Introduction

Tungsten is considered the most promising plasma-facing material (PFM) for fusion reactors. Tungsten PFMs have been adopted in several tokamaks such as JET, ASDEX-Upgrade, WEST, and EAST [1-5]. It was confirmed that tungsten PFMs could also be adopted in ITER, the most ambitious energy project in the world today, with 500 fusion power [6]. Deuterium (D) and tritium (T) are the fuels used in fusion reactors. High-energy neutrons can be produced during D-T nuclear reactions. The activation of materials caused by neutrons is the main radioactive source, in addition to tritium, for fusion reactions [7, 8]. Most of the activated materials do not pose an environmental threat because almost all of the materials cannot be mobilized, except for the typical activated tungsten dust [9, 10]. Experimental evidence in tokamaks has confirmed that tungsten dust can be produced by plasma wall interactions (PWI) [11]. The accumulated quantity in a vacuum vessel increases with operation time. To decrease the risk of severe accidents such as dust and hydrogen explosions, safety limits of 1000 activated tungsten dust and 1 tritium were set for ITER [12]. Once the limit is reached, the activated tungsten dust should be removed and transferred to a hot cell for temporary storage.

Despite the implementation of essential measures for fusion reactors, the risk of the release of activated tungsten dust into the environment persists under two specific conditions. According to previous studies, the particle size distribution of tungsten dust generated in fusion devices ranges from approximately ten nanometers to several tens of micrometers and follows a log-normal distribution [13, 14]. During the normal operation of fusion reactors, a high-efficiency particulate air system (HEPA) is used to mitigate the release of dust [15]. However, investigations have found that the HEPA filter efficiency decreases for dust smaller than 300 [16]. Therefore, activated tungsten dust particles smaller than 300 may pose safety concerns during normal operations. In addition, potential releases can occur under accidental conditions, particularly in beyond design-basis accidents, such as damage to vacuum vessels and cryostats, as well as wet bypasses, as identified by ITER, EU-DEMO, and PPCS [17-19]. In these accidents, the radiation dose caused by the activated tungsten dust was calculated to be larger than that caused by tritium.

Following its release into the environment, activated tungsten dust can be deposited on the soil surface by turbulent mixing and gravitational deposition [20, 21]. In soil, tungsten undergoes a cascade of migration and transformation processes that remain largely unexplored [22-24]. For radiation dose assessment, the external radiation dose due to ground shine must be considered. As dust migrates into deeper soil through chemical transformations and physical transportation processes, gamma rays are attenuated because of the shielding effect of the soil layer [25, 26]. Although many previous studies have evaluated the radiation shielding characteristics of various new materials [27, 28], the soil attenuation characteristics of gamma radiation from activated tungsten dust have not yet been reported. To accurately assess the air-absorbed dose rates of the deposited activated tungsten dust at various soil depths, this study investigated the attenuation characteristics of gamma rays emitted from activated tungsten dust using the open-source Monte Carlo program Geant4. Verification with NIST-XCOM was performed to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the model developed using Geant4. The mass attenuation factor was obtained for gamma rays emitted from the activated tungsten dust at various energies. Furthermore, the energy absorption build-up values were predicted by considering secondary scattering photons. The impact of the air absorbed dose rates was estimated under various conditions at different soil depths and horizontal distances. The predicted results enhance the accuracy of radiation dose assessments related to environmental release of activated tungsten dust. This methodology can be extrapolated to calculate the surface sedimentary external radiation of other radionuclides.

Materials and methods

Radioactivity of activated tungsten dust

Referring to the activation characteristics predicted for the ITER, the composition of the radionuclides and their physical characteristics are listed in Table 1 [29]. 187W contributes most to the total radioactivity, followed by 185W and 181W. The highest specific radioactivity is observed for e11Bq/g. The minimum and maximum energies of the gamma rays are 55.8 keV, emitted from 179Ta, and 1332.5 keV, emitted from 60Co.

| Radionuclides | Specific activity ((Bq/g) at t=0 s) | Half-life | Main energy (keV) | Intensity (%) | MAC_soil (cm2/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 187W | 1.04×1011 | 24 h | 479.5, 685.8 | 26.60, 33.20 | 0.088, 0.076 |

| 185W | 3.72×1010 | 75 d | 125.3 | 0.02 | 0.149 |

| 181W | 1.43×1010 | 121 d | 57.5 | 32.00 | 0.307 |

| 186Re | 1.97×109 | 89 h | 137.2 | 9.47 | 0.142 |

| 188Re | 1.19×109 | 17 h | 155.0 | 15.49 | 0.134 |

| 182Ta | 1.67×108 | 115 d | 1121.3, 1221.4 | 35.24, 27.23 | 0.060, 0.057 |

| 186Ta | 6.40×107 | 10 m | 510.6, 615.3, 737.5 | 37.00, 28.00, 29.00 | 0.086, 0.080, 0.074 |

| 183Ta | 6.40×107 | 5 d | 59.3, 246.1, 354.0 | 42.10, 27.20, 11.60 | 0.301, 0.113, 0.099 |

| 184Ta | 4.33×107 | 9 h | 414.0, 920.9 | 72.00, 32.00 | 0.094, 0.066 |

| 179Ta | 2.74×107 | 2 y | 55.8 | 21.80 | 0.313 |

| 184Re | 1.99×107 | 35 d | 792.1, 903.3 | 27.70, 38.10 | 0.071,0.067 |

| 110mAg | 3.72×105 | 250 d | 657.8 | 95.61 | 0.077 |

| 58Co | 1.14×106 | 71 d | 810.8 | 99.50 | 0.070 |

| 60Co | 1.27×106 | 1925d | 1173.2, 1332.5 | 99.85, 99.98 | 0.059, 0.055 |

| 54Mn | 2.57×105 | 312 d | 834.9 | 99.98 | 0.070 |

Theoretical basis

The narrow-beam attenuation law is a fundamental principle that describes the decrease in photons while maintaining constant energy and passing through materials. The narrow-beam attenuation law is described by Eq. 1 [30]. The mass attenuation coefficient (MAC) depends on the energy of the gamma rays and material properties [31]. Mean free path (MFP) shown in Eq. 2 represents the average distance that a photon travels within a material before a collision occurs.

Secondary scattered photons should not be ignored when calculating photon attenuation effects in materials such as concrete [32], rock [33], and polyester resins [34]. To evaluate the contribution of secondary scattered photons, a broad-beam attenuation law was established by introducing a build-up factor, which is the ratio of the total photon flux to the non-colliding photon flux based on the mass attenuation factor. The broad-beam attenuation law is described in Eq. 3.

The air-absorbed dose rate was calculated using Eq. 5.

Monte Carlo simulation for gamma photon emitted from different soil depth

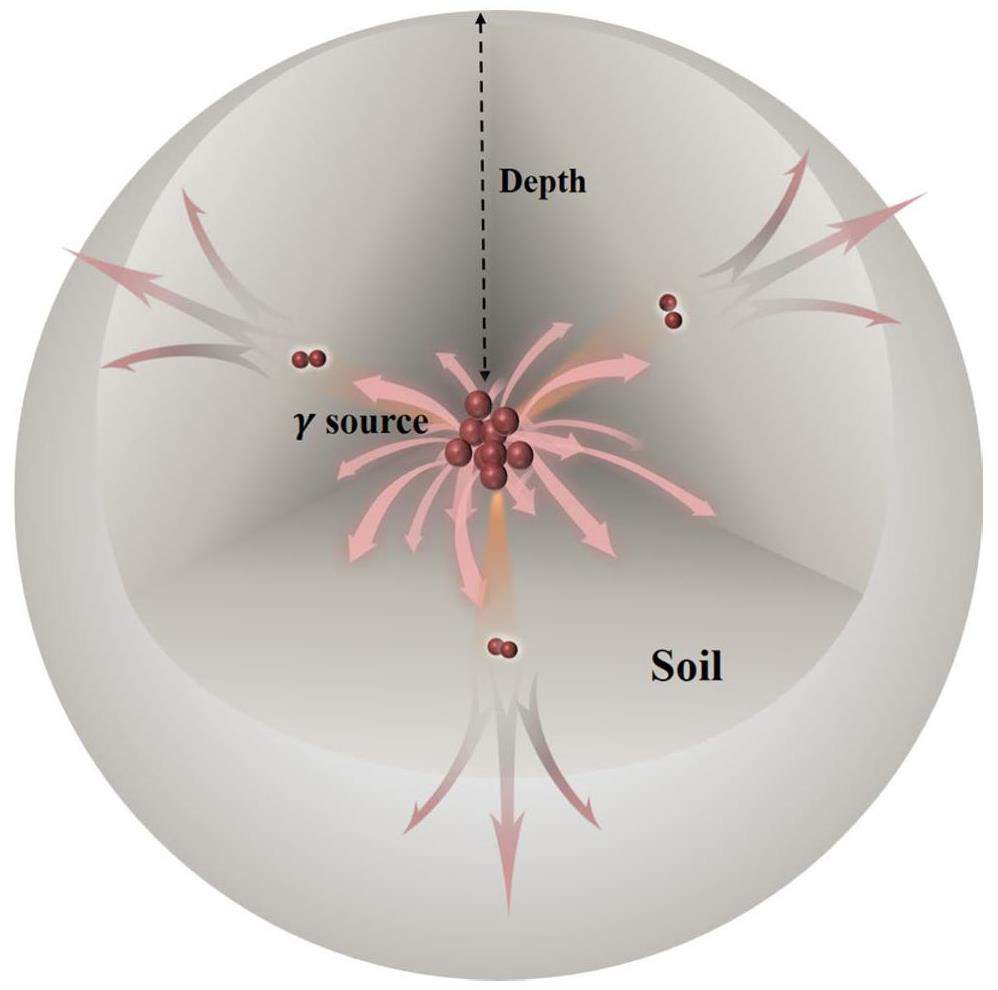

Invariant embedding, G-P fitting, and Monte Carlo methods have traditionally been used to calculate the EABF [36-38]. The Monte Carlo method offers distinct advantages owing to its ability to comprehensively account for various effects, such as bremsstrahlung radiation, Compton scattering, and X-ray fluorescence [35]. This capability stems from continuous updates and enhancements in the latest versions, including expanded libraries containing particle cross-sections and detailed models of the physical processes governing particle transport within the medium. In this study, we calculated gamma photon transport in the soil medium using the Monte Carlo simulation program Geant4-v11.1.2. Geant4 is an open-source tool based on the Monte Carlo method that is used to simulate the transport of particles through different materials. This tool is widely used in high-energy physics calculations, nuclear physics simulations, accelerator physics modeling, and the prediction of the effects of nuclear medicine. The spherical soil model illustrated in Fig. 1 was developed to evaluate the relationship between the MAC, MFP, EABF, and soil thickness. In this model, the soil sphere surrounds an isotropic photon source. We created our own physics list, including electromagnetic and hadronic interactions as well as decays. A detailed physical treatment of the photon interactions was performed, including the photoelectric effect, Compton scattering, and pair production. The generation of electrons from photons was also considered. The GEANT4 class G4RadioactiveDecayPhysics was included to account for the decay of radionuclide particles. The particle source was an isotropic radioactive source, and the number of events was greater than e8. The photons were collected on the surface of the soil sphere after passing through spherical soil of a certain thickness.

The primary energy of radionuclides in activated tungsten dust ranges from 55.8 keV to 1332.5 keV. Therefore, the photon energy was chosen in the following ranges: from 50 keV to 700 keV, from 700 keV to 1200 keV, and from 1200 keV to 2000 keV, with an interval of 50 keV, 100 keV, 200 keV, respectively. In this study, the mass attenuation coefficients of various photon energies were determined using the XCOM and Geant4 programs, and the statistical errors of all simulations were set to within 1%. The calculation results of the two programs were compared to verify the accuracy of Geant4 program. The MFP values of the soil samples were derived from the mass attenuation coefficients. Finally, 1 MFP, 3 MFP, 5 MFP, 7 MFP and 10 MFP were selected as the soil thicknesses, and the energy spectra after passing through the soil samples were collected to study the effects of secondary photon scattering on the attenuation performance of the soil.

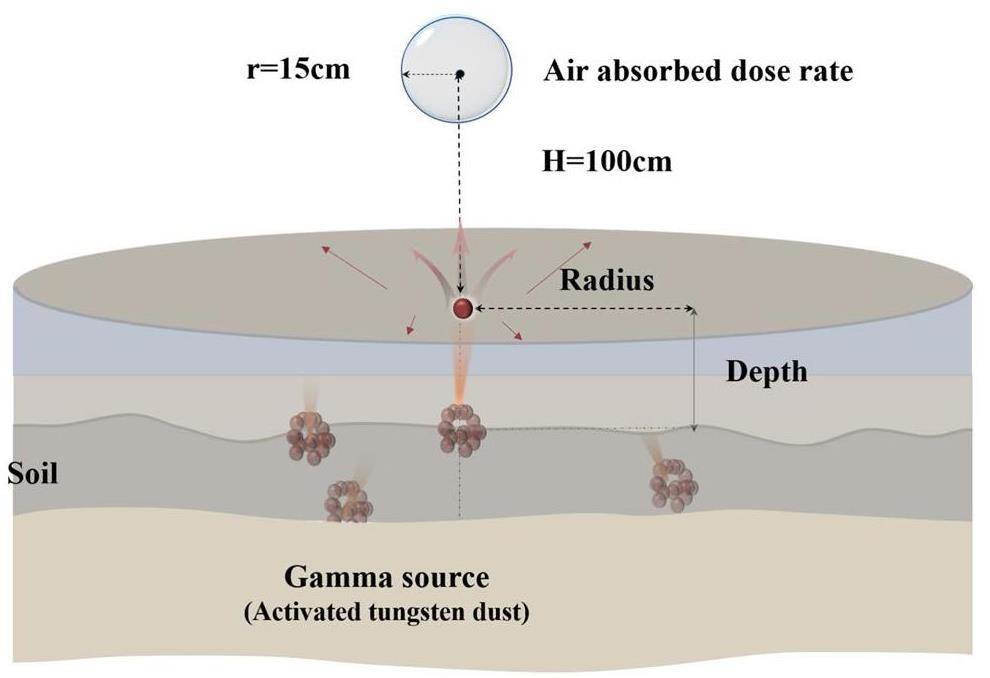

Once the soil attenuation law was obtained, a realistic flat soil model was established, as shown in Fig. 2 by building a 3D cylindrical model with a depth of 50 cm and a radius of 500 cm. A model with a radius of 1500 cm was built to discuss the dose contributions of areas with different radii. A unit quality-activated tungsten source of 1 g/cm2 was defined to perform the dose assessment. A sphere with a radius of 15 cm was set 100 cm above the soil surface to collect photons and calculate air-absorbed dose rates [39]. The sphere was made of GEANT4 material G4_AIR with a density of 1.20479 mg/cm3. It consisted of 0.01% carbon, 75.53% nitrogen, 23.18% oxygen, and 1.28% argon. Isotropic particle point sources were positioned at various radii and depths, and photons were collected in the sphere using the same method. We calculated the air-absorbed dose rates of the point sources at different radii and depths, and subsequently obtained the air-absorbed dose rates from the planar source by integrating these point sources. Sensitivity analysis was performed by assuming that the activated tungsten source was located at depths of 1 cm, 2 cm, 5 cm, 10 cm, 15 cm, 20 cm, 30 cm, 40 cm, and 50 cm, and at radii of 0 cm, 50 cm, 100 cm, 200 cm, 300 cm, and 500 cm.

Soil sampling and composition

Eight soil samples with different compositions are listed in Table 1. All soils were obtained from Shandong Province, China [40]. Soil type is related to the Si content of the soil. There were eight soil samples with decreasing Si content, as presented in Table 2.

| Component | Soil1 | Soil2 | Soil3 | Soil4 | Soil5 | Soil6 | Soil7 | Soil8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Si | 0.3358 | 0.3247 | 0.3192 | 0.2834 | 0.2801 | 0.2745 | 0.2443 | 0.2401 |

| Al | 0.0610 | 0.0664 | 0.0681 | 0.0658 | 0.0688 | 0.0739 | 0.0725 | 0.0746 |

| Fe | 0.0244 | 0.0229 | 0.0288 | 0.0304 | 0.0328 | 0.0360 | 0.0391 | 0.0426 |

| Ca | 0.0082 | 0.0127 | 0.0116 | 0.0304 | 0.0311 | 0.0276 | 0.0504 | 0.0559 |

| Mg | 0.0053 | 0.0062 | 0.0071 | 0.0101 | 0.0106 | 0.0118 | 0.0126 | 0.0158 |

| K | 0.0188 | 0.0227 | 0.0185 | 0.0193 | 0.0180 | 0.0198 | 0.0202 | 0.0221 |

| Na | 0.0131 | 0.0162 | 0.0156 | 0.0127 | 0.0121 | 0.0110 | 0.0091 | 0.0084 |

| C | 0.0176 | 0.0170 | 0.0173 | 0.0297 | 0.0332 | 0.0357 | 0.0531 | 0.0424 |

| Mn | 0.0007 | 0.0005 | 0.0006 | 0.0005 | 0.0006 | 0.0006 | 0.0008 | 0.0008 |

| N | 0.0008 | 0.0008 | 0.0009 | 0.0011 | 0.0010 | 0.0011 | 0.0020 | 0.0016 |

| P | 0.0005 | 0.0006 | 0.0007 | 0.0011 | 0.0009 | 0.0008 | 0.0008 | 0.0011 |

| S | 0.0003 | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.0003 | 0.0004 | 0.0003 | 0.0022 | 0.0004 |

| Ti | 0.0033 | 0.0029 | 0.0037 | 0.0037 | 0.0039 | 0.0041 | 0.0038 | 0.0038 |

| O | 0.5101 | 0.5063 | 0.5078 | 0.5115 | 0.5067 | 0.5028 | 0.4891 | 0.4905 |

| Density(g/cm3) | 1.54 | 1.39 | 1.43 | 1.48 | 1.46 | 1.41 | 1.37 | 1.41 |

Results and discussion

Method verification

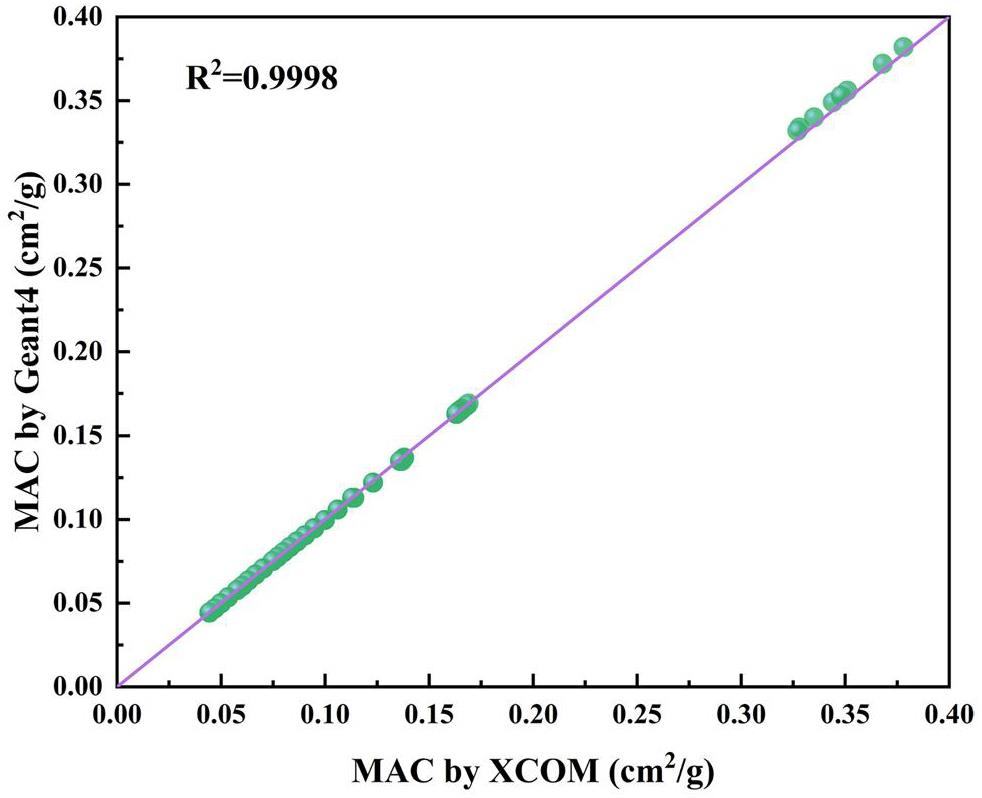

Theoretical MAC values are commonly obtained from radiation shielding calculation programs, such as NIST-XCOM, developed by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in the United States [41]. To verify the reliability of Geant4 model, it was compared with NIST-XCOM. The photon energy spectra of the eight soil samples were collected after traversing a 5 cm soil layer in the energy band of 50 keV to 2 MeV. As shown in Fig. 3, the narrow-beam attenuation results agreed well with the theoretical values obtained from NIST-XCOM calculations. The deviation between the simulation results obtained using Geant4 and the theoretical values obtained using NIST-XCOM was less than 1.8%, and the R-square (R2) was 0.9998, providing a visual demonstration of the model correctness.

MAC and EABF of soil samples

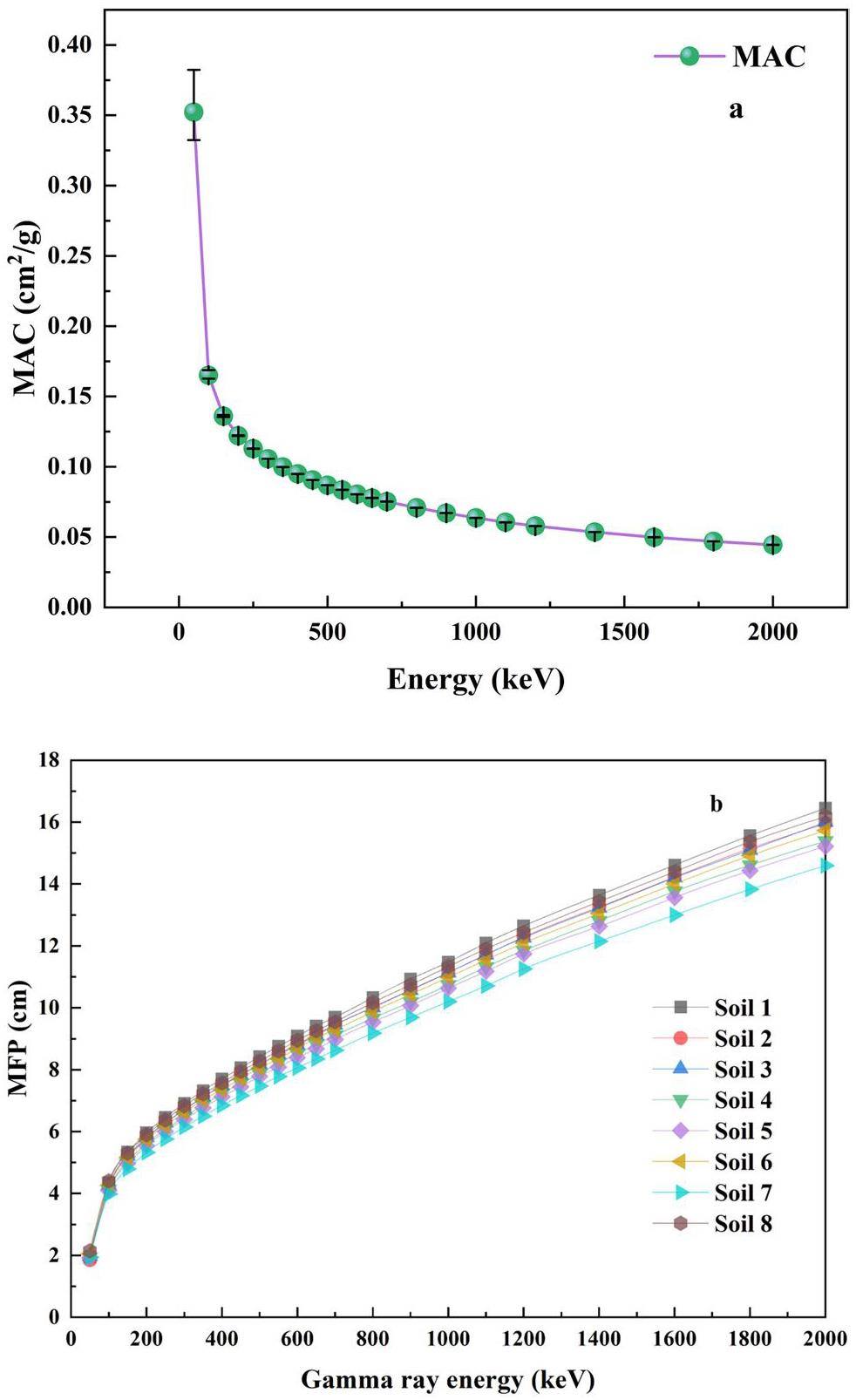

The MAC values of the eight soil samples were obtained using the Geant4 simulation program. Figure 4(a) shows the average MAC values for the eight soil samples, with error bars indicating the maximum and minimum values. The MAC values for the photon energy in the high-energy band were almost the same for the eight soil samples, whereas they varied significantly in the low-energy band (<100 keV). For low photon energies ranging from 50 keV to 200 keV, the mean MAC values decreased rapidly with increasing gamma energy, primarily because of the predominance of the absorbed photoelectric effect. The mean MAC values ranged from 0.352cm2/g to 0.122cm2/g between 50 keV and 200 keV, and from 0.122cm2/g to 0.044cm2/gbetween 0.2 MeV and 2 MeV. Soil 8 exhibited the highest variation in MAC values, ranging from 0.382cm2/g to 0.122cm2/g between 50 keV and 200 keV, and from 0.122cm2/g to 0.044cm2/g between 0.2 MeV and 2 MeV. This is because Soil 8 contained more nuclides with a high mass number, such as iron (Fe) and calcium (Ca), than the other soils. Figure 4(b) shows that the MFP values of all soil samples increased gradually with the photon energy. This indicates that the radiation attenuation properties of the soil decreased with increasing energy. The relative deviation of the MFP values among different soil samples was larger than that of the MAC values, highlighting the importance of soil density in soil attenuation. The higher the density, the more pronounced the attenuation effect.

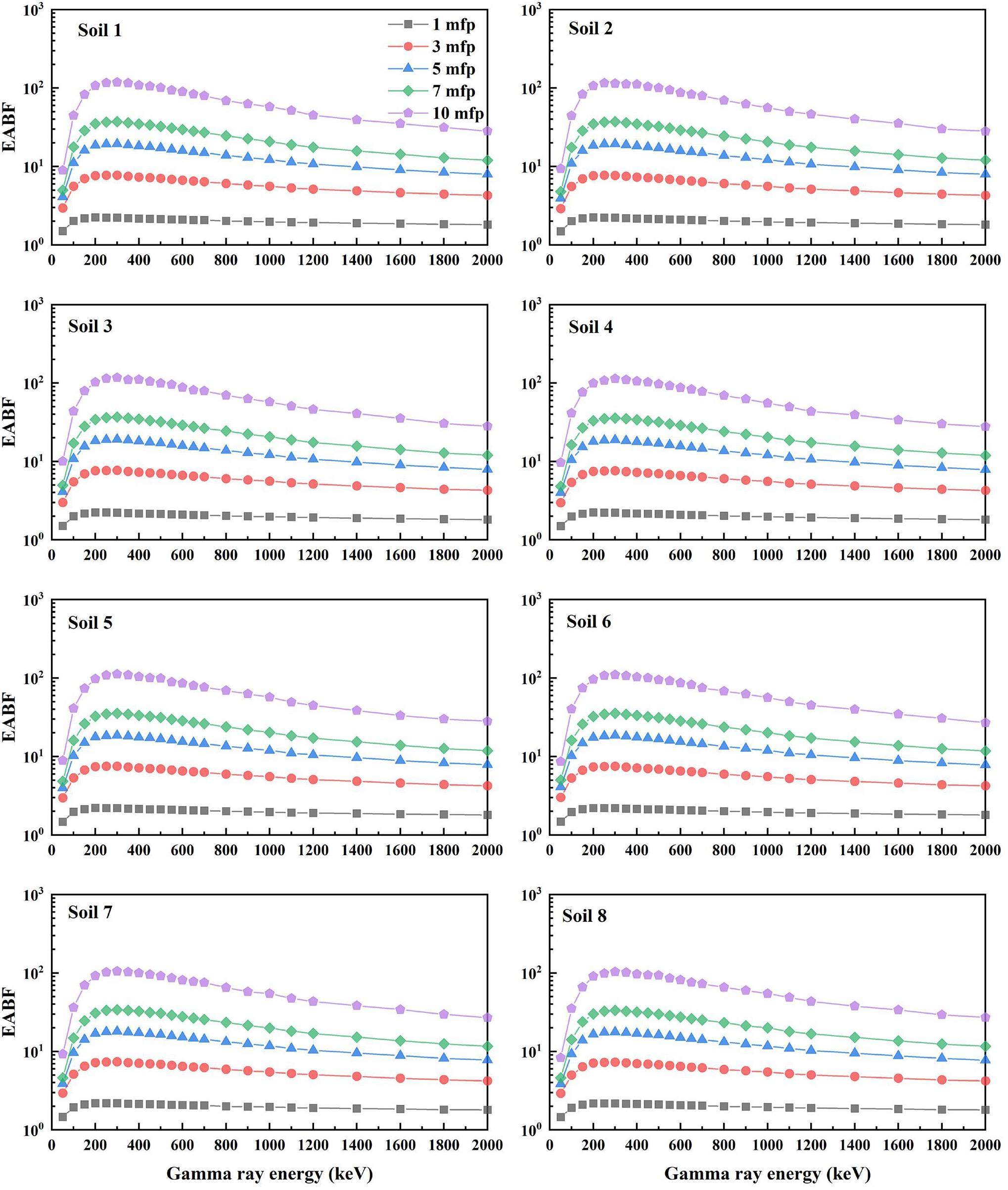

To consider the contribution of the secondary scattered photons, the EABF values were calculated, as shown in Fig. 5, for the eight soil samples based on soil thicknesses of 1 MFP, 3 MFP, 5 MFP, 7 MFP, and 10 MFP in the energy band from 50 keV to 2 MeV.

As shown in Fig. 5, the EABF values tended to increase with the overall MFP. This is because the probability of particle-matter collisions increases with increasing soil thickness, leading to more secondary scattering of photons. In the low-energy band, the photoelectric absorption effect causes the low-energy photons to be absorbed too quickly for scattering, resulting in low EABF values. Peak EABF values occur in the medium-energy band because Compton scattering is the main source of secondary-scattering photons. It is worth noting that the gamma ray energy corresponding to the EABF peak increased with increasing MFP because lower-energy photons are rapidly absorbed during deep penetration. In the high-energy band, pair production is another absorption process that influences the build-up factor by reducing the high-energy photon scattering within the soil sample. However, pair production can also contribute to the newly generated scattered photons through bremsstrahlung. Consequently, the EABF values tended to stabilize at intermediate values. This phenomenon highlights the complex interaction between the absorption and scattering mechanisms in soil samples, ultimately resulting in the complex attenuation characteristics of gamma rays passing through the soil.

Based on the EABF comparison of the various soil samples, the EABF values at the same MFP gradually decreased with decreasing Si content. However, this variation had only a small impact on the EABF. For instance, the EABF value decreased by 12% for the different soil samples with the lowest and highest Si content. However, the EABF value at 10 MFP was approximately 50 times higher than that at 1 MFP when the gamma-ray energy was 300 keV. Therefore, the EABF values mainly depended on the soil depth rather than the soil type.

The EABF values for typical radionuclides of activated tungsten dust are listed in Table 3 based on the primary energy and branching ratios shown in Table 1. Soil attenuation characteristics vary for radionuclides in activated tungsten dust. Evidently, 181W and 179Ta had low EABF values because of their primary energies of 57.5 keV and 55.8 keV, respectively, where the photoelectric absorption effect predominated. In contrast, 188Ta, 186Ta, and 184Ta had larger branching ratios in the middle-energy band, where the percentage of Compton effects increased, leading to high EABF values. The EABF values of 182Ta and 60Co were intermediate because their primary energies were concentrated in the high-energy band above 1000 keV, where pair production predominates. Among the main contributing radionuclides [42], the EABF values of 187W, 181W, 182Ta, and 60Co were 68.54, 14.39, 37.23, and 44.92 at 10 MFP. Therefore, scattered photons cannot be ignored when evaluating the dose of migrating activated tungsten dust in soil.

| Radionuclides | 1 MFP | 3 MFP | 5 MFP | 7 MFP | 10 MFP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 187W | 1.98 | 5.87 | 13.14 | 23.32 | 68.54 |

| 185W | 1.85 | 4.85 | 9.38 | 15.11 | 40.00 |

| 181W | 1.57 | 3.29 | 4.94 | 6.58 | 14.39 |

| 186Re | 2.01 | 5.88 | 12.48 | 21.35 | 59.85 |

| 188Re | 2.19 | 7.05 | 16.21 | 29.14 | 85.59 |

| 182Ta | 1.84 | 4.70 | 9.14 | 14.52 | 37.23 |

| 186Ta | 2.13 | 6.87 | 16.29 | 30.02 | 90.70 |

| 183Ta | 1.87 | 5.19 | 10.89 | 18.86 | 54.51 |

| 184Ta | 2.10 | 6.69 | 15.86 | 29.19 | 88.58 |

| 179Ta | 1.55 | 3.20 | 4.70 | 6.15 | 13.18 |

| 184Re | 1.90 | 5.21 | 10.91 | 18.34 | 50.20 |

| 110mAg | 2.02 | 5.98 | 13.53 | 23.79 | 68.12 |

| 58Co | 2.05 | 6.27 | 14.52 | 26.05 | 75.98 |

| 60Co | 1.92 | 5.10 | 10.51 | 17.17 | 44.92 |

| 54Mn | 2.02 | 5.98 | 13.54 | 23.75 | 67.26 |

Dose rate of planar radioactive sources

Under accidental conditions, activated tungsten dust can be deposited on the soil surface and can migrate to deeper soil layers after being released into the atmosphere. Therefore, the air-absorbed dose rates of planar radioactive sources at different soil depths and radii were investigated using the model shown in Fig. 2, considering the effects of the secondary scattered photons.

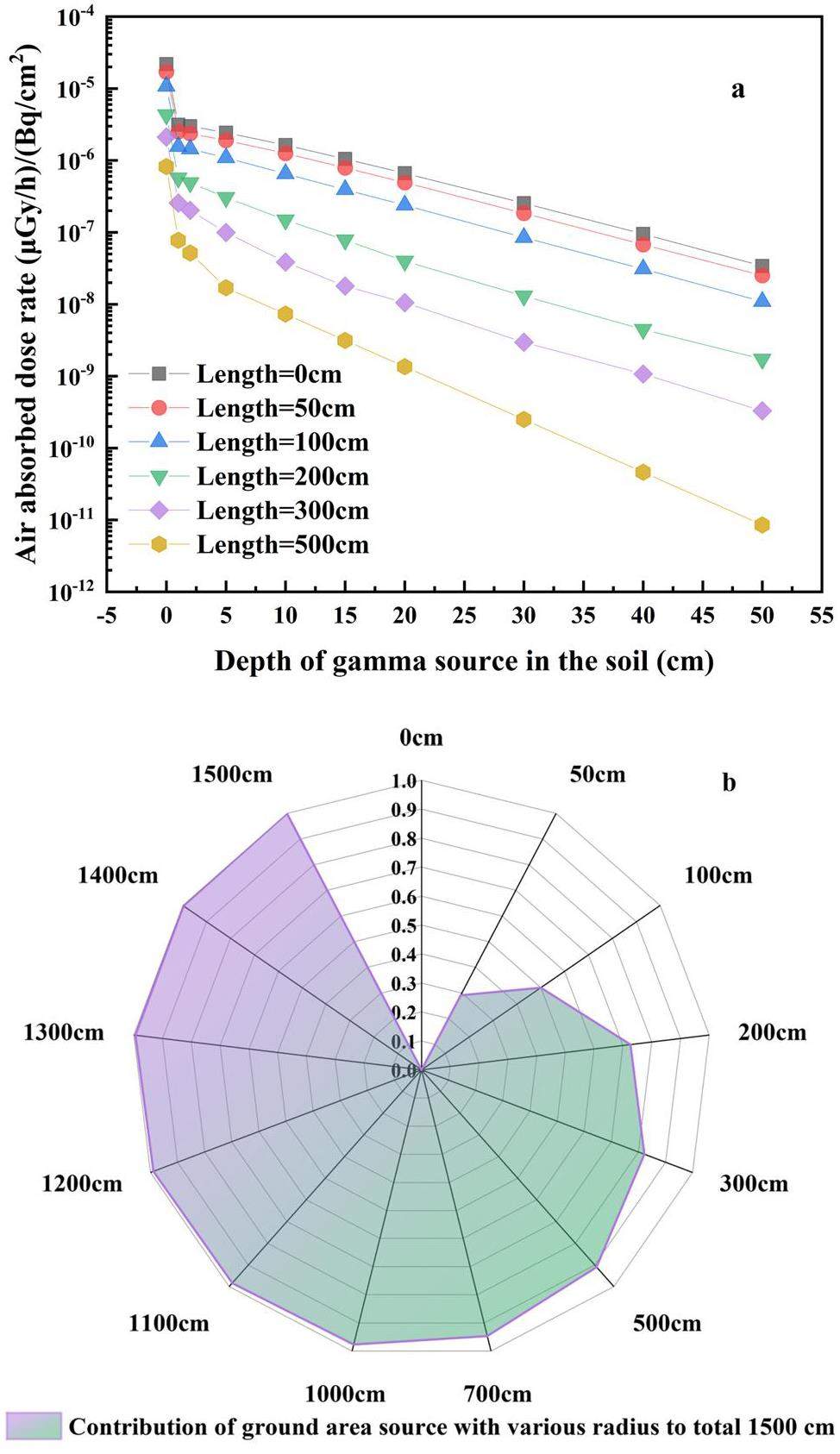

For 187W, the air-absorbed dose rate shown in Fig. 6(a) rapidly decreased with soil depth and radius. For the source directly below the collection region (radius of 0 cm), the air-absorbed dose rates decreased by two or three orders of magnitude when 187W migrated from the soil surface to 50 cm. However, the air-absorbed dose rates decreased by five orders of magnitude when 187W was located at a radius of 500 cm.

To determine the proper calculation region, air-absorbed dose rate fractions with different radii were evaluated, as shown in Fig. 6(b). The results indicate that the air-absorbed dose rates within radii of 100 cm and 500 cm contributed 50% and 91% of the dose rate within a radius of 1500 cm, respectively. Thus, the main external radiation dose rate was derived from the near zone. Therefore, it is unnecessary to build an endless model to assess the external radiation dose rate at a high computational cost.

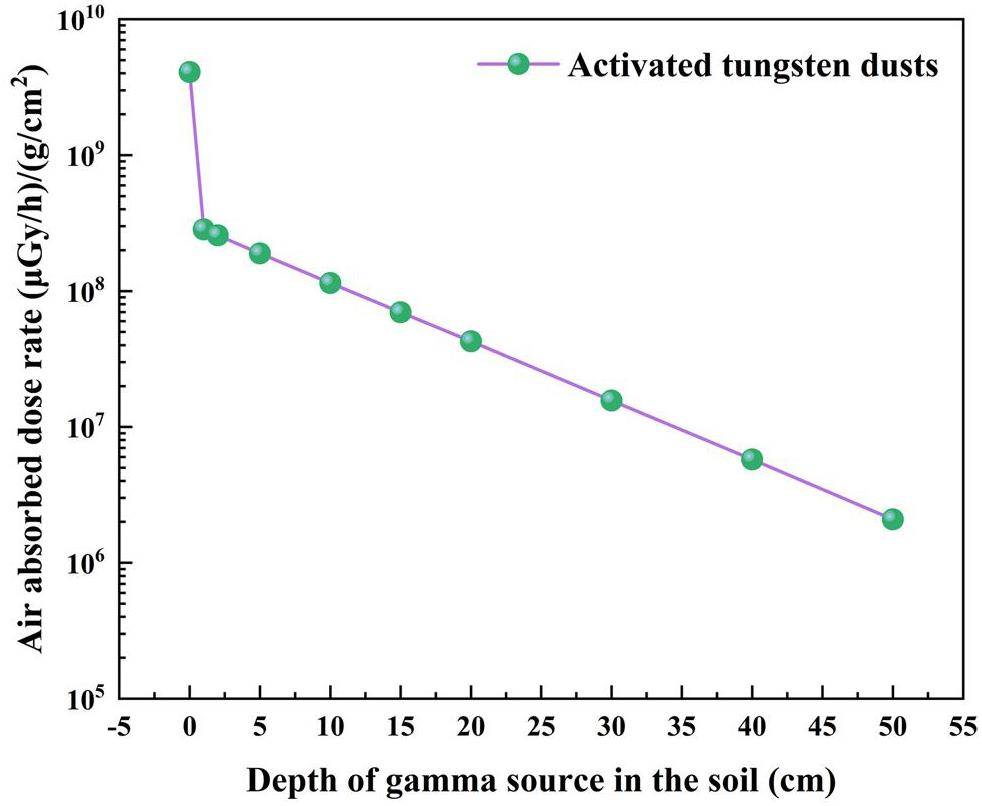

The air-absorbed dose rates were evaluated by considering all radionuclides in grams of activated tungsten dust when the radioactive source was located at different soil depths. As shown in the Fig. 7, the dose rate of the activated tungsten dust decreased significantly with soil depth owing to soil attenuation. Compared with 187W, the activated tungsten dust, including 15 radionuclides had a strong soil attenuation performance when assuming that 187W had the same specific activity as the activated tungsten dust. The reasons for this are as follows. First, the principal gamma ray energy emitted from typical radionuclides such as 185W, 181W, 186Re, 188Re, and 179Ta, in activated tungsten dust is lower than that in 187W, resulting in a weak penetration ability in soil and low air-absorbed dose rates. Second, the specific activity of the radionuclides excluding 187W, contributes considerably to the activated tungsten dust.

For the activated tungsten dust, the air-absorbed dose rate decreased by 10% and 99.9% when the dust migrated to soil depths of 1 cm and 50 cm, respectively. Considering the previous investigations on the high oxidative dissolution and fast migration rates of tungsten in soil, it is crucial to consider the attenuation factor of gamma rays emitted from activated tungsten dust in the soil, contributing to an accurate environmental dose assessment of activated tungsten dust released from fusion reactors [43, 44].

Conclusions

Tungsten-based materials are increasingly used in various tokamak devices and are considered the most promising plasma-facing materials. Radiation-dose assessment is a critical issue associated with the release of activated tungsten dust. Considering the high dissolution and rapid migration rates of tungsten in soil reported in previous studies, the soil attenuation characteristics of gamma rays emitted from activated tungsten dust were investigated. The main findings of this study are as follows. 1) The attenuation performances of eight soil samples with different elemental compositions were nearly identical. 2) Key parameters such as MAC and EABF were determined for the emerging activated tungsten dust for the first time. The mean MAC values of the eight soil samples ranged from 0.352cm2/g to 0.122cm2/g between 50 keV and 200 keV, and from 0.122cm2/g to 0.044cm2/g between 0.2 MeV and 2 MeV. The MAC values of 187W, with the main energies at 479.5 keV and 685.8 keV, were 0.088cm2/g and 0.076cm2/g, respectively. Among the main contributing radionuclides, the EABF values of 187W, 181W, 182Ta, and 60Co were 68.54, 14.39, 37.23, and 44.92 at the 10 MFP, respectively. 3) The air-absorbed dose rates decreased significantly as the activated tungsten migrated deeper into the soil. For instance, the dose rate decreased by 10% and 99.9% when the dust migrated to depths of 1 cm and 50 cm, respectively. 4) The air-absorbed dose rate was mainly influenced by nearby zones. For instance, the dose rates within radii of 100 cm and 500 cm contributed 50% and 91% of the dose rate within a radius of 1500 cm, respectively. Therefore, for realistic site assessments, the external dose rate should be assessed based on the vertical distribution characteristics of activated tungsten in the soil.

Predicting the performance of tungsten in a fusion environment: A literature review

. Mater. Sci. Technol. 33, 388-399 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1080/02670836.2016.1185260Soft X-ray tomographic reconstruction of JET ILW plasmas with tungsten impurity and different spectral response of detectors

. Fusion Eng. Des. 96, 869-872 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fusengdes.2015.04.055FEM investigation and thermo-mechanic tests of the new solid tungsten divertor tile for ASDEX Upgrade

. Fusion Eng. Des. 88, 1789-1792 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fusengdes.2013.04.048The WEST project: Current status of the ITER-like tungsten divertor

. Fusion Eng. Des. 89, 1048-1053 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fusengdes.2014.01.050Tungsten control in type-I ELMy H-mode plasmas on EAST

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 95 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00929-4Analysis of radiation conditions of DNFM ITER diagnostic tool

. Phys. Atom. Nuclei. 85, 1271-1277 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1134/S106377882207016XActivation analysis of structural materials irradiated by fusion and fission neutrons

. J. Nucl. Mater. 307, 1031-1036 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3115(02)01306-5Identification of safety gaps for fusion demonstration reactors

. Nat. Energy 1, 16154 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nenergy.2016.154Materials-related issues in the safety and licensing of nuclear fusion facilities

. Nucl. Fusion 57,Explosion characteristics and combustion mechanism of hydrogen/tungsten dust hybrid mixtures

. Fuel 332,Modeling of small tungsten dust grains in EAST tokamak using the NDS-BOUT++

. Phys. Plasmas 28,Lessons learnt from ITER safety & licensing for DEMO and future nuclear fusion facilities

. Fusion Eng. Des. 89, 1995-2000 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fusengdes.2013.12.030Emerging activated tungsten dust: Source, environmental behaviors, and health effects

. Environ. Int. 188,Dust explosion in fusion reactors: Explosion characteristics and reaction mechanism of tungsten micro-powder

. Combust. Flame 248,Evaluation of the effect of media velocity on filter efficiency and most penetrating particle size of nuclear grade high-efficiency particulate air filters

. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 5, 713-720 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1080/15459620802383934Performance assessment of HEPA filter to reduce internal dose against radioactive aerosol in nuclear decommissioning

. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 55, 1830-1837 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.net.2023.01.016Preliminary comparison of wet bypass accident consequences between ITER and a helium-cooled fusion power plant

. Fusion Sci. Technol. 74, 238-245 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1080/15361055.2018.1461966Safety and environment studies for a European DEMO design concept

. Fusion Eng. Des. 146, 111-114 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fusengdes.2018.11.049Consequence calculations for PPCS bounding accidents

. Fusion Eng. Des. 79, 1205-1209 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fusengdes.2005.08.003Preliminary analysis of public dose from CFETR gaseous tritium release

. Fusion Eng. Des. 91, 25-29 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fusengdes.2014.12.007Predictive atmospheric dispersion and deposition characteristics of activated tungsten dust

. Fusion Eng. Des. 198,Tungsten distribution and vertical migration in soils near a typical abandoned tungsten smelter

. J. Hazard. Mater. 429,Tungsten contamination, behavior and remediation in complex environmental settings

. Environ. Int. 181,Characterization of tungsten distribution in tungsten-rich slag and sediment via leaching experiments

. Environ. Earth Sci. 82, 52 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-022-10727-9Development of a calculation system for the estimation of decontamination effects

. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 51, 656-670 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1080/00223131.2014.886534Evaluation of photon radiation attenuation and buildup factors for energy absorption and exposure in some soils using EPICS2017 library

. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 53, 3808-3815 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.net.2021.05.030Characterization of mechanical and radiation shielding features of borosilicate glasses doped with MoO3

. Silicon 16, 1955-1965 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12633-023-02801-zA comprehensive evaluation of Mg-Ni based alloys radiation shielding features for nuclear protection applications

. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 56, 1830-1835 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.net.2023.12.040NNDC Databases, NuDat 3.0

. https://www.nndc.bnl.gov/nudat3/; 2024 [AccessedExperimental and theoretical investigations of the γ-rays shielding performance of rock samples from Najran region

. Ann. Nucl. Energy 183,Evaluation of gamma and neutron shielding capacities of tellurite glass system with Phy-X simulation software

. Physica B 634,Monte Carlo simulation of reflection effects of multi-element materials on gamma rays

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 10 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-020-00837-zGamma ray shielding characteristics and exposure buildup factor for some natural rocks using MCNP-5 code

. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 51, 1835-1841 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.net.2019.05.013Radiation shielding capability and exposure buildup factor of cerium(iv) oxide-reinforced polyester resins

. e-Polymers 23,Study of exposure buildup factors with detailed physics for cobalt-60 gamma source in water, iron, and lead using the MCNPX code

. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 133, 548 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjp/i2018-12355-8Semi-empirical relationship for the energy absorption buildup factor in some biological samples

. Nucl. Technol. Radiat. Prot. 31, 382-387 (2016). https://doi.org/10.2298/NTRP1604382SShielding effectiveness of boron-containing ores in Liaoning province of China against gamma rays and thermal neutrons

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 29, 58 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-018-0397-xPhoton energy absorption and exposure buildup factors for deep penetration in human tissues

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 30, 176 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-019-0701-4ICRP PUBLICATION 123: Assessment of Radiation Exposure of Astronauts in Space

. Annals of the ICRP. 1, 42 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icrp.2013.05.004XCOM

. https://physics.nist.gov/PhysRefData/Xcom/html/xcom1.html//. 2024 [accessedIndividual dose due to radioactivity accidental release from fusion reactor

. J. Hazard. Mater. 327, 135-143 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.12.018Assessing tungsten transport in the vadose zone: From dissolution studies to soil columns

. Chemosphere, 86, 1001-1007 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.11.036Soil tungsten contamination and health risk assessment of an abandoned tungsten mine site

. Sci. Total Environ. 852,The authors declare that they have no competing interests.