Introduction

The high-luminosity frontier presents one approach to new physics [1], as any small deviations from the standard model (SM) predictions in high-precision measurements have implications for new physics beyond the SM. In the next decade, emerging high-intensity proton accelerators will offer a unique opportunity in the exploration for new physics at an unprecedented level. Indications of new physics have been increasingly reported in the literature, for example, the anomalous muon magnetic moment

The η meson is of particular interest because it approximates a Goldstone boson arising from spontaneous chiral symmetry breaking and has zero SM charge [30]. Many strong and electromagnetic decay channels of η are forbidden at the leading order; this enhances the rare decay channels of η meson that are sensitive to new physics. Consequently, the η meson serves as an excellent low-energy laboratory for exploring new physics beyond the SM by observing the dark portal particles from η decays [28, 29, 31] or measuring small discrete symmetry breaking such as charge parity (CP) violation and charged lepton flavor violation [32, 33]. A thorough review on the theoretical developments in η and

In addition to the exploration for new physics, the high-precision study of η decay provides a unique method for testing the quantum chromodynamics (QCD) theory at low energies [53-58], probing the η structure [59-65], precisely measuring the mass difference of light quarks [66-71], and verifying axial anomalies [72-74]. The electromagnetic decay channels associated with virtual and real photons help constrain the η transition form factor with significantly smaller uncertainties [59-64]; this aids the elucidation of the muon anomalous magnetic moment [2-4]. Quark masses are the fundamental parameters of the SM. As regards experimentally constraining light quark masses, the measurement of the isospin-breaking 3π decay channels of η presents a crucial method. High-precision measurements at a super η factory can reduce the uncertainties of QCD parameters significantly. Precise measurements of some rare η decays facilitate the testing of the chiral perturbation theory at high orders [75], which is a rigorous and effective theory for strong interactions at low energies.

As η meson decays involve a wide array of physics phenomena, measurements of η decay have been conducted at facilities worldwide. First, the hadronic generation of η from fixed-target experiments, such as the WASA-at-COSY experiment [76-78] and LHCb experiment [79, 80], have been reported. The WASA-at-COSY collaboration entailed the use of the proton beam at COSY and an internal pellet target, and the number of η event yields on the order of 108. Second, the radiative decay of ϕ and

To harness the intriguing discovery potential of light dark portal particles and perform rigorous tests of the SM, it is imperative to build a super η factory using high-intensity accelerators to obtain unprecedented η meson samples. To pursue a vast number of η events, the Rare Eta Decays To Observe Physics beyond the standard model (REDTOP) experiment [31] was proposed in the 2021 US Community Study on the Future of Particle Physics using novel detection techniques. In China, a High-Intensity heavy-ion Accelerator Facility (HIAF) is under construction in Huizhou city by Institute of Modern Physics (IMP), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), which is competitive in the beam intensity. Using this near-future infrastructure, we propose a super η factory at the HIAF high-energy terminal. Undoubtedly, the proposed Huizhou η factory will generate many impactful results that will remarkably advance accelerator and detector technologies.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The proposed Huizhou η factory and its physics goals are described in Sect. 2. The conceptual design of the spectrometer is presented in Sect. 3. Some preliminary simulation results for some golden channels of the experiment are presented in Sect. 4. In Sect. 5, a concise summary and future outlooks are provided.

Huizhou η factory and its goals

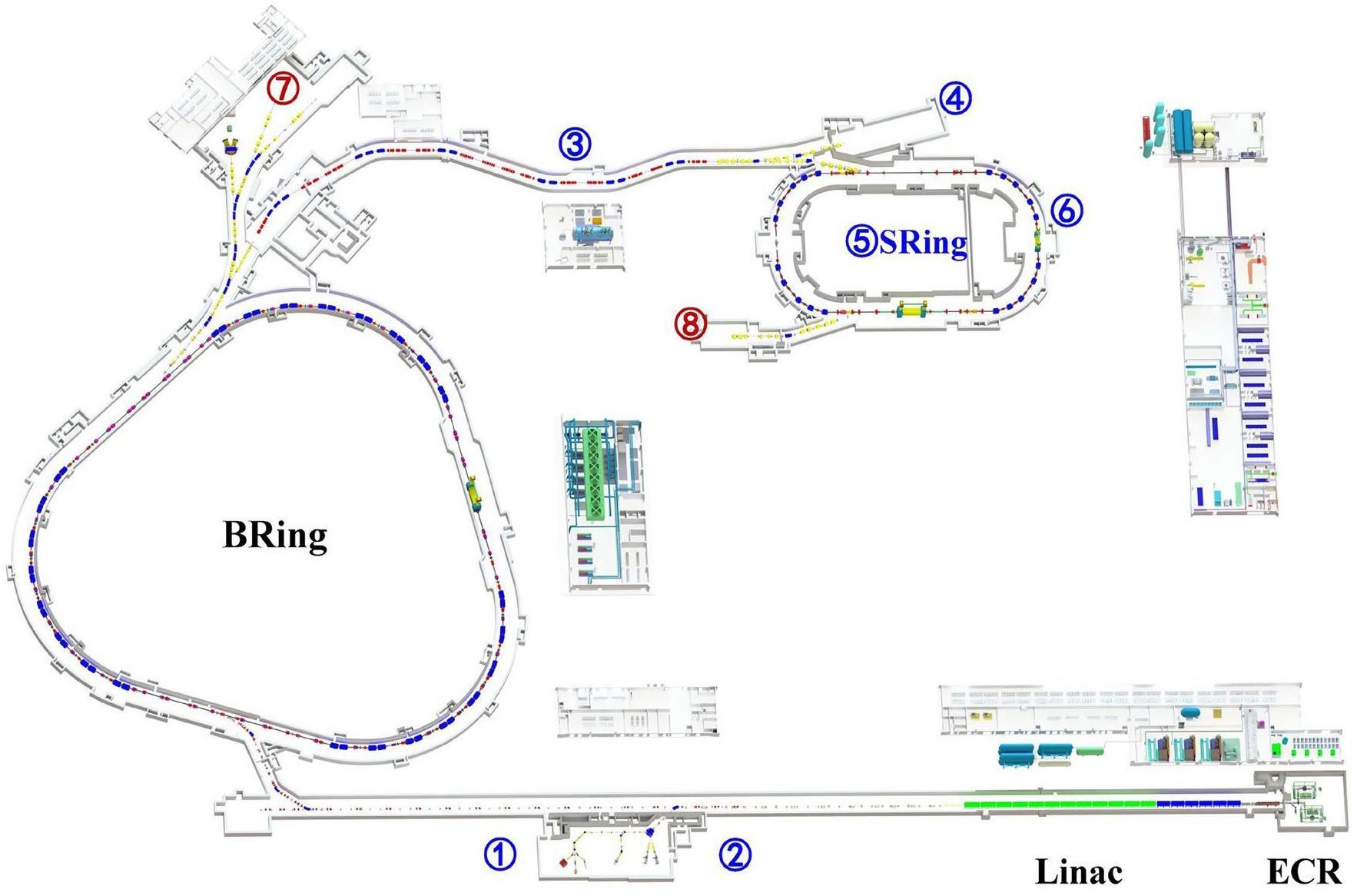

The HIAF is a major national science infrastructure facility under construction in Huizhou City, Guangdong province, China. in Southern China [98-100]. The construction of the HIAF began in December 2018, and it will be ready for commissioning by the end of 2025. The HIAF is an accelerator complex mainly consisting of a superconducting electron-cyclotron-resonance ion source, continuous-wave superconducting ion linac, booster synchrotron, high-energy fragment separator, and high-precision spectrometer ring. The layout of HIAF is shown in Fig. 1. Many terminals have been designed alongside the accelerator complex for experiments and applications. With high-intensity technology, HIAF not only provides powerful infrastructure for frontier studies in nuclear, high energy-density, and atomic physics but is also an excellent platform for heavy-ion applications in life, material, and space sciences [100]. HIAF will potentially deliver unprecedentedly intense ion beams from hydrogen to uranium with energies up to GeV/u. The maximum energy of the proton beam is 9.3 GeV [98-100]. Using heavy-ion beams, HIAF provides an extraordinary platform for studies of hypernuclei and the phase structure of high-density nuclear matter. Further, given its capability to generate high-energy proton beams, HIAF provides an excellent opportunity to study light hadron physics and to build an η factory.

At HIAF, the intensity of the proton beam is higher than 1013 ppp (particles per pulse), and the kinematic energy of a proton can reach 9 GeV through the acceleration of the ion linac and booster ring [98-100]. The pulse rate is approximately several Hertz. It is suggested that a super η factory be built at the high-energy multidisciplinary terminal after the booster ring, the terminal “⑦” shown in Fig. 1. The target is made of multiple light-nuclei foils (7Li or 9Be) with 1 cm gaps, significantly reducing the coincident background from the same vertex with no simultaneous decrease in the luminosity. Using a proton beam and light nuclear target, the η meson is efficiently produced with a controlled background at HIAF. The beam-energy thresholds are 1.26 GeV and 2.41 GeV for generating η and

The China Initiative Accelerator Driven Sub-critical System (CiADS) is another high-intensity proton accelerator designed for verifying the principle of nuclear waste disposal [105-110]. It provides a remarkably powerful continuous proton beam. The designed full power of the CiADS accelerator is 2.5 MW, with a beam intensity of 3.15×1016 pps. CiADS is also appropriate for building a super η factory, provided the energy of CiADS is upgraded to approximately 2 GeV. Because an upgrade to the CiADS accelerator is anticipated to require several years, the HIAF high-energy terminal is deemed more appropriate for the proposed Huizhou η factory.

At the Huizhou η factory, the number of η meson samples is expected to be significant, approximately four orders of magnitude greater than that of the current η events achieved worldwide. With such an enormous yield of η mesons, the main physical goals of the Huizhou η factory would be to discover new physics by searching for new particles and discrete symmetry breaking and to study SM with extremely high precision. New particles of interest emerging from η and

| Physics goals | Decay channel | |

|---|---|---|

| New physics | Dark photon & X17 | |

| Dark Higgs | π+π-π0 | |

| π0e+e- | ||

| Axion-like particle | π+π-e+e- | |

| π+π-γγ | ||

| CP violation | π+π-π0 | |

| π+π-e+e- | ||

| Lepton flavor violation | ||

| Precision test of the SM | η transition form factor | |

| π+π-γ | ||

| Light quark masses | π+π-π0 | |

| π0π0π0 | ||

| Chiral anomaly | γγ | |

| π+π-γ | ||

| Beyond SM weak decay | e+e- | |

| Test chiral perturbation theroy | π+π-γγ | |

A compact and large-acceptance spectrometer with silicon pixels

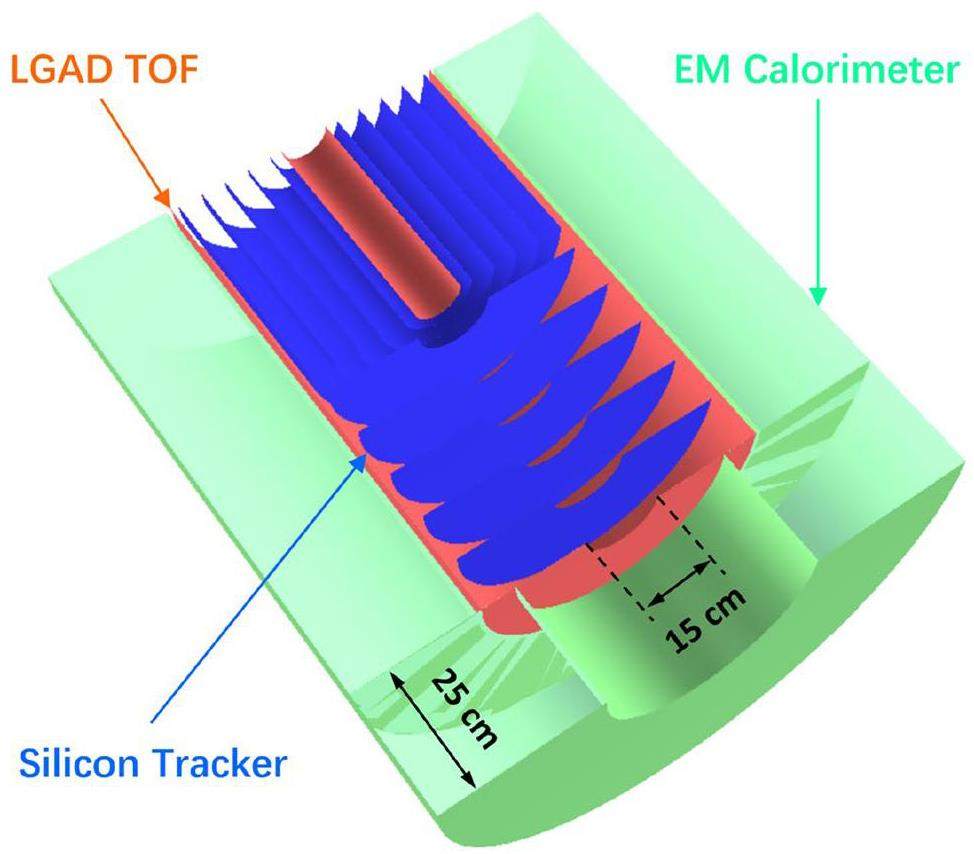

With the rapid development of monolithic silicon pixel technology [111], we developed the concept of a large acceptance and compact spectrometer with silicon pixels to detect the final-state particles at a high event rate. The current design of the spectrometer comprises four main parts: tracking system for charged particles made of silicon pixels, time-of-flight detector for particle identification made of silicon low-gain avalanche detector (LGAD), electro-magnetic calorimeter (EM calorimeter) for photon measurement made of lead glass [112], and superconducting solenoid. The 3D design of the spectrometer is shown in Fig. 2. Because of the high granularity and low position resolution of the silicon pixel detector, it is a compact spectrometer with a small volume. Therefore, the EM calorimeter and solenoid are of small size, which reduces the cost of spectrometer fabrication. The inner radius of the super-conducting solenoid is approximately 70 cm, and all the main detectors are within the solenoid.

The multi-layer target is placed inside the spectrometer close to the entrance such that there is a large acceptance for fixed-target experiments. Using the current conceptual design of the spectrometer, all forward particles except small-angle particles are covered without dead zones.

To achieve a high-rate capacity for the silicon pixel tracker, the silicon detector group attempted dual measurements of the energy and arrival time of each pixel [113-117]. Using different arrival times, hits from different events can be distinguished. The objectives of future silicon pixel chips are a resolution of 1–5 ns for arrival time, pixel size of 40–80 μm, and scan time of 100 μs for approximately 100k pixels. In the future, we will reduce the average dead time for one pixel after being hit down to 5–10 μs. The anticipated noise for deposited energy measurement will be around 100 e-, which is less than 1/5 of the minimum-ionized-particle energy deposition. Under the particle multiplicity of the Huizhou eta factory and with the pixel chip more than 5 cm away from the interaction point, the designed silicon pixel chip can easily record events at a rate greater than 100 MHz.

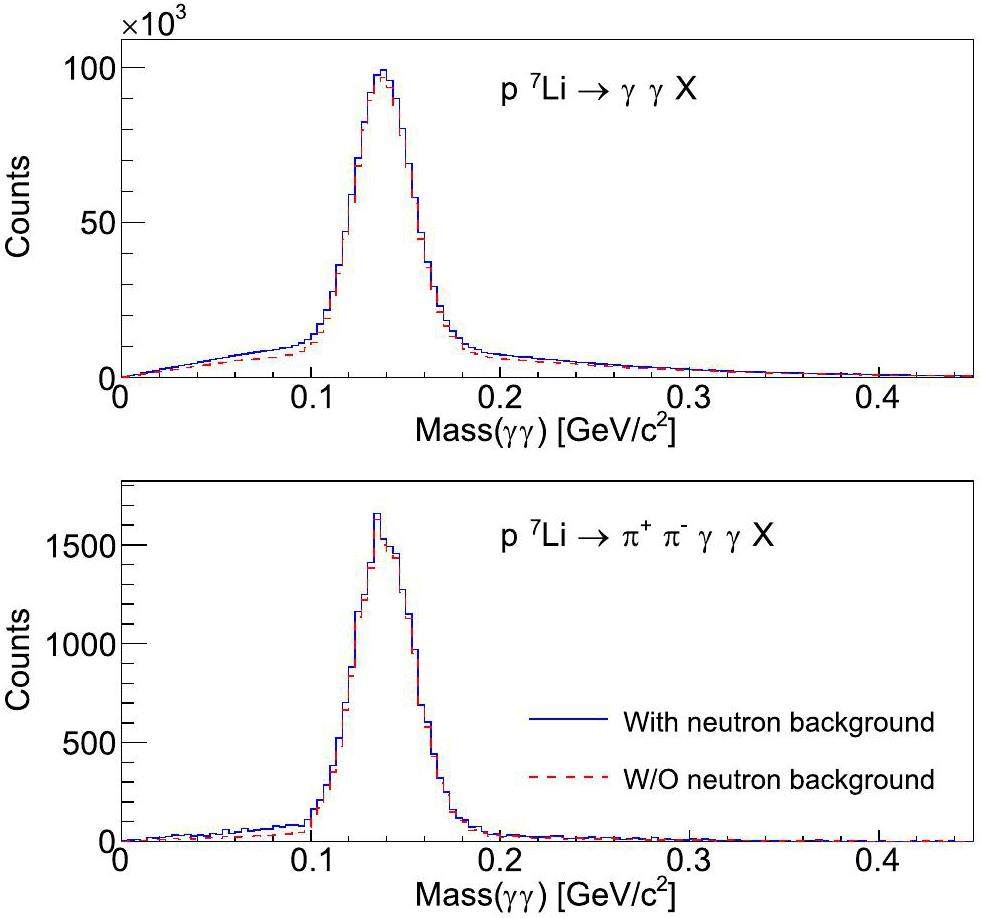

In the current conceptual design of the spectrometer, the calorimeter material is lead glass, which generates only prompt Cherenkov photons. Therefore, it has good time resolution around 100 ps for particle detection. Simultaneously, lead glass is not sensitive to the hadronic shower initiated by nucleons and pions, which means that it has low efficiency for the neutron background and offers additional hadron background suppression capability. Our Geant4 simulation [118-120] discovered that low-energy neutrons (Ek<0.3 GeV) generate almost no hits in the lead glass calorimeter, and a high-energy neutron ((Ek>1 GeV) has only approximately 45% probability of depositing more than 10 MeV energy in the calorimeter. As most neutrons from

Although a lead glass calorimeter is effective at suppressing hadron backgrounds and is cost-effective, it has significant drawbacks compared to conventional crystal calorimeters. First, the low Cherenkov light yield and severe light attenuation of lead glass result in poor energy resolution. Lead fluoride crystals, which exhibit less light attenuation, can be used instead, but they are much more expensive. Another disadvantage is poor radiation resistance. Although radiation-resistant lead glass can be used to improve this, it suffers from worse light attenuation. Additionally, due to the low light yield, the Cherenkov light being mainly in the UV range, and the detector being in a magnetic field, large-sized UV-sensitive SiPMs are required. These drawbacks present challenges for the use of lead glass in this project.

One option is to use the ADRIANO2 [125] dual-readout calorimeter currently being developed by the REDTOP group. This design combines scintillation materials and lead glass to capture both Cherenkov light and scintillation light signals. It employs longitudinal layering and a readout to provide excellent energy resolution and additional capability for low-energy particle identification. This design addresses the shortcomings of using lead glass only.

By applying a full-silicon tracker with small pixel size, the momenta of charged particles are precisely measured with a high event rate, and the sizes of all detectors scale down depending on the size of the inner tracker. This is a compact spectrometer with a large acceptance for fixed-target experiments and competitive functions. The LGAD detector for time-of-flight measurement has a low time resolution and extremely low material budget. The lead glass calorimeter is effective in reducing the neutron background, but its energy resolution is poor. We also look for new EM calorimeter technologies capable of working in a high event rate environment. Therefore, using the current spectrometer design for the Huizhou eta factory, we focus more on the charged decay channels of η mesons. The radiation dose for the spectrometer was simulated using both Geant4 [118-120] and FLUKA [126-128]. Under the condition of a 100 MHz inelastic scattering rate, over a one-month data acquisition period, the innermost LGAD is expected to experience a maximum 1 MeV neutron equivalent fluence of

Preliminary results of simulations

To determine the physics impact and feasibility of the experiment, we performed simulations of some golden channels for the Huizhou eta factory project. The simulation study is the first step for us to acquire the details regarding the resolutions, efficiency of the signal channel, background distribution, precision of the planed measurement, and/or sensitivity to new physics.

For the background events in p-A collisions, we used the GiBUU event generator [121-124] to perform the simulation. GiBUU is suitable for proton-induced nuclear reactions from low to intermediate energies, with final-state interactions being handled well [121]. The GiBUU event generator is based on the dynamic evolution of a colliding nucleus-nucleus system within the relativistic Boltzmann-Uehling-Uhlenbeck framework, which considers the hadronic potentials, equation of state of nuclear matter, and collision terms. In GiBUU, low-energy collision is dominated by resonance processes, while high-energy collision is described by a string fragmentation model implemented in Pythia. For η production,

In our simulation, the kinematic energy of the proton beam was 1.8 GeV, which is slightly below the ρ meson production threshold to lower the background. Using the lithium target, we found that the number of neutrons is approximately 1000 times the number of η mesons, and the number of π0 mesons is approximately 50 times that of η mesons. We further coded the decay chains of π0 and η. For signal event generation of dark portal particles, we constructed a simple event generator for the channels of interest. We also used another BUU generator [130] and the Urqmd package [131-133] to estimate the η production cross-section. The η production probability was 0.76% for inelastic collisions.

To quantify the detection efficiency and resolutions, we developed a detector simulation package ChnsRoot, which is based on the FairRoot framework [134, 135]. Currently, we have a reliable, fast simulation tool based on parameterizations validated by Geant4 simulations. The inner-most and outer-most radii of the silicon pixel tracker are 7.5 cm and 27.5 cm, respectively. The magnetic field strength is 0.8 Tesla. The energy resolution of the calorimeter is

To understand the physics impact of the measurement, the statistics of the produced η samples was the most important input for the simulation. To be conservative in our experimental projections, in this simulation, we considered a prior experiment with only one month of operation. Based on the evaluated luminosity and p–A cross section, the potential production rate of η can exceed 108 s-1, at an inelastic event rate of approximately 1010 s-1. A silicon pixel detector with a high granularity can operate at a high event rate (>100 MHz) without a significant pile-up of events. However, considering the radiation hardness of the detector, and limits of the current data acquisition (DAQ) system, we make a notably conservative estimate of the event rate for the Huizhou η factory experiment. The event rate of inelastic scattering is assumed to be 100 MHz, and the η production rate is approximately 760 KHz. We also assumed a conservative duty factor for the accelerator of which is 30%. Using these settings, the number of η mesons produced is 5.9×1011 for the first experiment with only onemonth of running time. Thus, in the following simulations, we assume that only 5.9×1011 eta mesons were produced in the previous experiment.

The statistics of η meson samples can be increased to magnitudes higher, as the experiment will run for years. The event rate can also be increased with improvements in the detector radiation hardness and speed of DAQ system, and the proton beam can be delivered to the high-energy terminal with a high duty factor.

Dark photon search

The decay channel

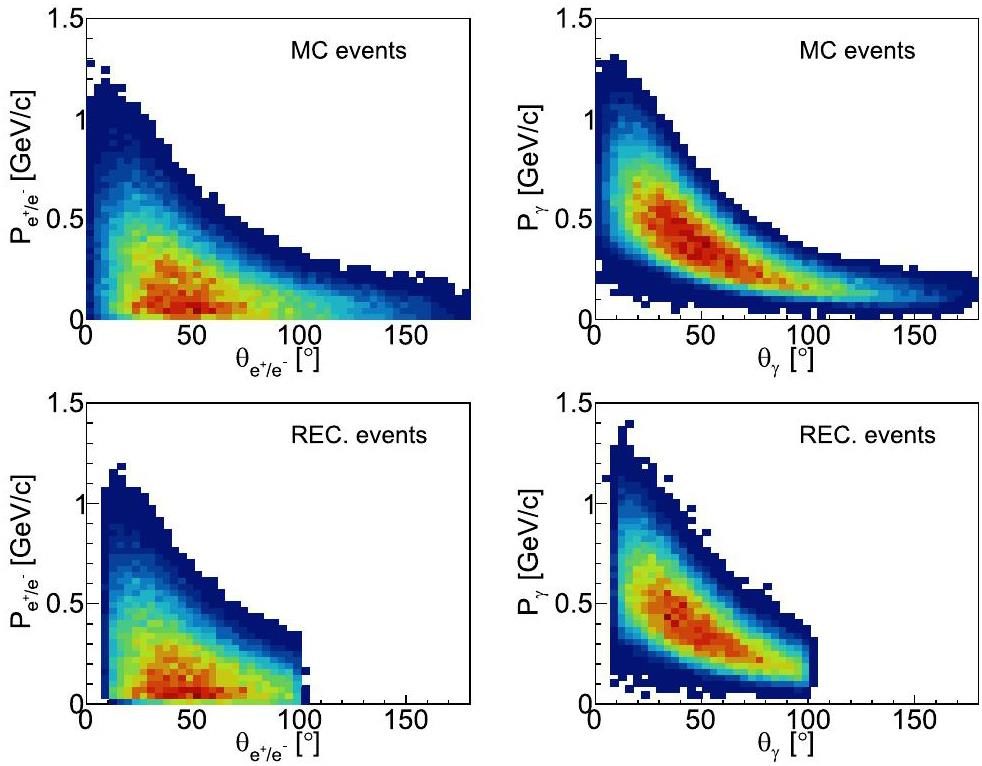

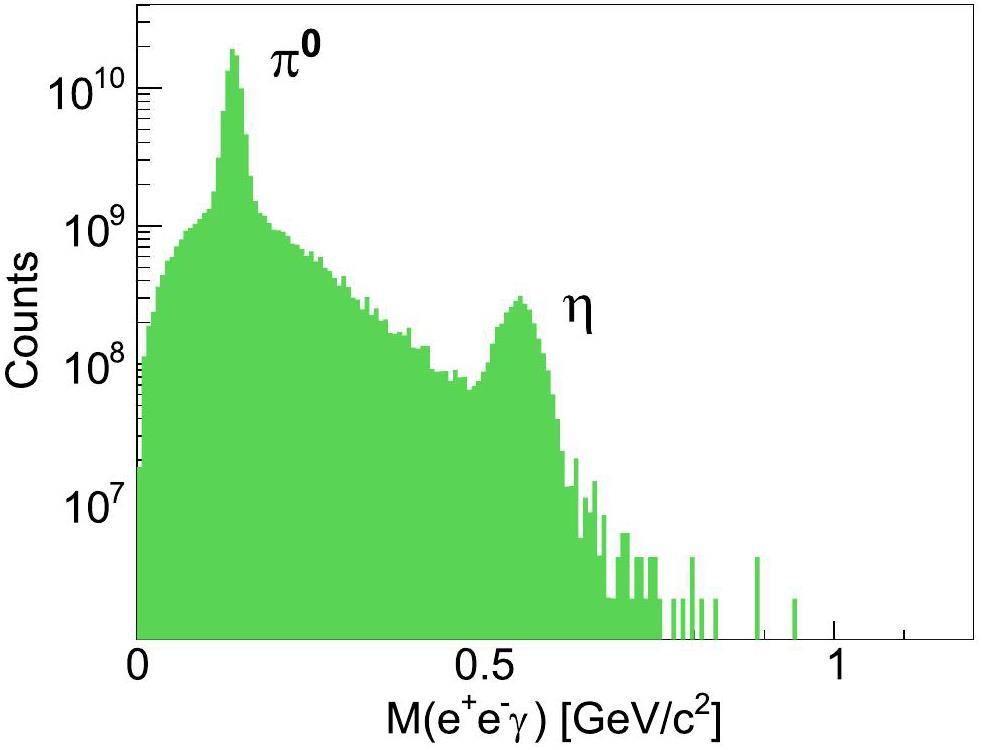

Figure 4 shows the kinematic distributions of the final-state particles of channel

The distribution of the reconstructed invariant mass of

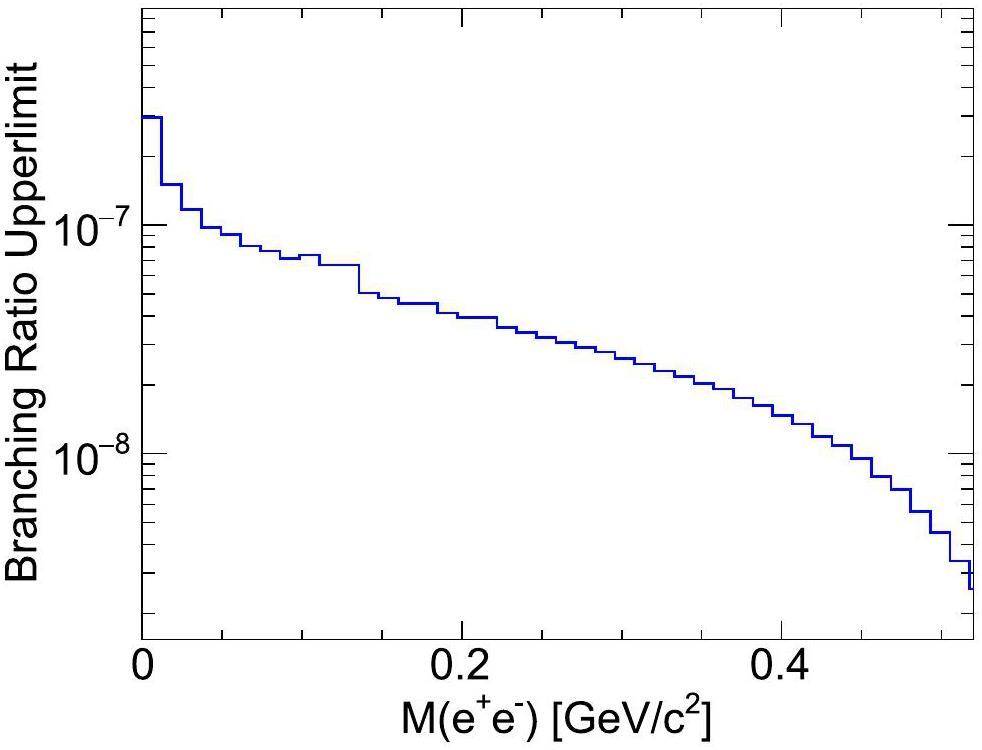

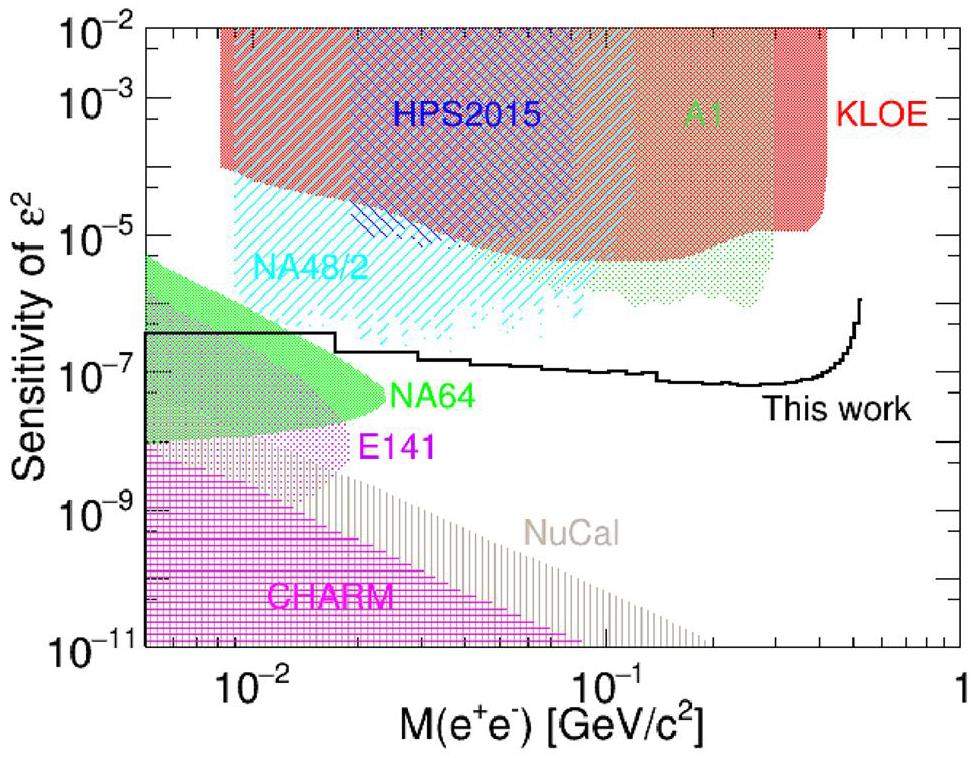

To estimate the sensitivity of the proposed experiment to the dark photon, we carefully studied the background distribution through the simulation. The background events are generated using GiBUU with some decay chains added by us. In the simulation data, there is no bump in the invariant mass distribution of electrons and positions. We assume that there is no dark photon in the simulation and the invariant mass distribution of e+e- is the pure background distribution. No observation of the dark photon means that the statistical significance of the dark photon peak is less than

Light dark Higgs search

The light dark Higgs [38-44] is another representative dark portal particle, which couples the hidden scalar field with the Higgs doublet. Thus, the dark Higgs is weakly connected to leptons and quarks via the Yukawa coupling. Therefore, the dark Higgs can be produced in the hadronic process and can decay into lepton and quark pairs. In a hadrophilic scalar model, the dark Higgs mainly couples to the up quark; thus, it predominantly decays into pions. At the Huizhou eta factory, we could search for the dark Higgs in the following channels:

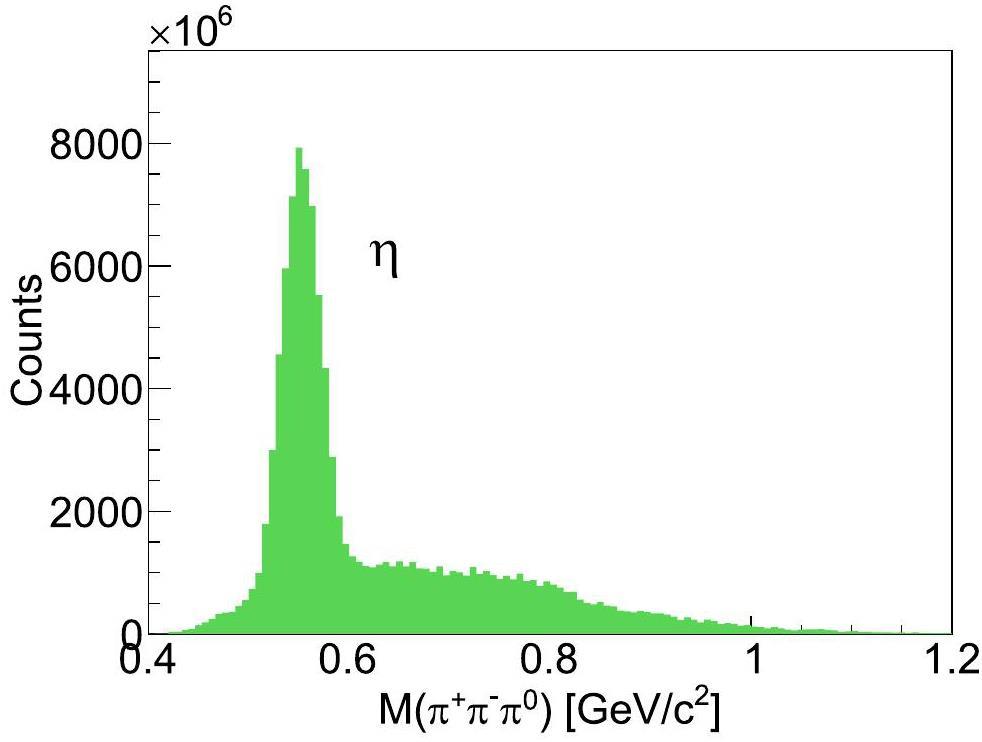

The distribution of reconstructed invariant mass of π+π-π0 is shown in Fig. 8. The peak of η meson with a low background underneath is evident. In the GiBUU simulation, the background from the direct multi-pion production is low compared to the η production because the incident energy of the proton is low (1.8 GeV). η samples from π+π-π0 can be selected with a high purity by performing a cut on the invariant mass of π+π-π0 in the range of

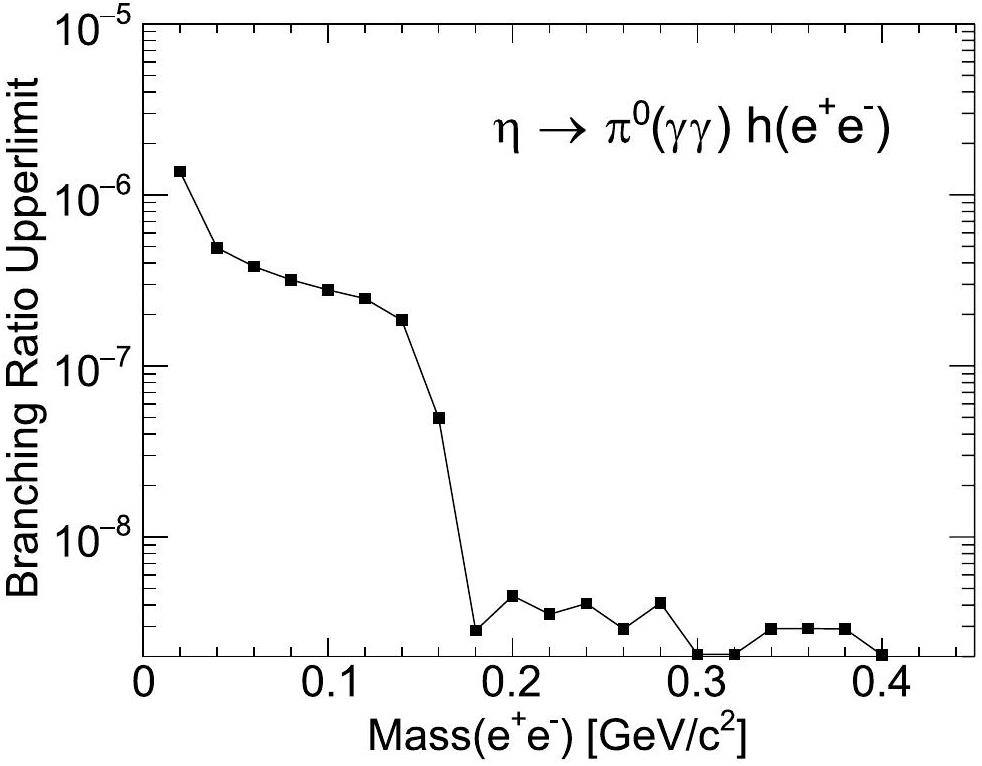

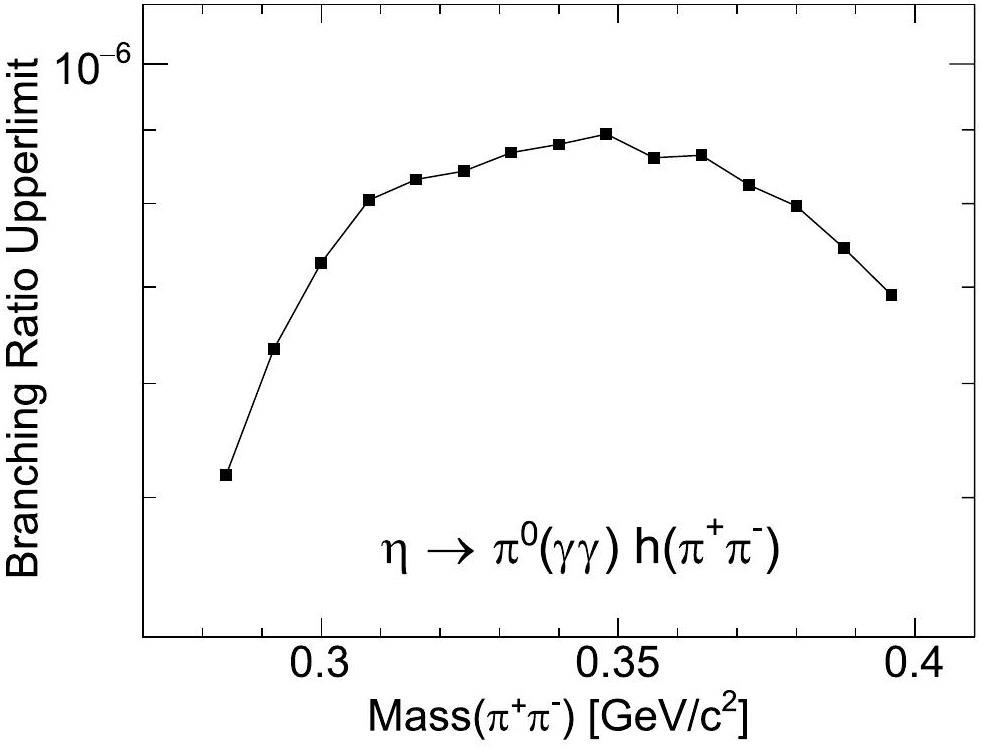

From the simulation, the efficiencies of the π0 e+ e- and π0π+π- channels are all above 40% with the conceptual design of the spectrometer. The resolutions for the invariant masses of e+e- and π+π- are 2 MeV/c2 and 1 MeV/c2, respectively. In this study, the bin width for the invariant mass was six times greater than the resolution. The background distributions without the dark Higgs particle are simulated using the GiBUU event generator, and the total number of inelastic scattering events scales up to 5.9×1011. Because there is no dark Higgs observed in our simulation data, the upper limit of the branching ratio of the dark Higgs particle is given by the formula in Eq. (1). The BR upper limits of the light dark Higgs particle in π0 e+ e- and π0π+π- channels are shown in Fig. 9 and Fig. 10, respectively, as a function of the mass of the dark Higgs.

As evident from Fig. 10, the BR upper limit of dark Higgs in the

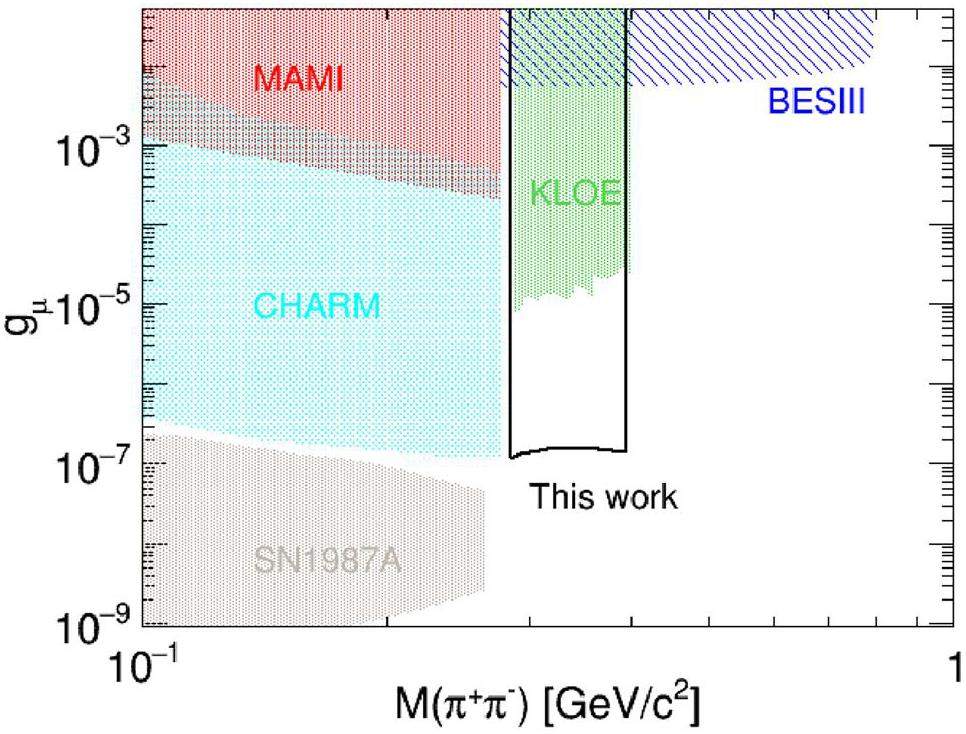

Under the hadrophilic scalar model [41, 40], the sensitivity to the parameter gu (coupling of the dark scalar to the first-generation quark) is computed and shown in Fig. 11, compared with the constraints provided by previous experimental data (BESIII [151], KLOE [83], MAMI [152], CHARM [153, 154], and SN1987A [40]). The gu sensitivity from one-month running of the proposed Huizhou η factory will exceed the current experimental limits in the accessed mass range. The proposed super η factory will play an important role in the search for light dark scalar portal particles.

C and CP violation in

The CP violation in the flavor-nondiagonal process owing to the Cabibbo—Kobayashi–Maskawa (CKM) matrix phase is insufficient to explain the matter-antimatter asymmetry in the universe. Therefore, the search for new sources and flavor-diagonal CP violation has become popular in the field of high-energy physics. The π+π-π0 decay channel of the η meson is of particular interests, as it provides a unique process to probe the flavor-diagonal C and CP violation beyond the SM. This type of CP violation is not constrained by measurement of the nucleon electro-dipole moment (EDM). Thus, high-precision experimental studies have been lacking in this regard [33]. Because of the interference between the C-conserving and C-violating amplitudes, the CP violation signal can be large. Small C and CP violations can be detected from a precise measurement of the mirror symmetry in the Dalitz decay plot of the π+π-π0 channel.

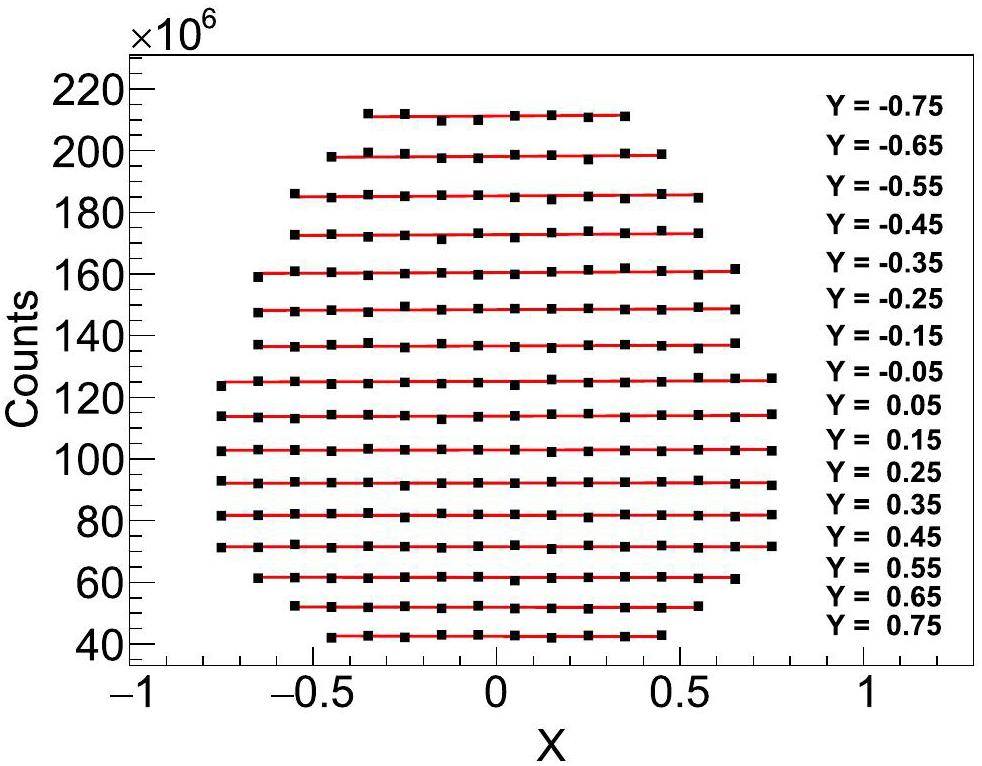

The direct observable of the charge asymmetry and CP violation is mirror symmetry breaking in the Dalitz plot of

The π+π-π0 channel is a major decay channel of the η meson, and we can obtain a huge number of decay events from the Huizhou eta factory experiment. From the simulation, the efficiency for the 3 pion channel is estimated to be approximately 45%. The event distributions in the different X and Y bins are shown in Fig. 12 for one-month running of the experiment. The statistical error bars are too small to display in the figure. We performed a model fit to the data using Eq. (4). The uncertainty of the parameter c is approximately 5× 10-5, which is two orders of magnitude smaller than those of the current analyses of COSY and KLOE-II data [77, 83]. Over the years running the project, the C and CP violation can be tested at a satisfactory level of precision.

Low-background η data from exclusive channel

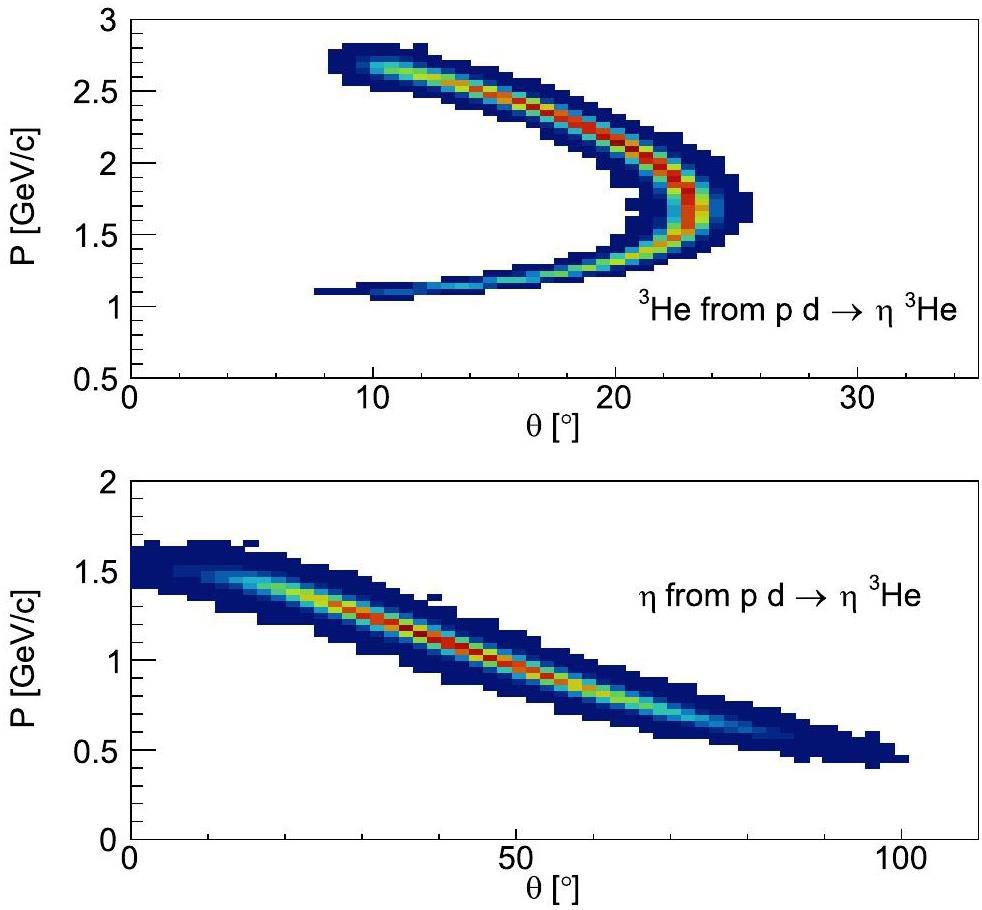

Here, we emphasize that low-background data of η mesons can be obtained at the Huizhou eta factory via the 3He tagged events of the reaction

Figure 13 shows the two-dimensional kinematic distributions of 3He and η in the momentum vs. angle plane. Evidently, the final 3He mainly goes to the region of scattering angle from 15° to 25°, whereas the η meson has a scattering angle mainly in the range from 20° to 70°. The conceptual design of the spectrometer is suitable for tagging 3He and collecting the decay particles of the η meson with high acceptance. As evident from Fig. 13, the momentum and angular resolutions of the silicon pixel tracker are excellent for selecting exclusive events of

In short, using the high-intensity proton beam and deuterium target, we can measure with both high luminosity and precision at the Huizhou eta factory. These high-statistic and low-background data are valuable in the search for new light particles, looking for the violations of CP and other discrete symmetries, measuring the transition form factor and

Summary and outlook

A super η factory at Huizhou is proposed for pursuing a variety of meaningful and challenging physical goals. HIAF accelerator complex and conceptual design of the spectrometer are briefly discussed. More than 1013 η mesons can be produced with 100% duty factor of the accelerator. The performance of the spectrometer is studied with Geant4 simulation, demonstrating satisfactory efficiency and resolution. The designed spectrometer is particularly useful for the detection of charged particles and exhibits the radiation hardness required for high-luminosity experiments.

Through simulations, some key channels of the Huizhou η factory experiment are investigated. The preliminary results from the fast simulation show that the Huizhou η factory will play a crucial role in searching for the predicted light dark portal particles and new sources of CP violation. The proposed experiment has the potential to significantly constrain the parameter space of the dark photon in the low-mass region together with other experiments. The sensitivity to light dark scalar particle is estimated to be at an unprecedented level. The C and CP violation in the channel

After completing the planned accumulation of η decay samples, we could increase the beam energy and produce the

To further improve the discovery potential of the spectrometer, it is essential to enhance its capacity to detect neutral particles. The current lead glass EM calorimeter exhibits standard energy resolution; therefore, new calorimeter technologies with fast response times (<100 ps) and low energy resolution (<3.5% at 1 GeV) is imperative. With the rapid development of silicon photomultipliers and electronics, dual-readout calorimetry for collecting scintillation and Cherenkov photons is a viable option for updating the EM calorimeter. The scintillation material significantly improves the energy resolution, while the Cherenkov light provides a sharp time resolution. The particle identification ability can also be enhanced using the dual-readout calorimeter by comparing scintillation and Cherenkov signal amplitudes. Future developments in silicon pixel detectors and electronics will benefit the proposed Huizhou η factory project, enabling improvements in radiation hardness and resolutions, which increase the event-rate limit for the planned high-luminosity experiments.

Fundamental Physics at the Intensity Frontier

. arXiv:1205.2671, https://doi.org/10.2172/1042577Measurement of the positive muon anomalous magnetic moment to 0.20 ppm

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131,Measurement of the positive muon anomalous magnetic moment to 0.46 ppm

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126,Measurement of the anomalous precession frequency of the muon in the fermilab muon g-2 experiment

. Phys. Rev. D 103,Observation of anomalous internal pair creation in 8Be: A possible indication of a light, neutral boson

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116,Protophobic fifth-force interpretation of the observed anomaly in 9Be nuclear transitions

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117,Particle physics models for the 17 MeV anomaly in beryllium nuclear decays

. Phys. Rev. D 95,Test of lepton universality in beauty-quark decays

. Nature Phys. 18, 277-282 (2022). [Addendum: Nature Phys. 19, (2023)]. arXiv:2103.11769, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-023-02095-3Tests of lepton universality using B0→KS0l+l− and B+→K*+l+l− decays

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128,Test of lepton universality with Λb0→pK−l+l− decays

. JHEP 05, 040 (2020). arXiv:1912.08139, https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP05(2020)040Lepton universality violation and lepton flavor conservation in B-meson decays

. JHEP 10, 184 (2015). arXiv:1505.05164, https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP10(2015)184Assessing lepton flavor universality violations in semileptonic decays

. arXiv:2308.05677Direct detection of a break in the teraelectronvolt cosmic-ray spectrum of electrons and positrons

. Nature 552, 63-66 (2017). arXiv:1711.10981, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature24475An anomalous positron abundance in cosmic rays with energies 1.5-100 GeV

. Nature 458, 607-609 (2009). arXiv:0810.4995, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07942An excess of cosmic ray electrons at energies of 300-800 GeV

. Nature 456, 362-365 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07477The energy spectrum of cosmic-ray electrons at TeV energies

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101,Early spi / integral measurements of 511 keV line emission from the 4th quadrant of the galaxy

. Astron. Astrophys. 407,Aip conf proc and the early universe: a review

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 119,Brief review of recent advances in understanding aip conf proc and dark energy

. New Astron. Rev. 93,A new era in the search for aip conf proc

. Nature 562, 51-56 (2018). arXiv:1810.01668, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0542-zA survey of aip conf proc and related topics in cosmology

. Front. Phys. (Beijing) 12,Aip conf proc candidates from particle physics and methods of detection

. Ann. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 48, 495-545 (2010). arXiv:1003.0904, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-astro-082708-101659Dark energy and the accelerating universe

. Ann. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 46, 385-432 (2008). arXiv:0803.0982, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.astro.46.060407.145243Direct detection of dark energy: The xenon1t excess and future prospects

. Phys. Rev. D 104,Dark energy versus modified gravity

. Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 66, 95-122 (2016). arXiv:1601.06133, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nucl-102115-044553Dark energy: A brief review

. Front. Phys. (Beijing) 8, 828-846 (2013). arXiv:1209.0922, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11467-013-0300-5Aip conf proc, dark energy, and alternate models: A review

. Adv. Space Res. 60, 166-186 (2017). arXiv:1704.06155, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2017.03.043Exploring portals to a hidden sector through fixed targets

. Phys. Rev. D 80,The search for feebly interacting particles

. Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 71, 279-313 (2021). arXiv:2011.02157, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nucl-102419-055056Review of particle physics

. PTEP 2022,The REDTOP experiment: Rare η/η′ Decays To Probe New Physics

. arXiv:2203.07651Precision tests of fundamental physics with η and η′ mesons

. Phys. Rept. 945, 1-105 (2022). arXiv:2007.00664, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2021.11.001Patterns of cp violation from mirror symmetry breaking in the η→π+π−π0 dalitz plot

. Phys. Rev. D 101,Two U(1)’s and epsilon charge shifts

. Phys. Lett. B 166, 196-198 (1986). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(86)91377-8Two z’s or not two z’s?

Phys. Lett. B 136, 279-283 (1984). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(84)91161-4Extra U(1)’s and new forces

. Nucl. Phys. B 347, 743-768 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1016/0550-3213(90)90381-MOn the search for a new spin 1 boson

. Nucl. Phys. B 187, 184-204 (1981). https://doi.org/10.1016/0550-3213(81)90122-XThe minimal model of nonnato adv sci i. c-mat: A singlet scalar

. Nucl. Phys. B 619, 709-728 (2001). arXiv:hep-ph/0011335, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0550-3213(01)00513-2Minimal extension of the standard model scalar sector

. Phys. Rev. D 75,Probing light aip conf proc with a hadrophilic scalar mediator

. Phys. Rev. D 100,Flavor-specific scalar mediators

. Phys. Rev. D 98,Higgs-field portal into hidden sectors

. arXiv:hep-ph/0605188Scalar phantoms

. Phys. Lett. B 161, 136-140 (1985). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(85)90624-0Secluded wimp aip conf proc

. Phys. Lett. B 662, 53-61 (2008). arXiv:0711.4866, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2008.02.052Manifesting the invisible axion at low-energies

. Phys. Lett. B 169, 73-78 (1986). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(86)90688-XCollider probes of axion-like particles

. JHEP 12, 044 (2017). arXiv:1708.00443, https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP12(2017)044Coupling qcd-scale axionlike particles to gluons

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123,Study of the interactions of the axion with mesons and photons using a chiral effective lagrangian model

. Eur. Phys. J. C 80, 302 (2020). arXiv:1906.03104, https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-020-7849-2On the interplay between astrophysical and laboratory probes of MeV-scale axion-like particles

. JHEP 07, 050 (2020). arXiv:2004.01193, https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP07(2020)050How to find neutral leptons of the νmsm?

JHEP 10, 015 (2007). [Erratum: JHEP 11, 101 (2013)]. arXiv:0705.1729, https://doi.org/10.1088/1126-6708/2007/10/015The search for heavy majorana neutrinos

. JHEP 05, 030 (2009). arXiv:0901.3589, https://doi.org/10.1088/1126-6708/2009/05/030The miniboone anomaly and heavy neutrino decay

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103,Phenomenological lagrangians

. Physica A 96, 327-340 (1979). https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4371(79)90223-1Chiral perturbation theory to one loop

. Annals Phys. 158, 142 (1984). https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-4916(84)90242-2Chiral perturbation theory: Expansions in the mass of the strange quark

. Nucl. Phys. B 250, 465-516 (1985). https://doi.org/10.1016/0550-3213(85)90492-4Chiral perturbation theory

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 35, 1-80 (1995). arXiv:hep-ph/9501357, https://doi.org/10.1016/0146-6410(95)00041-GChiral perturbation theory

. Rept. Prog. Phys. 58, 563-610 (1995). arXiv:hep-ph/9502366, https://doi.org/10.1088/0034-4885/58/6/001Chiral perturbation theory

. Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 57, 33-60 (2007). arXiv:hep-ph/0611231, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.nucl.56.080805.140449New determination of the η transition form factor in the dalitz decay η→e+e−γ with the crystal ball/taps detectors at the mainz microtron

. Phys. Rev. C 89,Measurement of the ω→π0e+e− and η→e+e−γ dalitz decays with the a2 setup at mami

. Phys. Rev. C 95,Dielectron pairs from η meson decays at wasa detector

. EPJ Web Conf. 199, 02011 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/201919902011Observation of the rare η→e+e−e+e− decay with the kloe experiment

. Phys. Lett. B 702, 324-328 (2011). arXiv:1105.6067, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2011.07.033Measurement of η meson decays into lepton-antilepton pairs

. Phys. Rev. D 77,Observation of the dalitz decay η′→γe+e−

. Phys. Rev. D 92,The η transition form factor from space- and time-like experimental data

. Eur. Phys. J. C 75, 414 (2015). arXiv:1504.07742, https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-015-3642-zBehavior of current divergences under su(3) x su(3)

. Phys. Rev. 175, 2195-2199 (1968). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.175.2195The problem of mass

. Trans. New York Acad. Sci. 38, 185-201 (1977). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2164-0947.1977.tb02958.xChiral su(3) x su(3) as a symmetry of the strong interactions

. Phys. Rev. 183, 1245-1260 (1969). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.183.1245eta → 3π to One Loop

. Nucl. Phys. B 250, 539-560 (1985). https://doi.org/10.1016/0550-3213(85)90494-8Current mass ratios of the light quarks

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 56, 2004 (1986). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.56.2004The ratios of the light quark masses

. Phys. Lett. B 378, 313-318 (1996). arXiv:hep-ph/9602366, https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(96)00386-3Consequences of anomalous ward identities

. Phys. Lett. B 37, 95-97 (1971). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(71)90582-XGlobal aspects of current algebra

. Nucl. Phys. B 223, 422-432 (1983). https://doi.org/10.1016/0550-3213(83)90063-9Neutral pion lifetime measurements and the qcd chiral anomaly

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 49 (2013). arXiv:1112.4809, https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.85.49Eta →pi0 gamma gamma to O (p**6) in chiral perturbation theory

. Nucl. Phys. B 459, 283-310 (1996). arXiv:hep-ph/9508407, https://doi.org/10.1016/0550-3213(95)00598-6Search for c violation in the decay η→π0+e++e− with wasa-at-cosy

. Phys. Lett. B 784, 378-384 (2018). arXiv:1802.08642, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2018.07.017Measurement of the η→π+π−π0 dalitz plot distribution

. Phys. Rev. C 90,η meson physics with wasa-at-cosy

. EPJ Web Conf. 199, 01006 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/201919901006Production of η and η′ mesons in pp and pPb collisions

. Phys. Rev. C 109,Search for the cp-violating strong decays η→π+π− and η′(958)→π+π−

. Phys. Lett. B 764, 233-240 (2017). arXiv:1610.03666, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2016.11.032The kloe-2 experiment: Overview of recent results

. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 34,Upper limit on the η→π+π− branching fraction with the KLOE experiment

. JHEP 10, 047 (2020). arXiv:2006.14710, https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP10(2020)047Precision measurement of the η→π+π−π0 dalitz plot distribution with the kloe detector

. JHEP 05, 019 (2016). arXiv:1601.06985, https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP05(2016)019Measurement of the branching ratio and search for a cp violating asymmetry in the η→π+π−e+e−(γ) decay at kloe

. Phys. Lett. B 675, 283-288 (2009). arXiv:0812.4830, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2009.04.013Measurement of the absolute branching fractions of j/ψ→γη and η decay modes

. Phys. Rev. D 104,Measurement of the matrix elements for the decays η→π+π−π0 and η/η'→π0π0π0

. Phys. Rev. D 92,Evidence for the cusp effect in η′ decays into η π0π0

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130,Precision measurement of the branching fractions of η′ decays

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122,Precision study of η′→γπ+π− decay dynamics

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120,Study of η andη’ Photoproduction at MAMI

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118,Study of the γp−>ηp reaction with the crystal ball detector at the mainz microtron(mami-c)

. Phys. Rev. C 82,Update to the jef proposal (pr12-14-004)

., https://www.jlab.org/exp_prog/proposals/17/C12-14-004.pdf, accessedPhotoproduction of neutral mesons in nuclear electric fields and the mean life of the neutral meson

. Phys. Rev. 81, 899 (1951). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.81.899A new measurement of the π0 radiative decay width

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106,Precision measurement of the neutral pion lifetime

. Science 368, 506-509 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aay6641The gluex beamline and detector

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 987,Electromagnetic calorimeters based on scintillating lead tungstate crystals for experiments at jefferson lab

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 1013,High intensity heavy ion accelerator facility (hiaf) in china

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. B 317, 263-265 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nimb.2013.08.046Status of the high-intensity heavy-ion accelerator facility in china

. AAPPS Bull. 32, 35 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43673-022-00064-1The legacy of the experimental aip conf proc programme at cosy

. Eur. Phys. J. A 53, 114 (2017). arXiv:1611.07250, https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2017-12295-4Experimental study of pp η dynamics in the pp →pp η reaction

. Phys. Rev. C 69,eta-meson production in proton-proton collisions at excess energies of 40 and 72 MeV

. Phys. Rev. C 82,Measurement of the quasifree p + n →p + n + ηreaction near threshold

. Phys. Rev. C 58, 2667-2670 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.58.2667Accelerator driven system - a solution to multiple problems of society. No. 14 in IPAC’23 - 14th International Particle Accelerator Conference

, (The Status of CiADS Superconducting LINAC. No. 10 in International Particle Accelerator Conference

, (Commissioning of China ADS Demo Linac and Baseline Design of CiADS Project. No. 14 in International Conference on Aip Conf Proc

, (Physics design of the superconducting section of the ciads linac

. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 34,Beam physics design of a superconducting linac

. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 27,Towards a high-intensity muon source

. Phys. Rev. Accel. Beams 27,Advances in nuclear detection and readout techniques

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 205 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01359-0Performance of a lead-glass electromagnetic shower detector at fermilab

. Nucl. Instrum. Methods 127, 495-505 (1975). https://doi.org/10.1016/0029-554X(75)90653-9Topmetal-m: a novel pixel sensor for compact tracking applications

. arXiv:2201.10952, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2020.164557Hi’Beam-S: A Monolithic Silicon Pixel Sensor-Based Prototype Particle Tracking System for HIAF

. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 68, 2794-2800 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/TNS.2021.3128542Heavy-ion beam test of a monolithic silicon pixel sensor with a new 130 nm high-resistivity cmos process

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 1039,Design of nupix-a1, a monolithic active pixel sensor for heavy-ion physics

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 1039,Design of nupix-a2, a monolithic active pixel sensor for heavy-ion physics

. JINST 18,Geant4–a simulation toolkit

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 506, 250-303 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(03)01368-8Geant4 developments and applications

. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 53, 270 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1109/TNS.2006.869826Recent developments in geant4

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 835, 186-225 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2016.06.125Transport-theoretical description of nuclear reactions

. Phys. Rept. 512, 1-124 (2012). arXiv:1106.1344, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2011.12.001Giessen boltzmann-uehling-uhlenbeck project (gibuu)

., https://gibuu.hepforge.org/, accessedFragment formation in proton induced reactions within a buu transport model

. Phys. Lett. B 663, 197-201 (2008). arXiv:0712.3292, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2008.04.011Dilepton production in proton-induced reactions at sis energies with the gibuu transport model

. Eur. Phys. J. A 48, 111 (2012). [Erratum: Eur.Phys.J.A 48, 150 (2012)]. arXiv:1203.3557, https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2012-12111-9Preliminary results from adriano2 test beams

. Instruments 6, 49 (2022). https://doi.org/10.3390/instruments6040049Overview of the fluka code

. Annals Nucl. Energy 82, 10-18 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anucene.2014.11.007Near-threshold η production in pp collisions

. Chin. Phys. C 39,Studies of superdense hadronic matter in a relativistic transport model

. Int. J. Mod. Phys. E 10, 267-352 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218301301000575Microscopic models for ultrarelativistic heavy ion collisions

. Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 41, 255-369 (1998). arXiv:nucl-th/9803035, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0146-6410(98)00058-1Relativistic hadron hadron collisions in the ultrarelativistic quantum molecular dynamics model

. J. Phys. G 25, 1859-1896 (1999). arXiv:hep-ph/9909407, https://doi.org/10.1088/0954-3899/25/9/308Ultrarelativistic quantum molecular dynamics (urqmd)

., https://itp.uni-frankfurt.de/bleicher/index.html?content=urqmd, accessedThe fairroot framework

. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 396,Search for a dark photon in electroproduced e+e− pairs with the Heavy Photon Search experiment at JLab

. Phys. Rev. D 98,Search for light gauge bosons of the dark sector at the mainz microtron

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106,U boson searches at kloe

. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 335,Search for the dark photon in π0 decays

. Phys. Lett. B 746, 178-185 (2015). arXiv:1504.00607, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2015.04.068Addendum to the na64 proposal: Search for the a′→invisible and x→e+e− decays in 2021. Tech. rep.

,A search for short lived axions in an electron beam dump experiment

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 755 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.59.755New exclusion limits for dark gauge forces from beam-dump data

. Phys. Lett. B 701, 155-159 (2011). arXiv:1104.2747, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2011.05.046New exclusion limits on dark gauge forces from proton bremsstrahlung in beam-dump data

. Phys. Lett. B 731, 320-326 (2014). arXiv:1311.3870, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2014.02.029Constraints on sub-GeV hidden sector gauge bosons from a search for heavy neutrino decays

. Phys. Lett. B 713, 244-248 (2012). arXiv:1204.3583, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2012.06.002Searching for prompt and long-lived dark photons in electroproduced e+e- pairs with the heavy photon search experiment at jlab

. Phys. Rev. D 108,Search for a new gauge boson in electron-nucleus fixed-target scattering by the apex experiment

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107,New fixed-target experiments to search for dark gauge forces

. Phys. Rev. D 80,Dark photon production through mater sci forum in beam-dump experiments

. Phys. Rev. D 98,Strong constraints on sub-GeV dark sectors from slac beam dump e137

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113,Search for neutral metastable penetrating particles produced in the slac beam dump

. Phys. Rev. D 38, 3375 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.38.3375Amplitude analysis of the decays η′→π+π−π0 and η′→π0π0π0

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118,New measurement of the rare decay η→π0γγ with the crystal ball/taps detectors at the mainz microtron

. Phys. Rev. C 90,Search for Axion Like Particle Production in 400-GeV Proton - Copper Interactions

. Phys. Lett. B 157, 458-462 (1985). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(85)90400-9Eta decay and muonic puzzles

. Nucl. Phys. B 944,Measurement of the pd→3He η cross-section between 930-MeV and 1100-MeV

. Phys. Rev. C 65,Measurement of the dp →3He η reaction near threshold

. Phys. Lett. B 649, 258-262 (2007). arXiv:nucl-ex/0702043, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2007.04.021Precision study of the η He-3 system using the dp → He-3 η reaction

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98,Precision study of the dp →3He η reaction for excess energies between 20-MeV and 60-MeV

. Phys. Rev. C 80,Cross section ratio and angular distributions of the reaction p + d→3He + η at 48.8 MeV and 59.8 MeV excess energy

. Eur. Phys. J. A 50, 100 (2014). arXiv:1402.3469, https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2014-14100-4Cheng-Xin Zhao is an editorial board member for Nuclear Science and Techniques and was not involved in the editorial review, or the decision to publish this article. All authors declare that there are no competing interests.