusion shielding benchmark database

, http://www.nea.fr/science/shielding/sinbad/kant/fzk-bea.htm (2006).Analysis of the Karlsruhe Neutron Transmission experiment using MCNP with various beryllium nuclear data

. Fusion Eng. Des. 55, 365 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0920-3796(01)00176-4Analysis of the KANT experiment on beryllium using TRIPOLI-4 Monte Carlo code

. Fusion Eng. Des. 86, 2246 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fusengdes.2011.04.078Measurement and analysis of an angular neutron flux on a beryllium slab irradiated with deuterium-tritium neutrons

. Nucl. Sci. Eng. 97, 220 (1987). https://doi.org/10.13182/NSE87-A23504The benchmark experiment on slab beryllium with D-T neutrons for validation of evaluated nuclear data

. Fusion Eng. Des. 105, 8 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fusengdes.2016.01.049Theoretical analysis of neutron double-differential cross-section on n+9Be reactions

. Commun. Theor. Phys. 54, 129-137 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1088/0253-6102/54/1/25Introduction to CIAE 600kVns pulsed neutron generator

.Development of high-intensity pulsed ns devices

.MCNP—A General Monte Carlo N-Particle Transport Code System, Version 4C, Report LA-13709-M (2000)

.CENDL-3.2: The new version of Chinese general purpose evaluated nuclear data library

. EPJ Web Conf. 239, 09001 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/202023909001ENDF/B-VIII.0: The 8th Major Release of the Nuclear Reaction Data Library with CIELO-project Cross Sections, New Standards and Thermal Scattering Data

. Nucl. Data Sheets 148, 1-142 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nucengdes.2011.02.017Japanese evaluated nuclear data library version 5: JENDL-5

. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 60, 1-60 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1080/00223131.2022.2141903Benchmarking and validation activities within JEFF project

. EPJ Web Conf. 146, 06004 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/201714606004Measurement of leakage neutron spectra from graphite cylinders irradiated with D-T neutrons for validation of evaluated nuclear data

. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 116, 185-189 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apradiso.2016.08.009Benchmarking of evaluated nuclear data for iron by a TOF experiment with slab samples

. Fusion Eng. Des. 145, 40-45 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fusengdes.2019.05.021Measurement and simulation of the leakage neutron spectra from Fe spheres bombarded with 14 MeV neutrons

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 182 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01329-6The benchmark experiment on slab iron with D-T neutrons for validation of evaluated nuclear data

. Ann. Nucl. Energy 132, 236-242 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anucene.2019.04.041Benchmarking of evaluated nuclear data for uranium by a 14.8 MeV neutron leakage spectra experiment with slab sample

. Ann. Nucl. Energy 37, 1456-1460 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anucene.2010.06.018Experiment on uranium slabs of different thicknesses with D-T neutrons and validation of evaluated nuclear data

. Fusion Eng. Des. 125, 9-17 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fusengdes.2017.10.021Benchmark experiment on slab 238-U with D‑T neutrons for validation of evaluated nuclear data

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 29 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01386-5Silicon carbide Schottky diode detector for fusion neutron yields monitoring using associated particle method

. Measurement 205,Performance of digital data acquisition system in gamma-ray spectroscopy

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 79 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00917-8A general-purpose digital data acquisition system (GDDAQ) at Peking University

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 975,Measurement and simulation of neutron leakage spectrum with different sized polyethylene samples

. Atomic Energy Science and Technology 51(2), 223-229 (2017). https://doi.org/10.7538/yzk.2017.51.02.0223 (in Chinese)The authors declare that they have no competing interests.