Introduction

Nuclear clustering describes the emergence of structures in nuclear physics whose properties resemble those of atomic molecules. Atomic systems exhibit a rich phenomenology of different types of chemical bonds, complex rotational and vibrational excitations, and intricate structural geometries. The occurrence of clusters is well known in macroscopic and microscopic matter, ranging from astrophysics to nuclear physics [1]. Clustering structures emerge from a delicate balance among repulsive short-range forces, Pauli blocking effects, attractive medium-range nuclear forces, and long-range Coulomb repulsions among protons. Protons and neutrons have nearly equal masses, unlike heavy ions surrounded by electrons. Many studies have shown that nucleons tend to form clusters [2-4] such as α clusters.

The α particle is the most likely form of a cluster owing to its high symmetry and binding energy. Evidence for the presence of α clusters comes from nuclear structure calculations and measurements of α decay, such as cluster breaking effects on 3α structures in 12C [4-6]. Recent theoretical studies have revealed the formation of 3α-cluster structures, which are independent of any assumptions regarding the presence of α clusters [7-11]. The experiment 2H(16C, 4He+12Be)2H [12] investigated the inelastic excitation, cluster decay, and linear-chain clustering structure in neutron-rich 16C. The decay paths from the 16C resonances to various states and Q-value spectra of 16C were measured. In addition, a large number of 4α events were recorded in an experiment on 12C(16O, 16O)12C [13]. These studies on α clusters are critical for understanding the synthesis of heavier elements in the universe [14] and other structures of bound nuclei.

The weakly bound nuclei projectiles 6Li, 7Li, and 9Be [15-19] also exhibit α-cluster structures in the ground and resonance-excited states [20, 21]. The α + 5He and 8Be + n cluster structures have been discussed for 8Be [19]. A coincidence measurement experiment was performed using a 14UD tandem accelerator at the Australian National University for 6,7Li +208Pb at beam energies below the fusion barrier energies [22]. The breakup modes α + α, α + t, α + d, and α + p were identified using telescope detectors. For 6Li, the most intense peak in the Q-value spectra corresponded to the breakup of the excited states of the projectile into α and d. For 7Li, the breakup into α + 3H is prominent. The α cluster has been dominant in similar studies on particle–particle coincidence measurements [23]. Recently, the effect of the breakup on the fusion of 6Li, 7Li, and 9Be with heavy nuclei has been discussed [15, 24]. The cross sections for incomplete fusion were found to be similar to those of the missing complete fusion, and incomplete fusion always couples with transfer channels. For example, for 6 Li-induced reaction by breakup-capture, Po and At nuclei can also be formed by the transfer of p, d, or α with the target. Thus, even if it is theoretically assumed (e.g., based on impact parameter considerations) [24], a distinction between transfer and breakup followed by capture is possible. Recently, the competition between transfer and incomplete has been studied [15]. In the 7Li +209Bi system [15], for the main incomplete fusion products, polonium isotopes, only a small fraction can be explained by projectile breakup followed by capture, where the dominant process is triton cluster transfer by combining single and coincidence measurements of light fragments. In the 7Li +93Nb system [18], the triton capture mechanism has also has been observed to be dominant at about 70% when all the inclusive α-particles have been accounted for.

An exploratory experiment with radioactive beams was performed at REX-ISOLDE to test the potential of cluster-transfer reactions at the Coulomb barrier and further explore the structure of exotic neutron-rich nuclei [25, 26]. The reactions 7Li(98Rb, αxn) and 7Li(98Rb, txn) were studied using particle-γ coincidence measurements. The majority of the detected α and 3H particles corresponded to 3H and α transfers, whereas the percentage of 7Li elastic breakup was determined to be less than 20%. The reaction mechanism has been qualitatively discussed within a distorted-wave Born approximation (DWBA) framework. Cluster-transfer reactions can be fully described as direct processes. In the early studies of the reactions 16O (6Li, 3He) 19F and 16O (6Li, 3H) 19Ne at a bombarding energy of 24 MeV, the energy spectra and angular distributions scattered 6Li ions and other heavier reaction products were detected at many forward angles [27]. The results indicated that the ground-state bands of 19F and 19Ne are populated with a 20-fold higher intensity than other excited state bands, and the high-spin states cannot be convincing evidence for a predominantly direct reaction process. Additionally, DWBA analysis was successfully employed to establish the transfer of a three-nucleon cluster.

As mentioned earlier, the transfer reactions of 3He and 3H clusters on light-mass targets have been previously confirmed. However, studies on medium-mass targets are limited. In this study, cluster transfer was performed in an experiment of 6Li+89Y. Direct and sequential transfer reactions are discussed using cyclic redundancy check (CRC) calculations. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Sect. 2 presents the experimental details. Experimental results and discussion are presented in Sect. 3. The theoretical calculations are discussed in Sect. 4. Finally, conclusions are summarized in Sect. 5.

Experimental details

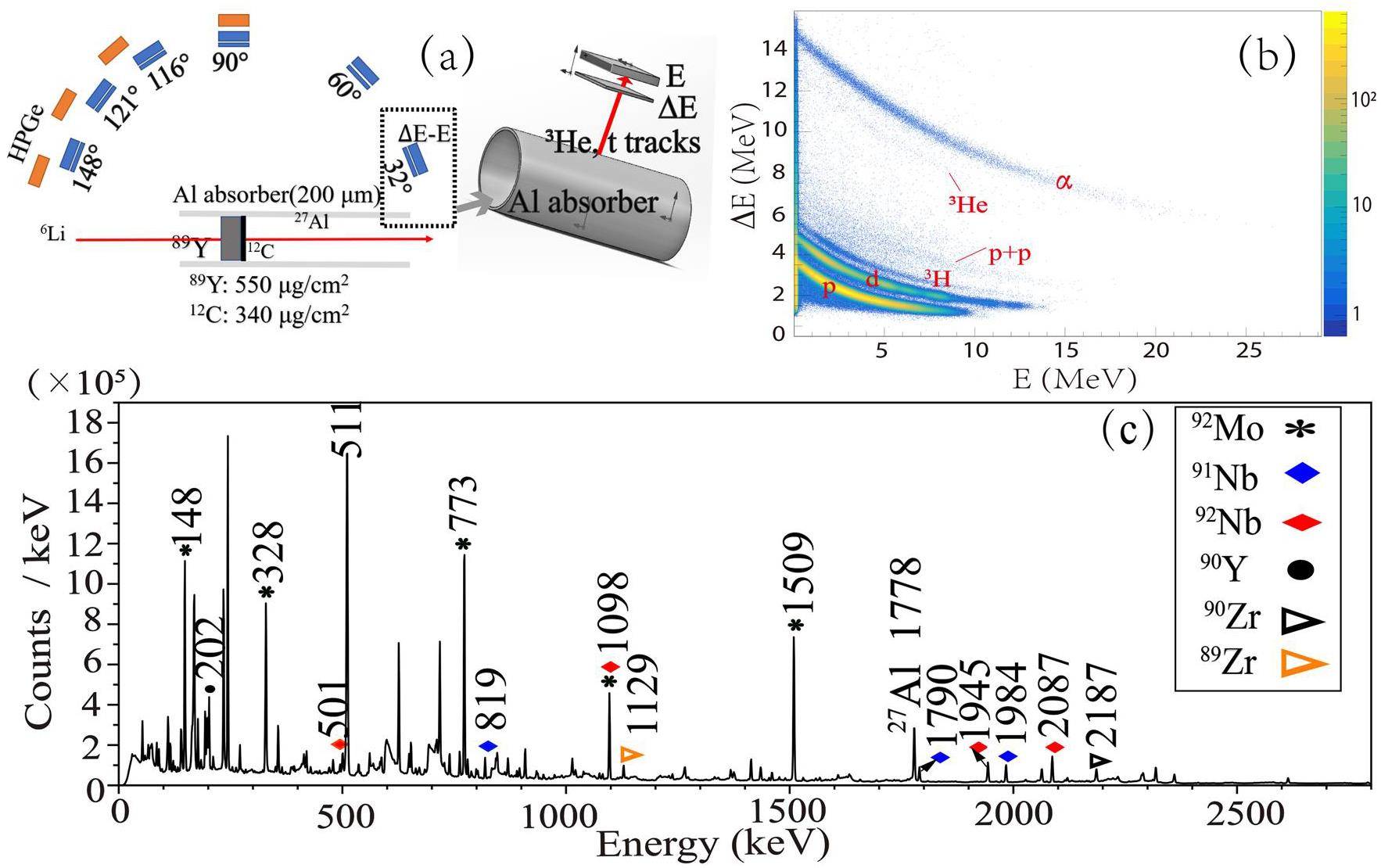

The 6Li+89Y experiment was performed at the Laboratori Nazionali di Legnaro, INFN, Italy. A 6Li3+ beam with an average intensity of 1.0 enA was accelerated to 34 MeV using the XTU Tandem-ALPI accelerator. The 89Y target, with a thickness of 550 μg/cm2, was backed on a 340 μg/cm2-thick 12C foil to stop all the target-like reaction products. The GALILEO array, which consisted of 25 Compton-suppressed Ge detectors, was employed to collect γ-rays. The energy resolution was about 2.8 keV at 1332 keV. A 4π Si-ball detector array named EUCLIDES was used to measure light-charged particles. The EUCLIDES array comprised 40 ΔE-E telescopes, where the thicknesses of ΔE and E detectors were 130 μm and 10000 μm, respectively. Detailed information on the GALILEO and EUCLIDES arrays are available in Refs. [28, 29]. A schematic of the experimental setup is shown in Fig. 1(a). Because Si detectors are sensitive to radiation damage, an 200 μm-thick Al absorber was inserted between the target and EUCLIDES array to stop the elastically scattered 6Li. The Al absorber shielded all the Si detectors, except for those located at angles larger than 148. In this paper, angles larger than 148 are called uncovered angles, and the others are called covered angles. A two-dimensional correlation plot of ΔE and E detectors for the light-charged particle identification of 6Li+89Y at 34 MeV is shown in Fig. 1(b). The proton (p), deuteron (d), tritium (3H), and helium isotope particles (3He and α) are clearly identified. At the covered angles, all light-charged particles were to pass through the Al absorber and ΔE detectors, whereas the particles could only pass through the ΔE detectors at the uncovered angles. The minimum energies of the particles passing through the ΔE detectors and Al absorber are listed in Table 1. Figure 1(c) shows the γ-rays of the main residual nuclei in a single γ spectrum detected using the GALILEO array. An analysis of the relevant γ spectrum by gating different particles (particle-γ-ray coincidence) is a viable approach for investigating their origins, as various reaction channels can generate distinct particles and residual nuclei.

| Particles | E (MeV) | Al and ΔE (MeV) |

|---|---|---|

| 3H | 5.710 | 10.56 |

| 3He | 13.29 | 23.87 |

| α | 14.88 | 26.89 |

Results and discussion

In the 6Li+89Y system, 3H and 3He evaporations are not always considered in the complete fusion reaction channel [30-32], and the breakup threshold of 6Li to 3He and 3H is as high as 15.8 MeV. The energies of the outcoming 3H and 3He fragments were too low to pass through the Al absorber and ΔE detectors. Therefore, 3He and 3H were assumed to originate from the transfer reaction.

3He-γ coincidence

| 92Nb of 3He-transfer | 92Zr of 3H-transfer | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| γ-rays (keV) | Relative intensity | γ-rays (keV) | Relative intensity |

| 123.1 | 26.91±6.732 | 934.5 | 100±26.47 |

| 148.0 | 100.0±11.64 | 561.0 | 56.6±18.50 |

| 150.0 | 100.0±11.64 | 990.0 | 33.2±15.76 |

| 194.0 | 86.80±21.72 | 894.0 | 34.8±15.26 |

| 357.5 | 86.53±4.14 | 1462.0 | 23.5±17.65 |

| 501.0 | 98.33±13.67 | – | – |

| 711.0 | 89.37±19.38 | – | – |

| 2087.5 | 61.91±17.35 | – | – |

| 2287.5 | 136.48±32.39 | – | – |

3H-γ coincidence

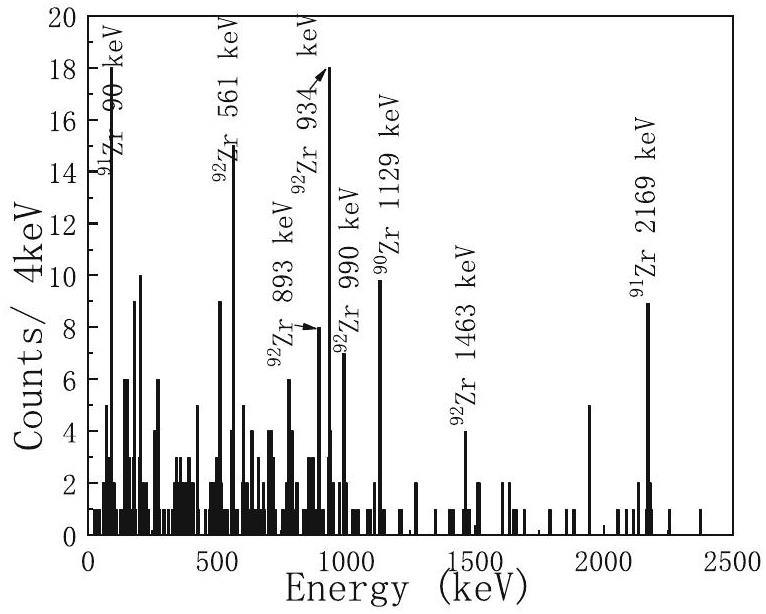

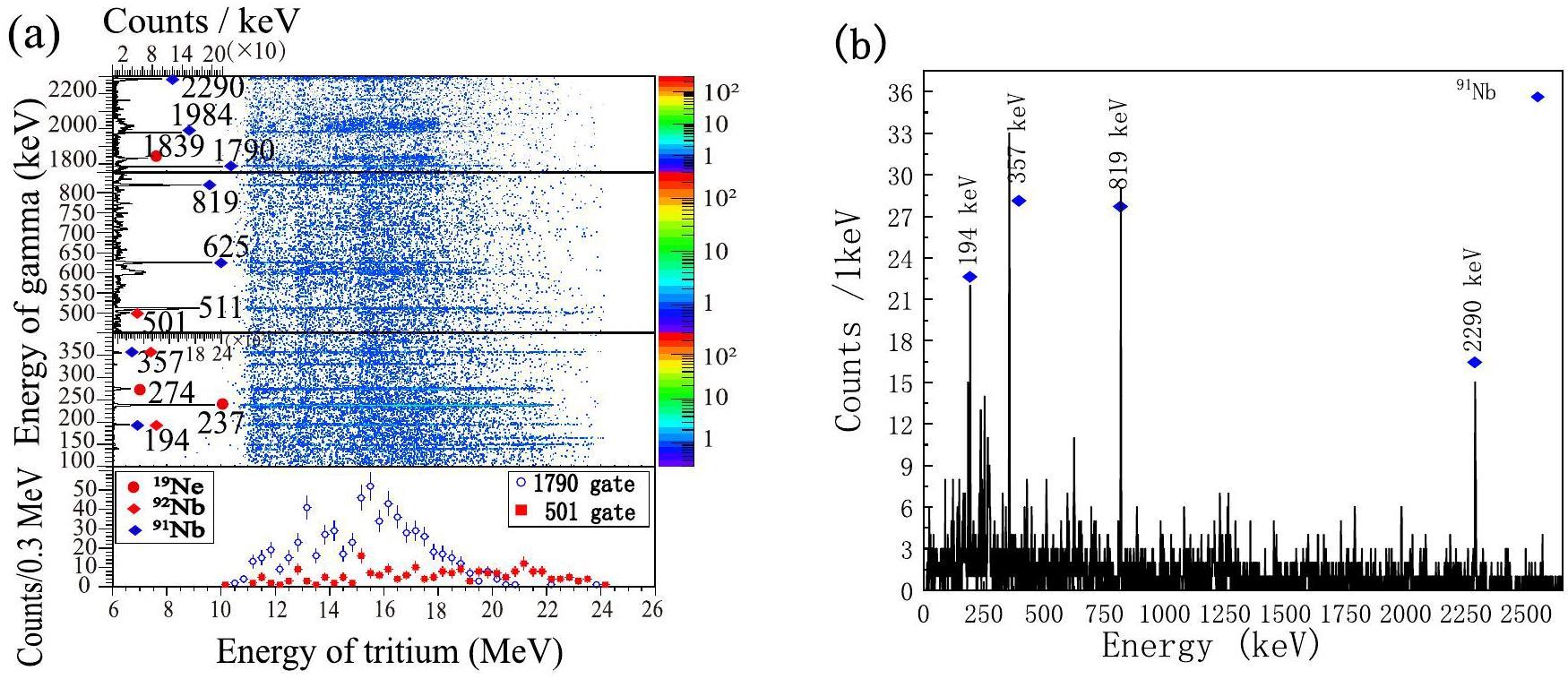

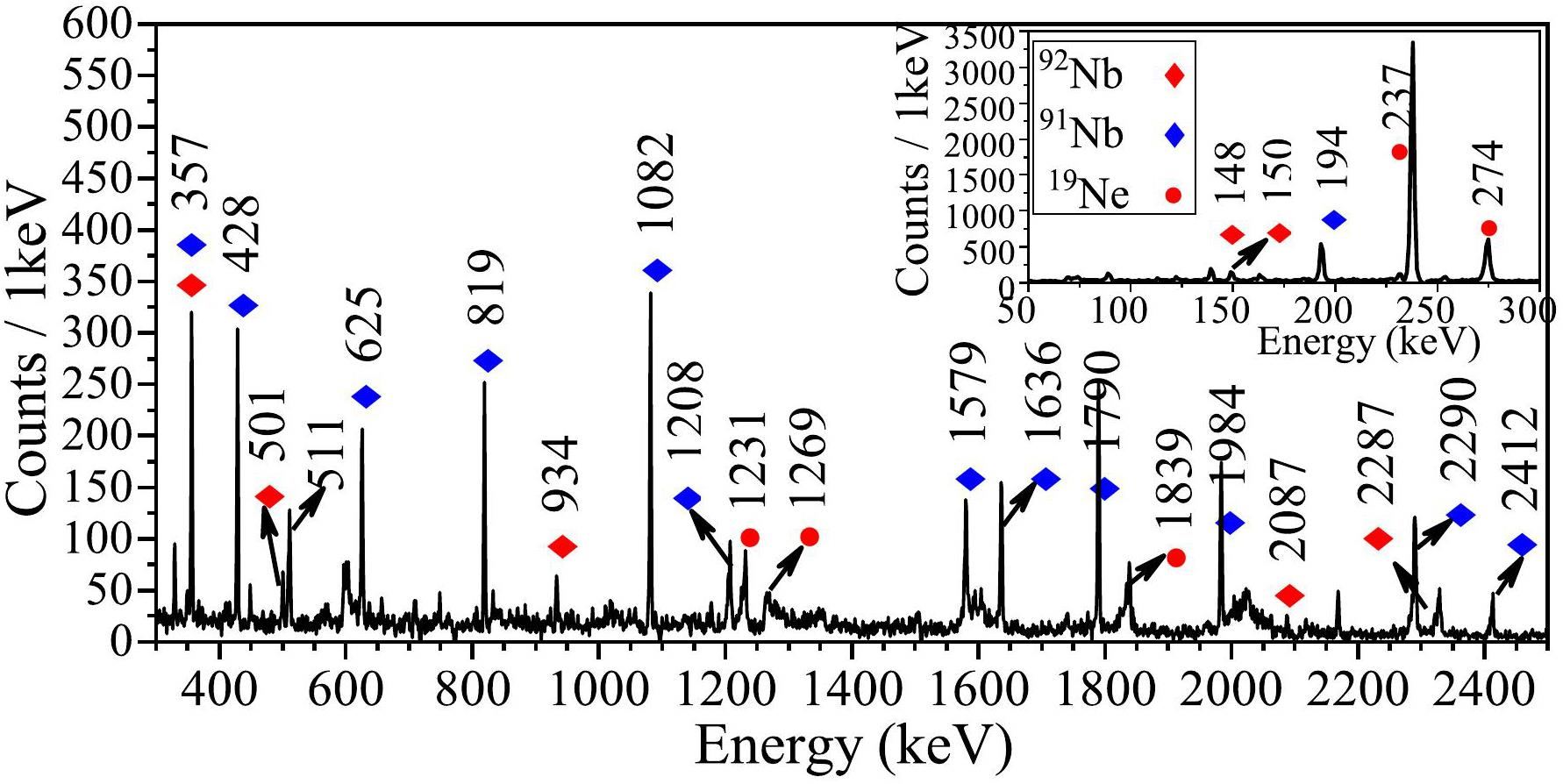

In the 3H coincident γ spectrum in Fig. 3a and Fig. 4, 91Nb and 92Nb are the primary residuals. In the inset window, the strong γ-rays 237 keV and 274 keV were the characteristic γ-rays of 19Ne. The counts are significant but disappear at the uncovered angles in Fig. 3(b). 19Ne from the 3He transfer, as shown in Eq. (2) has already been studied [27]. 3H, which coincides with these γ-rays, indicates a stronger association with the transfer reaction owing to its forward trend. However, 16O may originate from the support frame of the target or the backing foil. Therefore, the yield of the residues 19Ne could not be obtained in this experiment.

To further analyze the main products, 92Nb and 91Nb, Fig. 3(a) shows the correlations between 3H energies and different γ-rays. The projections of the energy of the γ-rays are shown on the left side, and the counts of the γ-rays of 91Nb are larger when 3H particles are gated. In the bottom window, the 501-keV (92Nb) γ-ray-gated 3H spectrum (red dots) also shows a higher energy distribution than that from 1790-keV γrays in 91Nb (blue dots). In terms of energy conservation, when the energy of the gated 3H increased, the excitation energy of 92Nb from 3He transfer reaction decreased. Thus, fewer neutrons evaporated. The normalized intensities of certain significant γ-rays are presented in the second column of Table 2, assuming a standard intensity of 100 for the γ-rays with energy of 150 keV. According to Eq. (3), referring to the 3He-γ coincidence analysis results, 91Nb and 92Nb originated from 3He transfer process, similar to the reaction in Ref. [27]. In the kinematics calculations, the total energy of 3H was approximately 25 MeV, as shown in Eq. (3) showing that 3H particles can pass through the Al absorber and be detected. 91Nb, which has a neutron magic number of 50, is the one-neutron evaporation product of 92Nb.

Theoretical calculations for 3He and 3H

Theoretical calculations for 89Y(6Li, 3He)92Zr and 89Y(6Li, 3H)92Nb reactions at Elab= 34 MeV were performed using exact finite-range CRC calculations with FRESCO code [33]. The São Paulo double-folding potential was used as the optical potential for both real and imaginary parts [34]. To consider channels that are not explicitly included in the entrance partition, such as breakups, we set the strength factor of the imaginary part to 0.60 [35]. The strength factor of the imaginary part was set to 0.78 for the outgoing partitions, as no couplings were considered [36]. Woods–Saxon potentials were used to build the single-particle and cluster wave functions. The diffusivity and radii were fixed at 0.65 fm and 1.25 fm, respectively, and the depth was varied to reproduce the experimental binding energy.

These transfer reactions occur in two ways: (i) Directly, where nucleons are transferred together simultaneously as a cluster, i.e., considering the cluster as a structure-less particle. (ii) Sequentially, in which the nucleons are transferred in two or more steps, passing through intermediate partitions. Therefore, both direct and sequential processes were considered in the transfer calculations. In contrast, cross sections were obtained for two types of transfer reactions considering two different schemes: (a) SA = 1.0, which implies that the spectroscopic amplitude was set to 1.0, and (b) Microscopic spectroscopic amplitudes calculated using the shell model [37].

Many theoretical studies have attempted to derive the cluster spectroscopic amplitudes, particularly for alpha particles (e.g., Refs. [38-49]). Most of these studies have used different theoretical approaches, including shell, dynamic molecular, and pure cluster models to determine the contribution of the alpha cluster to the wave function of the bound or resonant states. Others were concerned with cluster preformation for alpha emissions. In some studies, the authors claimed that the shell model failed to derive the spectroscopic properties of the states.

To verify the validity of the shell model for calculating the spectroscopic amplitudes, we compared its results with those obtained in Ref. [50] using the semi-microscopic algebraic cluster model for the

| Outgoing channel | Integrated cross section (mb) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3He JπE (keV) | 92Zr | Direct (SA = 1.0) | Direct (microscopic calculations) | Sequential (SA = 1.0) | Sequential (microscopic calculations) |

| 1/2- 0.0 | 0+ 0.0 | 0.9121 | 2.302×10-4 | 6.623×10-3 | 1.168×10-7 |

| 2+ 934.5 | 4.948 | 2.381×10-5 | 1.726×10-2 | 6.756×10-7 | |

| 4+ 1495.5 | 8.556 | 3.884×10-5 | 5.461×10-2 | 3.282×10-7 | |

| 5- 2486.0 | 13.28 | 2.642×10-5 | 9.843×10-3 | 3.321×10-9 | |

| 6+ 2957.4 | 11.78 | 3.543×10-6 | 4.238×10-2 | 7.295×10-7 | |

| 7- 3379.0 | 9.985 | 1.170×10-5 | 1.143×10-2 | 8.325×10-6 | |

Calculation results of direct transfer reactions

One of the most common methods for two-particle transfer calculations is to set the spectroscopic amplitude equal to 1.0 (SA = 1.0) [51]. In this case, the nucleon spins are considered antiparallel, and n=1 and l=0 are assumed as the internal state of the cluster quantum number. In our case, where the cluster is composed of three nucleons, the spin of the transferred cluster is assumed to be equal to the spin of the free nucleus in its ground state. The relevant parameters for defining the cluster wave function are the principal quantum number N and the orbital angular momentum L relative to the core. N and L can be determined from the conservation of the total number of quanta in the transformation of the wavefunction of three independent nucleons into a cluster [52].

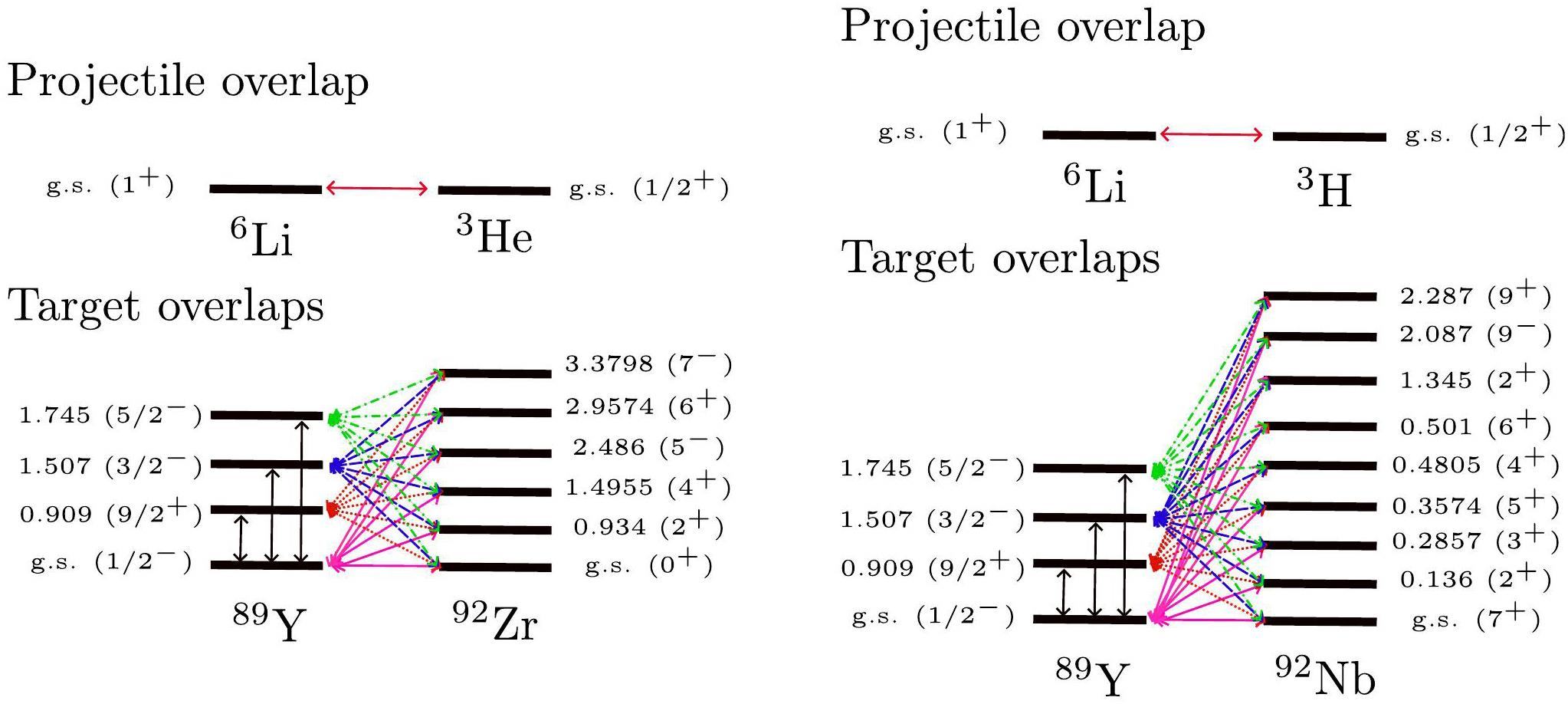

The level scheme of the nuclei and couplings adopted in the direct transfer calculations is shown in Fig. 5 for both transfer reactions. Here, we are interested in the order of magnitude rather than in a quantitative description of the reaction process. Because the selection rules for the transfer of particles are relevant in these processes, for each case, the states are characterized by the spin, parity, and energy values considered in the calculations according to the total angular momentum J, orbital momentum L, and spin of the transferred cluster. The theoretical results of the direct 3H and 3He transfers for SA = 1.0, are shown in Tabs. 3 and 4, respectively. The transfer cross sections are of the order of mb. However, these results are overestimated because of unrealistic spectroscopic amplitudes.

| Outgoing channel | Integrated cross section (mb) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3H JπE (keV) | 92Nb | Direct (SA = 1.0) | Direct (microscopic calculations) | Sequential (SA = 1.0) | Sequential (microscopic calculations) |

| 1/2- 0.0 | 7+ 0.0 | 5.611 | 4.397×10-6 | 4.580×10-4 | 1.284×10-5 |

| 2+ 136.0 | 2.347 | 1.415×10-6 | 3.523×10-3 | 1.850×10-5 | |

| 3+ 285.7 | 2.670 | 1.081×10-6 | 3.542×10-3 | 4.497×10-6 | |

| 5+ 357.4 | 7.913 | 5.189×10-6 | 4.979×10-3 | 9.804×10-6 | |

| 4+ 480.5 | 7.495 | 3.835×10-6 | 5.640×10-3 | 7.630×10-6 | |

| 6+ 501.0 | 8.059 | 4.510×10-6 | 4.053×10-3 | 4.276×10-6 | |

| 2+ 1345.5 | 5.253 | 3.968×10-8 | 4.149×10-3 | 2.159×10-7 | |

| 9- 2087.5 | 7.229 | 5.352×10-7 | – | – | |

| 9+ 2287.2 | 4.278 | 7.684×10-8 | – | – | |

The next step was to calculate realistic spectroscopic amplitudes for the projectile and target overlap. Microscopic spectroscopic amplitudes calculated from the shell model were necessary to obtain these spectroscopic amplitudes. These were obtained by performing shell model calculations using the NuShellX code [53]. For the target overlaps, a closed 78Ni core and valence protons in the 1f5/2, 2p3/2, 2p1/2, and 1g9/2 orbitals and valence neutrons in the 1g7/2, 2d5/2, 2d3/2, 3s1/2, and 1h11/2 orbitals were considered. Because of computational limitations, certain restrictions were imposed on the valence proton orbitals. Specifically, within the 1g9/2 orbit, we determined that a maximum of six protons could occupy this orbital. The n-n, p-p, and n-p effective phenomenological interactions were based on jj45apn interaction [54], in which the two-body matrix elements were determined considering the charge-dependent Bonn potential (CD-Bonn) [55, 56]. In this interaction, the single particle energies for proton model space were set to

We observed that the integrated transfer cross sections of both reactions decreased when microscopic spectroscopic amplitudes were used. These results were expected because this cluster configuration should have a low probability in these nuclei. The calculated spectroscopic amplitudes are presented in the Appendixes.

Calculation of sequential transfer reactions

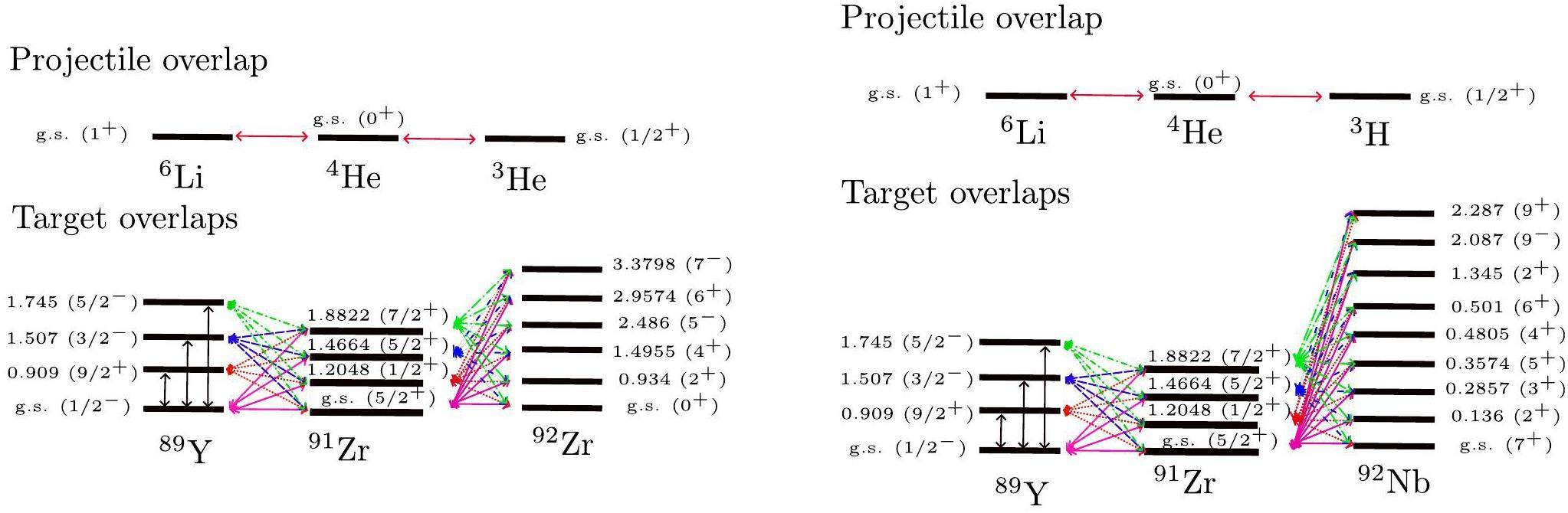

The calculations also considered sequential processes in which the three nucleons are transferred. We performed calculations for multi-step transfer reactions passing through the intermediate partitions. We focused on two two-step sequential transfers, 2H + n and 2H + p because these are the only reactions that pass through partitions with stable projectile-like nuclei. The others occur through unstable nuclei (5Li or 5He), which is unlikely because they are two-step processes and the unbound particles decay easily. Nevertheless, some tests that included ground states as bounds were also performed. The cross sections were observed to be very small. The cross sections for these transfer reactions were three orders of magnitude lower than those for direct cluster transfer. Therefore, we do not provide details here and consider only two two-step sequential transfer reactions passing through the same intermediate partition (4He + 91Zr). Three excited and ground states were considered for 91Zr, as shown in Appendix C. These reactions involve only stable nuclei or nuclei with long half-lives. In these two transfer reactions, either a proton is transferred after a 2H-like (a correlated n-p) for the 3He sequential transfer reaction, or a neutron is transferred after a 2H-like (a correlated n-p) for the 3H sequential transfer reaction. Similarly, the São Paulo potential (SPP) was used for the real and imaginary parts of the optical potential. As no couplings were considered in the intermediate partitions, the strength factor of the imaginary part was set to 0.78, as in the outgoing partitions. The Woods–Saxon potential was used to build single-particle wave functions, in which the parameters were varied to reproduce the corresponding experimental binding energies. The 91Zr states used in the theoretical calculations were obtained according to Brink’s criteria for optimal excitation energies [60]. The spectroscopic amplitude results are presented in the Appendix C.

The level scheme and the couplings adopted in the sequential transfer calculations are shown in Fig. 6 for both the reactions. Theoretical calculations were performed considering SA = 1.0 for the 2H transfer (in the first step), and spectroscopic amplitudes were set equal to 1.0 for proton and neutron transfer (in the second step). The results are summarized in Tables 3 and 4. Comparing the results shown in Tables 3 and 4, we observed that the cross sections of the direct process were three orders of magnitude larger than those of the sequential process; therefore, the sequential process is negligible compared to the direct process.

The microscopic spectroscopic amplitudes calculated from the shell model are shown in a sequential process. The same interaction and model space were used to evaluate the microscopic spectroscopic amplitudes that were used in the direct reaction calculations above. In the first step, a deuterium-like particle was transferred, followed by a proton or neutron when microscopic spectroscopic amplitudes were used. In this case, the independent coordinate model was used [51] in which the coordinates of the nucleons are transformed to the relative coordinates between the neutron and proton and that of its center of mass relative to the α core. The spectroscopic amplitudes were calculated for the correlated n-p, including the projectile-like and target-like overlaps. In the second step, a neutron was transferred to the 3 H-stripping reaction. Similarly, a proton was transferred in the second step of 3He transfer.

The theoretical results for the sequential transfer reactions with microscopic spectroscopic amplitudes are presented in Tables 3 and 4. The integrated transfer cross sections of the 9- and 9+ states for 92Nb are missing. This is because the selection rules prohibit these transitions during the sequential transfer process in the used model space. Comparing the results in Table 3, we can conclude that the sequential process is negligible for most of the studied states when microscopic spectroscopic amplitudes are applied to the 3H transfer reaction. Conversely, sequential transfer is relevant to the 3He transfer reaction when compared with the direct transfer process, as they have cross sections of the same order of magnitude.

These results can be explained by examining the structures of the residual nuclei. The transfer cross section is proportional to the spectroscopic amplitudes of two overlaps: one for the projectile and the second for the target. The projectile overlaps are similar because the transferred neutrons or protons in the second step lie on the same shell. The protons and neutrons transferred to the target-like nucleus (91Zr) will occupy different orbitals in the residual nuclei. Therefore, the spectroscopic amplitudes of the second step are very different, and consequently, the two-step transfer is very different in the 2H + n and 2H + p transfers.

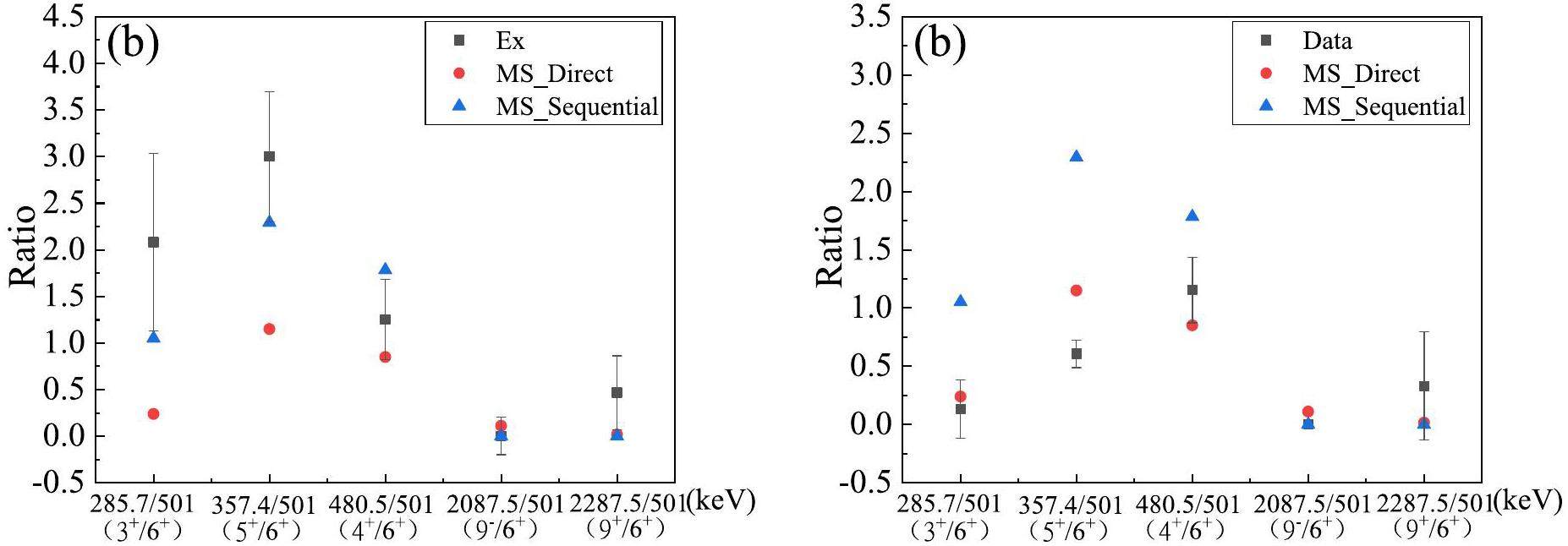

Comparison with experimental data

The interplay between direct and sequential transfer reactions is discussed in Ref. [61] for deuteron transfer. The relevance of both processes in our experimental data is also discussed. The intensities of some γ-rays are listed in Table 2. Therefore, the relative ratios of some states that are directly populated can be defined to compare the theoretical results in the framework of microscopic spectroscopic amplitude calculations with the experimental data. The 6+ state of 92Nb was used as a benchmark, whereas the 2+ state was used for 92Zr. The selected states were guided by the fact that they decayed only to the ground state. The results are presented in Fig. 7. Fig. 7(a) shows the ratio of the cross sections of the different excited states of 92Zr to that of the first excited state (2+) observed experimentally. The experimental and theoretical ratios for 6+ and 7- states were in good agreement for direct transfer. The theoretical and experimental ratios for the other two states were also of the same order of magnitude for the direct 3H transfer reaction. The sequential transfer cross sections were in good agreement with the experimental ratios for the three lower energy states. As mentioned previously, by comparing the results presented in Table 4, the sequential and direct processes were of the same order of magnitude in the 3He transfer reactions. Therefore, both processes are relevant when microscopic spectroscopic amplitudes are used. The ratios of most states are consistent with the theoretical calculations, as shown in Fig. 7(b). For 92Nb, the errors of states 285.7 keV(3+) and 357.4 keV(5+) were larger, because the γ-rays 357.4 keV and 194.8 keV also emanate from 91Nb.

Conclusion

In this study, the transfer reactions of 3He and 3H by charged particles and γ-ray coincidence. From the 3He-γ coincident measurement, one 3H stripping reaction contributed to the formation of Zr isotopes and provided evidence for the 3He transfer reaction by 3H–γ coincident measurements. In the coincident results of 3H-γ, two types of transfer reaction products were obtained: 19Ne from the reaction with 16O and 92Nb from the reaction with the target nucleus 89Y. CRC calculations and comparison of the relative cross sections of different excited states observed in the experiment confirmed the existence of 3He and 3H clusters in 6Li. However, more experiments are required because of the limitations of the experimental statistics.

Experimental evidence for α production following neutron transfer in the 13C+93Nb system

. Phys. Rev. C 105,α-Clustering in atomic nuclei from first principles with statistical learning and the Hoyle state character

. Nature Commun. 13, 2234 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29582-0Cluster-shell competition in light nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 70,Alpha Cluster Condensation in 12C and 16O

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87,Alpha-clustering in nuclei

. Nature 257, 446-447 (1975). https://doi.org/10.1038/257446a0αclustering in nuclear astrophysics and topology

. Aip Conf. Proc. 11,“Di-Neutron” configuration of 6He

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 4996-4999 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1103/physrevlett.82.4996The structure of ground and excited states of 12C

. Prog. Theor. Exp. Phys. 117, 655-680 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1143/ptp.117.655Nuclear structure of light nuclei in an extended fmd approach

., https://www.osti.gov/etdeweb/biblio/20479778(072004)Structure of the hoyle state in 12C

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98,Nuclear clusters and nuclear molecules

. Physics Reports 432, 43-113 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2006.07.001Positive-parity linear-chain molecular band in 16C

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124,New evidence of the hoyle-like structure in 16O

. Sci. Bull. 68, 1119-1126 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scib.2023.04.031Synthesis of the elements in stars

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 29, 547-650 (1957). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.29.547Origins of incomplete fusion products and the suppression of complete fusion in reactions of 7Li

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122,Puzzle of complete fusion suppression in weakly bound nuclei: A trojan horse effect?

Phys. Rev. Lett. 122,One-neutron stripping processes to excited states of 90Y* in the 89Y(Li, Li)90Y* reaction

. Phys. Rev. C 223, 01068 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/201922301068Investigation of large αproduction in reactions involving weakly bound 7Li

. Phys. Rev. C 96,Elastic scattering and αproduction in the 9Be+89Y system

. Phys. Rev. C 89,Energy levels of light nuclei A=5, 6, 7

. Nucl. Phys. A. 708, 3-163 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0375-9474(02)00597-3Energy levels of light nuclei A=8, 9, 10

. Nucl. Phys. A. 745, 155-362 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2004.09.059Insights into the mechanisms and time-scales of breakup of 6,7Li

. Phys. Lett. B 695, 105-109 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2010.11.007Relative probabilities of breakup channels in reactions of 6,7Li with 209Bi at energies around and above the coulomb barrier*

. Chinese Phys. C. 45,Effect of breakup on the fusion of 6Li, 7Li, and 9Be with heavy nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 70,Cluster-transfer reactions with radioactive beams: A spectroscopic tool for neutron-rich nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 92,Systematics and mechanisms of αproduction with weakly and strongly bound projectiles

. The Eur. Phys. J. A. 59, 88 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/s10050-023-01011-wStudy of the reactions 16O (6Li, 3He) 19F and 16O(6Li, t)19Ne at E(6Li)=24 MeV

. Phys. Rev. C 5, 682-690 (1972). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.5.682The 4πhighly-efficient light-charged-particle detector euclides, installed at the galileo array for in-beam γ-ray spectroscopy

. Eur. Phys. J. A 55, 12714 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2019-12714-6The galileo γ-ray array at the legnaro national laboratories

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A. 1015,Statistical model calculations in heavy ion reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 21, 230-236 (1980). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.21.230Neutron emission in 19F-induced reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 97,Ingoing-wave boundary condition versus optical model transmission coefficients: A systematic comparison with particle emission data

. Phys. Rev. C 51, 1873-1881 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.51.1873Toward a global description of the nucleus-nucleus interaction

. Phys. Rev. C 66,An imaginary potential with universal normalization for dissipative processes in heavy-ion reactions

. Phys. Lett. B 670, 330-335 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2008.10.066Comparison between heavy-ion reaction and fusion processes for hundreds of systems

. Nucl. Phys. A. 764, 135-148 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2005.09.001Microscopic cluster model for the description of new experimental results on the 13C(18O, 16O)15C two-neutron transfer at 84 MeV incident energy

. Phys. Rev. C 95,Recent developments in radioactive charged-particle emissions and related phenomena

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 105, 214-251 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppnp.2018.11.003Imprints of αclustering in the density profiles of 12C and 16O

. Phys. Rev. C. 107,Many-body description of nuclear structure and reactions

. Phys. Today 21, 103-105 (1968). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3034946Structure of the excited states in 12C

. Prog. Theor. Phys. 57, 1262-1276 (1977). https://doi.org/10.1143/PTP.57.1262Role of tensor interaction as salvation of cluster structure in 44Ti

. Phys. Rev. C. 105,Transition densities between the 01+, 21+, 41+, 02+, 22+, 11- and 31- states in 12C derived from the three-alpha resonating-group wave functions

. Nucl. Phys. A. 351, 456-480 (1981). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(81)90182-212C (α, γ)16O E2 cross section in a microscopic four-alpha model

. Phys. Rev. C. 47, 210 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1013/PhysRevC.47.210Microscopic α-cluster model for 12C and 16O based on antisymmetrized molecular dynamics: Consistent understanding of the binding energies of 12C and 16O

. Prog. Theor. Phys. 94, 1019-1038 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1143/PTP.94.1019Alpha cluster condensation in 12C and 16O

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87,α-clustering in atomic nuclei from first principles with statistical learning and the hoyle state character

. Nat. Commun. 13, 2234 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-29582-0The structure of ground and excited states of 12C

. Prog. Theor. Phys. 117, 655-680 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1143/PTP.117.655Structure of the hoyle state in 12C

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98,Analysis of the alpha-transfer reaction in the 12C+16O system using the semi-microscopic algebraic cluster model

. The Eur. Phys. J. A. 55, 94 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2019-12773-7Transformation brackets for harmonic oscillator functions

. Nucl. Phys. 13, 104-116 (1959). https://doi.org/10.1016/0029-5582(59)90143-9Magnetic moments of the 21+ states around 132Sn

. Phys. Rev. C 71,High-precision, charge-dependent bonn nucleon-nucleon potential

. Phys. Rev. C. 63,Meson-exchange enhancement of the first-forbidden 96Yg(0-)→96Zrg(0+)βtransition: βdecay of the low-spin isomer of 96Y

. Phys. Rev. C 41, 226-242 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.41.226One-neutron stripping processes to excited states of the 6Li + 96Zr reaction at nearbarrier energies

. Phys. Rev. C 93,Effective interactions for the 0p1s0d nuclear shell-model space

. Phys. Rev. C. 46, 923 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.46.923Kinematical effects in heavy-ion reactions

. Phys. Lett. B 40, 37-40 (1972). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(72)90274-2Role of direct mechanism in two-nucleon t=0 transfer reactions in light nuclei using the (6Li, α) probe

. Phys. Rev. C 106,