Introduction

Medical isotopes refer to radioactive isotopes used in medical diagnosis, treatment, and research [1]. These isotopes typically possess half-lives and radioactive properties suitable for medical applications, enabling their use in imaging, diagnosis, and radiotherapy [2]. Globally, over 100 radioactive isotopes can be applied in the medical field, and more than 30 medical isotopes are currently utilized [3], including molybdenum-99 (99Mo), iodine-125 (125I), iodine-131 (131I), carbon-14 (14C), lutetium-177 (177Lu), ytterbium-90 (90Y), strontium-89 (89Sr). Among them, 99Mo is commonly used for single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging [4], 125I can be used for brachytherapy and radioimmunoanalysis [5], 131I is primarily used for the treatment of hyperthyroidism and thyroid cancer [6], 14C is used for respiratory test drugs and pharmacokinetic studies [7], and 177Lu is helpful for the targeted therapy of neuroendocrine tumors and prostate cancer [8]. Many other related applications [9, 10] have not been listed.

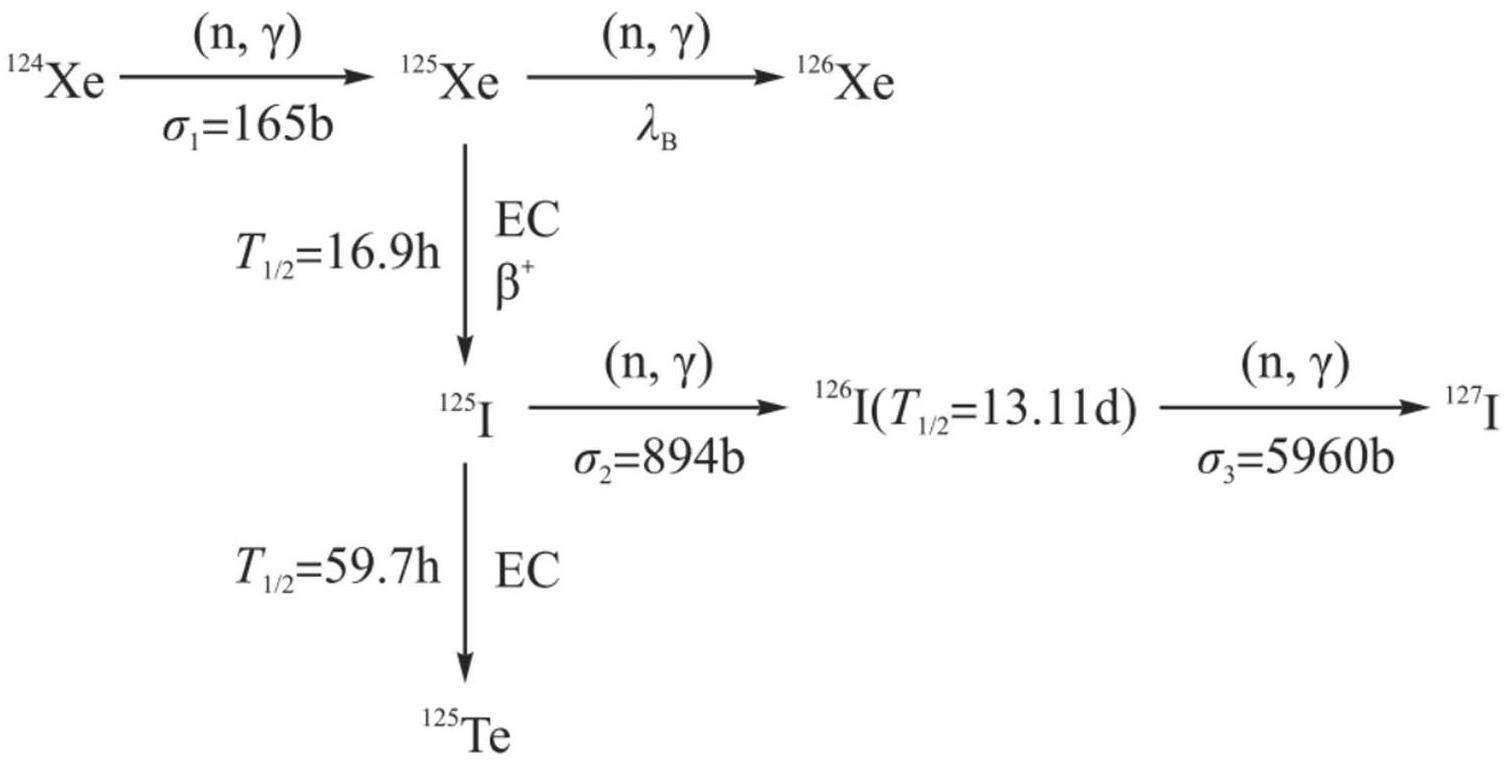

In-reactor irradiation is the primary approach for producing medical isotopes, accounting for 70–80% of the global medical isotope supply [11]. In-reactor medical isotope production involves complex nuclide-conversion processes. Taking the production of 125I from xenon-124 (124Xe) as an example [12], as shown in Fig. 1, 124Xe undergoes a single (n, γ) reaction to produce xenon-125 (125Xe) and then decays to 125I. If the nuclear reaction continues, xenon-126 (126Xe) is obtained, and this process generates unwanted impurities. Neutrons with different energy ranges exhibit different abilities to induce various nuclear reactions [13]. Nuclear reactions can be controlled by adjusting the neutron energy spectrum to enhance medical isotope production. Moreover, iodine-126 (126I) with high-energy radiation is also generated, which decreases the yield and quality of 125I. Therefore, highly enriched 124Xe is typically used for short-term irradiation to increase the 125I yield and reduce the 126I yield. Consequently, irradiation duration affects the nuclear reaction process, and a reasonable irradiation duration can effectively enhance the production of medical isotopes.

The global shortage of medical isotopes makes it crucial to enhance production efficiency. Nature has repeatedly called for attention to address the shortage of medical isotopes [14-16]. Increasing the yield of medical isotopes would benefit humans. Neutron spectrum regulation and irradiation duration optimization are primary technical approaches for improving the production efficiency of medical isotopes. However, the first step is to determine the optimal neutron spectrum for producing various medical isotopes under different irradiation durations, which necessitates the quantification of neutron values in different energy regions. Therefore, a dataset that provides neutron energy region values is essential for enhancing in-reactor medical isotope production.

We utilized the subgroup burnup analysis method [17] to quantify the value of neutrons in different energy regions for the in-reactor medical isotope production. This method considers all nuclides and neutron spectra throughout the irradiation period and constructs a dataset of neutron energy region values with a high spectral resolution across the entire energy region. Moreover, the extreme burnup analysis method [18] was employed to mitigate the influence of the irradiation duration on the neutron energy region values and thereby enhance the universality of the database. We performed neutron spectrum regulation based on this database, which effectively improved the production efficiency of medical isotopes, thereby demonstrating the correctness and feasibility of the database.

Models and methods

Reactor Models

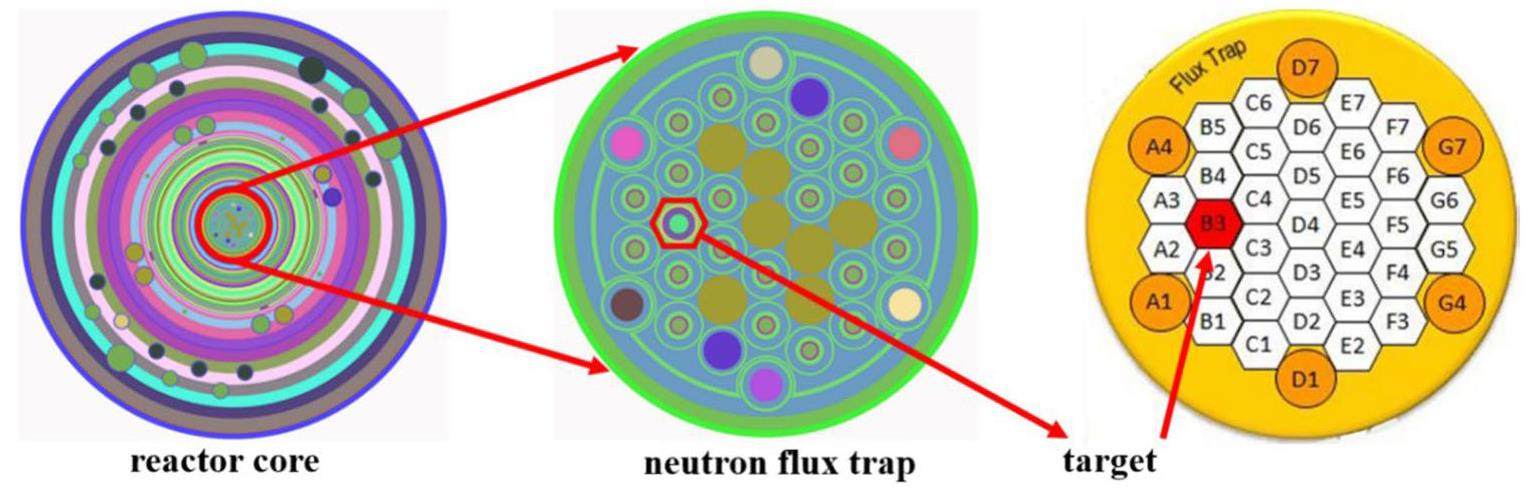

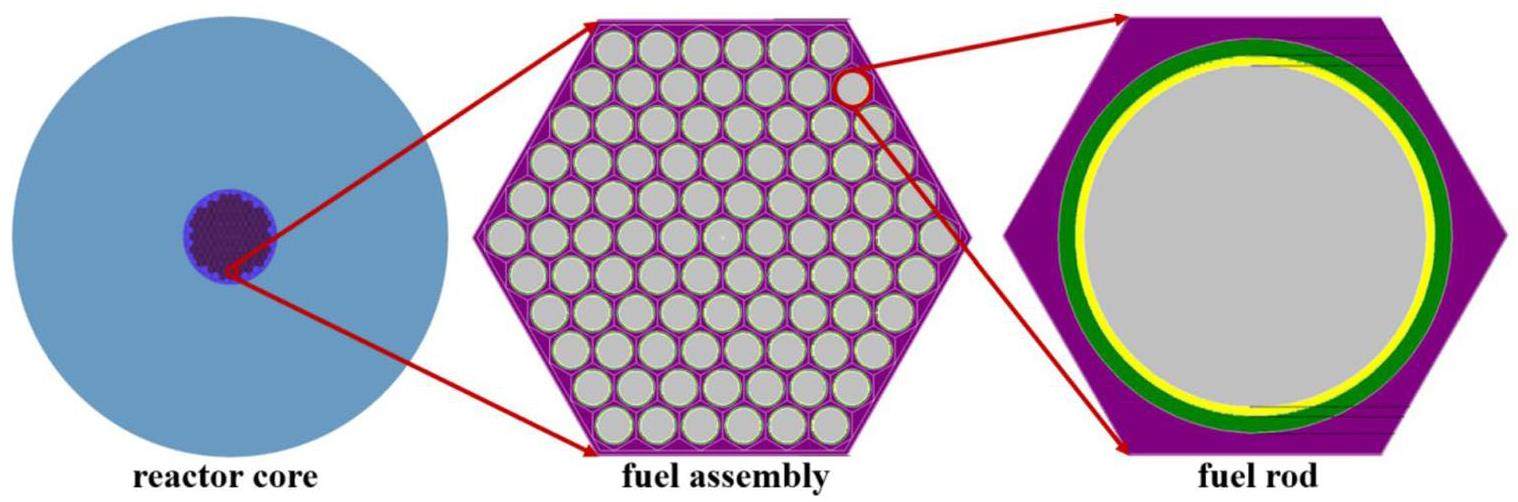

The dataset was simulated in the high-flux isotope reactor (HFIR) [18], which a multi-purpose isotope production and testing reactor with a current operating power of 85 MW. The HFIR operates on a cycle of 22–24 d and is capable of the world’s highest steady-state neutron thermal flux (2.6×1015 cm-2·s-1), making it a significant global production base for medical isotopes. We inserted a target assembly with a length of 50 cm and diameter of 0.85 cm inside the neutron trap to produce twenty medical isotopes (14C, 32P, 47Sc, 60Co, 64Cu, 67Cu, 89Sr, 90Y, 99Mo, 125I, 131I, 153Sm, 161Tb, 166Ho, 177Lu, 186Re, 188Re, 92Ir, 225Ac, 252Cf). The reactor Monte Carlo (RMC) code was utilized for modeling [19], as illustrated in Fig. 2. Moreover, because HFIR is a thermal reactor, we also performed the same simulations in a high-flux fast reactor (HFFR) [17] to enhance the universality of the database, as shown in Fig. 3.

Calculation Methods

The yields of medical isotopes can be obtained by performing a Monte Carlo burnup calculation that couples the Monte Carlo criticality and point burnup calculations. The point burnup equation describes the transmutation of nuclides with time and can be written as [20]:

One-group cross sections are required for the Monte Carlo burnup calculation, which is computed by the Monte Carlo criticality calculation:

The neutron flux and nuclear reaction rates are determined by solving Equation (3) and are used to determine the one-group cross sections:

As shown in Eqs. (1)–(4), the Monte Carlo burnup calculation can only quantify the production efficiency of the entire neutron spectrum, not each energy region, which leads to the unknown energy regions that are favorable and unfavorable for in-reactor medical isotope production. Therefore, two methods have been proposed for the high spectral resolution quantification of neutron energy region values: 1) the subgroup burnup analysis method and 2) the extremum burnup analysis method.

(1) Subgroup burnup analysis method: The neutron flux in each energy region is reduced during the Monte Carlo burnup calculation, and the influence of the flux reduction on the yield is observed, quantifying the neutron energy region values (labeled Ii), which are calculated using the following formula:

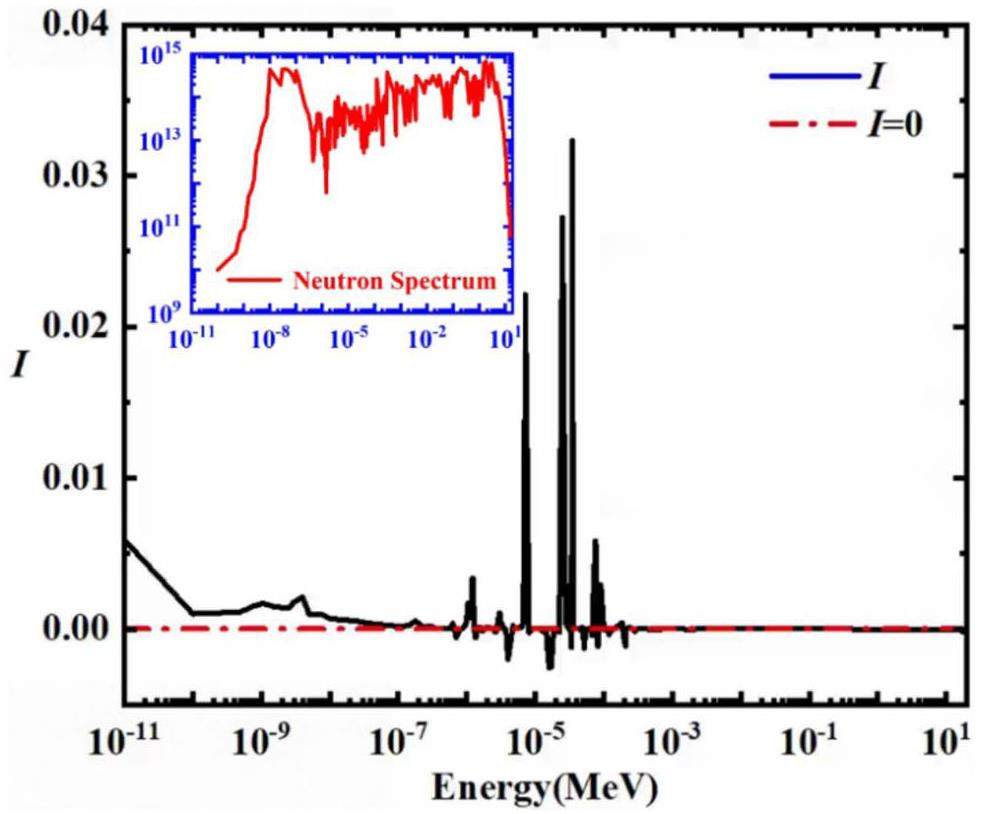

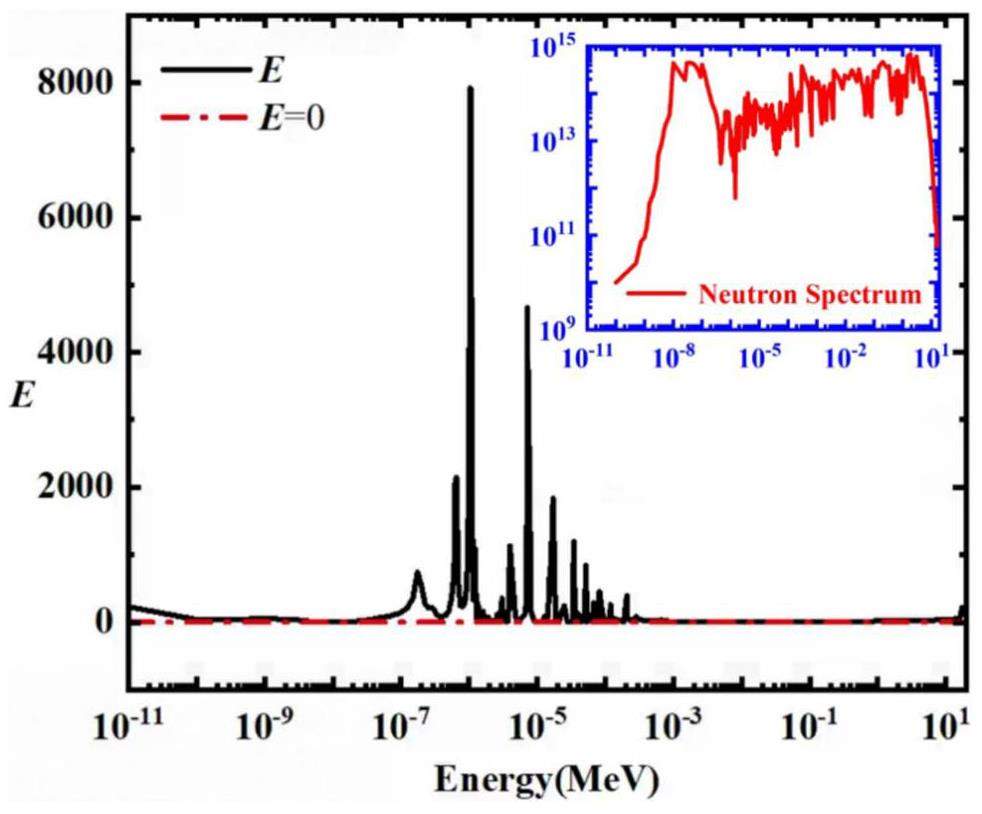

The subgroup burnup analysis method calculates the sensitivity of the relative change in the yield to the absolute change in the neutron flux in each energy region. To ensure the high spectral resolution of the dataset, the entire energy range was divided into 238 energy regions [21]. Moreover, the subgroup burnup analysis method has no restrictions on the energy division and can achieve a higher spectral resolution. Taking the 90 d irradiation production of californium-252 (252Cf) in the HFIR as an example [17], we obtained a neutron value curve across the entire energy range by calculating the neutron values for all 238 energy regions, as shown in Figure 4. We also provided the top-10 maximum and minimum values along the neutron value curve, as shown in Table 1.

| Largest | Smallest | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy regions (MeV) | Values | Energy regions (MeV) | Values |

| [9.00×10-5, 1.00×10-4] | 2.95×10-3 | [1.60×10-5, 1.70×10-5] | -2.57×10-3 |

| [1.20×10-6, 1.23×10-6] | 3.29×10-3 | [1.70×10-5, 1.85×10-5] | -2.51×10-3 |

| [1.23×10-6, 1.25×10-6] | 3.39×10-3 | [4.00×10-6, 4.75×10-6] | -1.99×10-3 |

| [7.20×10-5, 7.60×10-5] | 3.50×10-3 | [1.51×10-5, 1.60×10-5] | -1.30×10-3 |

| [7.60×10-5, 8.00×10-5] | 5.85×10-3 | [5.20×10-5, 5.34×10-5] | -1.28×10-3 |

| [1.00×10-11, 1.00×10-10] | 5.92×10-3 | [3.38×10-5, 3.46×10-5] | -1.21×10-3 |

| [7.00×10-6, 7.15×10-6] | 1.11×10-2 | [8.20×10-5, 9.00×10-5] | -1.13×10-3 |

| [7.15×10-6, 8.10×10-6] | 2.21×10-2 | [2.08×10-4, 2.10×10-4] | -1.12×10-3 |

| [2.50×10-5, 2.75×10-5] | 2.72×10-2 | [7.00×10-7, 7.50×10-7] | -5.70×10-4 |

| [3.46×10-5, 3.55×10-5] | 3.23×10-2 | [1.35×10-6, 1.40×10-6] | -5.70×10-4 |

(2) Extremum burnup analysis method: The irradiation duration significantly affected the neutron energy region values calculated by the subgroup burnup analysis method. For example, in some energy regions, if the irradiation time exceeds what is required for the yield to reach its peak, then a phenomenon in which the yield increases first and then decreases throughout the irradiation process occurs. This phenomenon is known as “over-irradiation.” In other energy regions, irradiation for this duration may not be sufficient to cause the yield to reach its peak. To address this issue, we employed the extreme burnup analysis method to eliminate the influence of the irradiation duration on the neutron energy region values. The extreme burnup analysis method determines the extreme value in terms of time, which is achieved by calculating the maximum derivative between the neutron energy region value and irradiation time, as shown in Eq. (6):

We divided the irradiation duration (90 d) into 20 equal time steps and performed calculations using the subgroup burnup analysis method for each time step, resulting in 20 neutron energy region values for all 238 energy regions. We then calculated the maximum derivative Ej,max between the neutron energy region value and irradiation time and used it as the final result to quantify the neutron values in each energy region. The extremum burnup analysis method also established an extreme neutron value curve, as shown in Fig. 5. The top 10 maximum and minimum values along the curve are listed in Table 2.

| Largest | Smallest | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy regions (MeV) | Values | Energy regions (MeV) | Values |

| [1.01×10-6, 1.02×10-6] | 3.77×104 | [5.00×10-9, 7.50×10-9] | -1.10×101 |

| [1.09×10-6, 1.10×10-6] | 4.56×104 | [7.50×10-9, 1.00×10-8] | -4.03×10-1 |

| [7.15×10-6, 8.10×10-6] | 4.66×104 | [1.85×10-5, 1.90×10-5] | 7.23×10-2 |

| [1.08×10-6, 1.09×10-6] | 5.28×104 | [5.00×10-6, 5.40×10-6] | 1.80×10-1 |

| [1.02×10-6, 1.03×10-6] | 5.53×104 | [2.70×10-1, 3.30×10-1] | 2.28×10-1 |

| [1.07×10-6, 1.08×10-6] | 6.52×104 | [3.30×10-1, 4.00×10-1] | 3.55×10-1 |

| [1.03×10-6, 1.04×10-6] | 7.21×104 | [2.00×10-1, 2.70×10-1] | 3.69×10-1 |

| [1.06×10-6, 1.07×10-6] | 7.43×104 | [1.50×10-1, 2.00×10-1] | 5.32×10-1 |

| [1.04×10-6, 1.05×10-6] | 7.60×104 | [4.00×10-1, 4.20×10-1] | 7.23×10-1 |

| [1.05×10-6, 1.06×10-6] | 7.92×104 | [1.28×10-1, 1.50×10-1] | 7.41×10-1 |

The maximum values indicate that neutrons in these energy regions are conducive. Hence, increasing the neutron flux in these energy regions (referred to as positive-energy regions) increases the yield of medical isotopes. Conversely, the minimum values suggest that neutrons in these energy regions are detrimental and that increasing the neutron flux in these regions (referred to as negative-energy regions) decreases the yield.

Based on the subgroup and extremum burnup analysis methods, we obtained high-resolution neutron energy region values across the entire energy range and built a dataset to determine the positive and negative energy regions. Increasing the neutron flux in positive-energy regions and reducing it in negative-energy regions can improve the yield of medical isotopes. Therefore, this dataset can help guide the neutron spectrum regulation process for in-reactor medical isotope production.

Data records

The dataset employs two methods (the subgroup burnup and extremum burnup analysis methods) to calculate the neutron energy region values across 238 energy regions for 20 medical isotopes (14C, 32P, 47Sc, 60Co, 64Cu, 67Cu, 89Sr, 90Y, 99Mo, 125I, 131I, 153Sm, 161Tb, 166Ho, 177Lu, 186Re, 188Re, 92Ir, 225Ac, 252Cf) in two reactor models (high-flux isotope and high-flux fast reactors). Consequently, there were a total of 2×2×20×238=19,040 neutron energy region values. We organized this dataset into a file named NERV.txt (meaning neutron energy region values), according to the format specified in Table 3. This dataset is available at https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.j00186.00468.

| Fixed format | Example |

|---|---|

| Isotope name (character×10 to the left) | C-14······ |

| HFIR subgroup (character×13 to the left) 24 lines with 10 values per line (character×13×10 to the left) ×24 | HFIR·Subgroup 0.00000E+00··0.00000E+00······················ |

| HFIR extremum (character×13 to the left) 24 lines with 10 values per line (character×13×10 to the left) ×24 | HFIR·Extremum 0.00000E+00··0.00000E+00······················ |

| HFFR subgroup (character×13 to the left) 24 lines with 10 values per line (character×13×10 to the left) ×24 | HFFR·Subgroup 0.00000E+00··0.00000E+00······················ |

| HFFR extremum (character×13 to the left) 24 lines with 10 values per line (character×13×10 to the left) ×24 | HFFR·Extremum 0.00000E+00··0.00000E+00······················ |

| Isotope Name (character×10 to the left) ··················· · · · | P-32························· · · · |

| · | · |

| · | · |

| · | · |

By downloading the NERV.txt file from the repository, readers can obtain the neutron energy region value in a specific energy region, calculated using either the subgroup burnup or extreme burnup analysis method, for the production of a certain medical isotope in HFFR or HFIR, according to the fixed format outlined in Table 3. For instance, if we wish to retrieve the neutron value for the 100th energy region, calculated by the extreme burnup analysis method, for the production of 131I in the HFFR reactor. This data should be located in the 10th column of the 1150th row in the NERV.txt file, with a value of 5.17959×10-15.

Validation and usage

Technical Validation

We constructed numerous neutron spectra by dispersing nuclides into target materials and verified whether the yields of the medical isotopes under these neutron spectra positively correlate with the total value of the neutron spectra (labeled as “T”), which is calculated by:

Taking Rhenium-188 (188Re) as an example, we selected ten nuclides (4He, 7Li, 50Cr, 64Ni, 73Ge, 75As, 130Ba,145Nd, 165Ho, 176Hf) with three added amounts (1018, 5×1018, and 1×1019 atom/cm3), resulting in 30 different neutron spectra. The correlation coefficient between ΔY and ΔT was calculated as follows:

| Nuclides | Addition amount | ΔT | ΔY |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4He | 1.00×1018 | –8.80×10-9 | –8.50×1017 |

| 5.00×1018 | 6.47×10-10 | –3.00×1017 | |

| 1.00×1019 | –1.10×10-9 | –5.10×1017 | |

| 7Li | 1.00×1018 | 7.85×10-9 | 2.66×1016 |

| 5.00×1018 | –1.70×10-9 | –5.70×1017 | |

| 1.00×1019 | –7.30×10-10 | –4.20×1017 | |

| 50Cr | 1.00×1018 | –5.20×10-9 | –7.40×1017 |

| 5.00×1018 | –6.30×10-9 | –8.90×1017 | |

| 1.00×1019 | –3.70×10-9 | –5.80×1017 | |

| 64Ni | 1.00×1018 | 2.81×10-9 | –1.50×1016 |

| 5.00×1018 | 2.92×10-9 | 8.95×1016 | |

| 1.00×1019 | 7.29×10-9 | 1.49×1017 | |

| 73Ge | 1.00×1018 | –4.60×10-10 | –2.00×1017 |

| 5.00×1018 | –7.40×10-9 | –7.70×1017 | |

| 1.00×1019 | 1.11×10-8 | 6.27×1017 | |

| 75As | 1.00×1018 | –1.30×10-9 | –2.91×1017 |

| 5.00×1018 | –3.40×10-9 | –4.23×1017 | |

| 1.00×1019 | –4.80×10-9 | –6.01×1017 | |

| 130Ba | 1.00×1018 | 2.31×10-9 | –2.42×1017 |

| 5.00×1018 | –1.50×10-9 | –7.63×1017 | |

| 1.00×1019 | 5.84×10-9 | –2.38× 1015 | |

| 145Nd | 1.00×1018 | –8.00×10-10 | –4.79×1017 |

| 5.00×1018 | –1.50×10-9 | –4.30×1017 | |

| 1.00×1019 | 1.58×10-11 | –3.18×1017 | |

| 165Ho | 1.00×1018 | 3.56×10-9 | 7.96×1016 |

| 5.00×1018 | 7.29×10-10 | –2.40×1017 | |

| 1.00×1019 | –8.40×10-9 | –1.10×1018 | |

| 176Hf | 1.00×1018 | 3.61×10-9 | 6.73×1016 |

| 5.00×1018 | –2.00×10-9 | –7.00×1017 | |

| 1.00×1019 | 7.00×10-9 | 1.95×1017 | |

| Correlation coefficients between ΔY and ΔT | 0.9409 | ||

As shown in Table 4, ΔY exhibits a positive correlation with ΔT, with a correlation coefficient of 0.9409, meaning that as the total value of the neutron spectra increases, the yield of the medical isotopes also increases. Therefore, a dataset of the neutron energy region values can guide neutron spectrum regulation to enhance in-reactor medical isotope production.

Applications

The dataset of the neutron energy region values identified the positive- and negative-energy regions for producing various medical isotopes. Theoretically, the production efficiency of medical isotopes can be increased by reducing the neutron flux in negative-energy regions. We adopted the neutron spectrum filtering technology [18] to reduce the neutron flux in the negative energy regions, which disperses nuclides with resonance peaks in the negative energy regions to the target material. The effects of adding filter nuclides on the final yields, using the production of 47Sc, 64Cu, 67Cu, 90Y, and 188Re as examples, are shown in Table 5.

| Medical isotopes | Filter nuclides | Addition amount (atom/cm3) | Yield before filter (atom/cm3) | Yield after filter (atom/cm3) | ΔY (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 47Sc | 153Gd | 5.00×1018 | 3.06×1017 | 7.19×1017 | 135.30% |

| 155Gd | 5.00×1018 | 3.06×1017 | 1.54×1017 | 154.10% | |

| 64Cu | 157Gd | 5.00×1018 | 1.50×1019 | 1.84×1019 | 22.49% |

| 149Sm | 5.00×1018 | 1.50×1019 | 2.58×1019 | 72.28% | |

| 67Cu | 155Gd | 5.00×1018 | 2.83×1016 | 3.10×1016 | 9.43% |

| 157Gd | 5.00×1018 | 2.83×1016 | 5.00×1016 | 76.40% | |

| 90Y | 157Gd | 5.00×1018 | 2.81×1020 | 3.83×1020 | 36.23% |

| 149Sm | 5.00×1018 | 2.81×1020 | 3.69×1020 | 31.26% | |

| 188Re | 243Cm | 5.00×1018 | 1.15×1019 | 1.47×1019 | 27.60% |

| 245Cm | 5.00×1018 | 1.15×1019 | 2.02×1019 | 75.20% |

Table 5 shows that when 5.00×1018 atom/cm3 of 155Gd was dispersed into the target for producing 47Sc, the yield of 47Sc increased by 154%, which is an impressive result. The yields of medical isotopes increased significantly, proving that the dataset of neutron energy region values can be used for neutron spectrum regulation to enhance the production of medical isotopes. This dataset enables the rapid identification of positive- and negative-energy regions for producing these 20 medical isotopes in fast or thermal reactors. The production efficiency of medical isotopes can be effectively improved by increasing the neutron flux in positive-energy regions and reducing it in negative-energy regions. Additionally, this dataset can be used for the rapid evaluation and comparison of the economics of different irradiation schemes. As shown in Eq. (7), the total value of the neutron spectrum of an irradiation scheme can be calculated, and schemes with higher total neutron spectrum values are more economically viable.

Data Availability

The process files generated during the calculation of this dataset can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.j00186.00468. The calculation results of the subgroup burnup analysis method for each medical isotope can be viewed in the “Subgroup burnup” folder, which contains the raw data records and yields of this medical isotope after flux reduction in each energy region along with the corresponding neutron value curves and top 10 maximum and minimum values within the neutron value curves. The calculation results of the extreme burnup analysis method for each medical isotope can be accessed in the “Extremum burnup” folder, which records the yields of this medical isotope after flux reduction in each energy region across the 20 time steps as well as the corresponding extreme neutron value curves and top-10 maximum and minimum values within the curves.

Both the folders named “Subgroup burnup” and “Extremum burnup” contain two subfolders each, named “HFFR” and “HFIR,” which represent the computational data from these two reactors. Furthermore, both the “HFFR” and “HFIR” folders were further divided into 20 subfolders, with each named after the 20 medical isotopes covered in this dataset. These 20 subfolders were not further subdivided and contained the lowest-level data information from the computational process.

The raw data for use in technical validation and applications are stored in the “Spectrum Regulation” folder, which contains two folders named “Technical Validation” and “Application”. The “Technical Validation” folder includes 10 subfolders and an Excel sheet, which provide detailed data for technical validation. The “Application” Folder contains 5 subfolders and an Excel sheet that offer detailed data on the application process.

Accelerating production of medical isotopes

. Nature 457, 536-537, (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/457536aThe use of isotopes in medical research

. J. American Med. Associat. 134(3), 219-225, (1947). https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1947.02880200001001A picture of modern Tc-99m radiopharmaceuticals: Production, chemistry, and applications in molecular imaging

. Appl. Sci. 9(12), 2526, (2019). https://doi.org/10.3390/app9122526A Monte Carlo dose recalculation pipeline for durable datasets: an I-125 LDR prostate brachytherapy use case

. Phys. Med. Biol. 68,Feasibility study for production of I-131 radioisotope using MNSR research reactor

. Appl. Radiat. Isot.70(1), 76-80 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apradiso.2011.08.011Effect of helicobacter pylori infection on glucose metabolism, lipid metabolism and inflammatory cytokines in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease patients

. J. Multidisciplinary Healthcare 17, 1127-1135, (2024). https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S453429Production of 177Lu for targeted radionuclide therapy: available options

. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 49, 85-107 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13139-014-0315-zStrontium-89 plus zoledronic acid versus zoledronic acid for patients with painful bone metastatic breast cancer

. J. Bone Miner. Metabol. 40, 998-1006 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00774-022-01366-yRecommendations for the management of yttrium-90 radioembolization in the treatment of patients with colorectal cancer liver metastases: a multidisciplinary review

. Clinic. Trans. Oncol. 26, 851-863 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-023-03299-yProduction of iodine-124 and its applications in nuclear medicine

. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 90, 138-148 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apradiso.2014.03.026ENDF/B-VII.1 Nuclear Data for Science and Technology: Cross Sections, Covariances, Fission Product Yields and Decay Data

. Nuclear Data Sheets 112(12), 2887-2996 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nds.2011.11.002Researchers urge action on medical isotope shortage

. Nature 459, 1045 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/4591045bReactor shutdown threatens world’s medical isotope supply

. Nature (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature.2016.20577Medical isotope shortage reaches crisis level

. Nature 460, 312-313, (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/460312aSpectrum importance model for heavy nuclei synthesis in reactors: Taking 252Cf as an example

. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 57,Modeling of the high flux isotope reactor Cycle 400 with KENO-VI

. Transactions of the American Nuclear Society 104(1) (2011). https://www.ans.org/pubs/transactions/article-12169/RMC – A Monte Carlo code for reactor core analysis

. Ann. Nucl. Energ. 82, 121-129, (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anucene.2014.08.048Development of the point-depletion code DEPTH

. Nucl. Eng. Des. 258, 235-240 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nucengdes.2013.01.007Analysis of major group structures used for nuclear reactor simulations

.Xiao-Jing Liu is an editorial board member for Nuclear Science and Techniques and was not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.