Introduction

The deep seabed contains significant mineral resources, including polymetallic nodules and ferromanganese crusts. These nodules and crusts are widely distributed on the seafloor of various oceans with water depths of approximately 3500–6500 m for nodules and 800–2500 m for crusts. They are rich in manganese (Mn) and iron (each over 10 wt%) and contain substantial amounts of cobalt, nickel, and rare earth elements, making them highly valuable for exploration [1, 2]. Current exploration methods for deep-sea nodules and crusts include acoustic-based multibeam detection and mining sampling [3]. Compared to these exploration methods, in-situ mineral resource exploration methods have the advantages of being non-destructive and low cost and offering a real-time approach.

Neutron-induced reactions have a wide range of applications in resource exploration on land and on exoplanets [4-6]. The types of elements can be determined by detecting the secondary gamma-rays emitted during these reactions. When the nucleus captures a neutron and shifts to an excited state, the composite nucleus promptly emits gamma rays when de-excited. The corresponding analytical method is prompt gamma neutron activation analysis (PGNAA). When an activated composite nucleus is radioactive, its decay also emits gamma-rays. The corresponding analytical method is neutron activation analysis (NAA). These analytical methods are well established for elemental analysis and oil trapping [7-9]. However, neutron-induced reaction methods for resource exploration in deep-sea in situ environments have rarely been reported.

Mn is highly concentrated in deep-sea polymetallic nodules and crusts, which are the main components of metallic minerals, with levels commonly around 20%, peaking at 30% [10]. Additionally, 55Mn exhibits a high neutron capture cross-section of 13.3 barns for thermal neutrons [11]. Within these seabed minerals, Mn readily captures thermal neutrons to form 56Mn, with a half-life of 2.58 h. This half-life is advantageous, as it enables the acquisition of significant counts of characteristic gamma-rays following short periods of neutron irradiation, while facilitating the choice of an optimal measurement time frame to reduce interference from other elements. The beta decay of 56Mn primarily emits gamma rays with energies of 846.8 keV, 1810.7 keV, and 2113.1 keV [12], which can efficiently penetrate seawater and match the energy-detection range of standard gamma detectors. These features provide the basis for applying the NAA method to deep-sea in-situ polymetallic nodule or crust exploration. However, the application of PGNAA-based in-situ exploration methods to the deep seabed is complicated by the fact that the high chlorine content (1.9 wt%) in seawater and the high capture reaction cross-section of 35Cl (43.6 barns for thermal neutrons) can interfere with the prompt gamma-ray detection of target nuclides. Therefore, the NAA-based deep-sea in-situ exploration method is more feasible than the PGNAA method, which has high requirements for instrument’s shielding performance and energy-resolving ability.

Although NAA-based in-situ resource exploration of the deep seabed is theoretically feasible, the specific design of the instrument remains to be investigated. In this study, we designed a Deep-sea In-situ Neutron Activation Spectrometer (DINAS) through principle analysis and Monte Carlo simulation and implemented a spectrometer prototype. Monte Carlo simulations of a deep-sea in-situ neutron activation detector were used to determine the basic composition of the spectrometer and the requirements of the gamma-ray detector and electronics.

Design and simulation

Principles of the spectrometer

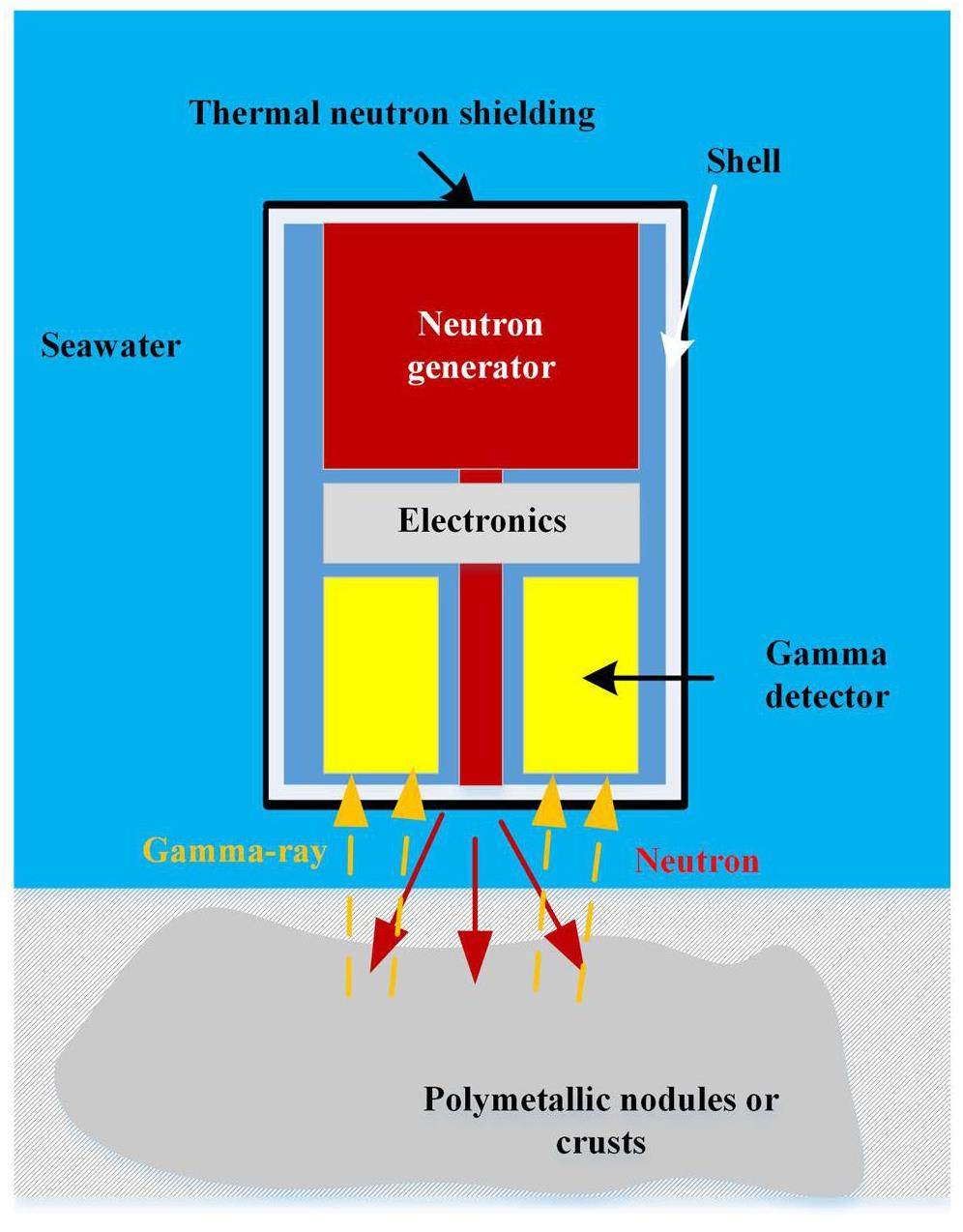

As shown in Fig. 1, DINAS consists of three components: a miniaturized neutron generator for neutron production, detector modules for gamma-ray detection, and an electronics system. Neutrons from the neutron generator irradiate the deep-sea seabed, where polymetallic nodules or crustal minerals enriched with Mn are activated, releasing characteristic gamma-rays. The gamma-ray detector identifies these rays and converts them into electrical signals, which the electronics module then analyzes to determine the energy spectrum. The generated spectrum is used to determine the presence of polymetallic nodules or crusts on the deep seabed. Beyond processing gamma-ray signals, the electronics module also manages the neutron generator operation, provides comprehensive control of the entire detector, and implements data storage and communication.

A miniaturized neutron generator is an essential component of the spectrometer based on neutron activation and primarily includes deuterium-deuterium (D-D) and D-T deuterium-tritium (D-T) neutron generators [13]. Although there are specific differences in terms of the neutron energy, neutron yield, and neutron emission angular distribution, both are suitable for the application scenarios explored in this study. Mn has a larger capture cross-section for thermal neutrons with energies less than 0.1 eV. However, D-D generators typically produce neutrons with an energy of approximately 2.45 MeV, whereas D-T generators generate neutrons with an energy of 14 MeV [14]. Therefore, it is necessary to moderate these neutrons to achieve a higher detection efficiency. Placing the spectrometer a few centimeters above the deep seabed allows fast neutrons to be moderated by seawater, enhancing the probability of Mn activation.

The neutron generator emits neutrons in all directions from the particle-targeting location. Therefore, when the target end of the neutron generator is placed near the seafloor, the seabed exhibits the most significant thermal neutron flux. To detect the activated gamma-rays of Mn efficiently, gamma detectors should be placed around the neutron generator close to the seafloor.

The operating environment of the deep seabed necessitates the encasing of the spectrometer in a titanium alloy shell that can withstand the water pressure of the deep ocean. In addition, a thermal neutron-shielding material with B4C is installed on the outside of the alloy shell to absorb the thermal neutrons moderated and returned by the seawater [15]. Similar to the larger capture cross-section of Mn for thermal neutrons, the components inside the spectrometer may be affected if they are not shielded from thermal neutrons [16].

Gamma-ray detector

The design of a gamma detector, which detects and identifies activated gamma-rays, must consider the performance of the detector and the operating environment of the deep seabed. The deep-sea working scenario requires the gamma detector to have good energy resolution and detection efficiency so that the spectrometer can accurately and quickly determine the presence of target minerals. A high-purity germanium (HPGe) detector has the best energy resolution capability [17, 18]. However, its large size and the need for low temperatures reduce its suitability for applications in deep-sea in-situ environments. Inorganic scintillators coupled with photoelectric conversion devices are the most suitable choices for this purpose.

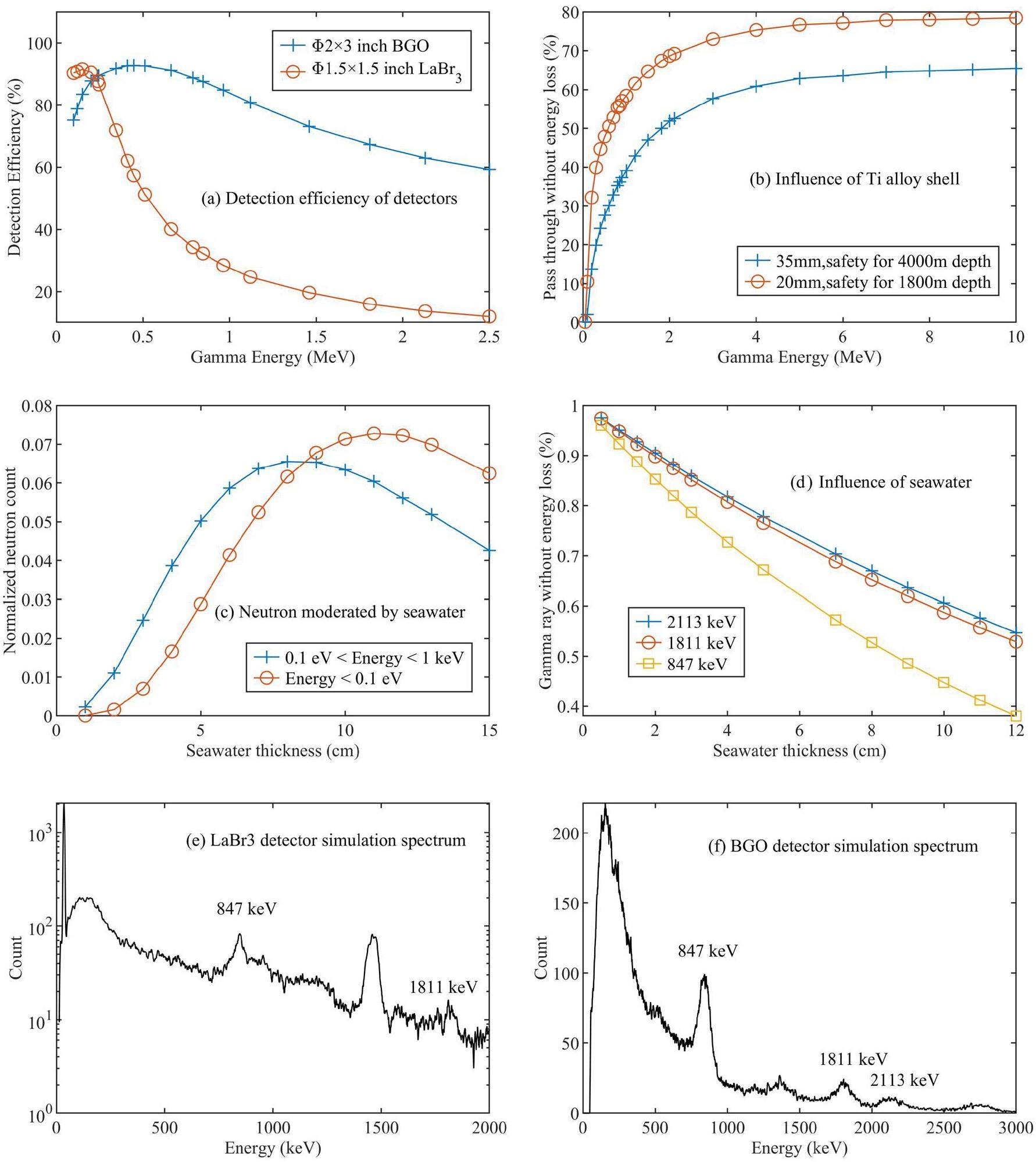

Owing to their high optical yield and energy resolution (<3.5% @662 keV), LaBr3 scintillator crystals have become the preferred choice for gamma detectors [19-21]. The natural radiation background of LaBr3 is typically considered a drawback; however, other studies have demonstrated that these backgrounds can be used to calibrate detectors in-situ on the seafloor [22]. In addition, despite the high atomic number and density of LaBr3, the growth process limits its application to large crystals. This results in a limited full-energy peak detection efficiency of smaller-sized LaBr3 for allosteric peak detection of high-energy gamma rays above 2 MeV. Therefore, we added larger, high-detection-efficiency Bi4Ge3O12 (BGO) scintillation crystal detection channels to improve the overall detection efficiency of the spectrometer. The simulation results of the full-energy peak detection efficiencies of the LaBr3 and BGO scintillators used in this study are shown in Fig. 3(a), which shows that ϕ2 × 3 inch BGO scintillation had a considerably higher detection efficiency for the 1810 keV and 2113 keV gamma-rays of Mn than ϕ1.5 × 1.5 inch LaBr3 scintillation.

Typically, it is assumed that a photomultiplier tube (PMT) coupled with scintillator crystals performs best. However, in deep-sea in-situ environments, silicon photomultipliers (SiPMs) are more suitable for photomultiplier devices because of their small size, low operating voltage, and high gain. LaBr3 and BGO scintillator crystals coupled to SiPMs can also achieve good performance [23-25].

Structure of the spectrometer

Similar to passive gamma-detection instruments operating in-situ on the deep seabed [26-28], the mechanical structure of the spectrometer consists of a watertight outer shell resistant to deep-sea pressure and an inner core with detectors, electronics, and a neutron generator. This design allows for greater flexibility in the inner-core design, making it a relatively self-contained unit that can be laboratory-operated and tested independently of the shell.

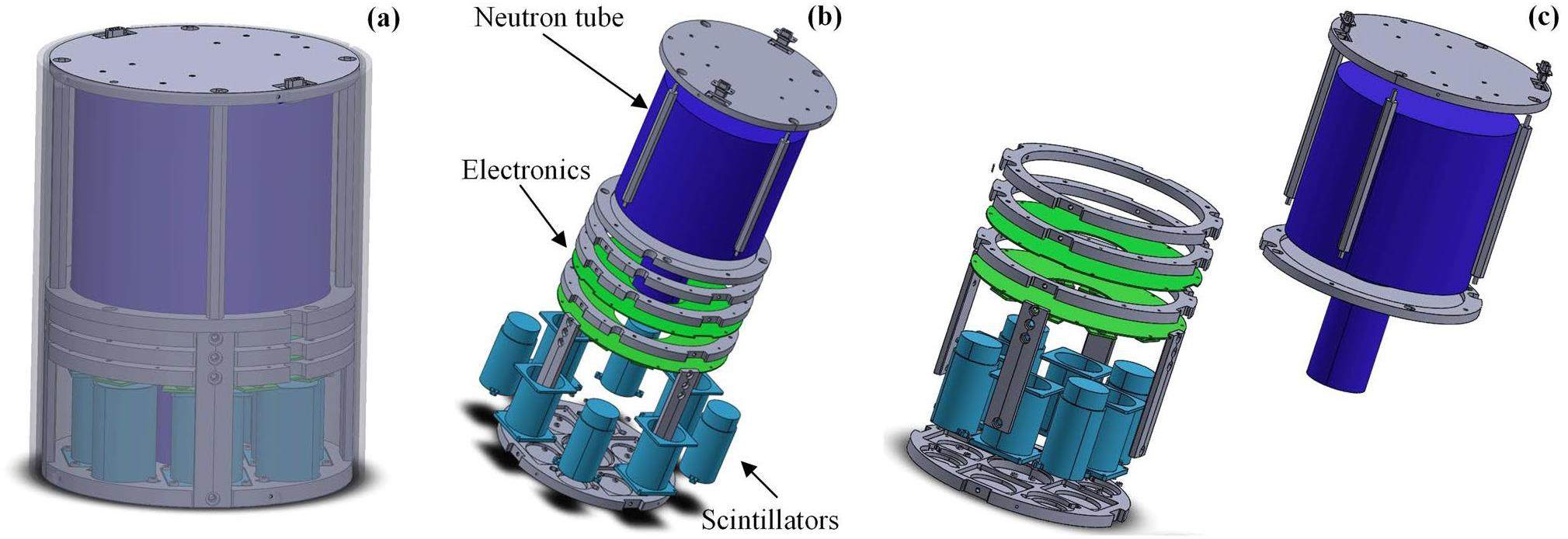

The design of the inner-core mechanical structure following the analysis in the previous sections is shown in Fig. 2. The inner-core mechanical structure comprises three parts: an inverted T-shaped D-D neutron generator, ring-shaped electronic modules, and gamma detectors consisting of multiple scintillation crystals. DINAS utilizes a compact D-D neutron generator provided by the China Academy of Engineering Physics with a neutron yield of approximately 106 neutrons/s and a maximum operational power consumption of 50 W. The neutron generator integrates a high-voltage power supply at the larger-diameter top of the inverted T-shape, with the deuterium-targeting position at the bottom placed near the base of the spectrometer to provide greater neutron flux to the seabed. The size of the neutron generator determines the overall dimensions of the inner core, which has an overall diameter of 250 mm and a height of 330 mm. LaBr3 and BGO scintillation crystal gamma detectors are positioned around the neutron generator at the base of the spectrometer to achieve the maximum geometric efficiency of gamma-ray detection. The ring-shaped electronic modules are situated above the gamma detectors, with the SiPM array directly mounted on a printed circuit board (PCB) via board-to-board connectors for convenient and reliable analog signal transmission from the detectors. Additionally, the modular ring-stacked electronics structure maximizes the PCB area, reducing the layout and wiring complexity.

The spectrometer is located on the deep-sea floor, necessitating a pressure-resistant outer shell to shield the inner core from the immense underwater pressure. The design of this shell is influenced by two factors: the inherent strength of the material, which determines the required thickness to withstand water pressure, and the impact of the material on gamma-ray detection efficiency. Titanium alloys, which are commonly used for deep-sea instruments, offer high strength and low density. They do not significantly obstruct gamma-rays, thus facilitating the penetration of characteristically activated gamma-rays through the casing to reach the detector. In this study, the spectrometer’s casing was designed as a cylindrical shell enveloping the inner core.

A finite element analysis (FEA) simulation was used to preliminarily simulate the thickness requirements of the spectrometer shell under varying depths of seawater pressure, ensuring that the maximum equivalent Von-Mises stress on the shell did not exceed the permissible stress of the titanium-alloy material. For titanium-alloy materials (with a yield strength of approximately 850 MPa) calculated with a safety factor of 1.3, the permissible stress was approximately 650 MPa. The simulation results indicated that, for exploring crusts buried at a depth of 1800 m, the safe titanium alloy thickness was 20 mm, whereas for Mn nodules buried at a depth of 4000 m, the safe thickness was 35 mm.

Simulations were conducted in Geant4 to analyze the impact of these two thicknesses of titanium-alloy shells on the gamma rays. The simulation assessed the percentage of gamma-rays that could pass through the titanium-alloy shell without any energy loss, and the results are shown in Fig. 3(b). Simulation results indicated that 847-keV gamma-rays had probabilities of approximately 55% and 36% of passing through 20-mm and 35-mm-thick titanium-alloy shells, respectively, without energy loss. Despite the shielding provided by the titanium-alloy shell, a considerable number of gamma-rays could still be detected.

Monte Carlo simulation

Monte Carlo methods are commonly used for analysis and simulation [29, 30]. In this study, Geant4 11.2 [31, 32] was used to perform a model simulation of the deep-sea in-situ neutron activation spectrometer.

A simulation model of DINAS was established in Geant4 with an overall height of 400 mm and an overall diameter of 290 mm (including the spectrometer shell). Four BGO and four LaBr3 scintillation crystals were alternately arranged around the neutron generator, as shown in Fig. 2. The thermal neutron shielding material was a 3-mm-thick flexible material containing 70% B4C. The neutron generator was abstracted as a point source 3 cm from the bottom of the spectrometer with an energy of 2.45 MeV, emitting neutrons randomly over a 4π solid angle. The physics list used in the simulation is QGSP_BERT_HP.

The distance between the spectrometer and seabed influences the moderation of fast neutrons produced by the neutron generator, as well as the detection of gamma-rays from activated Mn within the seabed. With increasing seawater thickness, there was an initial increase followed by a decrease in the thermal neutron flux at the seabed, whereas the gamma-rays found it increasingly difficult to penetrate the seawater for detection, as shown in Figs. 3(c) and (d). Based on analysis and simulations, the spectrometer was positioned 6 cm above the seabed to maximize the gamma count rate. Polymetallic nodules on the seabed generally appear spherical with diameters of several centimeters, with seawater filling the voids between the spheres. For modeling purposes, the seabed minerals were simplified to a mixture of polymetallic nodules and seawater with a thickness of 5 cm, with seawater comprising 50% of the mass. The chemical compositions of the polymetallic nodules were derived from a study by Pak [10].

After being emitted from the particle source, neutrons interact with the elements in the model, resulting in the release of promptly captured gamma-rays and their potential inelastic scattering, which produce a significant number of counts in a short period. Therefore, in the simulation, only gamma events occurring 1 ms after particle emission were recorded along with the corresponding reaction processes and nuclide types. The results were normalized per neutron to calculate the count per neutron. Such preliminary outcomes necessitate further processing to align them more closely with the actual measurement conditions. The count per neutron, denoted as N, as provided by Geant4, must also consider the influence of the nuclide half-life τh and duration of neutron irradiation T, as indicated in Eq. (1).

In addition, the energy deposition spectra obtained from the Geant4 simulation must be Gaussian broadened according to the energy resolution of the gamma detectors: 3.5% at 662 keV for the LaBr3 detector and 12% at 662 keV for the BGO detector. For a scintillating gamma detector, σ of the Gaussian peak in the spectrum and energy E approximately satisfy the function

Figures 3(e) and (f) show the neutron activation gamma-ray spectra of the LaBr3 and BGO detectors derived from Geant4 simulations and subsequent Gaussian broadening. The spectra were smoothed via a seven-point moving average to reduce statistical fluctuations and enhance clarity. The simulation results showed a finer full-energy peak resolution for LaBr3 and a higher detection efficiency of BGO for gamma-rays with energies above 2 MeV. It is essential to note that in the simulated energy spectrum of the LaBr3 detector, not only were the gamma-rays produced by the activation of seabed elements from neutron tubes considered, but also the radioactive background present in the scintillation crystal itself. This background is primarily attributed to the decay of the naturally occurring radioactive isotope 138La. For a 1.5-inch scintillation crystal, the calculated activity of 138La was approximately 60 ∼ 70 Bq. In addition to 138La, the crystals may contain trace amounts of impurity elements, such as 227Ac. The decay of 227Ac and its decay products emit α particles, contributing to counts in the regions above 2 MeV in the LaBr3 detector background energy spectrum. The design of the LaBr3 detector in this study focused solely on the energy region below 2 MeV, thus eliminating the need to consider the contribution from 227Ac. The effect of the radioactivity of 138La on the energy spectrum was simulated using Geant4, which served as a background for the activated gamma energy spectrum.

Electronics system

The electronics system is the core part of DINAS that enables it to perform the required functions. The electronic system requires implementation of the readout and processing of SiPM signals, control of the spectrometer’s operation, storage and uploading of scientific data, and control of the neutron generator.

This study adopted the waveform digitization method [33, 34] to extract charge information from SiPM output signals for two primary reasons. First, DINAS contains two types of scintillators with different light decay times (26 ns for LaBr3 and 300 ns for BGO), resulting in SiPM output current signals with varying time characteristics. Thus, processing signals through waveform digitization offers greater flexibility. Second, in a deep-sea in-situ working environment, preserving the waveform shape of the detector’s output current is beneficial for retrospective and subsequent scientific data analyses, which the waveform digitization method can effectively achieve. Therefore, this study used a waveform digitization method based on a trans-impedance amplifier (TIA) front-end amplification circuit paired with a high-speed analog-to-digital converter (ADC) device.

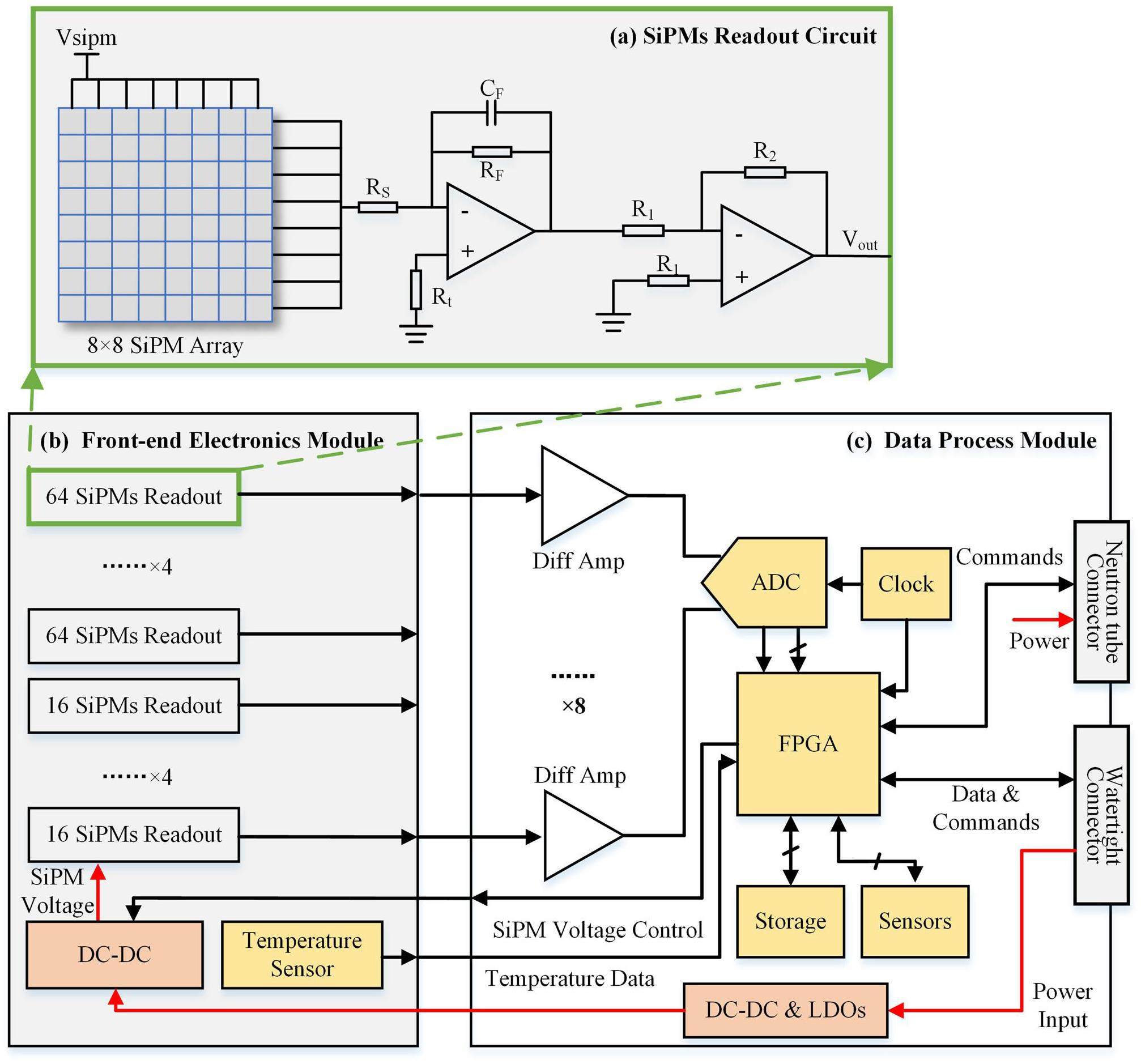

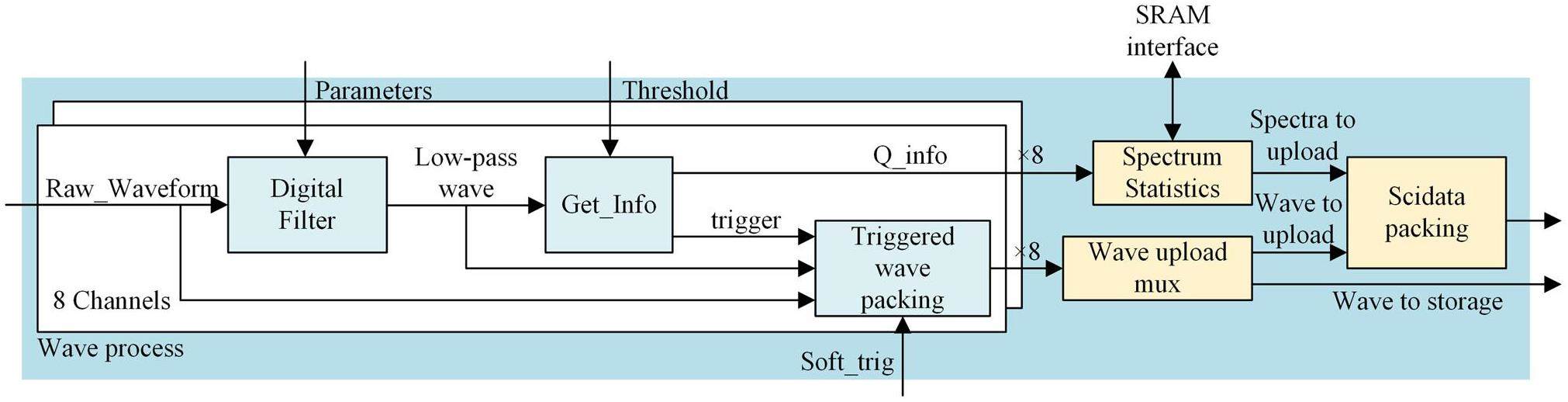

An overall diagram of the electronics system is shown in Fig. 4, designed based on a modular concept and divided into two modules: a front-end electronics module (FEM) and a data process module (DPM). The FEM implements current-to-voltage conversion based on TIAs for four 8×8 and four 4×4 SiPM array channels, along with signal conditioning and amplification. It also incorporates temperature monitoring and compensation for SiPMs, which is necessary because of their temperature-gain shift. The DPM primarily handles analog-to-digital conversion and utilizes a field-programmable gate array (FPGA) to process digitized pulse waveforms, count energy spectra, and control the spectrometer operation. The details of the two modules are presented in the following section.

Front-end electronics module

In this study, the LaBr3 scintillator was coupled to SiPM arrays of 16 OnSemi Micro-J60035 SiPMs using EJ-550 silicone optical grease, and the BGO scintillator was coupled to SiPM arrays of 64 OnSemi Micro-J60035 SiPMs. The area of the SiPM array was matched to the scintillator area for better light transmission and collection performance. The assembled scintillation crystal and SiPM detectors were mounted to the FEM via board-to-board connectors, and the FEM realized the signal readout and amplification.

SiPM readout circuits

Upon detecting the scintillation light emitted by the scintillator, the SiPM generates a current pulse, which the electronics system must process to ascertain the corresponding charge quantity, thereby determining the energy of the incident gamma-rays. For an SiPM array, the individual readouts of each SiPM would imply more significant costs in terms of the PCB area and power consumption. Consequently, this study employed a direct parallel-connection approach to reduce the number of channels, allowing a single array to output signals through a single channel.

The TIA is ideal for converting the SiPM output current into voltage; its circuit schematic is shown in Fig. 4(a). The gain in the first stage of the amplification is primarily determined by the feedback resistor RF, and the gain in the second stage is R2/R1. RS in the schematic is used to adjust the time signature of the SiPM output signal according to Eq. (2)[35].

SiPM temperature compensation

Temperature variably affects the gain of SiPMs by influencing the avalanche breakdown voltage, denoted as Vbd. As the temperature increases, the breakdown voltage increases correspondingly, resulting in a diminished gain when the operating voltage, denoted as Vsipm, remains unchanged, as shown in Eqs. (3)[35] and (4). This phenomenon leads to a shift in the peak positions of the detected energy spectrum and degrades the detector energy resolution [36, 37]. Dynamically adjusting the operating voltage of SiPMs in response to real-time temperature changes has proven to be an effective solution to this issue.

Data process module

Hardware design

The conversion of analog to digital signals is at the core of waveform digitization technology and is crucial for the DPM. For an SiPM, signals amplified through a TIA displayed a rising edge as rapid as approximately 100 ns (for the LaBr3 channel), with a bandwidth of approximately 3.5 MHz. Given the adopted digitization technique, the signals required high-frequency sampling to facilitate subsequent waveform processing. This design mandates the sampling of 10 points on the rising edge of the waveform with an ADC sampling rate of 100 Msps. An eight-channel, 100-Msps low-power ADC, ADS5295 (TI Corp.), was selected to achieve digitization.

Owing to their high real-time performance and programmability, FPGAs are extensively utilized in various research applications, making them the most suitable choice for the core data processing component of the spectrometer. The leading FPGA manufacturers include Xilinx (AMD), Altera (Intel), and Microchip. Microchip stands out for its Flash technology, which offers low power consumption and high reliability, making it ideal for power-sensitive in-situ deep-sea applications.

DINAS must be positioned vertically on the seafloor for a more efficient detection of activated gamma-rays. Therefore, the design incorporates an accelerometer to monitor the tilt of the device, allowing activation of the neutron generator only when the spectrometer is correctly placed.

To store the raw data from in-situ deep-seabed detection, a 16-GB eMMC Flash was incorporated into the DPM. Data storage, including raw waveform, spectral, and status data, was facilitated by the eMMC IP core within the FPGA.

FPGA firmware design

The core of the firmware running within the FPGA in DPM processes digitized waveforms to obtain information about the charge corresponding to the nuclear pulse waveform, which translates into the energy of the incident gamma-ray. The logical structure of the waveform processing is shown in Fig. 5.

In this study, the digital integration method was used to obtain energy information from digitized waveforms. The raw waveforms were processed using an infinite impulse response (IIR) digital low-pass filter to eliminate high-frequency noise, producing filtered waveforms that were then passed to the next-stage modules. Additionally, a digital constant-fraction timing algorithm generated trigger signals for waveforms that exceed a certain amplitude threshold, which served as the starting point for the digital integration window. Compared to simple threshold triggering, this method mitigates the impact of starting point drift due to waveform amplitude variations on energy resolution.

The time characteristics of the raw waveforms from the LaBr3 and BGO channels differed significantly. The LaBr3 channel waveform exhibited faster rise and fall times than the BGO channel waveform, which is indicative of higher-frequency components. Different filtering parameters were required for each channel to achieve optimal results.

The filtered waveforms, denoted as Wf, were first delayed by a configurable period to produce Wd, which was implemented based on FIFO in the FPGA. Upon detecting a trigger signal, the Wf signal was utilized to compute the waveform area using digital integration, whereas the Wd signal was used to calculate the pre-waveform baseline. The difference between these two calculations represented the actual energy information of the digitized waveform.

Once the charge information was obtained in real time from the eight waveform channels, the energy spectrum was dynamically compiled using SRAM external to the FPGA. For each waveform, the charge values normalized to 4096 channels served as addresses in the SRAM. The data value at each corresponding address was incremented, facilitating continuous accumulation of the energy spectrum.

Experiments and results

Energy resolution experiment

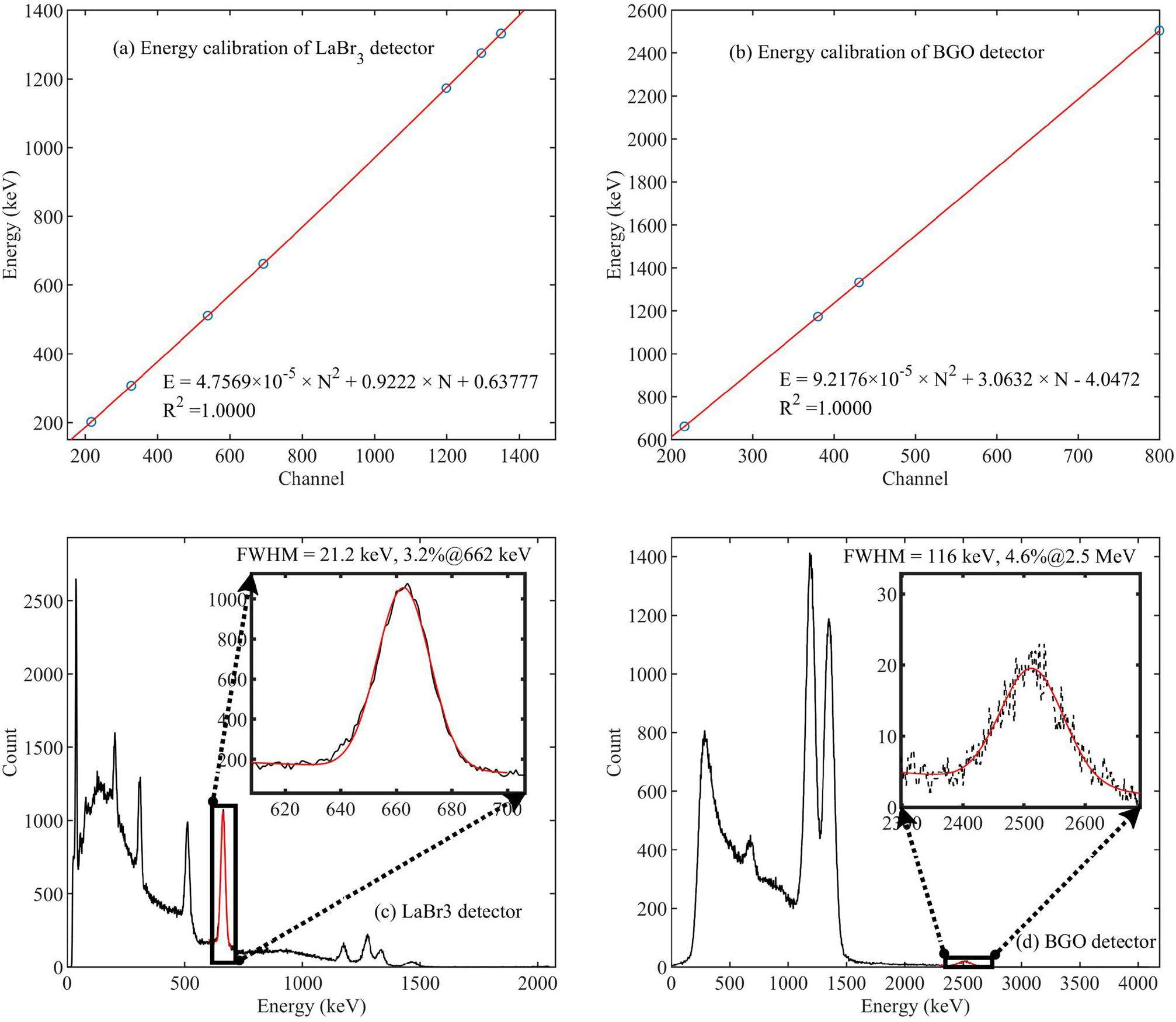

Multiple radioactive sources were used to evaluate the energy resolution of the gamma-ray detectors. The detector was calibrated using these radioactive sources according to the quadratic function of the energy-address relationship, as shown in Figs. 6(a) and (b). Figure 6(c) shows the energy spectra of 137Cs (665 keV), 22Na (511 keV and 1275 keV), 60Co (1173 keV and 1332 keV), and 176Lu (202 keV and 307 keV) measured using the LaBr3 detector. By performing a Gaussian fit on the full-energy peak at 662 keV, the full width at half maximum (FWHM) was obtained, resulting in an energy resolution of 3.2% at 662 keV. This result is comparable with the energy resolution outcomes reported in other studies. Figure 6(d) shows the energy spectra of 137Cs and 60Co measured using the BGO detector with an energy resolution of 5% at 2.5 MeV (superimposed peak of two gamma-rays of 60Co).

Test of the gamma detector at CSNS

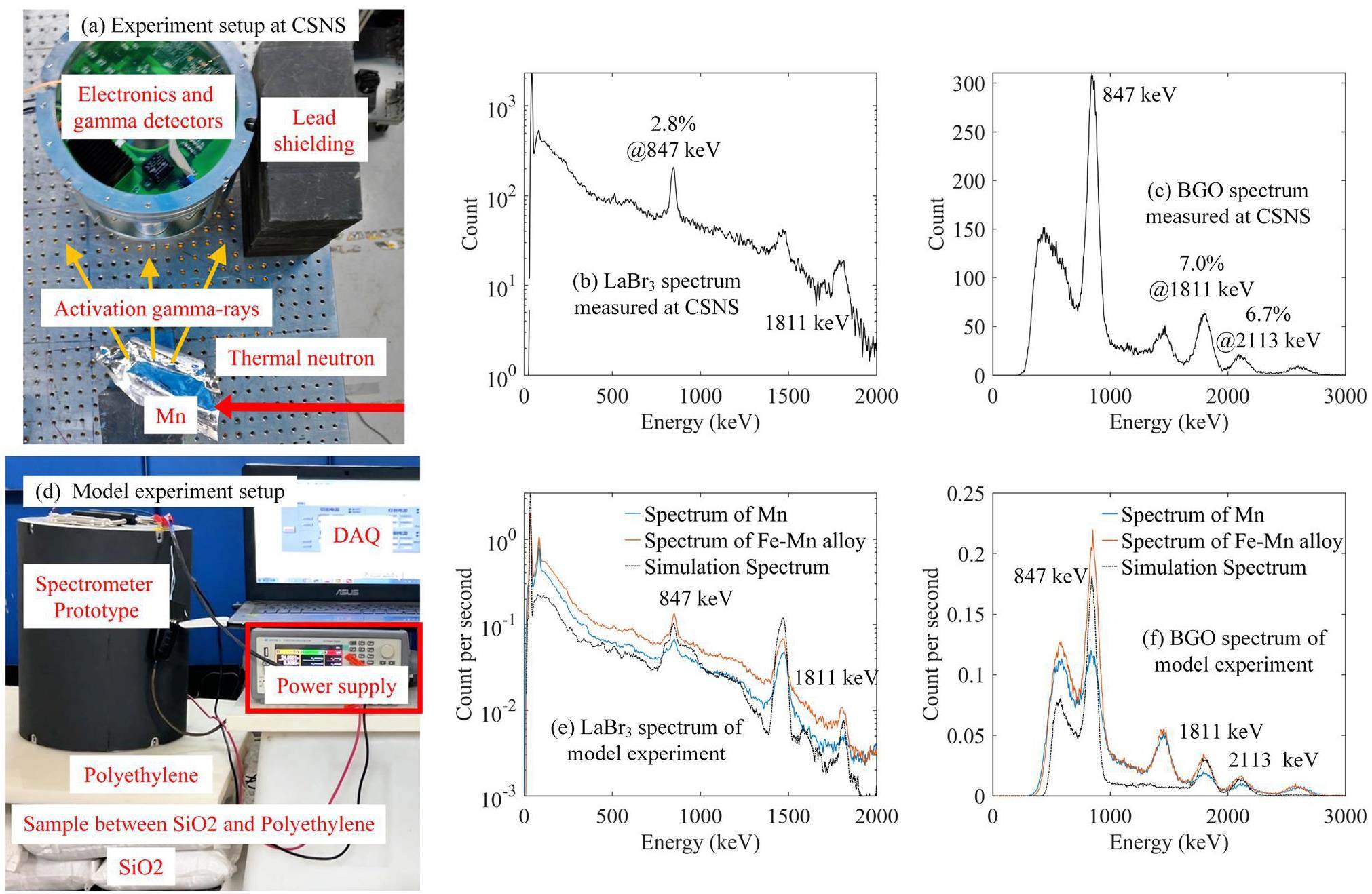

To evaluate the capability of the DINAS gamma detectors and electronics system to measure the gamma spectrum of activated Mn, thermal neutron beams from the China Spallation Neutron Source (CSNS) were employed to activate Mn as a preliminary experiment for spectrometer validation. Thermal neutron beamline No. 20 at the CSNS can provide thermal neutron beams with wavelengths ranging from 1 to 5 Å, efficiently activating Mn.

Figure 7(a) shows a photograph of the experimental setup, with the Mn metal located on the thermal neutron beamline, the detectors and electronics positioned beside the Mn, and lead bricks shielding them from the accompanying gamma-rays from the beamline. During the experiment, the irradiation time of the thermal neutron beam was approximately 10 min and the measurement time was 5 min.

The resulting activated gamma spectra are presented in Figs. 7(b) and (c), revealing significant gamma-ray peaks from Mn activation. The limited detection efficiency of LaBr3 detectors above 2 MeV, combined with their inherent radiation background, makes the detection of the 2113-keV peak of Mn challenging when using the D-D neutron generator within the spectrometer as a neutron source, which can provide a considerably lower thermal neutron flux. This underscores the importance of the BGO detector.

Spectrometer model experiment

A model experiment was conducted in the laboratory to assess the functionality of the spectrometer prototype. Simulations of the model experiment were conducted using the Monte Carlo method outlined in Section 2.4, and the results were compared with experimental data to validate the reliability of the proposed simulation model. As shown in Fig. 7(d), a 6-cm-thick polyethylene board was used to simulate the presence of seawater between the spectrometer and the seabed, with a total mass of 10 kg of Mn metal placed on the surface of the SiO2 sand. The spectrometer prototype was powered by a DC power supply and controlled by an upper computer for the data readout. The neutron generator used in the experiment was the D-D neutron generator mentioned previously, with a neutron yield of approximately 106 neutrons/s. After the neutron generator was activated, irradiation continued for approximately 1 h. Subsequently, the neutron generator was deactivated, and a 1-h measurement period commenced. Turning off the neutron generator before commencing the measurements served a dual purpose. It reduced the impact of promptly captured gamma-rays and inelastically scattered gamma-rays on the detection of Mn activation gamma-rays. Moreover, it prevented an increase in dark counts and a decline in the performance of SiPMs caused by neutron irradiation.

The activation gamma spectra of Mn detected using the two types of gamma detectors are shown in Figs. 7(e) and (f), revealing significant characteristic peaks of the Mn activation gamma-rays. For the LaBr3 detector, the characteristic peaks were superimposed on the radiation background of LaBr3, similar to the results obtained at the CSNS. Calculations showed that the peak count rate at 847 keV measured by the LaBr3 detector was 1.8 cps, whereas the BGO detector measured a peak count rate of 1.7 cps at 2113 keV. Figures 7(e) and (f) also present the activated gamma-ray spectra when the initially pure Mn sample was substituted with a ferromanganese mixture containing approximately 60 wt% Mn. No significant differences were observed in the activated gamma-ray spectra when the sample was replaced with the mixture. The characteristic gamma-rays of Mn were still distinctly detectable, with a count rate of approximately 0.8 cps at 847 keV detected by the LaBr3 detector and 1.0 cps at 847 keV detected by the BGO detector.

The experimental results showed a high degree of consistency with the Monte Carlo simulation spectra of Geant4. For the LaBr3 detector, the experimental background had a higher count than the simulation because of the imprecision of the LaBr3 background simulation model, although the characteristic Mn peaks were similar. The peak near 1460 keV resulted from the decay of 40K and electron capture (EC) decay of 138La in the LaBr3 scintillator. For the BGO detector, the experimental and simulation results aligned well at the Mn characteristic peaks, with the experimental spectrum featuring two additional background peaks corresponding to the 1460.8 Ke V gamma rays of 40K and 2614.5 Ke V gamma rays of 208Tl.

Discussions

The model experiment confirmed the viability of the in-situ exploration technique proposed in this study, proving that the designed prototype is capable of effectively detecting metal resources on the deep-sea floor in-situ. Despite these advancements, precise quantitative measurement of the elemental content of deep-sea metal minerals continues to pose a significant challenge, necessitating additional research. The following section includes an initial discussion of this topic.

In the in-situ measurements conducted in deep sea, the full-energy peak count rate A of the characteristic gamma-rays for Mn, as observed in the activated gamma energy spectrum, is theoretically described by Eq. (5).

In a deep-sea in-situ work environment, accurately obtaining the neutron flux Φ is challenging because of factors such as the neutron yield stability of the neutron generator itself, structure of the spectrometer shell, and distance between the spectrometer and seabed. Similarly, the measurement of detection efficiency ϵ is impeded by the attenuation caused by seawater. Consequently, the mass of the target element cannot be calculated directly using Eq. (5). By employing a relative analysis method from the field of neutron activation analysis, a reference element with known mass can be placed directly on the seabed. The mass of Mn can be indirectly determined by measuring the characteristic peak counts of the reference and target elements (Mn). Indium-115 (115In) serves as an ideal reference element because of its substantial neutron capture cross-section (115In(n,γ)116mIn, 157 barns for thermal neutrons) and the suitable half-life (54 min) of its activation product,116mIn [11]. Furthermore, 116mIn emits various gamma-rays, which addresses the discrepancies in detection efficiency caused by differences in gamma-ray energy. Considering the impact of seabed minerals on the neutron flux and the blocking of activated gamma-rays, empirical underwater experiments and simulations are essential to achieve more accurate results.

Conclusion

In this study, a prototype neutron-activation-based spectrometer was developed for in-situ polymetallic nodule or crust exploration on a deep seabed. The feasibility of the method and prototype for deep-sea in-situ exploration was confirmed through both simulations and experiments. The analysis of the fundamental principles of DINAS confirmed the theoretical feasibility of the neutron-activation-based exploration method, while also detailing the structure and essential components of the spectrometer, that is, a neutron generator, gamma detectors, and an electronics system. Monte Carlo simulations based on Geant4 further illustrated the rationality of the spectrometer design proposed in this study. The gamma-ray detector of the spectrometer consists of LaBr3 and BGO crystals to realize the high-resolution and high-efficiency detection of high- and low-energy rays. The electronics system consists of two modules. The FEM implements the readout of SiPM signals and temperature compensation. The DPM performs waveform digitization signal processing and controls the spectrometer based on the FPGA. The energy resolution of the gamma-ray detector was 3.2% @662 keV for the LaBr3 detector and 5.5% @2.5 MeV for the BGO detector based on radioactivity tests. The experimental activation of the neutron beamlines at the CSNS showcased the ability of the spectrometer detectors to detect activated gamma-rays. Additionally, these experiments delivered energy resolution results for the spectrometer relative to the characteristic gamma-rays of Mn: 2.8% at 847 keV using the LaBr3 detector, and 6.7% at 2.113 MeV using the BGO detector. The laboratory model experiment evaluated the functionality of the spectrometer prototype, measuring the full-energy peak count rate for characteristic Mn gamma-rays detected by the LaBr3 detector as 1.7 cps @847 keV and by the BGO detector as 1.8 cps @2.113 MeV. A comparison between the experimental and simulation results verified the accuracy of the proposed simulation models.

An overview of seabed mining including the current state of development, environmental impacts, and knowledge gaps

. Front. Mar. Sci. 4, 418 (2018). https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00418Deep-ocean mineral deposits as a source of critical metals for high- and green-technology applications comparison with land-based resources

. Ore. Geol. Rev. 51, 1-14 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oregeorev.2012.12.001Exploration of polymetallic nodules and resource assessment a case study from the German contract area in the Clarion-Clipperton zone of the tropical Northeast Pacific

. Minerals-Basel 11, 618 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/min11060618Chemical abundances of neutron-capture elements in exoplanet-hosting stars

. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 130, 1-14 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1088/1538-3873/aacc1fActive neutron and gamma-ray instrumentation for in-situ planetary science applications

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 652, 674-679 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2010.09.157Analysis of the elemental spectral characteristics of single elemental capture spectrum log using Monte-Carlo simulation

. Appl. Geophys. 16, 321-326 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11770-019-0765-2Feasibility study on neutron energy spectrum measurement utilizing prompt gamma-rays

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 933, 56-62 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2019.03.056Study on element detection and its correction in iron ore concentrate based on a prompt gamma-neutron activation analysis system

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 30, 9 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-019-0579-1Detection of heavy metals in aqueous solution using PGNAA technique

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 27, 5 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-016-0010-0Rare earth elements and other critical metals in deep seabed mineral deposits: Composition and implications for resource potential

. Minerals-Basel 9, 3 (2019). https://doi.org/10.3390/min9010003Neutron radiative capture cross sections for 23Na, 55Mn, 115In, and 165Ho in the energy range 1.0 to 19.4 MeV

. Phys. Rev. 163, 1299-1308 (1967). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.163.1299Decays of 58Mn, 57Mn, and 56Mn

. Phys. Rev. C 10, 785-794 (1974). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.10.785Design of a compact D-D neutron generator

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 904, 107-112 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2018.07.005A concise method to calculate the target current ion species fraction in D-D and D-T neutron tubes

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 987,Influence analysis of B4C content on the neutron shielding performance of B4C/Al

. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 204,An analysis of the significance of the 14N(n, p) 14C reaction for single-event upsets induced by thermal neutrons in SRAMs

. IEEE T. Nucl. Sci. 70, 1634-1642 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/tns.2023.3239407Methods for obtaining characteristic gamma-ray net peak count from interlaced overlap peak in HPGe gamma-ray spectrometer system

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 30, 11 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-018-0525-7Energy calibration of HPGe detector using the high-energy characteristic γ rays in 13C formed in 6Li+12C reaction

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 31, 49 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-020-00758-xSimulation and test of the SLEGS TOF spectrometer at SSRF

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 47 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01194-3The energy response of LaBr3(Ce), LaBr3(Ce, Sr), and NaI(Tl) crystals for GECAM

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35, 23 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01383-8Development and preliminary results of a large-pixel two-layer LaBr3 Compton camera prototype

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 121 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01273-5Self-calibration method for LaBr3 coupled with SiPM detector based on internal radiation of 138La

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 1064,A 144-SiPM 3" LaBr3 readout module for PMTs replacement in Gamma spectroscopy

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 1040,Design of a high-dynamic-range prototype readout system for VLAST calorimeter

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 149 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01291-3Pilot studies with BGO scintillators coupled to low-noise, large-area, SiPM arrays

. IEEE T. Nucl. Sci. 63, 2482-2486 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1109/tns.2016.2517739A compact NaI(Tl) with avalanche photodiode gamma spectrometer for in-situ radioactivity measurements in marine environment

. Rev. Sci. Instrum., 92, 8 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0038534A CdZnTe-based high-resolution gamma spectrometer for in-situ measurement in the marine environment

. J. Instrum. 17, 15 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-0221/17/10/p10020Design of a prototype in-situ gamma-ray spectrometer for deep sea

. J. Instrum. 15,Optimization study of chlorine detection sensitivity in concrete based on prompt gamma analysis using 252Cf neutron source

. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes. 188,Investigation of prompt gamma-ray neutron activation spectrometer at the Dalat research reactor using Geant4 simulation

. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 208,Geant4–a simulation toolkit

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 506, 250-303 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9002(03)01368-8GEANT4 User’s guide for application developers

. https://geant4-userdoc.web.cern.ch/UsersGuides/AllGuides/html/ForApplicationDevelopers/index.html. AccessedPrototype of field waveform digitizer for BaF2 detector array at CSNS-WNS

. IEEE T. Nucl. Sci. 64, 1988-1993 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1109/tns.2017.2714707Time measurement system based on waveform digitization for time-of-flight mass spectrometer

. IEEE T. Nucl. Sci. 60, 4588-4594 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1109/tns.2013.2281593Understanding and simulating SiPMs

. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. A 926, 16-35 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2018.11.118Online control of the gain drift with temperature of SiPM arrays used for the readout of LaBr3:Ce crystals

. J. Instrum. 17,Temperature dependence of CsI:Tl coupled to a PIN photodiode and a silicon photomultiplier

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 30, 27 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-019-0551-0Gain stabilization of SiPMs with an adaptive power supply

. J. Instrum. 14,A compensation circuit for the gain temperature drift of silicon photomultiplier tube

. Radiat. Detect. Technol. Methods. 7, 571-577 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41605-023-00422-zThe authors declare that they have no competing interests.