Introduction

In ultra-relativistic heavy ion collisions, light nuclei and hypernuclei such as deuteron (d), helium-3 (3He), triton (t), and hypertriton (

The production mechanisms of light nuclei and hypernuclei in ultra-relativistic heavy ion collisions have attracted considerable attention in experimental [25-28] and theoritical [29-32] research in the last few decades. The STAR experiment at the BNL Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) and the ALICE experiment at the CERN Large Hadron Collider (LHC) have been conducted to measure light nuclei [33-37] and hypernuclei [38-40]. Theoretical research has considered two popular production mechanisms, the thermal production mechanism [41-45] and the coalescence mechanism [46-50], which have been proven to be successful in describing the formation of such composite objects.

The coalescence mechanism, assuming light nuclei and hypernuclei are produced by the coalescence of the adjacent nucleons and hyperons in the phase space, exhibits certain unique characteristics such as the mass number scaling property [51-53] and nontrivial coalescence factor behavior [54-57]. To understand the extent to which these characteristics depend on the particular coalescence models used in obtaining these characteristics, we have developed an analytical model for describing the productions of different species of light nuclei, as reported in our previous works [58-61]. We applied the developed analytical nucleon coalescence model to Au+Au collisions at the RHIC to successfully explain the energy-dependent behaviors of d, t, 3He, and 4He [58, 59]. We also applied the model to pp, p+Pb, and Pb+Pb collisions at the LHC to understand different behaviors of coalescence factors B2 and B3 [60] from small to large collision systems, and a series of concise production correlations of d, 3He, and t [61] were presented.

Recently, the ALICE collaboration published the most precise measurements of d, 3He, t, and especially

The remainder of this manuscript is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the coalescence model and presents the formulae of the momentum distributions of two baryons coalescing into dibaryon states and three baryons coalescing into tribaryon states. Section 3 presents the behaviors of B2 and B3 evaluated as functions of the collision centrality and the transverse momentum per nucleon. Furthermore, the transverse momentum (pT) spectra, averaged transverse momenta

Coalescence model

This section presents the extension of the analytical nucleon coalescence model developed in our previous work [61] to include the hyperon coalescence. The current model executes the coalescence process on an equivalent kinetic freeze-out surface formed from different times. To realize the analytical and intuitive insights, we eliminate the systematic time-evolution execution and utilize the finite emission duration in an effective volume. First, the formalism of two baryons coalescing into d-like dibaryon states is explained. Subsequently, an analytical expression of three baryons coalescing into 3He, t, and their partners in the strange sector is presented.

Formalism of two bodies coalescing into dibaryon states

Starting with a hadronic system produced at the final stage of the evolution of high-energy collisions, we consider that the dibaryon state Hj is formed via the coalescence of two baryons h1 and h2. We use

In terms of the normalized joint coordinate–momentum distribution denoted by the superscript ‘(n)’, we have

The kernel function

Substituting Eqs. (3) and (4) into Eq. (2), we have

Notably, the root-mean-square radius

Changing coordinate variables in Eq. (7) to

With instantaneous coalescence in the rest frame of the h1h2-pair, i.e., Δt’=0, we get the coordinate transformation

Formalism of three bodies coalescing into tribaryon states

For tribaryon state Hj formed via the coalescence of three baryons h1, h2, and h3, the momentum distribution

The kernel function can be modified as

Results of light nuclei

This section presents the use of the coalescence model to study productions of d,

Coalescence factor of light nuclei

The coalescence factor BA is defined as

To further compute B2 and B3, the specific form of Rf(pT) is necessary. Similar to Ref. [61], the dependence of Rf(pT) on centrality and pT is considered to factorize into a linear dependence on the cube root of the pseudorapidity density of charged particles

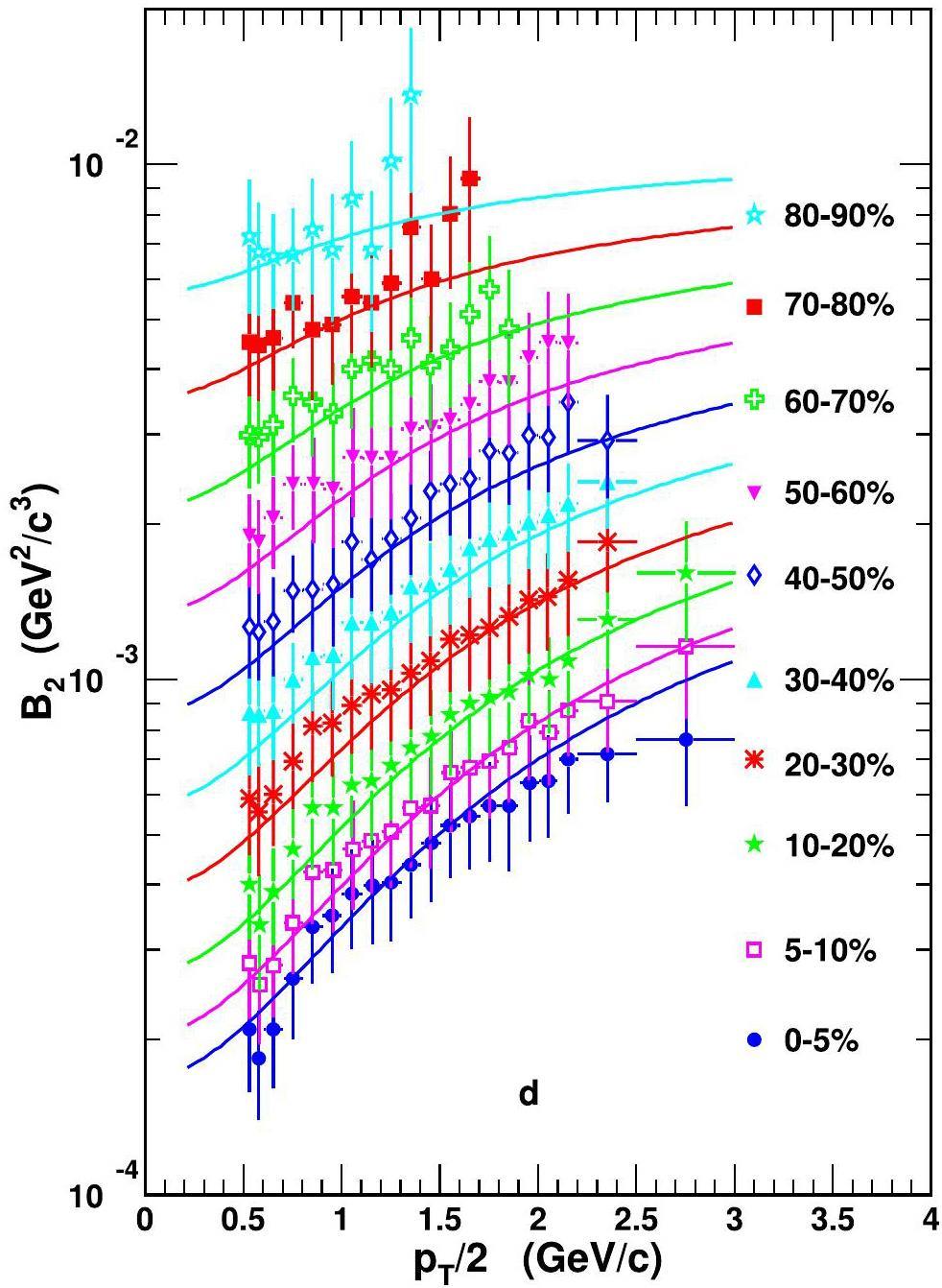

We used the data of dNch/dη reported in Ref. [80] to evaluate Rf(pT) and computed the coalescence factors B2 and B3. Figure 1 shows B2 of d as a function of the transverse momentum scaled by the mass number pT/2 in different centralities in Pb+Pb collisions at

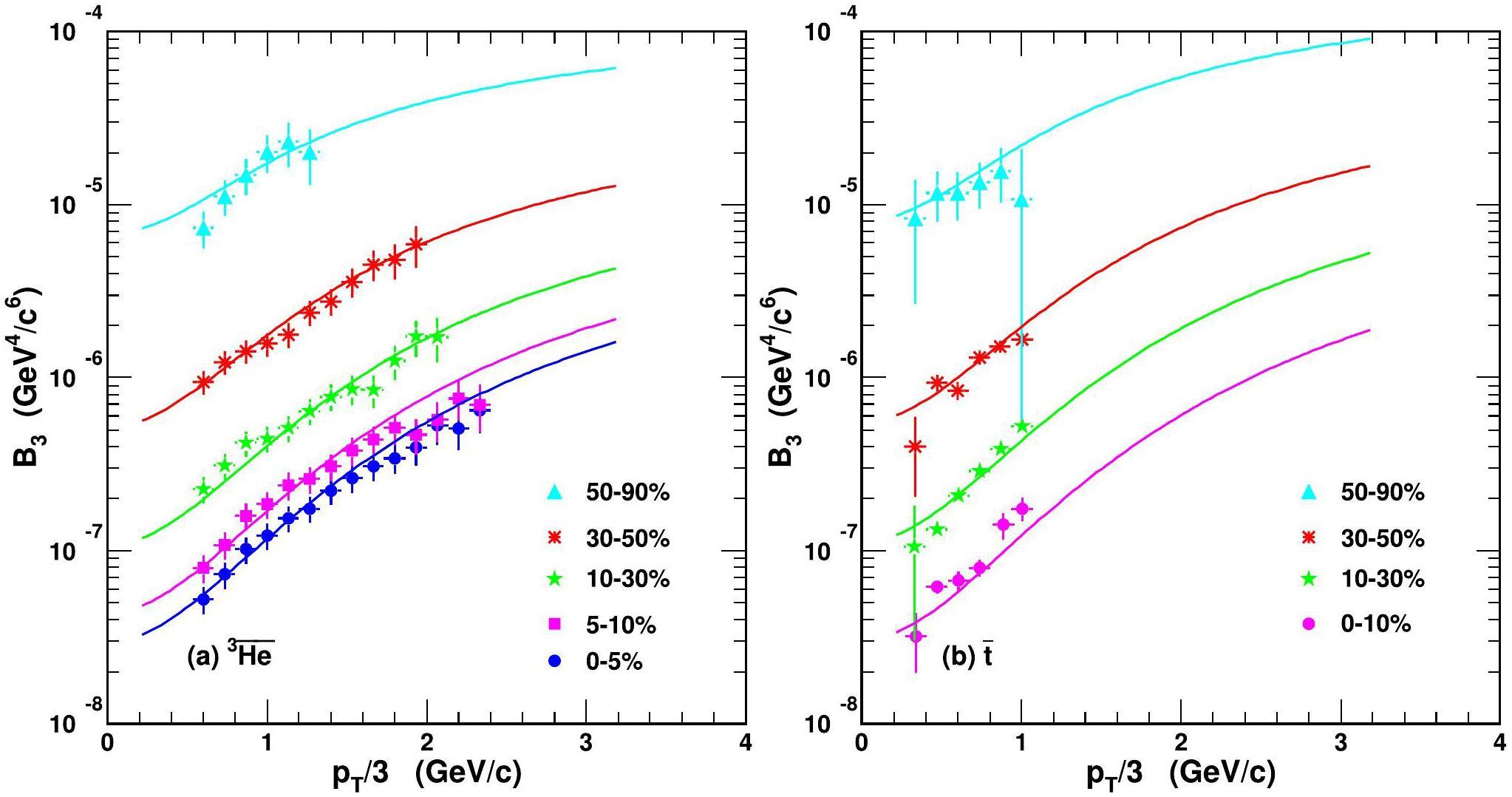

Figure 2 shows B3 of

pT spectra of light nuclei

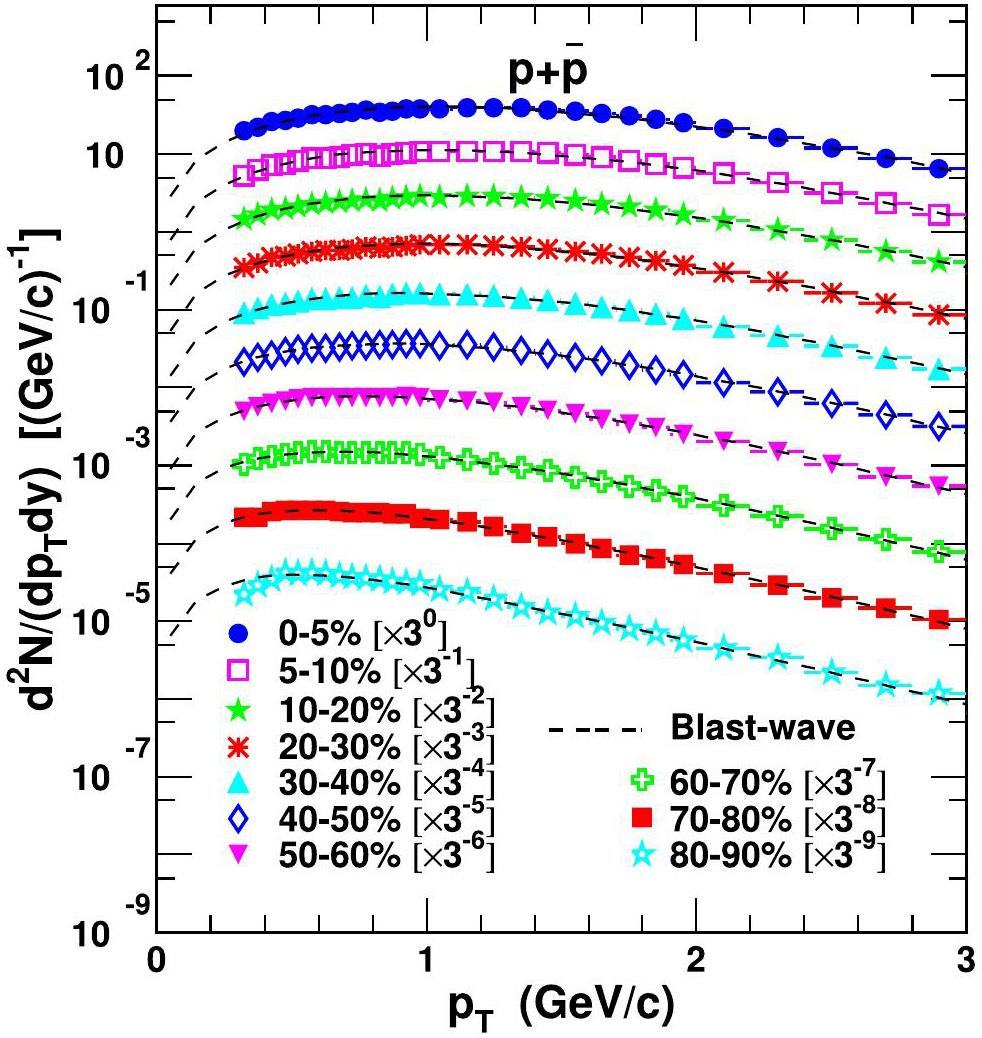

The pT spectra of primordial nucleons are necessary inputs for computing pT distributions of light nuclei in the coalescence model. Here, we used the blast-wave model to get pT distribution functions of primordial protons by fitting the experimental data of prompt (anti)protons, as reported in Ref. [80]. The blast-wave function [81] is given as

Figure 3 shows the pT spectra of prompt protons plus antiprotons in different centralities in Pb+Pb collisions at

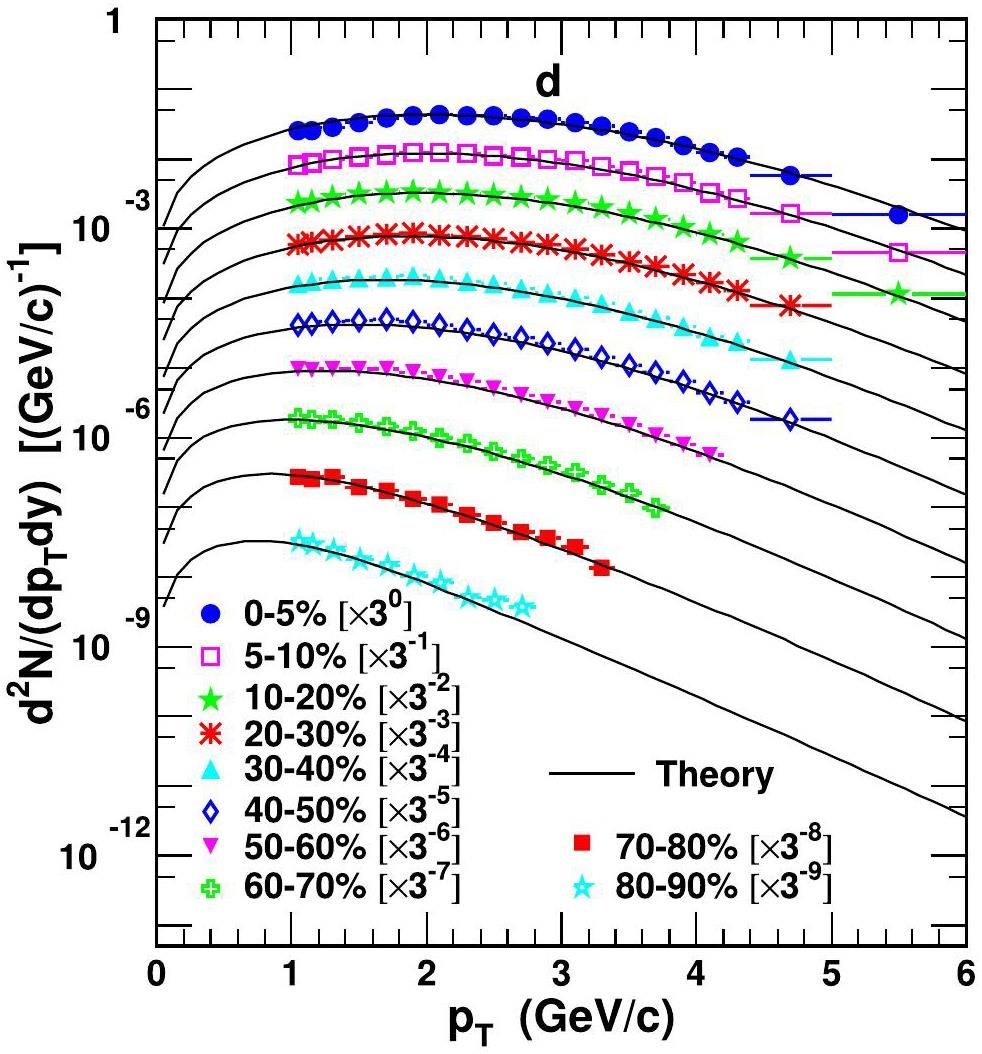

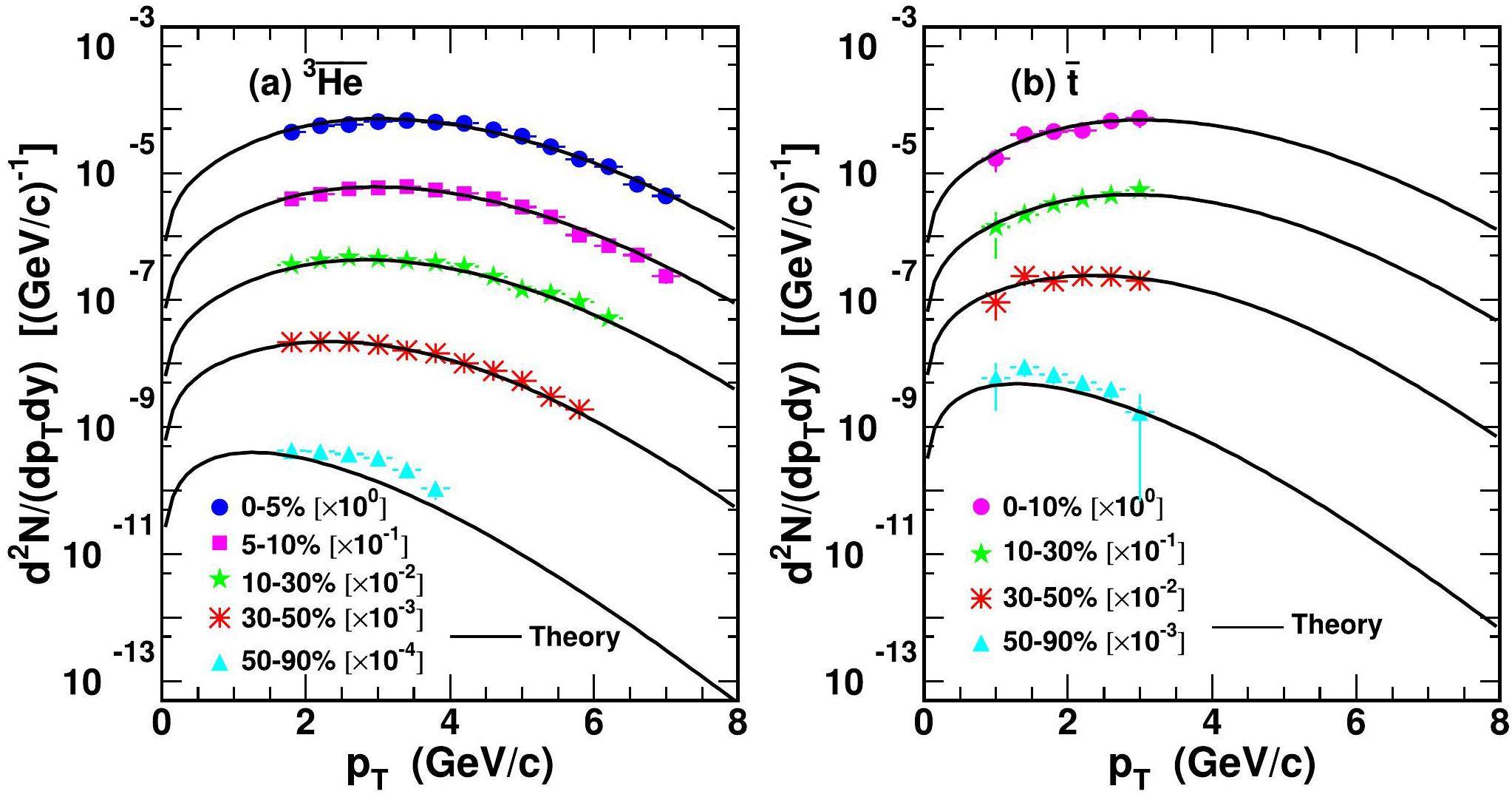

First, the pT spectra of deuterons in Pb+Pb collisions at

Averaged transverse momenta and yield rapidity densities of light nuclei

The averaged transverse momenta

| Centrality | dN/dy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data | Theory | Data | Theory | ||

| d | 0–5% | 2.45±0.00±0.09 | 2.37 | (1.19±0.00±0.21)×10-1 | 1.22×10-1 |

| 5–10% | 2.41±0.01±0.10 | 2.33 | (1.04±0.00±0.19)×10-1 | 1.01×10-1 | |

| 10–20% | 2.34±0.00±0.11 | 2.28 | (8.42±0.02±1.50)×10-2 | 7.86×10-2 | |

| 20–30% | 2.21±0.00±0.12 | 2.18 | (6.16±0.02±1.10)×10-2 | 5.58×10-2 | |

| 30–40% | 2.05±0.00±0.12 | 2.04 | (4.25±0.01±0.75)×10-2 | 3.82×10-2 | |

| 40–50% | 1.88±0.01±0.12 | 1.87 | (2.73±0.01±0.48)×10-2 | 2.46×10-2 | |

| 50–60% | 1.70±0.01±0.11 | 1.66 | (1.62±0.01±0.28)×10-2 | 1.47×10-2 | |

| 60–70% | 1.46±0.01±0.12 | 1.45 | (8.35±0.14±1.43)×10-3 | 7.58×10-3 | |

| 70–80% | 1.27±0.02±0.11 | 1.25 | (3.52±0.06±0.63)×10-3 | 3.22×10-3 | |

| 80–90% | 1.09±0.02±0.40 | 1.10 | (1.13±0.03±0.23)×10-3 | 0.925×10-3 | |

| 0–5% | 3.465±0.013±0.154±0.144 | 3.26 | (24.70±0.28±2.29±0.30)×10-5 | 25.6×10-5 | |

| 5–10% | 3.368±0.014±0.141±0.132 | 3.21 | (20.87±0.26±1.95±0.43)×10-5 | 21.4×10-5 | |

| 10–30% | 3.237±0.021±0.157±0.150 | 3.08 | (15.94±0.31±1.53±0.34)×10-5 | 14.8×10-5 | |

| 30–50% | 2.658±0.016±0.084±0.049 | 2.64 | (7.56±0.13±0.70±0.10)×10-5 | 7.16×10-5 | |

| 50–90% | 2.057±0.023±0.090±0.027 | 1.77 | (1.19±0.08±0.16±0.14)×10-5 | 0.931×10-5 | |

| 0–10% | 3.368±0.241±0.060 | 3.27 | (24.45±1.75±2.71)×10-5 | 24.6×10-5 | |

| 10–30% | 3.015±0.286±0.040 | 3.11 | (14.19±1.35±1.29)×10-5 | 15.9×10-5 | |

| 30–50% | 2.524±0.593±0.180 | 2.68 | (7.24±1.70±0.65)×10-5 | 7.97×10-5 | |

| 50–90% | 1.636±0.226±0.040 | 1.80 | (1.66±0.23±0.16)×10-5 | 1.14×10-5 | |

Yield ratios of light nuclei

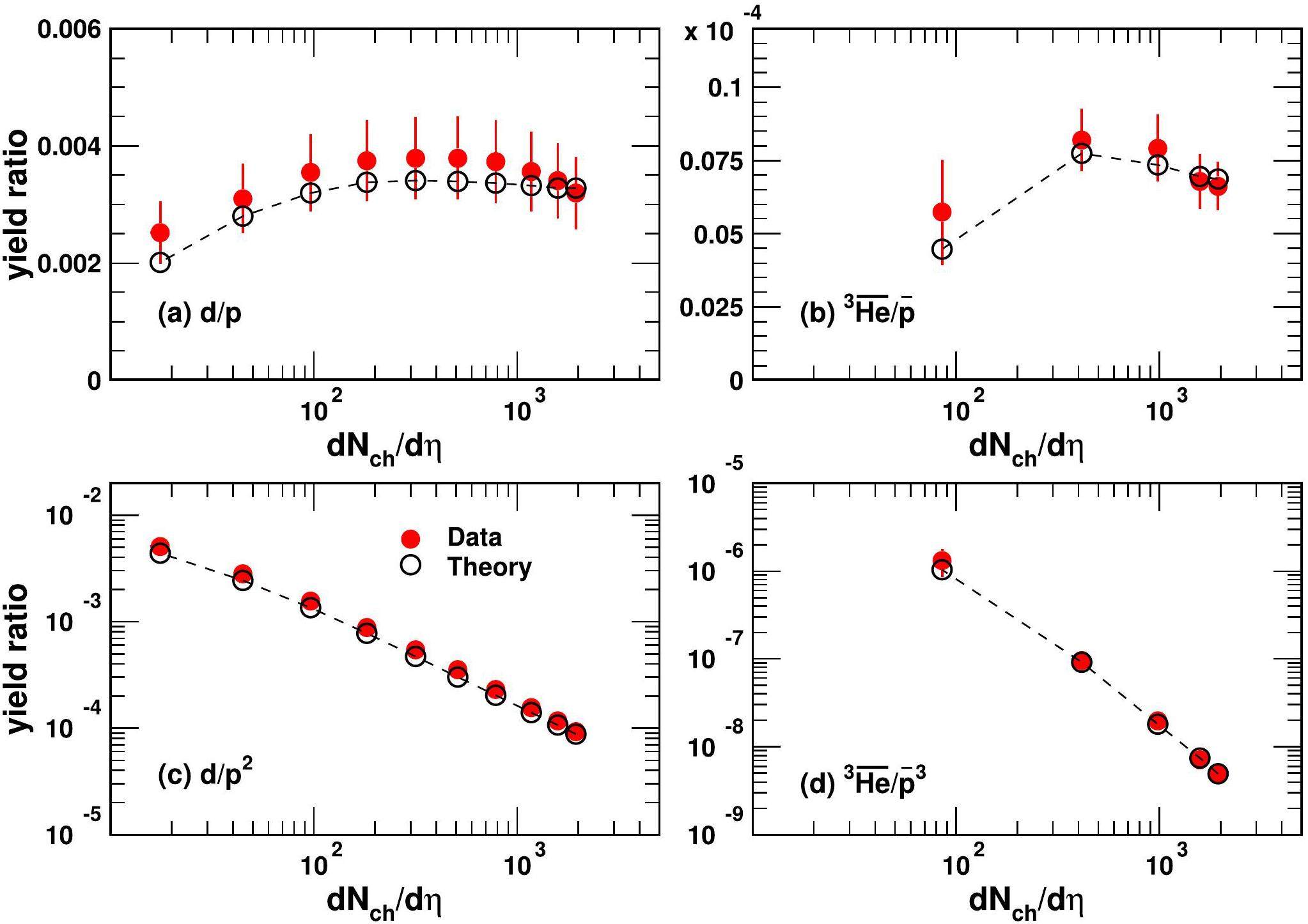

Yield ratios carry information on the intrinsic production correlations of different light nuclei and are predicted to exhibit nontrivial behaviors [61]. This subsection presents the centrality dependence of different yield ratios, such as d/p,

Figure 6(a) and (b) show the dNch/dη dependence of d/p and

Figure 6(c) and (d) show d/p2 and

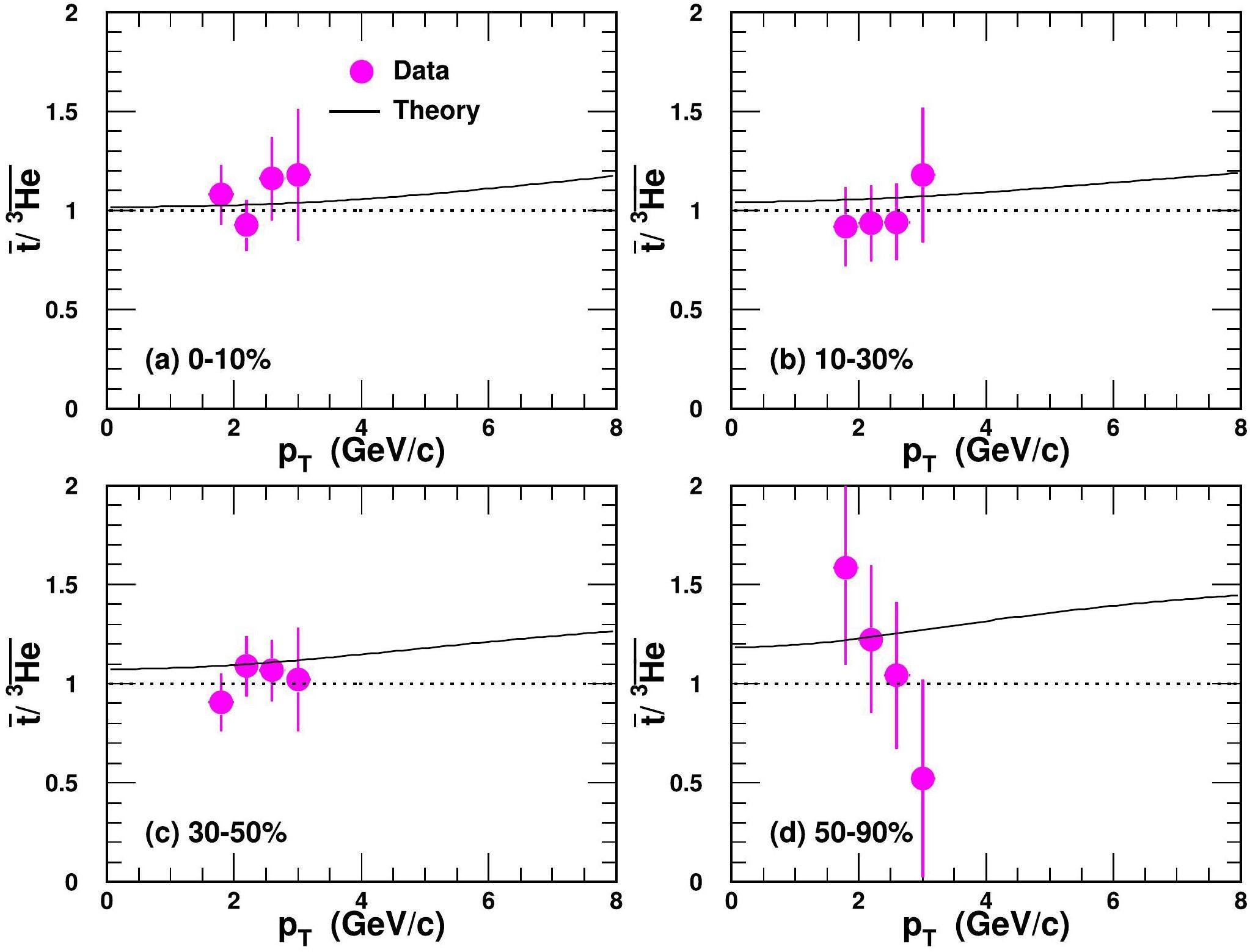

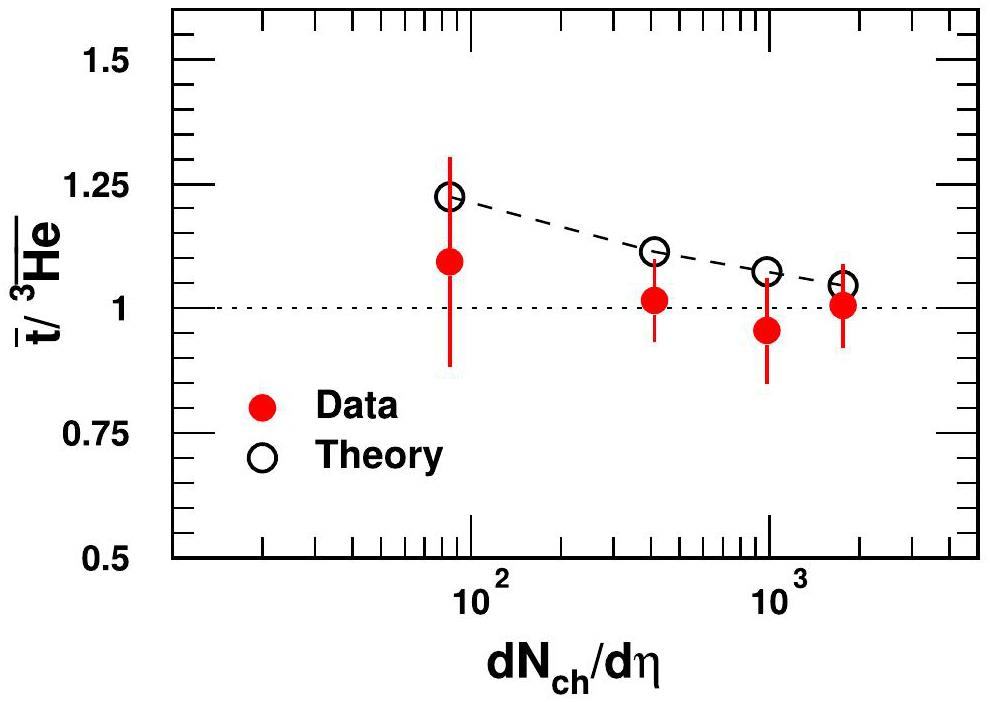

Therefore, a yield ratio t/3He is proposed as a valuable probe to distinguish the thermal and coalescence productions for light nuclei [61]. In the coalescence framework, the ratio is always greater than one and approaches one at large Rf values, where the suppression effect from the nucleus size can be ignored. The smaller the

The pT-integrated yield ratio

Results of hypertriton and Ω-hypernuclei

This section presents the use of the coalescence model presented in Sect. 2 to study the production of the hypertriton

pT spectra of Λ and Ω- hyperons

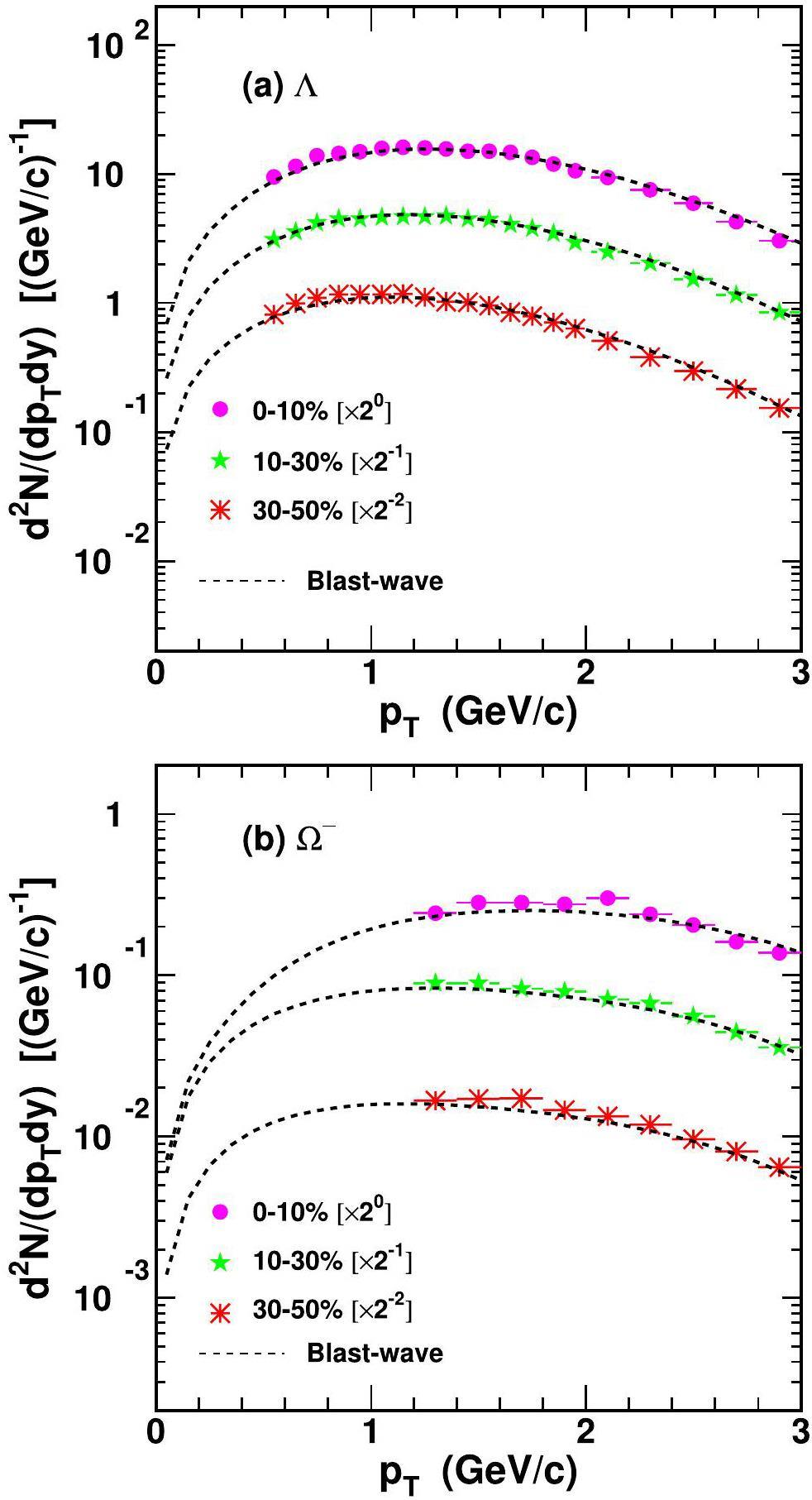

The pT spectra of Λ and Ω- hyperons are necessary for computing pT distributions of

| Centrality | Tkin (GeV) | n | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Λ | 0–10% | 0.090 | 0.670 | 0.64 |

| 10–30% | 0.092 | 0.648 | 0.70 | |

| 30–50% | 0.095 | 0.622 | 0.78 | |

| 0–10% | 0.095 | 0.627 | 0.78 | |

| 10–30% | 0.097 | 0.569 | 1.05 | |

| 30–50% | 0.100 | 0.549 | 1.15 |

Results of the

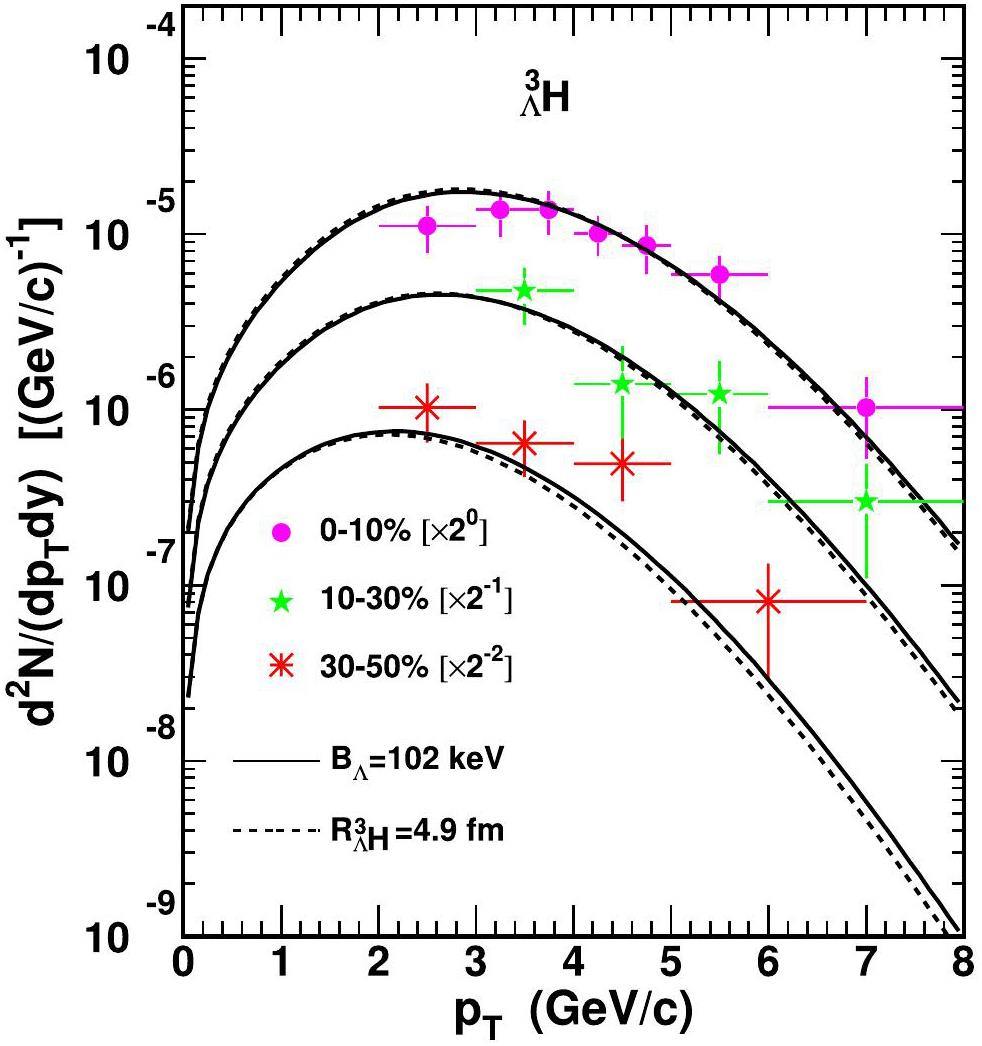

Based on Eq. (27), we compute the production of the

Table 3 presents

| Centrality | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theory-4.9 | Theory-102 | Theory-148 | Theory-410 | Data | Theory-4.9 | Theory-102 | Theory-148 | Theory-410 | ||

| 0–10% | 3.16 | 3.19 | 3.24 | 3.37 | 4.83±0.23±0.57 | 6.09 | 5.96 | 7.75 | 12.7 | |

| 10–30% | 2.90 | 2.94 | 2.99 | 3.11 | 2.62±0.25±0.40 | 2.98 | 2.99 | 4.07 | 7.44 | |

| 30–50% | 2.46 | 2.52 | 2.55 | 2.65 | 1.27±0.10±0.14 | 0.875 | 0.932 | 1.35 | 2.94 | |

Owing to its small binding energy compared to other light (hyper-)nuclei, the

Predictions of Ω-hypernuclei

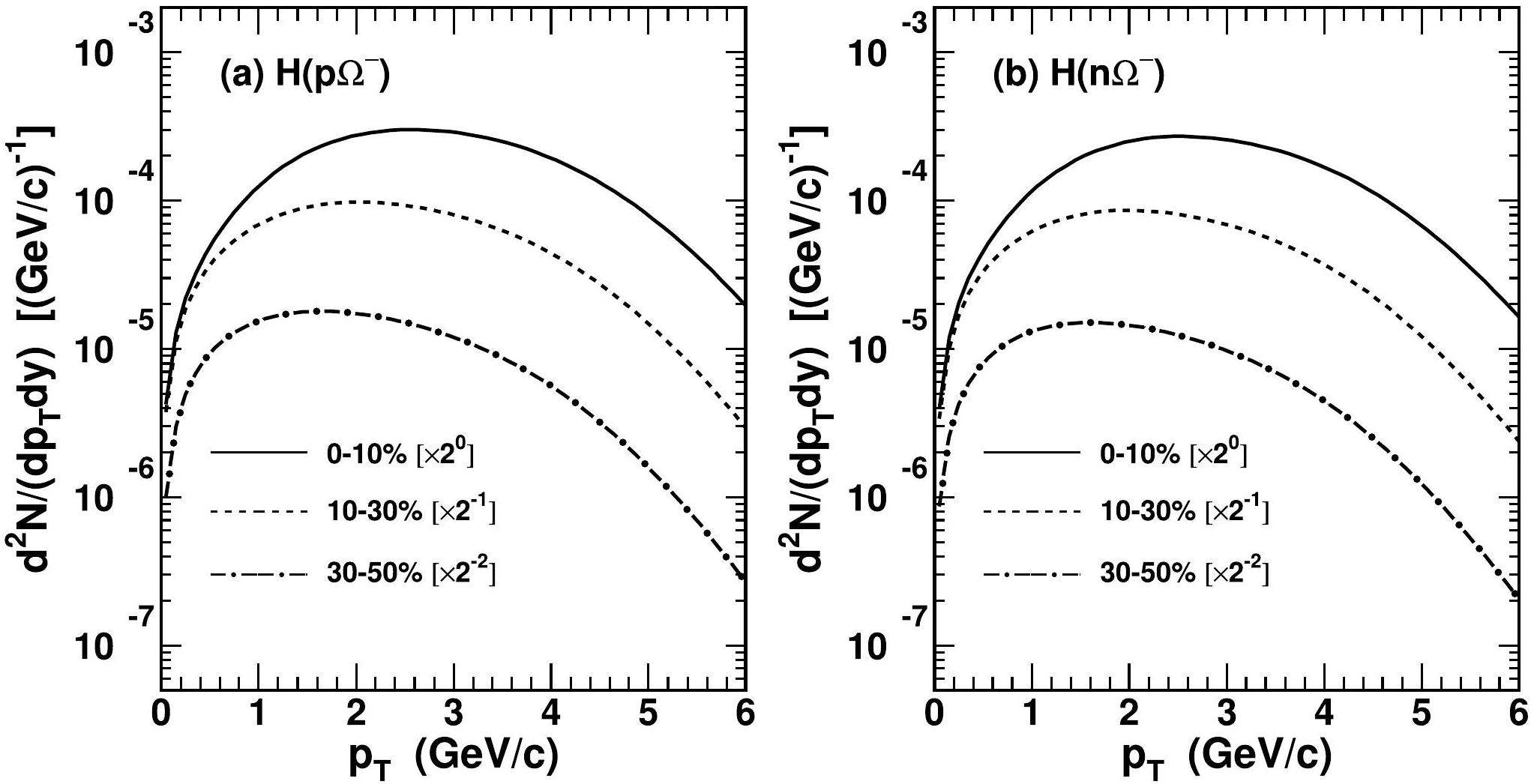

The nucleon-Ω> dibaryon in the S-wave and spin-2 channel is an interesting candidate for the deuteron-like state [89, 90]. The HAL QCD collaboration has reported the root-mean-square radius of H(pΩ-) is about 3.24 fm and that of H(nΩ-) is 3.77 fm [91]. According to Eq. (15), we study their productions, where the spin degeneracy factor

Table 4 presents predictions of the averaged transverse momenta

| Centrality | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| H(pΩ-) | 0–10% | 2.84 | 9.80 |

| 10–30% | 2.44 | 6.27 | |

| 30–50% | 2.18 | 2.16 | |

| H(nΩ-) | 0–10% | 2.81 | 8.75 |

| 10–30% | 2.41 | 5.46 | |

| 30–50% | 2.15 | 1.79 |

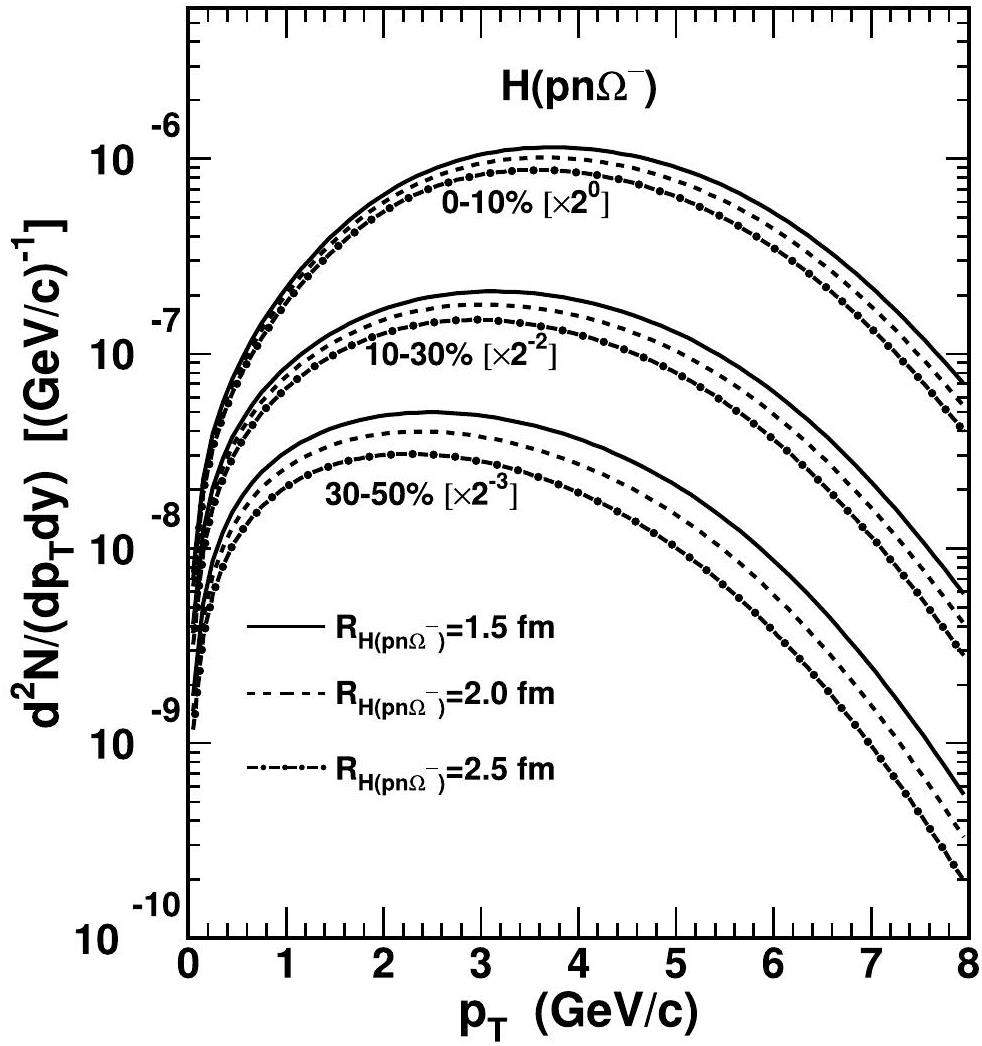

The H(pnΩ-) with maximal spin-

| Centrality | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theory-1.5 | Theory-2.0 | Theory-2.5 | Theory-1.5 | Theory-2.0 | Theory-2.5 | ||

| H(pnΩ-) | 0–10% | 3.94 | 3.88 | 3.82 | 4.77 | 4.17 | 3.56 |

| 10–30% | 3.44 | 3.36 | 3.29 | 3.50 | 2.95 | 2.41 | |

| 30–50% | 2.98 | 2.89 | 2.81 | 1.60 | 1.24 | 0.92 | |

Our predictions in the central collisions for H(pΩ-) and H(nΩ-) are of the same magnitude as those with BLWC and AMPTC models in Ref. [93], and those for H(pnΩ-) are of the same magnitude as reported in Ref. [94]. Our predictions in other centralities provide more detailed references for centrality-dependent measurements of these Ω-hypernuclei in future LHC experiments.

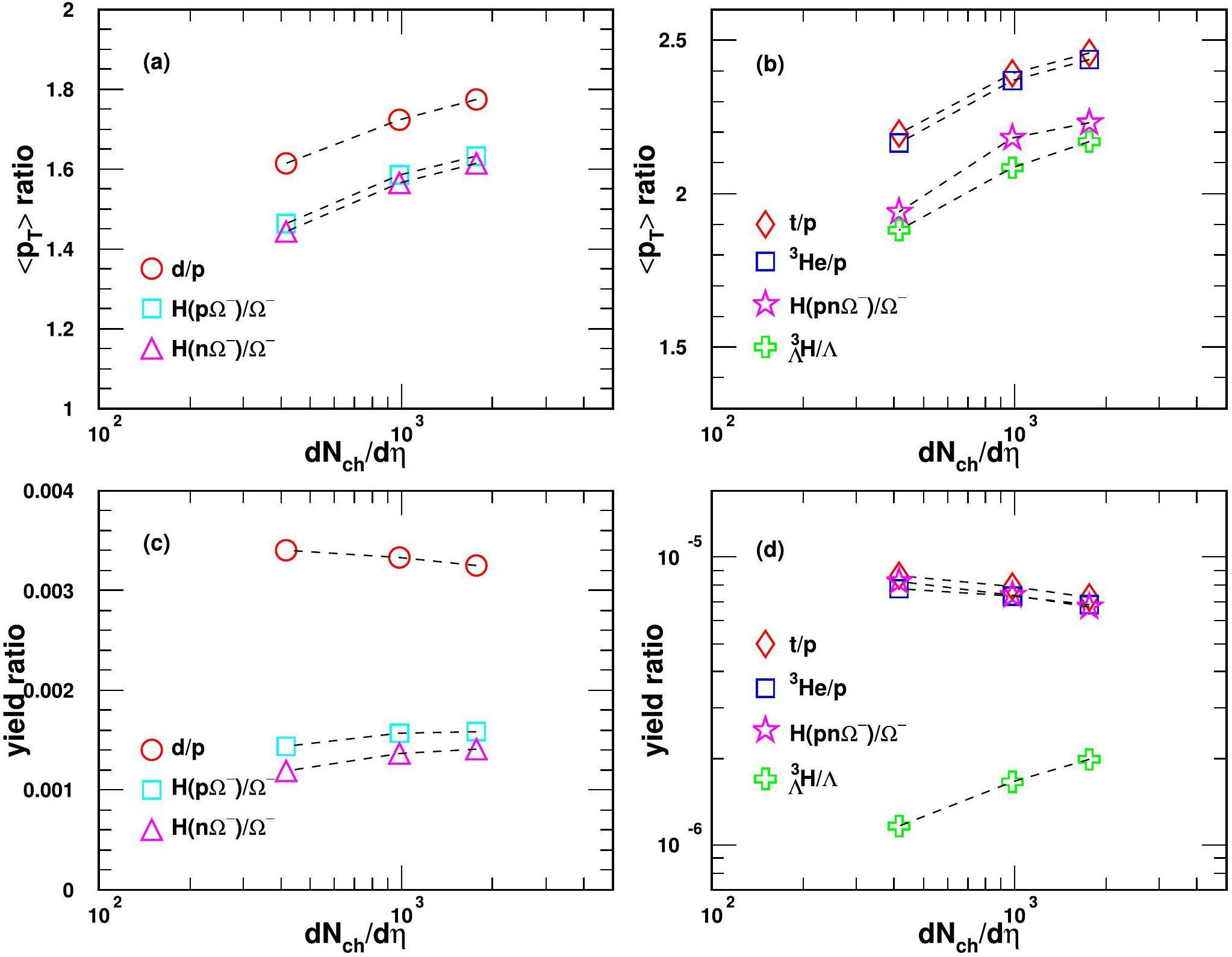

Averaged transverse momentum ratios and yield ratios

Based on the results of light nuclei and hypernuclei presented above, we study two groups of interesting observables as powerful probes for the production correlations of different species of nuclei. One group refers to the

Figure 13(a) and (b) show the

Figure 13(c) and (d) show yield ratios of dibaryon states to baryons and those of tribaryon states to baryons. Open symbols connected with dashed lines to guide the eye represent the theoretical results of the coalescence model. Some of these ratios such as d/p, t/p, 3He/p and H(pnΩ-)/Ω- decrease while the others H(pΩ-)/Ω-,

From Eqs. (15) and (27), similar as Eq. (34), we approximately have

For the limit case of the nuclei with considerably small (negligible) sizes compared to the hadronic system scale, the dNch/dη-dependent behaviors of their yield ratios to baryons are completely determined by the nucleon number density. For the general case, the item

Summary

This study extended the analytical coalescence model previously developed for the productions of light nuclei to include the hyperon coalescence to simultaneously study the production characteristics of d,

The extended coalescence model was applied to Pb+Pb collisions at

Notably, this study presented two groups of novel observables. One referred to the averaged transverse momentum ratios

Antinuclei in Heavy-Ion Collisions

. Phys. Rept. 760, 1-39 (2018). arXiv:1808.09619, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2018.07.002Study of light Lambda and Lambda-Lambda hypernuclei with the stochastic variational method and effective Lambda N potentials

. Prog. Theor. Phys. 103, 929-958 (2000). arXiv:nucl-th/9912065, https://doi.org/10.1143/PTP.103.929Overview of light nuclei production in relativistic heavy-ion collisions

. Nucl. Phys. A 1005,Light nuclei production as a probe of the QCD phase diagram

. Phys. Lett. B 781, 499-504 (2018). arXiv:1801.09382, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2018.04.035Nuclear coalescence from correlation functions

. Phys. Rev. C 99,Loosely-bound objects produced in nuclear collisions at the LHC

. Nucl. Phys. A 987, 144-201 (2019). arXiv:1809.04681, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2019.02.006Production of light nuclei at colliders – coalescence vs. thermal model

. Eur. Phys. J. ST 229, 3559-3583 (2020). arXiv:2004.07029, https://doi.org/10.1140/epjst/e2020-000067-0Kinetic approach of light-nuclei production in intermediate-energy heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 108,’Quantum’ molecular dynamics: A Dynamical microscopic n body approach to investigate fragment formation and the nuclear equation of state in heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rept. 202, 233-360 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-1573(91)90094-3Unveiling the dynamics of little-bang nucleosynthesis

. Nature Commun. 15, 1074 (2024). arXiv:2207.12532, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-45474-xDecoding the phase structure of QCD via particle production at high energy

. Nature 561, 321-330 (2018). arXiv:1710.09425, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0491-6Probing QCD critical fluctuations from light nuclei production in relativistic heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 774, 103-107 (2017). arXiv:1702.07620, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2017.09.056Mapping the Phases of Quantum Chromodynamics with Beam Energy Scan

. Phys. Rept. 853, 1-87 (2020). arXiv:1906.00936, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2020.01.005Light nuclei production in Au+Au collisions at sNN=5−200 GeV from JAM model

. Phys. Lett. B 805,A study of the properties of the QCD phase diagram in high-energy nuclear collisions

. Particles 3, 278-307 (2020). arXiv:2004.00789, https://doi.org/10.3390/particles3020022Strangeness fluctuations and MEMO production at FAIR

. Phys. Lett. B 676, 126-131 (2009). arXiv:0811.4077, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2009.04.062Yield ratio of hypertriton to light nuclei in heavy-ion collisions from sNN=4.9 GeV to 2.76 TeV

. Chin. Phys. C 44,Source size determination in relativistic nucleus-nucleus collisions

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 73, 1219-1222 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.73.1219Production of 4Li and p-3He correlation function in relativistic heavy-ion collisions

. Eur. Phys. J. A 56, 193 (2020). arXiv:2001.11351, https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-020-00198-6Deuteron production mechanism via azimuthal correlation for p-p and p-Pb collisions at LHC energy with the AMPT model

. Eur. Phys. J. A 59, 72 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-023-00980-2Light nuclei and hypernuclei from quantum chromodynamics in the limit of SU(3) flavor symmetry

. Phys. Rev. D 87,Hypernuclei as a laboratory to test hyperon-nucleon interactions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 97 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01248-6Deuteronlike heavy dibaryons from lattice quantum chromodynamics

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123,Probing ΩΩand pΩdibaryons with femtoscopic correlations in relativistic heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Elliptic flow for phi mesons and (anti)deuterons in Au + Au collisions at sNN=200-GeV

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99,Production of deuterium, tritium, and He3 in central Pb + Pb collisions at 20A, 30A, 40A, 80A, and 158A GeV at the CERN Super Proton Synchrotron

. Phys. Rev. C 94,Anti-deuteron and anti-He-3 production in sNN=130-GeV Au+Au collisions

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87,Properties of the QCD matter: review of selected results from the relativistic heavy ion collider beam energy scan (RHIC BES) program

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 214 (2024). arXiv:2407.02935, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01591-2Deuteron yields from heavy-ion collisions at energies available at the CERN Large Hadron Collider: Continuum correlations and in-medium effects

. Phys. Rev. C 106,Energy and centrality dependence of light nuclei production in relativistic heavy-ion collisions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 33, 45 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-022-01028-8Event-by-event antideuteron multiplicity fluctuation in Pb+Pb collisions at sNN=5.02 TeV

. Phys. Lett. B 840,Production of light nuclei in isobaric Ru + Ru and Zr + Zr collisions at sNN=7.7−200 GeV from a multiphase transport model

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Elliptic and triangular flow of (anti)deuterons in Pb-Pb collisions at sNN=5.02 TeV

. Phys. Rev. C 102,Measurement of elliptic flow of light nuclei at sNN=200, 62.4, 39, 27, 19.6, 11.5, and 7.7 GeV at the BNL relativistic heavy ion collider

. Phys. Rev. C 94,Beam-energy dependence of the directed flow of deuterons in Au+Au collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 102,Beam energy dependence of (anti-)deuteron production in Au + Au collisions at the BNL Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider

. Phys. Rev. C 99,Beam energy dependence of triton production and yield ratio (Nt×Np/Nd2) in Au+Au collisions at RHIC

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130,Measurement of the mass difference and the binding energy of the hypertriton and antihypertriton

. Nature Phys. 16, 409-412 (2020). arXiv:1904.10520, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-020-0799-7Measurements of HΛ3 and HΛ4 lifetimes and yields in Au+Au collisions in the high baryon density region

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128,Λ3H and Λ¯3H¯ production in Pb-Pb collisions at sNN=2.76 TeV

. Phys. Lett. B 754, 360-372 (2016). arXiv:1506.08453, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2016.01.040Thermodynamic model for composite particle emission in relativistic heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 38, 640-643 (1977). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.38.640Evidence for a soft nuclear matter equation of state

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 43, 1486-1489 (1979). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.43.1486Production of light nuclei, hypernuclei and their antiparticles in relativistic nuclear collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 697, 203-207 (2011). arXiv:1010.2995, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2011.01.053Antimatter production in proton-proton and heavy-ion collisions at ultrarelativistic energies

. Phys. Rev. C 84,Yields of weakly-bound light nuclei as a probe of the statistical hadronization model

. Phys. Rev. C 100,Production of Tritons, Deuterons, Nucleons, and Mesons by 30-GeV Protons on A-1, Be, and Fe Targets

. Phys. Rev. 129, 854-862 (1963). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.129.854On the coalescence model for high-energy nuclear reactions

. Phys. Lett. B 98, 153-157 (1981). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(81)90976-XDeuteron flow in ultrarelativistic heavy ion reactions

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 2180-2183 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.74.2180Light clusters production as a probe to the nuclear symmetry energy

. Phys. Rev. C 68,Spectra and flow of light nuclei in relativistic heavy ion collisions at energies available at the BNL Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider and at the CERN Large Hadron Collider

. Phys. Rev. C 98,Nuclear clusters as a probe for expansion flow in heavy ion reactions at 10-A/GeV - 15-A/GeV

. Phys. Rev. C 55, 1443-1454 (1997). arXiv:nucl-th/9607003, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.55.1443Production of light nuclei and hypernuclei at High Intensity Accelerator Facility energy region

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 28, 55 (2017). [Erratum: Nucl.Sci.Tech. 28, 89 (2017)]. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-017-0207-xNucleon-number scalings of anisotropic flows and nuclear modification factor for light nuclei in the squeeze-out region

. Eur. Phys. J. A 55, 102 (2019). arXiv:2002.06067, https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2019-12788-0Relativistic coalescence model for high-energy nuclear collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 44, 1636-1654 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.44.1636Coalescence of deuterons in relativistic heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 53, 367-376 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.53.367Multiplicity scaling of light nuclei production in relativistic heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 820,Jet-induced enhancement of deuteron production in pp and p-Pb collisions at the LHC

. Phys. Lett. B 859,Production characteristics of light (anti-)nuclei from (anti-)nucleon coalescence in heavy ion collisions at energies employed at the RHIC beam energy scan

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Different coalescence sources of light nucleus production in Au-Au collisions at GeV*

. Chin. Phys. C 48,Momentum dependence of light nuclei production in p-p, p-Pb, and Pb-Pb collisions at energies available at the CERN Large Hadron Collider

. Phys. Rev. C 103,Production properties of deuterons, tritons, and He3 via an analytical nucleon coalescence method in Pb-Pb collisions at sNN=2.76 TeV

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Light (anti)nuclei production in Pb-Pb collisions at sNN=5.02 TeV

. Phys. Rev. C 107,Measurement of the lifetime and Λseparation energy of Λ3H

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131,Measurement of Λ3H production in Pb–Pb collisions at sNN=5.02 TeV

. Phys. Lett. B 860,Light cluster production in intermediate-energy heavy ion collisions induced by neutron rich nuclei

. Nucl. Phys. A 729, 809-834 (2003). arXiv:nucl-th/0306032, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.09.010Partonic mean-field effects on matter and antimatter elliptic flows

. Nucl. Phys. A 928, 234-246 (2014). arXiv:1211.5511, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2014.05.016Light (anti-)nuclei production and flow in relativistic heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 92,Production of light nuclei in the thermal and coalescence models

. Acta Phys. Polon. B 48, 707 (2017). arXiv:1607.02267, https://doi.org/10.5506/APhysPolB.48.707Pion, kaon, and proton femtoscopy in Pb–Pb collisions at sNN=2.76 TeV modeled in (3+1)D hydrodynamics

. Phys. Rev. C 90,Centrality dependence of pion freeze-out radii in Pb-Pb collisions at sNN=2.76 TeV

. Phys. Rev. C 93,Final state interactions in the production of hydrogen and helium isotopes by relativistic heavy ions on uranium

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 37, 667-670 (1976). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.37.667Effects of collective expansion on light cluster spectra in relativistic heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 419, 19-24 (1998). arXiv:nucl-th/9711011, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0370-2693(97)01455-XCoalescence and flow in ultrarelativistic heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 59, 1585-1602 (1999). arXiv:nucl-th/9809092, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.59.1585Methods for separation of deuterons produced in the medium and in jets in high energy collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 98,Collision centrality and system size dependences of light nuclei production via dynamical coalescence mechanism

. Eur. Phys. J. A 57, 330 (2021). arXiv:2112.03520, https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-021-00639-wTable of experimental nuclear ground state charge radii: An update

. Atom. Data Nucl. Data Tabl. 99, 69-95 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adt.2011.12.006Identical-particle (pion and kaon) femtoscopy in Pb–Pb collisions at sNN=5.02 TeV with Therminator 2 modeled with (3+1)D viscous hydrodynamics

. Eur. Phys. J. A 57, 338 (2021). arXiv:2010.12161, https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-021-00647-wPion interferometry in Au+Au collisions at sNN=200-GeV

. Phys. Rev. C 71,Production of charged pions, kaons, and (anti-)protons in Pb-Pb and inelastic pp collisions at sNN=5.02 TeV

. Phys. Rev. C 101,Thermal phenomenology of hadrons from 200-A/GeV S+S collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 48, 2462-2475 (1993). arXiv:nucl-th/9307020, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.48.2462Production of light nuclei and anti-nuclei in pp and Pb-Pb collisions at energies available at the CERN Large Hadron Collider

. Phys. Rev. C 93,Suppression of light nuclei production in collisions of small systems at the Large Hadron Collider

. Phys. Lett. B 792, 132-137 (2019). arXiv:1812.05175, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2019.03.033Strangeness production in Pb-Pb collisions with ALICE at the LHC

. PoS EPS-HEP 2017, 168 (2017). https://doi.org/10.22323/1.314.0168Production of strange and charm hadrons in Pb+Pb collisions at sNN=5.02 TeV

. Symmetry 15, 400 (2023). arXiv:2302.07546, https://doi.org/10.3390/sym15020400Probing the size and binding energy of the hypertriton in heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 837,Softening of the hypertriton transverse momentum spectrum in heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 855,Hypertriton production in relativistic heavy ion collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 780, 191-195 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2018.03.003On the history of dibaryons and their final observation

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 93, 195 (2017). arXiv:1610.05591, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2016.12.004Probing the internal structures of pΩ and ΩΩ with their production at the Large Hadron Collider

. Phys. Rev. C 110,NΩ dibaryon from lattice QCD near the physical point

. Phys. Lett. B 792, 284-289 (2019). arXiv:1810.03416, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2019.03.050ΩNN and ΩΩN states

. Phys. Rev. C 99,Ω-dibaryon production with hadron interaction potential from the lattice QCD in relativistic heavy-ion collisions

. Phys. Lett. B 811,Production of ΩNN and ΩΩN in ultra-relativistic heavy-ion collisions

. Eur. Phys. J. C 82, 416 (2022). arXiv:2112.02766, https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-022-10336-7The authors declare that they have no competing interests.