Introduction

Molten salt reactors (MSRs) are characterized by the utilization of molten salts as both a nuclear fuel and coolant. Liquid fuel design simplifies the fuel cycle and facilitates the recycling of diverse fuel compositions, including uranium, plutonium, and minor actinides. In addition, the high boiling point of molten salts enables MSRs to operate at high temperatures and near atmospheric pressure, enhancing the efficiency and safety of the reactors [1]. However, the special environment of an MSR requires harsh conditions for its structural materials [2, 3].

Molten-salt corrosion is a major challenge for MSR structural alloys. Because protective oxide films are not stable in molten fluoride salts, corrosion mainly occurs through the selective dissolution of active alloy elements such as Cr and Al [4]. Therefore, a low-Cr nickel-based alloy, UNS N10003 alloy (Ni-16 Mo-7 Cr), was developed specifically for MSR applications and showed excellent corrosion resistance and other properties [5-8]. The GH3535 alloy, the Chinese domestic version of the UNS N10003 alloy, was developed for the Thorium Molten Salt Reactor (TMSR) project [9]. The molten corrosion behavior of GH3535 alloys has been widely investigated in recent years. The influences of different factors such as alloy microstructure [10], salt impurities [11-13], dissimilar materials effects [14, 15], flowing conditions [16], irradiation effects [17-19], have been clarified.

Among the possible corrosion mechanisms, corrosion caused by fission products (FPs) is worth noting because FPs can circulate with molten fuel salt throughout the reactor primary system. A molten salt reactor experiment (MSRE) showed that tellurium, a major FPs, is particularly harmful [20]. Te can corrode the grain boundaries (GBs) of the structural alloy, leading to embrittlement and consequent intergranular cracking of the alloy [21, 22]. Te-induced intergranular cracking was observed in various components and surveillance specimens of the MSRE. Although most cracks were formed after room-temperature tensile tests, some could be observed directly after polishing [20].

With the increase in MSR-related research over the past decade, extensive efforts have been made to evaluate Te corrosion. Numerous previous studies have exposed alloys to Te vapor [23-27] or Te coatings in a sealed vacuum environment [28-32]. Such approaches frequently result in the development of telluride reaction layers on the sample surface, which significantly influence the Te corrosion depth [33-36] and the diffusion rate of Te [37-39]. However, no significant surface tellurides were observed on the surfaces of the alloy samples or components within the MSRE [20], indicating that the complex interaction between molten salt corrosion and Te corrosion was overlooked in the vacuum experiments.

As proposed by the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) [22] and confirmed by the Kurchatov Institute [40], out-of-pile corrosion experiments using fuel salts with UF4 and Te sources can reproduce Te-induced cracking without the formation of significant tellurides. The severity of this cracking is sensitive to the reduction/oxidation (redox) potential of the fuel salts, which is defined by the UF4/UF3 concentration ratio. However, handling UF4-containing molten salts requires special radiochemistry facilities and permissions, making them inaccessible to many researchers. Instead, several recent studies have conducted Te corrosion experiments in molten FLiNaK salt [41-45], but the experimental conditions and results have varied significantly.

Hu conducted corrosion tests on a GH3535 alloy in molten FLiNaK salt with the addition of Te powder in nickel crucibles and revealed that increasing the Te content from 0.1wt.% to 1wt.% greatly enhanced the intergranular corrosion depth of GH3535 alloy [44]. Hong’s research determined that the corrosion depth, as well as the reduction in yield strength and strain, of stainless steel 304 in molten FLiNaK salt was less severe when using nickel crucibles with the addition of 1wt.% Te powder compared to those with only 0.1wt.% Te powder [45]. Considering that the activity of Te [22, 46] and the redox potential of the molten salt [22, 40, 47] may significantly affect Te corrosion, some experiments have focused on these aspects. Jiang conducted Te exposure experiments in GH3535 alloy tubes using the FLiNaK salt containing Cr3Te4 as a low-activity Te source and NiF2 as the redox agent. It was revealed that the intergranular cracking was absent with only Cr3Te4 addition, but was severe when NiF2 was also present, and the reduction of NiF2 caused Ni deposition on sample surface [41, 42]. McAlpine compared the corrosion of four commercial alloys by the molten FLiNaK salt with that of Te and other simulated fission products. 4.8wt.% EuF3 was added as the redox agent to produce highly oxidized salts, NiTe as Te source and nickel crucibles to contain the salts. However, Hastelloy N did not show severe intergranular corrosion in their case, regardless of the Te content; there was no evidence of Te penetration in any of the tested alloys, and EuF3 was the major cause of corrosion [43].

Therefore, the surrogate Te corrosion experiments reported to date highlight that molten FLiNaK salt still has room for further improvement. The use of Te sources with too high or too low Te activity should be avoided, and the type and content of the redox agent, as well as the salt-containing materials, should be selected such that they do not cause significant interference. Quantifying the addition of redox agents to simulate the extent of cracking after tensile testing in fuel salts with different redox potentials is essential. In this study, graphite crucibles were chosen as the container for the molten FLiNaK salt because it is not as susceptible to reacting with Te [48] as Ni does [42].The GH3535 alloy was selected as the sample to meet the environmental requirements of the reactor for comparison with previous experimental studies. Cr3Te4 was chosen as the Te source, similar to that adopted from previous fuel salt [22, 47] and FLiNaK salt [41, 42] experiments. EuF3 was chosen as the redox agent because the equilibrium of EuF3/EuF2 is similar to that of UF4/UF3 in actual MSRs[49], and 1% and 3% EuF3 contents were selected to quantify the corrosion effect. In the present study, we investigated the effect of EuF3 content on the Te-induced corrosion and cracking of the GH3535 alloy through salt exposure tests, mechanical tests, salt chemical analyses, and alloy microstructural characterizations. The aim was to deepen our understanding of Te corrosion and to identify an improved protocol for future surrogate experiments.

Materials and Experimental Procedure

Materials

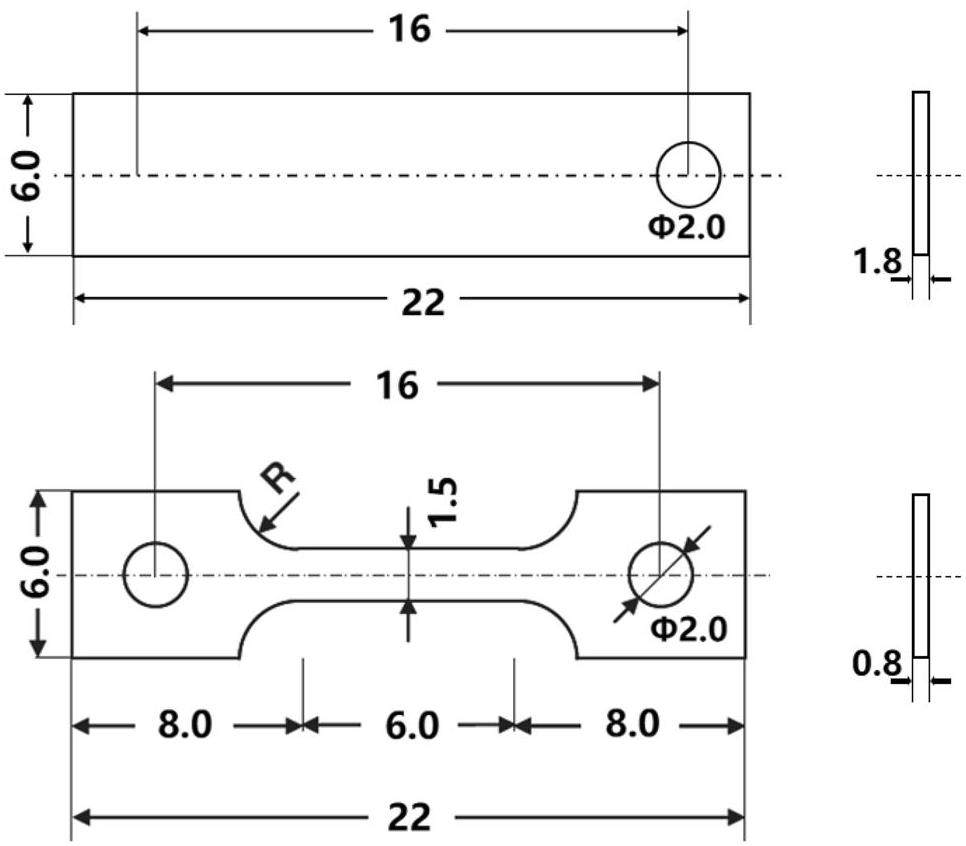

In this study, all the exposure experiments were conducted in nuclear grade graphite crucibles with an inner diameter of 20 mm.Each exposure experiment involved one tensile sample and one corrosion samples. The samples were EDM-cut from a hot-rolled GH3535 alloy plate, whose composition is shown in Table 1. The schematic diagrams of the samples are shown in Fig. 1. The corroded sample has a rectangular shape with a hole on one end for fixing, and the dog-bone shape was adapted for the tensile sample. The samples were first abraded sequentially with 400#, 800#, and 1500# SiC abrasive papers. Subsequently, they were polished with a nano alumina suspension containing particles of 0.05 μm diameter to achieve a smooth surface finish. After polishing, the samples were electro-polished in a solution consisting of 10% deionized water, 40% acetic acid (C3H8O3), and 50% sulfuric acid (H2SO4) at 0 ℃ with an applied voltage of 36 V for approximately 10 s to eliminate the surface stress. Then, they were rinsed with alcohol and deionized water. Finally, the samples were dried in an oven at 150 ℃ for 12 h to remove the adsorbed impurities.

| Elements | Ni | Mo | Cr | Fe | Mn | Si | Al | Ti | Co | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wt.% | 70.5 | 17.3 | 7.1 | 3.9 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.02 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.06 |

The FLiNaK salt (46.5LiF-11.5NaF-42KF, mol%) was prepared by mixing a totally 500g of LiF (99.9% purity), NaF (99.99% purity), and KF (99.9% purity) powders in a graphite crucible. Subsequently, the crucible containing the salts was baked at 350 ℃ for 5 hours and then melted at 650 ℃ for 2 hours in a muffle furnace inside an Ar-filled glovebox. The salt ingots were then polished and chunked upon cooling. EuF3 powder (99.9% purity) was added to the produced FLiNaK salt as the redox agent, and Cr3Te4 powder (99.9% purity) was added as the Te source.

Corrosion tests

The corrosion technique used in this study was a static salt immersion test. Corrosion tests were carried out in four groups, each group contained 35 g of FLiNaK salt with different concentrations of Cr3Te4 and EuF3 additions. Group #1: 0.1wt.% Cr3Te4 (35 mg); group #2: 0.1wt.% Cr3Te4 + 1wt.% EuF3 (0.35 g); group #3: 0.1wt.% Cr3Te4 + 3wt.% EuF3 (1.05 g); group #4: 3wt.% EuF3 (1.05 g). The aim was to elucidate the influence of EuF3 addition on Te-induced corrosion while isolating the direct corrosion effect by itself. All the operations were performed in an Ar glove box (the moisture and oxygen contents remained below 5ppm).

Firstly, the weighed FLiNaK salt chunks, Cr3Te4 powder and EuF3 powder were placed in four crucibles in the following sequence: EuF3 was added to the bottom of the crucible; next, 2/3 of the crucible was filled with the FLiNaK salt and Cr3Te4 powder, and the remaining 1/3 was filled with the FLiNaK salt. Second, the four loaded crucibles were placed into a muffle furnace and heated at 700 ℃ for 8 h to melt the salt and dissolve the powders. The salt samples before corrosion were removed from each crucible by dipping a tungsten rod. Finally, the alloys samples fixed to the crucible lids with by the GH3535 wire were placed into the molten salt and subjected to thermal exposure at 700 ℃ for 250 h. After exposure, the alloy samples were removed to cool in the glove box, and the salt samples after corrosion were dipped out using a tungsten rod, before turning off the furnace to cool the entire system.

Post corrosion tests and characterizations

The characterizations primarily encompassed the analysis of the salt, the microstructure of the alloy samples, the distribution of elements, and the mechanical properties, with a particular focus on the morphology of the cracks. The salt samples collected before and after the corrosion process underwent chemical analysis using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) and mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). ICP-MS was utilized for the analysis of Te and Eu, while ICP-OES was employed for the analysis of all other elements. A comparison of the values obtained from these analyses before and after corrosion revealed changes in the elemental contents.

The tensile samples were subjected to room temperature (RT) testing using a mechanical testing machine (Zwick Z100) at a constant strain rate of 3.5 mm/min. Owing to the small sample size, an extensometer was not used. The data from the tensile tests were plotted as stress-strain curves to assess the impact of the different corrosion conditions. Microstructural and elemental analyses of both the corroded and tensile samples were conducted using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Carl Zeiss Merlin Compact) equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS). Initially, EDS point scanning was performed at various points across the sample surface. This was followed by EDS line scanning of both the surface and cross-section of the samples, with a focus on the GBs and near-surface region. Given the difficulty in detecting Te segregation at the GBs using EDS, an electron probe microanalyzer (EPMA, SHIMADZU-1720H) was employed to ascertain the distribution of Te.

Results

Salt composition analyses before and after corrosion

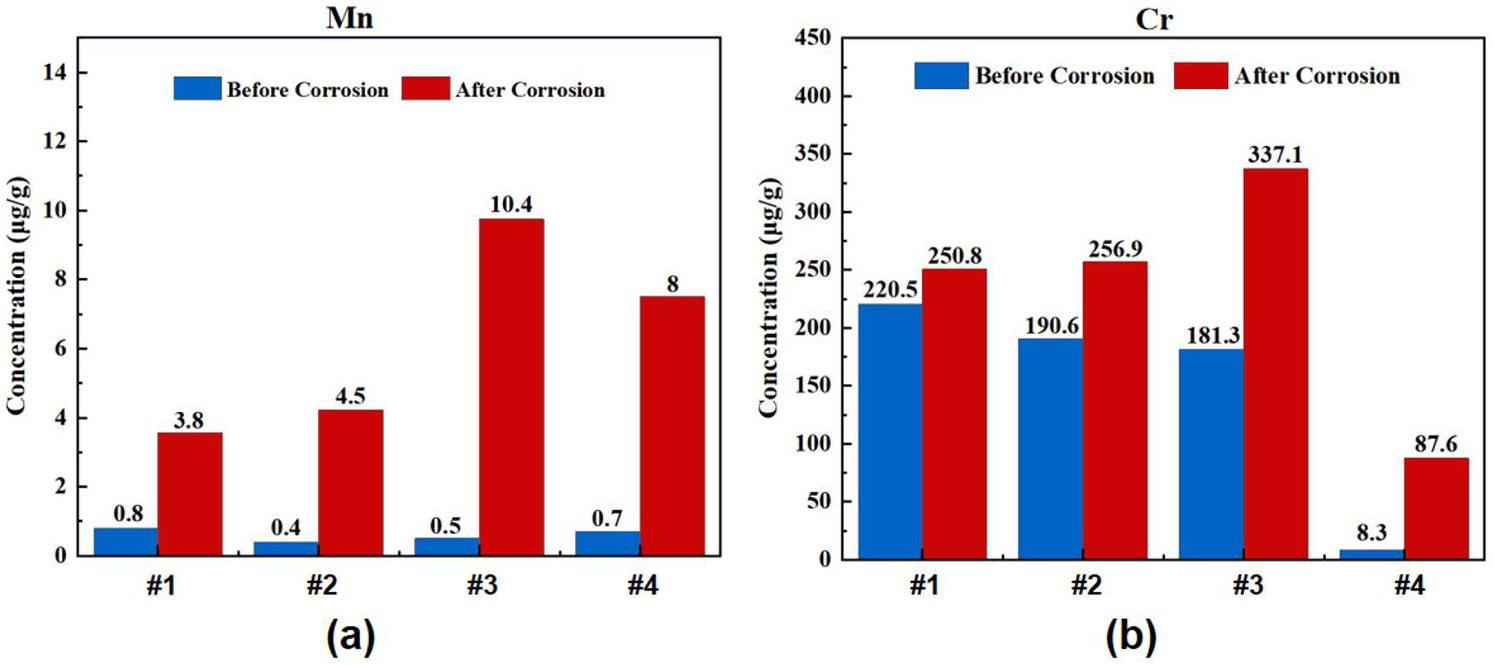

Before corrosion, the metal impurities in the salt were minimal, with Fe at a maximum of 35 ppm. After corrosion, the contents of Cr and Mn in all the salt samples increased, indicating the dissolution of the active elements in the alloy. Among them, the salt containing both Cr3Te4 and 3% EuF3 increased the most, followed by the salt containing only EuF3, and the least increase was observed in the salt containing only Cr3Te4, suggesting that the addition of Cr3Te4 and EuF3 affected corrosion. The overall trend of Fe and Ni in the post-corrosion salt showed a decrease, but with some fluctuations. Additionally, the content of Mo increased slightly in #2, #3, and #4, with the most significant increase observed in #3.

The differences between the measured and calculated Eu values were statistically significant. Before corrosion, the measured values did not exceed 20% of the calculated values, whereas after corrosion, the measured values for #2, #3, and #4 were 51%, 88%, and 16% of the calculated values, respectively. This result can be ascribed to the limited solubility of EuF3 in the molten FLiNaK salt or in the acid solution during ICP sample preparation. Notably, the measured Eu content after corrosion was higher than before corrosion, with Te-containing sample #3 showing a higher Eu content than the Te-free sample #4, although both samples had the same 3% EuF3 addition.

Before corrosion, the measured Te values are close to the calculated values. The measured Te values for the 0%, 1% and 3% EuF3 salts were 90% 99.5% and 99.7% of the calculated values, respectively. After corrosion, the measured Te values were 109%, 104%, and 88% of the calculated values, respectively. Overall, the change in Te before and after corrosion was not significant, and it is uncertain whether the differences in the measured values were due to test errors or the real changes in Te form and distribution.

Microstructure and composition characterization of corroded samples

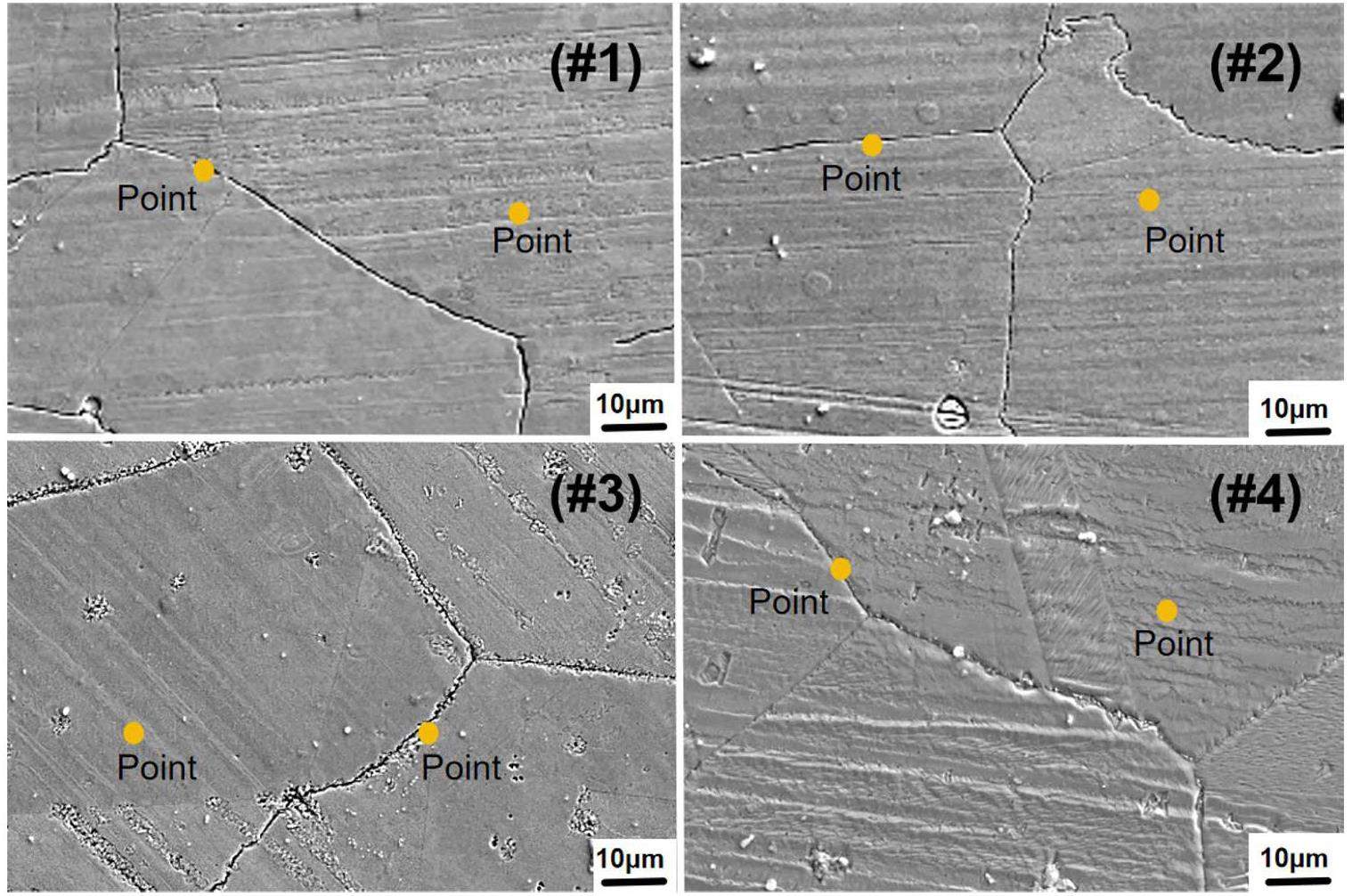

The surface morphologies of the corroded samples under various experimental conditions are depicted in Fig 3. It is evident that all the samples exhibited GB corrosion; the overall difference between the samples was not obvious, and no tellurides were observed on the sample surface.

EDS point analysis was performed at the GBs and inside the grains. As shown in Table 3, compared to the original content (7.1wt.%), all the surface experienced a depletion in the element Cr. Cr depletion at the GBs was more severe than that inside the grains. Adding more EuF3 to the salt caused an increase in Cr depletion, both inside the grains and at the GBs. When both EuF3 and Cr3Te4 were present in the salt, the loss of Cr at the GBs increased faster than that inside the grains with the increasing EuF3 addition. However, without Cr3Te4, the Cr depletions at the GBs and inside the grains was similar (sample #4). This indicates that the synergistic effect of EuF3 and Cr3Te4 enhances the GB corrosion.

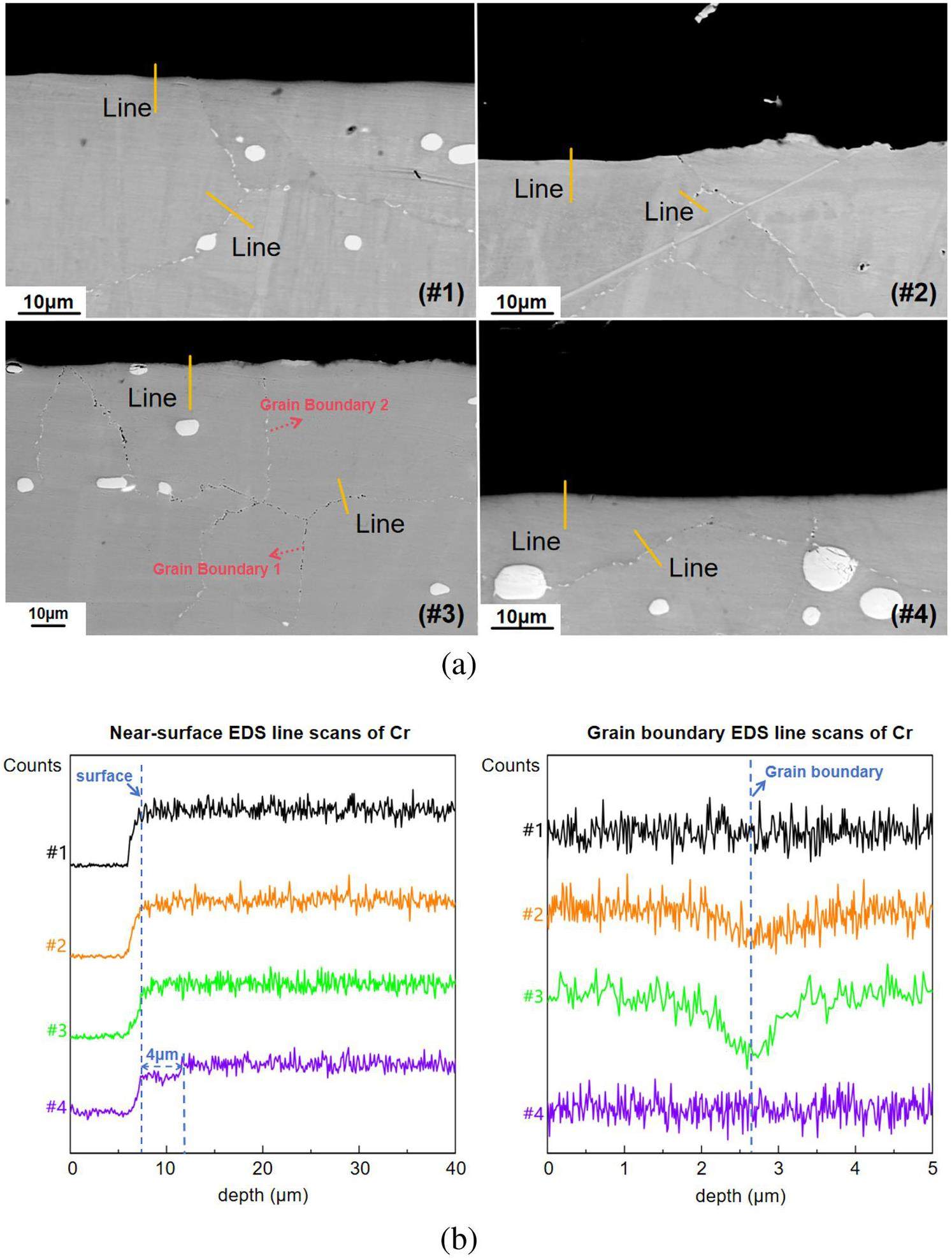

Cross-sectional analyses of the samples were performed to ascertain the depth of corrosion, and the SEM cross-sectional images of the samples under varying corrosion conditions are shown in Fig. 4(a). Overall, the grains underneath the surfaces of all tested samples remained free of corrosion defects. As is shown in Fig. 4(b), no obvious intragranular Cr depletion was found except in samples #4 that corroded in solely EuF3 containing salt, which showed a Cr depletion of 4 μm. On the contrary, grain boundary corrosion was obvious in samples that corroded in salts containing both Cr3Te4 and EuF3. After corrosion in the salt containing Cr3Te4 and 1% EuF3, a small quantity of pores could be seen on grain boundaries in sample #2 up to more than 10 μm depth. But when the EuF3 increased to 3%, sample #3 corroded in Te-containing salt showed extensive corrosion pores on the grain boundaries up to more 100 μm depth. It’s worth noting that not all grain boundaries in sample #3 suffered severe corrosion, typical corroded and un-corroded boundaries are marked with 1 and 2 in Fig. 4(a) respectively. EDS scans across grain boundaries of underneath the surface of each sample confirmed that Cr was slightly depleted in sample #2 and significantly depleted in sample #3, due to the co-existence of EuF3 and Cr3Te4 in the salt; this observation was consistent with the surface analysis results.

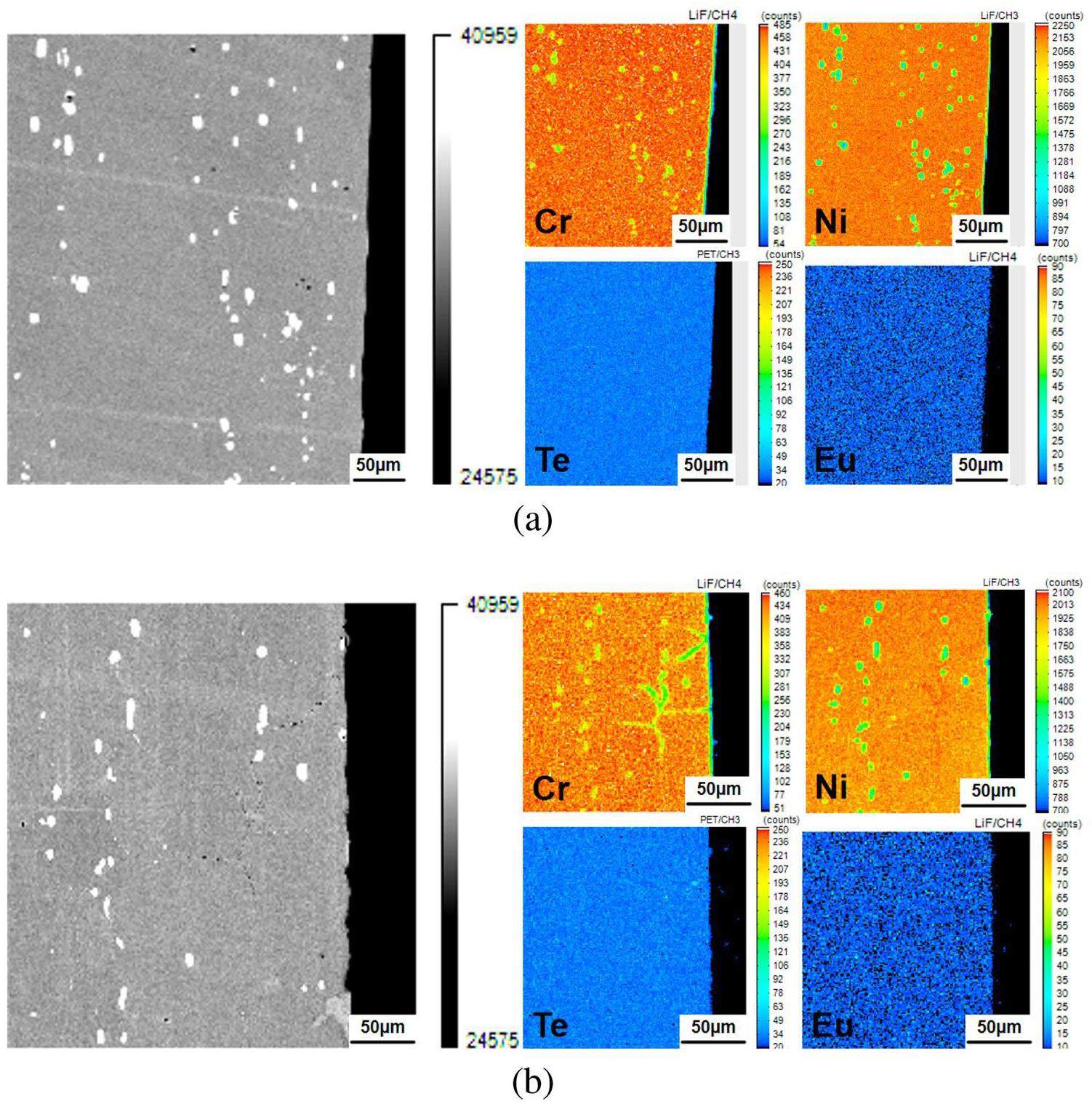

Because EDS does not have sufficient detection ability for trace elements, EPMA was used to further analyze the elemental distribution of the samples after corrosion in salts containing Cr3Te4+1%EuF3 and Cr3Te4+3%EuF3, as shown in Figs. 5(a) and (b). This again confirms that when the addition of EuF3 in the molten salt was increased to 3%, the depth and extent of Cr depletion along the GBs of the sample increased significantly. However, none of the samples exhibited Te enrichment in the corrosion-affected regions, indicating that the Te activity in the salts was low.

Tensile tests and microstructure characterization of fractured samples

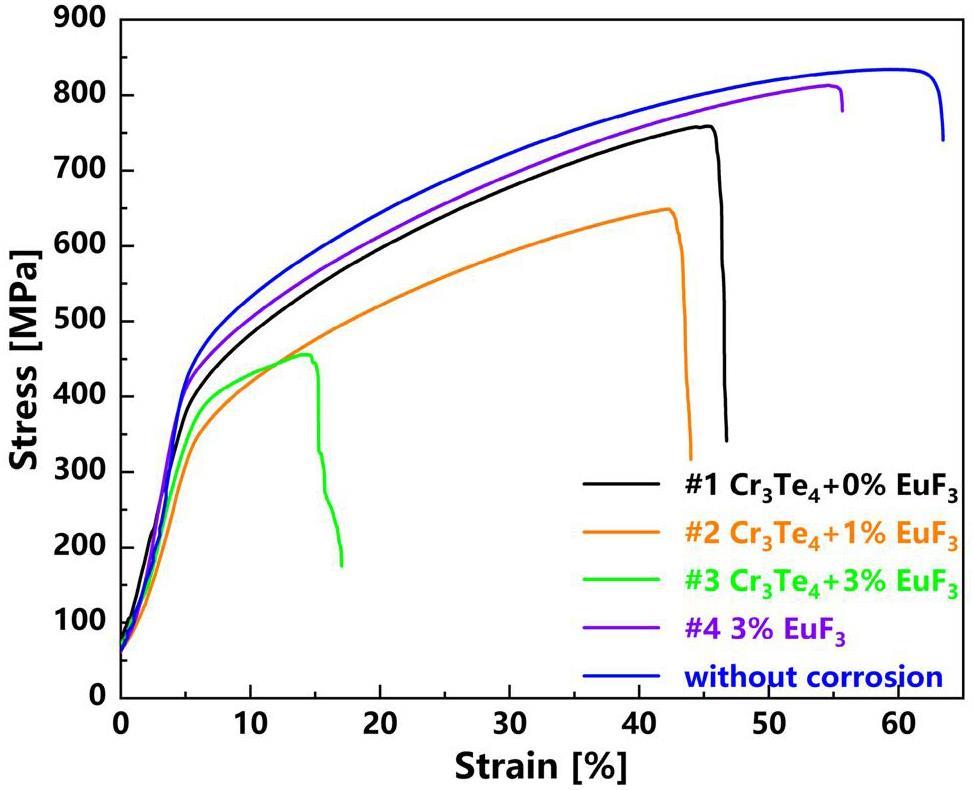

After corrosion, the tensile samples under the four experimental conditions were tested at RT using a universal material-testing machine. The stress-strain curves of the samples are shown in Fig. 6, and the strength and elongation data are listed in Table 4. The sample size was small, and thus, an extensometer could not be used. Therefore, the curve of the elastic stage in Fig. 6 is not accurate; the curve after the yielding stage provides detailed information.

As shown in Fig. 6 and Table 4, the yield strengths of both the corroded and uncorroded samples were similar, but the ultimate strengths and elongations varied significantly. The uncorroded samples had the greatest ultimate strength and elongation of 834.3 MPa and 63.4% respectively. The sample corroded in solely EuF3-containing salt follow, with ultimate strength and elongation of 813 MPa and 55.7% respectively, while adding Cr3Te4 to the salt caused reductions in both properties. It worth noting that among the samples corroded in Cr3Te4-containing salts, the extent of reduction in mechanical properties increased with the increasing EuF3 contents. The sample corroded in the salt containing Cr3Te4+3%EuF3 had the lowest ultimate strength and elongation of 456.2 MPa and 17% respectively.

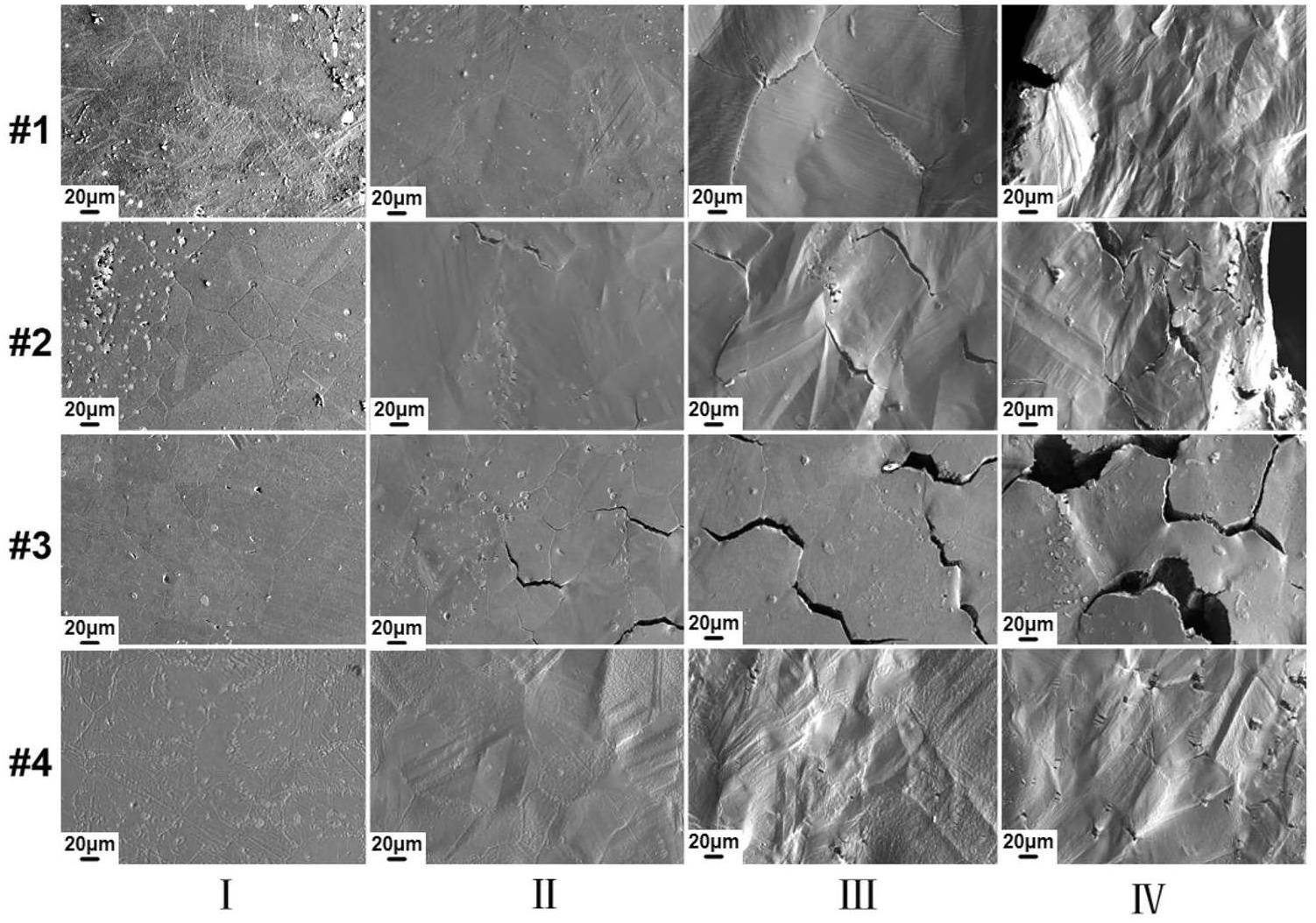

The surface morphologies of fractured samples at different locations from the holding end to the fractured end were observed by SEM. According to the sample geometry, the stresses borne during tensile test increased from locations I to IV. As shown in Fig. 7, all tested samples show no cracks at location I, but show clear surface cracks at location IV, indicating that the cracking was sensitive to stresses. Sample #4 corroded in the salt with solely EuF3 addition exhibited the least severe cracking, only some short cracks on carbides were found even near the fracture and no intergranular crack was seen. On the contrary, intergranular cracks existed in all the samples corroded in Cr3Te4-containing salts, but the size, density and occurring location of these cracks varied. While only few intergranular cracks were seen at locations III and IV in Sample #1, more intergranular cracks existed even at location II in sample #2 and #3. It is clear that for samples corroded in Cr3Te4-containing salts, the severity of cracking was increased with the increasing EuF3 additions. The order of the increasing intergranular cracking of the fractured samples was consistent with that of the decreasing tensile properties.

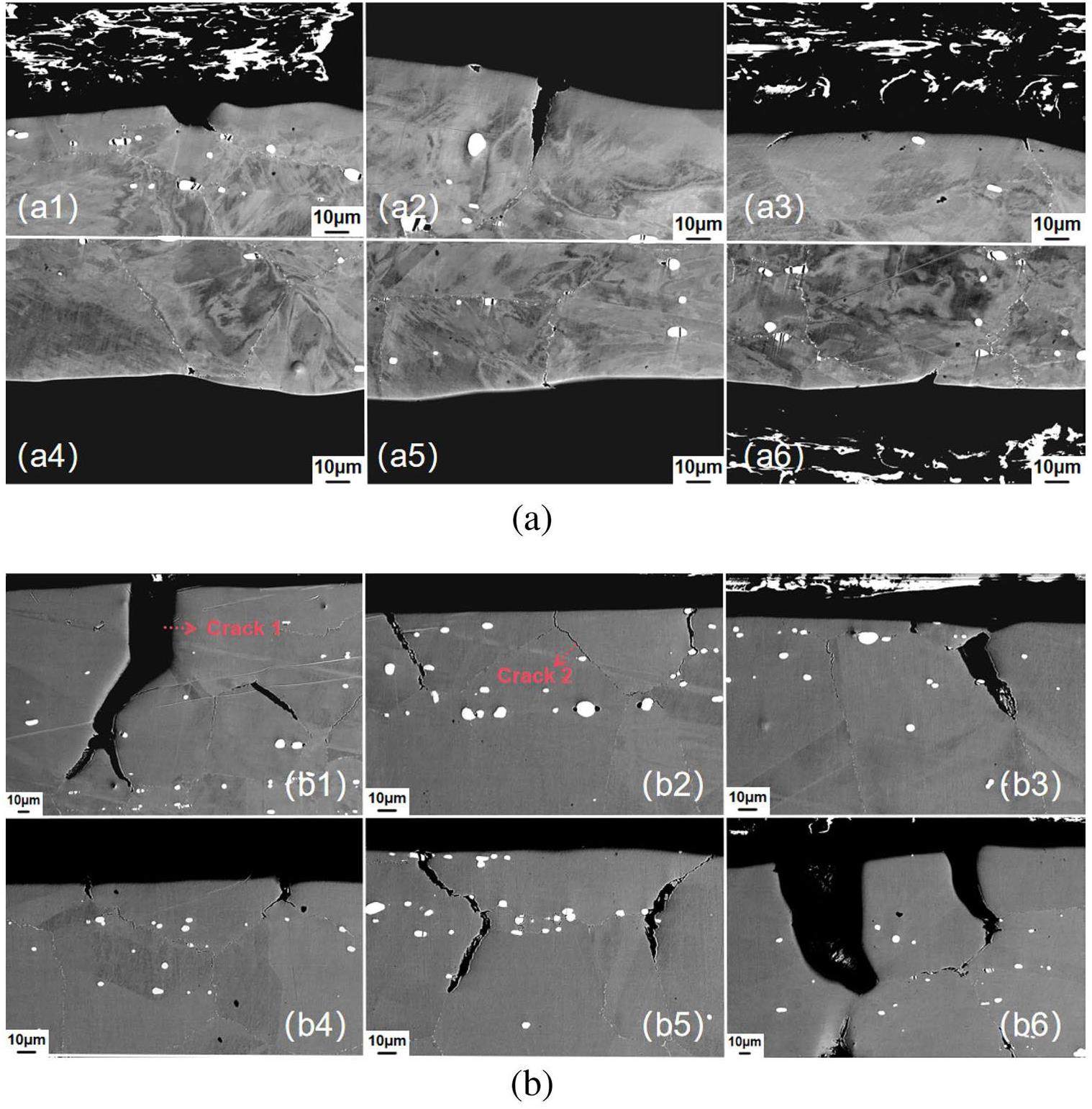

The cross-sectional microstructures of the fractured samples were also observed using SEM. Samples #1 and #4 did not exhibit cracks; therefore, these images are not presented. Samples #2 and #3 exhibited increased cracking, as shown in Fig. 8(a) and (b), respectively.

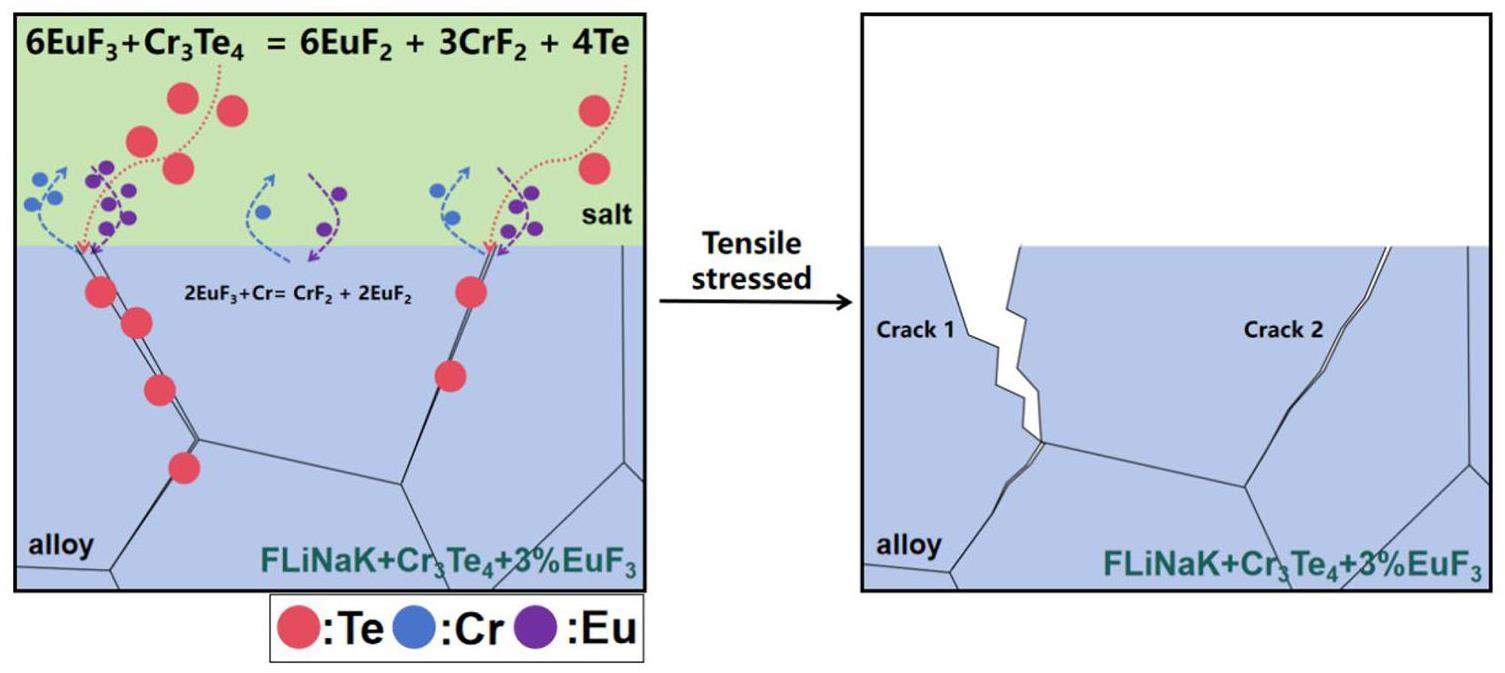

For the sample corroded in the salt containing Cr3Te4 and 1%EuF3, 16 cracks were found within the 5mm observation range. Only one crack had a depth of 32 μm (Fig 8(a)), all other cracks were shorter than 10 μm. When the addition of EuF3 was increased to 3%, both the density and depth of the cracks increased significantly. Further, 27 cracks were found in the 5mm observation range, and the average depth was 57.1μm. The standard deviation of cracks depth was large, with a maximum of 164μm and a minimum of 20 μm, and the depths of only nine cracks was larger than the average value. In addition to the depth, the widths of the cracks also varied. Two typical types of cracks were observed in sample #3: one had a widely opened crack mouth, such as crack 1 in Fig. 8(b), and the other had no such as crack 2 in Fig. 8(b). A possible mechanism for their formation is discussed below.

Discussion

Analysis of the data presented in Table 2 and Fig. 2 reveals that the presence of Eu and Te significantly influences the corrosion process, with EuF3 exhibiting a particularly pronounced effect on Te-induced corrosion. However, the corrosion mechanism requires further investigation. Additionally, Table 3 and Fig 3 demonstrate that the simultaneous presence of EuF3 and Cr3Te4 affects the depletion of Cr at the GBs, which contrasts with the effects observed when EuF3 or Cr3Te4 are added individually.

| Elements | Mn | Cr | Fe | Mo | Ni | Te | Eu | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal concentration of Cr, Te, and Eu added (calculated value) | ||||||||

| 0.1wt.% |

/ | 234 | / | / | / | 766 | wt.%: 7270 | wt.%: 21810 |

| Concentration before corrosion(measured value) | ||||||||

| #1 a | 0.8 | 220.5 | 35.1 | 5.4 | 16.3 | 693.0 | 56.5 | |

| #2 b | 0.4 | 190.6 | 19.5 | / | 2.3 | 762.0 | 787.5 | |

| #3 c | 0.5 | 181.3 | 27.2 | 0.6 | 16.0 | 763.4 | 4023.6 | |

| #4 d | 0.7 | 8.3 | 30.9 | / | 14.7 | 7.2 | 1940.2 | |

| Concentration after corrosion(measured value) | ||||||||

| #1 a | 3.8 | 250.8 | 22.7 | 5.0 | 4.4 | 836.3 | 43.7 | |

| #2 b | 4.5 | 256.9 | 11.5 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 800.1 | 3708.7 | |

| #3 c | 10.4 | 337.1 | 19.2 | 16.7 | / | 679.4 | 19290.8 | |

| #4 d | 8.0 | 87.6 | 16.9 | 6.6 | 20.1 | / | 3558.1 | |

| Elements | Cr | Fe | Mo | Ni |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inside the grain | ||||

| #1 | 4.2 | 5.5 | 16.4 | 73.9 |

| #2 | 4.1 | 5.2 | 16.9 | 73.8 |

| #3 | 3.5 | 5.0 | 17.0 | 74.5 |

| #4 | 3.5 | 8.9 | 14.9 | 72.7 |

| GB | ||||

| #1 | 3.9 | 6.3 | 14.3 | 75.5 |

| #2 | 3.2 | 5.9 | 15.9 | 75.0 |

| #3 | 1.9 | 5.3 | 24.1 | 68.7 |

| #4 | 3.2 | 9.3 | 14.4 | 73.1 |

| Difference in Cr content with inside the grain and GB | ||||

| #1: 0.3 | #2: 1.3 | #3: 1.6 | #4: 0.3 | |

Figure 4(a) to 5(b) displaying the cross-sectional analyses of the samples, indicate that the coexistence of EuF3 and Cr3Te4 leads to GB corrosion, affecting Cr depletion at these boundaries. In contrast, the samples with only EuF3 showed only minor Cr depletion near the surface. Notably, no Te enrichment was detected using EPMA, suggesting that these effects may occur at a very low Te activity. The tensile test results and these observations (Fig. 6 to 8(b) and Table 4) collectively indicate that the mechanical properties and cracking after tensile testing are significantly affected by Cr3Te4, EuF3, and their coexistence. These varying effects highlight the need to explore the underlying mechanisms.

| Sample | Yield strength (MPa) | Ultimate strength (MPa) | Elongation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | 392.8 | 759.0 | 50.4 |

| #2 | 348.8 | 648.8 | 44.0 |

| #3 | 362.5 | 456.2 | 17.0 |

| #4 | 391.9 | 813.0 | 55.7 |

| Without corrosion | 391.2 | 834.3 | 63.4 |

In this section, we discuss the mechanisms observed in throughout the corrosion experiments. This includes the direct corrosion caused by the addition of EuF3, the enhanced intergranular corrosion and cracking due to the synergistic effects of EuF3 and Cr3Te4, and a comparison of these findings with those of previous studies on Te corrosion.

Direct corrosion induced by EuF3

When EuF3 was present in the molten FLiNaK salt, equilibrium between EuF3/EuF2 was established, and the balance concentration ratio without reacting with other elements was measured as approximately 2 at 700 ℃ [49]. This ratio may be highly oxidizing because an EuF3/EuF2 ratio lower than 0.05 is required to avoid the corrosion of Cr [49]. Therefore, EuF3 is typically used as an oxidant for accelerating corrosion in many of molten fluorides corrosion tests [43, 50, 51].

The results presented in the previous section demonstrate that the contents of dissolved Cr in the salt (Table 2) and depleted Cr on the sample surface (Table 3) after corrosion both increased with the increasing EuF3 content. This result can be ascribed to the oxidative nature of EuF3; its reaction with Cr in the alloy is expressed by the following equation:

Synergistic effect of EuF3 and Cr3Te4 on corrosion and cracking

According to the early research by ORNL [22], it is the zero valence Te0 that diffuses into to the alloy, causes the embrittlement of the alloy GBs and results in the intergranular cracking. Therefore, they proposed to control Te0 activity by adjusting the UF4/UF3 concentration ratio, through the “complexing” reaction of Te with chromium to retain it in the salt. The reaction can be expressed as Eq. (2) which implies that increasing the concentration of UF4 in the salt increases the content of Te0 released. Consequently, the redox potential of the salt has a strong influence on Te corrosion; if the UF4/UF3 concentration ratio in the fuel salt is kept sufficiently low, Te-induced cracking is prevented [22].

Te segregation on the GB is harmful because it not only directly embrittles the GB [20], but also causes GB expansion, which reduces the diffusion barrier of other active elements along the GB. The accelerated outward diffusion of the active element causes void formation that further damages the GB [41]. Therefore, EuF3 in the salt induced the most Cr dissolution according to Eq. (1), whereas Cr depletion was much faster from the Te-segregated GBs in sample #3. This synergistic effect resulted in the most severe GB corrosion and the subsequent intergranular cracking in sample #3, hence greatly deteriorated its mechanical properties. To quantify the severity of Te-induced cracking, the density and length of cracks were counted from locations III and IV of cross-sectional samples, and the K values [20, 40] defined as the number of cracks per centimeter of alloy multiplied by the average depth of cracks (unit: pc × μm/cm) were calculated as follows:

Assessment of the present surrogate experiment

The major test conditions and results of the present experiment, as well as other typical Te vapor, Te-containing fuel salt and FLiNaK salt corrosion experiments for UNS N10003 alloy (alloy N) at 700 ℃, are summarized for comparison in Table 5.

| Experimental environment | Time (h) | Corrosion depth (μm) | Cracking depth (μm) | Cracking density (cm-1) | K (depth×density) (pc ×μm/cm) | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Te powder a | 3000 | 139± 9 | 135 | 85 | 11475 | [27] |

| (LiF-BeF2-ThF4-UF4) +CrTe1.266 (UIV/III=60) b | 250 | / | 13 | 5 | 65 | [22] |

| (LiF-BeF2-ThF4-UF4) +CrTe1.266 (UIV/III=85) c | 250 | / | 10.7 | 68 | 728 | [22] |

| (LiF-BeF2-ThF4-UF4) +Cr3Te4 (UIV/III=90) d | 500 | / | 74.8 | 122 | 9126 | [22] |

| FLiNaK +0.1wt%Te powder e | 1000 | GB: 2 | 2 | / | / | [44] |

| FLiNaK +1wt.%Te powder f | 1000 | Grain: 25 |

25 |

/ | / | [44] |

| FLiNaK+0.1wt.%Cr3Te4 g | 1000 | Grain: 8 | No cracking | / | / | [42] |

| FLiNaK +0.1wt.%Cr3Te4+NiF2 h | 1000 | Grain: 15 |

210 | / | / | [42] |

| FLiNaK+0.14wt.%NiTe +4.8 wt.%EuF3 i | 150 | Grain: 23 |

/ | / | / | [43] |

| FLiNaK+0.1wt.%Cr3Te4 +1wt.%EuF3 j | 250 | >10 | Max: 32 |

32 | 195 | This work |

| FLiNaK+0.1wt.%Cr3Te4 +3wt.%EuF3 k | 250 | Grain: 4 |

Max: 164 |

54 | 3083 | This work |

When alloy N was corroded with 1.0 mg/cm2 Te power sealed in a vacuum ampoule without molten salt, large amounts of surface tellurides formed, which affected the inward diffusion of Te and resulted in a GB corrosion depth of 139 μm after 3000 h [27]. In contrast, alloy N corroded in Te-containing salts did not show clear evidence of surface tellurides [22, 42-44] and often showed deeper depths even in a much shorter time [42, 44]. Therefore, the Te vapor test may underestimate the extent of Te-induced corrosion in MSRs.

In a salt corrosion test using Te powder as the Te source [44], cracks were formed without tensile stress, indicating that severe Te-induced corrosion had occurred. This result is obtained possibly because the direct introduction of Te0 avoids the necessity of reactions Eq. 2 and 3 to release Te0 from Te compounds, but may lead to high Te activity and Te release rate, which exceed those observed in real MSRs.

When alloy N was corroded in Cr3Te4 containing salt with and without NiF2 for 1000 h [42], the trend was similar to that observed in the present study; however, the extent of cracking was greater. Without NiF2, no intergranular cracking occurred even after tensile test, whilst and intergranular cracks deeper than 100 μm formed before tensile test and cracks up to 210 μm formed after tensile with NiF2 addition. Although Te sources of the same type and concentration were used, the different redox couples contributed to the observed differences. According to the potential chart [49], the equilibrium of NiF2/Ni resulted in a higher oxidizing potential than EuF3/EuF2 or UF4/UF3 in a similar concentration range; hence, the Te activity in the salt was higher even though the same Cr3Te4 was used. In addition, reduced Ni was deposited as a corrosion product on the alloy surface, which may have affected the corrosion behavior of the alloy.

For the salt corrosion test with 4.8wt.% EuF3 but with NiTe as Te source [43], the intragranular Cr depletion depth was 23 μm after 150 h, which was much higher than that of the present study (4 μm after 250 h) probably due to the higher EuF3 concentration. However, no GB depletion was observed in this case, which may be ascribed to the lower Te activity induced by the NiTe source and Ni crucible [46]. The probability of such a low Te activity inducing intergranular cracking is not clear because tensile tests were not performed in this study.

In the present study, the Te activity was maintained sufficiently low such that the Te concentration in the GB of the tested alloy N was below the EPMA detection limit but sufficiently high to cause intergranular cracking after the tensile tests. When 1% EuF3 was added, the cracking behavior of alloy N was similar to that of the reducing fuel salt, and the K value was equivalent to that of the fuel salt with UF4/UF3 ratios of between 60 and 85. When 3% EuF3 is added, the cracking behavior and K value resemble those of an oxidizing fuel salt. This suggests that the present experimental design may serve as a surrogate approach for avoiding the use of radioactive hazardous fuel salts in future Te corrosion studies.

Conclusion

(1) EuF3 induces intergranular corrosion of the GH3535 alloy in Cr3Te4 containing salt. The corrosion depth increases with the increasing EuF3 concentration up to more than 100 μm in that salt. On the contrary, EuF3 induces uniform corrosion up to 4 μm in salt without Cr3Te4.

(2) Corrosion deteriorates the mechanical properties of the alloys. The ultimate tensile stress decreased from 834 MPa to 456MPa, and the elongation decreased from 63.4% to 17% in the most corroded alloy.

(3) Cr3Te4 induced intergranular cracking in the alloy. The severity of cracking increases with the increasing EuF3 concentration in Cr3Te4 containing salt, with a maximum crack depth of 164 μm.

(4) The synergistic effect between EuF3 and Cr3Te4 resulted in greater GB Te segregation and Cr depletion, which deteriorated the GB strength and caused severer intergranular cracking.

Research on the inherent safety and related key issues of the new concept of molten salt reactor

. Atom. Energy Sci. Technol. 43, 64-75 (2009). https://doi.org/10.7538/yzk.2009.43.suppl.0064Review on synergistic damage effect of irradiation and corrosion on reactor structural alloys

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 57 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01415-3Influence of He ion irradiation on the microstructure and hardness of Ni-TiCNP composites

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 32, 121 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-021-00961-4Corrosion in the molten fluoride and chloride salts and materials development for nuclear applications

, Prog. Mater. Sci. 97, 448-487 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmatsci.2018.05.003The high-temperature corrosion of Hastelloy N alloy (UNS N10003) in molten fluoride salts analysed by STXM, XAS, XRD, SEM, EPMA, TEM/EDS

, Corros. Sci. 106, 249-259 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2016.02.010The tensile behavior of GH3535 superalloy at elevated temperature

. Mater. Chem. Phys. 182, 22-31 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2016.07.001Effect of long-term thermal exposure on microstructure and stress rupture properties of GH3535 superalloy

. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 31, 269-279 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2014.07.021Compatibility studies of potential molten-salt breeder reactor materials in molten fluoride salts. [Inconel 601, Cr and Nb modifications of Hastelloy N]. ORNL/TM-5783

. 1-19 (1977).https://doi.org/10.2172/7257097R&D of structural alloy for molten salt reactor in China

.Effect of surface decarburization on corrosion behavior of GH3535 alloy in molten fluoride salts

. Acta Metall. Sin. 32, 401-412 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40195-018-0814-5Non-uniform corrosion of UNS N10003 alloy induced by trace SO42- in molten FLiNaK salt

. Corros. Sci. 192,Dissolved valence state of iron fluorides and their effect on Ni-based alloy in FLiNaK salt

. Corros. Sci. 192,Corrosion behavior of UNS N10003 alloy in molten LiF-BeF2-ZrF4 with phosphide impurity

. Corros. Sci. 226,Influence of graphite-alloy interactions on corrosion of Ni-Mo-Cr alloy in molten fluorides

. J. Nucl. Mater. 503, 116-123 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2018.03.001Effect of graphite particles in molten LiF-NaF-KF eutectic salt on corrosion behaviour of GH3535 alloy

. Corros. Sci. 168,Corrosion behavior of GH3535 alloy in molten LiF–BeF2 salt

. Corros. Sci. 199,Effect of irradiation damage defects on the impurity containing molten salt corrosion behavior in GH3535 alloy

. Corros. Sci. 223,High-temperature corrosion of helium ion-irradiated Ni-based alloy in fluoride molten salt

, Corros. Sci. 91, 1-6 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2014.11.013Irradiation accelerated fluoride molten salt corrosion of nickel-based UNS N10003 alloy revealed by X-ray absorption fine structure

, Corros. Sci. 165,Intergranular Cracking of INOR-8 in the MSRE. ORNL-4829

,The development status of Molten-Salt breeder Reactor. ORNL-4812

,Status of tellurium–hastelloy N studies in molten fluoride salts. ORNL-TM-6002

,Grain boundary engineering for control of tellurium diffusion in GH3535 alloy

. J. Nucl. Mater. 497, 76-83 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2017.10.052Influence of lanthanum element on tellurium induced embrittlement of Ni-16Mo-7Cr alloy

. Corros. Sci. 203,On the origin of tellurium corrosion resistance of hot-rolled GH3535 alloy

. Corros. Sci. 170,Influence of grain size on tellurium corrosion behaviors of GH3535 alloy

. Corros. Sci. 148, 110-122 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2018.12.007Effect of thermal exposure time on tellurium-induced embrittlement of Ni-16Mo-7Cr-4Fe alloy

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 28, 178 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-017-0330-8EPMA and TEM characterization of intergranular tellurium corrosion of Ni-16Mo-7Cr-4Fe superalloy

. Corros. Sci. 97, 1-6 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2015.04.017Effect of yttrium on intergranular embrittlement behavior of GH3535 alloy induced by tellurium

. Corros. Sci. 216,Effect of Nb contents on the surface tellurization and intergranular cracking behaviors of Ni-Nb-C alloys

. J. Alloy. Compd. 961,Effect of Al addition on intergranular embrittlement behavior of GH3535 alloy induced by fission product Te

. Corros. Sci. 207,Effect of temperature on diffusion behavior of Te into nickel

. J. Nucl. Mater. 441, 372-379 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2013.06.025Effects of Te on intergranular embrittlement of a Ni-16Mo-7Cr alloy

. J. Nucl. Mater. 461, 122-128 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2015.01.049Intergranular diffusion and embrittlement of a Ni-16Mo-7Cr alloy in Te vapor environment

. J. Nucl. Mater. 467, 341-348 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2015.09.053Local structure study of tellurium corrosion of nickel alloy by X-ray absorption spectroscopy

. Corros. Sci. 108, 169-172 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.corsci.2016.03.006Effect of Cr contents on the diffusion behavior of Te in Ni-based alloy

. J. Nucl. Mater. 497, 101-106 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2017.10.062Effect of grain boundary carbides on the diffusion behavior of Te in Ni-16Mo-7Cr base superalloy

. Mater. Charact. 164,Effect of Mn addition on the tellurium embrittlement resistance of GH3535 alloy

. Mater. Charact. 203,A study on the resistance to tellurium diffusion of MCrAlY coating prepared by arc ion plating on a Ni-16Mo-7Cr alloy

. Corros. Sci. 229,Intergranular tellurium cracking of nickel-based alloys in molten Li, Be, Th, U/F salt mixture

. J. Nucl. Mater. 440, 243-249 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2013.05.001Tellurium segregation-induced intergranular corrosion of GH3535 alloys in molten salt

. Corros. Sci. 194,Simulation experiment for tellurium-induced intergranular cracking in oxidizing molten salt environment

. Corros. Sci. 225,Corrosion of commercial alloys in FLiNaK molten salt containing EuF3 and simulant fission product additives

. J. Nucl. Mater. 532,Effect of Te on the corrosion behavior of GH3535 alloy in molten LiF-NaF-KF salt

. Corros. Sci. 227,Effect of tellurium concentration on the corrosion and mechanical properties of 304 stainless steel in molten FLiNaK salt

. Corros. Sci. 212,Effect of the [U (IV)]/[U (III)] ratio on selective chromium corrosion and tellurium intergranular cracking of Hastelloy N alloy in the fuel LiF-BeF2-UF4 salt

. EPJ. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 6, 4 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1051/epjn/2019033Fission product behavior in the molten salt reactor experiment, ORNL-4865

,Measurement of europium (III) /europium (II) couple in fluoride molten salt for redox control in a molten salt reactor concept

. J. Nucl. Mater. 496, 197-206 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnucmat.2017.09.027Proton irradiation-decelerated intergranular corrosion of Ni-Cr alloys in molten salt

. Nat. Commun. 11, 3430 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17244-yOne dimensional wormhole corrosion in metals

. Nat. Commun. 14, 988 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-36588-9He-Fei Huang is an editorial board member for Nuclear Science and Techniques and was not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.