General overview

Scientific objectives

The high-brightness frontier is one of the three major frontiers in contemporary international particle physics research and holds an indispensable position. Current high-brightness, cutting-edge experimental facilities collectively address key scientific problems and are both competitive and complementary. Operational and on-construction facilities include LHC/LHCb at CERN, SuperKEKB/Belle II at KEK, BEPCII/BESIII at IHEP, FAIR/PANDA at GSI, and CEBAF/GlueX at JLab.

LHCb and Belle II primarily focus on B physics, producing large samples of hadrons containing bottom quarks, while also yielding significant numbers of charm hadrons and tau leptons. PANDA and GlueX—based on proton-antiproton annihilation using an antiproton beam on a fixed target and high-energy photoproduction using polarized photons on a proton target, respectively—also encompass the tau-charm energy region. The BESIII experiment has concentrated on charm hadron and tau lepton physics; however, the current BEPCII accelerator cannot be upgraded to meet the demands of particle physics research in the next 20–30 years. Over the past decade, Chinese scientists have actively developed a new-generation tau-charm facility—known as the Super Tau-Charm Facility (STCF)—and are striving to launch it as a major national science infrastructure project during the period of the 15th Five-Year Plan. The goal of this facility is to sustain China’s global leadership in tau-charm physics established over the past three decades. In addition to China, Russia is also pursuing a similar initiative, known as the SCTF project.

The STCF aims to collect a substantial and unique dataset in the tau-charm energy region, with an expected integrated luminosity of approximately 1 ab-1 per year. The primary physics goals include:

Studies of CP Violation and New Sources of CPV

Charge-Parity (CP) violation is a key component in explaining the matter–antimatter asymmetry in the universe. STCF will produce billions of quantum-entangled pairs of neutral D mesons, tau leptons, and hyperons, offering a unique environment for precision CPV studies. In particular, hyperon CP violation searches at STCF are expected to reach world-leading sensitivity (better than 10-4), which is sufficient for testing Standard Model (SM) predictions.

Hadron Spectroscopy and Exotic States

Just as spectroscopy is central to atomic and molecular physics, hadron spectroscopy plays a crucial role in understanding quantum chromodynamics (QCD) confinement. STCF will yield trillions of (charmonium-like) quark-antiquark states, enabling precise studies of the light hadron spectrum, charmonium-like structures, and the systematics of exotic hadrons.

Nucleon Structure and Formation

Probing the internal structure of nucleons is essential for uncovering the properties of matter and QCD confinement. STCF will perform threshold scans of baryonic final states to measure nucleon electromagnetic form factors, baryon decay constants, and strong phases, with at least an order-of-magnitude improvement over existing measurements.

Precision Measurements of Fundamental Parameters and Searches for New Physics

STCF will significantly improve the precision of fundamental quantities such as the tau lepton mass, strong phases in neutral D meson decays, and the magnetic dipole moments of baryons and leptons. The sensitivity to potential new physics will be enhanced by up to two orders of magnitude compared to current limits.

Accelerator design objectives

The STCF accelerator complex is designed to fulfill the above physics goals through high-luminosity operation in the center-of-mass energy range of 2.0–7.0 GeV. The baseline accelerator design targets include:

· Beam energy range for both electrons and positrons: Tunable from 1.0 to 3.5 GeV per beam (2.0 to 7.0 GeV in c.m. energy)

· Luminosity: ≥ 5 × 1034cm-2s-1 at 2.0 GeV beam energy

· Operational mode: Top-up (constant current) injection mode

· Future upgrade potential: Design provisions for future luminosity enhancement and other possibilities such as polarized beam and monochrmonization

Accelerator conceptual scheme

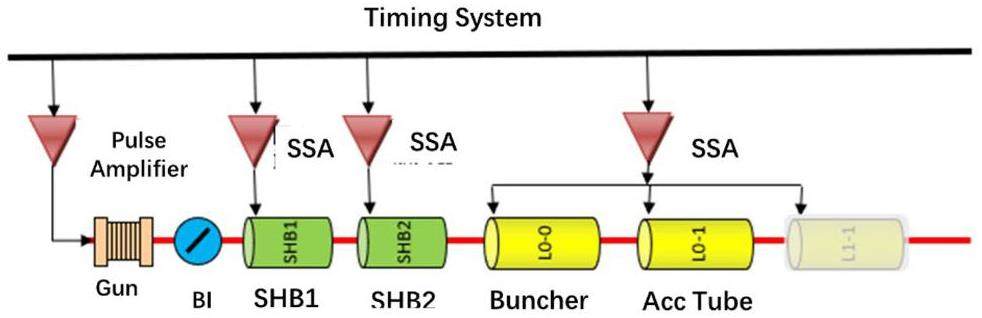

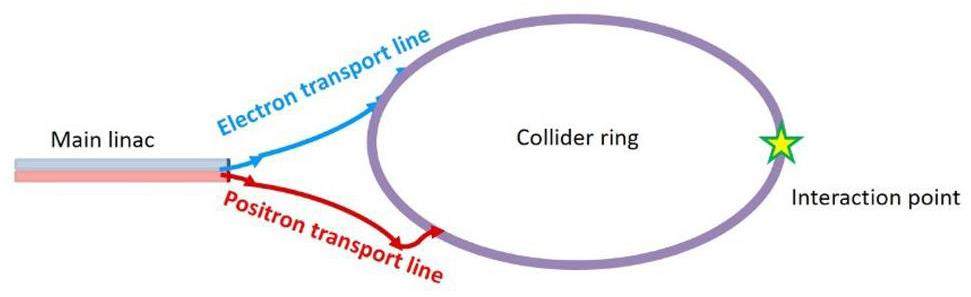

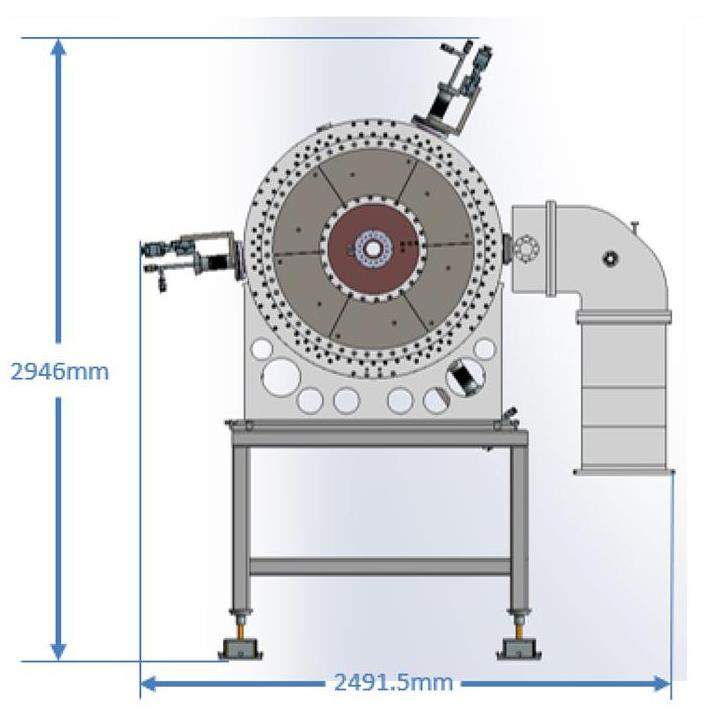

The core design objective of a new-generation electron–positron collider is to largely increase luminosity. Compared to the currently operating BEPCII, STCF should enhance luminosity by approximately two orders of magnitude, which requires both new design concepts and advanced technologies. Since around 2010, the international community has converged on a set of key features for the so-called third-generation e+e- colliders: a large crossing angle, a crab-waist collision scheme, an extremely small vertical beta function (

To meet the physics requirements of a center-of-mass energy ranging from 2 to 7 GeV and luminosity greater than 5 × 1034cm-2s-1 at the optimized energy of 4 GeV STCF will adopt the most advanced designs and techniques for third-generation e+e– colliders. These include a double-ring configuration with separate storage rings for electrons and positrons with sufficient circumferences of above 800 m, a large Piwinski angle (total crossing angle of 60 mrad) and a crab-waist collision scheme, high stored beam currents (≈2 A), low emittance (horizontal emittance of approximately 5 nm·rad, with transverse coupling below 1%), and extremely small

In the crab-waist scheme, sextupole magnets near the IP rotate the beam-waist orientation, which, combined with strong focusing optics, significantly reduces the dynamic and momentum acceptances of the ring. This not only complicates beam injection but also leads to an extremely short beam lifetime (<300 s), primarily limited by Touschek scattering. This beam lifetime is far shorter than in other electron storage rings (colliders and synchrotron radiation light sources) and imposes significant challenges on both collider ring physics design and technical design.

In addition, STCF is designed to operate in a top-up mode, requiring frequent beam injection to maintain a quasi-constant current. The very short beam lifetime in the collider rings poses great beam injection and injector design challenges. Currently, two injection schemes for the collider rings are under parallel development: a conventional off-axis injection scheme and a state-of-the-art bunch swap-out injection scheme. They require very different bunch charges for beam injection: approximately 1 and 8 nC for the off-axis and swap-out injection schemes. Accordingly, the injector should be designed to follow the injection schemes.

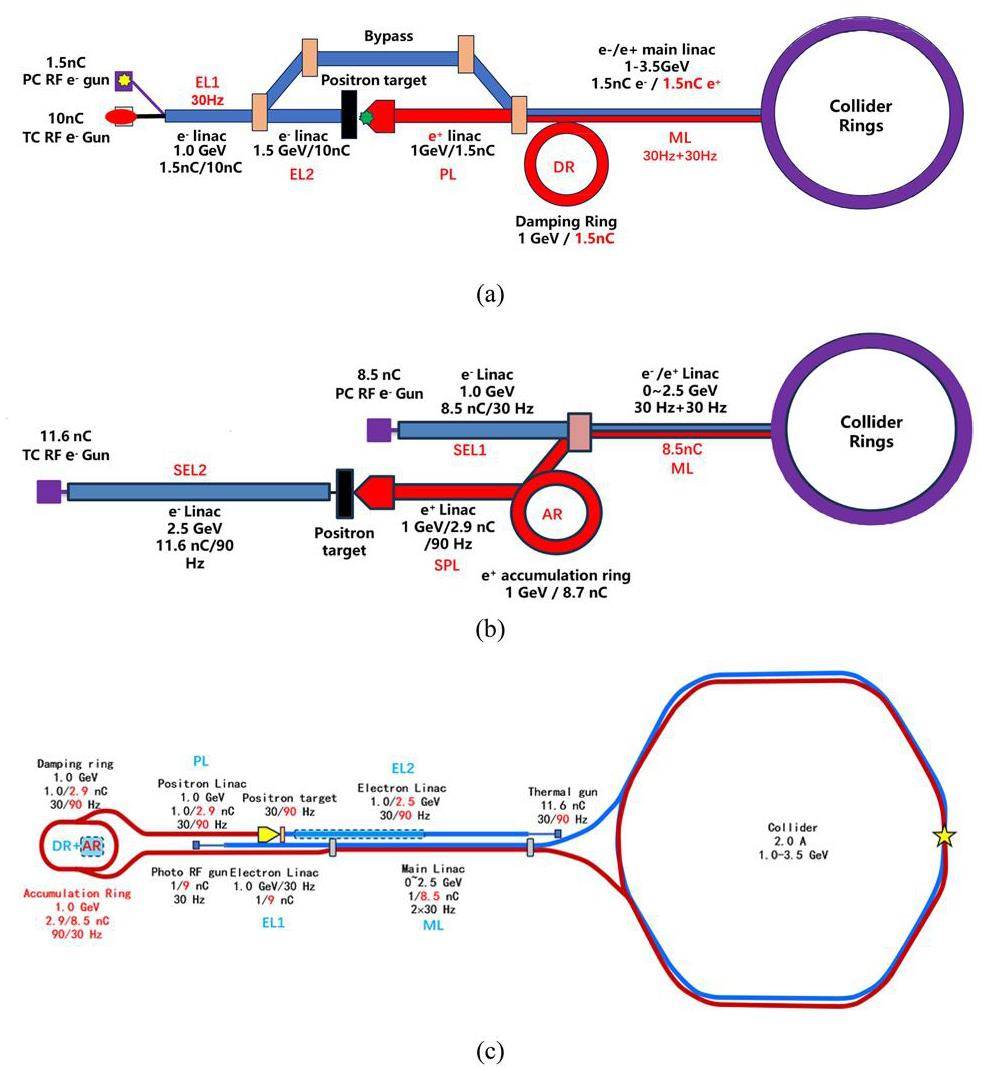

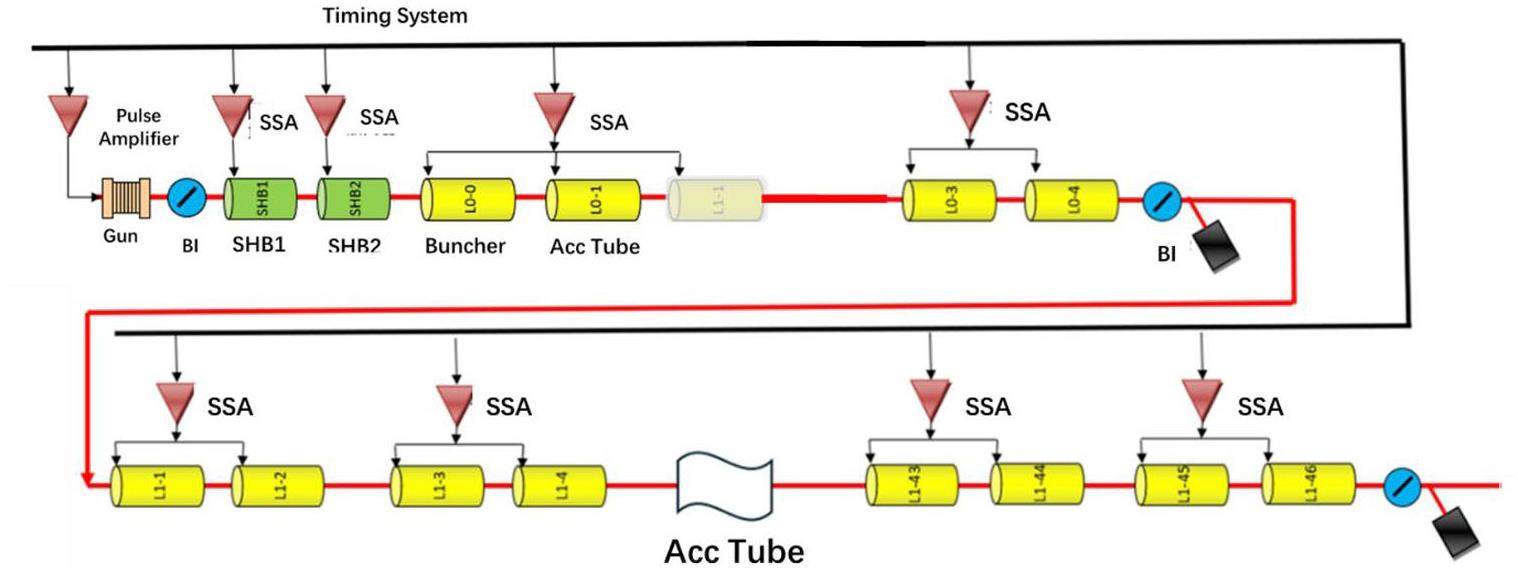

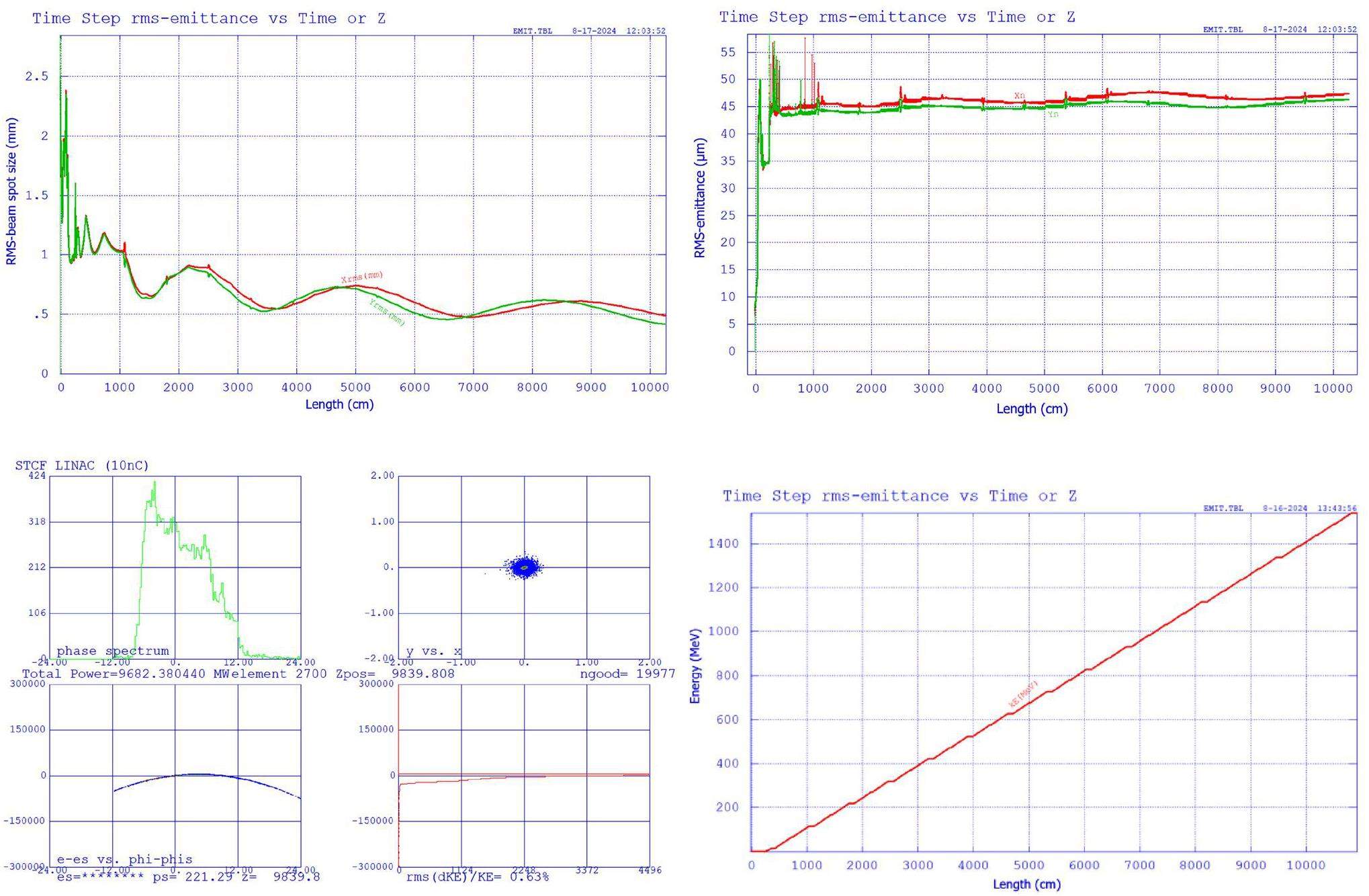

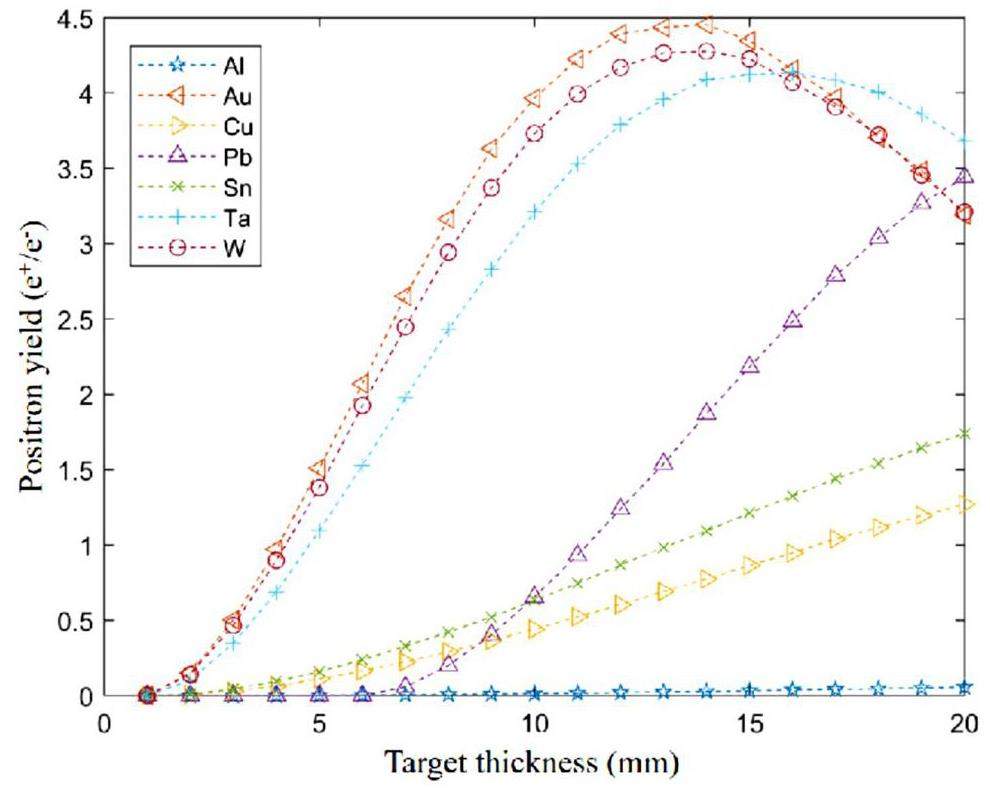

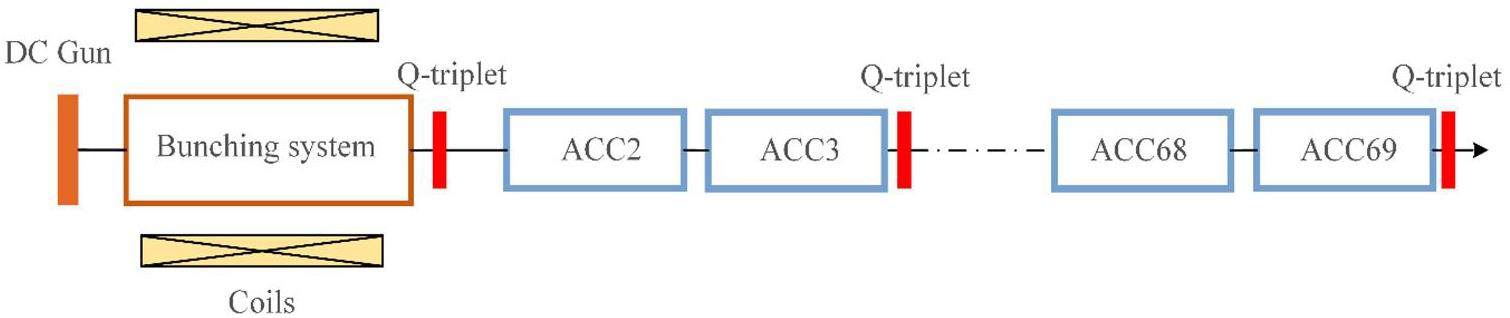

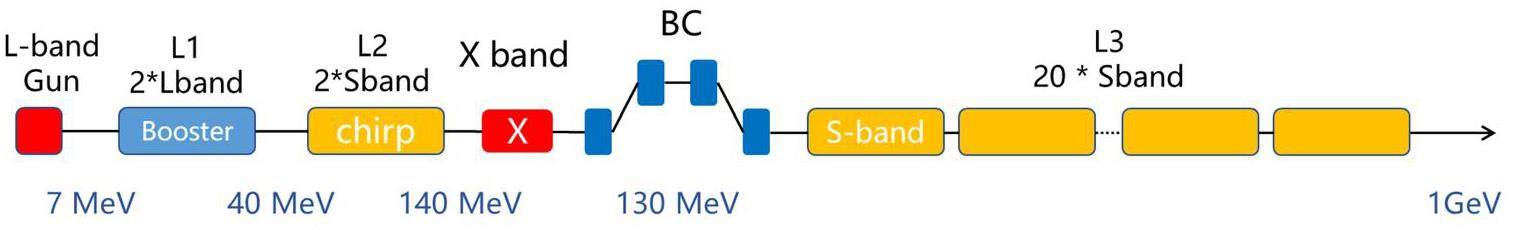

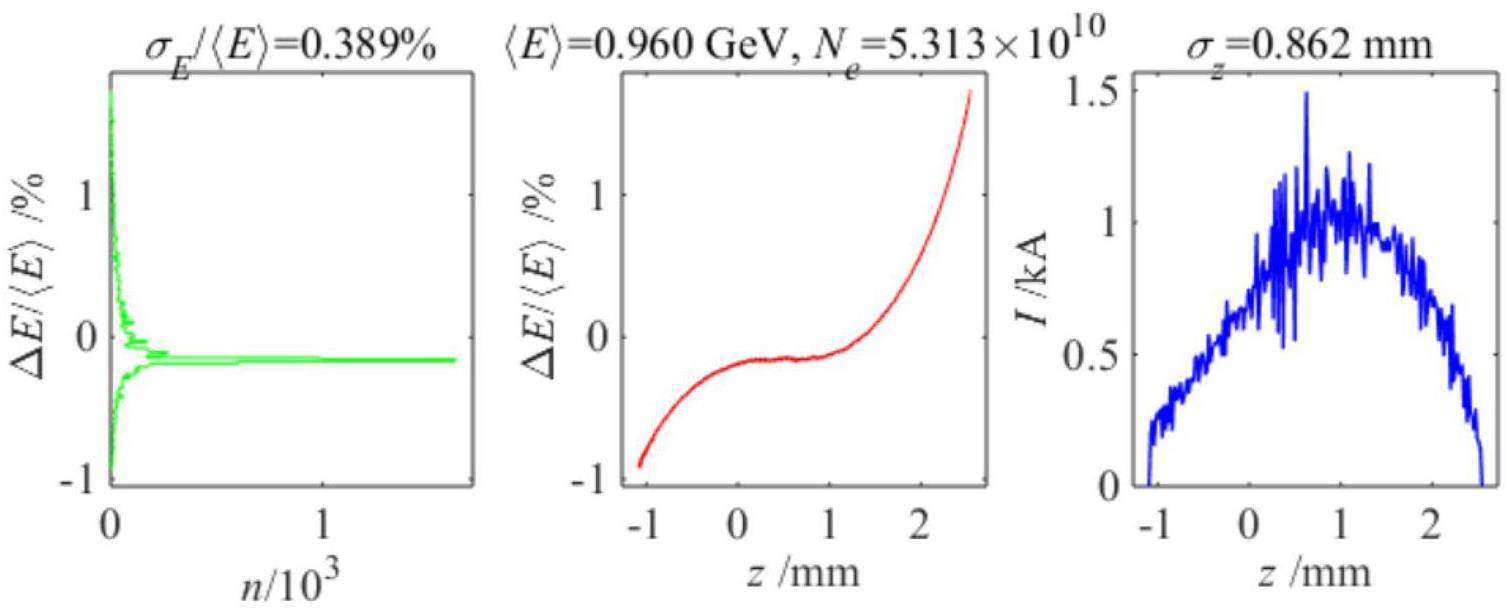

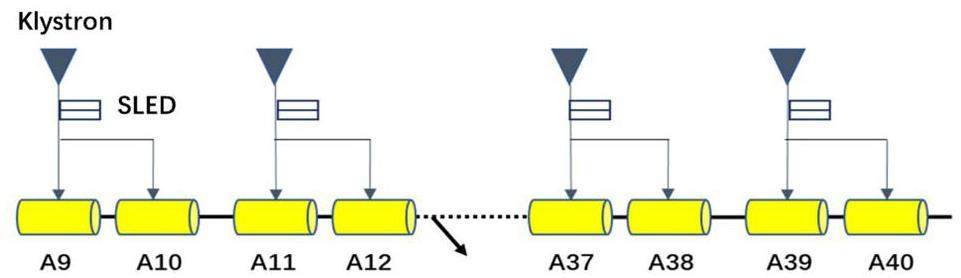

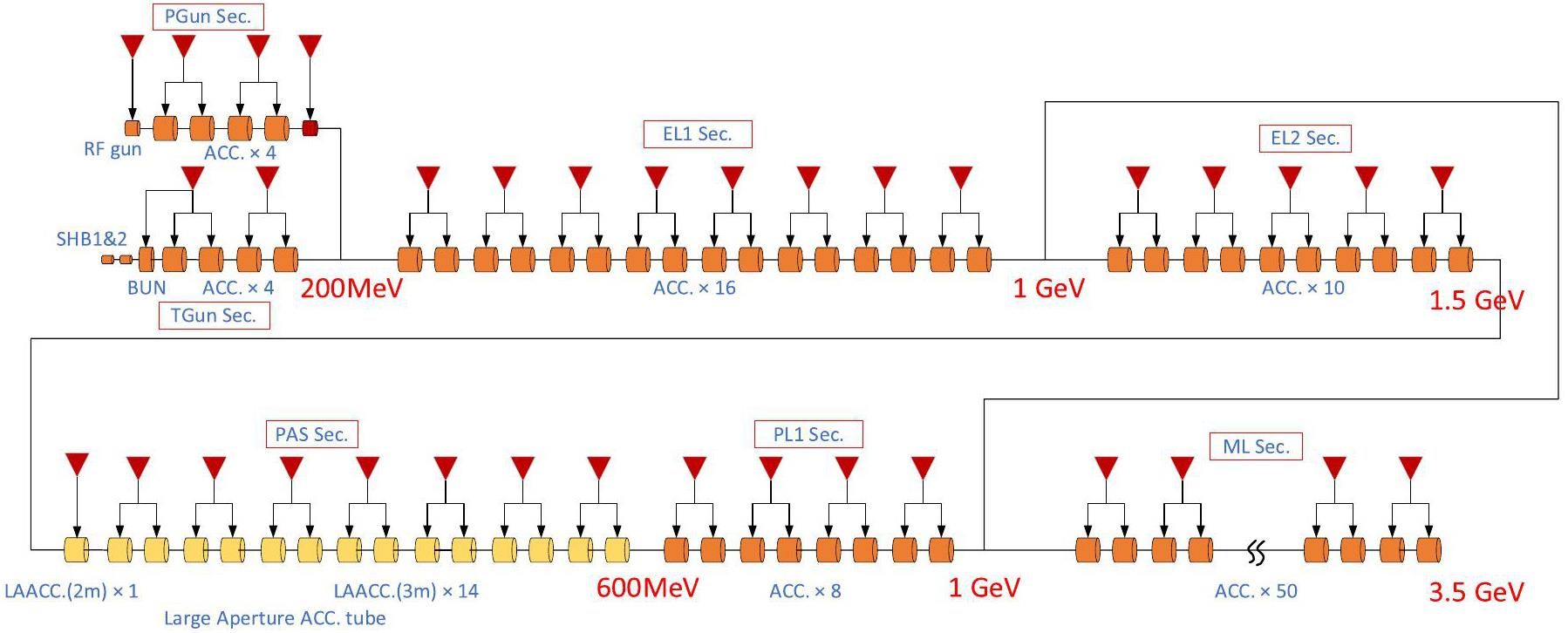

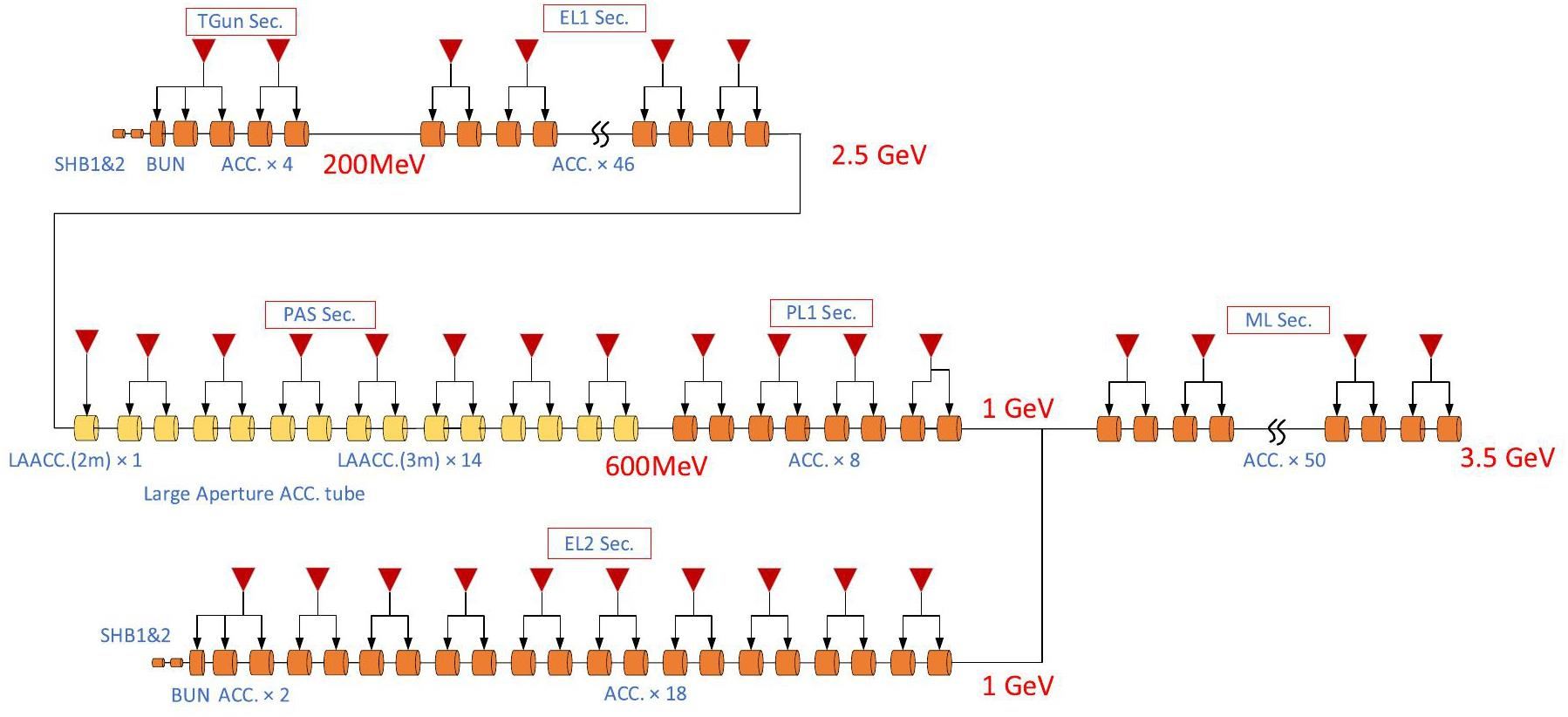

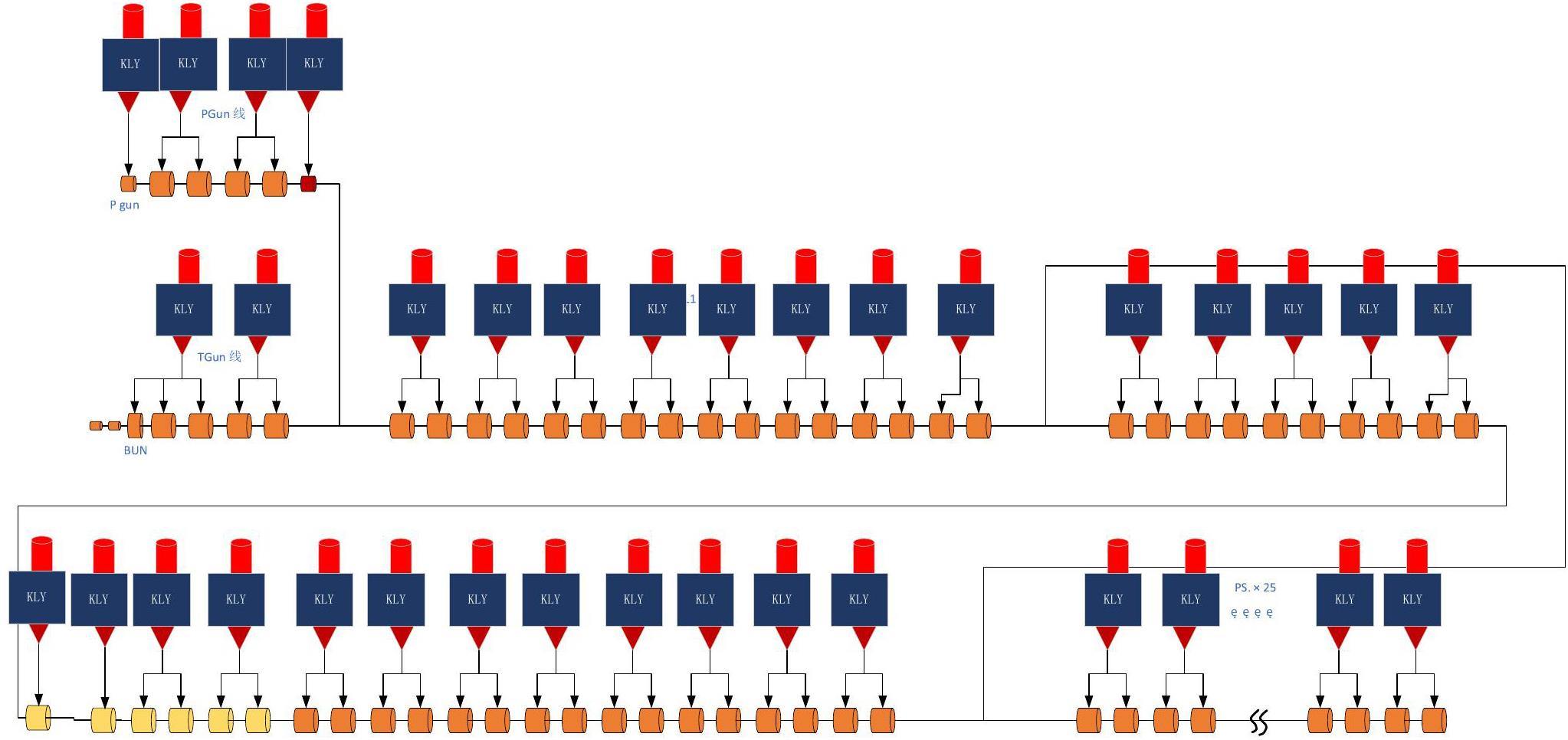

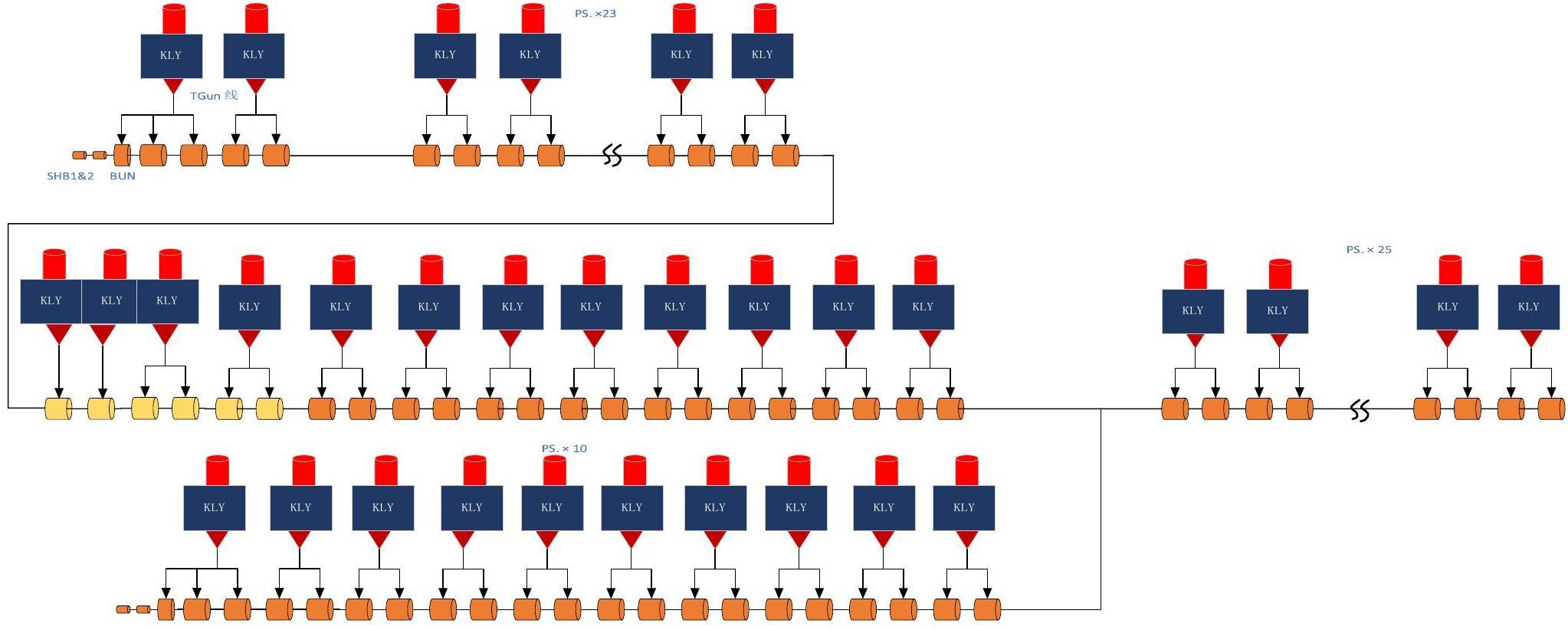

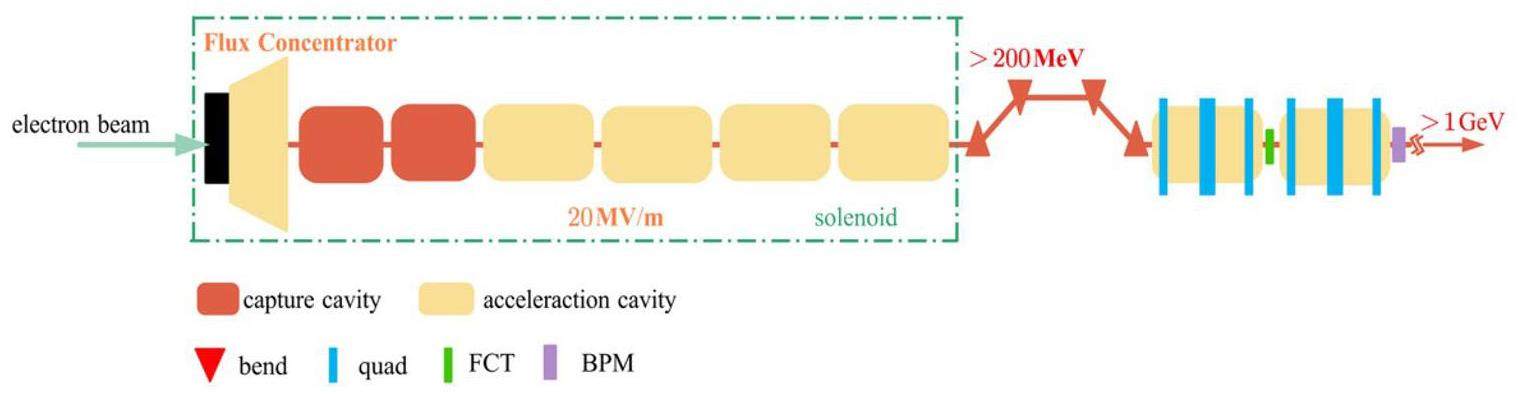

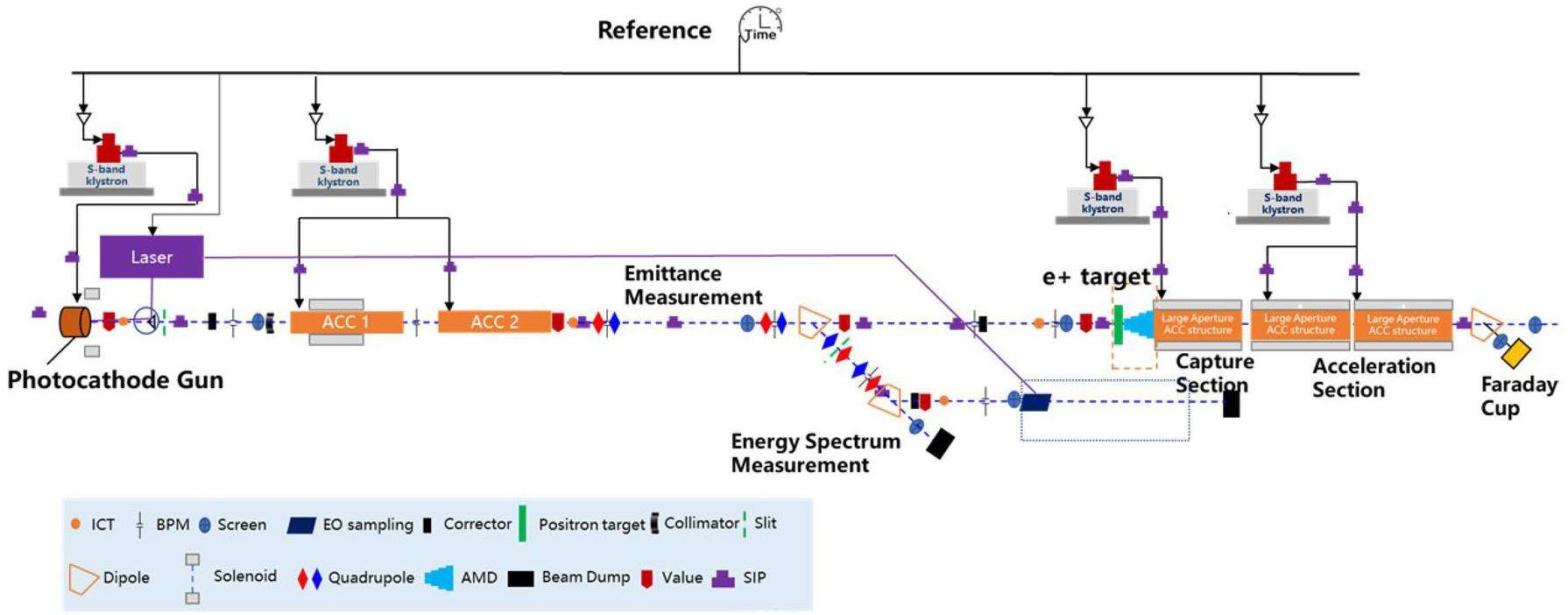

STCF adopts an injector scheme with a full-energy linac, namely the linacs will accelerate both the electron and positron beams to the injection energy of the collider rings, from 1.0 to 3.5 GeV, according to the collider operation energy. This scheme is adopted to realize frequent beam injections in the collider rings. While an electron beam that is pre-accelerated in the linac can be injected into the collider electron ring, the positron beam is first produced by a high-energy and high-current electron beam. As a secondary particle, the positron exhibits low collection efficiency and poor beam quality. The most challenging aspects of the injector design are associated with the positron beam. Different injector designs have been proposed for the off-axis and swap-out injection schemes in the collider rings:

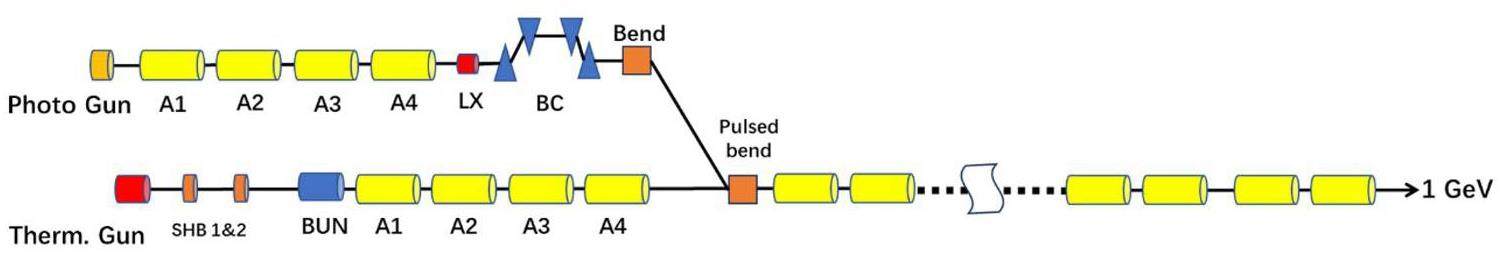

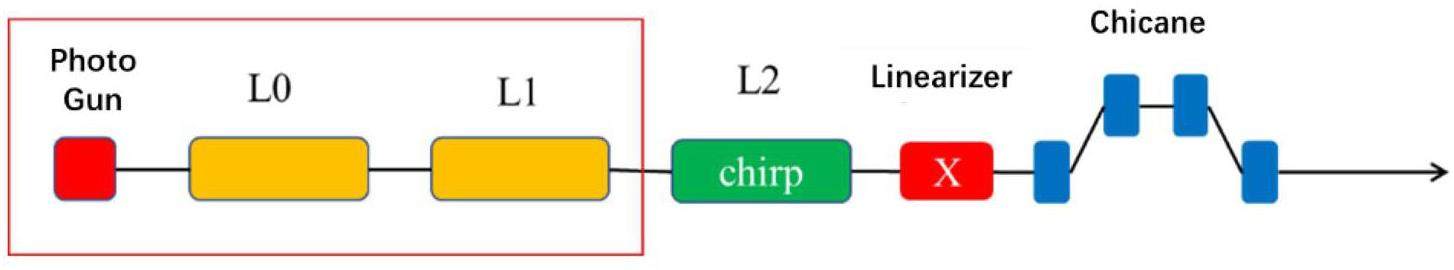

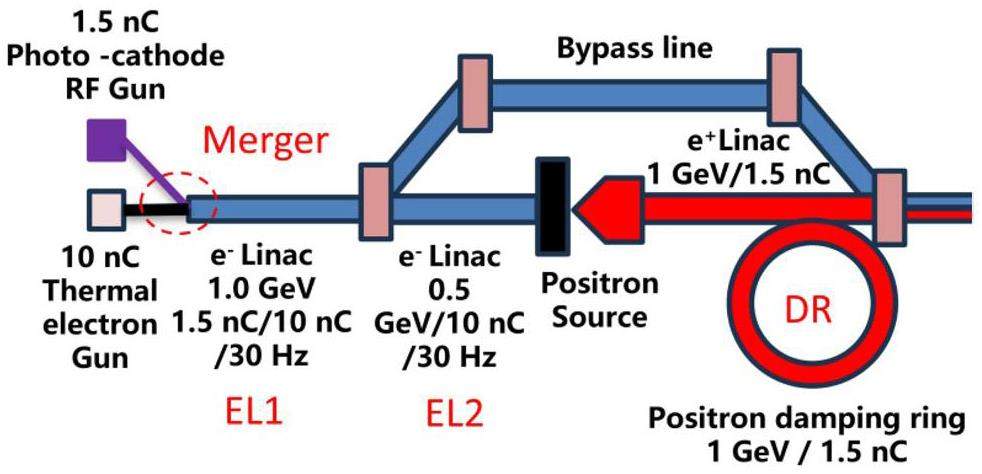

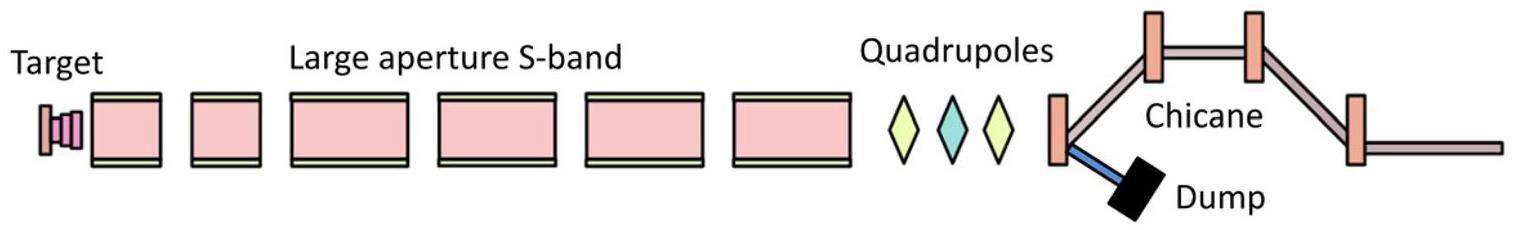

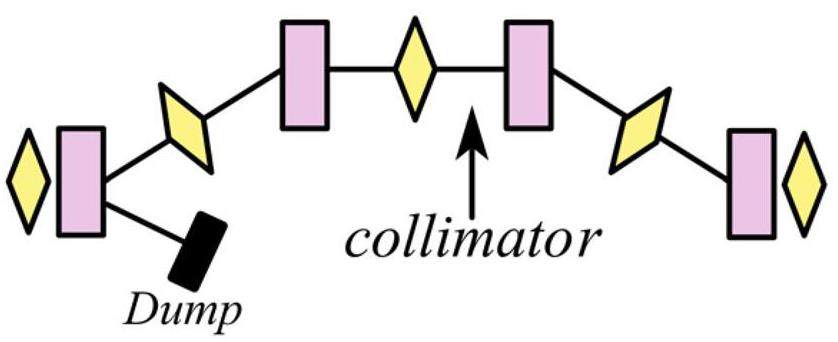

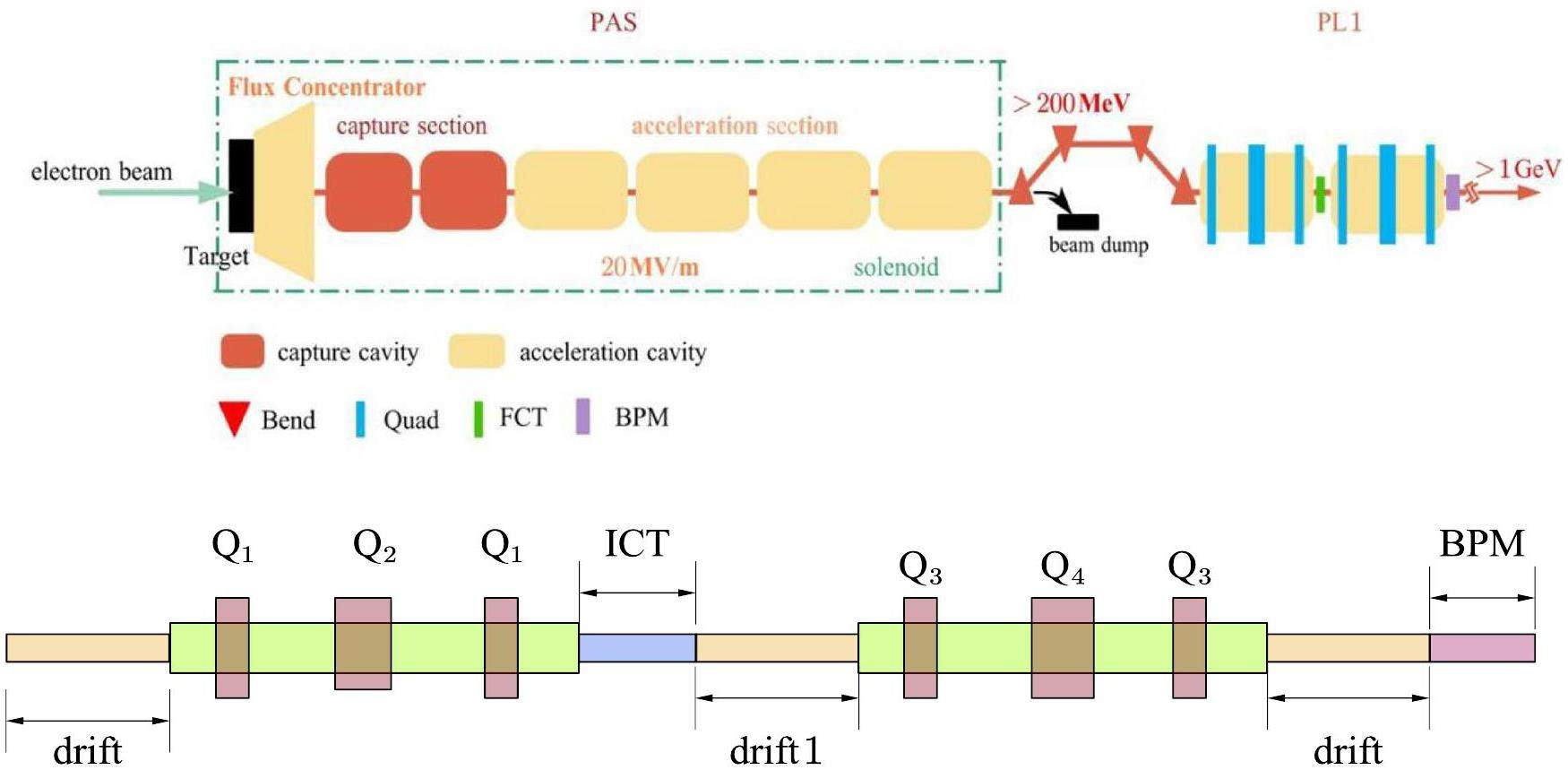

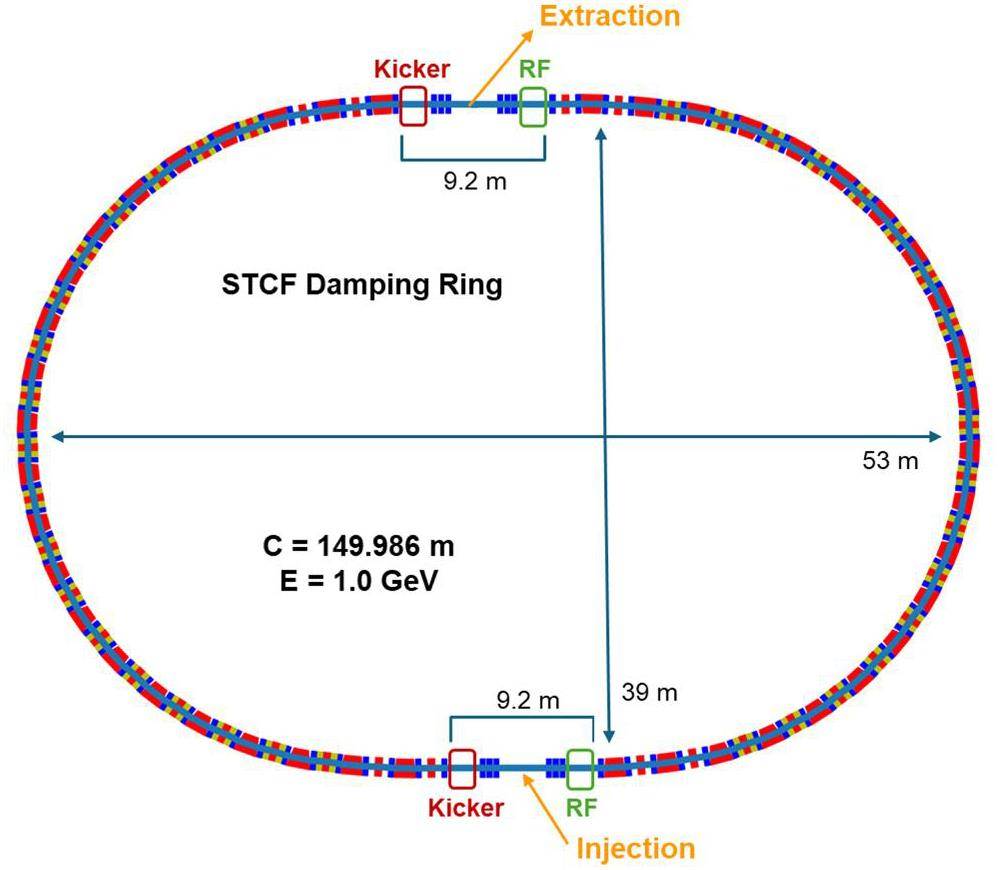

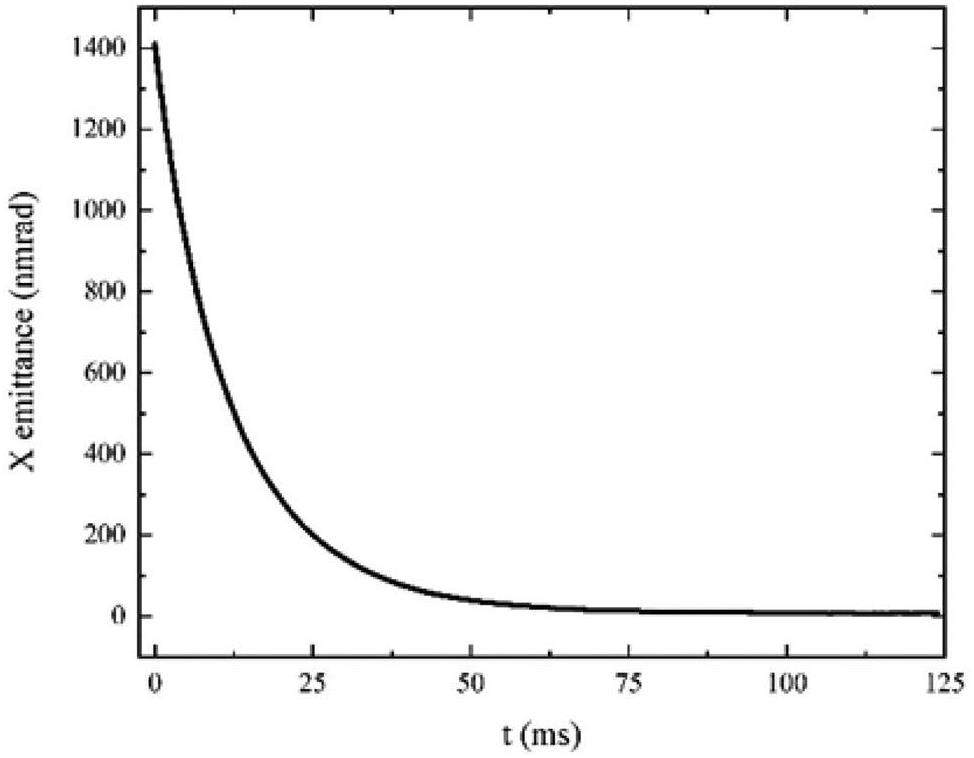

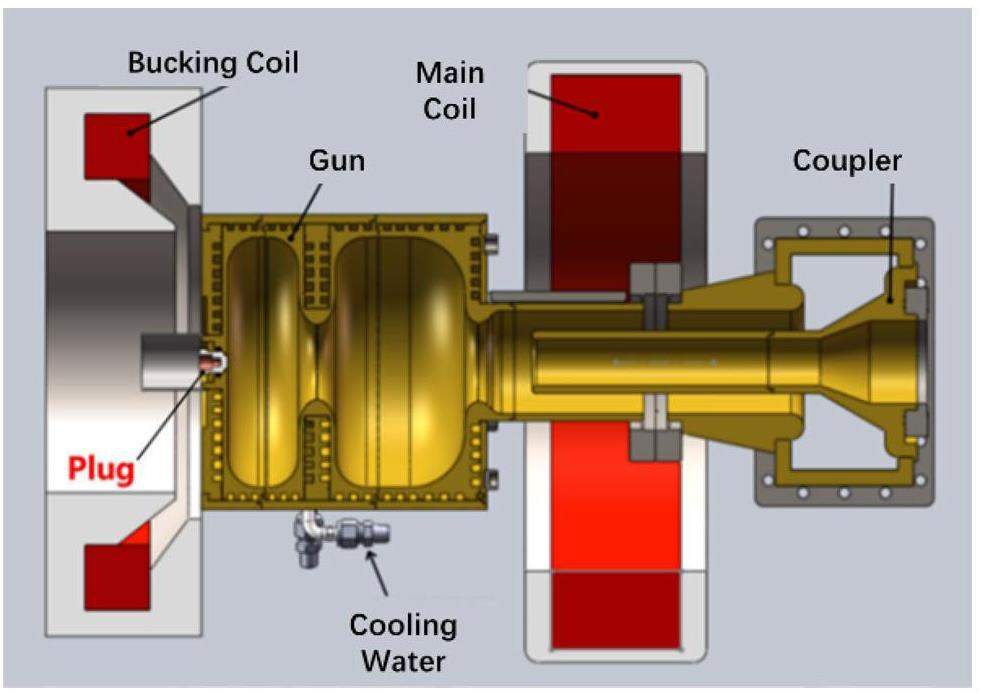

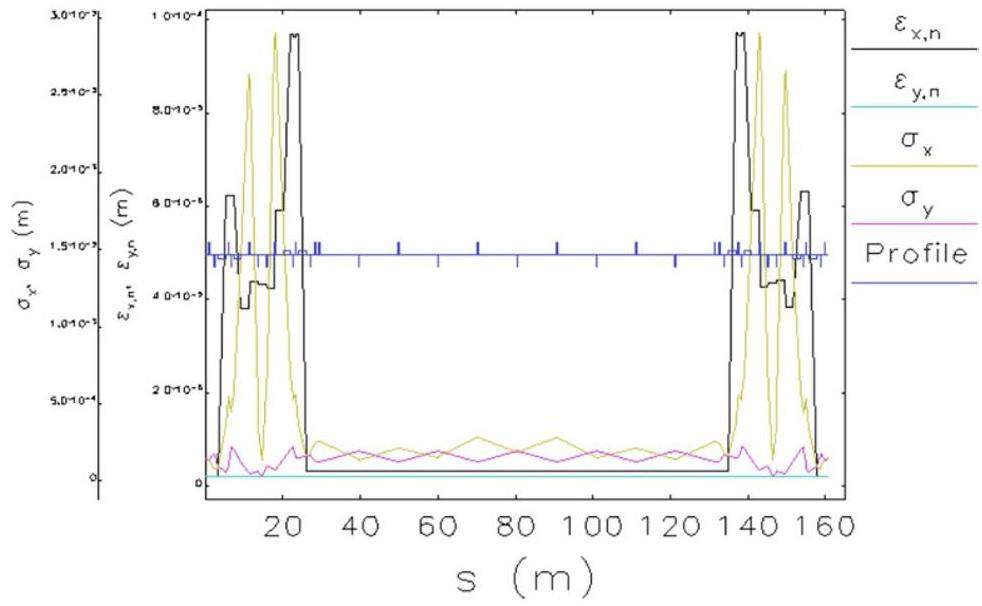

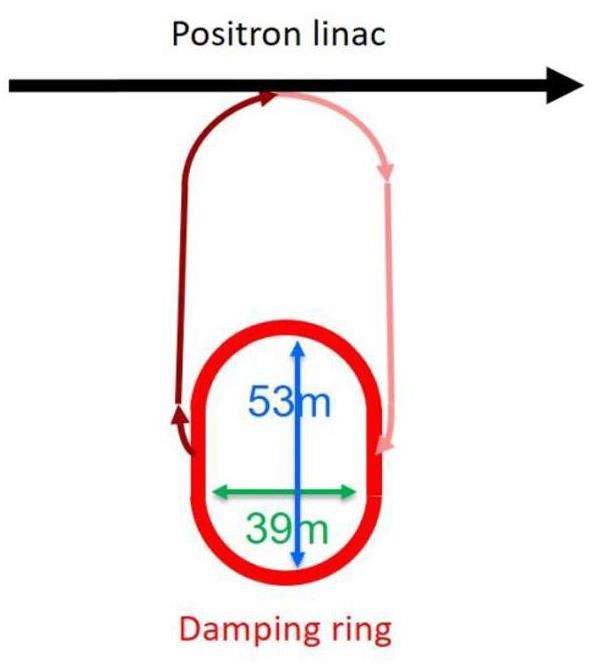

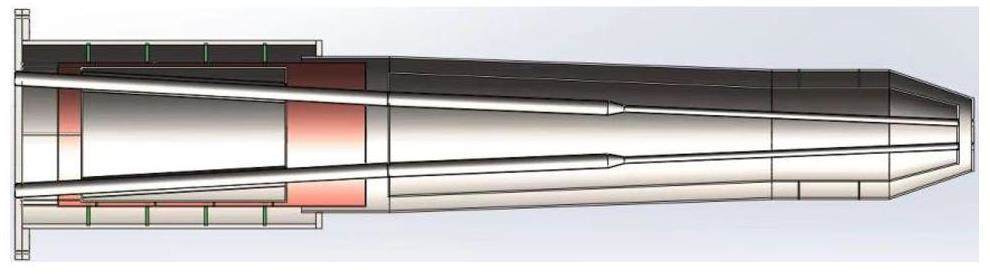

· Off-Axis Injection Scheme: In this scheme, each injection introduces a single electron/positron bunch with a charge of ≤ 1.5 nC using traditional methods. The electron beam is generated by a photocathode (PC) radio frequency (RF) electron gun that provides good beam quality and is directly accelerated to the injection energy. The positron beam is generated using a high-charge, high-energy electron beam on a positron production target. Here, the electron beam is from a thermionic-cathode (TC) RF electron gun and accelerated to 1.5 GeV. These positrons are collected, accelerated to 1.0 GeV, damped in a damping ring (DR), and reaccelerated to the required injection energy (see Fig. 1, top).

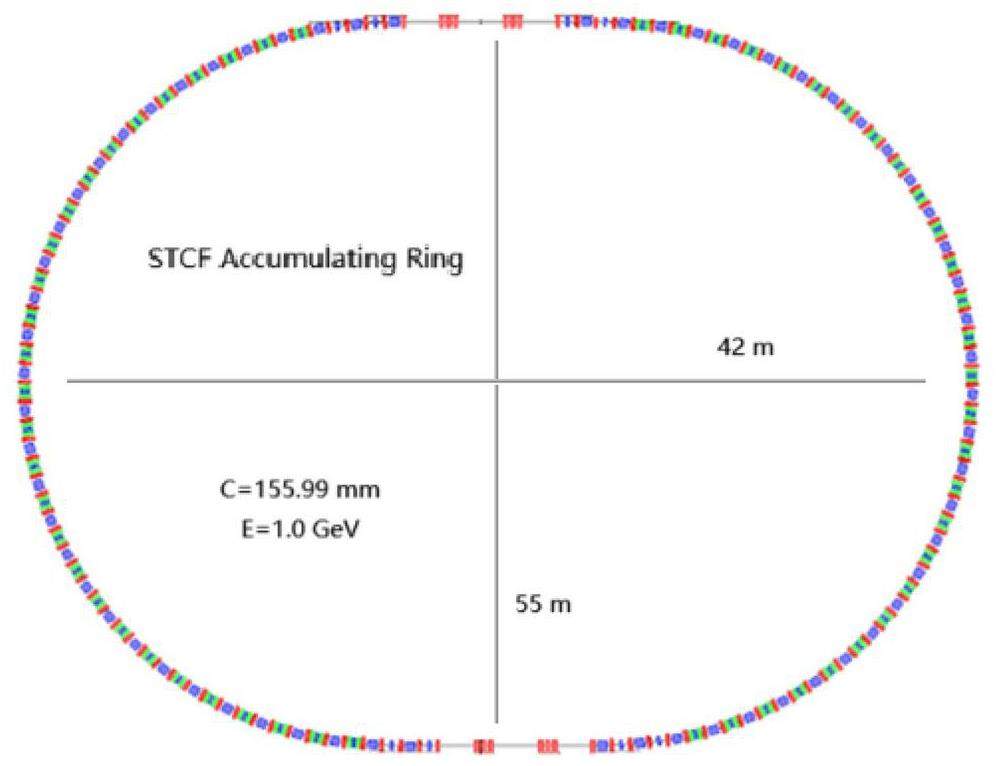

· Bunch Swap-out Injection Scheme: In this scheme, at each injection, a high-charge (8.5 nC) bunch is required for both electrons and positrons. The electron beam for direct injection into the collider electron ring is still generated by a PC gun, but with a higher bunch charge of 8.5 nC. The electron beam that produces positrons is also generated from a thermionic gun, but with an even higher bunch charge of 11.6 nC and accelerated to 2.5 GeV with a high repetition rate of 90 Hz. Subsequently, the positrons are collected, captured, accelerated to 1 GeV, and accumulated in an accumulation ring with strong damping to achieve low emittance before acceleration in the main linac (ML) and final injection into the collider positron ring (see Fig. 1, middle).

Regardless of whether the off-axis injection or swap-out injection is used, the ML should accelerate both the electron and positron beams alternately at a maximum of 30 Hz each. It will be capable of adjusting the energy of both electron and positron beams across the 1.0–3.5 GeV range according to the operating energy of the collider rings.

Based on feasibility studies, a compatible injector scheme (see Fig. 1, bottom) has been proposed. With this scheme, the linac tunnel hosts two linacs in two opposite directions. The off-axis injection mode is chosen as the baseline scheme since it is a mature and cheaper solution. The electron beam energy that drives the positron target is reduced to 1 GeV, which produces positron bunches with a charge of 1 nC. The bunch charges for both electrons and positrons for the injection into the collider rings are 1 nC. However, if the future study and operation find that the bunch swap-out injection mode is required to address challenges related to the strong coupling between the injected beam and beam–beam effect, the injector can be straightforwardly upgraded to the full bunch swap-out injection mode by increasing the drive electron beam energy to 2.5 GeV and the repetition rate to 90 Hz. The positron bunch charge is accumulated to 8.5 nC by adding an accumulation ring to the DR to form a dual-ring damping system in the same tunnel.

Key physics design challenges and technologies

As a new-generation electron–positron collider, the STCF accelerator complex not only adopts advanced design concepts but also requires the development of new accelerator physics methodologies and enabling novel accelerator technologies. Based on preliminary studies and international collaborations, several critical areas that require state-of-the-art design techniques and technological innovations, or significantly evolved existing methods, to meet the stringent specifications of the construction and operation of the STCF have been identified.

Collider ring physics design

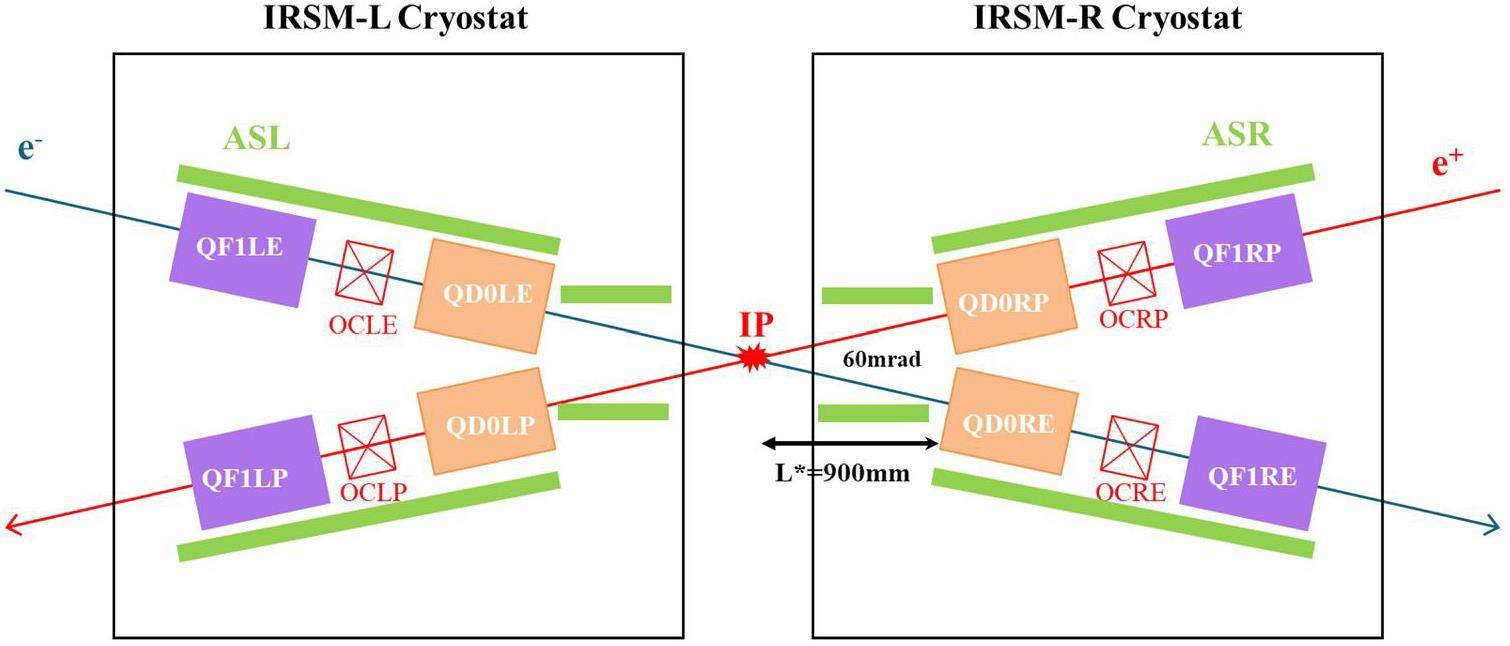

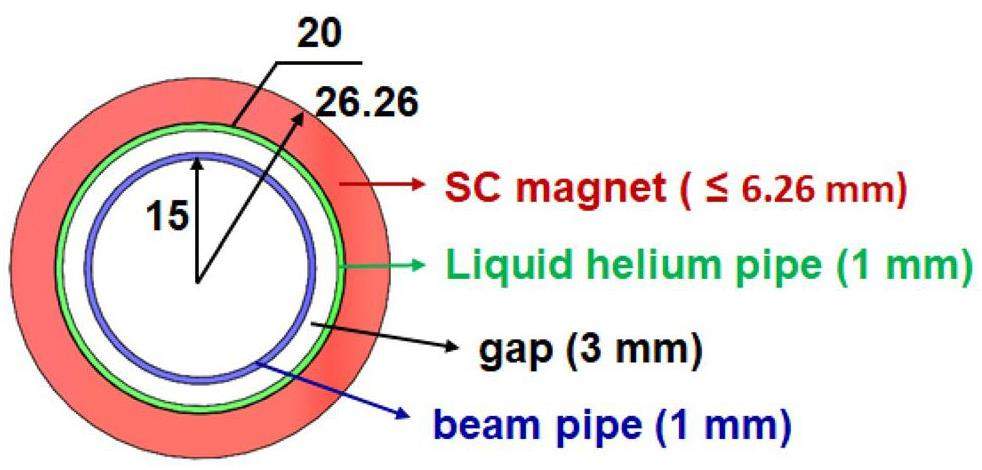

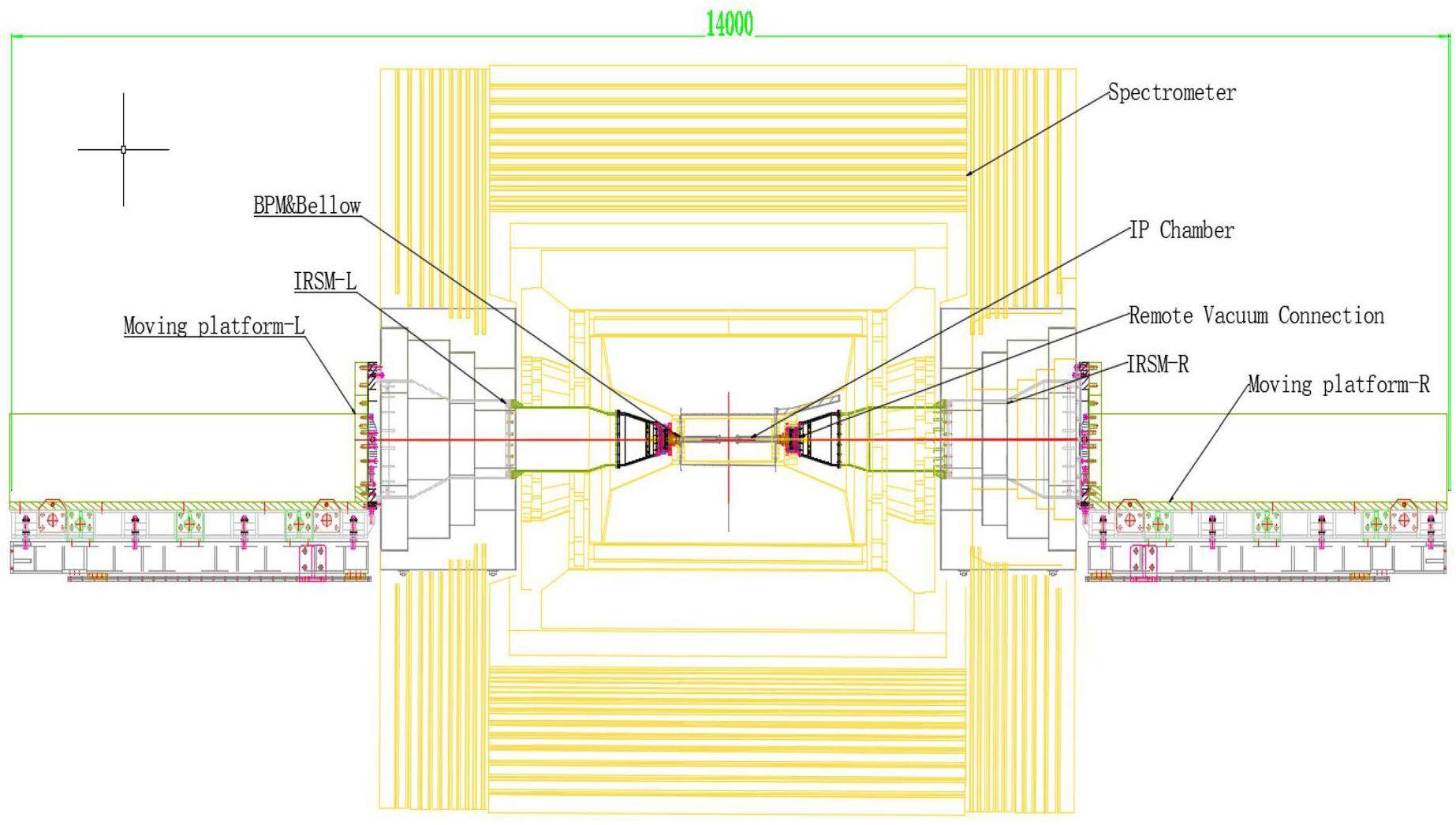

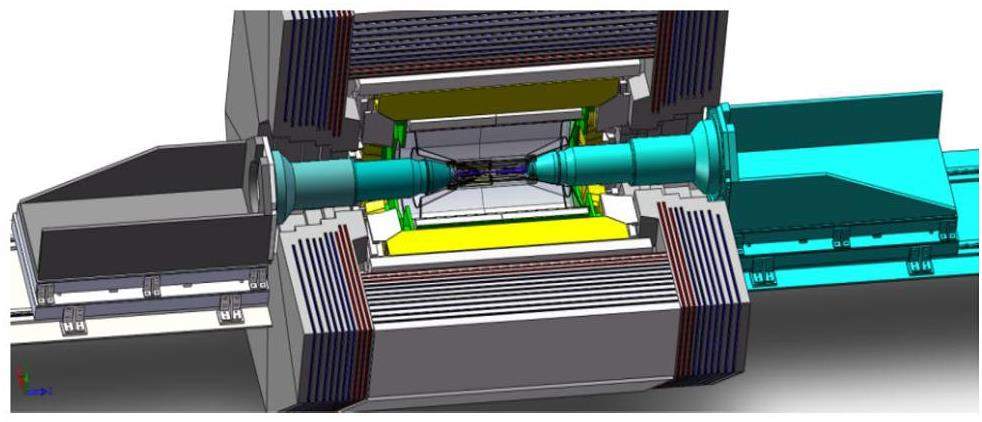

The most challenging aspect of the collider ring design lies in the interaction region (IR). On one hand, ultra-strong focusing is required to achieve extremely small vertical beta functions (

This design complexity is shared across multiple third-generation e+e- collider projects worldwide, each facing varying degrees of difficulty. The SuperKEKB, the only third-generation collider currently in operation, has also struggled to reach its design beam parameters. There is a growing international consensus that new-generation colliders must comprehensively and simultaneously address a wide set of interdependent physics mechanisms, such as strong nonlinearities, Touschek effects, collective instabilities, beam–beam interactions, injection dynamics, machine errors, beam collimation, and radiation damping, through an integrated design approach. Traditionally, these physical mechanisms are studied independently. Existing simulation tools must therefore be upgraded to accommodate such complex, multi-physics studies.

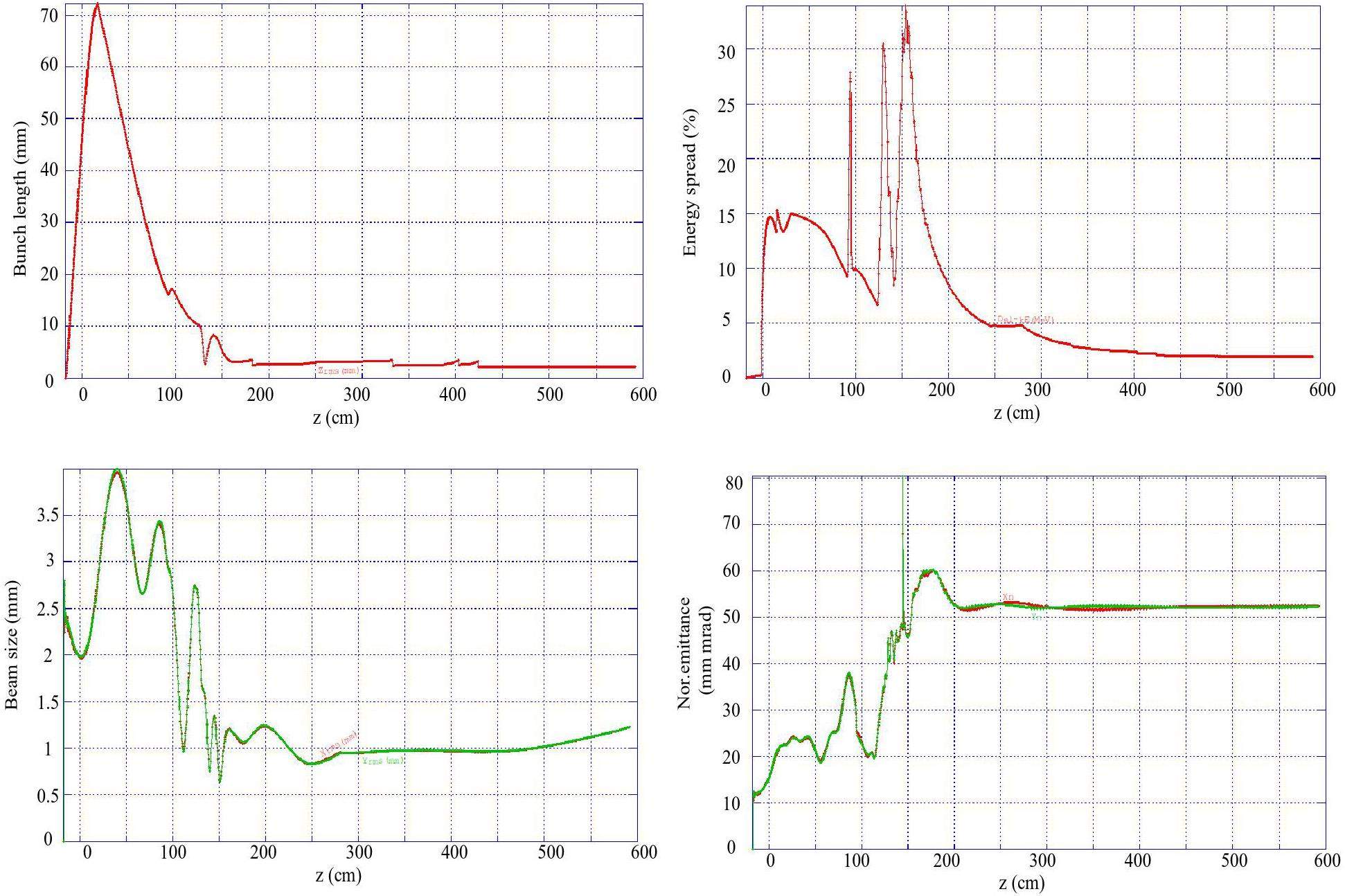

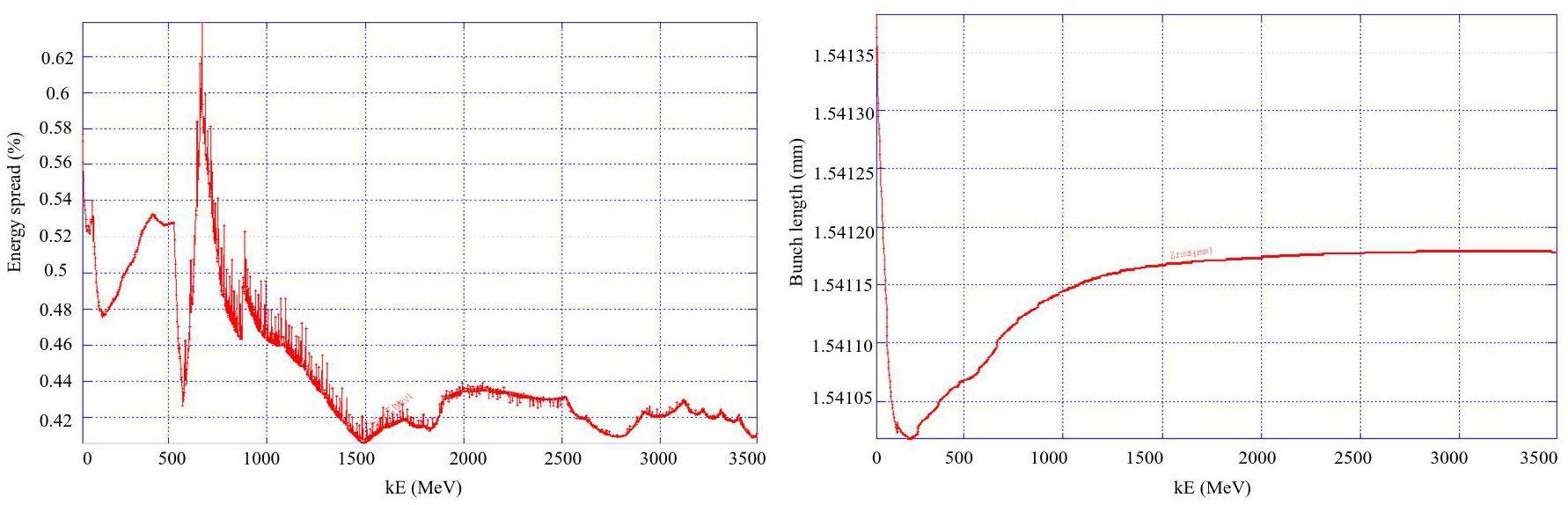

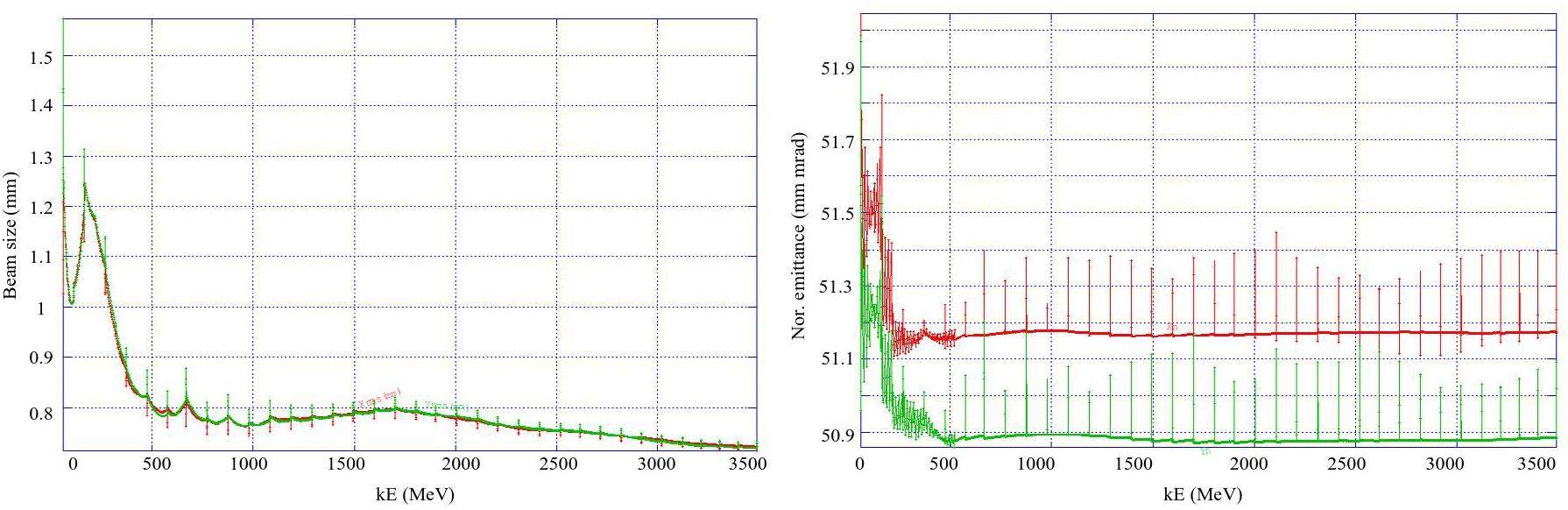

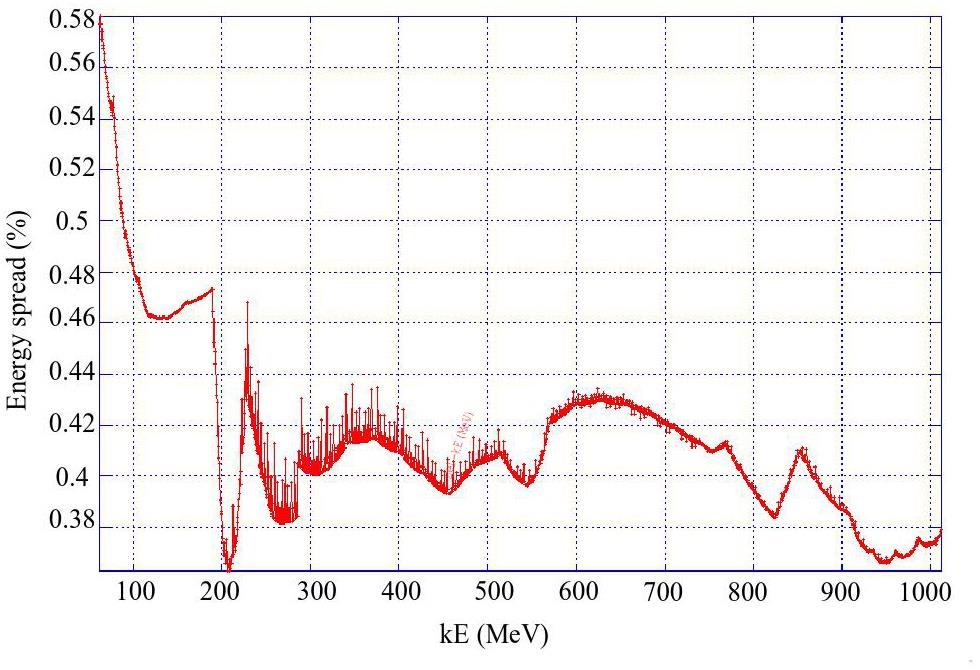

Injector physics design

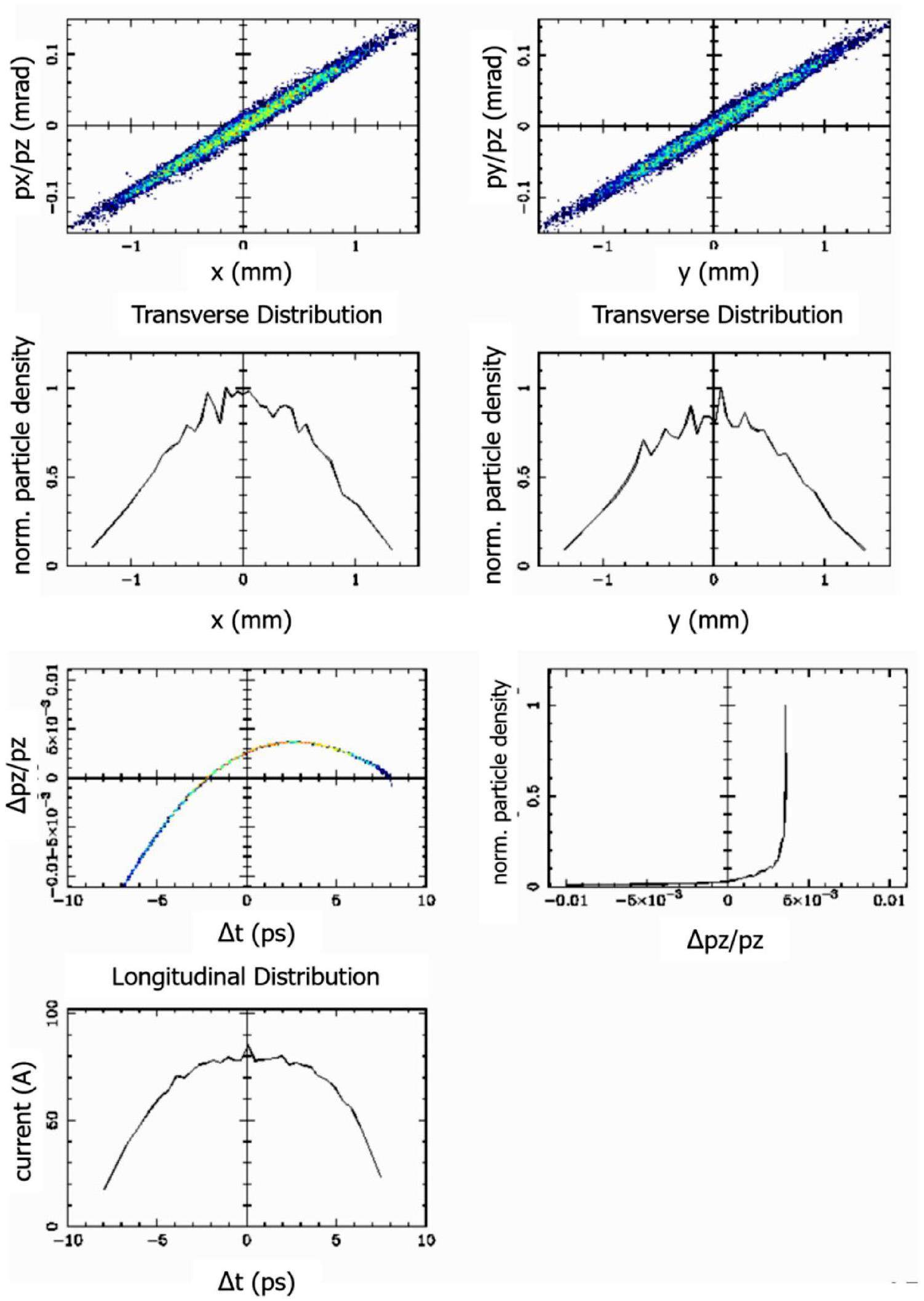

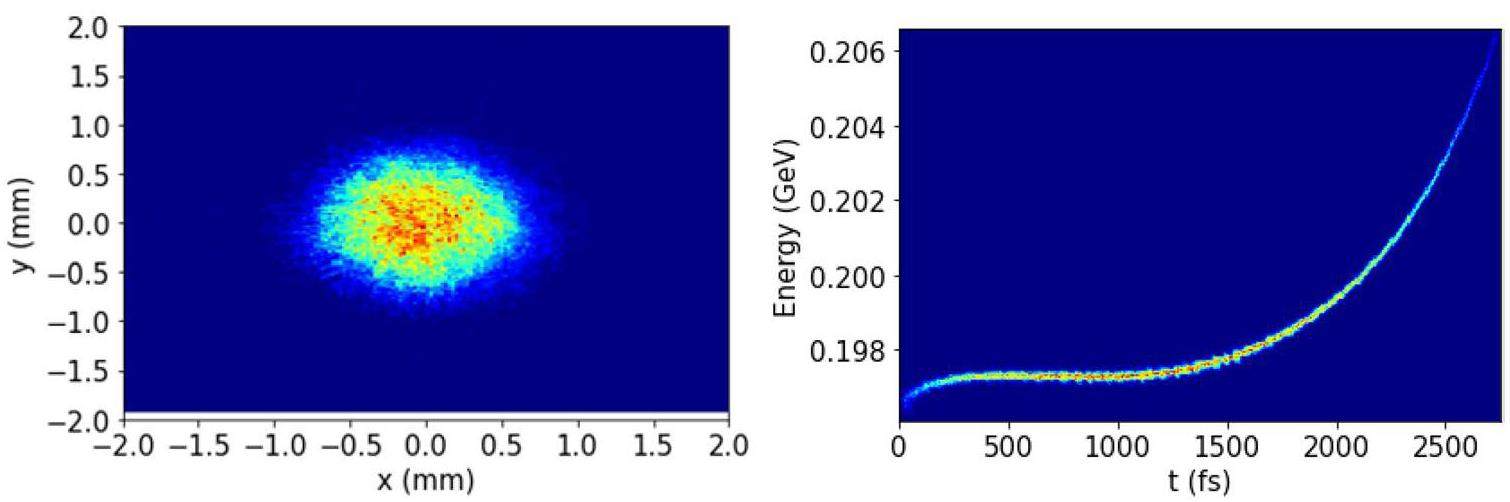

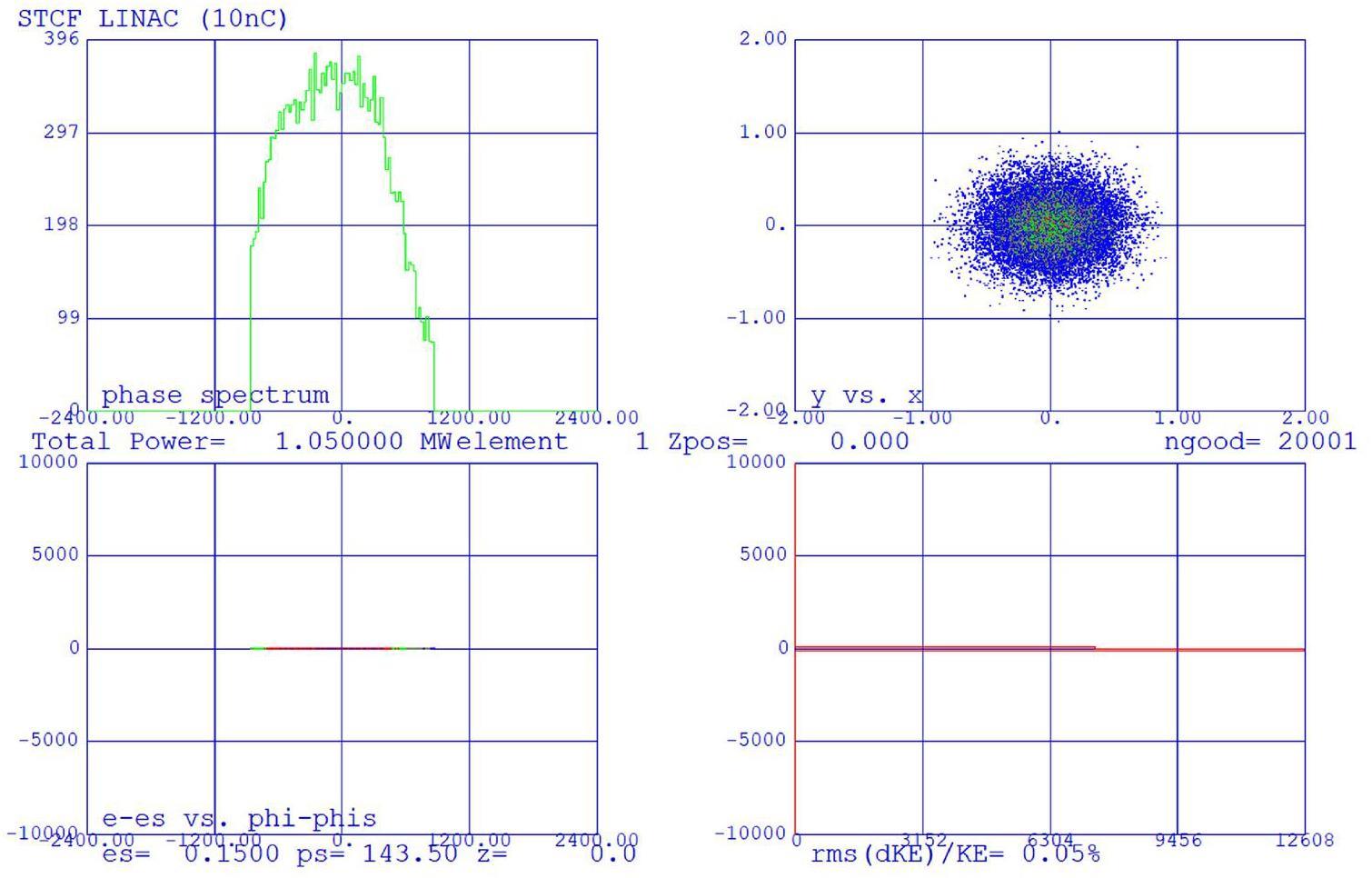

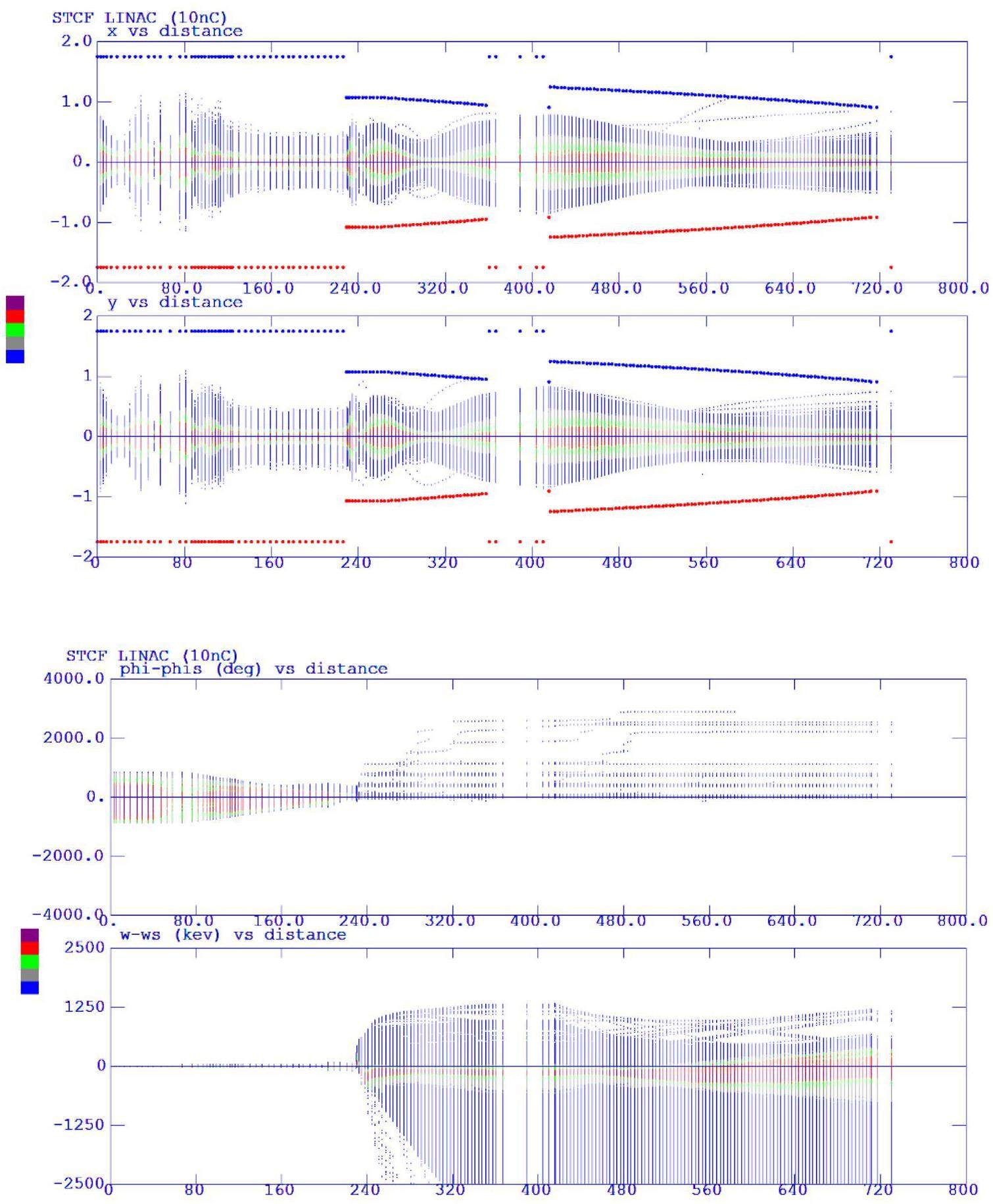

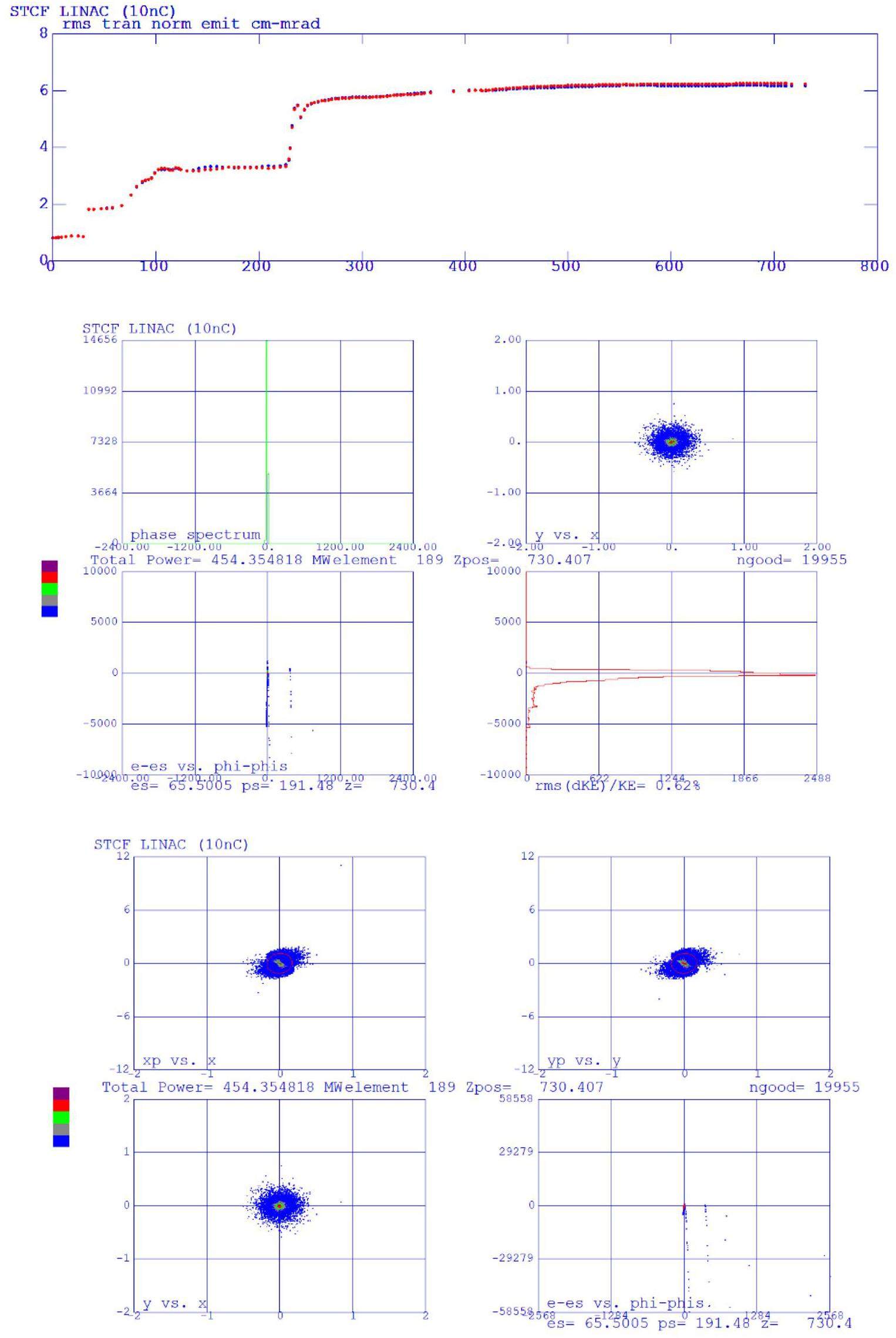

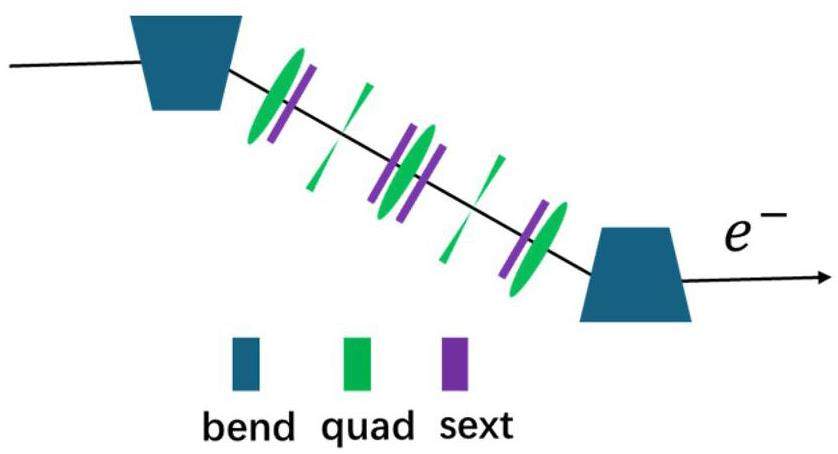

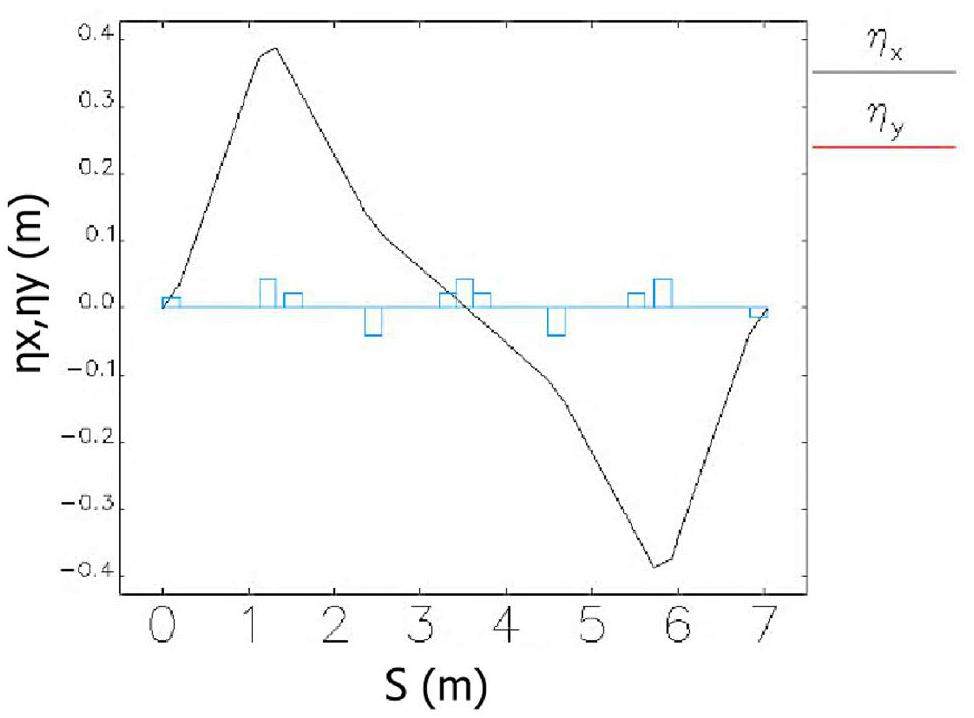

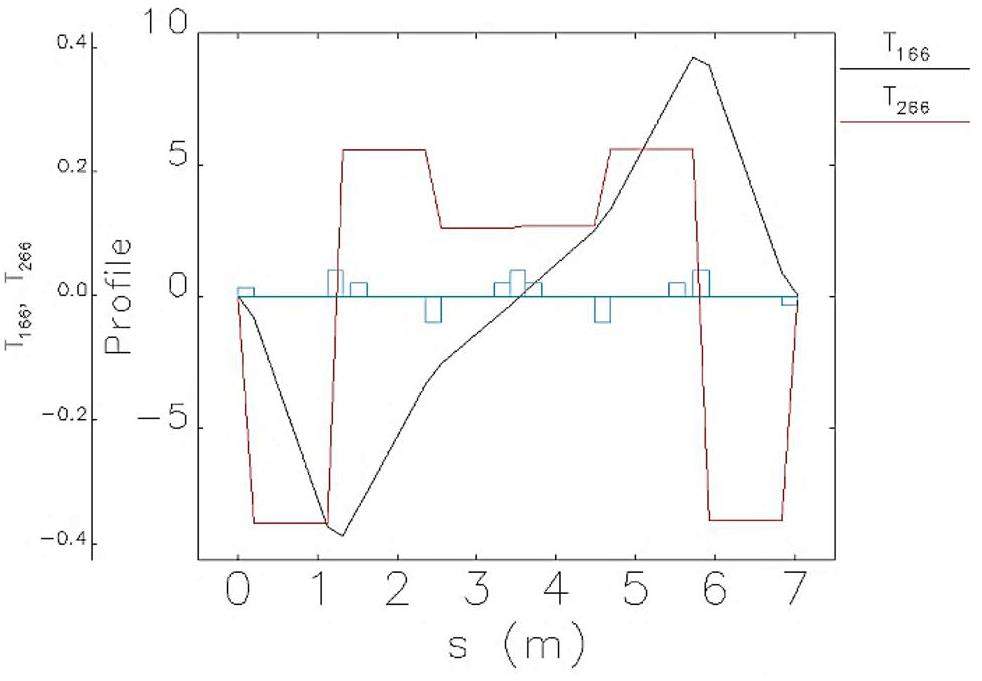

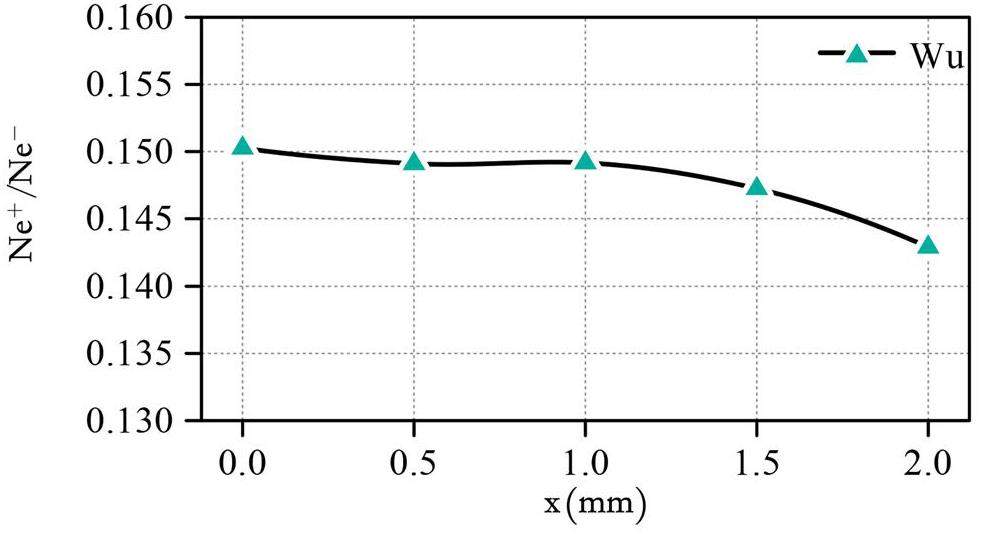

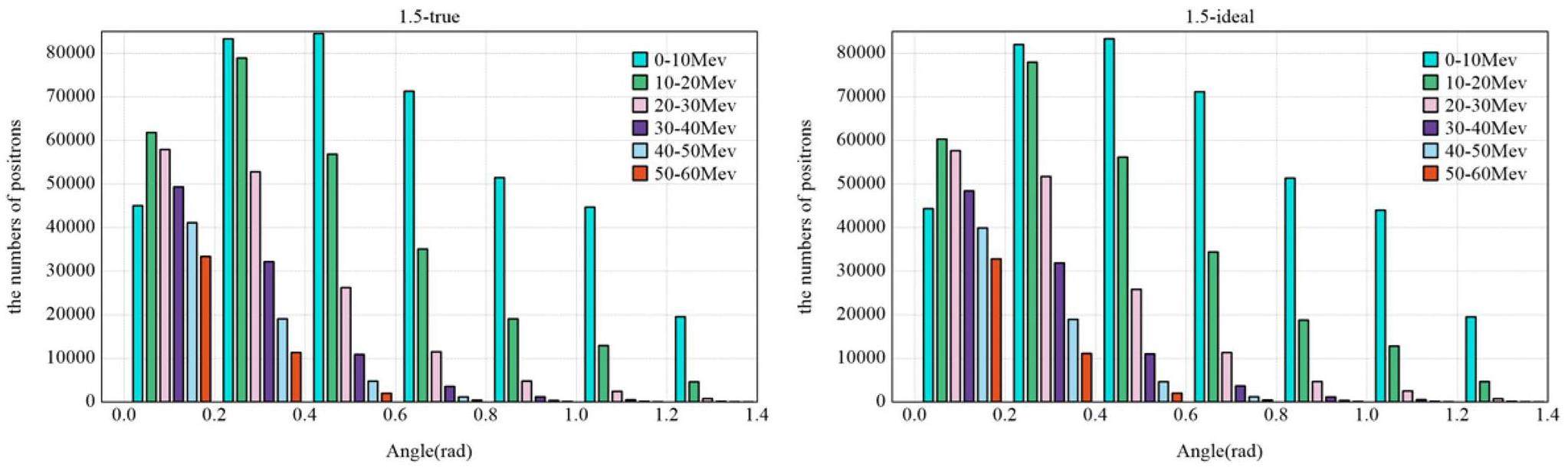

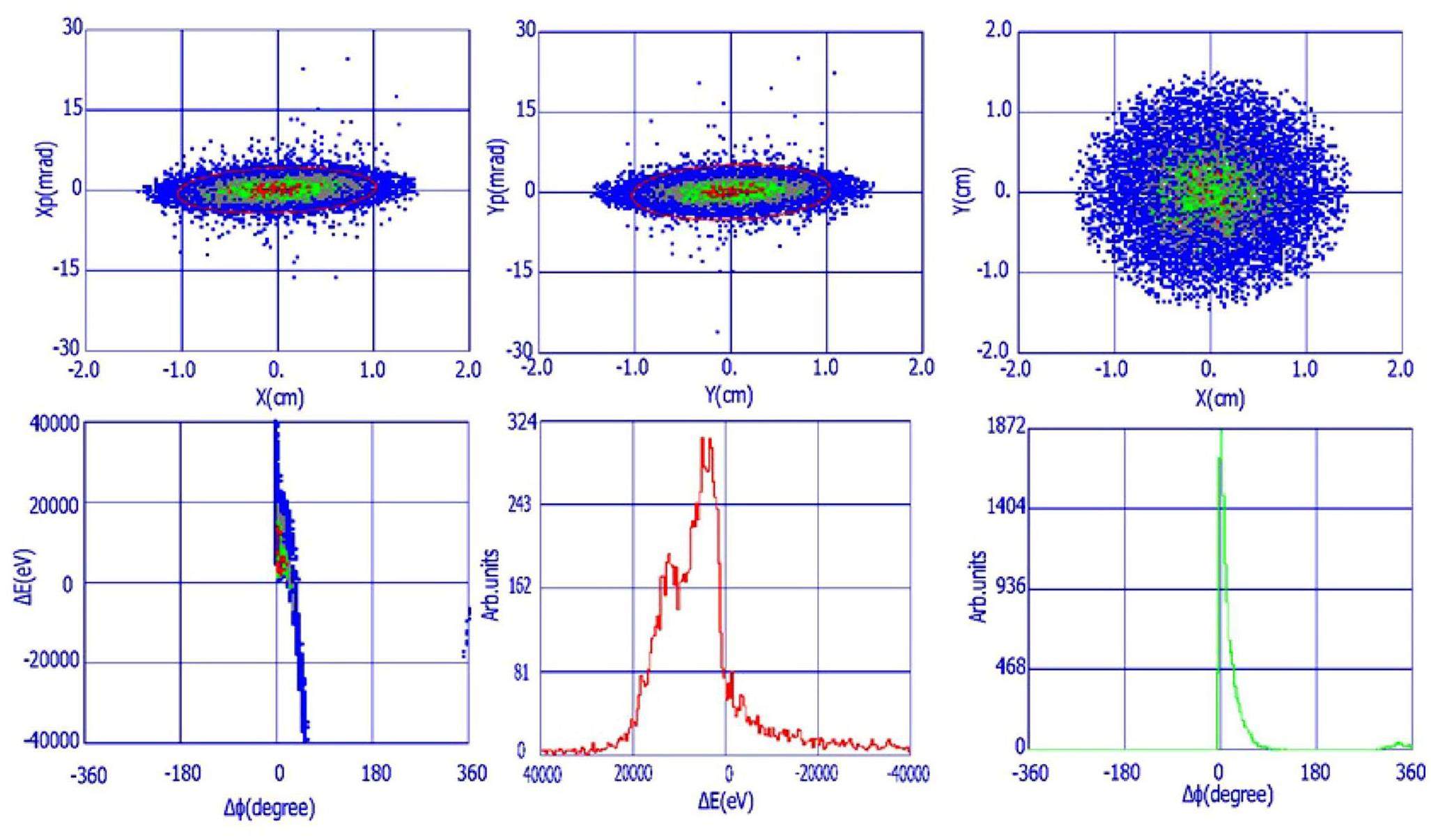

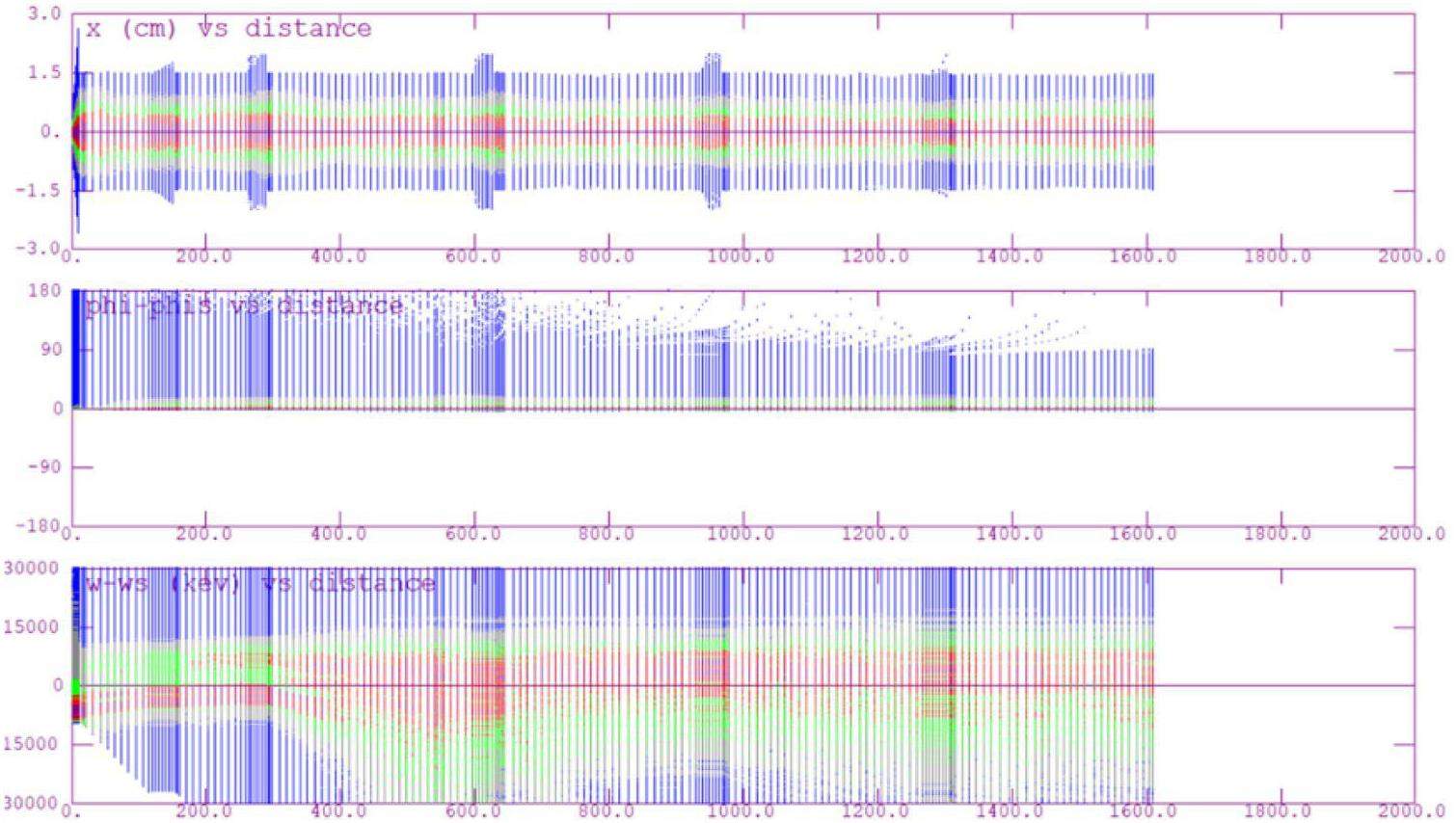

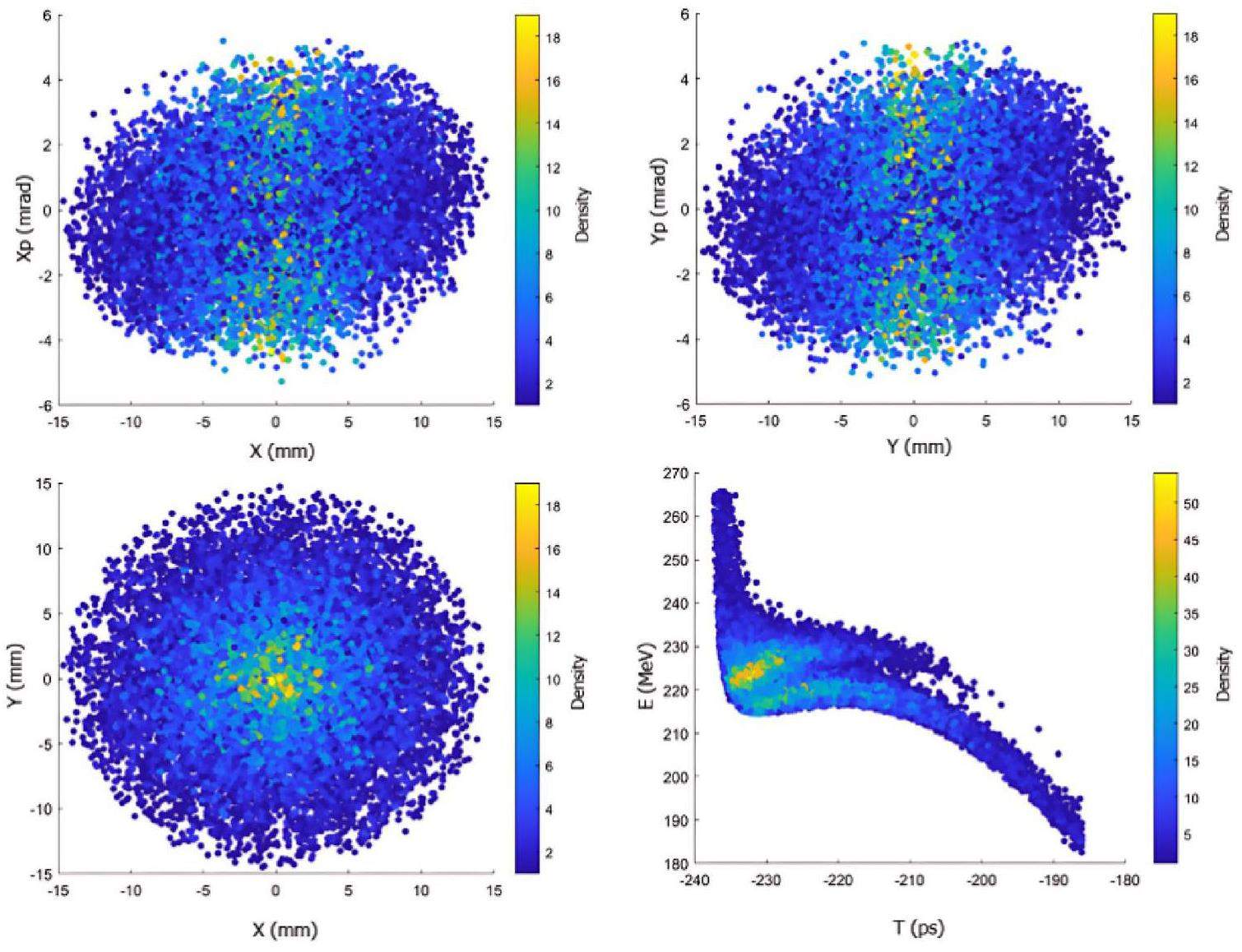

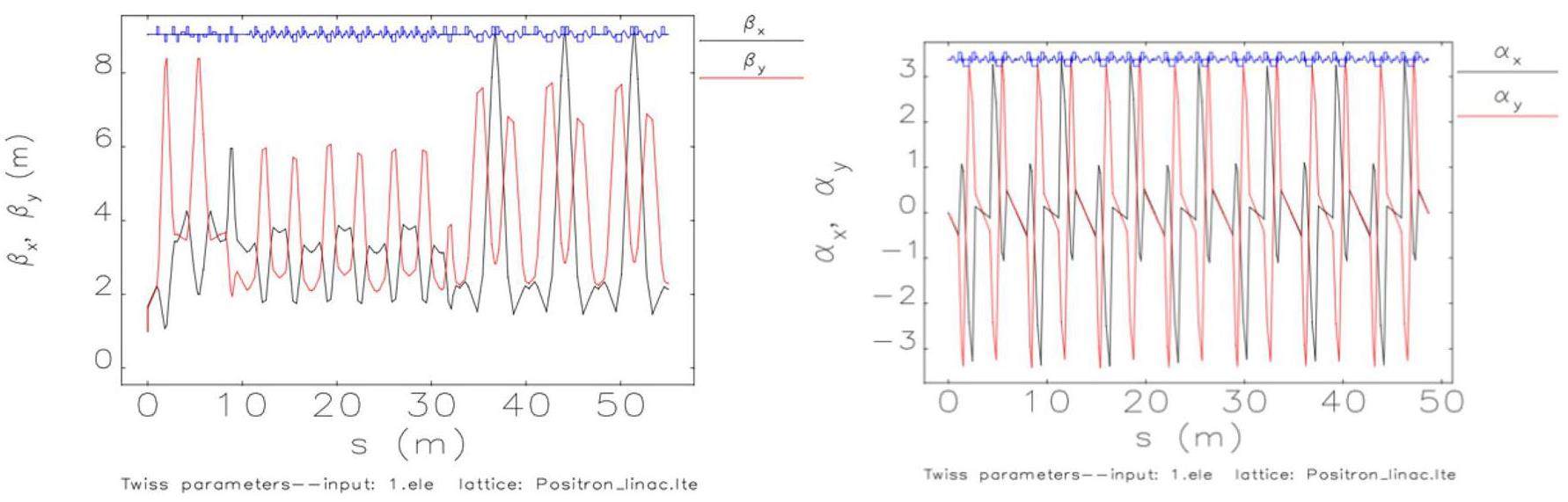

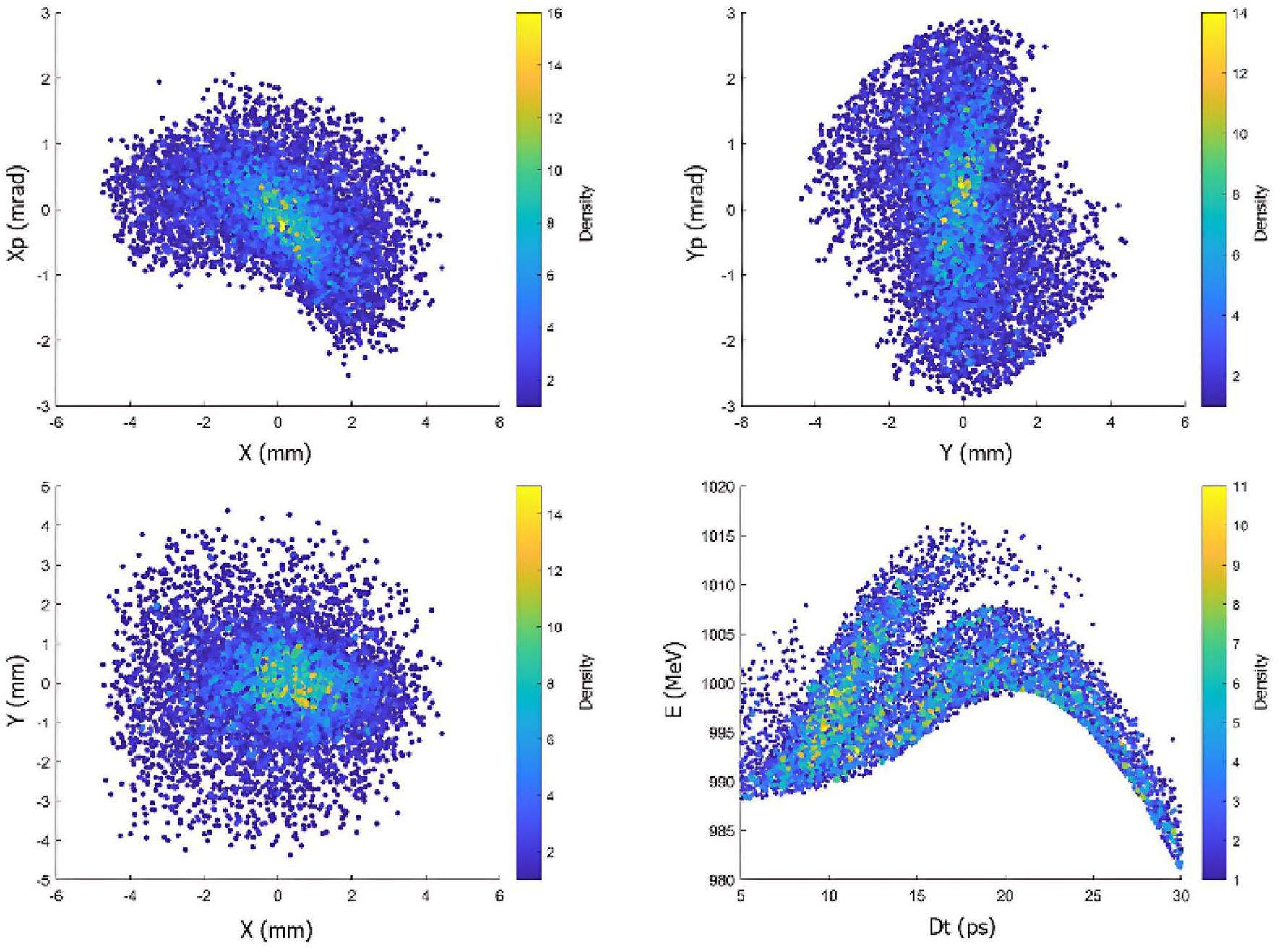

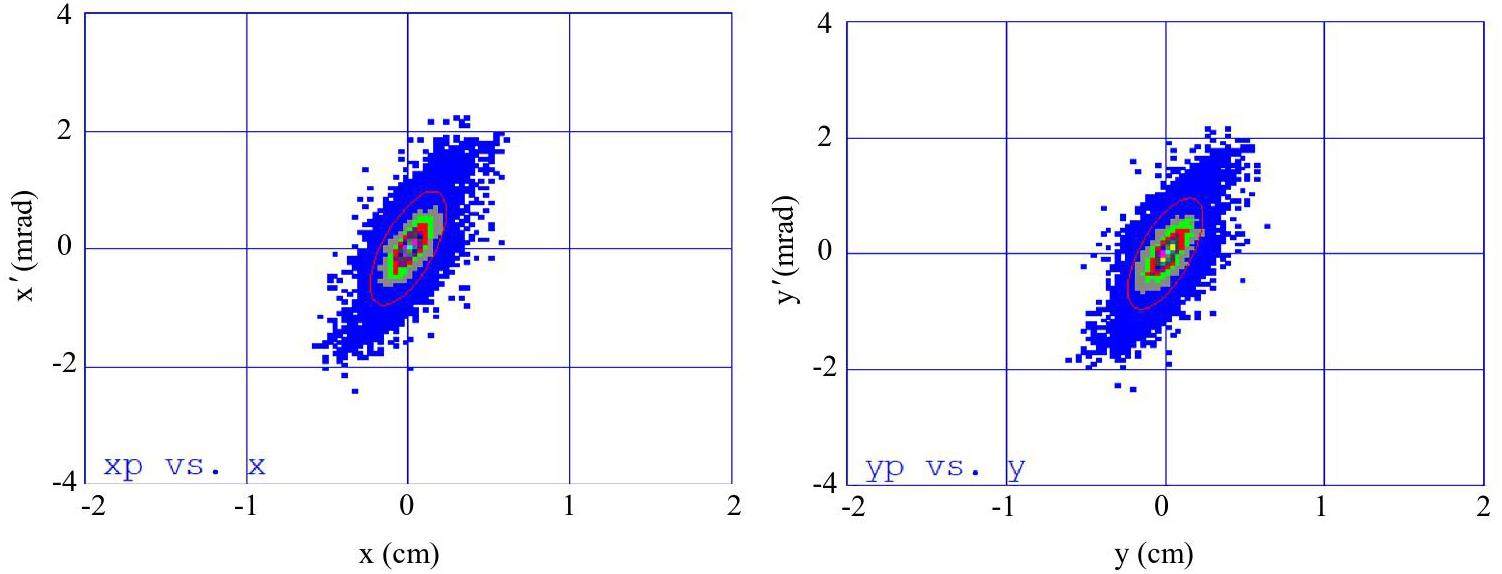

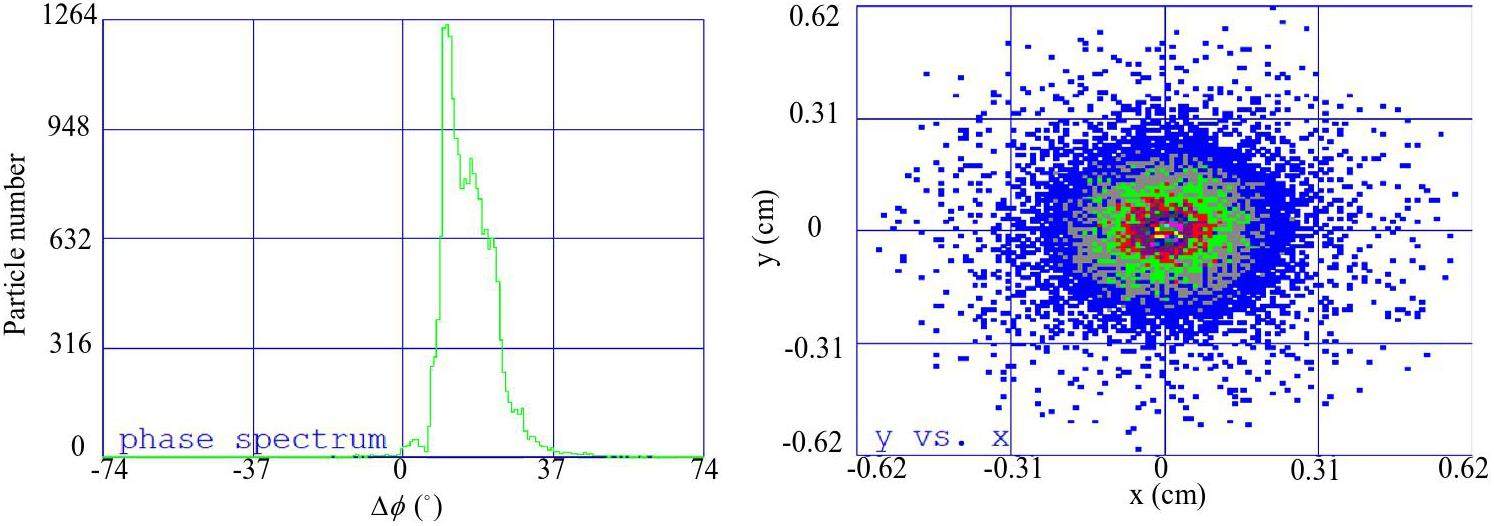

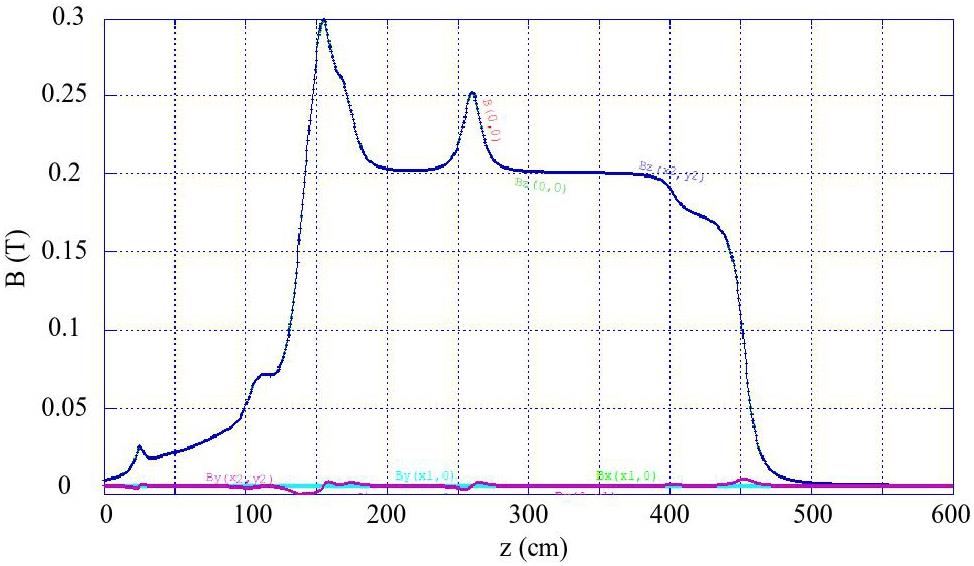

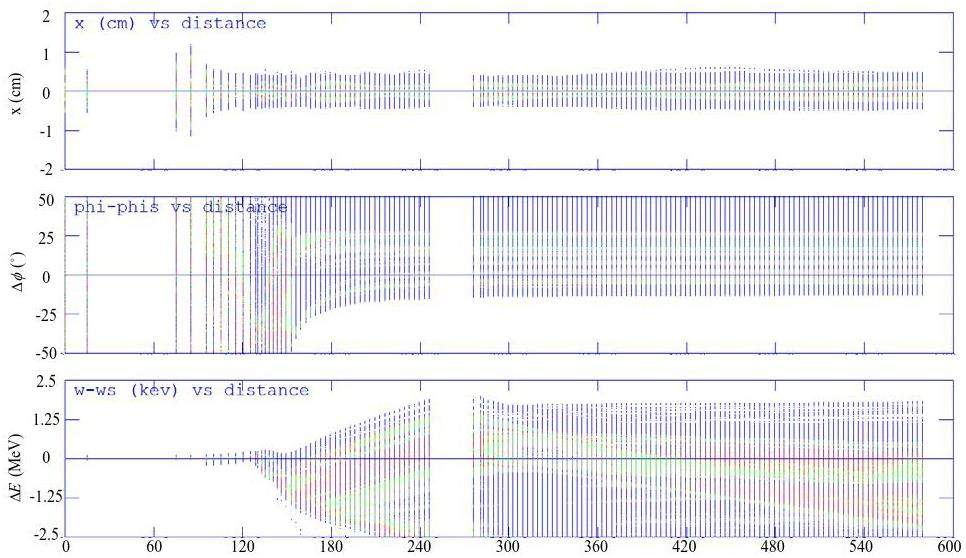

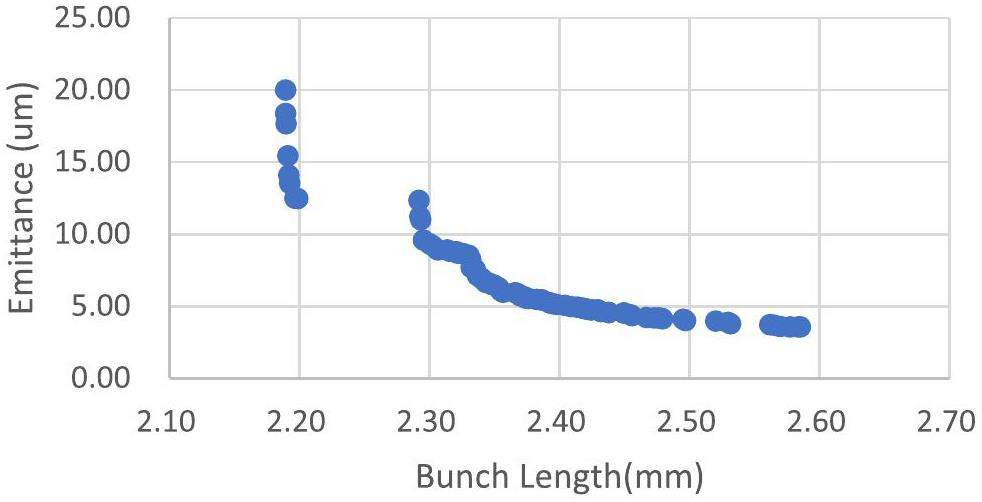

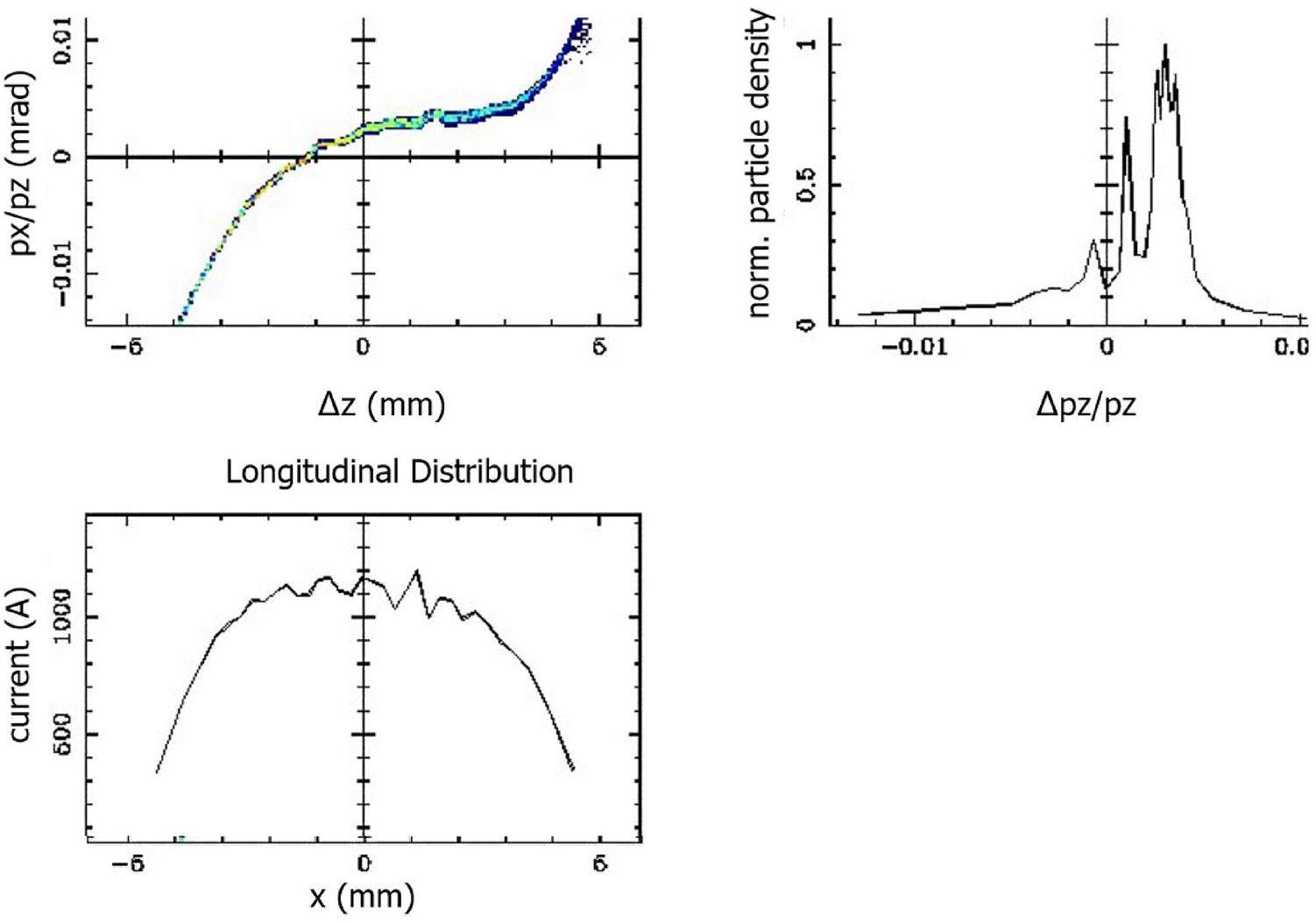

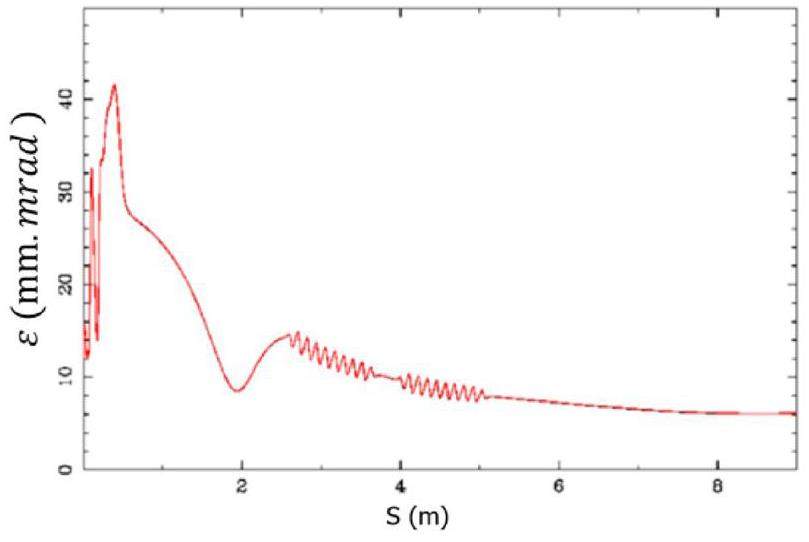

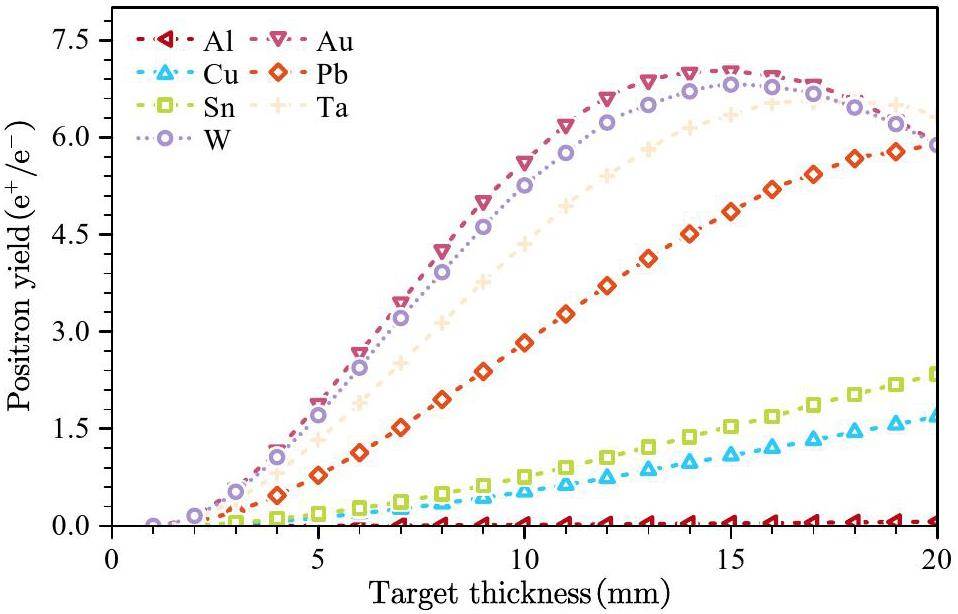

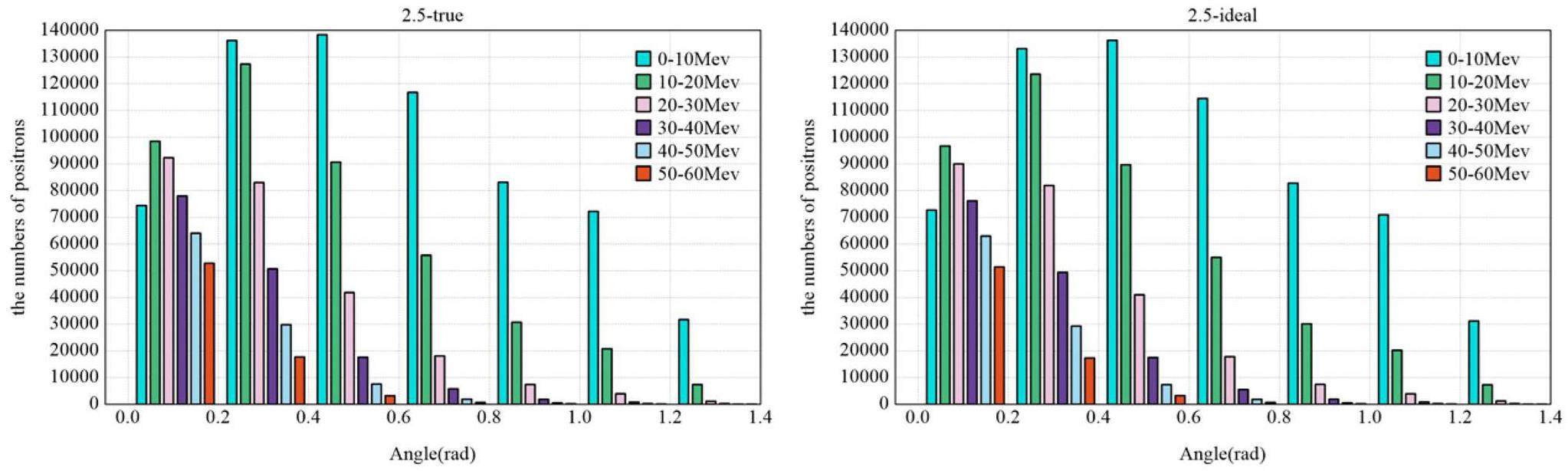

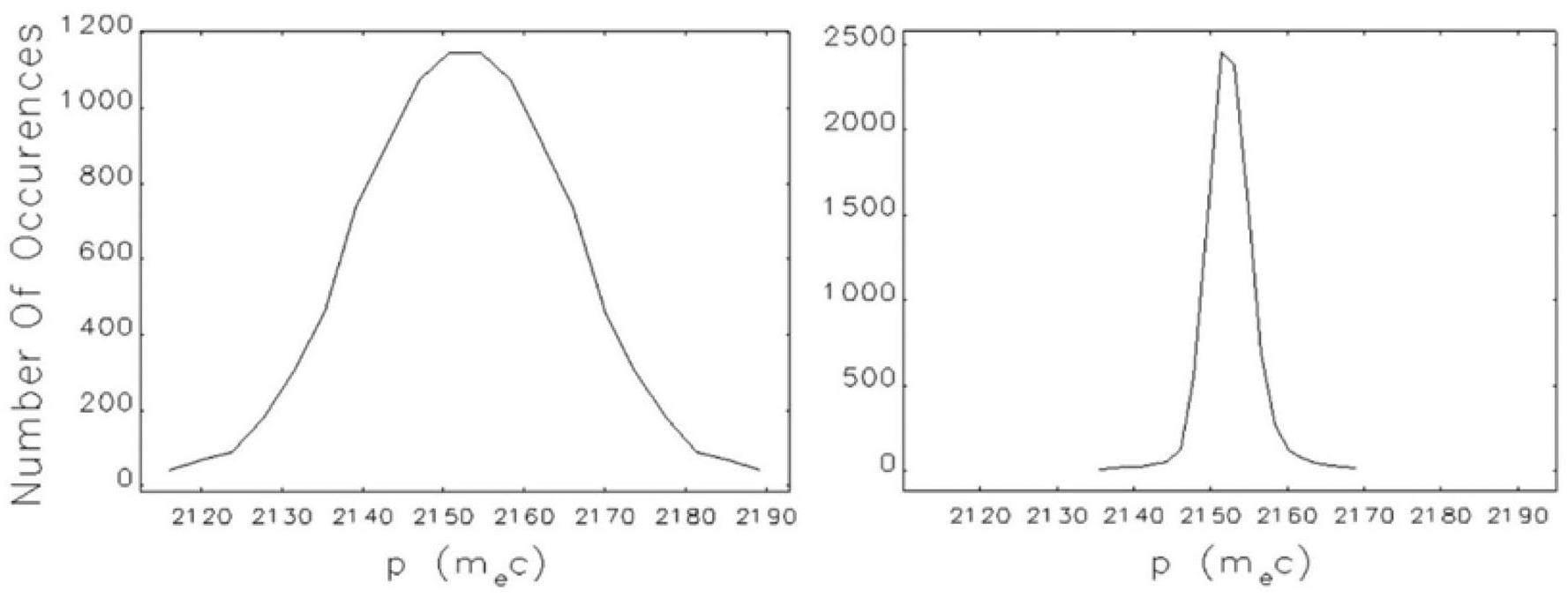

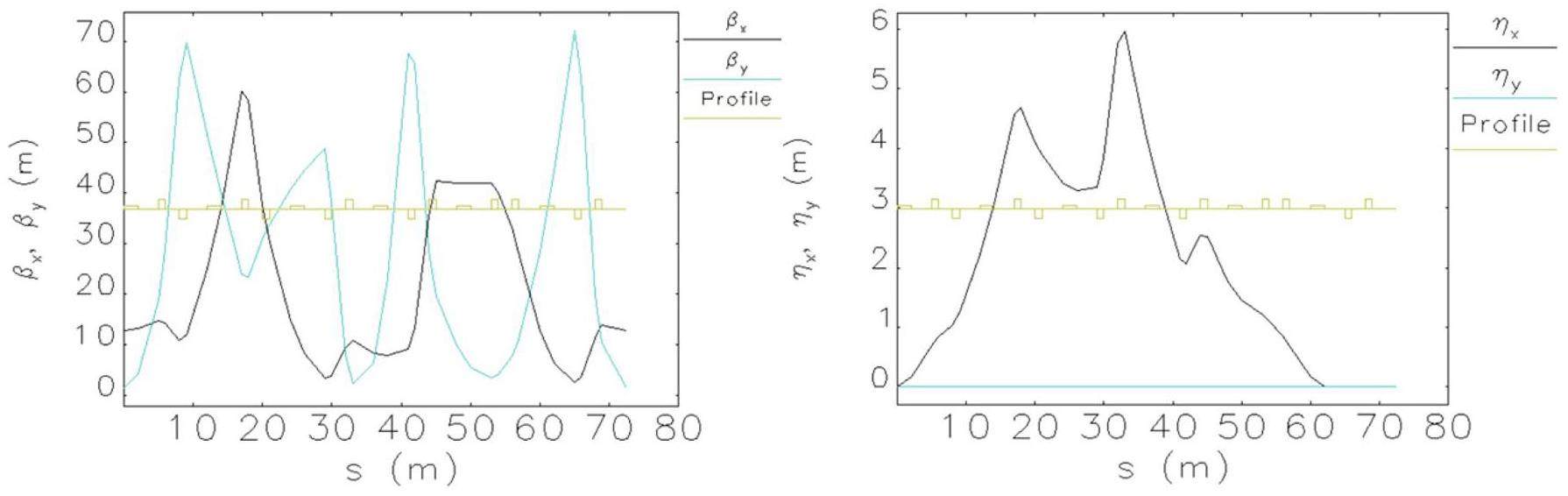

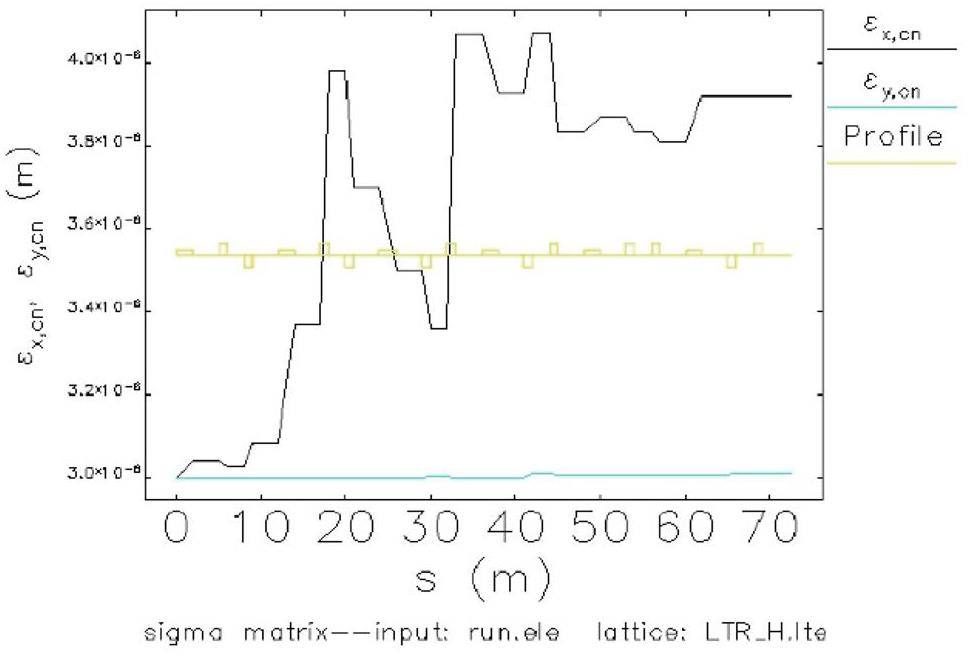

To accommodate the wide operational energy range (1–3.5 GeV) and short beam lifetime of the collider rings—particularly under the bunch swap-out injection scheme—the injector system must deliver electron and positron beams with the following characteristics: variable energy (1–3.5 GeV), high repetition rate (≈30 Hz), low emittance (<30 nm·rad), and high bunch charge (8.5 nC). Meeting these requirements poses significant challenges in the injector design. These challenges include how to optimize the linac design to minimize emittance growth and energy spread when accelerating high-charge electron bunches from a thermionic gun, how to design a positron production and accumulation chain—including target, capture optics, damping, and acceleration—to yield high-quality positron bunches with sufficient charge and low emittance, and how to suppress emittance degradation in beam transport lines to realize high-intensity electron and positron bunches during injection.

Key technologies

While most of the technical systems of the STCF accelerator will adopt mature and proven accelerator technologies wherever possible to ensure feasible and timely construction, several key technologies—though having a certain development base or being under development—remain immature and must be developed or advanced in significant undertakings to meet the facility’s performance goals and ensure technological advancement. The project team is actively organizing vigorous research and development (R&D) efforts in these areas, aiming for critical breakthroughs in the coming years to ensure the implementation of the engineering construction. In parallel, backup solutions to those key technologies are being prepared to guarantee the timely advancement of the construction project and compliance with final performance specifications, even if the R&D of the key technologies experiences delays or setbacks.

The key enabling technologies required for the STCF accelerator include:

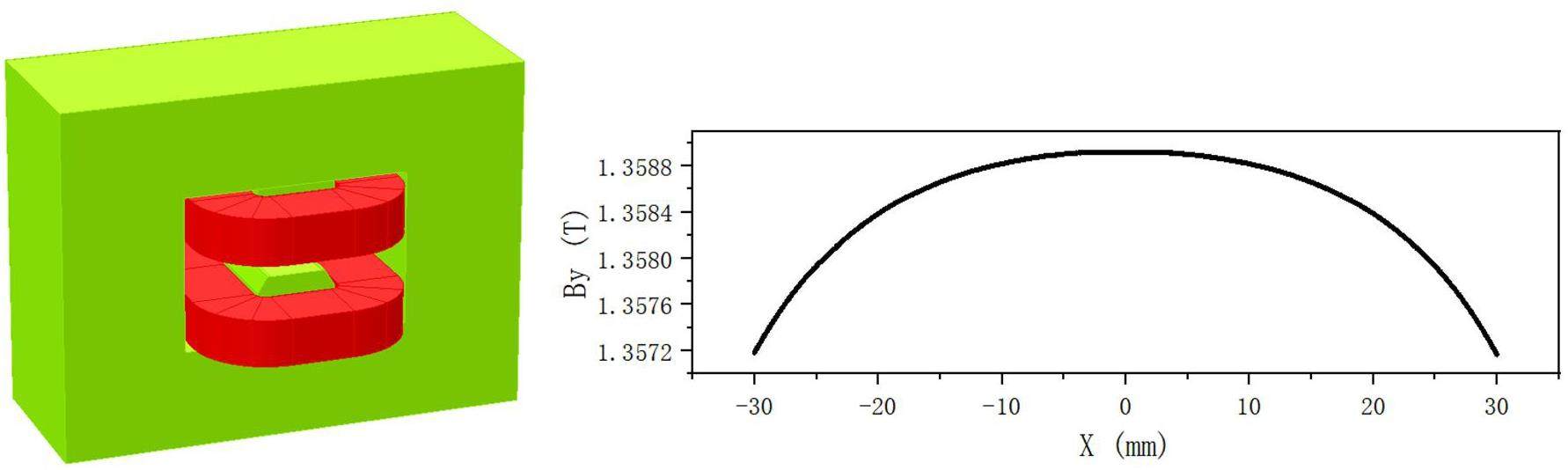

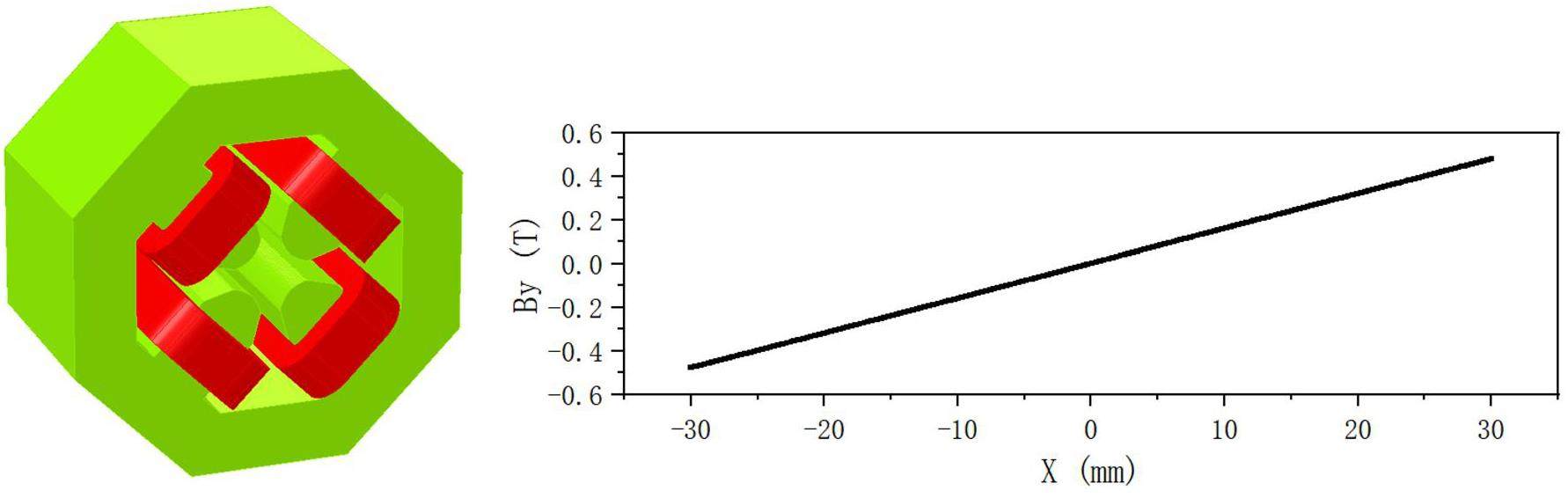

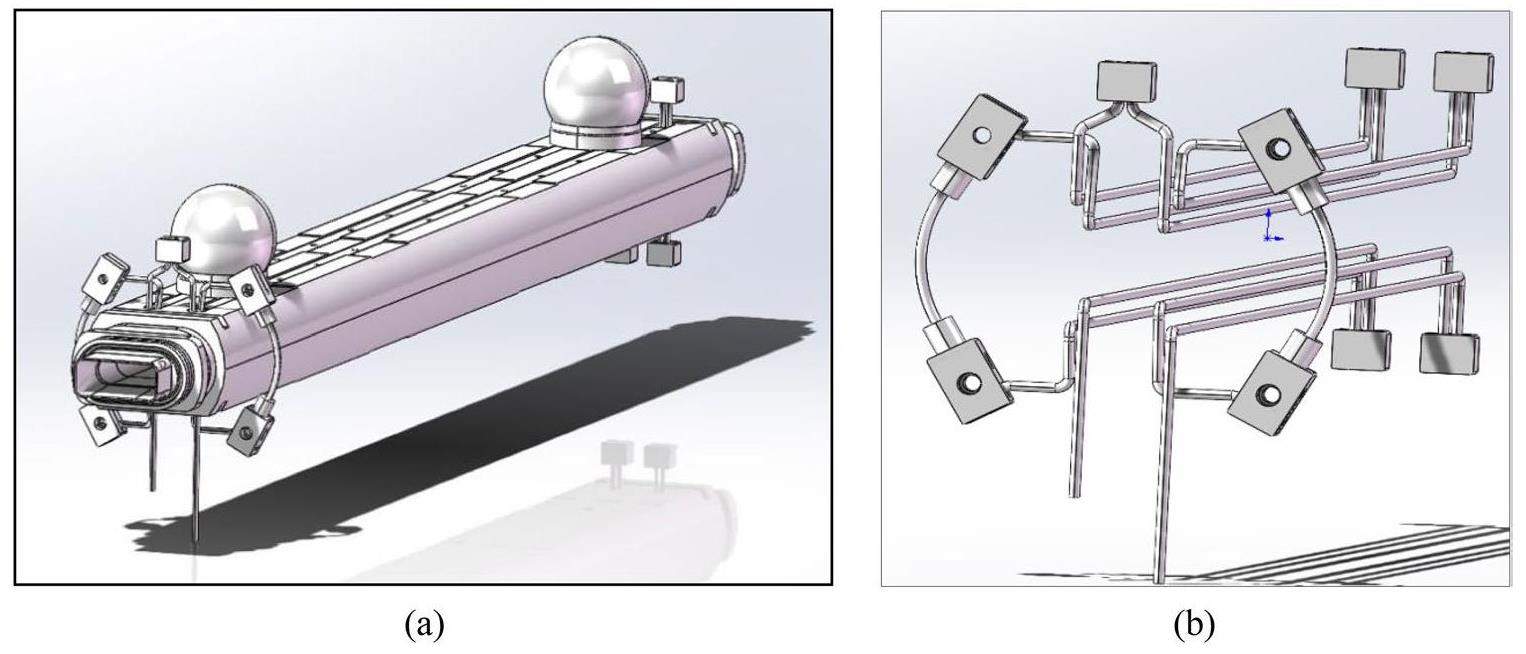

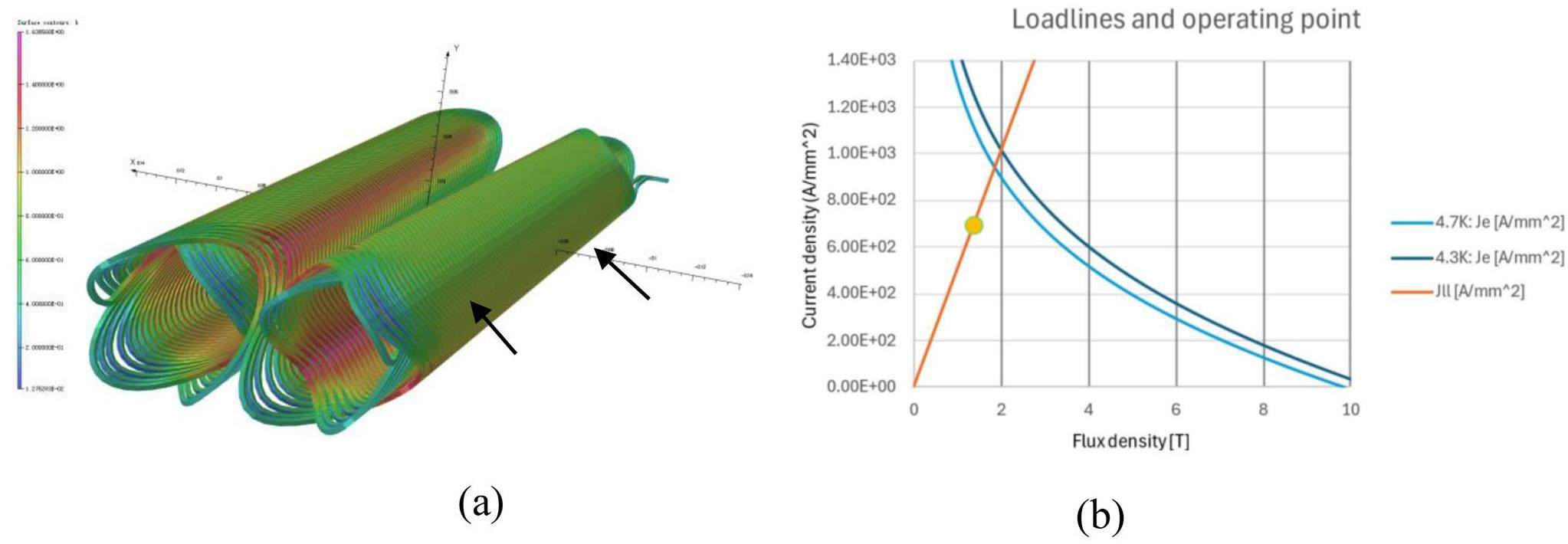

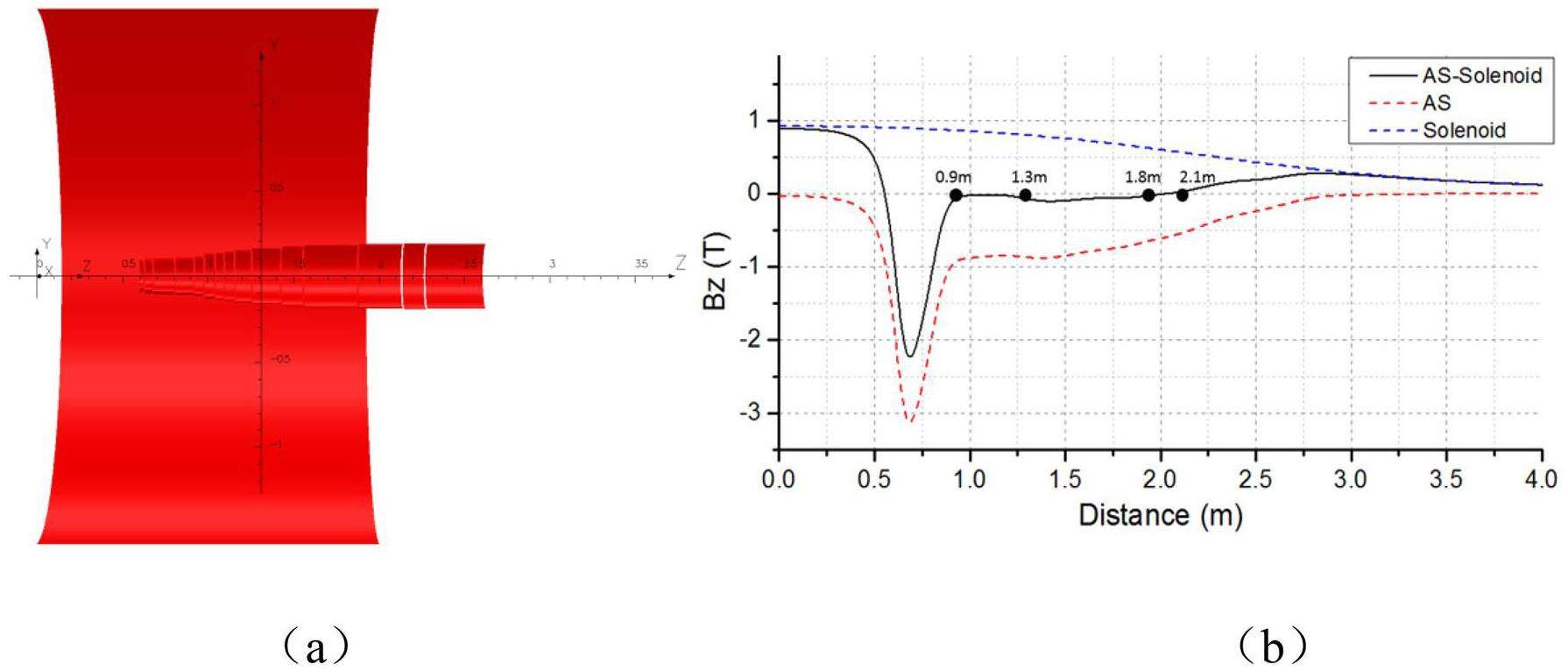

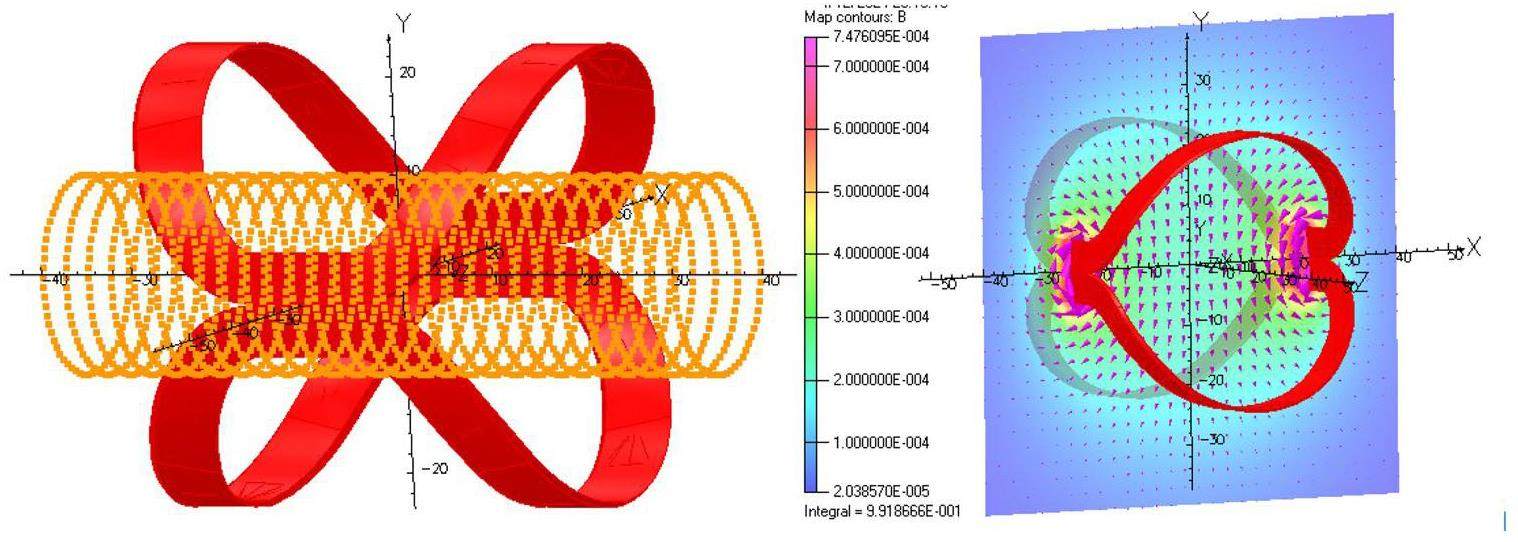

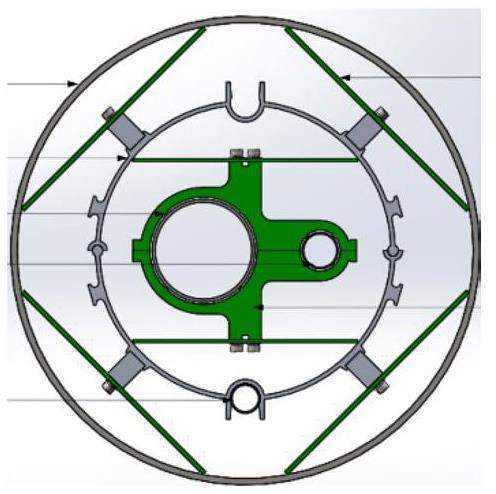

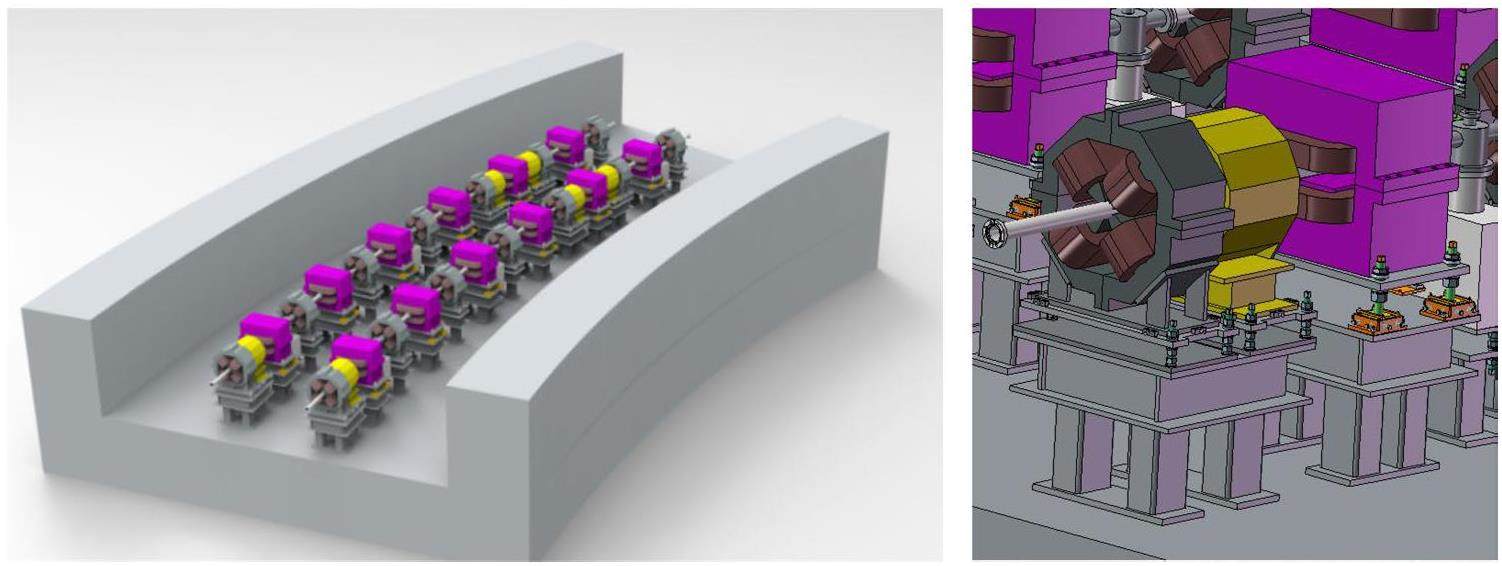

Twin-Aperture Superconducting Magnets for the IR: These include the final focus quadrupoles as well as integrated corrector coils, higher-order field coils, anti-solenoids, and compensation solenoids.

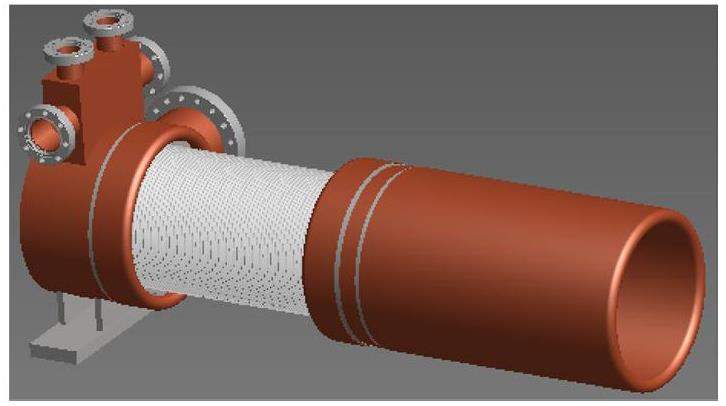

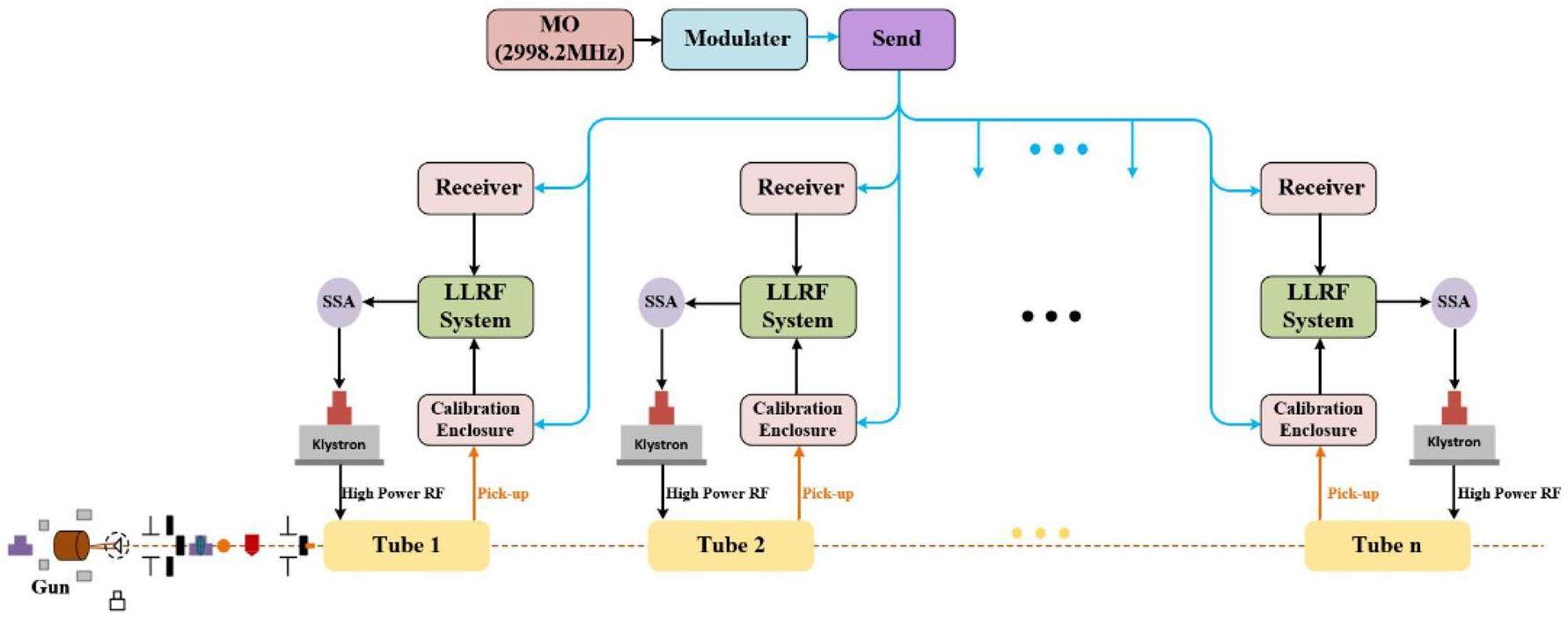

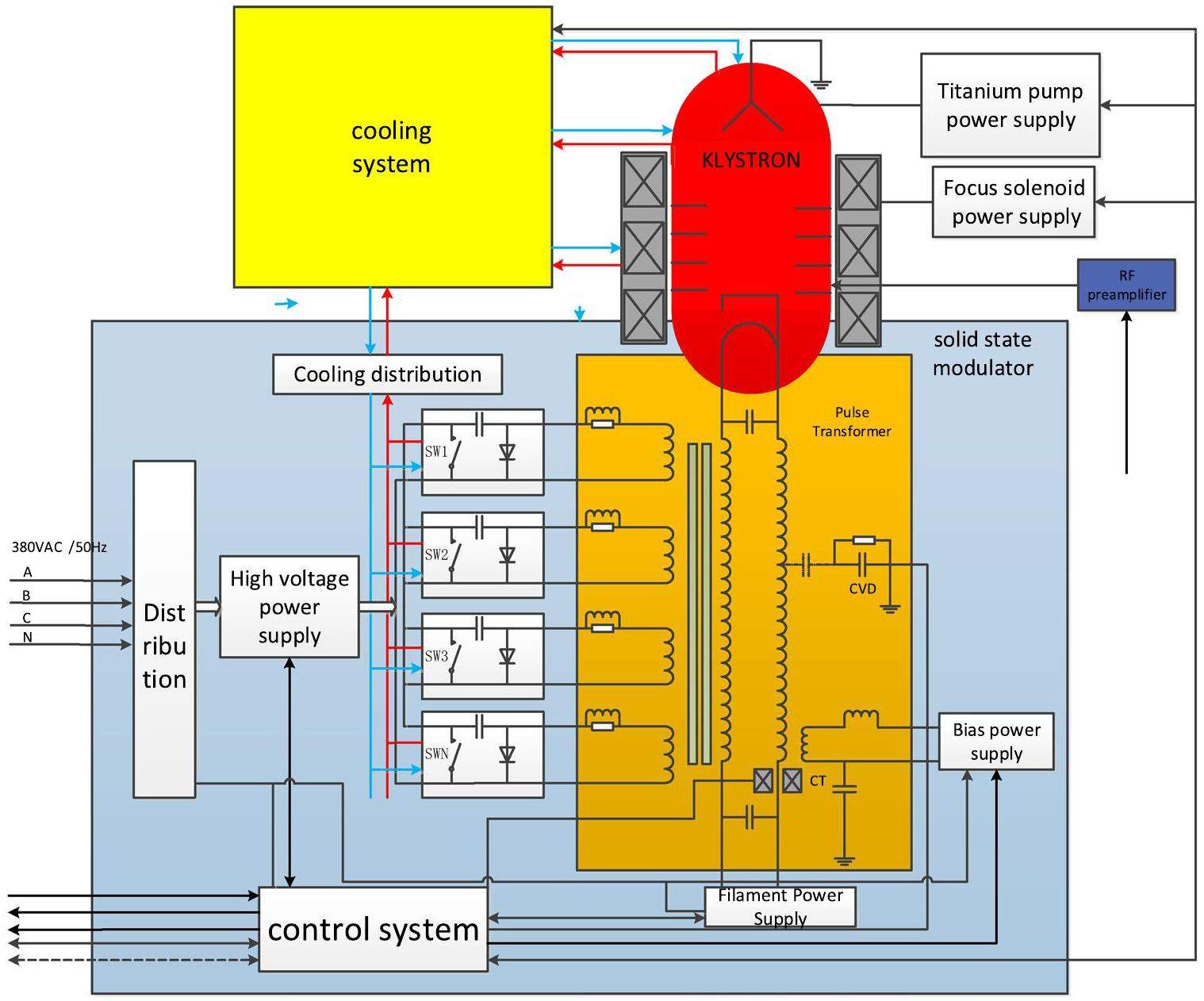

Collider Ring RF Systems: Room-temperature cavities designed to support high circulating currents (≈2 A), with deep higher-order mode (HOM) suppression, high-power RF couplers, and stable low-level RF (LLRF) controls.

Beam Diagnostics and Feedback Systems: Fast-response, low-noise feedback systems and high-precision 3D bunch profiling instrumentation.

Other Advanced Accelerator Technologies: Ultra-fast kicker magnets with pulse bottom widths smaller than 6 ns; ultra-high vacuum systems with low impedance, capable of operating under very intense synchrotron radiation; high bunch-charge (>8 nC) PC electron guns; high-power positron production targets; klystrons and accelerating structures operating at up to a 90 Hz repetition rate; and complex mechanical systems for the MDI (Machine–Detector Interface) region, etc.

Collider ring accelerator physics

Collision scheme and global parameters

The core objective of designing an electron–positron collider is to maximize luminosity. The luminosity, L, can be expressed as follows [1]:

According to the scientific objectives of the STCF [2], which demand a center-of-mass energy range of 2–7 GeV and a design luminosity not lower than 0.5 × 1035cm-2s-1 at the optimized energy point of 4 GeV, the STCF accelerator will adopt the most advanced third-generation design philosophy for circular e+e- colliders. Specifically, it will follow the double-ring scheme of second-generation colliders and incorporate a large crossing angle with the crab-waist collision scheme [3].

This collision scheme is characterized by a flat beam profile at the IP, with extreme vertical compression (on the order of hundreds of nanometers) and significant horizontal compression (on the order of tens of microns). Due to the large crossing angle, the overlap region of the two bunches at the IP is very small, which permits the use of relatively long bunch lengths without experiencing severe luminosity degradation from the hourglass effect.

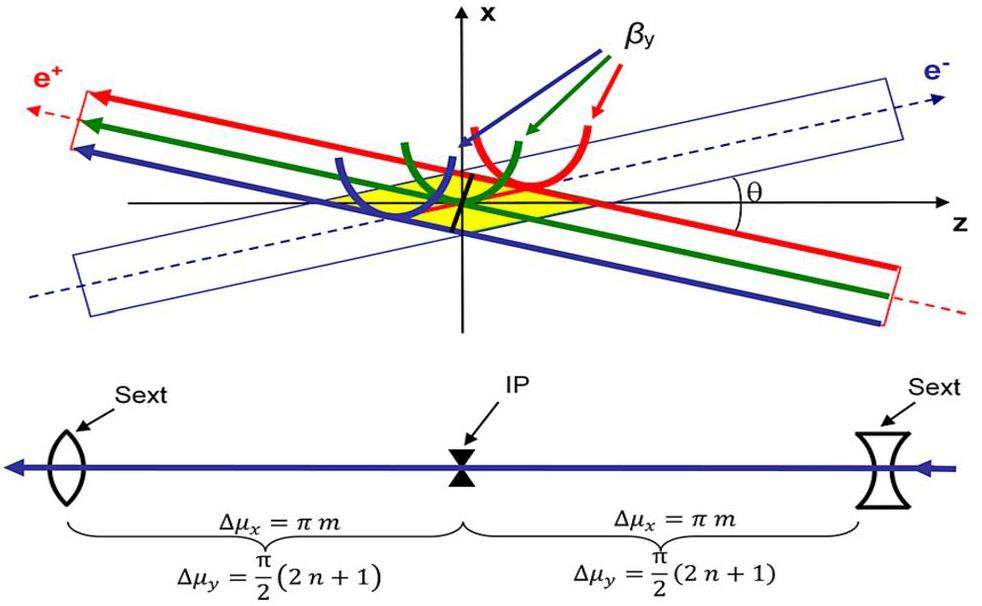

To mitigate the transverse and transverse-longitudinal coupling instabilities induced by the large crossing angle, crab sextuples are placed at specific phase advance locations on either side of the IP. These magnets couple the horizontal and vertical motions of the bunches such that the vertical focus of particles becomes correlated with their horizontal position, and all vertical foci fall along the optical axis of the opposing bunch—this is the so-called crab-waist collision scheme. Figure 2 illustrates the principle of the crab-waist collision scheme [3].

In addition, further measures to improve the luminosity of the STCF include achieving an ultra-small

The crab-waist collision scheme requires strong coupling between the X/Y directions of the bunches near the IP via crab sextupoles. Combined with strong focusing at the IP, this significantly reduces the dynamic and momentum apertures of the collider rings. In addition to instigating serious beam injection challenges, it can cause a very short Touschek lifetime under high bunch currents and low emittances—for example, less than 300 s, which is significantly shorter than that of other circular electron accelerators. Such a short Touschek lifetime increases the difficulty of designing and constructing the injector, as it would require significantly higher injection repetition rates, and causes severe beam loss during injection, which in turn negatively impacts the experimental background. Balancing high-luminosity collisions with beam dynamics, lifetime, and stability is one of the major challenges of the physical design of the collider rings [4]. The physical design of the STCF collider rings must balance design goals and these critical parameters.

Based on the analysis of the collision scheme proposed for the STCF, the selection of key parameters for the collider rings must be guided by detailed physics studies and iterative coordination with major hardware system designs while referencing results from other third-generation e+e- colliders and synchrotron light sources. Factors that must be considered for several key parameter choices are summarized below:

· Beam energy range: 1.0–3.5 GeV, with an optimized energy point at 2 GeV, as determined by the overarching scientific goals of the project.

· Luminosity: ≥ 0.5 × 1035cm-2s-1 @ 2 GeV beam energy, also defined by the project’s scientific objectives. At the lower and upper ends of the energy range, lower luminosity is permitted but must not decrease by more than one order of magnitude.

· Ring circumference: 800–1000 m based on international experience and with future expansion allowances. A longer circumference provides space for an ideal IR design and accommodates components that occupy long straight sections—such as damping wigglers (DWs), collimators, injection/extraction elements, and RF cavities. It also reserves space for future upgrades involving polarized beams (e.g., spin rotators or Siberian snakes (SSs)). However, excessively increasing the circumference should be avoided to contain construction costs.

· Circulating current: ≈2 A @ 2 GeV based on international experience and preliminary STCF studies. High current is essential for achieving high luminosity; however, further increases will severely shorten the Touschek lifetime. At lower energies, Touschek effects are more pronounced, and moderate reductions in beam current and luminosity are acceptable. At higher energies, synchrotron radiation power may impose additional constraints on the beam current.

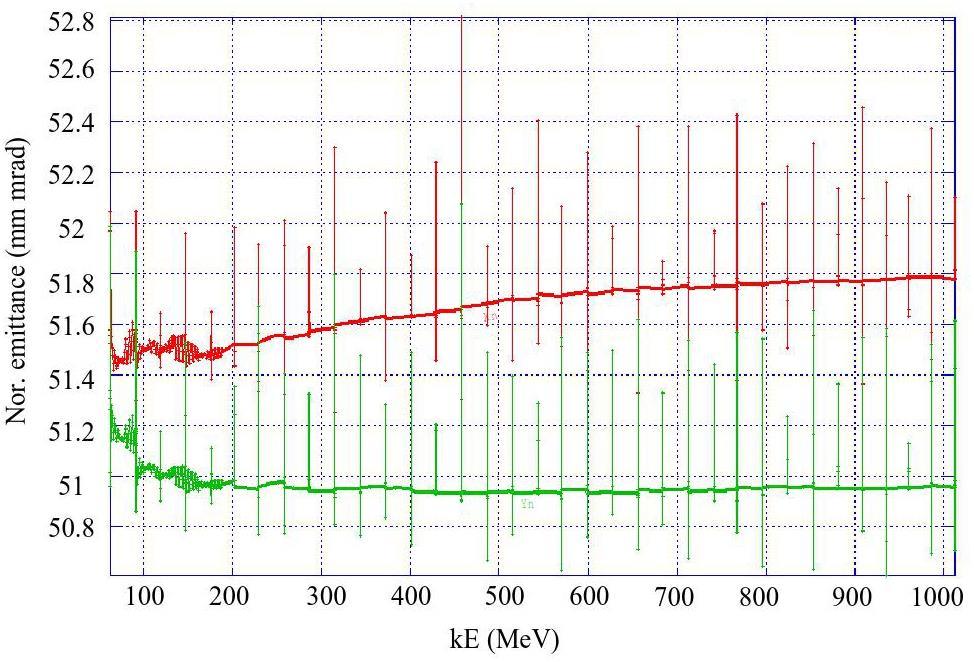

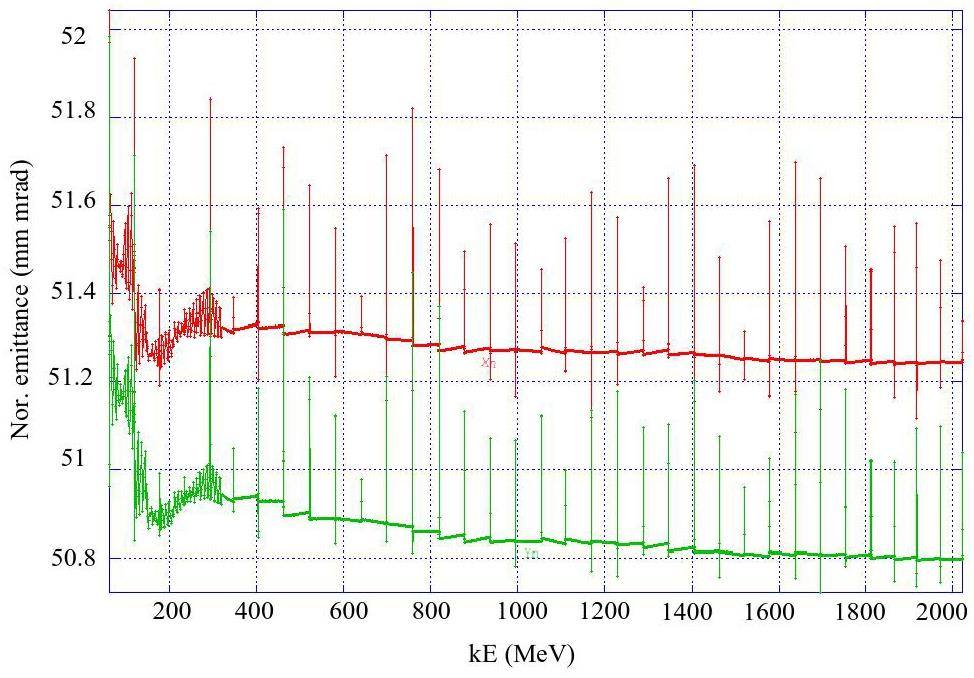

·

· Transverse emittance: Horizontal emittance is approximately 5 nm·rad at 2 GeV, which is comparable to third-generation synchrotron light sources. The transverse coupling is limited to 1%, corresponding to a vertical emittance of approximately 50 pm·rad, sufficient to achieve a vertical beam size of approximately 100 nm at the IP. Emittance is allowed to vary within a reasonable range at other energies (lower at low energies, higher at high energies). At 1 GeV and 1.5 GeV, the coupling ratio remains at 1%; at 3.5 GeV, it is set to 0.5%. At low energy, vertical dispersion can be increased to boost vertical emittance and thereby improve Touschek lifetime.

As the optimization of the collider ring physics design progresses, the overall parameter table for the collider rings will also be periodically updated. Table 1 shows the latest version of the current global design parameters.

| Parameter | Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beam energy, E (GeV) | 2 | 1 | 1.5 | 3.5 |

| Circumference, C (m) | 860.321 | |||

| Crossing angle, 2θ (mrad) | 60 | |||

| L* (m) | 0.9 | |||

| Relativistic factor, γ | 3913.9 | 1956.9 | 2935.4 | 6849.3 |

| Revolution period, T0 (μs) | 2.87 | |||

| Revolution frequency, f0 (kHz) | 348.47 | |||

| Ratio, |

1% | 15% | 10% | 0.5% |

| Horizontal emittance (SR/DW, IBS), εx (nm) | 8.79/4.63 | 2.20/5.42 | 4.94/3.82 | 26.9/26.91 |

| Vertical emittance (SR/DW, IBS), εy (pm) | 87.9/46.3 | 330/813 | 494/382 | 134.5/134.55 |

| β functions at IP, βx/βy (mm) | 60/0.8 | |||

| Beam size at IP, σx/σy (μm) | 16.67/0.19 | 18.03/0.81 | 15.14/0.55 | 40.18/0.33 |

| Betatron tunes, νx/νy | 30.54/34.58 | 30.555/34.57 | ||

| Momentum compaction factor, αp (×10-4) | 13.49 | 12.63 | 13.24 | 13.73 |

| Energy spread (SR/DW, IBS), σe (×10-4) | 5.72/7.82 | 2.86/6.18 | 4.29/6.93 | 10.01/10.02 |

| Beam current, I (A) | 2 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 2 |

| Bunch filling factor | 48% | |||

| Number of bunches, nb | 688 | |||

| Bunch spacing, τb (ns) | 4 | |||

| Single bunch current, Ib (mA) | 2.91 | 1.6 | 2.47 | 2.91 |

| Particles per bunch, Nb (×1010) | 5.20 | 2.86 | 4.42 | 5.20 |

| Total particles per beam (×1013) | 3.58 | 1.97 | 3.05 | 3.58 |

| Charge per bunch (nC) | 8.34 | 4.59 | 7.09 | 8.34 |

| Energy loss per turn (SR/Total), U0_sr (keV) | 159/543 | 10/106 | 50/267 | 1494/1494 |

| Synchrotron radiation power loss per beam (SR/Total), PSR (MW) | 0.32/1.09 | 0.01/0.12 | 0.085/0.453 | 2.988/2.988 |

| Damping times, τx/τy/τz (ms) | 21/21/11 | 54/54/27 | 32/32/16 | 14/14/6.7 |

| RF Frequency, fRF (MHz) | 499.7 | |||

| Harmonic number, h | 1434 | |||

| RF voltage, VRF (MV) | 2.5 | 0.75 | 1.2 | 6 |

| Longitudinal phase, Фs (deg) | 167 | 172 | 167 | 166 |

| Synchrotron tune, νz | 0.0194 | 0.0146 | 0.0154 | 0.0228 |

| Natural bunch length, σz (mm) | 7.21 | 6.62 | 7.89 | 8.26 |

| Bunch length (0.1 Ω, IBS), σz_ibs (mm) | 8.7 | 9.46 | 10.01 | 8.79 |

| RF energy acceptance, (ΔE/E)max (%) | 1.68 | 1.44 | 1.35 | 1.88 |

| Piwinski angle, ФPiw (rad) | 15.66 | 15.74 | 19.84 | 6.56 |

| Beam–beam parameters, ξx/ξy | 0.005/0.095 | 0.005/0.023 | 0.004/0.033 | 0.003/0.032 |

| Hourglass factor, Fh | 0.915 | 0.905 | 0.927 | 0.750 |

| Luminosity, L (cm-2s-1) | 9.42×1034 | 6.19×1033 | 2.09×1034 | 4.48×1034 |

| Touschek lifetime (SAD/Elegant) (s) | 252/304 | 195/264 | 215/294 | 5400/3479 |

Lattice design

Baseline scheme (Two-fold symmetry)

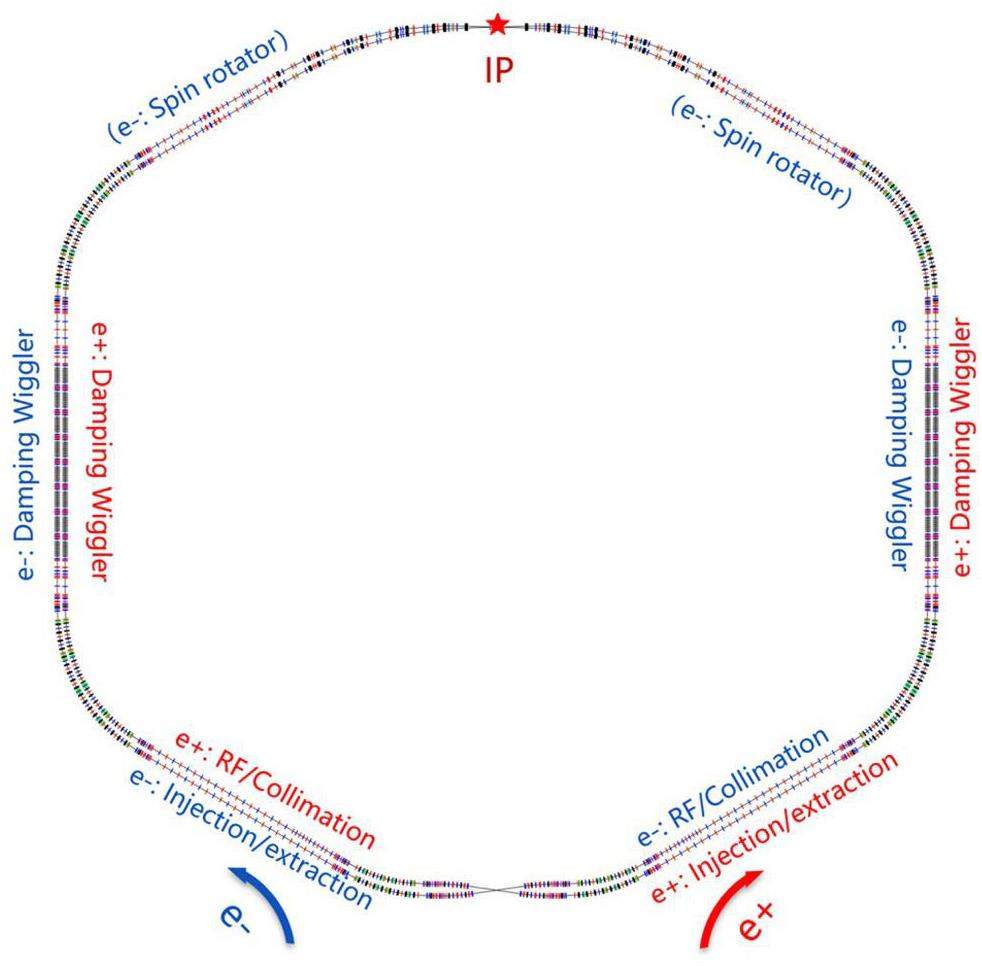

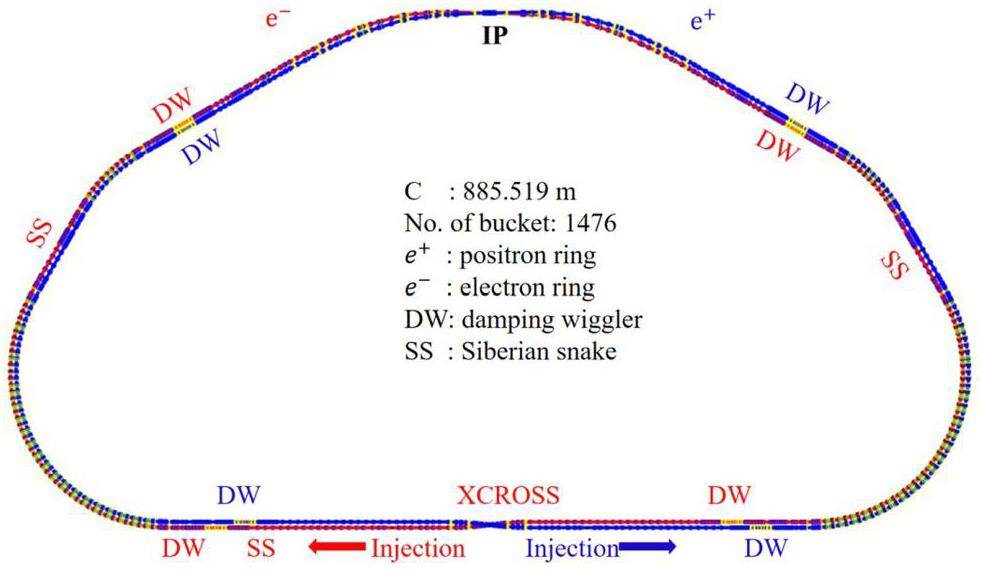

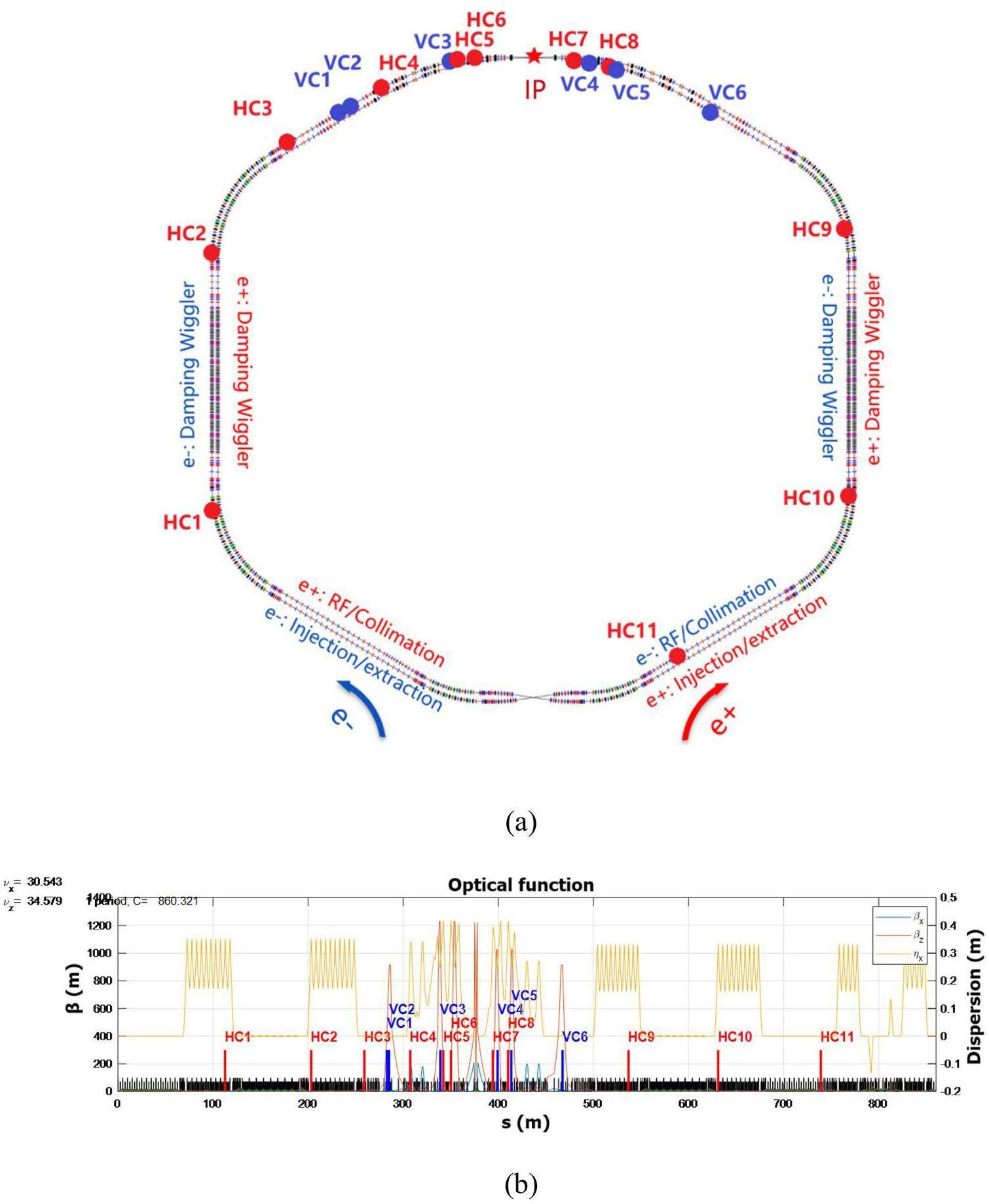

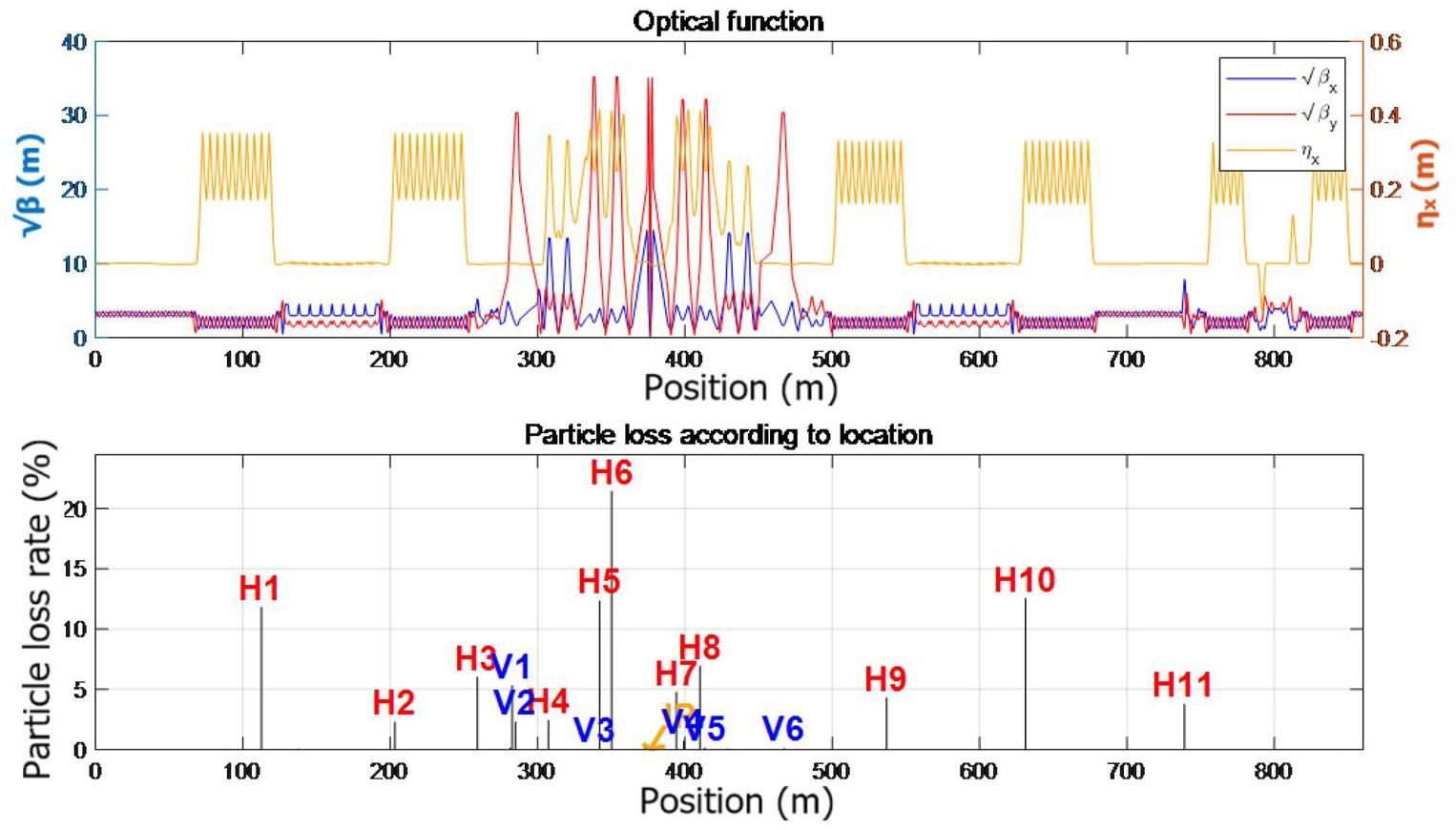

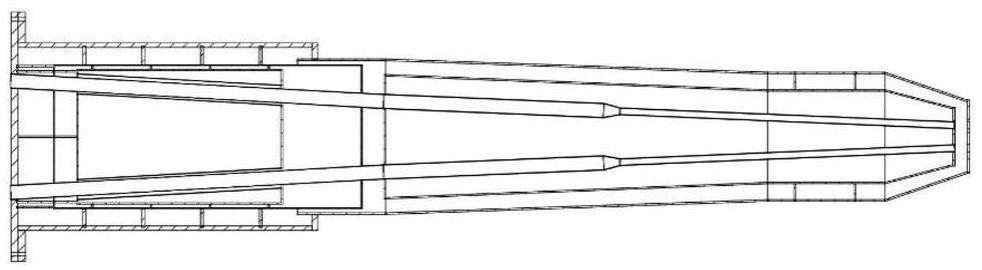

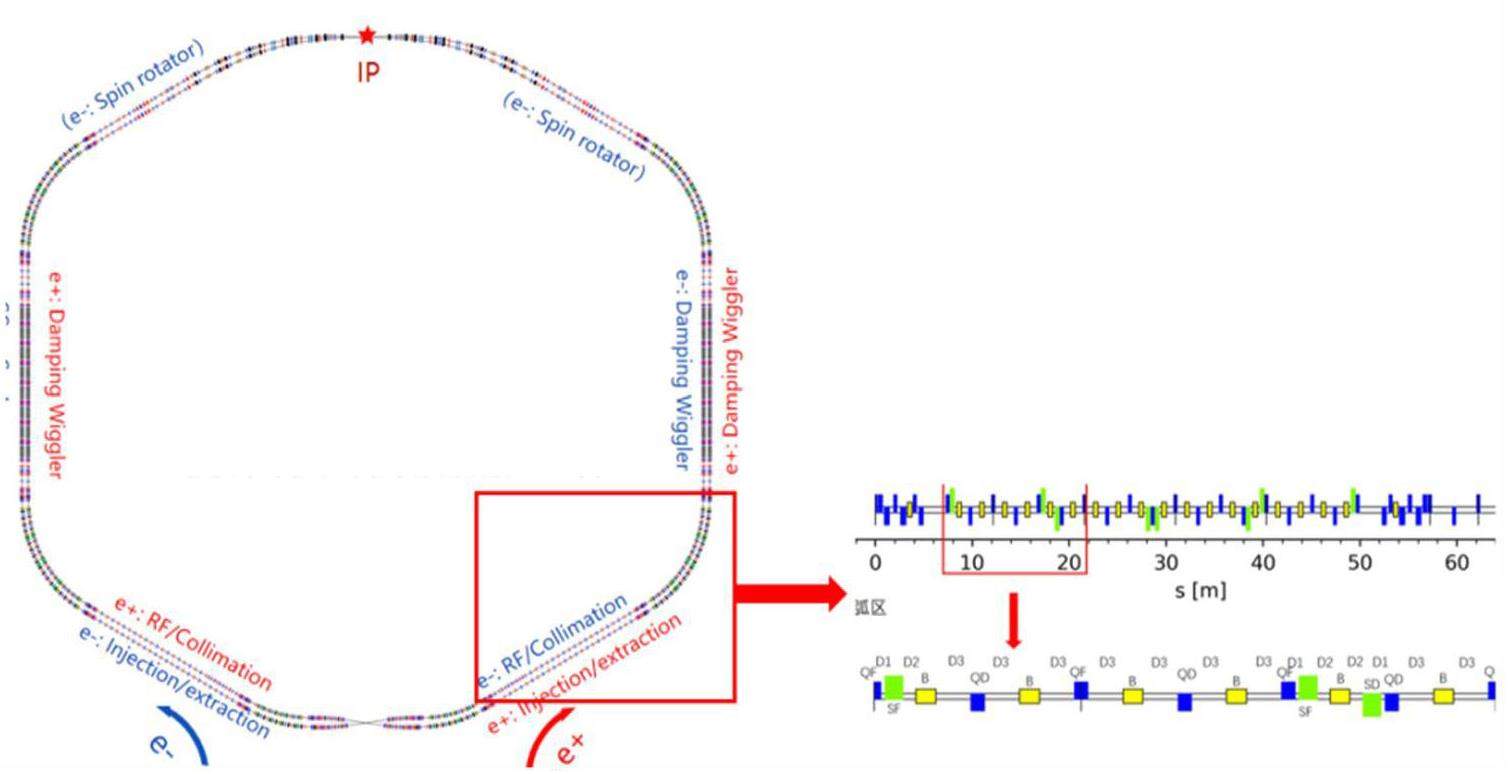

The STCF collider rings adopt a double-ring layout, consisting of an electron ring and a positron ring. Both rings lie in the same horizontal plane and intersect at the IP in the collision region and the crossing point in the region opposite the IP. The layout is symmetric along the line connecting these two points. Each collider ring features a two-fold symmetric structure. Owing to the crossing geometry of the double-ring configuration, the drift sections in the arc regions on opposite sides of the same ring differ slightly in length, forming inner and outer rings with an approximate spacing of 2 m. Space is reserved on both sides of the IR for the future installation of spin rotators to enable beam polarization upgrades.

Each ring consists of one collision region, four large arc sections (each bending by 60°), two small arc sections (each bending by 30°), one crossing region, and several straight sections. The straight sections serve different functions, including beam injection and extraction, housing DWs, beam collimation, accommodating RF cavities, and matching the working point. The total circumference of the ring is 860.321 m.

The main features of this lattice design include:

· A symmetric lattice layout that preserves the option of upgrading to a second IP;

· Flexibility in the type and length of DWs—currently adopting a well-established room-temperature DW scheme, with adjustments in the DW section not affecting the rest of the layout;

· A relatively small injection deflection angle where both electron and positron beams require a 60° bend to enter the collider rings;

· Reserved space for future upgrades, such as spin rotators required in potential beam polarization;

· A medium-scale arc section with a maximum arc bending of 60°, which improves local chromaticity correction and allows for the better optimization of the dynamic and momentum apertures.

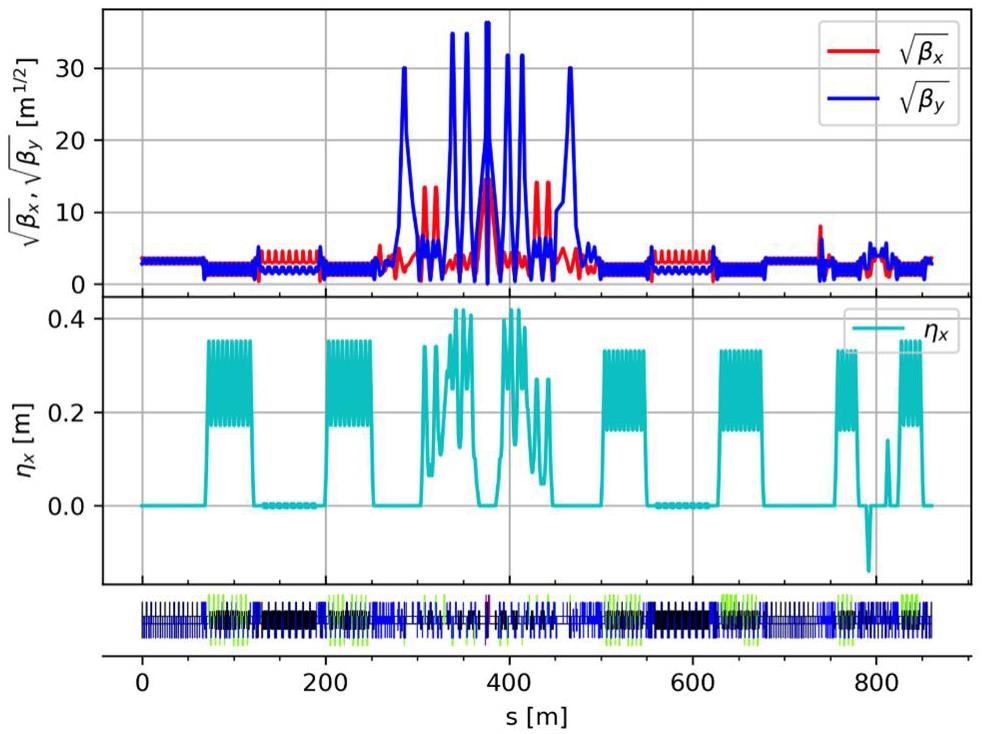

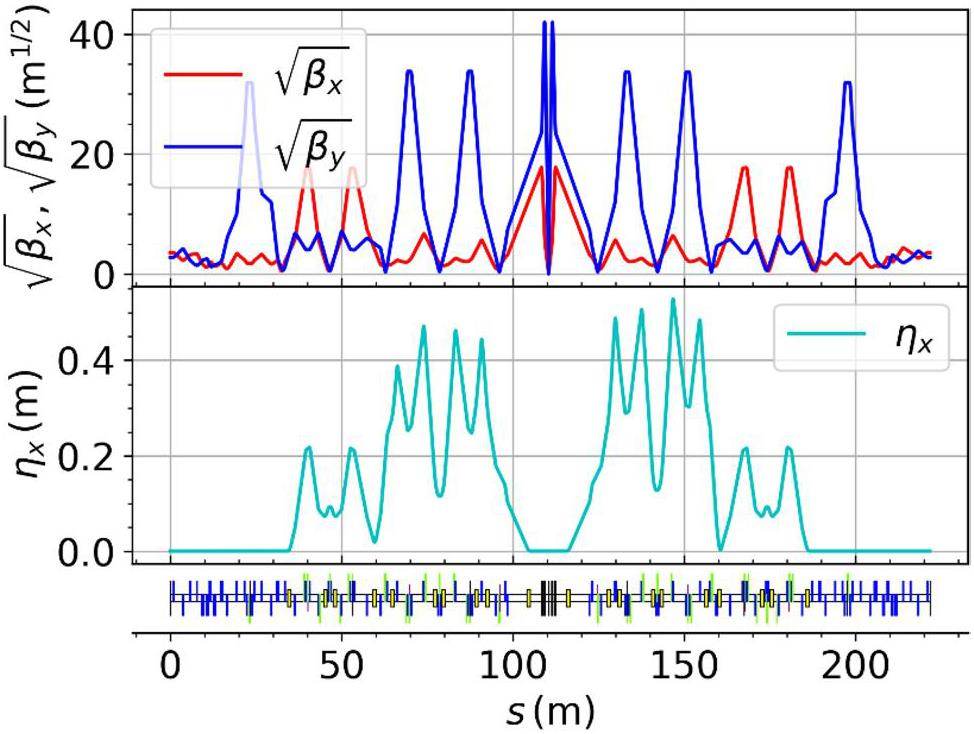

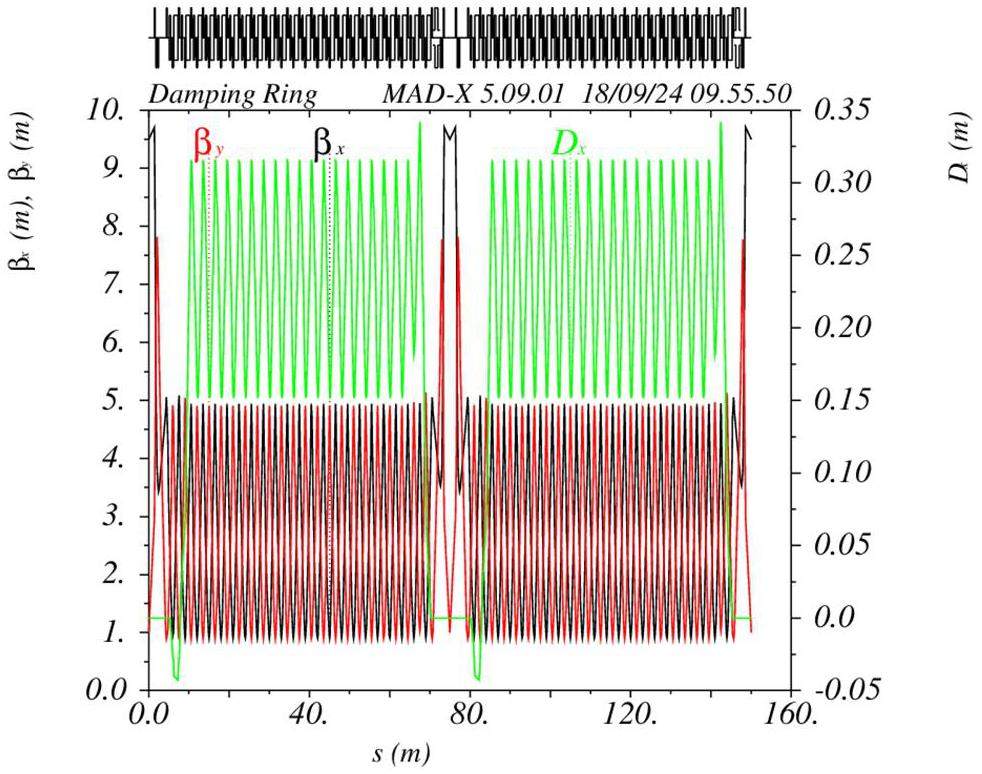

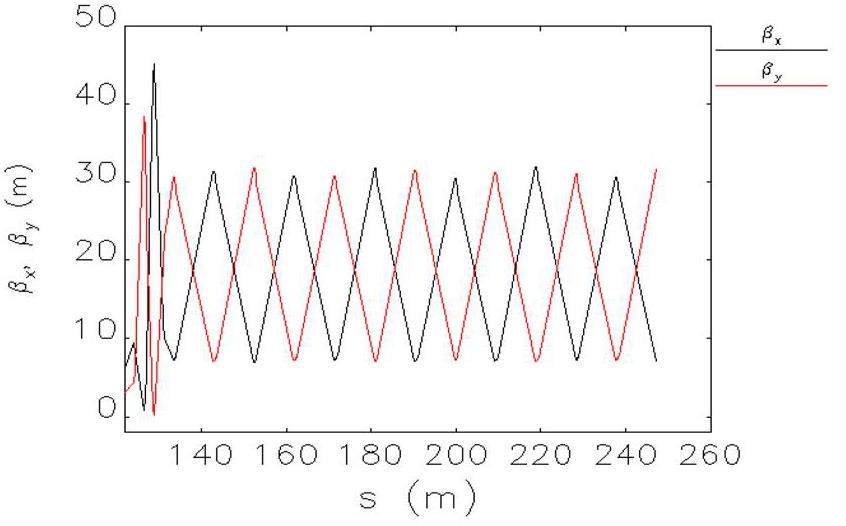

Figure 3 shows the layout of the collider rings, and Fig. 4 presents the optical functions. This section introduces the optical design of the arcs, straight sections, and crossing region in the two-fold symmetric lattice; the design of the IR optics is presented in Sect. 2.2.3.

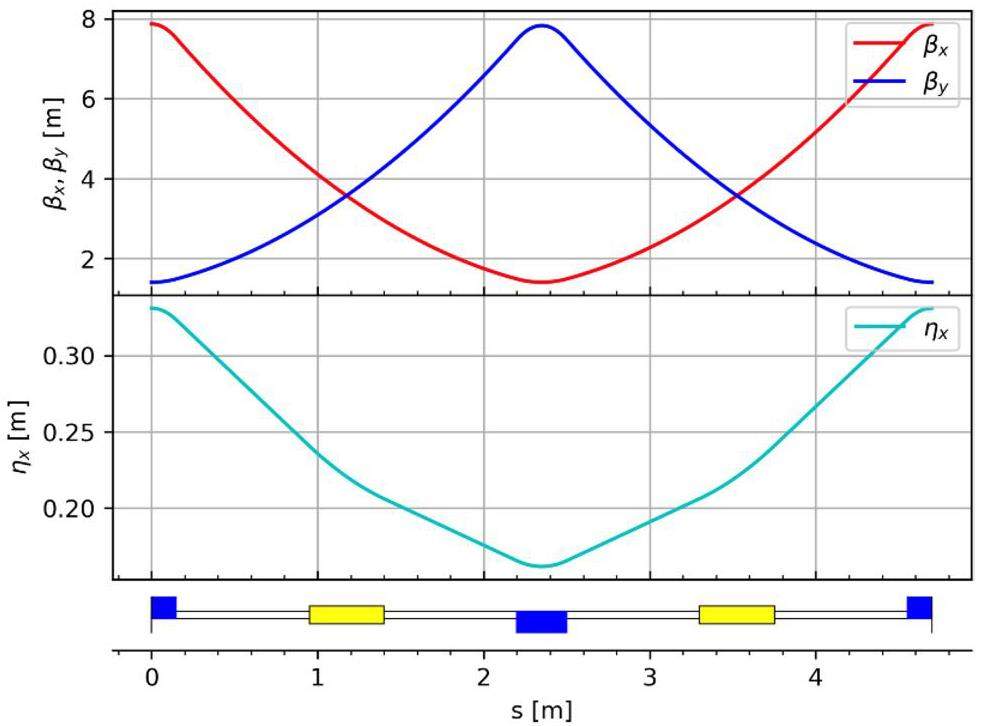

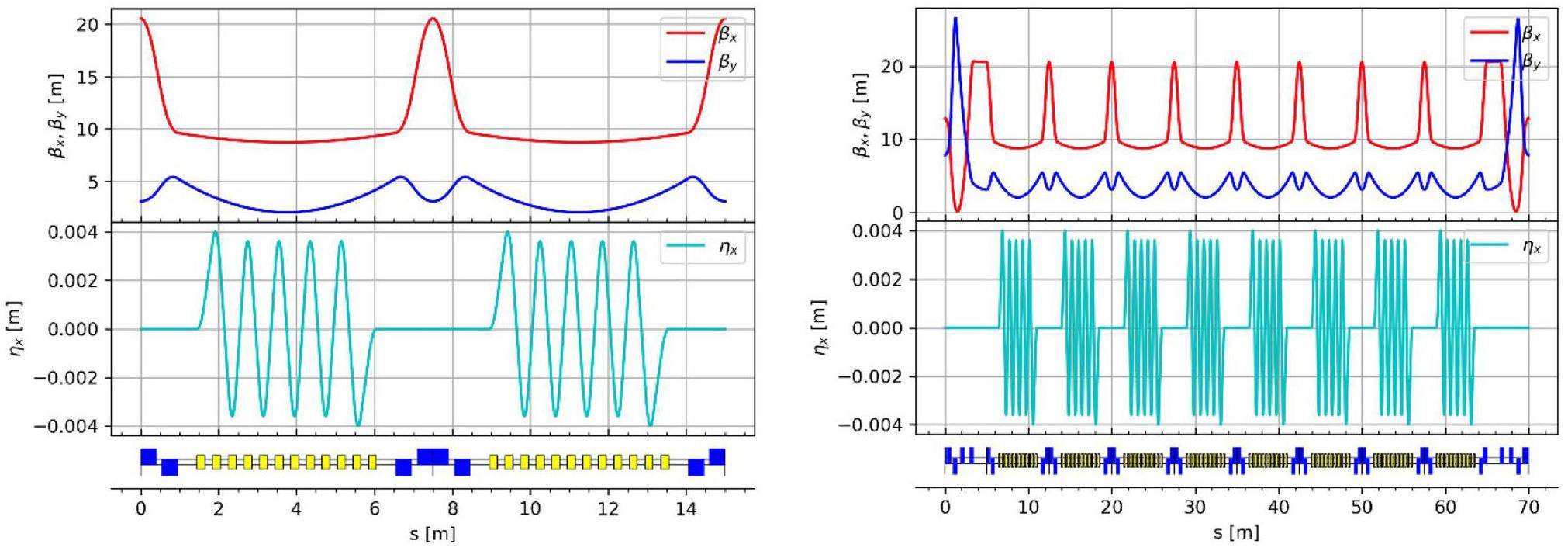

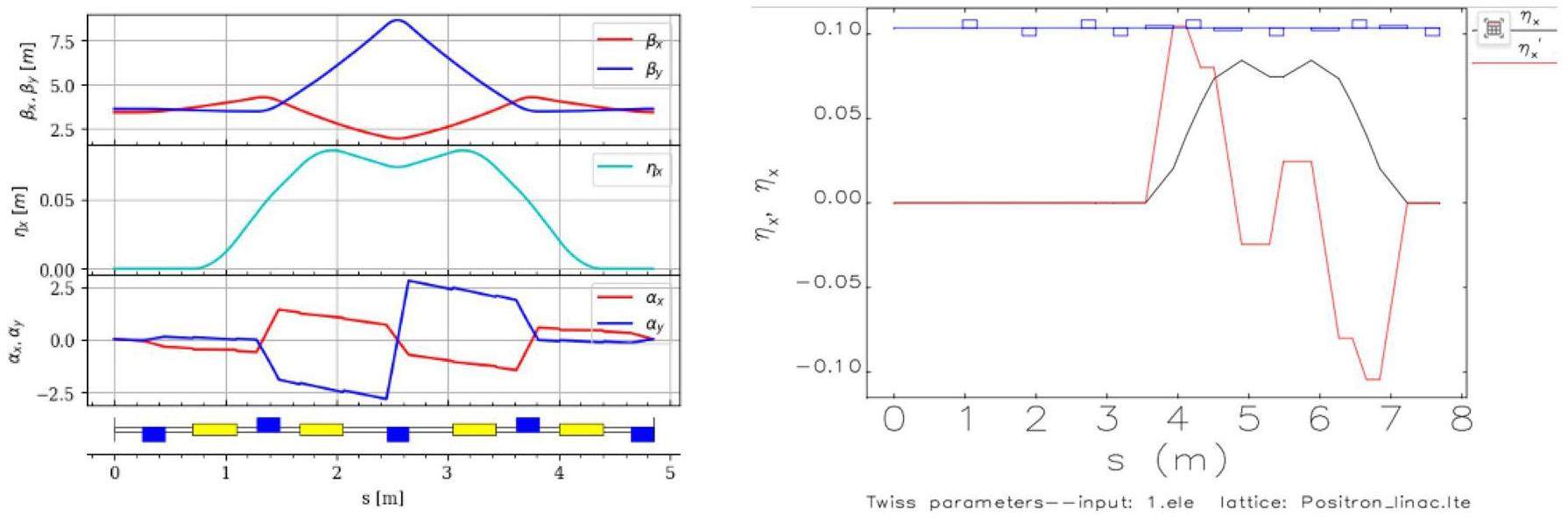

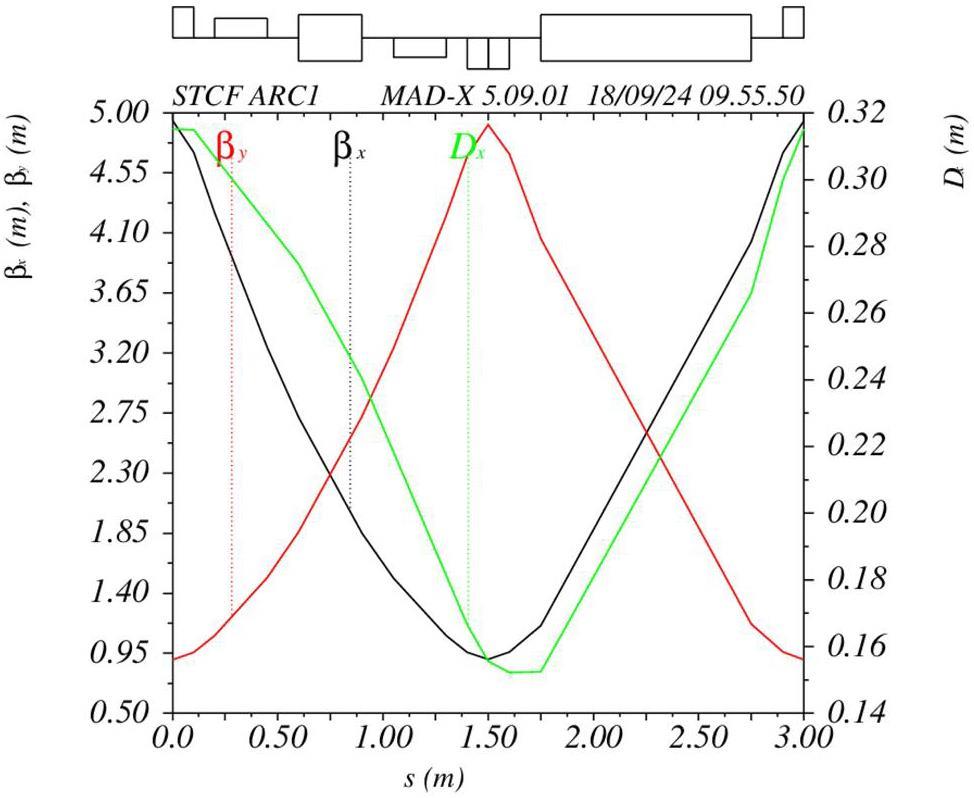

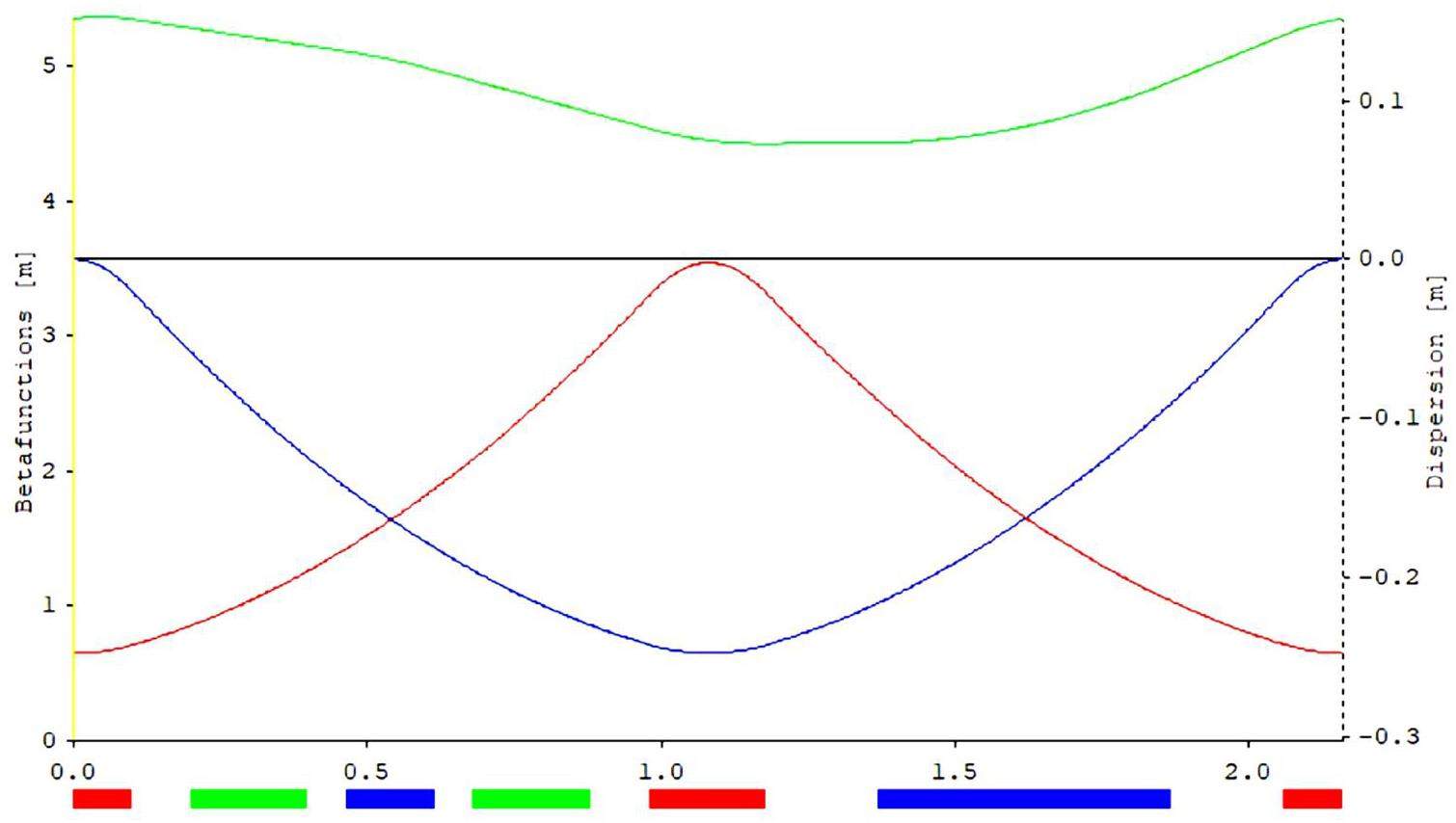

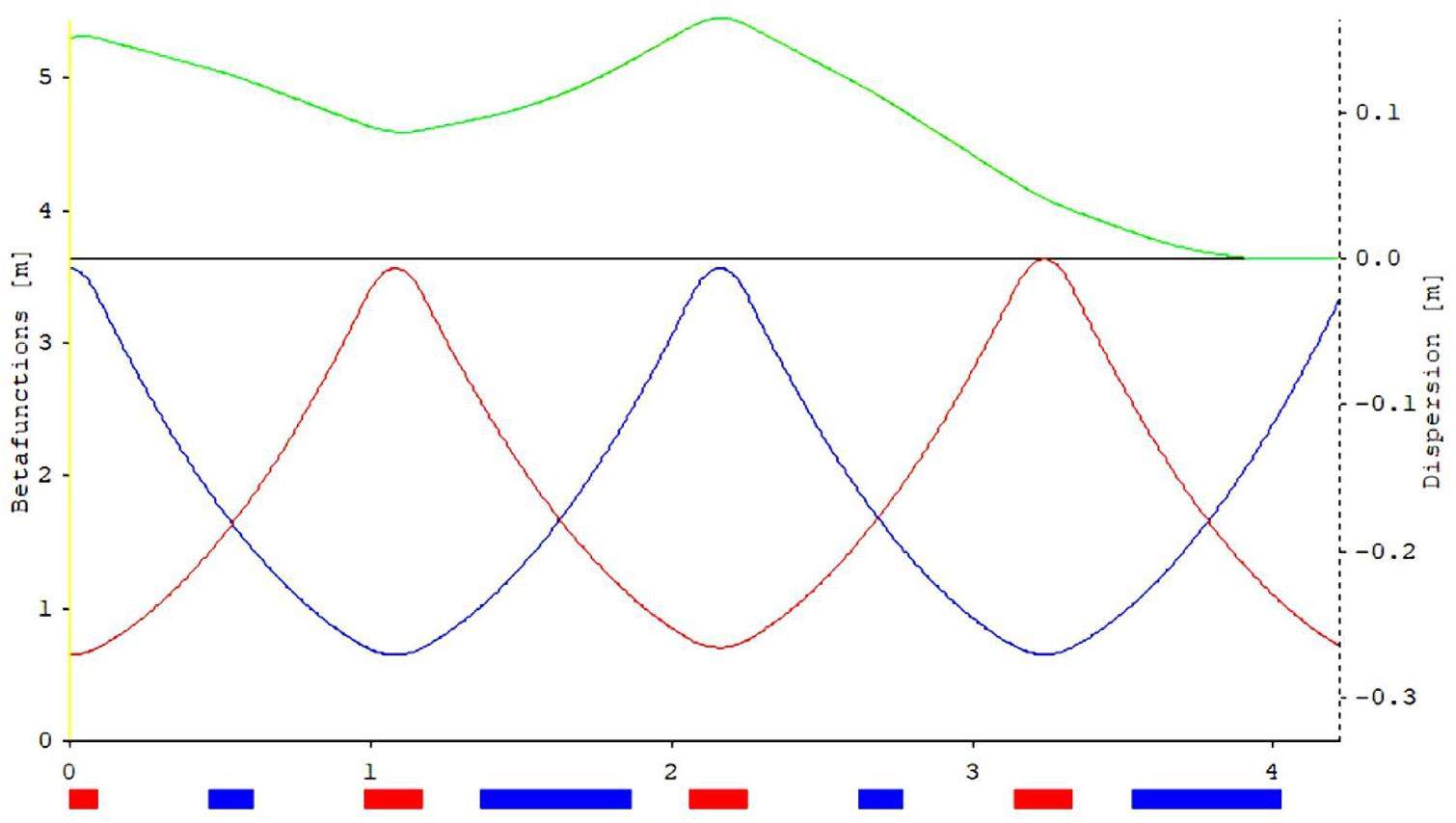

Arc optics design

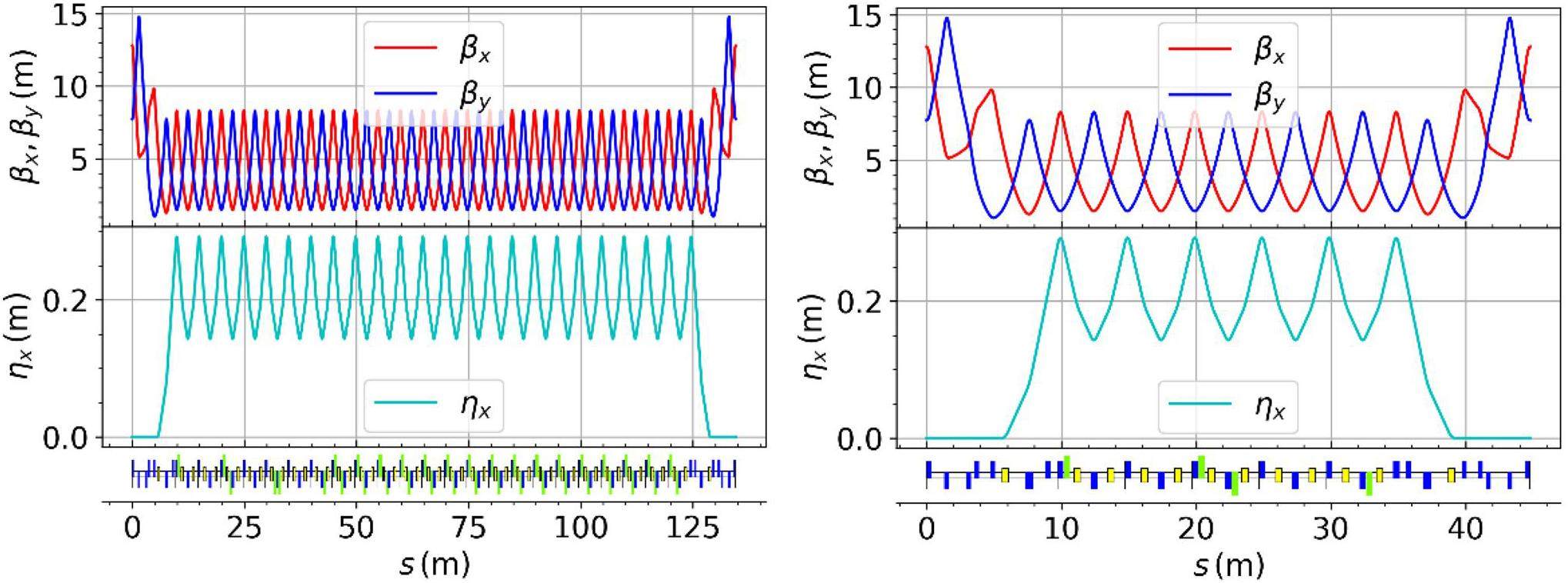

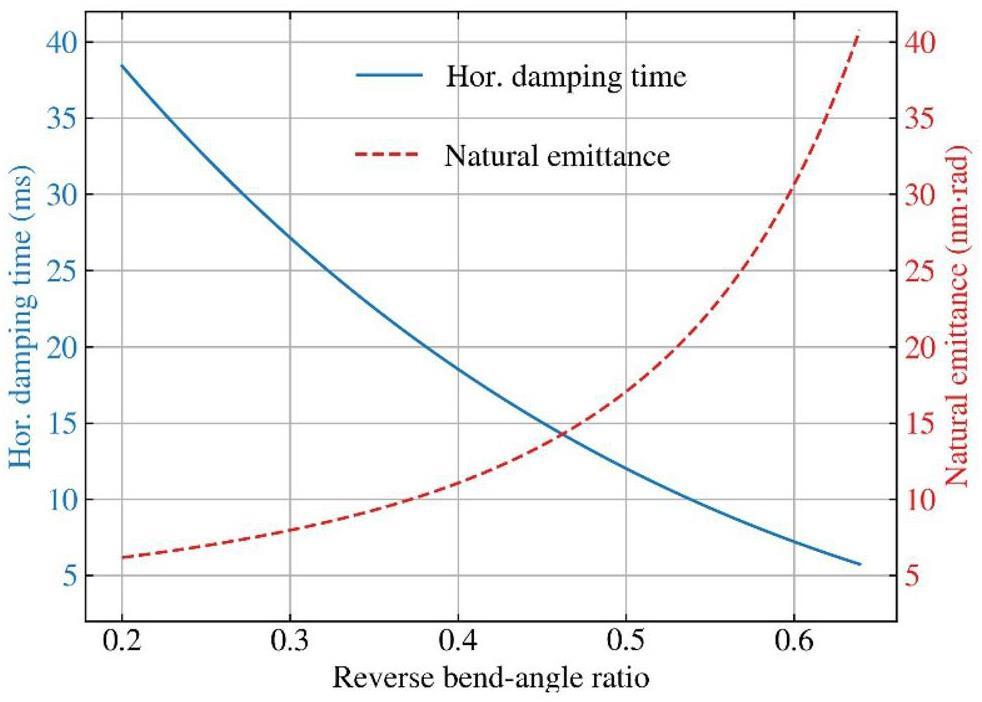

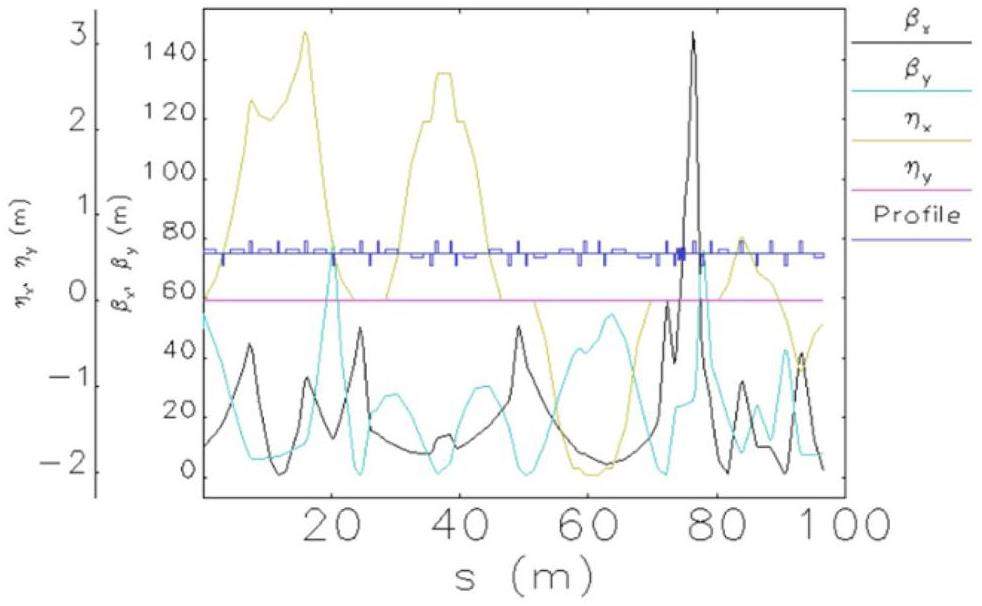

The large and small arc sections adopt the same standard FODO cell design. Each FODO cell is 4.7 m in length, providing a bending angle of 6°, a phase advance of 90°, and a momentum compaction factor of 4.9 × 10-3. Each cell includes four 0.8 m drift sections for hosting sextupole magnets and beam collimators. Figure 5 shows the optical functions of a FODO cell. The ends of each arc section contain dispersion suppressor sections and optics matching sections. The large arc section consists of 9 FODO cells plus the dispersion suppression and matching sections, totaling 57.184 m in length and providing a total bending angle of 60°; the small arc section contains 4 FODO cells plus the dispersion suppression and matching sections, with a total length of 33.684 m and a bending angle of 30°.

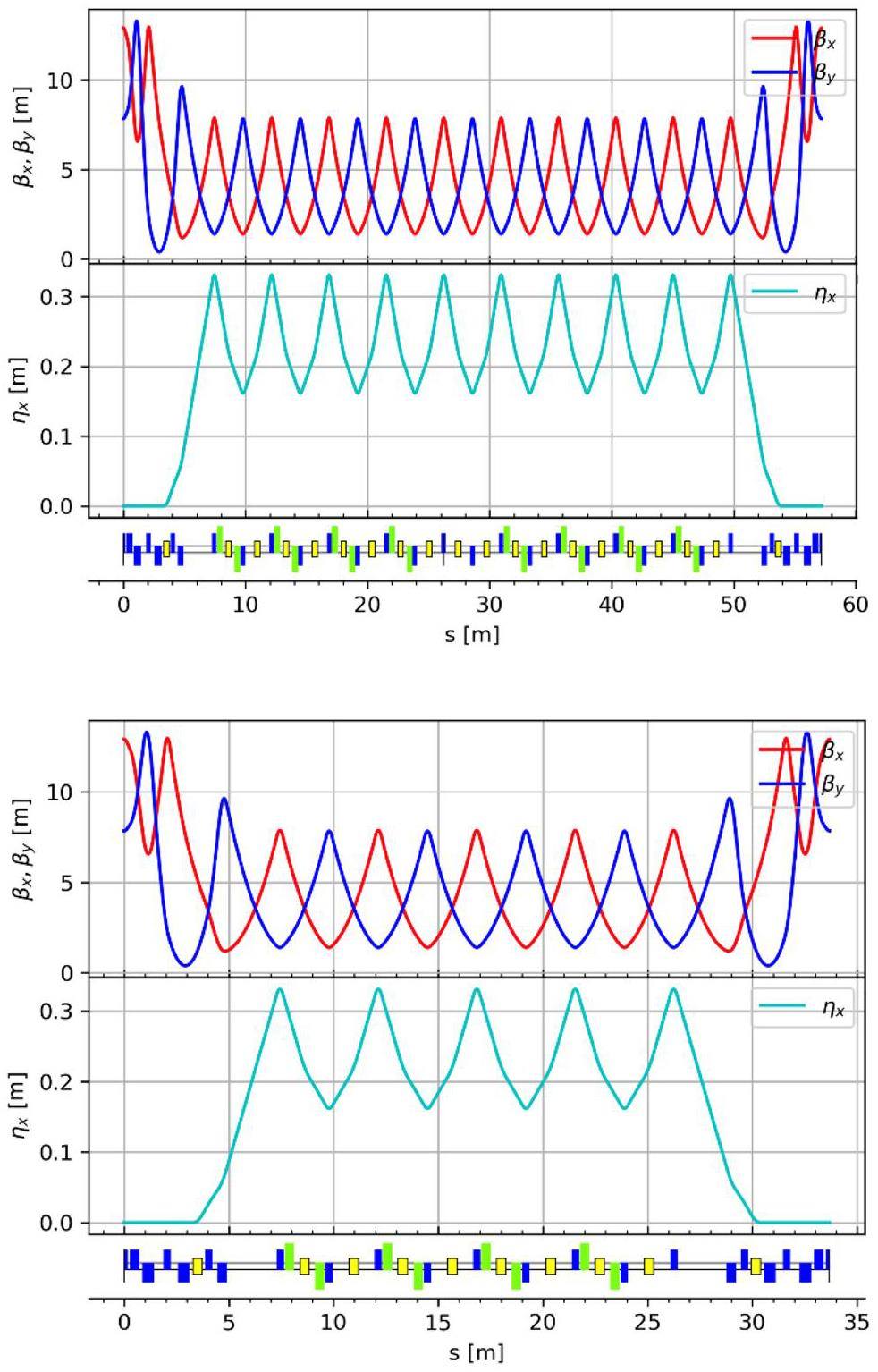

Chromaticity correction and nonlinear optimization in the arc sections are achieved using sextupole magnets. These sextupoles are placed in pairs with a phase advance of 180°, satisfying the −I transformation condition, which effectively cancels first-order geometric resonance terms. The large arc section contains 8 groups of sextupoles (4 defocusing sextupole (SD) pairs + 4 focusing sextupole (SF) pairs), and the small arc section contains 4 groups (2 SD pairs + 2 SF pairs). The field strength of each group of sextupole magnets can be adjusted independently. Figures 6 show the optical functions of the large and small arc sections.

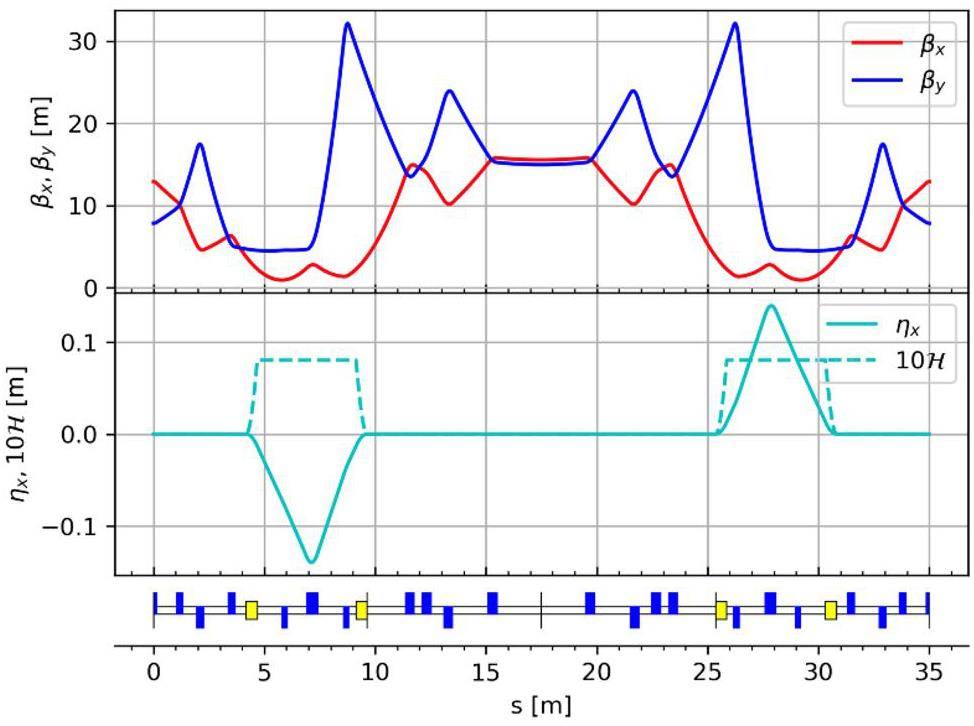

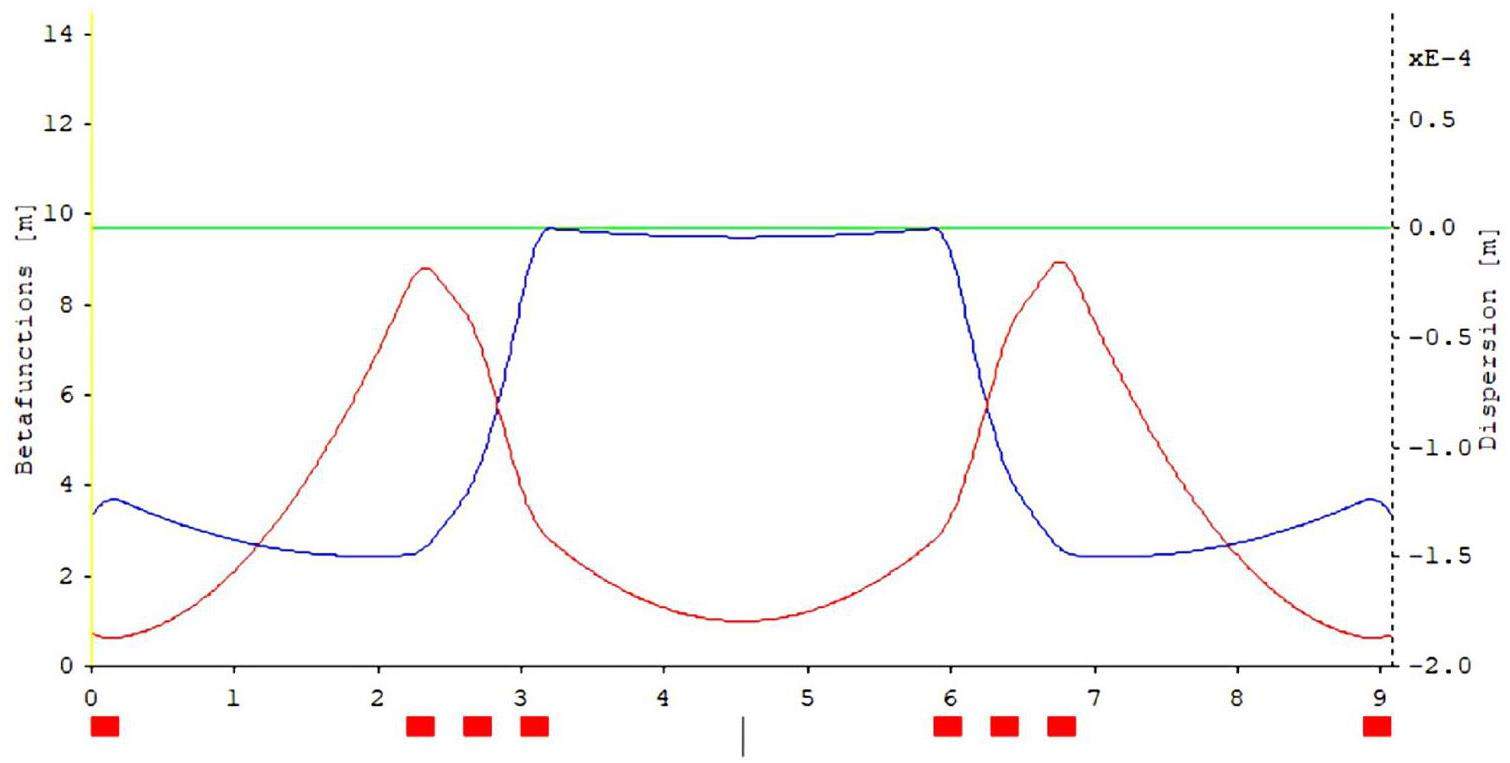

Crossing region optics

The crossing region employs two groups of dipole magnets to achieve the crossing and separation of the two beamlines. To achieve achromaticity, a triplet structure with a phase advance of π is used between the dipole magnets in each set. Additionally, two doublet structures are placed in the middle of the crossing region. To reduce the collision probabilities at the crossing point, the β functions in this section are designed to be relatively large, resulting in correspondingly larger beam sizes. The total length of the crossing region is 35 m, and the separation distance between the two rings ranges is approximately 2 m. Figure 7 shows the optical functions of the crossing region.

General straight section optics

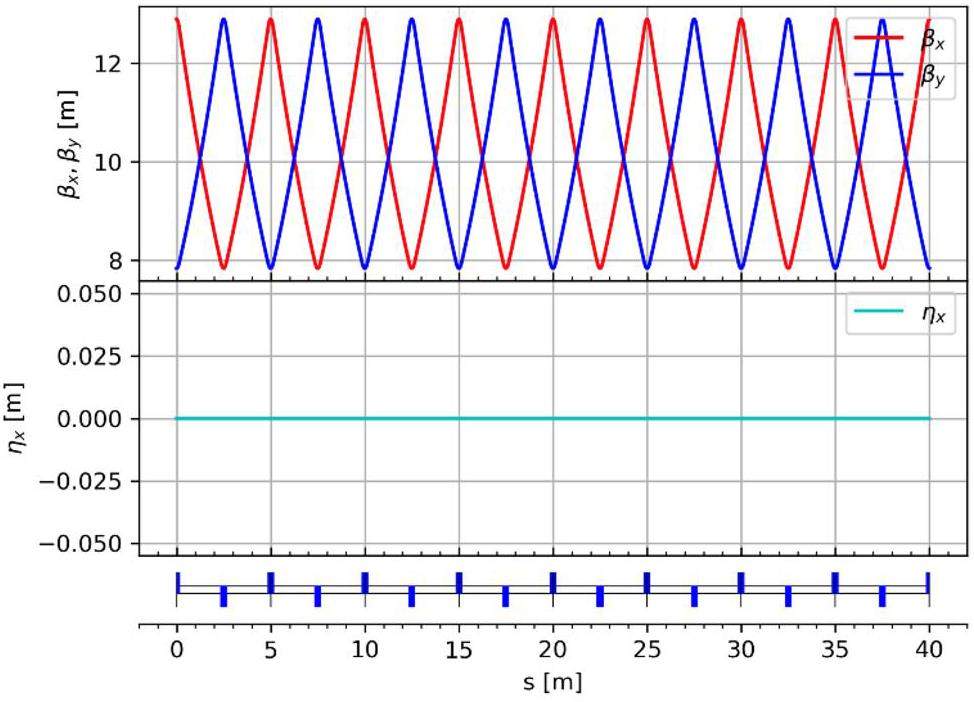

In addition to generally designed straight sections that are only for connecting the arc sections, most of the straight sections in the collider rings are dedicated segments, such as the injection and extraction section, the DW sections, the RF section, and the beam collimation section, depending on their specific functions. Here, it describes only the design of the general straight section.

The general straight section adopts a standard FODO structure. Each FODO cell is 5 m long with a phase advance of 30° and contains two drift spaces that are 2.2 m long. Figure 8 shows the optical functions of the general straight section consisting of eight FODO cells.

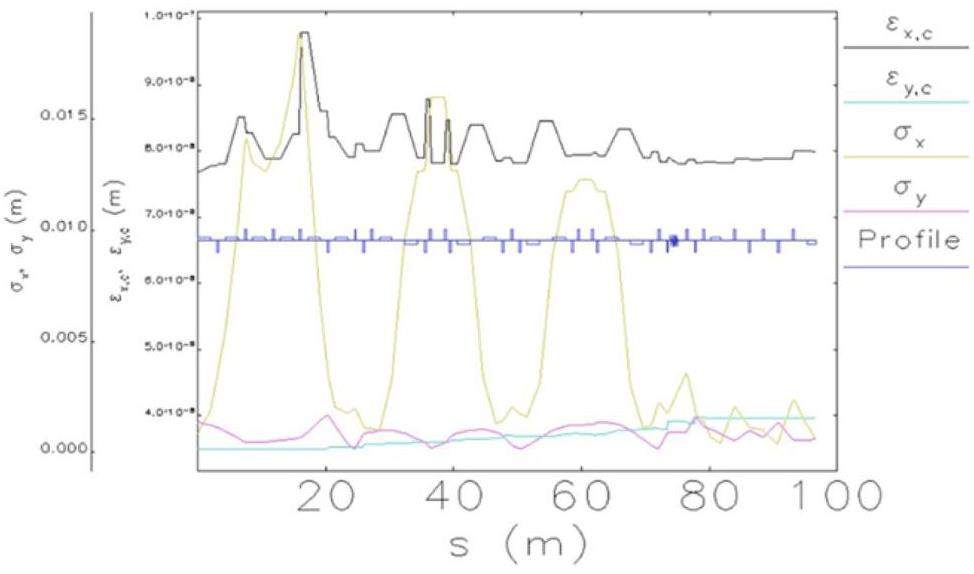

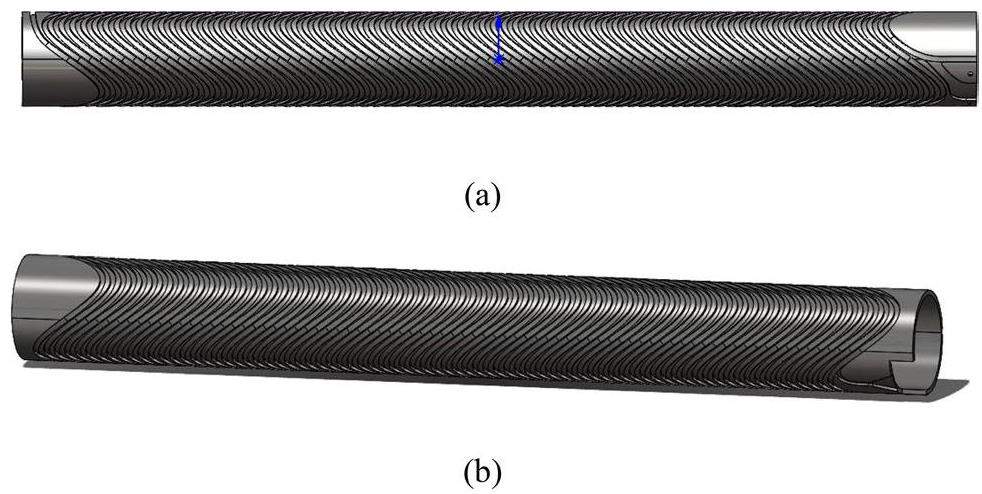

Damping wiggler section optics

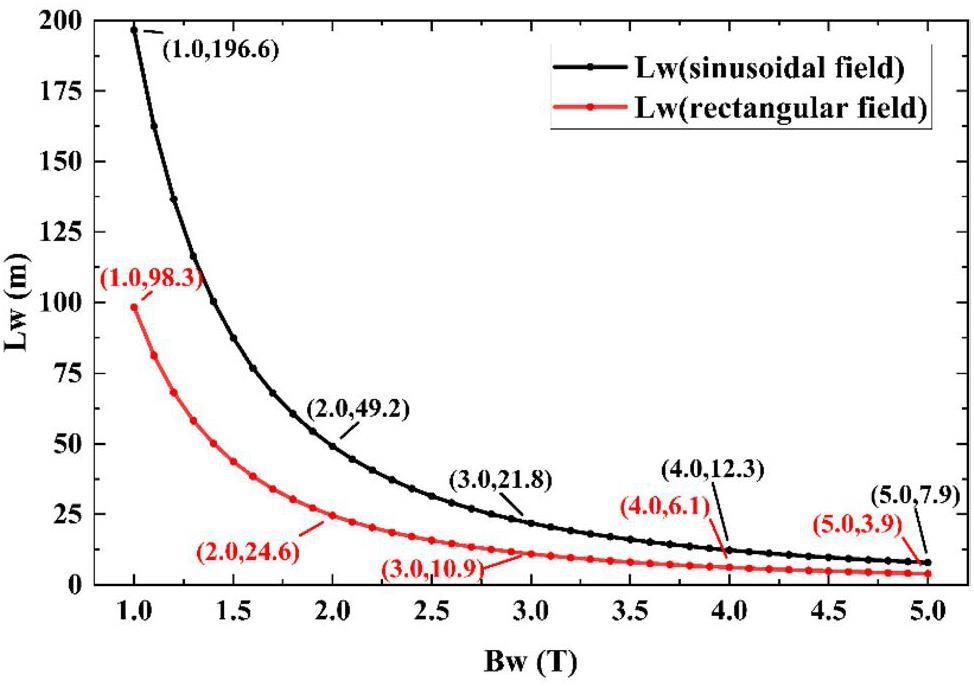

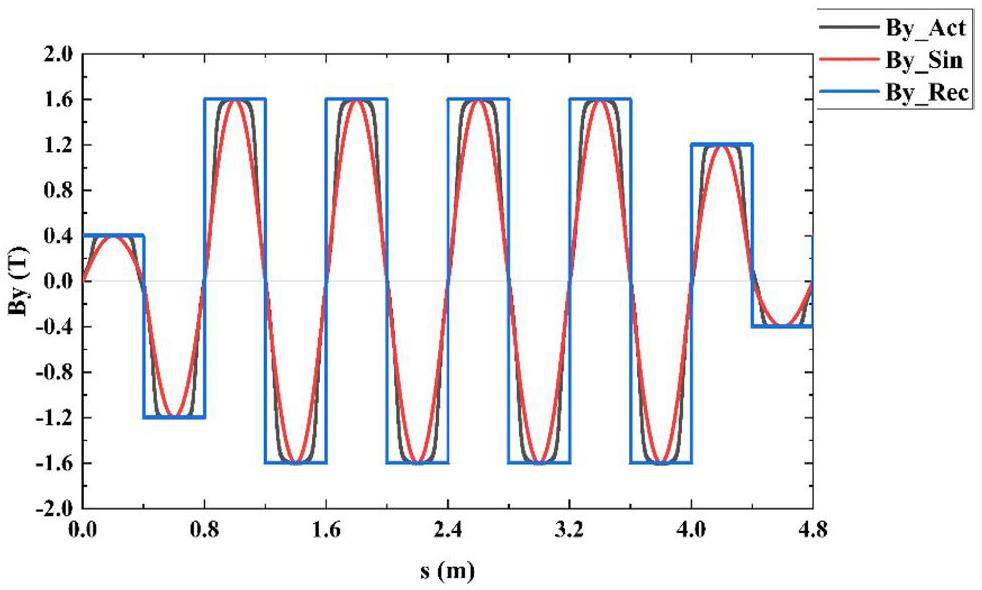

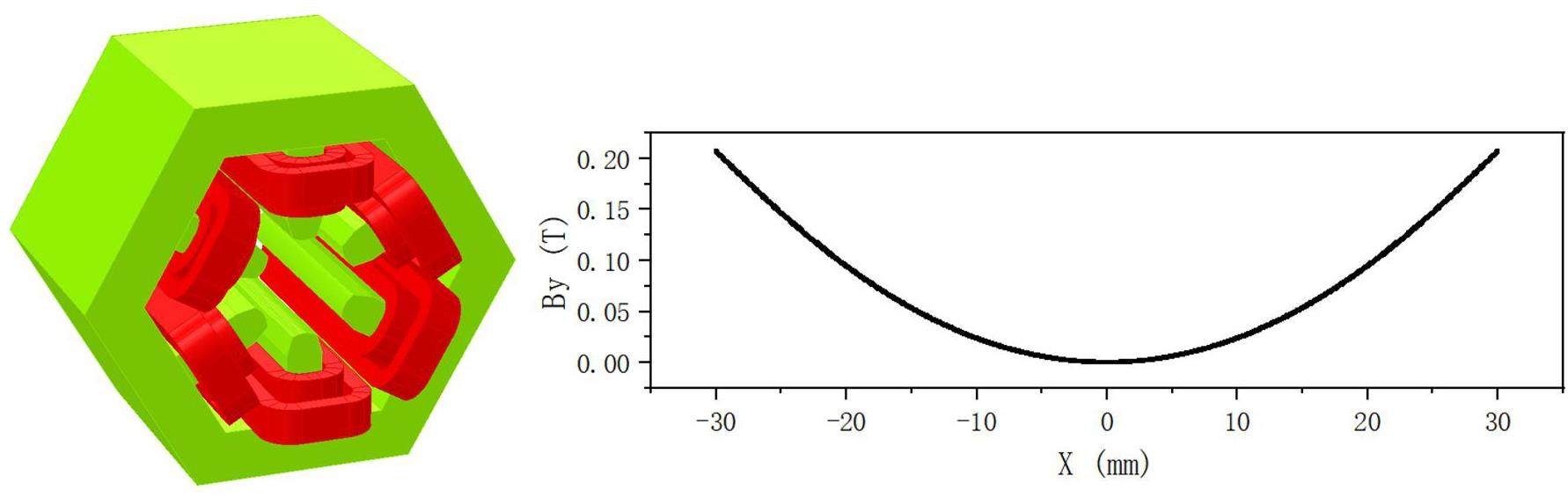

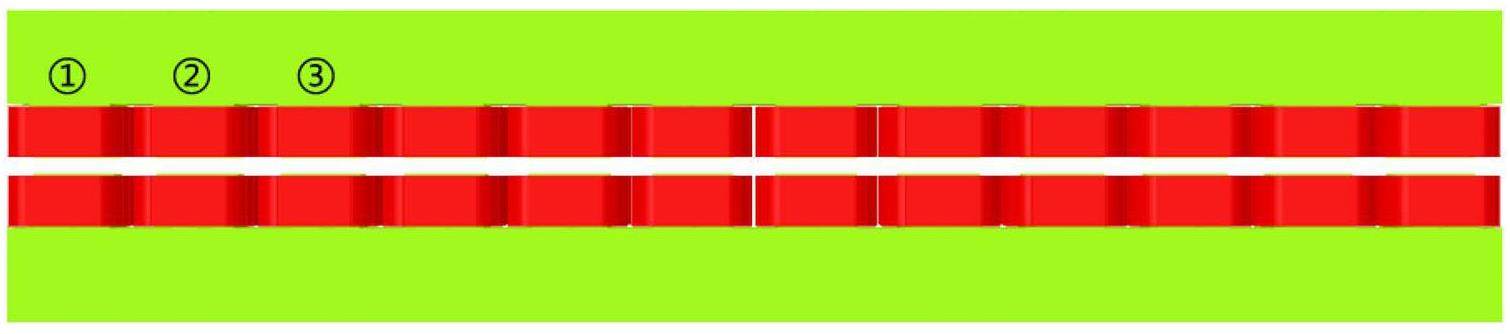

Each of the STCF collider rings includes two DW sections, which are used to reduce the damping time and adjust the beam emittance at different beam energies. Each DW section contains eight DWs that are 4.8 m long. To ensure the relatively gentle variation of the β-function within the wigglers, the lattice design incorporates a specially optimized structure for the wiggler sections.

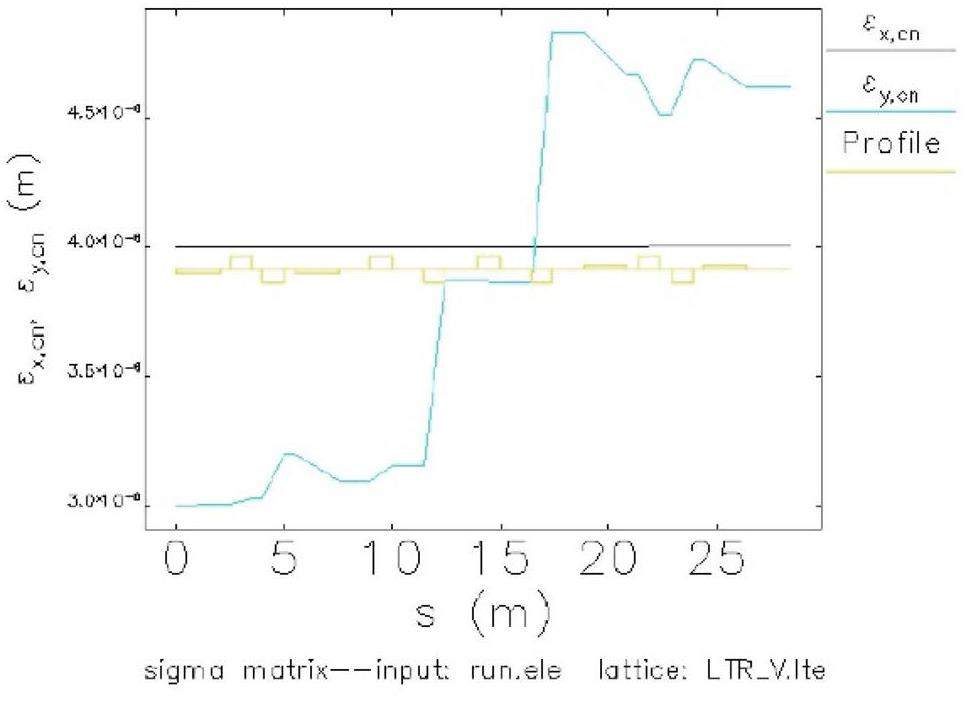

A triplet configuration is chosen as the primary lattice structure for this section because of its flexibility. This configuration allows for long drift spaces to accommodate the wigglers while ensuring slow variation of the β-function at the wiggler locations. Since commonly used lattice design codes such as MADX and SAD do not include built-in DW models, the typical approach is to model the wigglers using a series of bending magnets and drift spaces that achieve equivalent radiation damping effects. Figure 9 shows the lattice functions of two focusing cells and the long drift section within the DW region.

Because DWs influence the optical functions of the lattice, it is necessary to place several quadrupole magnets at both ends of each DW section. These are used to compensate for the optical distortions introduced by the wigglers and to match the Twiss parameters at the transition to adjacent straight sections. Table 2 lists the key parameters of the lattice design for the DW section.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Total wiggler section length (m) | 2 × 70 |

| Triplet unit length (m) | 7.5 |

| Wiggler unit length (m) | 4.8 |

| Number of wigglers per ring | 16 |

| Average β-functions at wiggler, βx/βy (m) | 5.08/3.78 |

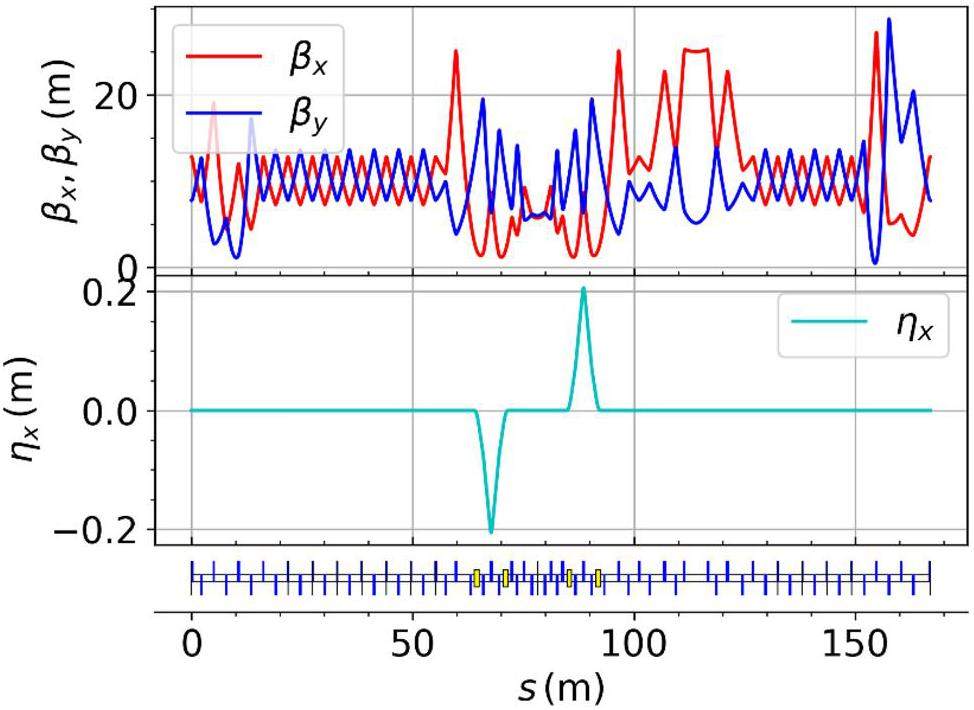

Scheme II (Single-fold symmetry)

In conjunction with developing the above scheme, we have also studied an alternative scheme called Scheme II. This scheme has a reserved space for the installation of SSs and a multifunctional long straight section.

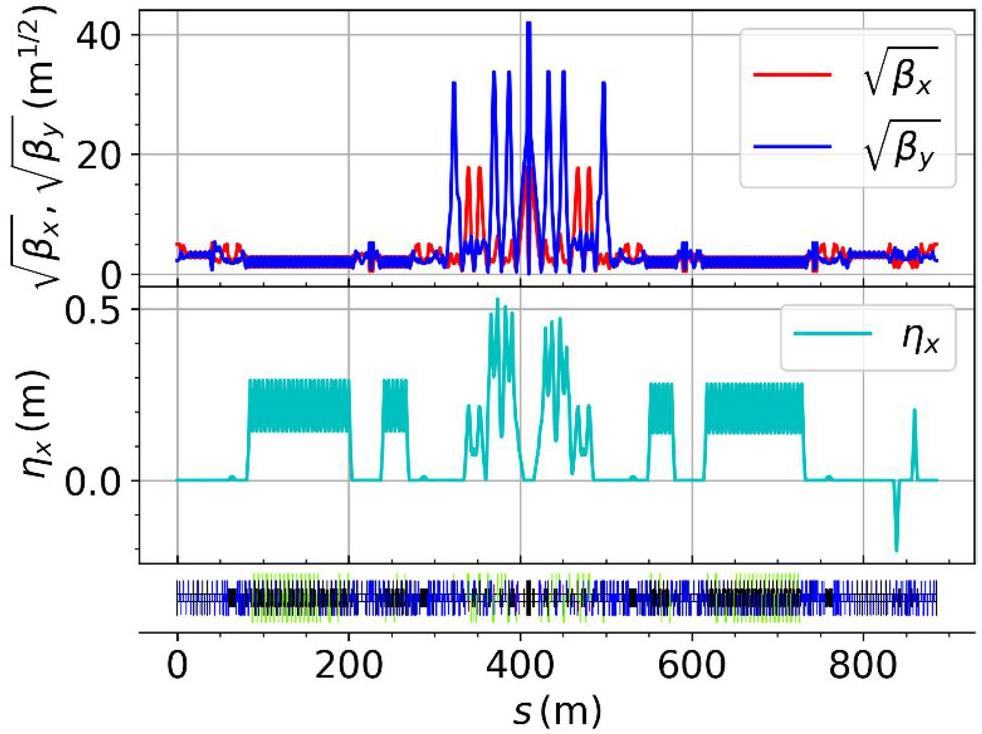

The electron ring of this scheme has four arc sections, three SSs, four DWs, one IR, and one multifunctional section. The geometric layout of the dual ring and distribution of different units are shown in Fig. 10. This layout is realized by employing dipole magnets with different bending angles on both sides of the IR and arc dipole magnets with a bending radius difference of 2.14 m between the inner and outer half-rings.

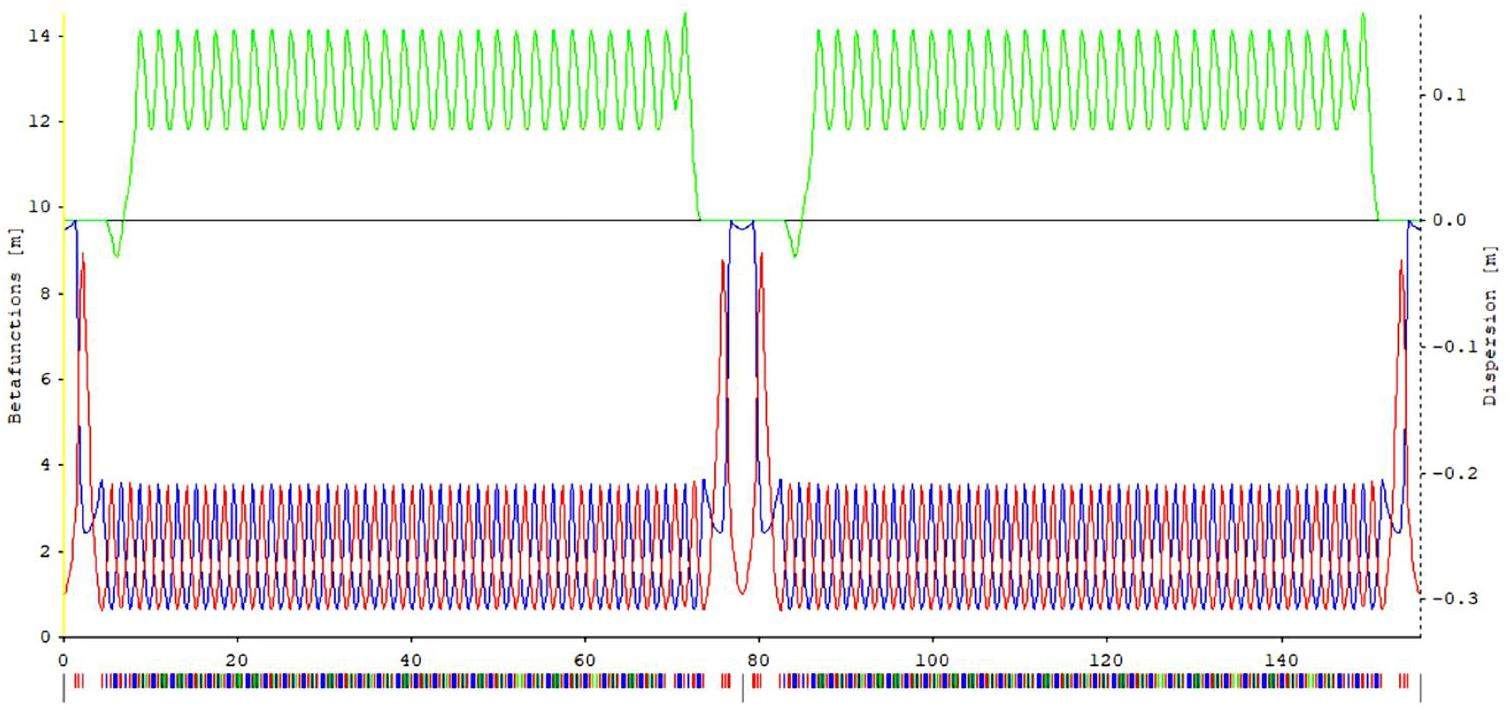

Figure 11 illustrates the full-ring lattice and its linear optical functions. Table 3 presents the main collider ring parameters of Scheme II considering intra-beam scattering (IBS), synchrotron radiation, and DWs. These parameters are for the optimal energy of 2 GeV.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Optimal beam energy, E (GeV) | 2 |

| Circumference, C (m) | 885.519 |

| Crossing angle, |

60 |

| Revolution period, |

2.953 |

| Horizontal/Vertical emittance, |

6.368 / 0.0318 |

| Coupling factor, K | 0.5% |

| β-functions at IP, |

40 / 0.6 |

| Beam sizes at IP, |

15.96 / 0.138 |

| Betatron tunes, |

33.554 / 33.571 |

| Momentum compaction factor, |

12.433 ×10-4 |

| Energy spread, |

9.908 ×10-4 |

| Beam current, I (A) | 2 |

| Number of bunches, |

738 |

| Particles per bunch, |

5.00 ×1010 |

| Bunch charge (nC) | 8.0 |

| SR energy loss, |

383.77 |

| Damping times, |

30.77 / 30.77 / 15.39 |

| RF frequency, |

499.7 |

| Harmonic number, h | 1476 |

| RF voltage, |

2 |

| Longitudinal tune, |

0.0169 |

| Bunch length, |

10.25 |

| RF acceptance, |

1.58 |

| Piwinski angle, |

19.26 |

| Beam–beam parameters, |

0.0024/0.081 |

| Hourglass factor, |

0.8804 |

| Peak luminosity, L (cm-2 s-1) | 1.03 × 1035 |

| Touschek lifetime, |

>250 |

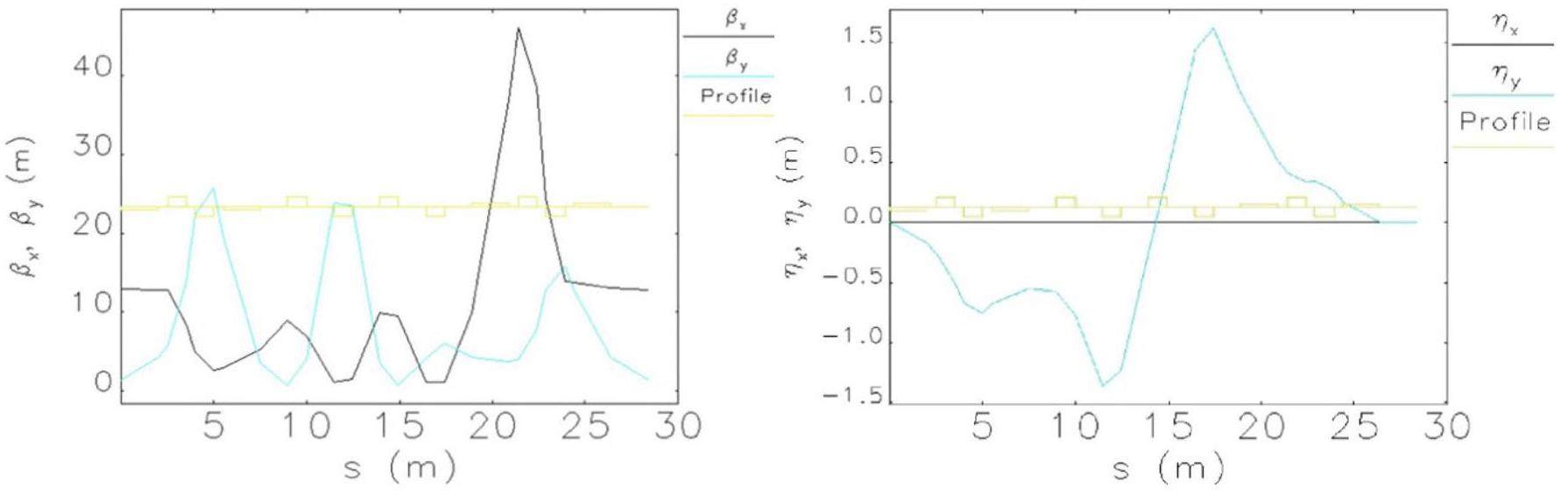

IR optics–scheme II

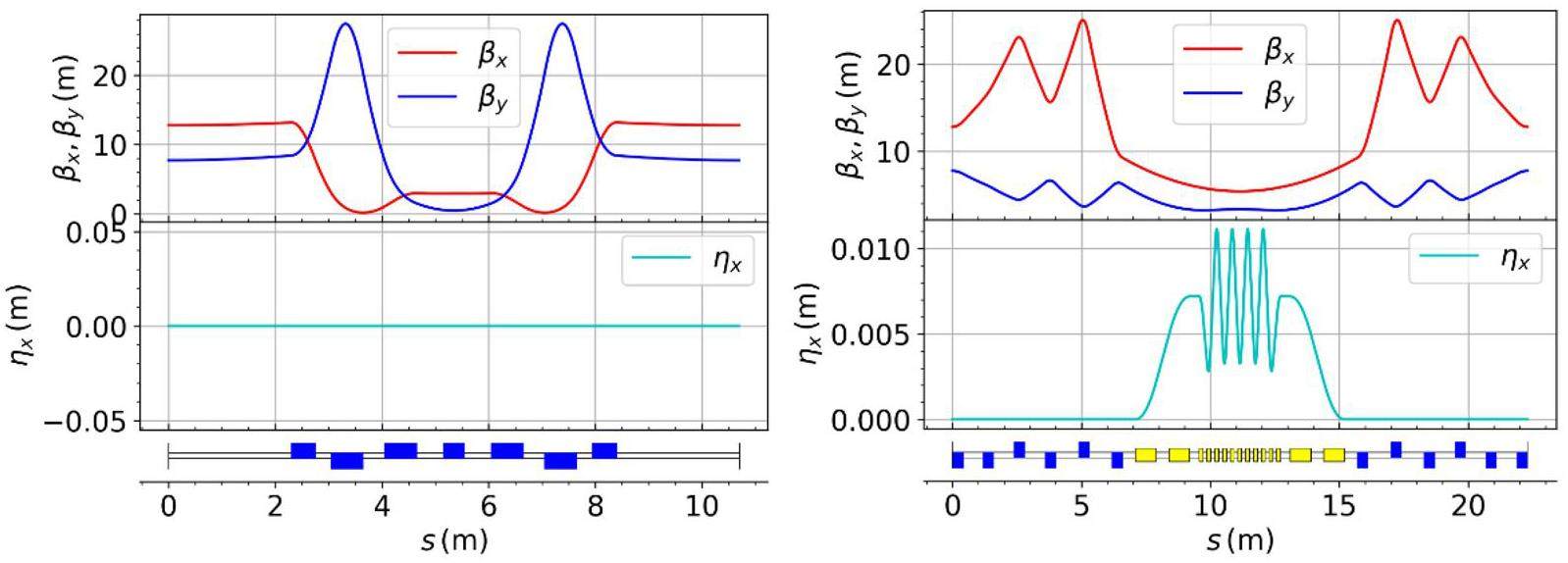

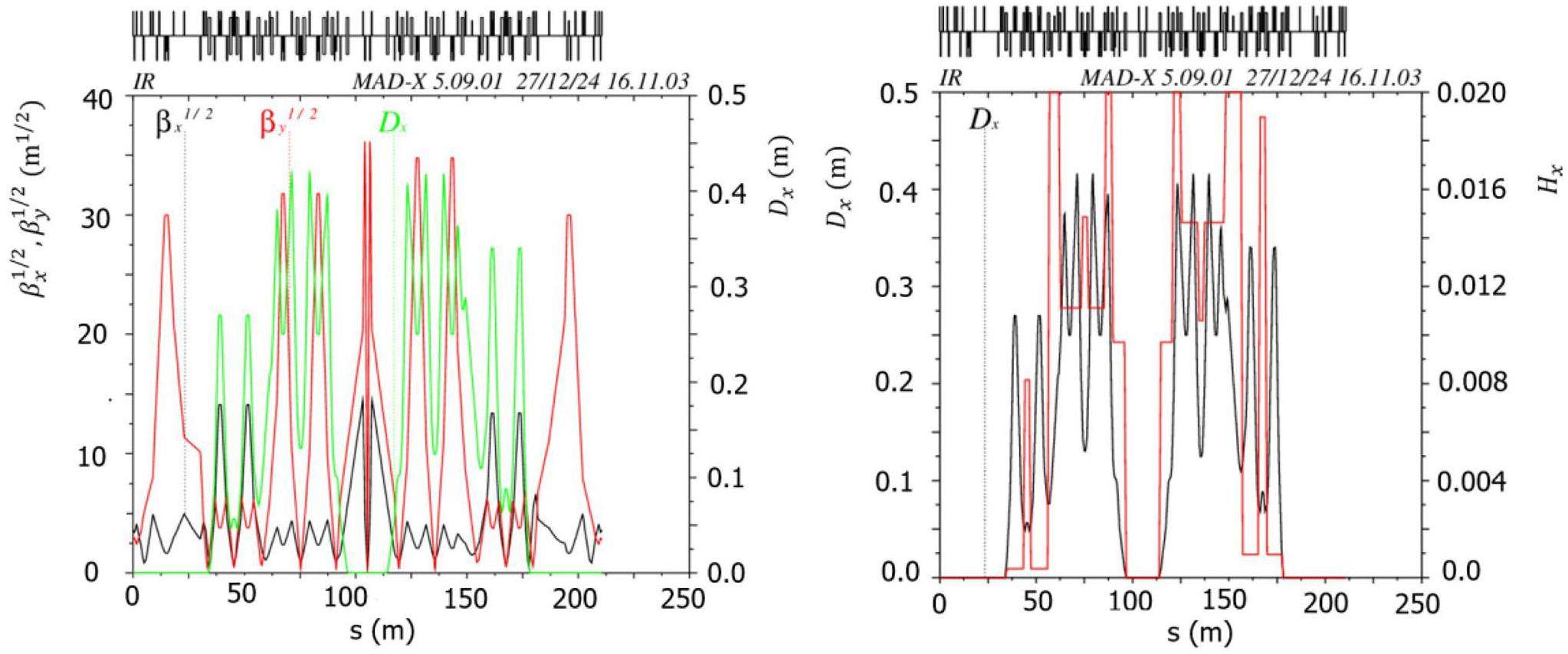

The IR adopts the crab-waist collision scheme, and its lattice structure is similar to that in Scheme I (see Sect. 2.2.3). The linear optics system of the right half (the left half has the same functional partitioning but with different parameters) consists sequentially of the final telescope (FT), the local chromaticity correction system (LCCS), the crab sextupole (CS) section, and the Matching Transport (MT) section, covering a total bending angle of 60°. At the IP, the β functions are

In addition to sextupoles for correcting first- and third-order chromaticities [5], the IR is also equipped with weak sextupole magnets [6] to optimize nonlinear performance. The geometric layout of the IR is shown in Fig. 12, and its linear optics functions are shown in Fig. 13.

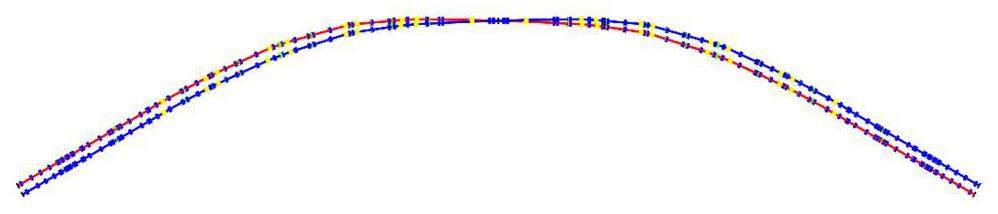

Arc optics–scheme II

To implement the dual-ring layout, the arc sections are divided into inner and outer arcs, each consisting of a long arc section with a 120° bend and a short arc section with a 30° bend. Both are constructed using FODO structures with horizontal and vertical phase advances of 90° and a bending angle of 5°. In the FODO structures of the inner and outer arcs, the bending magnets have a curvature radius difference of 2.14 m, while the quadrupoles, sextupoles, and drift sections have equal lengths.

Figure 14 shows the lattice functions of the long and short arc sections in the outer half-ring. In the short arc, non-interleaved sextupole pairs with a –I transfer are used for chromaticity correction. In the FODO cells of the long arc, a focusing sextupole follows each focusing quadrupole, and a defocusing sextupole follows each defocusing quadrupole. A sequence of four identical FODO structures forms one HOA (Higher-Order Achromat) unit, effectively canceling the first- and second-order geometric driving terms [7].

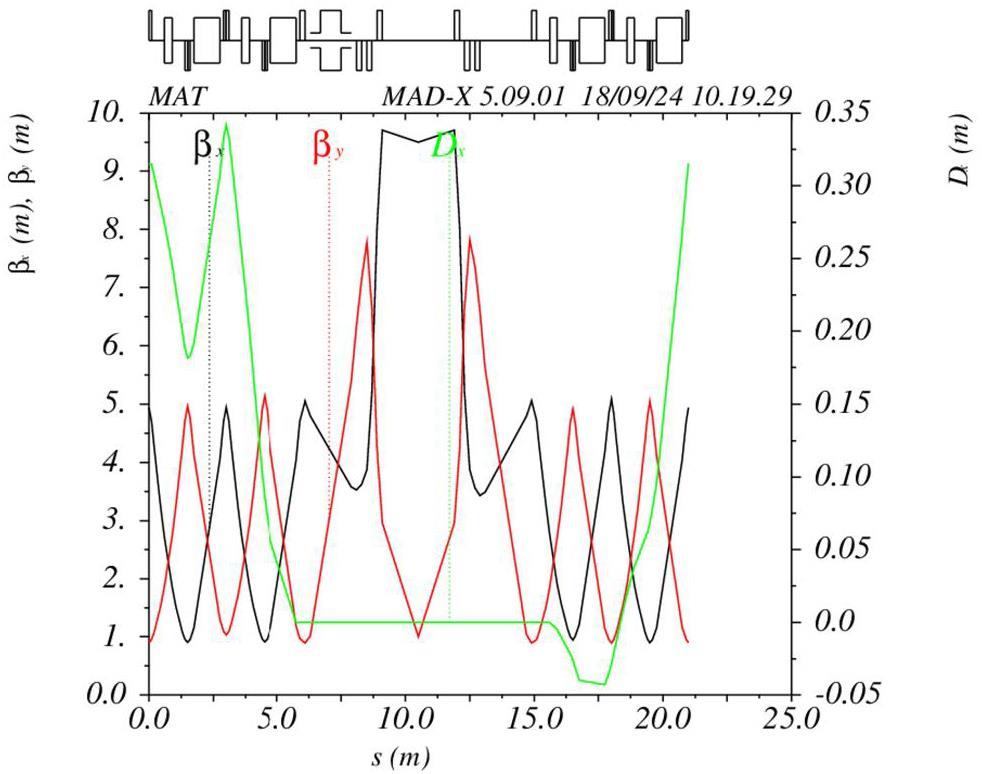

Straight section optics–scheme II

The straight sections include medium straight sections dedicated to the installation of SSs and DWs, as well as the multifunctional region for hosting the injection system, RF cavities, dual-ring crossing, and phase adjustment. Their corresponding linear optical functions are shown in Figs. 15 and 16.

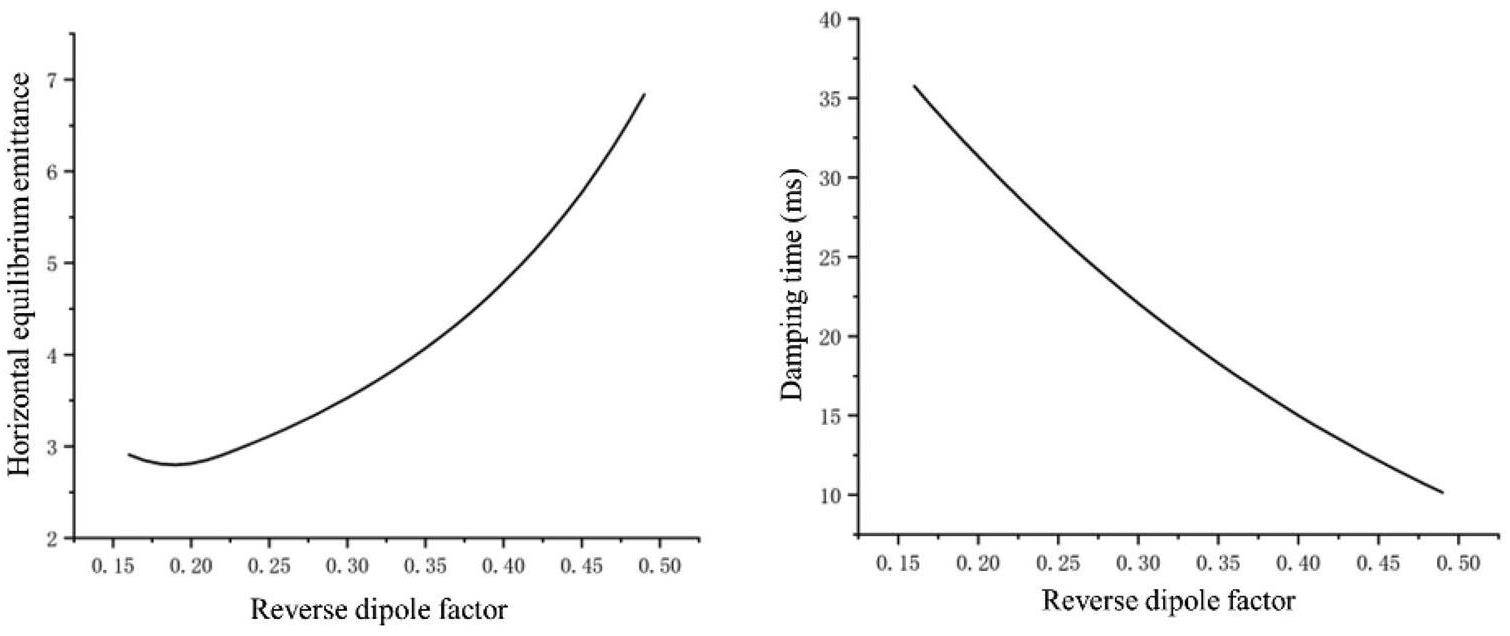

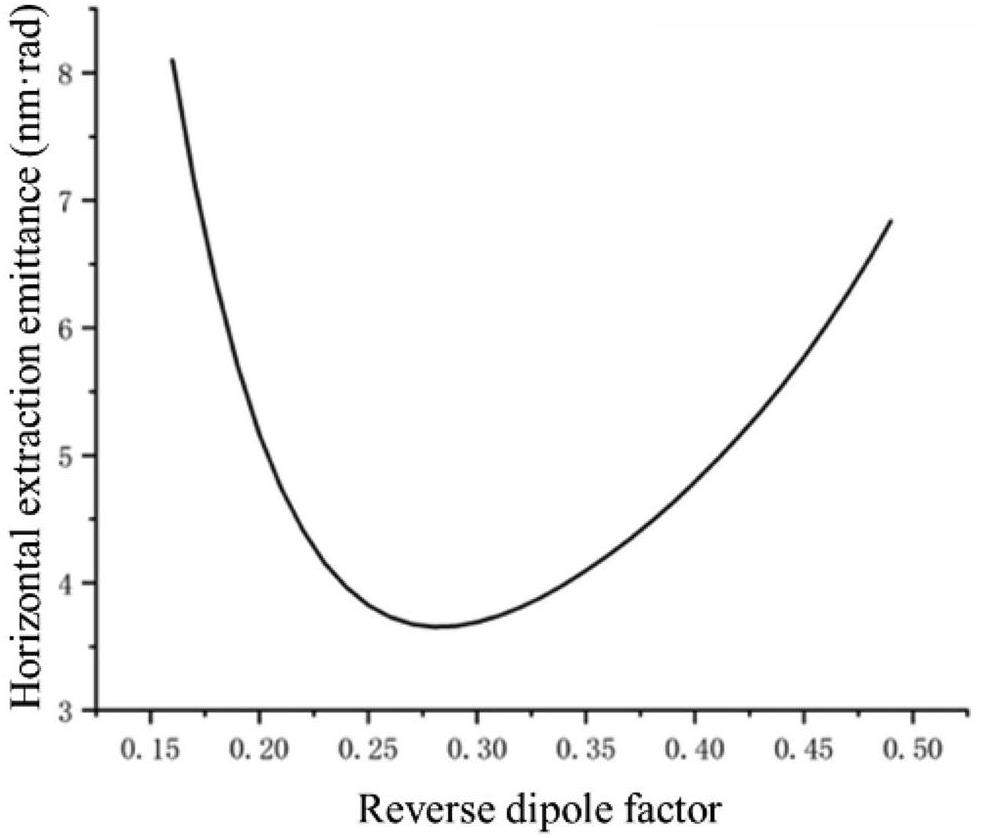

SS refers to the space reserved for Siberian Snakes, which has an azimuthal angle of 120° between each pair. To regulate the damping time, two DWs are installed in both the inner and outer half-rings. Each wiggler is positioned at the center of its respective DW section, where a non-zero dispersion function is present. The dispersion function can be tuned by adjusting the magnetic field strength of the bending magnets, which enables control over the damping time and emittance. Six quadrupole magnets are arranged to ensure that the working point remains constant with varying wiggler field strength.

Dynamic aperture and Touschek lifetime–Scheme II

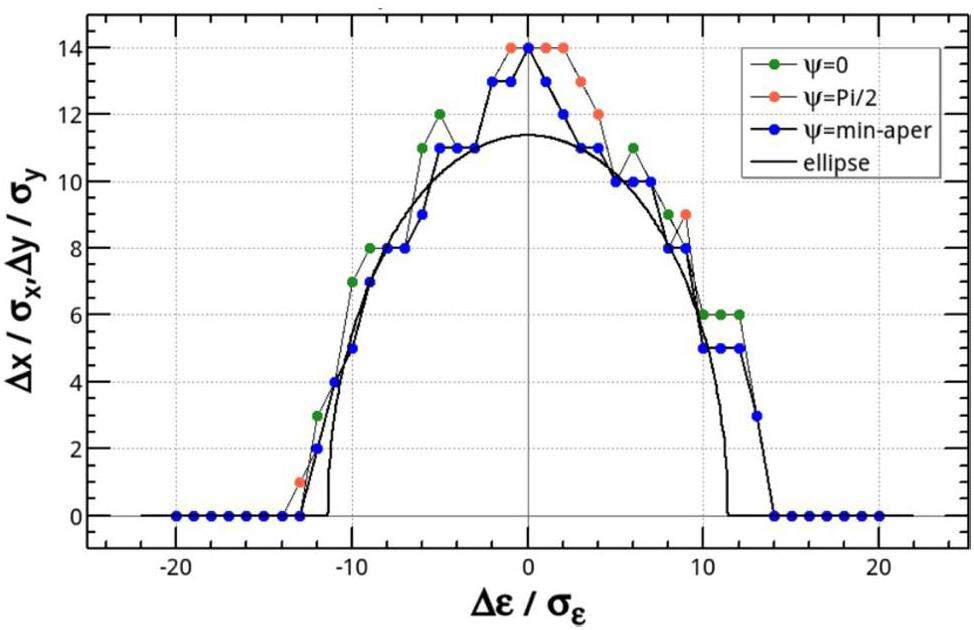

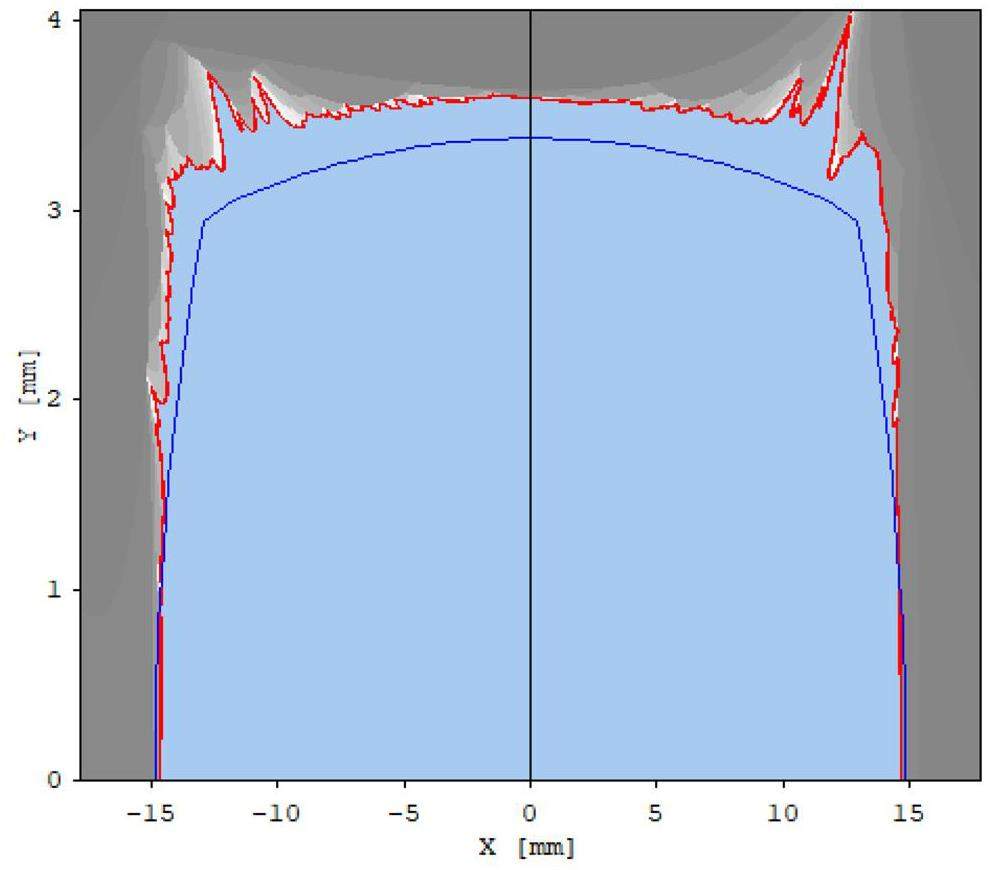

Placing phase tuners and sextupoles at the IP mirror position [8] enables the independent optimization of second- and third-order chromaticity, the W-function, and momentum acceptance. This optimization results in a large off-momentum dynamic aperture and momentum aperture. At a design luminosity of 1.03×1035 cm-2s-1

Interaction region optics design

The key objective of the lattice design of the STCF IR is compressing the β function at the IP to enhance luminosity while maintaining sufficient momentum acceptance and dynamic aperture for an adequate Touschek lifetime. This requires the careful optimization of both the linear lattice and nonlinear optics corrections in the IR. The fundamental design principle is to coordinate the linear optics with the phase advances required for nonlinear cancellation and the minimization of the effects of nonlinear sextupole fields.

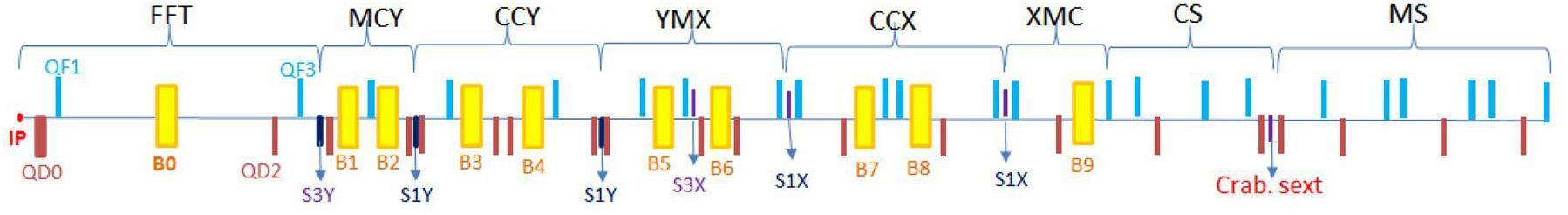

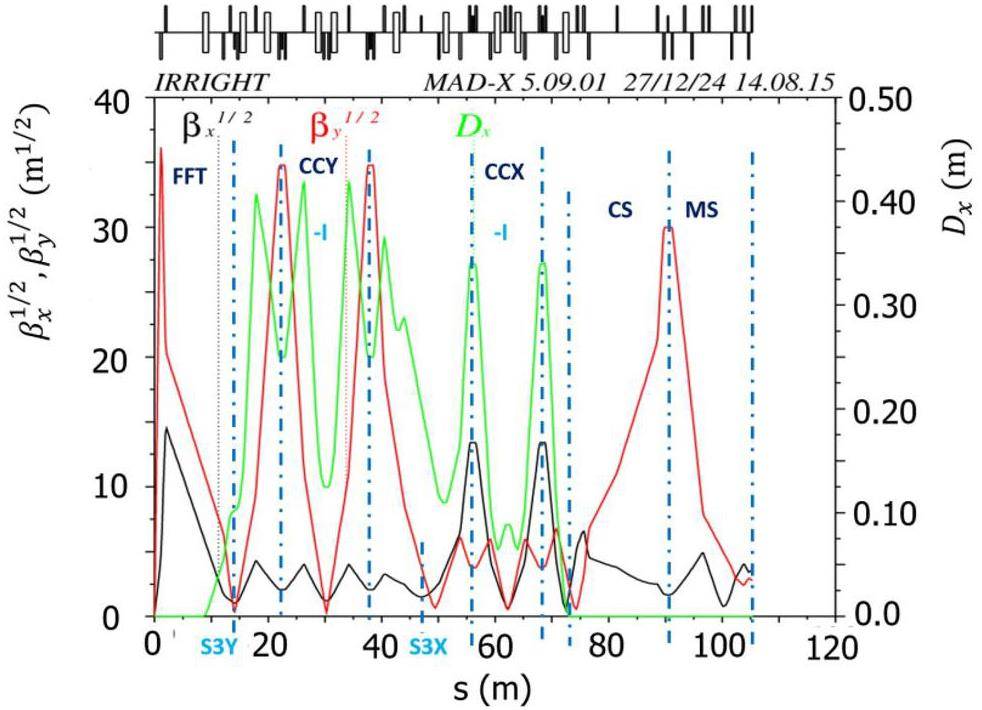

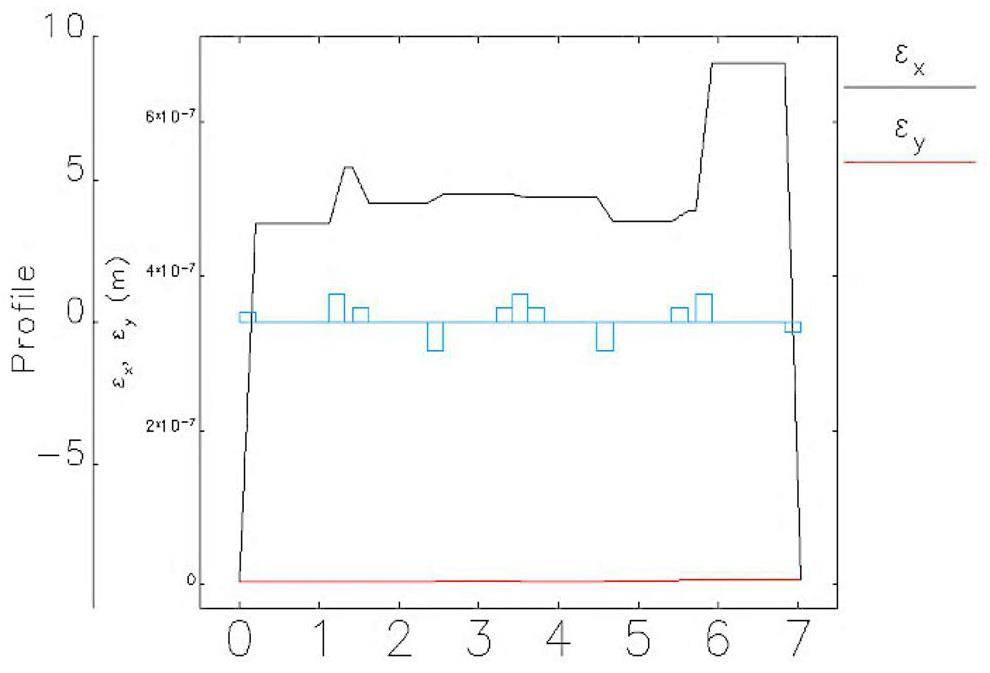

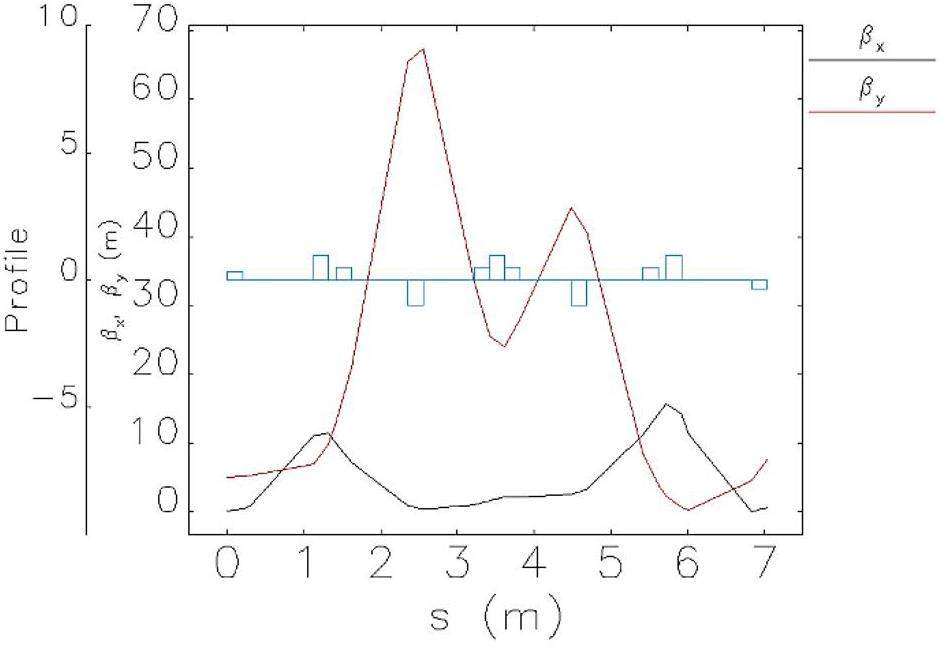

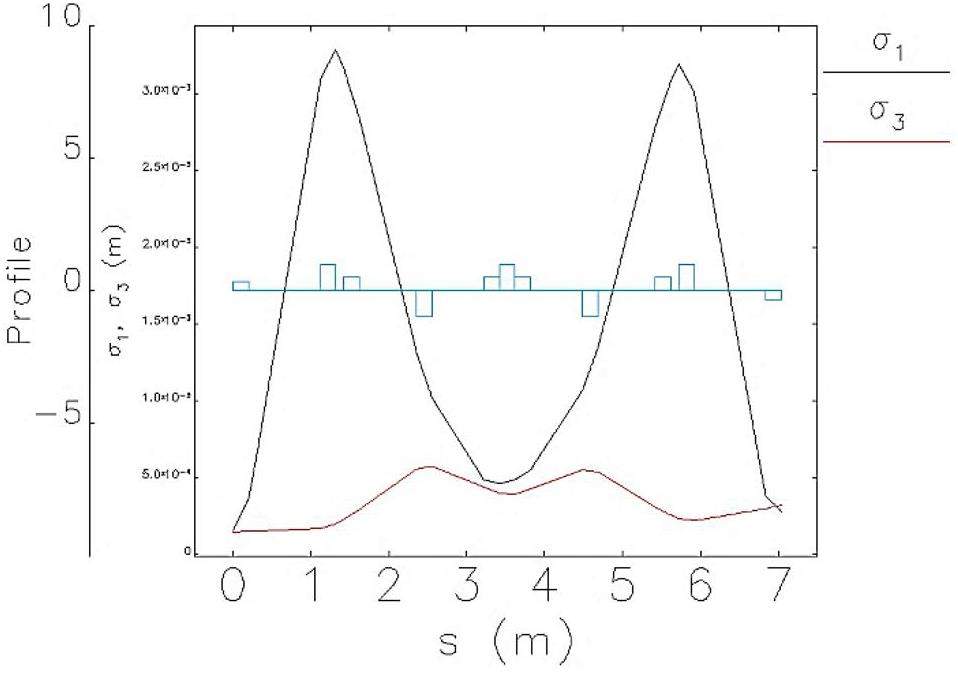

Following the design philosophy of other new-generation electron–positron colliders [1, 4, 10–12], the STCF IR lattice adopts the modular structure illustrated in Fig. 18. It consists of a final focusing telescope (FFT) that minimizes the β functions at the IP, a matching section (MCY) between the FFT and the vertical chromatic correction section (CCY), local vertical/horizontal chromaticity correction sections (CCY/CCX), a matching section (YMX) from the CCY to the CCX, a dispersion suppressor (XMC), a CS section, and an MS connecting the IR to the long straight section. The linear optics functions of the STCF IR are shown in Fig. 19.

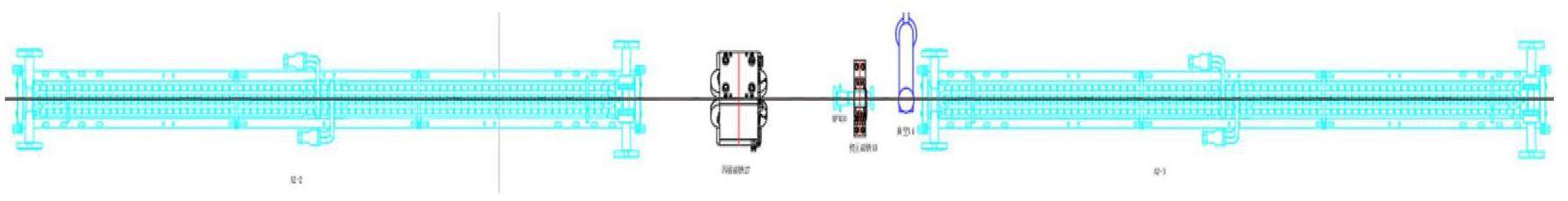

The FFT section adopts a focusing structure composed of two groups of quadrupole magnets: one superconducting and one room-temperature. The superconducting quadrupole doublet is used to achieve an extremely low

A bending magnet (B0) is inserted into the FFT to generate the dispersion required for local chromaticity correction. Given its proximity to the IP, the strength of this bending magnet should remain minimal to reduce the amount of synchrotron radiation background entering the detector.

The MCY section adopts a FODO-like cell starting with a defocusing quadrupole, making

The local vertical chromaticity correction section (CCY) must implement –I transformation between sextupole pairs to cancel their nonlinearities. This can be realized using two center-symmetric FODO cells with horizontal and vertical phase advances of π/2. Two identical dipole magnets, B3 and B4, are used to create symmetric dispersion.

The YMX section converts the β-function condition of

The local horizontal chromaticity correction section (CCX) is designed similarly to the CCY section, requiring a –I transfer transformation between sextupole pairs to cancel nonlinearities. Two identical dipole magnets, B7 and B8, are used to form symmetric dispersion. The XMC section cancels dispersion in the collision region, ensuring zero dispersion at the crab sextupoles.

The CS section consists of six quadrupole magnets satisfying the phase advance constraint between the crab sextupole and the IP and the alpha function constraint at the crab sextupole:

The dipole magnets in the IR have a total bending angle of 60°, and they are 1 m long. Apart from B0, which has a fixed bending angle of 1°, the strength of all dipoles must be chosen to adjust the dispersion function and keep the dispersion invariant

Transverse beam dynamics

The design goal of the transverse beam dynamics in the collider rings is achieving a sufficiently large dynamic aperture and momentum acceptance to ensure high injection efficiency and long beam lifetime.

In the arc sections of the collider rings, strong quadrupole focusing is required to realize a low emittance that is comparable to that of third-generation synchrotron light sources. A non-interleaved sextupole configuration was initially used to correct chromaticity in the arcs; however, owing to the limited number of sextupole pairs, the required sextupole strength was relatively high, resulting in significant nonlinear effects. Therefore, based on the concept of second-order achromats proposed by K.L. Brown [13], an interleaved –I transformation scheme was adopted for placing sextupoles in the arcs. This configuration cancels the first-order geometric terms generated by the sextupoles, although it cannot cancel higher-order geometric terms. Nevertheless, the use of more sextupole pairs allows for lower individual magnet strengths, leading to weaker residual higher-order terms. The increased number of sextupoles also aids in the global nonlinear optimization of the collider rings.

However, the dynamic aperture and momentum acceptance of the collider rings are primarily limited by the IR, which produces most of the ring’s nonlinearities [16, 17]:

· The IR must incorporate ultra-strong FF quadrupoles in a compact space to achieve extremely small

· The crab-waist mechanism imposes strict requirements on the phase advance between the crab sextupoles and the IP. Any lattice nonlinearity or imperfection can disrupt these phase constraints.

· Using compensation solenoids to cancel the detector solenoid field directly affects IR performance. For instance, solenoid and quadrupole field overlaps must be avoided, as they increase vertical emittance.

All of these nonlinear and high-order effects degrade the dynamic and momentum apertures of the collider rings, severely reducing beam injection efficiency and beam lifetime.

The IR optimization goal is to maximally compensate for the nonlinearities between the crab sextupole pairs. To achieve this, local horizontal and vertical chromatic sextupole pairs in the IR are designed to satisfy the –I transfer condition, which allows for the correction of first-order chromaticity while minimizing the nonlinear effects they introduce. The phase advance between the chromatic sextupoles and the FF quadrupoles is finely tuned to correct second-order chromaticity and the Montague function at the crab sextupole locations. Sextupoles are placed at the first and second IP mirror points to correct third-order chromaticity [6]. Since the β-functions at these mirror points are small, the geometric aberrations they contribute are relatively minor.

Since the STCF collider rings have numerous components and effects that create significant nonlinearities—such as the fringe fields of the FF quadrupoles, higher-order kinematic terms in IP drifts, chromatic sextupoles, and crab sextupoles—comprehensively analyzing these nonlinearities becomes intractable. Consequently, deriving the dynamic aperture through traditional analytical or perturbative methods is impractical.

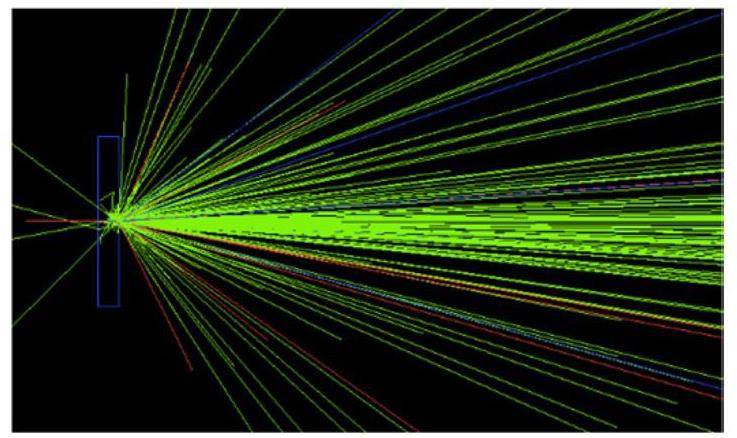

Instead, a common approach is to first construct simplified models to individually assess the influence of each nonlinear or high-order effect and propose targeted optimization strategies. Subsequently, professional software tools such as MADX, SAD, and Elegant are employed to perform 4D/5D/6D tracking and optimize the dynamic aperture.

To optimize the dynamic aperture and momentum acceptance, advanced techniques such as multi-objective optimization algorithms are used for the global nonlinear optimization of the collider rings, where the crab sextupoles are always enabled during the process. A total of 48 chromatic sextupole pairs per ring are used as optimization variables (6 in the IR and 40 in the arcs). First, a program called PAMKIT [8], developed by members of this project, is employed in conjunction with intelligent multi-objective optimization algorithms to optimize sextupole strengths. First-order chromaticity and key resonance driving terms are used as constraints, while the dynamic and momentum apertures are treated as direct optimization objectives to determine the best sextupole configuration.

Subsequently, the software SAD is used to precisely evaluate the dynamic aperture of the collider rings because it accurately models the nonlinear effects mentioned above and has been successfully applied to KEKB and SuperKEKB. In SAD, six-dimensional canonical variables (x, px, y, py, z, and δ) describe particle motion, where px and py are normalized transverse canonical momenta with respect to the design momentum p0 and δ is the relative momentum deviation. Tracking simulations include longitudinal oscillations, synchrotron radiation in all magnets, high-order kinematic effects, finite-length effects of sextupoles, and crab sextupoles. Quantum excitation and Maxwellian fringe fields in quadrupoles are disabled. The number of tracked turns corresponds to one synchrotron radiation damping time.

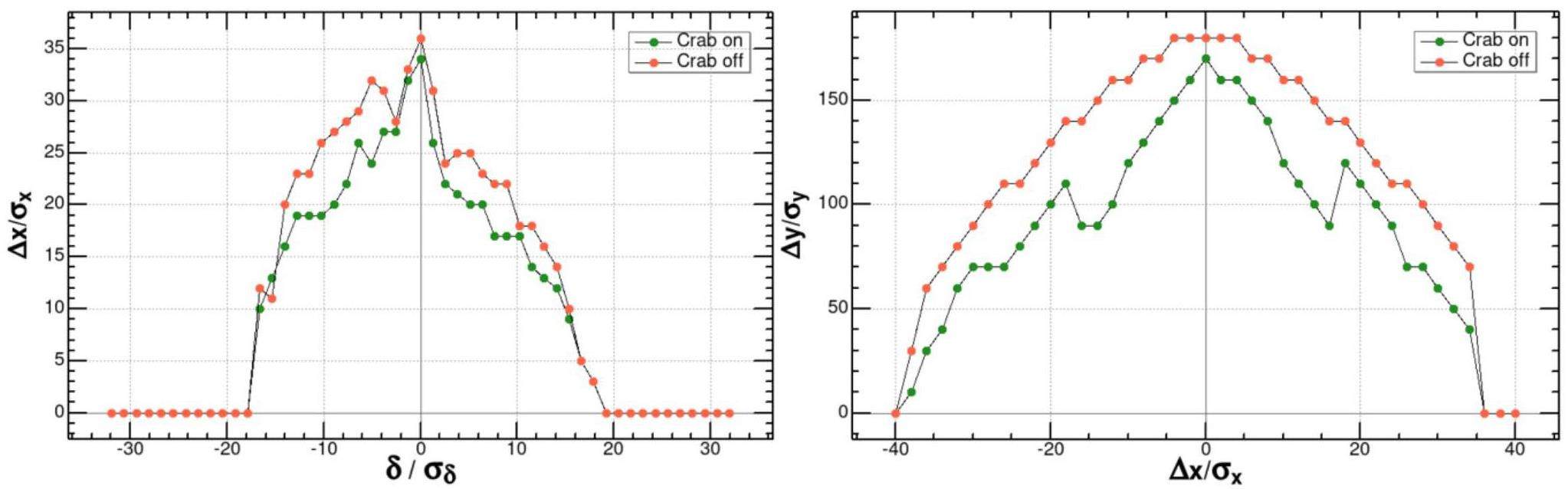

After optimization, the dynamic apertures with the crab sextupoles turned off and on are shown in Fig. 21. As the figure shows, when the crab sextupoles are turned off, the horizontal dynamic aperture reaches nearly

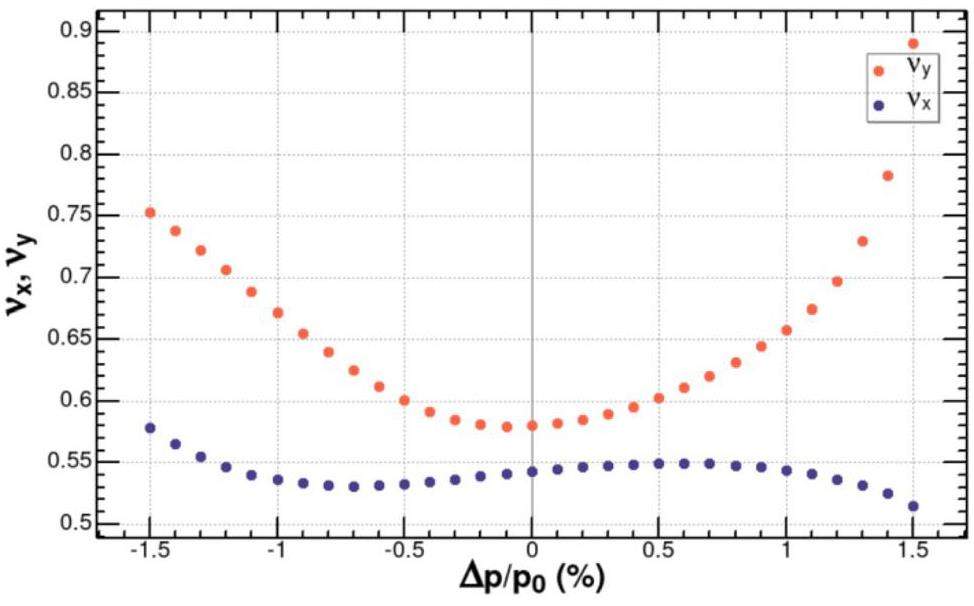

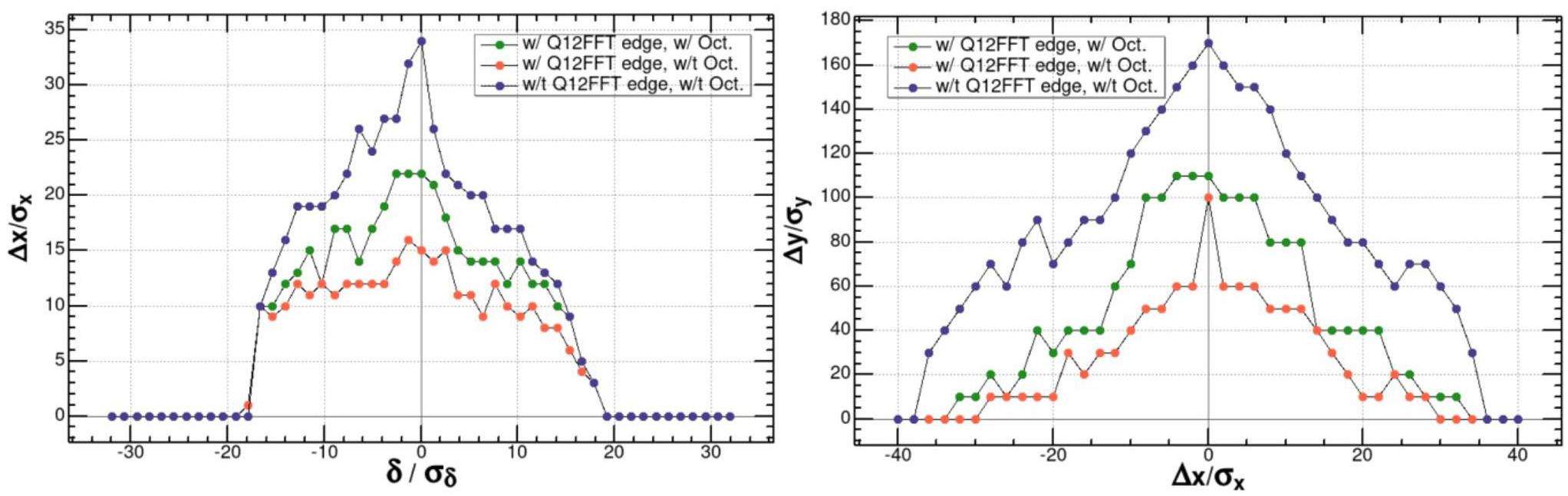

Fringe fields are present in all magnets and create nonlinearities that contribute to the reduction of the dynamic aperture. Analyzing the influence of Maxwellian fringe fields in dipole, quadrupole, and sextupole magnets using SAD showed that the fringe fields of the superconducting FF quadrupole magnets are dominant. Its effect on the dynamic aperture is shown in Fig. 23.

The second term in the Hamiltonian of the quadrupole fringe field resembles the form of the Hamiltonian of a thin octupole magnet. Therefore, octupole coils can be installed outside the FF quadrupole magnets to compensate for the fringe field effects of the FF quadrupoles. Figure 23 shows that the off-momentum and on-momentum dynamic apertures for the cases with and without the FF quadrupole fringe fields and with and without octupole compensation. All the cases have the crab sextupole switched on. The dynamic aperture with the FF quadrupole fringe fields decreases significantly compared to the case without the fringe fields; however, it can recover to some extent with the compensation of additional octupole coils. The optimization of the octupole coils remains ongoing to further recover the dynamic aperture.

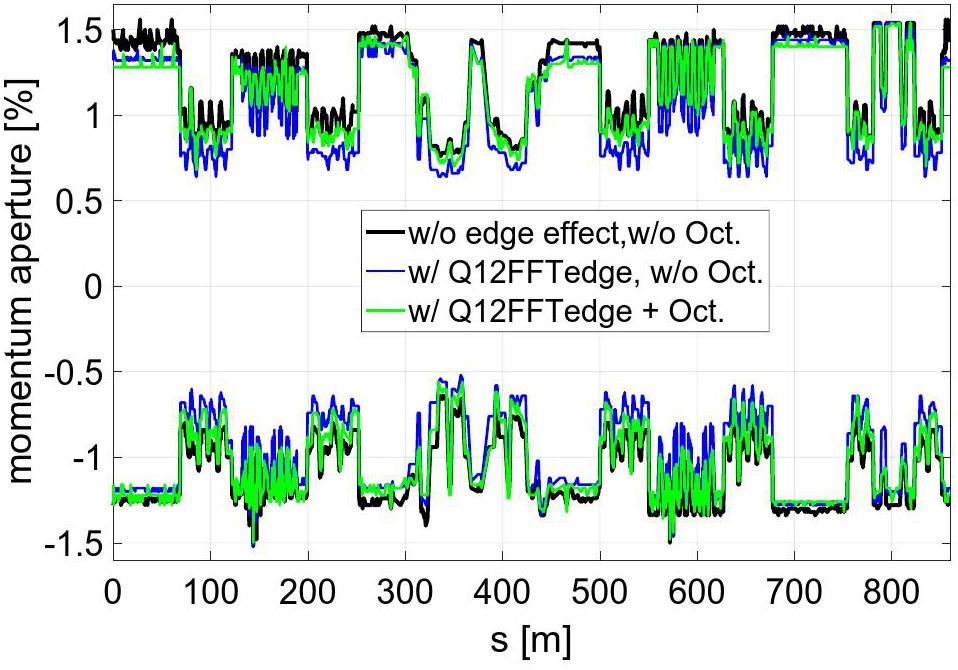

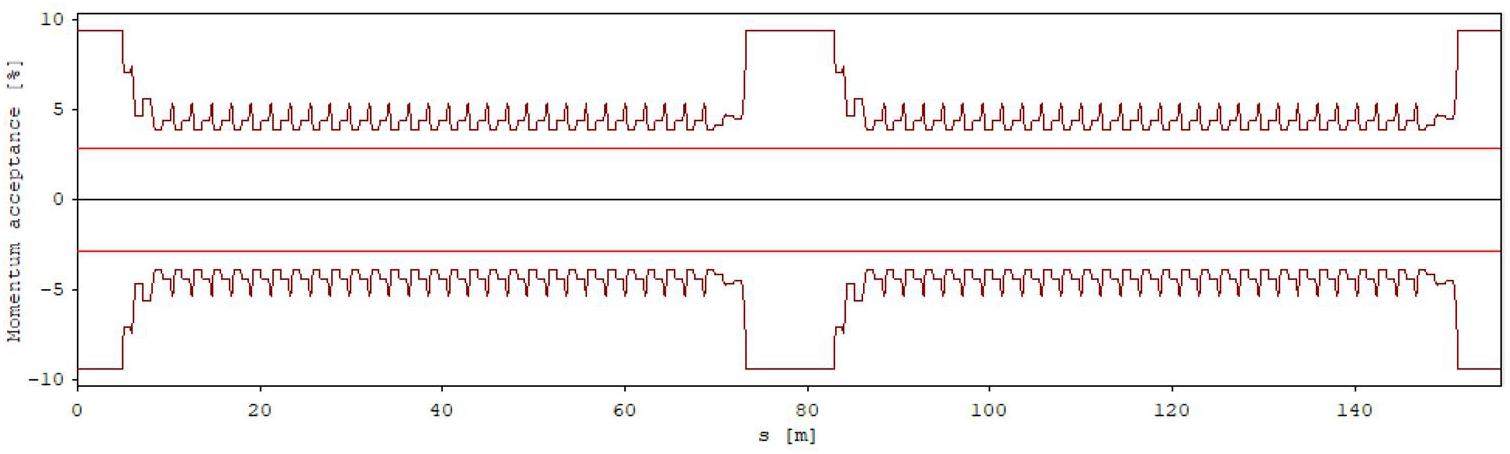

To further analyze dynamic aperture limitations, the Elegant program was utilized to track the local momentum acceptance (LMA) profiles around the entire ring with and without the FF quadrupole fringe fields and with and without octupole compensation. The results, as depicted in Fig. 24, indicate that the integration of the FF quadrupole fringe fields significantly degrades the LMA performance compared to the idealized fringe-field-free scenario. With octupole compensation, the LMA demonstrates remarkable recovery. The minimum LMAs under positive and negative momentum deviation are approximately 0.7% and 0.6%, respectively. The IR (between 300 m and 450 m in the figure) remains the critical bottleneck for the ring’s global momentum acceptance.

The solenoid field of the detector contributes to the vertical emittance growth in two main ways: the longitudinal Bz field directly induces horizontal x-y coupling, while the fringe radial field Bz introduces vertical dispersion. Consequently, careful compensation is required. The general principles for compensation are as follows: (1) the integral of the longitudinal Bz field must be zero; (2) within the region of the superconducting quadrupole magnets, the Bz field must vanish; (3) the integral of the radial fringe field of the solenoid should be maximally compensated. The focusing effect of the solenoid on the IR optics can be compensated by adjusting the strength of the FF quadruples. Preliminary studies show that the dynamic aperture can be fully recovered when the detector solenoid field is perfectly compensated.

At the beam energy of 2 GeV and peak luminosity of 1 × 1035 cm-2s-1 (with crab sextupoles activated), simulations using SAD and Elegant programs yield Touschek lifetimes of 325 s and 304 s, respectively, when the fringe field effects are neglected. Both values meet the design goal of exceeding 200 s lifetime at the target luminosity of 5 × 1034 cm-2s-1. When incorporating FF quadrupole fringe field effects, which typically introduce nonlinear distortions that reduce dynamic aperture, the uncompensated Touschek lifetime drops to approximately 150 s. However, after implementing compensation with octupoles, the lifetime recovers to approximately 250 s, maintaining compliance with the 200 s operational requirement.

To further improve the Touschek lifetime, additional nonlinear optimization strategies are required to enlarge the LMA. These include further optimization of nonlinearities in the collision region, the adoption of new nonlinear optimization strategies (such as those based on resonance driving terms and their fluctuations), and the inclusion of phase advances between different regions (such as between the IR and arc sections or between adjacent arc sections) as tuning variables.

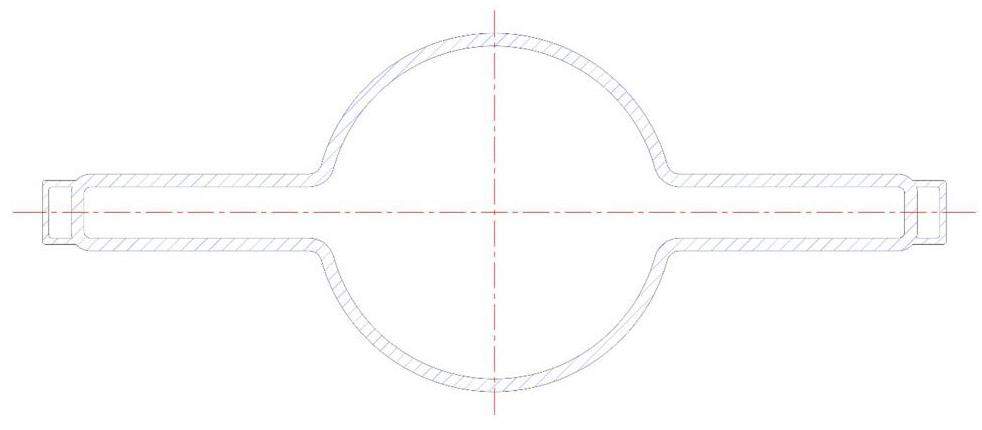

Longitudinal beam dynamics

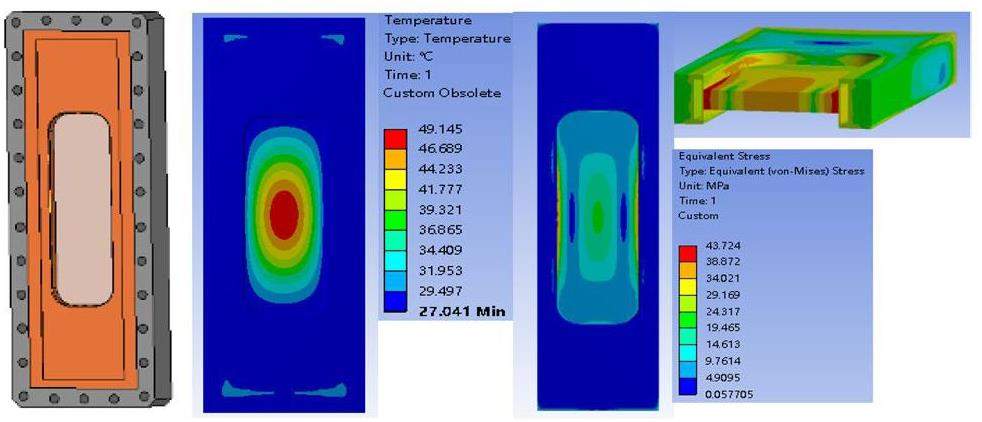

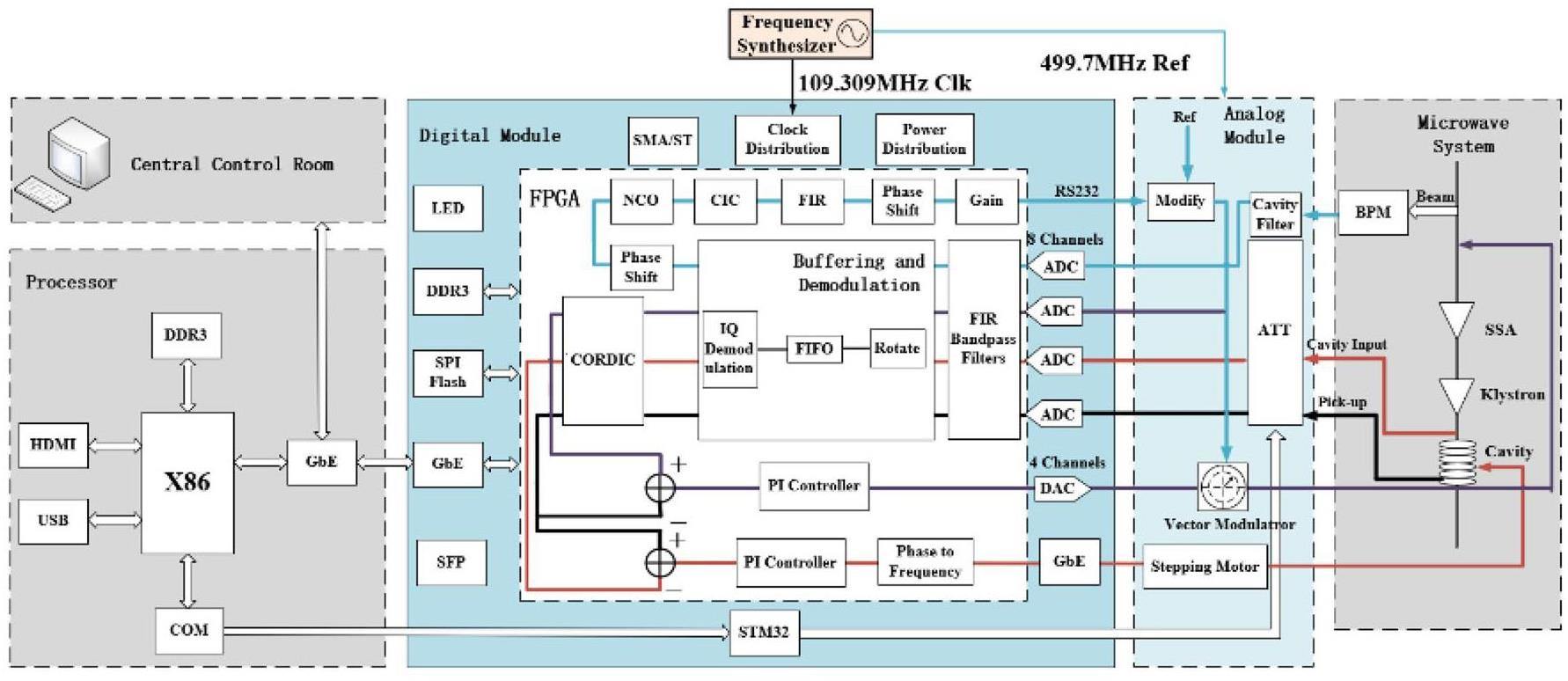

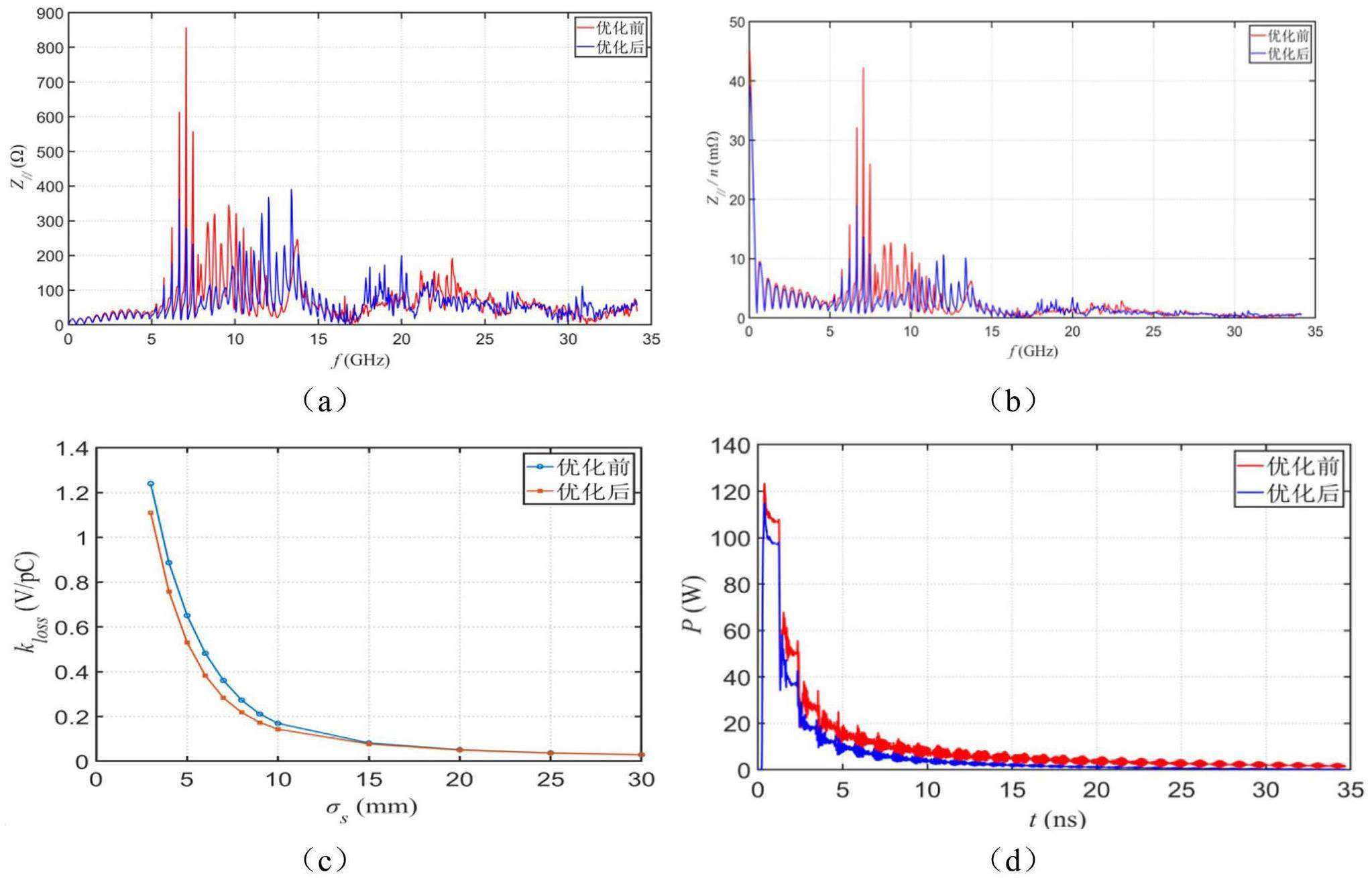

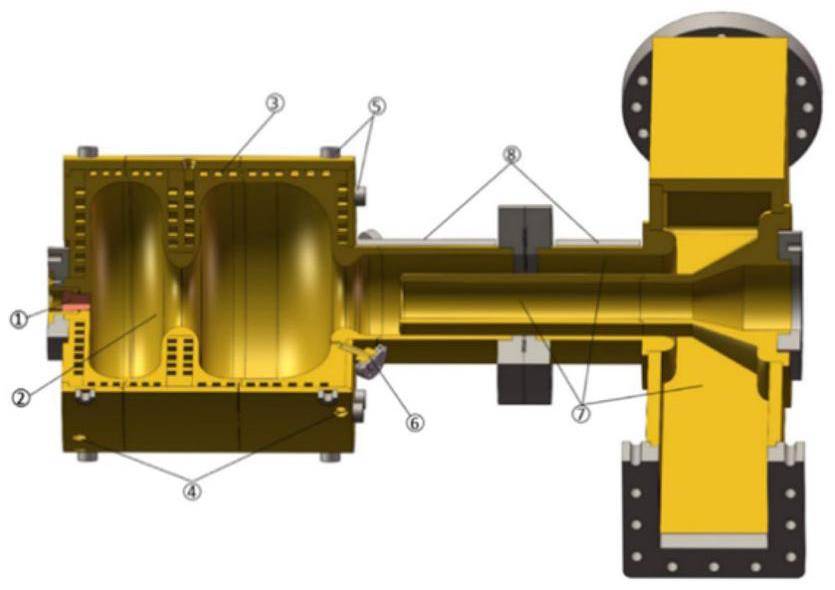

Challenges of longitudinal beam dynamics of electron storage rings with ampere-order target beam currents, such as the STCF collider rings, stem from longitudinal coupled-bunch instabilities due to the fundamental and parasitic modes of RF cavities [18]. The RF cavity scheme must meet both specific voltage and power requirements and effectively suppress these coupled-bunch instabilities. STCF is designed to adopt 500 MHz TM020-type room-temperature main RF cavities. Compared to conventional TM010 cavities, TM020 cavities feature relatively higher quality factors (Q) and lower R/Q values. Therefore, for the same cavity voltage and power requirements, the total R/Q can be reduced by approximately half [19], effectively mitigating coupled-bunch instabilities driven by the fundamental mode. This makes it feasible to suppress such instabilities through relatively simple means, avoiding overly complex LLRF feedback system designs.

Table 4 presents the longitudinal beam dynamics parameters and corresponding RF parameters of STCF at three beam energies. For beams of 1 GeV & 1.1 A, 2 GeV & 2 A, and 3.5 GeV & 2 A, 2, 6, and 15 cavities, respectively, are required to meet both voltage and power demands, with some safety margins. Table 5 lists the fundamental mode parameters of the STCF TM020 cavity. These parameters are primarily used to evaluate the coupled-bunch instabilities induced by the accelerating mode.

| Parameter | Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Beam energy, E (GeV) | 2 | 1 | 3.5 |

| Momentum compaction factor, αp (×10-4) | 13.49 | 12.63 | 13.73 |

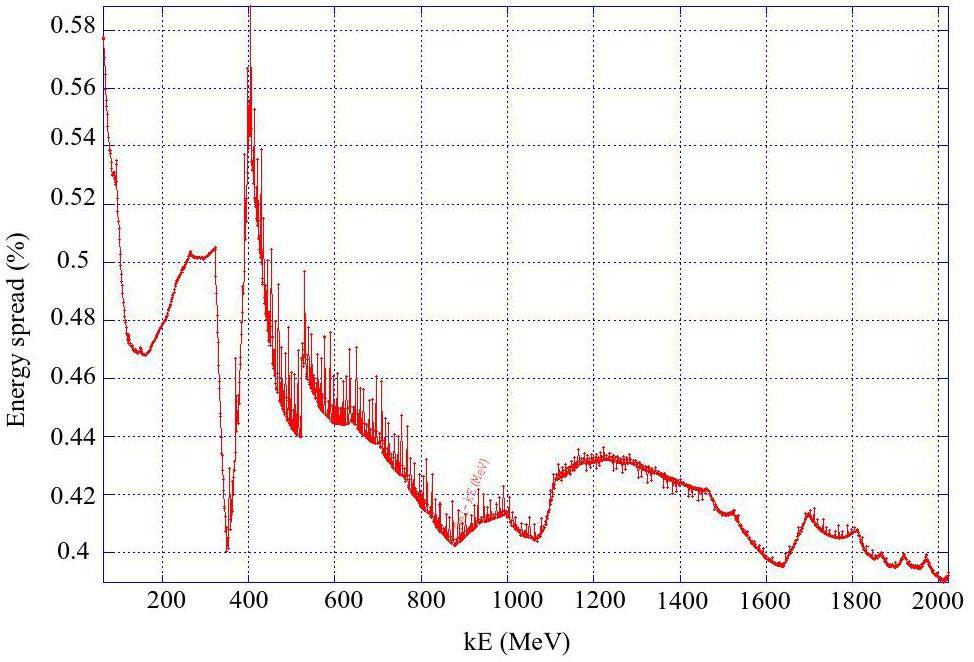

| Energy spread, σe (×10-4) | 7.8 | 6.18 | 10.02 |

| Beam current, I (A) | 2 | 1.1 | 2 |

| Bunch filling factor | 48% | ||

| Energy loss per turn, U0_sr (keV) | 543 | 106 | 1494 |

| Power loss per turn, P (kW) | 1086 | 117 | 2988 |

| Longitudinal damping time, τz (ms) | 10.57 | 27.07 | 6.72 |

| RF frequency, fRF (MHz) | 499.7 | ||

| Harmonic number, h | 1434 | ||

| Total RF voltage, VR (MV) | 2.5 | 1 | 7.5 |

| Number of RF cavities | 5 | 2 | 15 |

| Voltage per cavity (kV) | 500 | ||

| Power per cavity (kW) | 217 | 58.5 | 199.2 |

| Coupling factor | 4.71 | 2.33 | 5.5 |

| Detuning frequency (kHz) | –64.1 | –57.6 | –99.0 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Frequency (MHz) | 499.7 |

| R/Q=V2/(2P) | 47.5 |

| Q0 | 60,000 |

| R (MΩ) | 2.85 |

| QL (βopt=5.5) | 9230 |

TM020 accelerating mode stability analysis

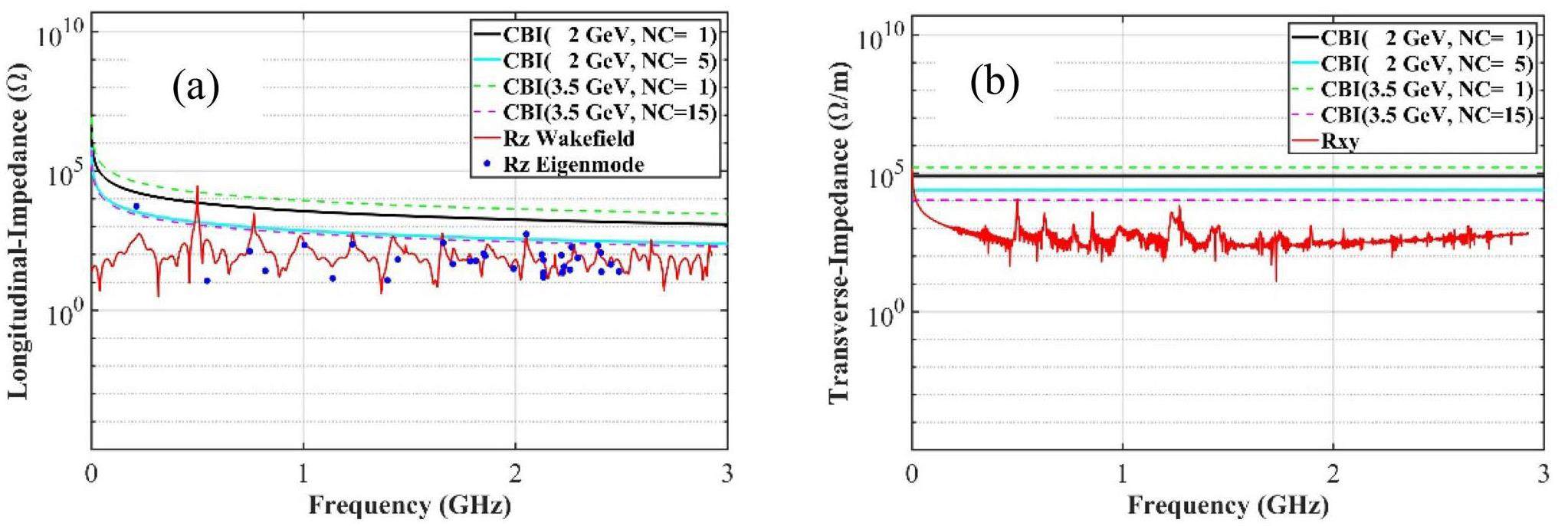

To analyze coupled-bunch instabilities due to the fundamental modes of RF cavities, the influence of low-level feedback must be considered since it modifies the impedance experienced by the beam [20]. Two common methods are used for evaluation: analytical calculations based on closed-loop cavity impedance and particle tracking simulations [21]. For the LLRF feedback, we only consider PI (proportional-integral) feedback based on I/Q signals. The closed-loop impedance of the cavity can be expressed as:

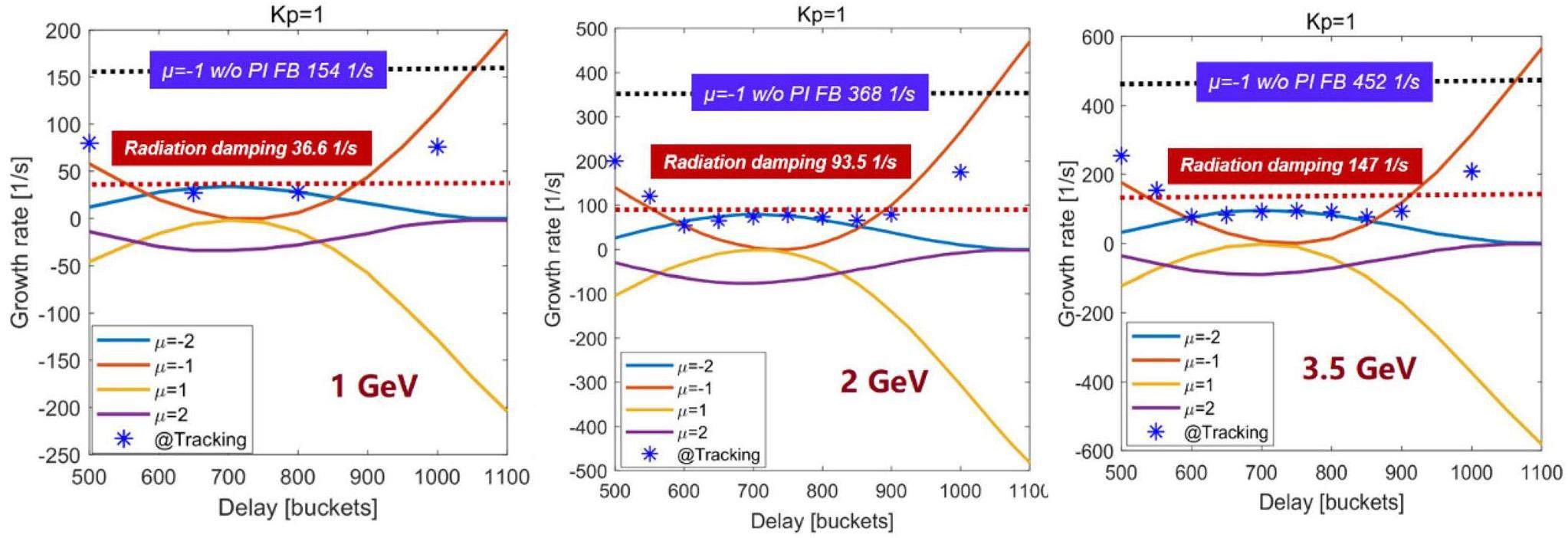

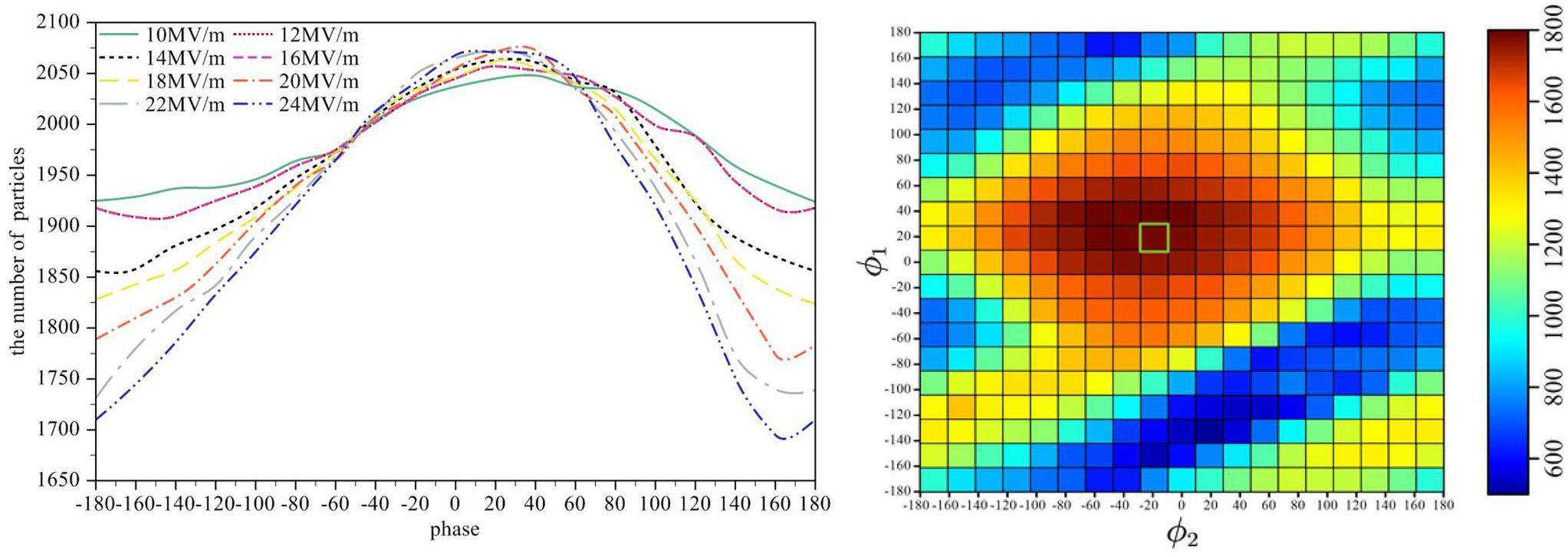

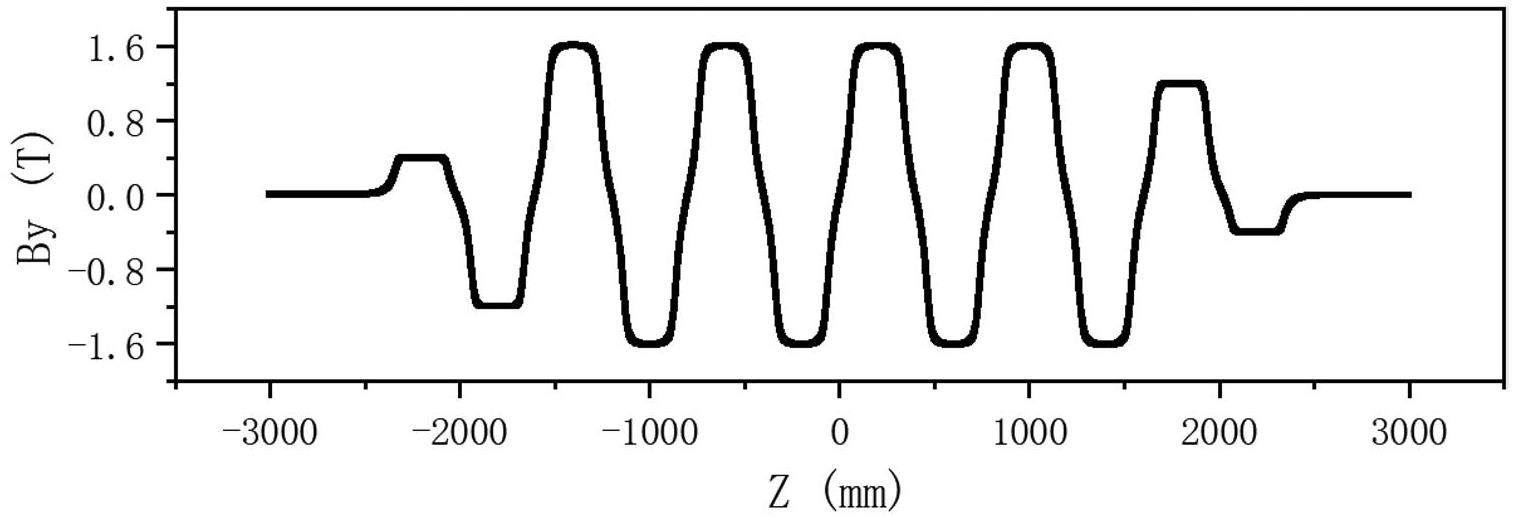

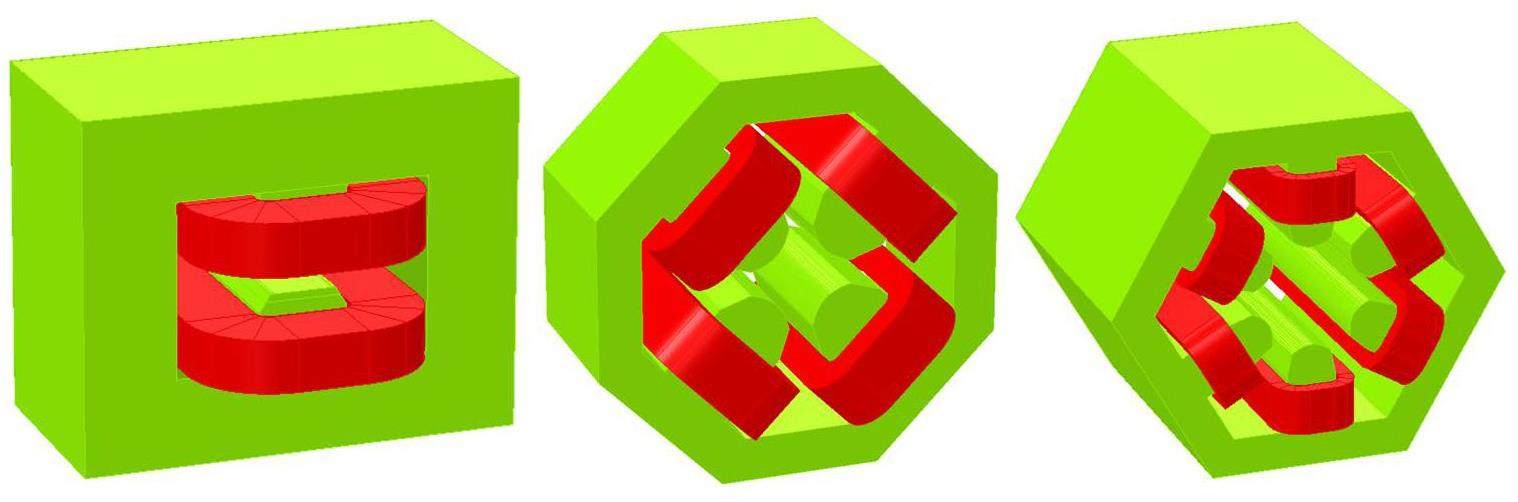

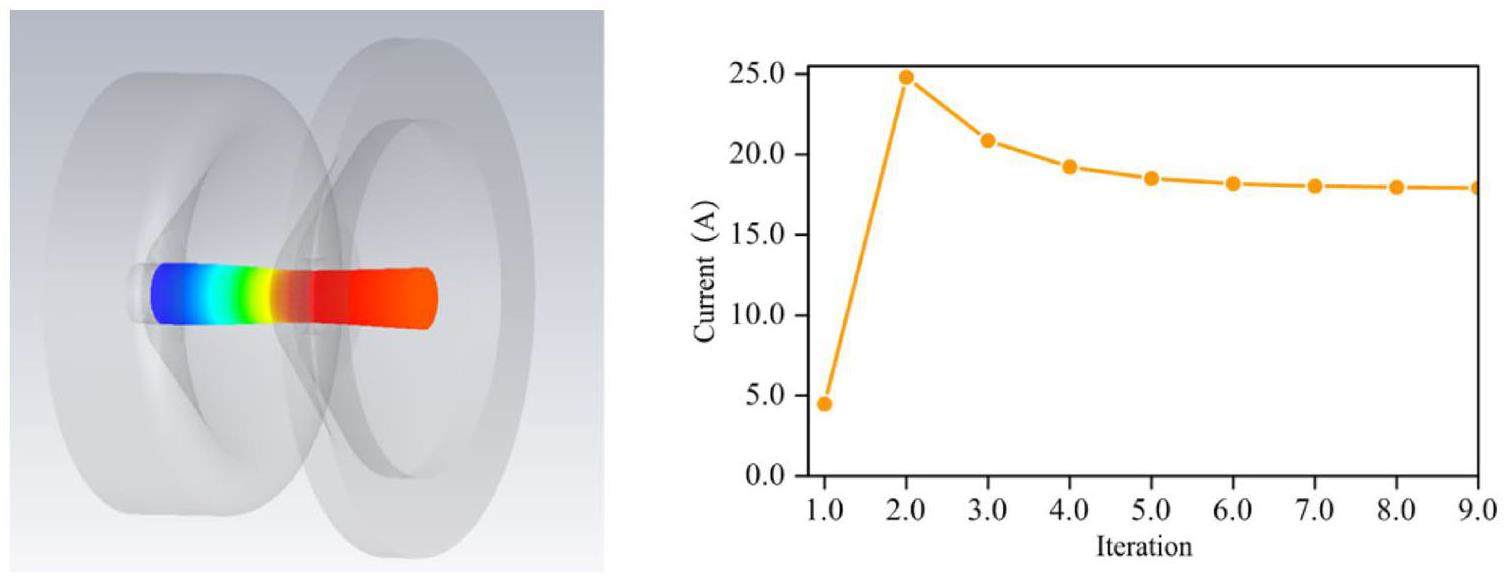

For STCF, by setting the appropriate proportional gain and delay time of the PI feedback, the –1 mode can be effectively suppressed and the –2 mode can be maintained below the threshold determined by synchrotron radiation damping, thus avoiding instabilities caused by the fundamental mode. Using the 2 GeV & 2 A beam case as an example, Fig. 25 shows the growth rates of major low-order modes obtained by both analytical and particle tracking methods for various proportional gains and delay times. Without PI feedback, the –1 mode has a growth rate of 368 s-1, which is much higher than the damping rate of 93.5 s-1. When

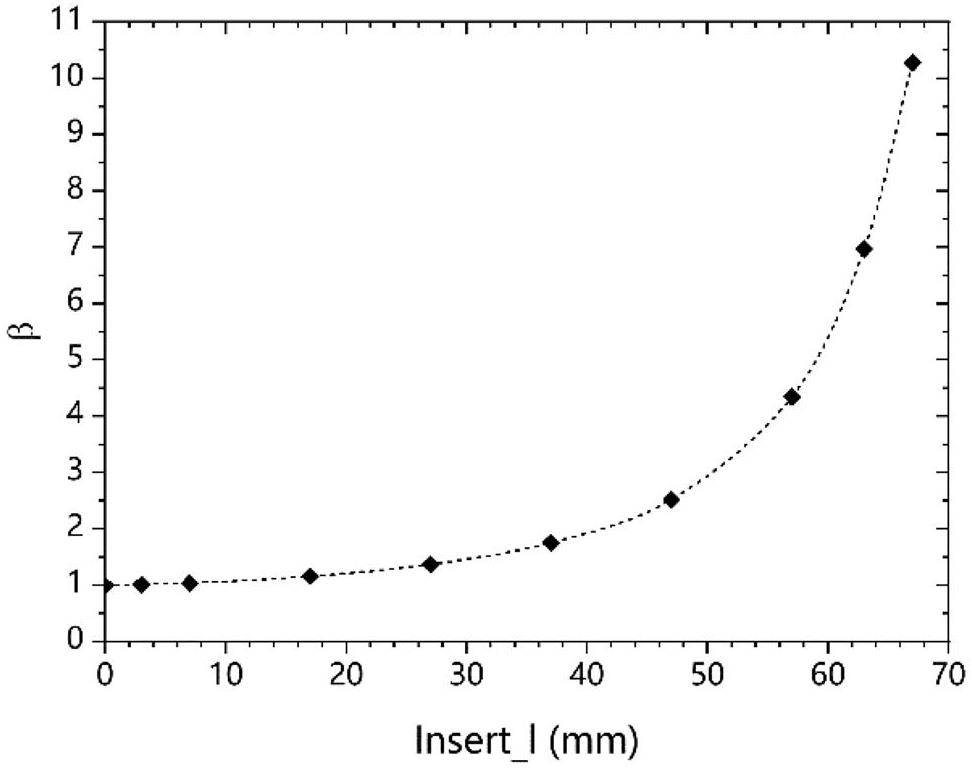

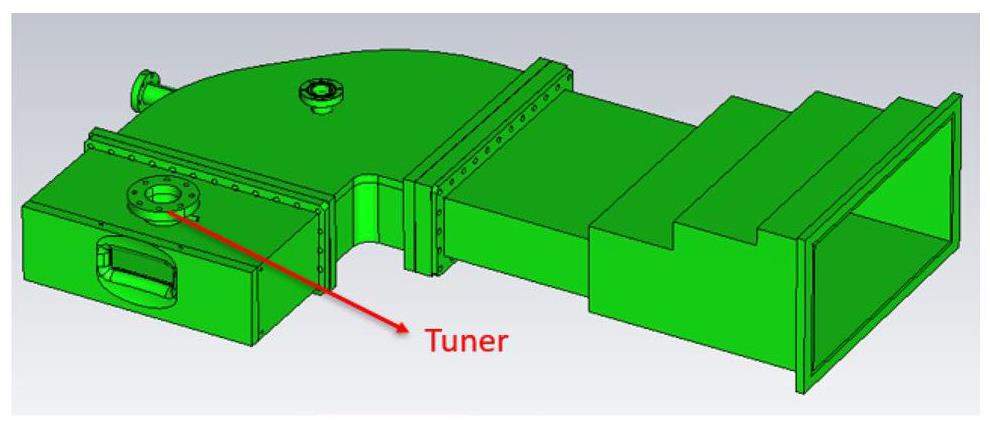

TM020 parasitic mode stability analysis

In the TM020 cavity, the TM020 mode is the accelerating mode, and modes with frequencies higher or lower than its nominal frequency are referred to as higher-order and lower-order modes, respectively. Both types can cause significant coupled-bunch instabilities. For simplicity, we refer to both as parasitic modes. To mitigate these instabilities, the cavity design must incorporate features that significantly suppress these parasitic modes. Assuming that beam spectral lines coincide with the resonance frequencies of parasitic modes, the associated coupled-bunch instability growth rate is typically calculated as

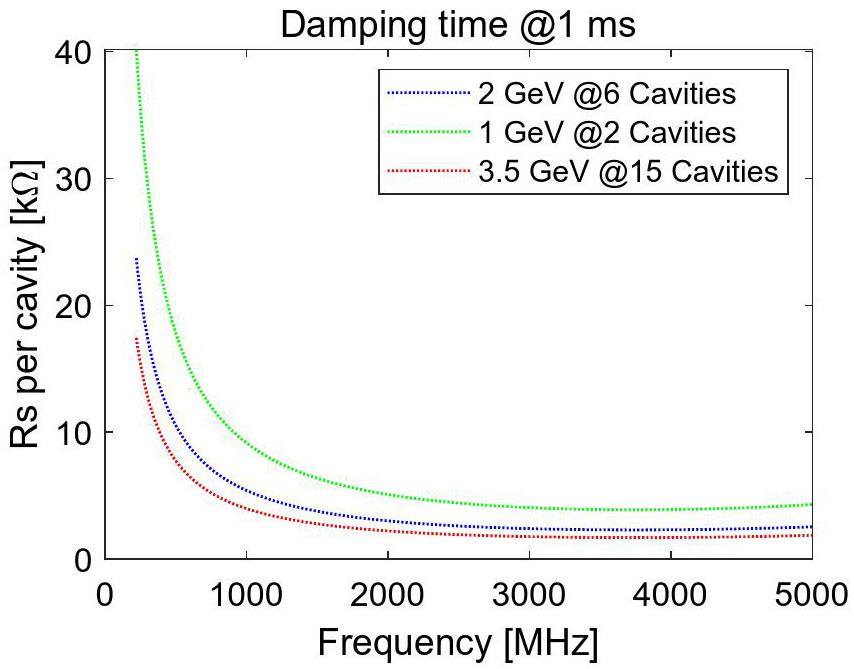

STCF has a synchrotron oscillation period less than 0.2 ms. Assuming that the longitudinal bunch-by-bunch feedback system has a conservative damping time of 1 ms, the impedance thresholds of parasitic modes are shown in Fig. 26. The threshold is lowest for 3.5 GeV because it uses the most cavities and assumes that all HOMs are aligned. Regardless, the lowest single-cavity threshold is 1.7 kΩ at 3.75 GHz, which is achievable for TM020 cavities.

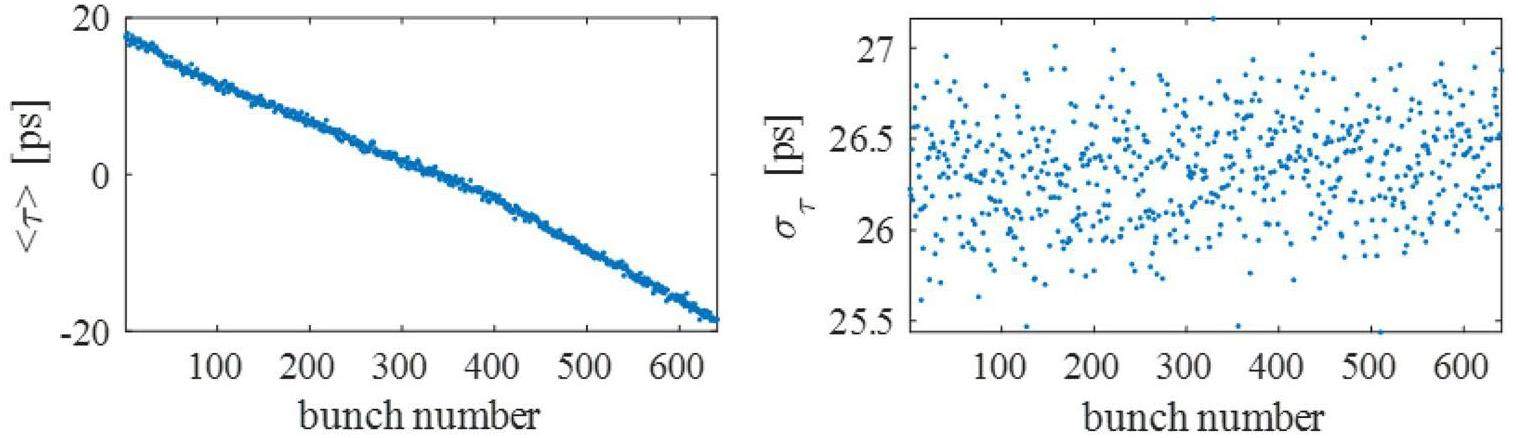

Transient beam loading effects

The 5% empty buckets reserved to suppress ion trapping introduce transient beam loading effects [22], resulting in bunch-to-bunch variations in synchronous phase and bunch length. Tracking simulations of this effect show the resulting distributions of bunch centers and lengths, as illustrated in Fig. 27. The effect on bunch length is minimal (within ± 1 ps), and variations in the bunch center remain within ± 20 ps, suggesting that the impact on luminosity is negligible.

STCF is designed to use the TM020-type room-temperature RF cavity scheme. Owing to its relatively low R/Q, complex feedback schemes (e.g., one-turn delay feedback and direct feedback) such as those adopted by the PEP-II collider are not necessary. The stability of the fundamental mode can be maintained by choosing the appropriate PI feedback gain and delay parameters, thereby significantly simplifying the LLRF system. Radiation damping alone is insufficient for damping coupled bunch instabilities caused by parasitic modes; a longitudinal bunch-by-bunch feedback system providing at least 1 ms of damping is required. From the perspective of the RF cavity design, suppressing parasitic modes below the instability threshold under such damping conditions is entirely achievable.

Beam–beam interaction and luminosity optimization

For a crab-waist scheme collider using flat beams (with transverse beam sizes at the IP satisfying

The luminosity can also be written as [24]

Based on operational experience, the vertical beam–beam parameter

Beam–beam interaction is a key factor in determining collider luminosity, beam stability, and beam lifetime. In third-generation high-luminosity colliders using the crab-waist scheme, where the beam current is high and emittance is small, the beam–beam effects are especially prominent. Experience from colliders such as DAFNE and SuperKEKB, as well as numerous theoretical and numerical studies, has shown that beam–beam effects are significantly coupled to other processes, such as lattice nonlinearities and impedance, which limits overall machine performance. Therefore, the severity of beam–beam interactions depends jointly on key beam parameters and the machine operating mode and must be optimized carefully to enhance performance. In addition to qualitative theoretical analysis, the detailed impact of beam–beam interactions on accelerator performance is mainly assessed through simulations. Weak-strong simulations require fewer computational resources and are suited for the wide exploration of the beam parameter space, such as tune, Twiss parameters at the IP, and machine tolerance to imperfections, serving as a foundation for strong–strong simulations. Strong–strong simulations, which are more computationally intensive, are used for localized studies of the beam parameter space and to evaluate beam stability. Weak-strong simulations mainly address incoherent collective effects, whereas strong–strong simulations focus on coherent instabilities involving both beams.

Simulation results and analysis

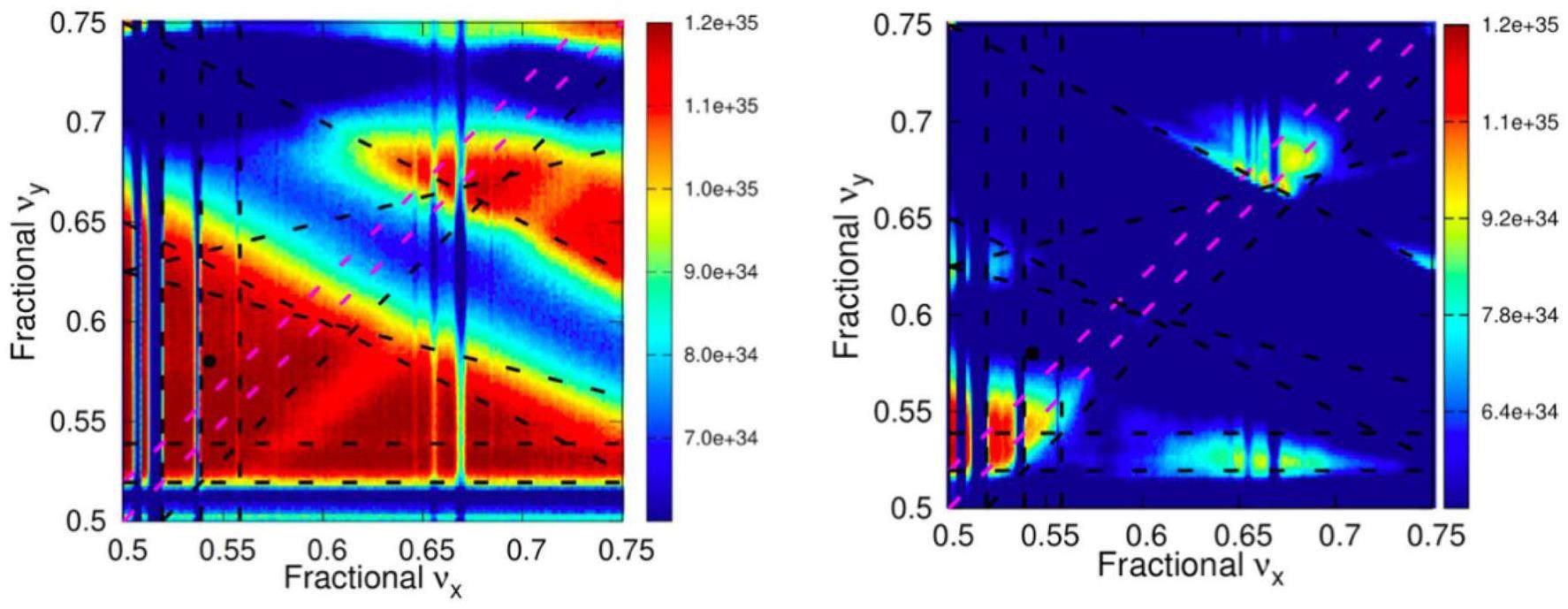

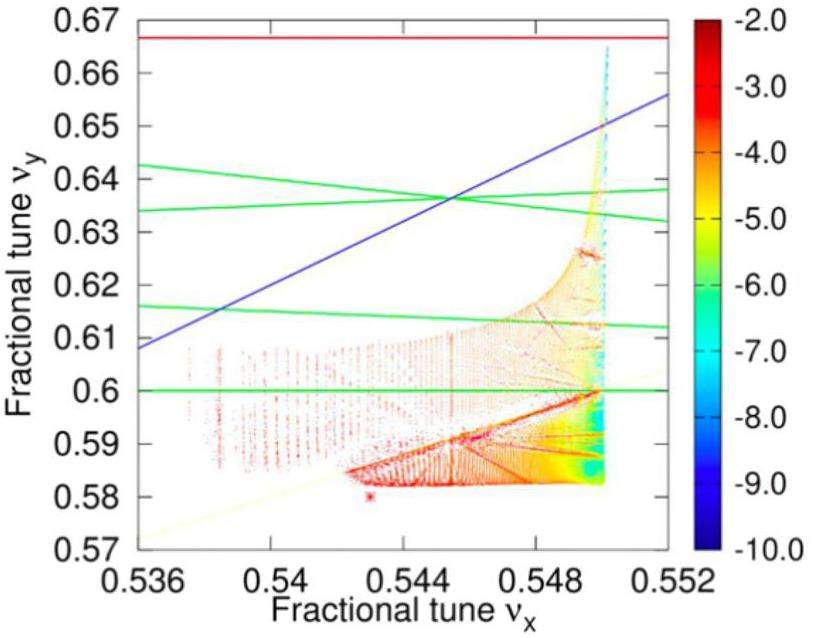

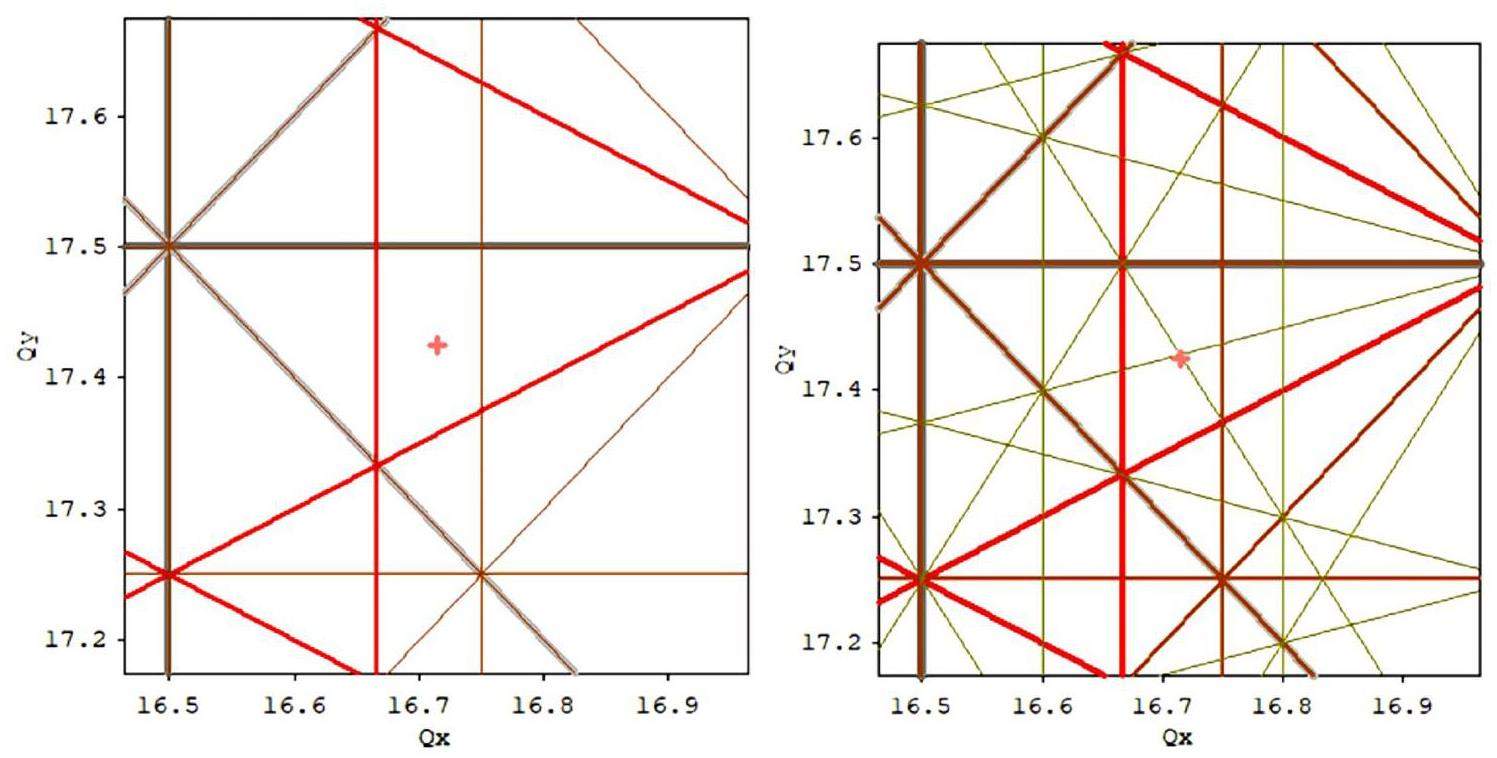

The working point in e+e- storage ring colliders is typically optimized near half-integer values to achieve maximum luminosity. The precise fractional tune values are optimized using beam–beam simulations. Figure 28 shows the luminosity versus working point calculated using the BBWS code for fractional tunes above the half-integer (beam energy is 2 GeV; other parameters refer to Table 1). Comparing the simulations with and without the crab-waist scheme reveals that the crab-waist can effectively suppress nonlinear betatron resonances induced by beam–beam effects, thus enlarging the high-luminosity region in the tune space.

However, Figure 28 also shows that the crab-waist scheme cannot suppress synchro-betatron resonances induced by beam–beam interactions. Similar to SuperKEKB, STCF chooses a relatively large synchrotron tune

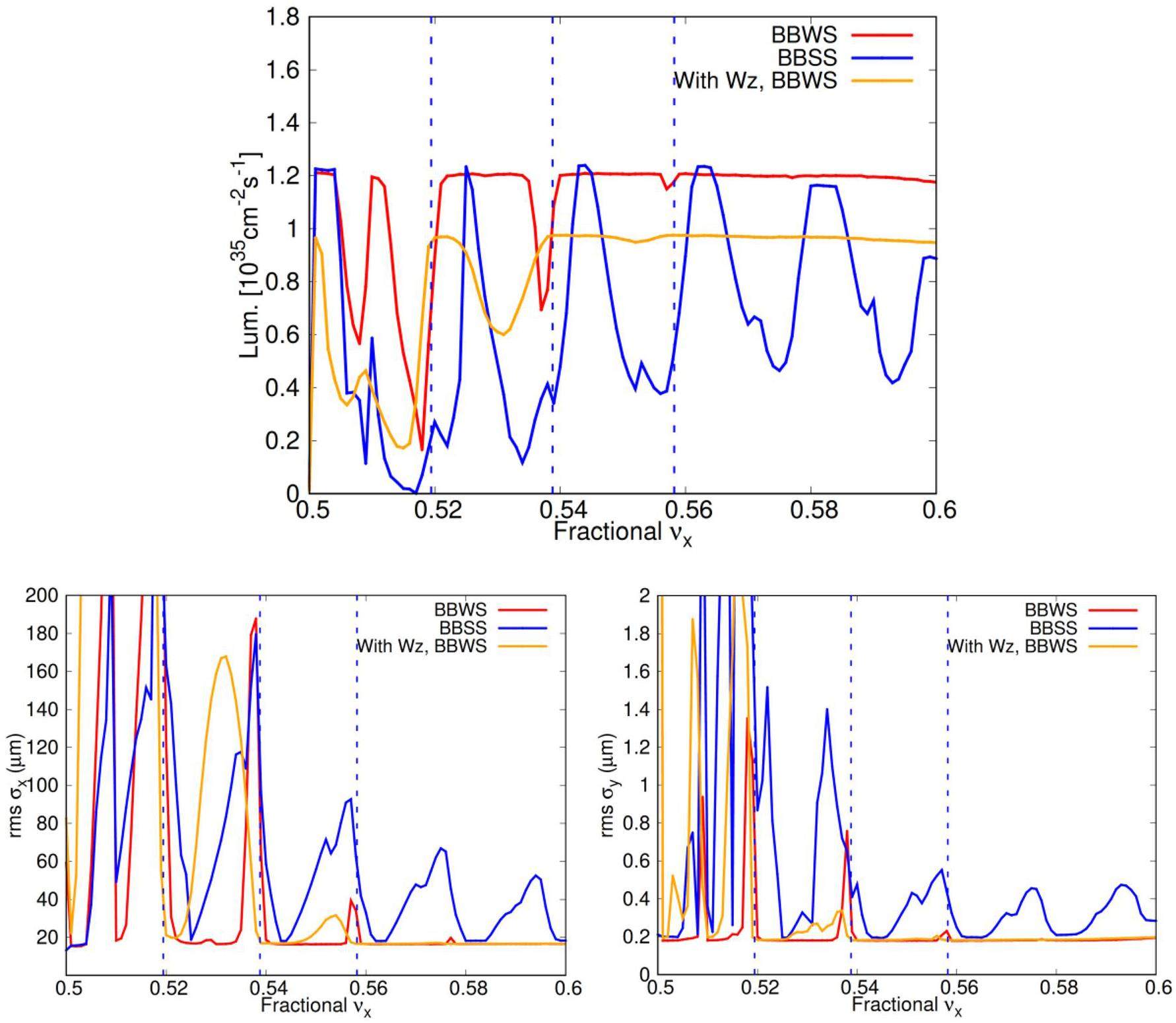

Coherent X-Z instabilities are evaluated using strong–strong beam–beam simulations. Figure 30 shows the results of scanning the horizontal tune (with vertical fractional tune fixed at 0.58) using the BBWS and BBSS codes. The results indicate that a horizontal tune near 0.543 avoids coherent X-Z instability. The strong–strong simulations suggest that the range of horizontal tune values for achieving high luminosity is narrow and can be widened by increasing the synchrotron tune

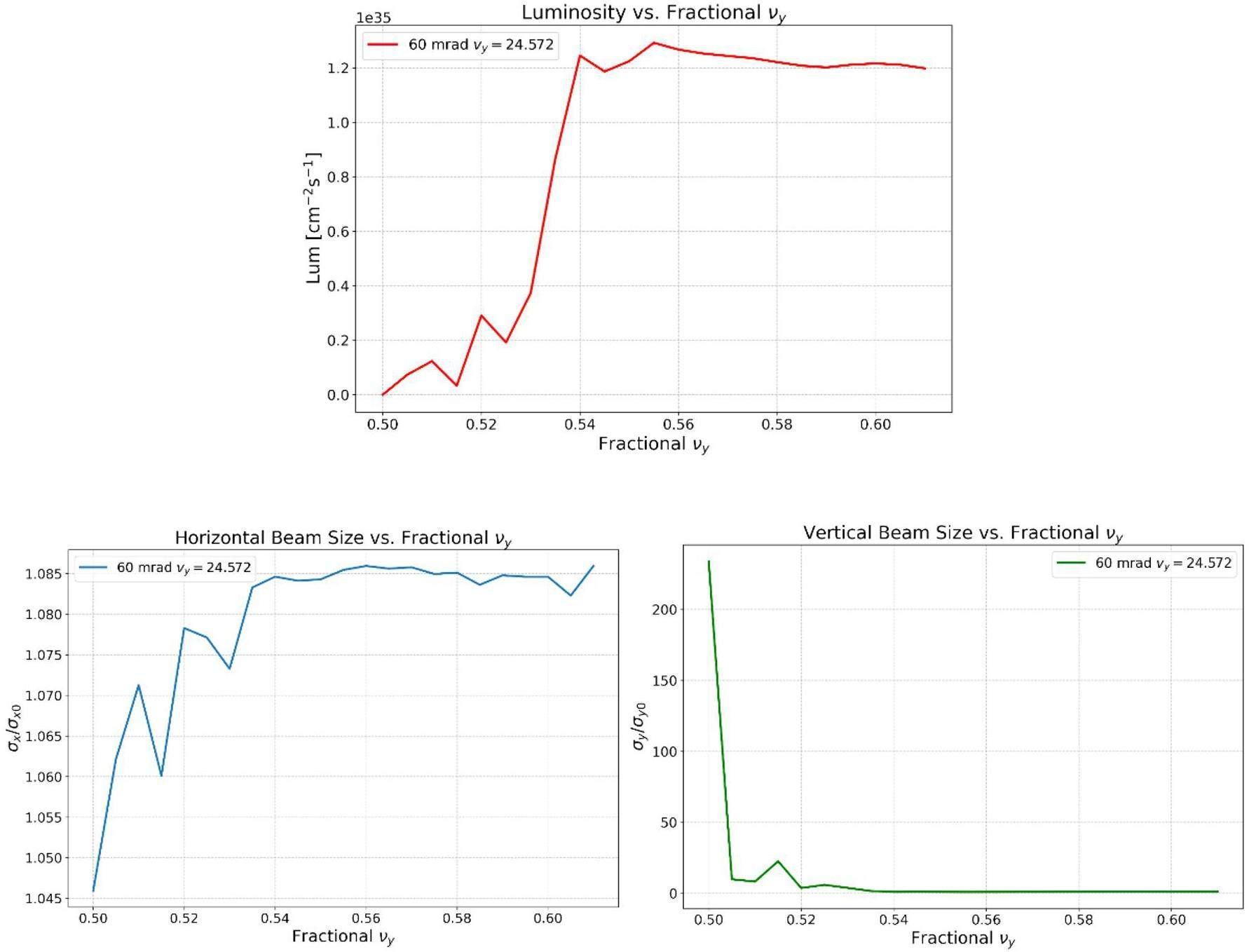

Fixing the horizontal fractional tune at 0.543, vertical tune scans were performed using BBSS. Figure 31 shows that the vertical fractional tune should be greater than 0.56 and that luminosity and transverse beam sizes are relatively insensitive to vertical tune within this range.

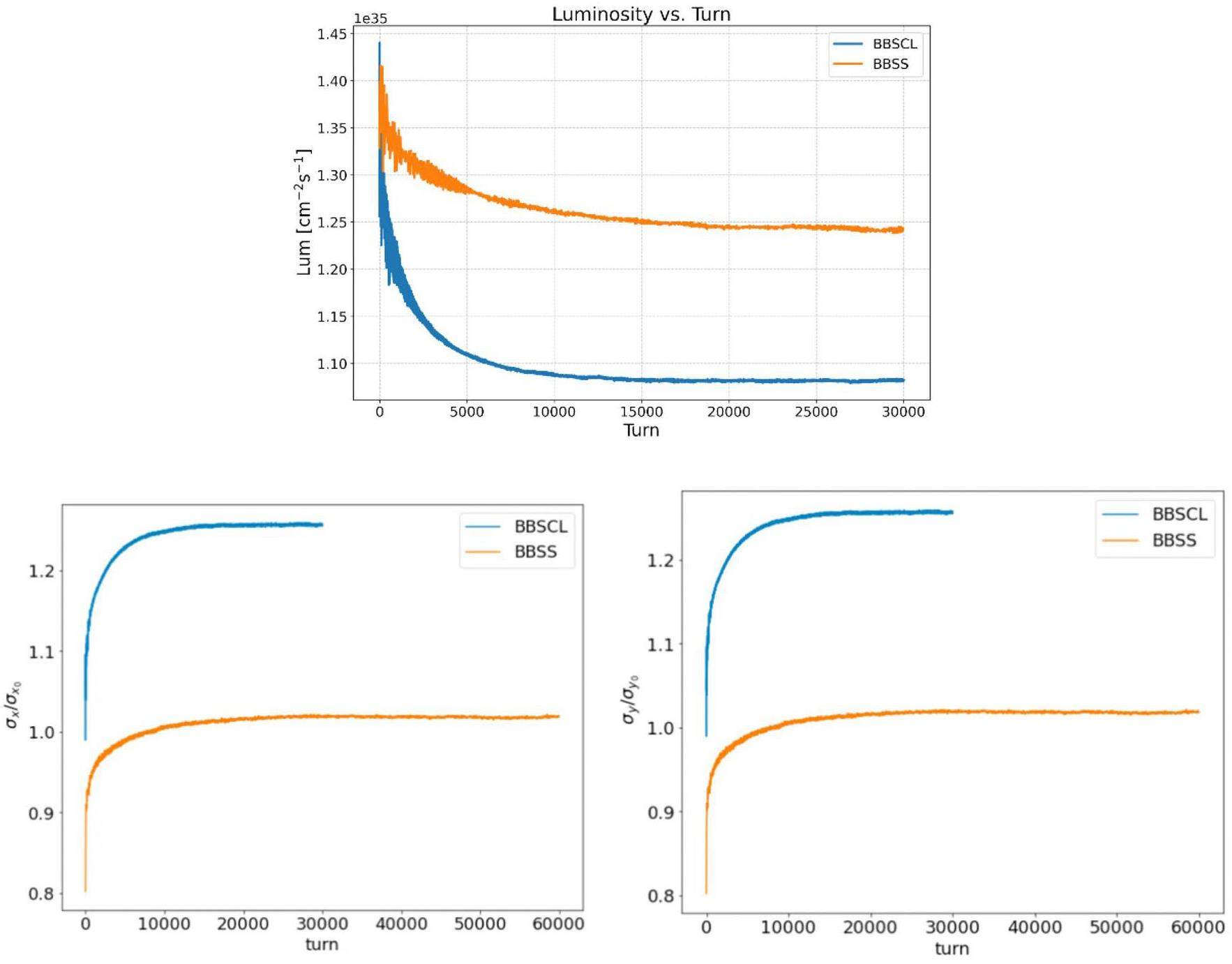

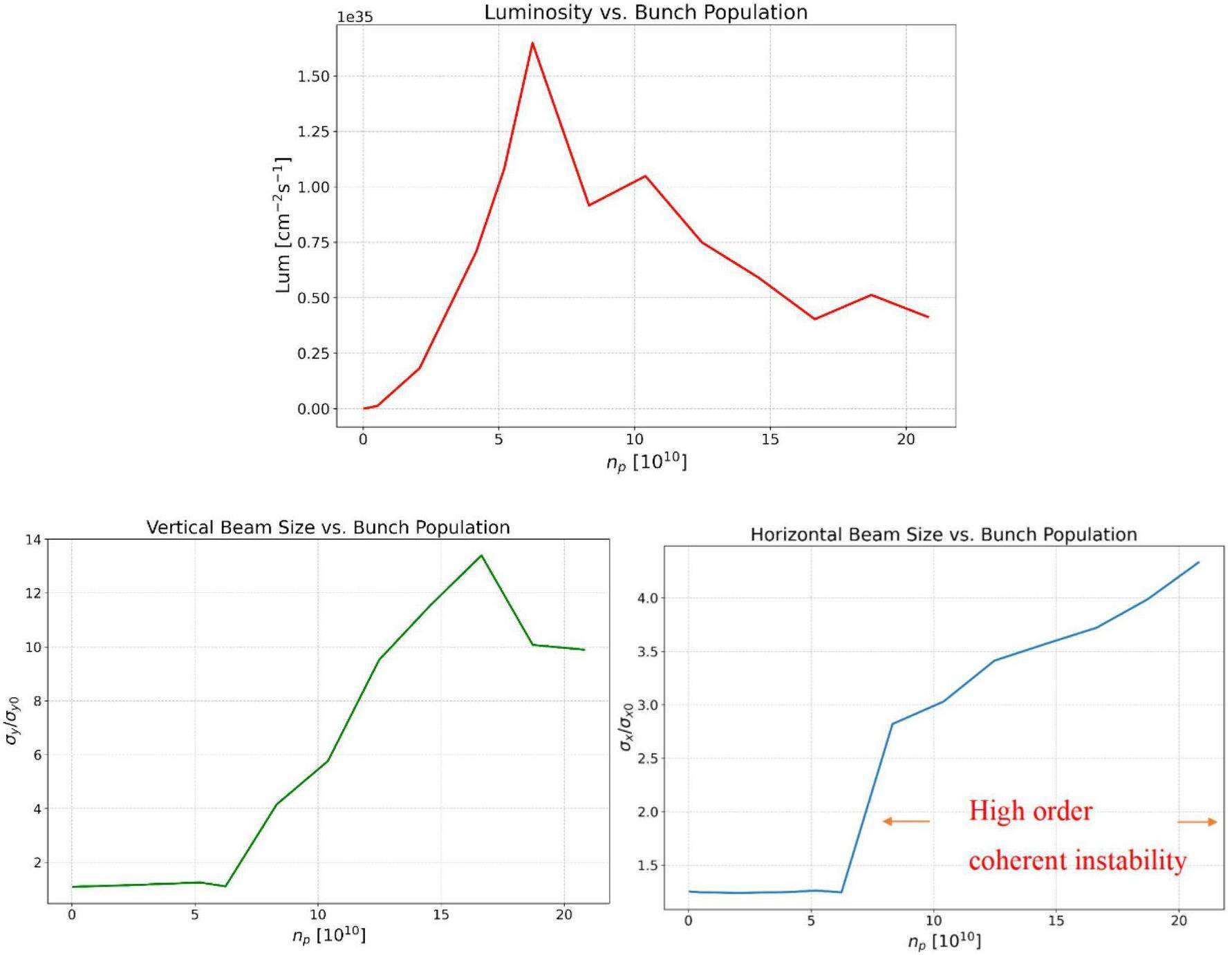

Simulations considering lattice nonlinearities (for details of lattice design, see Sect. 2.2) were performed using the BBSCL code and compared with the BBSS results. As shown in Fig. 32, coupling between lattice nonlinearities and beam–beam effects affects luminosity, with the extent depending on specific lattice design details. This highlights the need for deeper lattice nonlinearity studies and optimization. Additionally, BBSCL was used to scan the single-bunch current with the lattice included. Figure 33 shows that coherent instability occurs when Np exceeds 6.2×1010, above the nominal value of 5.2×1010.

Coupled effects of multiple physical mechanisms

The coupling of multiple physical mechanisms is particularly pronounced in colliders employing the crab-waist collision scheme, which significantly increases the complexity of machine design and the difficulty of achieving high-luminosity operation. In addition to the previously discussed couplings between beam–beam interactions, lattice nonlinearities, and impedance effects, several other factors warrant further investigation.

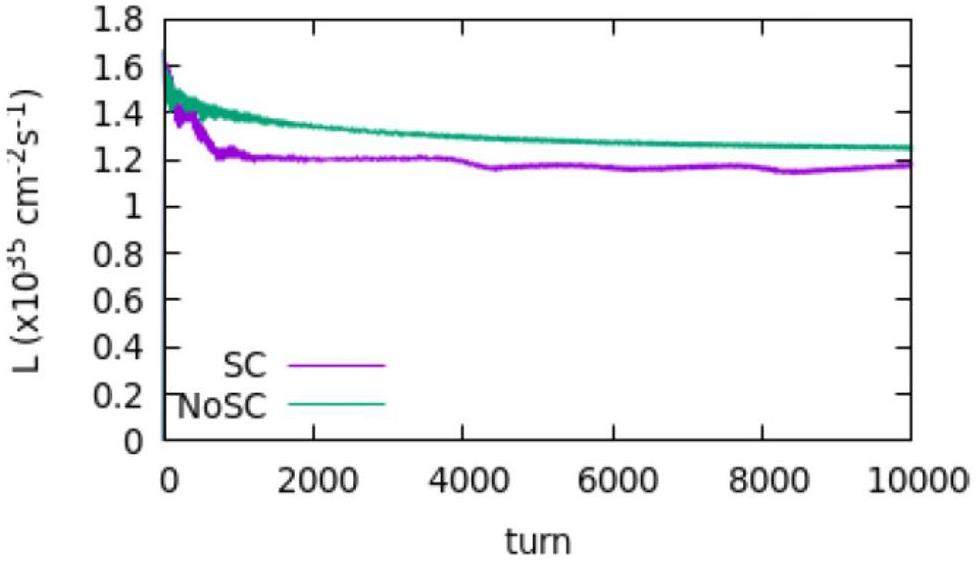

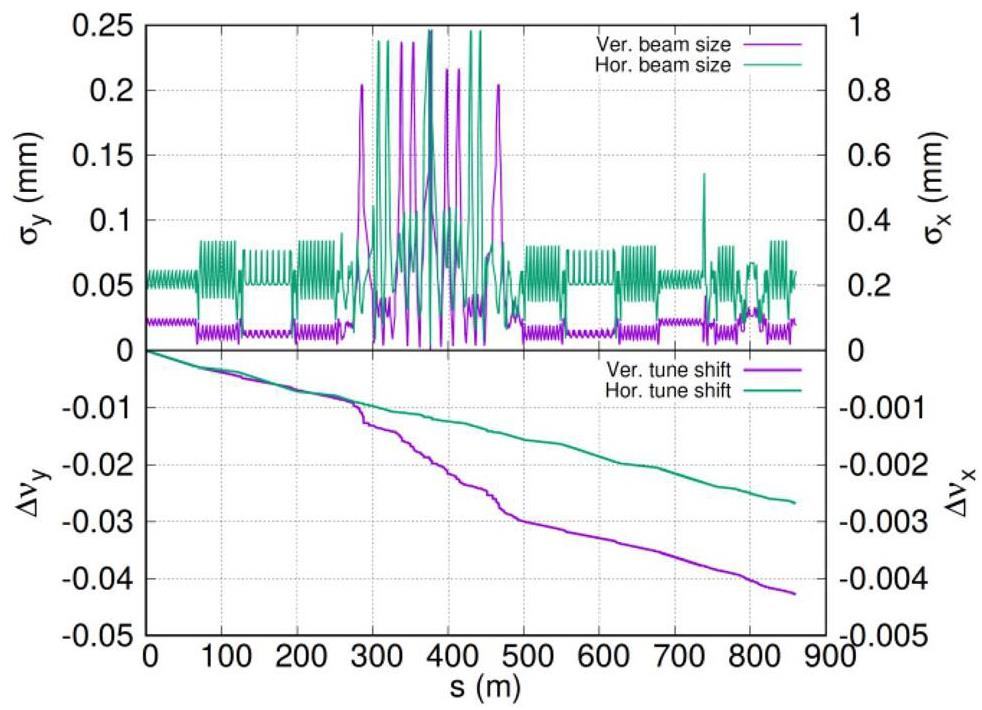

· Space charge (SC) effects: Under high-current conditions, the Coulomb field generated by the beam has a non-negligible influence on particle motion. According to the latest STCF lattice design and beam parameters, SC effects induce vertical and horizontal tune shifts of approximately −0.043 and –0.0027 (see Fig. 34), which are opposite the shift caused by beam–beam interactions. As this effect is distributed along the entire ring and influenced by the alternating-gradient focusing structure, its overall impact cannot be simply canceled by beam–beam tune shifts and thus cannot be directly utilized to enhance luminosity. Beyond simplified particle tracking models, a more comprehensive assessment requires full-ring tracking simulations incorporating the actual lattice structure. These simulations are being actively performed using the BBSCL code with full-lattice and SC effects. A preliminary luminosity result under the design beam parameters is shown in Fig. 35. Analysis of the simulation data reveals a notable luminosity degradation and is attributed to a weak coherent X-Z instability. This instability is primarily associated with the horizontal tune shift induced by SC (its absolute value is comparable with the horizontal beam–beam tune shift), rather than the vertical component. The horizontal tune shift moves the beams closer to the broad resonance peaks of the coherent X-Z instability, as illustrated in Fig. 30 under current machine conditions.

· Impedance effects: In addition to the longitudinal impedance effects discussed earlier, transverse impedance can also couple with beam–beam interactions and induce coherent mode-coupling instabilities. These instabilities are closely related to the vertical tune and thereby constrain the accessible working point space. A comprehensive impedance budget for STCF is currently under development. The combined impact of impedance and beam–beam interactions will be systematically investigated in future studies.

· Imperfections in the IP optics: These include non-zero coupling and dispersion at the IP, phase deviations between the IP and the crab-waist sextupoles, and orbit errors at both the IP and sextupole locations. Such imperfections can undermine the effectiveness of the crab-waist mechanism and consequently degrade the achievable luminosity.

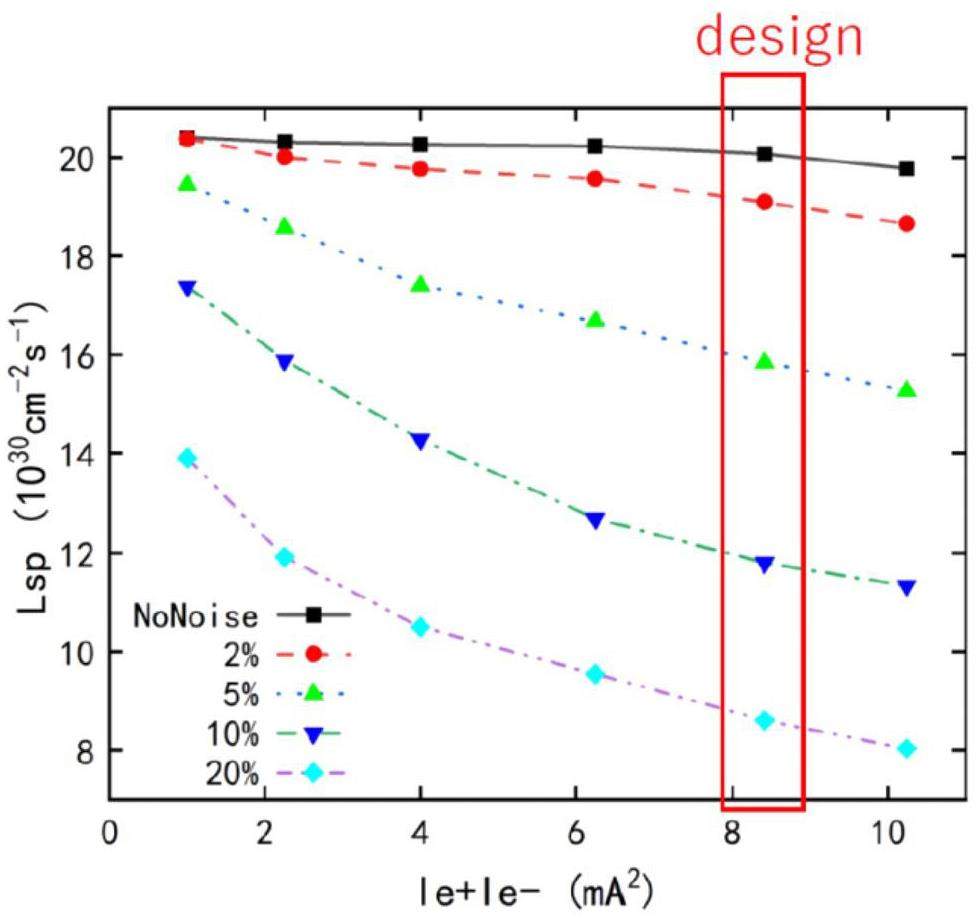

· Noise in the bunch-by-bunch feedback system: Under high-current operating conditions, the machine’s reliance on the feedback system for suppressing coherent instabilities increases significantly. However, because of the extremely small transverse beam sizes at the IP, noise in the feedback system may excite beam motion and contribute to luminosity degradation. To evaluate this effect, simulations using the BBSS code were performed, incorporating turn-by-turn noise modeled as vertical collision offsets at the IP with a standard deviation of

· Other collective effects: Phenomena such as electron clouds and ion trapping may also pose potential performance limitations for the machine.

Recently, GPU-accelerated codes (e.g., BBSCL at KEK, APES-T at IHEP, and Xsuite at CERN) have enabled more efficient simulations of coupled multi-physics effects. In the future, further STCF beam–beam studies will rely heavily on these advanced tools.

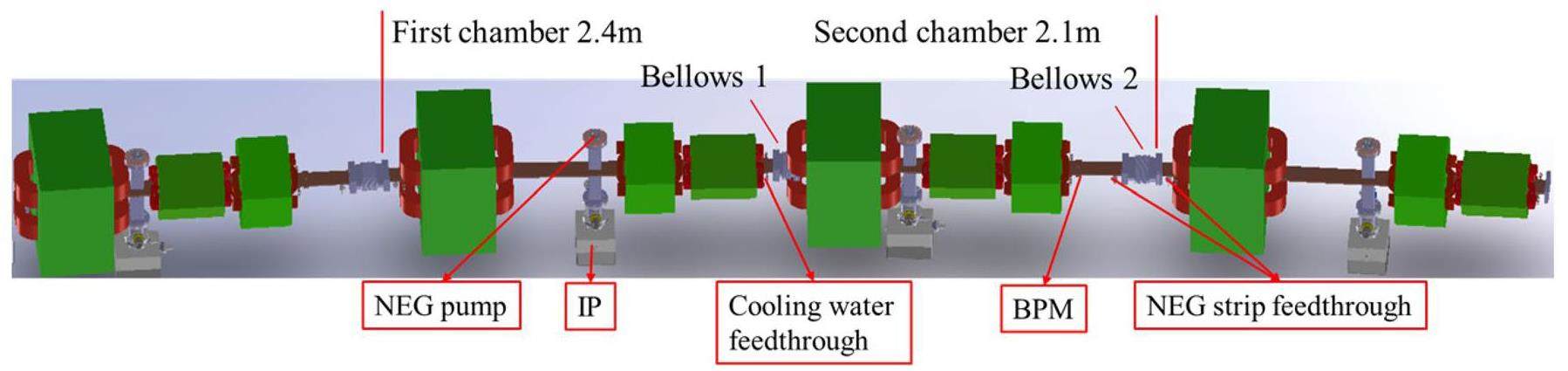

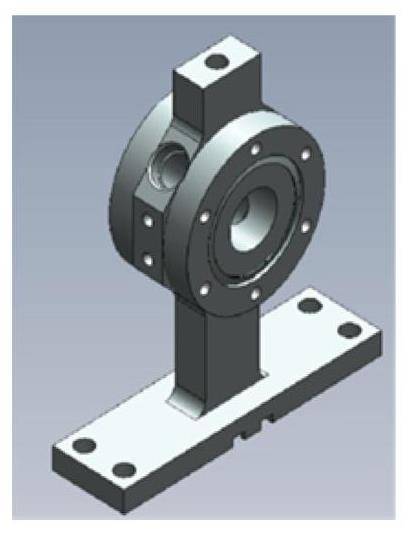

Impedance and beam collective effects

Collective effects

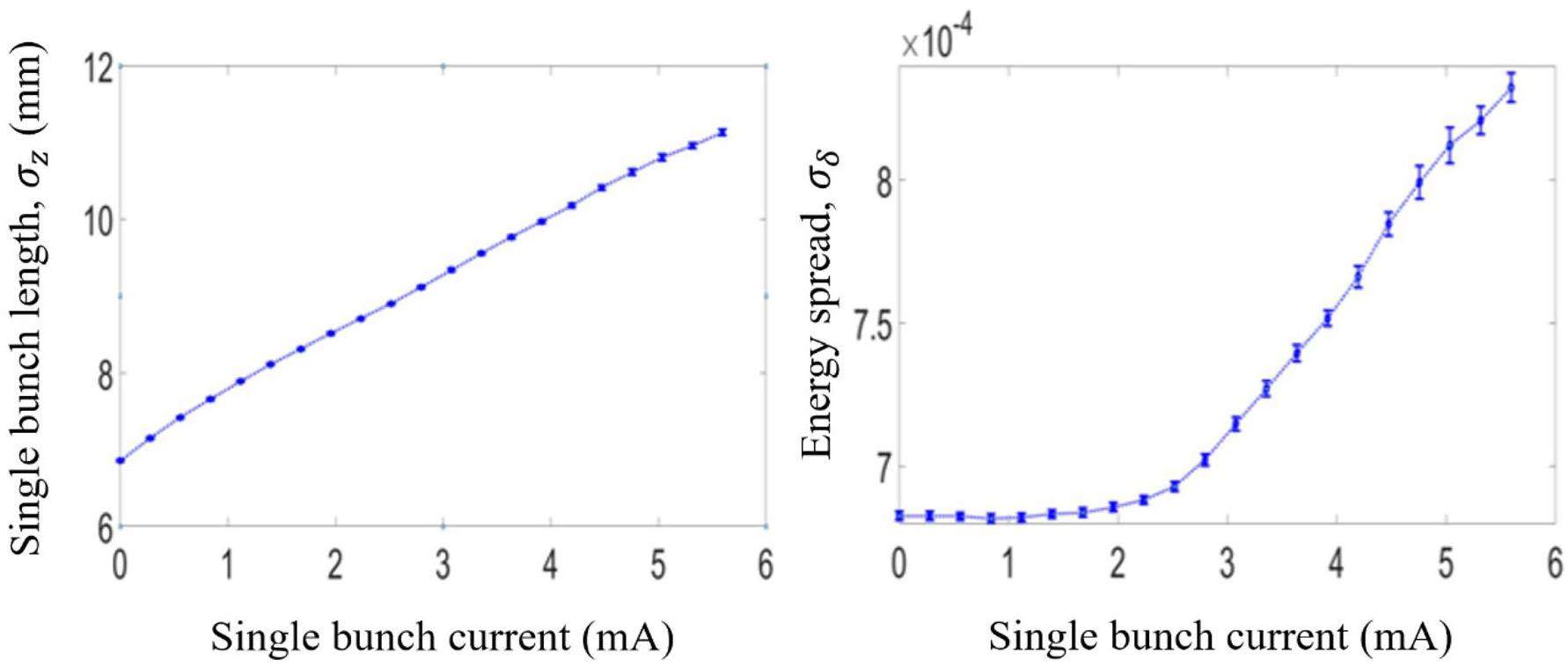

Beam collective effects encompass various phenomena correlated with beam current. On one hand, they can degrade beam quality, including by increasing emittance and energy spread; on the other hand, they can cause various instabilities that limit beam current and consequently reduce collision luminosity. Therefore, carefully studying the influence of these collective effects is essential. The types of beam collective effects are diverse and include intra-beam scattering (IBS) and Touschek scattering, which are both intra-scattering effects within the beam; various instabilities induced by the coupling of the beam with the impedance of the vacuum chamber environment, such as longitudinal microwave instabilities, transverse single-bunch instabilities, and coupled-bunch instabilities; and instabilities caused by residual gas molecules, ions, and electron clouds within the vacuum chamber. To meet the high-luminosity requirements of a collider, it is necessary to reduce the beta function

Impedance-driven single-bunch collective effects

Single-bunch collective effects [28] are predominantly governed by the broadband impedance of the storage ring (from flanges, BPMs, bellows, collimators, etc.) and include bunch lengthening, microwave instabilities, and transverse mode coupling instability (TMCI).

To suppress these effects, strict control of broadband impedance is required. During engineering implementation, this requires optimization of the vacuum chamber structure through streamlining geometry and minimizing discontinuities, combined with rigorous quality control in fabrication to mitigate impedance contributions—particularly from crucial vacuum components. Additionally, avoiding structures that could trap HOMs is crucial because they can lead to parasitic energy loss, local heating of vacuum chambers, and coupled-bunch instabilities.

When the single-bunch current remains below the microwave instability threshold, bunch lengthening is dominated by potential well distortion and can be described by

Microwave instability, a typical longitudinal single-bunch instability, arises when the current exceeds a certain threshold. While it does not cause particle loss, it degrades luminosity by amplifying the energy spread and elongating the bunch length. A conservative threshold estimate is provided by the Keil–Schnell–Boussard criterion

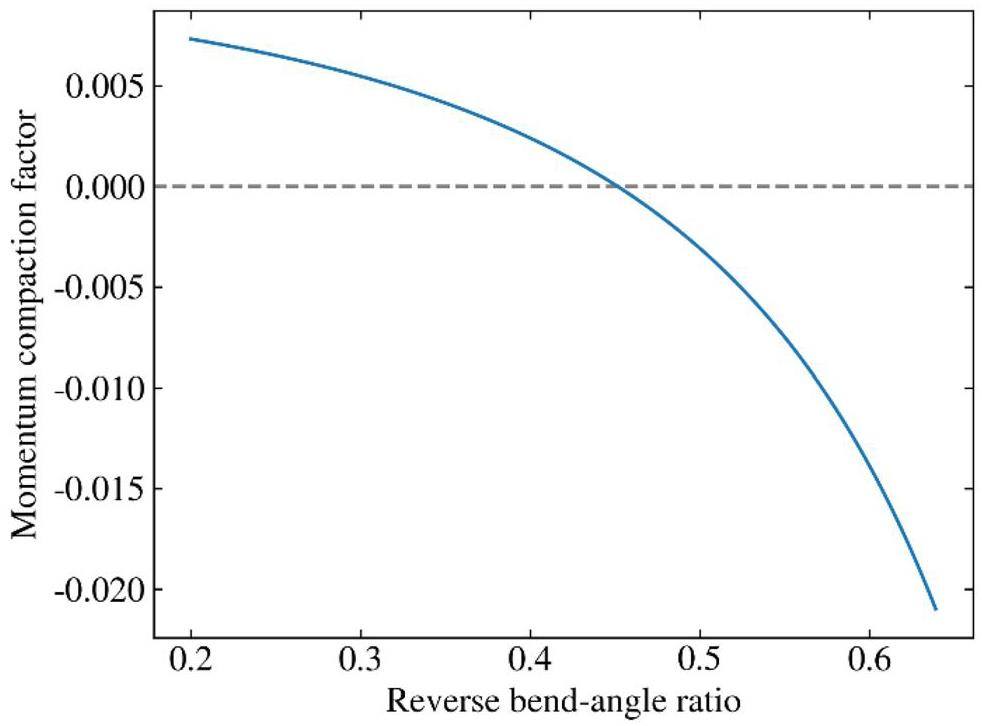

Simulations reveal that the microwave instability threshold is approximately 2 mA, which is smaller than the STCF’s target single-bunch current (2.8 mA). This proximity indicates potential operational risks. Increasing the momentum compaction factor

Coherent synchrotron radiation (CSR) and coherent wiggler radiation (CWR) [29] can also drive microwave instability. Assuming a wiggler vacuum chamber with a gap height of 35 mm, a peak field of 1.6 T, a single wiggler length of 4.8 m, and a period length of 0.6 m, the simulations employing CSR impedance models obtained using the CSRZ code and macro-particle tracking yield a single-bunch instability threshold of approximately 0.6 mA at a beam energy of 1 GeV; however, the instability is weaker at 2 GeV with a threshold of 3 mA. Strategies to enhance the current threshold at 1 GeV include modifying the wiggler period and optimizing the vacuum chamber geometry. The lattice could also be further optimized by increasing

Head–tail instability and TMCI are critical transverse single-bunch instabilities. Negative natural chromaticity can trigger the zero-mode head–tail instability, which is conventionally suppressed by using sextupoles to correct chromaticity to positive values. While positive chromaticity may excite higher-order head–tail modes, the mode tends to grow slowly and can be suppressed by radiation damping and transverse feedback systems. At zero chromaticity, increasing the beam current shifts the 0 mode toward the −1 mode, and after the threshold is crossed, the merging of the two modes triggers bunch instability, which is the strongest TMCI; hence, it is also called the strong head–tail instability. Once it occurs, the TMCI develops very fast and results in the rapid growth of transverse oscillations and particle loss. Thus, this instability must be strictly avoided.

Here, we only discuss the TMCI threshold under resistive wall impedance, assuming zero chromaticity, which is estimated using

To suppress the TMCI, the chromaticity can be corrected to positive values to help damp the head–tail zero-mode; however, this creates the risk of exciting higher-order head–tail modes. Nonetheless, these HOMs grow slowly and can be effectively suppressed by enhancing radiation damping through damping wigglers and implementing a transverse bunch-by-bunch feedback system, thereby raising the single-bunch transverse instability threshold current. In addition, the nonlinear collimation technique being developed at SuperKEKB—designed to mitigate impedance effects—may offer further benefits. Its potential application to STCF will be explored.

Impedance-related coupled-bunch instability

This analysis focuses on long-range wakefield effects, including narrowband impedance from RF cavities or vacuum structures and low-frequency resistive wall impedance. Instabilities induced by the RF cavity modes have already been discussed in Sect. 2.4 and will not be repeated here. Geometric narrowband impedances, which can trap resonant modes, should be minimized through the optimization of the geometric structures of the devices.

Resistive wall instability is mainly due to the strong transverse impedance near zero frequency. These long-range wakefields can cause transverse coupled-bunch instability. For Gaussian beams, the instability growth rate is governed by [30]

Here, the mode frequency is given by

Assuming a uniform aluminum beam pipe with a radius of 25 mm for the full ring circumference, Eq. (14) predicts an instability growth rate of 1.6 ms–1 at zero chromaticity. Although modern bunch-by-bunch feedback techniques can achieve damping times of approximately 100 μs or better, the SuperKEKB experience [31] shows that the noise of the feedback system has an important impact on the luminosity stability. A slower feedback system combined with other measures, such as correcting chromaticity to positive values to reduce the growth rate, is being considered. With these measures, STCF is expected to manage this instability effectively.

Beam lifetime

The Touschek scattering effect is the dominant factor limiting the beam lifetime in the collider rings. It refers to large-angle Coulomb scattering between two electrons or positrons within a bunch, where, during collisions, one particle transfers its transverse momentum to the longitudinal momentum of another particle. This interaction makes it possible for some particles to exceed the energy acceptance and be lost. From the local momentum aperture (LMA) shown in Fig. 24, the calculated beam lifetime at 2 GeV is approximately 252 s.

Residual gas scattering includes elastic scattering and inelastic scattering. Elastic scattering leads to transverse oscillations, and the particle will be lost if its amplitude exceeds the dynamic aperture. Inelastic scattering causes the deceleration and energy deviation of the particle, and it will also lead to a loss if it is beyond the momentum acceptance. Based on the SuperKEKB experience, elastic scattering is the dominant factor for vacuum-related beam losses in this collider ring type.

Assuming all residual gas molecules are CO, the vacuum-limited lifetime is

Ion effects and electron cloud effects

Ion instabilities originate from the interaction between the electron beam and their trapped ions. The ions are generated from the ionization of residual gas in the vacuum and desorption from the vacuum wall. In modern electron storage rings, ultra-high vacuum systems can provide a pressure lower than 10–7 Pa and can generally minimize these effects. When designing the bunch filling scheme, large gaps are typically introduced between bunch trains to help suppress ion instabilities. In addition, transverse bunch-by-bunch feedback systems can effectively suppress fast ion–induced oscillations. Transient fast ion instabilities may still occur during early machine operation under poor vacuum conditions but will diminish as the vacuum improves.

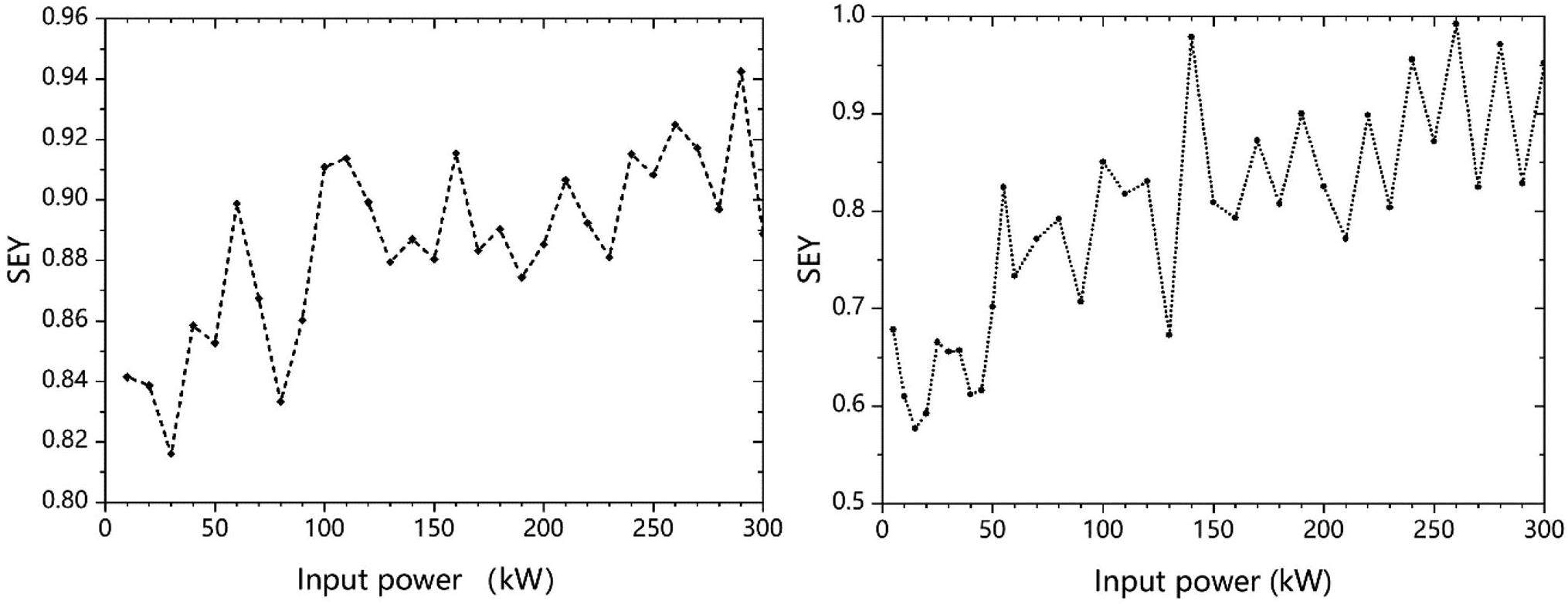

In the positron ring, synchrotron radiation photons strike the vacuum chamber wall and release photoelectrons. These photoelectrons are accelerated by the positron beam and can be multiplied by multiple reflections between the walls. The electrons captured by the positron beam form the so-called electron cloud [32]. The electron cloud interacts with the positron bunches and can couple the motions of successive positron bunches and cause both coupled-bunch instability and single-bunch head–tail instability. Using the PEI and PyECLOUD codes for simulations, at 2 GeV and with an average chamber diameter of 50 mm and a secondary electron yield (SEY) of 1.3, the cloud density near the beam is

Beam injection and extraction

The primary objective of the beam injection design for the collider rings is to inject positron/electron beams from the upstream injector into the collider rings with maximum efficiency. This ensures high integrated luminosity, minimizes disturbances to the circulating beam during injection, and reduces injection-related beam loss and its impact on detector background. The primary goal of the beam extraction design is to extract the high-energy, high-charge positron/electron bunch trains from the ring efficiently and transport them to the beam dump.

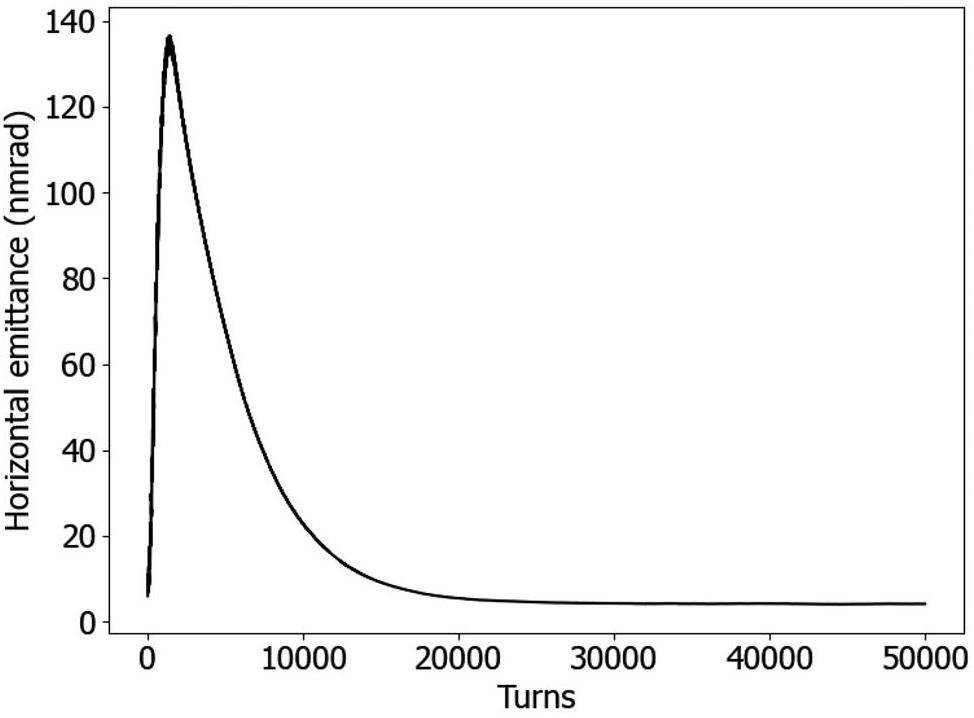

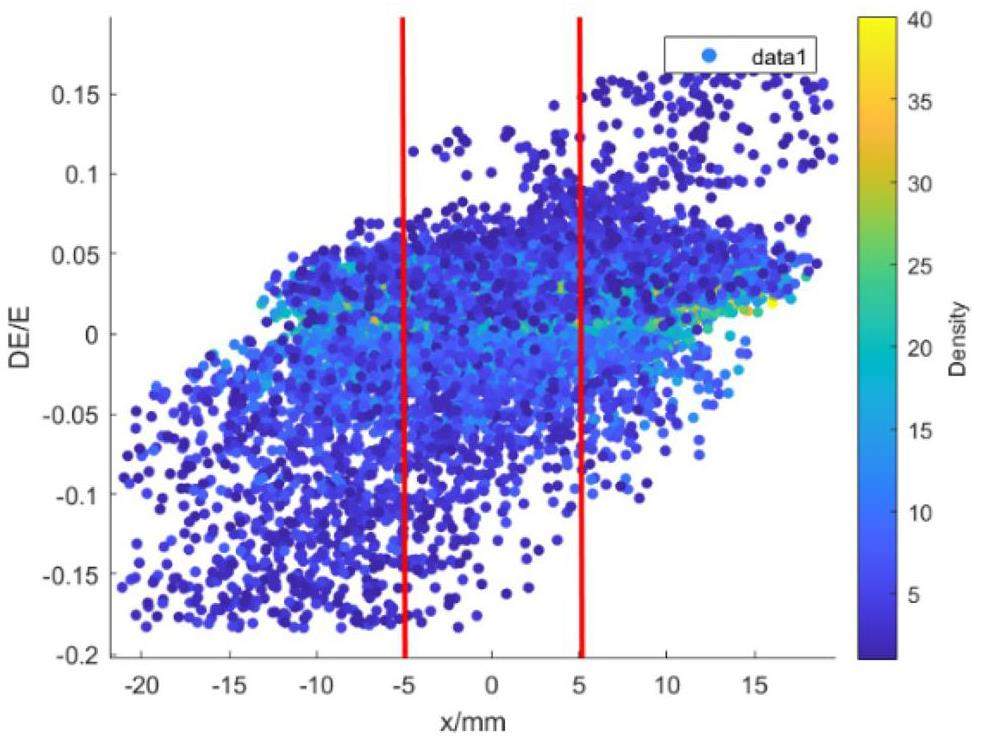

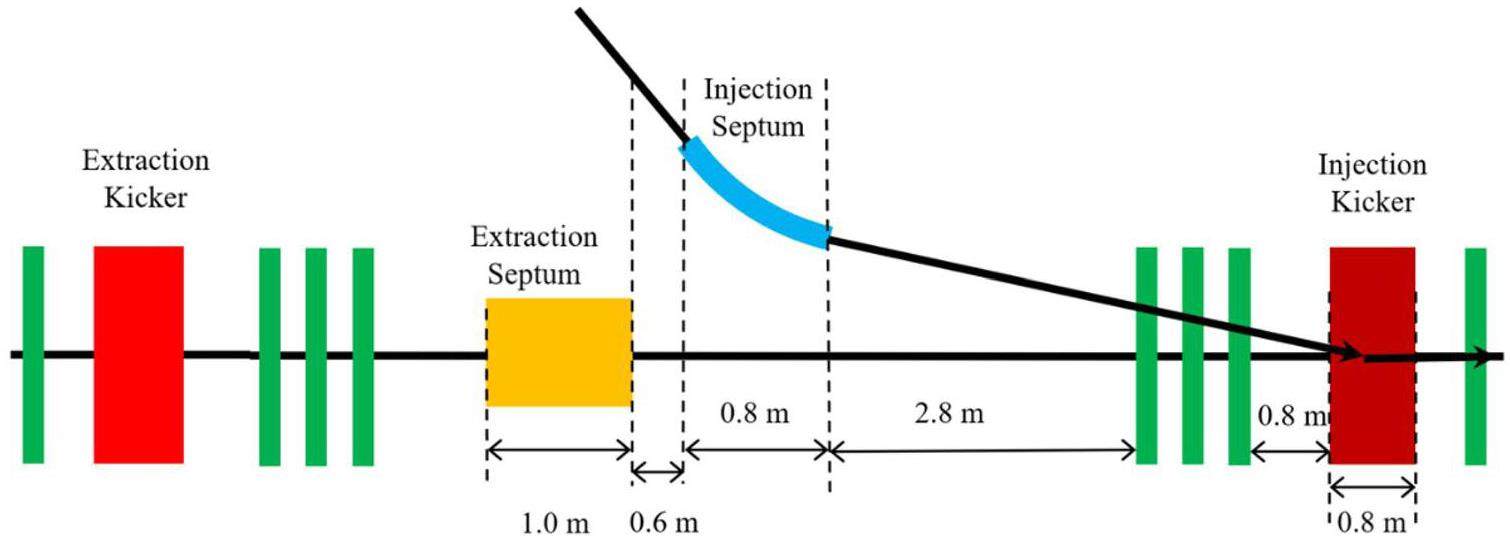

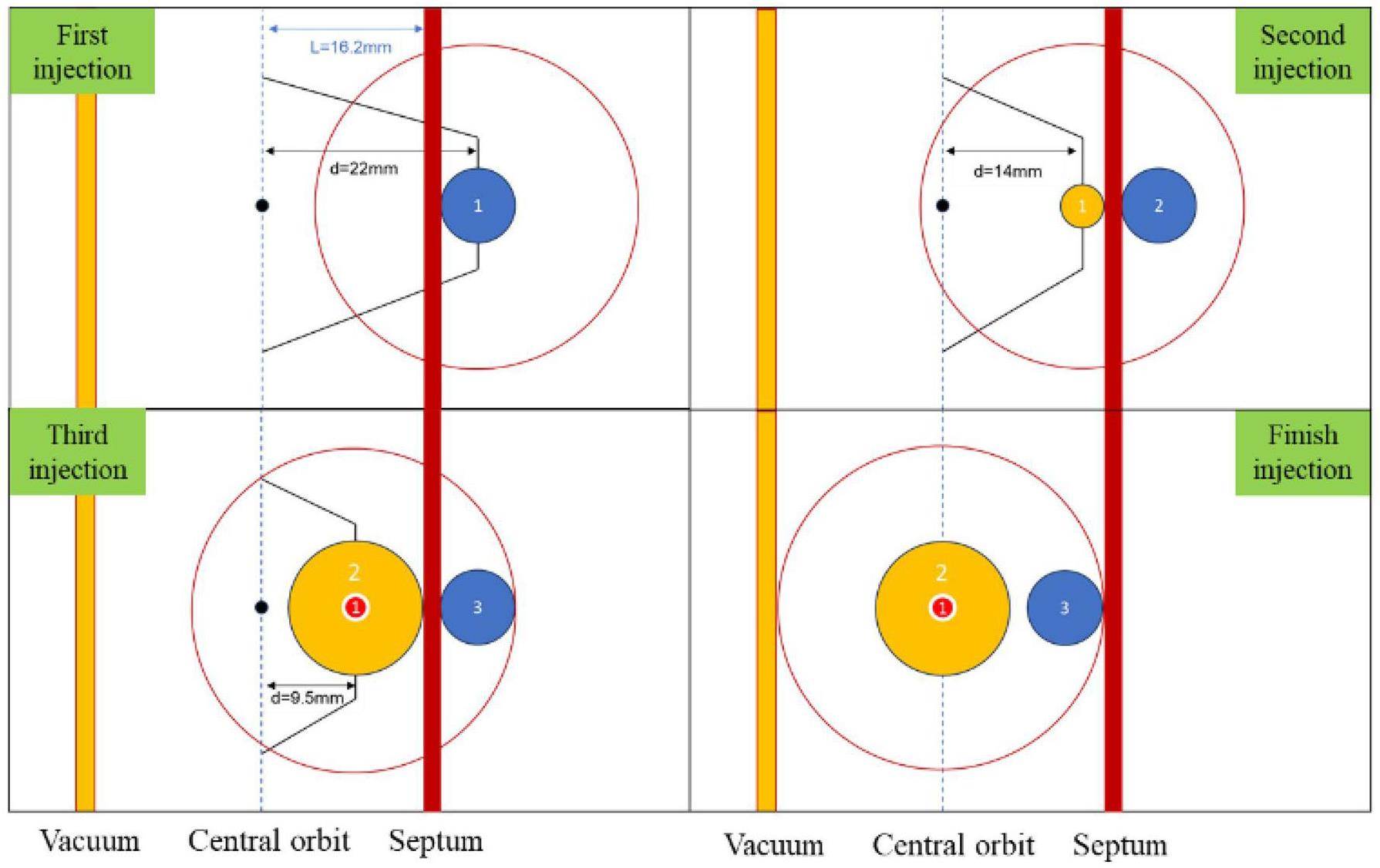

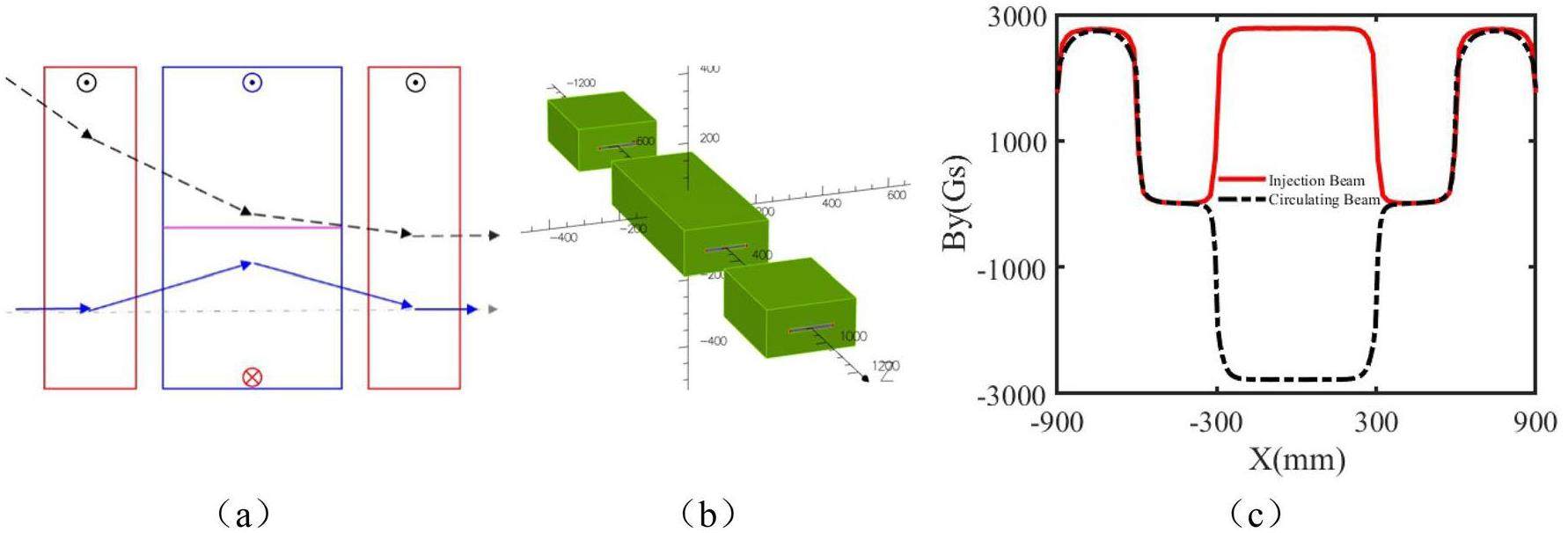

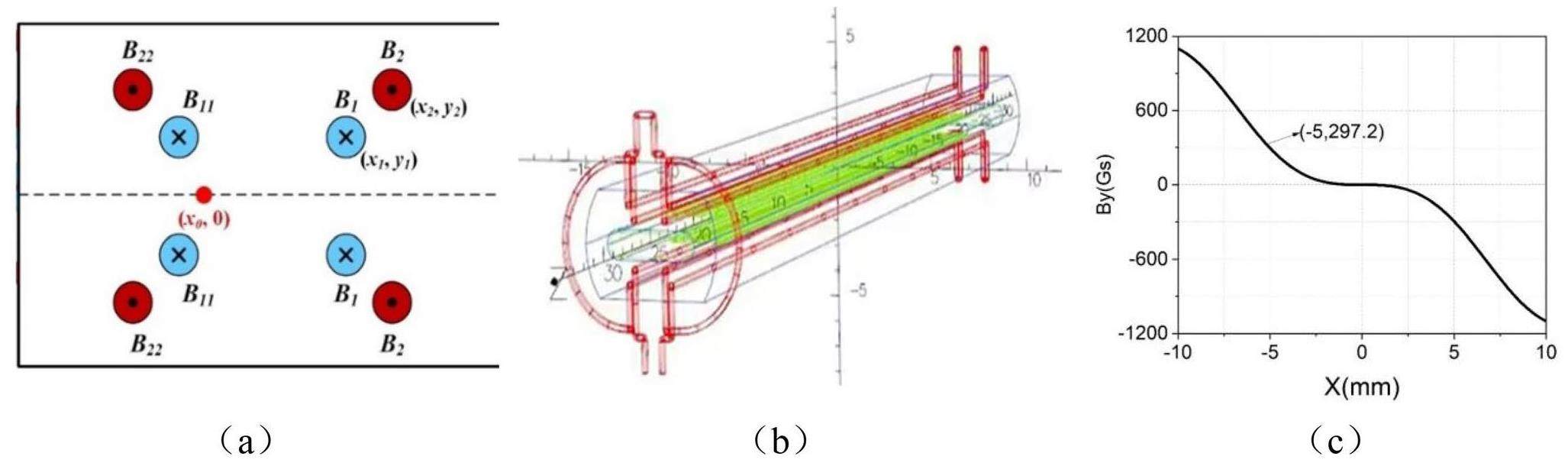

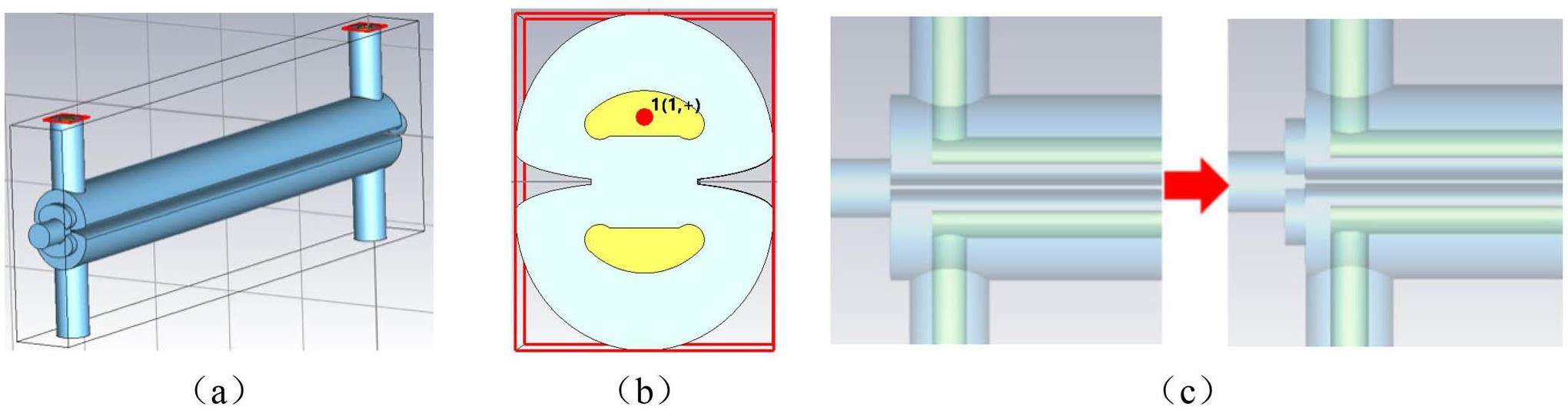

Several injection methods are used or studied for electron storage rings, including conventional off-axis injection (with variations), longitudinal injection, and swap-out injection. Since the momentum aperture of the STCF collider lattice design is small and STCF is not suitable for using an RF frequency lower than 500 MHz, increasing the bucket length, longitudinal injection, and off-momentum injection are not good options. Currently, considering the design of the upstream injector and the overall cost of the accelerator, STCF will adopt a compatible injection scheme combining off-axis injection and bunch swap-out injection. The off-axis injection scheme [33] is chosen as the baseline and will be employed in the construction. Different off-axis injection methods, such as employing bump kickers, nonlinear kickers, and anti-septum, are under investigation. Only the injection method employing bump kickers is described here. Thus, the injection system consists of a septum magnet and bump magnets. The injected and circulating beams are transversely separated. Under the action of the bump magnets, the closed orbit of the circulating beam moves closer to the septum magnet, and after one or several turns—once the injected beam falls within the collider ring acceptance—it returns to the pipe center. Eventually, the injected beam merges with the circulating beam via synchrotron radiation damping. This scheme is mature and imposes relatively low requirements on the rise time of the injection elements but requires a large dynamic aperture.

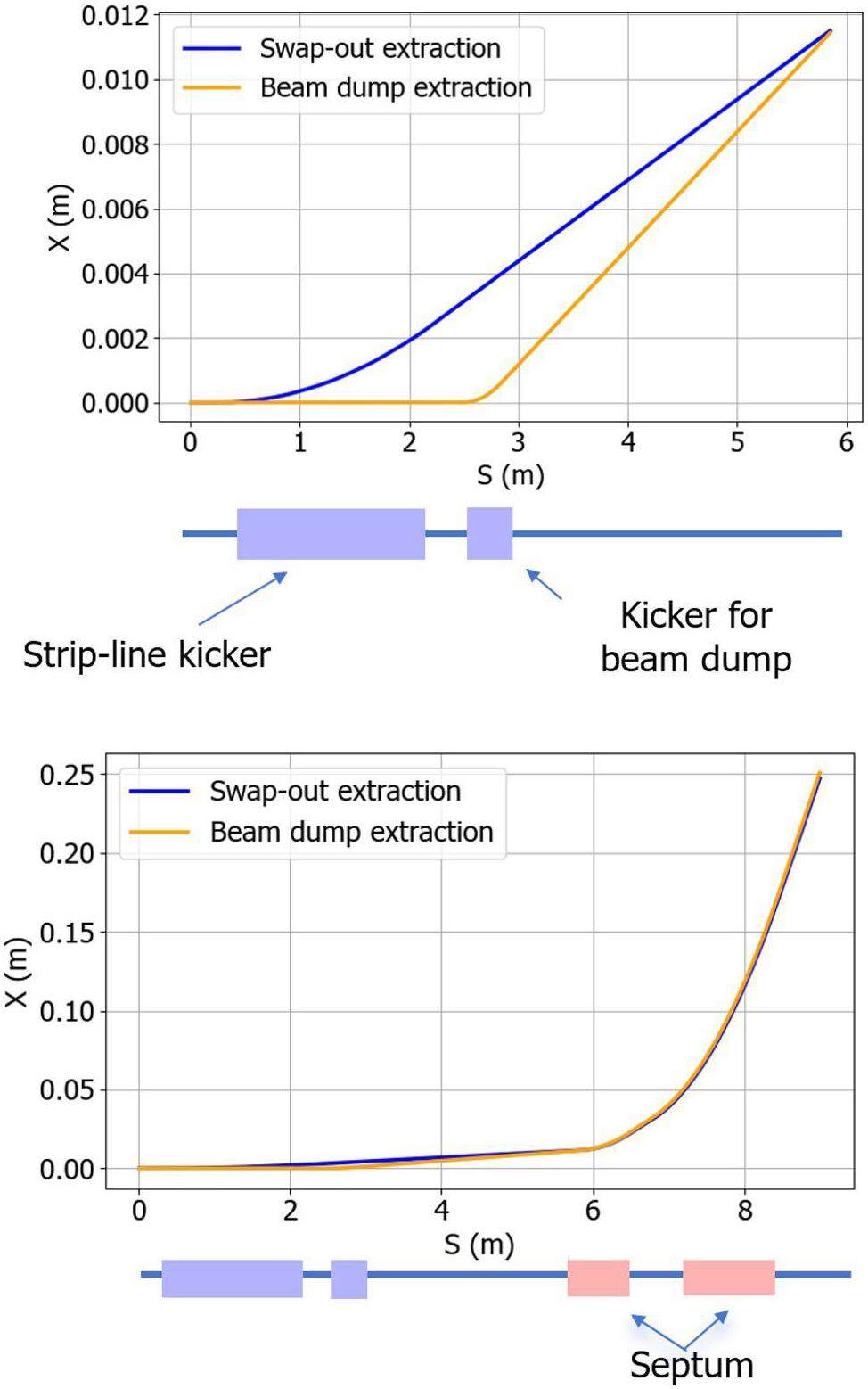

In the future, based on need, the system can be upgraded to a bunch swap-out injection scheme [34], while using the same injection section. With this scheme, circulating bunches are one-to-one replaced with newly injected bunches using ultra-fast pulsed kicker magnets. This scheme requires less dynamic aperture in the horizontal plane but imposes strict constraints on the kicker pulse width—it must be less than twice the minimum bunch spacing. Additionally, injecting high-charge positron bunches places stringent requirements on the repetition rate of the upstream injector. To facilitate future upgrades, the quadrupole magnets in the injection section will be laid out in a uniform design, requiring only the replacement of kicker components for the transition. Hardware parameters will be selected accordingly, and the injection process will be validated through tracking simulations.

The extraction system design for the collider rings also includes two operational scenarios. During bunch swap-outs, small angular deviations induced by ultra-fast pulsed kicker magnets are used, and the downstream septum magnet deflects the target bunch out of the ring. This method places stringent performance requirements on the ultra-fast kickers, similar to those in injection, requiring a pulse with a full width shorter than 6 ns. For beam dumping, the different kickers must have a rise time shorter than the gap between bunch trains and a flat-top width longer than the revolution period, enabling the extraction of whole bunches in one turn.

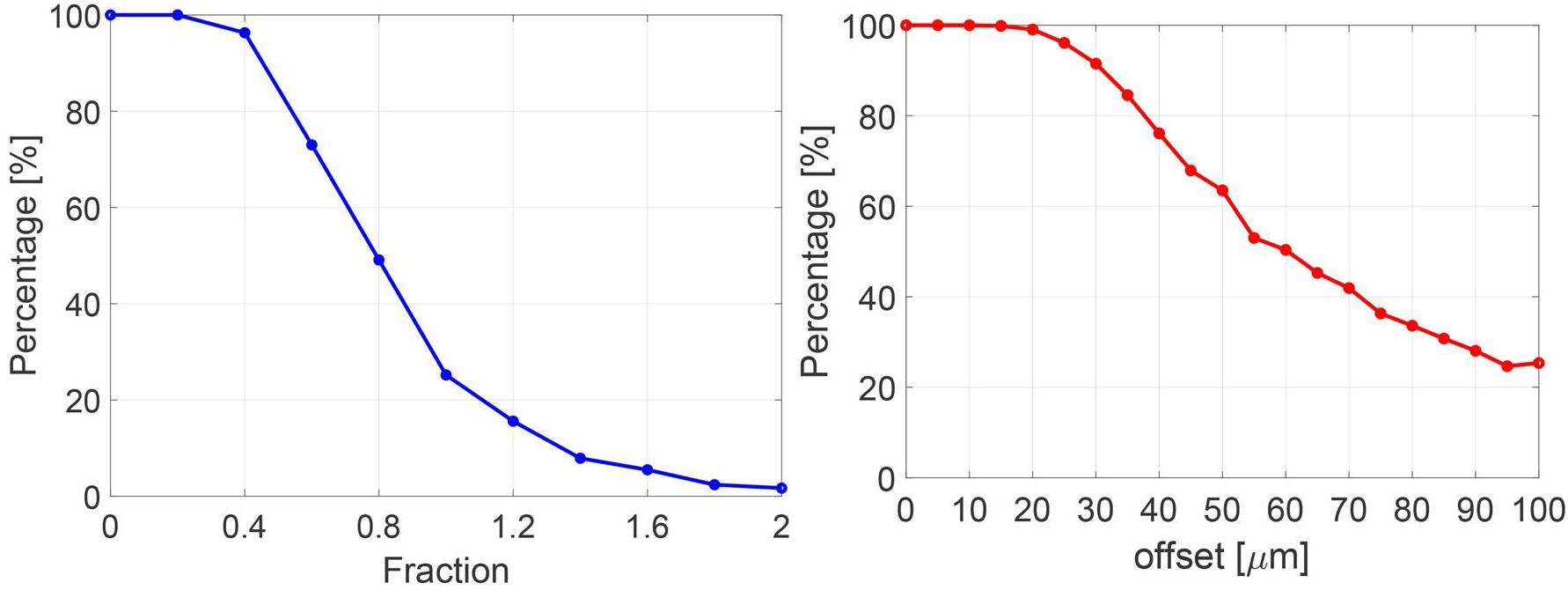

The luminosity fluctuation requirement forms the basis of the beam injection design. For example, assuming a 7% degradation in single-bunch luminosity and a typical beam lifetime of 250 s, the physical requirements for beam injection in the off-axis and swap-out injection schemes are summarized in Table 6. The goal of the injection design is to meet the parameters provided in Table 6, particularly the injection efficiency.

| Injection Scheme | Off-axis injection | Swap-out injection |

|---|---|---|

| Collider ring circumference (m) | 860.321 | 860.321 |

| Bunch spacing (ns) | 4 | 4 |

| Min. single-bunch luminosity/Peak | 93% | 93% |

| Beam lifetime (s) | ≈250 | ≈250 |

| Time to complete full ring injection (s) | 18.14 | 18.14 |

| Circulating bunch charge (nC) | 8.34 | 8.34 |

| Circulating beam emittance (rms) (nm·rad) | 4.16 (0.5% coupling) | 4.16 (0.5% coupling) |

| Injected bunch charge (nC) | 1.0* | 8.5 |

| Charge to refill/replace (nC) | 0.6 | 8.34 |

| Injected beam emittance (rms) (nm·rad) | H < 6; V < 2 | H < 30; V < 10 |

| Injection efficiency | > 60% | > 98% |

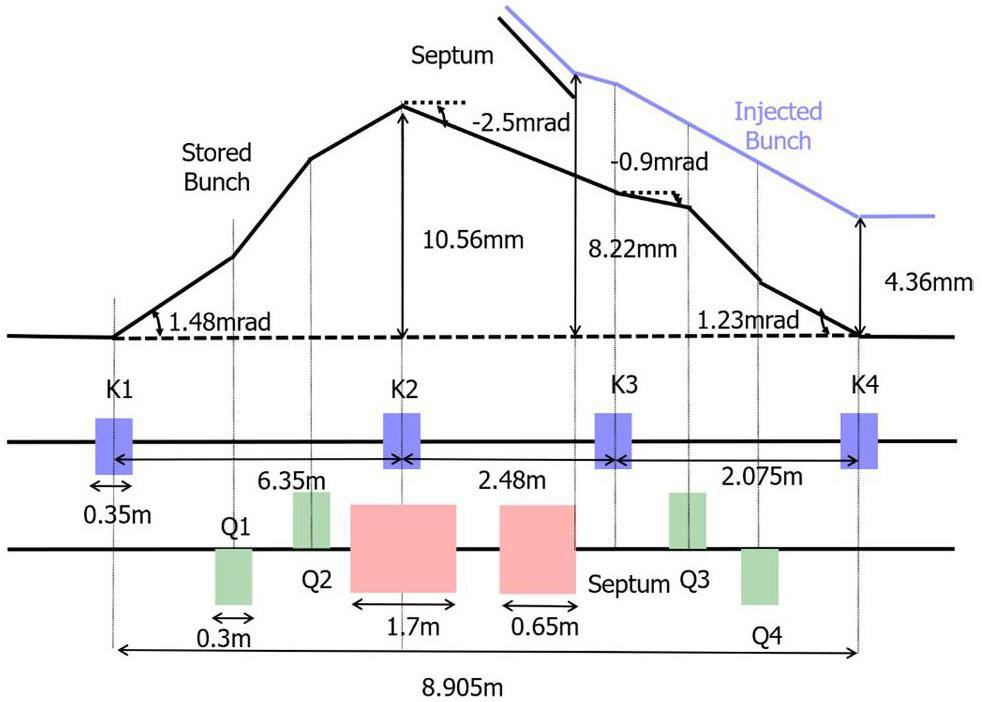

Off-axis injection

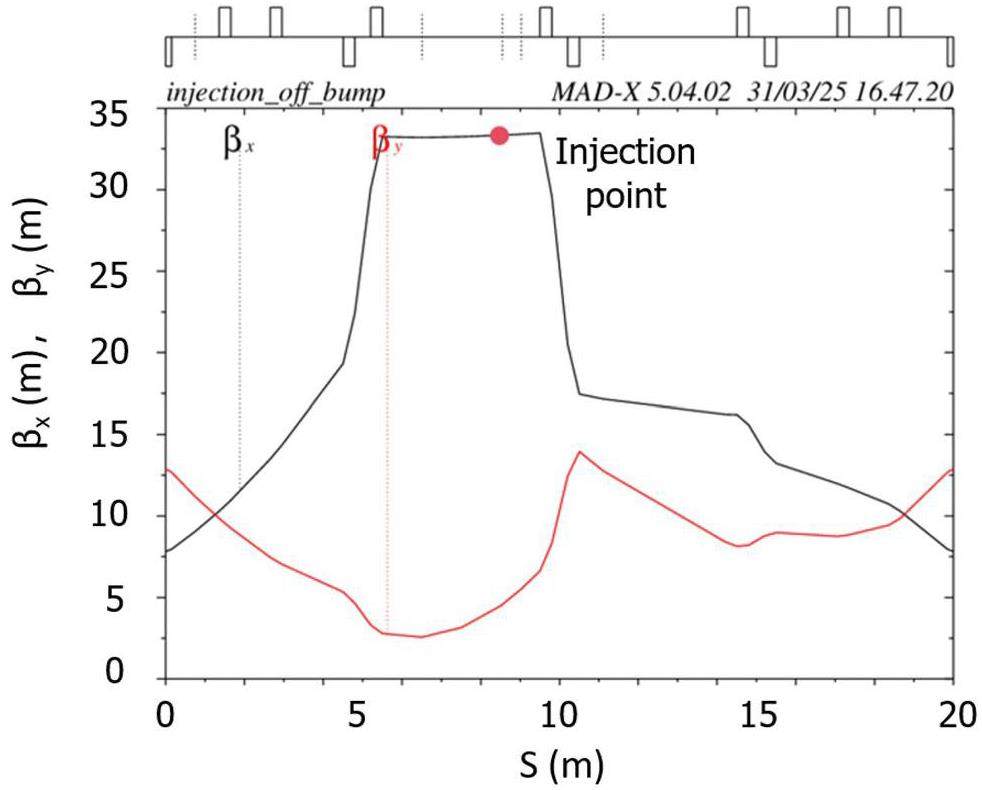

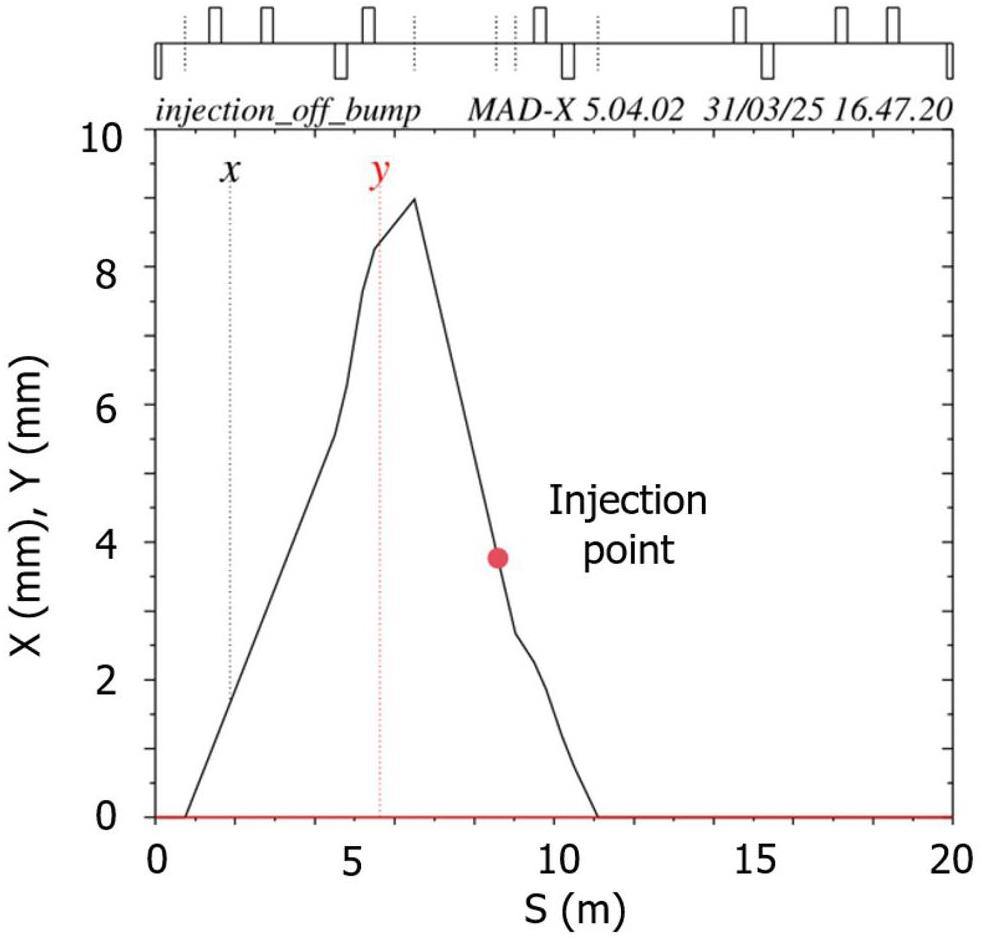

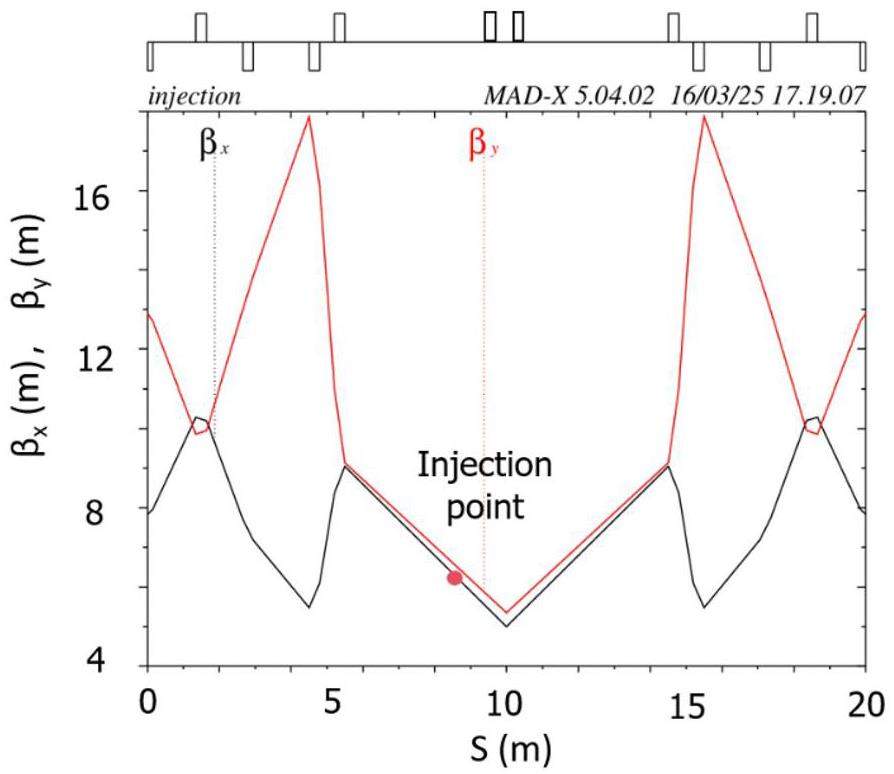

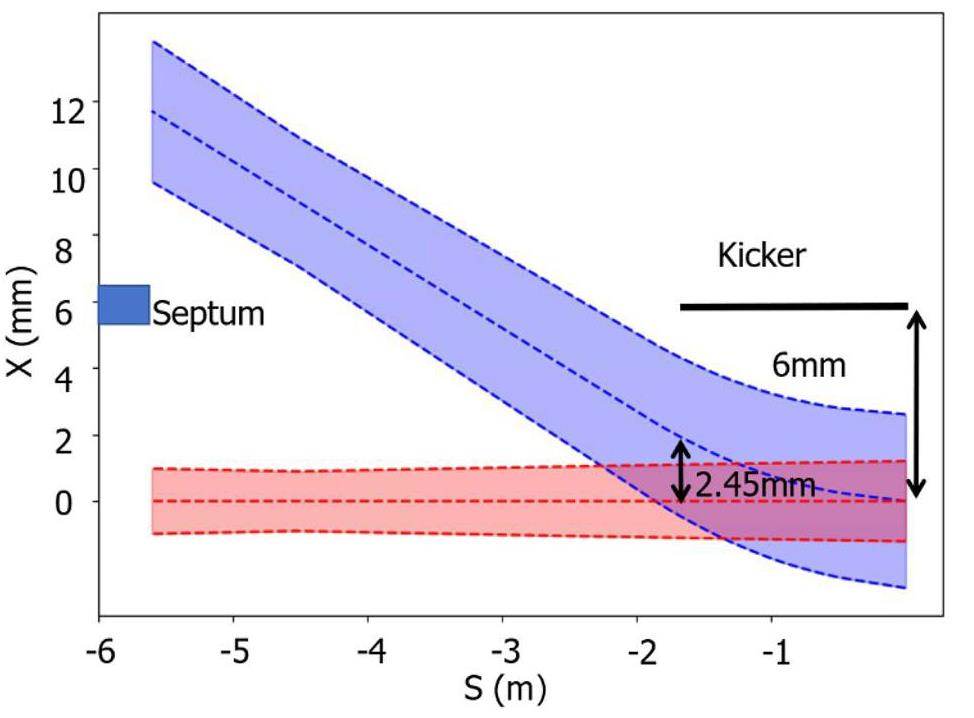

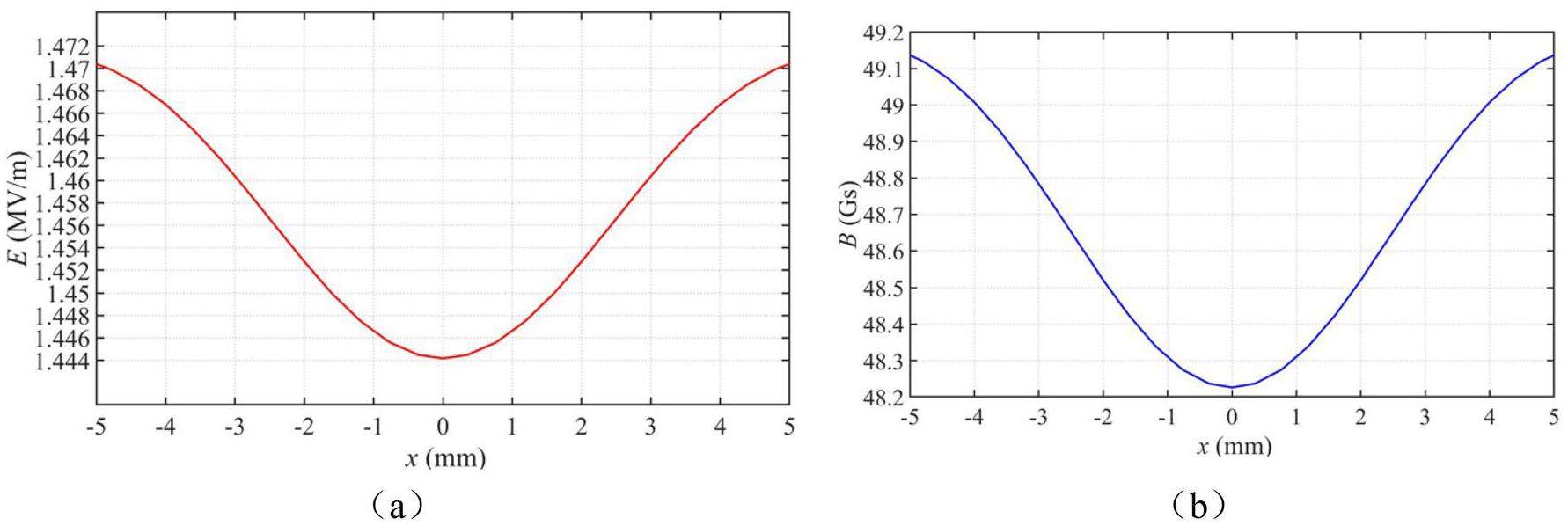

The key to off-axis injection design is to use local orbit bumps to steer the injected beam into the ring acceptance while minimizing its transverse offset from the central orbit and reducing beam losses at the septum magnet [35]. First, the optics of the injection section must be configured with large β functions to reduce the impact of septum thickness and closed-orbit errors on injection efficiency. Second, the beam clearance aperture must be optimized to balance dynamic aperture and beam losses—a clearance that is too large requires an excessively large dynamic aperture, while one that is too small causes significant beam loss. Lastly, the local bump orbit must be designed with appropriate bump height and angle so that the injected beam exits the septum magnet as close as possible to the pipe center, without excessive loss of the injected beam, while also controlling the influence of the stray magnetic field of the septum magnet to the circulating beam.

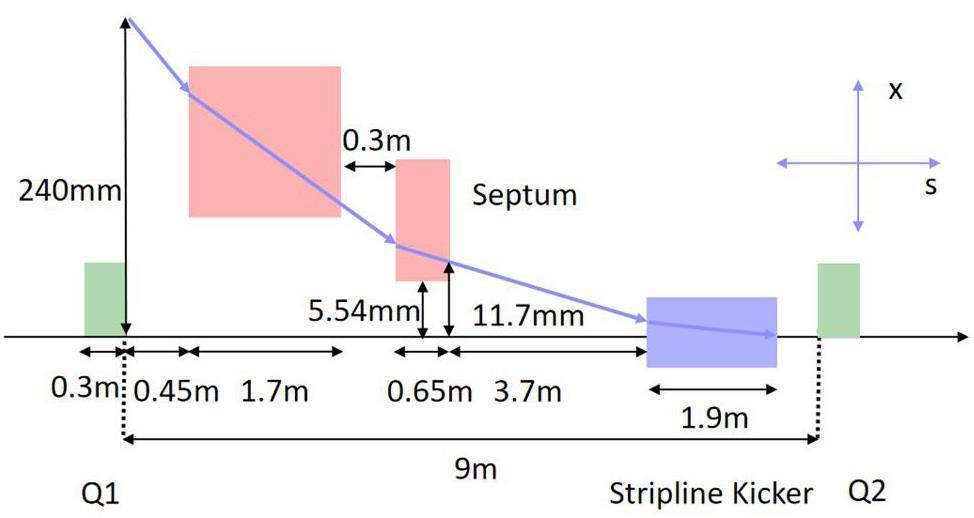

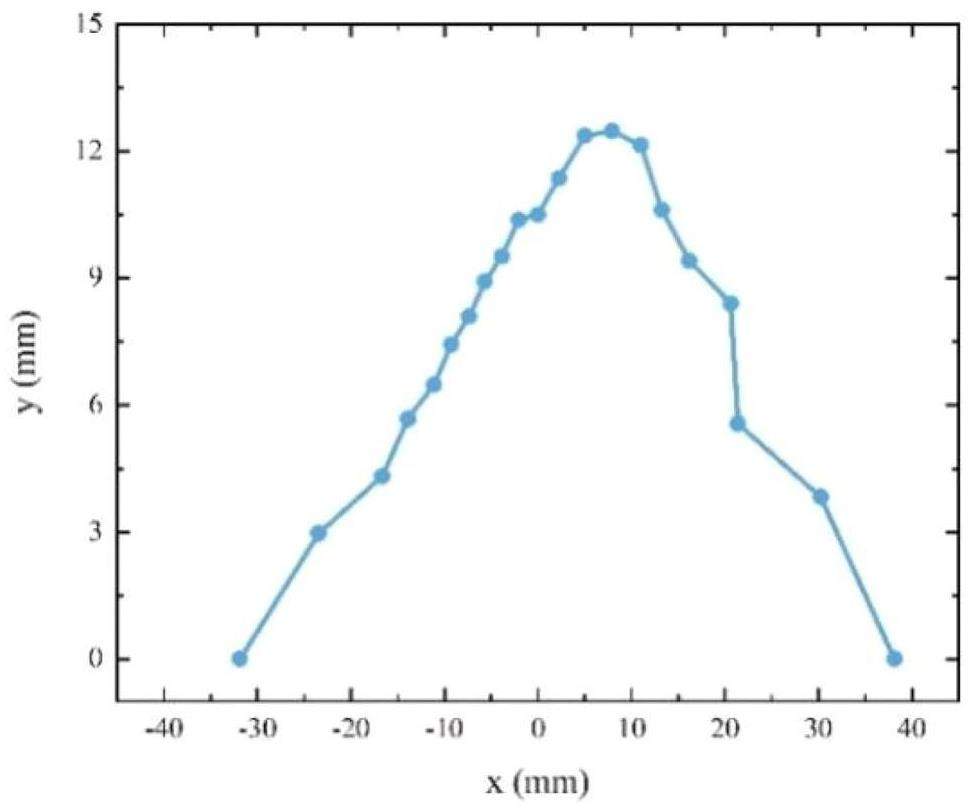

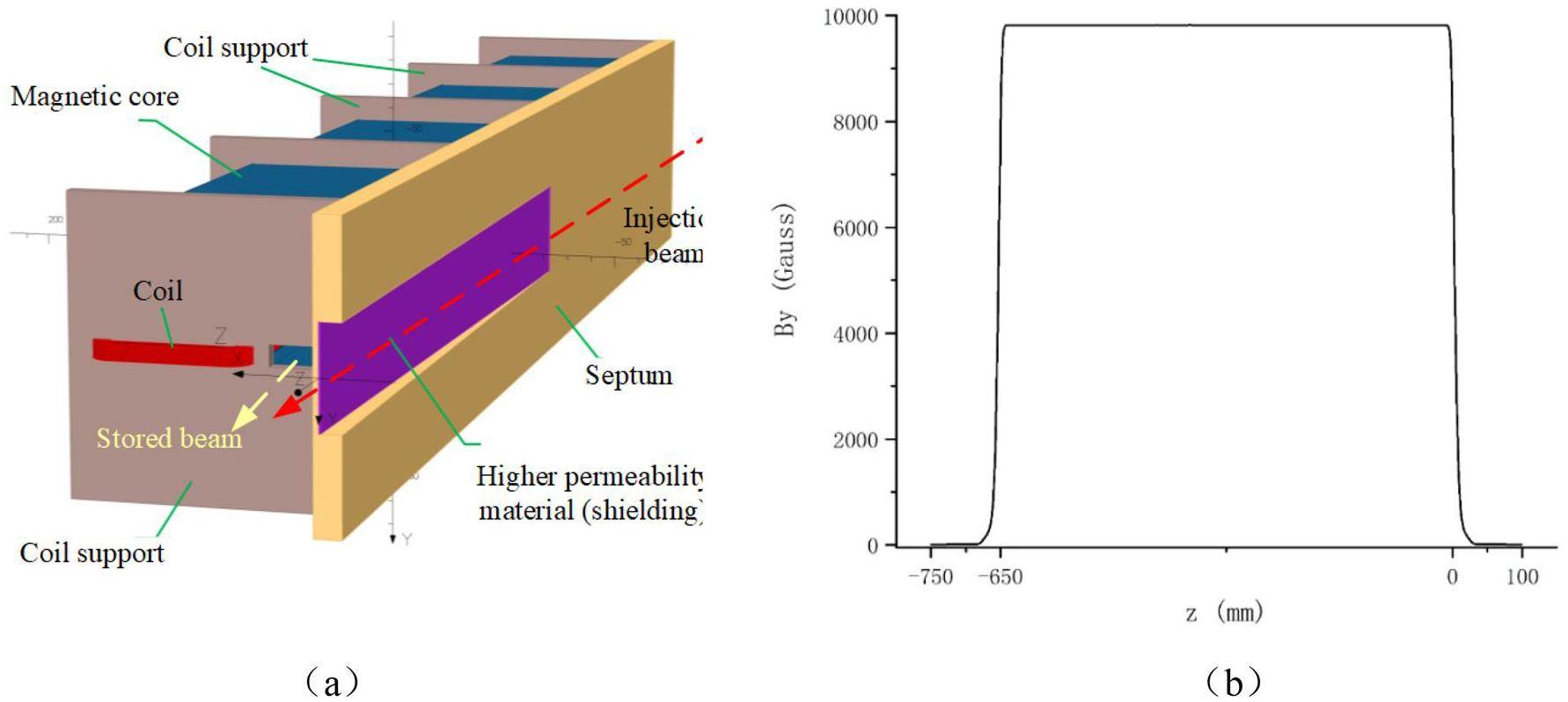

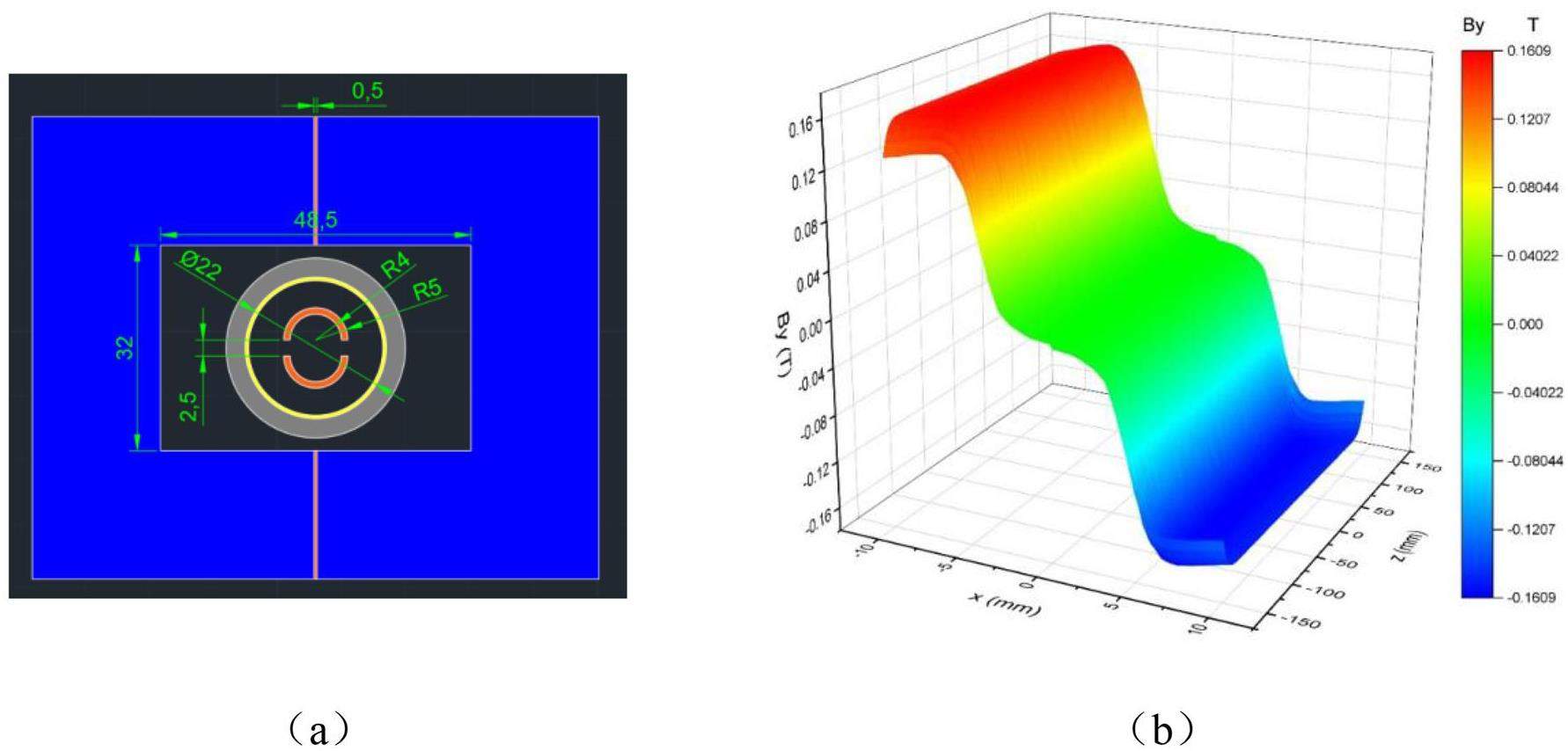

The off-axis injection system in the STCF collider rings consists of three components: quadrupoles for optics matching, bump magnets to form the local orbit, and septum magnets for large-angle bending of the injected beam. Table 7 lists the key parameters. Figure 38 shows a schematic of the off-axis injection scheme, while Fig. 39 presents the layout and optics of the injection section, located in one of the 20 m-long straight sections of the collider rings, where 10 quadrupoles are installed for optics matching. Figure 40 illustrates the local bump orbit formed by four bump magnets. Each magnet provides a maximum bending angle of less than 3.5 mrad and can be adjusted independently to vary the orbit height and angle.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Circulating beam clearance (mm) | 1.68 (4.5σ) |

| Injected beam clearance (mm) | 1.18 (4.5σ) |

| βx at injection point (inner/outer ring) (m) | 33.34 / 11.53 |

| Injection angle (mrad) | –2.45 |

| Orbit bump height at injection point (mm) | 3.86 |

| Orbit bump angle at injection point (mrad) | –2.50 |

| Position after bump recedes (mm) | 4.36 |

| Bump duration (turns) | 1 |

| Bump magnet length (mm) | 350 |

| Max bump magnet deflection angle (mrad) | < 3.5 |

| Bump magnet field strength (Gs) | < 1167 |

| Thin septum height (mm) | 5.54 |

| Thin septum thickness (mm) | 1.0 |

| Thin septum length (mechanical/effective) (m) | 0.65 / 0.6 |

| Thin septum field strength (Gs) | 5500 |

| Thin septum deflection angle (mrad) | 28 |

| Thick septum thickness (mm) | 2.0 |

| Thick septum length (mechanical/effective) (m) | 1.7 / 1.3 |

| Thick septum field strength (Gs) | 9900 |

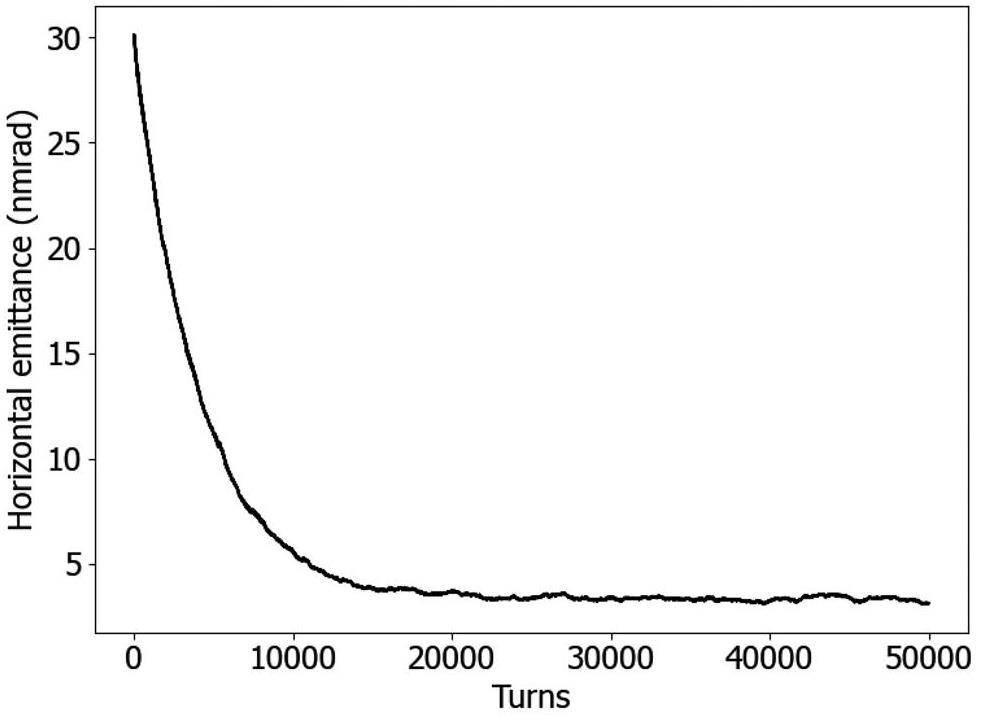

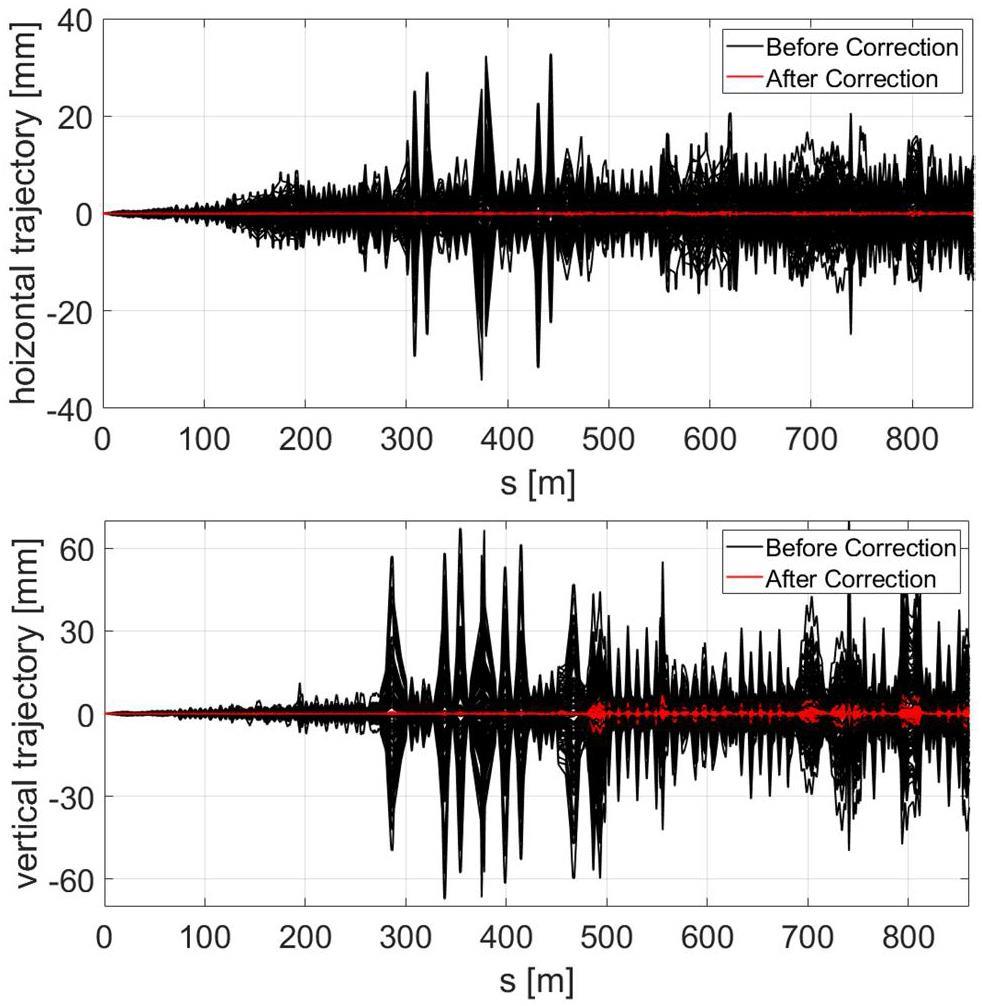

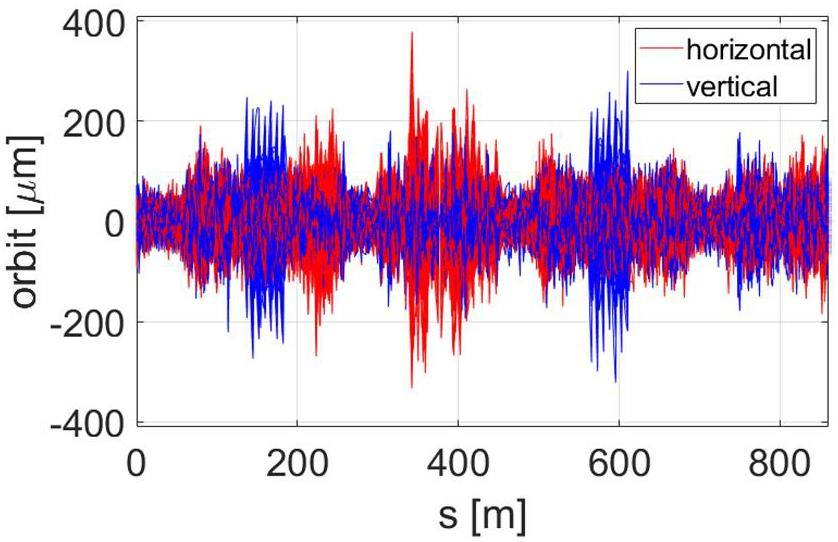

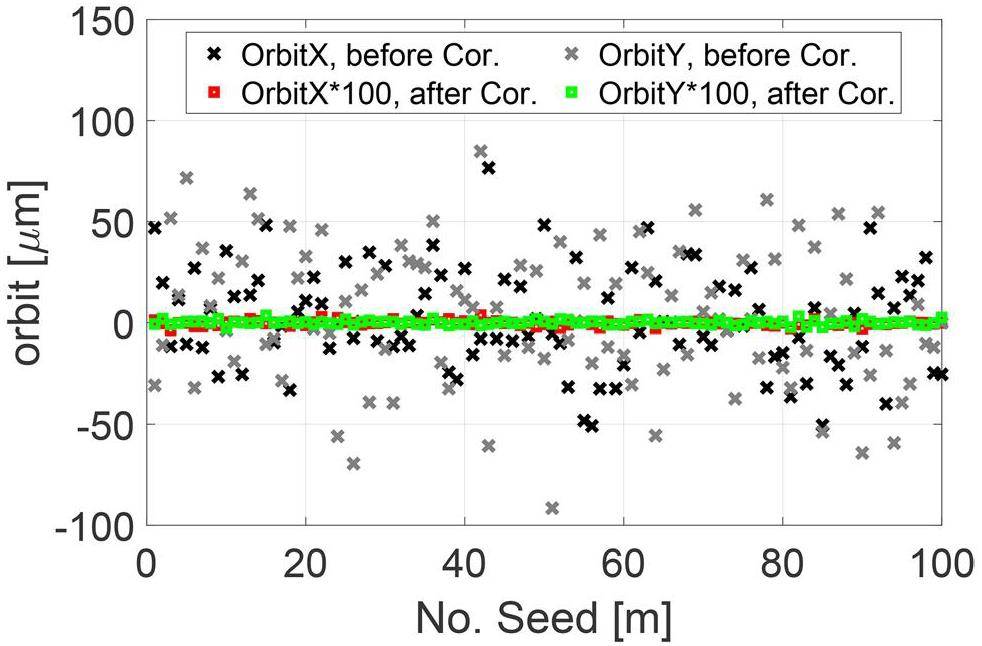

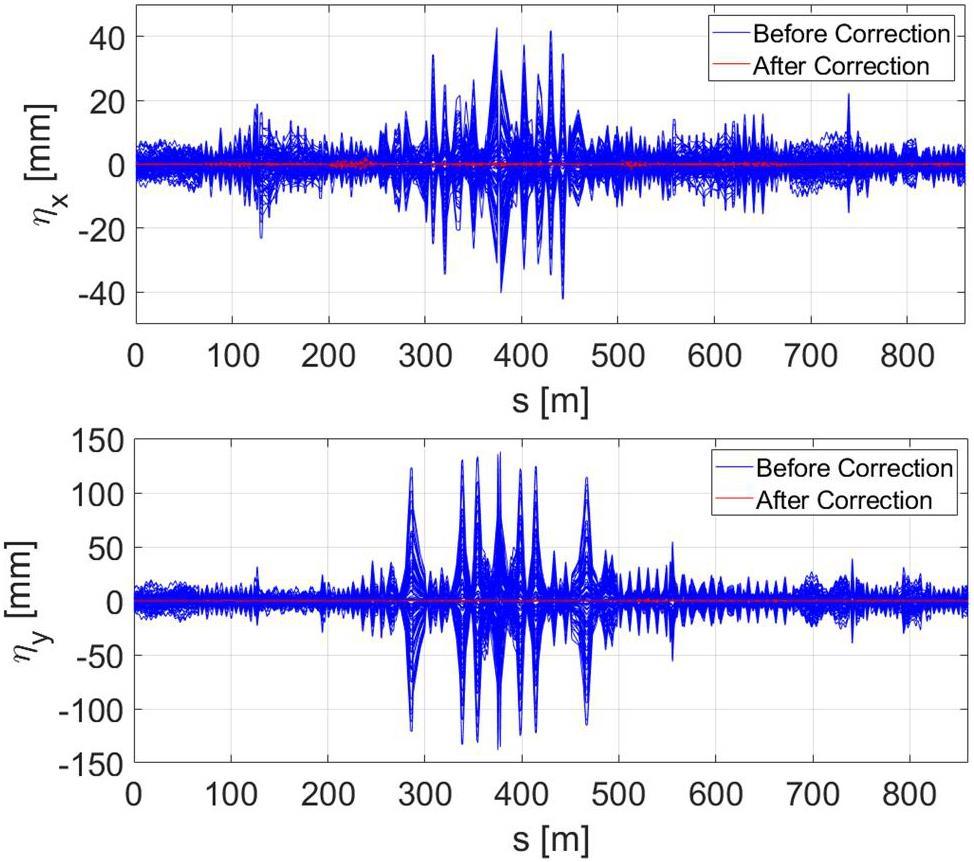

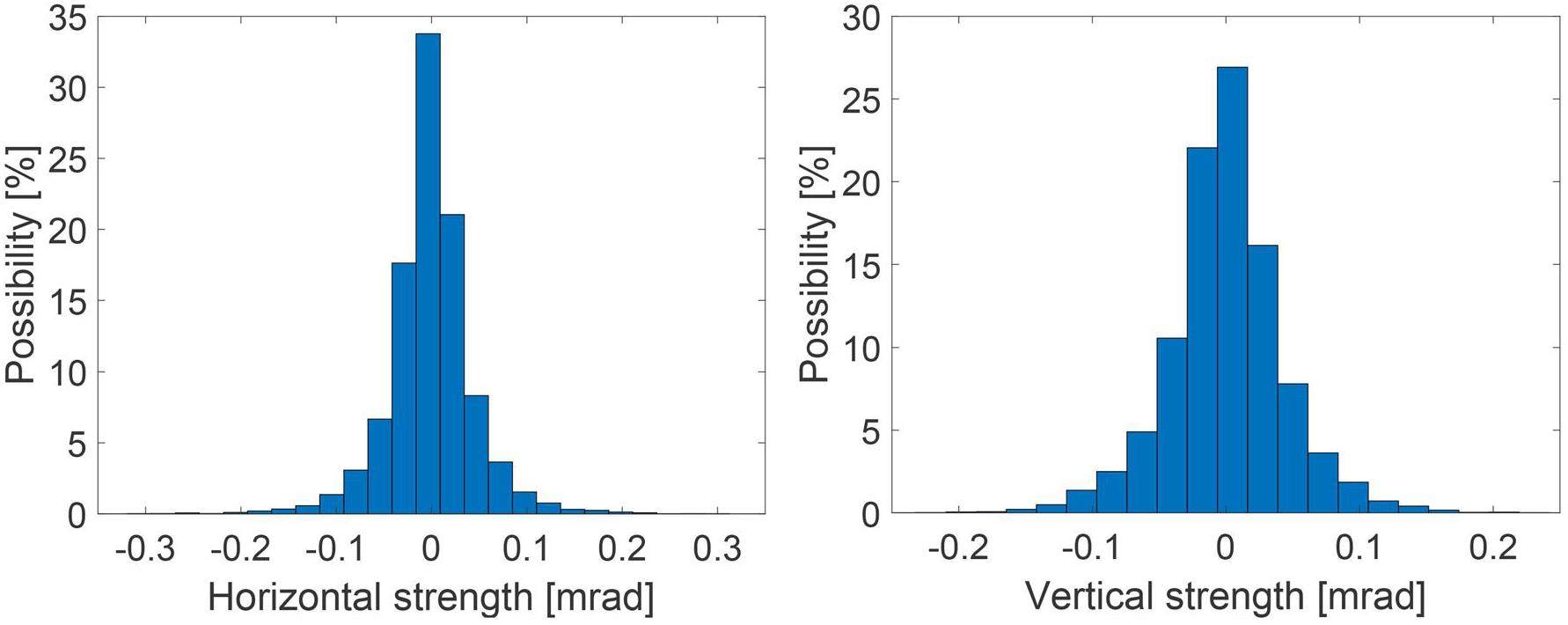

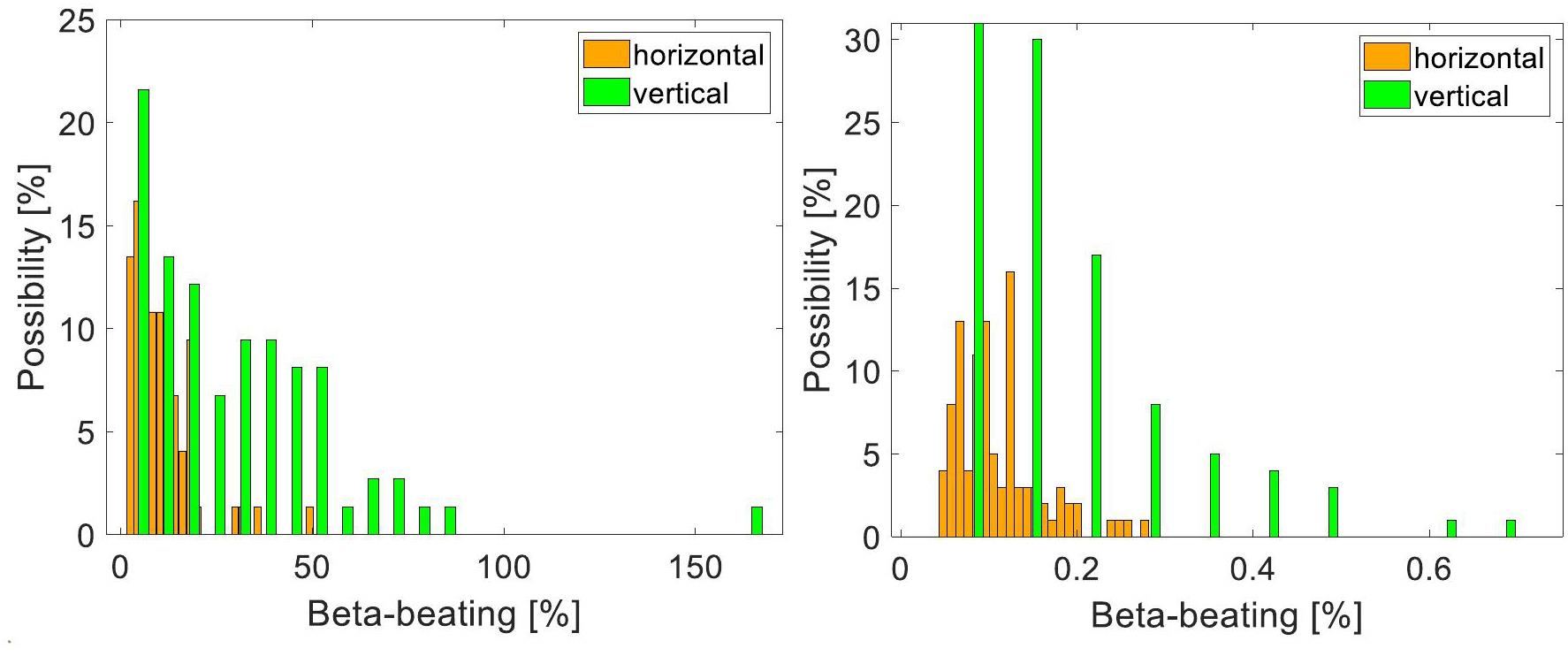

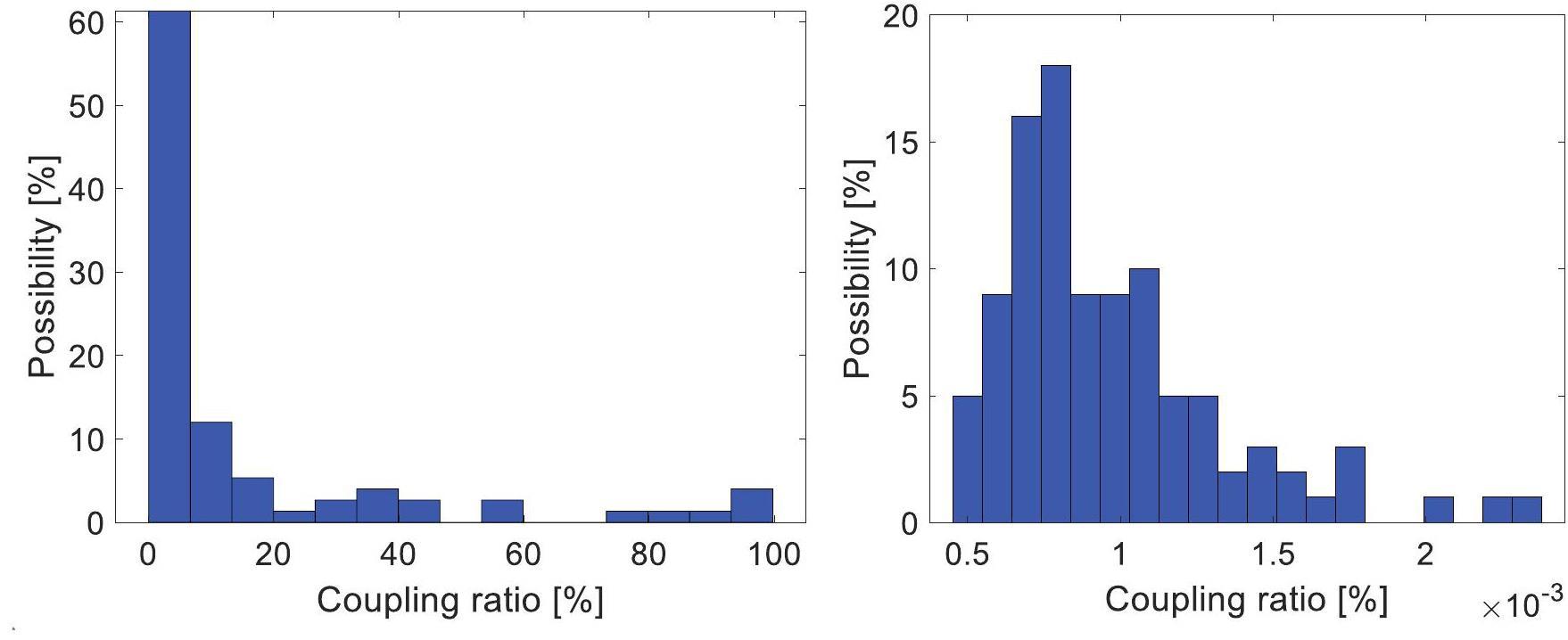

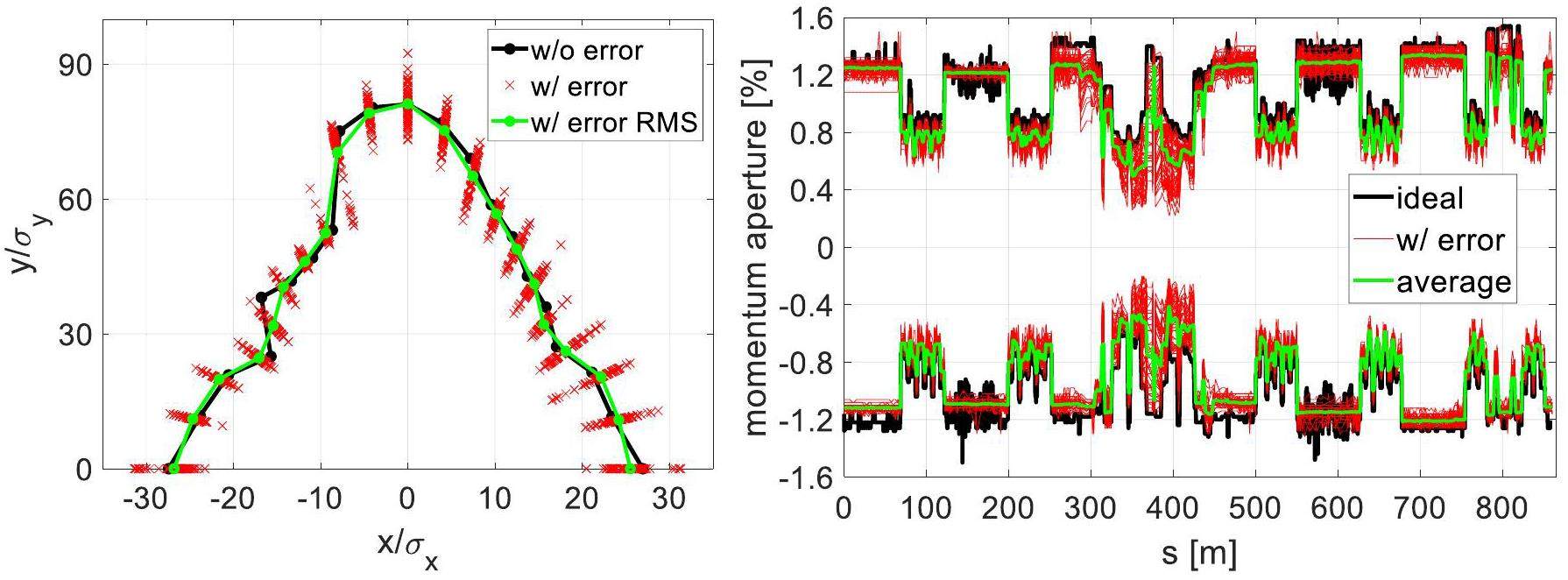

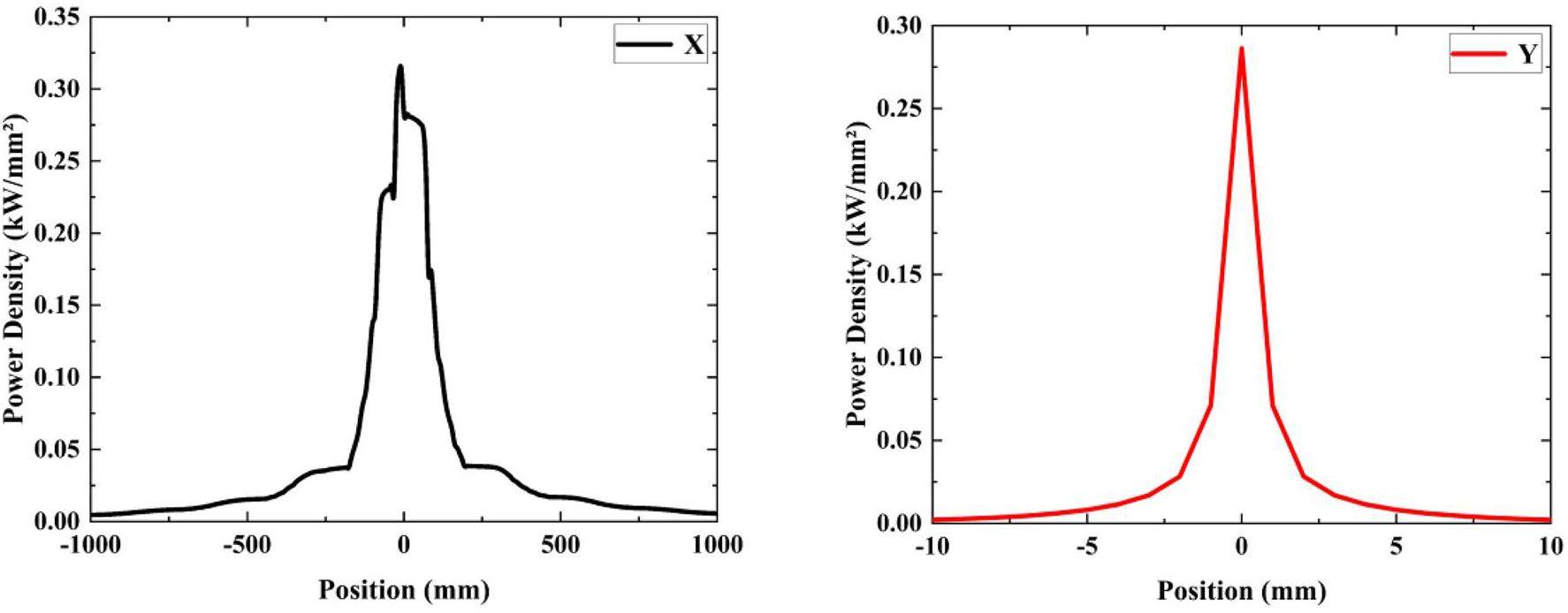

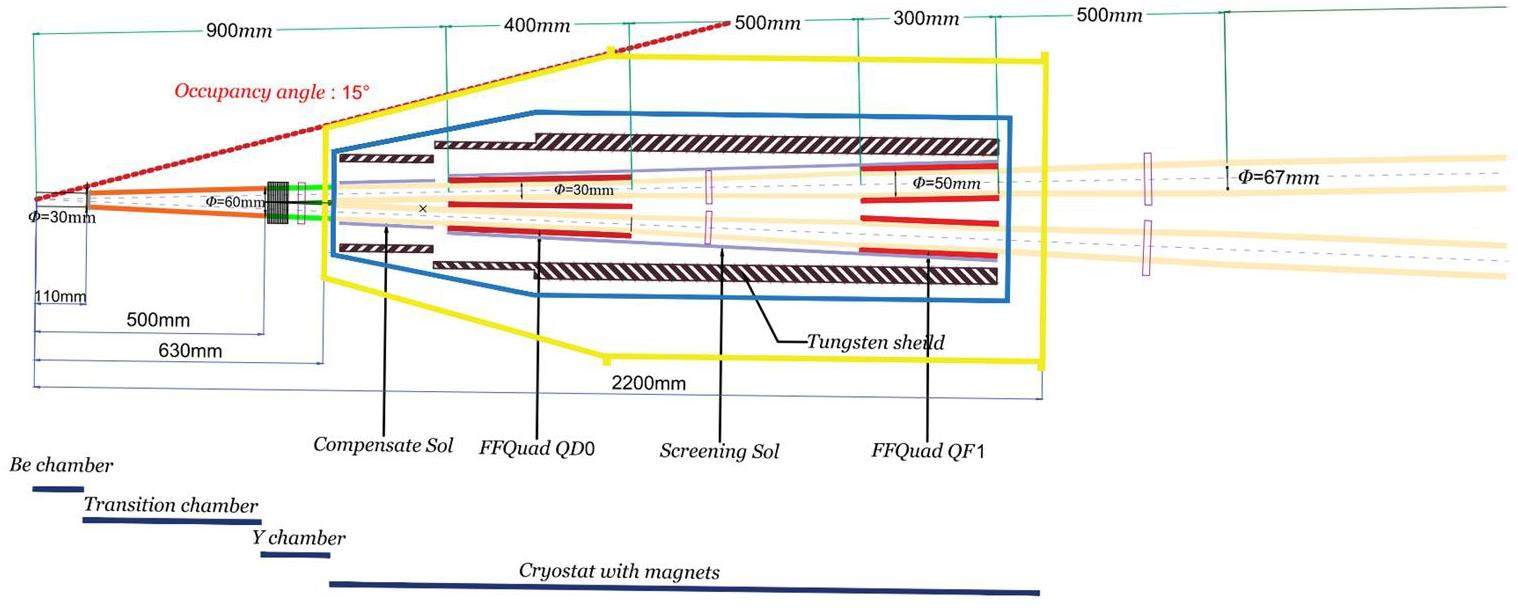

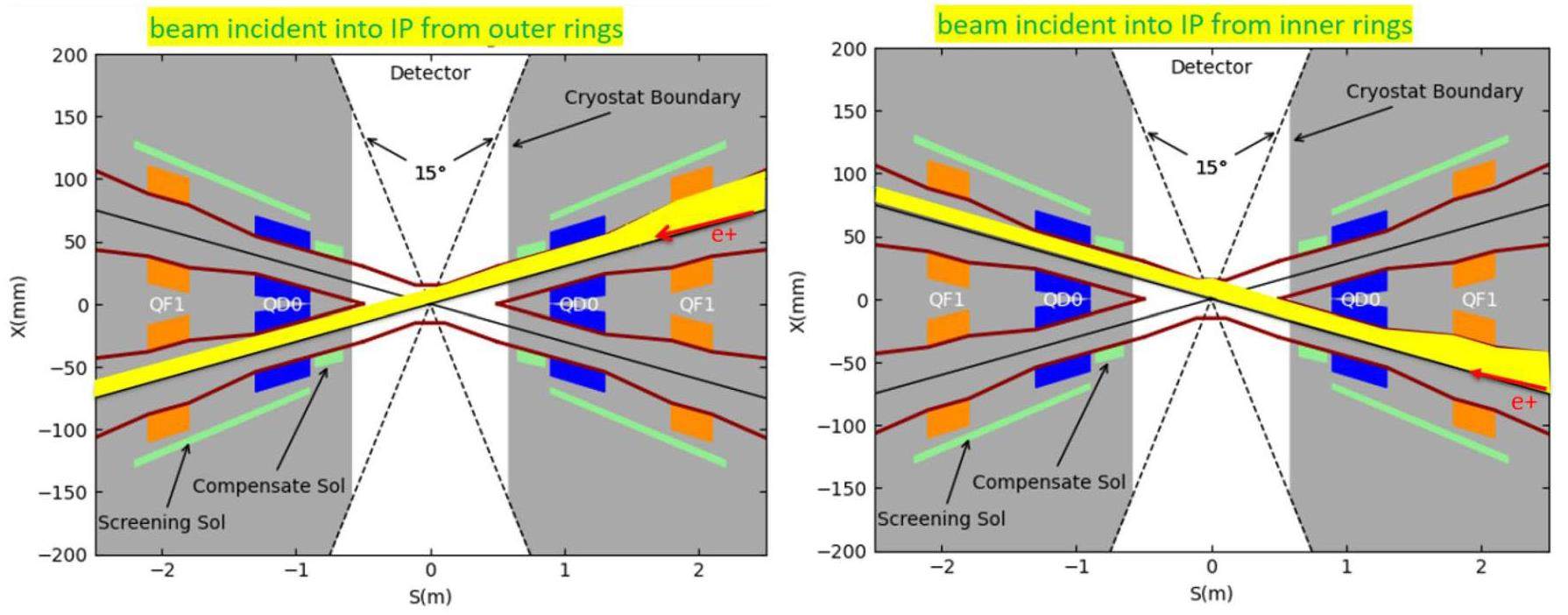

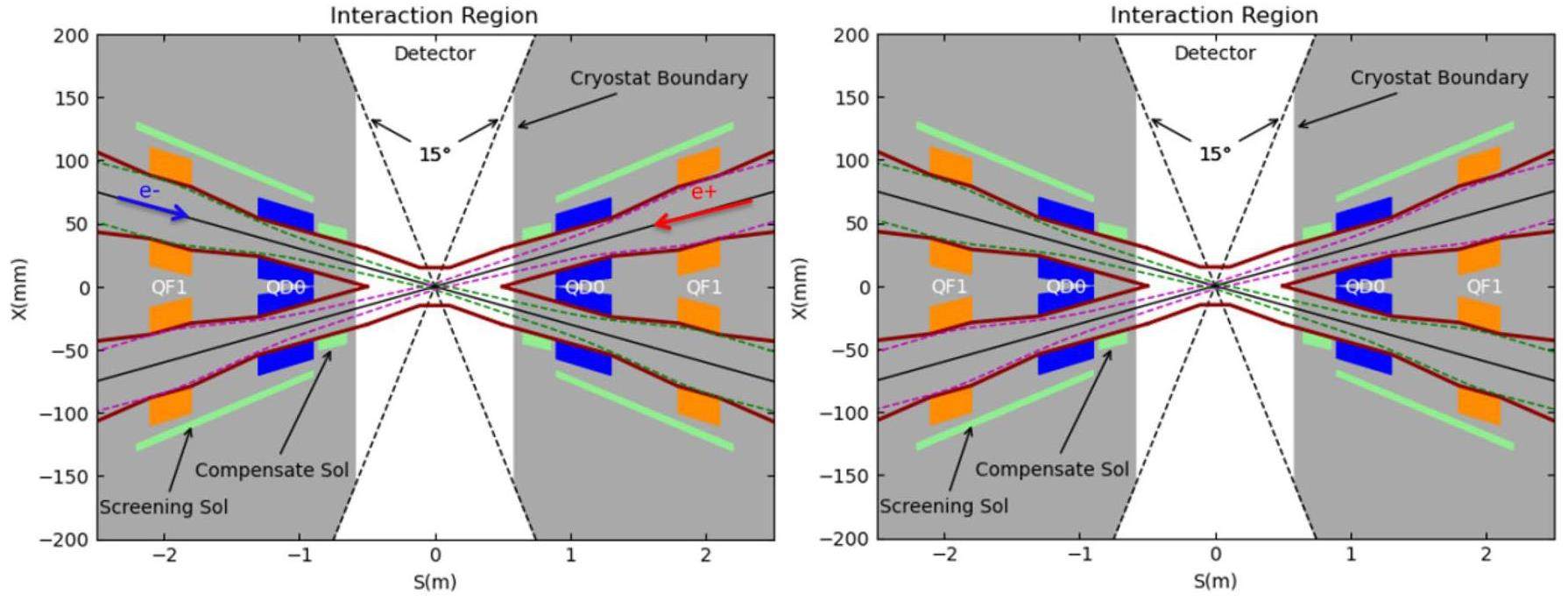

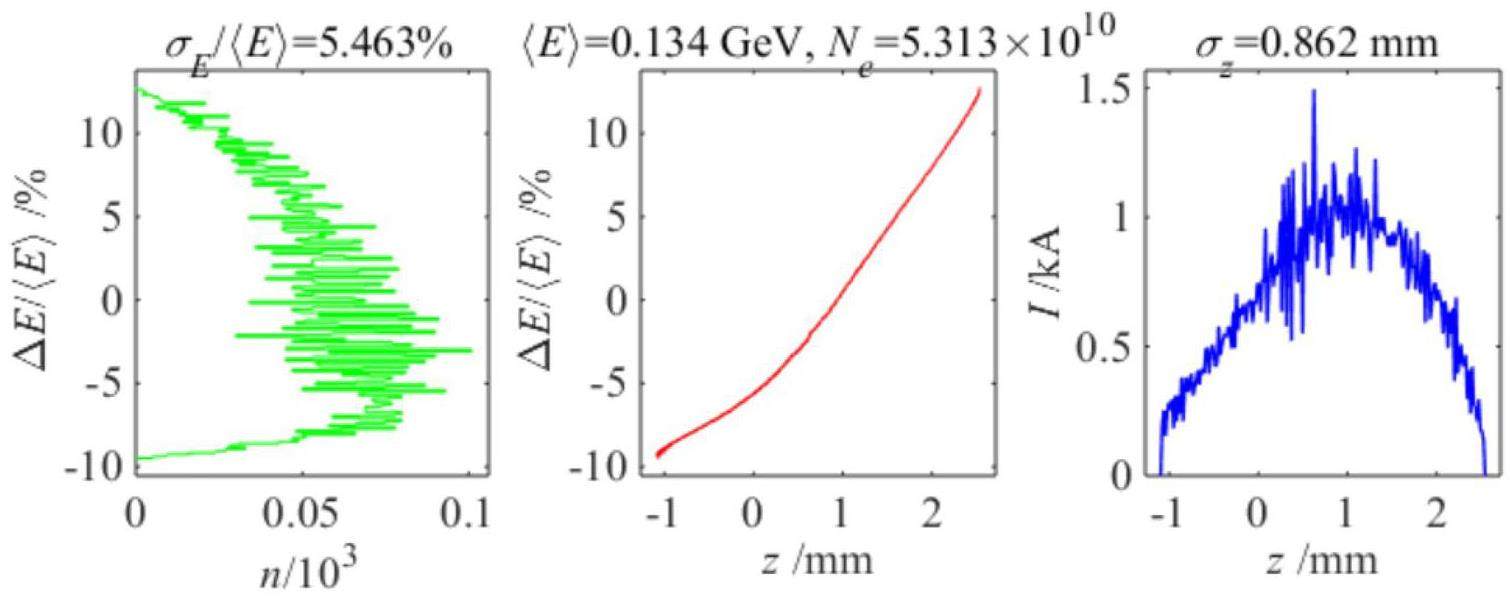

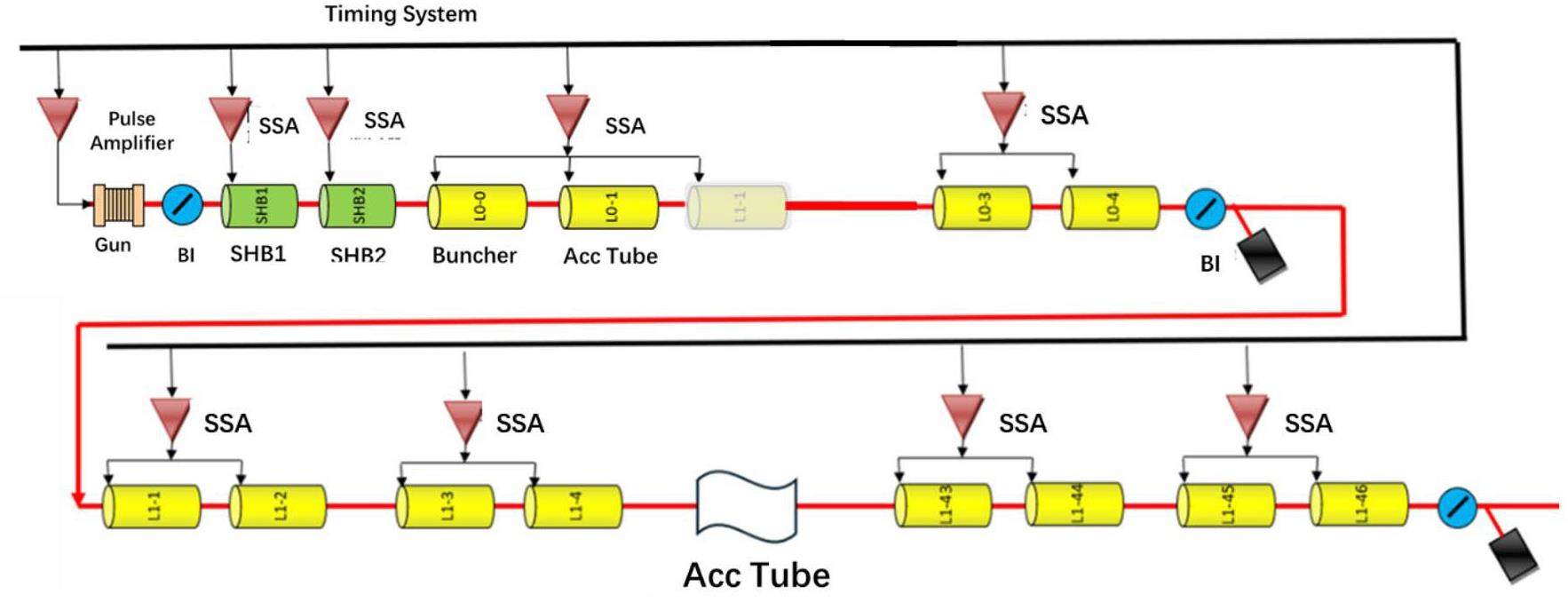

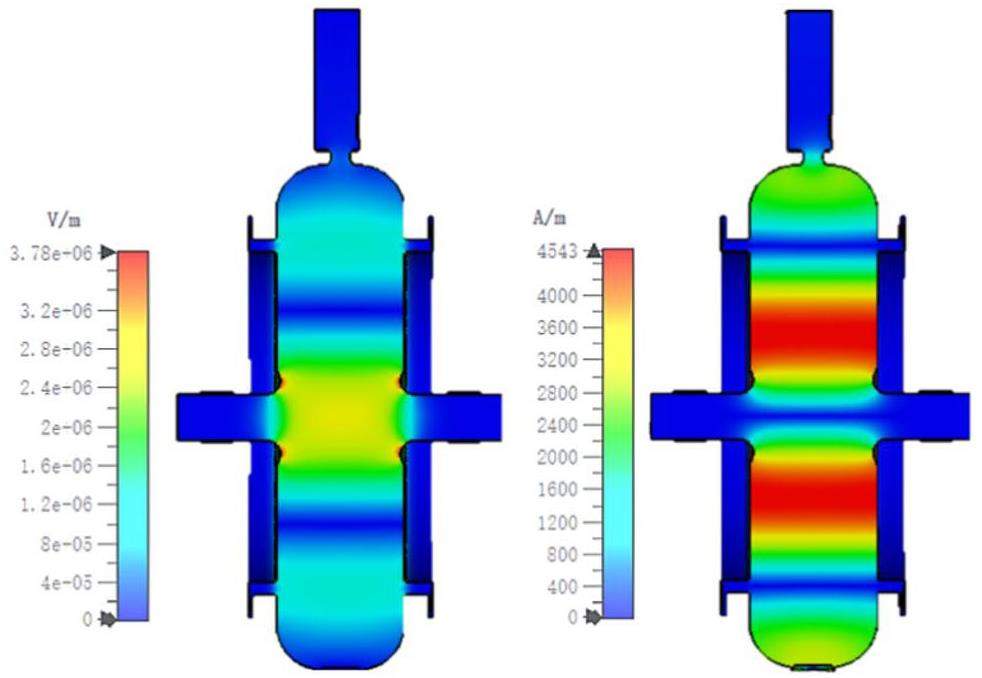

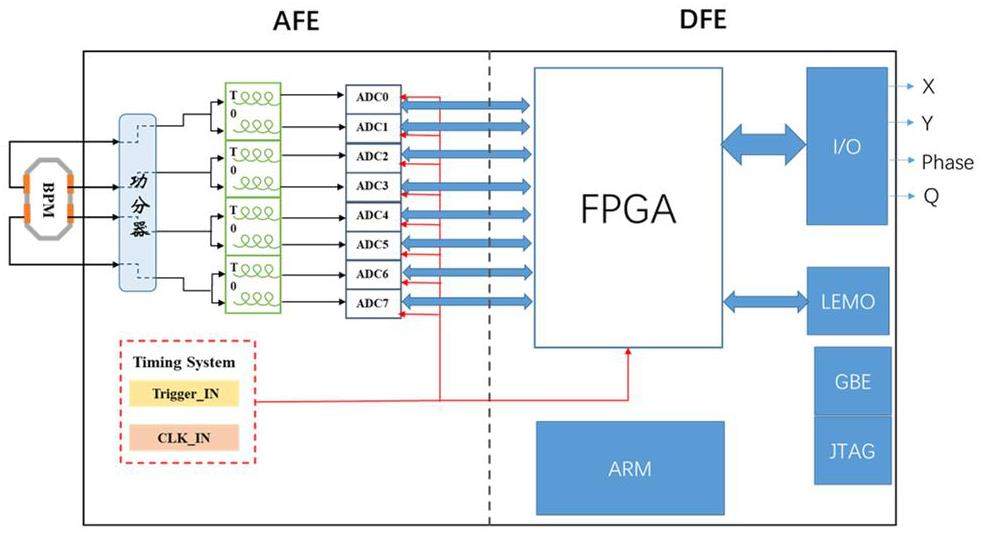

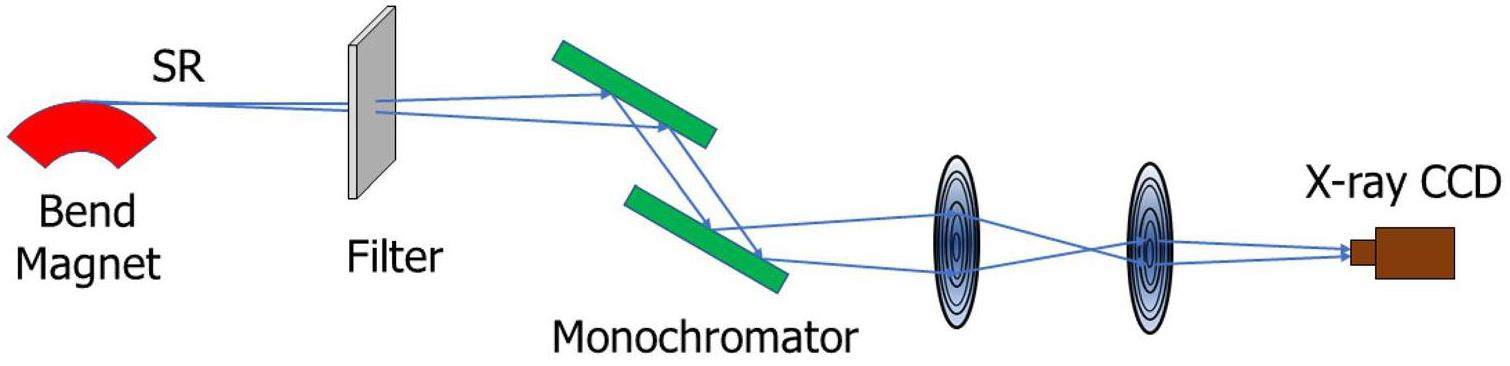

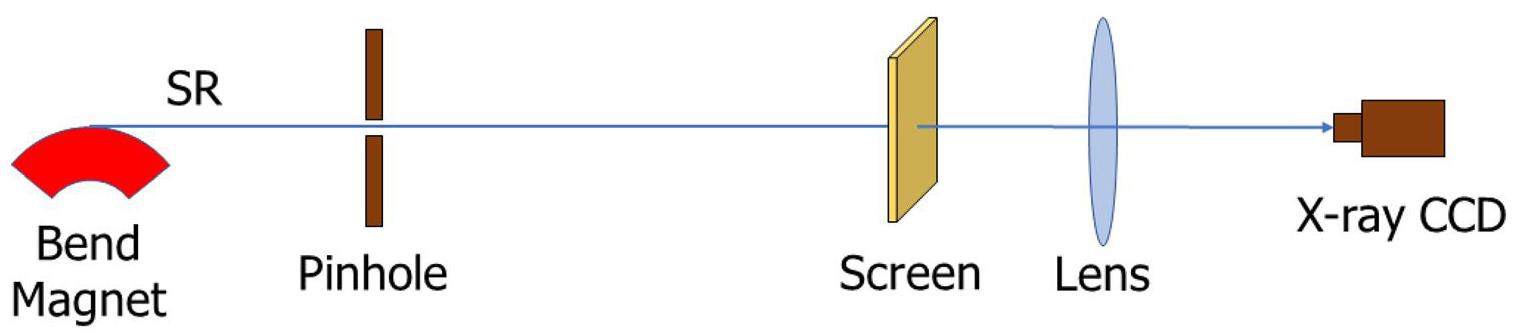

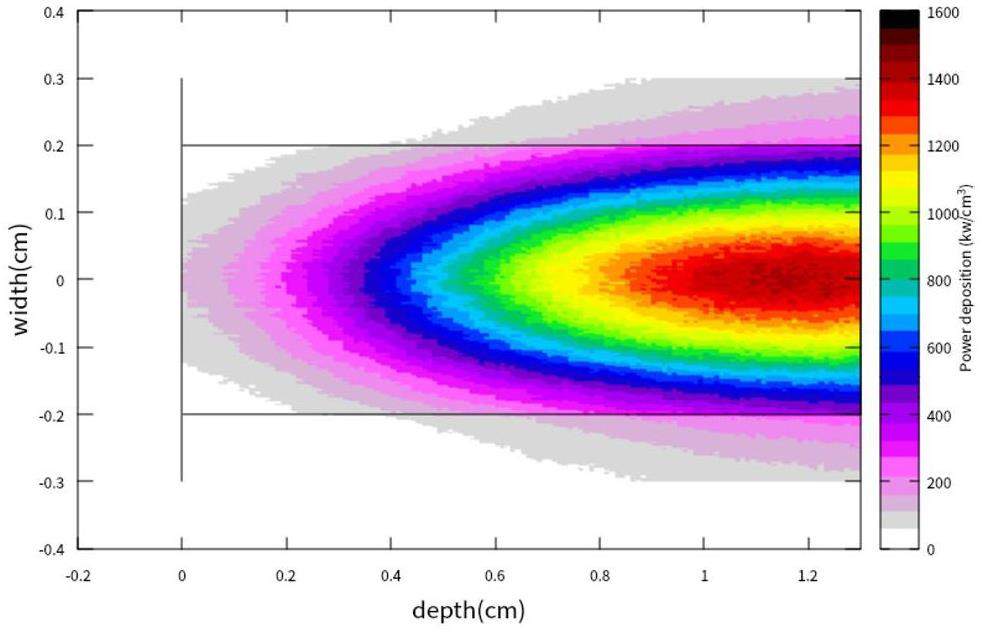

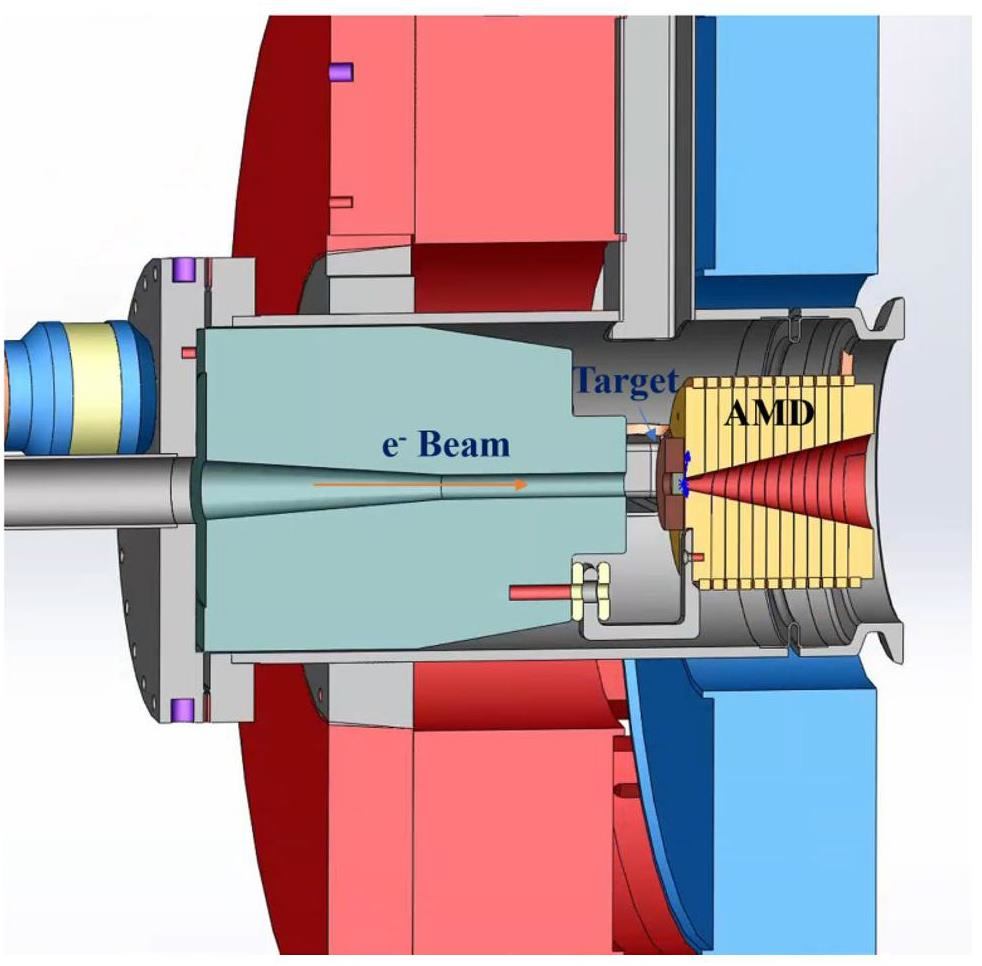

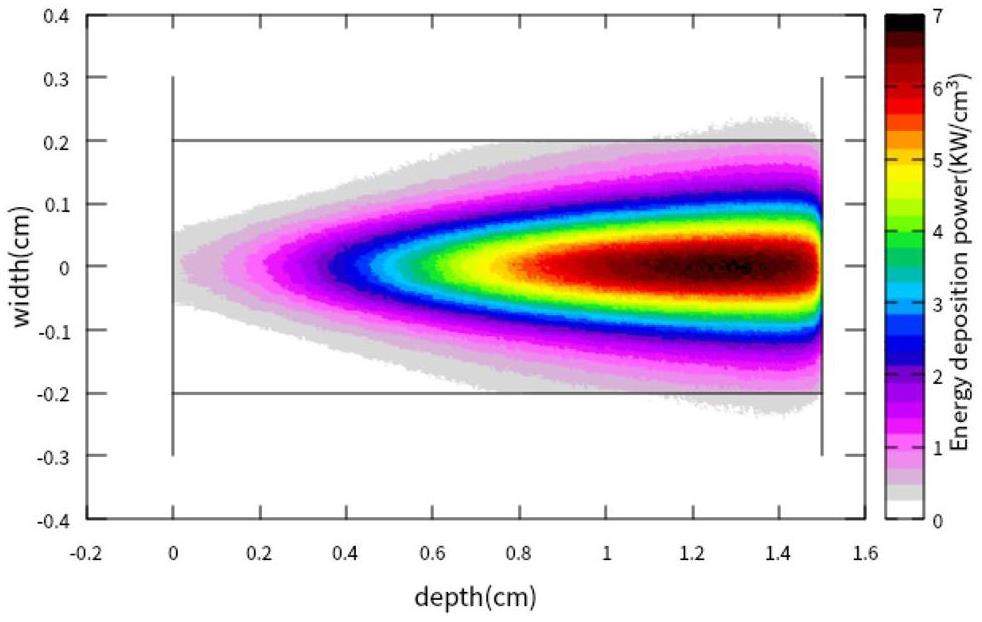

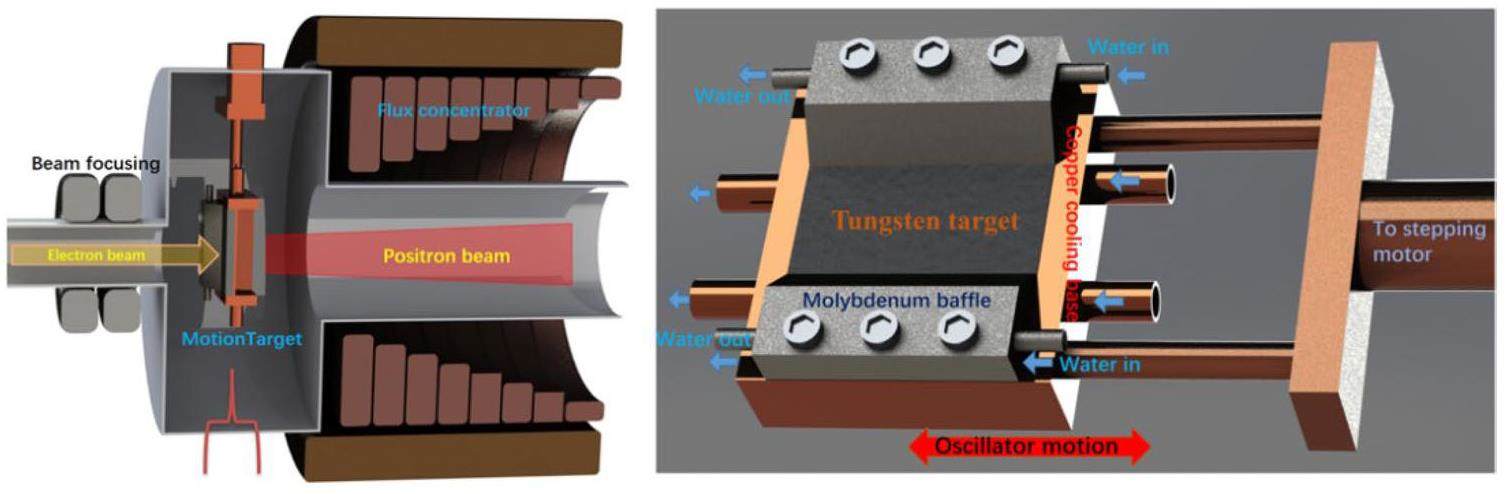

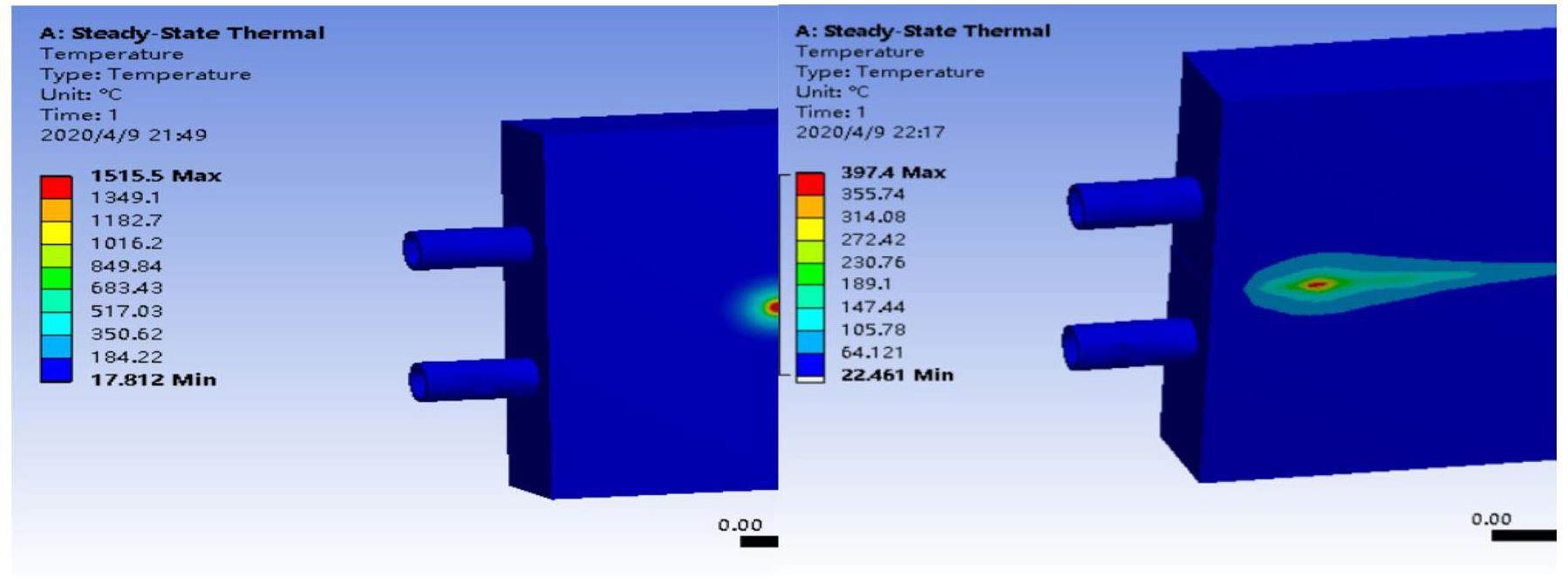

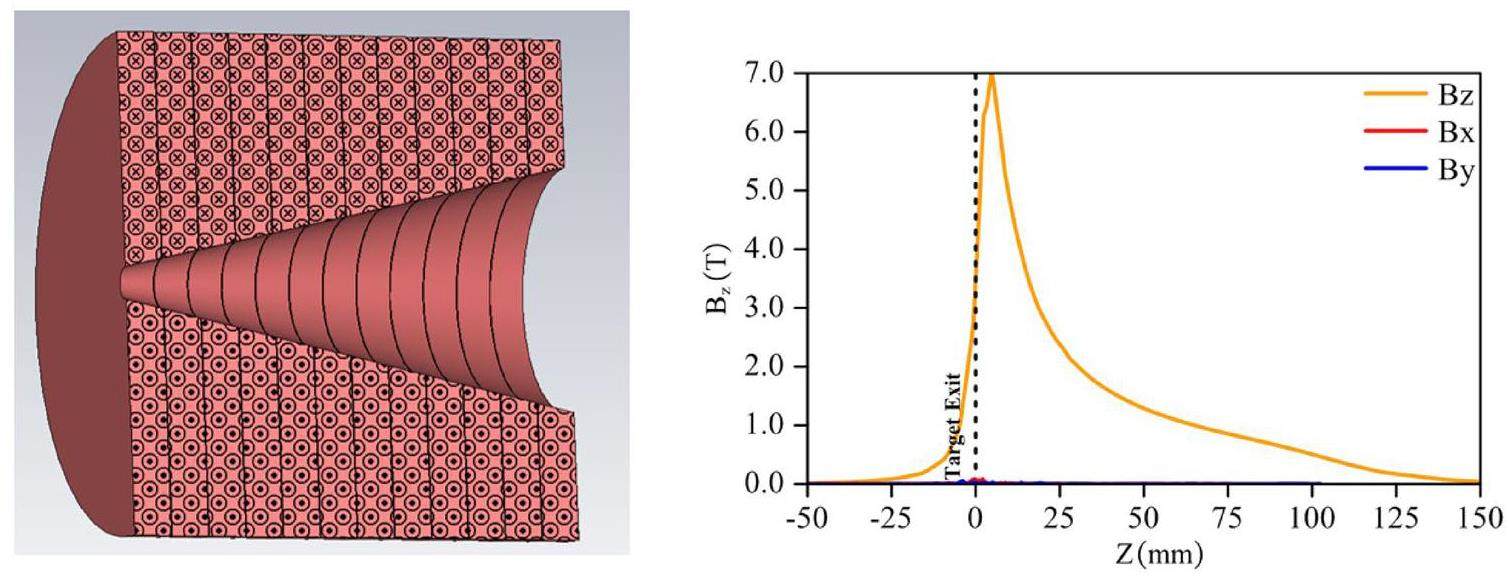

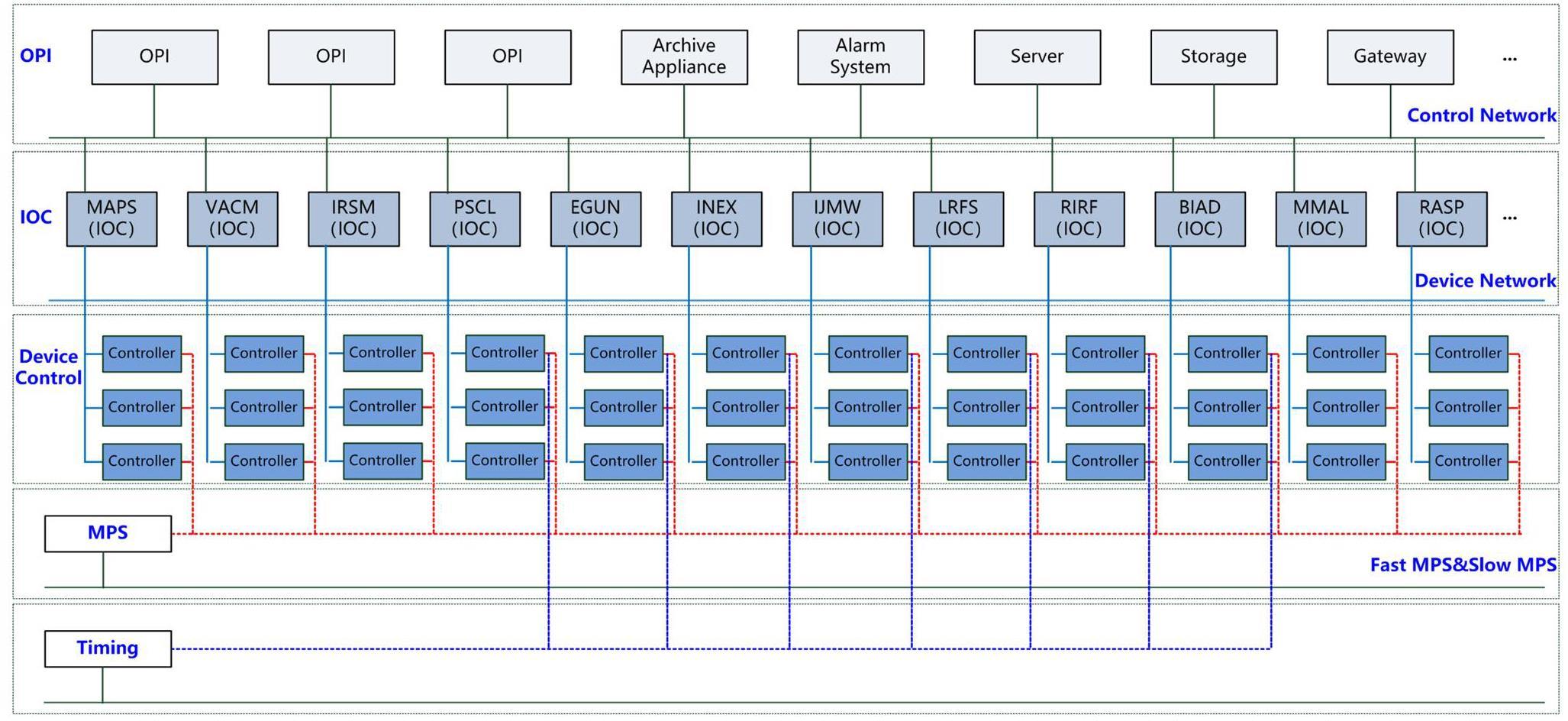

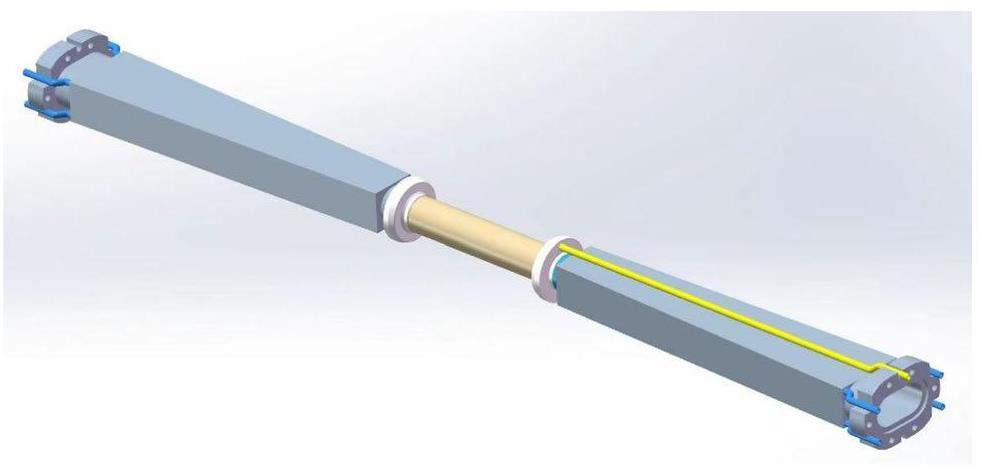

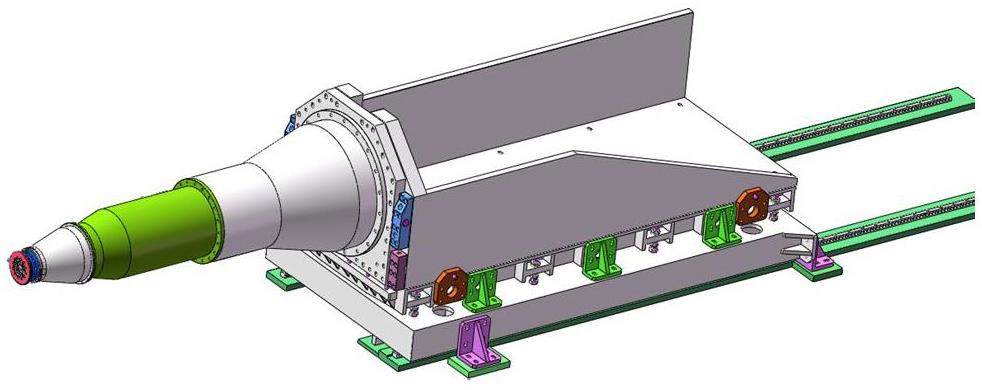

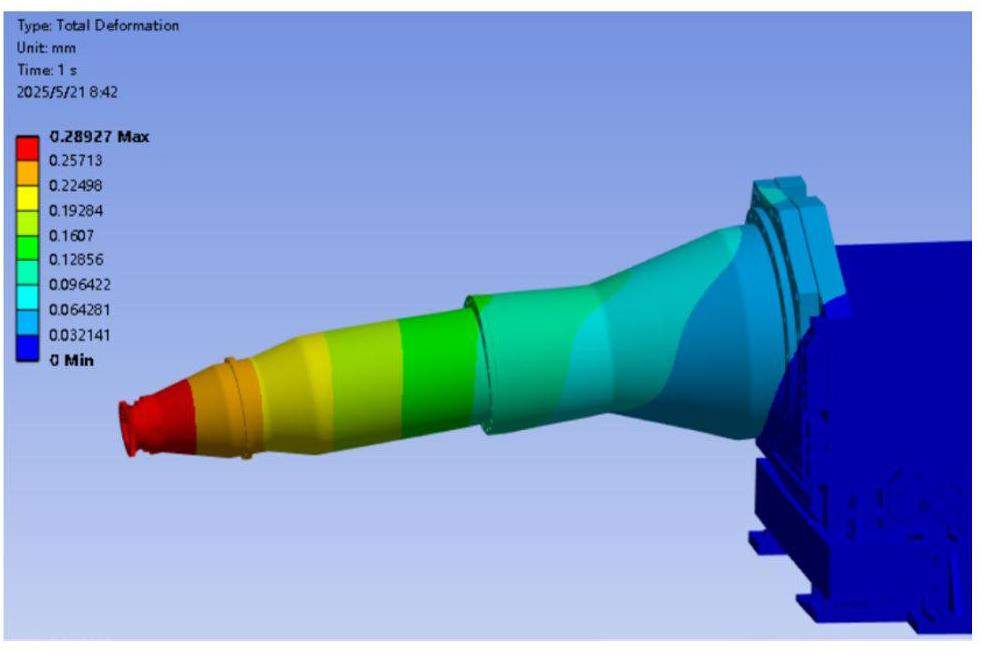

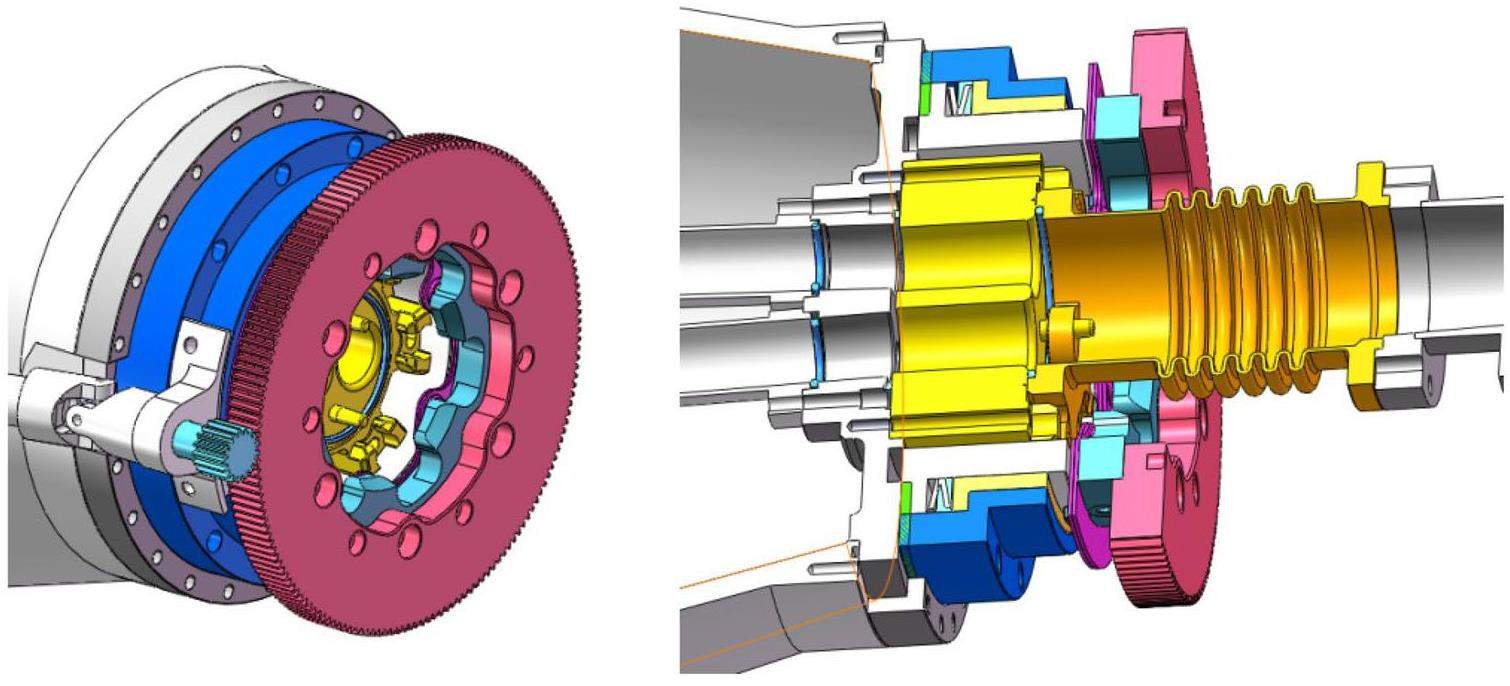

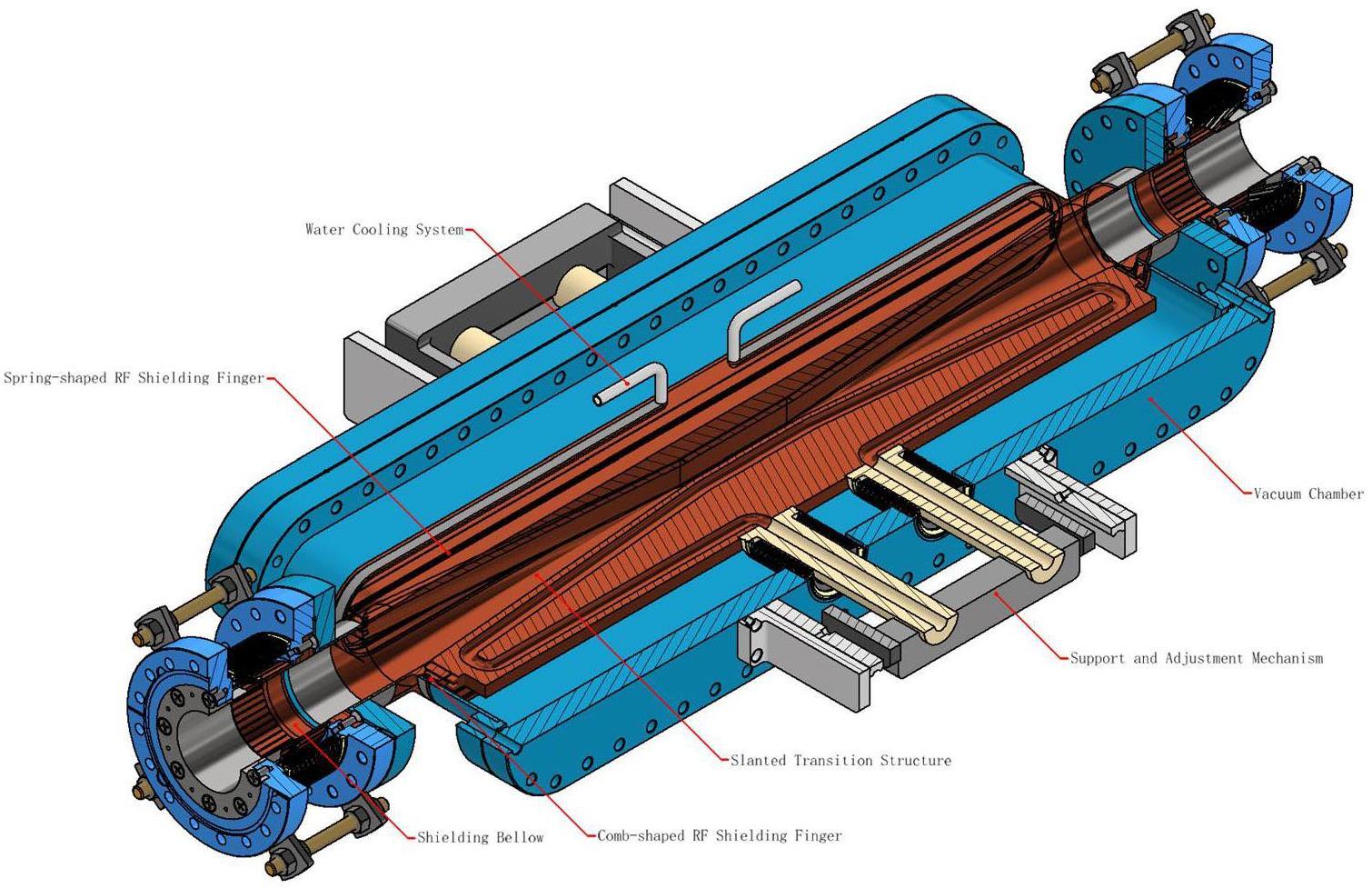

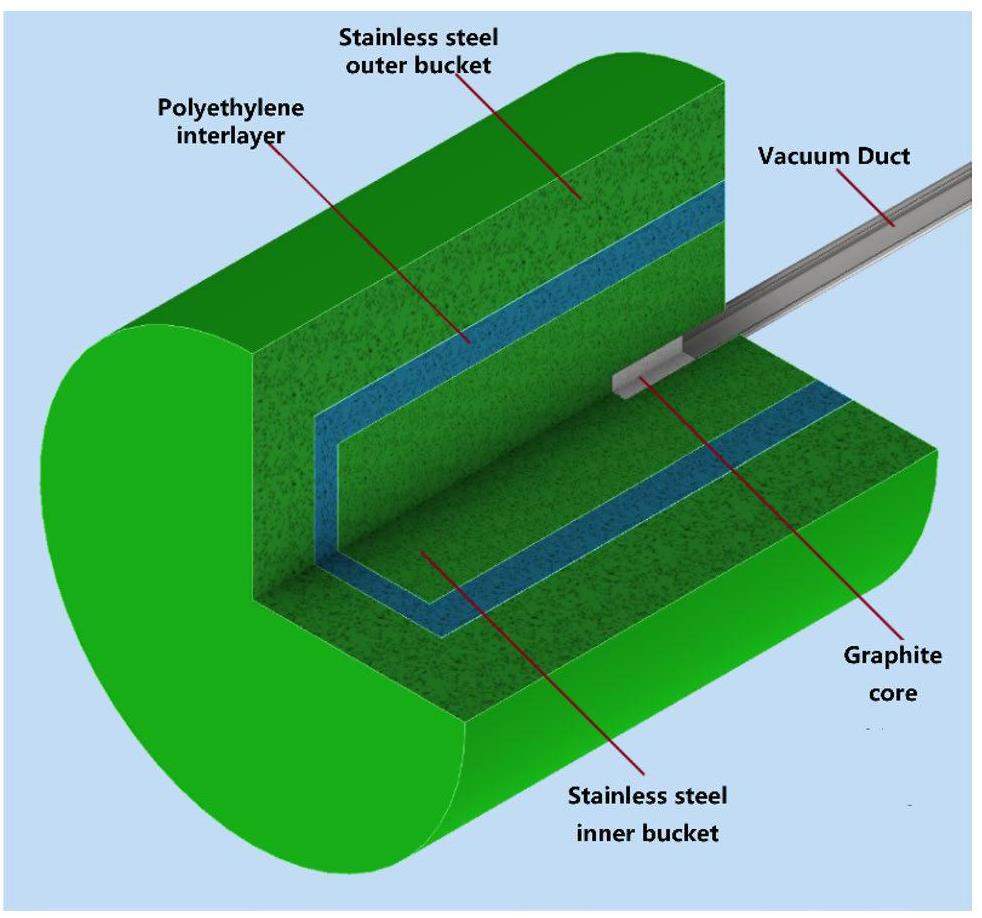

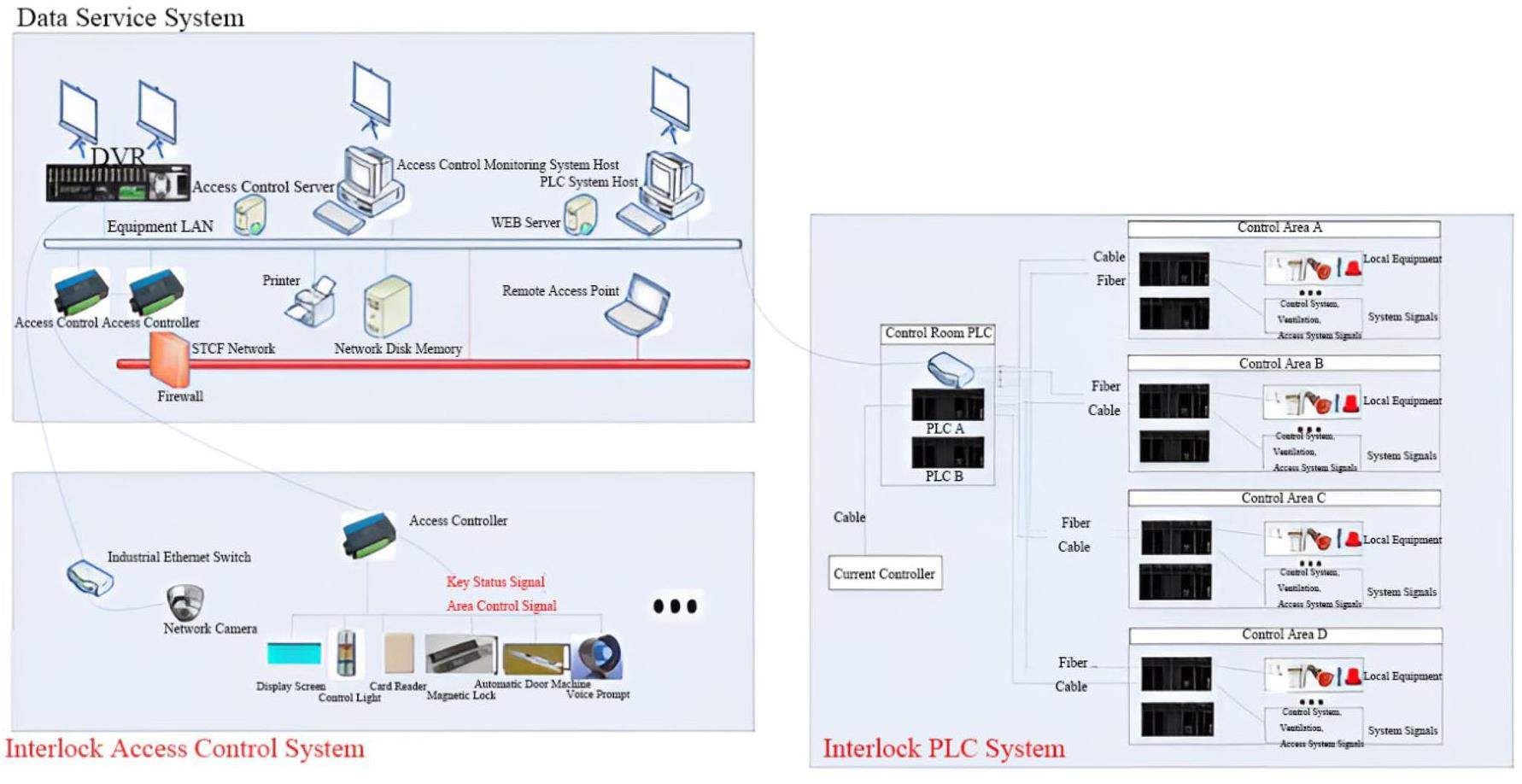

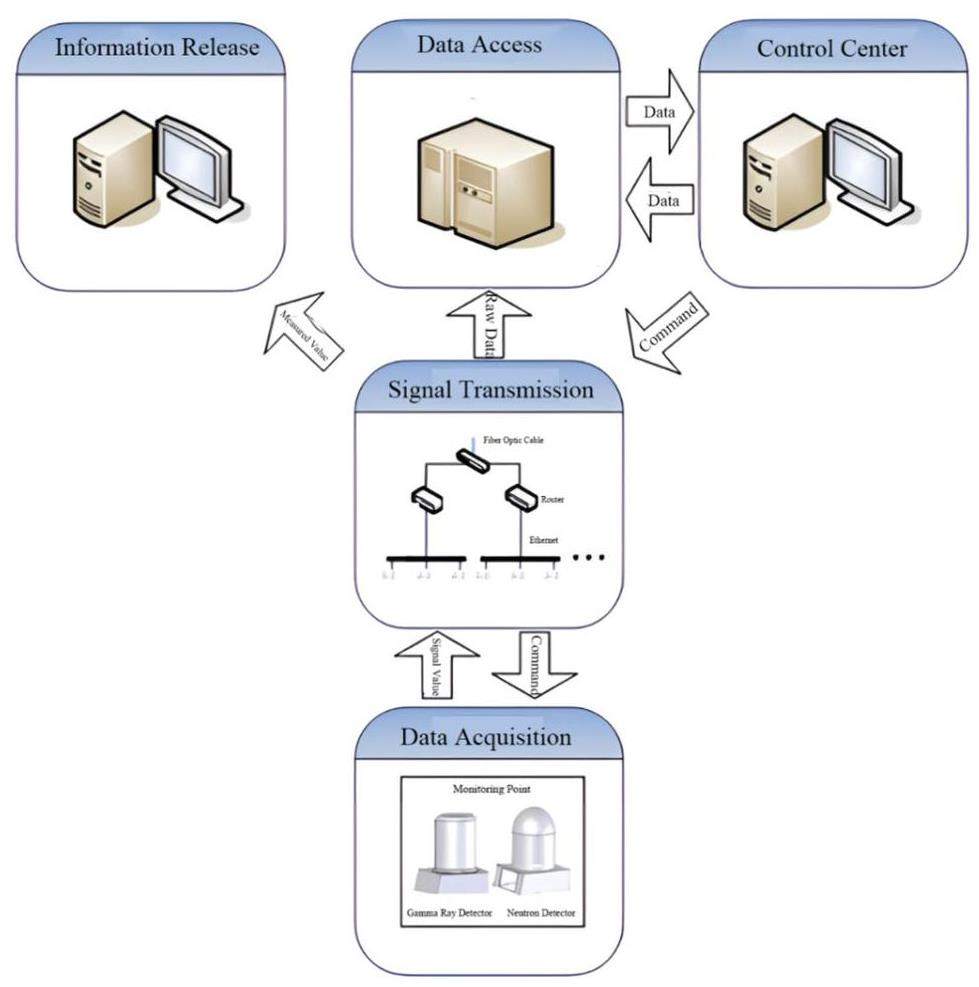

| Thick septum deflection angle (mrad) | 110 |