Introduction

Neodymium isotopes play a crucial role in nuclear processes. They are important fission products that are widely used in activation analysis and reactor physics research [1-3]. Their neutron capture and photonuclear properties affect key areas of nuclear science, including neutron economy [4], fuel cycle management [5], radiation shielding [6], and nuclear astrophysics [7]. Neodymium has seven naturally stable isotopes, namely, 142,143,144,145,146,148,150Nd, with abundances of 27.15%, 12.17%, 23.798%, 23.798%, 8.293%, 17.189%, and 5.638%, respectively [3]. Accurate knowledge of their photonuclear cross-sections is essential for enhancing fission reactor modeling, activation analysis, and broader applications, such as reactor design and nucleosynthesis studies.

Early studies of photonuclear reactions used broad-spectrum bremsstrahlung light sources from electron linear accelerators and quasi-monochromatic positron annihilation sources based on time-of-flight methods [8]. Between 1962 and 1987, the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory [9] and the Saclay Laboratory [10] conducted numerous experiments using quasi-monochromatic light sources, yielding precise photoneutron cross-section data. However, Berman’s review highlighted discrepancies between the (γ,n) and (γ,2n) cross sections from the two laboratories, emphasizing the need for further investigation.

New photonuclear reaction data have been obtained through experiments at facilities such as NewSUBARU and Oslo [11]. Advances in light source and neutron detection technologies have led to the development of high-quality experimental facilities. Recently, the Shanghai Advanced Research Institute completed an SLEGS facility using inverse Compton backscattering [12], which has attracted significant attention. The China Nuclear Data Center (CNDC) collaborates with the SLEGS facility to improve measurement techniques and theoretical evaluations with the goal of establishing a comprehensive photonuclear reaction database.

To enhance the quality of photonuclear reaction cross-section data and resolve inconsistencies, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has organized two Coordinated Research Projects (CRPs) on photonuclear reactions. A recent CRP, conducted from 2016 to 2020, updated the IAEA’s photonuclear data and established a reference database for photon strength functions (PSF) [13-15]. The CNDC actively participated in both the CRPs, making significant contributions through experimental evaluations and theoretical calculations.

In theoretical approaches, two types of models are used to predict the strength function: phenomenological models and microscopic models [16-21]. The most commonly used phenomenological models include the Standard Lorentzian (SLO) model [22, 23], Enhanced Generalized Lorentzian (EGLO) model [24, 25], and Generalized Fermi-Liquid (GFL) model [26]. Microscopic models encompass the Finite Fermi Gas theory [27, 28], semi-classical thermodynamic approach [29], non-relativistic Quasiparticle Random Phase Approximation (QRPA) based on the BCS ground state [30], and relativistic Quasi-Particle Random Phase Approximation (RQRPA) based on the covariant density functional theory [31-33]. Phenomenological methods usually rely heavily on large amounts of experimental data; however, there are conflicts between the data measured by the Saclay Laboratory and the Livermore National Laboratory. Therefore, microscopic methods are required for this purpose.

QRPA has been the most popular microscopic method.. The QRPA and RQRPA methods have been successful for spherical nuclei; however, for deformed nuclei, the QRPA matrix becomes large, requiring significant computational and storage resources [34]. To address this, the finite-amplitude method (FAM) was introduced, which avoids the construction and diagonalization of the full QRPA matrix. Instead, FAM iteratively solves the linear response problem by calculating the fields excited by the one-body transition operators [35-37]. In 2020, A. Bjelcic and T. Niksic developed a QFAM model based on relativistic EDFs (DIRQFAM program) to compute the multipole response of even-even deformed nuclei [38], and in 2023, DIRQFAM2.0 was released with updates including meson exchange interactions and a new solver method [39].

The aim of this work is to better describe the experimental photon absorption cross-section using the microscopic method, as the photon absorption cross-section calculated by QFAM still shows a significant discrepancy with the experimental results. In this study, we calculated the photon-absorption cross-sections of even-even Nd isotopes using DIRQFAM2.0 and compare the results with experimental data. Section 2 outlines the theoretical framework of relativistics and introduces an approximation method for optimizing the system to align it with the experimental data. In Sect. 3, we discuss our results in detail. Finally, Section 4 presents the conclusions and future prospects of this study.

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical photoabsorption cross section σabs(ϵγ) as a function of gamma ray energy ϵγ is taken as the sum of the terms

The GDR component σGDR(ϵγ) of the total photoabsorption cross section is equal to that of the electric dipole gamma rays

The RQRPA equation can be solved by directly diagonalizing the A and B matrices (3) for the spherical nuclei. However, for deformed systems, the dimensionality of these matrices increases rapidly, and such calculations were only possible approximately a decade ago [45, 46]. To overcome the challenges of implementing matrix-based RPA for deformed heavy nuclei, FAM was introduced as an efficient alternative for calculating the multipole response functions. FAM has been successfully applied in numerous studies, both in coordinate space and on the harmonic oscillator basis [38, 39, 47, 48].

Relativistic QFAM

The ground-state properties of the nuclei were determined within the framework of the Relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov (RHB) method. The RHB Hamiltonian incorporates the mean-field term

The Giant Dipole Resonance (GDR) strength is given by the relativistic QFAM equation, which describes the nuclear response to an external one-body field

Tiny Smearing Approximation method

While the relativistic QFAM approach offers a highly efficient solution to the standard RQRPA problem, it does not provide direct access to the RQRPA eigenfrequencies Ωi However, the method proposed in Ref. [51], which is based on contour integration in a complex plane, enables the extraction of RQRPA transition matrix elements and eigenfrequencies from relativistic QFAM calculations.

In this section, the TSA method is introduced, which provides an efficient approach for connecting the relativistic QFAM strength function with the RQRPA transition matrix elements. As is well known, the response function is

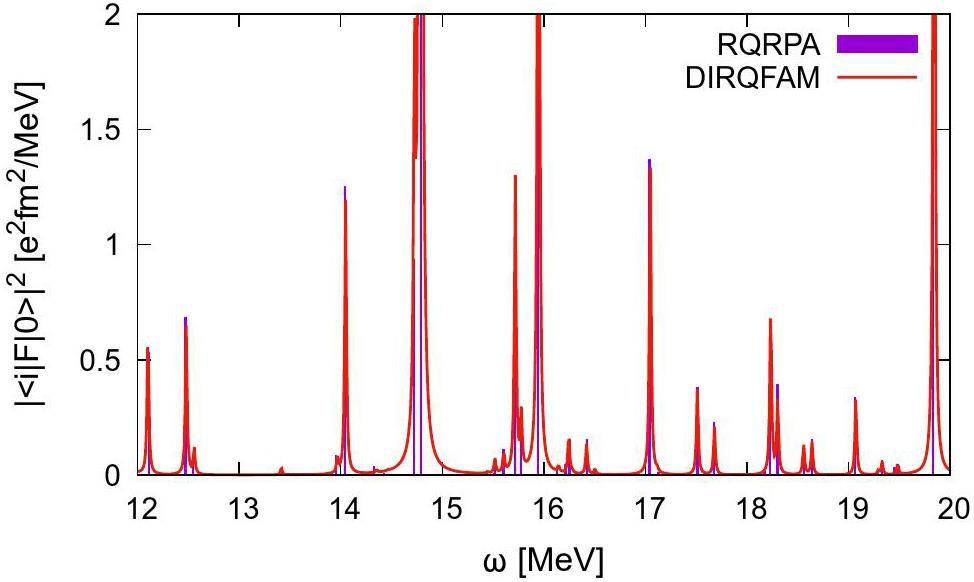

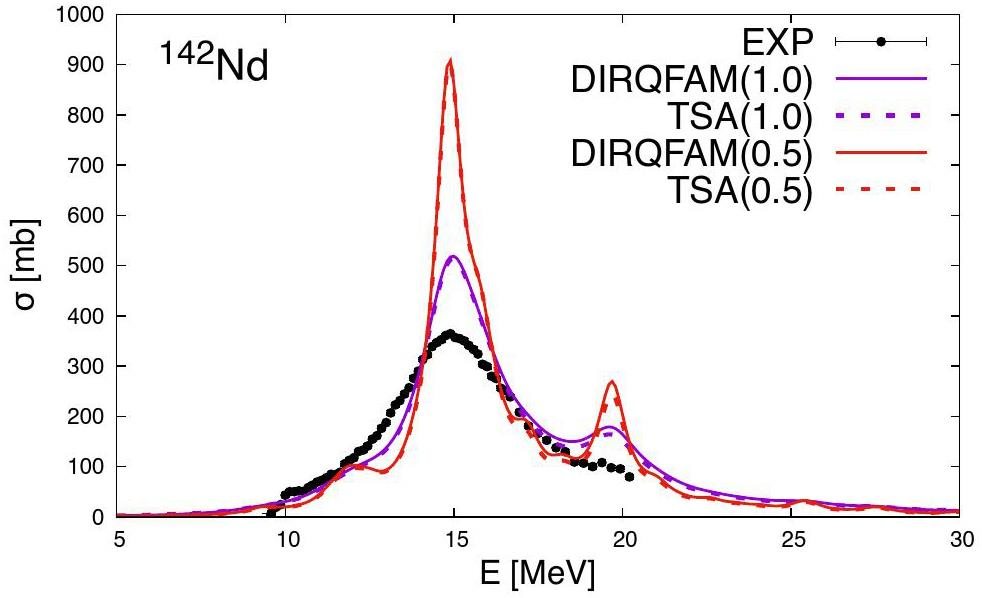

In Fig. 1, we present the isovector Giant Dipole Resonance (GDR) response of 142Nd, calculated using DD-PC1 parameterization with a separable pairing interaction and Nshells=20 oscillator shells. The purple columns represent the

In practice, once we know the transition matrix elements

Calculations and discussion

The photon absorption cross-sections of Nd isotopes were first measured in 1971 by Carlos et al., [52]. In this study, we employed the relativistic QFAM method to calculate the photon-absorption cross sections for even-even Nd isotopes.

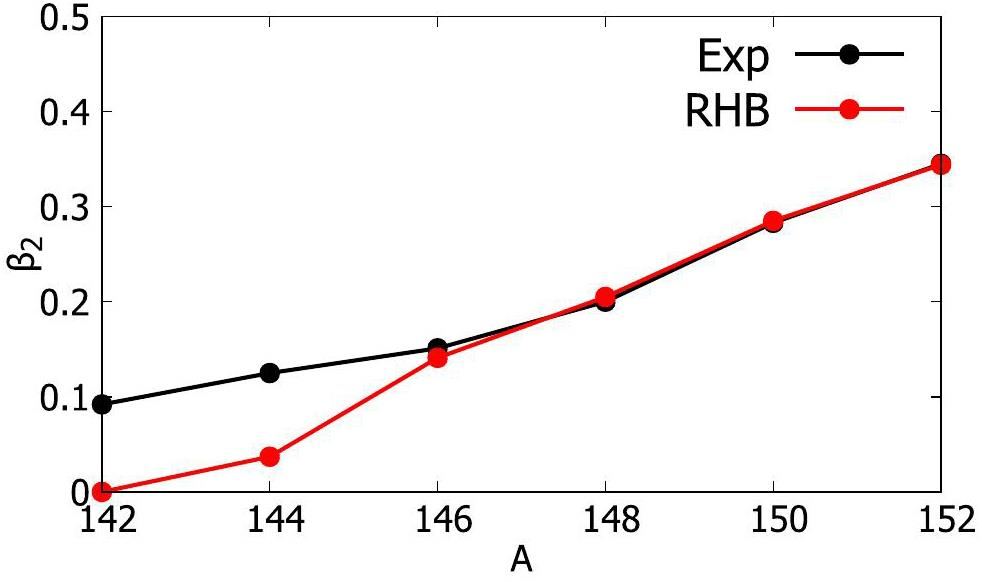

First, we solved the RHB equation using the DD-PC1 relativistic density functional combined with a separable pairing interaction to calculate the ground-state properties of even-even Nd isotopes. In Fig. 3, we compare the quadrupole deformations between the experimental data [53] and those obtained from the RHB calculations for 142Nd to 152Nd. Experimentally, the deformation of Nd isotopes increases with neutron number. While the RHB calculations accurately reproduced the deformation for isotopes beyond 146Nd, they predicted 142Nd and 144Nd to be closer to spherical configurations, deviating from the experimental observations.

In our previous work [16], we constructed microscopic GDR parameters using relativistic quasiparticle random phase approximation (RQRPA) for spherical nuclei. We now extend this approach by constructing microscopic GDR parameters based on the Dirac Quasiparticle Finite Amplitude Method (relativistic QFAM) combined with the TSA method.

In this study, we introduce an energy-dependent width parameter, defined as

| Parameters | χ2 | δΓ ( |

G | δω (MeV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relativistic QFAM | 81.5915 | 1.0000(C) | - | - |

| TSA | 8.4250 | 0.4147(ED) | 0.9749 | 0.3276 |

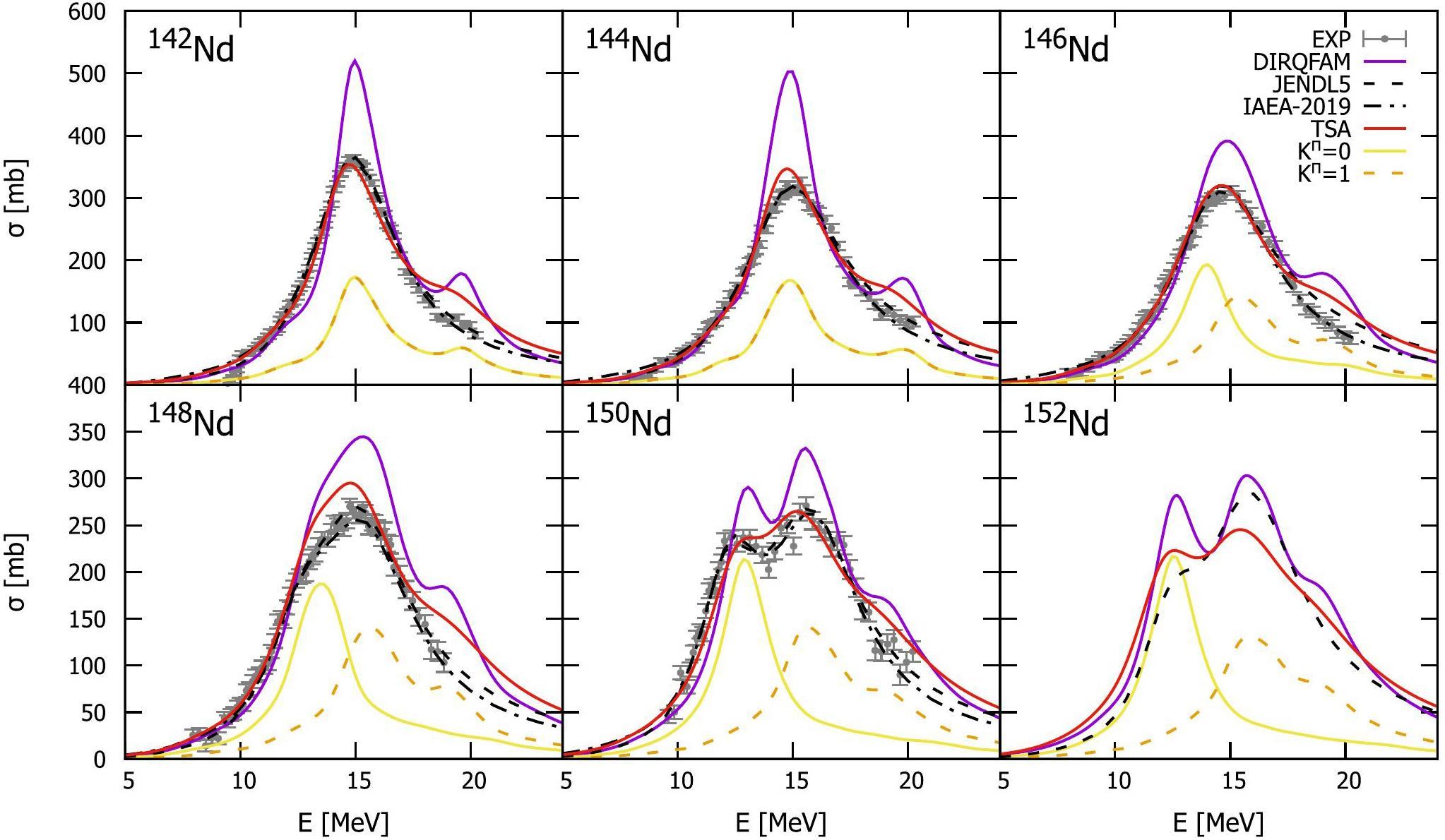

In Fig. 4, we display the Kπ=0-(yellow solid line) and Kπ=1-(orange dashed line) components of the photon-absorption cross section obtained from the relativistic QFAM calculations with smearing γ=1.0, the total photon-absorption cross section obtained from the relativistic QFAM calculations (purple solid line), the results using the TSA method (red solid line), compared with the experimental data [52] and evaluated data of IAEA-2019 [55] or JENDL-5 [56] (black dotted dashed line). Only the JENDL-5 evaluation database predicted the photon absorption cross section of 152Nd.

As shown in Fig. 4, the centroid energy calculated using relativistic QFAM aligns well with the experimental data. For 142Nd and 144Nd, only a single peak was observed in the photon absorption cross section, as the deformation of these nuclei was minimal. Consequently, the centroid energies of the Kπ=0- and Kπ=1- components were nearly identical. For 146Nd to 152Nd, the Kπ=0- and Kπ=1- components are separated because these nuclei are well deformed. For 150Nd and 152Nd, there are two distinct peaks in the photon absorption cross-section owing to splitting of the GDR.

By employing Eqs. (13) and (14), the parameters δΓ, G, and δω were adjusted by fitting to the experimental data of Carlos et al. [52] for even-even Nd isotopes using the TSA method. This optimization significantly improves the agreement with the experimental data compared to relativistic QFAM calculations. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the TSA method in accurately reproducing the photon absorption cross sections of Nd isotopes.

Finally, we predicted for 152Nd and compared it with the evaluation data from the JENDL-5 library [56]. Our calculated photon absorption cross sections are significantly smaller than the JENDL-5 data, but are more consistent with the cross-sections of 150Nd.

Conclusion

In this study, we demonstrated that the GDR strength functions calculated by relativistic QFAM with any appropriate smearing parameter γ can be efficiently obtained using the TSA method. This approach significantly reduces the computational cost of calculating photon-absorption cross-sections with relativistic QFAM and allows for the incorporation of energy-dependent Lorentzian broadening.

We extend this approach by constructing microscopic GDR parameters based on relativistic QFAM combined with the TSA method, which can describe the photon absorption cross-section of even-even Nd isotopes using only three parameters.

In the future, we will broaden our investigation of photon absorption cross-sections to include a wider range of atomic nuclei using this TSA method based on relativistic QFAM. Additionally, we will explore the impact of different interactions, such as the density-dependent meson exchange (DD-ME2) parameter set and the pairing strength on the photon absorption cross-section.

Systematics of nd cumulative fission yields for neutron-induced fission of 235u, 238u, 238pu, 239pu, 240pu and 241pu

. The European Physical Journal Plus 133, 99 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjp/i2018-11926-yStable neodymium isotopic composition of nuclear debris samples

. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry 332, 2715-2723 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-023-08935-zTheoretical calculation for photonuclear reaction of 142-146,148,150Nd

. Atomic Energy Science and Technology 56, 896-904 (2022)Rare earth permanent magnets and their place in the future economy

. Engineering 6, 115-118 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2019.12.007Recovering the new twin: Analysis of secondary neodymium sources and recycling potentials in europe

. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 142, 143-152 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2018.11.024Exploring elastic mechanics and radiation shielding efficacy in neodymium(iii)-enhanced zinc tellurite glasses: A theoretical and applied physics perspective

. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Physics 17 (2023). https://doi.org/10.57647/J.JTAP.2023.1704.44Photoneutron cross sections for neodymium isotopes: Toward a unified understanding of (γ,n) and (n,γ) reactions in the rare earth region

. Phys. Rev. C 91,Handbook on Photonuclear Data for Applications Cross-sections and Spectra Final Report of a Co-ordinated Research Project 1996-1999, no.IAEA-TECDOC-1178

,Measurements of the giant dipole resonance with monoenergetic photons

. Reviews of Modern Physics 47, 713 (1975). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.47.713The giant dipole resonance in the transition region for the neodymium isotopes

. Nuclear Physics A 172, 437-448 (1971). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(71)90725-1The γ-ray beam-line at newsubaru

. Nuclear Physics News 25, 25-29 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1080/10619127.2015.1067539Development and prospect of shanghai laser compton scattering gamma source

. Nuclear Physics Review 37, 53-63 (2020). https://doi.org/10.11804/NuclPhysRev.37.2019043Updating the photonuclear data library and generating a reference database for photon strength functions

, in:Updating photonuclear data library and generating a reference database for photon strength functions

, in:Iaea photonuclear data library 2019

. Nuclear Data Sheets 163, 109-162 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nds.2019.12.002Giant dipole resonance parameters from photoabsorption cross-sections

. Chinese Physics C 43,Progress in ab initio in-medium similarity renormalization group and coupled-channel method with coupling to the continuum

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 35, 215 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01585-0Structure and 2p decay mechanism of 18mg

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 35, 107 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01479-1Moments of inertia of triaxial nuclei in covariant density functional theory

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 35, 183 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01552-9Enhancing reliability in photonuclear cross-section fitting with bayesian neural networks

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 36, 52 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01611-1New quantification of symmetry energy from neutron skin thicknesses of 48Ca and 208Pb

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 35, 182 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01551-wElectric dipole ground-state transition width strength function and 7-mev photon interactions

. Physical Review 126, 671 (1962). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.126.671Test of gamma-ray strength functions in nuclear reaction model calculations

. Physical Review C 41, 1941 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.41.1941Radiative strength in the compound nucleus gd-157

. Physical review C 47, 312 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.47.312A dipole-quadrupole interaction term in e1 photon transitions

. Physics Letters B 487, 155-164 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0370-2693(00)00792-9Testing and improvements of gamma-ray strength functions for nuclear model calcula-tions

. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2, 811 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1080/00223131.2002.10875222The time-dependent relativistic mean-field theory and the random phase approximation

. Nuclear Physics A 694, 249-268 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(01)00986-1Quasiparticle random phase approximation based on the relativistic hartree-bogoliubov model

. Phys. Rev. C 67,Self-consistent relativistic quasiparticle random-phase approximation and its applications to charge-exchange excitations

. Phys. Rev. C 95,Low-energy collective modes of deformed superfluid nuclei within the finite-amplitude method

. Physical Review C 87,Finite amplitude method for the solution of the random-phase approximation

. Physical Review C 76,Self-consistent calculation of nuclear photoabsorption cross sections: Finite amplitude method with skyrme functionals in the three-dimensional real space

. Physical Review C 80,Feasibility of the finite-amplitude method in covariant density functional theory

. Phys. Rev. C 87,Implementation of the quasiparticle finite amplitude method within the relativistic self-consistent mean-field framework: The program dirqfam

. Computer physics communications 253,Implementation of the quasiparticle finite amplitude method within the relativistic self-consistent mean-field framework (ii): The program dirqfam v2.0.0

. Computer Physics Communications 287,Pauli-blocking in the quasideuteron model of photoabsorption

. Phys. Rev. C 44, 814-823 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.44.814A novel way to study the nuclear collective excitations

. Nuclear Science and Techniques 34, 189 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01343-8Collectivity of the low-lying dipole strength in relativistic random phase approximation

. Nuclear Physics A 692, 496-517 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(01)00653-4New data on photoabsorption reaction cross sections

. Izvestiya Akademii Nauk. Rossijskaya Akademiya Nauk. Seriya Fizicheskaya 67, 656-663 (2003)Separable pairing force for relativistic quasiparticle random-phase approximation

. Physical Review C 79,Relativistic random-phase approximation in axial symmetry

. Phys. Rev. C 77,Dipole responses in nd and sm isotopes with shape transitions

. Physical Review C 83,Finite amplitude method for the solution of the random-phase approximation

. Phys. Rev. C 76,Finite amplitude method for the quasiparticle random-phase approximation

. Phys. Rev. C 84,Relativistic nuclear energy density functionals: Adjusting parameters to binding energies

. Phys. Rev. C 78,A finite range pairing force for density functional theory in superfluid nuclei

. Physics Letters B 676, 44-50 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2009.04.067Low-energy collective modes of deformed superfluid nuclei within the finite-amplitude method

. Phys. Rev. C 87,The giant dipole resonance in the transition region for the neodymium isotopes

. Nuclear Physics A 172, 437-448 (1971). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(71)90725-1Tables of e2 transition probabilities from the first 2+ states in even–even nuclei

. Atomic Data and Nuclear Data Tables 107, 1-139 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adt.2015.10.001Minuit-a system for function minimization and analysis of the parameter errors and correlations

. Computer Physics Communications 10, 343 (1975)Iaea photonuclear data library 2019

. Nuclear data sheets 163, 109-162 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nds.2019.12.002Jendl photo nuclear data file 2016

. Journal of Nuclear Science and Technology 60, 911-922 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1080/00223131.2022.2161657The authors declare that they have no competing interests.