Introduction

The Baryonic Matter at Nuclotron (BM@N) is the first fixed target experiment at the NICA accelerator complex [1]. The BM@N research program aims to study the equation of state (EoS) of nuclear matter at high baryon densities achieved in nucleus-nucleus collisions with kinetic energies of projectile nuclei up to 4.65A GeV [2]. The EoS links the pressure, density, and temperature achieved in a nucleus-nucleus collision event. The EoS includes a symmetry energy term to characterize the isospin asymmetry of nuclear matter, which is crucial for understanding the properties of astrophysical objects such as neutron stars [3]. It was shown that the neutron-to-proton ratio, in terms of yields and directed flow, is sensitive to the symmetry energy contribution to the EoS of high-density nuclear matter [4]. The BM@N detector system can measure the anisotropic flow of protons using a hybrid tracking system, together with TOF and FHCal detectors [5]. However, to measure the yields and directed flow of neutrons, additional detectors and identification methods are required.

To date, only two neutron detectors have been developed, namely, LAND [6] and NeuLAND [7]. Both were developed and constructed at the GSI in Darmstadt, Germany, to measure neutrons from heavy-ion collisions at beam energies below 1A GeV. The LAND consists of 10 mutually perpendicular layers with 20 individual scintillation detectors in each layer. Each individual detector consists of 10 alternating layers of plastic scintillation and iron plates with a thickness of 0.5 cm and with a total size of 10 cm × 10 cm × 200 cm, and two photomultiplier tubes read the light from the two ends. The full geometric size of the LAND detector is 200 cm × 200 cm × 100 cm. The typical resolution of time measurements with LAND was reported to be 250ps.

A new large-area neutron detector, NeuLAND [7] was designed and partially constructed to study the properties of nuclear matter produced in collisions of radioactive nuclei within the R3B project at the FAIR accelerator facility at the GSI. In contrast to LAND, NeuLAND consists only of active layers of plastic scintillation detectors with a size of 250 cm × 5 cm × 5 cm. The light from the opposite ends of the detectors is read using two photomultiplier tubes. NeuLAND is composed of 60 active layers with 50 scintillation detectors in each layer, and has a total size of 250 cm × 250 cm × 300 cm. The time resolution of NeuLAND was estimated to be 150 ps, the spatial resolution of the first interaction point of the neutron was approximately 1.5 cm, and the efficiency of detecting each neutron in an event was better than 95% for kinetic energies of 400 – 1000 MeV.

Considering the significantly higher energy (up to 4 GeV) of the neutrons produced in nucleus-nucleus collisions in the BM@N experiment and the intense development of hadron showers in the detector volume at these energies, it is impossible to use large-size neutron detectors, such as LAND and NeuLAND. Therefore, the new concept of a Highly Granular Neutron Detector (HGND) has been proposed. Instead of the long scintillator plates used in LAND and NeuLAND, the highly granular transverse structure of the active elements of the detector is used to identify neutrons and measure their energy with the time-of-flight method with good resolution. At the same time, multilayer longitudinal sampling makes it possible to achieve high-efficiency neutron detection [8]. It was proposed to build the active layers of the HGND as (11×11) arrays of small scintillator cells with individual light readout by silicon photomultipliers (SiPM). Each cell is expected to provide a time resolution of ∼150 ps. Copper absorbers placed between the active layers provide a high probability of neutron interaction with the HGND.

In addition to studies of neutron yields and flow in hadronic interactions of colliding nuclei, it is also interesting to study the electromagnetic dissociation (EMD) of beam nuclei in ultraperipheral collisions (UPC), resulting in the emission of forward neutrons. EMD is usually represented by the emission of single or very few neutrons, producing a single residual nucleus [9].

In this paper, the design and performance of a compact HGND prototype are presented. The capability of the HGND prototype to identify forward neutrons produced in the nuclear fragmentation and electromagnetic dissociation of 3.8A GeV 124Xe projectiles on a CsI target and reconstruct the neutron energies was studied in the BM@N experiment.

The paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, the design of the HGND prototype is presented. In Sect. 3 the event selection criteria and procedures for reconstructing the kinetic energy of the neutrons are described. After that, in Sect. 4, the energy spectra of neutrons are compared using Monte Carlo modeling, and the acceptance and efficiency of neutron detection by the HGND prototype are estimated. The results are summarized in the conclusion in Sect. 5.

Highly Granular Neutron Detector (HGND) and its prototype

Concept of the HGND

The original concept of the full-scale HGND consisting of 16 alternating active layers of 121 plastic scintillation detectors grouped in the 11 × 11 array, with copper absorber plates in between, was presented in detail in [8]. The absorber plates (44 cm × 44 cm × 3 cm) and scintillator layers (44 cm × 44 cm × 2.5 cm) will be mounted on a common support frame. The total length of the HGND is approximately 1 m and corresponds approximately to three nuclear interaction lengths λint. The first scintillation layer of the HGND will be used as a VETO detector for the charged particles. The scintillator layers will be assembled from 4 cm × 4 cm × 2.5 cm plastic scintillators (cells) based on polystyrene with additions of 1.5% paraterphenyl and 0.01% POPOP produced at JINR. The light readout from the center of the entrance surface of each cell will be conducted with EQR15 11-6060D-S silicon photomultipliers [10, 11] placed on a printed circuit board (PCB) that hosts a preamplifier and Low-Voltage Differential Signal (LVDS) comparators, generating Time over Threshold (ToT) [12] signals for the read-out schematics. Methods to identify neutrons in high-multiplicity neutron events in the presence of a background from charged particles and photons are currently under development. More technical details of the HGND design, as well as the results of the simulations, can be found in [8].

Design of the HGND prototype

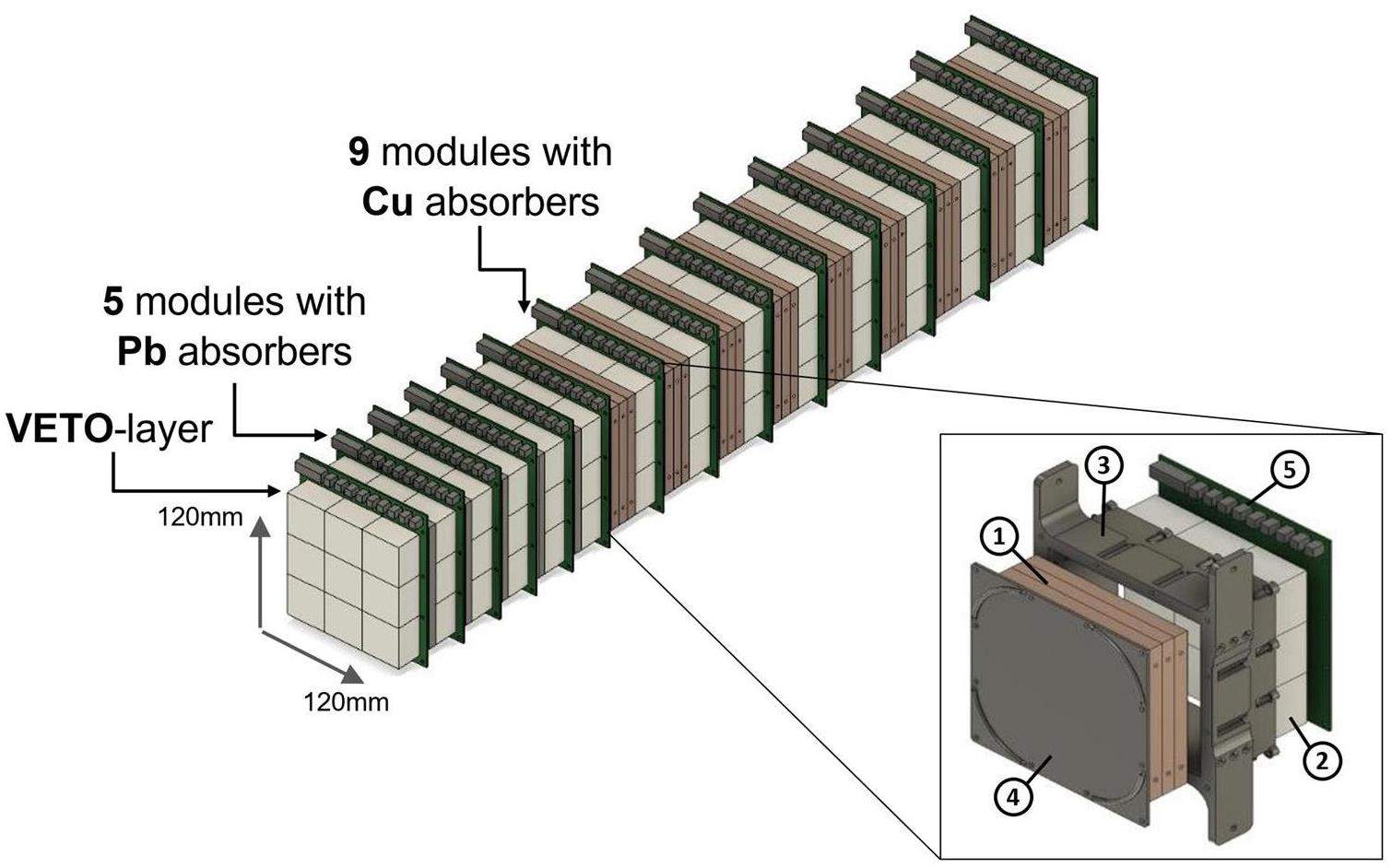

To validate the concept of a full-scale HGND, a small HGND prototype was designed and constructed. The prototype consists of 15 scintillator layers sequentially arranged one after another, with absorber layers in between [13], as shown in Fig. 1. The first scintillator layer (VETO layer) was used as the VETO for charged particles.

The first five modules of the HGND prototype placed after the VETO layer had 8 mm thick lead absorbers. This section is used to study in detail the influence of the γ-background on neutron identification and to develop methods for its rejection. The total length of this part is approximately 7.5 X0 radiation lengths but only 0.42 λint nuclear interaction lengths. The remaining part of the HGND prototype consists of nine modules with 30 mm thick copper absorbers and has a total interaction length of approximately 2 λint.

The transverse size of the detector is 12 cm × 12 cm. The total length of the HGND prototype is 82.5 cm, which corresponds to a 2.5 λint nuclear interaction length. The fully assembled HGND prototype, weighing approximately 100 kg, was mounted on a specially designed and manufactured wheeled frame at a height of 215 cm from the floor level in the plane of the beam axis. This allowed the HGND prototype to be moved to different positions and angles relative to the beam axis.

Each scintillator layer consists of a 3 × 3 matrix of individual scintillators with a transverse area of 4 cm × 4 cm and thickness of 2.5 cm. Light from each of the nine scintillators is read out by an individual SiPM (Hamamatsu S13360-6050PE) [14] with a sensitive area of 6 mm × 6 mm, mounted on a four-layer PCB with readout electronics, necessary connectors, and a sensor for temperature correction. These SiPMs were used in the HGND prototype because of the limited availability of the EQR15-11-6060D-S units at the time of prototype construction. However, the full-scale HGND will adopt EQR15-11-6060D-S SiPMs owing to their lower cost and superior timing resolution, as demonstrated in electron-beam tests [11]. Each of the nine readout channels consists of a photodetector, input amplifier, and buffer amplifier with 50 Ω line capability. Every PCB has voltage regulators for the positive and negative supply of amplifiers. This board was directly attached to the scintillators in the layer. The absorber, scintillators, and PCB with photodetectors and electronics were packaged in a light-protective module made by 3D printing.

The bias voltage to the modules was supplied by a power supply system consisting of a main power supply with remote digital control and a cascade of boards on a loop cable. Each board contains a set of DACs that correct the total bias voltage in the channels, a microcontroller that controls the DACs, and implements temperature correction based on the temperature sensor readings. After the amplifiers, the signals are transmitted via 2 m cables to the TQDC [15], which is included in the main data acquisition system.

One of the most important characteristics of a time-of-flight neutron detector is its temporal resolution. The time resolution of the scintillation cells of the HGND prototype measured with cosmic muons is 200 ± 4 ps [16]. Considering the resolution of the start trigger, the estimated total time resolution of the HGND prototype in the experiment is approximately 270 ps.

Measurements of neutrons from collisions of 3.8AA GeV 124Xe124Xe with CsI target

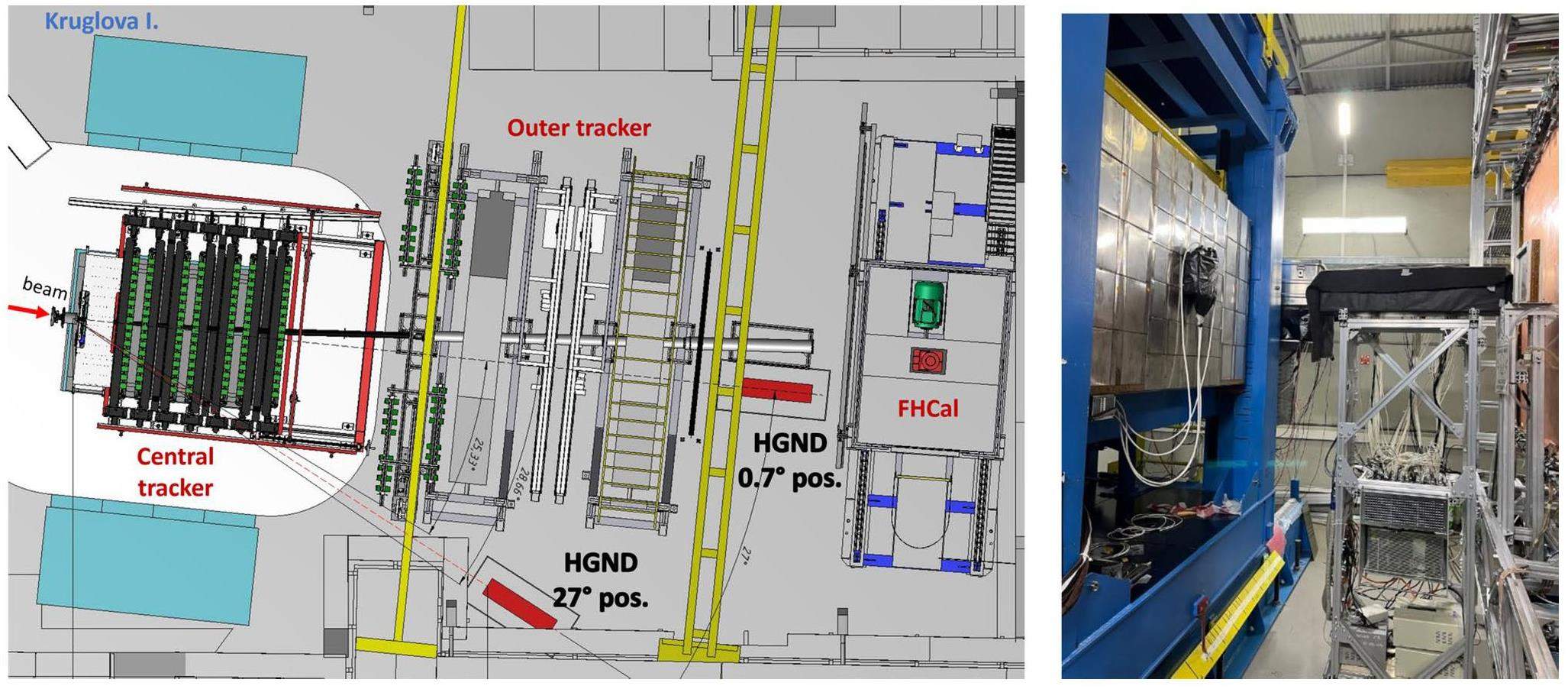

The HGND prototype was tested in late 2022 and early 2023 in a physics run of the BM@N experiment to study 124Xe–CsI collisions at the kinetic energy of the xenon projectile of 3.8A GeV. A CsI target with a thickness of 1.75 mm, corresponding to a nuclear interaction probability of 2%, is installed inside the SP-41 analyzing magnet (near its entrance), and the initial ion beam is slightly deflected by the magnetic field (to approximately 0.7°) relative to its initial direction. Therefore, the prototype was used in two main positions: at 0.7° relative to the undeflected primary beam at a distance of 8.35 m from the target to test and calibrate the detector with known spectator neutron energy; and at 27° relative to the beam at a distance of 5.89 m from the target to measure the neutron spectrum in the mid-rapidity region, as shown in Fig. 2.

In this study, the performance of the HGND prototype for detecting forward neutrons from nuclear fragmentation and EMD of 124Xe projectiles in interactions with target nuclei was investigated by placing the detector at the 0.7° position with respect to the initial 124Xe beam.

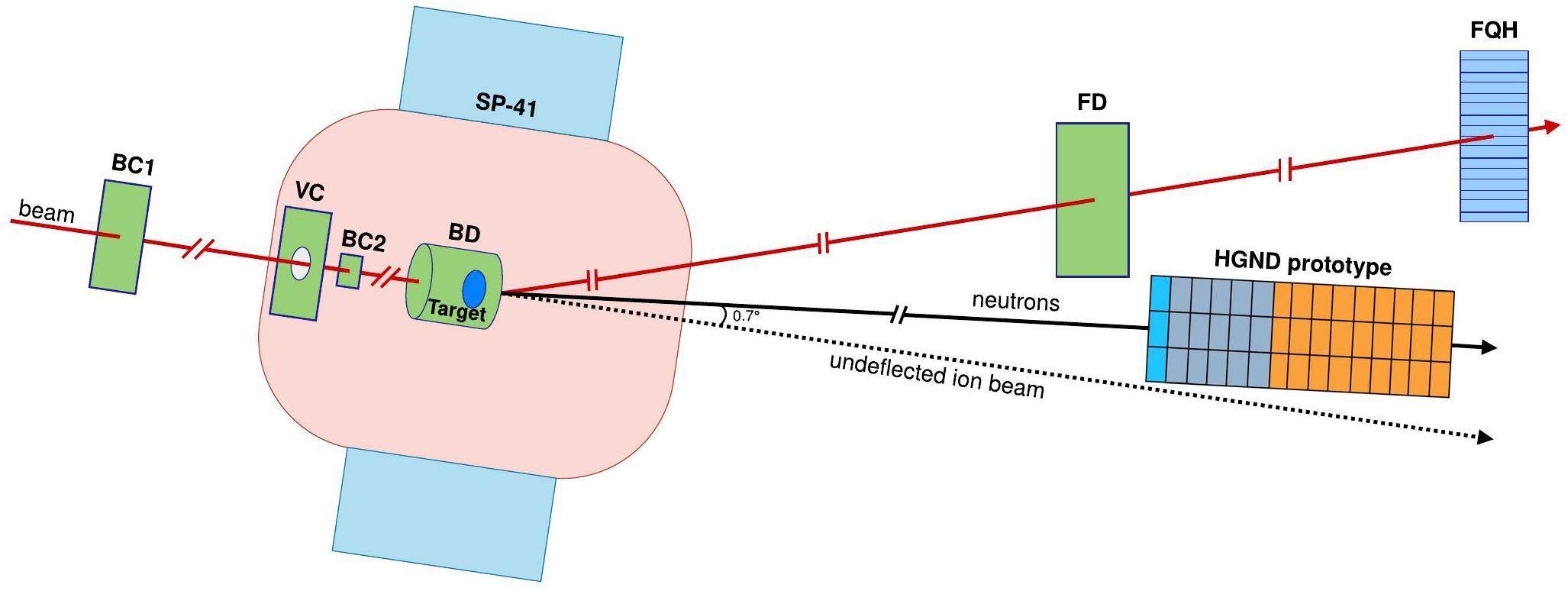

Selection criteria for hadronic interaction events and EMD leading to neutron emission

There are several triggers for hadronic interactions in the BM@N experiment [1]. The Beam Trigger (BT) was generated by the coincidence of the signals of the two Beam Counters (BC1 and BC2) and the absence of a signal from the Veto Counter (VC). The Central Collisions Trigger (CCT) is used to analyze hadronic interactions corresponding to central and semi-central collision events, with centrality ranging from 0 to approximately 60%. It consists of the BT trigger, the signal from the Fragment Detector (FD), which is required to be below the threshold corresponding to non-interacting beam nuclei, and the signal from the Barrel Detector (BD), which is generated when the total multiplicity of hits is greater than four. The implementation of trigger logic is presented in Table 1. In our analysis of hadronic interactions, the CCT trigger was used with the condition of a single initial 124Xe nucleus registered by the BC1 beam counter.

| [2pt] BT | |

|---|---|

| [2pt] CCT |

The layout of the trigger detectors used for the event selection in the BM@N experiment is shown in Fig. 3.

However, a dedicated trigger for selecting EMD events was not available in the BM@N experiment. According to the RELDIS model used to simulate ultraperipheral 124Xe–130Xe collisions, in these EMD events one or two neutrons are emitted by a 124Xe beam nucleus without violent fragmentation of the projectile [9]. In addition to forward neutron(s), a single residual nucleus (either 122Xe or 123Xe) is produced in EMD without any other particles, and the BT trigger with a single initial 124Xe nucleus in the BC1 beam counter is used to count EMD events to ensure that a beam ion enters the target.

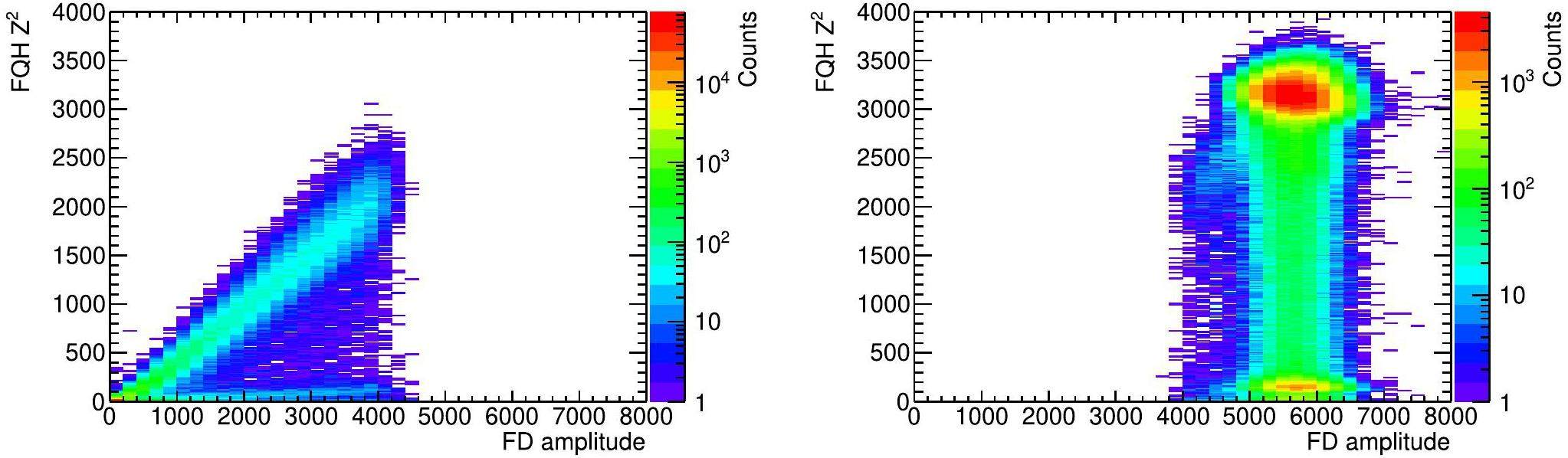

The correlations between the signals from the Forward Quartz Hodoscope (FQH) [17] and the FD after selecting hadronic fragmentation events by the CCT trigger with vertex reconstruction and after selecting EMD events are shown in the left and right panels of Fig. 4. The responses of both detectors are defined by the charges of fragments that hit them, and their responses correlate well with each other. It can also be seen that events with non-interacting 124Xe nuclei are effectively suppressed, in contrast to EMD events. The domain characterized by high amplitudes in FD and low Z2 in FQH corresponds to events with fragments interacting on their way from FD to FQH or escaping the acceptance of FQH. A residual nucleus produced in an EMD event is deflected by the magnetic field and hits FD and FQH, making it possible to measure the charge of this nucleus. A large number of EMD events characterized by the response of the BM@N detectors to residual 122,123Xe nuclei with

The analysis of the experimental data collected from the HGND prototype starts with the event selection procedure, which includes charged particle rejection, photon rejection, selecting events with two or more triggered cells, and amplitude and time-of-flight cuts. The VETO layer selection is necessary to distinguish between charged and neutral particles. If the deposited energy in any cell of the VETO layer is greater than half of the deposited energy produced by minimum ionizing particles (MIPs), such an event will be discarded.

Photon rejection was used to separate neutrons from photons. This procedure rejects an event if any cell in the layer adjacent to the VETO layer is triggered by a signal greater than 0.5 MIP. Our estimations show that more than 79% of photons and only 10% of neutrons at the entrance to the HGND prototype are rejected with this cut because of the significant difference between the radiation length and the nuclear interaction length in the first lead plate after the VETO detector.

Amplitude and time-of-flight selection, combined with the condition of more than one triggered cell in an event, were used to distinguish spectator neutrons from a low-energy background. For the selection of successive cells with amplitudes larger than 0.5, the MIP amplitude was used together with the time selection to eliminate background contribution. The time-of-flight cut was set individually for each active layer. This corresponded to the minimal neutron kinetic energy of approximately 1.5 GeV.

The ability of the HGND prototype to detect high-multiplicity neutron events is limited because of the small transverse dimensions (12 cm × 12 cm) of this detector. This limitation will be removed in the design of the full-scale HGND, with its much larger dimensions, by considering the spatial positions and time stamps of the signals obtained from a larger number of individual HGND cells.

Given the aforementioned inability of the HGND prototype to detect multiple neutrons from a nucleus-nucleus collision event, our analysis was limited to the detection of only one neutron per event. The kinetic energy of the neutron was measured using the time-of-flight method by selecting the cell triggered by the particle with the highest velocity in the event. The measured spectra for both types of interactions were divided by the number of incident ions obtained with the BT trigger together with the detection of a single initial 124Xe nucleus in the BC1 beam counter.

Reconstruction of neutron kinetic energy

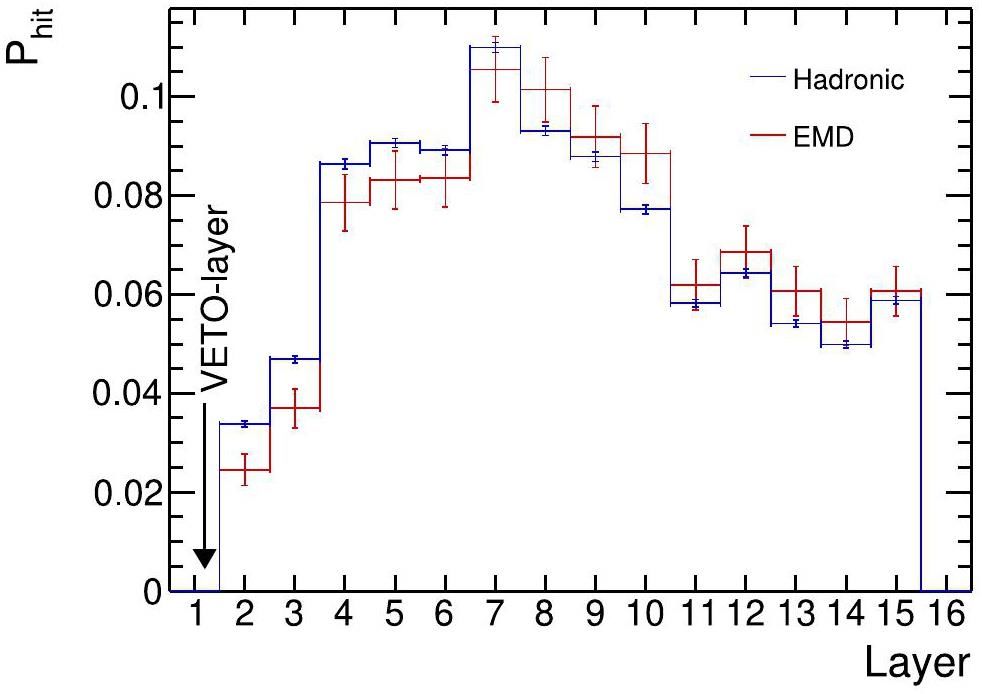

The measured probability distribution to trigger a given scintillator layer by particles with the highest velocity in the event is presented in Fig. 5 as a function of the layer number. As can be seen, neutrons emitted in both hadronic collisions and EMD interact mostly after the 7th layer. Photons that hit the HGND prototype were rejected by imposing the condition that if the first layer after the VETO layer was triggered, the event was discarded as associated with a photon. Owing to this selection, approximately 20% of the events of hadronic interactions and EMD were rejected. The uncertainty of the photon rejection procedure is expected to be one of the main sources of systematic uncertainties in measuring neutron yields. This was estimated from the change in the neutron yield obtained without photon rejection with respect to the standard reconstruction. Other contributions to the systematic uncertainty of the neutron yield and neutron flow measurements in the BM@N experiment are not detailed in this work. This is the subject of future research.

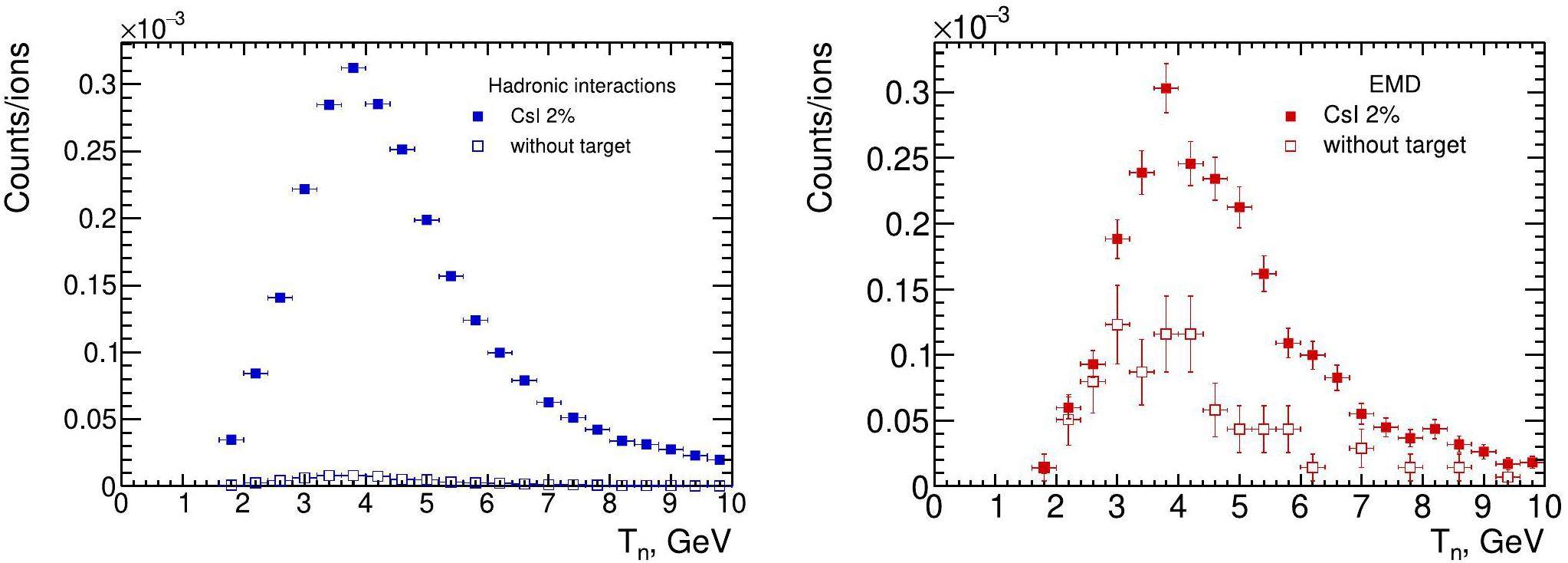

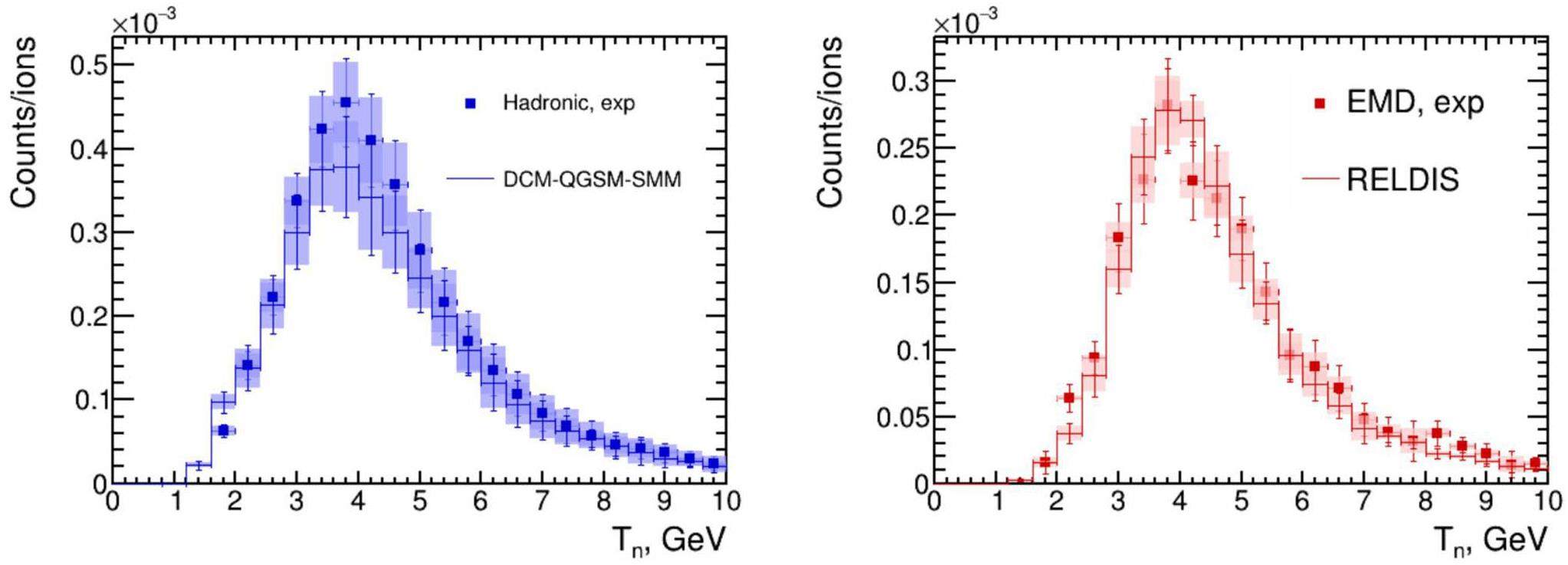

To estimate the background caused by the interaction of the beam particles with structural elements of the target station, the number of neutrons produced in a run with the CsI 2% target was compared with the number of neutrons measured in an empty target run when the target was removed and the 124Xe beam interacted only with air or materials supporting the target. The reconstructed neutron spectra measured with and without the 2 % CsI target are shown in Fig. 6 for the hadronic and EMD events. Here, the neutron spectra for both hadronic interactions (left) and EMD (right) were normalized to the number of incident ions measured by BT. The trigger efficiency is close to 100% for the most central events and slightly decreases for semi-central events in the centrality class of 0–60% selected by the CCT trigger. Therefore, the effect of trigger efficiency was not considered in this analysis.

The number of neutrons detected in the empty target run was approximately 3% for hadronic interactions and 38% for EMD, with respect to neutrons detected in the CsI target run. Because the procedure for selecting hadronic interactions of beam nuclei with the CsI target in the BM@N experiment is very efficient, the background contribution from the empty target is relatively small for hadronic interactions. By contrast, because a specific trigger for EMD events is not available, the contribution of background events is noticeably larger in EMD. The background contributions described above, mostly associated with neutrons produced in the structural elements of the target station, were subtracted from the measured neutron energy spectra for both the interaction types.

Comparison with Monte Carlo simulations

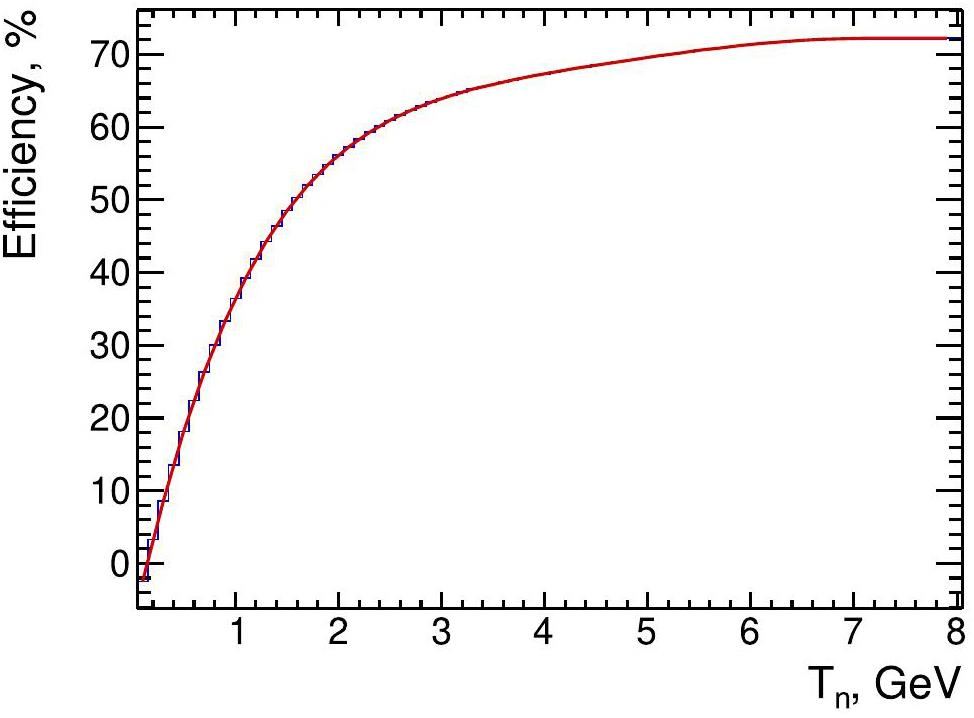

The selection procedure applied to the detected events and described in Sect. 3.1 was used also in modeling. The efficiency calculated using Geant4 [18] for the detection of a single neutron with a given energy in the HGND prototype is shown in Fig. 7. In this modeling, neutrons were transported directly to the front surface of the detector placed in vacuum and were not accompanied by any other particles. Owing to the more developed hadronic showers induced by more energetic neutrons, the detection efficiency is higher at higher energies. A polynomial fit to the modeled efficiency is shown in Fig. 7, was used to correct the number of reconstructed neutrons depending on their energy.

The hadronic interactions of 3.8A GeV 131Xe projectiles with the 133Cs target as an equivalent of the CsI target were generated using the DCM-QGSM-SMM [19] model. The total hadronic cross section corresponding to the event centrality of 0-60% was calculated with this model as 3.165 b.

The RELDIS model [9, 20] was used to simulate the electromagnetic dissociation of 3.8A GeV 124Xe projectiles in the UPC with 130Xe representing the average nucleus in the CsI target. In this model, the Lorentz-contracted Coulomb fields of the nuclei in their UPC are represented by equivalent photons, which predominantly excite giant dipole resonances (GDRs) in these nuclei by delivering the excitation energy to 124Xe, mostly below the proton emission threshold. The total EMD cross section of 124Xe–130Xe collisions was calculated as 1.89 b.

The detection of neutrons by the HGND prototype in its forward (0.7°) position was modeled using the BmnRoot software, taking into account the detailed geometry of the BM@N experiment. In these simulations, the time resolution of the scintillation cells was set to 270 ps. We considered hadronic collisions only with a centrality of 0–60%, as selected in the experiment by the CCT trigger, and applied the corresponding centrality selection to the simulated events.

In particular, events with an impact parameter of less than 9.54 fm were selected from event files generated with the DCM-QGSM-SMM model to represent 0–60% centrality. As demonstrated in Ref. [21], the results of centrality estimators based on the multiplicity of charged particles and signals from forward calorimeters (which are impacted by forward neutrons, among other particles and nuclear fragments) are consistent within their uncertainties. In particular, all methods associate the interval [0, bmax], where bmax ∼ 9±1 fm, with a centrality range of 0–60%. Therefore, the results in Refs. [21] obtained for 4A GeV Xe+CsI collisions justify the selection of b< 9.54 fm in the DCM-QGSM-SMM model.

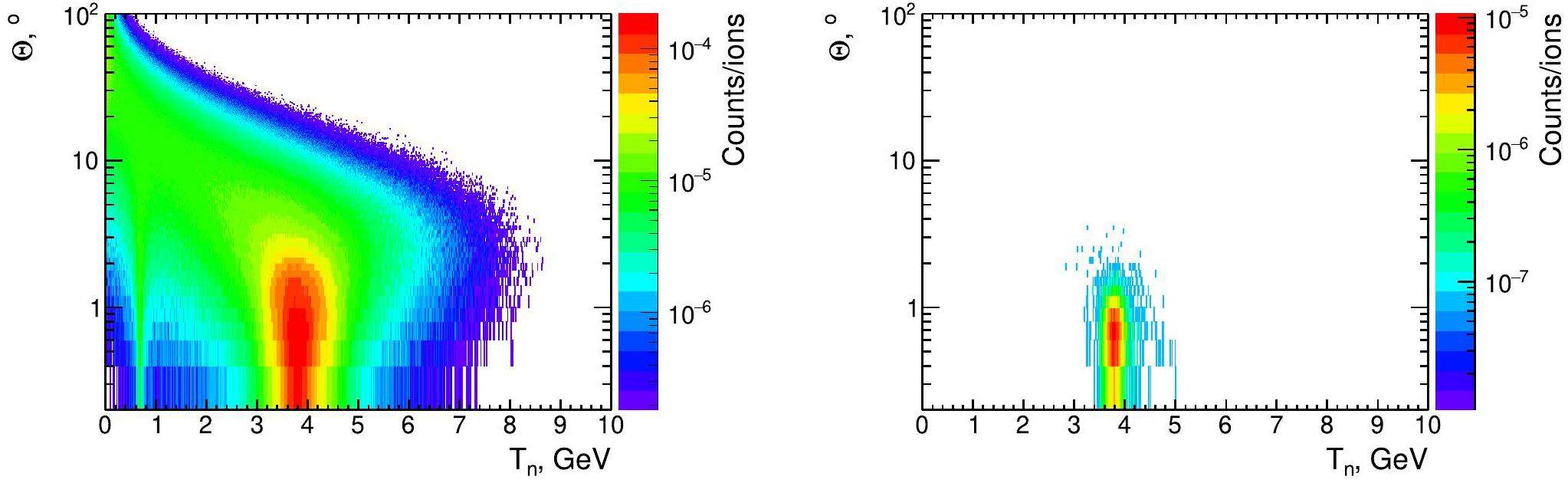

The correlations between the emission angle Θ and neutron kinetic energy Tn in the laboratory system obtained in simulations using the DCM-QGSM-SMM and RELDIS models are presented in Fig. 8. The spread of the kinetic energy Tn is essential for hadronic fragmentation events. For example, a small percentage of forward neutrons from the hadronic fragmentation of 124Xe have kinetic energies up to 5.5 GeV, which is much higher than the nominal beam kinetic energy of

As seen in Fig. 8, all neutrons in the simulated EMD events are characterized by a very narrow angular distribution, and the average neutron energy is equal to the beam energy of 3.8 GeV. The energy distribution of EMD neutrons is also very narrow; the calculated energies of all EMD neutrons are between 3.4 and 4.2 GeV, within ± 10% of the average [9]. Because the neutrons emitted by electromagnetically excited 124Xe nuclei mostly result from decays in the low-lying giant dipole resonance in 124Xe, their kinetic energies in the rest frame of a beam nucleus are less than a few MeV.

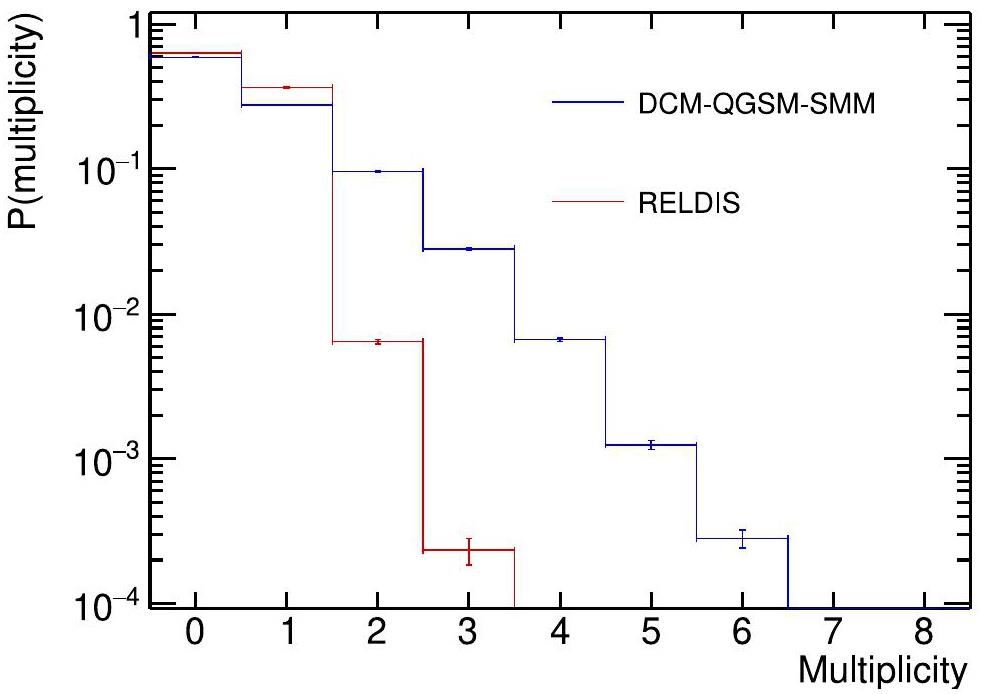

As predicted by RELDIS [9], the average multiplicity of neutrons produced in EMD of 124Xe is 1.05. According to our model, because of the limited angular coverage of the HGND prototype, ~66% of these neutrons do not hit the detector, as shown in Fig. 9. Considering events with only neutron hits, the average number of neutrons that hit the front surface of the HGND prototype was 1.02. Therefore, the energy reconstruction of EMD neutrons is free from the above-mentioned complications that are typical of multineutron events.

In contrast, following the DCM-QGSM-SMM model, the average multiplicity of spectator neutrons produced in hadronic collisions of centrality 0-60% amounts to 16.01 per projectile fragmentation. Owing to the much wider angular dispersion of fragmentation neutrons, approximately 97% of them are not intercepted by the detector. Again, in events when neutrons hit the front surface of the detector, their average number was 1.44.

To estimate the acceptance and detection efficiency of forward neutrons by the HGND prototype, the same event selection procedures applied to the experimental data in Sect. 3 were used in the simulations. The acceptance acc and efficiency ε of the HGND prototype were calculated based on the modeling described above using Eqs. (1) and (2).

The calculated values of the acceptance and efficiency of the detection of neutrons from the hadronic interaction and EMD are listed in Table 2.

| Model | acc (%) | ε (%) | acc × ε (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DCM-QGSM-SMM | 3.37 ± 0.02 | 39.69 ± 0.20 | 1.34 ± 0.01 |

| RELDIS | 36.77 ± 0.27 | 55.77 ± 0.41 | 20.51 ± 0.15 |

Although the HGND prototype is ~50% more efficient in detecting more forward-focused EMD neutrons that hit its forward surface with respect to neutrons from hadronic fragmentation, there is a drastic difference in the geometrical acceptance of neutrons from these two processes (3.37% vs. 36.77%). Considering the resulting

It should be noted that the detection efficiency (55.8%) calculated for EMD neutrons with

The difference in the efficiency values calculated for EMD and hadronic interactions is due to the ~1.5 times different average multiplicity of neutrons hitting the detector. Because it is impossible to reconstruct more than one neutron in an event with the current detector configuration, the probability of detecting all neutrons in the event is drastically reduced.

The data were normalized to the number of incident ions for both the hadronic interactions and EMD, see Sect. 3. In the simulations, each generated event corresponds to a single interaction. For comparison with the measured neutron spectra, the simulated spectra were normalized to the number of incident ions on the target and calculated using Eq. (3) for both interactions.

Finally, the neutron energy distributions corrected for the efficiency of the HGND prototype were obtained from the simulations and measurements. The spectra are shown in Fig. 10 separately for neutrons from nuclear fragmentation and EMD of 124Xe.

As can be seen, the measured distributions of the kinetic energy of neutrons agree well with the calculated distributions for both kinds of interactions of 124Xe.

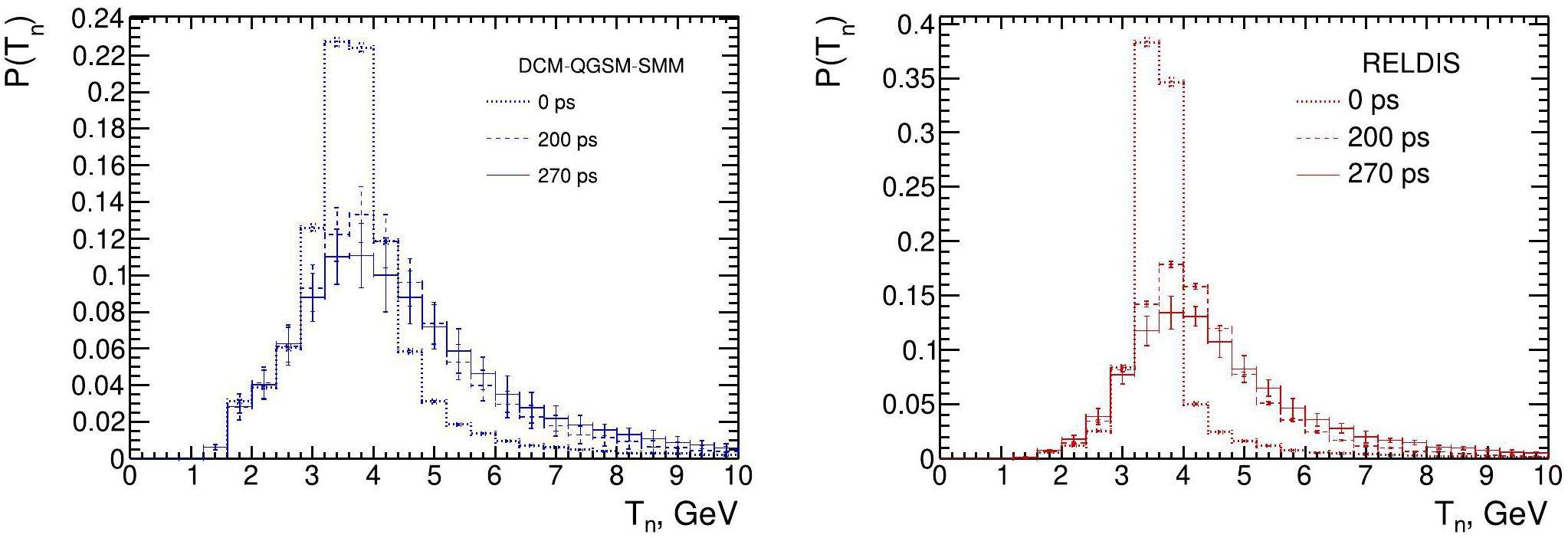

Although the extension of neutron kinetic energy spectra up to 5.5 GeV in hadronic events is the effect of relativistic kinematics, a further extension of the reconstructed energy spectra up to 10 GeV is caused by the limited resolution of the time-of-flight measurements with the HGND prototype. The neutron kinetic energy spectra reconstructed by the time-of-flight method using the fastest trigger of the scintillation cell are shown in Figs. 6 and 10, and they were obtained by assuming a time resolution of 270 ps. To demonstrate the sensitivity of the reconstruction results to the choice of time resolution, the reconstructed spectra were also obtained with time resolution parameters of 0 and 200 ps in addition to the nominal 270 ps, and they are compared in Fig. 11. In this figure, the impact of time resolution on the shape of the reconstructed spectra is clearly visible. In the ideal case of 0 ps resolution, the initial spectra from event generators were reproduced quite well, but the artifact of the extension of the reconstructed spectra up to 10 GeV was also seen. It should be noted that in the present work the extreme case of detecting forward most energetic neutrons has been considered and used for detector calibration. In future studies of neutron flow in the mid-rapidity region, a full-scale HGND will be used to detect neutrons with Tn < 3 GeV. As seen in Fig. 11, the impact of time resolution on the reconstructed spectra is essentially alleviated at Tn < 3 GeV.

Conclusion

The design of the HGND prototype, which was built to validate the concept of the full-scale HGND developed to measure neutron yields in the BM@N experiment at the NICA accelerator complex, was presented. The highly granular multilayer structure of the HGND prototype is represented by the interleaved scintillator and absorber layers. The first scintillator layer was used as a VETO to reject charged particles. As shown by our measurements, forward neutrons emitted in hadronic fragmentation and EMD of 3.8A GeV 124Xe nuclei on the CsI target in the BM@N experiment can be identified with the HGND prototype by imposing the photon rejection procedure, proper amplitude, and time-of-flight cuts.

The acceptance and detection efficiency of forward neutrons with the HGND prototype were calculated for spectator neutrons from hadronic fragmentation and for neutrons from EMD of 124Xe by modeling the transport of neutrons and all other secondary particles in the BM@N setup. The hadronic fragmentation and EMD events were generated using the DCM-QGSM-SMM and RELDIS models, respectively. The simulated kinetic energy distributions of forward neutrons from hadronic fragmentation and EMD of 3.8A GeV 124Xe agree well with the measured distributions.

It was shown that the electromagnetic dissociation of relativistic beam nuclei can be considered as a source of well-collimated high-energy neutrons with a multiplicity of approximately one per EMD event. We plan to use such neutrons as well as neutrons from the fragmentation of beam nuclei to calibrate the recently developed full-scale HGND [24].

The BM@N spectrometer at the NICA accelerator complex

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A, 1065:Baryonic matter@nuclotron: upgrade and physics program overview

. Phys. Atom. Nuclei, 86, 1346-1353 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1063778824010368Isospin asymmetry in nuclei and neutron stars

. Phys. Rep., 411, 325-375 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2005.02.004Effects of incompressibility K0 in heavy-ion collisions at intermediate energies

. Phys. Rev. C 109,On the Scaling Properties of the Directed Flow of Protons in Au + Au and Ag + Ag Collisions at the Beam Energies of 1.23 and 1.58A GeV

. Phys. Part. Nucl. 55, 832-835 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1063779624700308Neutrons from projectile fragmentation at 600 MeV/nucleon

. Phys. Rev. C 108,NeuLAND: The high-resolution neutron time-of-flight spectrometer for R3B at FAIR

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A 1014,Development of a high granular TOF neutron detector for the BM@N experiment

. Instrum. Exp. Tech., 67, 447-456 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1134/S0020441224700702Electromagnetic dissociation of nuclei: From LHC to NICA

. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 33,EQR15 Series SiPMs

. http://www.ndl-sipm.net/PDF/Datasheet-EQR15.pdf. AccessedMeasurement of time resolution of scintillation detectors with EQR-15 silicon photodetectors for the time-of-flight neutron detector of the BM@N Experiment

. Instrum. Exp. Tech. 67, 443-446 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1134/S0020441224700696Analytical description of the time-over-threshold method based on time properties of plastic scintillators equipped with silicon photomultipliers

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A, 1068:Online monitoring of the highly granular neutron time-of-flight detector prototype for the BM@N experiment

. Phys. Part. Nucl. Lett. 21(4), 664-667 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1547477124700985MPPC S13360-6050PE

. https://www.hamamatsu.com/jp/en/product/optical-sensors/mppc/mppc_mppc-array/S13360-6050PE.html. AccessedTQDC AFI Electronics, VME TQDC-16

. https://afi.jinr.ru/TQDC-16. AccessedTime resolution and light yield of scintillation detector samples for the time-of-flight neutron detector of the BM@N experiment

. Instrum. Exp. Tech. 66, 553-557 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1134/S0020441223030065Forward detectors of the BM@N facility and response study at a carbon ion beam in the SRC experiment

. Instrum. Exp. Tech. 66, 218-227 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1134/S0020441223010232Recent developments in Geant4

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res., Sect. A, 835, 186-225 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1134/S0020441223030065Monte-Carlo generator of heavy ion collisions DCM-SMM

. Phys. Part. Nucl. Lett. 17, 303-324 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1547477120030024Electromagnetic excitation and fragmentation of ultrarelativistic nuclei

. Phys. Part. Nucl. 42, 215 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1063779611020067Possibilities of using different estimators for centrality determination with the BM@N experiment

. Phys. Atom. Nuclei 86, 1502-1507 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1134/S1063778824010460Statistical models of fragmentation processes

. Phys. Lett. B 53, 306-308 (1974). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(74)90388-8Sequential decay distortion of Goldhaber model widths for spectator fragments

. Phys. Rev. C 65,The highly-granular time-of-flight neutron detector for the BM@N experiment

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A 1072:The authors declare that they have no competing interests.