Introduction

The Dirac equation is a fundamental relativistic wave equation in quantum mechanics that describes the behavior of spin-1/2 massive particles. It is a generalization of the Schrödinger equation to account for relativistic effects. Solving Dirac equations with various potentials has played an important role in many areas of fundamental physics, including atomic, nuclear, hadron, and molecular systems. The Dirac equation has been studied in the context of nuclear physics, especially within the framework of relativistic mean-field theories [1, 2] and in explaining various single-particle effects [3-5]. One of the most important aspects of contemporary nuclear physics is the study of the shell evolution of exotic nuclei, which refers to the potentially dramatic changes in the shell structure as one approaches driplines with excessive protons or neutrons [6]. The evolution of the shell structure, which is crucial for our understanding of nuclear stability as well as the origin of heavy elements, can be induced by the isospin dependence of the spin and tensor potentials in various mean-field model approaches. The Dirac equation is unique for such studies because it provides not only insight into the origin of spin-orbital potentials as the competition between scalar and vector potentials [1] but also the possibility of adding a tensor potential at the mean field level. This study focuses on numerically solving the Dirac equation with scalar, vector, and tensor potentials. We hope that it can be a useful tool for studying the structure of exotic nuclei, as well as other quantum systems where spin-orbit and tensor effects can be important.

Dirac equation solvers are not available in the nuclear physics community, except for the Fortran subroutine embedded in relativistic mean field codes [7, 8]. Previous works in other areas on solving the Dirac equation focused particularly on the vector potential and utilized various schemes. In Ref. [9] the finite element method is applied to solve the Dirac equation, which is validated to converge to within floating point solutions. The problems inherent in the numerical solutions of the Dirac equation owing to spurious solutions are discussed in Ref. [10], where a stabilized version of the finite element method is also applied. The mapped Fourier method was used to numerically address the Dirac equation in. [11]. In Ref. [12] evolutionary algorithms are used and demonstrated in a case study of a muon orbiting the 208Pb nucleus. The work of Ref. [13] also focuses on studying muonic atoms, and applies the shooting method to integrate the Dirac equation. Moreover, a power series expansion method was employed in Ref.[14]. The numerical aspects of solving the Dirac equation are discussed in Ref. [15]. Other important methods include the Woods-Saxon basis [16], complex momentum representation [17], analytic continuation in the coupling constant (ACCC) [18] and Green’s function methods [19, 20].

Our work solves the Dirac equation in spherical coordinate space by utilizing the shooting method with a Runge-Kutta 4 integration scheme. We have prepared the code, named DiracSVT, in three different popular programming languages: Python, Matlab, and C++. These are gradually becoming the staple in physics, replacing Fortran as a more modern, versatile, and modular alternative. We include scalar, vector, and tensor potentials of an isospin-dependent Wood-Saxon form in the Dirac equation [21]. The code is used to solve the available single-particle states around doubly magic nuclei, including 16O, 40Ca, 48Ca, 56Ni, 100Sn, 132Sn, and 208Pb. The same potential can also reproduce the shell structures of many open nuclei well over the entire nuclear chart.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the formulation of the Dirac equation with corresponding potentials and boundary conditions. Section 3 describes our method and the algorithm for solving the equation. Section 4 presents our results, and Sect. 5 discusses these results and presents an outlook on the possibilities for future extensions to this work.

Theory

We limit ourselves to spherical symmetry. The Dirac Hamiltonian H with a scalar potential

The potentials can be parameterized in a standard Woods-Saxon shape (see, e.g., [21, 24])

Quantities

The Coulomb potential is defined as

To handle unbound neutron resonance states with positive energy, we implement for large r similar boundary conditions to Eq. (26), as in [25]:

Method

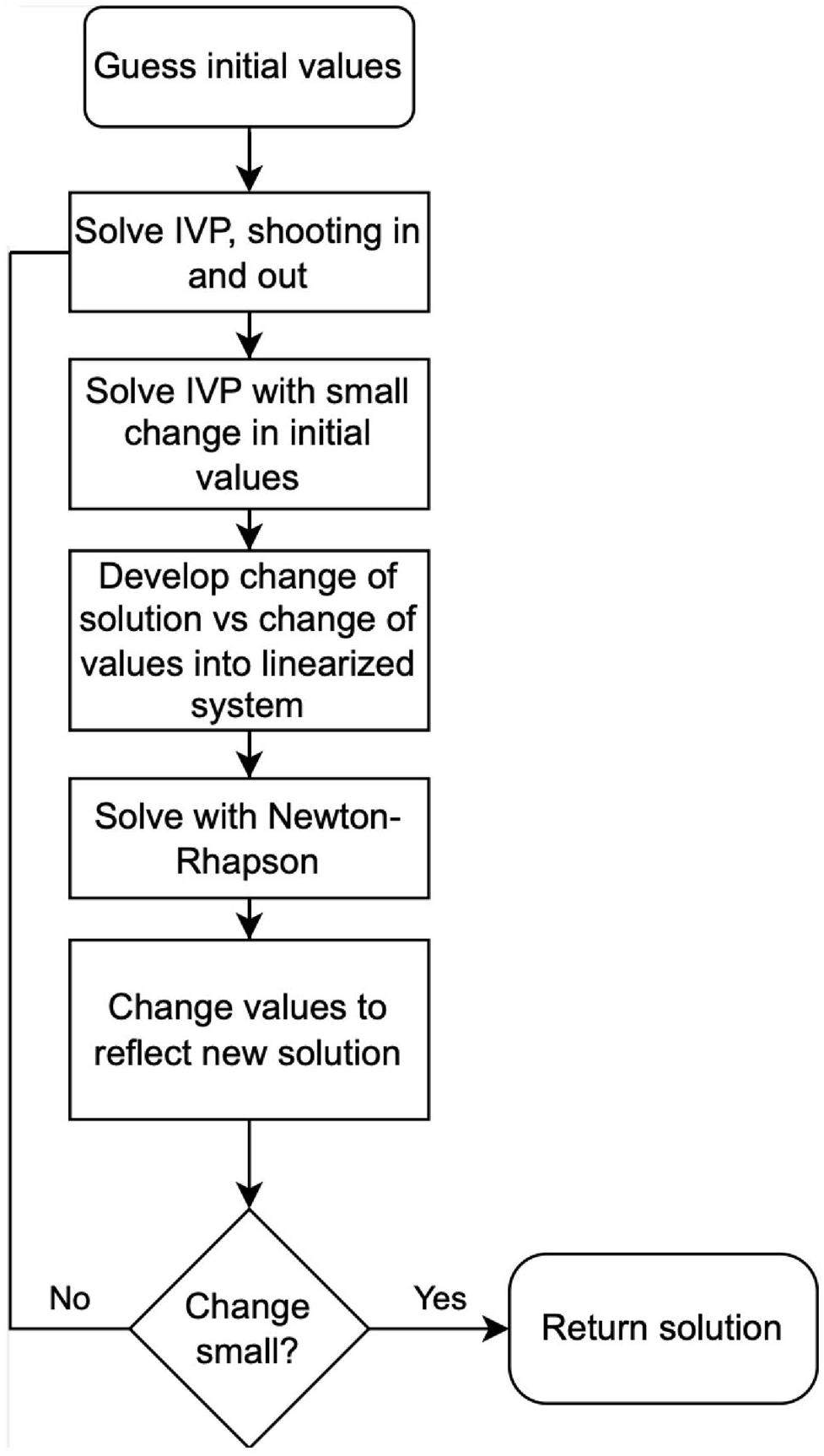

We attempt to combine an inner solution and an outer solution in what is known as the shooting method. The shooting method is a numerical scheme suitable for boundary-value problems. More specifically, the shooting method is a technique for solving a boundary value problem by transforming it into an Initial Value Problem (IVP). The method guesses the values of the boundary conditions at one end of the interval and then integrates the differential equation from that end using an ordinary differential equation solver. The estimated boundary values were adjusted until the solution satisfied the boundary conditions at the other end of the interval. No verification was performed for the number of nodes.

In our case, we employed shooting in two directions: outward and inward. We used the Runge-Kutta 4 integration scheme as the ordinary differential equation solver. This is akin to the methods employed in earlier studies, such as [27].

The outward shooting solution originated from the origin. However, setting r=0 causes a singularity in the model. To circumvent this, we set the inner point at a small distance

Inward shooting originates from an asymptotic distance from the origin

Both the outward and inward solutions can be used independently, as is. However, there is a major tendency for the calculated solutions of

To define the difference

To drive the differences to zero, we must define the change in the difference in terms of the parameters. We do this by linearizing through a first order Taylor expansion

Regarding the implementation of The numerical solver is written in three different languages: Python, MATLAB, and C++. It was developed and tested mainly for Linux, and the experiments were run on both Intel i7-2600 @3.40 GHz and AMD Ryzen 5 3600 @3.60 GHz. It is worth noting that the sensitivity of the solution to the precision of the system solution is very high in some cases. Changing the float precision can induce convergence to very different solutions. Similarly, merely varying the underlying linear algebra routine version (e.g., BLAS/LAPACK) also resulted in similar problems. As such, while the solver has been tested on different architectures, discrepancies remain regarding convergence that the reader should be aware of, resulting from different back-end libraries being utilized.

Numerical results

For example, we calculated the single-particle energies of all known single-particle states and single-hole states around the doubly magic nuclei for all three scenarios and all three language frameworks in which the solver is written. The binding energies against which the parameters were fitted were extracted from the experimental nuclear data. The parameters were fitted to minimize the RMS error between the numerical solutions and the experimental single-particle energies, as specified in Tables 2 and 3, so that they replicate the energies of the spin-orbit partners. The tensor potential is not included in the fitting of the parameters given below because of the scarcity of experimental data that can fully constrain its strength. Its effect is expected to be more significant as it approaches the neutron-rich nuclei around the neutron dripline.

In Table 1, the fitted parameters are given for Scenario 1, which were used to obtain the values in Tables 2 and 3. The difference between the scenarios relies on the value of δso: Scenario 2 is identical to Scenario 1 but takes δso=0 and Scenario 3 takes

| Scenario | V0 (MeV) | λ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -61.44 | 0.73 | 13.36 | 0.006515 | 0.003638 | 0.004867 |

| Nucleus | State | Experimental B | Matlab B | Python B | C++ B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16O | 1p1/2 | -15.66 | -15.8374 | -15.8374 | -15.8374 |

| 16O | 1d5/2 | -4.14 | -6.3839 | -6.3839 | -6.38387 |

| 16O | 2s1/2 | -3.27 | -3.8203 | -3.8203 | -3.82027 |

| 40Ca | 1d5/2 | -22.39 | -21.6375 | -21.6375 | -21.6375 |

| 40Ca | 2s1/2 | -18.19 | -15.0881 | -15.0881 | -15.0881 |

| 40Ca | 1d3/2 | -15.64 | -15.8337 | -15.8337 | -15.8337 |

| 40Ca | 1f7/2 | -8.36 | -9.4823 | -9.4823 | -9.48232 |

| 40Ca | 2p3/2 | -5.84 | -4.4926 | -4.4926 | -4.49257 |

| 40Ca | 2p1/2 | -4.2 | -2.7787 | -2.7787 | -2.77869 |

| 40Ca | 1f5/2 | -1.56 | -3.9294 | -3.9294 | -3.92936 |

| 48Ca | 1d5/2 | -15.61 | -19.6859 | -19.6859 | -19.6859 |

| 48Ca | 2s1/2 | -12.55 | -14.1267 | -14.1267 | -14.1267 |

| 48Ca | 1d3/2 | -12.53 | -15.1527 | -15.1527 | -15.1527 |

| 48Ca | 1f7/2 | -10 | -8.7770 | -8.7770 | -8.77702 |

| 48Ca | 2p3/2 | -4.6 | -4.2724 | -4.2724 | -4.27242 |

| 48Ca | 2p1/2 | -2.86 | -2.9638 | -2.9638 | -2.96378 |

| 48Ca | 1f5/2 | -1.2 | -4.2483 | -4.2483 | -4.2483 |

| 56Ni | 1f7/2 | -16.64 | -16.0488 | -16.0488 | -16.0488 |

| 56Ni | 2p3/2 | -10.25 | -9.1691 | -9.1691 | -9.16906 |

| 56Ni | 1f5/2 | -9.48 | -10.0171 | -10.0171 | -10.0171 |

| 56Ni | 2p1/2 | -9.13 | -7.2951 | -7.2951 | -7.29513 |

| 100Sn | 2p1/2 | -18.38 | -16.9797 | -16.9797 | -16.9797 |

| 100Sn | 1g9/2 | -17.93 | -17.4011 | -17.4011 | -17.4011 |

| 100Sn | 2d5/2 | -11.13 | -9.2034 | -9.2034 | -9.20345 |

| 100Sn | 1g7/2 | -10.93 | -11.1915 | -11.1915 | -11.1915 |

| 100Sn | 3s1/2 | -9.3 | -6.3580 | -6.3580 | -6.3580 |

| 100Sn | 1h11/2 | -8.6 | -7.6706 | -7.6706 | -7.6706 |

| 100Sn | 2d3/2 | -9.2 | -6.7376 | -6.7376 | -6.7376 |

| 132Sn | 1g7/2 | -9.75 | -10.9534 | -10.9534 | -10.9534 |

| 132Sn | 2d5/2 | -8.97 | -8.6191 | -8.6191 | -8.6191 |

| 132Sn | 3s1/2 | -7.64 | -6.4832 | -6.4832 | -6.4832 |

| 132Sn | 1h11/2 | -7.54 | -7.1366 | -7.1366 | -7.136 |

| 132Sn | 2d3/2 | -7.31 | -7.0763 | -7.0763 | -7.0763 |

| 132Sn | 2f7/2 | -2.47 | - | -1.3848 | - |

| 132Sn | 3p3/2 | -1.57 | -0.2211 | -16.8335 | -16.8335 |

| 132Sn | 1h9/2 | -0.86 | -2.8903 | -2.8903 | -2.8903 |

| 132Sn | 2f5/2 | -0.42 | 0.2823 | -19.1602 | -19.1602 |

| 208Pb | 1h9/2 | -11.4 | -12.4667 | -12.4667 | -12.4667 |

| 208Pb | 2f7/2 | -9.81 | -9.3144 | -9.3144 | -9.3144 |

| 208Pb | 1i13/2 | -9.24 | -9.7762 | -9.7762 | -9.7762 |

| 208Pb | 3p3/2 | -8.26 | -6.3349 | -6.3349 | -6.3349 |

| 208Pb | 2f5/2 | -7.94 | -7.3793 | -7.3793 | -7.3793 |

| 208Pb | 3p1/2 | -7.37 | -8.0489 | -23.3705 | -6.0271 |

| 208Pb | 2g9/2 | -3.94 | -2.5108 | -2.5108 | -2.5108 |

| 208Pb | 1i11/2 | -3.16 | -5.2959 | -5.2959 | -5.2959 |

| 208Pb | 1j15/2 | -2.51 | -2.2689 | -2.2689 | - |

| 208Pb | 3d5/2 | -2.37 | -0.2044 | -16.6099 | -16.6099 |

| 208Pb | 4s1/2 | -1.9 | -0.1299 | -14.2321 | -14.2321 |

| 208Pb | 2g7/2 | -1.44 | -0.2843 | -19.6005 | -19.6005 |

| Nucleus | State | Experimental B | Matlab B | Python B | C++ B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16O | 1p1/2 | -12.13 | -11.9334 | -11.9334 | -11.9334 |

| 16O | 1d5/2 | -0.6 | -2.9170 | -2.9170 | -2.9170 |

| 16O | 2s1/2 | -0.11 | -0.8547 | -0.8547 | -0.8547 |

| 16O | 1d3/2 | 4.688 | 4.7575 | 4.7575 | 4.7575 |

| 40Ca | 1d5/2 | -15.07 | -14.1180 | -14.1180 | -14.1180 |

| 40Ca | 2s1/2 | -10.92 | -7.7847 | -7.7847 | -7.7847 |

| 40Ca | 1d3/2 | -8.33 | -8.5334 | -8.5334 | -8.5334 |

| 40Ca | 1f7/2 | -1.09 | -2.5333 | -2.5333 | -2.5333 |

| 40Ca | 2p3/2 | 0.69 | 1.5992 | 1.5992 | 1.5992 |

| 48Ca | 1d5/2 | -21.47 | -22.4904 | -22.4904 | -22.4904 |

| 48Ca | 1d3/2 | -16.18 | -15.4556 | -15.4556 | -15.4556 |

| 48Ca | 2s1/2 | -16.1 | -14.2643 | -14.2643 | -14.2643 |

| 48Ca | 1f7/2 | -9.35 | -10.5523 | -10.5523 | -10.5523 |

| 48Ca | 2p3/2 | -6.44 | -3.2336 | -3.2336 | -3.2336 |

| 48Ca | 2p1/2 | -4.64 | 11.7435 | -0.9598 | 11.7435 |

| 56Ni | 1f7/2 | -7.17 | -6.9046 | -6.9046 | -6.9046 |

| 56Ni | 2p3/2 | -0.69 | -0.5831 | -0.5831 | -0.5831 |

| 56Ni | 1f5/2 | 0.33 | 8.5469 | 8.5469 | 8.5469 |

| 56Ni | 2p1/2 | 0.41 | 1.0938 | 1.0938 | 1.0938 |

| 100Sn | 1f5/2 | -8.71 | -7.0267 | -7.0267 | -7.0267 |

| 100Sn | 2p3/2 | -6.38 | -4.5904 | -4.5904 | -4.5904 |

| 100Sn | 2p1/2 | -3.53 | -3.0105 | -3.0105 | -3.0105 |

| 100Sn | 1g9/2 | -2.92 | -3.7950 | -3.7950 | -3.7950 |

| 100Sn | 1g7/2 | 3.9 | 1.9453 | 12.8860 | 12.8860 |

| 132Sn | 2p3/2 | -16.01 | -14.1064 | -14.1064 | -14.1064 |

| 132Sn | 1g9/2 | -15.71 | -18.0759 | -18.0759 | -18.0759 |

| 132Sn | 1g7/2 | -9.68 | -10.0481 | -10.0481 | -10.0481 |

| 132Sn | 2d5/2 | -8.72 | -6.9269 | -6.9269 | -6.9269 |

| 132Sn | 2d3/2 | -6.97 | -3.5858 | - | -28.5546 |

| 132Sn | 1h11/2 | -6.89 | -8.9825 | -8.9825 | -8.9825 |

| 208Pb | 1g7/2 | -12 | -13.3095 | -13.3095 | -13.3095 |

| 208Pb | 2d5/2 | -9.82 | -9.3826 | -9.3826 | -9.3826 |

| 208Pb | 1h11/2 | -9.36 | -13.2378 | -13.2378 | -13.2378 |

| 208Pb | 2d3/2 | -8.36 | -6.7044 | -6.7044 | -28.4605 |

| 208Pb | 3s1/2 | -8.01 | -5.3560 | -25.9307 | -25.9307 |

| 208Pb | 1h9/2 | -3.8 | -5.7976 | -5.7976 | -5.7976 |

| 208Pb | 2f7/2 | -2.9 | -1.6873 | -1.6873 | -27.3765 |

| 208Pb | 1i13/2 | -2.1 | -5.5308 | -5.5308 | - |

| 208Pb | 2f5/2 | -0.97 | 2.0965 | -20.8512 | -20.8512 |

| 208Pb | 3p3/2 | -0.68 | 3.5255 | -17.4631 | -17.4631 |

Some of the results are listed in Tables 2 and 3 for comparison purposes. The solutions from the three different code frameworks were identical within the numerical errors and were in reasonable agreement with the experimentally determined energies from Ref. [21]. The results for the three codes with the same inputs are listed. In some rare cases, one of the solvers can display a solution, while another diverges (marked as–in the tables). This seems likely to be the result of different languages using various routines to invert matrices. Moreover, the solver can sometimes converge to the energy levels of different states (e.g., the proton 2d3/2 and 2f7/2 states in 208Pb). This artifact can be easily spotted and is sensitive to the initial conditions and area of integration. We did not correct for comparison purposes. The convergence can be improved by slightly modifying the initial value, matching radius, and maximal radius. The values in Tables 2 and 3 are given for initial guesses equal to the experimental value for standardization. However, it may not always be the most suitable choice. In the case of unsuccessful convergence, this can be tweaked until the converged value improves. For some outliers, the code converges to a state with different nodes, which is easy to identify because the calculated energy differs significantly from the desired value.

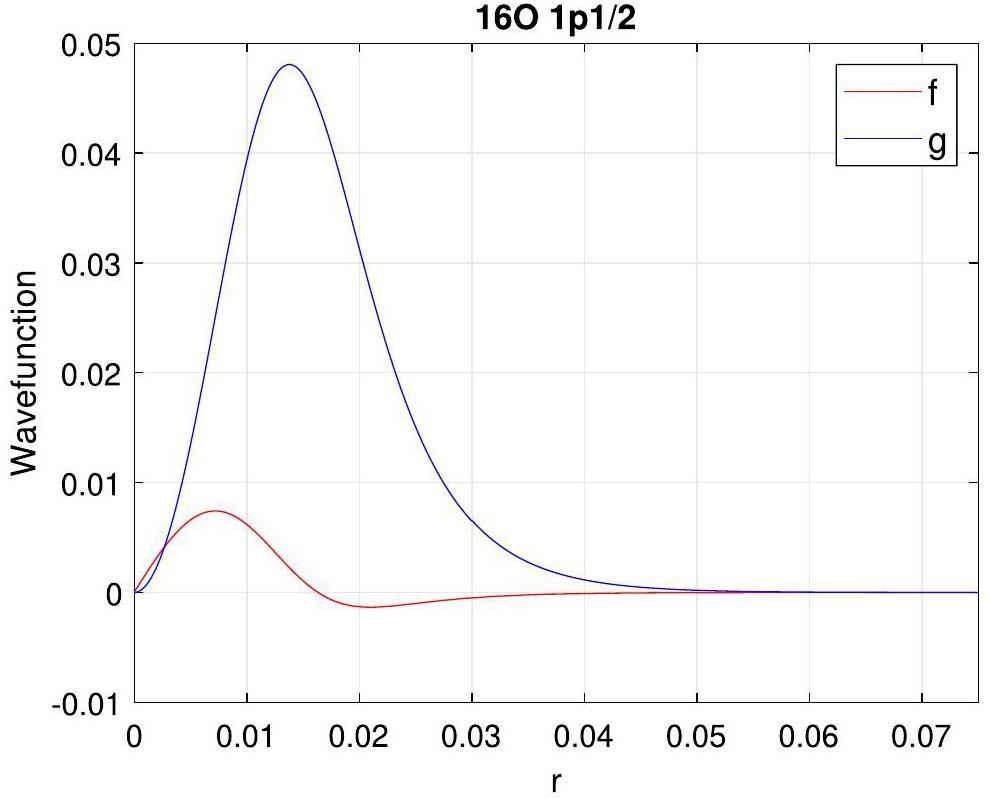

The solver also captured the waveform solution of the Dirac equation for the considered particle and state, as shown in Fig. 2. In the present work, we focus on bound states and very low-lying unbound states, as all quantities are assumed to be real. The bound and unbound states appear quite similar, except for the boundary conditions. This also implies that the code is not yet suitable for handling wide resonances.

Summary

We presented the Dirac equation solver DiracSVT, which solves the Dirac equation in coordinate space with Scalar, Vector, and tensor nuclear potentials. The code is written in three different languages and uses the shooting method with the Runge-Kutta 4 integration scheme. The above potentials were parameterized in the Saxon form. We show that the potential can reproduce the known single-particle states very well around all the doubly magic nuclei. This code is freely available in Ref. [28].

Relativistic mean field theory in finite nuclei

. Progress in Particle and Nuclear Physics 37, 193-263 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1016/0146-6410(96)00054-3Pseudospin as a relativistic symmetry

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 436-439 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.78.436Solving dirac equations on a 3d lattice with inverse hamiltonian and spectral methods

. Phys. Rev. C 95,Time-dependent dirac equation applied to one-proton radioactive emission

. (2022). https://doi.org/10.48550/ARXIV.2212.03271Evolution of shell structure in exotic nuclei

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 92,Computer program for the relativistic mean field description of the ground state properties of even-even axially deformed nuclei

. Computer Physics Communications 105, 77-97 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-4655(97)00022-2Dirhb-a relativistic self-consistent mean-field framework for atomic nuclei

. Computer Physics Communications 185, 1808-1821 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2014.02.027Numerical investigations of the dirac equation and bound state quantum electrodynamics in atoms: a thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy in physics at massey university, albany, new zealand

. Ph.D. thesis,Stabilized finite element method for the radial Dirac equation

. Journal of Computational Physics 236, 426-442 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcp.2012.11.020Numerical solution of the Dirac equation by a mapped fourier grid method

. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General 38, 3157 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1088/0305-4470/38/14/007DiracSolver: A tool for solving the Dirac equation

. Computer Physics Communications 236, 237-243 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2018.10.010Mudirac: A Dirac equation solver for elemental analysis with muonic X-rays

. X-Ray Spectrometry 50, 180-196 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1002/xrs.3212radial: A fortran subroutine package for the solution of the radial schrödinger and dirac wave equations

. Computer Physics Communications 240, 165-177 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2019.02.011Solving the radial Dirac equations: a numerical odyssey

. European journal of physics 32, 217 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1088/0143-0807/32/1/021Spherical relativistic hartree theory in a woods-saxon basis

. Physical Review C 68,. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevc.68.034323The complex momentum representation approach and its application to low-lying resonances in 17O and 29,31f

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 34, 5 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01159-yAnalytic continuation of single-particle resonance energy and wave function in relativistic mean field theory

. Physical Review C 70,. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevc.70.034308Green’s function method for single-particle resonant states in relativistic mean field theory

. Physical Review C 90,. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevc.90.054321Green’s function method for the single-particle resonances in a deformed dirac equation

. Physical Review C 101,. https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevc.101.014321Shell evolution and its indication on the isospin dependence of the spin-orbit splitting

. Physics Letters B 724, 247-252 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2013.06.018Dirac equation with scalar and vector quadratic potentials and Coulomb-like tensor potential

. Physics Letters A 373, 616-620 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physleta.2008.12.029Dirac equation under scalar, vector, and tensor cornell interactions

. Advances in High Energy Physics 2012, 1-17 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/707041The Woods–Saxon potential in the Dirac equation

. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General 35, 689 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1088/0305-4470/35/3/314On the boundary conditions for the Dirac equation

. European Journal of Physics 18, 315 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1088/0143-0807/18/5/001Relativistic continuum hartree-bogoliubov theory with both zero range and finite range gogny force and their application

. Nuclear Physics A 635, 3-42 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1016/s0375-9474(98)00178-xThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.