Introduction

Exploration of the mass and charge limits of atomic nuclei is a fundamental challenge in nuclear physics. With advancements in heavy-ion accelerators and advanced detection systems, the synthesis of new superheavy elements, such as element 119, following the discovery of element 118, has gained significant attention [1-6]. These efforts are crucial not only for extending the periodic table but also for deepening our understanding of nuclear shell structures. The stability of heavy elements is intricately linked to the arrangement of protons and neutrons, and many nuclear structure theories, from the shell model proposed by Mayer and Jensen [7] to modern microscopic approaches, have sought to predict these configurations, particularly the magic numbers.

A key element in the study of nuclear structures is the concept of "magic numbers". Magic numbers are specific numbers of nucleons (protons or neutrons) that result in highly stable atomic nuclei due to the closed shells in the nuclear structure, analogous to the electron shells in atoms. Historically, the classic magic numbers have been identified as 2, 8, 20, 28, 50, 82, and 126. However, recent theoretical advances and experimental observations have revealed the existence of new magic numbers, particularly in superheavy regions and exotic nuclei. For example, various nuclear models, such as the Skyrme–Hartree–Fock and relativistic continuum Hartree–Bogoliubov models [8], predict different sets of magic numbers beyond traditional ones. These include proton numbers Z = 114, 120, and 126 and neutron numbers N = 172, 184, and 198 [9, 10], which are expected to enhance the stability of superheavy nuclei. Moreover, recent research by Rydin [11] suggested additional magic numbers based on a geometrical packing approach, which implies new magic numbers such as Z = 90, 100, and 118, as well as neutron numbers such as N = 58, 68, and 76. These findings indicate that the landscape of magic numbers is far more nuanced than previously thought and that the concept of magicity continues to evolve as new experimental data become available.

Recently, the study of uranium isotopes has played an essential role in both theoretical and applied nuclear physics. Uranium is pivotal for nuclear energy and weapons applications and serves as a potential starting point for synthesizing superheavy nuclei [12] through nuclear decay pathways. Understanding the uranium isotope chain, particularly in terms of ground-state properties such as binding energy, deformation, and density distributions, provides insights into the broader aspects of nuclear stability and shell structure.

Recent experimental advancements have significantly contributed to the study of uranium isotopes, particularly the synthesis and characterization of new neutron-deficient isotopes such as 215U. In 2015, a new isotope, 215U, was produced using a complete fusion reaction involving 180W and 40Ar, followed by the separation of the evaporation residues using the gas-filled recoil separator SHANS. The identification of 215U was based on energy-position-time correlations, with an observed alpha-particle energy of 8.428 MeV and a half-life of approximately 0.73 ms [13]. Similarly, experiments have determined the properties of uranium, showing a consistent trend in the α-decay behavior of neutron-deficient uranium isotopes [14]. These experimental efforts, aided by facilities such as the Heavy Ion Research Facility in Lanzhou (HIRFL), provide essential data that validate theoretical predictions and extend our knowledge of the stability and decay characteristics of heavy nuclei [15].

Theoretical advancements in nuclear physics have led to the development of several models to describe atomic nuclei, including first-principle methods [16-18], the shell model [19-22], and density functional theory (DFT) [23, 24]. Among these, relativistic mean field (RMF) theory, a variant of DFT, has proven to be a powerful tool for describing nuclear structures. The RMF theory incorporates relativistic effects, providing a more comprehensive description of nucleon interactions and allowing for the prediction of ground-state properties and magic numbers with notable accuracy. Previous studies have shown that the RMF theory, combined with the Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer (BCS) approach to treat pairing correlations [25, 26], is effective for describing the ground-state properties of isotopes near the proton drip line.

Despite these advances, several challenges remain in understanding the complete behavior of uranium isotopes, particularly those near the proton drip line, where conventional models face difficulties owing to the intricate interplay between pairing forces and continuum effects. In this study, we employed the RMF theory framework utilizing the TM1 parameter set to systematically investigate the ground-state properties of uranium isotopes ranging from A = 204 to A = 305. Our work aims to provide new insights into the binding energies, deformation characteristics, and proton drip line behavior by comparing the RMF results with the finite-range droplet model (FRDM) [27, 28] predictions.

This paper is organized as follows: In Sect. 2, we provide a brief overview of RMF theory and its application in our study. Section 3 presents our analysis of the ground-state properties of the uranium isotopes. Section 4 discusses the identification of proton drip line nuclei within the uranium chain. Finally, in Sect. 5, we summarize the results and their implications for future experimental and theoretical studies in this field.

Methodology and Theoretical Framework

Relativistic Mean Fields

We used the Lagrangian density

| Parameter | TM1 | NL1 | NLSH |

|---|---|---|---|

| 511.198 | 492.25 | 526.059 | |

| 783.0 | 795.36 | 783.0 | |

| 770.0 | 763.0 | 763.0 | |

| 10.0289 | 10.138 | 10.4434 | |

| 12.6139 | 13.285 | 12.945 | |

| 4.6322 | 4.975 | 4.382 | |

| b | -7.2325 × 10-4 | -6.9099 × 10-4 | -6.9099 × 10-4 |

| c | 0.6183 | -5.4965 × 10-5 | 0.615 |

To further enhance the analysis, three parameter sets—NL1, TM1, and NLSH—were utilized in this study. Each set provides different values for the coupling constants and meson masses, affecting the representation of nuclear interactions and, consequently, nuclear structure predictions. Specifically, the TM1 parameter set, widely acknowledged for its effectiveness in ground-state property calculations, was chosen as the primary model for most calculations presented in this work. For investigations near the proton drip line, comparisons were made among the NL1, TM1, and NLSH sets to assess their respective accuracy and consistency in predicting the properties of exotic nuclei. The parameters for each set are as follows [29-31]:

Ground-state Properties

In the following, we outline the methods used to calculate several important nuclear properties, including binding energy, quadrupole deformation, continuum occupation numbers (or single-particle energy levels), and nucleon density distributions. The relationships and formulas used were derived from a study by Gambhir et al. (1990) [32]. These calculations provide comprehensive insight into the ground-state characteristics of uranium isotopes.

The average binding energy, an essential quantity for determining nuclear stability, was obtained by integrating the energy densities of the nucleons and meson fields. The total binding energy was expressed as follows:

The quadrupole deformation parameter was used to quantify the shape of the nuclei. Deformation parameters were calculated based on the quadrupole moment of the nucleus.

RMF theory is an effective framework for describing nuclear structures by considering the interactions between nucleons mediated by various mesons. However, this alone does not fully account for the pairing interactions between nucleons, which play a significant role in determining the stability and deformation properties of nuclei, particularly in open-shell configurations. To address this, the BCS theory [32, 33] was employed, as it allows for the effective treatment of these pairing correlations and provides a more complete and accurate depiction of the nuclear ground-state properties. This is especially important for heavy elements, such as uranium, where pairing interactions influence many key properties, including binding energy and deformation.

Many properties of the nucleus exhibit a parity dependence, leading to distinct pair correlations between protons and neutrons. The RMF approach used here incorporates these pair interactions by employing the BCS theory as a perturbative correction, specifically incorporating the effective pair force constants for protons and neutrons, given by

Thus, the integration of BCS theory, blocking method, and RMF theory forms a comprehensive framework for studying uranium isotopes. These methods allow for accurate calculation of pairing interactions, single-particle energies, and deformation parameters, which are essential for understanding both the stability and structural nuances of heavy nuclei, including those near the proton drip line.

Determination Of Drip Line Nucleus in U Isotope Chain

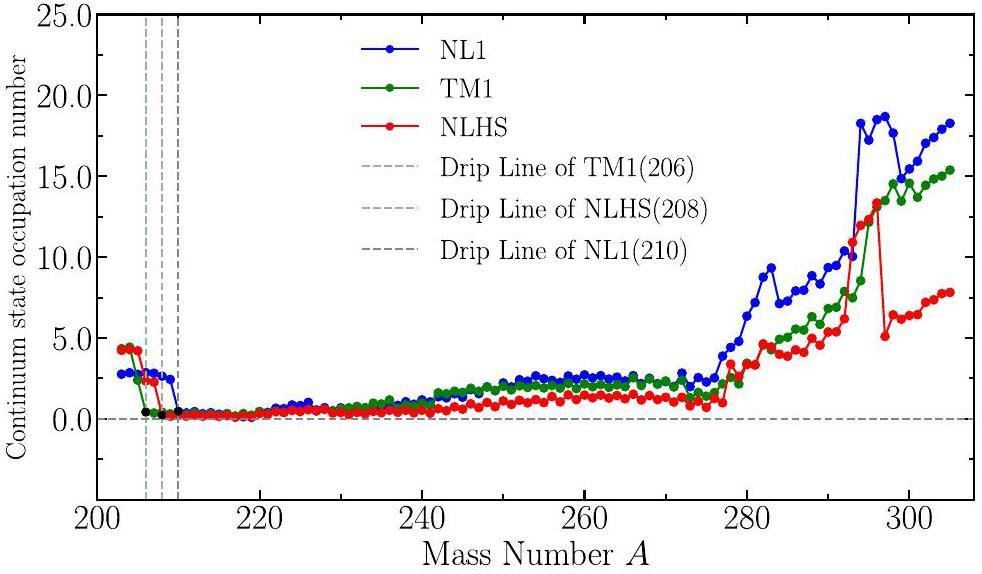

To determine the proton drip line [35-37], we analyzed the continuum-state occupation number of uranium isotopes calculated with different relativistic mean field parameters: NL1, TM1, and NLSH. As depicted in Fig. 1, the continuum-state occupation number shows distinct behavior for the different parameter sets. For isotopes with mass numbers ranging from A=203 to A=305, the occupation number generally remains low for mid-range isotopes, indicating bound systems. However, as shown in the figure, each parameter set predicts a different mass number for the proton drip line nucleus. Specifically, the NL1 parameter set identifies A=210 as the proton drip line nucleus, whereas the TM1 and NLSH parameter sets predict proton drip lines at A=206 and A=208, respectively. These differences highlight the sensitivity of drip line predictions to the choice of interaction parameters.

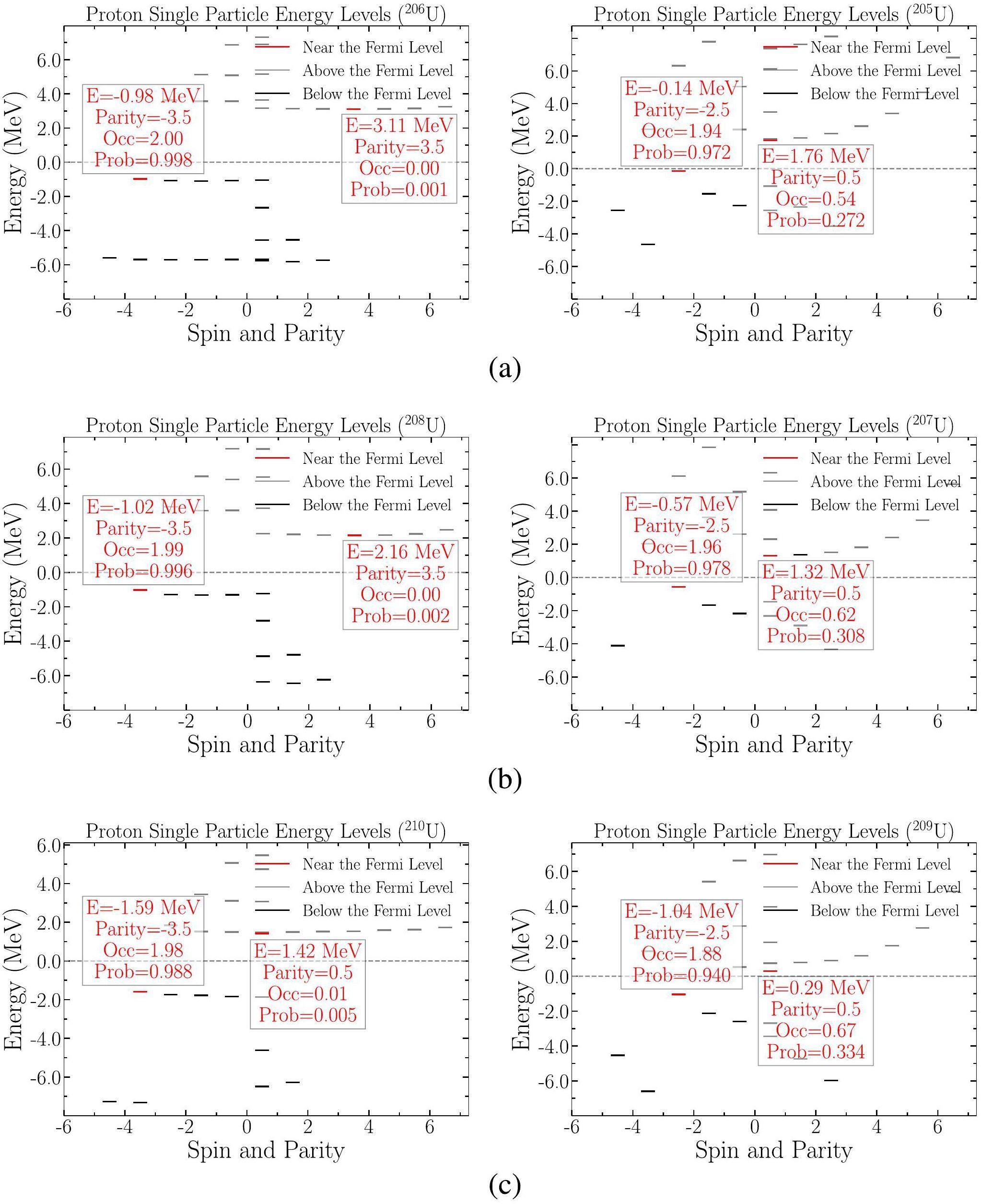

In Fig. 2, the single-particle energy levels near the Fermi surface of the drip line nuclei and their neighboring isotopes are displayed for NL1, TM1, and NLSH parameters. These energy level distributions illustrate that for nuclei at the proton drip line, the occupation of continuum states becomes prominent, signifying their unbound nature. Thus, the proton drip line kernels for the three parameter sets are 209U(NL1), 205U(TM1), 207U(NLSH). Importantly, the different results for the three parameter sets reflect the sensitivity of the RMF model to the choice of parameters. In the absence of definitive experimental data, it is advisable to consider the results from multiple parameter sets to form a more representative prediction and acknowledge this uncertainty in the analysis.

To describe the region of nuclei with relatively more protons along the isotopic chain by applying the better parameter set NLSH, we consider the proton drip line nuclei as a result of the calculation of the NLSH parameter set 207U. For the NLSH parameter set, the analysis of 207U and 208U reveals significant details regarding the occupation of energy states near the Fermi surface. In 207U, the first positive-energy state above the Fermi surface, identified as

As the occupation number of the continuum state fluctuated significantly on the neutron-rich side of the uranium isotopic chain, a distinct anomaly was observed compared with the proton side. This anomaly is particularly evident at mass numbers A=277 and A=278, where the continuum occupation number exhibits an abrupt change from 0.99 to 3.38. This step-like transition suggests that the mean field strength and pairing correlation strength are comparable in magnitude for these nuclei. In such cases, treating pairing correlations merely as perturbations is no longer valid because their contribution is significant enough to substantially influence nucleon dynamics. Consequently, pairing correlations must be rigorously included in self-consistent equations of motion rather than as a small correction.

The improper perturbative treatment of these pairing effects leaves some neutron-rich nuclei in a state where the last neutrons occupy continuum levels, which is unphysical under these conditions and results in an incorrect representation of the binding properties of the nucleus occupying continuum states. This implies that the pairing correlations should be inherently included in the mean field framework, as these correlations are essential for stabilizing the nuclear system and determining the drip line. Therefore, the sharp increase in the continuum occupation number at A=277 and A=278 cannot be interpreted accurately without consistently incorporating these pairing correlations.

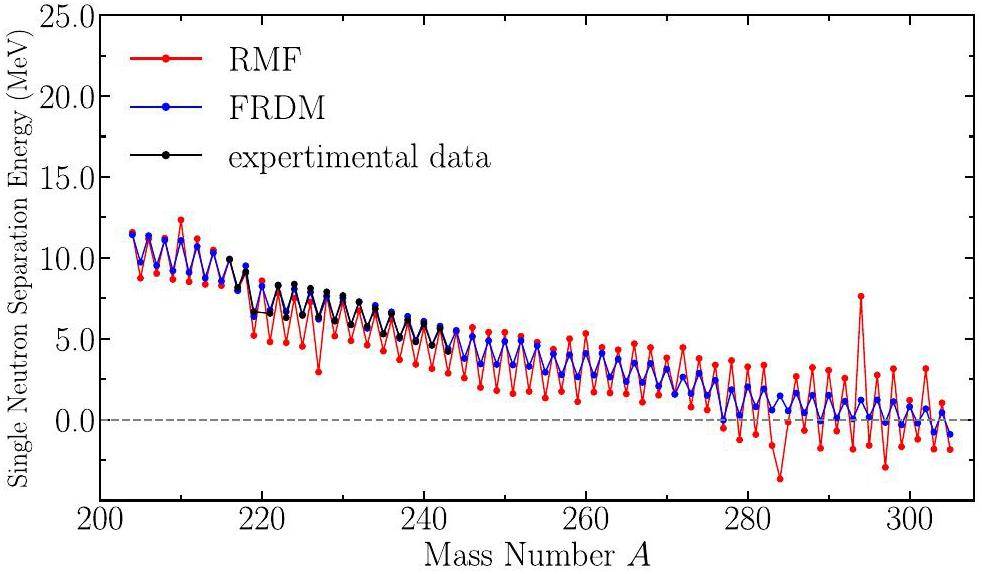

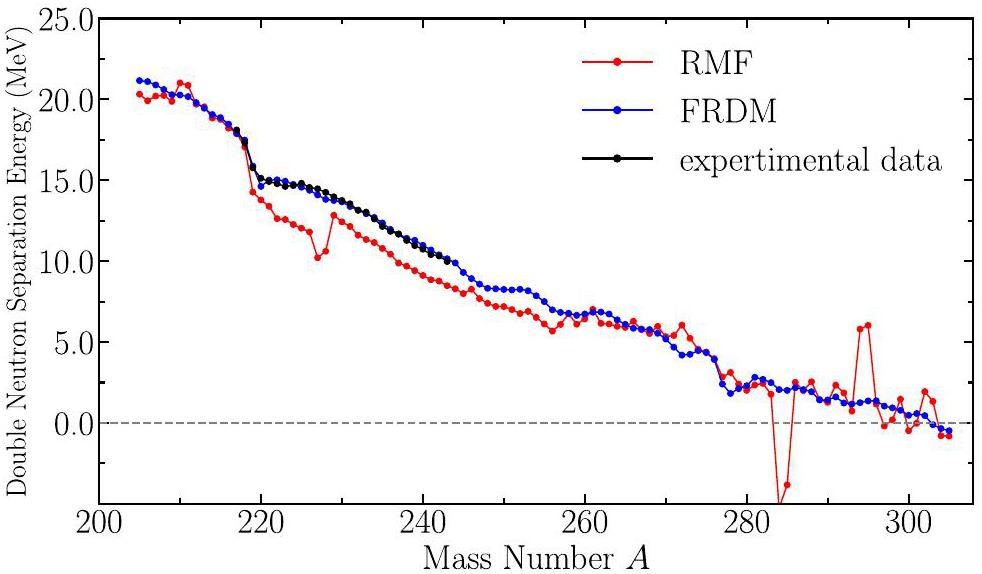

To further clarify the determination of the neutron drip line, we analyzed the one-neutron separation energy Sn and the two-neutron separation energy S2n, as shown in Figs. 3 and 4. The experimental data were obtained from [38]. The results indicate that for the last nuclei in the uranium chain, neither the one-neutron nor the two-neutron separation energies exhibit a clear trend toward zero, which signifies a drip line. Instead, the separation energies decreased gradually without reaching a definitive cut-off, implying that these nuclei were still marginally bound. This lack of a clear zero crossing in the separation energies suggests that using only the Sn and S2n values is insufficient for precisely identifying the neutron drip line.

Properties of Ground State of Nuclei in U Isotope Chain

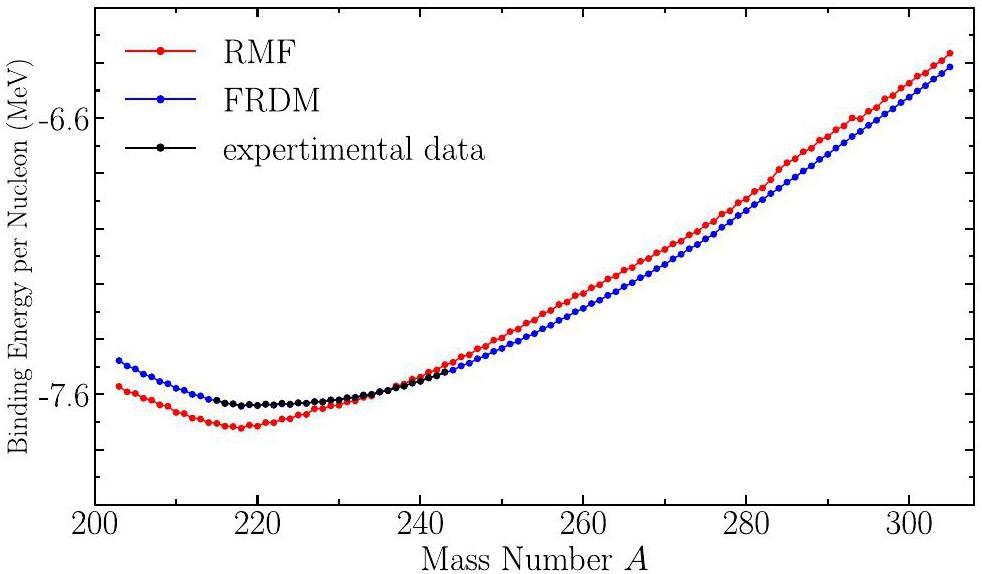

The average binding energies are presented in Fig. 5. It is evident that our calculations are in good agreement with the finite-range droplet model (FRDM) data, with the lowest binding energy observed at the neutron magic number N=126. This agreement indicates that our chosen force constants, treatment of pairing correlations, and implementation of the blocking method for odd-A nuclei provide a reliable theoretical framework. Furthermore, our results show that at N=126 (corresponding to 218U) [39], the average binding energy reaches its maximum value. The binding energy of 218U calculated with our approach is notably higher than that predicted by the FRDM, suggesting the enhanced representativeness of our model.

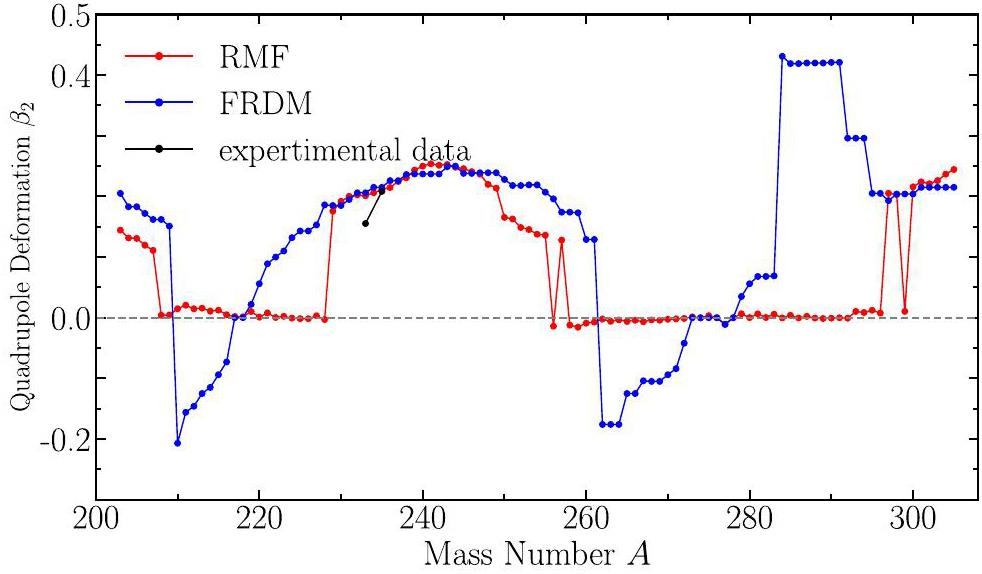

The deformation of the uranium isotope chains is shown in Fig. 6. The red line represents the finite-range droplet model (FRDM) predictions, whereas the black line corresponds to the relativistic mean field (RMF) calculations. A comparison reveals that, unlike the FRDM results, the RMF model shows a smoother deformation [40] trend without the abrupt changes observed at mass numbers A=284-296 This smoother trend suggests that the RMF approach provides a more consistent representation of the quadrupole deformation, particularly in regions where spherical symmetry is expected. Additionally, the deformation pattern indicates that nuclei with mass numbers less than A=208 exhibit a prolate, elongated ellipsoidal shape, whereas those between A=208-228 are almost spherical and exhibit very small deformations. Beyond A=228, the deformation alternates between prolate and spherical, except at A=256, where the deformation suddenly decreases to a spherical shape. Throughout the isotopic chain, there are no pronounced oblate or flat ellipsoidal shapes, and the few negative deformation values can be interpreted as spheroidal rather than strongly oblate shapes.

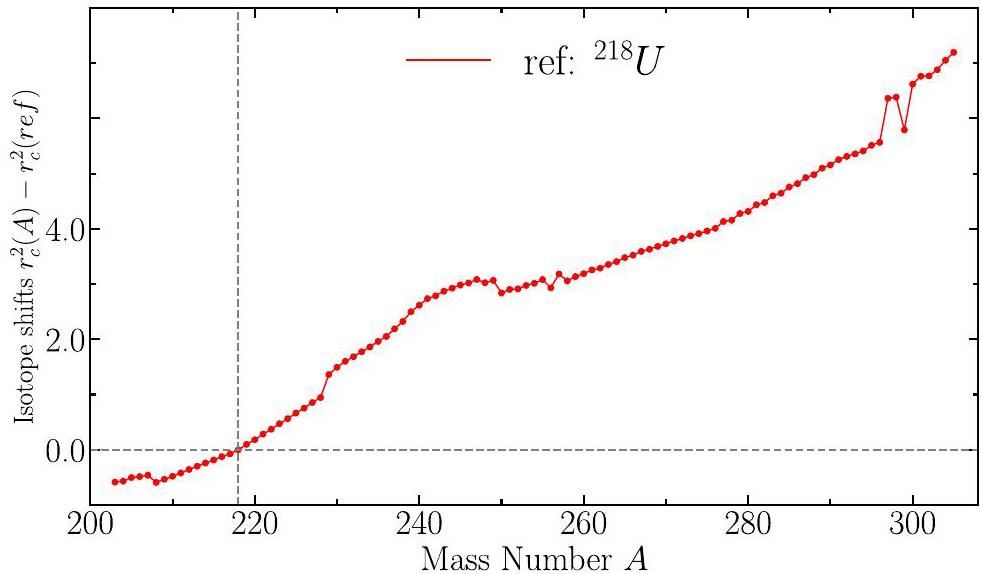

Using 218U, a semi-magic nucleus, as a reference, we analyzed the isotope shifts presented in Fig. 7. The data exhibited a generally smooth increase, with noticeable flattening for nuclei with mass numbers A=247 to A=256. In nuclear physics, a "kink" in isotope shift data refers to an abrupt change in the trend of nuclear charge radii as a function of neutron number, typically occurring at neutron magic numbers. This phenomenon has been observed in rare-earth elements, where such kinks appear near neutron magic numbers, indicating changes in nuclear structure and stability [39, 41-46]

However, in our study of uranium isotopes, no evident kink was observed at A=218, which corresponds to the neutron magic number N=126. This absence suggests that the expected shell-closure effect at N=126 does not manifest prominently in the U isotope shift data. Consequently, based on the isotope shift analysis alone, we cannot confirm that A=218 is a magic number nucleus. This finding is consistent with those of similar studies [47, 48], indicating that the manifestation of magic numbers can vary across different elements and isotopic chains (Fig. 8).

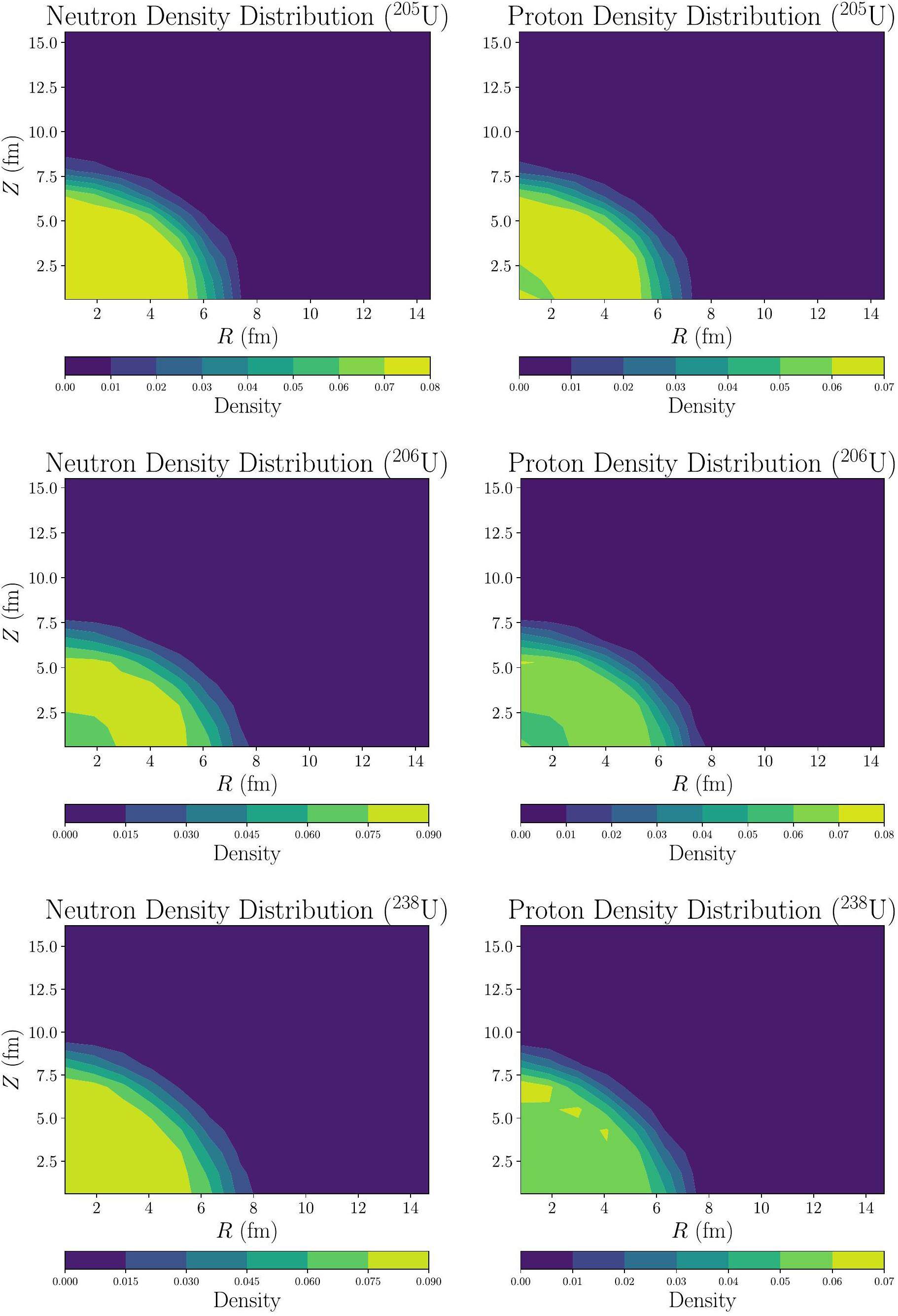

The analysis of the neutron and proton density distributions along the major axes of uranium isotopes, including 205U, 206U, and 238U, provides important insights into their structural characteristics and deformation properties.

First, the density distributions of protons and neutrons are generally centered around the nucleus, with a distinct peak near the core. In all isotopes analyzed, the neutron density extends further than the proton density, indicating the presence of a "neutron skin." The neutron skin, where neutrons dominate the outer regions of the nucleus, is a common feature of neutron-rich heavy nuclei and contributes to the enhanced stability of these uranium isotopes. However, the proton density is more concentrated toward the center, which reflects the influence of Coulomb repulsion, pushing protons inward to counterbalance their mutual repulsive forces.

Among the isotopes, 205U displayed the smallest deformation, suggesting a nearly spherical shape, whereas 238U exhibited the largest deformation, characterized by significant elongation along the major axis. 238U shows intermediate deformations that can be described as prolate and resembling elongated ellipsoids. The neutron skins in these nuclei become more pronounced as the mass number increases, which agrees with the increasing neutron-to-proton ratio [49].

These findings collectively emphasize the significance of neutron excess and nuclear deformation in determining the density profiles of uranium isotopes. The presence of neutron skins in all the analyzed isotopes indicates that neutrons dominate the periphery of these nuclei, which has important implications for understanding nuclear stability, interaction cross-sections, and the behavior of these nuclei near the dripline. RMF theory effectively captures these differences in density distributions and provides a comprehensive picture of the underlying nuclear structure of heavy isotopes, contributing to a better understanding of their stability and deformation characteristics.

Summary

We calculated the ground-state properties of nuclei in the uranium isotope chain using the relativistic mean field (RMF) theory, incorporating pairing correlations through the Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer (BCS) approach. Our results, which show good agreement with the finite-range droplet model (FRDM) data, particularly at the neutron magic number N=126 validate the robustness of our approach in modeling the binding energies and deformation properties of uranium isotopes. By analyzing the Fermi surface and single-particle energy levels, we confirmed that 207U is a proton dripline nucleus due to its continuum-state proton occupancy, whereas 208U remains bound, highlighting the precise identification of the dripline.

In the future, the continued development of RMF theory, incorporating more advanced treatments of pairing and beyond-mean-field effects, holds great promise for understanding the properties of nuclei near the dripline, particularly for superheavy elements, which are crucial for practical applications, especially in nuclear fission processes relevant to energy production and reactor safety. Additionally, advancements in experimental facilities will be key to validating theoretical predictions and exploring new regions of the nuclear chart. The synergy between theoretical advancements and experimental verification will deepen our understanding of nuclear structure, stability, and broader implications for nuclear technology.

Synthesis of the isotopes of elements 118 and 116 in the 249Cf and 245Cm+48Ca fusion reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 74,Quasi-fission dynamics in nearly symmetric reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 89,Production mechanism of superheavy nuclei in 48Ca-induced reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Theoretical study of production cross sections of superheavy nuclei in cold fusion reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 98,Role of nuclear shell structure in synthesis of superheavy elements in 50Ti-induced fusion reactions

. Phys. Rev. C 105,Random forest-based prediction of evaporation residue cross sections in cold fusion reactions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 34, 204 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-023-01354-5On closed shells in nuclei. II

. Phys. Rev. 75, 1969-1970 (1949). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.75.1969Clustering in nuclei: Progress and perspectives

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35(12), 216 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01588-xSuperheavy nuclei in self-consistent nuclear calculations

. Phys. Rev. C 56, 238-243 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.56.238Equation of state of dense matter and neutron star structure with scalar-vector interaction in the relativistic Hartree-Fock theory

. Phys. Lett. B 753, 97-102 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physletb.2015.12.004New magic numbers and mass models

. Ann. Nucl. Energy 38(11), 2356-2358 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anucene.2011.06.026Application of deep learning in nuclear reaction cross section prediction

. J. Beijing Normal Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 58(3), 392-399 (2022). https://doi.org/10.12202/j.0476-0301.2022082Alpha decay of new isotope 216U and systematic study of alpha decay in heavy nuclei

. Eur. Phys. J. A 51(7), 88 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1140/epja/i2015-15088-9Systematic study of α decay in heavy and superheavy nuclei using a two-potential approach

. Chin. Phys. C 46(11),Vr-defined isochronous mass spectrometry with magnetic rigidities around the transition point

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35(12), 213 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01587-yAb initio predictions for nucleon scattering on doubly magic nuclei

. EPJ Web Conf. 146, 12022 (2017). ND 2016: International Conference on Nuclear Data for Science and Technology. https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/201714612022High-performance computing for ab initio nuclear theory: Matrix elements and many-body methods

. Phys. Rev. C 99(5),Large-basis ab initio no-core shell model and its application to 12C

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84(25), 5728-5731 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.5728The shell model as a unified view of nuclear structure

. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77(2), 427-488 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.77.427Gamow shell model description of neutron-rich nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 70(6),New “USD” Hamiltonians for the sd shell

. Phys. Rev. C 58(4), 2099-2107 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.58.2099Status of the nuclear shell model

. Annu. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 38, 29-66 (1988). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ns.38.120188.000333Relativistic continuum Hartree-Bogoliubov theory: Recent applications

. Rom. J. Phys. 58, 1038-1047 (2013).Neutron radii in mean-field models

. J. Phys. G Nucl. Part. Phys. 31(8), S1357-S1366 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1088/0954-3899/31/8/014Nuclear ground-state properties with a new relativistic mean-field interaction

. Phys. Rev. C 58(3), 1467-1472 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.58.1467Shape evolution and shape coexistence in neutron-rich nuclei around N=60

. Phys. Rev. C 88(5),New finite-range droplet mass model and equation-of-state parameters

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108(5),Nuclear ground-state masses and deformations: FRDM(2012)

. At. Data Nucl. Data Tables 109–110, 1-204 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adt.2015.10.002Relativistic mean-field theory for unstable nuclei with non-linear σ and ω terms

. Nucl. Phys. A 579(3), 557-572 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(94)90923-7Rho meson coupling and the ground state properties of neutron-rich nuclei

. Phys. Lett. B 312(4), 377-381 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1016/0370-2693(93)90970-SRelativistic calculation of nuclear matter and the nuclear surface

. Nucl. Phys. A 292(3), 413-428 (1977). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(77)90626-1Relativistic mean-field theory for finite nuclei

. Ann. Phys. 198(1), 132-179 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-4916(90)90330-QRelativistic mean field theory with density-dependent meson-nucleon couplings

. Prog. Theor. Phys. 110(5), 921-936 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1143/PTP.110.921Nuclear ground-state properties with a new relativistic mean-field interaction

. Phys. Rev. C 58(3), 1467-1472 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.58.1467Relativistic mean-field description of deformed light nuclei

. Phys. Rev. C 57(6), 3071-3078 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevC.57.3071Deformed odd-A nuclei near the neutron drip line

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 72(7), 981-984 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.72.981VChartHTML: Interactive Chart of Nuclides

. Available at: https://www-nds.iaea.org/relnsd/vcharthtml/VChartHTML.html [AccessedNuclear structure of neutron-rich Rb isotopes studied by laser spectroscopy

. Phys. Rev. C 97(1),Collective properties of spherical and deformed nuclei in the rare-earth region

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 27(25), 1741-1744 (1971). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.27.1741A new parameterization for the Lagrangian density of relativistic mean field theory

. Nucl. Phys. A 597(1), 35-65 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9474(95)00436-XPairing anti-halo effect on the neutron skin thickness and radii of neutron-rich Ca isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 107(5),Fission dynamics within time-dependent Hartree-Fock: Deformation-induced fission

. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110(3),Shape transitions in neutron-rich Cr, Fe, and Ni isotopes in a self-consistent mean-field calculation

. Phys. Rev. C 91(2),Deformation and shape coexistence in neutron-rich nuclei in the Skyrme-Hartree-Fock approach

. Phys. Rev. C 92(4),Comparative study of charge radii and neutron skin thickness in Ca isotopes

. Phys. Rev. C 107(5),Observation of neutron-deficient isotopes near the proton drip line

. Z. Phys. A 342(1), 123-124 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01294498Kinks in the charge radii and shell structure of Pb isotopes

. J. Phys. G Nucl. Part. Phys. 48(7),Neutron skin and its correlation with the symmetry energy in nuclear reactions

. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 35(12), 211 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41365-024-01584-1The authors declare that they have no competing interests.